Abstract

Heterogeneous distribution of components in the biological membrane is critical in the process of cell polarization. However, little is known about the mechanisms that can generate and maintain the heterogeneous distribution of the membrane components. Here, we report that the propagating wave patterns of the bacterial Min proteins can impose steric pressure on the membrane, resulting in transport and directional accumulation of the component in the membrane. Therefore, the membrane component waves represent transport of the component in the membrane that is caused by the steric pressure gradient induced by the differential levels of binding and dissociation of the Min proteins in the propagating waves on the membrane surface. The diffusivity, majorly influenced by the membrane anchor of the component, and the repulsed ability, majorly influenced by the steric property of the membrane component, determine the differential spatial distribution of the membrane component. Thus, transportation of the membrane component by the Min proteins follows a simple physical principle, which resembles a linear peristaltic pumping process, to selectively segregate and maintain heterogeneous distribution of materials in the membrane.

Video Abstract

Introduction

Self-organization of biological molecules underlies the fundamental cellular processes of all live forms. The Min system of Escherichia coli is a model system for studying protein self-organization that forms dynamic wave patterns on the membrane surface both in vivo and in vitro. The Min system, which consists of the three proteins MinC, MinD, and MinE, mediates the cell division site placement (1). The ATP-dependent interactions between MinD and MinE on the cytoplasmic membrane lead to cycles of pole-to-pole oscillation in vivo, thereby generating a concentration gradient of MinD that is high at both poles. Because the cell division inhibitor MinC interacts and oscillates along with MinD, the oscillation cycle facilitates division inhibition at the poles to prevent aberrant division (2, 3, 4). Using the in vitro reconstitution approach, purified MinD and MinE in the presence of ATP can form propagating or standing waves on the supported lipid bilayers (SLBs) (5, 6, 7). The formation of the MinDE wave patterns depends on the protein concentration, the molar ratio between MinD and MinE, and the geometrical confinement in which the wave patterns are reconstituted (7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12). Along with the experimental works, a series of numerical models have been reported to simulate the formation of the Min protein waves based on the reaction-diffusion theory (5, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17, 18, 19, 20).

Although the Min system has been well characterized and the protein-membrane interactions underlying the system is appreciated, the division inhibitor MinC has been the only known transport cargo of the Min system until now. Whether the membrane-associating oscillation of the Min system can affect other biological functions through influencing the membrane processes is not known. To uncover unanticipated functions of the Min system, a recent work reported that the Min oscillation cycle affected protein association with the inner membrane that resulted in modulating the cellular metabolism (21). Under the same theme, we asked whether the Min system can act as a molecular machinery to spatially segregate membrane components in the membrane. Herein, we combined the experimental and theoretical methods to demonstrate that the propagating Min protein waves on SLBs can drive corresponding wave formation of the membrane components, leading to spatial segregation of the components. We conclude that the spatial distribution of the membrane component is determined by a balance between the steric pressure emerging between the Min proteins and the membrane component and the diffusivity of the component in the membrane. Both the soluble region of the component above the membrane and the membrane anchor of the component in the membrane contribute to the emergence of the steric pressure. The conclusions of this study may imply that pole-to-pole oscillation of the Min proteins inside a bacterial cell could selectively segregate the membrane component to the designated membrane locations where the function of the component is required.

Materials and Methods

Overexpression and purification of MinD

The His6-MinD fusion protein was expressed from BL21(DE3)/pLysS/pSOT4 [PT7::his6-minD]. A 24 mL overnight culture was used to inoculate 2.4 L fresh lysogeny broth medium supplemented with 0.4% glucose, 34 μg/mL chloramphenicol, and 30 μg/mL kanamycin. The culture was grown in a 37°C shaker incubator until OD600 nm reached 0.4–0.6. The culture was cooled down to 16°C, followed by addition of 0.7 mM isopropyl β-D-1-thiogalactopyranoside, and cultured at the same temperature for an additional 16 h. Cells were harvested and resuspended in 90 mL prechilled buffer A (50 mM potassium phosphate buffer (pH 7.4), 500 mM NaCl, 10% (v/v) glycerol, 5 mM β-mercaptoethanol, 2% (v/v) Triton X-100, three tablets of cOmplete, ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (EDTA)-free Protease Inhibitor Cocktail (Roche, Basel, Switzerland)) containing 10 mM imidazole, followed by sonication on ice using a 1/2-inch (13 mm) probe controlled by the Ultrasonic Processor VC750 (Sonics & Materials, Newton, CT). The cell lysate was centrifuged at 50,000 × g for 70 min at 4°C. The supernatant was filtered through a 0.22 μm syringe filter (Millex-GP, 33 mm, PES; MilliporeSigma, Burlington, MA) before being applied to a C10/10 column (GE Healthcare Life Sciences, Marlborough, MA) packed with 5 mL His60 Ni Superflow resin (Clontech Laboratories, Takara Bio USA, Mountain View, CA) at 4°C. After automated Superloop sample application, the column was washed with 100 mL buffer A containing 10 mM imidazole, followed by a step gradient of imidazole from 10 to 90 mM in a total volume of 150 mL. The protein was then eluted with 30 mL 400 mM imidazole and concentrated to 3 mL for gel filtration using a HiLoad 16/600 Superdex 200 pg column (GE Healthcare Life Sciences) with the buffer containing 20 mM HEPES (pH 7.5), 450 mM KCl, 10% (v/v) glycerol, 0.1 mM EDTA, and 2 mM dithiotheritol. Fractions collected after gel filtration were examined using 12% sodium dodecyl sulfate polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (22). The protein concentration was determined using the Bradford Protein Assay kit (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, CA). The protein sample was concentrated using 10 KDa molecular weight cut off (MWCO) Amicon Ultra Filters (MilliporeSigma) before storing at −80°C.

Overexpression and purification of MinE

An overnight culture of BL21(DE3)/pLysS/pSOT13 [PT7::minE-his6] (23) was diluted 40-fold into 1 L fresh lysogeny broth medium supplemented with 0.4% glucose, 34 μg/mL chloramphenicol, and 30 μg/mL kanamycin. The culture was grown in a 37°C shaker incubator until OD600 nm reached 0.4–0.6. The culture was cooled down to 16°C, followed by addition of 0.5 mM isopropyl β-D-1-thiogalactopyranoside, and cultured at the same temperature overnight. Cells were harvested and resuspended in 25 mL prechilled buffer B (50 mM Tris-Cl (pH 7.4), 300 mM NaCl, 10% (v/v) glycerol) containing 5 mM imidazole, followed by three passages through the high-pressure cell disruption system at 30,000 psi to break cells. The cell lysate was centrifuged at 90,000 × g for 1 h at 4°C. The supernatant was filtered through a 0.22 μm filter cup before applying it to a 1 mL His-Trap HP Column (GE Healthcare Life Sciences) at 4°C. The column was washed with 50 mL buffer B containing 40 mM imidazole. Protein was eluted with a linear gradient of imidazole from 40 to 300 mM in a volume of 30–50 mL. The peak fractions were pooled together and dialyzed against buffer C (25 mM HEPES (pH 7.6), 300 mM KCl, 10% (v/v) glycerol, 0.1 mM EDTA, 2 mM dithiotheritol), followed by concentration using 3K MWCO Amicon Ultra Filters (MilliporeSigma). The sample was further purified using a Superdex75 column (16/60; GE Healthcare Life Sciences). The protein concentration was determined using the Bradford Protein Assay kit (Bio-Rad Laboratories). The purified protein was examined by separation on 12% NuPAGE Bis-Tris Protein Gels (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA).

Protein labeling

The amine-reactive dye, including the Alexa Fluor 594 N-hydroxysuccinimide Ester and Alexa Fluor 647 N-hydroxysuccinimide Ester (Thermo Fisher Scientific), was dissolved in dimethylsulfoxide to a final concentration of 10 μg/μL. Each 100 μL reaction contained 100 μg protein dissolved in phosphate-buffered saline (pH 7.5), 100 mM sodium bicarbonate (pH 9.0), and 50–100 μg reactive dye. The reaction mixture was incubated with constant mixing in the dark at room temperature for 1 h. The labeling reaction of MinE was passed through a Zeba spin desalting column (7K MWCO; Thermo Fisher Scientific) to remove excess dye, followed by exchange into the reaction buffer (25 mM Tris-Cl (pH 7.5), 5 mM MgCl2, 150 mM KCl) containing 10% (v/v) glycerol, aliquoted, and stored at −80°C. The labeling reaction of MinD was subjected to Sephadex G-25 fine buffer exchange before further purification by separation on a Superdex 200 Increase 10/300 GL column (GE Healthcare Life Sciences) in the MinD gel-filtration buffer containing 10% (v/v) glycerol. The degree of labeling was determined according to the manufacturer’s instruction: Alexa Fluor 594-MinD, 0.5; Alexa Fluor 647-MinE, 1.37.

Preparation of unilamellar vesicles for the formation of SLBs

Phospholipids 1,2-dioleoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine (18:1 (Δ9-Cis) PC; DOPC) and 1,2-dioleoyl-sn-glycero-3-phospho-(1′-rac-glycerol) (18:1 (Δ9-Cis) PG; DOPG) were purchased from Avanti Polar Lipids (Alabaster, AL). N-((6-(biotinoyl)amino)hexanoyl)-1,2-dihexadecanoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphoethanolamine (biotin-X DHPE), streptavidin Alexa Fluor 488 conjugate (Alexa Fluor 488 streptavidin), lissamine rhodamine B 1,2-dihexadecanoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphoethanolamine (rhodamine DHPE), and 2-(4,4-difluoro-5,7-dimethyl-4-bora-3a,4a-diaza-s-indacene-3-dodecanoyl)-1-hexadecanoyl-sn-glycero-3-PC (β-BODIPY FL C12-HPC) were purchased from Thermo Fisher Scientific. The lipid mixture was prepared with different composition, resulting in 67/33/0.5 mol% of DOPC/DOPG/biotin-X DHPE, 67/33/0.25 mol% of DOPC/DOPG/rhodamine DHPE, or 67/33/1 mol% of DOPC/DOPG/BODIPY FL C12-HPC. The mixture in chloroform was dried under nitrogen stream to leave a thin layer of the lipid cakes at the bottom of the container. The container was placed under vacuum to completely remove the solvent. The dried lipid cakes were rehydrated in the reaction buffer to a final concentration of 1 mg/mL. The rehydrated liposome solution was extruded sequentially through 400, 100, and 50 nm polycarbonate filters using a miniextruder (Avanti Polar Lipids) to prepare unilamellar vesicles. The extrusion was performed 19 times for each filter pore size. The vesicle suspension was stored at 4°C for up to 2 days.

Preparation of microchannels

The Sylgard 184 silicone elastomer kit (Dow Corning, Midland, MI) was used to prepare the polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS) channels. Briefly, the base (Sylgard 184A) was mixed thoroughly with the catalyst 87-RC (Sylgard 184B) at a 10:1 weight ratio, pulled into a 15 cm plastic petri dish with a wafer of microchannel patterns placed on the bottom, and degassed under vacuum for more than an hour. The elastomer mixture was cured at 70°C for at least 3 h to form a solid slab. The pieces were cut out from the solidified slab according to the microchannel design. The dimension of the microchannel was 1 cm × 1 mm × 16 μm (length × width × height), with circular reservoirs at both ends to accommodate liquid injection and removal during experiments (Fig. S1). Holes were punched using a 14G flat-end needle at the reservoir positions on both ends, followed by cleaning with 95% ethanol and being blow-dried under a nitrogen gas stream. Immediately before assembly of the microchannel device, both the glass coverslip and the PDMS piece were subjected to surface treatment using the Expanded Plasma Cleaner (PDC-001; Harrick Plasma, Ithaca, NY). Briefly, the coverslip was cleaned with argon plasma at 1.5 Torr for 10 min, followed by treating both the coverslip and PDMS piece with oxygen plasma using air at 400 mTorr for 75 s.

50 μL vesicle suspension was flowed into a microchannel for the formation of SLBs. The lipid suspension in the microchannel was incubated at room temperature for an hour. After incubation, the vesicle suspension was drawn out from the reservoir and replaced with 50 μL reaction buffer to wash off excess vesicles. For observation of the DOPC/DOPG/biotin-X DHPE membranes, 5 μM Alexa Fluor 488 streptavidin (Thermo Fisher Scientific) was prepared in the reaction buffer and was filtered through a 0.1 μm centrifugal filter unit (Durapore polyvinylidene difluoride; MilliporeSigma). The concentration was remeasured as 4 μM, and degree of labeling was estimated as 1.26. The streptavidin solution was incubated with the SLB at room temperature for 1 h. The solution was then removed, followed by five washes with the reaction buffer. Before applying the reaction mixture, the microchannel was equilibrated with the reaction buffer containing 5 mM phosphoenolpyruvate, 10 μg/mL pyruvate kinase, and 5 mM ATP for 15 min.

Reaction mixture of protein and membrane waves

The reaction mixture containing His6-MinD and MinE-His6 was prepared in the reaction buffer without ATP, thoroughly mixed, and filtered through a 0.22 μm centrifugal filter unit (Durapore polyvinylidene difluoride; MilliporeSigma). For observing the protein wave, 20 or 50 mol% of Alexa Fluor 594 His6-MinD and/or Alexa Fluor 647 MinE-His6 was included in the reaction mixture. The protein concentration varied slightly between experiments because of mixing in the fluorescently labeled MinD and/or MinE, but the molar ratio of MinD/MinE was close to 10:12 μM. 5 mM ATP was added to the filtered reaction mixture before applied to the SLB-coated microchannel for imaging waves at room temperature.

Fluorescence microscopy

Fluorescence images were acquired on the Olympus FLUOVIEW FV3000RS system (Olympus, Tokyo, Japan) equipped with the objectives UPLSAPO 10×2 (NA 0.4) and UPLSAPO 20× (NA 0.75); lasers of 488 nm (20 mW), 561 nm (20 mW), and 640 nm (40 mW); and the high-sensitivity spectral detector. The spectral range to acquire images were set as 500–550 nm for Alexa Fluor 488, 570–620 (or 630) nm for Alexa Fluor 594 and rhodamine, and 650–750 nm for Alexa Fluor 647. We used the imaging conditions of rhodamine to observe Alexa Fluor 594 to obtain spectral separation with Alexa Fluor 647. The airy disk was set at 1.5, and the confocal aperture was tuned automatically by the instrument. The Olympus FV3/SW software was used for image acquisition. An inverted microscope (Olympus IX81) equipped with objective lenses of the same specification as above, filter sets for imaging Alexa Fluor 488 (49002; Chroma, Bellows Falls, VT), Cy3 (49005; Chroma), and Cy5 (Cy5-4040A; Semrock, Rochester, NY), a CCD camera (ORCA-R2; Hamamatsu, Hamamatsu, Japan), and the Olympus Xcellence Pro software were used. Each microscopy image shown in the study represents a set of repeating experiments (greater than three) using the reaction mixtures prepared independently and applied in different SLB-coated microchannels. Multiple positions were imaged in independent channels.

The acquired images were processed and analyzed using National Institutes of Health ImageJ (National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, Maryland; http://rsb.info.nih.gov/ij/). The intensity profile was plotted using Microsoft Excel and GraphPad Prism (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA). The spatial intensity profiles were smoothed to facilitate visualization. The surface plots were generated using MATLAB R2015a (The Mathworks, Natick, MA).

Fluorescence recovery after photobleaching

The fluorescence recovery after photobleaching (FRAP) experiments were performed on the confocal system with 20× lens to measure diffusion coefficients of the membrane components. On the confocal microscope, regions of interests (ROIs) of 25 μm in diameter or 25 × 25 μm2 square areas were bleached for 31 s continuously with a 488 nm laser with 100% power for Alexa Fluor 488 or with 488 and 594 nm lasers simultaneously with 100% power for 61 s continuously for BODIPY FL and rhodamine, respectively. For the wave experiments, ROIs were bleached with 488 and 640 nm lasers simultaneously with 100% power for 3 s. Five frames were taken before bleaching, and the image acquisition was continued for 10 min with a 6 s interval after bleaching. The images were processed, and the two-dimensional (2-D) diffusion coefficient of a membrane component in the membrane was calculated in MATLAB using an algorithm as previously described (24).

Modeling the MinDE and membrane component waves

A published model by Petrasek (18) was used to describe the Min protein dynamics. This model produced simulated concentration profiles of MinD and MinE that captured two characteristic features in our in vitro experiments, including 1) the profile was asymmetrical, with the concentration maximum leaning toward the trailing edge of the Min wave, and 2) the MinE concentration profile showed a sharp decline at the trailing edge of the waves. The resemblance between our experimental data and the simulated profiles provided a reliable basis to develop a numerical model of the membrane component dynamics.

However, instead of the one-dimensional geometry in the Petrasek model (18), the 2-D geometry of the membrane plane in the Loose model (5) was applied to mimic the experimental conditions (Supporting Materials and Methods; Fig. S2). Therefore, 2-D descriptions were used to reproduce the distribution of membrane-bound proteins. Comparison of geometrical settings in different numerical models describing the Min protein dynamics (5, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17, 18, 19, 20) is provided in the Supporting Materials and Methods. Both protein concentrations CD and CE (see below) were viewed only as the function of x, y, and t (time) dimensions. This assumption is supported by Bonny’s simulation of the concentration profiles along the z dimension (17), in which they reported that the Min proteins were confined in a thin layer of ∼15 μm above the membrane plane. Therefore, the Min system was viewed as a 2-D system on the membrane plane plus an effective solution region in our numerical model.

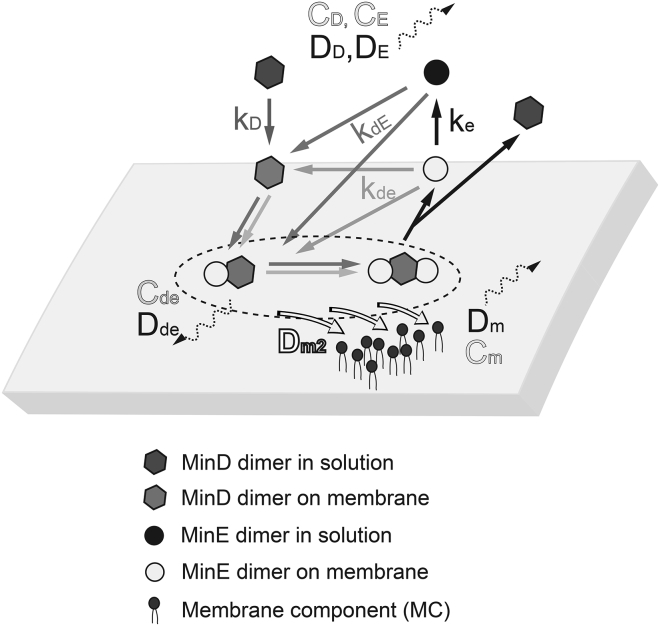

The kinetic steps in the numerical model that describe the Min protein dynamics are illustrated in Fig. 1. The criteria are as follows: 1) ATP is abundant in the system; 2) because both MinD and MinE spontaneously form dimers in solution, the dimerization step is not included, and MinD and MinE in the model refers to their dimeric forms; 3) each MinD carries two MinE-interacting sites; 4) either solution-form or membrane-bound MinE can bind to one of the interacting sites on MinD to form a MinDE complex on the membrane; 5) either solution-form or membrane-bound MinE can bind to the empty interacting site on a MinDE complex, which immediately causes dissociation of the entire complex, with MinD going to the solution and MinE staying on the membrane; 6) MinD binds to the membrane with a rate constant kD; 7) kdE is the rate constant for the solution-form MinE to interact with membrane-bound MinD or MinDE complex; 8) kde is the rate constant for the membrane-bound MinE to interact with the membrane-bound MinD or MinDE complex; and 9) ke is the rate constant to describe dissociation of membrane-bound MinE from the membrane. The concentration, which changes with time in the system, is described as the following: CD (MinD in the solution), CE (MinE in the solution), Cd (MinD on the membrane), Ce (MinE on the membrane), and Cde (MinDE complex on the membrane), respectively. The diffusivity of MinD, MinE, and the membrane component is described as DD (MinD in the solution), DE (MinE in the solution), Dd (MinD on the membrane), De (MinE on the membrane), and Dde (MinDE complex on the membrane), respectively. To describe the membrane component, the concentration, Cm, and the diffusivity, Dm, of the membrane component were introduced. In addition, the constant Dm2 was used to describe the repulsed ability of the membrane component as discussed in Results.

Figure 1.

Illustration of the kinetic steps explaining interactions, rate constants, concentrations, and diffusivity factors used in the numerical model. The rate constants and the corresponding steps are coded in different gray colors.

Based on the aforementioned criteria and rationales, the kinetic model of the Min protein dynamics is shown in Eqs. 1, 2, 3, 4, and 5. Although Eqs. 1 and 2 describe the mass balance of MinD and MinE in the effective solution region, Eqs. 3, 4, and 5 describe the mass balance of MinD, MinE, and MinDE bound on the membrane plane. Equation 6 describes the mass balance of a membrane component in the membrane, i.e., the change of membrane component concentration (Cm) could be attributed by its own diffusion and the steric repulsion caused by MinD and MinDE complexes on the membranes. Cm0 is the averaged concentration or the initial concentration of the membrane component in the membrane. Thus, Cm/Cm0 represents the normalized concentration of the membrane components. Further details are discussed in the Results.

| (1) |

| (2) |

| (3) |

| (4) |

| (5) |

| (6) |

Comsol Multiphysics version 5.3a (Comsol, Burlington, MA) was used to numerically solve the kinetic model on 2-D spatial grids within a 300 × 150 μm region. The backward differentiation formula method, which is a linear multistep method to approximate the solutions of ordinary differentiation equations from the past (backward) computed values, was used to numerically solve the equations. We chose the options of free steps and automatic maximal step constraint determined by the solver. The backward differentiation formula order was set between 5 and 1. The time step is around 0.5 s, and the entire video contains 1000 s. The periodic boundary conditions were used to set the boundaries for all substances, including the Min proteins in solution, the Min proteins attached to the membranes, and the tested membrane components. The experimental concentrations of MinD and MinE were 10 and 11.65 μM, respectively. These volumetric concentrations were converted to effective 2-D surface concentrations using the method of Loose et al. (5), by which the effective 2-D surface concentrations were obtained by correlation with the three-dimensional concentration using the mass balance of MinD and MinE in solution. The diffusion constants of MinD and MinE in the bulk solution and the diffusion constants of the MinD, MinE, and MinDE complex in the membrane are based on the measurements reported previously (5). The rate constants, including kD, kdE, kde, and ke, were derived from the literature (18). The membrane component concentration is calculated based on the molar ratio of the membrane component in SLBs.

Results

Identification of the membrane component waves

To investigate whether the Min protein waves could influence the phospholipid bilayer, we adopted the in vitro reconstitution experiments (5) with emphases on the membrane components. We performed multicolor imaging experiments to obtain direct evidence for the existence of the membrane component waves. While MinD and MinE were conjugated with different fluorophores, the SLBs (DOPC:DOPG = 67:33 mol%) were doped with 0.5 mol% Biotin-X DHPE that allowed subsequent treatment with Alexa Fluor 488 Streptavidin for examination of the membrane component waves. The reaction mixture of MinD, MinE, and ATP was injected into the SLB-coated microchannels for studying the colocalization patterns of MinD, MinE, and the membrane-tethered streptavidin.

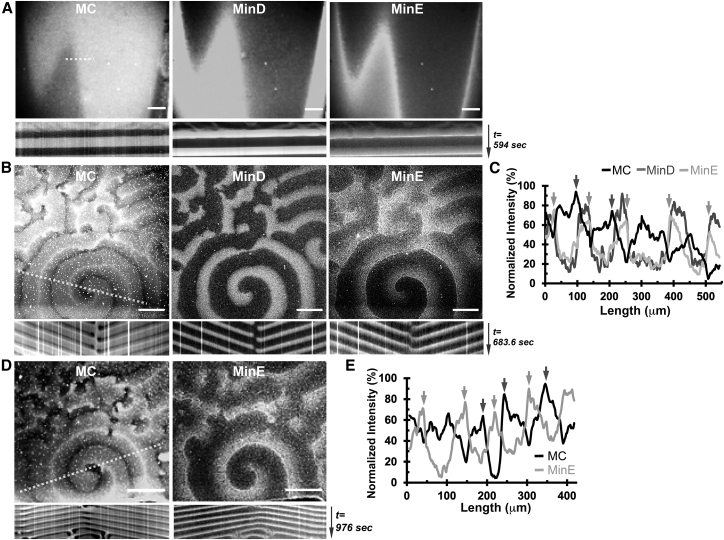

Using this setup, we observed the streptavidin waves in correspondence with the Min protein waves, indicating that the membrane component waves were generated alongside the Min protein waves (Fig. 2; Videos S1, S2, and S3). The protein and membrane component waves were dynamically evolving over time, showing up in different scales and waveforms. We described these initial large-scale waves as the “waterfall” waves because the spatial change of fluorescence with time in all three channels resembled buckets of water pulling down the imaging field (Fig. 2 A; Video S1). The large-scale waves gradually transformed into spiral and traveling waves across the entire channel within 1–2 h. Once the waves were formed, they were stable even after 24 h (Fig. 2, B and D; Videos S2 and S3). The wavelength, periodicity, and velocity of the membrane component waves showed a wide variation, as shown in Table 1, which might be due to the open microchannel system used in this study that had several uncontrolled factors, such as the flow fluency and rate, to alter the self-organization patterns of the Min proteins.

Figure 2.

The corresponding membrane component (MC) waves of streptavidin/biotin-X DHPE formed along with the MinD and MinE protein waves. (A) Large-scale waterfall waves (Video S1) and (B and D) spiral waves (Videos S2 and S3) are shown. Scale bars, 100 μm. The kymographs, obtained from all channels along the dashed lines labeled in (A), (B), and (D), are shown below each micrograph. (C and E) The intensity profiles of the MC, MinD, and MinE waves were obtained along the dashed lines as labeled in (B) and (D), respectively. The dark gray arrows indicate the positions where the peak MC intensity occurred at the relatively low MinE intensity. The light gray arrows indicate the positions where the lowest MC intensity occurred near the peak MinE intensity.

Table 1.

Characteristics of the Membrane Waves that Were Measured Using the Intensity Profiles of the Membrane Components

| Label | Wavelength (μm)a | Periodicity (s)a | Velocity (μm/s) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fig. 2 B | SLB | AF488b SA/Bc | 120.15 ± 28.27 (n = 3) | 241.41 ± 10.39 (n = 4) | 0.498 |

| MinD | AF594 | ||||

| MinE | AF647 | ||||

| Fig. 2 D | SLB | AF488 SA/B AF647 | 89.91 ± 7.28 (n = 3) | 167.55 ± 12.97 (n = 6) | 0.537 |

| MinE | |||||

| Fig. 3 A | SLB | AF488 SA/B | 92.78 ± 11.21 (n = 4) | 262.21 ± 10.67 (n = 5) | 0.350 |

| MinD | AF594 | ||||

| MinE | AF647 | ||||

| Fig. 3 C | SLB | AF488 SA/B AF594 | 109.38 ± 12.92 (n = 3) | 247.73 ± 26.95 (n = 6) | 0.442 |

| MinD | |||||

| Fig. 5 Bd | SLB | rhodamine | 119.48 ± 5.15 (n = 8) | 189.16 ± 6.36 (n = 19) | 0.632 |

| SLB | BODIPY FLe | ||||

| MinE | AF647 | ||||

Mean ± standard error of the mean.

AF, Alexa Fluor.

SA/B, streptavidin/biotin-X DHPE.

Measured on the images of AF647-MinE.

BODIPY FL C12-HPC.

Streptavidin/biotin-X DHPE, green; MinD, red; MinE, cyan. The time series was taken with a 10-second interval using the wild-field fluorescence microscope system. The video frame rate is 7 fsp (frames per second). Scale bar, 100 μm; time, min:sec. This video corresponds to Fig. 2 A.

Streptavidin/biotin-X DHPE, green; MinD, red; MinE, cyan. The time series was taken with an interval set as freerun (fastest speed under a particular imaging condition; 10.85-second interval) using the confocal microscope system. The frame rate is 7 fsp. Scale bar, 100 μm; time, min:sec. This video corresponds to Fig. 2 B.

Streptavidin/biotin-X DHPE, green; MinE, cyan. The time series was taken with an interval set as freerun (9.76-second interval) using the confocal microscope system. The frame rate is 7 fsp. Scale bar, 100 μm; time, min:sec. This video corresponds to Fig. 2 C.

The observed Min protein waves showed characteristic features as described in the literature (5, 6, 7), i.e., the intensity profiles of both MinD and MinE waves were periodic, and the MinE intensity maximum was spatially positioned behind the MinD waves at the trailing edge of the waves (Fig. 2, C and E). Interestingly, the streptavidin waves interdigitated with the Min protein waves and formed staggered spatial patterns on SLBs. The kymographs also demonstrated alternating spatial and temporal distribution of the Min protein and streptavidin waves. The wave patterns were also observed when monomeric streptavidin was used in place of streptavidin, confirming that multivalency of the streptavidin homotetramers did not hamper the wave formation (Supporting Materials and Methods; Fig. S3; Video S4). In addition, the membrane component waves were recorded in the absence of the labeled proteins (Fig. S3; Video S4). Thus, the observed membrane component waves were not caused by fluorescence leakage from other channels. Taken together, the staggered spatial and temporal patterns suggested that steric repulsion occurred between the Min protein and the membrane component during wave propagation.

Monomeric Streptavidin/biotin-X DHPE, green. The time series was taken with an interval set as freerun (1.09-second interval) using the confocal microscope system. The frame rate is 7 fsp. Scale bar, 100 μm; time, min:sec. This video corresponds to Fig. S3.

The membrane component accumulated in the same direction as the Min protein wave propagated

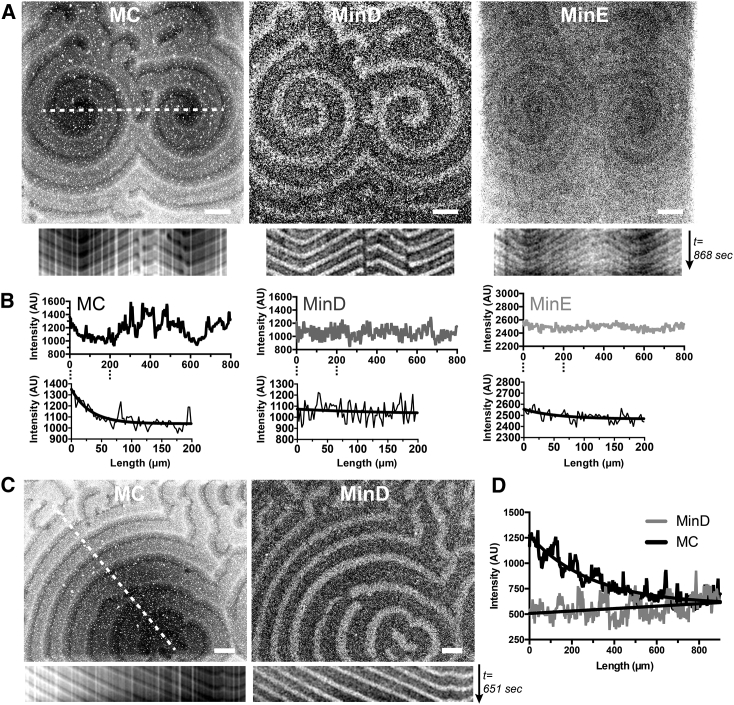

A striking feature associated with the membrane component waves was the long-range fluorescence intensity gradients (Fig. 3, A and C; Videos S5 and S6). The fluorescence intensity of streptavidin/biotin-X DHPE ascended from the center outwards in the spiral waves, which was constantly observed in the streptavidin channel after long incubation but hardly found in the protein channels. The directional accumulation of streptavidin/biotin-X DHPE was also demonstrated in the kymographs and the overall trend of the intensity profiles (Fig. 3, B and D). Because the concentration of the fluorescent streptavidin used in the experiment was below the quenching limit of the fluorophore, the fluorescence intensity was expected to be proportional to the concentration, and the spatial variation of the fluorescence intensity should represent the concentration change of streptavidin/biotin-X DHPE. Therefore, propagation of the Min protein waves could not only drive membrane components to migrate along with the proteins but also lead to the establishment of a concentration gradient of the membrane component in the membrane.

Figure 3.

The concentration gradient of the streptavidin/biotin-X DHPE within spiral waves. (A and C) Confocal micrographs of the streptavidin (MC), MinD, and MinE waves (Videos S5 and S6) are shown. Scale bars, 100 μm. Kymographs obtained along the dashed lines are shown below each micrograph. (B and D) Intensity profiles were also measured along the dashed lines marked in (A) and (C), respectively. The lower panel in (B) shows the fitted profiles within the 200-μm range using nonlinear regression to demonstrate the concentration gradient of the membrane-associating streptavidin. The fitted lines are also shown in (D).

Streptavidin/biotin-X DHPE, green; MinD, red; MinE, cyan. The time series was taken with an interval set as freerun (10.85-second interval) using the confocal microscope system. The frame rate is 7 fsp. Scale bar, 100 μm; time, min:sec. This video corresponds to Fig. 3 A.

Streptavidin/biotin-X DHPE, green; MinE, cyan. The time series was taken with an interval set as freerun (10.85-second interval) using the confocal microscope system. The frame rate is 7 fsp. Scale bar, 100 μm; time, min:sec. This video corresponds to Fig. 3 C.

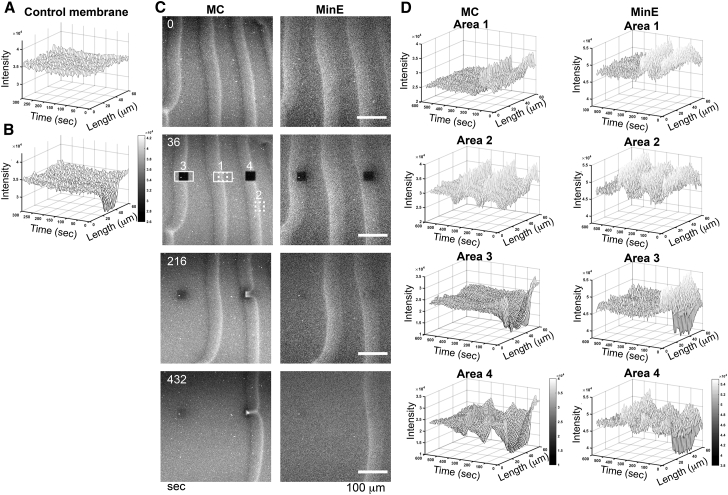

Forced migration of the membrane components by the Min protein waves

The FRAP experiments were performed to examine the idea that the membrane components were forced to migrate with the propagating Min protein waves (Fig. 4; Fig. S4; Videos S7 and S8). As demonstrated in Figs. 4 B and S4, A and B, the FRAP experiment in an ROI on an SLB doped with Alexa Fluor 488 streptavidin/biotin-X DHPE (0.5 mol%) showed gradual recovery and reached a plateau with a calculated diffusion coefficient of 3.34 ± 0.53 μm2/s and the mobile fraction of 1.02 ± 0.13 (n = 8). On the contrary, the unbleached area showed no significant fluorescence fluctuation over time (Fig. 4 A). The fluorescence recovery of ROIs on SLBs in the experiments with MinD and MinE did not follow the same trend (Fig. 4, C and D; Fig. S4 C; and Video S7). The temporal profiles of the unbleached areas (areas 1 and 2) showed that the peak MinE fluorescence always followed the peak fluorescence of the membrane component with a time delay. This time delay was caused by MinD that attached to the membrane in waves, as suggested by the temporal distribution of the MinD wave that was flanked by the peak intensity of the membrane component wave at the front end and the peak intensity of the MinE wave at the trailing end (Figs. 2 B and S4 D). In the cases of the waves traveling across the imaging field without succeeding waves, the drastic fluorescence fluctuation associating with the waves could no longer occur after the waves passed by. In the photobleaching experiments targeting waves (Fig. 4, C and D; Fig. S4 C, areas 3 and 4), the succeeding waves coming through the bleached ROIs could quickly recover the fluorescence to a level higher than the original intensity. The temporal wave patterns of both membrane component and MinE were recovered afterwards, but the subsequent waves could slow down and change patterns in the bleached areas (area 4). In addition, the membrane fluorescence was maintained at constant intensity after the traveling waves passed by (area 3), which was similar to the observation made in area 1. For unknown reasons, the fluorescence decay associated with the SLB was slowed down with the propagating Min protein waves (Fig. S4, B and C, area 1 and 3). In brief, the photobleaching experiments further supported that the membrane components were forced to move along with the Min protein waves.

Figure 4.

Forced migration of the MCs by the Min protein waves. (A and B) Surface plots of SLBs before (A) and after (B) photobleaching are shown to demonstrate the spatiotemporal changes of the fluorescence intensity in the absence of the Min proteins. See also Fig. S4, A and B. (C) Selected frames of a sample FRAP experiment targeting both MC and MinE waves are shown. See Video S7. (D) Four different areas were selected for analysis: areas 1 and 2, no photobleach applied; areas 3 and 4, photobleach applied. The dashed-line squares mark the bleached ROIs. The rectangles mark the areas that were used to generate the surface plots.

Membrane component, green; MinE, cyan. The time series was taken with an interval set as 6 seconds using the confocal microscope system. Five frames were taken before photobleaching. The frame rate is 7 fsp. Scale bar, 100 μm; time, min:sec. This video corresponds to Fig. 4, C and D and Fig. S4 C.

Rhodamine DHPE, red; BODIPY FL C12-HPC, green; MinE, cyan. The time series was taken with a 6-second interval using the confocal microscope system. The frame rate is 7 fsp. Scale bar, 100 μm; time, min:sec. This video corresponds to Fig. 4 B.

The steric property of membrane component contributed to the wave formation

We proposed that self-organization of MinDE on the membrane plane can generate steric pressure to produce the membrane component waves. The spatial difference of the steric pressure imposed on the membrane provides the driving force to move the membrane component. The local steric pressure, which is generated by the motion of MinD and MinE detaching from or inserting into the membrane, is applied not only on the membrane but also in the space above the membrane. Therefore, a regular lipid without a soluble region extending above the membrane can still experience the steric pressure in the membrane caused by detachment and attachment of the Min proteins. The same motion of the Min proteins can also impose steric pressure in the space above the membrane, i.e., the membrane component can experience additional steric pressure coming from the soluble portion extending above the membrane that crowd the corresponding space. Thus, the membrane components carry similar membrane anchors, but larger soluble regions are more sensitive to the steric pressure coming from the space above the membrane.

Therefore, the soluble region of a membrane component faces the repulsive force coming from the Min proteins to induce fluxes of the membrane component. The hypothesis predicts that a larger soluble region faces larger repulsive force, which facilitates formation of the induced flux and establishment of a directional accumulation of the membrane component. The possible contribution coming from nonspecific interaction between the Min proteins and the membrane component was excluded by the observation that the membrane component tended to accumulate at the regions where there were fewer Min proteins.

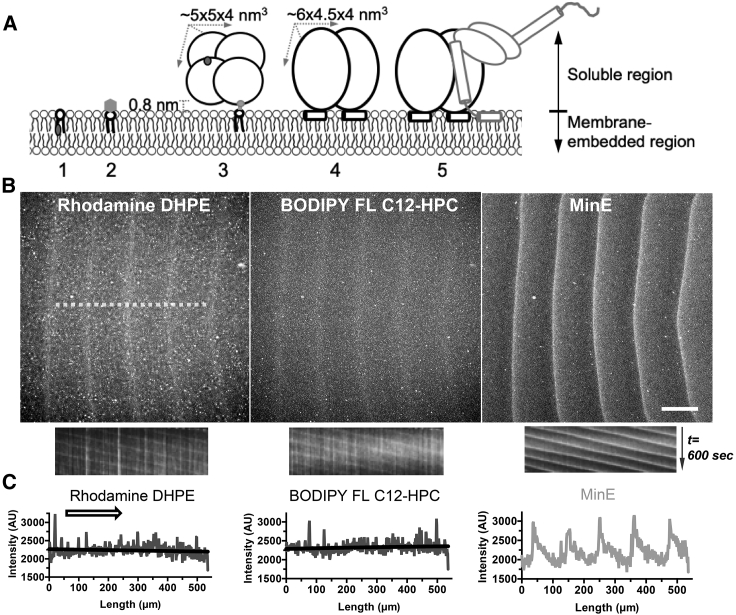

To examine influence of the soluble region in a membrane component, we studied the headgroup-labeled rhodamine DHPE (rhodamine 360.4 Da) and the fatty-acid-tail-labeled BODIPY FL C12-HPC, which had an unmodified choline headgroup (87.2 Da), for comparison with Alexa Fluor 488 streptavidin (∼53 KDa) that was bound with the headgroup-labeled biotin-X DHPE (Fig. 5 A). Although BODIPY FL was conjugated at one of the two fatty acid tails at the C12 position of HPC, the chain length of the other lipid tail was the same as the lipid tails of other membrane components (16:0). Thus, the major difference between these membrane components resided in the soluble regions that differed in their structure and size. All three membrane components had similar diffusion coefficients (D) between 1.62 and 3.35 μm2/s as measured by FRAP experiments (Table 2).

Figure 5.

The steric property of the MC is critical for the wave formation. (A) An illustration of the steric difference between MCs and the Min proteins is shown: 1) BODIPY FL C12-HPC; 2) rhodamine DHPE; 3) biotin-X DHPE/Alexa Fluor 488 streptavidin; 4) MinD dimer on the membrane surface; 5) MinD-MinE complex on the membrane surface. (B) The waves of both rhodamine DHPE and BODIPY FL C12-HPC were observed simultaneously along with the MinE waves, but no directional accumulation of the MC was identified. See Video S8. Scale bars, 100 μm. (C) The corresponding intensity profiles and the fitted lines are shown. The kymographs and spatial profiles were obtained along the dashed line labeled in (B). The arrow indicates the direction of wave propagation.

Table 2.

Diffusivity of Membrane Components in the DOPC/DOPG Bilayers

| Membrane Component | Diffusivity (μm2/s)a | Mobile Fraction |

|---|---|---|

| Alexa Fluor 488 streptavidin/biotin-X DHPE (0.5 mol%) | 3.35 ± 0.08 (n = 36) | 1 |

| Rhodamine DHPE (0.125 mol%)b | 1.62 ± 0.02 (n = 63) | 1 |

| BODIPY FL C12-HPC (0.5 mol%)b | 2.22 ± 0.02 (n = 63) | 1 |

Mean ± standard error of the mean.

Two lipid species were studied simultaneously as described for Fig. 5.

In Fig. 5 B and Video S8, the waves of both rhodamine DHPE and BODIPY FL C12-HPC were observed in the colocalization experiments with MinE (Fig. 5 B). Although the spatiotemporal features of the MinE waves resembled those observed in Figs. 2 and 3, the membrane component waves were less clear, and the directional accumulation of rhodamine DHPE or BODIPY FL C12-HPC was not found (Fig. 5 C). Because all three membrane components had similar diffusivity, the poor ability of rhodamine DHPE and BODIPY FL C12-HPC to form waves and to establish a concentration gradient could be attributed to the relatively small soluble regions that faced weaker steric repulsive force from the Min proteins.

A kinetic model of the membrane component waves

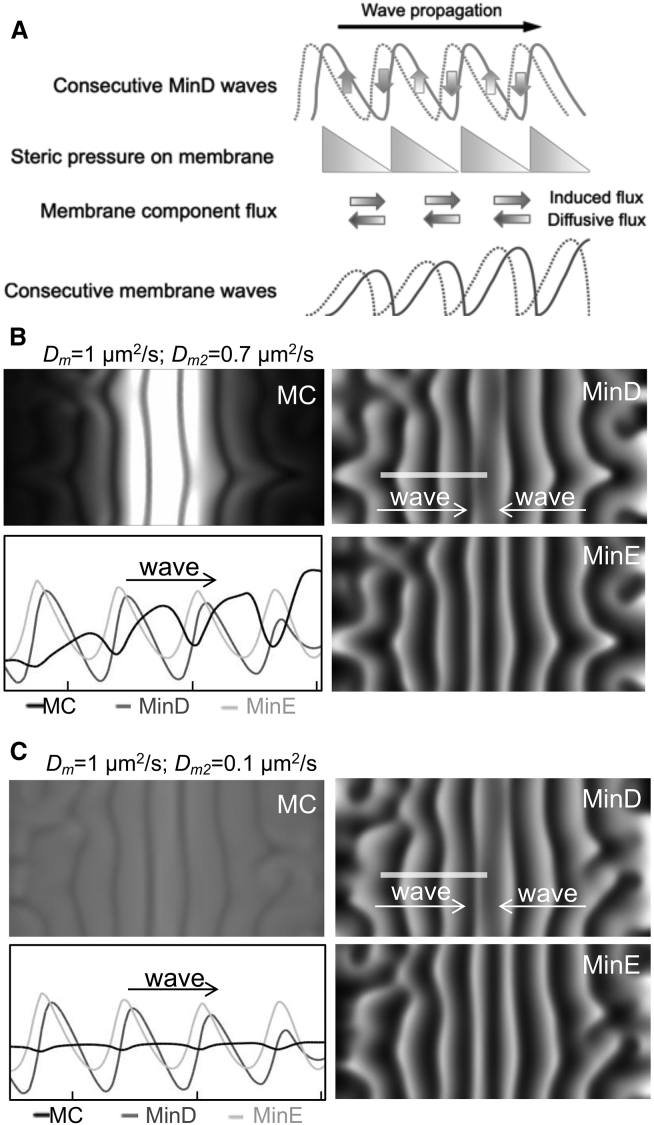

Fig. 6 A illustrates the proposed mechanism by which propagation of the Min protein waves induce bulk transport of the membrane component in the membrane by steric repulsion. When the Min protein waves propagate with time, the steric pressure at the leading edge of the protein waves increases with time, but the steric pressure toward the trailing edge of the protein waves decreases with time. Therefore, the corresponding membrane component waves are formed by the continual increase of the steric pressure behind the membrane component waves to push the components forward. This is coupled with the continual release from the steric pressure in front of the membrane component waves to drag them forward. The spatiotemporal variation of the steric pressure imposed by the Min proteins causes membrane components to locate in the region between the crests of the Min protein waves. The phenomenon resembles the linear peristaltic pumping process by which the fluid body is delivered forward by the mechanical parts continually to impose the pressure behind and to release the pressure in front of a fluid body.

Figure 6.

Formation of the MC waves can be influenced by varying diffusivity (Dm) and repulsed ability (Dm2) as demonstrated by the numerical simulation. (A) An illustration of the mechanism by which propagation of the Min protein waves induce transport of the MC is given. The competition between the induced flux and the diffusive flux of the MC determines the concentration within a local area, which further influences the overall distribution of the component in the membrane. (B and C) Simulation results to compare the MCs that have the same diffusivity in the membrane but show different repulsed abilities because different steric properties of the soluble regions are given. The simulated waves propagate toward the center of the boxed area. See Video S9.

We developed a numerical model to describe the physical principles of steric repulsion that underlies the formation of the membrane component waves. An assumption that the membrane component can be expelled by MinD and MinDE complexes on the membrane was introduced to correlate the membrane component with the Min proteins (Fig. 1; see also Materials and Methods). Therefore, lateral movement of the membrane component can be attributed not only to its own diffusion but also to the steric repulsion caused by MinD and MinDE complexes, as shown in Eq. 7.

| (7) |

In Eq. 7, jnet is the net flux of the membrane component, jdiffusion is the diffusive flux caused by the concentration gradient of the membrane component, and jsteric repulsion is the flux induced by the steric repulsion caused by the Min proteins (Fig. 6 A). The diffusive flux of the membrane component due to diffusion in a fluid membrane can be described by 2-D Fick’s law, in which the diffusive flux is represented as the concentration gradient multiplied by the diffusivity, Dm, of the membrane component in the fluid membrane (25, 26). The constant, Dms, defines the induced flux as the amount of the membrane component that can be transported per unit of the steric pressure gradient and per unit of the normalized concentration of the membrane component. Thus, the constant representing the repulsed ability, Dm2, is equal to Dms multiplied by how much the steric pressure can be generated by per unit concentration of MinDE and MinD on the membrane.

As proposed earlier in this section, attachment and detachment of the Min proteins on the membrane surface can generate steric pressure. The spatial difference of the steric pressure, which is directly proportional to the summation of MinD and MinDE concentrations on the membrane, drives the membrane component to move (Figs. 1 and 6 A). In addition, local concentration of the membrane component matters, i.e., the more membrane component that exists, the more that will be repulsed in a local area. Therefore, the induced flux of the membrane component is proportional to the magnitude of the steric pressure gradient multiplied by the local concentration of the component. The proportionality is set as Dm2, representing the repulsed ability of the component (Eq. 7). Dm2 can also be understood as the way that the membrane component responds to the steric pressure, which can be correlated to the geometric features of the membrane component and the Min proteins. Because the steric properties of the Min proteins should be fixed in experiments of different membrane components, Dm2 will be majorly influenced by the geometric property of the membrane component.

Note that where there is steric pressure from MinD and MinDE complexes imposing on the membrane component, there should be also steric pressure from the membrane component to the MinD and MinDE complexes on the membrane. Therefore, extra terms regarding the steric pressure from the membrane component to MinDE and MinD on the membrane plane are introduced in the mass balance equations (Eqs. 4 and 5). Here, we assumed that influence of the steric pressure coming from the membrane component to MinDE and MinD bound on the membrane is small in comparison with other kinetic or diffusion terms in Eqs. 4 and 5. The assumption is supported by the resemblance between the MinD and MinE concentration profiles on the membrane with the presence of the membrane component in this study and the protein concentration profiles without the membrane component reported by Loose et al. (5) and Vecchiarelli (10). The supporting features include 1) periodic spatial patterns of the MinD and MinE waves, 2) asymmetrical profiles of MinD and MinE with the concentration maximums leaning toward the trailing edges of the waves, and 3) shallow linear rise and sharp decline of the MinE concentration profile at the trailing edge of the waves. Based on these reasons, we assumed that additional influence of the steric pressure coming from the membrane component on the Min proteins does not significantly alter their concentration distribution and therefore could be small in comparison with other terms in the mass balance equations. This assumption remains to be verified in the near future.

The simulated membrane component waves resembled the experimental observations

The simulated membrane component waves induced by the Min proteins were solved using the kinetic equations Eqs. 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, and 7 and the parameters listed in Table 3. The simulation results showed consistent features with the experimental observations of the Min protein waves as well as the corresponding membrane component waves (Fig. 6, B and C). Importantly, whereas the Min proteins showed a trend of constant concentration across waves, the membrane component showed a trend of increasing concentration following the direction of wave propagation (Fig. 6 B). The result supported the idea that the membrane component was transported along with the propagating Min protein waves.

Table 3.

The Parameters in the 2-D Min Dynamic Model

| Parameter | Unit | |

|---|---|---|

| CD0 | 48,000 | #/μm2 |

| CE0 | 55,920 | #/μm2 |

| DD | 60 | μm2/s |

| DE | 60 | μm2/s |

| Dd | 1.2 | μm2/s |

| Dde | 0.4 | μm2/s |

| De | 1.2 | μm2/s |

| kD | 0.48 | 1/s |

| kde | 8.65E−05 | μm2/s |

| kdE | 8.52E−07 | μm2/s |

| ke | 0.3 | 1/s |

| Cm0 | 5000 | #/μm2 |

The symbol “#” indicates the number of protein molecules. CD0: the initial concentration of MinD in the system; CE0: the initial concentration of MinE in the system; Cm0: the averaged concentration or the initial concentration of membrane component in the system.

Furthermore, the structure and size differences between the soluble regions of different membrane components could explain the discrepancy between membrane component waves of Alexa Fluor 488 streptavidin/biotin-X DHPE, rhodamine DHPE, and BODIPY FL C12-HPC (Fig. 5 A). According to our hypothesis, the membrane component with a larger soluble region could face higher steric pressure to induce a larger flux, thus associating with a greater repulsed ability, Dm2. The simulation results demonstrated that when Dm2 was set around 0.7 μm2/s to represent the repulsed ability of Alexa Fluor 488 streptavidin/biotin-X, the simulated component waves matched the experimental observations (Fig. 6 B). Meanwhile, when Dm2 was decreased to 0.1 μm2/s to represent the repulsed ability of rhodamine and choline in the simulation and Dm remained the same, the wave amplitude and the spatial accumulation became weak, which was consistent with the experimental observations (Fig. 6 C).

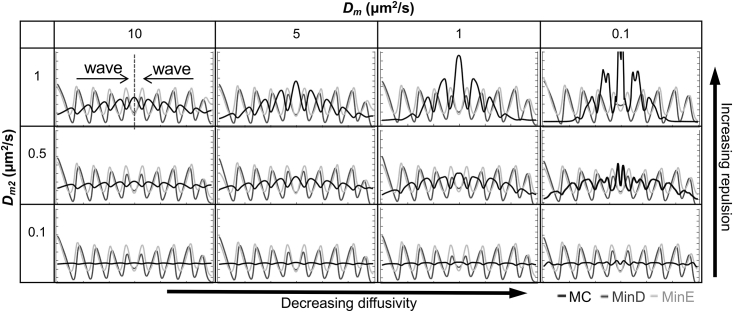

The geometric property of the membrane component influenced its spatial distribution

Our model demonstrates that distribution of the membrane component is influenced by two parameters: the diffusivity (Dm) and the repulsed ability (Dm2) (Eq. 6). Whereas Dm describes how fast a membrane component can spread, Dm2 describes how a membrane component can respond to the steric pressure, which is directly correlated with the geometric properties of both the membrane component and the Min proteins. However, the conformational changes of MinD and MinE during wave propagation should follow the same recurring patterns; thus, the contribution of the geometric property of Min proteins to local steric pressure is considered constant during wave propagation. Therefore, Dm2 is majorly influenced by the geometric property of the membrane component.

Based on these assumptions, we used the kinetic model to investigate different combinations of diffusivity and repulsed ability on the membrane component wave formation (Fig. 7). We studied Dm of 10, 5, and 1 μm2/s, because the diffusivity of typical lipids is in the range of 1–10 μm2/s (27), and the experimental diffusivity of membrane components was between 1.62 and 3.35 μm2/s (Table 2). In addition, the diffusivities of the lipid-anchored peripheral membrane proteins (28) and the Min proteins (18) (Table 3) were reported in the same range. Therefore, the Dm value of 10 μm2/s was introduced to mimic hypothetical components that diffuse faster in the membrane, and the Dm value of 0.1 μm2/s was studied to mimic components that diffuse more slowly in the membrane. Meanwhile, the repulsed ability Dm2 was set to 1, 0.5, and 0.1 μm2/s. Among them, the Dm2 value of 1 μm2/s was used to mimic components with a large soluble region that faced greater repulsive force under a fixed steric pressure gradient. On the contrary, the Dm2 value of 0.1 μm2/s was used to mimic components with a small soluble region that faced less repulsive force.

Figure 7.

The diffusivity (Dm) and the repulsed ability (Dm2) of an MC are the critical factors contributing to the Min protein-induced steric pressure and hence MC waves in the membrane.

Snapshots of the simulated concentration profiles are shown in Fig. 7, which represented two opposing Min protein waves propagated from both left and right sides toward the center. The results demonstrated that higher Dm2 led to clearer membrane component waves when Dm was fixed because higher Dm2 would mean that more membrane components were repulsed by the unit steric pressure gradient. Under this condition, the membrane component was transported in the membrane along with the wave propagation that led to accumulation of the component at the center where two opposing waves collided. Although the trend of the protein concentration remained constant with time, a concentration gradient of the component occurred along with the wave propagation with time, which further caused directional accumulation of the component. On the contrary, the membrane component waves became unclear with a small Dm2 value because a membrane component with a smaller soluble region faced less repulsive force per unit steric pressure gradient. The directional accumulation also became unclear because the induced flux from the steric pressure is not large enough to overcome the diffusive flux. Meanwhile, because faster diffusion or increasing diffusive flux tended to counteract with the directional transport of the components, the amplitude of the membrane component waves and the spatial accumulation of components became weaker in correspondence with increasing Dm values. Taken together, active transport of the membrane component by the Min proteins is caused by a balance between the membrane component flux induced by the Min protein dynamics, which is determined by the magnitude of the repulsed ability of the component, Dm2, and the magnitude of the diffusive flux of the component in the membrane, Dm.

Discussion

To the best of our knowledge, this study reports a new mechanism that the biological reactions occurring on the membrane surface can coordinate physical processes to transport and distribute the components in the membrane. The mechanism is demonstrated by the propagating Min protein waves formed by protein self-organization on the membrane surface to actively transport the lipid-anchored membrane components. The forced movement of the membrane components by the Min protein waves is supported by analyses of the spatiotemporal patterns and the FRAP experiments of the waves. The amount of the fluorescent membrane components showed periodic increase and drop in both spatial and temporal profiles in the presence of the Min protein waves (Fig. 4, C and D, areas 1 and 2; Fig. S4 C; Video S7), which was in contrast to the constant amount of the components without the Min proteins (Fig. 4 A; Fig. S4, A and B). Importantly, the corresponding patterns of MinE always appeared behind the membrane component waves, supporting the idea that the membrane-bound state of MinDE and MinD in the waves could drive the membrane components to migrate along with the wave propagation. Meanwhile, the membrane component waves were able to surpass the normal fluorescence recovery pattern of the lipid bilayer in the FRAP experiments targeting the waves (Fig. 4, C and D, areas 3 and 4; Fig. S4 C; Video S7). The corresponding MinE channel followed similar recovery patterns of the membrane component but with a time delay and a spatial difference. The FRAP results strongly suggested that the Min protein waves not only drive migration of the membrane components but also can overtake random diffusion in the membrane. In addition, the periodic spatial and temporal patterns of both membrane component and MinE waves ceased when there was no succeeding wave behind (Fig. 4, C and D, areas 1 and 3; Fig. S4 C; Video S7). This observation further supported that the appearance of the membrane component waves depended on the Min protein waves.

Therefore, we proposed that steric pressure caused by the Min proteins may induce the observed lateral transport of the membrane component. When the Min protein waves propagate, the local concentration of the Min proteins changes with time, which causes corresponding changes of the steric pressure in the membrane to induce a flux of the membrane component. In the meantime, the membrane component diffuses in the membrane owing to its intrinsic properties (Fig. 6 A). When the induced flux is much larger than the diffusive flux, the membrane component can be transported in bulk along with the propagating Min protein waves. This directional transport can lead to considerable accumulation of the component at the position where there is a barrier to halt transportation (Figs. 3 A, 6 B, and 7). The directional accumulation of the membrane component is contrasted with the Min proteins that do not accumulate on the membrane surface. This is explained by the fact that MinD and MinE undergo continuous cycles of attachment to and detachment from the membrane, but the membrane component migrates passively and stays in the membrane during wave propagation. Therefore, the membrane component can be continuously transported by the Min protein waves and accumulate alongside the wave propagation. The phenomenon is highlighted in the spiral waves, in which the component not only showed directional accumulation but also formed concentration gradients within the spiral patterns (Fig. 3 A). On the contrary, our simulation results demonstrated that a strong diffusive flux of the membrane component can counteract with the directional accumulation of the component, resulting in even distribution of the component in the membrane (Fig. 7).

The numerical model also demonstrated that the Min protein-induced membrane component waves can be influenced by the steric property of the soluble region of a membrane component, which is directly proportional to the repulsed ability. The simulation results were supported by experiments shown in Fig. 5. In other words, the stronger the steric effect of the soluble region is, the more the component can be influenced by the Min-protein-induced steric pressure. In addition, the diffusivity of a membrane component, which is mainly determined by the way that it associates with the membrane, can influence the effectiveness of the Min proteins to induce the formation of the membrane component waves.

The proposed steric repulsion mechanism is different from molecular crowding, although both mechanisms involve volume exclusion and steric constraints. The differences are summarized into the following points. Firstly, the physicochemical principles that underlie self-organization of the Min proteins are distinctly different from the protein-mediated molecular crowding on the membrane surface (29). An apparent difference is the spontaneous order during self-organization of the Min proteins, which differentiates the process from crowding. Secondly, the Min proteins in the propagating waves organize into a concentration gradient that can introduce a corresponding steric pressure gradient on the membrane and cause directional movement of the membrane components. In contrast, directional transport is not an intrinsic property of molecular crowding. Thirdly, active transport of the membrane component induced by the Min protein dynamics—instead of membrane deformation, phase separation, or displacement of weak membrane-associating proteins caused by the crowding effects—is central to this study.

The staggered spatiotemporal distribution of the Min protein and membrane component waves reported in this study is reminiscent of the counteroscillation of the Min proteins and the cytoskeletal protein FtsZ in vivo and the antiphase distribution of the Min proteins and FtsZ on SLBs in vitro (30, 31). However, direct protein-protein interaction exists between MinC and FtsZ that leads to an antagonistic effect of their distribution on the membrane. This mechanism is fundamentally different from the mechanism by which the membrane component waves were induced by the steric pressure imposed by the Min proteins. Owing to the involvement of the Min proteins in the cell division process, it will be of great interest to investigate whether the Min system could transport other cell division proteins by means of steric repulsion. Furthermore, an intriguing implication based on this study is that the Min system may use the steric repulsion mechanism to segregate the membrane components and maintain their heterogeneous distribution in the membrane, which further localizes specific physiological events inside a cell.

The finding of the membrane component waves induced by the Min proteins in vitro brought our attention back to the fact that MinD belongs to the deviant form of the Walker type ATPase family of proteins (32), which has long been implicated in partitioning cellular components, thus influencing their subcellular localization in vivo (33). MinD of the Min system interacts with MinE to partition the division inhibitor MinC to the cell poles and knocks FtsZ off the membrane to prevent aberrant division. ParA of the Par system, which is a member of the same MinD/ParA family of proteins and interacts with ParB, segregates plasmids or chromosomes into dividing daughter bacteria. An interesting difference between the two systems is the interaction surface. The Min system acts on the membrane, and the Par system acts on DNA. Both systems have been reconstituted in vitro to demonstrate the synthetic and physical principles underlying the systems (5, 34, 35). Mechanistically, the Brownian ratchet model was proposed to underlie the transport of the plasmid cargos on the nucleoid surface by the dynamic Par system (36, 37). It was also proposed that the Min oscillation may have a role in chromosome segregation using the Brownian ratchet mechanism through nonspecific interaction with DNA (38). In these models, the membrane or nucleoid surface provides a platform for tethering the motor-like MinD or ParA protein to translocate DNA molecules through activation of ATP hydrolysis by MinE or ParB, respectively. In this study, the transport cargo of the Min system is the constituent of the membrane, and the steric repulsion mechanism occurs right on the membrane surface. There is no stepping motion of the Min proteins on the membrane that would involve conformational changes to transduce the mechanical force for the cargo transport. The membrane itself is a fluid that directly responds to the external force introduced by attachment and detachment of the Min proteins occurring on the membrane surface. In addition, conversion of the chemical energy coming from ATP hydrolysis in MinD does not contribute to the steric repulsion for transport of the membrane component. Therefore, our study provides, to our knowledge, not only the evidence of a new function of the Min system but also a new mechanism for the transport of biological molecules on the membrane surface.

Author Contributions

Y.-L.S. and L.C. conceived, designed, performed experiments, analyzed data, and wrote the manuscript. L.-T.H. and B.-F.L. conceived and performed the simulation experiments. Y.-M.T. and C.Y.H. conceived and performed the initial reconstitution experiments. Z.-X.L. performed experiments and analyzed data. J.-S.C. performed experiments. Y.-C.B., H.-L.L., Y.-P.S., and M.-F.H. contributed to the protein production.

Acknowledgments

We thank the technical supports from Mei-Yi Chen of the TIGP-CBMB program of Academia Sinica, Taiwan, Meng-Ru Ho at the Biophysical core facility, and Chin-Chun Hung at the Imaging core facility of the Institute of Biological Chemistry, Academia Sinica, and Wan-Chen Huang at the Single-Molecule Biology core lab of the Institute of Cellular and Organismic Biology, Academia Sinica.

This work was supported by the Ministry of Science and Technology, Taiwan (102-2311-B-001-020-MY3 to Y.-L.S. and 105-2628-E-002-015-MY3 to L.C.), a Career Development grant from National Taiwan University, Taiwan (NTU-CDP-107L7725) to L.C., and a National Taiwan University and Academia Sinica Joint Program grant (08/2015–12/2016) and a Thematic Project grant from Academia Sinica, Taiwan (AS-TP-106-L04) to Y.-L.S. (AS-TP-106-L04-04) and L.C. (AS-TP-106-L04-01).

Editor: Tobias Baumgart.

Footnotes

Ling-Ting Huang and Yu-Ming Tu contributed equally to this work.

Supporting Material can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bpj.2019.03.011.

A video abstract is available at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bpj.2019.03.011#mmc11.

Contributor Information

Yu-Ling Shih, Email: ylshih10@gate.sinica.edu.tw.

Ling Chao, Email: lingchao@ntu.edu.tw.

Supporting Material

References

- 1.de Boer P.A., Crossley R.E., Rothfield L.I. Isolation and properties of minB, a complex genetic locus involved in correct placement of the division site in Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol. 1988;170:2106–2112. doi: 10.1128/jb.170.5.2106-2112.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Raskin D.M., de Boer P.A. Rapid pole-to-pole oscillation of a protein required for directing division to the middle of Escherichia coli. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1999;96:4971–4976. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.9.4971. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Raskin D.M., de Boer P.A. MinDE-dependent pole-to-pole oscillation of division inhibitor MinC in Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol. 1999;181:6419–6424. doi: 10.1128/jb.181.20.6419-6424.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fu X., Shih Y.L., Rothfield L.I. The MinE ring required for proper placement of the division site is a mobile structure that changes its cellular location during the Escherichia coli division cycle. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2001;98:980–985. doi: 10.1073/pnas.031549298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Loose M., Fischer-Friedrich E., Schwille P. Spatial regulators for bacterial cell division self-organize into surface waves in vitro. Science. 2008;320:789–792. doi: 10.1126/science.1154413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ivanov V., Mizuuchi K. Multiple modes of interconverting dynamic pattern formation by bacterial cell division proteins. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2010;107:8071–8078. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0911036107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Vecchiarelli A.G., Li M., Mizuuchi K. Membrane-bound MinDE complex acts as a toggle switch that drives Min oscillation coupled to cytoplasmic depletion of MinD. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2016;113:E1479–E1488. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1600644113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zieske K., Schwille P. Reconstitution of pole-to-pole oscillations of min proteins in microengineered polydimethylsiloxane compartments. Angew. Chem. Int.Engl. 2013;52:459–462. doi: 10.1002/anie.201207078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zieske K., Schwille P. Reconstituting geometry-modulated protein patterns in membrane compartments. Methods Cell Biol. 2015;128:149–163. doi: 10.1016/bs.mcb.2015.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Vecchiarelli A.G., Li M., Mizuuchi K. Differential affinities of MinD and MinE to anionic phospholipid influence Min patterning dynamics in vitro. Mol. Microbiol. 2014;93:453–463. doi: 10.1111/mmi.12669. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wu F., van Schie B.G., Dekker C. Symmetry and scale orient Min protein patterns in shaped bacterial sculptures. Nat. Nanotechnol. 2015;10:719–726. doi: 10.1038/nnano.2015.126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Schweizer J., Loose M., Schwille P. Geometry sensing by self-organized protein patterns. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2012;109:15283–15288. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1206953109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Meinhardt H., de Boer P.A. Pattern formation in Escherichia coli: a model for the pole-to-pole oscillations of Min proteins and the localization of the division site. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2001;98:14202–14207. doi: 10.1073/pnas.251216598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Howard M., Rutenberg A.D., de Vet S. Dynamic compartmentalization of bacteria: accurate division in E. coli. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2001;87:278102. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.87.278102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kruse K. A dynamic model for determining the middle of Escherichia coli. Biophys. J. 2002;82:618–627. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(02)75426-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Huang K.C., Meir Y., Wingreen N.S. Dynamic structures in Escherichia coli: spontaneous formation of MinE rings and MinD polar zones. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2003;100:12724–12728. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2135445100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bonny M., Fischer-Friedrich E., Kruse K. Membrane binding of MinE allows for a comprehensive description of Min-protein pattern formation. PLoS Comput. Biol. 2013;9:e1003347. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1003347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Petrasek Z., Schwille P. Simple membrane-based model of the Min oscillator. New J. Phys. 2015;17:043023. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Walsh J.C., Angstmann C.N., Curmi P.M. Molecular interactions of the min protein system reproduce spatiotemporal patterning in growing and dividing Escherichia coli cells. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0128148. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0128148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wettmann L., Bonny M., Kruse K. Effects of geometry and topography on Min-protein dynamics. PLoS One. 2018;13:e0203050. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0203050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lee H.L., Chiang I.C., Shih Y.L. Quantitative proteomics analysis reveals the Min system of Escherichia coli modulates reversible protein association with the inner membrane. Mol. Cell. Proteomics. 2016;15:1572–1583. doi: 10.1074/mcp.M115.053603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hsieh C.W., Lin T.Y., Shih Y.L. Direct MinE-membrane interaction contributes to the proper localization of MinDE in E. coli. Mol. Microbiol. 2010;75:499–512. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2009.07006.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sambrook J., Russell D. Cold Spring Harbor Press; Cold Spring Harbor, NY: 2006. The Condensed Protocols from Molecular Cloning: A Laboratory Manual. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Han C.T., Chao L. Creating air-stable supported lipid bilayers by physical confinement induced by phospholipase A2. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces. 2014;6:6378–6383. doi: 10.1021/am405746g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ladha S., Mackie A.R., Duclohier H. Lateral diffusion in planar lipid bilayers: a fluorescence recovery after photobleaching investigation of its modulation by lipid composition, cholesterol, or alamethicin content and divalent cations. Biophys. J. 1996;71:1364–1373. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(96)79339-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Fahey P.F., Koppel D.E., Webb W.W. Lateral diffusion in planar lipid bilayers. Science. 1977;195:305–306. doi: 10.1126/science.831279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Machán R., Hof M. Lipid diffusion in planar membranes investigated by fluorescence correlation spectroscopy. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2010;1798:1377–1391. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamem.2010.02.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ziemba B.P., Falke J.J. Lateral diffusion of peripheral membrane proteins on supported lipid bilayers is controlled by the additive frictional drags of (1) bound lipids and (2) protein domains penetrating into the bilayer hydrocarbon core. Chem. Phys. Lipids. 2013;172–173:67–77. doi: 10.1016/j.chemphyslip.2013.04.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Guigas G., Weiss M. Effects of protein crowding on membrane systems. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2016;1858:2441–2450. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamem.2015.12.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bisicchia P., Arumugam S., Sherratt D. MinC, MinD, and MinE drive counter-oscillation of early-cell-division proteins prior to Escherichia coli septum formation. MBio. 2013;4 doi: 10.1128/mBio.00856-13. e00856–e13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zieske K., Schwille P. Reconstitution of self-organizing protein gradients as spatial cues in cell-free systems. eLife. 2014;3:e03949. doi: 10.7554/eLife.03949. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Koonin E.V. A superfamily of ATPases with diverse functions containing either classical or deviant ATP-binding motif. J. Mol. Biol. 1993;229:1165–1174. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1993.1115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Michie K.A., Löwe J. Dynamic filaments of the bacterial cytoskeleton. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 2006;75:467–492. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.75.103004.142452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Loose M., Kruse K., Schwille P. Protein self-organization: lessons from the min system. Annu. Rev. Biophys. 2011;40:315–336. doi: 10.1146/annurev-biophys-042910-155332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Vecchiarelli A.G., Neuman K.C., Mizuuchi K. A propagating ATPase gradient drives transport of surface-confined cellular cargo. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2014;111:4880–4885. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1401025111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Vecchiarelli A.G., Mizuuchi K., Funnell B.E. Surfing biological surfaces: exploiting the nucleoid for partition and transport in bacteria. Mol. Microbiol. 2012;86:513–523. doi: 10.1111/mmi.12017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hu L., Vecchiarelli A.G., Liu J. Brownian ratchet mechanism for faithful segregation of low-copy-number plasmids. Biophys. J. 2017;112:1489–1502. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2017.02.039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Di Ventura B., Knecht B., Sourjik V. Chromosome segregation by the Escherichia coli Min system. Mol. Syst. Biol. 2013;9:686. doi: 10.1038/msb.2013.44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Streptavidin/biotin-X DHPE, green; MinD, red; MinE, cyan. The time series was taken with a 10-second interval using the wild-field fluorescence microscope system. The video frame rate is 7 fsp (frames per second). Scale bar, 100 μm; time, min:sec. This video corresponds to Fig. 2 A.

Streptavidin/biotin-X DHPE, green; MinD, red; MinE, cyan. The time series was taken with an interval set as freerun (fastest speed under a particular imaging condition; 10.85-second interval) using the confocal microscope system. The frame rate is 7 fsp. Scale bar, 100 μm; time, min:sec. This video corresponds to Fig. 2 B.

Streptavidin/biotin-X DHPE, green; MinE, cyan. The time series was taken with an interval set as freerun (9.76-second interval) using the confocal microscope system. The frame rate is 7 fsp. Scale bar, 100 μm; time, min:sec. This video corresponds to Fig. 2 C.

Monomeric Streptavidin/biotin-X DHPE, green. The time series was taken with an interval set as freerun (1.09-second interval) using the confocal microscope system. The frame rate is 7 fsp. Scale bar, 100 μm; time, min:sec. This video corresponds to Fig. S3.

Streptavidin/biotin-X DHPE, green; MinD, red; MinE, cyan. The time series was taken with an interval set as freerun (10.85-second interval) using the confocal microscope system. The frame rate is 7 fsp. Scale bar, 100 μm; time, min:sec. This video corresponds to Fig. 3 A.

Streptavidin/biotin-X DHPE, green; MinE, cyan. The time series was taken with an interval set as freerun (10.85-second interval) using the confocal microscope system. The frame rate is 7 fsp. Scale bar, 100 μm; time, min:sec. This video corresponds to Fig. 3 C.

Membrane component, green; MinE, cyan. The time series was taken with an interval set as 6 seconds using the confocal microscope system. Five frames were taken before photobleaching. The frame rate is 7 fsp. Scale bar, 100 μm; time, min:sec. This video corresponds to Fig. 4, C and D and Fig. S4 C.

Rhodamine DHPE, red; BODIPY FL C12-HPC, green; MinE, cyan. The time series was taken with a 6-second interval using the confocal microscope system. The frame rate is 7 fsp. Scale bar, 100 μm; time, min:sec. This video corresponds to Fig. 4 B.

Membrane component, green; MinD, red; MinE, cyan. Left panel: diffusivity Dm = 1 μm2/s, repulsed ability Dm2 = 0.7 μm2/s; right panel: Dm = 1 μm2/s, Dm2 = 0.1 μm2/s. The simulation time was 1000 seconds. The movie is presented with a 4-second interval and the frame rate is 33 fsp. The left and right panels correspond to Fig. 5, C and D, respectively.