Abstract

Background and Purpose

The endocannabinoids anandamide and 2‐arachidonoylglycerol (2‐AG) bind to CB1 and CB2 cannabinoid receptors in the brain and modulate the mesolimbic dopaminergic pathway. This neurocircuitry is engaged by psychostimulant drugs, including cocaine. Although CB1 receptor antagonism and CB2 receptor activation are known to inhibit certain effects of cocaine, they have been investigated separately. Here, we tested the hypothesis that there is a reciprocal interaction between CB1 receptor blockade and CB2 receptor activation in modulating behavioural responses to cocaine.

Experimental Approach

Male Swiss mice received i.p. injections of cannabinoid‐related drugs followed by cocaine, and were then tested for cocaine‐induced hyperlocomotion, c‐Fos expression in the nucleus accumbens and conditioned place preference. Levels of endocannabinoids after cocaine injections were also analysed.

Key Results

The CB1 receptor antagonist, rimonabant, and the CB2 receptor agonist, JWH133, prevented cocaine‐induced hyperlocomotion. The same results were obtained by combining sub‐effective doses of both compounds. The CB2 receptor antagonist, AM630, reversed the inhibitory effects of rimonabant in cocaine‐induced hyperlocomotion and c‐Fos expression in the nucleus accumbens. Selective inhibitors of anandamide and 2‐AG hydrolysis (URB597 and JZL184, respectively) failed to modify this response. However, JZL184 prevented cocaine‐induced hyperlocomotion when given after a sub‐effective dose of rimonabant. Cocaine did not change brain endocannabinoid levels. Finally, CB2 receptor blockade reversed the inhibitory effect of rimonabant in the acquisition of cocaine‐induced conditioned place preference.

Conclusion and Implications

The present data support the hypothesis that CB1 and CB2 receptors work in concert with opposing functions to modulate certain addiction‐related effects of cocaine.

Linked Articles

This article is part of a themed section on 8th European Workshop on Cannabinoid Research. To view the other articles in this section visit http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/bph.v176.10/issuetoc

Abbreviations

- 2‐AG

2‐arachidonoylglycerol

- ACEA

arachidonoyl 2′‐chloroethylamide

- AM630

1‐[2‐(morpholin‐4‐yl)ethyl]‐2‐methyl‐3‐(4‐methoxybenzoyl)‐6‐iodoindole

- CPP

conditioned place preference

- FAAH

fatty acid amide hydrolase

- JWH133

(6aR,10aR)‐3‐(1,1‐dimethylbutyl)‐6a,7,10,10a‐tetrahydro‐6,6,9‐trimethyl‐6H‐dibenzo[b,d]pyran

- JZL184

4‐nitrophenyl‐4‐[bis(1,3‐benzodioxol‐5‐yl)(hydroxy)methyl]piperidine‐1‐carboxylate

- MAGL

monoacyl‐glycerol lipase

- Rimonabant

5‐(4‐chlorophenyl)‐1‐(2,4‐dichloro‐phenyl)‐4‐methyl‐N‐(piperidin‐1‐yl)‐1H‐pyrazole‐3‐carboxamide

- URB597

[3‐(3‐carbamoylphenyl)phenyl] N‐cyclohexylcarbamate

Introduction

Cannabinoid CB1 and CB2 receptors are responsible for the pharmacological effects of Δ9‐tetrahydrocannabinol, the main active compound from Cannabis sativa (Devane et al., 1988; Munro et al., 1993; Pertwee 2008). The endogenous ligands of these receptors, termed endocannabinoids, are the arachidonic acid derivatives, arachidonoyl ethanolamide (anandamide) and 2‐arachidonoylglycerol (2‐AG) (Devane et al., 1992; Sugiura et al., 1995). Each of these ligands has different degradation pathways. Fatty acid amid hydrolase (FAAH) is responsible mainly for anandamide hydrolysis, whereas the metabolism of 2‐AG is facilitated by monoacyl‐glycerol lipase (MAGL) (Cravatt et al., 1996; Dinh et al., 2002). Pharmacological and genetic manipulations of these enzymes regulate the levels and consequently the action of endocannabinoids (Petrosino and Di Marzo 2010; Batista et al., 2014).

Among the brain circuits modulated by endocannabinoids is the dopaminergic mesolimbic pathway, which is engaged by several drugs of abuse, including cocaine (Cheer et al., 2007). This drug inhibits dopamine uptake and facilitates dopamine receptor‐mediated signalling, increasing c‐Fos expression in the nucleus accumbens (Valjent et al., 2000; Zhang et al., 2004). The presence of the endocannabinoid system in the mesolimbic pathway is in agreement with the evidence that endocannabinoids modulate behavioural responses to cocaine (Maldonado et al., 2006). For instance, pharmacological blockade or genetic deletion of CB1 receptors inhibits the motor hyperactivity induced by this psychostimulant (Poncelet et al., 1999; Corbille et al., 2007; Li et al., 2009). Inhibition of CB1 receptor signalling also reversed cocaine self‐administration and responses in the conditioned place preference (CPP) paradigm (Soria et al., 2005; Xi et al., 2008; Yu et al., 2011). Moreover, blockade of CB1 receptors seems to modulate the neurochemical effects of cocaine, as cocaine‐induced increases in extracellular dopamine levels in the nucleus accumbens were inhibited following silencing of these receptors (Cheer et al., 2007; Corbille et al., 2007; Li et al., 2009).

Regarding the CB2 receptor, early evidence suggested that this receptor might be absent in brain and restricted to peripheral tissues (Munro et al., 1993). However, recent studies have challenged this view, detecting expression of CB2 receptors in some encephalic structures (Gong et al., 2006; Onaivi et al., 2008). Moreover, pharmacological and genetic interventions at this receptor result in behavioural changes, further indicating that this receptor is present and functional in the brain (Ortega‐Alvaro et al., 2011; Xi et al., 2011). In agreement, recent findings show that the CB2 receptor is involved in behavioural responses to cocaine, although its functions tend to oppose those ascribed for CB1 receptors. For example, activation of CB2 receptors attenuated cocaine‐induced hyperlocomotion, self‐administration and dopamine release in the nucleus accumbens (Xi et al., 2011; Zhang et al., 2014; Zhang et al., 2015; Zhang et al., 2017). Accordingly, transgenic mice overexpressing CB2 receptors have reduced cocaine self‐administration and motor sensitization (Aracil‐Fernandez et al., 2012).

Although several studies provide evidence for a role of the endocannabinoid system in the modulation of cocaine responses, a possible interaction between CB1 and CB2 receptors in this context remains to be investigated. Both receptors modulate the mesolimbic dopaminergic pathway in the ventral tegmental area (Zhang et al., 2014; Wang et al., 2015; Zhang et al., 2017). The CB1 receptor is expressed in GABAergic terminals projecting onto dopaminergic neurons, where its activation disinhibits the mesolimbic pathway (Wang et al., 2015). The CB2 receptor, on the other hand, has been identified in the dopaminergic cell bodies, in which they may exert inhibitory functions (Zhang et al., 2014; Zhang et al., 2017). Therefore, CB1 and CB2 receptors can be simultaneously activated by endocannabinoids at a given synapse in the ventral tegmental area, with opposing effects on dopaminergic activity.

On the basis of such evidence, the working hypothesis of this study was that endocannabinoids could either facilitate or inhibit the behavioural effects of cocaine through CB1 and CB2 receptors respectively. First, we investigated the role of each cannabinoid receptor and endocannabinoid in cocaine‐induced hyperlocomotion. Second, we hypothesized that blockade of CB1 receptors would ameliorate the effects of cocaine because endocannabinoids would then act predominantly on CB2 receptors. Thus, we tested if CB2 receptor antagonists would prevent the inhibitory effects of CB1 receptor antagonism on cocaine‐induced hyperlocomotion and c‐Fos expression in the nucleus accumbens. We also analysed the levels of brain endocannabinoids after cocaine injection. Finally, we extended this analysis to the rewarding effects of cocaine in the CPP test.

Methods

Compliance with design and statistical analysis requirements

This study complies with the design and statistical analysis requirements of the British Journal of Pharmacology (Curtis et al., 2018). Specific details regarding ethics, experimental designs and data analysis are provided in appropriate sections below.

Experimental animals

All animal care and experimental procedures were in accordance with the Brazilian Society of Neuroscience and Behaviour Guidelines for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals and were approved by the local ethics committee (CEUA–UFMG) under the protocol 242/2013. Animal studies are reported in compliance with the ARRIVE guidelines (Kilkenny et al., 2010; McGrath et al., 2010). Male Swiss mice (25–30 g) were group‐housed (5 per cage) in a room maintained at 25°C with a 12 h light/dark cycle (lights on at 8 a.m.). Food and water were available ad libitum. Each animal was used only once..

Role of the endocannabinoid system in cocaine‐induced hyperlocomotion

All the experiments were conducted in the light phase, between 8.00 a.m. and 16.00 p.m. in an isolated, sound‐attenuated room. The experiments measuring locomotion were carried out in a square open field (40 cm × 40 cm with a 50 cm high Plexiglas wall). The animals received injections of one of the cannabinoid‐related drugs and 20 min later were habituated in the open field for 10 min. Next, they received cocaine (20 mg·kg−1) injection and were immediately placed back in the open field. The distance moved was analysed for 10 min with the help of Any Maze software (Stoelting Co).

Roles of CB1 and CB2 receptors in cocaine‐induced c‐Fos expression

The animals were subjected to the same injection and behavioural protocols as described in the previous section. Two hours after exposure to the arena, the animals were anaesthetized with an overdose of urethane and perfused transcardially with saline (200 mL) followed by paraformaldehyde (4%) in 0.1 M phosphate buffer (150 mL, pH 7.4). Brains were removed and post‐fixed over 2 h in paraformaldehyde (4%) and stored for 36 h in 30% sucrose for cryoprotection. Coronal sections (40 μm) of nucleus accumbens core and shell, as identified with the help of the atlas of the mouse brain (Paxinos and Watson 1997), were obtained in a cryostat. The slices were stored in triplicate and processed for immunohistochemistry, as previously described (Vilela et al., 2015). Briefly, tissue sections were washed with phosphate buffer in saline and incubated overnight at room temperature with rabbit IgG antibody in phosphate buffer in saline (1:1000, from Santa Cruz, Dallas, TX, USA). The sections were washed in phosphate buffer in saline and incubated with a biotinylated anti‐rabbit IgG (1:1000, Santa Cruz, Dallas, TX, USA). Fos‐like immunoreactivity was revealed by the addition of the chromogen diaminobenzidine (Sigma, St. Louis, MO, USA) and visualized as a brown precipitate inside the neuronal nuclei. The images from the slices were captured with the auxiliary of the microscope (Zeiss, Oberkochen, Germany) and an observer blind to group assignment performed the analysis of the number of Fos‐like immune‐reactivity manually counted with the help of a computerized image analysis system (Image Pro‐Plus 4.0, Media Cybernetics). The nucleus accumbens sites were identified with the help of the atlas Paxinos and Watson (1997) at the anteroposterior (AP) localization from bregma AP = −1.18 mm, and one section from each animal for each group was evaluated.

Cocaine effects on endocannabinoid levels

LC–tandem MS was used to determine levels of the endogenous cannabinoids anandamide and 2‐AG in hippocampus, striatum and prefrontal cortex as described previously (Ford et al., 2011). Immediately after testing in the arena, animals were killed by decapitation, and regions of interest were immediately dissected and snap‐frozen on dry ice. Then, samples were homogenized in 400 μL of 100% acetonitrile containing deuterated internal standards (0.014 nmol AEA‐d8, 0.48 nmol 2‐AG‐d8). Homogenates were centrifuged at 14 000 g for 15 min at 4°C, and the supernatant was collected and evaporated to dryness in a centrifugal evaporator. Samples were resuspended in 40 μL of 65% acetonitrile and separated on a Zorbax® (Santa Clara, CA, USA) C18 column (150 × 0.5 mm internal diameter; Agilent Technologies Ltd, Cork, Ireland) by reversed‐phase gradient elution. Analyte detection was carried out in electrospray‐positive ionization and multiple reaction monitoring mode on an Agilent 1100 HPLC system coupled to a triple quadrupole 6460 mass spectrometer (Agilent Technologies Ltd). Quantification of each analyte was done by ratiometric analysis and expressed as pmol or nmol·g−1 (anandamide and 2‐AG, respectively) of tissue. The limit of quantification was 1.32 pmol·g−1 for anandamide and 12.1 pmol·g−1 for 2‐AG.

Roles of CB1 and CB2 receptors in cocaine‐induced CPP

Conditioned place preference (CPP) was assessed in an acrylic box consisting of two chambers of equal size (20 cm long, 15 wide and 10 cm high) with doors (5 × 5 cm) connecting them to a central compartment (6 cm long, 15 cm wide and 10 cm high). The walls of the lateral chambers had interspersed black and white stripes, and the floors consisted of removable metal surfaces. In one of the chambers (chamber A), the walls were painted with vertical stripes, and the floor consisted of a metal grid with parallel, equally‐spaced rods. The other (chamber B) had walls painted with horizontal stripes and a metal floor with circular holes. The light intensity was similar among the three compartments. The CPP protocol was based in previous studies (Yu et al., 2011; Almeida‐Santos et al., 2014). In the pre‐test phase (first day), each mouse was placed in the central compartment of the box, with the doors open, and could freely explore during 15 min. The time spent in each compartment was registered and automatically analysed with the AnyMaze software (Stoelting Co®). In the conditioning phase (days 2–7), the animals were randomly assigned to one of the experimental treatments. They received cocaine injections on days 2, 4 and 6 and were immediately confined to one of the chambers (drug‐paired side) for 30 min. On alternate days (3, 5 and 7), mice were injected with saline and confined to the other compartment of the chamber for 30 min. We designed a counterbalance protocol, meaning that each group contained animals receiving to cocaine injections in chamber A, but saline in chamber, as well as animals assigned to the opposite pairing. Cannabinoid antagonists were co‐administered on days 2, 4 and 6, 30 min before each cocaine injection. Finally, on the test phase (day 8), mice were tested for the expression of cocaine‐induced CPP under drug‐free conditions identical to those described in the preconditioning test. The CPP score was defined as the time spent in the drug‐paired chamber minus the time spent in the saline‐paired chamber.

Data and statistical analysis

Sample sizes appropriate for each type of experiment were estimated based on pilot studies and were calculated based on the equation (Eng, 2003): CI 95 = 1.96 s/√n, where CI stands for the confidence interval, 1.96 is the corresponding tabulated value for CI 95, s is the SD of the mean and n is the sample size. Sample sizes may differ slightly between groups in each experiment, as not all animals in a batch provided by the animal facility satisfied the criteria for the experiments (e.g. high body weight or age).

The animals were randomized for experimental treatments. The distances moved in the open field and the number of c‐Fos positive cells were subjected to ANOVA followed by the Newman–Keuls test. To test for a linear correlation, the individual values of distance moved and c‐Fos positive cells for each animal were subjected to the Pearson correlation analysis. Endocannabinoid levels were analysed by Student's t‐test. Drug effects on CPP were analysed by comparing CPP scores in the test session through ANOVA followed by the Newman–Keuls test. The level of significance was set at P < 0.05. Post hoc tests were run only if F achieved P < 0.05, and there is no significant variance in homogeneity. All data are presented as scattered dot plots, with the mean and SEM shown.

Materials

Cocaine hydrochloride (20 mg·kg−1, Merck, Kenylworth, NJ, USA) was dissolved in physiological saline. The CB1 receptor antagonist/inverse agonist, rimonabant (1, 3, and 10 mg·kg−1; Cayman Chemical, Ann Arbor, USA), was dissolved in cremophor–ethanol–saline (1:1:18, v/v). A similar solution was used to dissolve the CB1 receptor agonist arachidonoyl 2′‐chloroethylamide (ACEA, 5 mg·kg−1; Tocris, Bristol, UK), the FAAH inhibitor URB597, (0.1, 0.3 and 1.0 mg·kg−1; Cayman Chemical, Ann Arbor, USA) and the MAGL inhibitor JZL184 (1.0, 3.0 and 10 mg·kg−1; Cayman Chemical, Ann Arbor, USA). The CB2 receptor antagonist, AM630 (1, 3 and 10 mg·kg−1; Tocris, Bristol, UK), and the CB2 receptor agonist, JWH133 (1, 3 and 10 mg·kg−1; Cayman Chemical, Ann Arbor, USA), were dissolved in physiological saline containing Tween 80 (5%) and DMSO (5%). The solutions were prepared immediately before use and injected i.p. in a volume of 10 mL·kg−1.

Nomenclature of targets and ligands

Key protein targets and ligands in this article are hyperlinked to corresponding entries in http://www.guidetopharmacology.org, the common portal for data from the IUPHAR/BPS Guide to PHARMACOLOGY (Harding et al. 2018), and are permanently archived in the Concise Guide to PHARMACOLOGY 2017/18 (Alexander et al. 2017a,b)

Results

Role of the endocannabinoid system in cocaine‐induced hyperlocomotion

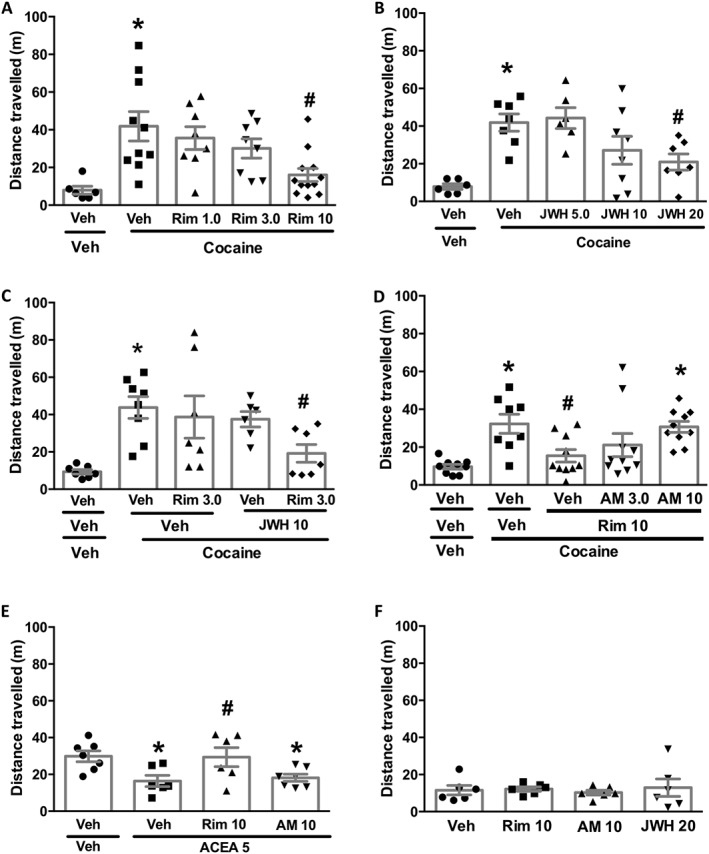

First, we tested the effects of CB1 receptor blockade on cocaine‐induced hyperlocomotion. A dose response curve with rimonabant (1, 3 and 10 mg·kg−1) revealed that this compound was effective at the highest dose (Figure 1A). To explore the role of the CB2 receptor, we tested the effects of the selective CB2 agonist, JWH133 (20 mg·kg−1) and found it to attenuate cocaine‐induced hyperlocomotion (Figure 1B)]. Next, we examined whether the combined administration of sub‐effective doses of these drugs would attenuate cocaine hyperlocomotion. A combination of rimonabant (3 mg·kg−1) and JWH133 (10 mg·kg−1) inhibited cocaine effects (Figure 1C). We also investigated if CB1 receptor blockade by rimonabant would shift endocannabinoid actions to CB2 receptors. Supporting this hypothesis, pretreatment with a CB2 receptor antagonist, AM‐630 (10 mg·kg−1), reversed the inhibitory effect of rimonabant (10 mg·kg−1) on hyperlocomotion induced by cocaine (Figure 1D). The next experiments were designed to check the selectivity of AM630 for the CB2 over the CB1 receptor at the current dose (10 mg·kg−1). If this is the case, rimonabant (10 mg·kg−1), but not AM630, would prevent the effects of a selective CB1 receptor agonist. Accordingly, only rimonabant prevented ACEA‐induced hypolocomotion (Figure 1E. Importantly, none of the cannabinoid‐related compounds, at the doses used, interfered with basal locomotion (Figure 1F)].

Figure 1.

Roles of CB1 and CB2 receptors in cocaine‐induced hyperlocomotion. (A) The CB1 receptor antagonist, rimonabant (Rim; 10 mg·kg−1), prevented the hyperlocomotion induced by cocaine 20 mg·kg−1 (n = 8, 10, 8, 8, 12). (B) The CB2 receptor agonist, JWH133 (JWH; 20 mg·kg−1), prevented cocaine‐induced hyperlocomotion (n = 7, 7, 7, 8, 8). (C) A combination of sub‐effective doses of rimonabant (3 mg·kg−1) and JWH133 (10 mg·kg−1) prevented cocaine hyperlocomotion (n = 7, 8, 7, 7, 8). (D) The CB2 receptor antagonist, AM630 (AM; 10 mg·kg−1), reversed the inhibitory effect of rimonabant (10 mg·kg−1) on cocaine‐induced hyperlocomotion (n = 8, 10, 8, 8, 12). (E) Rimonabant (10 mg·kg−1), but not AM630 (10 mg·kg−1), prevented ACEA (5 mg·kg−1)‐induced hypolocomotion (n = 7,6,6,7). (F) Rimonabant (10 mg·kg−1), AM630 (10 mg·kg−1) and JWH133 (20 mg·kg−1) did not interfere with basal locomotor activity as compared to the vehicle (Veh; cremophor–ethanol–saline, 1:1:18); n = 6. Data shown are individual values with means ± SEM; n as indicated. *P < 0.05, significantly different from vehicle‐vehicle group; # P < 0.05, significantly different from vehicle‐cocaine or vehicle‐ACEA groups; ANOVA followed by Newman–Keuls test.

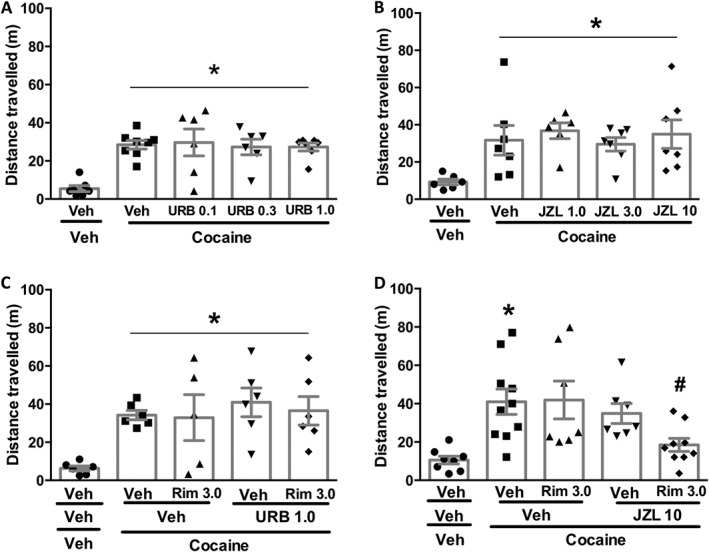

To evaluate the participation of endocannabinoids in modulation of cocaine‐induced responses, we injected animals with URB597 (0.1, 0.3 and 1.0 mg·kg−1) or JZL184 (1, 3 and 10 mg·kg−1), which inhibit anandamide and 2‐AG hydrolysis respectively. Neither URB597 (Figure 2A)] nor JZL184 (Figure 2B) modified the effects of cocaine. Inhibiting endocannabinoid hydrolysis might not prevent the effects of cocaine because they activated both cannabinoid receptors, which cancelled each other's effects. Thus, we hypothesized that a subthreshold dose of rimonabant (3 mg·kg−1) combined with an ineffective dose of endocannabinoid hydrolysis inhibitor would selectively facilitate CB2 receptor signalling and thus inhibit cocaine's effects. However, contrary to this prediction, combining rimonabant (3 mg·kg−1) with URB597 (1 mg·kg−1) failed to change responses to cocaine (Figure 2C). However, when the same subthreshold dose of rimonabant was combined with the2‐AG hydrolysis inhibitor, JZL184 (10 mg·kg−1), the hyperlocomotor effect of cocaine was prevented (Figure 2D)].

Figure 2.

Effect of inhibitors of endocannabinoid hydrolysis, alone or in combination with a subthreshold dose of the CB1 receptor antagonist, rimonabant, on cocaine‐induced hyperlocomotion. (A) URB597 (URB; 0.1, 0.3 and 1.0 mg·kg−1), the anandamide hydrolysis inhibitor, did not change cocaine effect (n = 7, 6, 8, 6, 8). (B) A similar pattern was observed after treatment with the 2‐AG hydrolysis inhibitor, JZL184 (JZL; 1.0, 3.0 and 10 mg·kg−1) (n = 6, 7, 6, 7, 7). (C) Combined treatment with a subthreshold dose of rimonabant (Rim; 3 mg·kg−1) and URB597(1 mg·kg−1) did not change cocaine‐induced hyperlocomotion (n = 7, 7, 6, 6, 7). (D) Combined treatment with a subthreshold dose of rimonabant (3 mg·kg−1), and JZL184 (10 mg·kg−1), prevented cocaine‐induced hyperlocomotion (n = 8,8,10,8,9). Data shown are individual values with means ± SEM; n as indicated. *P < 0.05, significantly different from vehicle‐vehicle; # P < 0.05, significantly different from vehicle‐cocaine group; ANOVA followed by Newman–Keuls test.

Roles of CB1 and CB2 receptors in cocaine‐induced c‐Fos expression

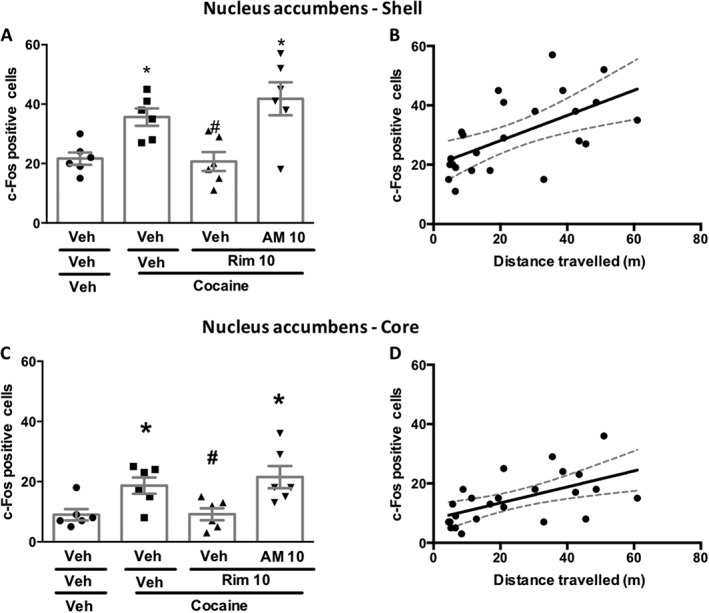

We then tested our hypothesis on the cellular effects of cocaine. In accordance with the behavioural results, rimonabant (10 mg·kg−1) prevented cocaine‐induced increases in c‐Fos expression in the nucleus accumbens, and pretreatment with AM‐630 (10 mg·kg−1) reversed this inhibitory effect. This occurred in both the shell (Figure 3A) and the core (Figure 3B) parts of the nucleus accumbens. The total distance moved correlated with the number of c‐Fos immunostained nuclei in the shell (Figure 2C) and the core [r = 0.5742, P < 0.05; Figure 2D]. Representative photomicrographs of c‐Fos expression are shown in Figure 4. Cannabinoid‐related compounds did not alter basal levels of c‐Fos counting. The values in the shell portion were as follows (mean ± SEM; n = 6 per group). Vehicle: 32 ± 4.7; rimonabant (10 mg·kg−1): 39.5 ± 3.8; AM630 (10 mg·kg−1): 30.5 ± 5.6. The values for c‐Fos counting in the core portion were as follows (mean ± SEM; n = 6 per group). Vehicle: 18.4 ± 3.1; rimonabant (10 mg·kg−1): 22.2 ± 4.2; AM630 (10 mg·kg−1): 17.1 ± 3.3.

Figure 3.

Opposing roles for CB1 and CB2 receptors on c‐Fos expression induced by cocaine. (A) Rimonabant (Rim; 10 mg·kg−1) prevented the increase in c‐Fos expression induced by cocaine (20 mg·kg−1) on the shell region of the nucleus accumbens, an effect reversed by previous treatment with AM630 (AM; 10 mg·kg−1) (n = 6/group). (B) The number of c‐Fos cells in the shell region of the nucleus accumbens correlated with the total distance moved in the open field. The best fit and confidence intervals are represented by continuous and dashed lines respectively. r = 0.6019, P < 0.05; n = 24. (C) Rimonabant (10 mg·kg−1) prevented cocaine‐induced increased in c‐Fos expression on the core portion of nucleus accumbens, an effect reversed by previous treatment with AM630 (n = 6/group). (D) The number of c‐Fos cells in the core regions of the nucleus accumbens correlated with the total distance moved in the open field The best fit and confidence intervals are represented by continuous and dashed lines respectively. r = 0.5742, P < 0.05 (n = 24). *P < 0.05, significantly different from vehicle‐vehicle; # P < 0.05, significantly different from vehicle‐cocaine group; ANOVA followed by Newman–Keuls test.

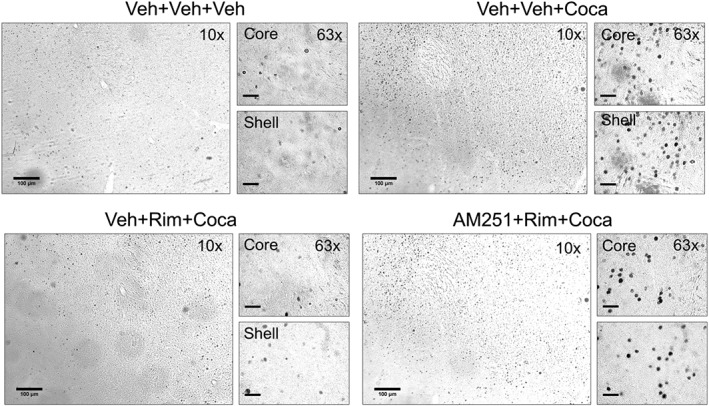

Figure 4.

Representative photomicrographs of coronal sections (40 μm) of the nucleus accumbens showing c‐Fos immunoreactivity. For each treatment, (vehicle,Veh; rimonabant, Rim; cocaine, Coca) the total area of this structure is presented at a 10× magnification, whereas the shell and core subregions are presented at a 63× magnification. c‐Fos positive cells are identified as dark dots. Scale bars: 100 μm.

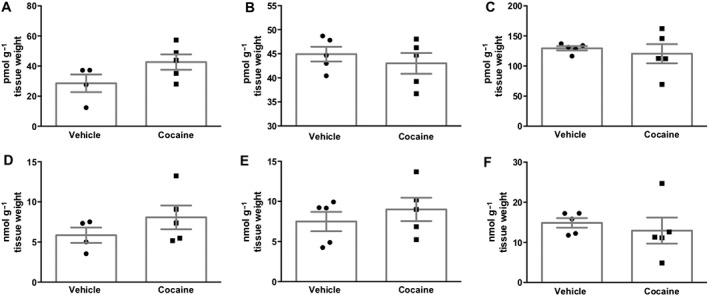

Cocaine effects on endocannabinoid levels

We also investigated whether endocannabinoid levels in the mesolimbic system were increased after cocaine administration. Cocaine (20 mg·kg−1) administration did not change anandamide levels in the striatum (Figure 5A), prefrontal cortex (Figure 5B) and hippocampus (Figure 5C). 2‐AG levels also remained unchanged in these regions: striatum (Figure 5D), prefrontal cortex (Figure 5E) and hippocampus (Figure 5F).

Figure 5.

Effect of cocaine on endocannabinoid levels. Treatment with cocaine (20 mg·kg−1) did not change the levels of anandamide in the (A) striatum, (B) hippocampus or (C) prefrontal cortex. Data shown are individual values with means ± SEM; n = 5. A similar lack of effect was observed for 2‐AG levels in these structures (D, E, and F). Data shown are individual values with means ± SEM; n = 5. Student's t‐test.

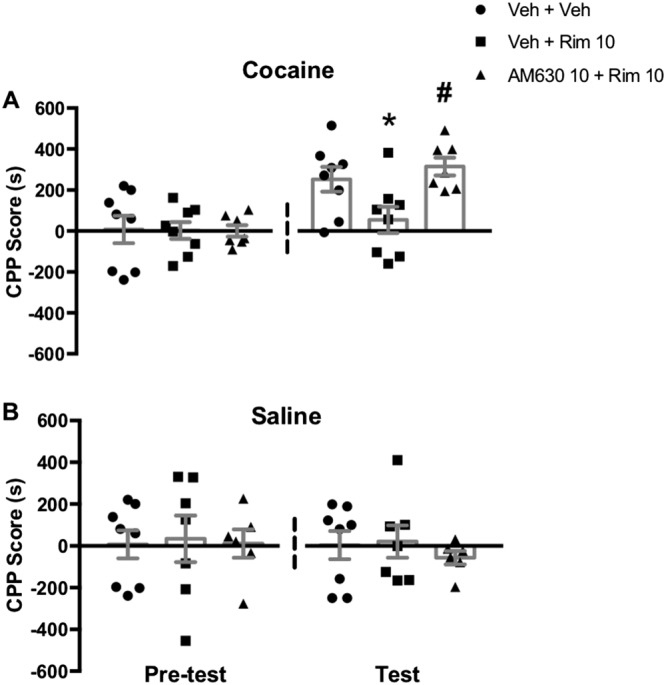

Roles of CB1 and CB2 receptors in cocaine‐induced CPP

We also tested if our hypothesis of opposing roles for CB1 and CB2 receptors would extend to the rewarding effect of cocaine. Thus, we confirmed that CB2 receptor antagonism would reverse the inhibitory effect of CB1 receptor antagonism on cocaine‐induced CPP (Figure 6A). ANOVA of CPP scores in the test session revealed a significant overall drug effect. Post hoc Newman–Keuls analysis showed that rimonabant pretreatment abolished the cocaine effect, as it prevented the increase in CPP score compared to the vehicle‐cocaine group. Consistent with our hypothesis, pre treatment with a CB2 receptor antagonist reversed the inhibitory effect of rimonabant. This result mimics our observation in cocaine‐induced hyperlocomotion. Rimonabant or AM630 did not change induced place preference or aversion on their own (Figure 6B).

Figure 6.

Effect of CB1 and CB2 receptor antagonism on cocaine‐induced CPP. (A) Rimonabant (Rim; 10 mg·kg−1), prevented cocaine‐induced place preference, an effect reversed by previous treatment with AM‐630 (10 mg·kg−1). Data shown are individual values with means ± SEM; n = 8,8,7. *P < 0.05, significantly different from vehicle‐vehicle‐cocaine group; # P < 0.05, significantly different from vehicle‐Rim‐cocaine group; ANOVA followed by Newman–Keuls test. (B) CB1 and CB2 receptor blockade did not induce either preference or aversion. Data shown are individual values with means ± SEM; n = 8, 7, 6; ANOVA followed by Newman–Keuls test.

Discussion

The present study provided evidence for a reciprocal interaction between CB1 receptor blockade and CB2 receptor activation in inhibiting behavioural responses to cocaine. In addition to studying each receptor separately, we have also found that the ameliorating effects of CB1 receptor antagonists was reversed by CB2 receptor antagonists. Thus, CB1 receptor antagonists inhibit cocaine effects, possibly because endocannabinoid actions are diverted to the CB2 receptor. The endocannabinoid involved in this mechanism might be 2‐AG, because a MAGL inhibitor reduced cocaine‐induced hyperlocomotion when combined with a low‐dose of a CB1 receptor antagonist.

Corroborating previous data, we observed that CB1 receptor blockade with rimonabant prevented various responses to cocaine. CB1 receptor antagonists are well‐known to inhibit behavioural and neurochemical responses to psychostimulant drugs (Cheer et al., 2007; Li et al., 2009; Hernandez et al., 2014; Mereu et al., 2015; Wang et al., 2015). However, their clinical applications are limited by their potential CNS side effects, such as anxiety and depression (Moreira and Crippa, 2009). More recently, the CB2 receptor agonists has been considered as a potential alternative, mainly after studies suggesting CB2 receptor expression in the brain and its function in inhibiting responses to drugs of abuse (Xi et al., 2011; Aracil‐Fernandez et al., 2012; Zhang et al., 2014; Zhang et al., 2015; Zhang et al., 2017). Accordingly, the present study shows that activation of CB2 receptors with JWH133 inhibited cocaine effects. In addition, a similar result was obtained by combining ineffective doses of a CB1 receptor antagonist and a CB2 receptor agonist. We also found that the CB2 receptor antagonist, AM630 (10 mg·kg−1), reversed the inhibitory effect of the CB1 receptor antagonist, rimonabant, in cocaine‐induced hyperlocomotion and c‐Fos expression in the nucleus accumbens. At this dose, AM630 is unlikely to bind significantly to CB1 receptors, as it did not interfere with the effect of ACEA, a selective CB1 receptor agonist. Finally, the effects on the distance moved correlated with the effects on c‐Fos expression in both the shell and core regions of the nucleus accumbens. These data reveal a functional interaction between subtypes of cannabinoid receptors in modulating cocaine responses, suggesting that CB1 receptor antagonists ameliorate cocaine effects by diverting endocannabinoid actions to the CB2 receptor. A possible site of action is the ventral tegmental area, where CB1 and CB2 receptors are proposed to be located in GABAergic terminals and dopaminergic cell bodies, respectively (Zhang et al., 2014; Wang et al., 2015; Zhang et al., 2017).

To investigate which endocannabinoid might be involved in this process, we tested selective inhibitors of anandamide and 2‐AG hydrolysis. However, selective inhibition of FAAH or MAGL failed to modify cocaine‐induced hyperlocomotion. In fact, these results are in agreement with previous data (Luque‐Rojas et al., 2013) and might be explained by a simultaneous activation of both CB1 and CB2 signalling, which modulates cocaine responses in opposite ways. Thus, to selectively increase activation of CB2 receptors by endocannabinoids, we administered an ineffective dose of rimonabant before the endocannabinoid hydrolysis inhibitors. Remarkably, treatment with an MAGL inhibitor, but not with a FAAH inhibitor, attenuated cocaine‐induced hyperlocomotion when CB1 receptors were blocked by low‐dose rimonabant. The possible explanation for this difference might depend on the distinct affinities and efficacies of anandamide and 2‐AG at cannabinoid receptors (Di Marzo and De Petrocellis, 2012). Anandamide exhibits higher affinity for CB1 , as compared to CB2 receptors, whereas the opposite seems to be the case for 2‐AG (Di Marzo and De Petrocellis, 2012). Similarly, as observed on a variety of in vitro functional assays, 2‐AG acts as a full agonist, whereas anandamide acts as a partial agonist at CB2 receptors (Sugiura et al., 2000). Therefore, the role of 2‐AG may depend on which cannabinoid receptor is predominantly activated. Previous studies found that 2‐AG mediates cocaine effects through CB1 receptors in the ventral tegmental area (Wang et al., 2015). The mechanism involves the inhibition of GABAergic terminals, with subsequent disinhibition of dopaminergic pathways that project to the nucleus accumbens (Zhang et al., 2014; Wang et al., 2015). The present study expands these mechanisms and proposes a new role of 2‐AG, showing that this endocannabioid may actually inhibit the effects of cocaine, if the CB1 receptors are blocked.

This effect occurred even though cocaine did not change the levels of anandamide and 2‐AG in hippocampus, striatum or prefrontal cortex. This finding is in agreement with earlier reports of no changes in endocannabinoid levels in response to cocaine (Gonzalez et al., 2002; Caille et al., 2007), although other authors have shown that cocaine injection did increase 2‐AG levels (Patel et al., 2003). Different experimental conditions may explain these discrepancies. Other important factors may be the time point and the technique to measure endocannabinoids. Finally, it may depend on the brain regions, as we have analysed not only the nucleus accumbens but also the whole striatum. Despite of these limitations, our data suggest that 2‐AG, but not anandamide, seems to be the endocannabinoid responsible for mediating increases in activation of CB2 receptors after blockade of CB1 receptors. The preferential role of CB2 receptors in mediating 2‐AG effects as compared to anandamide has also been observed in other behavioural responses. For instance, the anxiolytic‐like effect induced by 2‐AG hydrolysis inhibitors depend on activation of CB2 receptors, whereas the same effect induced by anandamide hydrolysis inhibitors is mediated mainly by CB1 receptors (Busquets‐Garcia et al., 2011).

To extend these results to the rewarding response to cocaine, we investigated the effects of cannabinoid antagonists in CPP. This test is relevant as it allows the investigation of the contextual memory mechanisms that trigger drug seeking (Cunningham et al., 2006). Previous studies showed that antagonism of CB1 receptors (Yu et al., 2011) and CB2 receptor agonists (Delis et al., 2017) inhibited cocaine‐induced CPP. Here, we hypothesized that the inhibitory effect of a CB1 receptor antagonist would be reversed by a antagonist at CB2 receptors in the CPP test. In line with this possibility, we reversed the inhibitory effect of rimonabant on cocaine‐induced CPP by pretreating mice with the CB2 receptor antagonist AM630. This result is indicative of an interaction between cannabinoid receptors in modulating the rewarding memories induced by cocaine.

In conclusion, this study supports the hypothesis that endocannabinoids facilitate the stimulant and rewarding properties of cocaine through CB1 receptors but inhibit them if CB2 receptor activation is favoured. Therefore, the ameliorating effects of CB1 receptor antagonists possibly occur by redirecting 2‐AG to CB2 receptor‐mediated activities. Moreover, combining low doses of a CB1 receptor antagonist with 2‐AG hydrolysis inhibitors represents a potential approach to curb the responses to cocaine. These results advance our understanding of endocannabinoid modulation of psychostimulant activity and may inform the development of new pharmacological treatments for drug addiction.

Author contributions

P.H.G. conducted most of the experiments as part of his PhD thesis. A.C.O., J.S.G., V.T.d.S., L.A., J.R.B., E.M.B., F.R.S., A.C.I. and B.N.O. conducted experiments. A.C.d.O., F.M.R., E.A.D.B., D.C.A., D.P.F. and F.A.M. supervised the research. All authors participated in interpreting the results and revising the manuscript and approved the final version.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Declaration of transparency and scientific rigour

This Declaration acknowledges that this paper adheres to the principles for transparent reporting and scientific rigour of preclinical research recommended by funding agencies, publishers and other organisations engaged with supporting research.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Ms. Adriane Aparecida and Mr. Jorge Ferreira for the technical support. This research was funded by Fundação de Amparo à Pesquisa do Estado de Minas Gerais, FAPEMIG (APQ‐01728‐13), Conselho Nacional de Desenvolvimento Científico e Tecnológico, CNPq (477541/2012‐7) and Science Foundation Ireland (10/IN.1/B2976).

Gobira, P. H. , Oliveira, A. C. , Gomes, J. S. , da Silveira, V. T. , Asth, L. , Bastos, J. R. , Batista, E. M. , Issy, A. C. , Okine, B. N. , de Oliveira, A. C. , Ribeiro, F. M. , Del Bel, E. A. , Aguiar, D. C. , Finn, D. P. , and Moreira, F. A. (2019) Opposing roles of CB1 and CB2 cannabinoid receptors in the stimulant and rewarding effects of cocaine. British Journal of Pharmacology, 176: 1541–1551. 10.1111/bph.14473.

Contributor Information

Pedro H Gobira, Email: gobirapedro@hotmail.com.

Fabricio A Moreira, Email: fabriciomoreira@icb.ufmg.br.

References

- Alexander SP, Christopoulos A, Davenport AP, Kelly E, Marrion NV, Peters JA et al (2017a). The Concise Guide to PHARMACOLOGY 2017/18: G protein‐coupled receptors. Br J Pharmacol 174 (Suppl. 1): S17–S129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alexander SP, Fabbro D, Kelly E, Marrion NV, Peters JA, Faccenda E et al (2017b). The Concise Guide to PHARMACOLOGY 2017/18: enzymes. Br J Pharmacol 174 (Suppl. 1): S272–S359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Almeida‐Santos AF, Gobira PH, Souza DP, Ferreira RC, Romero TR, Duarte ID et al (2014). The antipsychotic aripiprazole selectively prevents the stimulant and rewarding effects of morphine in mice. Eur J Pharmacol 742: 139–144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aracil‐Fernandez A, Trigo JM, Garcia‐Gutierrez MS, Ortega‐Alvaro A, Ternianov A, Navarro D et al (2012). Decreased cocaine motor sensitization and self‐administration in mice overexpressing cannabinoid CB(2) receptors. Neuropsychopharmacology 37: 1749–1763. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Batista LA, Gobira PH, Viana TG, Aguiar DC, Moreira FA (2014). Inhibition of endocannabinoid neuronal uptake and hydrolysis as strategies for developing anxiolytic drugs. Behav Pharmacol 25: 425–433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Busquets‐Garcia A, Puighermanal E, Pastor A, de la Torre R, Maldonado R, Ozaita A (2011). Differential role of anandamide and 2‐arachidonoylglycerol in memory and anxiety‐like responses. Biol Psychiatry 70: 479–486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caille S, Alvarez‐Jaimes L, Polis I, Stouffer DG, Parsons LH (2007). Specific alterations of extracellular endocannabinoid levels in the nucleus accumbens by ethanol, heroin, and cocaine self‐administration. J Neurol 27: 3695–3702. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheer JF, Wassum KM, Sombers LA, Heien ML, Ariansen JL, Aragona BJ et al (2007). Phasic dopamine release evoked by abused substances requires cannabinoid receptor activation. J Neurol 27: 791–795. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corbille AG, Valjent E, Marsicano G, Ledent C, Lutz B, Herve D et al (2007). Role of cannabinoid type 1 receptors in locomotor activity and striatal signaling in response to psychostimulants. J Neurosci Off J Soc Neurosci 27: 6937–6947. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cravatt BF, Giang DK, Mayfield SP, Boger DL, Lerner RA, Gilula NB (1996). Molecular characterization of an enzyme that degrades neuromodulatory fatty‐acid amides. Nature 384: 83–87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cunningham CL, Gremel CM, Groblewski PA (2006). Drug‐induced conditioned place preference and aversion in mice. Nat Protoc 1: 1662–1670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Curtis MJ, Alexander S, Cirino G, Docherty JR, George CH, Giembycz MA et al (2018). Experimental design and analysis and their reporting II: updated and simplified guidance for authors and peer reviewers. Br J Pharmacol 175: 987–993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delis F, Polissidis A, Poulia N, Justinova Z, Nomikos GG, Goldberg SR et al (2017). Attenuation of cocaine‐induced conditioned place preference and motor activity via cannabinoid CB2 receptor agonism and CB1 receptor antagonism in rats. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol 20: 269–278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Devane WA, Dysarz FA 3rd, Johnson MR, Melvin LS, Howlett AC (1988). Determination and characterization of a cannabinoid receptor in rat brain. Mol Pharmacol 34: 605–613. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Devane WA, Hanus L, Breuer A, Pertwee RG, Stevenson LA, Griffin G et al (1992). Isolation and structure of a brain constituent that binds to the cannabinoid receptor. Science 258: 1946–1949. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Di Marzo V, De Petrocellis L (2012). Why do cannabinoid receptors have more than one endogenous ligand? Philos Trans R Soc Lond Ser B Biol Sci 367: 3216–3228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dinh TP, Carpenter D, Leslie FM, Freund TF, Katona I, Sensi SL et al (2002). Brain monoglyceride lipase participating in endocannabinoid inactivation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 99: 10819–10824. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eng J (2003). Sample size estimation: how many individuals should be studied? Radiology 227: 309–313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ford GK, Kieran S, Dolan K, Harhen B, Finn DP (2011). A role for the ventral hippocampal endocannabinoid system in fear‐conditioned analgesia and fear responding in the presence of nociceptive tone in rats. Pain 152: 2495–2504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gong JP, Onaivi ES, Ishiguro H, Liu QR, Tagliaferro PA, Brusco A et al (2006). Cannabinoid CB2 receptors: immunohistochemical localization in rat brain. Brain Res 1071: 10–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gonzalez S, Cascio MG, Fernandez‐Ruiz J, Fezza F, Di Marzo V, Ramos JA (2002). Changes in endocannabinoid contents in the brain of rats chronically exposed to nicotine, ethanol or cocaine. Brain Res 954: 73–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harding SD, Sharman JL, Faccenda E, Southan C, Pawson AJ, Ireland S et al (2018). The IUPHAR/BPS Guide to PHARMACOLOGY in 2018: updates and expansion to encompass the new guide to IMMUNOPHARMACOLOGY. Nucl Acids Res 46: D1091–D1106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hernandez G, Oleson EB, Gentry RN, Abbas Z, Bernstein DL, Arvanitogiannis A et al (2014). Endocannabinoids promote cocaine‐induced impulsivity and its rapid dopaminergic correlates. Biol Psychiatry 75: 487–498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kilkenny C, Browne W, Cuthill IC, Emerson M, Altman DG, Group NCRRGW (2010). Animal research: reporting in vivo experiments: the ARRIVE guidelines. Br J Pharmacol 160: 1577–1579. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li X, Hoffman AF, Peng XQ, Lupica CR, Gardner EL, Xi ZX (2009). Attenuation of basal and cocaine‐enhanced locomotion and nucleus accumbens dopamine in cannabinoid CB1‐receptor‐knockout mice. Psychopharmacology 204: 1–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luque‐Rojas MJ, Galeano P, Suarez J, Araos P, Santin LJ, de Fonseca FR et al (2013). Hyperactivity induced by the dopamine D2/D3 receptor agonist quinpirole is attenuated by inhibitors of endocannabinoid degradation in mice. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol 16: 661–676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maldonado R, Valverde O, Berrendero F (2006). Involvement of the endocannabinoid system in drug addiction. Trends Neurosci 29: 225–232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGrath JC, Drummond GB, McLachlan EM, Kilkenny C, Wainwright CL (2010). Guidelines for reporting experiments involving animals: the ARRIVE guidelines. Br J Pharmacol 160: 1573–1576. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mereu M, Tronci V, Chun LE, Thomas AM, Green JL, Katz JL et al (2015). Cocaine‐induced endocannabinoid release modulates behavioral and neurochemical sensitization in mice. Addict Biol 20: 91–103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moreira FA, Crippa JA (2009). The psychiatric side‐effects of rimonabant. Rev Bras Psiquiatr 31: 145–153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Munro S, Thomas KL, Abu‐Shaar M (1993). Molecular characterization of a peripheral receptor for cannabinoids. Nature 365: 61–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Onaivi ES, Ishiguro H, Gong JP, Patel S, Meozzi PA, Myers L et al (2008). Brain neuronal CB2 cannabinoid receptors in drug abuse and depression: from mice to human subjects. PLoS One 3: e1640. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ortega‐Alvaro A, Aracil‐Fernandez A, Garcia‐Gutierrez MS, Navarrete F, Manzanares J (2011). Deletion of CB2 cannabinoid receptor induces schizophrenia‐related behaviors in mice. Neuropsychopharmacology 36: 1489–1504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patel S, Rademacher DJ, Hillard CJ (2003). Differential regulation of the endocannabinoids anandamide and 2‐arachidonylglycerol within the limbic forebrain by dopamine receptor activity. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 306: 880–888. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paxinos G, Watson C (1997). The Rat Brain in Stereotaxic Coordinates. Academic Press: New York. [Google Scholar]

- Pertwee RG (2008). Ligands that target cannabinoid receptors in the brain: from THC to anandamide and beyond. Addict Biol 13: 147–159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petrosino S, Di Marzo V (2010). FAAH and MAGL inhibitors: therapeutic opportunities from regulating endocannabinoid levels. Curr Opin Investig Drugs 11: 51–62. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poncelet M, Barnouin MC, Breliere JC, Le Fur G, Soubrie P (1999). Blockade of cannabinoid (CB1) receptors by 141716 selectively antagonizes drug‐induced reinstatement of exploratory behaviour in gerbils. Psychopharmacology 144: 144–150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soria G, Mendizabal V, Tourino C, Robledo P, Ledent C, Parmentier M et al (2005). Lack of CB1 cannabinoid receptor impairs cocaine self‐administration. Neuropsychopharmacol Off Publ Am Coll Neuropsychopharmacol 30: 1670–1680. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sugiura T, Kondo S, Kishimoto S, Miyashita T, Nakane S, Kodaka T et al (2000). Evidence that 2‐arachidonoylglycerol but not N‐palmitoylethanolamine or anandamide is the physiological ligand for the cannabinoid CB2 receptor. Comparison of the agonistic activities of various cannabinoid receptor ligands in HL‐60 cells. J Biol Chem 275: 605–612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sugiura T, Kondo S, Sukagawa A, Nakane S, Shinoda A, Itoh K et al (1995). 2‐Arachidonoylglycerol: a possible endogenous cannabinoid receptor ligand in brain. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 215: 89–97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valjent E, Corvol JC, Pages C, Besson MJ, Maldonado R, Caboche J (2000). Involvement of the extracellular signal‐regulated kinase cascade for cocaine‐rewarding properties. J Neurosci Off J Soc Neurosci 20: 8701–8709. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vilela LR, Gobira PH, Viana TG, Medeiros DC, Ferreira‐Vieira TH, Doria JG et al (2015). Enhancement of endocannabinoid signaling protects against cocaine‐induced neurotoxicity. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol 286: 178–187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang H, Treadway T, Covey DP, Cheer JF, Lupica CR (2015). Cocaine‐induced endocannabinoid mobilization in the ventral tegmental area. Cell Rep 12: 1997–2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xi ZX, Peng XQ, Li X, Song R, Zhang HY, Liu QR et al (2011). Brain cannabinoid CB(2) receptors modulate cocaine's actions in mice. Nat Neurosci 14: 1160–1166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xi ZX, Spiller K, Pak AC, Gilbert J, Dillon C, Li X et al (2008). Cannabinoid CB1 receptor antagonists attenuate cocaine's rewarding effects: experiments with self‐administration and brain‐stimulation reward in rats. Neuropsychopharmacology 33: 1735–1745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu LL, Zhou SJ, Wang XY, Liu JF, Xue YX, Jiang W et al (2011). Effects of cannabinoid CB(1) receptor antagonist rimonabant on acquisition and reinstatement of psychostimulant reward memory in mice. Behav Brain Res 217: 111–116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang HY, Bi GH, Li X, Li J, Qu H, Zhang SJ et al (2015). Species differences in cannabinoid receptor 2 and receptor responses to cocaine self‐administration in mice and rats. Neuropsychopharmacology 40: 1037–1051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang HY, Gao M, Liu QR, Bi GH, Li X, Yang HJ et al (2014). Cannabinoid CB2 receptors modulate midbrain dopamine neuronal activity and dopamine‐related behavior in mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 111: E5007–E5015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang HY, Gao M, Shen H, Bi GH, Yang HJ, Liu QR et al (2017). Expression of functional cannabinoid CB2 receptor in VTA dopamine neurons in rats. Addict Biol 22: 752–765. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang L, Lou D, Jiao H, Zhang D, Wang X, Xia Y et al (2004). Cocaine‐induced intracellular signaling and gene expression are oppositely regulated by the dopamine D1 and D3 receptors. J Neurol 24: 3344–3354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]