Abstract

Objective:

Evaluate the cost-effectiveness of prolonged (35-day) and standard (14-day) duration anticoagulation therapy following total knee arthroplasty (TKA).

Methods:

Using Markov modeling, we assessed clinical and economic outcomes of 14-day and 35-day anticoagulation therapy following TKA with rivaroxaban, low molecular weight heparin (LMWH), fondaparinux, warfarin, and aspirin. Incidence of complications of TKA and anticoagulation – DVT, PE, prosthetic joint infection (PJI), and bleeding – were derived from published literature. Daily costs ranged from $1 (aspirin) to $43 (fondaparinux). Primary outcomes included quality-adjusted life years (QALYs), direct medical costs, and incremental cost-effectiveness ratios (ICERs) at one-year post-TKA. The preferred regimen was the regimen with highest QALYs maintaining an ICER below the willingness-to-pay threshold ($100,000/QALY). We conducted probabilistic sensitivity analyses, varying complication incidence and anticoagulation efficacy, to evaluate the impact of parameter uncertainty on model results.

Results:

Aspirin resulted in the highest cumulative incidence of DVT and PE, while prolonged fondaparinux led to the largest reduction in DVT incidence (15% reduction compared to no prophylaxis). Despite differential bleeding rates (ranging from 3% to 6%), all strategies had similar incidence of PJI (1–2%). Prolonged rivaroxaban was the least costly strategy ($3,300 one year post-TKA) and the preferred regimen in the base case. In sensitivity analyses, prolonged rivaroxaban and warfarin had similar likelihoods of being cost-effective.

Conclusions:

Extending post-operative anticoagulation to 35 days increases QALYs compared to standard 14-day prophylaxis. Prolonged rivaroxaban and prolonged warfarin are most likely to be cost-effective post-TKA; the costs of fondaparinux and LMWH precluded their being preferred strategies.

Total knee arthroplasty (TKA) patients are at risk of deep vein thrombosis (DVT) and pulmonary embolism (PE). Approximately 60% of patients without prophylaxis develop DVT.(1, 2) While many of these thromboses are isolated to calf veins, resolving without complications, nearly 12% of post-TKA patients without preventative treatment present with evidence of proximal thromboses early in the postoperative course.(2, 3) Proximal DVTs are more likely to be clinically significant and can spontaneously break free resulting in PE, which contributes to 100,000 deaths annually and increases the risk of recurrent DVT.(4–6)

To reduce the risk of DVT and PE, TKA patients are prescribed anticoagulation, as recommended by American College of Chest Physicians (ACCP) and American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons (AAOS).(7, 8) While both professional societies suggest chemoprophylaxis, the guidelines are unclear regarding the specific agent and appropriate duration. ACCP recommends therapy for a minimum of 10–14 days and up to 35 days, whereas AAOS leaves the duration of postoperative anticoagulation to physician discretion.10,11 The absence of guidance on duration and regimen selection has resulted in high variability in the postoperative care of TKA patients, with various anticoagulants employed from 7 days to 6 weeks.(7) Further, the daily cost of anticoagulation regimens varies from $1 to $43.(9–12)

Some research has suggested that longer anticoagulation can substantially reduce the risk of DVT and PE;(11, 13) however, in the absence of definitive recommendations, physicians are left weighing the risks of DVT and PE against those of anticoagulation, including hemorrhage of gastrointestinal (GI) and central nervous system (CNS) sites, as well as a higher likelihood of prosthetic joint infection (PJI).(14) Prior cost-effectiveness analyses (CEA) evaluating anticoagulation therapy after joint arthroplasty have compared only two agents and few have considered the duration of therapy.(15, 16) One analysis evaluating prolonged (42 day) versus standard (12 day) treatment with enoxaparin in total hip arthroplasty (THA) or TKA patients suggested that prolonged therapy was cost-effective in THA patients.(17) However, this study did not account for increased cumulative bleeding risk for prolonged therapy, thereby minimizing the potential adverse effects of extending the duration of anticoagulation.

Given the lack of guidance regarding the specific agent and duration of prophylaxis and the wide range in cost of anticoagulants, we sought to weigh the clinical benefits of prolonged (35-day) and standard duration (14-day) anticoagulation therapy, including reduced likelihood of DVT and PE, against the increased risks, including bleeding and PJI, taking into consideration the regimen costs, of commonly utilized post-TKA anticoagulants.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Analytic Overview

We conducted a formal cost-effectiveness analysis to evaluate 10 plausible clinical strategies: 14-day (standard) and 35-day (prolonged) postoperative anticoagulation therapy with rivaroxaban, low molecular weight heparin (LMWH), warfarin, fondaparinux, and aspirin in patients undergoing TKA. The primary outcomes were quality-adjusted life years (QALYs) and costs at one-year post-TKA. While TKA and anticoagulation complications most commonly present within the first few post-operative months, the associated decrease in quality of life can persist for the first post-operative year; we therefore chose a one-year time horizon to capture “important differences in consequences, both intended and unintended,” as recommended by the Panel of Cost-Effectiveness in Health and Medicine.(18) We report quality-adjusted life days (QALDs) in each health state, which represents the number of days and proportion of the first postoperative spent without complications and in each complication state. The cost-effectiveness of each strategy was expressed in terms of incremental cost-effectiveness ratios (ICERs), defined as the increase in cost per increase in QALY. We adopted a societal perspective, and assumed a willingness-to-pay (WTP) threshold of $100,000/QALY;(19, 20) strategies with ICERs below WTP were considered cost-effective. Strategies that increased cost while reducing QALYs were deemed dominated. As there is no standard of care (SOC) for post-TKA anticoagulation, we identified comparator strategies by considering the most commonly used clinically-relevant DVT chemoprophylactic regimens for TKA patients; we therefore conducted cost-effectiveness analyses with two strategies as the reference case: standard duration warfarin and LMWH.

Model Structure

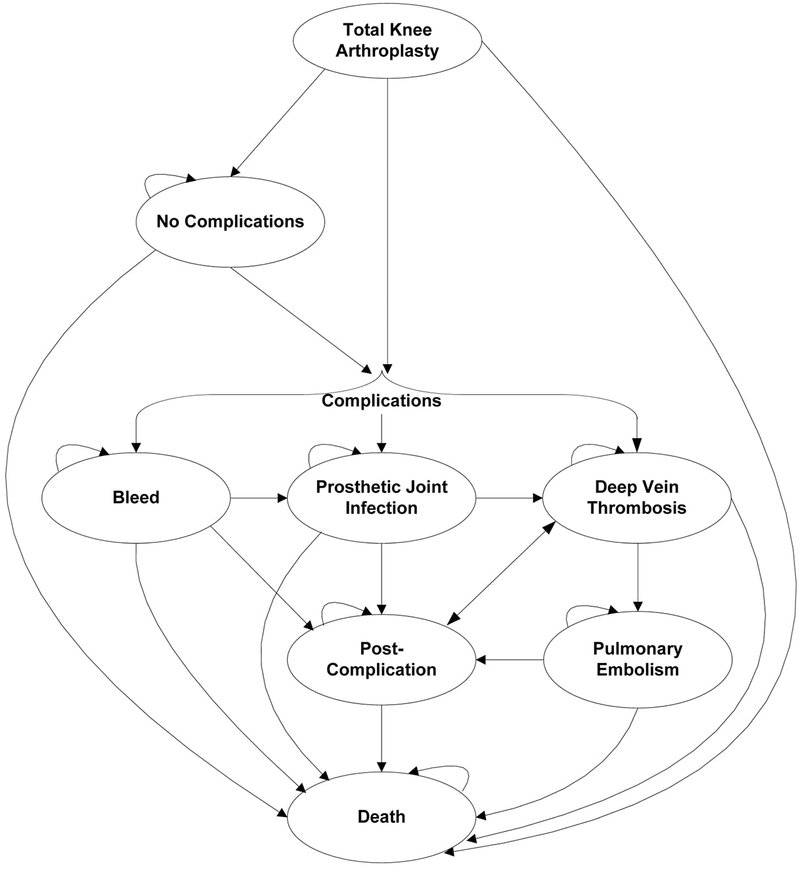

We constructed a probabilistic, Markov, state-transition computer simulation model (TreeAge Pro© 2017). Following TKA, subjects transitioned between the following major health states (Figure 1): proximal DVT, PE, bleed, PJI, or no postoperative complications. We focus on proximal (versus distal) DVT, as they are more likely to manifest clinically.(21–24) Each health state is associated with a unique health-related quality of life (QoL) and cost. Death can occur at any state. The model follows each simulated subject from the time of TKA (model entry) to death or the end of the first postoperative year, whichever occurs first.

Figure 1.

This figure depicts the model structure used to assess anticoagulation strategies after total knee arthroplasty (TKA). Following TKA, subjects can experience deep vein thrombosis, prosthetic joint infection, or bleeding or can proceed with no complications. Those who experience a complication and do not die enter a post-complication state, which are specific to the complication experienced (post-DVT, post-PE, post-bleed, and post-PJI). Subjects are at continued risk of deep vein thrombosis in the post-complication state. Death can occur at any point.

Subjects developing proximal DVT are stratified by symptomatic status (symptomatic or asymptomatic), each carrying a risk of propagation to PE. Those who do not progress to PE within 30 days are considered resolved and at risk of recurrent DVT. Those who develop PE experience an increased risk of death for 30 days following PE diagnosis; subjects who do not die from PE enter a post-PE state where they are at risk of recurrent DVT.

Major bleeds are categorized as operative or non-operative site bleeds. Operative site bleeds increase the likelihood of PJI, while non-operative site bleeds (GI or CNS) increase mortality. We assumed the increased risks of PJI and death following operative and non-operative site bleeds persisted for 30 days.

Input Parameters

Transition Probabilities

Background Mortality

Background mortality in each state represents the likelihood of death unrelated to TKA or anticoagulation complications. We derived age-stratified background mortality from Centers for Disease Control 2013 Life Tables.(25)

Complications

Complications of TKA and anticoagulation included proximal DVT, PE, major bleed, and PJI. The likelihood of each complication was dependent on days post-TKA.

Deep Vein Thrombosis and Pulmonary Embolism

The underlying incidence of proximal DVT in the immediate postoperative period (days 0–14 post-TKA) was estimated from a published medical record review of 517 TKA patients (638 total TKAs) with average age 66 years; 78% were female, and the majority (85%) were white. Within this study population, indications for TKA were primarily degenerative arthritis (73%) and rheumatoid arthritis (15%). DVT was established via venography in the first postoperative week and was defined as an intraluminal filling defect within the calf, popliteal, or thigh veins. Of the 49 patients without anticoagulation (62 TKAs), 36 had evidence of thrombosis in the calf, and 7 had evidence of thrombosis in the popliteal or thigh veins. We defined proximal DVT as thromboses within the popliteal or thigh veins, resulting in 11.29% incidence of proximal DVT following TKA without preoperative anticoagulation.(3) Evidence suggests that the increased risk of DVT following orthopedic surgery is highest in the immediate postoperative period and may persist for up to 3 months.(13, 26) Based on published literature, we derived a likelihood of DVT in the extended post-TKA period (days 15–90) of 6.41%.(3, 7) At 3 months, we assumed no increased risk of DVT as a direct result of TKA and employed age-based DVT risks for the remainder of the year (0.25% annually).(27)

Based on published evidence, we estimated 68.75% of proximal DVTs were symptomatic.(28) Patients with DVT were at risk of developing PE. As symptomatic patients are more likely to present to care and receive treatment, the likelihood of progression to PE from symptomatic DVT is lower than asymptomatic DVT. We derived the likelihood of propagation to PE from asymptomatic and symptomatic DVT as 50% and 6.25%.(21, 28)

We incorporated risk of recurrent DVT for those who experienced resolution of the primary DVT or PE. Several patient factors are associated with recurrence of DVT(6, 24, 29–31) – post-surgical patients have an increased risk of primary DVT but a lower risk of DVT recurrence (HR = 0.36(30)); whereas those with primary DVT who progress to PE have a nearly 3-fold(6) increased risk of recurrent DVT. Using data from Prandoni et al., we derived a 1-year cumulative incidence of recurrent DVT among those with resolved primary DVT of 17.68%.(30) The likelihood of recurrent DVT in those with resolved PE was increased by a relative risk (RR) of 2.77.(6)

The likelihood of death from PE was time-dependent, with greater risk immediately following diagnosis. Data from Smith et al. suggest 3.00% in-hospital and 7.70% 30-day mortality risk for PE patients receiving early medical intervention.(32) The median hospital stay for PE patients was 4.6 days; we therefore applied 3.00% mortality for the first 5 days following PE diagnosis.

Bleeding Events

Risk of post-TKA bleeding without anticoagulation was derived from ACCP data: 1.50% for early (0–14 days) bleeds and 0.50% for late bleeds (15+ days).(7) Bleeds were differentiated by location (operative or non-operative site). Based on published data, we assumed 68.7% of bleeds would occur at the operative site, and the remaining 31.3% at non-operative sites, including GI and CNS.(33) Operative site bleeds increased the risk of PJI development (RR = 9.8(14)), while non-operative site bleeds carried a case-fatality of 9.26%,(34) which was applied for 90 days following the hemorrhagic event.

Prosthetic Joint Infection

We estimated the annual incidence of PJI from a published medical record review of 1,214 primary TKA recipients with median age 72 years. The majority of patients were female (63%), and 59% were considered obese or morbidly obese. Ninety-two percent of patients underwent TKA due to osteoarthritis, 8% due to rheumatoid arthritis, and 1% due to osteonecrosis or trauma. There were 18 prosthetic infections identified within the first postoperative year, resulting in 1.48% annual incidence of PJI.(35) Based on a retrospective review of PJI in post-TKA patients, we assumed 28.87% of PJIs would occur in the first 3 months.(36) This led to a cumulative incidence of PJI of 0.43% in the first 3 months and 1.06% in the subsequent 9 months post-TKA. Mortality was derived using Nosocomial Infection National Surveillance Service, resulting in increased odds of death for deep infection patients compared to no infection post-TKA of 7.2.(37, 38) The increased mortality from PJI was applied for 120 days following diagnosis.

Regimen-Specific Anticoagulation Efficacy and Toxicity

We estimated the RR of complications using data from the National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE) guidelines on reducing venous thromboembolic events in hospitalized patients.(39) Using network meta-analysis of anticoagulation studies for TKA, NICE derived RRs of DVT and major bleeding events (Table 1), which were applied for 35 days for prolonged and 14 days for standard strategies.

Table 1.

Model Input Data

| Complication Characteristics | ||||||||

| Proximal DVT | PE | Bleeding | PJI | |||||

| Probability (no prophylaxis) | ||||||||

| Days 1–14 | 11.29% (5.49%)(3) | 1.50% (0.75%)(7) | 0.43% (0.22%)(35, 36) | |||||

| Days 15+ | 6.41% (3.26%) / 0.25% (0.12%)a (3, 7, 27) | 0.50% (0.25%)(7) | 1.06% (0.53%)(35, 36) | |||||

| Cost (9, 10, 12, 48–50) | $9,600 | $11,000 | $13,000d | $48,300 | ||||

| Utility | 0.661b (41) | 0.499 (41) | 0.573d (44, 48) | 0.44e (43) | ||||

| Mortality | 3.00%/7.70%c (32) | 9.26%d (34) | RR = 7.20(38) | |||||

| Treatment Characteristics | ||||||||

| Fondaparinux | Rivaroxaban | LMWH | Warfarin | Aspirin | ||||

| Daily Cost(9–12) | $43f | $8 | $37f | $6/$3g | $1 | |||

| RR DVT(39) | 0.08 (0.03) | 0.12 (0.04) | 0.20 (0.07) | 0.36 (0.12) | 0.62 (0.21) | |||

| RR Bleeding(39) | 2.21 (0.74) | 2.12 (0.71) | 1.23 (0.41) | 1.21 (0.40) | 1.0 (0.15) | |||

All costs presented in 2016 USD

– Days 15–90/days 91+

– Applied to symptomatic proximal DVT only

– Days post-PE diagnosis 1–5/6–30

– Applied to non-operative site bleed only

– Applied to acute PJI state; utility of post-PJI = 0.72

– Includes cost of injection administration ($20)

– Weeks 1/Weeks 2+, includes cost of monitoring

Abbreviations: DVT, deep vein thrombosis; PE, pulmonary embolism; PJI, prosthetic joint infection; LMWH, low molecular weight heparin

Quality of Life (QoL) Utilities

We assumed a QoL utility of 0.69 in the first 3 months following TKA for those without complications, reflecting the pain and functional limitation in the immediate recovery period. The utility of the post-TKA state with no complications was increased to 0.76 after 3 months.(40) Symptomatic proximal DVT, PE, non-operative site bleeds, and PJI carried reduced QoL utilities of 0.66, 0.49, 0.57, and 0.44 respectively, which were applied for the duration of the complication state (described above).(41–44) Those with asymptomatic proximal DVT or non-operative site bleeds, as well as those with resolved complications, acquired the same utility as those with no complications. Subjects with resolved PJI were assigned a lower post-PJI utility (0.72) due to the necessity of revision and associated recovery.(43)

Costs

Daily costs of anticoagulants were derived by converting Average Wholesale Prices (AWPs) from Red Book Online to Average Sales Prices (ASPs) by discounting brand name drugs by 26% and generic drugs by 68%.(45, 46) The resulting ASPs were weighted as 93% generic and 7% brand name, representing proportion of generic versus brand drugs prescribed in the US.(47) We included the cost of injection administration ($25), estimated from Medicare Reimbursement Schedules, for LMWH and fondaparinux.(10) Additionally, the cost of monitoring ($20/week), consisting of prothrombin time (PT/INR) and an established patient visit, was incorporated into the cost of warfarin treatment.(9–12) We assumed two monitoring sessions within the first week of therapy and weekly for all subsequent weeks.

Complication costs were derived from Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project 2014 and inflated to 2016 USD.(9, 12, 48) As PJI frequently requires revision surgery, the acute cost of PJI included the cost of revision TKA, estimated at $25,000.(9, 10, 12, 48–50) Final costs (2016 USD) were $9,600 for DVT, $11,000 for PE, $48,400 for PJI and $13,000 for non-operative site bleeds.

Sensitivity Analyses

We conducted a sensitivity analysis removing the cost of administration, to represent self-injection, of fondaparinux and LMWH. We performed probabilistic sensitivity analyses (PSA) incorporating the variability in efficacy of each anticoagulation agent (RR of DVT and bleeding) and baseline estimates of DVT, bleeding, and PJI incidences. Distributions used in PSA are presented in Appendix Table 1. Results of PSA are represented by a cost-effectiveness acceptability curve, which presents the proportion of 10,000 iterations for which each strategy was the preferred regimen over a range of WTP thresholds. We repeated all analyses modeling a cohort of obese patients with increased baseline risk of DVT; the results of these analyses are presented in the Appendix Table 2a and 2b.

Role of the Funding Source

The Rheumatology Research Foundation and NIH/NIAMS funded the study but had no role in its design, conduct, or reporting.

RESULTS

Aspirin (taken for either 14 or 35 days) was associated with the highest projected 1-year cumulative incidence of DVT and PE and the fewest bleeding events (Tables 2a and 2b). Prolonged rivaroxaban resulted in a 14% absolute reduction in proximal DVTs compared to no prophylaxis, and prolonged fondaparinux reduced proximal DVT incidence by an additional 1%. Prolonged rivaroxaban and fondaparinux led to bleeding rates of 6%. All strategies resulted in similar rates of PJI in the year following TKA.

Table 2.

Base Case Cost-Effectiveness Analysis

| Standard Duration Warfarin Standard of Care | |||||

| Strategy | Cost | QALY | ICER | DVT | Bleed |

| Prolonged Rivaroxaban | $3,279 | 0.733 | Cost Saving | 18.0% | 6.0% |

| Prolonged Warfarin | $3,291 | 0.732 | Cost Saving | 21.9% | 4.0% |

| Standard Rivaroxaban | $3,416 | 0.732 | Cost Saving | 22.8% | 5.4% |

| Standard Warfarin | $3,551 | 0.732 | Reference | 25.6% | 3.9% |

| Prolonged Aspirin | $3,689 | 0.731 | Dominated | 25.7% | 3.5% |

| Standard Aspirin | $3,777 | 0.731 | Dominated | 28.4% | 3.4% |

| No prophylaxis | $3,869 | 0.726 | Dominated | 32.1% | 3.3% |

| Standard LMWH | $3,898 | 0.732 | Dominated | 23.9% | 3.9% |

| Standard Fondaparinux | $3,932 | 0.732 | $977,100 | 22.3% | 5.6% |

| Prolonged LMWH | $4,375 | 0.733 | Dominated | 19.5% | 4.1% |

| Prolonged Fondaparinux | $4,529 | 0.733 | $1,085,600 | 17.3% | 6.2% |

| Standard Duration LMWH Standard of Care | |||||

| Strategy | Cost | QALY | ICER | DVT | Bleed |

| Prolonged Rivaroxaban | $3,279 | 0.733 | Cost Saving | 18.0% | 6.0% |

| Prolonged Warfarin | $3,291 | 0.732 | Cost Saving | 21.9% | 4.0% |

| Standard Rivaroxaban | $3,416 | 0.732 | Cost Saving | 22.8% | 5.4% |

| Standard Warfarin | $3,551 | 0.732 | Dominated | 25.6% | 3.9% |

| Prolonged Aspirin | $3,689 | 0.731 | Dominated | 25.7% | 3.5% |

| Standard Aspirin | $3,777 | 0.731 | Dominated | 28.4% | 3.4% |

| No prophylaxis | $3,869 | 0.726 | Dominated | 32.1% | 3.3% |

| Standard LMWH | $3,898 | 0.732 | Reference | 23.9% | 3.9% |

| Standard Fondaparinux | $3,932 | 0.732 | $243,500 | 22.3% | 5.6% |

| Prolonged LMWH | $4,375 | 0.733 | Dominated | 19.5% | 4.1% |

| Prolonged Fondaparinux | $4,529 | 0.733 | $1,085,600 | 17.3% | 6.2% |

A strategy that leads to greater cost without clinical benefit is deemed Dominated. DVT & bleeds presented as cumulative incidence. Standard strategies are 14 days, and prolonged strategies are 35 days.

Abbreviations: QALYs, quality-adjusted life years; ICER, incremental cost-effectiveness ratio; DVTs, deep vein thromboses; LMWH, low molecular weight heparin

Figure 2 depicts the number of QALDs and proportion of the year spent in each health state. All prolonged strategies were associated with ~267 QALDs at one year post-TKA; however, the distribution of the number QALDs varied between strategies. Prolonged rivaroxaban, fondaparinux, and LMWH resulted in an average 215 QALDs (~80%) without complications. Prolonged aspirin had the fewest QALDs without complications (201) and the largest proportion spent in the DVT state (18%). Strategies resulting in the fewest QALDs with DVT (prolonged fondaparinux and rivaroxaban) also resulted in the highest average QALDs with bleeds.

Figure 2.

The total quality-adjusted life days and proportion of the first post-operative year spent in each health state is depicted for each prolonged strategy. Abbreviations: DVT, deep vein thrombosis, PE, pulmonary embolism; PJI, prosthetic joint infection; LMWH, low molecular weight heparin.

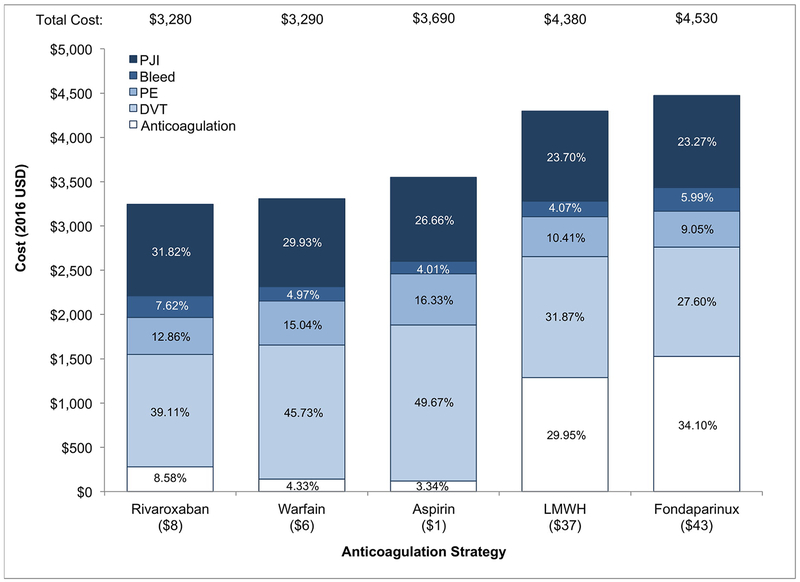

Prolonged rivaroxaban was the least costly strategy, accumulating $3,280 in one year post-TKA (Figure 3, Table 2). Anticoagulation cost was the largest contributor to overall cost for prolonged LMWH and fondaparinux, the most costly strategies (30% for LMWH, 34% for fondaparinux). In both standard and prolonged aspirin therapy, the cost of DVT treatment was the largest contributor to overall cost (50% for prolonged, 53% for standard). For all prolonged strategies, 1–2% of the cohort experienced a PJI and 4–6% a bleeding event, leading to an average per person annual cost of $1,000 and $200 on PJI and bleeds. Extending the duration of therapy saved an average of $300, $240, $170, $280, and $320 per person per year on DVT treatment for rivaroxaban, warfarin, aspirin, LMWH, and fondaparinux strategies, respectively. The cost saved from preventing DVT by prolonging therapy exceeded the additional cost of anticoagulation for rivaroxaban, warfarin, and aspirin, but not for LMWH or fondaparinux.

Figure 3.

The individual components of the annual cost for each prolonged strategy are shown. Anticoagulation includes the cost of the anticoagulant and any monitoring (warfarin) or administration (LMWH and fondaparinux), as appropriate. The cost of anticoagulation in the prolonged aspirin strategy is minimal and not indicated here. Abbreviations: DVT, deep vein thrombosis, PE, pulmonary embolism; PJI, prosthetic joint infection; LMWH, low molecular weight heparin.

Table 2a presents the base case cost-effectiveness analysis assuming SOC was standard duration warfarin and Table 2b assumes standard duration LMWH as SOC. All strategies increased QALYs compared to no prophylaxis. Assuming either standard duration warfarin or LMWH as SOC, both durations of fondaparinux increased cost with minimal increases in QALY, leading to ICERs over $200,000/QALY. Prolonged warfarin and both durations of rivaroxaban were cost saving in both reference cases. Prolonged rivaroxaban was the preferred strategy using either standard duration warfarin or LMWH as SOC.

The results of PSA are presented in Figure 4. Across all WTP thresholds, prolonged warfarin was the cost-effective strategy in ~40% of iterations. Prolonged rivaroxaban reached maximum likelihood of cost-effectiveness (34%) at WTP of $150,000/QALY. Prolonged aspirin was cost-effective in 15% of iterations across all WTP thresholds.

Figure 4.

This figure shows the proportion of iterations where a given strategy was the cost-effective option at various WTP thresholds. Strategies with probabilities of cost-effectiveness <5% are not shown. Abbreviations: WTP, willingness to pay; LMWH, low molecular weight heparin.

DISCUSSION

We built a probabilistic state-transition computer simulation model to weigh the benefits – reduction in DVT and PE – against the harms, including increased bleeding and PJI, of standard or prolonged duration therapy of five commonly prescribed anticoagulants following TKA. Our results show that extending the duration of therapy increases QALYs. In the base case, prolonged rivaroxaban was the preferred strategy; however, in sensitivity analyses, incorporating the uncertainty surrounding the efficacy of each anticoagulant, we found that prolonged rivaroxaban and warfarin were likely to be cost-effective in nearly equal proportions. The cost of LMWH and fondaparinux prohibited them from being cost-effective.

While minor differences may be seen between overall QALYs in the first post-operative year, all prolonged strategies increased the number no complication days in the first post-operative year compared to standard duration therapies, ranging from 10 QALDs for rivaroxaban, LMWH, and fondaparinux to 6 QALDs for aspirin. Additionally, the increase in post-operative bleeding events and PJIs were outweighed by the decrease in QALDs associated with DVT and PE for all prolonged strategies compared to their standard duration counterparts.

To our knowledge, this is the first CEA to compare across multiple anticoagulants at several durations post-TKA. Previous studies of anticoagulation therapy in TKA or THA recipients have focused on comparative analyses of two strategies or a single agent prescribed at different doses or durations.(15, 16) A CEA by Schousboe et al. concluded that, when compared to LMWH, aspirin was the preferred strategy in THA patients but the cost-effectiveness in TKA patients was dependent on age and DVT risk, with aspirin assuming a higher likelihood of cost-effectiveness in older patients without high DVT risk.(33) Another analysis evaluating aspirin and warfarin found that aspirin was the preferred strategy in THA patients of all ages, regardless of the rate of venous thromboembolism. In TKA patients, warfarin was the preferred strategy in patients with low risks of bleeding and high risk of venous thromboembolism.(51) The results of the base case analysis presented here contrast with those of Tabatabaee and Schousboe, with warfarin and LMWH leading to higher QALYs than aspirin. This difference could be explained by our use of a shorter time horizon, emphasizing the immediate QoL decrements of complications, notably DVT.

Few studies have formally assessed the clinical and economic outcomes associated with extending thromboprophylaxis in a TKA population. Haentjens and colleagues evaluated 12-day versus 42-day enoxaparin therapy following total joint arthroplasty and reported ICERs (2016 USD) of $8,900/QALY for THA and $83,200/QALY for TKA, for 42-day compared to 12-day therapy.(17) This analysis, however, assessed only enoxaparin and did not increase the risk of bleeding for extended therapy, potentially limiting the utility of the results.

There are important limitations to our analyses. We used the best currently available data to inform model inputs; however, data on the continued efficacy of anticoagulants in the extended prophylactic period were limited. We based our efficacy estimates on network meta-analyses combining trials of both THA and TKA patients, which may overestimate the efficacy. Based on network meta-analytic results, we assumed that aspirin did not increase the risk of bleeding; however, some studies have observed similar incidence of bleeding between aspirin and LMWH or warfarin. We addressed the uncertainty in this parameter in PSA and found the results robust to plausible ranges in bleeding risk while taking aspirin.

In conclusion, we found prolonged therapies to increase QALYs compared to standard duration therapies, supporting the extension of anticoagulation post-TKA. Prolonged prophylaxis with warfarin and rivaroxaban emerged as cost-effective strategies in this setting. As these two agents are comparable from a cost-effectiveness standpoint, patient preferences can help inform the choice of the appropriate postoperative anticoagulation strategy.

Supplementary Material

SIGNIFICANCE AND INNOVATIONS.

For all anticoagulants, prolonging the duration of post-operative prophylaxis to 35 days increases quality-adjusted life years (QALYs) compared to standard 14-day prophylaxis.

Prolonged therapy with warfarin and rivaroxaban are cost-effective strategies following total knee arthroplasty. The cost of fondaparinux and low molecular weight heparin precluded their cost-effectiveness.

As prolonged prophylaxis with rivaroxaban and warfarin are comparable from a cost-effectiveness standpoint, patient preferences regarding the higher incidence of bleeding with rivaroxaban versus the increased incidence of DVT with warfarin can help inform the choice of post-operative anticoagulation therapy.

Acknowledgments

Funding: This work was supported by the Rheumatology Research Foundation Medical Student Preceptorship and the National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases (NIH/NIAMS) K24AR057827.

Footnotes

Competing Interests: Dr. Katz is the President of the Osteoarthritis Research Society International. Drs. Katz and Losina are Deputy Editors for Biostatistics and Methodology for the Journal of Bone and Joint Surgery.

REFERENCES

- 1.Anderson FA, Jr., Spencer FA. Risk factors for venous thromboembolism. Circulation. 2003;107(23 Suppl 1):I9–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Brookenthal KR, Freedman KB, Lotke PA, Fitzgerald RH, Lonner JH. A meta-analysis of thromboembolic prophylaxis in total knee arthroplasty. The Journal of arthroplasty. 2001;16(3):293–300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Stulberg BN, Insall JN, Williams GW, Ghelman B. Deep-vein thrombosis following total knee replacement. An analysis of six hundred and thirty-eight arthroplasties. The Journal of bone and joint surgery American volume. 1984;66(2):194–201. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Goldhaber SZ, Visani L, De Rosa M. Acute pulmonary embolism: clinical outcomes in the International Cooperative Pulmonary Embolism Registry (ICOPER). Lancet. 1999;353(9162):1386–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Beckman MG, Hooper WC, Critchley SE, Ortel TL. Venous thromboembolism: a public health concern. American journal of preventive medicine. 2010;38(4 Suppl):S495–501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Eichinger S, Heinze G, Jandeck LM, Kyrle PA. Risk assessment of recurrence in patients with unprovoked deep vein thrombosis or pulmonary embolism: the Vienna prediction model. Circulation. 2010;121(14):1630–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Falck-Ytter Y, Francis CW, Johanson NA, Curley C, Dahl OE, Schulman S, et al. Prevention of VTE in orthopedic surgery patients: Antithrombotic Therapy and Prevention of Thrombosis, 9th ed: American College of Chest Physicians Evidence-Based Clinical Practice Guidelines. Chest. 2012;141(2 Suppl):e278S–e325S. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mont MA, Jacobs JJ, Boggio LN, Bozic KJ, Della Valle CJ, Goodman SB, et al. Preventing venous thromboembolic disease in patients undergoing elective hip and knee arthroplasty. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2011;19(12):768–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.National Health Expenditures: Personal Health Care Index. Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services; 2016.

- 10.Medicare Physician Fee Schedule. Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services; 2016.

- 11.Forster R, Stewart M. Anticoagulants (extended duration) for prevention of venous thromboembolism following total hip or knee replacement or hip fracture repair. The Cochrane database of systematic reviews. 2016;3:CD004179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Analysis USBoE. Personal Consumption Expenditure. Federeal Reserve Bank of St. Louis. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kearon C Duration of venous thromboembolism prophylaxis after surgery. Chest. 2003;124(6 Suppl):386S–92S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Galat DD, McGovern SC, Hanssen AD, Larson DR, Harrington JR, Clarke HD. Early return to surgery for evacuation of a postoperative hematoma after primary total knee arthroplasty. The Journal of bone and joint surgery American volume. 2008;90(11):2331–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kapoor A, Chuang W, Radhakrishnan N, Smith KJ, Berlowitz D, Segal JB, et al. Cost effectiveness of venous thromboembolism pharmacological prophylaxis in total hip and knee replacement: a systematic review. PharmacoEconomics. 2010;28(7):521–38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Brockbank J, Wolowacz S. Economic Evaluations of New Oral Anticoagulants for the Prevention of Venous Thromboembolism After Total Hip or Knee Replacement: A Systematic Review. PharmacoEconomics. 2017;35(5):517–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Haentjens P, De Groote K, Annemans L. Prolonged enoxaparin therapy to prevent venous thromboembolism after primary hip or knee replacement. A cost-utility analysis. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg. 2004;124(8):507–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Neumann PJ, Sanders GD, Russell LB, Siegel JE, Ganiats TG. Cost effectiveness in health and medicine. 2nd ed Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ubel PA, Hirth RA, Chernew ME, Fendrick AM. What is the price of life and why doesn’t it increase at the rate of inflation? Archives of internal medicine. 2003;163(14):1637–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ryen L, Svensson M. The Willingness to Pay for a Quality Adjusted Life Year: A Review of the Empirical Literature. Health economics. 2014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kearon C Natural history of venous thromboembolism. Circulation. 2003;107(23 Suppl 1):I22–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sule AA, Chin TJ, Handa P, Earnest A. Should symptomatic, isolated distal deep vein thrombosis be treated with anticoagulation? The International journal of angiology : official publication of the International College of Angiology, Inc. 2009;18(2):83–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Galanaud JP, Sevestre-Pietri MA, Bosson JL, Laroche JP, Righini M, Brisot D, et al. Comparative study on risk factors and early outcome of symptomatic distal versus proximal deep vein thrombosis: results from the OPTIMEV study. Thrombosis and haemostasis. 2009;102(3):493–500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hansson PO, Sorbo J, Eriksson H. Recurrent venous thromboembolism after deep vein thrombosis: incidence and risk factors. Archives of internal medicine. 2000;160(6):769–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Arias E, Heron M, Xu J. United States Life Tables, 2013 National Vital Statistics Report. Hyattsville, MD: US Department of Health and Human Services, National Center for Health Statistics; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Heit JA, O’Fallon WM, Petterson TM, Lohse CM, Silverstein MD, Mohr DN, et al. Relative impact of risk factors for deep vein thrombosis and pulmonary embolism: a population-based study. Archives of internal medicine. 2002;162(11):1245–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tsai AW, Cushman M, Rosamond WD, Heckbert SR, Polak JF, Folsom AR. Cardiovascular risk factors and venous thromboembolism incidence: the longitudinal investigation of thromboembolism etiology. Archives of internal medicine. 2002;162(10):1182–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Moser KM, LeMoine JR. Is embolic risk conditioned by location of deep venous thrombosis? Annals of internal medicine. 1981;94(4 pt 1):439–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kyrle PA, Rosendaal FR, Eichinger S. Risk assessment for recurrent venous thrombosis. Lancet. 2010;376(9757):2032–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Prandoni P, Lensing AW, Cogo A, Cuppini S, Villalta S, Carta M, et al. The long-term clinical course of acute deep venous thrombosis. Annals of internal medicine. 1996;125(1):1–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wallace G, Judge A, Prieto-Alhambra D, de Vries F, Arden NK, Cooper C. The effect of body mass index on the risk of post-operative complications during the 6 months following total hip replacement or total knee replacement surgery. Osteoarthritis and cartilage. 2014;22(7):918–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Smith SB, Geske JB, Maguire JM, Zane NA, Carter RE, Morgenthaler TI. Early anticoagulation is associated with reduced mortality for acute pulmonary embolism. Chest. 2010;137(6):1382–90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Schousboe JT, Brown GA. Cost-effectiveness of low-molecular-weight heparin compared with aspirin for prophylaxis against venous thromboembolism after total joint arthroplasty. The Journal of bone and joint surgery American volume. 2013;95(14):1256–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Linkins LA, Choi PT, Douketis JD. Clinical impact of bleeding in patients taking oral anticoagulant therapy for venous thromboembolism: a meta-analysis. Annals of internal medicine. 2003;139(11):893–900. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Dowsey MM, Choong PF. Obese diabetic patients are at substantial risk for deep infection after primary TKA. Clinical orthopaedics and related research. 2009;467(6):1577–81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Peersman G, Laskin R, Davis J, Peterson M. Infection in total knee replacement: a retrospective review of 6489 total knee replacements. Clinical orthopaedics and related research. 2001(392):15–23. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Service NINS. Protocol for Surveillance of Surgical Site Infection. Version 4 London: Health Protection Agency; 2008. 27 July 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Coello R, Charlett A, Wilson J, Ward V, Pearson A, Borriello P. Adverse impact of surgical site infections in English hospitals. The Journal of hospital infection. 2005;60(2):93–103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.(UK) NCGC-AaCC. Elective knee replacement. Venous Thromboembolism: Reducing the Risk of Venous Thromboembolism (Deep Vein Thrombosis and Pulmonary Embolism) in Patients Admitted to Hospital. London; 2010. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Losina E, Walensky RP, Kessler CL, Emrani PS, Reichmann WM, Wright EA, et al. Cost-effectiveness of total knee arthroplasty in the United States: patient risk and hospital volume. Archives of internal medicine. 2009;169(12):1113–21; discussion 21–2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Melnikow J, Birch S, Slee C, McCarthy TJ, Helms LJ, Kuppermann M. Tamoxifen for breast cancer risk reduction: impact of alternative approaches to quality-of-life adjustment on cost-effectiveness analysis. Medical care. 2008;46(9):946–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Bamber L, Muston D, McLeod E, Guillermin A, Lowin J, Patel R. Cost-effectiveness analysis of treatment of venous thromboembolism with rivaroxaban compared with combined low molecular weight heparin/vitamin K antagonist. Thrombosis journal. 2015;13:20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Skaar DD, Park T, Swiontkowski MF, Kuntz KM. Cost-effectiveness of antibiotic prophylaxis for dental patients with prosthetic joints: Comparisons of antibiotic regimens for patients with total hip arthroplasty. Journal of the American Dental Association. 2015;146(11):830–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.You JH, Tsui KK, Wong RS, Cheng G. Cost-effectiveness of dabigatran versus genotype-guided management of warfarin therapy for stroke prevention in patients with atrial fibrillation. PloS one. 2012;7(6):e39640. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Red Book Online ®. Truven Health Analytics LLC; 2017.

- 46.Levinson DR. Medicaid Drug Price Comparison: Average Sales Price to Average Wholesale Price. Office of the Inspector General: Department of Health and Human Services; 2005.

- 47.IMS Institute for Healthcare Informatics. The Use of Medicines in the United States: Review of 2010; 2011.

- 48.Long EF, Swain GW, Mangi AA. Comparative survival and cost-effectiveness of advanced therapies for end-stage heart failure. Circulation Heart failure. 2014;7(3):470–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Medicare Hospital Inpatient Prospective Payment System. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services; 2016.

- 50.Medicare Anesthesia Fee Schedule. Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services; 2016.

- 51.Mostafavi Tabatabaee R, Rasouli MR, Maltenfort MG, Parvizi J. Cost-effective prophylaxis against venous thromboembolism after total joint arthroplasty: warfarin versus aspirin. The Journal of arthroplasty. 2015;30(2):159–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.