Abstract

Objective

To describe associations between childhood violence and forced sexual initiation in young Malawian females.

Study design

We analyzed data from 595 women and girls who were 13-24 years old who ever had sex and participated in Malawi’s 2013 Violence Against Children Survey, a nationally representative household survey. We estimated the overall prevalence of forced sexual initiation and identified subgroups with highest prevalences. Using logistic regression, we examined childhood violence and other independent predictors of forced sexual initiation.

Results

The overall prevalence of forced sexual initiation was 38.9% among Malawian girls and young women who ever had sex. More than one-half of those aged 13-17 years at time of survey (52.0%), unmarried (64.6%), or experiencing emotional violence in childhood (56.9%) reported forced sexual initiation. After adjustment, independent predictors of forced sexual initiation included being unmarried (aOR, 3.54; 95% CI, 1.22-10.27) and any emotional violence (aOR, 2.47; 95% CI, 1.45-4.24). Those experiencing emotional violence alone (aOR, 3.04; 95% CI: 1.01-9.12), emotional violence in combination with physical or nonpenetrative sexual violence (aOR, 2.50; 95% CI, 1.23-5.09), and emotional violence in combination with physical and nonpenetrative sexual violence (aOR, 2.61; 95% CI, 1.20-5.67) had an increased independent odds of forced sexual initiation.

Conclusions

Experiences of forced sexual initiation are common among Malawian females. Emotional violence is strongly associated with forced sexual initiation, alone and in combination with other forms of childhood violence. The relationship between emotional violence and forced sexual initiation highlights the importance of comprehensive strategies to prevent childhood violence.

Childhood sexual violence is one of the most disturbing children’s rights violations, affecting more than 250 million children before age 18 years.1,2 Emotional and physical impacts of violent childhood experiences are serious and long lasting.3–7 Moreover, the consequences of violence are additive, worsening in severity with the increasing number and gravity of violent experiences.3–8 Childhood sexual violence is associated with subsequent chronic disease, sexually transmitted infections like HIV, mental illness, violence perpetration, and victimization as an adult.6,9,10 Sexual violence exists on a continuum, from unwanted sexual touching and sexual harassment to forced sexual intercourse.11,12

Forced sexual initiation takes place when a first sexual intercourse experience results from physical force or psychological coercion. In some parts of the world, more than one-third of adolescent girls experience forced sexual initiation.13 It is feasible that many risk factors for forced sexual initiation coincide with risk factors for other forms of sexual violence. Sexual initiation ceremonies are one context in which forced sexual initiation takes place; however, forced sexual initiation is not limited to rites of passages.14 Forced sexual initiation may bear some unique determinants.15

The consequences of forced sexual initiation are significant and far-reaching, bearing some resemblance to the consequences of sexual violence in general, including an increased risk of subsequent sexual victimization and HIV infection.16,17 Poor mental health outcomes such as depression, post-traumatic stress disorder, and substance abuse are associated with forced sexual debut.16–20 Adolescent girls are at particularly high risk of HIV acquisition after forced sex owing to the friability of pubertal vaginal tissue, downregulation of immune response, and adverse effects on individual self-efficacy and sexual risk taking.16,17 Survivors of forced sexual initiation engage in riskier sexual behavior, including multiple or concurrent partners, transactional sex, and inconsistent condom use.17 One study of adolescent females in South Africa found the risk of teenage pregnancy was 14.4 times higher among girls who experienced forced sexual initiation.21

Girls in Africa experience sexual violence at rates higher than any other region.2 Childhood sexual violence is particularly troublesome in countries with endemic levels of HIV, where forced or coerced sex may result in a lifetime of disease.16,17,22–24 Studies also suggest that violence may be associated with antiretroviral failure, leading to an increased risk of HIV transmission and progression among victims of violence.25 The elimination of violence against women and children has become a fundamental strategy for advancing HIV prevention.26,27 Malawi has one of the world’s highest HIV prevalences.28 In 2013, the Malawi Violence Against Children Survey (VACS) found that 21.8% of females aged 18-24 years experienced sexual violence in their childhood.29 Among 13- to 17-year-olds in Malawi, 22.8% of girls reported experiencing sexual abuse in the previous 12 months. Furthermore, 1 in 4 girls experienced more than 1 type of violence.

In the wake of these findings, Malawi’s government developed a National Plan of Action for Vulnerable Children with the aim of establishing an operational National Child Protection System.30 This plan incorporated and strengthened existing strategies, policies and laws to improve the prevention and treatment of childhood sexual abuse in Malawi. One research priority highlighted by the plan was better understanding of the enduring effects of violence against children.30 The objectives of our hypothesis-generating study were to describe the prevalence and characteristics of forced sexual initiation among girls in Malawi, and to identify any associations between childhood experiences of violence and forced sexual initiation.

Methods

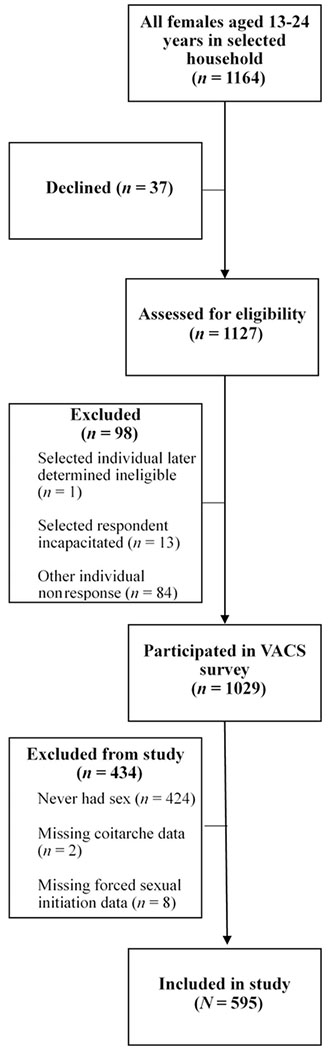

The 2013 VACS Malawi was a nationally representative, cross-sectional household survey about childhood experiences of violence conducted with technical assistance by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) and the Malawi Ministry of Gender, Children, Disability and Social Welfare, in collaboration with United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF) and the Center for Social Research at the University of Malawi. Youth aged 13-24 years were questioned about experiences of physical, emotional, and sexual violence before age 18 years to produce national estimates of violence against children.29 Our study focused on the responses from Malawian females who ever had sex and reported type of sexual initiation (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Flow chart of survey participation and study desgin.

VACS Malawi used a multistage, geographically clustered study design based on enumeration areas from Malawi’s 2008 population and housing census. The survey used a split-sample approach, separating enumeration areas for females and males, to protect the confidentiality of respondents and reduce the likelihood of interviewing both a perpetrator and a victim in the same setting. In stage 1, 849 enumeration areas were selected by probability proportional to size. During stage 2, 212 enumeration areas were selected by probability proportional to size and stratified by region. Enumeration areas with more than 250 households were geographically subsampled. In the third stage, a fixed number of 30 households were selected by equal probability systematic sampling. In the last stage, 1 participant aged 13-24 years was randomly selected using the Kish method.31 Males and females living in selected households, aged 13-24 years at the time of survey, and who spoke Chichewa or Tumbuka were eligible to participate in the survey. Individuals with mental disabilities who did not have the capacity to understand the questions being asked or those with physical disabilities (eg, hearing and speech impairment) that prevented the interviewer from administering the surveys were excluded from the study. Additionally, children and young adults living in institutions such as hospitals, prisons, nursing homes, and other such establishments were not included in the survey.

The sample size was determined from a standard cluster sample formula using an estimated prevalence of 30% for childhood sexual violence, based on previous VACS studies conducted in Tanzania, Kenya, and Zimbabwe. Data collection occurred between April 2013 and May 2013. VACS Malawi was translated into Chichewa and Tumbuka and pilot tested in 2 urban and 2 rural communities before administration.

Ethical Considerations

For all selected eligible respondents under the age of 18 years, interviewers obtained permission from a parent/caregiver before speaking with the eligible respondent. The World Health Organization (WHO) ethical and safety guidelines for violence research were adapted for the study protocol, informing parents and primary caregivers as fully as possible about the survey without risking possible retaliation against children for their participation.32 Participants under the age of 18 years provided verbal informed assent; participants aged 18-24 years old provided verbal informed consent. Questionnaires were administered in person by Malawian interviewers trained in confidential data collection, subject matter sensitivity, and informed consent. Gender-matched interviewers conducted interviews with respondents in privacy. Survey workers used prepared response plans to link respondents with social services and respond to cases of immediate danger. Approval was obtained from CDC’s Institutional Review Board and Malawi’s National Commission for Science and Technology Ethics Review Board.

Definitions

VACS Malawi evaluated multiple forms of violence, as well as risk-taking behaviors, demographics, household characteristics, and familial and peer relationships. Survey questions inquired about victimization experiences in 3 timeframes: lifetime, before age 18 years, and past 12 months before interview. Our analysis focused on participants’ experiences of 4 forms of childhood violence: physical violence, emotional violence, nonpenetrative sexual violence, and forced sexual initiation. Childhood physical violence was defined as being punched, kicked, whipped, beaten, choked, smothered, threatened with a weapon, attempted drowning, or intentionally burnt by a parent, adult caregiver, adult relative, adult in the community, or peer before the age of 18 years. Childhood emotional violence described events where a respondent was told by her parents or caregivers that she was not loved, that they wished she had never been born, or she was ridiculed or put down before the age of 18 years. Nonpenetrative sexual violence included unwanted sexual touching on the genitalia, anus, groin, breast, inner thigh, or buttocks; requests to trade sexual acts for goods or money; or unwanted attempted sex at any age before sexual initiation. Sex was defined as someone penetrating the respondent’s vagina or anus by penis, hands, fingers, mouth, or an object; or penetrating the respondent’s mouth with his penis. Forced sexual initiation was defined as being coerced or forced to have sex at one’s first experience of sexual intercourse at any age.

In addition to childhood experiences of violence, demographic correlates explored in our analysis included age, marital status, education, household socioeconomic status, and closeness with parents or friends. Girls and women were considered married if they had ever been married or lived with a partner. For level of education, responses were grouped into primary or less, and secondary or more. Respondents with no education were included in the less than primary group.

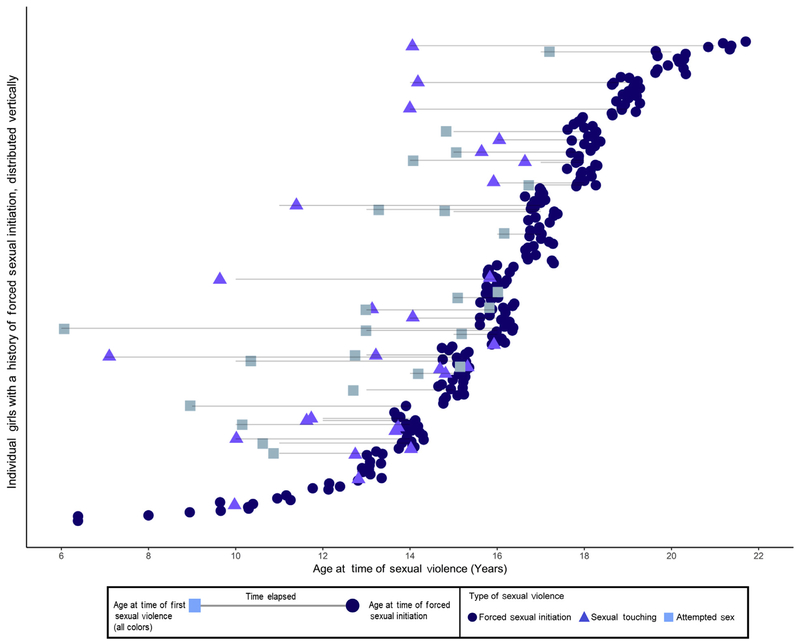

The availability of age data varied for emotional, physical, and nonpenetrative sexual violence events. Age at first exposure to nonpenetrative sexual violence was coded in 1-year increments, allowing for confirmation that this type of exposure preceded forced sexual initiation. Although analyses addressing the influence of emotional violence and physical violence on forced sexual initiation were restricted to experiences of these types of violence during childhood, we included nonpenetrative sexual violence events occurring before and after age 18 years, as long as they occurred before sexual initiation. To better understand the temporal relationship between experiences of nonpenetrative sexual violence preceding forced sexual initiation, we created a timeline of sexual violence events among girls experiencing forced sexual initiation, depicted in Figure 2 (available at www.jpeds.com).

Figure 2.

Age at experiencing forced sex and preceding episodes of unwanted sexual touching and attempted sex among Malawian girls and women aged 13-24 years who ever had sex (n = 239).

Statistical Analyses

We estimated weighted lifetime prevalence of forced sexual initiation and childhood physical, emotional, and nonpenetrative sexual violence. Logistic regression examined associations between childhood violence and forced sexual initiation. Potential confounders between exposure to violence in childhood and forced sexual initiation were evaluated in bivariate analyses; all variables demonstrating significant associations with forced sexual initiation—defined as P ≤ .1—were included in the adjusted models. These variables included age at time of survey, marital status, and age at sexual debut. A series of sensitivity analyses were performed to investigate the robustness of the study results. We explored adjusted models examining forms of violence independently and in combination, as well as reclassification of all sex before the age of 16 years as forced. All sensitivity analyses yielded similar results. Orphan and child-headed household status were unable to be assessed owing to rarity of events. Missing data were low for all study variables (range, 0.0%-3.2%) and were excluded from the denominators of calculations. Because screening showed no particular patterns among missing data, the missing mechanism was assumed to be missing at random and no imputation was carried out. We used SAS version 9.4 software (SAS Institute Inc, Cary, North Carolina) for data management and analysis and R version 3.4.0 software (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria) for data visualization. All analyses accounted for complex survey designs using SAS SURVEY commands.

Results

In total, 1029 females aged 13-24 years were interviewed, with an overall response rate of 84.4% (Figure 1). Among VACS Malawi female participants, 58.1% (95% CI, 50.0%-66.3%; n = 595) were sexually active and reported type of sexual initiation. Age of sexual debut was 17 years or younger in 67.8% (95% CI, 62.5%-73.2%) of participating girls and women; 14.7% of sexually active female participants (95% CI, 11.2%-18.1%) were aged 13-17 years at the time of the survey (Table I). Overall, 46.6% of participants (95% CI, 41.3%-51.8%) experienced some form of physical violence in childhood. One in 4 girls reported at least 1 experience of emotional violence (24.3%; 95% CI, 18.4%-30.2%) or nonpenetrative sexual violence (28.3%; 95% CI, 24.4%-32.3%) in childhood.

Table I.

Descriptive characteristics of Malawian females (n = 595) aged 13-24 years who have ever had sex, 2013

| Characteristics | Weighted % (n/N) | 95% CI, % |

|---|---|---|

| Age of survey participant | ||

| 13-17 years | 14.7 (94/595) | 11.2-18.1 |

| 18-24 years | 85.3 (501/595) | 81.9-88.8 |

| Marital status* | ||

| Unmarried | 17.7 (109/595) | 12.3-23.1 |

| Married or living as married | 82.3 (486/595) | 76.9-87.7 |

| Highest level of education | ||

| Primary or less† | 79.8 (444/594) | 72.2-87.4 |

| Secondary or more | 20.2 (150/594) | 12.6-27.8 |

| Social relationships | ||

| Peer support‡ | ||

| Yes | 62.5 (379/591) | 56.0-69.1 |

| No | 37.5 (212/591) | 30.9-44.0 |

| Parental support§ | ||

| Yes | 73.7 (462/587) | 68.3-79.2 |

| No | 26.3 (125/587) | 20.8-31.7 |

| Childhood exposure to violence | ||

| Any physical violence¶ | ||

| Yes | 46.6 (281/576) | 41.3-51.8 |

| No | 53.4 (295/576) | 48.2-58.7 |

| Any emotional violence** | ||

| Yes | 24.3 (150/587) | 18.4-30.2 |

| No | 75.7 (437/587) | 69.8-81.6 |

| Any nonpenetrative sexual violence†† | ||

| Yes | 28.3 (179/595) | 24.4-32.3 |

| No | 71.7(416/595) | 67.7-75.6 |

| Forced sexual initiation | ||

| Yes | 38.9 (239/595) | 32.2-45.7 |

| No | 61.1 (356/595) | 54.3-67.8 |

Ever married or ever living together.

Completed primary school or less.

(Talks to friends “a lot” or “a little” about important things.

Felt “very close” or “close” to one or both biological parents.

Physical violence defined as respondent being punched, kicked, whipped, beat, choked, smothered, drowned, intentionally burnt by a parent, adult in the household, adult in the community, or peer before age 18 years.

Emotional violence defined as respondent being told as a child by her parents or caregivers that she was not loved; that they wished she had never been born; or she was ridiculed or put down before age 18 years.

Nonpenetrative sexual violence defined as sexual exploitation, unwanted touching, or attempted sex at any age, but preceding sexual debut.

Forced sexual initiation occurred among 38.9% of all sexually active girls (95% CI, 32.2%-45.7%) and young women in Malawi. The mean age of first sexual intercourse was significantly lower among girls experiencing forced first sex (15.7 years) vs consensual first sex (16.4 years; P < .001). Among females experiencing forced sexual initiation, more than one-half were aged 13-17 years old at the time of survey (52.0%; 95% CI, 41.8%-62.2%), unmarried (64.6%; 95% CI, 48.5%-80.7%), or had experienced childhood emotional violence (56.9%; 95% CI, 47.3%-66.5%; Table II).

Table II.

Childhood exposures to violence, demographics, and forced sexual initiation among sexually active girls and young women (n = 595) aged 13-24 years in Malawi, 2013

| Forced sexual initiation |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristics | Weighted % (n/N) | OR (95% CI) | P value | aOR (95% CI)* | P value |

| Demographics | |||||

| Age of survey participant | |||||

| 13-17 years | 52.0 (49/94) | 1.87 (1.23-2.84) | .004 | 0.89(0.50-1.61) | 0.71 |

| 18-24 years | 36.7 (190/501) | Referent | Referent | ||

| Marital status | |||||

| Unmarried | 64.6 (62/109) | 3.64 (1.71-7.73) | .001 | 3.54 (1.22-10.27) | .02 |

| Married or living as married† | 33.4 (177/486) | Referent | Referent | ||

| Childhood exposure to violence | |||||

| Any physical violence‡ | |||||

| Yes | 43.0 (129/281) | 1.37(0.86-2.18) | .18 | 1.17(0.68-2.02) | .56 |

| No | 35.6 (102/295) | Referent | Referent | ||

| Any emotional violence§ | |||||

| Yes | 56.9 (73/150) | 2.72 (1.61-4.60) | <.001 | 2.47 (1.45-4.24) | .001 |

| No | 32.7 (160/437) | Referent | Referent | ||

| Any nonpenetrative sexual violence¶ | |||||

| Yes | 47.5 (93/179) | 1.63 (1.08-2.49) | .02 | 1.31 (0.86-2.01) | .2 |

| No | 35.6 (146/416) | Referent | Referent | ||

Adjusted for age at time of survey, marital status, age at sexual debut.

Ever married or ever living together.

Physical violence defined as respondent being punched, kicked, whipped, beat, choked, smothered, attempted drowning, intentionally burnt by a parent, adult in the household, adult in the community, or peer before age 18 years.

violence defined as respondent being told as a child by her parents or caregivers that she was not loved; that they wished she had never been born; or she was ridiculed or put down before age 18 years.

Nonpenetrative sexual violence defined as unwanted sexual touching; participation in explicit photos, videos or webcam; or unwanted attempted sex at any age, but preceding sexual debut.

In the first stage of logistic regression modeling, unadjusted analyses demonstrated significant positive associations between any childhood emotional violence, nonpenetrative sexual violence, and forced sexual initiation. In the adjusted model, experiencing any emotional violence as a child was significantly associated with forced sexual initiation (aOR, 2.47; 95% CI, 1.45-4.24; P = .001). Nearly one-half of forced sexual initiation victims (47.5%; 95% CI, 37.8%-57.1%) experienced nonpenetrative sexual violence before forced sexual initiation, but a history of nonpenetrative sexual violence before sexual debut was not significantly associated with forced sexual initiation in the adjusted model (aOR, 1.31; 95% CI, 0.86-2.01; P = .20; Table II). Figure 2 displays the temporal relationship between nonpenetrative sexual violence and girls experiencing forced sexual initiation. No statistically significant associations between childhood physical violence and forced sexual initiation were detected.

Among girls experiencing emotional violence, the majority experienced at least 1 additional form of childhood violence (85.4%; 95% CI, 79.9%-91.0%). The analysis of polyvictimization was limited to participants who answered all applicable questions about experiences of violence (n = 569). To further explore the relationship between childhood experiences of emotional violence and forced sexual initiation, we examined women with reported exposures to emotional violence alone, emotional violence plus 1 additional form of violence (physical or nonpenetrative sexual violence), and emotional violence plus 2 additional forms of violence (physical and nonpenetrative sexual violence; Table III). The adjusted odds of experiencing forced sexual initiation were 3.04 times higher among girls experiencing emotional violence alone (95% CI, 1.01-9.12; P = .048) compared with girls experiencing no violence in childhood. We also detected significant associations between forced sexual initiation and emotional violence plus 1 additional form of violence (aOR, 2.50; 95% CI, 1.23-5.09; P = .01) and emotional violence plus 2 additional forms of violence (aOR, 2.61; 95% CI, 1.20-5.67; P = .02; Table III). Nearly two-thirds of girls (62.0%; 95% CI, 46.7%-77.3%) exposed to all 3 forms of childhood violence experienced forced sexual initiation (Table III). In additional subgroup analyses (data not shown), we found that the relationship we observed for emotional violence was not present for the other types of childhood violence considered. Consideration of physical violence alone, and nonpenetrative sexual violence alone, was not statistically significant in the adjusted models (although nonpenetrative sexual violence was predictive, as shown previously, in the unadjusted analysis); after adjustment, these predictors only attained significance when they were experienced in combination with emotional violence.

Table III.

Childhood exposures to different forms of violence and forced sexual initiation among Malawian girls and young women aged 13-24 years (n = 569) who ever had sex, 2013*

| Forced first sexual intercourse |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristics | Weighted % (n/N) | Unadjusted OR (95% CI) | P value | aOR (95% CI)† | P value |

| Forms of violence experienced in childhood | |||||

| None | 32.6 (153/422) | 1.00 (Reference) | – | 1.00 (Reference) | – |

| EV only‡ | 55.7 (13/32) | 2.60 (0.89-7.57) | .08 | 3.04 (1.01-9.12) | .048 |

| EV + 1 form of violence (PV or NPSV)§ | 55.4 (26/60) | 3.38 (1.55-7.34) | .003 | 2.50 (1.23-5.09) | .01 |

| EV + 2 forms of violence (PV and NPSV) | 62.0 (34/55) | 2.57 (1.15-5.76) | .02 | 2.61 (1.20-5.67) | .02 |

EV, Emotional violence; NPSV, nonpenetrative sexual violence; PV physical violence.

Only participants who answered questions on all forms of violence were included in analysis (n = 569).

Adjusted for age at time of survey, marital status, age at sexual debut.

EV defined as respondent being told as a child by her parents or caregivers that she was not loved; that they wished she had never been born; or she was ridiculed or put down before age 18 years.

NPSV is defined as sexual exploitation, transactional sex, unwanted touching, or attempted sex at any age but preceding sexual debut. PV is defined as respondent being punched, kicked, whipped, beat, choked, smothered, attempted drowning, intentionally burnt by a parent, adult in the household, adult in the community, or peer before age 18 years.

Discussion

We found a strong association between childhood experiences of emotional violence and forced sexual initiation, even after adjusting for sociodemographic factors and age of sexual debut. After adjustment, other forms of childhood violence only demonstrated significant associations with forced sexual initiation when experienced in concert with emotional violence, suggesting that emotional violence may be the primary driver of this relationship.

Emotional violence is an underappreciated risk factor for adverse health outcomes. In part, emotional violence indicators serve as a proxy for the quality of attachment relationships and a model for future relationships.33 By diminishing children’s agency and self-image, emotional violence may increase risk-taking behavior, influence choice of peers and partners, and increase vulnerability to forced sexual initiation. Furthermore, protective parental factors, such as parental supervision, may be more likely to be absent when emotional violence is present.

Studies have demonstrated the unique contribution of childhood emotional violence to mental health disorders including depression, anxiety, and disordered eating. A 2014 study of mental health outcomes among victims of psychological maltreatment found that victims of childhood emotional violence suffered from mental illness at similar or higher frequency than victims of other forms of violence.34 In terms of treatment and prevention, policies specifically targeting emotional violence are rare in Malawi or elsewhere.35 The relationship between emotional violence and later risk of sexual victimization has been largely unexplored.

Forced sexual initiation is common in many countries, including Malawi. More than 50% of sexually active girls aged 13-17 years had forced first sex in Malawi—one of the highest forced sexual initiation prevalences ever reported in adolescent girls. A 2005 WHO multicountry study of girls aged 13-17 years estimated prevalence of forced sexual initiation to be 4.6%-32.2%.13 Previous VACS surveys in sub-Saharan Africa reported forced sexual initiation prevalence between 24.3% and 61.7% for girls aged 13-17 years.

The findings from this study are subject to some limitations. First, given the cross-sectional nature of the study, information collected is dependent on participant recall. The ages of victimization for some experiences of violence were collected in relatively broad time increments, limiting our ability to ensure definitive temporal associations between the hypothesized outcome and exposure. VACS data from Malawi and other countries supports the assumption that physical violence and emotional violence generally occur at younger ages than sexual violence. Second, we analyzed a subsample of sexually active females; in some instances, the number of responses for a measure was small, affecting the power to detect differences. Although our data did not detect associations between forced sexual initiation and preceding physical or sexual violence, it is plausible that a larger study sample would find associations between other forms of childhood violence and forced sexual initiation. Small subsample size also affected our ability to examine household indicators like orphan status and child-headed households. These household-level factors could put children at risk for both emotional violence and forced sexual initiation. Additionally, the exclusion of individuals with mental or physical disabilities from our survey population increases the likelihood that the true prevalence of forced sexual initiation is greater than reported; this population is known to have a higher risk of maltreatment.36 Moreover, the sensitive subject matter of the survey may cause participants to underreport their experiences, leading to underestimation of forced sexual initiation prevalence. Last, it is possible that our conclusions are not generalizable beyond Malawi. This is unlikely, because emotional violence occurs in all cultures and many risk factors for violence transcend socioeconomic and geophysical boundaries. A further analysis of forced sexual initiation in other settings is merited.

Understanding the risk factors for forced sexual debut may help to prevent this and other forms of sexual violence. Emotional violence may be 1 such risk factor; future studies permitting causal analysis are needed to elucidate emotional violence’s role. More research is also needed on forced sexual initiation: when and where does it occur, who is affected, and who are the perpetrators. The potential relationship between emotional violence and later sexual victimization highlights the interrelation of types of violence and underscores the need for effective interventions to mitigate the negative consequences of emotional violence.

Health care providers should be aware of the signs, symptoms, and consequences of emotional violence and be prepared to support families at risk for—or experiencing—this problem.37 Providers should feel comfortable assessing parent–child interactions, speaking with children about their relationships with caregivers, and asking about experiences of discipline, self-worth, and feeling loved. If psychological abuse or neglect is suspected, it is important for pediatricians to refer to child protective services—in accordance with individual state laws—and assist families in accessing appropriate resources, such as referrals to mental health professionals and substance misuse treatment programs. Emotional violence often co-occurs with other forms of childhood violence, including forced sexual initiation, and providers should feel comfortable assessing the full spectrum of childhood violence.

Violence against children is preventable.38 Violence prevention programs may play an important role in reducing all forms of violence against children, including forced sexual initiation. The INSPIRE framework, developed in 2016 by 10 key global organizations including the WHO and the CDC, provides evidence-based violence reduction strategies spanning health, social services, education, and justice.39 Parenting programs like Families Matter! and Parenting for Lifelong Health reduce physical, emotional, and sexual violence by caregivers and peers by enhancing protective parenting practices and promoting nurturing familial relationships.40 Globally, organizations have begun investing in these evidence-based strategies to prevent childhood violence. The DREAMS partnership, established in 2014 by the US President’s Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief, highlights familial strengthening as a key strategy to address structural drivers of girls’ HIV risk, and provides support for such evidence-based parenting programs in Malawi.27 For example, parent/caregiver financial stress has been demonstrated to be a risk factor for emotional and physical abuse. DREAMS alleviates financial stress by assisting families with their ability to pay for the educational expenses of their female children (eg, paying school fees, transport costs, uniforms, and books). WHO and UNICEF launched the Nurturing Care Framework to promote early childhood development and emotional health through policy, programs, and financial support of participating countries.41 Pediatric advocacy and investments in early childhood development, parenting, and supportive relationships are essential steps towards ending all forms of childhood violence, along with its destructive and enduring consequences.

Acknowledgments

We thank the survey participants for bravely sharing their experiences of violence. We also thank the survey team leaders and interviewers for their professionalism and sensitivity in interviewing children and young adults, prioritizing their safety and privacy. Last, we thank Dr Likang Xu for his statistical expertise.

Funding for the implementation and coordination of the survey was provided by the government of the United Kingdom. The Ministry of Gender, Children, Disability and Social Welfare (MoGCDSW), the Center for Social Research at the University of Malawi, the United Nations Children’s Fund in Malawi (UNICEF Malawi), and the President’s Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief (PEPFAR) conducted the Violence Against Children and Young Women survey in Malawi (VACS Malawi). Centers for Diseases Control and Prevention (CDC) personnel, while not funding the program directly, provided programmatic and technical guidance in country. The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Glossary

- CDC

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

- UNICEF

United Nations Children’s Fund

- VACS

Violence Against Children Survey

- WHO

World Health Organization

Footnotes

Data Statement

Data sharing statement available at www.jpeds.com.

Portions of this study were presented at the Epidemic Intelligence Service Conference, April 16-29, 2018, Atlanta, Georgia.

References

- 1.Krug EG, Dahlberg LL. Violence: A global public health problem. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Stoltenborgh M, IJzendoorn MHv, Euser EM, Bakermans-Kranenburg MJ. A global perspective on child sexual abuse: meta-analysis of prevalence around the world. Child Maltreatment 2011;16:79–101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Felitti VJ, Anda RF, Nordenberg D, Williamson DF, Spitz AM, Edwards V, et al. Relationship of childhood abuse and household dysfunction to many of the leading causes of death in adults. The Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACE) Study. Am J Prev Med 1998;14:245–58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hillis S, Anda RF, Felitti VJ, Marchbanks PA. Adverse childhood experiences and sexual risk behaviors in women: a retrospective cohort study. Family Plan Perspect 2001;33:206–11. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hillis SD, Anda RF, Dube SR, Felitti VJ, Marchbanks PA, Marks JS. The association between adverse childhood experiences and adolescent pregnancy, long-term psychosocial consequences, and fetal death. Pediatrics 2004;113:320–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Anda RF, Felitti VJ, Bremner JD, Walker JD, Whitfield C, Perry BD, et al. The enduring effects of abuse and related adverse experiences in childhood. Eur Arch Psychiatr Clin Neurosci 2006;256:174–86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fergusson DM, McLeod GF, Horwood LJ. Childhood sexual abuse and adult developmental outcomes: findings from a 30-year longitudinal study in New Zealand. Child Abuse Negl 2013;37:664–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jina R, Thomas LS. Health consequences of sexual violence against women. Best Pract Res Clin Obstet Gynaecol 2013;27:15–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jewkes R, Dunkle KL, Koss MP, Levin JB, Nduna M, Jama N, et al. Rape perpetration by young, rural South African men: prevalence, patterns and risk factors. Soc Sci Med 2006;63:2949–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tsai AC, Leiter K, Heisler M, Iacopino V, Wolfe W, Shannon K, et al. Prevalence and correlates of forced sex perpetration and victimization in Botswana and Swaziland. Am J Public Health 2011;101:1068–74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kelly L The continuum of sexual violence In: Hanmer J, Maynard M, eds. Women, violence and social control: explorations in sociology. London:Palgrave Macmillan; 1987. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Basile KC, Smith SG, Breiding MJ, Black MC, Mahendra R. Sexual violence surveillance: Uniform definitions and recommended data elements, Version 2.0. Atlanta, GA: National Center for Injury Prevention and Control, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Garcia-Moreno C, Jansen HAFM, Ellsberg M, Heise L, Watts C WHO multi-country study on women’s health and domestic violence against women: Initial results on prevalence, health outcomes and women’s responses. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Malawi Human Rights Commission. Cultural practices and their impact on the enjoyment of human rights, particularly the rights of women and children in Malawi. Lilongwe:Malawi Human Rights Commission; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bott S, Guedes A, Goodwin M, Mendoza J. Violence against women in Latin America and the Caribbean: A comparative analysis of population-based data from 12 countries. Washington, DC: Pan American Health Organization; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Campbell JC, Lucea MB, Stockman JK, Draughon JE. Forced sex and HIV risk in violent relationships. Am J Reprod Immunol 2013;69(Suppl 1):41–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Stockman JK, Lucea MB, Campbell JC. Forced sexual initiation, sexual intimate partner violence and HIV risk in women: a global review of the literature. AIDS Behav 2013;17:832–47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Maman S, Campbell JC, Sweat M, Gielen A. The intersections of HIV and violence: directions for future research and interventions. Soc Sci Med 2000;50:459–78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Thompson N, Potter J, Sanderson C, Maibach E. The relationship of sexual abuse and HIV risk behaviors among heterosexual adult female STD patients. Child Abuse Negl 1997;21:49–156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Klot J, Auerbach J, Berry M. Sexual violence and HIV transmission: summary proceedings ofa scientific research planning meeting. Am J Reprod Immunol 2013;69:5–19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jewkes R, Vundule C, Maforah F, Jordaan E. Relationship dynamics and teenage pregnancy in South Africa. Soc Sci Med 2001;52:733–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Richter L, Komarek A, Desmond C, Celentano D, Morin S, Sweat M, et al. Reported physical and sexual abuse in childhood and adult HIV risk behaviour in three African countries: findings from Project Accept (HPTN-043). AIDS Behav 2014;18:381–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Singh AK, Sinha RK, Jain R. Examining nonconsensual sex and risk of reproductive tract infections and sexually transmitted infections among young married women in India Gender-based violence: Perspective from Africa, the Middle East, and India. New York: Springer International Publishing; 2015. p. 169–93. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sommarin C, Kilbane T, Mercy JA, Moloney-Kitts M, Ligiero DP. Preventing sexual violence and HIV in children. J AIDS 2014;66:S217–23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Machtinger E, Haberer J, WIlson T, Weiss D. Recent trauma is associated with antiretroviral failure & HIV transmission risk behavior among HIV-positive women and female-identified transgenders. AIDS Behav 2012;16:2160–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Institute of Medicine. Evaluation of PEPFAR. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 27.United States President’s Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief, Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, GirlEffect, Johnson & Johnson, ViiV Healthcare, Gilead DREAMS Core Package of Interventions Summary. Washington, DC: Office of the U.S. Global AIDS Coordinator and Health Diplomacy; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 28.The Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS. Geneva, Switzerland: UNAIDS; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ministry of Gender, Children, Disability and Social Welfare of the Republic of Malawi, United Nations Children’s Fund, The Center for Social Research at the University of Malawi, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Violence against children and young women in Malawi: Findings from a national survey, 2013. Lilongwe, Malawi: Ministry of Gender, Children, Disability and Social Welfare of the Republic of Malawi, United Nations Children’s Fund, The Center for Social Research at the University of Malawi, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ministry of Gender, Children, Disability and Social Welfare of the Republic of Malawi. Priority responses: Violence against children and young women in Malawi survey (VACS). Malawi: Ministry of Gender, Children, Disability and Social Welfare of the Republic of Malawi; 2014. p. 20. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kish L A procedure for objective respondent selection within a household. J Am Stat Assoc 1949;44:380–7. [Google Scholar]

- 32.World Health Organization; Guidelines for conducting community surveys on injuries and violence In: Sethie D, Habibula S, McGee K, Peden M, Bennett S, Hyder A, et al. , eds. Guidelines for conducting community surveys on injuries and violence. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bowlby J A secure base: Clinical applications of attachment theory. London: Routledge; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Spinazzola J, Hogdon H, Liang L-J, Ford JD, Layne CM, Pynoos R, et al. Unseen wounds: the contribution of psychological maltreatment to child and adolescent mental health and risk outcomes. Psychol Trauma 2014;6:S18–28. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mellish M, Settergren S, Sapuwa. Gender-based violence in Malawi: A literature review to inform the national response. Washington, DC: Health Policy Project; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Maclean MJ, Sims S, Bower C, Leonard H, Stanley FJ, O’Donnell M. Maltreatment risk among children with disabilities. Pediatrics 2017;139:e20161817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hibbard R, Barlow J, MacMillan H. Psychological maltreatment. Pediatrics 2012;130:372–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.World Health Organization (WHO). Global status report on violence prevention 2014. Geneva, Switzerland: WHO Press; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 39.World Health Organization (WHO). INSPIRE: Seven strategies for ending violence against children. Geneva, Switzerland: WHO; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 40.United National Office on Drugs and Crime. Compilation of evidence-based family skills training programmes. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 41.World Health Organization (WHO).Nurturing care for early childhood development: a framework for action and results. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2018. [Google Scholar]