Abstract

Introduction:

Cardiovascular disease is the most common cause of death worldwide which includes coronary heart disease (CHD) as the major contributor. The foremost cause of CHD is atherosclerosis of coronary arteries leading to angina to sudden deaths which is sharply increasing in India; sadly more in the younger people. In this study, results were compared to an autopsy result performed a decade earlier.

Aims:

Both autopsy studies were conducted to assess the frequency of coronary atherosclerosis, morphological types of lesions and the degree of stenosis in three major coronary arteries. The association of the disease to age, sex, socio-economic status, diet and obesity were studied along with correlating the severity with major risk factors such as hypertension, diabetes mellitus, hyperlipidemia and smoking.

Materials and Methods:

60 hearts in the 1st study and 120 in the 2nd study were studied after collecting from Forensic department with details of the deceased. Hearts were dissected by Virchow's method and three major coronary arteries were studied by making serial sectioning. The atherosclerotic lesions were examined histopathologically and typed according to American Heart Association classification along with grading of the luminal stenosis.

Results:

The second study showed an alarmingly higher incidence of atherosclerosis (90.83%), especially in younger age. Compared to the older study in which 68.33% had coronary atherosclerosis. In both studies coronary atherosclerosis was more in males, severity increased with age and proximal segment of left anterior descending coronary artery was the most commonly affected part with higher grade lesions.

Conclusion:

The frequency of occurrence of coronary atherosclerosis has definitely increased steeply in the past two decades and alarmingly more in the younger people, with the severity being common in the fourth decade of life itself. There is strong positive correlation with major risk factors reiterating the importance of clinical screening and preventive programs.

Keywords: Atherosclerosis, autopsy study, coronary atherosclerosis, ischaemic heart disease

INTRODUCTION

Heart is a vital organ working incessantly in supplying blood to all parts of the body. Impairment of heart function due to an inadequate blood flow to the cardiac muscle because of obstructive changes in the coronary circulation is termed “coronary heart disease” (CHD) or ischemic heart disease. More than 95% of such cases are due to atherosclerosis of one or more of the three coronary arteries, leading to stenosis and known to cause angina to myocardial infarction, and sudden death. The WHO has called CHD as the modern “epidemic” as it is the major disease accounting for 25%–30% of deaths in most industrialized countries.[1] Although CHD is described as a disease of modern times, studies have shown its presence in Egyptian mummies.[2] For many years, pathogenesis of coronary artery disease was elucidated and pathologists such as “Virchow” and “Ludvig Hektoen” contributed in the understanding of myocardial ischemia.[3]

In India, Sushruta a reknowned surgeon described circulation of vital fluids from heart and gave a vivid account of “Hritshoola” meaning heart pain 150 years before Hippocrates.[4]

The scenario of atherosclerosis in India is appalling with highest loss in potentially productive years of life (deaths in people aged 35 and 64 years of life). The reported loss was 9.2 million years in the year 2000 and projected to reach 17.9 million years by 2030 which is 9.4 times greater than loss in the USA. The incidence of CVD is reported to be 2–3 times higher in urban than in rural people.[1] The coronary artery disease has doubled in Indians during the past three decades.[5] Understanding the pathology of coronary atherosclerosis in the living persons with imaging and other techniques is expensive. Autopsy study is recommended and valued when it is done efficiently rather than as an exercise of tradition.[6]

The objectives of both studies were to find out the overall frequency of coronary atherosclerosis occurring in randomly selected medicolegal autopsies, to assess the frequency of coronary atherosclerosis in relation to age, sex, socioeconomic status, and diet, to analyze the role of risk factors, namely, smoking and alcoholism, diseases such as obesity, hyperlipidemia, diabetes mellitus, and hypertension in the development of coronary atherosclerosis and to study the distribution, morphology, and severity of atherosclerotic lesions in the three major coronary arteries, namely, left anterior descending (LAD) coronary artery, right coronary artery (RCA), and left circumflex artery (LCX).

The first study also included comparison of atherosclerosis in coronary arteries and aorta.[7]

MATERIALS AND METHODS

A descriptive analysis comparing results of two autopsy studies is presented. The first study was done from February 1991 to January 1992 in which sixty hearts with aorta up to the iliac bifurcations were studied to analyze both aortic and coronary atherosclerosis. In the second study, 120 hearts were studied between December 2010 and January 2013. These studies were done in two hospitals located close to each other in a South Indian cosmopolitan city. The hearts were collected from the Department of Forensic Medicine after medicolegal postmortems were conducted.

Specimens from unidentified cases, those for which the required history was not available and decomposed specimens were excluded from the study. Details about the case's, socioeconomic status categorized as per Kuppuswamy classification,[8] dietary habits, history of illnesses such as hypertension, hypercholesterolism, and diabetes mellitus, information about habits such as tobacco smoking and alcoholism were obtained from the closest relative of the deceased and from autopsy protocols.

The hearts were fixed in 10% buffered formalin and gross examination with recording of weight, measurements, amount of pericardial fat, hypertrophy, or any other abnormalities. The hearts were dissected by Virchow's method which follows the flow of blood and the coronary ostea were examined for obstruction.

The three major coronary arteies, the LAD artery, RCA and the LCX were studied by making serial cuts along their entire course at an interval of 3 mm. A minimum of two bits taken from the proximal and distal segments of each coronary artery and more bits were processed whenever required. Routine processing of tissue was done and 4–5 μ thick paraffin sections, stained with hematoxylin and eosin were studied. Special stains such as Verhoeff's, Van Gieson, Masson's trichrome, von Kossa, and Alizarin Red were also used when necessary.

The coronary atherosclerotic lesions were examined histopathologically and typed according to American Heart Association (AHA) classification.[9]

The degree of luminal stenosis was graded by White and Edwards method.[10]

Accordingly, the artery was typed normal when there was no obstructive lesion and when luminal stenosis of the artery was present it was graded as shown in the Table 1.

Table 1.

Grades of stenosis of lumen due to coronary atherosclerosis

| Grade | Percentage stenosis |

|---|---|

| I | Up to 25% stenosis |

| II | 26%-50% stenosis |

| III | 51%-75% stenosis |

| IV | 76%-100% stenosis |

RESULTS

The overall frequency of atherosclerosis in the first (older) study was 68.33% for coronary atherosclerosis and in the second study it was 90.8% which shows an alarming increase in occurance of the disease [Table 2]. In first study, there were 45 males and 15 females in the ratio of 3:1, aged from stillborn to 80 years and in the second study there were 96 males and 24 females in the ratio of 4:1, and age group ranged from 6 to 79 years. Maximum number was in the fourth decade.

Table 2.

Overall frequency of coronary atherosclerosis in the two autopsy studies

| Total number of cases | Positive | Negative | Percentage |

|---|---|---|---|

| 60 (first study) | 41 | 19 | 68.33 |

| 120 (second study) | 109 | 11 | 90.83 |

In the first study, atherosclerosis of aorta and coronaries were studied and compared. All cases in the first decade of life were free from aortic and coronary atherosclerosis. Second decade onward all cases showed lesions in aorta, mainly fatty streaks in the second and third decades and advanced lesions after the fourth decade.

Twenty-five percent showed coronary atherosclerosis in second decade, 45.45% of Grade I coronary lesions in the third decade, 75% in fourth decade of which Grade III and higher lesions were seen in only 16%. In fifth decade, 88.88% coronaries showed lesions of which 33.33% were Grade III and IV. In the sixth decade all the cases had lesions, 75% had Grade III and higher lesions in aortas with similar lesions in 66.77% of coronaries. In the seventh and eighth decade, severe degree atherosclerosis was seen in both aorta and coronaries [Table 3].

Table 3.

Age‑wise distribution of coronary atherosclerosis in the first study

| Age | Total number of cases | Positive cases | Involvement in percentage |

|---|---|---|---|

| Newborn to 10 | 3 | 0 | 0 |

| 11-20 | 8 | 2 | 25.00 |

| 21-30 | 11 | 5 | 45.45 |

| 31-40 | 12 | 9 | 75.00 |

| 41-50 | 9 | 8 | 88.88 |

| 51-60 | 12 | 12 | 100 |

| 61-70 | 2 | 2 | 100 |

| 71-80 | 3 | 3 | 100 |

Distribution of coronary atherosclerosis in different age groups in the second study is shown in Table 4. The significant difference between two studies was noted in the age group of 31–40 years and in the second study with 100% frequency of coronary atherosclerosis compared to 75% in the first study. About, 100% involvement was noted in the sixth decade in the first study.

Table 4.

Age‑wise distribution of coronary atherosclerosis in the second study

| Age | Total number of cases | Positive cases | Involvement in percentage |

|---|---|---|---|

| Newborn to 10 | 2 | 0 | 0 |

| 11-20 | 9 | 4 | 44.44 |

| 21-30 | 26 | 22 | 84.61 |

| 31-40 | 29 | 29 | 100 |

| 41-50 | 25 | 25 | 100 |

| 51-60 | 19 | 19 | 100 |

| 61-70 | 6 | 6 | 100 |

| 71-80 | 4 | 4 | 100 |

Coronary atherosclerosis showed its preference to males clearly in both studies who also had higher grade lesions. In the first study, of 15 females 26.6% showed coronary atherosclerosis as against 61.66% males and much higher frequency was noted in the second study with 83.33% females and 92.70% males having coronary lesions [Table 5].

Table 5.

Gender‑wise distribution of coronary atherosclerosis in the second study

| Sex | Total cases | Positive | Negative | Frequency in percentage |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Males | 96 | 89 | 7 | 92.70% |

| Females | 24 | 20 | 4 | 83.33% |

Analysis of the role of socioeconomic factors as contributory factors in the first study revealed overall 75% had coronary atherosclerosis in higher class, 72.72% in middle class and 60.86% cases in low class. In the second study, according to Kuppuswamy classification[9]93.75% of Class I and II, 92.10% of Class III, 90.00% of Class IV and 78.57% of Class V cases showed coronary atherosclerosis. These social classes also indicate to an extent the sedentary life style which is more in the higher classes.

Analysis of nutritional status in the first study revealed that 92.30% of obese persons, 64.86% of averagely nourished persons, and 50% of the poorly nourished having coronary atherosclerosis. In the second study, all the 13 (100%) obese persons and 89.71% of nonobese persons had showed the disease.

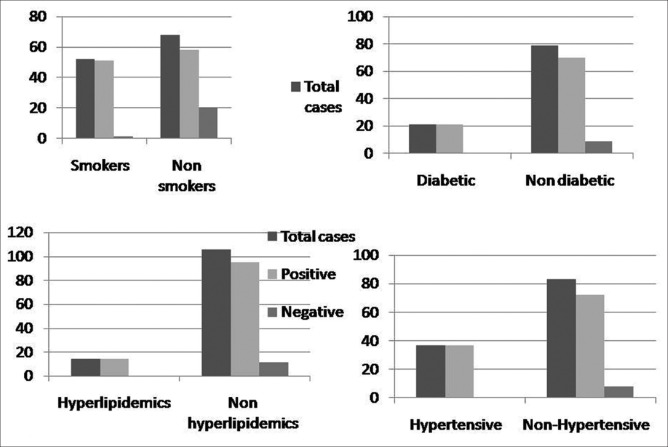

The role of habits such as tobacco smoking and alcoholism as risk factors in the first study, 91.17% of smokers had coronary atherosclerosis against 38.46% nonsmokers. Nearly, 84% alcoholics and 57.14% nonalcoholics had coronary atherosclerosis. Out of 52, 51 smokers (98.07%) in comparison with 85.29% of nonsmokers and 43 out of 45 alcoholics (93.03%) compared to 88% nonalcoholics in the second study showed coronary atherosclerosis [Figure 1].

Figure 1.

Association of high risk factors, graphs show higher incidences of coronary atherosclerosis with tobacco smoking, diabetes mellitus, hypertension, and hyperlipidemia

The role of diseases such as hypertension, diabetes mellitus, and hyperlipidemia as risk factors: in the first study, 91.66% of hypertensives compared to 62.5% of nonhypertensives and 83.33% of diabetics compared to 66.66% of nondiabetics had coronary atherosclerosis. The second study revealed all 37 (100%) cases with hypertension compared to 86.74% in nonhypertensives and all 23 with diabetes mellitus (100%) were having the disease compared to 88.65% in nondiabetics. All the 14 cases (100%) with hyperlipidemia showed coronary atherosclerosis as compared to 89.62% without hyperlipidemia [Figure 1]. Hence, both studies show a higher incidence of coronary atherosclerosis in all persons associated with risk factors which was much higher in the second study.

Analysis of the diet and its relation to atherosclerosis in the first study showed 75.55% nonvegetarians (mixed diet) and 46.66% of vegetarians having coronary atherosclerosis compared to 94.28% nonvegetarians and 86% vegetarians, respectively, in the second study.

In the first study, coronary atherosclerosis was noted in 68.33% and 95% cases had aortic atherosclerosis with lesions of varying severity. Analysis of all three major coronary artery lesions revealed single artery involvement in 14.63%, involvement of 2 arteries in 26.82%, and all the 3 coronaries in 58.53% of cases. LAD of left coronary artery was the most commonly involved with 92.68%. Cases followed by 80.48% cases of RCA and 70.73% cases of LCX. Degree of stenosis was of higher grade as age advanced.

In the second decade, only 25% had involvement with Grade I coronary atherosclerosis and 45.45% participants in the third decade had Grade I lesions. In the fourth decade, 58.33% had Grade I and 8.33% had Grade II, Grade III, and Grade IV lesions each. In the fifth decade, 22.22% had Grade I, 33.33% had Grade II, 22.22% had Grade III, and 11.11% had Grade IV lesions. In the sixth decade, 16.66% had Grade I and Grade II lesions, 41.66% had Grade III, and 25% had Grade IV lesions. Seventh decade onward 50% had Grade III and remaining 50% had Grade IV stenosis due atherosclerosis. All these cases had narrowing of coronary ostea due to atheromatous plaques [Figure 2].

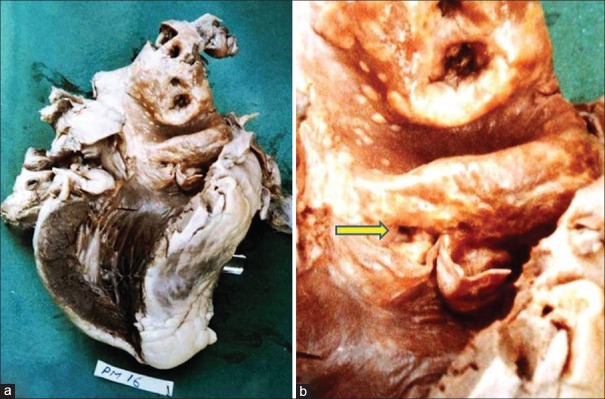

Figure 2.

Gross specimen of heart, (a) showing hypertrophied left ventricular wall with aorta and major branches showing multiple protruding atheromatus plaques, (b) shows close up view of the same heart with arrow pointing toward narrowed right coronary ostea (taken from the first study - with permission)

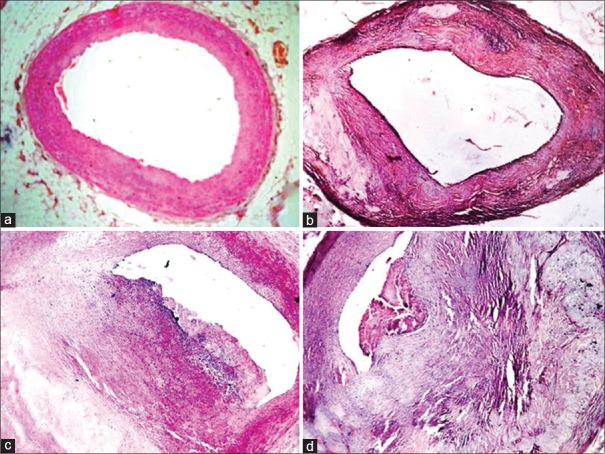

Grading of stenosis of coronary arteries depending on the percentage of obstruction of the lumen was done as shown in the Figure 3. Complicated lesions were seen mainly as calcified atheromas in 43.9%, followed by hemorrhage and thrombus formation. One case had completely occluding thrombus in the RCA, which showed very good recanalization and surprisingly this person did not die due to myocardial infarction [Figure 4].

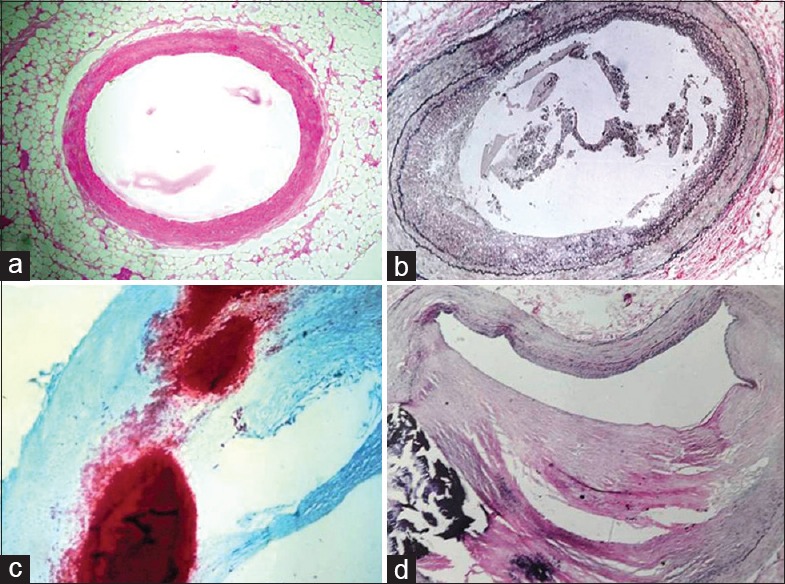

Figure 3.

Grading of stenosis of coronary arteries depending on the obstruction of the lumen, (a) grade I stenosis, (b) Grade II, (c) Grade III and (d) Grade IV stenosis (a) shows <25% block, (b) shows <50% block, (c) shows <75% block and (d) shows >75% block with an overlying thrombus (H and E, ×25)

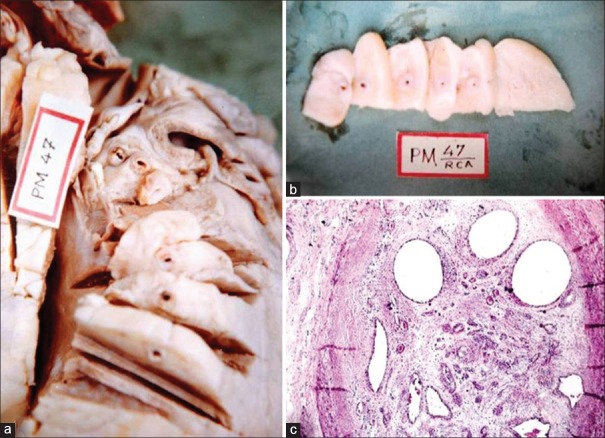

Figure 4.

Gross specimen of heart (a) and (b) show serial sections of the right coronary artery which shows gradual complete block and (c) shows sections of the same artery showing occluding thrombus with very good recanalization (H and E, ×25)

Pattern of vessel involvement in the second study is shown in the Table 6. in which triple vessel having atherosclerosis was maximum, LAD was the most commonly affected coronary artery and all 109 cases (100%) showed atherosclerosis of this artery compared to 92.7% in the first study. When two vessels were involved the combination was LAD with RCA. Special stains for demonstrating splitting of internal elastic lamina by Verhoeff's, Alizarin Red for calcium Van Gieson, Masson's trichrome, and others highlighted the histological pictures [Figure 5].

Table 6.

Pattern of vessel involvement in the second study

| Negative (no vessel involved) LAD, RCA and LCX |

One vessel involved | Two vessel involved | All 3 vessel involved LAD, RCA and LCX |

Total | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LAD | RCA | LCX | LAD and RCA | LAD and LCX | RCA and LCX | |||

| 11 | 12 (11%) | 0 | 0 | 26 (23.85%) | 0 | 0 | 71 (65.13%) | 120 |

LAD: Left anterior descending, RCA: Right coronary artery, LCX: Left circumflex

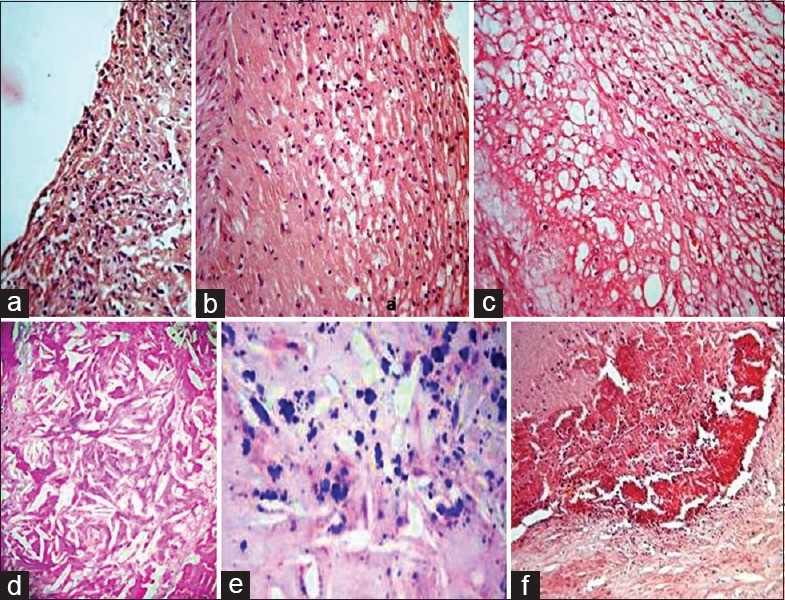

Figure 5.

Sections showing (a) normal artery with H and E, (b) special stain, Verhoeff's which highlights splitting of internal elastic lamina, ×25 (c) Alizarin Red for calcium, ×40 and (d) Verhoeff - Van Gieson highlighting fibrous tissue in an atheroma with calcification, ×25

Types of atherosclerotic lesions in the second study according to AHA in different coronary arteries are shown in the Table 7. Type III and IV lesions were found as the maximum types, more common in males in third to sixth decade. Type V and VI lesions were seen more in the age above 60 years [Figure 6]. According to AHA classification, there are six types of atherosclerotic lesions. Type I lesion shows presence of isolated macrophages and foam cells in the intima, Type II lesion shows mainly intracellular lipid accumulation or fatty streaks, Type III lesions have intracellular lipid along with small extracellular lipid pools also called as intermediate lesion, Type IV lesions have Type II changes along with a core of extracellular lipid or called a classical atheroma, Type V lesions have lipid core and fibrotic layer or multiple lipid cores and fibrotic lipid layers; mainly calcific or fibrotic and type also called as fibroatheroma and Type VI lesions have along with changes of previous Types IV or V “complicated” with added surface defect or ulceration, hematoma, hemorrhages, or thrombus formation.

Table 7.

Distribution of types of coronary atherosclerosis in the second study in relation to age and sex in left anterior descending artery according to American Heart Association

| Age | Type of lesion | Total | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| I | II | III | IV | V | VI | ||||||||

| Male | Female | Male | Female | Male | Female | Male | Female | Male | Female | Male | Female | ||

| Newborn to 10 years | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 0 |

| 11-20 | 1 | 2 | 1 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 4 |

| 21-30 | 4 | 2 | 4 | 1 | 7 | 1 | 3 | - | - | - | - | - | 22 |

| 31-40 | 2 | 2 | 5 | 1 | 8 | 1 | 9 | - | 1 | - | - | - | 29 |

| 41-50 | 2 | 1 | 4 | 2 | 6 | 1 | 5 | - | 4 | - | - | - | 25 |

| 51-60 | - | - | 4 | 0 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 1 | 3 | - | 2 | - | 19 |

| 61-70 | - | - | - | - | 0 | - | 2 | - | 3 | - | 1 | - | 6 |

| 71-80 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 4 |

| Total | 9 | 7 | 18 | 4 | 23 | 6 | 23 | 1 | 12 | 1 | 4 | 1 | 109 |

Figure 6.

Types of lesions according to American Heart Association, (a) sections showing Type I, initial lesion with isolated macrophages, (b) Type II with mainly intracellular lipid, (c) Type III with small extracellular lipid pools, (d) Type IV with core of extracellular lipid, (e) Type V with lipid core and calcification and (f) Type VI with hemorrhage (H and E, ×40) 7

Degree of stenosis in the second study depending on the amount of luminal block in relation to age and sex in the proximal segment of LAD is shown in the Table 8.

Table 8.

Degree of stenosis of left anterior descending in relation to age and sex in the second study

| Age | Grade of stenosis of lad artery | Total | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| I | II | III | IV | ||||||

| Male | Female | Male | Female | Male | Female | Male | Female | ||

| New born to 10 years | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 0 |

| 11-20 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 0 | - | - | - | - | 4 |

| 21-30 | 8 | 3 | 7 | 1 | 3 | - | - | - | 22 |

| 31-40 | 13 | 3 | 6 | 1 | 5 | - | 1 | - | 29 |

| 41-50 | 8 | 2 | 8 | 1 | 3 | 1 | 2 | - | 25 |

| 51-60 | 3 | 1 | 5 | 2 | 6 | - | 1 | 1 | 19 |

| 61-70 | - | - | 2 | - | 3 | - | 1 | - | 6 |

| 71-80 | - | - | - | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | - | 4 |

| Total | 33 | 11 | 29 | 6 | 21 | 2 | 6 | 1 | 109 |

The most common cause of death noted was due to accidents in both studies followed by suicides, sudden natural deaths, and homicides in the decreasing order of frequency. Seven out of 12 cases (58.33%) of natural deaths in first study and 10 out of 11 cases of sudden natural deaths (90.90%) in the second study were reported as deaths due to CHD. Six cases had signs of healed myocardial infarction in second study and only two cases were of this type in first study. All these cases of CHD and the nine cases with left ventricular hypertrophy had Grade III and IV stenosis of LAD and Type V and VI atherosclerosis in the both studies (P = 0.322).

Incidentally, there was one rare case of aortic aneurysm presenting in the arch of aorta due to severe atherosclerosis and damage to the wall and in this case all three coronaries showed higher grade atherosclerosis.

DISCUSSION

The Ministry of Health and Family Welfare in India has stated that “noncommunicable diseases including CVDs, diabetes mellitus, chronic respiratory diseases, and cancers account for over 60% mortality. According to World Economic Forum India stands to lose Rs. 311.94 trillion ($ 4.58 trillion) between 2012 and 2030 due to these diseases.”[11] Cardiovascular disease is projected to be the most common cause of death worldwide by 2020. Ironically, it is declining in the developed countries as a result of better prevention, treatment, and changing life style. CHD is on the rise in the middle and low income countries.[1]

Both studies included cases aged from newborn to 80 years. As in previous studies by Bhargava and Bhargava, Murthy, and Padmavati and Sandhu, males were more than females.[12,13,14] This is because of more accidental deaths among males and majority of the cases were between 20 and 60 years of age.

The first study showed overall incidence of coronary atherosclerosis in 68.3% cases compared to the 90.8% the second study which is significantly higher. The more alarming finding was the 100% frequency of coronary atherosclerosis in the age between 31 and 40 years as compared to the 75% in the first study. Padmavati and Sandhu, Murthy, Singh et al., Garg et al., and Puri et al. reported overall incidence of coronary atherosclerosis as 67.3%, 73%, 78.8%, 84.34%, and 86%, respectively.[13,14,15,16,17] A study by Vyas et al. found 73.45% incidence of coronary atherosclerosis in 113 noncardiac deaths.[18]

The major cardiovascular risk factors are similar for both sexes although men developed CHD 10–15 years earlier than women. Most of the studies have reported a higher frequency of coronary atherosclerosis in males.

A study by Singh et al. showed higher frequency of the disease in smokers and alcoholics.[15] A study by Alexander shows strong association between central obesity and CHD.[19] An autopsy study by Reed et al., high cholesterol was associated with advanced lesions of atherosclerosis.[20] Goraya et al. reported higher incidence of atherosclerosis in diabetics.[21] McGill et al. found higher incidence of lesions associated with diabetes and hypertension.[22]

The second study showed triple vessel involvement in 65.13%, followed by double vessel in 23.85% and single vessel in 11% and which is in same order of frequency in other studies. These studies also showed that LAD artery was the commonest to be involved followed by RCA and LCX.[5,16,18]

Acute coronary syndromes are associated with atheromatous plaques which are said to be vulnerable when they are associated with thrombus mediated progression causing more (88%) of sudden deaths compared to the random cases (55%).[5] The AHA classified atherosclerotic lesions from Type I to Type VI and stated that these lesions progress from one type to the next.[9] The most common coronary involved was LAD artery and the common type of lesions being Type I to Type IV. Atheromatous plaque vulnerability has been stated to be associated with thrombus mediated acute coronary syndromes by Virmani et al., using specific criteria such as thin fibrous cap of <65 μm, the fibrous cap with inflammation, fissuring, calcification, intraplaque vasa vasorum or intraplaque hemorrhage.[23]

CONCLUSION

Autopsy studies are helpful in understanding the disease process in CHD and this knowledge can be utilized in planning of screening programs. The rising cardiac death rate definitely indicates that it is the price being paid for the industrialization and rising socioeconomic status which are required but increased tobacco smoking, alcoholism, having fat rich diet and sedentary life style are not good. Improvement in healthcare by making the screening, coronary angiograms, angioplasties, and such procedures economical and available to the needy in developing countries is of prime importance.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge with respect Professor and HOD of Pathology, (Late) Dr. C. M. Jayakeerthy and Dr. L. Thirunavukkarasu the former professor and HOD of the Forensic Medicine Department, Bangalore medical college, Bangalore, for their guidance in doing the first autopsy study in 1992.

We are thankful to the 180 deceased honorable people whom we did not know personally but studied their hearts after the postmortems and expanded our understanding of coronary artery atherosclerosis.

REFERENCES

- 1.Park K. Park K, Park's Textbook of Preventive and Social Medicine. 22nd ed. Jabalpur, India: M/S Banarsidas Bhanot; 2013. Epidemiology of Chronic Non-Communicable Diseases and Conditions; pp. 338–40. [Google Scholar]

- 2.David AR, Kershaw A, Heagerty A. Atherosclerosis and diet in ancient Egypt. Lancet. 2010;375:718–9. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(10)60294-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hajar R. Evolution of myocardial infarction and its biomarkers: A historical perspective. Heart Views. 2016;17:167–72. doi: 10.4103/1995-705X.201786. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dwivedi G, Dwivedi S. Sushruta – The clinician – Teacher Par excellence. Indian J Chest Dis Allied Sci. 2007;49:243–4. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sudha ML, Sundaram S, Purushothaman KR, Kumar PS, Prathiba D. Coronary atherosclerosis in sudden cardiac death: An autopsy study. Indian J Pathol Microbiol. 2009;52:486–9. doi: 10.4103/0377-4929.56130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fausto N. Atherosclerosis in young people: The value of the autopsy for studies of the epidemiology and pathobiology of disease. Am J Pathol. 1998;153:1021–2. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)65646-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Venkatesh K, Jayakeerthy CM. Aortic atherosclerosis as a reflection of coronary atherosclerosis – An autopsy study with historical review. J Evid Based Med Healthc. 2014;1:937–49. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Park K. Medicine and social sciences. Park's Textbook of Preventive and Social Medicine. In: Park K, editor. 21st ed. Jabalpur, India: Banarasidas Bhanot; 2009. pp. 638–9. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Stary HC, Chandler AB, Glagov S, Guyton JR, Insull W, Jr, Rosenfeld ME, et al. A definition of Initial fatty streak and intermediate lesions of atherosclerosis – A report from the committee on vascular lesions of the council on arteriosclerosis, AHA. Arterioscler Thromb. 1994;14:840–56. doi: 10.1161/01.atv.14.5.840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.White NK, Edwards JE. Anomalies of the coronary arteries; report of four cases. Arch Pathol (Chic) 1948;45:766–71. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Press Information Bureau, Ministry of Health and Family Welfare, India. Health Ministry to Launch Population Based Prevention, Screening and Control Programmes for Five Non Communicable Diseases. 2017 Jan 21; [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bhargava MK, Bhargava SK. Coronary atherosclerosis in North Karnataka. Indian J Pathol Microbiol. 1975;18:65–79. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Murthy MS. Coronary atherosclerosis in North India (Delhi area) J Pathol Bacteriol. 1963;85:93–101. doi: 10.1002/path.1700850109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Padmavati S, Sandhu I. Incidence of coronary artery disease in Delhi from medico-legal autopsies. Indian J Med Res. 1969;57:465–76. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Singh H, Oberoi SS, Gorea RK, Bal MS. Atherosclerosis in coronaries in Malwa region of Punjab. J Indian Acad Forensic Med. 2005;27:32–5. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Garg M, Agarwal AD, Kataria SP. Coronary atherosclerosis and myocardial infarction an autopsy study. J Indian Acad Forensic Med. 2011;33:39–42. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Puri N, Gupta PK, Sharma J, Puri D. Prevalence of atherosclerosis in coronary artery and internal thoracic artery and its correlation in North-West Indians. Indian J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2010;26:243–6. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Vyas P, Gonsai RN, Meenakshi C, Nanavati MG. Coronary atherosclerosis in noncardiac deaths: An autopsy study. J Midlife Health. 2015;6:5–9. doi: 10.4103/0976-7800.153596. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Alexander JK. Obesity and coronary heart disease. Am J Med Sci. 2001;321:215–24. doi: 10.1097/00000441-200104000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Reed DM, Strong JP, Resch J, Hayashi T. Serum lipids and lipoproteins as predictors of atherosclerosis. An autopsy study. Arteriosclerosis. 1989;9:560–4. doi: 10.1161/01.atv.9.4.560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Goraya TY, Leibson CI, Palumbo PJ, Weston SA, Killion JM, Pfeifer EA, et al. Coronary atherosclerosis in diabetes mellitus: A population based Autopsy study. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2002;40:946–53. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(02)02065-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.McGill HC, McMahan CA, Zeiske AW, Sloop GD, Troxclair DA, Malcom GT, et al. Associations of coronary heart disease risk factors with the intermediate lesions in youth. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2000;20:1998–2004. doi: 10.1161/01.atv.20.8.1998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Virmani R, Kolodgie FD, Burke AP, Farb A, Schwartz SM. Lessons from sudden coronary death – A comprehensive morphological classification scheme for atherosclerotic lesions. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2000;20:1262–75. doi: 10.1161/01.atv.20.5.1262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]