Abstract

Combination antiretroviral therapy (cART) regimens are recommended for HIV patients to better achieve and maintain plasma viral suppression. Despite adequate plasma viral suppression, HIV persists inside the brain, which is, in part thought to result from poor brain penetration of antiretroviral drugs. In this study, a simple and ultra-sensitive liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS) method for simultaneous determination of tenofovir, emtricitabine, and dolutegravir in cell lysates of an immortalized human brain microvascular endothelial cell line (hCMEC/D3) was developed and validated. Analytes were separated on a reverse phase C18 column using water and 0.1% formic acid in acetonitrile as mobile phases. The analytes were detected using positive electrospray ionization mode with multiple reaction monitoring (MRM). The assay was linear in the concentration range of 0.1–100 ng mL−1 for all analytes. Intra- and inter-assay precision and accuracy were within ± 13.33% and ± 10.53%, respectively. This approach described herein was used to determine the intracellular accumulation of tenofovir, emtricitabine, dolutegravir simultaneously in hCMEC/D3 cells samples.

Keywords: Mass spectrometry, HIV, antiretroviral drugs, dolutegravir, tenofovir, emtricitabine

Graphical Abstract

1. Introduction

According to the Joint United Nations Program on HIV/AIDS (UNAIDS) report of 2018, 36.9 million people globally are living with Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV) [1]. In the early years of the HIV epidemic, post-diagnosis survival rates were measured in months. With the advent of combination antiretroviral therapy (cART), patients are better able to achieve and maintain plasma viral suppression, and survival rates of individuals living with HIV has reached a near normal life span [2]. However, even for patients who can achieve viral suppression within the blood, HIV persists within the central nervous system (CNS). The persistence of HIV and the resultant chronic inflammation likely contribute to the development of neurocognitive deficits experienced by many people infected with HIV [3–5]. Approximately, 50–60% of individuals infected with HIV suffer from HIV associated neurocognitive disorder (HAND), which is a spectrum of neurocognitive impairment ranging from asymptomatic neurocognitive impairment to full blown dementia [5–7].

Poor brain penetration of antiretroviral drugs likely contributes to the persistence of HIV within the brain [8]. Antiretroviral penetration into the brain is mediated, in part, by (1) the blood-brain barrier (BBB), which restricts the entry of the drugs into the central nervous system (CNS), and via (2) uptake and efflux transport proteins that are expressed at the luminal side of BBB [9]. Depending on the physicochemical properties of the drug or substrate, efflux transport proteins can either facilitate or impede xenobiotic entry into the brain [10]. Furthermore, the net flux of drugs into the cytoplasm of individual cell types within the CNS, is also mediated by transport proteins, which are integral membrane proteins expressed at the cell surface. Drug efflux proteins, such as P-glycoprotein and breast cancer resistance protein (BCRP) are transport systems that can actively extrude substrates, including several antiretroviral drugs, out of the cell on which they are expressed [11,12]; thereby limiting the overall intracellular concentrations of antiretroviral drugs [13]. In contrast, uptake transporters, when located on the luminal side of the BBB, facilitate the movement of substrates across the BBB and into individual cells [14].

Human brain microvascular endothelial cells, the primary cellular constituent of the BBB, form the lining of brain microvessels. Through the expression of tight junction proteins, these cells form a tight intercellular barrier that restricts the entry of toxins, and other foreign substances, including xenobiotics, across the BBB and into the brain [15]. Structural and functional deficits in brain microvascular endothelial cells are critical in advancing the neuropathogenesis of HIV [16]. These cells are the site of entry where free circulating virus, as well as HIV-infected monocytes, pass through the barrier and enter the brain [17,18]. Moreover, human brain microvascular endothelial cells may also be a site of HIV replication [19–21]. In this study, we developed and validated an assay for simultaneous quantification of three antiretroviral drugs and applied this method in the quantification of antiretroviral concentrations within an immortalized human brain microvascular endothelial cell line (hCMEC/D3). The hCMEC/D3 cell line has been widely used as a model of primary human brain microvascular endothelial cells and in the construction of an in vitro BBB model [22–25]. The hCMEC/D3 cells mimic key aspects of primary endothelial cells and display characteristics of the BBB, including the expression of tight junction proteins, the uptake and efflux transport proteins, the expression of chemokine receptors (including HIV-1 co-receptors), and they also can regulate the expression of cellular adhesion molecules in response to inflammatory cytokines [22].

Because HIV enters and replicates within infected cells, intracellular drug concentration is important factor in determining the efficacy of an antiretroviral drug. Several antiretroviral drug classes including the nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors (NRTIs), nucleotide reverse transcriptase inhibitors (NtRTIs), non-NRTIs (NNRTIs), integrase strand transfer inhibitors (INSTI), and protease inhibitors (PIs) act on intracellular targets. As discussed above, the intracellular accumulation of antiretroviral drugs is dependent on several factors, including drug transport protein expression and activity, which varies among different cell types [26–29]. There is also evidence of tissue-specific differences in the penetration of antiretroviral drugs within cerebral cortical, female genital tract tissue, and lymphoid compartments when compared to blood, which may affect the efficacy of antiretroviral therapy [30,31]. Accordingly, the goal of this study was to develop an assay to simultaneously measure the intracellular concentration of multiple antiretroviral drugs within a clinically relevant drug regimen.

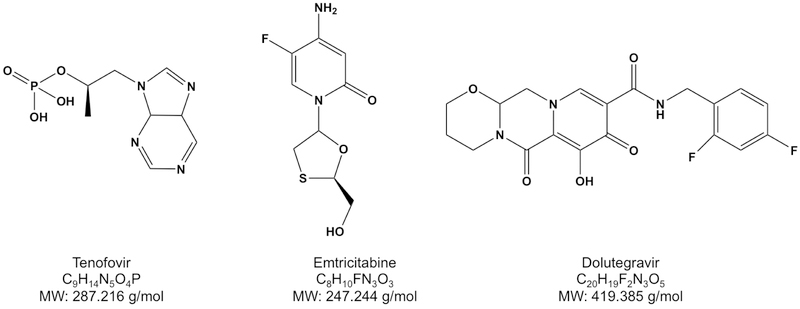

For this study, the cART regimen of a nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor (NRTI), emtricitabine, a nucleotide reverse transcriptase inhibitor (NtRTI), tenofovir, and an integrase strand inhibitor, dolutegravir, was used (Fig. 1). This regimen is currently one of the recommended initial regimens for most people with HIV [32]. These drugs have previously been quantified, individually or simultaneously, in either human plasma or peripheral blood mononuclear cells or mouse plasma [33–37].

Figure 1:

Chemical structures, chemical formula and molecular weights (MW) of antiretroviral drugs

There are few published reports that have quantified these drugs individually or in combination with other drugs. James et al. reported tenofovir and emtricitabine cellular uptake in non-monocytic female genital tract cells employing solid phase extraction (SPE) with a reverse phase OASIS HLB plate cartridge using an isocratic mobile phase of 0.01% trifluoroacetic acid and acetonitrile in a ratio of 90:10 v/v [28]. Tenofovir and its phosphorylated metabolites were individually estimated in hepatocytes infected with hepatitis B virus using protein precipitation by methanol and a gradient elution consisting of water with 5 mM ammonium acetate and acetonitrile-methanol, 50:50, v/v mobile phases [38]. Tsuchiya et al. simultaneously determined dolutegravir and other INSTI concentrations in human plasma and CSF using protein precipitation by acetonitrile with an isocratic mobile phase consisting of acetonitrile:water (70:30, v/v) with 0.1% formic acid [39]. To date, this particular three-drug combination has been quantified concurrently in mouse plasma and tissue by SPE using isocratic mobile phase consisting of 0.1% formic acid in water and 0.1% formic acid in acetonitrile mobile phases [36]. Calibration ranges for tenofovir, emtricitabine, and dolutegravir were 10–4000 ng mL−1, 5–2000 ng mL−1, and 5–2000 ng mL−1, respectively.

To best of our knowledge, this is the first study quantifying the intracellular concentrations of these three antiretroviral drugs simultaneously in human brain microvascular endothelial cells and the method developed is more sensitive than previously reported.

2. Experimental

2.1. Chemicals and reagents

Tenofovir and emtricitabine were obtained from United States Pharmacopeia (Rockville, MD). Dolutegravir was purchased from TLC PharmaChem (Ontario, Canada). For cellular accumulation studies following drugs were obtained through the NIH AIDS Reagent Program, Division of AIDS, NIAID, NIH: Tenofovir, Emtricitabine [(−) FTC]. Dolutegravir was purchased from Sigma Aldrich. Tenofovir-d6 and emtricitabine-13C 15N2 were obtained from Toronto Research Chemical Inc. (Ontario, Canada). Dolutegravir-d5 was purchased from BDG Synthesis (Wellington, NZ). Methanol, acetonitrile with 0.1% formic acid, and 2-propanol (HPLC grade) were obtained from Honeywell Chemicals (Muskegon, MI). Ultrapure water was collected from Milli-Q® (Molsheim, France) integral water purification system. 6-well plates used in these studies were from Corning Inc. (Corning, NY, USA). Human brain microvascular endothelial cells, hCMEC/D3, were generously provided by Dr. Babette Weksler of Weill Cornell Medical College, Cornell University (New York, NY). Endothelial basal media (EBM-2) and the EGM2-MV Bullet kit were purchased from Lonza (Basel, Switzerland). GIBCO® HBSS (Hank’s balanced salt solution), penicillin-streptomycin (10,000 U mL−1), HEPES [(4-(2-hydroxyethyl)-1-piperazineethanesulfonic acid)] was obtained from Thermo Fisher Scientific (Waltham, MA). The EGM2-MV Bullet kit contained human endothelial growth factor (hEGF), insulin-like growth factor (IGF), human fibroblast growth factor (hFGF), vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), hydrocortisone, ascorbic acid, FBS, GA-1000 (gentamycin and amphotericin). 0.45 µm MultiscreenHTS filter plate was purchased from Millipore (Millipore sigma, USA)

2.2. Cell culture

hCMEC/D3 were grown in EBM-2 media supplemented with EGM2-MV bullet kit (called growth medium) at 5% CO2, 37°C and 95% relative humidity. Cells seeded on 6 –well plate were grown on EBM-2 media supplemented with 1.25% FBS, 5 mL of penicillin/streptomycin solution (10,000 U mL−1), 5 mL of 10 mM HEPES and 1.25 mLs of 0.5 ng mL−1 bFGF. This media was called maintenance media.

2.3. Chromatography

The HPLC system consisted of an Agilent 1260 Series HPLC system (Agilent Technologies, Palo Alto, CA, USA), a Shimadzu, System Controller, SCL-10A Vp, Pump, LC 10AD Vp Solvent Degasser (DGU14A, Shimadzu, Columbia, MD, USA), and an CTC PAL autosampler (Zwingen, Switzerland). The analytical column was XBridge C18, 50 × 2.1 mm, 5µm (Waters Corp, Milford, MA, USA). The column temperature was maintained at 25 °C. Mobile phase A was water and mobile phase B was 0.1 % formic acid in acetonitrile. The elution pump (Agilent 1260) gradient was: 0–1.0 min 0.0% B at 0.4 mL min−1 flow, 1.1–3.0 min from 50% to 90% B at 0.4 mL min−1 flow rate, 3.1–7.0 min 90% B at 0.8 mL min−1 flow rate and 7.1–10.0 min 0.0% B at 0.8 mL min−1 flow rate. The makeup pump (Shimadzu) ran an isocratic gradient at 50:50 mobile phase A: mobile phase B and at flow rate of 0.2 mL min-1. The switching valve program was: 0–1.8 min at position A (loading sample into column and desalting), 1.8–3.0 min at position B (elution to MS source) and 3.0 to 10.0 min at position A (column flushing and re-equalibration). Injection volume was 50 µL and total run time was 10.0 min.

2.4. Mass spectrometric conditions

The mass spectrometer was an AB Sciex API 4000 system (Applied Biosystems Sciex, Ontario, Canada) using Analyst 1.6.3 software, which was operated in the electrospray ionization (ESI) positive multiple reaction monitoring (MRM) mode. The MS/MS parameters were: ion source temperature (500 °C), i on spray voltage (5000 V), electron multipllier CEM (2400 V), collision gas flow CAD (8.0), curtain gas flow CUR (25.0), nebulizer gas flow NEB/GS1 (45.0), turbo ion spray gas AUX/GS2 (45.0), deflector potential DF (−150), pause time 5 ms. A 100 ng/mL solution of each analyte or internal standard was prepared individually and constantly infused (10 µl/mL) into the MS along with mobile phases (0.4 ml/mL). Mass transition pre-collision cell voltages [declustering potential (DP), entrance potential (EP)] for precursor ions were optimized by gradually changing voltage range while monitoring the signal intensity of the compound of interest using the automated Edit Ramp function. The value which gives best signal intensity for an ion of interest is considered optimum. Similarly, collision energy (CE) and cell exit potential (CXP) were optimized to a value which gives the best signal for an ion of interest. Mass transitions and optimized MRM parameters are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Mass spectrometer parameters

| Drugs | Q1 | Q3 | DP(V) | CE(eV) | EP(V) | CXP(V) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tenofovir | 288.2 | 175.9 | 64.00 | 36.00 | 10 | 12.07 |

| Tenofovir-d6 | 294.3 | 182.2 | 64.00 | 37.11 | 10 | 10.07 |

| Emtricitabine | 248.1 | 130.0 | 36.74 | 15.00 | 10 | 8.98 |

| Emtricitabine-13C 15N2 | 251.3 | 133.0 | 36.75 | 15.07 | 10 | 8.98 |

| Dolutegravir | 420.1 | 277.0 | 81.97 | 37.95 | 10 | 20.59 |

| Dolutegravir-d5 | 425.3 | 277.2 | 83.00 | 36.70 | 10 | 19.78 |

Q1 =Quadrupole mass filter 1 (Q1) and 3 (Q3), DP= Declustering potential

CE= Collision Energy, EP= Entrance Potential CXP= Collision Cell Exit Potential

2.5. Cell extract preparation

hCMEC/D3 cells were grown in T75 flasks as described above. At 90% confluency, cells were washed twice with 9.5 mL of ice-cold HBSS and cells were lysed with a 15 min ice-cold methanol (9.5 mL) incubation followed by scraping of the cells. The resulting cell extracts were stored at −80°C.

2.6. Stock solution preparation

Stock solutions of tenofovir, tenofovir-d6, emtricitabine, emtricitabine-13C6, 15N2 were prepared in ultrapure water at a concentration of 100 µg mL-1. Dolutegravir, dolutegravir-d5 stock solutions were prepared in DMSO at a concentration of 100 µg/mL. Subsequent dilutions were made in water for spiking calibration standards and quality control samples. All stock solutions were stored at 2–8°C in amber colored glass bottles.

2.7. Preparation of calibration standards and quality control (QC) samples

Calibration standards and quality control samples were prepared in pooled methanol lysates of hCMEC/D3 cells. Calibration standards at concentration levels of 0.100, 0.500, 1.000, 1.500, 2.500, 6.000, 15.000, 40.000, 80.000, 100.000 ng mL−1 were prepared by spiking appropriate amount of stock solutions into the blank cell lysate matrix. Similarly, quality control (QC) samples were prepared at six levels, the lower limit of quantification (LLOQ; 0.100 ng mL−1), low level (Low-QC; 0.300 ng mL−1), medium low level (MedLow-QC; 1.000 ng mL−1), medium level (Med-QC; 2.000 ng mL−1) medium high (MedHigh-QC; 50.000 ng mL−1), and high level (High-QC; 75.000 ng mL−1) quality controls for determining intraday accuracy and precision. While five levels of QC, except LLOQ (0.100 ng mL−1), were prepared for determining inter day accuracy and precision. Dilution QC samples were prepared at a nominal concentration of 200 ng mL−1 to validate the dilution integrity of above the upper limit of quantitation (ULOQ) samples. Standards and QC were subaliquoted into 2.0 mL low bind polypropylene tubes (Eppendorf, Hauppage, NY) and stored at −80°C.

2.8. Sample Preparation

Sample plates were vortex mixed for 1.0 min at 750 rpm then centrifuged for 5 min at 4700 × g. Two hundred microliters of each sample was aliquoted into a 96-well plate, and 20 µL of 50 ng mL−1 working internal standard solution was added. Sample plates were vortex mixed for 5 min at 750 rpm and centrifuged for 15 min at 6100 × g. 150 µL of supernatant was collected, filtered through a 0.45 µm multiscreen HTS filter plate (centrifuged for 5 min at 4300 × g) and dried under a steady stream of nitrogen gas at 45°C. The dried extracts were reconstituted with 15 0 µL of ultrapure water, mixed for 10 min at 1200 rpm. and centrifuged again for 15 minute at 6100 × g. Lastly, 50 µL of the final extract was injected into the LC-MS/MS.

2.9. Method Validation

The developed LC-MS/MS method was validated for linearity, precision and accuracy. Acceptance criteria was ± 20% for LLOQ and ±15% for all other levels according to the FDA bioanalytical guidance for these parameters [40].

2.9.1. Linearity and lower limit of quantification (LLOQ)

Cell lysate calibration curves were constructed by plotting peak area ratio of each analyte to its corresponding labeled internal standard versus standard concentrations. Ten calibration standards in duplicates over five validation runs were constructed using a linear 1/concentration squared weighted least-squares regression algorithm. The lower limit of quantitation (LLOQ) was defined as the lowest concentration on the calibration curve with precision (calculated as percent relative standard deviation; % RSD) and accuracy (calculated as percent difference from nominal; % DFN) within ± 20%. The limit of detection (LOD) was defined as the lowest concentration that can be detected at a signal-to-noise ratio of 3:1.

2.9.2. Selectivity

Six blank cell lysates from hCMEC/D3 cells at six different passages were processed in the same fashion as samples (see sample preparation 2.8). The selectivity of this assay was assessed by comparing LLOQ level and blank cell extracts. To assess for possible interference from blank cell matrix, no peaks in blank cell extracts should be greater than 20% response of LLOQ.

2.9.3. Accuracy and Precision

Accuracy and precision were evaluated using six QC levels (LLOQ, Low-QC, MedLow QC, Med-QC, MedHigh-QC, and High-QC). Intra-day accuracy and precision were determined by analyzing six replicates at each QC level in a single assay. Inter-day accuracy and precision were determined by analyzing all QC level except LLOQ in five independent runs. To validate the dilution integrity of above the ULOQ samples; dilution QC samples (200 ng mL−1) were diluted threefold and analyzed in six replicates in one validation run. Accuracy and precision within ± 20% for LLOQ and ± 15% for other samples of their nominal concentration was considered acceptable.

2.9.4. Recovery

Extraction recovery of target analytes from cell lysate at low, mid and high levels was assessed by comparing extracted analyte responses (pre-extracted, spiked samples) to analyte responses spiked into extracted blank cell lysate samples (post-spiked samples), which was considered 100% recovery.

2.9.5. Post-Extraction Addition experiment (Matrix Effect Evaluation)

Matrix effect was evaluated by comparing analyte responses spiked into extracted blank cell lysate samples (post-spiked samples) to analyte responses in an external solvent (water).

2.9.6. Stability Studies

Post-preparative extract stability was evaluated at low and high QC levels. QC samples were processed with a calibration curve and stored in the autosampler at 4°C for seven days, then re-analyzed and processed against fresh extracted calibration curve, Analyte stability in frozen matrix was determined by analyzing three replicates of low QC and high QC samples that had been stored at −80°C for 1 20 days. For all stability experiments; precision and accuracy should be within ± 15%.

2.10. Application of the validated method

The hCMEC/D3, cells were grown on 6-well plates. At 90% confluency, the cells were washed thrice with 1.0 mL HBSS. The cells were treated with individual drug solutions of tenofovir, emtricitabine, or dolutegravir. Each drug was prepared in a 100 mM stock solution in water except dolutegravir, which was diluted in DMSO. All subsequent dilutions were made in water, and the final concentration of DMSO for all drugs was less than 0.1%. The final treatment concentrations for each drug were 1436 ng mL−1, 1236 ng mL−1, 2097 ng mL−1 (all corresponding to 5 µM) and 2871 ng mL−1, 2473 ng mL−1, 4194 ng mL−1 (corresponding to 10 µM), respectively. Additionally, cells were also treated with two different combinations of tenofovir, emtricitabine, and dolutegravir in HBSS buffer. In the first combination antiretroviral solution, all antiretrovirals were at a final concentration of 5 µM, and in the second combination, all antiretrovirals were at a final concentration of 10 µM. The concentrations used in these studies were based on the maximum serum concentration (Cmax) of drug obtained from clinical studies [41–43]. Each treatment group was incubated for one hour before harvest and sample preparation. Upon harvest, the antiretroviral-containing incubation solutions were removed from each well and cells were quickly washed three times with 1.0 mL of ice-cold HBSS. Cells were lysed by adding 1.0 mL of methanol to the cells, which was allowed to sit on ice for 15 min. Cell extract was collected by scraping the cells with a cell scraper. Two hundred microliters of the extract was collected in a 96-well plate, and post-processing of the extract was similar as mentioned above in sample preparation. The cell lysate was used to calculate protein concentration by Pierce™ BCA protein assay Kit. Intracellular drug accumulation was expressed as the amount of drug accumulated per µg of total protein per hour. Incurred sample reanalysis (ISR) was conducted to verify the reliability of the reported results.

2.9. Software

Analyst® was used to process data collected from mass-spectrometer. Cellular accumulation data were represented as mean ± SEM. Intracellular accumulation of antiretroviral drugs was compared by two-way ANOVA using Tukey’s post hoc test. Statistical analysis was performed using GraphPad Prism (V7) (San Diego, California).

3. Results

3.1. Linearity

Linearity was obtained over a concentration range of 0.100–100 ng mL−1 for all analytes. The average correlation coefficient (r2) from five validation runs weighted by 1/x2 was found to be 0.997 (0.330 %RSD), 0.993 (0.145 %RSD), 0.998 (0.046 %RSD) for tenofovir, emtricitabine, and dolutegravir, respectively. The precision (%RSD) of back-calculated standards was within 7.14%, 5.83 %, and 13.23% for tenofovir, emtricitabine and dolutegravir, respectively and the accuracy (%DFN) were within ± 2.44%, ± 11.14%, ± 2.80% for tenofovir, emtricitabine and dolutegravir, respectively. The limits of detection (LOD) for tenofovir, emtricitabine, and dolutegravir were found to be 0.024 ng mL−1, 0.011 ng mL−1, and 0.04 ng mL−1, respectively.

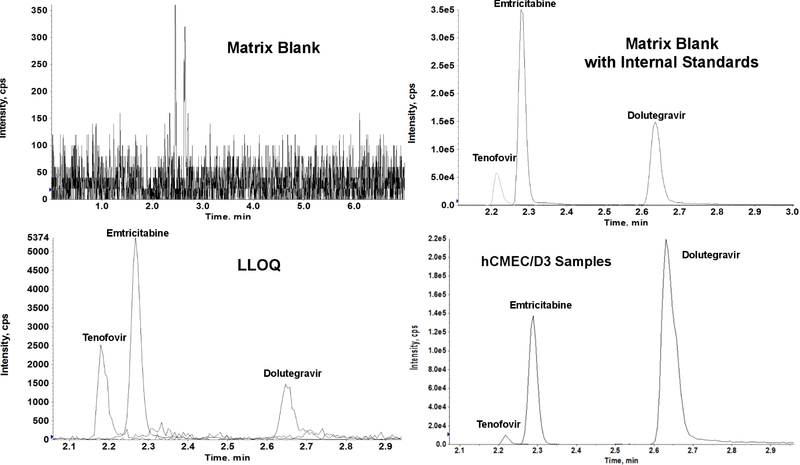

3.2. Selectivity

Six separate isolations of blank cell lysates collected from passages 26–32 of hCMEC/D3 cells were extracted according to the sample preparation procedure for any potential interferences at the mass transitions and expected retention times of target analytes. No significant chromatographic peak greater than 20% of the mean LLOQ response was detected for all analytes.

3.3. Accuracy and precision

Inter-day precision and accuracy were found to be within ± 10.53% (Table 2). Intra-day precision and accuracy were within ± 13.33% (Table 3) for all analytes.

Table 2.

Inter-day precision and accuracy (n= 21)

| Analyte | Concentration | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0.3 ng mL−1 |

1.0 ng mL−1 |

2.0 ng mL−1 |

50.0 ng mL−1 |

75.0 ng mL−1 |

||

| Tenofovir | %RSD | 6.20 | 6.32 | 5.00 | 8.74 | 5.77 |

| %DFN | 1.22 | 0.07 | 1.33 | 4.61 | 1.02 | |

| Emtricitabine | %RSD | 6.07 | 3.55 | 3.03 | 3.35 | 6.04 |

| %DFN | 7.73 | 3.99 | 5.20 | −2.72 | −8.14 | |

| Dolutegravir | %RSD | 10.53 | 6.64 | 7.21 | 7.49 | 5.24 |

| %DFN | −0.18 | −1.94 | 0.17 | 5.52 | 3.43 | |

%RSD = Percent Relative Standard Deviation, %DFN = Percent Difference from Nominal concentration

Table 3.

Intra-day precision and accuracy (n=6)

| Analyte | Concentration | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0.1 ng mL−1 |

0.3 ng mL−1 |

1.0 ng mL−1 |

2.0 ng mL−1 |

50.0 ng mL−1 |

75.0 ng mL−1 |

||

| Tenofovir | %RSD | 13.13 | 5.53 | 5.65 | 5.70 | 2.45 | 4.02 |

| %DFN | 5.00 | 3.89 | −6.80 | 2.17 | 4.30 | 1.46 | |

| Emtricitabine | %RSD | 4.56 | 5.75 | 2.32 | 1.87 | 2.41 | 3.77 |

| %DFN | 13.33 | 10.00 | 3.60 | 2.75 | −1.80 | −10.57 | |

| Dolutegravir | %RSD | 9.08 | 7.89 | 2.98 | 1.96 | 1.72 | 5.73 |

| %DFN | 8.33 | 0.00 | −8.00 | −4.50 | 1.67 | −4.07 | |

%RSD = Percent Relative Standard Deviation, %DFN = Percent Difference from Nominal concentration

3.4. Dilution integrity

The intra-assay precision and accuracy were within 9.00% and ± 3.90%, respectively, for diluted QC samples for all analytes.

3.5. Extraction recovery

Extraction recoveries of all analytes from cell lysates were calculated by comparing pre-extraction spiked samples and post-extraction spiked samples at 2.0 ngmL−1, 50 ng mL−1 and 75 ng mL−1 (n = 3). Extraction recoveries for tenofovir, emtricitabine, and dolutegravir (using analyte to IS area ratio) were found to be consistent across different concentration levels; 84.89 (1.18 %RSD), 86.76 (2.50 %RSD), and 87.33 (3.86 %RSD), respectively. Absolute extraction recoveries (using absolute area responses) for tenofovir, emtricitabine and dolutegravir were found to be 86.04 (2.74 % RSD), 85.46 (5.96 %RSD), and 94.04 (7.39 %RSD), respectively.

3.4. Matrix effects

A post-extraction addition experiment was conducted to evaluate matrix effects at 2.0, 50 and 75 ng mL-1; by comparing post-extraction spiked matrix samples to matrix free-samples prepared at the same concentrations. The results showed that matrix effects (using analyte to IS area ratio) were within 88.82 (4.88 %RSD), 100.16 (3.09 %RSD), and 104.64 (2.52 %RSD) for tenofovir, emtricitabine, and dolutegravir, respectively. Absolute matrix effects (using absolute area responses) of tenofovir and emtricitabine were found to be 94.87 (14.49 %RSD) and 90.75 (7.98 %RSD), respectively. These results demonstrate the absence of matrix effects and also show that use of labeled internal standard improved the %RSD values. For dolutegravir; the absolute matrix effects (using absolute area responses) was found to be 149.64 (26.70 %RSD); lower responses and variabilities were observed for both analyte and IS in external solution only, which likely is due to non-specific binding in the absence of extracted matrix components. Labeled internal standard compensated for any variabilities or potential matrix effects as demonstrated by the above results.

3.6. Stability studies

All stability studies showed results within ± 15%. Post-preparative extract stability was found to be stable for seven days at 2–8 °C, and lo ng-term matrix stability was demonstrated for 120 days at −80 °C.

3.7. Application of the method

Tenofovir, emtricitabine, and dolutegravir were incubated individually and together as a cocktail at both 5 µM and 10 µM for one hour at 37°C to allow time for drug uptake into the cells. Following the one hour incubation, the intracellular concentration of each drug within the cells was measured using the aforementioned LC-MS/MS method. The amount of drug accumulated with the cells was normalized to the protein content of each well. We were able to quantify tenofovir, emtricitabine and dolutegravir in the lysate of hCMEC/D3 cells treated antiretroviral drugs treated individually and within a commonly used clinical cART cocktail (Figure 2D). Individual drug and cocktail concentrations were used at both 5 µM and 10 µM (Table 4). Intracellular concentrations of tenofovir, emtricitabine, and dolutegravir were determined in hCMEC/D3 cells using this method. The rank order of intracellular accumulation of antiretroviral drugs was found to be dolutegravir > emtricitabine > tenofovir. Intracellular accumulation of dolutegravir was significantly higher than tenofovir or emtricitabine either individually or in combination.

Figure 2:

LC-MS/MS chromatograms of (A) Blank cell lysate matrix, (B) Blank cell lysate matrix spiked with labeled internal standards (tenofovir-d6, emtricitabine-13C6, 15N2 and dolutegravir-d5), (C) 0.1 ng mL-1 (LLOQ) of tenofovir, emtricitabine and dolutegravir, and (D) intracellular accumulation with hCMEC/D3 samples.

Table 4.

Intracellular accumulation of antiretroviral drugs

| Concentration → |

5 µM |

10 µM |

5 µM |

10 µM |

5 µM |

10 µM |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Drugs ↓ |

Picomoles/mg of protein |

Picomoles/mg of protein |

Drug Conc. (ng mL−1) |

Drug Conc. (ng mL−1) |

Protein Conc. (mg mL−1) |

Protein Conc. (mg mL−1) |

| Individual Drugs | ||||||

| Tenofovir | 5.91 ± 1.74 | 5.32 ± 1.07 | 0.32 ± 0.08 | 0.64 ± 0.17 | 0.22 ± 0.08 | 0.42 ± 0.07 |

| Emtricitabine | 19.74 ± 3.13 | 16.95 ± 4.66 | 1.18 ± 0.10 | 2.44 ± 0.44 | 0.26 ± 0.05 | 0.47 ± 0.08 |

| Dolutegravir | *,#74.84 ± 9.84 | *,#250.49 ± 45.45 | 14.19 ± 0.62 | 48.57 ± 5.04 | 0.46 ± 0.05 | 0.48 ± 0.06 |

| Drugs in combination | ||||||

| Tenofovir | 2.63 ± 0.86 | 5.15 ± 1.11 | 0.32 ± 0.07 | 0.64 ± 0.15 | 0.46 ± 0.06 | 0.43 ± 0.06 |

| Emtricitabine | 9.29 ± 1.89 | 23.36 ± 4.56 | 1.01 ± 0.11 | 2.40 ± 0.21 | 0.46 ± 0.06 | 0.43 ± 0.06 |

| Dolutegravir | *,#81.09 ± 18.51 | *,#266.90 ± 40.99 | 14.67 ± 1.41 | 46.63 ± 2.71 | 0.46 ± 0.06 | 0.43 ± 0.06 |

Intracellular accumulation of each antiretroviral drug in the brain endothelial cell line, hCMEC/D3 cells. hCMEC/D3 cells were incubated with 5 or 10µM of dolutegravir, emtricitabine, or tenofovir or the cocktail of 5 or 10 µM of each drug given as a 3-drug combination (cART). Drug concentrations in ng mL−1 (columns 3, 4) were converted to picomoles mL−1 by respective molecular weight (Fig 1.) of each drug. Then, drug concentrations in picomoles mL−1 from column 3 and 4 were normalized by protein concentration mg mL−1 (columns 5, 6) to determine picomoles mg−1 of protein (columns 1, 2). Data are expressed as the mean ± SEM (for drug accumulation in picomoles/mg of protein, and ng mL−1, protein concentration in mg mL−1) for n = 3 independent experiments. Intracellular accumulation of dolutegravir was significantly higher than tenofovir

(p<0.05) and emtricitabine

(p<0.05), both individually and in combination.

4. Discussion

Although several methods have been developed to determine antiretroviral drugs individually or simultaneously in human plasma or peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs), to our knowledge this is the first reported method to simultaneously determine the regimen tenofovir, emtricitabine, and dolutegravir within brain cells. Prathipati et al. determined this regimen along with elvitegravir and rilpivirine in mouse plasma, however, they also did not analyze this regimen in PBMCs or other cellular matrices [36]. cART regimens pose an analytical challenge of determining all the drugs simultaneously due to the differences in the physiochemical properties of the drugs. In the aforementioned regimen, NRTIs (tenofovir, emtricitabine) are hydrophilic, while dolutegravir is lipophilic [10].

A simple extraction procedure involving protein precipitation using 100% methanol was applied. Raw cell extract was centrifuged, the cell pellet utilized for protein assay, and the supernatant was processed further for LC-MS/MS analysis (Refer to 2.8). Several analytical columns were used to optimize the separation of target analytes including: X bridge® (C18, 50 X 2.1mm, 5 µM), Phenomenax® (C18,50 X 2.1mm., 5 µM), Atlantis® (C18, 50 X 2.1mm., 5 µM), Acquity (UPLC® BEH C18 50 × 2.1 mm, 1.7 µm). These columns were compared regarding peak shape and resolution. X-bridge® (C18, 50 X 2.1mm, 5 µM) demonstrated excellent peak shape and chromatographic resolution for all analytes (Figure 2). Sub-2 µm UPLC columns are known to provide better separation. However, high back-pressure is the main disadvantage of this column, and no superior benefits were observed with the UPLC column compared to the 5 µm C18 column. Several solvent system combinations including water, methanol, and acetonitrile with 0.1% formic acid were attempted. The best peak shape for all analytes was observed with a slow gradient using water (as mobile phase A) and 0.1% formic acid in acetonitrile (as mobile phase B). Room temperature and elevated column temperatures were also tested, and room temperature was found to be convenient for this separation. Several autosampler rinse solutions were evaluated to eliminate any assay-related carryover (especially for dolutegravir). Different combinations of methanol, ethanol, and isopropanol with water and formic acid were evaluated. The autosampler rinse solution that best eliminated carryover consisted of 90:10:0.5 (v/v/v) of ethanol/water/formic acid was chosen for the final method. An online-cleanup approach has been applied; a desalting step (directed to waste) was used to remove all salts, and a washing step which used a high percentage of organic mobile phase was applied after analyte elution to ensure removal of endogenous matrix components after each injection.

A method for determining tenofovir and tenofovir alafenamide concentrations in human plasma and cerebrospinal fluid was previosuly published [44]. This method used solid phase extraction (SPE) with a gradient elution of 0.1% formic acid in water and acetonitrile on Phenomenex Synergi™ 4 µM Polar-RP 80 Å (50 × 2.0 mm) column. The linear range for tenofovir was 0.5–500 ng mL−1 in plasma and 0.1–50 ng mL−1 in CSF, which compares to our range of 0.1–100 ng mL−1 in cell extract. However, in contrast to our method, there was significant ion suppression (42.3–55.4%) and low absolute extraction recovery (21.7–29.4%) for tenofovir [44]. C18 SPE cartridges have been used for extraction of tenofovir, emtricitabine, rilpivirine, elvitegravir and dolutegravir from mouse biological matrices. No significant ion suppression or enhancement were observed for the studied analytes using normalized internal standard results; however, low extraction recoveries (22.1–63.1%) were reported [36]. An LC-MS/MS method for simultaneous determination of dolutegravir, raltegravir, and elvitegravir levels has been reported [39] using protein precipitation by acetonitrile in human plasma and CSF. The method was developed on Xbridge C18 Column ( 50 × 2.0 mm, 3.5 µm) using isocratic mobile phase of acetonitrile:water (70:30) containing 0.1% formic acid. However, the authors did not report their extraction recovery and matrix effects, and the assay was validated within a calibration range of only 5–1500, and 1–200 ng mL−1 for plasma and CSF, respectively [39]. The developed protein precipitation approach with online clean-up showed excellent extraction recoveries and the absence of matrix effects in addition to a high degree sensitivity and selectivity.

Our newly developed method was applied to measure intracellular concentrations of tenofovir, emtricitabine, and dolutegravir in a human brain endothelial cell line (hCMEC/D3). Incurred sample reanalysis (ISR) also showed that more than 75% of the repeated results were within 20% of both the mean and the original values. We were able to quantify the concentrations of tenofovir, emtricitabine, and dolutegravir in the hCMEC/D3 cells. The rank order for the accumulation of each drug inside the hCMEC/D3 cells was dolutegravir > emtricitabine > tenofovir. This pattern can be explained by physicochemical properties of each drug. Poor accumulation of tenofovir is explained by the fact that it exists in diionic form at physiological pH, which is responsible for its poor bioavailability, and limited activity against HIV-1 in a cell-based assay [45]. Emtricitabine is a polar moiety with a LogP value of −1.40, making it less permeable inside the cells [10]. Dolutegravir is sufficiently lipophilic with LogP value of 1.10, thus potentially providing a rationale for why it had the highest accumulation among these drugs [10]. Furthermore, drug accumulation inside cells can be influenced significantly by uptake and efflux transporters. The two uptake transporters that are known to mediate tenofovir entry into cells; the organic anion transport proteins 1 and 3 (OAT1; SLC22A6 and OAT3; SLC22A8, respectively). Although OAT3 is known to be expressed at the human BBB, neither OAT1 or OAT3 are expressed by the hCMEC/D3 cells [46,47]. This could be an explanation for the low intracellular concentrations of tenofovir within these cells. Tenofovir is also a substrate of the efflux transporter multidrug resistant protein-4 (MRP-4; ABCC4), which could further limit intracellular tenofovir concentrations by extruding the drug from the cell [46]. hCMEC/D3 cells are reported to have a similar expression level of MRP-4 as that in isolated human brain microvessels [48]; therefore, MRP-4 may be further limiting the overall accumulation of tenofovir within hCMEC/D3 cells. Emtricitabine is a substrate of the uptake transporter, multidrug and toxin extrusion protein-1 (MATE1: SLC47A1), and the efflux transporter, multidrug resistant protein −1 (MRP-1; ABCC1). The MRP-1 transporter may be affecting the accumulation of emtricitabine in hCMEC/D3 cells by extruding the drug out of the cells. MATE1 transporters have been reported in brain microvessels from human cortical samples [49]; however, they are not reportedly expressed in hCMEC/D3 cells [48]. Dolutegravir is the substrate of P-glycoprotein (P-gp; ABCB1) and BCRP (ABCG2). Both of these transporters are expressed and functional in hCMEC/D3 cells and limit dolutegravir intracellular accumulation [50]. However, experimental manipulation of the potential interactions between drugs and uptake/efflux transporters was beyond of the scope of this study. Finally, this method was successfully applied to estimate intracellular concentrations of tenofovir, emtricitabine and dolutegravir in endothelial cells (hCMEC/D3).

Besides endothelial cells, HIV-1 infects perivascular macrophages, microglia, astrocytes, and pericytes in the CNS. Although the intracellular concentrations of antiretroviral drugs within these cell types are scantly reported in the literature, it may be important to ascertain the relationship between intracellular drug concentrations and anti-HIV-1 activity in each CNS cell type and under different pathophysiological conditions (which may affect efflux transporter expression or function). This is especially important in light of current strategies to find a cure and fully eradicate latent HIV reservoirs in the brain and elsewhere. Thus, future studies are warranted to assess intracellular antiretroviral concentrations in human neural cells.

5. Conclusion

In this study, we developed a bioanalytical assay with high sensitivity and specificity to simultaneously measure tenofovir, emtricitabine, and dolutegravir in cell extracts of hCMEC/D3 cells. The method was successfully validated for linearity, precision and accuracy and applied to determine uptake of tenofovir, emtricitabine, and dolutegravir inside hCMEC/D3 cells.

Highlights.

A simple and ultra-sensitive method for simultaneous determination of intracellular concentrations of tenofovir, emtricitabine and dolutegravir in human cerebral microvascular endothelial cells (hCMEC/D3) was developed and validated according to FDA guidance.

Method was successfully applied to determine intracellular concentration of tenofovir, emtricitabine and dolutegravir in hCMEC/D3 cells

Intracellular accumulation of antiretroviral drugs in picomoles/µg of protein was found to be dolutegravir > emtricitabine > tenofovir

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by funds from NIH: R21 DA045630 (MPM).

Abbreviations

- AIDS

Acquired Immunodeficiency Syndrome

- BBB

Blood Brain barrier

- BCA

Bicinchoninic Acid Assay

- BCRP

Breast Cancer Resistant Protein

- CNS

Central Nervous System

- cART

Combination Antiretroviral Therapy

- DFN

Difference from nominal

- ESI

Electron Spray Ionization

- HAND

HIV Associated Neurocognitive Disorders

- HBSS

Hank’s Balanced Salt Solution

- hCMEC/D3

human Cerebral Microvascular Endothelial Cells

- HIV

Human Immunodeficiency Virus

- INSTI

Integrase Strand Transfer Inhibitors

- LC-MS/MS

Liquid Chromatography Tandem Mass Spectrometry

- LLOQ

Lower Limit of Quantification

- MATE

Multidrug and Toxins Extrusion protein

- MRM

Multi-reaction Monitoring

- MRP

Multidrug Resistant Protein

- NNRTI

Non-nucleoside Reverse Transcriptase Inhibitors

- NRTI

Nucleoside Reverse Transcriptase Inhibitors

- NtRTI

Nucleotide Reverse Transcriptase Inhibitors

- OAT

Organic Anion Transporter

- PBMC

Peripheral Blood Mononuclear Cells

- PI

Protease Inhibitors

- QC

Quality Control

- RSD

Relative Standard Deviation

- ULOQ

Upper Limit of Quantification

- UNAIDS

United Nation Program on HIV/AIDS

- UPLC

Ultra Pressure Liquid Chromatography

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Declaration of interests

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

References

- [1].Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS, UNAIDS Data 2018, Geneva, Switzerland, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- [2].Antiretroviral Therapy Cohort Collaboration, Survival of HIV-positive patients starting antiretroviral therapy between 1996 and 2013: a collaborative analysis of cohort studies., Lancet. HIV 4 (2017) e349–e356. doi: 10.1016/S2352-3018(17)30066-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Dahl V, Peterson J, Fuchs D, Gisslen M, Palmer S, Price RW, Low levels of HIV-1 RNA detected in the cerebrospinal fluid after up to 10 years of suppressive therapy are associated with local immune activation., AIDS 28 (2014) 2251–8. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0000000000000400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Edén A, Fuchs D, Hagberg L, Nilsson S, Spudich S, Svennerholm B, Price RW, Gisslén M, HIV-1 viral escape in cerebrospinal fluid of subjects on suppressive antiretroviral treatment., J. Infect. Dis 202 (2010) 1819–25. doi: 10.1086/657342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Heaton RK, Clifford DB, Franklin DR, Woods SP, Ake C, Vaida F, Ellis RJ, Letendre S, Marcotte TD, Atkinson JH, Rivera-Mindt M, Vigil OR, Taylor MJ, Collier AC, Marra CM, Gelman BB, McArthur JC, Morgello S, Simpson DM, McCutchan JA, Abramson I, Gamst A, Fennema-Notestine C, Jernigan TL, Wong J, Grant I, F. the C. Group, HIV-associated neurocognitive disorders persist in the era of potent antiretroviral therapy: CHARTER Study, Neurology 75 (2010) 2087–2096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Williams R, Yao H, Dhillon NK, Buch SJ, HIV-1 Tat co-operates with IFN-gamma and TNF-alpha to increase CXCL10 in human astrocytes., PLoS One 4 (2009) e5709. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0005709. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Power C, Hui E, Vivithanaporn P, Acharjee S, Polyak M, Delineating HIV-associated neurocognitive disorders using transgenic models: The neuropathogenic actions of Vpr, J. Neuroimmune Pharmacol 7 (2012) 319–331. doi: 10.1007/s11481-011-9310-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Eisele E, Siliciano RF, Redefining the Viral Reservoirs that Prevent HIV-1 Eradication, Immunity 37 (2012) 377–388. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2012.08.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Eisfeld C, Reichelt D, Evers S, Husstedt I, CSF Penetration by Antiretroviral Drugs, CNS Drugs 27 (2012) 31–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Calcagno A, Di Perri G, Bonora S, Pharmacokinetics and Pharmacodynamics of Antiretrovirals in the Central Nervous System, Clin. Pharmacokinet 53 (2014) 891–906. doi: 10.1007/s40262-014-0171-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Ronaldson PT, Persidsky Y, Bendayan R, Regulation of ABC membrane transporters in glial cells: Relevance to the pharmacotherapy of brain HIV-1 infection, Glia 56 (2008) 1711–1735. doi: 10.1002/glia.20725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Löscher W, Potschka H, Drug resistance in br ain diseases and the role of drug efflux transporters., Nat. Rev. Neurosci 6 (2005) 591–602. doi: 10.1038/nrn1728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Decloedt EH, Rosenkranz B, Maartens G, Joska J, Central Nervous System Penetration of Antiretroviral Drugs: Pharmacokinetic, Pharmacodynamic and Pharmacogenomic Considerations, Clin. Pharmacokinet 54 (2015) 581–598. doi: 10.1007/s40262-015-0257-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Sanchez-Covarrubias L, Slosky LM, Thompson BJ, Davis TP, Ronaldson PT, Transporters at CNS barrier sites: obstacles or opportunities for drug delivery?, Curr. Pharm. Des 20 (2014) 1422–1449. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Abbott NJ, Patabendige AAK, Dolman DEM, Yusof SR, Begley DJ, Structure and function of the blood-brain barrier., Neurobiol. Dis 37 (2010) 13–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Zhang YL, Ouyang YB, Liu LG, Chen DX, Blood-brain barrier and neuro-AIDS, Eur. Rev. Med. Pharmacol. Sci 19 (2015) 4927–4939. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Miller F, Afonso PV, Gessain A, Ceccaldi P-E, Blood-brain barrier and retroviral infections., Virulence 3 (n.d) 222–9. doi: 10.4161/viru.19697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Banks W.a, Freed EO, Wolf KM, Robinson M, Franko M, Kumar VB, Robinson SM, Transport of Human Immunodeficiency Virus Type 1 Pseudoviruses across the Blood-Brain Barrier : Role of Envelope Proteins and Adsorptive Endocytosis Transport of Human Immunodeficiency Virus Type 1 Pseudoviruses across the Blood-Brain Barrier : Role of En, J. Virol 75 (2001) 4681–4691. doi: 10.1128/JVI.75.10.4681. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Conaldi PG, Serra C, Dolei A, Basolo F, Falcone V, Mariani G, Speziale P, Toniolo A, Productive HIV-1 infection of human vascular endothelial cells requires cell proliferation and is stimulated by combined treatment with interleukin-1 beta plus tumor necrosis factor-alpha., J. Med. Virol 47 (1995) 355–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Bussolino F, Mitola S, Serini G, Barillari G, Ensoli B, Interactions between endothelial cells and HIV-1., Int. J. Biochem. Cell Biol 33 (2001) 371–90. doi: 10.1016/S1357-2725(01)00024-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Nakagawa S, Castro V, Toborek M, Infection of human pericytes by HIV-1 disrupts the integrity of the blood-brain barrier, J. Cell. Mol. Med 16 (2012) 2950–2957. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Weksler BB, Subileau EA, Perrière N, Charneau P, Holloway K, Leveque M, Tricoire-Leignel H, Nicotra A, Bourdoulous S, Turowski P, Male DK, Roux F, Greenwood J, Romero IA, Couraud PO, Blood-brain barrier-specific properties of a human adult brain endothelial cell line., FASEB J 19 (2005) 1872–4. doi: 10.1096/fj.04-3458fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Patel S, Leibrand CR, Palasuberniam P, Couraud P-O, Weksler B, Jahr FM, McClay JL, Hauser KF, McRae M, Effects of HIV-1 Tat and Methamphetamine on Blood-Brain Barrier Integrity and Function In Vitro, Antimicrob. Agents Chemother (2017) in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- [24].Poller B, Gutmann H, Krähenbühl S, Weksler B, Romero I, Couraud P-O, Tuffin G, Drewe J, Huwyler J, The human brain endothelial cell line hCMEC/D3 as a human blood-brain barrier model for drug transport studies, J. Neurochem 107 (2008) 1358–1368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Tai LM, Holloway KA, Male DK, Loughlin AJ, Romero IA, Amyloid-β-induced occludin down-regulation and increased permeability in human brain endothelial cells is mediated by MAPK activation, J. Cell. Mol. Med 14 (2010) 1101–1112. doi: 10.1111/j.1582-4934.2009.00717.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Durand-Gasselin L, Da Silva D, Benech H, Pruvost A, Grassi J, Evidence and possible consequences of the phosphorylation of nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors in human red blood cells., Antimicrob. Agents Chemother 51 (2007) 2105–11. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00831-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Anderson PL, Zheng JH, King T, Bushman LR, Predhomme J, Meditz A, Gerber J, Fletcher CV, Concentrations of zidovudine- and lamivudine-triphosphate according to cell type in HIV-seronegative adults, Aids 21 (2007) 1849–1854. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e3282741feb. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].James AM, King JR, Ofotokun I, Sheth AN, Acosta EP, Uptake of tenofovir and emtricitabine into non-monocytic female genital tract cells with and without hormonal contraceptives., J. Exp. Pharmacol 5 (2013) 55–64. doi: 10.2147/JEP.S45308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Gray LR, Tachedjian G, Ellett AM, Roche MJ, Cheng W-J, Guillemin GJ, Brew BJ, Turville SG, Wesselingh SL, Gorry PR, Churchill MJ, The NRTIs Lamivudine, Stavudine and Zidovudine Have Reduced HIV-1 Inhibitory Activity in Astrocytes, PLoS One 8 (2013) e62196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Asahchop EL, Meziane O, Mamik MK, Chan WF, Branton WG, Resch L, Gill MJ, Haddad E, Guimond JV, Wainberg MA, Baker GB, Cohen EA, Power C, Reduced antiretroviral drug efficacy and concentration in HIV-infected microglia contributes to viral persistence in brain., Retrovirology 14 (2017) 47. doi: 10.1186/s12977-017-0370-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Patterson KB, Prince HA, Kraft E, Jenkins AJ, Shaheen NJ, Rooney JF, Cohen MS, Kashuba ADM, Penetration of tenofovir and emtricitabine in mucosal tissues: implications for prevention of HIV-1 transmission., Sci. Transl. Med 3 (2011) 112re4. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3003174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].U. Office of AIDS Research and Advisory Council, Department of Health and Human Services, Guidelines for the Use of Antiretroviral Agents in Adults and Adolescents Living with HIV, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- [33].Simiele M, Ariaudo A, De Nicolò A, Favata F, Ferrante M, Carcieri C, Bonora S, Di Perri G, De Avolio A, UPLC-MS/MS method for the simultaneous quantification of three new antiretroviral drugs, dolutegravir, elvitegravir and rilpivirine, and other thirteen antiretroviral agents plus cobicistat and ritonavir boosters in human plasma., J. Pharm. Biomed. Anal 138 (2017) 223–230. doi: 10.1016/j.jpba.2017.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Dilly S, Fawcett S, Else L, Egan D, Amara A, Elliot E, Challenger E, Back D, Boffito M, Khoo S, The development and application of a novel LC – MS / MS method for the measurement of Dolutegravir, Elvitegravir and Cobicistat in human plasma, J. Chromatogr. B 1027 (2016) 174–180. doi: 10.1016/j.jchromb.2016.05.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Gomes NA, Vaidya VV, Pudage A, Joshi SS, Parekh SA, Liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS) method for simultaneous determination of tenofovir and emtricitabine in human plasma and its application to a bioequivalence study., J. Pharm. Biomed. Anal 48 (2008) 918–26. doi: 10.1016/j.jpba.2008.07.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Prathipati PK, Mandal S, Destache CJ, Simultaneous quantification of tenofovir, emtricitabine, rilpivirine, elvitegravir and dolutegravir in mouse biological matrices by LC-MS/MS and its application to a pharmacokinetic study., J. Pharm. Biomed. Anal 129 (2016) 473–481. doi: 10.1016/j.jpba.2016.07.040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Delahunty T, Bushman L, Robbins B, Fletcher CV, The simultaneous assay of tenofovir and emtricitabine in plasma using LC/MS/MS and isotopically labeled internal standards, J. Chromatogr. B Anal. Technol. Biomed. Life Sci 877 (2009) 1907–1914. doi: 10.1016/j.jchromb.2009.05.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Ouyang B, Zhou F, Zhen L, Peng Y, Sun J, Chen Q, Jin X, Wang G, Zhang J, Simultaneous determination of tenofovir alafenamide and its active metabolites tenofovir and tenofovir diphosphate in HBV-infected hepatocyte with a sensitive LC-MS/MS method., J. Pharm. Biomed. Anal 146 (2017) 147–153. doi: 10.1016/j.jpba.2017.08.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Tsuchiya K, Ohuchi M, Yamane N, Aikawa H, Gatanaga H, Oka S, Hamada A, High-performance liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry for simultaneous determination of raltegravir, dolutegravir and elvitegravir concentrations in human plasma and cerebrospinal fluid samples., Biomed. Chromatogr 32 (2018). doi: 10.1002/bmc.4058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].FDA, Guidance for Industry Bioanalytical Method Validation, 2018.

- [41].I. Gilead Sciences, Emtriva® [Package Insert], 2012.

- [42].I. Glaxosmithkline, TIVICAY ® [Package Insert], 2013.

- [43].I. Gilead Sciences, Viread® [Package Insert], 2012.

- [44].Ocque AJ, Hagler CE, Morse GD, Letendre SL, Ma Q, Development and validation of an LC–MS/MS assay for tenofovir and tenofovir alafenamide in human plasma and cerebrospinal fluid, J. Pharm. Biomed. Anal 156 (2018) 163–169. doi: 10.1016/j.jpba.2018.04.035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [45].Shaw JP, Sueoko CM, Oliyai R, Lee WA, Arimilli MN, Kim CU, Cundy KC, Metabolism and pharmacokinetics of novel oral prodrugs of 9-[(R)-2-(phosphonomethoxy)propyl]adenine (PMPA) in dogs., Pharm. Res 14 (1997) 1824–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [46].Anderson PL, Kiser JJ, Gardner EM, Rower JE, Meditz A, Grant RM, Pharmacological considerations for tenofovir and emtricitabine to prevent HIV infection, J. Antimicrob. Chemother 66 (2011) 240–250. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkq447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [47].Carl SM, Lindley DJ, Das D, Couraud PO, Weksler BB, Romero I, Mowery SA, Knipp GT, ABC and SLC transporter expression and proton oligopeptide transporter (POT) mediated permeation across the human blood--brain barrier cell line, hCMEC/D3 [corrected]., Mol. Pharm 7 (2010) 1057–68. doi: 10.1021/mp900178j. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [48].Ohtsuki S, Ikeda C, Uchida Y, Sakamoto Y, Miller F, Glacial F, Declèves X, Scherrmann J-M, Couraud P-O, Kubo Y, Tachikawa M, Terasaki T, Quantitative Targeted Absolute Proteomic Analysis of Transporters, Receptors and Junction Proteins for Validation of Human Cerebral Microvascular Endothelial Cell Line hCMEC/D3 as a Human Blood–Brain Barrier Model, Mol. Pharm 10 (2013) 289–296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [49].Geier EG, Chen EC, Webb A, Papp AC, Yee SW, Sadee W, Giacomini KM, Profiling solute carrier transporters in the human blood-brain barrier., Clin. Pharmacol. Ther 94 (2013) 636–9. doi: 10.1038/clpt.2013.175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [50].Reese MJ, Savina PM, Generaux GT, Tracey H, Humphreys JE, Kanaoka E, Webster LO, Harmon KA, Clarke JD, Polli JW, In vitro investigations into the roles of drug transporters and metabolizing enzymes in the disposition and drug interactions of dolutegravir, a HIV integrase inhibitor, Drug Metab. Dispos 41 (2013) 353–361. doi: 10.1124/dmd.112.048918. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]