Abstract

Background:

Previous research on the hormone-symptom relationship in children suggests that certain hormone patterns may be associated with symptoms, but only under certain circumstances. Having a parent with a history of depression may be one circumstance under which dysregulated hormone patterns are especially associated with emotional and behavioral symptoms in children. The current study sought to explore these relationships in a community sample of 389 9-year-old children.

Methods:

Children’s salivary cortisol and testosterone levels were collected at home over three consecutive days; parental psychiatric histories were assessed using semi-structured diagnostic interviews; and children’s internalizing and externalizing symptoms were rated by the child’s mother.

Results:

Having two parents with a history of depression moderated the associations of reduced total daily cortisol output with higher externalizing scores, as well as the association of reduced testosterone with higher internalizing scores. A maternal history of depression, on the other hand, moderated the relationship between higher cortisol awakening response and higher internalizing scores. Furthermore, lower daily cortisol output was associated with higher internalizing scores among girls, but not boys, with two parents with a history depression.

Limitations:

Limitations include the cross-sectional nature of the current analyses, as well as the limited racial, ethnic, and geographical diversity of the sample.

Conclusions:

Taken together, the current results suggest that the relationship between hormones and internalizing and externalizing symptoms in children may vary as a function of parental depression and child sex, knowledge that may inform intervention efforts aimed at preventing psychopathology in children whose parents have a history of depression.

Keywords: Testosterone, cortisol awakening response (CAR), cortisol area under the curve (AUCg), child psychopathology, parental depression

Hormones have significant influences on human behavior and are susceptible to the influence of both chronic and daily stressors (Clowtis, Kang, Padhye, Rozmus, & Barratt, 2016; Shirtcliff & Essex, 2008), such that increased levels of stress can lead to dysregulation of typical hormone patterns (Danese & McEwen, 2012). Such hormone dysregulation has been implicated in a variety of negative mental health outcomes (Koss & Gunnar, 2018).

Hormone dysregulation may also help explain why some children and adolescents are more vulnerable to psychopathology than others. Low morning cortisol and blunted cortisol awakening response (CAR), for example, have typically been associated with higher levels of externalizing behaviors (Fairchild et al., 2008; Kariyawasam et al., 2002; Moss et al., 1995; Pajer et al., 2001; Popma et al., 2007; Ruttle et al., 2011; Shirtcliff, Granger, Booth, & Johnson, 2005), while both low and high levels of morning cortisol and CAR have been associated with internalizing symptoms (Dietrich et al., 2013; Nelemans et al., 2013). Testosterone, low levels of which have been associated with adult depression (Giltay et al., 2012), may also play a role in child psychopathology, although the literature on the relationship between child symptomatology and testosterone has been somewhat mixed. Mundy et al. (2015), for example, reported that higher testosterone was associated with peer relationship problems, emotional problems, and total overall difficulties in 8-9 year old boys, and less prosocial behavior in same-aged girls. Other investigations, however, have reported null or opposing associations between testosterone and symptom scores (i.e., lower testosterone associated with more problem behaviors; Granger et al., 2003; Klauser et al., 2015; Murray et al., 2016; Nottelmann et al., 1987; Shirtcliff, Zahn-Waxler, Klimes-Dougan, & Slattery, 2007).

Rather than focusing exclusively on the direct relationship between hormones and child symptoms, studies are increasingly investigating moderating variables that influence these relationships. Schuler et al. (2017), for example, reported that the relationship between diurnal cortisol and depressive symptoms was moderated by stressful life events, such that adolescent girls with blunted CAR experienced more symptoms of depression only when exposed to high levels of stress. Similarly, the combination of increased cortisol reactivity and higher levels of family stress has been associated with higher levels of internalizing symptoms (von Klitzing et al., 2012) and greater externalizing symptoms (although this effect was limited to boys; Hastings et al., 2011). Barrios, Bufferd, Klein, & Dougherty (2017) also reported that cortisol reactivity at age 3 interacted with parental hostility to prospectively predict increases in internalizing and externalizing symptoms between ages 3 and 6.

With regard to testosterone, Fang et al. (2009) examined associations between serum testosterone and delinquent behaviors in 11-14 year olds, and found that testosterone was associated with fewer delinquent behaviors in girls, but a greater number of these behaviors in boys. A similar pattern of results emerged when considering family cohesion as a moderator – specifically, higher testosterone was associated with more delinquent behaviors in boys with low family cohesion, but higher testosterone was associated with fewer delinquent behaviors in girls with low family cohesion. Booth, Johnson, Granger, Crouter, & McHale (2003) measured salivary testosterone in a sample of 6-18 year old youth, and reported that parent-child relationship quality significantly moderated the relationship between testosterone and problem behavior, although the effect differed by sex. Specifically, boys experiencing low quality relationships with their parents demonstrated a significant positive association between testosterone and behavior problems, while those with high relationship quality did not show this effect; in girls, low parental relationship quality was associated with a negative relationship between testosterone and problem behavior. An interaction between testosterone and parent-child relationships was also observed for depression – in both sexes, lower testosterone levels were associated with more child depressive symptoms only in the presence of low parent-child relationship quality.

Another potential moderator of hormone – symptom associations in children is parental depression. Parental depression is a robust risk factor for a broad range of internalizing and externalizing psychopathology (Barker, Jaffee, Uher, & Maughan, 2011; Goodman et al., 2011; Klein, Lewinsohn, Rohde, Seeley, & Olino, 2005; Weissman et al., 2016), and has been implicated in hormone dysregulation in offspring (Dougherty et al., 2009, 2013; Foland-Ross et al., 2014; Halligan, Herbert, Goodyer, & Murray, 2004; LeMoult, Ordaz, Kircanski, Singh, & Gotlib, 2015; Vreeburg et al., 2010). It is possible, therefore, that parental depression may moderate the effects of cortisol and testosterone on children’s internalizing and externalizing symptoms.

To date, however, no studies have explored interactions between parental depression and testosterone on child symptoms, and few have examined whether parental depression moderates the effect of cortisol on children’s mental health problems (e.g., Badenes et al., 2011; Essex et al., 2011; Halligan, Herbert, Goodyer, & Murray, 2007; Laurent et al., 2013). Considering a parent’s lifetime history of depression, rather than simply depression occurring during their children’s lives, is warranted. Children of asymptomatic parents who experienced depression prior to their birth are still at higher risk for developing depression themselves than children of whose parents do not have a history of depression (Mars et al., 2015). Along with genetic risk, this may be due to epigenetic processes influenced by physiological scarring (e.g., through hormonal dysregulation that is passed on to children) or practical and psychological sequalae associated with a parents’ history of depression (such as lower financial security or maladaptive coping styles). Furthermore, child hormone levels could be a protective factor in the intergenerational transmission of depression; children who are genetically vulnerable to depression may be protected by more adaptive hormone functioning during middle childhood.

Most investigations that have explored these relationships have relied on parents’ self-reported depression symptom scores rather than clinical diagnoses, and only focused on maternal depression without considering paternal depression or depression in multiple parents. The current study, therefore, sought to address these gaps in the literature by testing these effects in a large, community-based sample of 9-year-old children, who are only at the beginning of the pubertal transition and below the period of greatest risk for affective disorders. While rates of internalizing disorders are low in this age range, knowing which factors confer vulnerability or resilience during this relatively well period in middle childhood could offer great insights into factors that may be implicated in psychiatric illness in adolescence. Based on previous studies in this area, we hypothesized that children’s hormone levels would be significantly associated with symptoms only in the presence of parental depression. Specifically, we hypothesized that increased CAR and greater total cortisol output would be associated with higher internalizing symptoms among children whose parents have a history of depression, while lower CAR and overall cortisol would be associated with greater externalizing symptoms. Given the mixed findings in the literature, we also hypothesized that testosterone levels would be associated with child internalizing and externalizing symptoms only among children whose parents have a history of depression, but did not hypothesize a specific direction for this effect. Furthermore, given the historical emphasis on children of mothers with a history of depression (as opposed to fathers or two parents with a history of depression), and research suggesting that there may be meaningful differences between these groups (Connell & Goodman, 2002; Klein et al., 2005; Lieb, Isensee, Höfler, Pfister, & Wittchen, 2002), we also investigated the moderating role of different patterns of parental depression (i.e., two parents with a history of depression versus mother only, father only, or no parents with a history of depression). Finally, in light of past findings of sex differences moderating of hormone-symptom relationships (e.g., Booth et al., 2003; Fang et al., 2009) we examined whether these effects differed by sex.

Method

Participants

Participants were 389 9-year-old children from a larger study of temperament and risk for psychopathology (Klein & Finsaas, 2017). The sample was recruited when children were 3 years old using commercial mailing lists of families within a 20-mile radius of the university. 559 children entered the study, and another 50 minority families were recruited 3 years later to increase the diversity of the sample. The age 9 assessment was completed by 490 of the 609 families (80.5%). The analysis sample was drawn from the families who completed saliva collection (n=419; 85.5% of the age 9 sample). After applying exclusion criteria (see below), the final sample consisted of 389 participants. The final sample was 9.27 years old (range = 8.27 - 11.73 years, SD = 0.44), 53% male (n = 206), 89.2% Caucasian, and 11.6% Hispanic. 56.7% of participants’ mothers and 44.1% of fathers had completed a 4-year college degree.

Excluded children (including those excluded due to lack of participation in the age 9 wave, lack of saliva collection, saliva exclusion for conditions listed below, or other missing data; n = 220) did not differ from the final sample of children included in the analyses on age, sex, race/ethnicity, pubertal development, Child Behavior Checklist (CBCL) internalizing or externalizing symptoms, parental education, or parental depression.

Procedure

Information about lifetime parental psychopathology was collected at study entry and updated at the age 9 visit. Children’s symptoms and pubertal development were assessed at the age 9 lab visit, and children’s saliva was collected at home following the age 9 visit. Parents were instructed how to conduct the at-home saliva collection during the in-person study visit, and were subsequently contacted by study staff to answer any questions and coordinate sample pick-up.

Measures

Hormone collection and assay.

Children’s saliva was collected via passive drool immediately upon waking, 30 minutes after waking, and 30 minutes before bed on three consecutive weekdays, resulting in nine saliva samples per participant. Cortisol was assayed from all nine samples, while testosterone was assayed only from the samples taken 30 minutes after waking. Participants were instructed to freeze saliva samples immediately after collection until a member of the study staff retrieved the samples from the participants’ homes. The samples were then stored at −20°C until they were transported on dry ice to the Biochemistry Laboratory at the University of Trier in Trier, Germany for analysis. All samples were assayed in duplicate. Cortisol was assayed using a time-resolved fluorescence immunoassay with flourometric end-point detection (DELFIA). The intra-assay coefficient of variation for cortisol was 5.4, while the inter-assay coefficient of variation was 9.8. Cortisol data outliers (values greater than 3 standard deviations above the mean) were excluded from analyses (n=13 samples). After excluding unusable samples (see below), CAR (the difference between the 30-minute and waking samples) and total daily cortisol (area under the curve with respect to ground; AUCg) were calculated. CAR and AUCg were then averaged across available days.

Testosterone was assayed from the same aliquot and at the same lab as cortisol, using commercially available enzyme immunoassays specifically designed for use with saliva according to the manufacturer's recommended protocol (Salimetrics, State College, PA). The intra-assay and inter-assay coefficients of variation for testosterone was 6.7 and 9.0, respectively. A natural log transformation was applied to the testosterone data to reduce skew, and all analyses used transformed testosterone values that were averaged across three days.

Sample exclusion.

First, samples that were not frozen in a home freezer or that melted in transit to the university were excluded, as sample accuracy may be compromised following a freeze-thaw cycle. Second, any saliva sample that was collected more than 15 (cortisol) or 30 (testosterone) minutes after the intended time (as indicated by a participant-completed diary) was excluded in order to account for the hormones’ diurnal patterns. Third, samples were excluded if the child was taking an oral or inhaled corticosteroid, antipsychotic, or methyphenidate – extended release (Concerta) during sample collection, as these medications have been shown to affect hormone levels in children and adolescents (Granger et al., 2012). Following sample exclusion, of the 419 children who completed home saliva collection at age 9, 389 had at least one useable testosterone sample, 309 children had sufficient data to calculate CAR (i.e., useable waking and 30-minute post-waking samples on the same day), and 295 had sufficient data to calculate AUCg (i.e., useable waking, 30-minute post-waking, and evening samples on the same day). There were no significant differences between those children for whom CAR and AUCg could be calculated and those for whom these data were missing with regard to age, sex, race/ethnicity, pubertal development, CBCL internalizing or externalizing symptoms, parental education, or parental depression.

Parental depression.

The Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV (SCID; First, Gibbon, Spitzer, & Williams, 1996) was conducted with biological mothers and fathers at the age 3 assessment, and again at the age 9 assessment to cover the period since the initial assessment. When biological parents were not available to be interviewed, the other parent provided family history information for the missing parent (n = 13 fathers). For the current study, lifetime diagnoses of Major Depressive Disorder (MDD) and Dysthymic Disorder (DD) were coded as “present” if they were reported at either assessment. SCID or family history data were available for 388 mothers and 386 fathers in the analysis sample. 147 (37.9%) mothers and 77 (19.9%) fathers had a history of depression; of these, approximately half of mothers (48%, n=70) and a third of fathers (30%, n=23) reported experiencing depression during their child’s lifetime. Interrater reliability for depressive disorders was kappa = 0.93 at age 3, and kappa = 0.91 for the age 9 follow-up interview.

Children’s internalizing and externalizing symptoms.

The Child Behavior Checklist (CBCL/4-18; Achenbach, 1991) is a 113-item parent-report measure that assesses children’s behavioral and emotional problems, and was completed by mothers at the age 9 assessment. The CBCL includes higher order internalizing and externalizing factors. In this sample, Cronbach’s αs were 0.86 and 0.88 for the CBCL internalizing and externalizing factors, respectively. Approximately 9% (n=19) of girls’ and 6% (n=14) of boys’ internalizing scores fell in the clinical range, while 6% (n=12) of girls’ and 7% (n=17) of boys’ externalizing scores fell in the clinical range, consistent with other investigations of nonclinical samples with similarly aged children (Lengua et al., 2001).

Pubertal development.

The Pubertal Development Scale (PDS; Petersen, Crockett, Richards, & Boxer, 1988) was administered to mothers at the age 9 assessment. The PDS assesses pubertal development using five items. Items for both boys and girls include growth of body hair, skin changes (especially pimples), and growth in height, while items for boys only include voice deepening and growth of facial hair, and items for girls only include breast development and menstruation. Mothers rated each item on a scale from 1 (not yet started) to 4 (seems complete). A single sum score of the PDS items was used in the current analyses; the average sum score for girls was 7.57 (out of a possible 20), while for boys the average sum score was 6.53. Using Shirtcliff, Dahl, & Pollak’s (2009) coding algorithm, this translates to Tanner scores of approximately 1.71 (SD=0.61) for girls and 1.38 (SD=0.44) for boys, suggesting that most of the current sample was in the earliest stages of visible pubertal development.

Statistical analyses

First, we used bivariate correlations and t-tests to test associations between parental depression, child internalizing and externalizing symptoms, and CAR, AUCg, and testosterone. A four-level categorical “parental history of depression” variable was created, which consisted of having two parents with a history of depression, a mother with a history of depression and a never-depressed father, a father with a history of depression and a never-depressed mother, or no parents with a history of depression. In multiple linear regression models, dummy-coded parental history of depression and hormone levels (CAR, AUCg, or testosterone) were entered as independent variables while child internalizing and externalizing symptoms were explored as outcome variables (in separate models). Child sex, age at assessment, race, pubertal development, and time of waking were included as covariates. PROCESS version 3 (Hayes, 2018) was utilized to test interactions between parental depression and hormones in relating to children’s symptom scores. Interactions between child sex and hormones, exclusive of parental depression, were also explored, as well as three-way interactions between child sex, hormones, and parental depression. A Bonferroni correction was applied to control for multiple comparisons; results were considered statistically significant if they yielded p-values of less than .01.

Results

Tables 1 and 2 provide descriptive statistics, measures of association, and bivariate correlations for study variables of interest. Briefly, demographic variables such as age, race, and sex did not differ by parent depression status, nor did PDS score or hormone levels. Children who had two parents with a history of depression, however, had the highest scores on the CBCL-I and CBCL-E, followed by children with a mother with a history of depression alone, a father with a history of depression alone, and no parents with a history of depression. Furthermore, lower child testosterone, but not cortisol AUCg or CAR, were significantly associated with higher CBCL-E scores.

Table 1.

Descriptive Statistics and Tests of Association with Parental Depression Status

| Measure | No Parental Depression (n=202) M (SD) or n (%) |

Maternal Depression only (n=110) M (SD) or n (%) |

Paternal Depression only (n=40) M (SD) or n (%) |

Both Parents Depressed (n=37) M (SD) or n (%) |

Statistic |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 9.27 (0.45) | 9.29 (0.49) | 9.27 (0.31) | 9.25 (0.37) | F = 0.06 |

| Sex (% male) | 114 (56) | 54 (49) | 20 (50) | 22 (52) | χ2 = 2.06 |

| Race (% white) | 183 (91) | 99 (90) | 35 (88) | 35 (83) | χ2 = 3.13 |

| PDS | 1.51 (0.52) | 1.55 (0.62) | 1.55 (0.39) | 1.65 (0.65) | F = 0.65 |

| CAR (nmol/l) | 2.44 (3.58) | 1.59 (3.47) | 1.91 (4.34) | 1.52 (3.05) | F = 1.28 |

| AUCg (nmol/l) | 72.78 (27.81) | 69.40 (27.69) | 76.21 (30.32) | 69.60 (25.59) | F = 0.55 |

| Testosterone (pg/ml) | 3.29 (0.46) | 3.24 (0.48) | 3.30 (0.44) | 3.22 (0.47) | F = 0.39 |

| CBCL-I | 3.01 (3.56)a | 5.42 (5.93)b | 4.08 (4.15) | 5.69 (5.24)b | F = 7.86*** |

| CBCL-E | 3.69 (4.74)a | 5.19 (5.06)b | 4.08 (4.26) | 6.71 (7.24)b | F = 4.58** |

Note. PDS = Pubertal Development Scale (Shirtcliff et al. [2009] Tanner conversion score); CAR = cortisol awakening response; AUCg = area under the curve with respect to ground; CBCL-I = Child Behavior Checklist – Internalizing Factor; CBCL-E = Child Behavior Checklist – Externalizing Factor.

p<.05,

p<.01,

p<.001

Means with differing subscripts within rows are significantly different at the p <.01 value based on Fisher’s LSD post hoc paired comparisons.

Table 2.

Bivariate correlations among study variables of interest

| Testosterone (pg/ml) |

CAR (nmol/l) |

AUCg (nmol/l) |

CBCL-I | CBCL-E | PDS | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Testosterone | --- | .21*** | .37*** | −.06 | −.14** | .26*** |

| CAR | --- | .68*** | .01 | −.07 | −.004 | |

| AUCg | --- | −.04 | −.13t | .02 | ||

| CBCL-I | --- | .57*** | .05 | |||

| CBCL-E | --- | −.01 | ||||

| PDS | --- |

Note. CAR = cortisol awakening response; AUCg = area under the curve with respect to ground; CBCL-I = Child Behavior Checklist – Internalizing Factor; CBCL-E = Child Behavior Checklist – Externalizing Factor; PDS = Pubertal Development Scale.

p<.05,

p<.01,

p<.001

Next, multiple linear regression analyses were conducted to examine associations between parental depression, hormones, and their interactions with child symptom scores.

Testosterone.

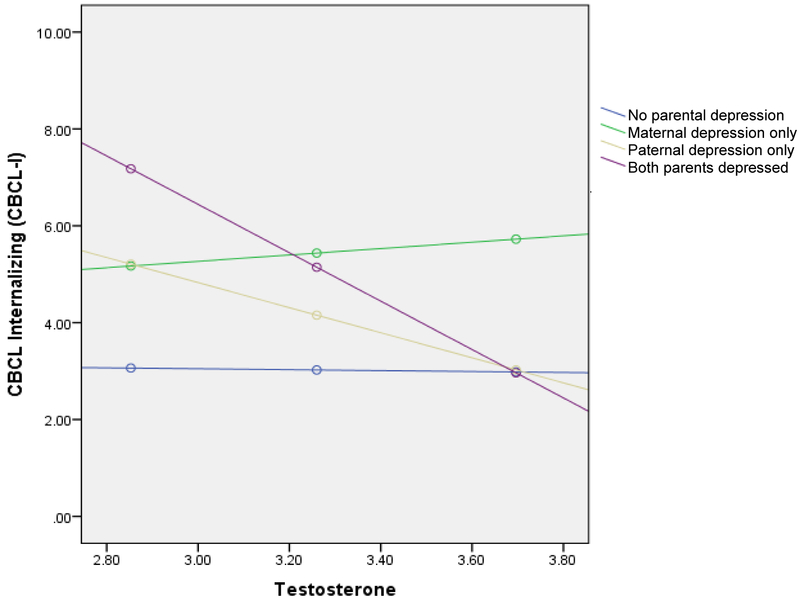

Having two parents with a history of depression was associated with significantly higher child CBCL-I scores than children with one or no parents with a history of depression, B = 18.21, SE = 5.85, p <.01 (Table 3). However, this effect was qualified by a significant interaction with child testosterone levels, B = −4.90, SE = 1.79, p <.01. Specifically, the test of simple slopes indicated that testosterone was negatively associated with CBCL-I scores for children with two parents with a history of depression (B = −5.00, SE = 1.62, p <.01), but not children with one or no parents with a history of depression (all ps >.05; Figure 1). When considering child CBCL-E scores (Table 3 and Figure 1), having two parents with a history of depression was again associated with higher CBCL-E scores than children with one or no parents with a history of depression (B = 19.28, SE = 6.51, p <.01); an interaction between testosterone and externalizing symptoms was reduced to non-significance after the application of a Bonferroni correction, however. Three-way interactions between sex, parental depression, and testosterone levels did not yield significant effects.

Table 3.

Hierarchical linear regression models testing the associations between parental depression, testosterone, and internalizing and externalizing symptoms

| B | SE | |

|---|---|---|

| Outcome = CBCL-I | ||

| Age at assessment | −.004 | .01 |

| Sex | −.47 | .50 |

| Race (white/non-white) | −.05 | .77 |

| PDS | −.04 | .48 |

| Waking time | −.06 | .31 |

| Testosterone | −.12 | .72 |

| Maternal depression only1 | −.56 | 3.90 |

| Paternal depression only1 | 10.22 | 6.07 |

| Both parents depressed1 | 18.21** | 5.85 |

| Testosterone × maternal depression | .92 | 1.19 |

| Testosterone × paternal depression | −2.83 | 1.83 |

| Testosterone × both parents depressed | −4.90** | 1.79 |

| Outcome = CBCL-E | ||

| Age at assessment | .004 | .01 |

| Sex | .28 | .56 |

| Race (white/non-white) | .46 | .86 |

| PDS | −.05 | .52 |

| Waking time | −.53 | .34 |

| Testosterone | −1.20 | .80 |

| Maternal depression only1 | −1.20 | 4.35 |

| Paternal depression only1 | 2.71 | 6.77 |

| Both parents depressed1 | 19.28** | 6.51 |

| Testosterone × maternal depression only | .84 | 1.32 |

| Testosterone × paternal depression only | −.68 | 2.04 |

| Testosterone × both parents depressed | −4.99t | 1.99 |

Note. CBCL-I = Child Behavior Checklist – Internalizing Factor; PDS = Pubertal Development Scale (Shirtcliff et al. Tanner conversion score); CBCL-E = Child Behavior Checklist – Externalizing Factor.

p<.05,

p<.01,

p<.001

Versus no parental depression reference category

Figure 1.

Interaction between testosterone and having two parents with a history of depression on CBCL-I scores

CAR.

Having two parents with a history of depression was associated with higher internalizing scores than children with one or no parents with a history of depression, B = 2.53, SE =.96, p <.01 (Table 4). The interaction between maternal depression and CAR was significantly associated with CBCL-I scores, B =.43, SE =.16, p <.01; the test of simple slopes revealed that CAR was positively associated with CBCL-I scores for children with a mother having a history of depression (B = .35, SE = .14, p <.01), but not children with a father who had experienced depression only, or two or no parents with a history of depression (all ps >.01; Figure 2). Having two parents with a history of depression was again significantly associated with higher CBCL-E scores than children with one or no parents with a history of depression, B = 5.20, SE = 1.21, p <.001, but interactions between maternal depression and CAR, as well as between two parents with a history of depression and CAR, were reduced to non-significance after the application of a Bonferroni correction (Table 4). Three-way interactions between sex, parental depression, and CAR did not yield significant effects.

Table 4.

Hierarchical linear regression models testing the associations between parental depression, cortisol awakening response, and internalizing and externalizing symptoms

| B | SE | |

|---|---|---|

| Outcome = CBCL-I | ||

| Age at assessment | −.01 | .01 |

| Sex | −.001 | .51 |

| Race (white/non-white) | .73 | .80 |

| PDS | .32 | .47 |

| Waking time | −.13 | .33 |

| CAR | −.08 | .09 |

| Maternal depression only1 | 1.36 | .64 |

| Paternal depression only1 | .32 | 1.91 |

| Both parents depressed1 | 2.53** | .96 |

| CAR × maternal depression only | .43** | .16 |

| CAR × paternal depression only | −.11 | .20 |

| CAR × both parents depressed | .31 | .26 |

| Outcome = CBCL-E | ||

| Age at assessment | .001 | .01 |

| Sex | .73 | .62 |

| Race (white/non-white) | .13 | .97 |

| PDS | −.34 | .56 |

| Waking time | −.54 | .40 |

| CAR | −.12 | .11 |

| Maternal depression only1 | .80 | .77 |

| Paternal depression only1 | .23 | 1.11 |

| Both parents depressed1 | 5.70*** | 1.17 |

| CAR × maternal depression only | .43t | .20 |

| CAR × paternal depression only | −.05 | .24 |

| CAR × both parents depressed | −.76t | .34 |

Note. CBCL-I = Child Behavior Checklist – Internalizing Factor; PDS = Pubertal Development Scale (Shirtcliff et al. Tanner conversion score); CAR = cortisol awakening response; CBCL-E = Child Behavior Checklist – Externalizing Factor.

p<.05,

p<.01,

p<.001

Versus no parental depression reference category

Figure 2.

Interaction between CAR and maternal depression on CBCL-I scores

AUCg.

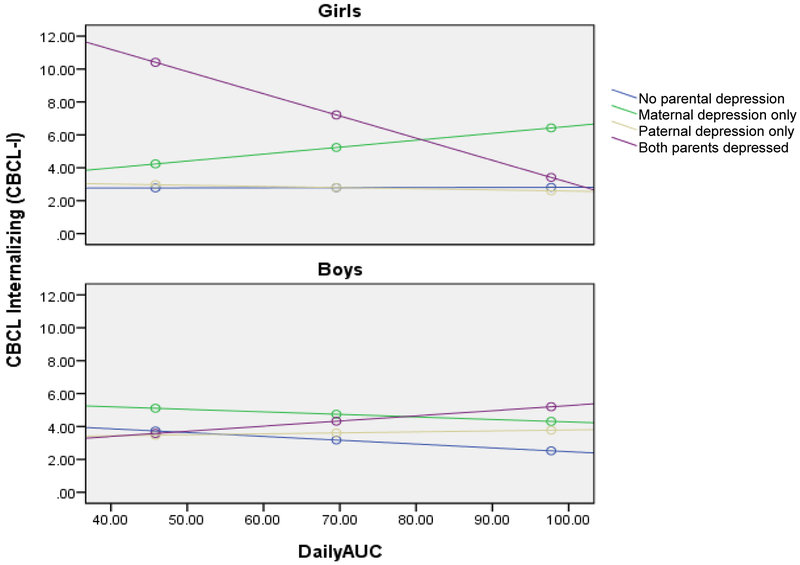

Again, having two parents with a history of depression was associated with higher CBCL-I scores than children with one or no parents with a history of depression, B = 13.88, SE = 3.77, p <.001 (Table 5). However, this was qualified by significant interactions between having two parents with depression and child sex (B = −18.50, SE = 5.14, p <.001) and having two parents with depression and child AUCg (B = −.14, SE = .05, p <.01). Moreover, these effects were further qualified by a significant three-way interaction between depression in two parents, child sex, and AUCg, B = .23, SE = .07, p <.001. Specifically, the test of simple slopes indicated that having two parents with a history of depression along with a lower AUCg was associated with higher CBCL-I scores than children with one or no parents with a history of depression, but only for girls, B = −.13, SE = .05, p <.01 (Figure 3).

Table 5.

Hierarchical linear regression models testing the associations between parental depression, cortisol area under the curve, and internalizing and externalizing symptoms

| B | SE | |

|---|---|---|

| Outcome = CBCL-I | ||

| Age at assessment | −.02 | .01 |

| Sex | 1.99 | 1.91 |

| Race (white/non-white) | .47 | .84 |

| PDS | .21 | .49 |

| Waking time | −.27 | .35 |

| AUCg | −.001 | .02 |

| Maternal depression only1 | −.68 | 2.52 |

| Paternal depression only1 | .30 | 3.51 |

| Both parents depressed1 | 13.88*** | 3.77 |

| AUCg × sex | −.02 | .02 |

| AUCg × maternal depression only | .04 | .03 |

| AUCg × paternal depression only | −.01 | .04 |

| AUCg × both parents depressed | −.14** | .05 |

| Sex × maternal depression only | 1.65 | 3.27 |

| Sex × paternal depression only | −1.57 | 4.86 |

| Sex × both parents depressed | −18.50*** | 5.14 |

| AUCg × sex × maternal depression only | −.03 | .04 |

| AUCg × sex × paternal depression only | .04 | .06 |

| AUCg × sex × both parents depressed | .23*** | .07 |

| Outcome = CBCL-E | ||

| Age at assessment | −.002 | .01 |

| Sex | .58 | .62 |

| Race (white/non-white) | −.03 | .98 |

| PDS | −.83 | .57 |

| Waking time | −.86 | .40 |

| AUCg | −.02 | .01 |

| Maternal depression only1 | −1.63 | 1.87 |

| Paternal depression only1 | .90 | 2.80 |

| Both parents depressed1 | 15.75*** | 3.00 |

| AUCg × maternal depression only | .05 | .03 |

| AUCg × paternal depression only | −.01 | .03 |

| AUCg × both parents depressed | .16*** | .04 |

Note. CBCL-I = Child Behavior Checklist – Internalizing Factor; PDS = Pubertal Development Scale (Shirtcliff et al. Tanner conversion score); AUCg = area under the curve with respect to ground; CBCL-E = Child Behavior Checklist – Externalizing Factor.

p<.05,

p<.01,

p<.001

Versus no parental depression reference category

Figure 3.

Interaction between cortisol AUCg and having two depressed parents on CBCL-I scores for girls and boys

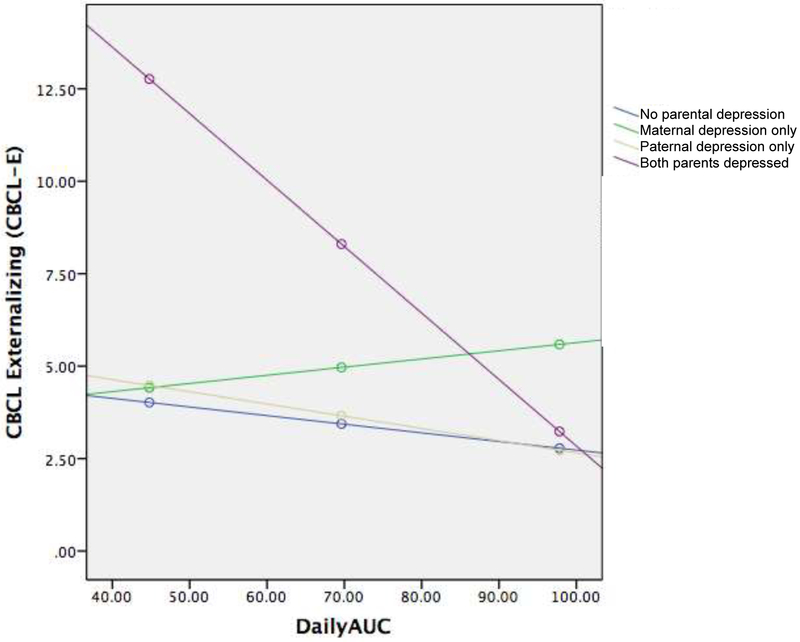

Having two parents with a history of depression was also significantly associated with higher CBCL-E scores than children with one or no parents with a history of depression, B = 15.75, SE = 3.00, p <.001 (Table 5). Furthermore, having two parents with depression significantly interacted with AUCg (B = .16, SE = .04, p <.001). Specifically, the test of simple slopes indicated that having two parents with a history of depression and lower AUCg was associated with higher CBCL-E scores than children with one or no parents with a history of depression, B = −.18, SE = .04, p <.001 (Figure 4). Three-way interactions between sex, parental depression, and AUCg did not yield significant effects when predicting CBCL-E scores.

Figure 4.

Interaction between AUCg and two parents with a history of depression on CBCL-E scores

Discussion

The current study investigated the relationships between salivary cortisol and testosterone, parental depression, and child internalizing and externalizing symptoms. Consistent with previous research, parental history of depression was associated with elevated internalizing and externalizing symptoms in offspring. Interestingly, children with only fathers with a history of depression did not demonstrate significantly elevated symptoms and having two parents with depression did not have a greater direct impact on symptoms than having only a mother with depression. In bivariate analyses, lower testosterone levels were significantly associated with externalizing scores, but not internalizing scores. Importantly, no significant associations were found between parental depression and child cortisol or testosterone levels, suggesting that parental depression is not simply impacting child symptoms through its association with hormones. Rather, significant interactions between parental depression (depression in either mothers or both parents) suggest that low levels of testosterone and lower cortisol reactivity/output may be associated with greater symptoms only in the presence of parental depression.

While previous investigations have explored the relationships between hormone levels and child symptoms, results have often been mixed. The current findings suggest one possible reason for these mixed findings; specifically, children with certain hormone patterns may only exhibit symptoms under certain conditions, such as when their parents have a history of depression. Children with low testosterone and two parents with a history of depression, for example, had the highest levels of internalizing symptoms in the current sample, a finding that is consistent with related previous research (Booth, Johnson, Granger, Crouter, & McHale, 2003). Unlike some previous investigations (Booth et al., 2003; Fang et al., 2009), however, we did not find that child sex impacted this relationship involving testosterone. This may be due to the early developmental stage of our participants, however.

A more complex story emerged when considering cortisol. An elevated CAR was associated with higher internalizing symptoms, but only among children who only had a mother with a history of depression. The first effect can be considered in light of previous evidence, albeit somewhat mixed, for a relationship between heightened CAR and internalizing symptoms (Dietrich et al., 2013; Nelemans et al., 2013). When considering cortisol output throughout the day, however, lower AUCg was associated with both internalizing and externalizing symptoms among children who had two parents with a history of depression, although the former effect was limited to girls only. It may be, therefore, that having two parents with a history of depression is an even more robust risk factor for externalizing psychopathology than having one or no parents with depression, and that lower cortisol output throughout the day (AUCg) amplifies this effect. Given the significant positive association between internalizing and externalizing symptoms, these similar results with regards to AUCg are likely suggesting a similar causal phenomenon. Alternately, higher cortisol output may be protective for children having two parents with a history of depression. For example, although having two parents with depression is a robust risk factor for psychopathology in children, greater total cortisol output may buffer children from this risk.

These seemingly discrepant results may be best viewed in terms of a child’s cumulative stress exposure. Previous research has shown that both elevated and blunted cortisol patterns are associated with psychopathology (Dietrich et al., 2013; Nelemans et al., 2013; Ruttle et al., 2011; Shirtcliff, Granger, Booth, & Johnson, 2005). When only one parent has experienced depression, which may have negative impacts on a family system even when the parent is not symptomatic, a second parent without a history of depression is often there to buffer the effects of this stress. This may lead to a pattern of heightened stress responding in children, as they are not in a chronically stressful system, but one that ebbs and flows unpredictably. When both parents have experienced depression and its sequalae, however, no one is available to buffer the stress, leading to an environment marked by chronic stress and subsequent reduced cortisol responsiveness. Dietz, Jennings, Kelley, & Marshal (2009), for example, showed that maternal depression predicted child internalizing and externalizing symptoms, but only in the presence of paternal psychopathology. Having two parents with depression could lead to fewer available resources (as indicated by lower educational attainment and financial stability; Kessler, 2012), less adaptive parenting practices (Lovejoy, Graczyk, O’Hare, & Neuman, 2000; Wilson & Durbin, 2010), and poorer communication and relationship quality between parents with depression (Sharabi, Delaney, & Knobloch, 2016). The significant impact of having a mother only, but not father only, with depression may be due to the age of our sample. Specifically, the impact of paternal depression appears to be greatest during adolescence, when fathers often begin to take a more active role in childrearing (Klein et al., 2005; Natsuaki et al., 2014; Reeb et al., 2015). When reconciling these discrepant findings, it is also important to note that CAR and AUCg index different physiological processes and may therefore be associated with different psychological outcomes for children of different sexes (e.g., LeMoult, Ordaz, Kircanski, Singh, & Gotlib, 2015). Overall, the problem may not be specifically high or low levels of cortisol, but simply a dysregulated stress response system.

The current study had many strengths, including the use of a large community sample with a restricted age range, thus limiting the impact of variability in development, and repeated direct interview assessments of lifetime depression in both mothers and fathers. Limitations include the cross-sectional nature of the current analyses, as both child symptoms and hormone levels were assessed at the same time, which precludes drawing inferences about the direction of the effects; as well as the limited racial, ethnic, and geographical diversity of the sample. Relatedly, maternal report of child symptoms was utilized in the current analyses; considering previous findings that mothers with depression often rate their children as also having more symptoms of depression (Fergusson et al., 1993), using maternal report allows for the potential that maternal depression may have influenced their reports of children’s symptoms. Only a minority of mothers with a history of depression (7/147, 4.7%) reported current depression or depression in the month prior to their assessments, however, so it is unlikely that this influence was significant. Furthermore, as the age of this sample limited pubertal influences on cortisol and testosterone, different patterns of hormone response may be associated with elevated symptom scores in an older sample (Hankin, Badanes, Abela, & Watamura, 2010). Finally, levels of internalizing and externalizing symptoms in the current sample were relatively low, and few children had clinically significant levels of symptoms. It will be important to continue to follow this sample to see if the current effects influence future symptoms and functioning, especially as risk for internalizing disorders increases dramatically during adolescence.

Taken together, the current results suggest that children who have two parents with a history of depression as well as dysregulated hormone functioning may be most at risk for heightened internalizing and externalizing symptoms. The current results also suggest that certain hormone patterns may be protective in light of parental depression. Furthermore, this work highlights the importance of studying mother-father dyads when investigating the impact of parental depression on children. Future research following these children into adolescence and adulthood will clarify whether the effect of the relationship between parental depression and hormones influences changes in child symptoms, and whether the effects persist beyond childhood.

Highlights.

Parental depression is a risk factor for child psychopathology.

Hormone levels impact symptoms, especially in children whose parents have a history of depression.

Girls whose parents have a history of depression may be especially vulnerable to hormone dysregulation.

Acknowledgement:

This work was supported by National Institute of Mental Health Grant RO1 MH069942 to DNK.

Role of Funding Source

This work was supported by National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH) Grant RO1 MH069942 to DNK. The content of the current manuscript, however, is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NIMH. The study sponsor did not have any role in study design, data collection or analysis, or writing of this manuscript.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest

Drs. Black and Klein, and Mr. Goldstein, declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Author Statement

Dr. Black wrote the first draft of the manuscript and completed the statistical analyses. Mr. Goldstein completed data management and reviewed the final manuscript. Dr. Klein designed the study, supervised data collection, and reviewed all versions of the manuscript. All authors contributed to and approved the final manuscript.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Achenbach TM (1991). Integrative guide for the 1991 CBCL/4-18, YSR, and TRF profiles. University of Vermont; Burlington: Department of Psychiatry. [Google Scholar]

- Achenbach TM, & Rescorla L (2001). Manual for ASEBA School-Age Forms & Profiles. University of Vermont, Burlington, VT.: Research Center for Children, Youth, & Families. [Google Scholar]

- Adam EK, Doane LD, Zinbarg RE, Mineka S, Craske MG, & Griffith JW (2010). Prospective prediction of major depressive disorder from cortisol awakening responses in adolescence. Psychoneuroendocrinology, 35(6), 921–931. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Badenes LS, Watamura SE, & Hankin BL (2011). Hypocortisolism as a potential marker of allostatic load in children: Associations with family risk and internalizing disorders. Development and Psychopathology, 23(3), 881–896. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barker ED, Jaffee SR, Uher R, & Maughan B (2011). The contribution of prenatal and postnatal maternal anxiety and depression to child maladjustment. Depression and Anxiety, 28, 696–702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barrios CS, Bufferd SJ, Klein DN, & Dougherty LR (2017). The interaction between parenting and children's cortisol reactivity at age 3 predicts increases in children's internalizing and externalizing symptoms at age 6. Development and Psychopathology, 29(4), 1319–1331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Booth A, Johnson DR, Granger DA, Crouter AC, & McHale S (2003). Testosterone and child and adolescent adjustment: The moderating role of parent-child relationships. Developmental Psychology, 39(1), 85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clowtis LM, Kang DH, Padhye NS, Rozmus C, & Barratt MS (2016). Biobehavioral factors in child health outcomes: The roles of maternal stress, maternal–child engagement, salivary cortisol, and salivary testosterone. Nursing Research, 65(5), 340–351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Connell AM, & Goodman SH (2002). The association between psychopathology in fathers versus mothers and children's internalizing and externalizing behavior problems: A meta-analysis. Psychological Bulletin, 128, 746–773. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Danese A, & McEwen BS (2012). Adverse childhood experiences, allostasis, allostatic load, and age-related disease. Physiology & Behavior, 106, 29–39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dietrich A, Ormel J, Buitelaar JK, Verhulst FC, Hoekstra PJ, & Hartman CA (2013). Cortisol in the morning and dimensions of anxiety, depression, and aggression in children from a general population and clinic-referred cohort: An integrated analysis. The TRAILS study. Psychoneuroendocrinology, 38(8), 1281–1298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dietz LJ, Jennings KD, Kelley SA, & Marshal M (2009). Maternal depression, paternal psychopathology, and toddlers' behavior problems. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology, 38, 48–61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dougherty LR, Klein DN, Olino TM, Dyson M, & Rose S (2009). Increased waking salivary cortisol and depression risk in preschoolers: The role of maternal history of melancholic depression and early child temperament. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 50(12), 1495–1503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dougherty LR, Smith VC, Olino TM, Dyson MW, Bufferd SJ, Rose SA, & Klein DN (2013). Maternal psychopathology and early child temperament predict young children’s salivary cortisol 3 years later. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 41 (4), 531–542. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Essex MJ, Shirtcliff EA, Burk LR, Ruttle PL, Klein MH, Slattery MJ, … Armstrong JM (2011). Influence of early life stress on later hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis functioning and its covariation with mental health symptoms: A study of the allostatic process from childhood into adolescence. Development and Psychopathology, 23(4), 1039–1058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fairchild G, van Goozen SH, Stollery SJ, Brown J, Gardiner J, Herbert J, & Goodyer IM (2008). Cortisol diurnal rhythm and stress reactivity in male adolescents with early - onset or adolescence-onset conduct disorder. Biological Psychiatry, 64(7), 599–606. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fang CY, Egleston BL, Brown KM, Lavigne JV, Stevens VJ, Barton BA, … & Dorgan JF (2009). Family cohesion moderates the relation between free testosterone and delinquent behaviors in adolescent boys and girls. Journal of Adolescent Health, 44(6), 590–597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fergusson DM, Lynskey MT, & Horwood LJ (1993). The effect of maternal depression on maternal ratings of child behavior. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 21(3), 245–269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- First MB, Gibbon M, Spitzer RF, & Williams JBW (1996). User’s guide for the structured clinical interview for DSM-IV axis I Disorders—Research version. New York: Biometrics Research Department, New York State Psychiatric Institute. [Google Scholar]

- Foland-Ross LC, Kircanski K, & Gotlib IH (2014). Coping with having a depressed mother: The role of stress and coping in hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal axis dysfunction in girls at familial risk for major depression. Development and Psychopathology, 26 (4pt2), 1401–1409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giltay EJ, Enter D, Zitman FG, Penninx BW, van Pelt J, Spinhoven P, & Roelofs K (2012). Salivary testosterone: Associations with depression, anxiety disorders, and antidepressant use in a large cohort study. Journal of Psychosomatic Research, 72(3), 205–213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodman SH, Rouse MH, Connell AM, Broth MR, Hall CM, & Heyward D (2011). Maternal depression and child psychopathology: A meta-analytic review. Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review, 14, 1–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodyer IM, Tamplin A, Herbert J, & Altham PME (2000). Recent life events, cortisol, dehydroepiandrosterone and the onset of major depression in high-risk adolescents. The British Journal of Psychiatry, 777(6), 499–504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Granger DA, Fortunato CK, Beltzer EK, Virag M, Bright MA, & Out D (2012). Focus on methodology: salivary bioscience and research on adolescence: an integrated perspective. Journal of Adolescence, 35(4), 1081–1095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Granger DA, Shirtcliff EA, Zahn-Waxler C, Usher B, Klimes-Dougan B, & Hastings P (2003). Salivary testosterone diurnal variation and psychopathology in adolescent males and females: Individual differences and developmental effects. Development and Psychopathology, 15(2), 431–449. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halligan SL, Herbert J, Goodyer I, & Murray L (2004). Exposure to postnatal depression predicts elevated cortisol in adolescent offspring. Biological Psychiatry, 55(4), 376–381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halligan SL, Herbert J, Goodyer I, & Murray L (2007). Disturbances in morning cortisol secretion in association with maternal postnatal depression predict subsequent depressive symptomatology in adolescents. Biological Psychiatry, 62, 40–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hankin BL, Badanes LS, Abela JR, & Watamura SE (2010). Hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal axis dysregulation in dysphoric children and adolescents: Cortisol reactivity to psychosocial stress from preschool through middle adolescence. Biological Psychiatry, 68(5), 484–490. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris TO, Borsanyi S, Messari S, Stanford K, Brown GW, Cleary SE, … & Herbert J (2000). Morning cortisol as a risk factor for subsequent major depressive disorder in adult women. The British Journal of Psychiatry, 177(6), 505–510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hastings PD, Shirtcliff EA, Klimes-Dougan B, Allison AL, Derose L, Kendziora KT, … & Zahn-Waxler C (2011). Allostasis and the development of internalizing and externalizing problems: Changing relations with physiological systems across adolescence. Development and Psychopathology, 23(4), 1149–1165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayes AF (2017). Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis: A regression-based approach. Guilford Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Inslicht SS, Otte C, McCaslin SE, Apfel BA, Henn-Haase C, Metzler T, … & Marmar CR (2011). Cortisol awakening response prospectively predicts peritraumatic and acute stress reactions in police officers. Biological Psychiatry, 70(11), 1055–1062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kariyawasam SH, Zaw F, & Handley SL (2002). Reduced salivary cortisol in children with comorbid attention deficit hyperactivity disorder and oppositional defiant disorder. Neuroendocrinology Letters, 23(1), 45–48. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler RC (2012). The costs of depression. Psychiatric Clinics, 35(1), 1–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler RC, Berglund P, Demler O, Jin R, Koretz D, Merikangas KR, … & Wang PS (2003). The epidemiology of major depressive disorder: Results from the National Comorbidity Survey Replication (NCS-R). JAMA, 289(23), 3095–3105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klein DN, & Finsaas MC (2017). The Stony Brook Temperament Study: Early antecedents and pathways to emotional disorders. Child Development Perspectives, 11, 257–263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klein DN, Goldstein BL, & Finsaas M (2017). Depressive disorders In Beauchaine TP and Hinshaw SP (Eds.), Child and Adolescent Psychopathology, 3rd ed. (pp. 610–641). Hoboken, New Jersey: John Wiley & Sons. [Google Scholar]

- Klein DN, Lewinsohn PM, Rohde P, Seeley JR, & Olino TM (2005). Psychopathology in the adolescent and young adult offspring of a community sample of mothers and fathers with major depression. Psychological Medicine, 35, 353–365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klauser P, Whittle S, Simmons JG, Byrne ML, Mundy LK, Patton GC, … & Allen NB (2015). Reduced frontal white matter volume in children with early onset of adrenarche. Psychoneuroendocrinology, 52, 111–118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koss KJ, & Gunnar MR (2018). Annual Research Review: Early adversity, the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenocortical axis, and child psychopathology. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 59(4), 327–346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laurent HK, Leve LD, Neiderhiser JM, Natsuaki MN, Shaw DS, Fisher PA, … & Reiss D (2013). Effects of parental depressive symptoms on child adjustment moderated by HPA: Within- and between-family risk. Child Development, 84(2), 528–542. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lengua LJ, Sadowski CA, Friedrich WN, & Fisher J (2001). Rationally and empirically derived dimensions of children's symptomatology: Expert ratings and confirmatory factor analyses of the CBCL. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 69(4), 683–698. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LeMoult J, Ordaz SJ, Kircanski K, Singh MK, & Gotlib IH (2015). Predicting first onset of depression in young girls: Interaction of diurnal cortisol and negative life events. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 124(4), 850. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewinsohn PM, Rohde P, Klein DN, & Seeley JR (1999). Natural course of adolescent major depressive disorder: I. Continuity into young adulthood. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 35(1), 56–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lieb R, Isensee B, Höfler M, Pfister H, & Wittchen HU (2002). Parental major depression and the risk of depression and other mental disorders in offspring: A prospective-longitudinal community study. Archives of General Psychiatry, 59(4), 365–374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lovejoy MC, Graczyk PA, O'Hare E, & Neuman G (2000). Maternal depression and parenting behavior: A meta-analytic review. Clinical Psychology Review, 20(5), 561–592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mars B, Collishaw S, Hammerton G, Rice F, Harold GT, Smith D, … & Thapar AK (2015). Longitudinal symptom course in adults with recurrent depression: Impact on impairment and risk of psychopathology in offspring. Journal of Affective Disorders, 182, 32–38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merikangas KR, Nakamura EF, & Kessler RC (2009). Epidemiology of mental disorders in children and adolescents. Dialogues in Clinical Neuroscience, 11(1), 7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moss HB, Vanyukov MM, & Martin CS (1995). Salivary cortisol responses and the risk for substance abuse in prepubertal boys. Biological Psychiatry, 38(8), 547–555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mundy LK, Romaniuk H, Canterford L, Hearps S, Viner RM, Bayer JK, … & Patton GC (2015). Adrenarche and the emotional and behavioral problems of late childhood. Journal of Adolescent Health, 57(6), 608–616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murray CR, Simmons JG, Allen NB, Byrne ML, Mundy LK, Seal ML, … & Whittle S (2016). Associations between dehydroepiandrosterone (DHEA) levels, pituitary volume, and social anxiety in children. Psychoneuroendocrinology, 64, 31–39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Natsuaki MN, Shaw DS, Neiderhiser JM, Ganiban JM, Harold GT, Reiss D, & Leve LD (2014). Raised by depressed parents: Is it an environmental risk? Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review, 17(4), 357–367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nelemans SA, Hale WW, Branje SJ, van Lier PA, Jansen LM, Platje E, … & Meeus WH (2014). Persistent heightened cortisol awakening response and adolescent internalizing symptoms: A 3-year longitudinal community study. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 42(5), 767–777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nottelmann ED, Susman EJ, Inoff-Germain G, Cutler GB, Loriaux DL, & Chrousos GP (1987). Developmental processes in early adolescence: Relationships between adolescent adjustment problems and chronologic age, pubertal stage, and puberty-related serum hormone levels. The Journal of Pediatrics, 110(3), 473–480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pajer K, Gardner W, Rubin RT, Perel J, & Neal S (2001). Decreased cortisol levels in adolescent girls with conduct disorder. Archives of General Psychiatry, 58(3), 297–302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petersen AC, Crockett L, Richards M, & Boxer A (1988). A self-report measure of pubertal status: Reliability, validity, and initial norms. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 17(2), 117–133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Popma A, Vermeiren R, Geluk CA, Rinne T, van den Brink W, Knol DL, … & Doreleijers TA (2007). Cortisol moderates the relationship between testosterone and aggression in delinquent male adolescents. Biological Psychiatry, 61(3), 405–411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reeb BT, Wu EY, Martin MJ, Gelardi KL, Chan SYS, & Conger KJ (2015). Long-term effects of fathers' depressed mood on youth internalizing symptoms in early adulthood. Journal of Research on Adolescence, 25(1), 151–162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Renk K, Oliveros A, Roddenberry A, Klein J, Sieger K, Roberts R, & Phares V (2007). The relationship between maternal and paternal psychological symptoms and ratings of adolescent functioning. Journal of Adolescence, 30(3), 467–485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruttle PL, Shirtcliff EA, Serbin LA, Fisher DBD, Stack DM, & Schwartzman AE (2011). Disentangling psychobiological mechanisms underlying internalizing and externalizing behaviors in youth: Longitudinal and concurrent associations with cortisol. Hormones and Behavior, 59(1), 123–132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schuler KL, Ruggero CJ, Goldstein BL, Perlman G, Klein DN, & Kotov R (2017). Diurnal cortisol interacts with stressful events to prospectively predict depressive symptoms in adolescent girls. Journal of Adolescent Health, 61(6), 767–772. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharabi LL, Delaney AL, & Knobloch LK (2016). In their own words: How clinical depression affects romantic relationships. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 33(4), 421–448. [Google Scholar]

- Shirtcliff EA, Dahl RE, & Pollak SD (2009). Pubertal development: Correspondence between hormonal and physical development. Child Development, 80(2), 327–337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shirtcliff EA, & Essex MJ (2008). Concurrent and longitudinal associations of basal and diurnal cortisol with mental health symptoms in early adolescence. Developmental Psychobiology, 50(7), 690–703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shirtcliff EA, Granger DA, Booth A, & Johnson D (2005). Low salivary cortisol levels and externalizing behavior problems in youth. Development and Psychopathology, 17(1), 167–184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shirtcliff E, Zahn-Waxler C, Klimes-Dougan B, & Slattery M (2007). Salivary dehydroepiandrosterone responsiveness to social challenge in adolescents with internalizing problems. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 48(6), 580–591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- von Klitzing K, Perren S, Klein AM, Stadelmann S, White LO, Groeben M, … & Hatzinger M (2012). The interaction of social risk factors and HPA axis dysregulation in predicting emotional symptoms of five-and six-year-old children. Journal of Psychiatric Research, 46(3), 290–297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vreeburg SA, Hartman CA, Hoogendijk WJ, van Dyck R, Zitman FG, Ormel J, & Penninx BW (2010). Parental history of depression or anxiety and the cortisol awakening response. The British Journal of Psychiatry, 197(3), 180–185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weissman MM, Wickramaratne P, Gameroff MJ, Warner V, Pilowsky D, Kohad RG, … & Talati A (2016). Offspring of depressed parents: 30 years later. American Journal of Psychiatry, 773(10), 1024–1032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson S, & Durbin CE (2010). Effects of paternal depression on fathers' parenting behaviors: A meta-analytic review. Clinical Psychology Review, 30(2), 167–180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]