Abstract

This review focuses on recent findings of the physiological and pharmacological role of non‐endocannabinoid N‐acylethanolamines (NAEs) and 2‐monoacylglycerols (2‐MAGs) in the intestine and their involvement in the gut‐brain signalling. Dietary fat suppresses food intake, and much research concerns the known gut peptides, for example, glucagon‐like peptide‐1 (GLP‐1) and cholecystokinin (CCK). NAEs and 2‐MAGs represent another class of local gut signals most probably involved in the regulation of food intake. We discuss the putative biosynthetic pathways and targets of NAEs in the intestine as well as their anorectic role and changes in intestinal levels depending on the dietary status. NAEs can activate the transcription factor PPARα, but studies to evaluate the role of endogenous NAEs are generally lacking. Finally, we review the role of diet‐derived 2‐MAGs in the secretion of anorectic gut peptides via activation of GPR119. Both PPARα and GPR119 have potential as pharmacological targets for the treatment of obesity and the former for treatment of intestinal inflammation.

Linked Articles

This article is part of a themed section on 8th European Workshop on Cannabinoid Research. To view the other articles in this section visit http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/bph.v176.10/issuetoc

Abbreviations

- 2‐LG

2‐linoleoyl glycerol

- 2‐OG

2‐oleoyl glycerol

- 2‐PG

2‐palmitoyl glycerol

- ABHD

α/β‐hydrolase domain

- FAAH

fatty acid amide hydrolase

- CCK

cholecystokinin

- GDE

glycerophosphodiester phosphodiesterase

- GLP‐1

glucagon‐like peptide‐1

- LEA

N‐linoleoylethanolamine

- MAG

monoacylglycerol

- NAAA

N‐acylamide‐hydrolysing acid amidase

- NAE

N‐acylethanolamine

- NAPE

N‐acyl‐phosphatidylethanolamine

- NAPE‐PLD

N‐acyl‐phosphatidylethanolamine‐hydrolysing PLD

- OEA

N‐oleoylethanolamine

- PEA

N‐palmitoylethanolamine

- sPLA2

secretory PLA2

Introduction

N‐Acylethanolamines (NAEs) and 2‐monoacylglycerols (2‐MAGs) are two groups of poorly water soluble signalling lipids both containing a fatty acid, which is linked to either ethanolamine or glycerol, respectively; the former with an amide bond and the latter with an ester bond. They belong to a vast group of fatty acid‐containing bioactive lipids that can exert a number of pharmacological functions in the whole body through activation of specific membrane receptors, nuclear receptors or other proteins. NAEs are also known as acylethanolamides, for example, N‐oleoylethanolamine (OEA) is the same as oleoylethanolamide. The most well‐known NAE and 2‐MAG are the two endocannabinoids, anandamide (AEA) and 2‐arachidonoylglycerol, but the non‐endocannabinoid NAEs and 2‐MAGs seem also to have a number of physiological roles having targets other than the cannabinoid receptors. The endocannabinoids, anandamide and 2‐arachidonoylglycerol, have via activation of the cannabinoid receptors a number of physiological and pathophysiological roles in the intestine, for example, to maintain homeostasis in the gut by controlling hypercontractility and promoting regeneration after injury (Taschler et al., 2017).

The small intestine serves both as an organ for digestion and absorption of food, as well as for signalling to the brain and peripheral organs about the amount of incoming food (Psichas et al., 2015; Steinert et al., 2016; Husted et al., 2017). Non‐endocannabinoid NAEs and 2‐MAGs may participate in the regulation of the gut‐brain signalling in relation to control of food intake, and several recent reviews have discussed this issue (Piomelli, 2013; Hansen, 2014; Kleberg et al., 2014a; DiPatrizio and Piomelli, 2015; Bowen et al., 2017; Brown et al., 2017). The present short review will cover the most recent knowledge on the pharmacological and physiological role of the non‐endocannabinoid NAEs and 2‐MAGs in the signalling from the gut to the brain, and older literature will mostly be covered through citation of recent reviews.

Formation and targets of N‐acylethanolamines

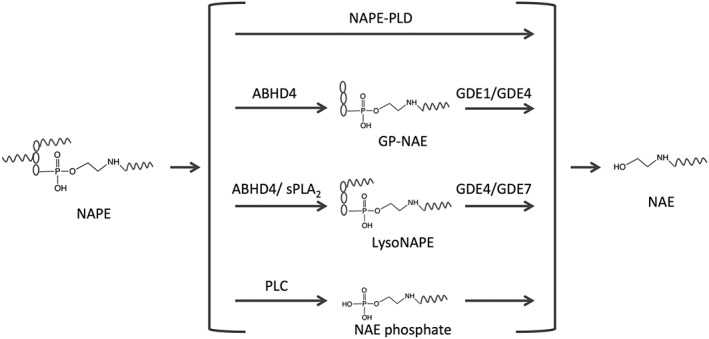

It is generally accepted that NAEs are generated in vivo from their phospholipid precursors, N‐acyl‐phosphatidylethanolamines (NAPEs), which again are generated from the membrane phospholipid phosphatidylethanolamine by Ca2+‐dependent or Ca2+‐independent N‐acyltransferases (Kleberg et al., 2014a; Ogura et al., 2016; Hussain et al., 2017). NAPE can be hydrolysed by a nape‐phospholipase D (NAPE‐PLD) generating NAEs and phosphatidic acid, but other pathways of NAE formation exist involving hydrolytic cleavage of one or both of the glycerol‐linked acyl groups in NAPE by an α/β‐hydrolase domain‐containing enzyme (ABHD) called ABHD4 prior to the liberation of NAE by one of three different glycerophosphodiesterase enzymes (GDE1, GDE4 and GDE7) (Hussain et al., 2017;Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Pathways of N‐acetylethanolamine (NAE) formation. NAPE is considered to be the precursor for the formation of NAE. However, at least four pathways can lead to NAE formation. Pathway one is via the enzyme NAPE‐PLD. Pathway two is via the enzymes α,β‐hydrolase domain‐4 (ABHD4) and glycerophosphodiesterase (GDE)1/GDE4, whereby an intermediate GP‐NAE (glycerophospho‐NAE) is formed. Pathway three is via the enzymes ABHD4/sPLA2 and GDE4/GDE7 whereby an intermediate lysoNAPE (lyso‐N‐acyl‐phosphatidylethanolamine) is formed. Pathway four is via the enzymes PLC and a phosphatase, whereby an intermediate NAE phosphate (phospho‐N‐acylethanolamine) is formed. It is not known which pathway is responsible for NAE formation in the small intestine, but mice deficient in NAPE‐PLD do not show changes in intestinal levels of NAPE or NAE.

Since the NAE levels are not decreased, and the NAPE levels are not increased in the jejunum of NAPE‐PLD‐knockout mice, one or more of the alternative pathways may be responsible for NAE formation in the small intestine of mice (Inoue et al., 2017). Furthermore, formation of N‐linoleoylethanolamine (LEA) and OEA and their corresponding NAPE precursors is regulated in parallel with the formation of AEA and its NAPE precursor during starvation/refeeding of rats (Petersen et al., 2006), suggesting that the physiological regulation of the levels of NAEs in intestinal tissue is dependent upon the regulatory formation of their precursor molecules, the NAPEs. It also suggests that formation of AEA may use other pathways of formation than the non‐endocannabinoid NAEs in the small intestine. The enzymes fatty acid amide hydrolase (FAAH) and N‐acylethanolamine‐ acid amidase (NAAA) are generally considered to be responsible for degradation of non‐endocannabinoid NAEs, where the lysosomal NAAA seems to have specificity for N‐palmitoylethanolamine (PEA) as opposed to FAAH, which will hydrolyse all NAEs (Petrosino and Di Marzo, 2017). However, in the small intestine, ablation or inhibition of FAAH does only to a small extent – if at all – increase the tissue levels of non‐endocannabinoid NAEs (Capasso et al., 2005; Fegley et al., 2005; Bashashati et al., 2012; Tourino et al., 2010), and it has been suggested that other hydrolase activities besides FAAH may contribute to feeding‐regulated OEA hydrolysis (Fu et al., 2007). It is not clear if NAAA contributes to degradation of endogenous PEA in the small intestine. In the colon, inhibitors of NAAA can increase PEA levels and counteract murine colitis, while inhibitors of FAAH had no effect (Alhouayek et al., 2015). Thus, in the small intestine, both the pathways and the enzymes involved in synthesis and degradation of non‐endocannabinoid NAEs are at present obscure.

The non‐endocannabinoid NAEs have a number of pharmacological activities, for example, inhibiting food intake, being anti‐inflammatory and pain ameliorating (Piomelli, 2013; Kleberg et al., 2014a; Petrosino and Di Marzo, 2017), via activation of various target proteins, involving GPCRs, ion channel receptors or transcription factors and others (Table 1). For a long time, it has been known that OEA in micromolar concentrations inhibits various ceramidases in vitro and in vivo (Li et al., 2014). It is unclear whether endogenous OEA in the intestine also has this property.

Table 1.

Targets for non‐cannabinoid NAEs and 2‐MAGs

| Targets | Agonists | References |

|---|---|---|

| GPR119 | OEA, PEA, LEA, 2‐OG, 2‐PG and 2‐LG | Hansen et al. (2011; 2012) |

| GPR55 | OEA and PEA | Ryberg et al. (2007) |

| ADRGF1 | DHEA | Lee et al. (2016) |

| PPARα | OEA, PEA and LEA | Piomelli (2013) and Artmann et al. (2008) |

| PPARβ/δ | OEA | Fu et al. (2003) |

| TRPV1 | OEA, DHEA, LEA, 2‐OG and 2‐LG | Movahed et al. (2005) and Iwasaki et al. (2008) |

| Other ion channels | OEA | Chemin et al. (2014), Amoros et al. (2010), Barana et al. (2010) and Voitychuk et al. (2012) |

| Sirtuin 6 (histone deacetylase) | PEA, OEA and LEA | Rahnasto‐Rilla et al. (2016) |

| Smoothened | LEA | Khaliullina et al. (2015) |

| Ceramidase | OEA | Li et al. (2014) |

| GLP‐1 | OEA and 2‐OG | Cheng et al. (2015) |

| FAAH | OEA and PEA | Petrosino and Di Marzo (2017) |

DHEA, N‐docosahexaenoylethanolamine.

PPARα is a transcription factor primarily involved in regulating the expression of enzymes and proteins involved in metabolic processes stimulated by fasting (Gross et al., 2017). OEA, PEA and LEA can all activate PPARα, and the anorexic, analgesic and anti‐inflammatory effects of these NAEs seem to be mediated through PPARα (Fu et al., 2003; Guzmán et al., 2004; Lo Verme et al., 2005; Artmann et al., 2008; Piomelli, 2013; Pontis et al., 2016; Bowen et al., 2017; Brown et al., 2017). The response rate of exogenous OEA with respect to food intake is in the order of minutes whereas the response rate of a transcription factor signalling via formation of new proteins is assumed to be in hours. However, PPARα may work in a non‐genomic way influencing membrane ion channel activities (Melis et al., 2010; Khasabova et al., 2012), which might prove to be responsible for the signalling of OEA through PPARα to the vagus (Piomelli, 2013). Further studies are required for understanding this non‐genomic signalling of OEA through PPARα. In the case of the small intestine, it is also unclear where PPARα is localized, in the enterocytes or in the nervous cells (vagus) associated with the small intestine (Hankir et al., 2017). PPARβ/δ can also be activated by OEA in vitro (Fu et al., 2003) but is not known whether this also occurs in vivo.

TRPV1 can be activated by several NAEs and monoacylglycerols (Movahed et al., 2005; Iwasaki et al., 2008); a possible involvement of this receptor in the anorectic effects of NAEs and 2‐MAGs will be discussed below. NAEs have been reported to inhibit a number of ion channels, that is, OEA can inhibit voltage‐gated Na+‐channels, low‐voltage‐activated (T‐type, Cav 3.x) channels and high‐voltage‐activated dihydropyridine‐sensitive (L‐type Cav 1.x)‐channels as well as the K+‐channels Kv3.4 and Kv1.5 (Amoros et al., 2010; Barana et al., 2010; Voitychuk et al., 2012; Chemin et al., 2014). It is unclear whether these in vitro effects have any physiological or pharmacological significance in the intestine in vivo.

Recently, it was reported that NAEs could activate sirtuin 6 in vitro, a NAD+‐dependent histone deacetylase, which is involved in regulating genomic stability, oxidative stress and glucose metabolism (Rahnasto‐Rilla et al., 2016). It is at present not known whether this has any physiological or pharmacological significance.

Several GPCRs can be activated by NAEs, that is, smoothened, GPR55, GPR119 and GPR110. Of these, GPR119 in the small intestine is involved in dietary fat‐induced release of the gut hormones, for example, GLP‐1 and PYY (Hansen et al., 2012; Mandoe et al., 2015; Husted et al., 2017), while in the colon, microbiota‐derived metabolites may be responsible for the stimulation of GPR119 (Cohen et al., 2017). Smoothened in the Hedgehog pathway may be of importance for the development of the enteric nervous system between the smooth muscle layers of the gastrointestinal tract (Jin et al., 2015). There is no information about a possible interaction of non‐endocannabinoid NAEs with smoothened in the intestine. GPR55 may be involved in gastrointestinal tract processes such as motility and possibly secretion and intestinal inflammation (Lin et al., 2011; Shore and Reggio, 2015), but it still remains unknown whether exogenous or endogenous NAEs will activate GPR55 in vivo. ADGRF1 (also called GPR110), which belongs to the adhesion GPCRs, is only expressed at a very low level in the small intestine of mice (Ma et al., 2017).

Exogenous NAEs are substrates for FAAH and some of them also for NAAA. In humans, a FAAH2 enzyme also exists, but it is apparently not expressed in the small intestine (Wei et al., 2006). When NAEs are given in high pharmacological doses, they may compete with endogenous FAAH substrates like anandamide, OEA, PEA, LEA and N‐acyl‐taurines (Long et al., 2011), for example, exogenous OEA can increase mouse intestinal levels of anandamide (Capasso et al., 2005), and exogenous PEA to mice can increase N‐steroylethanolamine (serum, heart, brain and retina), OEA (serum, retina), LEA (retina) and anandamide (brain and retina) (Grillo et al., 2013). The effect of inhibition of degradation of endogenous NAEs can explain why, for example, exogenous PEA can have effects that are mediated via activation of cannabinoid receptors although PEA by itself cannot activate cannabinoid receptors (Capasso et al., 2005; Capasso et al., 2014). Exogenous PEA can also increase endogenous levels of 2‐arachidonoyl glycerol, probably via inhibition of 2‐arachidonoyl glycerol degradation (Petrosino et al., 2016).

Recently, it was reported that OEA [and 2‐oleoyl glycerol (2‐OG)] could directly bind to GLP‐1 thereby increasing its potency considerably, that is, at 9.2 μM OEA the EC50 for GLP‐1‐induced cAMP formation decreased approximately 10‐fold (Cheng et al., 2015). As GLP‐1 has anorectic properties (Flint et al., 1998), and as i.p. injected OEA (5 mg·kg−1) can inhibit food intake and increase plasma levels of OEA approximately 14‐fold after 30 min to approximately 190 nM (Gaetani et al., 2003), it raises the possibility that formation of a complex with endogenous GLP‐1 may add to the explanation for the anorectic mechanism of exogenous OEA.

Exogenous N‐acylethanolamines and the intestine

OEA, PEA and LEA have all been shown to have clear anorectic effects in rodents whether injected i.p., infused into the duodenum or given by gavage or capsules (Oveisi et al., 2004; Piomelli, 2013; Tellez et al., 2013; Hansen, 2014). OEA as the prototype of these NAEs has been shown to prolong latency to eat (i.e. a satiety effect) thereby decreasing daily food intake (Gaetani et al., 2003). This satiety effect seems to be mediated through activation of PPARα since synthetic PPARα agonists exert the same effect and since the anorectic effect of OEA is absent in mice deficient in PPARα (Piomelli, 2013; Figure 2). This dose of OEA (10 mg·kg−1 i.p.) decreased food intake without seriously influencing other parameters like conditional taste aversion, induction of visceral illness, decrease of motor output or disrupting alertness (Rodríguez de Fonseca et al., 2001; Proulx et al., 2005). Intestinal infusion of smaller doses of OEA (2 mg·kg−1) can also potentiate the decreased striatal dopamine release in response to administration of a low‐fat emulsion to mice (Tellez et al., 2013). The vagus nerve has been implicated in the signalling from the gut to the brain since the anorectic effect of i.p. injections of OEA (10 mg·kg−1) is lost by cutting the vagus below the diaphragm or treatment with the neurotoxin capsaicin, which can destroy the vagus (Rodríguez de Fonseca et al., 2001; Tellez et al., 2013). In addition, the effect of gastrointestinal fat infusion on striatal dopamine release is abolished by vagotomy and administration of a PPARα antagonist (Tellez et al., 2013), suggesting that the effect of OEA (exogenous or endogenous) is mediated via PPARα activation and vagal afferents to the brain involving both the appetite centre and dopamine release in dorsal striatum. OEA was also ineffective when injected directly into the rat brain ventricles (Rodríguez de Fonseca et al., 2001), and the anorectic effect of i.p. injected OEA is not caused by activation of TRPV1 (Fu et al., 2003; Tellez et al., 2013) or of GPR119 (Lan et al., 2009). However, a recent paper has questioned the involvement of the vagus nerve in mediating the anorectic effect of 10 mg·kg−1 OEA i.p., the same dose that was tested in totally vagotomized animals (Karimian et al., 2014). Karimian and colleagues performed vagal subdiaphragmatic deafferentation on rats, a procedure that abolishes all afferent signalling but leaves intact half of the efferent innervation. This surgical method is different from a complete subdiaphragmatic vagotomy as it allows partial efferent signalling to occur from the gut to the brain while all vagal input to the brain is blocked. Further studies must clarify this discrepancy of whether vagus is or is not involved in the effect of i.p.‐injected and intestinal‐infused OEA, which may or may not reach the area postrema of the brain via the vascular system, thereby being involved in appetite control (Romano et al., 2017). On the other hand, intestinal infusion of 2 mg·kg−1 OEA (Tellez et al., 2013) will probably not result in any OEA reaching the brain through the vasculature, since OEA given by gavage is substantially metabolized in the gastrointestinal tract (Nielsen et al., 2004). Also, an anorectic dose of 50 mg·kg−1 of OEA in capsules to rats increased the levels of OEA in several tissues (small intestine, plasma, liver and adipose tissue) but not in the brain and muscles (Oveisi et al., 2004), suggesting that exogenous OEA has an anorectic effect without entering the brain (Figure 2). These uncertainties need to be clarified.

Figure 2.

Endogenous N‐oleoylethanolamine (OEA) may signal dietary status to the brain. Levels of OEA and other anorectic NAEs in the upper small intestine change depend on the dietary status. OEA is a potent activator of PPARα and is suggested to act via the vagus to stimulate dopamine release and reduce food intake and fat desire. Controversial evidence exists with regard to the involvement of the vagus (therefore dashed arrow) mediating the anorectic effects of exogenous OEA, and evidence for the same effect of endogenous OEA is weak. Long‐term feeding of a high‐fat diet (HFD) lowers the levels of OEA in the upper small intestine, and this may explain the increase in energy intake and development of obesity in rodents. Fasting and refeeding change the levels of OEA in opposite ways, which supports a physiological role of OEA in the regulation of food intake. The location of PPARα and the connecting pathway between the receptor and the brain are not completely understood (therefore a question mark).

OEA and other NAEs are found in low amounts in both animals and plants (Schmid et al., 1990; Chapman, 2004). In our opinion, the levels of anorectic NAEs in foodstuffs are far too low to exert any anorectic effects in humans. This opinion is based on the assumption that total NAEs in animal products is probably below 5 nmol·g−1 (=below 1.75 μg·g−1), since PEA in rodent and human tissues may be on average below 1 nmol·g−1 tissue (Hansen, 2013). Furthermore, total NAEs in plants are assumed to be below 2 μg·g−1, since total NAE levels in plant seeds like corn and soybean are within 0.5–2.0 μg·g−1 (Chapman, 2004). In rats, an anorectic effect of OEA has been reported with an oral intake of 10–50 mg·kg−1 given by gavage or by capsules (Nielsen et al., 2004; Oveisi et al., 2004), and if this can be translated to humans, one may assume the intake needs to be around 700–3500 mg for a 70 kg man, and this may be found in 350–1750 kg of food if all NAEs in foodstuff are as potent as OEA. Recently, a nutraceutical supplement called RiduZone containing 200 mg OEA per capsule has been claimed to induce 7–8% weight loss in humans over 4–12 weeks (3–4 capsules per day) in a non‐published study, which was not placebo‐controlled (Hallmark et al., 2016; Brown et al., 2017; Romano et al., 2017). Whether this proves to be correct must await a larger placebo‐controlled study.

Exogenous PEA has anti‐inflammatory and pain reducing effects primarily via activation of PPARα (Petrosino and Di Marzo, 2017), and it has been shown that PEA treatment of a mouse model of dextran sodium sulphate‐induced ulcerative colitis improved macroscopic disease signs as well as decreasing neutrophil infiltration and the expression and release of pro‐inflammatory cytokines (Esposito et al., 2014). Increasing the endogenous level of PEA in the colon by giving an inhibitor of NAAA reduced the inflammation in the colon in a mouse model of colitis (Alhouayek et al., 2015). In in vitro models of colon cancer, PEA was shown to inhibit angiogenesis via activation of PPARα (Sarnelli et al., 2016). PEA had analgesic effects in clinical studies in doses of 400–1200 mg·day−1, but there has apparently been no reports on PEA‐induced weight loss as a side effect in these studies (Artukoglu et al., 2017).

Exogenous OEA and PEA have been reported to stimulate tight junctions in vitro in model cells of the small intestine (CaCo‐2 cells) via activation of PPARα and TRPV1 (Karwad et al., 2017), but it is unclear whether endogenous OEA and PEA have these functions in vivo.

Endogenous N‐acylethanolamines and the intestine

Endogenous levels of OEA, PEA and LEA in jejunum of lean rats and mice are decreased by fasting and rapidly increase (within 1 h) upon refeeding (Petersen et al., 2006; Igarashi et al., 2015; Figure 2), and levels of OEA (and probably also PEA and LEA) are high in the small intestine of mice during the day time when they sleep and low at night time when they eat (Fu et al., 2003). Anandamide, N‐stearoylethanolamine and N‐vaccenoylethanolamine do not generally change in the same way as OEA, LEA and PEA do (Petersen et al., 2006; Igarashi et al., 2015), suggesting different pathways for their biosynthesis. Transient overexpression of NAPE‐PLD in the small intestine of mice resulted within the same time window in increased NAPE‐PLD activity, increased levels of OEA and PEA (LEA was not reported) and decreased food intake (Fu et al., 2008). All these data support a role for endogenous intestinal OEA, PEA and LEA in regulating food intake (Piomelli, 2013; Hansen, 2014; Bowen et al., 2017; Brown et al., 2017), but since the pathways of their formation and degradation in the intestinal tissue are not clear and since no pharmacological tools are available to stimulate or inhibit their formation, hard proof is lacking. The putative regulatory role of endogenous OEA, PEA and LEA in the small intestine on food intake relies mainly on their suggested signalling from the gut to the brain via the vagus (Rodríguez de Fonseca et al., 2001; Piomelli, 2013; Tellez et al., 2013; Hankir et al., 2017), and this involvement of the vagus has recently been questioned (Karimian et al., 2014; Romano et al., 2017) as described above.

Dietary fat has been shown to decrease the small intestinal levels of OEA, PEA and LEA in a time‐ (1–5 days) and dose‐dependent (20–45 energy%) manner (Artmann et al., 2008; Diep et al., 2011; Diep et al., 2014; Hansen, 2014; Igarashi et al., 2015), and the fasting/refeeding response (i.e. a decrease followed by an increase in intestinal levels of OEA and LEA) disappears or is strongly dampened in high‐fat fed mice and rats (Igarashi et al., 2015; Hankir et al., 2017). The decreasing effect of dietary fat on OEA, PEA and LEA levels seems to be mediated by a fatty acid receptor and by decreasing the level of their precursors, suggesting an effect of dietary fat on expression of the NAPE‐generating enzyme in the small intestine (Diep et al., 2014). At present, this enzyme has not been identified. Dietary fat does not decrease levels of NAEs in the brain or the liver (Artmann et al., 2008). If the intestinal OEA, PEA and LEA have an anorectic role, then a fat‐induced decrease in their levels may promote increased food intake and weight gain, a well‐known effect of high‐fat diets (Hansen, 2014).

Obese rats have a preference for dietary fat, and this is normalized following bariatric surgery in a seemingly OEA‐dependent way (Hankir et al., 2017). In these obese rats, endogenous intestinal production of OEA in response to fasting/refeeding is compromised, and bariatric surgery normalized both their striatal dopamine response to gastric infusion of fat and decreased their obesity‐induced preference for dietary fat in a PPARα‐ and vagus‐dependent way. Bariatric surgery re‐established the OEA production to fasting/refeeding in the remaining distal part of the small intestine (Hankir et al., 2017). In these scenarios, the signalling from the gut to the brain in response to dietary fat seems to be controlled by intestinal levels of OEA, PPARα and the vagus nerve. A low small intestinal level of OEA, which is seen in fat‐fed obese rats and mice, is suggested to result in a lower dopamine response in striatum after dietary fat, and a higher preference for dietary fat, which may represent a compensatory mechanism in the reward centre of the brain (Tellez et al., 2013).

Acute duodenal infusion of a high load of the soybean oil‐based Intralipid (1.1 g fat in 10 min) to 24 h fasted rats increased the endogenous levels of OEA and LEA in the proximal small intestine (Schwartz et al., 2008; Igarashi et al., 2015), probably by using the Intralipid‐derived oleate and linoleate as precursors in a manner dependent on the membrane protein CD36, which to some degree may facilitate fatty acid uptake (Schwartz et al., 2008; Guijarro et al., 2010). It has previously been seen in prolonged feeding studies (days) that diets rich in specific fatty acids, for example, palmitic acid, oleic acid and linoleic acid, resulted in a small relative increase in the intestinal level of their corresponding NAEs, that is, PEA, OEA and LEA, while at the same time, the overall level of the individual NAEs are decreased due to the high‐fat intake (Artmann et al., 2008). Dietary fat has an acute satiation effect, which most likely can be ascribed to release of anorectic gut hormones like cholecystokinin (CCK), GLP‐1 and others (Feinle et al., 2003; Feinle‐Bisset, 2016). A high‐fat diet over several days decreases the intestinal levels of OEA, PEA and LEA in rodents, and this may result in increased intake of calories (Hansen, 2014). We must await further studies to see whether an acute dietary intake in non‐fasted rats of a more physiological relevant amount of fat will result in increased intestinal levels of OEA, PEA and LEA.

Formation and targets of 2‐monoacylglycerols

A number of triacylglycerol‐hydrolysing lipases are sn‐1,3‐specific, that is, they generate 2‐monoacylglycerol and two fatty acids. These enzymes include pancreatic lipase in the intestinal lumen (Mu and Porsgaard, 2005), lipoprotein lipase in the vascular lumen (Kleberg et al., 2014b) and combined adipose‐triglyceride‐lipase/hormone‐sensitive lipase together with the co‐activator CGI58 in adipocytes (Young and Zechner, 2013). Besides these pathways, 2‐MAGs may also be generated from cellular phospholipids by pathways involving PLA1 plus lysophospholipase D/phosphatase or lysophospholipase C, and PLC/DAG lipase (Figure 3; Kleberg et al., 2014a). 2‐MAG generated in the intestinal lumen is mostly used for triacylglycerol synthesis in the enterocyte involving the enzyme monoacylglycerol O‐acyltransferase 2 (Yen et al., 2015). 2‐Monoacylglycerols, including the endocannabinoid, 2‐arachidonoyl glycerol, are degraded by a monoacylglycerol lipase for which both knockout mice and enzyme inhibitors have been generated, but studies have mostly focused on increases in endogenous 2‐arachidonoyl glycerol and cannabinoid receptor‐related effects (Grabner et al., 2017). Monoacylglycerols can also be degraded by other enzymes, for example, ABHD6 and ABHD12 (Poursharifi et al., 2017), but their roles in the intestine are not known. The pathway for generating 2‐MAGs like 2‐OG, 2‐linoleoyl glycerol (2‐LG) and 2‐palmitoyl glycerol (2‐PG) in the intestinal lumen involves the pancreatic lipase and dietary triacylglycerol. These 2‐MAGs are later taken up into the enterocytes together with non‐esterified fatty acids to be used for formation of triacylglycerol in chylomicrons secreted from the intestinal cells (Mu and Porsgaard, 2005; Kleberg et al., 2014a; Yen et al., 2015). The pathways for generation of 2‐MAGs within the intestinal cells are not known, but some 2‐MAGs may be formed from the vascular site by the action of lipoprotein lipase on plasma lipoproteins (Kleberg et al., 2014b; Psichas et al., 2017). OEA is known to be an agonist for GPR119, but in 2011, it was shown that 2‐OG, 2‐LG and 2‐PG could also activate this receptor, which is localized on enteroendocrine L‐cells of the small intestine (Hansen et al., 2011, 2012; Hassing et al., 2016a). Activation of GPR119 is known to stimulate release of GLP‐1, GIP, neurotensin and PYY in rodents and humans (Hansen et al., 2011; 2012; Hassing et al., 2016a). 2‐OG and 2‐LG have also been reported to activate TRPV1 in vitro with roughly the same EC50 values as OEA (Iwasaki et al., 2008), but it is not known whether this occurs in vivo.

Figure 3.

Pathways of 2‐monoacylglycerol (2‐MAG) formation. 2‐MAG can be formed from both triacylglycerol and phospholipids. In the lumen of the small intestine, in the vasculature and in the adipocytes, TAG (triacylglycerol) can be converted to 2‐MAG by pancreatic lipase, by LPL (lipoprotein lipase), and by the combined action of ATGL/LIPE (adipose‐triglyceride lipase/hormone‐sensitive lipase E) respectively. 2‐MAGs as the well‐known 2‐archidonoylglycerol can be formed via the enzymes PLC/diacylglycerol lipase (DAGL) in many cells. Other pathways from phospholipids may also exist within the cells. FFAs, free fatty acids.

Exogenous 2‐monoacylglycerol and the intestine

2‐MAGs derived from digestion of dietary fat can be considered as exogenous 2‐MAGs. In fact, humans in the Western societies eat around 100 g of fat (triacylglycerol) per day resulting in the formation of around 40 g of 2‐MAGs per day in the small intestine, and 2‐OG represents the vast majority of these 2‐MAGs (Hansen et al., 2012). In humans having a low fat intake (20 mL olive oil), GPR119 seems to be the only receptor responsible for fat‐induced release of the gut hormones GLP‐1, PYY and neurotensin (Hansen et al., 2012; Mandoe et al., 2015) with little if any contribution from activated fatty acid receptors (Figure 4). Dietary fat‐induced release of GIP in humans seems to involve both GPR119 in synergy with one or more fatty acid receptors (Mandoe et al., 2015). In humans, the expression of GPR119 in the small intestine seems to be rapidly up‐regulated in response to a physiological relevant duodenal infusion of a fat emulsion (Cvijanovic et al., 2017). Fatty acid receptors, FFA1 and FFA4 (also called GPR40 and GPR120), which also have been suggested to induce GLP‐1 release (Hauge et al., 2017; Husted et al., 2017), seem to be of minor importance as seen from studies of mice deficient in GPR119 (Moss et al., 2015), FFA1 and FFA4 receptors (Sankoda et al., 2017). At higher fat intake, a synergism between 2‐MAG‐activated GPR119 and fatty acid‐activated FFA1 receptor may occur (Ekberg et al., 2016; Hauge et al., 2017). These two receptors, GPR119 and FFA1, seem also to be involved in mediating the satiation effect of dietary fat intake in the small intestine. Mice can learn to self‐administer a fat emulsion directly into the stomach without receiving any flavour cues, and the mice terminate the intake, when they feel satiation (Ferreira et al., 2012). In such an experimental set‐up, both 2‐OG (probably via GLP‐1 release) as well as non‐esterified fatty acid (probably via CCK release) can individually induce satiation (Kleberg et al., 2015). However, 2‐OG was not involved in the dietary fat‐induced dopamine release in dorsal striatum, which was only mediated by non‐esterified fatty acid (Kleberg et al., 2015). These effects of 2‐MAG on GPR119 and the accompanying release of gut hormones having satiation effects can probably explain some of the phenotype characteristic (being leaner, eating less) of mice deficient in MAGL (Douglass et al., 2015) and in monoacylglycerol O‐acyltransferase‐2 (Nelson et al., 2014), since it can be assumed that deletion or inhibition of one of these enzymes may increase levels of 2‐MAGs in the intestine leading to increased secretion of the anorectic gut hormones like GLP‐1.

Figure 4.

2‐monoacylglycerol (2‐MAG) activates GPR119 and is suggested to be the major stimulator of GLP‐1 release in the intestine after fat intake. Triacylglycerol (TAG) is digested by the lipases to 2‐MAG and free fatty acids (FFAs, not shown) in the gut lumen. Enteroendocrine cells (green) sense 2‐MAG and FFAs through different receptors. GPR119 is one of the fat sensing receptors expressed on the surface of the enteroendocrine cells, and 2‐MAG is an agonist. Activation of GPR119 is known to stimulate the secretion of the hormones GLP‐1, PYY and neurotensin. These are signalling peptides that initially diffuse in the lamina propria (yellow) having various functions in other organs. Different signalling pathways from the gut to other organs have been suggested for these hormones; the vagal and the endocrine via the vasculature are shown here. GPR119 is depicted on both the basolateral and apical membranes of the enteroendocrine cells, as its actual position is yet to be determined.

In our review of 2012 (Hansen et al., 2012), GPR119 was suggested to be localized at the apical membrane of the L cells thereby facing the intestinal lumen, but suggestions have been put forward that GPR119 as well as other nutrient‐sensing receptors may possibly localize at the basolateral membrane (Husted et al., 2017; Figure 4). Studies with small intestine perfusion suggest that the FFA1 receptor is localized on the basolateral membrane of L cells (Christensen et al., 2015) where it may be activated by fatty acids released by lipoprotein lipase in the intestinal capillaries (Psichas et al., 2017). Mice lacking the enzyme 1‐acylglycerophosphocholine O‐acyltransferase, an enzyme which is responsible for enriching membrane phosphatidylcholine in the intestinal cells with linoleic acid, thereby securing higher fluidity and an increased flip‐flop rate in the absorption of dietary fatty acids (and perhaps 2‐MAGs), have very decreased fat absorption, low chylomicron secretion and highly increased secretion of GLP‐1 and PYY (Wang et al., 2016). Intestinal absorption of fatty acids and 2‐MAG is assumed to involve the same mechanism (Murota and Storch, 2005). It may be assumed that the very high GLP‐1 and PYY secretion in these mice can be ascribed to a prolonged and increased level of 2‐MAG in the intestinal lumen, which would then also suggest that GPR119 is localized on the luminal membrane of L cells.

Endogenous 2‐monoacylglycerol and the intestine

2‐OG, 2‐PG and 2‐LG are present in the tissue of the small intestine (Petersen et al., 2006), but it is unclear whether they are formed in the intestinal cells or originate from diet‐derived 2‐MAGs. However, rats fed a diet enriched in fat, which had palmitic acid in the sn‐2 position of the triacylglycerol, for 5 weeks had a 1.5‐fold higher level of 2‐PG in the intestinal tissue as compared with the control rats (Carta et al., 2015), suggesting that at least some of the 2‐MAGs in the tissue originate from the diet.

In cell cultures GPR119 has some apparent constitutive activity, some of which may be caused by endogenous 2‐MAG in the cells, since addition of a monoacylglycerol lipase inhibitor increased the apparent constitutive activity (Hassing et al., 2016b). This raises the question of whether L‐cell‐produced 2‐MAG will activate GPR119. Furthermore, dependent on whether GPR119 is localized to the basolateral membrane, lipoprotein lipase‐derived 2‐MAG in the intestinal capillary may also activate GPR119 in the L‐cells.

Concluding remarks

The non‐endocannabinoid NAEs seem to have anorectic functions, where intestinal levels of PEA, LEA and OEA appear to signal from the gut to the brain via PPARα and the vagus nerve. Furthermore, via the same mechanisms, they may also regulate dietary fat preference and dietary fat‐induced striatal dopamine release in the reward centre of the brain. The intestinal levels of these lipid messengers are decreased by prolonged intake of high‐fat diets, and these NAEs may in this way participate in promoting increased food intake and obesity. Activation of PPARα mediates this effect, and this transcription factor may be a pharmacological target for the development of drugs to treat obesity and a desire for fat. However, a crucial step in this scenario involves the vagus nerve in mediating the signalling from the gut to the brain, and this involvement has been questioned. Likewise, the lack of pharmacological tools to decrease or increase the intestinal levels of OEA, PEA and LEA are missing, so most of the experimental evidence relies on analysing the effects of exogenous NAEs. Future studies should focus on clarifying the route of formation and degradation of non‐endocannabinoid NAEs in the small intestine of rodents and humans. This knowledge may eventually result in the development of pharmacological tools to enhance or decrease the endogenous levels of OEA and other non‐endocannabinoid NAEs for studying the role of these endogenous bioactive lipids. Furthermore, a clarification of the role of the vagus and the mechanism of PPARα signalling in response to exogenous OEA in the small intestine is of great importance.

The formation of 2‐MAGs, that is, 2‐OG, 2‐PG and 2‐LG, during the digestion of dietary fat in humans seems to explain much of the fat‐induced release of the anorectic GLP‐1, PYY and neurotensin via the activation of GPR119 on enteroendocrine cells of the small intestine. This release mechanism can thereby also partially explain the satiation effect of an acute intake of a fat‐rich meal. GPR119 may be a pharmacological target for development of drugs promoting increased release of these anorectic gut hormones. Future studies should clarify the role of GPR119 and other lipid receptors in the small intestine in mediating the release of intestinal hormones in response to dietary fat. Although outside the scope of this review, it would be interesting to know the role of GPR119 in heart muscle (Cornall et al., 2015), the eye (Miller et al., 2017) and in macrophages (Hu et al., 2014).

Nomenclature of targets and ligands

Key protein targets and ligands in this article are hyperlinked to corresponding entries in http://www.guidetopharmacology.org, the common portal for data from the IUPHAR/BPS Guide to PHARMACOLOGY (Harding et al., 2018), and are permanently archived in the Concise Guide to PHARMACOLOGY 2017/2018 (Alexander et al., 2017a,b,c,d).

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful to the support from the Augustinus Fonden, Lundbeckfonden, and Desirée og Niels Ydes Fond.

Hansen, H. S. , and Vana, V. (2019) Non‐endocannabinoid N‐acylethanolamines and 2‐monoacylglycerols in the intestine. British Journal of Pharmacology, 176: 1443–1454. 10.1111/bph.14175.

References

- Alexander SPH, Christopoulos A, Davenport AP, Kelly E, Marrion NV, Peters JA et al (2017a). The Concise Guide to PHARMACOLOGY 2017/18: G protein‐coupled receptors. Br J Pharmacol 174: S17–S129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alexander SPH, Cidlowski JA, Kelly E, Marrion NV, Peters JA, Faccenda E et al (2017b). The Concise Guide to PHARMACOLOGY 2017/18: Nuclear hormone receptors. Br J Pharmacol 174: S208–S224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alexander SPH, Fabbro D, Kelly E, Marrion NV, Peters JA, Faccenda E et al (2017c). The Concise Guide to PHARMACOLOGY 2017/18: Enzymes. Br J Pharmacol 174: S272–S359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alexander SPH, Striessnig J, Kelly E, Marrion NV, Peters JA, Faccenda E et al (2017d). The Concise Guide to PHARMACOLOGY 2017/18: Voltage‐gated ion channels. Br J Pharmacol 174: S160–S194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alhouayek M, Bottemanne P, Subramanian KV, Lambert DM, Makriyannis A, Cani PD et al (2015). N‐Acylethanolamine‐hydrolyzing acid amidase inhibition increases colon N‐palmitoylethanolamine levels and counteracts murine colitis. FASEB J 29: 650–661. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amoros I, Barana A, Caballero R, Gomez R, Osuna L, Lillo MP et al (2010). Endocannabinoids and cannabinoid analogues block human cardiac Kv4.3 channels in a receptor‐independent manner. J Mol Cell Cardiol 48: 201–210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Artmann A, Petersen G, Hellgren LI, Boberg J, Skonberg C, Hansen SH et al (2008). Influence of dietary fatty acids on endocannbinoid and n‐acylethanolamine levels in rat brain, liver and small intestine. Biochim Biophys Acta Mol Cell Biol Lipids 1781: 200–212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Artukoglu BB, Beyer C, Zuloff‐Shani A, Brener E, Bloch MH (2017). Efficacy of palmitoylethanolamide for pain: a meta‐analysis. Pain Physician 20: 353–362. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barana A, Amoros I, Caballero R, Gomez R, Osuna L, Lillo MP et al (2010). Endocannabinoids and cannabinoid analogues block cardiac hKv1.5 channels in a cannabinoid receptor‐independent manner. Cardiovasc Res 85: 56–67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bashashati M, Storr MA, Nikas SP, Wood JT, Godlewski G, Liu J et al (2012). Inhibiting fatty acid amide hydrolase normalizes endotoxin‐induced enhanced gastrointestinal motility in mice. Br J Pharmacol 165: 1556–1571. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowen KJ, Kris‐Etherton PM, Shearer GC, West SG, Reddivari L, Jones PJ (2017). Oleic acid‐derived oleoylethanolamide: a nutritional science perspective. Prog Lipid Res 67: 1–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown JD, Karimian AE, Ayala JE (2017). Oleoylethanolamide: a fat ally in the fight against obesity. Physiol Behav 176: 50–58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Capasso R, Matias I, Lutz B, Borrelli F, Capasso F, Marsicano G et al (2005). Fatty acid amide hydrolase controls mouse intestinal motility in vivo. Gastroenterology 129: 941–951. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Capasso R, Orlando P, Pagano E, Aveta T, Buono L, Borrelli F et al (2014). Ultramicronized palmitoylethanolamide normalizes intestinal motility in a murine model of post‐inflammatory accelerated transit: involvement of CB receptors and TRPV1. Br J Pharmacol 171: 4026–4039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carta G, Murru E, Lisai S, Sirigu A, Piras A, Collu M et al (2015). Dietary triacylglycerols with palmitic acid in the sn‐2 position modulate levels of N‐acylethanolamides in rat tissues. PLoS One 10: e0120424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chapman KD (2004). Occurrence, metabolism, and prospective functions of N‐acylethanolamines in plants. Prog Lipid Res 43: 302–327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chemin J, Cazade M, Lory P (2014). Modulation of T‐type calcium channels by bioactive lipids. Pflugers Arch 466: 689–700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng YH, Ho MS, Huang WT, Chou YT, King K (2015). Modulation of glucagon‐like peptide (GLP)‐1 potency by endocannabinoid‐like lipids represents a novel mode of regulating GLP‐1 receptor signaling. J Biol Chem 290: 14302–14313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christensen LW, Kuhre RE, Janus C, Svendsen B, Holst JJ (2015). Vascular, but not luminal, activation of FFAR1 (GPR40) stimulates GLP‐1 secretion from isolated perfused rat small intestine. Physiol Rep 3: e12551. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen LJ, Esterhazy D, Kim SH, Lemetre C, Aguilar RR, Gordon EA et al (2017). Commensal bacteria make GPCR ligands that mimic human signalling molecules. Nature 549: 48–53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cornall LM, Hryciw DH, Mathai ML, McAinch AJ (2015). Direct activation of the proposed anti‐diabetic receptor, GPR119 in cardiomyoblasts decreases markers of muscle metabolic activity. Mol Cell Endocrinol 402: 72–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cvijanovic N, Isaacs NJ, Rayner CK, Feinle‐Bisset C, Young RL, Little TJ (2017). Duodenal fatty acid sensor and transporter expression following acute fat exposure in healthy lean humans. Clin Nutr 36: 564–569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diep TA, Madsen AN, Holst B, Kristiansen MM, Wellner N, Hansen SH et al (2011). Dietary fat decreases intestinal levels of the anorectic lipids through a fat sensor. FASEB J 25: 765–774. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diep TA, Madsen AN, Krogh‐Hansen S, Al‐Shahwani M, Al‐Sabagh L, Holst B et al (2014). Dietary non‐esterified oleic Acid decreases the jejunal levels of anorectic N‐acylethanolamines. PLoS One 9: e100365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DiPatrizio NV, Piomelli D (2015). Intestinal lipid‐derived signals that sense dietary fat. J Clin Invest 125: 891–898. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Douglass JD, Zhou YX, Wu A, Zadrogra JA, Gajda AM, Lackey AI et al (2015). Global deletion of MGL in mice delays lipid absorption and alters energy homeostasis and diet‐induced obesity. J Lipid Res 56: 1153–1171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ekberg JH, Hauge M, Kristensen LV, Madsen AN, Engelstoft MS, Husted AS et al (2016). GPR119, a major enteroendocrine sensor of dietary triglyceride metabolites co‐acting in synergy with FFA1 (GPR40). Endocrinology 157: 4561–4569. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Esposito G, Capoccia E, Turco F, Palumbo I, Lu J, Steardo A et al (2014). Palmitoylethanolamide improves colon inflammation through an enteric glia/toll like receptor 4‐dependent PPAR‐α activation. Gut 63: 1300–1312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fegley D, Gaetani S, Duranti A, Tonini A, Mor M, Tarzia G et al (2005). Characterization of the fatty acid amide hydrolase inhibitor cyclohexyl carbamic acid 3`‐carbamoyl‐biphenyl‐3‐yl ester (URB597): effects on anandamide and oleoylethanolamide deactivation. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 313: 352–358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feinle C, O'Donovan D, Doran S, Andrews JM, Wishart J, Chapman I et al (2003). Effects of fat digestion on appetite, APD motility, and gut hormones in response to duodenal fat infusion in humans. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol 284: G798–G807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feinle‐Bisset C (2016). Upper gastrointestinal sensitivity to meal‐related signals in adult humans – relevance to appetite regulation and gut symptoms in health, obesity and functional dyspepsia. Physiol Behav 162: 69–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferreira JG, Tellez LA, Ren X, Yeckel CW, de Araujo IE (2012). Regulation of fat intake in the absence of flavor signaling. J Physiol 590: 953–972. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flint A, Raben A, Astrup A, Holst JJ (1998). Glucagon‐like peptide 1 promotes satiety and suppresses energy intake in humans. J Clin Invest 101: 515–520. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fu J, Astarita G, Gaetani S, Kim J, Cravatt BF, Mackie K et al (2007). Food intake regulates oleoylethanolamide formation and degradation in the proximal small intestine. J Biol Chem 282: 1518–1528. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fu J, Gaetani S, Oveisi F, LoVerme J, Serrano A, Rodríguez de Fonseca F et al (2003). Oleoylethanolamide regulates feeding and body weight through activation of the nuclear receptor PPARa. Nature 425: 90–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fu J, Kim J, Oveisi F, Astarita G, Piomelli D (2008). Targeted enhancement of oleoylethanolamide production in proximal small intestine induces across‐meal satiety in rats. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 295: R45–R50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaetani S, Oveisi F, Piomelli D (2003). Modulation of meal pattern in the rat by anorexic lipid mediator oleoylethanolamide. Neuropsychopharmacology 28: 1311–1316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grabner GF, Zimmermann R, Schicho R, Taschler U (2017). Monoglyceride lipase as a drug target: at the crossroads of arachidonic acid metabolism and endocannabinoid signaling. Pharmacol Ther 175: 35–46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grillo SL, Keereetaweep J, Grillo MA, Chapman KD, Koulen P (2013). N‐palmitoylethanolamine depot injection increased its tissue levels and those of other acylethanolamide lipids. Drug Des Devel Ther 7: 747–752. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gross B, Pawlak M, Lefebvre P, Staels B (2017). PPARs in obesity‐induced T2DM, dyslipidaemia and NAFLD. Nat Rev Endocrinol 13: 36–49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guijarro A, Fu J, Astarita G, Piomelli D (2010). CD36 gene deletion decreases oleoylethanolamide levels in small intestine of free‐feeding mice. Pharmacol Res 61: 27–33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guzmán M, Lo Verme J, Fu J, Oveisi F, Blázquez C, Piomelli D (2004). Oleoylethanolamide stimulates lipolysis by activating the nuclear receptor peroxisome proliferator‐activated receptor a (PPAR‐a). J Biol Chem 279: 27849–27854. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hallmark, B. D. , Rose, K. , Jepuri, J. N. , and Marulappa, S . Dietary supplementattion of RiduZone (oleoylethanolamide/OEA capsule). Results in weight loss in humans: The first‐in‐human case studies. Conference: Overcomming Obesity 2016, Chicago, IL. Poster abstract CHI19. 2016. Ref Type: Abstract

- Hankir MK, Seyfried F, Hintschich CA, Diep TA, Kleberg K, Kranz M et al (2017). Gastric bypass surgery recruits a gut PPAR‐α‐striatal D1R pathway to reduce fat appetite in obese rats. Cell Metab 25: 335–344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hansen HS (2013). Effect of diet on tissue levels of palmitoylethanolamide. CNS Neurol Disord Drug Targets 12: 17–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hansen HS (2014). Role of anorectic N‐acylethanolamines in intestinal physiology and satiety control with respect to dietary fat. Pharmacol Res 86: 18–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hansen HS, Rosenkilde MM, Holst JJ, Schwartz TW (2012). GPR119 as a fat sensor. Trends Pharmacol Sci 33: 374–381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hansen KB, Rosenkilde MM, Knop FK, Wellner N, Diep TA, Rehfeld JF et al (2011). 2‐Oleoyl glycerol is a GPR119 agonist and signals GLP‐1 release in humans. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 96: E1409–E1417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harding SD, Sharman JL, Faccenda E, Southan C, Pawson AJ, Ireland S et al (2018). The IUPHAR/BPS Guide to PHARMACOLOGY in 2018: updates and expansion to encompass the new guide to IMMUNOPHARMACOLOGY. Nucl Acids Res 46: D1091–D1106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hassing HA, Engelstoft MS, Sichlau RM, Madsen AN, Rehfeld JF, Pedersen J et al (2016a). Oral 2‐oleyl glyceryl ether improves glucose tolerance in mice through the GPR119 receptor. Biofactors 42: 665–673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hassing HA, Fares S, Larsen O, Pad H, Hauge M, Jones RM et al (2016b). Biased signaling of lipids and allosteric actions of synthetic molecules for GPR119. Biochem Pharmacol 119: 66–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hauge M, Ekberg JP, Engelstoft MS, Timshel P, Madsen AN, Schwartz TW (2017). Gq and Gs signaling acting in synergy to control GLP‐1 secretion. Mol Cell Endocrinol 449: 64–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu YW, Yang JY, Ma X, Chen ZP, Hu YR, Zhao JY et al (2014). A lincRNA‐DYNLRB2‐2/GPR119/GLP‐1R/ABCA1‐dependent signal transduction pathway is essential for the regulation of cholesterol homeostasis. J Lipid Res 55: 681–697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hussain Z, Uyama T, Tsuboi K, Ueda N (2017). Mammalian enzymes responsible for the biosynthesis of N‐acylethanolamines. Biochim Biophys Acta 1862: 1546–1561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Husted AS, Trauelsen M, Rudenko O, Hjorth SA, Schwartz TW (2017). GPCR‐mediated signaling of metabolites. Cell Metab 25: 777–796. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Igarashi M, DiPatrizio NV, Narayanaswami V, Piomelli D (2015). Feeding‐induced oleoylethanolamide mobilization is disrupted in the gut of diet‐induced obese rodents. Biochim Biophys Acta 1851: 1218–1226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inoue M, Tsuboi K, Okamoto Y, Hidaka M, Uyama T, Tsutsumi T et al (2017). Peripheral tissue levels and molecular species compositions of N‐acyl‐phosphatidylethanolamine and its metabolites in mice lacking N‐acyl‐phosphatidylethanolamine‐specific phospholipase D. J Biochem 162: 449–458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iwasaki Y, Saito O, Tanabe M, Inayoshi K, Kobata K, Uno S et al (2008). Monoacylglycerols activate capsaicin receptor, TRPV1. Lipids 43: 471–483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jin S, Martinelli DC, Zheng X, Tessier‐Lavigne M, Fan CM (2015). Gas1 is a receptor for sonic hedgehog to repel enteric axons. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 112: E73–E80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karimian AE, Ramachandran D, Weibel S, Arnold M, Romano A, Gaetani S et al (2014). Vagal afferents are not necessary for the satiety effect of the gut lipid messenger oleoylethanolamide(OEA). Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 307: R167–R178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karwad MA, Macpherson T, Wang B, Theophilidou E, Sarmad S, Barrett DA et al (2017). Oleoylethanolamine and palmitoylethanolamine modulate intestinal permeability in vitro via TRPV1 and PPARα. FASEB J 31: 469–481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khaliullina H, Bilgin M, Sampaio JL, Shevchenko A, Eaton S (2015). Endocannabinoids are conserved inhibitors of the Hedgehog pathway. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 112: 3415–3420. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khasabova IA, Xiong Y, Coicou LG, Piomelli D, Seybold V (2012). Peroxisome proliferator‐activated receptor α mediates acute effects of palmitoylethanolamide on sensory neurons. J Neurosci 32: 12735–12743. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kleberg K, Hassing HA, Hansen HS (2014a). Classical endocannabinoid‐like compounds and their regulation by nutrients. Biofactors 40: 363–372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kleberg K, Jacobsen AK, Ferreira JG, Windelov JA, Rehfeld JF, Holst JJ et al (2015). Sensing of triacylglycerol in the gut: different mechanisms for fatty acids and 2‐monoacylglcerol. J Physiol 593: 2097–2109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kleberg K, Nielsen LL, Stuhr‐Hansen N, Nielsen J, Hansen HS (2014b). Evaluation of the immediate vascular stability of lipoprotein lipase‐generated 2‐monoacylglycerol in mice. Biofactors 40: 596–602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lan H, Vassileva G, Corona A, Liu L, Baker H, Golovko A et al (2009). GPR119 is required for physiological regulation of glucagon‐like peptide‐1 secretion but not for metabolic homeostasis. J Endocrinol 201: 1058–1066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee JW, Huang BX, Kwon H, Rashid MA, Kharebava G, Desai A et al (2016). Orphan GPR110 (ADGRF1) targeted by N‐docosahexaenoylethanolamine in development of neurons and cognitive function. Nat Commun 7: 13123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li W, Yang X, Xing S, Bian F, Yao W, Bai X et al (2014). Endogenous ceramide contributes to the transcytosis of ox LDL across endothelial cells and promotes its subendothelial retention in vascular wall. Oxid Med Cell Longev 2014: 823071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin XH, Yuece B, Li YY, Feng YJ, Feng JY, Yu LY et al (2011). A novel CB receptor GPR55 and its ligands are involved in regulation of gut movement in rodents. Neurogastroenterol Motil 23: 862–e342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lo Verme J, Fu J, Astarita G, La Rana G, Russo R, Calignano A et al (2005). The nuclear receptor peroxisome proliferator‐activated receptor‐a mediates the anti‐inflammatory actions of palmitoylethanolamide. Mol Pharmacol 67: 15–19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Long JZ, LaCava M, Jin X, Cravatt BF (2011). An anatomical and temporal portrait of physiological substrates for fatty acid amide hydrolase. J Lipid Res 52: 337–344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma B, Zhu J, Tan J, Mao Y, Tang L, Shen C et al (2017). Gpr110 deficiency decelerates carcinogen‐induced hepatocarcinogenesis via activation of the IL‐6/STAT3 pathway. Am J Cancer Res 7: 433–447. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mandoe MJ, Hansen KB, Hartmann B, Rehfeld JF, Holst JJ, Hansen HS (2015). The 2‐monoacylglycerol moiety of dietary fat appears to be responsible for the fat‐induced release of GLP‐1 in humans. Am J Clin Nutr 102: 548–555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Melis M, Carta S, Fattore L, Tolu S, Yasar S, Goldberg SR et al (2010). Peroxisome proliferator‐activated receptors‐alpha modulate dopamine cell activity through nicotinic receptors. Biol Psychiatry 68: 256–264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller S, Hu SS, Leishman E, Morgan D, Wager‐Miller J, Mackie K et al (2017). A GPR119 signaling system in the murine eye regulates intraocular pressure in a sex‐dependent manner. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 58: 2930–2938. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moss CE, Glass LL, Diakogiannaki E, Pais R, Lenaghan C, Smith DM et al (2015). Lipid derivatives activate GPR119 and trigger GLP‐1 secretion in primary murine L‐cells. Peptides 77: 16–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Movahed P, Jönsson BAG, Birnir B, Wingstrand JA, Jorgensen TD, Ermund A et al (2005). Endogenous unsaturated C18N‐acylethanolamines are vanilloid receptor (TRPV1) agonists. J Biol Chem 280: 38496–38504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mu HL, Porsgaard T (2005). The metabolism of structured triacylglycerols. Prog Lipid Res 44: 430–448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murota K, Storch J (2005). Uptake of micellar long‐chain fatty acid and sn‐2‐monoacylglycerol into human intestinal Caco‐2 cells exhibits characteristics of protein‐mediated transport. J Nutr 135: 1626–1630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nelson DW, Gao Y, Yen MI, Yen CL (2014). Intestine‐specific deletion of Acyl CoA: monoacylglycerol acyltransferase (MGAT)2 protects mice from diet‐induced obesity and glucose intolerance. J Biol Chem 289: 17338–17349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nielsen MJ, Petersen G, Astrup A, Hansen HS (2004). Food intake is inhibited by oral oleoylethanolamide. J Lipid Res 45: 1027–1029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ogura Y, Parsons WH, Kamat SS, Cravatt BF (2016). A calcium‐dependent acyltransferase that produces N‐acyl phosphatidylethanolamines. Nat Chem Biol 12: 669–671. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oveisi F, Gaetani S, Eng KT‐P, Piomelli D (2004). Oleoylethanolamide inhibits food intake in free‐feeding rats after oral administration. Pharmacol Res 49: 461–466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petersen G, Sorensen C, Schmid PC, Artmann A, Tang‐Christensen M, Hansen SH et al (2006). Intestinal levels of anandamide and oleoylethanolamide in food‐deprived rats are regulated through their precursors. Biochim Biophys Acta 1761: 143–150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petrosino S, Di Marzo V (2017). The pharmacology of palmitoylethanolamide and first data on the therapeutic efficacy of some of its new formulations. Br J Pharmacol 174: 1349–1365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petrosino S, Schiano MA, Cerrato S, Fusco M, Puigdemont A, De PL et al (2016). The anti‐inflammatory mediator palmitoylethanolamide enhances the levels of 2‐arachidonoyl‐glycerol and potentiates its actions at TRPV1 cation channels. Br J Pharmacol 173: 1154–1162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piomelli D (2013). A fatty gut feeling. Trends Endocrinol Metab 24: 332–341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pontis S, Ribeiro A, Sasso O, Piomelli D (2016). Macrophage‐derived lipid agonists of PPAR‐α as intrinsic controllers of inflammation. Crit Rev Biochem Mol Biol 51: 7–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poursharifi P, Madiraju SRM, Prentki M (2017). Monoacylglycerol signalling and ABHD6 in health and disease. Diabetes Obes Metab 19 (Suppl 1): 76–89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Proulx K, Cota D, Castañeda TR, Tshöp MH, D'Alessio DA, Tso P et al (2005). Mechanisms of oleoylethanolamide‐induced changes in feeding behaviour and motor activity. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 289: 729–737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Psichas A, Larraufie PF, Goldspink DA, Gribble FM, Reimann F (2017). Chylomicrons stimulate incretin secretion in mouse and human cells. Diabetologia 60: 2475–2485. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Psichas A, Reimann F, Gribble FM (2015). Gut chemosensing mechanisms. J Clin Invest 125: 908–917. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rahnasto‐Rilla M, Kokkola T, Jarho E, Lahtela‐Kakkonen M, Moaddel R (2016). N‐acylethanolamines bind to SIRT6. Chembiochem 17: 77–81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodríguez de Fonseca F, Navarro M, Gómez R, Escuredo L, Nava F, Fu J et al (2001). An anorexic lipid mediator regulated by feeding. Nature 414: 209–212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Romano A, Gallelli CA, Koczwara JB, Braegger FE, Vitalone A, Falchi M et al (2017). Role of the area postrema in the hypophagic effects of oleoylethanolamide. Pharmacol Res 122: 20–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ryberg E, Larsson N, Sjogren S, Hjorth S, Hermansson NO, Leonova J et al (2007). The orphan receptor GPR55 is a novel cannabinoid receptor. Br J Pharmacol 152: 1092–1101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sankoda A, Harada N, Iwasaki K, Yamane S, Murata Y, Shibue K et al (2017). Long chain free fatty acid receptor GPR120 mediates oil‐induced GIP secretion through CCK in male mice. Endocrinology 158: 1172–1180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sarnelli G, Gigli S, Capoccia E, Iuvone T, Cirillo C, Seguella L et al (2016). Palmitoylethanolamide exerts antiproliferative effect and downregulates VEGF signaling in Caco‐2 human colon carcinoma cell line through a selective PPAR‐α‐dependent inhibition of Akt/mTOR pathway. Phytother Res 30: 963–970. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmid HHO, Schmid PC, Natarajan V (1990). N‐acylated glycerophospholipids and their derivatives. Prog Lipid Res 29: 1–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz GJ, Fu J, Astarita G, Li X, Gaetani S, Campolongo P et al (2008). The lipid messenger OEA links dietary fat intake to satiety. Cell Metab 8: 281–288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shore DM, Reggio PH (2015). The therapeutic potential of orphan GPCRs, GPR35 and GPR55. Front Pharmacol 6: 69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steinert RE, Beglinger C, Langhans W (2016). Intestinal GLP‐1 and satiation: from man to rodents and back. Int J Obes (Lond) 40: 198–205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taschler U, Hasenoehrl C, Storr M, Schicho R (2017). Cannabinoid receptors in regulating the GI tract: experimental evidence and therapeutic relevance. Handb Exp Pharmacol 239: 343–362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tellez LA, Medina S, Han W, Ferreira JG, Licona‐Limon P, Ren X et al (2013). A gut lipid messenger links excess dietary fat to dopamine deficiency. Science 341: 800–802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tourino C, Oveisi F, Lockney J, Piomelli D, Maldonado R (2010). FAAH deficiency promotes energy storage and enhances the motivation for food. Int J Obes (Lond) 34: 557–568. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Voitychuk OI, Asmolkova VS, Gula NM, Sotkis GV, Galadari S, Howarth FC et al (2012). Modulation of excitability, membrane currents and survival of cardiac myocytes by N‐acylethanolamines. Biochim Biophys Acta 182: 1167–1176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang B, Rong X, Duerr MA, Hermanson DJ, Hedde PN, Wong JS et al (2016). Intestinal phospholipid remodeling is required for dietary‐lipid uptake and survival on a high‐fat diet. Cell Metab 23: 492–504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wei BQ, Mikkelsen TS, McKinney MK, Lander ES, Cravatt BF (2006). A second fatty acid amide hydrolase with variable distribution among placental mammals. J Biol Chem 281: 36569–36578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yen CL, Nelson DW, Yen MI (2015). Intestinal triacylglycerol synthesis in fat absorption and systemic energy metabolism. J Lipid Res 56: 489–501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Young SG, Zechner R (2013). Biochemistry and pathophysiology of intravascular and intracellular lipolysis. Genes Dev 27: 459–484. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]