Key Points

Question

Was state Medicaid expansion associated with differences in rates of low birth weight and preterm birth, both overall and in terms of racial/ethnic disparities?

Findings

In this observational study of 15 631 174 births from 2011 to 2016, state Medicaid expansion was not significantly associated with differences in rates of low birth weight or preterm birth outcomes overall. There were significant reductions in relative disparities for black infants (preterm birth: −0.43 percentage points, very preterm birth: −0.14 percentage points, low birth weight: −0.53 percentage points, and very low birth weight: −0.13 percentage points) but not for Hispanic infants relative to white infants in states that expanded Medicaid compared with those that did not.

Meaning

State Medicaid expansion was not associated with differences in rates of low birth weight or preterm birth outcomes overall, but was associated with improvements in relative disparities for black infants compared with white infants among the states that expanded compared with those that did not.

Abstract

Importance

Low birth weight and preterm birth are associated with adverse consequences including increased risk of infant mortality and chronic health conditions. Black infants are more likely than white infants to be born prematurely, which has been associated with disparities in infant mortality and other chronic conditions.

Objective

To evaluate whether Medicaid expansion was associated with changes in rates of low birth weight and preterm birth outcomes, both overall and by race/ethnicity.

Design, Setting, and Participants

Using US population-based data from the National Center for Health Statistics Birth Data Files (2011-2016), difference-in-differences (DID) and difference-in-difference-in-differences (DDD) models were estimated using multivariable linear probability regressions to compare birth outcomes among infants in Medicaid expansion states relative to non–Medicaid expansion states and changes in relative disparities among racial/ethnic minorities for singleton live births to women aged 19 years and older.

Exposures

State Medicaid expansion status and racial/ethnic category.

Main Outcomes and Measures

Preterm birth (<37 weeks’ gestation), very preterm birth (<32 weeks’ gestation), low birth weight (<2500 g), and very low birth weight (<1500 g).

Results

The final sample of 15 631 174 births (white infants: 8 244 924, black infants: 2 201 658, and Hispanic infants: 3 944 665) came from the District of Columbia and 18 states that expanded Medicaid (n = 8 530 751) and 17 states that did not (n = 7 100 423). In the DID analyses, there were no significant changes in preterm birth in expansion relative to nonexpansion states (preexpansion to postexpansion period, 6.80% to 6.67% [difference: −0.12] vs 7.86% to 7.78% [difference: −0.08]; adjusted DID: 0.00 percentage points [95% CI, −0.14 to 0.15], P = .98), very preterm birth (0.87% to 0.83% [difference: −0.04] vs 1.02% to 1.03% [difference: 0.01]; adjusted DID: −0.02 percentage points [95% CI, −0.05 to 0.02], P = .37), low birth weight (5.41% to 5.36% [difference: −0.05] vs 6.06% to 6.18% [difference: 0.11]; adjusted DID: −0.08 percentage points [95% CI, −0.20 to 0.04], P = .20), or very low birth weight (0.76% to 0.72% [difference: −0.03] vs 0.88% to 0.90% [difference: 0.02]; adjusted DID: −0.03 percentage points [95% CI, −0.06 to 0.01], P = .14). Disparities for black infants relative to white infants in Medicaid expansion states compared with nonexpansion states declined for all 4 outcomes, indicated by a negative DDD coefficient for preterm birth (−0.43 percentage points [95% CI, −0.84 to −0.02], P = .05), very preterm birth (−0.14 percentage points [95% CI, −0.26 to −0.02], P = .03), low birth weight (−0.53 percentage points [95% CI, −0.96 to −0.10], P = .02), and very low birth weight (−0.13 percentage points [95% CI, −0.25 to −0.01], P = .04). There were no changes in relative disparities for Hispanic infants.

Conclusions and Relevance

Based on data from 2011-2016, state Medicaid expansion was not significantly associated with differences in rates of low birth weight or preterm birth outcomes overall, although there were significant improvements in relative disparities for black infants compared with white infants in states that expanded Medicaid vs those that did not.

This study uses national health statistics data to evaluate associations between state Medicaid expansion in 2014-2016 and changes in rates of low birth weight and preterm birth, both overall and by race/ethnicity.

Introduction

Prematurity and low birth weight were estimated to contribute to 36% of infant mortality (in 2013)1 and have been associated with increased risk of chronic conditions throughout infancy and into adulthood.2,3,4,5 Rates of low birth weight (8.3% as of 2017) and prematurity (9.9%) are higher in the United States than most developed nations,6,7,8,9 with non-Hispanic black infants 2.0 times as likely to be born at low birth weight (13.9% vs 7.0%) and 1.5 times as likely to be born prematurely (13.9% vs 9.1%) compared with non-Hispanic white infants.9 Hispanic infants have rates of low birth weight (7.4% as of 2017) and prematurity (9.6%) similar to white infants.9

Since 1990, states have been required to provide Medicaid coverage to low-income pregnant women with family incomes up to 133% of the federal poverty level under the Omnibus Budget Reconciliation Act.10 Because this insurance is dependent on pregnancy, a mother will lose coverage 60 days postpartum if she does not meet the poverty threshold for Medicaid in her state, resulting in frequent transition in and out of Medicaid coverage (“insurance churning”) for many low-income women.11 Under the Affordable Care Act (ACA), states may expand Medicaid to adults with household incomes at or below 138% of the federal poverty level, which may improve continuity of access to health care for low-income women regardless of pregnancy status, potentially improving maternal health and earlier use of prenatal care.11,12 Evaluation of the association between ACA Medicaid expansion and infant outcomes is limited, with one study finding reductions in infant mortality in Medicaid expansion relative to nonexpansion states.13

The objective of this study was to evaluate the association between Medicaid expansion and rates of low birth weight and prematurity overall and among racial/ethnic minorities relative to non-Hispanic white (hereafter “white”) infants. It was hypothesized that adverse outcomes would be reduced in expansion relative to nonexpansion states with greater declines among non-Hispanic black (hereafter “black”) infants given greater increases in insurance coverage post-ACA and greater rates of adverse birth outcomes among black infants.9,14

Methods

The University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences Institutional Review Board deemed this study as non–human subjects research, and informed consent was waived.

Data Sources

The primary data source was the National Center for Health Statistics (NCHS) Vital Statistics Birth Data Files (2011-2016), which contain data abstracted from an estimated 99% of live births from all 50 states and the District of Columbia.15 The Birth Data Files were linked with 2 secondary data sources (2011-2016) at the state and year levels (see eMethods in the Supplement for exceptions): (1) area-level demographics and access to health care services came from weighted averages of county-level data from the Health Resources and Services Administration’s Area Health Resource File database and (2) state-level health outcomes came from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System Prevalence Data.

Study Sample

Included States

The standardized birth certificate data collection process and collected data were changed in 2003, with states varying in their adoption of the 2003 revision of the US Standard Certificate of Life Birth.15 Births from states that did not use the 2003 version by January 1, 2013 (at least 1 year prior to Medicaid expansion), were excluded. Among states that adopted the revised version in 2012 or 2013, births were excluded if they occurred in a year prior to the state’s first full year of adoption. States were additionally excluded if they used a Section 1115 waiver for Medicaid expansion. See the Supplement for state classifications (eTable 1 in the Supplement) and dates of expansion and 2003 revised birth certificate adoption (eTable 2 in the Supplement).

Sample of Births

Analyses were limited to births to women aged 19 years and older to ensure the woman was an adult (age ≥18) at the time of conception. Births with missing information on 1 or more variables were excluded (eFigure 1 in the Supplement). A χ2 test was conducted to test for a difference in the percentage of births that were excluded between Medicaid nonexpansion and expansion states.

Given the substantial disparities in adverse birth outcomes among racial/ethnic minorities, this study assessed changes in relative disparities by comparing outcomes in black infants and in Hispanic infants relative to white infants. Mutually exclusive racial/ethnic categories were created using the single-race variable and an indicator of Hispanic ethnicity. The NCHS recommends collecting race/ethnic information directly from the mother with predefined categories and the option to write in an “other” response. Following the National Vital Statistics Reports categorization, a woman who indicated any race in addition to Hispanic ethnicity was categorized as “Hispanic.”9 Analyses were additionally conducted separately for Medicaid-covered births and Medicaid-covered births to women aged 26 years and older with at most a high school degree. Medicaid funding and educational attainment were used as proxies for lower-income groups that may be more likely to benefit from expansion.

Independent Variables

The primary exposure variable was state Medicaid expansion. Previous studies vary on expansion state classification because states differed by expansion date.16,17,18 Twenty six states and the District of Columbia expanded Medicaid on January 1, 2014; 2 states expanded later in 2014; and 5 states expanded in 2015 or 2016.19 All states that expanded Medicaid in 2014-2016 were defined as expansion states regardless of previous expansion efforts, with the exception of the 8 states with approved Section 1115 waivers for Medicaid expansion by 2016,19 which were excluded from the study (eTable 1 in the Supplement). The month of expansion marked the beginning of the postexpansion period for later expanding states; a date of January 1, 2014, was used for nonexpansion states and for states that expanded on this date.

Dependent Variables

The dependent variables included preterm birth (<37 weeks’ gestation), very preterm birth (<32 weeks’ gestation), low birth weight (<2500 g), and very low birth weight (<1500 g). Gestation was based primarily on the clinical/obstetric estimate, which the NCHS uses as the standard for estimating gestational age.15

It was hypothesized that increased insurance coverage among low-income women may improve infant outcomes through mechanisms such as improved maternal health and earlier access to prenatal care services.12,20 Several exploratory mechanisms were tested including prenatal care initiation in the first trimester, prepregnancy diabetes, prepregnancy hypertension, cigarette use in the first trimester, any infection, and a measure of paternal acknowledgment.

Statistical Analysis

Descriptive statistics compared differences among births in Medicaid expansion and nonexpansion states overall and within each racial/ethnic group in the period prior to expansion. A difference-in-differences (DID) approach was used to compare changes in outcomes in expansion vs nonexpansion states, which can control for external secular trends by using nonexpansion states as a counterfactual.18,21,22 DID models were estimated including births of all races/ethnicities as well as for white, black, and Hispanic infants separately. A difference-in-difference-in-differences (DDD) approach was used to assess the change in birth outcomes for minority infants (ie, black and Hispanic infants, separately) in expansion states relative to nonexpansion states compared with the change in birth outcomes for white infants in expansion states relative to nonexpansion states.23,24 It was hypothesized that there would be greater reductions among minority infants, indicated by negative DDD coefficients.

DID and DDD models were estimated using multivariable linear probability models, with standard errors clustered at the state level and controlling for maternal, infant, and state-level factors (Table 1 and Table 2; see eMethods in the Supplement for a complete description) and for state-level dummy variables to control for any unobserved state-level effects that were time invariant. Linear probability models provided estimated percentage-point changes in the treatment (expansion) relative to the control (nonexpansion) states.25 Similar analyses were conducted to evaluate differential changes in the proposed mechanisms (eg, initiation of prenatal care in the first trimester) between Medicaid expansion and nonexpansion states using the same study sample and data as the primary analyses and can be found in eTable 8 in the Supplement.

Table 1. Descriptive Statistics of State-Level Characteristics by Medicaid Expansion Status in the Pre–Medicaid Expansion Perioda,b.

| Mean (SD) | Difference (95% CI) | P Value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Expansion | Nonexpansion | |||

| No. of statesb | 18 and District of Columbia | 17 | ||

| No. of births in preexpansion period | 3 744 870 | 3 355 553 | ||

| No. of births in postexpansion period | 4 134 179 | 4 396 572 | ||

| Median household income, $c | 56 054 (8223) | 49 489 (5366) | 6566 (3812 to 9319) | <.001 |

| Total hospital beds per 1000c | 3.2 (1.2) | 3.4 (0.9) | −0.2 (−0.7 to 0.2) | .26 |

| Proportion of females who are uninsured, %c | 15.7 (5.9) | 19.9 (4.8) | −4.2 (−6.3 to −2.1) | <.001 |

| Proportion of minority women, %c,d | 35.1 (16.2) | 28.2 (12.5) | 6.9 (1.2 to 12.6) | .02 |

| No. of primary care physicians per 1000 populationc | 0.82 (0.14) | 0.68 (0.07) | 0.14 (0.10 to 0.19) | <.001 |

| Proportion of population with good or better health, %e | 83.4 (3.0) | 82.7 (2.9) | 0.7 (−0.5 to 1.8) | .26 |

| Proportion of adults who had cholesterol checked, %e | 79.6 (3.5) | 77.4 (3.7) | 2.3 (0.9 to 3.7) | .002 |

| Proportion of adults who are never smokers, %e | 55.4 (3.2) | 55.7 (5.3) | −0.3 (−1.9 to 1.4) | .74 |

State-level descriptives were calculated by averaging the yearly values for each state in the preexpansion period (n = 106).

The preexpansion period was 2011 through the month of Medicaid expansion in expansion states and was 2011-2014 for nonexpansion states. Medicaid expansion states included the District of Columbia and 18 states: Alaska, California, Colorado, Delaware, Illinois, Louisiana, Maryland, Massachusetts, Minnesota, Nevada, New Mexico, New York, North Dakota, Ohio, Oregon, Pennsylvania, Vermont, and Washington. Non–Medicaid expansion states included 17 states: Florida, Georgia, Idaho, Kansas, Mississippi, Missouri, Nebraska, North Carolina, Oklahoma, South Carolina, South Dakota, Tennessee, Texas, Utah, Virginia, Wisconsin, and Wyoming.

Yearly state value calculated by aggregating county values from the Health Resources and Services Administration’s Area Health Resource Files, weighted by county population.

The percentage of minority women was calculated as 100% minus the percentage of the female population that was non-Hispanic white race/ethnicity.

Yearly state-level information from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System (BRFSS) Prevalence Data. The proportion of the population with good or better health is a calculated value in the BRFSS Prevalence Data indicating the proportion of respondents who reported at least good health among the following options: poor, fair, good, very good, or excellent.

Table 2. Descriptive Statistics of Individual-Level Characteristics by Racial/Ethnic Group and Medicaid Expansion Status in the Pre–Medicaid Expansion Perioda.

| Overall (Births to Mothers of All Races/Ethnicities)b | Characteristics Stratified by Race/Ethnicity | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Non-Hispanic White | Non-Hispanic Black | Hispanic | ||||||||||

| %c | Difference (95% CI)c |

%c | Difference (95% CI)c |

%c | Difference (95% CI)c |

%c | Difference (95% CI)c |

|||||

| Expansion | Nonexpansion | Expansion | Nonexpansion | Expansion | Nonexpansion | Expansion | Nonexpansion | |||||

| No. of births | 4 396 572 | 3 355 553 | 2 301 966 | 1 835 476 | 553 056 | 539 803 | - | 1 118 300 | 816 119 | - | ||

| Maternal Characteristics | ||||||||||||

| Payment sourced | ||||||||||||

| Medicaid | 42.1 | 44.5 | −2.3 (−2.4 to −2.3) | 27.4 | 34.3 | −6.9 (−7.0 to −6.8) | 65.4 | 68.2 | −2.9 (−3.0 to −2.7) | 65.1 | 53.7 | 11.3 (11.2 to 11.5) |

| Private | 50.7 | 43.9 | 6.8 (6.7 to 6.9) | 65.3 | 57.9 | 7.4 (7.3 to 7.5) | 27.8 | 23.9 | 3.8 (3.7 to 4.0) | 28.0 | 23.4 | 4.6 (4.5 to 4.7) |

| Other | 4.6 | 5.5 | −0.9 (−1.0 to −0.9) | 4.8 | 4.3 | 0.5 (0.4 to 0.5) | 5.1 | 3.9 | 1.2 (1.1 to 1.2) | 4.0 | 9.1 | −5.2 (−5.3 to −5.1) |

| Self-paye | 2.6 | 6.2 | −3.6 (−3.6 to −3.5) | 2.5 | 3.5 | −1.0 (−1.0 to −1.0) | 1.8 | 3.9 | −2.1 (−2.2 to −2.1) | 3.0 | 13.7 | −10.8 (−10.8 to −10.7) |

| Race/ethnicityf | ||||||||||||

| Non-Hispanic whitee | 52.4 | 54.7 | −2.3 (−2.4 to −2.3) | |||||||||

| Non-Hispanic black | 12.6 | 16.1 | −3.5 (−3.6 to −3.5) | |||||||||

| Hispanic | 25.4 | 24.3 | 1.1 (1.1 to 1.2) | |||||||||

| Other | 9.6 | 4.9 | 4.7 (4.7 to 4.8) | |||||||||

| Age category, yg | ||||||||||||

| 18-21e | 15.7 | 19.7 | −4.1 (−4.1 to −4.0) | 12.4 | 16.5 | −4.1 (−4.2 to −4.0) | 25.1 | 28.4 | −3.3 (−3.5 to −3.1) | 21.1 | 22.8 | −1.7 (−1.8 to −1.6) |

| 22-25 | 20.6 | 23.5 | −2.9 (−3.0 to −2.9) | 19.4 | 23.0 | −3.7 (−3.8 to −3.6) | 24.8 | 26.1 | −1.3 (−1.4 to −1.1) | 23.4 | 24.0 | −0.6 (−0.7 to −0.4) |

| 26-30 | 31.1 | 30.5 | 0.7 (0.6 to 0.7) | 33.5 | 33.2 | 0.3 (0.2 to 0.4) | 25.8 | 24.7 | 1.1 (0.9 to 1.3) | 27.8 | 27.4 | 0.4 (0.3 to 0.6) |

| 31-35 | 22.9 | 19.0 | 3.9 (3.9 to 4.0) | 25.0 | 20.2 | 4.8 (4.7 to 4.9) | 16.5 | 14.6 | 1.9 (1.8 to 2.0) | 18.8 | 17.8 | 1.0 (0.9 to 1.1) |

| ≥36d | 9.7 | 7.3 | 2.4 (2.3 to 2.4) | 9.8 | 7.1 | 2.7 (2.6 to 2.7) | 7.8 | 6.2 | 1.6 (1.5 to 1.6) | 8.9 | 8.0 | 0.9 (0.8 to 1.0) |

| Educational status | ||||||||||||

| High school or lesse | 38.9 | 41.2 | −2.4 (−2.5 to −2.3) | 27.0 | 29.7 | −2.8 (−2.8 to −2.7) | 48.2 | 48.6 | −0.4 (−0.6 to −0.2) | 63.9 | 64.3 | −0.4 (−0.5 to −0.3) |

| Attended or completed college | 48.7 | 50.3 | −1.6 (−1.7 to −1.5) | 56.2 | 59.3 | −3.1 (−3.2 to −3.0) | 46.5 | 46.4 | 0.0 (−0.2 to 0.2) | 32.9 | 32.8 | 0.1 (−0.0 to 0.3) |

| More than bachelor’s | 12.5 | 8.5 | 4.0 (3.9 to 4.0) | 16.8 | 10.9 | 5.9 (5.8 to 6.0) | 5.4 | 5.0 | 0.4 (0.3 to 0.5) | 3.2 | 3.0 | 0.3 (0.2 to 0.3) |

| Body mass index categoryh | ||||||||||||

| Underweight | 3.6 | 3.8 | −0.2 (−0.2 to −0.2) | 3.5 | 4.1 | −0.6 (−0.6 to −0.6) | 3.2 | 3.4 | −0.2 (−0.2 to −0.1) | 2.4 | 2.8 | −0.4 (−0.4 to −0.3) |

| Normal weighte | 47.2 | 45.9 | 1.3 (1.2 to 1.3) | 51.2 | 49.7 | 1.5 (1.5 to 1.6) | 35.3 | 35.0 | 0.2 (0.0 to 0.4) | 39.3 | 42.4 | −3.1 (−3.2 to −3.0) |

| Overweight or obese | 49.2 | 50.3 | −1.1 (−1.1 to −1.0) | 45.3 | 46.3 | −0.9 (−1.0 to −0.8) | 61.5 | 61.6 | −0.1 (−0.2 to 0.1) | 58.2 | 54.8 | 3.5 (3.3 to 3.6) |

| Married | 61.9 | 61.4 | 0.5 (0.4 to 0.6) | 73.0 | 72.8 | 0.2 (0.1 to 0.3) | 29.6 | 30.6 | −1.0 (−1.2 to −0.8) | 47.9 | 52.8 | −4.9 (−5.0 to −4.7) |

| Previous preterm birth | 2.4 | 2.4 | −0.0 (−0.0 to 0.0) | 2.5 | 2.5 | −0.1 (−0.1 to −0.0) | 4.1 | 3.1 | 1.0 (0.9 to 1.1) | 1.9 | 1.9 | −0.0 (−0.0 to 0.0) |

| Prepregnancy diabetesi | 0.7 | 0.8 | −0.1 (−0.1 to −0.1) | 0.6 | 0.7 | −0.1 (−0.1 to −0.0) | 1.1 | 1.1 | −0.0 (−0.1 to 0.0) | 0.8 | 0.9 | −0.2 (−0.2 to −0.1) |

| Prepregnancy hypertensioni | 1.4 | 1.6 | −0.1 (−0.1 to −0.1) | 1.3 | 1.4 | −0.1 (−0.1 to −0.1) | 3.3 | 3.1 | 0.3 (0.2 to 0.3) | 0.8 | 0.9 | −0.1 (−0.1 to −0.1) |

| Pregnancy hypertensioni | 4.1 | 4.9 | −0.8 (−0.9 to −0.8) | 4.4 | 5.1 | −0.7 (−0.7 to −0.6) | 5.8 | 6.0 | −0.1 (−0.2 to −0.1) | 3.0 | 4.1 | −1.1 (−1.2 to −1.1) |

| Eclampsiai | 0.2 | 0.2 | 0.1 (0.1 to 0.1) | 0.2 | 0.2 | 0.1 (0.1 to 0.1) | 0.4 | 0.2 | 0.2 (0.1 to 0.2) | 0.2 | 0.1 | 0.1 (0.0 to 0.1) |

| Any infectioni | 2.0 | 2.6 | −0.5 (−0.5 to −0.5) | 1.4 | 1.6 | −0.2 (−0.2 to −0.2) | 5.2 | 5.9 | −0.7 (−0.8 to −0.6) | 1.5 | 2.4 | −0.9 (−0.9 to −0.8) |

| Infant Characteristics | ||||||||||||

| Prenatal care in first trimester | 77.6 | 71.9 | 5.7 (5.7 to 5.8) | 81.1 | 78.0 | 3.1 (3.1 to 3.2) | 66.6 | 63.9 | 2.7 (2.5 to 2.8) | 75.3 | 63.6 | 11.7 (11.6 to 11.8) |

| Total birth order | ||||||||||||

| 1e | 31.3 | 30.7 | 0.6 (0.5 to 0.7) | 33.7 | 33.2 | 0.5 (0.4 to 0.6) | 26.0 | 28.6 | −2.6 (−2.7 to −2.4) | 26.6 | 25.4 | 1.2 (1.1 to 1.3) |

| 2-4 | 58.0 | 58.8 | −0.7 (−0.8 to −0.7) | 56.9 | 57.6 | −0.7 (−0.8 to −0.6) | 56.6 | 57.5 | −1.0 (−1.2 to −0.8) | 61.8 | 62.5 | −0.7 (−0.9 to −0.6) |

| ≥5 | 10.7 | 10.6 | 0.1 (0.1 to 0.2) | 9.4 | 9.2 | 0.2 (0.2 to 0.3) | 17.4 | 13.9 | 3.5 (3.4 to 3.7) | 11.7 | 12.1 | −0.4 (−0.5 to −0.3) |

| Infant sex | ||||||||||||

| Malee | 51.2 | 51.2 | 0.0 (−0.0 to 0.1) | 51.3 | 51.3 | 0.0 (−0.1 to 0.1) | 50.8 | 50.7 | 0.1 (−0.1 to 0.3) | 51.0 | 51.0 | −0.0 (−0.2 to 0.1) |

| Female | 48.8 | 48.8 | −0.0 (−0.1 to 0.0) | 48.7 | 48.7 | −0.0 (−0.1 to 0.1) | 49.2 | 49.3 | −0.1 (−0.3 to 0.1) | 49.0 | 49.0 | 0.0 (−0.1 to 0.2) |

| Father acknowledgedj | 90.4 | 87.6 | 2.8 (2.7 to 2.8) | 94.0 | 92.3 | 1.7 (1.7 to 1.8) | 72.6 | 68.7 | 3.9 (3.8 to 4.1) | 90.0 | 88.7 | 1.3 (1.3 to 1.4) |

The preexpansion period was 2011 through the month of Medicaid expansion in expansion states and was 2011-2014 for nonexpansion states. Medicaid expansion and nonexpansion states are listed in footnote “b” of Table 1.

Number of births in the non-Hispanic white, non-Hispanic black, and Hispanic categories do not sum to the number of births in the overall category because births of any race and ethnicity were included in the overall category.

Percentages may not add up to 100%, and the difference values may not be equal to the expansion minus the nonexpansion value due to rounding.

For subgroup analyses of Medicaid-covered births and Medicaid-covered births to women with at most a high school degree in Table 4, payer type was not included as a covariate. For subgroup analyses of Medicaid-covered births to women with at most a high school degree, the reference category for age was 36 years and older.

Reference category in regression analyses.

The other racial/ethnic category includes births that were not classified as non-Hispanic white, non-Hispanic black, or Hispanic. Hispanic births included births of any racial/ethnic group with a positive indicator for Hispanic ethnicity.

The mother’s age was based on the age at the time of birth minus 1 year to ensure the mother was at least 18 years old at the time of conception.

Underweight, normal weight, and overweight or obese categories were defined as a mother with a prepregnancy body mass index of <18.5, 18.5 to 24.9, and ≥25.0 (calculated by the NCHS as weight in pounds divided by height in inches squared times 703).

Prepregnancy diabetes, prepregnancy hypertension, pregnancy hypertension, and eclampsia are pregnancy risk factors indicated within the Birth Data Files as binary variables and are recommended to be taken directly from the medical record for the birth. Prepregnancy diabetes and prepregnancy hypertension indicate conditions present prior to the pregnancy. Any infection was created as a binary variable equal to 1 if the birth record indicated that the mother had gonorrhea, syphilis, chlamydia, hepatitis B, or hepatitis C present and/or treated during the pregnancy, which are recommended to be taken from the medical record of the birth.

Acknowledgment of a father was created as a binary variable equal to 1 for women who were married at any point during pregnancy or for births with a completed paternal acknowledgment form at the time of the birth certificate documentation completion.

An assumption of the DID and DDD approaches is that the rate of a given outcome among the treatment and comparison groups is parallel in the time prior to the treatment date.26 This assumption was tested by assessing interactions in the preexpansion period (2011-2013) between state expansion status and a year-based time variable for DID analyses and additionally with a binary racial/ethnic variable for DDD analyses. Line graphs were created to visualize outcomes over time.

This study included 2 sets of robustness checks. First, DID and DDD analyses were reestimated to include a 1-year lag after expansion. Second, different state exclusion criteria were tested by separately including Section 1115 waiver states, excluding states that expanded Medicaid after January 1, 2014, and excluding states that adopted the 2003 revised birth certificate in 2012 or 2013.

Analyses were completed in SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc). Visualizations were created using Tableau Software 2018.3 (Tableau). A 2-sided P ≤ .05 was considered statistically significant. Because of the potential for type 1 error due to multiple comparisons, findings for analyses of secondary end points should be interpreted as exploratory.

Results

Among the 17 319 894 singleton live births to women aged 19 years and older in eligible states, 9.75% of births (770 618/7 903 838) from the 17 nonexpansion states and 9.75% of births (918 102/9 416 056) from the District of Columbia and 18 expansion states were excluded due to missing information (χ2 test for difference in proportions P = .97), resulting in a final sample of 15 631 174 births (eFigure 1 in the Supplement). Births from 15 states were excluded: 7 states that did not use the 2003 version by 2013, 6 states that used a Section 1115 waiver, and 2 states that met both exclusion criteria. The racial/ethnic subgroups included 8 244 924 births to white women, 2 201 658 births to black women, and 3 944 665 births to Hispanic women.

Table 1 describes differences in state-level characteristics in the period prior to expansion. Relative to nonexpansion states, Medicaid expansion states had higher median incomes ($56 054 vs $49 489; difference: $6566 [95% CI, $3812-$9319]; P < .001), a lower percentage of uninsured females (15.7% vs 19.9%; difference: −4.2 percentage points [95% CI, −6.3 to −2.1]; P < .001), a higher percentage of minority females (35.1% vs 28.2%; difference: 6.9 percentage points [95% CI, 1.2-12.6]; P = .02), a higher number of primary care physicians per 1000 (0.82 vs 0.68; difference: 0.14 [95% CI, 0.10-0.19]; P < .001), and a higher percentage of adults who had their cholesterol checked in the last 5 years (79.6% vs 77.4%; difference: 2.3 percentage points [95% CI, 0.9-3.9]; P = .002).

Table 2 describes maternal and infant characteristics pooled among all races/ethnicities (“overall”) and among white, black, and Hispanic births in the period prior to expansion. Medicaid expansion and nonexpansion states differed with respect to characteristics that are associated with birth outcomes. Expansion states had a higher percentage of births covered by private insurance (50.7% vs 43.9%; difference: 6.8 percentage points [95% CI, 6.7-6.9]), a lower percentage of births to mothers who had attained high school or less education (38.9% vs 41.2%; difference: −2.4 percentage points [95% CI, −2.5 to −2.3]), and a higher percentage of births with prenatal care initiated during the first trimester (77.6% vs 71.9%; difference: 5.7 percentage points [95% CI, 5.7-5.8]).

The leftmost columns of Table 3 provide the unadjusted rates and percentage-point changes in outcomes by state expansion status and pre/postexpansion date, stratified vertically by racial/ethnic group. Among births of all races/ethnicities, adverse outcomes in expansion states declined for preterm birth (6.80% to 6.67%; difference: −0.12 [95% CI, −0.16 to −0.09]), very preterm birth (0.87% to 0.83%; difference: −0.04 [95% CI, −0.05 to −0.02]), low birth weight (5.41% to 5.36%; difference: −0.05 [95% CI, −0.08 to −0.02]), and very low birth weight (0.76% to 0.72%; difference: −0.03 [95% CI, −0.04 to −0.02]). Changes in outcomes in nonexpansion states were not significant for 1 outcome (very preterm birth: 1.02% to 1.03%; difference: 0.01 [95% CI, −0.01 to 0.02]), decreased for 1 outcome (preterm birth: 7.86% to 7.78%; difference: −0.08 [95% CI, −0.12 to −0.04]), and increased for 2 outcomes (low birth weight: 6.06% to 6.18%; difference: 0.11 [95% CI, 0.08-0.15] and very low birth weight: 0.88% to 0.90%; difference: 0.02 [95% CI, 0.00-0.03]). Relative percentage changes for all subgroups can be found in eFigures 2, 3, 4, and 5 in the Supplement.

Table 3. Unadjusted and Adjusted Changes in Birth Outcomes Associated With Medicaid Expansiona,b.

| Expansion | Nonexpansion | Difference-in-Differencesc | Difference-in-Difference-in-Differencesc | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Preexpansion, % | Postexpansion, % | Unadjusted Difference (95% CI), Percentage Points | Preexpansion, % | Postexpansion, % | Unadjusted Difference (95% CI), Percentage Points | Percentage Points | P Value | Percentage Points | P Value | |||

| Unadjusted (95% CI) | Adjusted (95% CI) | Unadjusted (95% CI) | Adjusted (95% CI) | |||||||||

| Overall | ||||||||||||

| No. | 4 396 572 | 4 134 179 | 3 355 553 | 3 744 870 | ||||||||

| Preterm | 6.80 | 6.67 | −0.12 (−0.16 to −0.09) | 7.86 | 7.78 | −0.08 (−0.12 to −0.04) | −0.05 (−0.10 to 0.00) | 0.00 (−0.14 to 0.15) | .98 | |||

| Very preterm | 0.87 | 0.83 | −0.04 (−0.05 to −0.02) | 1.02 | 1.03 | 0.01 (−0.01 to 0.02) | −0.04 (−0.06 to −0.02) | −0.02d (−0.05 to 0.02) | .37 | |||

| Low birth weight | 5.41 | 5.36 | −0.05 (−0.08 to −0.02) | 6.06 | 6.18 | 0.11 (0.08 to 0.15) | −0.17 (−0.21 to −0.12) | −0.08 (−0.20 to 0.04) | .20 | |||

| Very low birth weight | 0.76 | 0.72 | −0.03 (−0.04 to −0.02) | 0.88 | 0.90 | 0.02 (0.00 to 0.03) | −0.05 (−0.07 to −0.03) | −0.03 (−0.06 to 0.01) | .14 | |||

| Non-Hispanic White Infants | ||||||||||||

| No. | 2 301 966 | 2 103 170 | 1 835 476 | 2 004 312 | ||||||||

| Preterm | 6.03 | 5.90 | −0.13 (−0.18 to −0.09) | 6.98 | 6.81 | −0.18 (−0.23 to −0.13) | 0.04 (−0.03 to 0.11) | 0.07 (−0.06 to 0.20) | .31 | |||

| Very preterm | 0.64 | 0.63 | −0.01 (−0.03 to 0.00) | 0.74 | 0.73 | −0.01 (−0.02 to 0.01) | −0.01 (−0.03 to 0.02) | −0.01 (−0.04 to 0.02) | .58 | |||

| Low birth weight | 4.40 | 4.37 | −0.03 (−0.07 to 0.01) | 4.89 | 4.86 | −0.03 (−0.07 to 0.02) | 0.00 (−0.06 to 0.06) | −0.01d (−0.11 to 0.10) | .91 | |||

| Very low birth weight | 0.54 | 0.52 | −0.02 (−0.03 to −0.01) | 0.62 | 0.62 | −0.01 (−0.02 to 0.01) | −0.01 (−0.04 to 0.01) | −0.02 (−0.05 to 0.01) | .13 | |||

| Non-Hispanic Black Infants | ||||||||||||

| No. | 553 056 | 461 345 | 539 803 | 647 454 | ||||||||

| Preterm | 10.21 | 9.61 | −0.60 (−0.72 to −0.49) | 10.94 | 10.90 | −0.04 (−0.15 to 0.07) | −0.56 (−0.73 to −0.40) | −0.26 (−0.65 to 0.12) | .19 | −0.61 (−0.78 to −0.43) | −0.43 (−0.84 to −0.02) | .05 |

| Very preterm | 1.97 | 1.81 | −0.17 (−0.22 to −0.11) | 2.09 | 2.08 | −0.02 (−0.07 to 0.04) | −0.15 (−0.23 to −0.08) | −0.13d (−0.25 to −0.01) | .04 | −0.14 (−0.22 to −0.07) | −0.14 (−0.26 to −0.02) | .03 |

| Low birth weight | 9.96 | 9.50 | −0.45 (−0.57 to −0.34) | 10.61 | 10.81 | 0.20 (0.09 to 0.31) | −0.65 (−0.81 to −0.49) | −0.44 (−0.77 to −0.11) | .01 | −0.65 (−0.82 to −0.48) | −0.53d (−0.96 to −0.10) | .02 |

| Very low birth weight | 1.82 | 1.69 | −0.13 (−0.18 to −0.08) | 1.93 | 1.95 | 0.02 (−0.03 to 0.07) | −0.15 (−0.22 to −0.07) | −0.15d (−0.25 to −0.05) | .01 | −0.13 (−0.21 to −0.06) | −0.13 (−0.25 to −0.01) | .04 |

| Hispanic Infants | ||||||||||||

| No. | 1 118 300 | 1 114 816 | 816 119 | 895 430 | ||||||||

| Preterm | 6.78 | 7.00 | 0.22 (0.15 to 0.28) | 7.89 | 7.86 | −0.04 (−0.12 to 0.04) | 0.25 (0.15 to 0.36) | −0.10d (−0.29 to 0.09) | .31 | 0.21 (0.09 to 0.33) | 0.02 (−0.15 to 0.18) | .84 |

| Very preterm | 0.85 | 0.87 | 0.02 (0.00 to 0.05) | 0.99 | 0.99 | −0.01 (−0.04 to 0.02) | 0.03 (−0.01 to 0.07) | −0.01 (−0.05 to 0.03) | .66 | 0.04 (−0.01 to 0.08) | 0.03 (−0.02 to 0.08) | .29 |

| Low birth weight | 5.04 | 5.23 | 0.19 (0.14 to 0.25) | 5.62 | 5.70 | 0.08 (0.01 to 0.15) | 0.12 (0.03 to 0.21) | −0.09d (−0.22 to 0.03) | .16 | 0.12 (0.01 to 0.22) | 0.01 (−0.13 to 0.14) | .92 |

| Very low birth weight | 0.71 | 0.74 | 0.02 (0.00 to 0.05) | 0.80 | 0.81 | 0.01 (−0.02 to 0.04) | 0.01 (−0.02 to 0.05) | −0.01 (−0.06 to 0.04) | .78 | 0.03 (−0.01 to 0.07) | 0.02d (−0.02 to 0.06) | .33 |

Birth outcomes included preterm birth (<37 weeks’ gestation), very preterm birth (<32 weeks’ gestation), low birth weight (<2500 g), and very low birth weight (<1500 g).

The preexpansion period was 2011 through the month of Medicaid expansion in expansion states and was 2011-2014 for nonexpansion states. Medicaid expansion and nonexpansion states are listed in footnote “b” of Table 1.

Coefficients were calculated using linear regression models with estimates multiplied by 100 to provide percentage-point differences. Adjusted difference-in-differences and adjusted difference-in-difference-in-differences regressions were adjusted for all state-level and individual-level characteristics outlined in Tables 1 and 2 as well as for state-level dummy variables with standard errors clustered at the state level. Difference-in-difference-in-differences estimates compared black infants with white infants as well as Hispanic infants with white infants. Because the difference-in-difference-in-differences analyses compare minority infants vs white infants, there are no difference-in-difference-in-differences estimates for the overall group or for the white infant category.

Indicates outcome in adjusted difference-in-differences or difference-in-difference-in-differences regression that does not pass the parallel trends test.

In the adjusted DID analyses, which describe the association between Medicaid expansion and rates of birth outcomes, negative DID estimates would indicate a greater decline in the rate of preterm birth in expansion relative to nonexpansion states. The adjusted DID estimate for all 4 outcomes was not statistically significant, indicating no association of Medicaid expansion with preterm birth (0.00 percentage points [95% CI, −0.14 to 0.15], P = .98), very preterm birth (−0.02 percentage points [95% CI, −0.05 to 0.02], P = .37), low birth weight (−0.08 percentage points [95% CI, −0.20 to 0.04], P = .20), or very low birth weight (−0.03 percentage points [95% CI, −0.06 to 0.01], P = .14) (Table 3).

Table 3 additionally provides unadjusted and adjusted DDD estimates for black and Hispanic infants, which indicate whether changes in outcomes in expansion vs nonexpansion states differed when comparing black or Hispanic infants with white infants. A significant DDD coefficient indicates a change in the relative disparity for that minority group relative to white infants. Disparities for black infants relative to white infants in Medicaid expansion states compared with nonexpansion states declined for all 4 outcomes, indicated by a negative adjusted DDD coefficient for preterm birth (−0.43 percentage points [95% CI, −0.84 to −0.02], P = .05), very preterm birth (−0.14 percentage points [95% CI, −0.26 to −0.02], P = .03), low birth weight (−0.53 percentage points [95% CI, −0.96 to −0.10], P = .02), and very low birth weight (−0.13 percentage points [95% CI, −0.25 to −0.01], P = .04) (Table 3). There were no changes in relative disparities for Hispanic infants, indicated by no statistically significant DDD estimates for outcomes among Hispanic infants relative to white infants (Table 3).

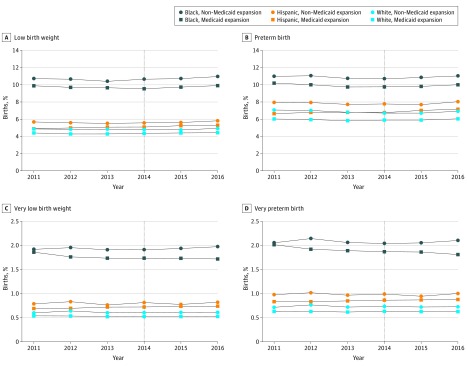

The Figure displays trends in the 4 birth outcomes stratified by race/ethnicity and by Medicaid expansion status. This Figure was used to visualize trends across the study period as well as whether trends were parallel prior to the expansion date, which was formally tested using linear indicator variables in the DID and DDD models. The DDD comparison of relative disparities in rates of low birth weight between black and white infants as well as 2 DID comparisons among outcomes in black infants (preterm birth and low birth weight) failed the parallel trends test; however, all other significant DID and DDD comparisons in the primary analyses passed this test (Table 3 and Table 4). Line charts for rates pooled among all races/ethnicities and for the subgroups are available in eFigures 6, 7, and 8 in the Supplement.

Figure. Trends in Unadjusted Rates of Low Birth Weight and Preterm Birth Outcomes in Medicaid Expansion and Nonexpansion States by Race/Ethnicity.

Data are from the Vital Statistics Birth Data File (2011-2016). Outcomes were calculated among 8 244 924 births to white women, 2 201 658 births to black women, and 3 944 665 births to Hispanic women. The vertical dotted line indicates the date of expansion for most expansion states on January 1, 2014. Three states included in the analyses (Alaska, Louisiana, and Pennsylvania) expanded at a later date (see eTable 2 in the Supplement for dates).

Table 4. Unadjusted and Adjusted Changes in Birth Outcomes Associated With Medicaid Expansion Among Medicaid-Covered Births and Medicaid-Covered Births to Women With at Most a High School Degreea,b.

| Medicaid-Covered Births | Medicaid-Covered Births to Women With at Most a High School Degree | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Difference-in-Differencesc | Difference-in-Difference-in-Differencesc | Difference-in-Differencesc | Difference-in-Difference-in-Differencesc | |||||||||

| Percentage Points | P Value | Percentage Points | P Value | Percentage Points | P Value | Percentage Points | P Value | |||||

| Unadjusted (95% CI) |

Adjusted (95% CI) |

Unadjusted (95% CI) |

Adjusted (95% CI) |

Unadjusted (95% CI) |

Adjusted (95% CI) |

Unadjusted (95% CI) |

Adjusted (95% CI) |

|||||

| Overall | ||||||||||||

| No. | 6 660 476 | 1 721 283 | ||||||||||

| Preterm | −0.19 (−0.27 to −0.11) | −0.06 (−0.24 to 0.11) | .49 | −0.17 (−0.35 to 0.00) | −0.14 (−0.37 to 0.09) | .25 | ||||||

| Very preterm | −0.08 (−0.11 to −0.05) | −0.05d (−0.11 to 0.02) | .17 | −0.04 (−0.11 to 0.03) | −0.01d (−0.08 to 0.06) | .77 | ||||||

| Low birth weight | −0.33 (−0.41 to −0.25) | −0.12 (−0.29 to 0.04) | .15 | −0.38 (−0.54 to −0.22) | −0.26 (−0.44 to −0.08) | .008 | ||||||

| Very low birth weight | −0.08 (−0.11 to −0.05) | −0.04 (−0.10 to 0.01) | .11 | −0.02 (−0.09 to 0.04) | 0.01d (−0.05 to 0.07) | .87 | ||||||

| Non-Hispanic White Infants | ||||||||||||

| No. | 2 468 731 | 465 678 | ||||||||||

| Preterm | −0.12 (−0.25 to 0.01) | −0.02 (−0.22 to 0.17) | 0.82 | −0.26 (−0.60 to 0.07) | −0.08 (−0.46 to 0.30) | .68 | ||||||

| Very preterm | −0.02 (−0.07 to 0.02) | −0.03 (−0.09 to 0.02) | 0.26 | 0.05 (−0.07 to 0.17) | 0.06 (−0.03 to 0.14) | .21 | ||||||

| Low birth weight | −0.13 (−0.25 to −0.01) | −0.02d (−0.20 to 0.15) | 0.79 | −0.27 (−0.59 to 0.04) | −0.10 (−0.45 to 0.25) | .58 | ||||||

| Very low birth weight | −0.03 (−0.08 to 0.01) | −0.05d (−0.09 to −0.01) | 0.03 | 0.05 (−0.07 to 0.16) | 0.02 (−0.07 to 0.12) | .62 | ||||||

| Non-Hispanic Black Infants | ||||||||||||

| No. | 1 449 904 | 3 918 635 | 300 190 | 765 868 | ||||||||

| Preterm | −0.84 (−1.04 to −0.63) | −0.34 (−0.72 to 0.04) | .09 | −0.71 (−0.96 to −0.47) | −0.47 (−0.81 to −0.12) | .01 | −1.30 (−1.78 to −0.82) | −0.51 (−1.03 to 0.02) | .07 | −1.03 (−1.62 to −0.45) | −0.46 (−1.02 to 0.10) | .12 |

| Very preterm | −0.22 (−0.31 to −0.13) | −0.21d (−0.37 to −0.04) | .02 | −0.20 (−0.30 to −0.09) | −0.20 (−0.36 to −0.03) | .03 | −0.39 (−0.60 to −0.17) | −0.32d (−0.56 to −0.09) | .01 | −0.44 (−0.69 to −0.19) | −0.38 (−0.62 to −0.13) | .005 |

| Low birth weight | −0.94 (−1.14 to −0.74) | −0.53 (−0.88 to −0.17) | .01 | −0.81 (−1.05 to −0.57) | −0.68 (−1.16 to −0.21) | .008 | −1.69 (−2.16 to −1.22) | −1.09 (−1.57 to −0.61) | <.001 | −1.41 (−1.98 to −0.85) | −1.01 (−1.55 to −0.47) | .001 |

| Very low birth weight | −0.20 (−0.29 to −0.11) | −0.19d (−0.33 to −0.05) | .01 | −0.16 (−0.26 to −0.07) | −0.16 (−0.32 to 0.00) | .05 | −0.38 (−0.59 to −0.17) | −0.33d (−0.57 to −0.10) | .01 | −0.43 (−0.66 to −0.19) | −0.36 (−0.60 to −0.13) | .004 |

| Hispanic Infants | ||||||||||||

| No. | 2 355 722 | 4 824 453 | 841 868 | 1 307 546 | ||||||||

| Preterm | 0.34 (0.20 to 0.48) | −0.02 (−0.20 to 0.17) | .86 | 0.46 (0.27 to 0.65) | 0.13d (−0.07 to 0.34) | .20 | 0.39 (0.14 to 0.64) | −0.07d (−0.29 to 0.16) | .57 | 0.66 (0.24 to 1.07) | 0.14d (−0.31 to 0.60) | .54 |

| Very preterm | 0.03 (−0.02 to 0.08) | −0.04 (−0.10 to 0.02) | .22 | 0.06 (−0.01 to 0.12) | 0.02d (−0.08 to 0.13) | .66 | 0.07 (−0.02 to 0.17) | 0.01 (−0.06 to 0.08) | .79 | 0.02 (−0.13 to 0.17) | −0.03d (−0.19 to 0.12) | .68 |

| Low birth weight | 0.28 (0.16 to 0.40) | 0.01d (−0.17 to 0.20) | .90 | 0.41 (0.23 to 0.58) | 0.11d (−0.13 to 0.35) | .38 | 0.26 (0.05 to 0.47) | 0.01d (−0.32 to 0.35) | .94 | 0.53 (0.16 to 0.91) | 0.15d (−0.39 to 0.69) | .58 |

| Very low birth weight | 0.01 (−0.03 to 0.06) | −0.02 (−0.09 to 0.04) | .45 | 0.05 (−0.01 to 0.11) | 0.02d (−0.06 to 0.10) | .57 | 0.10 (0.02 to 0.19) | 0.07 (0.01 to 0.13) | .03 | 0.06 (−0.08 to 0.19) | 0.02d (−0.12 to 0.16) | .77 |

Birth outcomes included preterm birth (<37 weeks’ gestation), very preterm birth (<32 weeks’ gestation), low birth weight (<2500 g), and very low birth weight (<1500 g).

Medicaid expansion and nonexpansion states are listed in footnote “b” of Table 1.

Coefficients were calculated using linear regression models with estimates multiplied by 100 to provide percentage point differences. Adjusted difference-in-differences and adjusted difference-in-difference-in-differences regressions were adjusted for all state-level and individual-level characteristics outlined in Tables 1 and 2 as well as for state-level dummy variables with standard errors clustered at the state level. As the difference-in-difference-in-differences analyses compare minority infants with white infants there are no difference-in-difference-in-differences estimates for the overall group or for the white infant category.

Indicates outcome in adjusted difference-in-differences or difference-in-difference-in-differences regression that does not pass the parallel trends test.

Table 4 provides the DID and DDD estimates for the 2 Medicaid-covered subgroups. Relative disparities among black infants were reduced for all 4 outcomes among Medicaid-covered births (preterm birth: −0.47 percentage points [95% CI, −0.81 to −0.12], P = .01; very preterm birth: −0.20 percentage points [95% CI, −0.36 to −0.03], P = .03; low birth weight: −0.68 percentage points [95% CI, −1.16 to −0.21], P = .008; and very low birth weight: −0.16 percentage points [95% CI, −0.32 to 0.00], P = .05) and 3 outcomes among Medicaid-covered births to women with at most a high school degree (very preterm birth: −0.38 percentage points [95% CI, −0.62 to −0.13], P = .005; low birth weight: −1.01 percentage points [95% CI, −1.55 to −0.47], P = .001; and very low birth weight: −0.36 percentage points [95% CI, −0.60 to −0.13], P = .004) (Table 4). One DID outcome among white infants in the Medicaid-covered births subgroup (very low birth weight) and 2 DID outcomes among black infants in both Medicaid-covered subgroups (very preterm birth and very low birth weight) failed the parallel trends test. There were no statistically significant DDD estimates among Hispanic infants in either subgroup (Table 4).

The primary findings from this study were quantitatively similar to those from robustness checks including a 1-year lag after expansion (eTables 3 and 4 in the Supplement) and changing state exclusion criteria (eTables 5, 6, and 7 in the Supplement). There was no evidence that differential changes in specific mechanisms, such as prenatal care initiation in the first trimester or prepregnancy diabetes, explained the reduction in disparities between black and white infants in the study (eTable 8 in the Supplement).

Discussion

This study evaluated whether Medicaid expansion was associated with changes in rates of preterm birth and low birth weight, and found that there were no differences in the change in birth outcomes between expansion and nonexpansion. However, the study found greater reductions in rates of low birth weight and preterm birth outcomes among black infants in expansion states relative to white infants in expansion states, with no significant change in disparities among Hispanic infants.

Black infants die of complications associated with prematurity and low birth weight at 3.9 times the rate of white infants (257.6 vs 66.3 per 100 000 live births in 2016).27 Reducing the rates of low birth weight and preterm birth among black infants has been suggested as the primary mechanism for decreasing inequities in infant mortality.28 A previous evaluation of infant mortality in Medicaid expansion relative to nonexpansion states found a greater decline among black infants compared with white or Hispanic infants.13 The reduction in relative disparities in low birth weight and prematurity among black infants in expansion states found in the current study provide a potential explanation for the greater decline in infant mortality for black infants.

An evaluation of the association of Massachusetts health care reform with infant mortality and low birth weight found no improvement.29 The findings from the Massachusetts study29 may differ because the percentage of black individuals in many Medicaid expansion states, such as the District of Columbia or Louisiana (46% and 32%, respectively, in 2017) is higher than the percentage in Massachusetts (7%).30 Evaluations of the Medicaid expansions in the 1980s and 1990s found improvements in prenatal care use and mixed evidence regarding improvements in infant outcomes.31 The findings here suggest that earlier and continual access to insurance coverage may provide an important opportunity for improving infant outcomes. Because low birth weight and premature births are highly related to complex medical comorbidities throughout childhood and into adulthood, the implications of the improvements associated with Medicaid expansion could potentially be associated with reduced disparities in chronic conditions across the life course.28,32,33

Despite the reductions in disparities for black infants in expansion states, this study did not find improvements for Hispanic infants. While some DDD coefficients for Hispanic infants were positive, these findings were not significant, and many failed to meet the parallel trends assumption. Reasons for the significant increases in unadjusted rates among Hispanic infants in expansion states remain unclear.

Limitations

This study has several limitations. First, the Birth Data Files database consists of administrative data, which may have missing data or lack information on maternal factors potentially related to birth outcomes. Because records with missing data were excluded from the study, missing data could result in selection bias; however, there was no significant difference in the percentage of births excluded from Medicaid expansion and nonexpansion states. Additional variables, such as family income, may provide more accurate subgroups or covariates in regression models. Birth certificate information is collected across multiple settings, with the potential for information misclassification; however, this was mitigated with clustered standard errors and state dummy variables in DID and DDD comparisons. Studies have shown high validity and reliability for birth weight and moderate reliability for gestational age.34,35 To address the concerns of gestational age estimation, this study additionally included very preterm birth, which may be less sensitive to misclassification,36 as well as birth weight, which is not sensitive to the gestational age estimates.

Second, it may take time for the benefits of health insurance coverage to improve maternal health and access to care. Previous studies have found greater improvements in later years after Medicaid expansion37,38; however, including a 1-year lag after expansion (eTables 3 and 4 in the Supplement) did not meaningfully change the overall conclusions of this study.

Third, parallel trends between Medicaid expansion and nonexpansion states are required for valid conclusions from DID or DDD analyses. In the primary analyses reported in this study, 1 statistically significant DDD finding and 2 significant DID findings in the subpopulation of black infants failed to meet the parallel trends test and should be interpreted with caution.

Conclusions

Based on data from 2011-2016, state Medicaid expansion was not significantly associated with differences in rates of low birth weight or preterm birth outcomes overall, although there were significant improvements in relative disparities for black infants compared with white infants in states that expanded Medicaid vs those that did not.

eMethods. Covariate Variables for Difference-in-Differences and Difference-in-Difference-Differences Models

eTable 1. State Categorization of Medicaid Expansion and Adoption of the 2003 Revised Birth Certificate

eTable 2. Timing of State Adoption of 2003 Revised Birth Certification and for Medicaid Expansion

eTable 3. Adjusted Difference-in-Differences for the Association of Medicaid Expansion With Changes in Birth Outcomes, Sensitivity Analysis With Births During 12-Months Postexpansion Removed

eTable 4. Adjusted Difference-in-Difference-in-Differences Estimates for the Association of Medicaid Expansion With Changes in Birth Outcomes, Sensitivity Analysis With Births During 12-Months Post expansion Removed

eTable 5. Difference-in-differences and difference-in-difference-in-differences estimates for the Association of Medicaid Expansion With Changes Birth Outcomes, State Classification Sensitivity Analyses Excluding States That Adopted 2003 Revised Certificate in 2012 or 2013

eTable 6. Difference-in-Differences and Difference-in-Difference-in-Differences Estimates for the Association of Medicaid Expansion With Changes Birth Outcomes, State Classification Sensitivity Analyses Excluding States With Medicaid Expansion After January 1, 2014

eTable 7. Difference-in-Differences and Difference-in-Difference-in-Differences Estimates for the Association of Medicaid Expansion With Changes Birth Outcomes, State Classification Sensitivity Analyses Including Waiver States

eTable 8. Adjusted Difference-in-Differences and Difference-in-Difference-in-Differences Estimates for the Association of Medicaid Expansion With Birth Outcome Mechanisms

eFigure 1. Exclusion Chart Describing the Number and Percent of Births Excluded to Reach the Final Study Sample

eFigure 2. Relative Percent Change in Unadjusted Rates of Low Birth Weight Prior to Medicaid Expansion and Post-Medicaid Expansion Among Expansion and Nonexpansion States, by Subgroup

eFigure 3. Relative Percent Change in Unadjusted Rates of Very Low Birth Weight Prior to Medicaid Expansion and Post-Medicaid Expansion Among Expansion and Non-expansion States, by Subgroup

eFigure 4. Relative Percent Change in Unadjusted Rates of Preterm Birth Outcomes Prior to Medicaid Expansion and Post-Medicaid Expansion Among Expansion and Nonexpansion States, by Subgroup

eFigure 5. Relative Percent Change in Unadjusted Rates of Very Preterm Birth Outcomes Prior to Medicaid Expansion and Post-Medicaid Expansion Among Expansion and Nonexpansion States, by Subgroup

eFigure 6. Rates of Unadjusted Birth Outcomes Among Births to Women of All Races/Ethnicities, by Expansion Status

eFigure 7. Rates of Unadjusted Birth Outcomes Among Births to Women of All Races/Ethnicities, by Expansion Status, Subgroup of Medicaid-Funded Births

eFigure 8. Rates of Unadjusted Birth Outcomes Among Births to Women of All Races/Ethnicities, by Expansion Status, Subgroup of Medicaid-Funded Births to Women With at Most a High School Degree

References

- 1.Matthews TJ, MacDorman MF, Thoma ME. Infant mortality statistics from the 2013 period linked birth/infant death data set. Natl Vital Stat Rep. 2015;64(9):1-30. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Behrman RE, Butler AS; Institute of Medicine, Committee on Understanding Premature Birth and Assuring Healthy Outcomes . Preterm Birth: Causes, Consequences, and Prevention. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2007. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bhutta AT, Cleves MA, Casey PH, Cradock MM, Anand KJ. Cognitive and behavioral outcomes of school-aged children who were born preterm: a meta-analysis. JAMA. 2002;288(6):728-737. doi: 10.1001/jama.288.6.728 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.de Kieviet JF, Piek JP, Aarnoudse-Moens CS, Oosterlaan J. Motor development in very preterm and very low-birth-weight children from birth to adolescence: a meta-analysis. JAMA. 2009;302(20):2235-2242. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.1708 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.D’Onofrio BM, Class QA, Rickert ME, Larsson H, Långström N, Lichtenstein P. Preterm birth and mortality and morbidity: a population-based quasi-experimental study. JAMA Psychiatry. 2013;70(11):1231-1240. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2013.2107 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Delnord M, Hindori-Mohangoo AD, Smith LK, et al. ; Euro-Peristat Scientific Committee . Variations in very preterm birth rates in 30 high-income countries: are valid international comparisons possible using routine data? BJOG. 2017;124(5):785-794. doi: 10.1111/1471-0528.14273 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.MacDorman MF, Matthews TJ, Mohangoo AD, Zeitlin J. International comparisons of infant mortality and related factors: United States and Europe, 2010. Natl Vital Stat Rep. 2014;63(5):1-6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Murphy SL, Mathews TJ, Martin JA, Minkovitz CS, Strobino DM. Annual Summary of Vital Statistics: 2013-2014. Pediatrics. 2017;139(6):e20163239. doi: 10.1542/peds.2016-3239 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Martin JA, Hamilton BE, Osterman MJK, Driscoll AK, Drake P. Births: final data for 2017. Natl Vital Stat Rep. 2018;67(8):1-50. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Johnson K, Applegate M, Gee RE. Improving Medicaid: three decades of change to better serve women of childbearing age. Clin Obstet Gynecol. 2015;58(2):336-354. doi: 10.1097/GRF.0000000000000115 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Daw JR, Hatfield LA, Swartz K, Sommers BD. Women in the United States experience high rates of coverage ‘churn’ in months before and after childbirth. Health Aff (Millwood). 2017;36(4):598-606. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2016.1241 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Shah SI, Brumberg HL. Predictions of the affordable care act’s impact on neonatal practice. J Perinatol. 2016;36(8):586-592. doi: 10.1038/jp.2016.93 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bhatt CB, Beck-Sagué CM. Medicaid expansion and infant mortality in the United States. Am J Public Health. 2018;108(4):565-567. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2017.304218 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.McMorrow S, Long SK, Kenney GM, Anderson N. Uninsurance disparities have narrowed for black and Hispanic adults under the Affordable Care Act. Health Aff (Millwood). 2015;34(10):1774-1778. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2015.0757 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.National Center for Health Statistics NCHS’ Vital Statistics Natality Birth Data. http://www.nber.org/data/vital-statistics-natality-data.html. Accessed October 1, 2018.

- 16.Kaestner R, Garrett B, Chen J, Gangopadhyaya A, Fleming C. Effects of ACA Medicaid expansions on health insurance coverage and labor supply. J Policy Anal Manage. 2017;36(3):608-642. doi: 10.1002/pam.21993 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Simon K, Soni A, Cawley J. The impact of health insurance on preventive care and health behaviors: evidence from the first two years of the ACA Medicaid expansions. J Policy Anal Manage. 2017;36(2):390-417. doi: 10.1002/pam.21972 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Courtemanche Ch, Marton J, Ukert B, Yelowitz A, Zapata D. Early impacts of the Affordable Care Act on health insurance coverage in Medicaid expansion and non-expansion states. J Policy Anal Manage. 2017;36(1):178-210. doi: 10.1002/pam.21961 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kaiser Family Foundation State health facts. Status of state action on the Medicaid expansion decision. https://www.kff.org/health-reform/state-indicator/state-activity-around-expanding-medicaid-under-the-affordable-care-act/. Accessed February 1, 2019.

- 20.Armstrong J. Women’s Health in the age of patient protection and the Affordable Care Act. Clin Obstet Gynecol. 2015;58(2):323-335. doi: 10.1097/GRF.0000000000000096 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sommers BD, Blendon RJ, Orav EJ, Epstein AM. Changes in utilization and health among low-income adults after Medicaid expansion or expanded private insurance. JAMA Intern Med. 2016;176(10):1501-1509. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2016.4419 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Antonisse L, Garfield R, Rudowitz R, Artiga S The effects of Medicaid expansion under the ACA: updated findings from a literature review. Kaiser Family Foundation. https://collections.nlm.nih.gov/master/borndig/101707525/Issue-Brief-The-Effects-of-Medicaid-Expansion-Under-the-ACA-Updated-Findings.pdf. Published February 2017. Accessed October 1, 2018.

- 23.Gonzales S, Sommers BD. Intra-ethnic coverage disparities among Latinos and the effects of health reform. Health Serv Res. 2018;53(3):1373-1386. doi: 10.1111/1475-6773.12733 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yue D, Rasmussen PW, Ponce NA. Racial/ethnic differential effects of Medicaid expansion on health care access. Health Serv Res. 2018;53(5):3640-3656. doi: 10.1111/1475-6773.12834 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Karaca-Mandic P, Norton EC, Dowd B. Interaction terms in nonlinear models. Health Serv Res. 2012;47(1, pt 1):255-274. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2011.01314.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ryan AM, Burgess JF Jr, Dimick JB. Why we should not be indifferent to specification choices for difference-in-differences. Health Serv Res. 2015;50(4):1211-1235. doi: 10.1111/1475-6773.12270 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Xu J, Murphy SL, Kochanek KD, Bastian B, Arias E. Deaths: final data for 2016. Natl Vital Stat Rep. 2018;67(5):1-76. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Riddell CA, Harper S, Kaufman JS. Trends in differences in US mortality rates between black and white infants. JAMA Pediatr. 2017;171(9):911-913. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2017.1365 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Boudreaux MH, Dagher RK, Lorch SA. The association of health reform and infant health: evidence from Massachusetts. Health Serv Res. 2017;53(4):2406-2424. doi: 10.1111/1475-6773.12779 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation Population distribution by race/ethnicity. https://www.kff.org/other/state-indicator/distribution-by-raceethnicity/. Published 2017. Accessed October 1, 2018.

- 31.Howell EM. The impact of the Medicaid expansions for pregnant women: a synthesis of the evidence. Med Care Res Rev. 2001;58(1):3-30. doi: 10.1177/107755870105800101 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lu MC, Kotelchuck M, Hogan V, Jones L, Wright K, Halfon N. Closing the black-white gap in birth outcomes: a life-course approach. Ethn Dis. 2010;20(1)(suppl 2):S2-S62, 76. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Braveman P, Barclay C. Health disparities beginning in childhood: a life-course perspective. Pediatrics. 2009;124(suppl 3):S163-S175. doi: 10.1542/peds.2009-1100D [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Roohan PJ, Josberger RE, Acar J, Dabir P, Feder HM, Gagliano PJ. Validation of birth certificate data in New York State. J Community Health. 2003;28(5):335-346. doi: 10.1023/A:1025492512915 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Northam S, Knapp TR. The reliability and validity of birth certificates. J Obstet Gynecol Neonatal Nurs. 2006;35(1):3-12. doi: 10.1111/j.1552-6909.2006.00016.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.DeFranco EA, Lian M, Muglia LA, Schootman M. Area-level poverty and preterm birth risk: a population-based multilevel analysis. BMC Public Health. 2008;8(1):316. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-8-316 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wehby GL, Lyu W. The impact of the ACA Medicaid expansions on health insurance coverage through 2015 and coverage disparities by age, race/ethnicity, and gender. Health Serv Res. 2018;53(2):1248-1271. doi: 10.1111/1475-6773.12711 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sommers BD, Maylone B, Blendon RJ, Orav EJ, Epstein AM. Three-year impacts of the Affordable Care Act: improved medical care and health among low-income adults. Health Aff (Millwood). 2017;36(6):1119-1128. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2017.0293 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

eMethods. Covariate Variables for Difference-in-Differences and Difference-in-Difference-Differences Models

eTable 1. State Categorization of Medicaid Expansion and Adoption of the 2003 Revised Birth Certificate

eTable 2. Timing of State Adoption of 2003 Revised Birth Certification and for Medicaid Expansion

eTable 3. Adjusted Difference-in-Differences for the Association of Medicaid Expansion With Changes in Birth Outcomes, Sensitivity Analysis With Births During 12-Months Postexpansion Removed

eTable 4. Adjusted Difference-in-Difference-in-Differences Estimates for the Association of Medicaid Expansion With Changes in Birth Outcomes, Sensitivity Analysis With Births During 12-Months Post expansion Removed

eTable 5. Difference-in-differences and difference-in-difference-in-differences estimates for the Association of Medicaid Expansion With Changes Birth Outcomes, State Classification Sensitivity Analyses Excluding States That Adopted 2003 Revised Certificate in 2012 or 2013

eTable 6. Difference-in-Differences and Difference-in-Difference-in-Differences Estimates for the Association of Medicaid Expansion With Changes Birth Outcomes, State Classification Sensitivity Analyses Excluding States With Medicaid Expansion After January 1, 2014

eTable 7. Difference-in-Differences and Difference-in-Difference-in-Differences Estimates for the Association of Medicaid Expansion With Changes Birth Outcomes, State Classification Sensitivity Analyses Including Waiver States

eTable 8. Adjusted Difference-in-Differences and Difference-in-Difference-in-Differences Estimates for the Association of Medicaid Expansion With Birth Outcome Mechanisms

eFigure 1. Exclusion Chart Describing the Number and Percent of Births Excluded to Reach the Final Study Sample

eFigure 2. Relative Percent Change in Unadjusted Rates of Low Birth Weight Prior to Medicaid Expansion and Post-Medicaid Expansion Among Expansion and Nonexpansion States, by Subgroup

eFigure 3. Relative Percent Change in Unadjusted Rates of Very Low Birth Weight Prior to Medicaid Expansion and Post-Medicaid Expansion Among Expansion and Non-expansion States, by Subgroup

eFigure 4. Relative Percent Change in Unadjusted Rates of Preterm Birth Outcomes Prior to Medicaid Expansion and Post-Medicaid Expansion Among Expansion and Nonexpansion States, by Subgroup

eFigure 5. Relative Percent Change in Unadjusted Rates of Very Preterm Birth Outcomes Prior to Medicaid Expansion and Post-Medicaid Expansion Among Expansion and Nonexpansion States, by Subgroup

eFigure 6. Rates of Unadjusted Birth Outcomes Among Births to Women of All Races/Ethnicities, by Expansion Status

eFigure 7. Rates of Unadjusted Birth Outcomes Among Births to Women of All Races/Ethnicities, by Expansion Status, Subgroup of Medicaid-Funded Births

eFigure 8. Rates of Unadjusted Birth Outcomes Among Births to Women of All Races/Ethnicities, by Expansion Status, Subgroup of Medicaid-Funded Births to Women With at Most a High School Degree