Key Points

Question

What is the association between changes in state Medicaid eligibility thresholds and deaths due to substance use disorder?

Findings

This economic evaluation of publicly available data on state policies, demographic characteristics, and mortality demonstrated an association between expanded Medicaid eligibility thresholds and reduced deaths due to substance use disorder. Adjusting for state characteristics, additional substance use disorder–related deaths were observed in states that reduced Medicaid eligibility from 2002 to 2015, whereas fewer deaths were observed in states that increased Medicaid over this period.

Meaning

Expanded Medicaid eligibility thresholds were associated with a reduction in substance use disorder–related deaths during the current US opioid epidemic.

This economic evaluation uses state-level data to estimate the association between eligibility thresholds for state Medicare coverage and deaths related to substance use disorders.

Abstract

Importance

The United States is currently facing an epidemic of deaths related to substance use disorder (SUD), with totals exceeding those due to motor vehicle crashes and gun violence. The epidemic has led to decreased life expectancy in some populations. In recent years, Medicaid eligibility has expanded in some states, and the association of this expansion with SUD-related deaths is yet to be examined.

Objective

To examine the association between eligibility thresholds for state Medicaid coverage and SUD-related deaths.

Design, Setting, and Participants

Economic evaluation study using a retrospective analysis of state-level data between 2002 and 2015 to determine the association between the Medicaid eligibility threshold and SUD-related deaths, controlling for other relevant policies, state socioeconomic characteristics, fixed effects, and a time trend. Policy variables were lagged by 1 year to allow time for associations to materialize. Data were collected and analyzed from 2016 to 2017.

Exposures

The policy of interest was the state Medicaid eligibility threshold, ie, the highest allowed income that qualifies a person for Medicaid, expressed as a percentage of the federal poverty level. State policies related to mental health, overdose treatment, and law enforcement of drug crimes were included as controls.

Main Outcomes and Measures

The primary outcome was number of SUD-related deaths, obtained from data provided by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Results

Across 700 state-year observations, the mean (SD) number of SUD-related deaths was 21.15 (6.05) per 100 000 population. Between 2002 and 2015, the national SUD-related death rate increased from 16.0 to 27.5 per 100 000, while the average Medicaid eligibility threshold increased from 87.2% to 97.1% of the federal poverty level. Over this period, every 100–percentage point increase in the Medicaid eligibility threshold (eg, from 50% to 150% of the federal poverty level) was associated with 1.373 (95% CI, −2.732 to −0.014) fewer SUD-related deaths per 100 000 residents, a reduction of 6.50%. In the 22 states with net contractions in eligibility thresholds between 2005 and 2015, an estimated increase of 570 SUD-related deaths (95% CI, −143 to 1283) occurred. In the 28 states that increased eligibility thresholds, an estimated 1045 SUD-related deaths (95% CI, −209 to 2299) may have been prevented.

Conclusions and Relevance

These findings suggest that the overall increase in SUD-related deaths between 2002 and 2015 may have been greater had the average eligibility threshold for Medicaid not increased over this period. Broader eligibility for Medicaid coverage may be one tool to help reduce SUD-related deaths.

Introduction

Deaths from substance use disorders (SUD), defined as recurring use of alcohol and/or drugs that causes significant clinical and functional impairment,1 have reached epidemic proportions in the United States. Since the mid-1980s, SUD-related deaths in the United States have increased almost 3-fold, and the increase has accelerated in recent years.2,3 Beginning in 2009, drug-induced deaths began exceeding deaths from motor vehicle crashes.4 In 2014, there were 49 714 drug-induced deaths in the United States, more than deaths due to motor vehicle crashes (35 398) or firearm injury (33 594).5 More than 60% of drug overdose deaths in 2014 involved an opioid, such as methadone, heroin, and other synthetic opioids (eg, fentanyl).3 Between 1999 and 2015, deaths due to all prescription drugs increased by 295%, driven predominantly by a 461% increase in opioid-related deaths.2,3,6

These SUD-related deaths are now contributing to a reversal in life expectancy gains among some US populations. While overall mortality rates in the United States have been declining since before 1940,7 mortality rates among middle-aged non-Hispanic white individuals have begun to increase owing to SUDs, alcohol-related liver disorders, and suicides.8,9 The economic burden associated with SUDs has been estimated to be more than $78 billion annually.10

As the epidemic of SUD-related deaths has grown in the United States, there are increasing calls for action.11,12,13 A variety of treatment programs and services for SUDs have demonstrated success in reducing drug-related overdoses,14,15 deaths,14 and health care service utilization14,15,16 without increasing costs to health plans and insurers.14,17,18 Individual treatment programs have been associated with reduction in nonfatal overdoses and inpatient care.15 The reduction in health care utilization at the patient level has also demonstrated downstream effects on health care expenditures and costs to public and private payers.14,15,17,18 From a social policy perspective, a comprehensive review of federal and state laws to increase availability of and access to mental health and SUD services demonstrated that these policies did not increase costs to insurance plans.15

As the largest US payer for mental health services, Medicaid has historically been one of the most important sources of SUD treatment.19 Under the Affordable Care Act (ACA), Medicaid and commercial plans offered through exchanges are required to cover mental health services, including SUD treatment,20,21 at the same level as other medical services, in compliance with the Mental Health Parity and Addiction Equity Act.22 There is some evidence that expanding Medicaid eligibility has increased access to and enrollment in SUD treatment programs at the state level.22,23,24,25 However, the association between Medicaid coverage and SUD-related deaths over several years has yet to be studied, particularly in an era of increasing SUD-related deaths.

The association between health care coverage and SUD-related deaths is unclear. Medicaid coverage can increase patient access to SUD treatment, which could help reduce SUD-related deaths. However, expanding patient access to health care more generally could increase exposure to prescription opioids or other controlled substances and possibly exacerbate SUD and deaths. A recent analysis by the US Department of Health and Human Services supported this claim.26 We sought to investigate the association between health care coverage and SUD outcomes. Specifically, our study used state-level data over a 14-year period to quantify the association between Medicaid coverage and SUD-related deaths and to determine whether coverage expansion is associated with fewer deaths.

Methods

Overview

We conducted a longitudinal regression analysis of US states over time, using publicly available data from 2002 through 2015 to estimate the association between state-level Medicaid eligibility thresholds and SUD-related deaths. According to the policy of Precision Health Economics, and in compliance with the guidance of the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act, the use of anonymized aggregate data does not require institutional review board approval; therefore, approval was not sought. This study was reported in accordance with the Consolidated Health Economic Evaluation Reporting Standards (CHEERS) reporting guideline.

Data Sources

We used data from publicly available sources, collected between 2016 and 2017. We obtained state-level annual SUD-related death data for 2002 to 2015 from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.27,28 We defined deaths as SUD related if the underlying cause of death was indicated as induced by either drugs or alcohol using the International Classification of Diseases, Tenth Revision. Approximately one-fifth of drug overdose deaths lack information on the specific drugs involved.29 Data regarding Medicaid eligibility during the study period were obtained from the Kaiser Family Foundation.30,31 States’ Medicaid eligibility policies differed by subpopulation (eg, pregnant women or disabled persons). We used the income eligibility threshold for Medicaid for parents as a measure of the extent of the state’s Medicaid coverage to capture the variation of policies across states and identify the effect of policy change. The eligibility threshold was defined as a percentage of the federal poverty level (FPL). Economic and demographic control variables were obtained from the US Census Bureau32 and Health Resources & Services Administration Area Health Resource Files.33

We used data on states’ Medicaid expansion status under the ACA from the Kaiser Family Foundation in sensitivity analyses. Data on mental health parity programs were retrieved from the National Conference of State Legislatures.34 We also used historical data on Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA) funding available from the SAMHSA website.1 Details on data sources are available in eAppendix 1 in the Supplement.

Statistical Analysis

We performed regression analyses on state-year–level data using population-weighted state fixed-effects models (also known as the within estimator) with robust standard errors clustered by state. We used a quadratic time trend to control for secular trends in SUD-related deaths. The rate of SUD-related deaths per 100 000 state population was the outcome variable, while the state Medicaid eligibility threshold was the policy variable of interest. To account for concurrent changes in the policy environment, we included as covariates several other state policies that could influence the number of patients with SUDs and SUD-related mortality. Such policies included mental health parity laws, state-supported naloxone treatment programs, good Samaritan laws, and differences in law enforcement related to drug crimes (eTable 1 and eTable 2 in the Supplement).

We lagged all policies, including the Medicaid eligibility threshold, by 1 year, thus examining outcomes in a state this year as a function of the state’s policies in the previous year, to allow time for the policies’ associations with SUD-related deaths to materialize and to reduce bias associated with reverse causality.

To control for other state characteristics that could be associated with the prevalence and outcomes of SUDs, we included the state’s unemployment rate, median household income, fraction of the state population with income below the FPL, and demographic measures (ie, the fractions of state population that were of black race, aged ≥65 years, and female) in the same year as the outcomes. All count variables were normalized to per 100 000 population. All dollar amounts were adjusted to 2016 US dollars using the Bureau of Labor Statistics Consumer Price Index.35 The complete specification is available in eTable 3 in the Supplement. All analyses were performed using Stata statistical software version 14 (StataCorp LLC).

Sensitivity Analysis

In addition to the base-case analysis described above, we tested whether our specification choices influenced our results. First, we conducted 3 sensitivity analyses: (1) replacing quadratic time trends with year–fixed effects; (2) rerunning the base-case regression 3 separate times with an additional covariate of either an indicator of ACA Medicaid expansion, an indicator of full mental health parity law, or the total dollar amount of SAMHSA funding per 100 000 population; and (3) removing population weights. To test for reverse causality, we measured the extent to which SUD-related deaths in a state were associated with the state’s policies the following year. We performed 1 regression for each policy as the dependent variable with the previous year’s SUD-related deaths and the current year’s demographic and socioeconomic controls and a quadratic time trend as explanatory variables. Finally, to test the hypothesis that Medicaid expansions worsen the SUD epidemic, we replicated the base-case analysis with a shortened, more recent panel, from 2010 to 2015. This was based on the Department of Health and Human Services study26 that reported that states that expanded Medicaid under the ACA, which was enacted in 2010, experienced a sharper increase in SUD-related deaths. Our sensitivity analysis tested whether this conclusion holds true when controlling for relevant policy and demographic variables. Additional details on the sensitivity analyses are available in eAppendix 2 in the Supplement.

Results

Descriptive Statistics

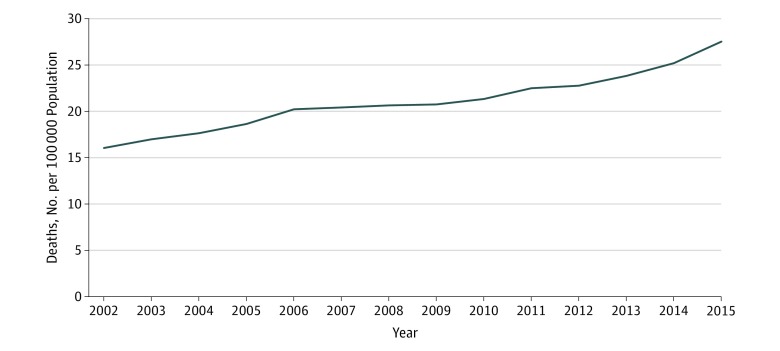

Across 700 state-year observations, the mean (SD) number of SUD-related deaths was 21.15 (6.05) per 100 000 population. A mean (SD) of 13% (8%) of a state’s population was black, 51% (1%) was female, and 13% (2%) was aged 65 years or older. The mean (SD) unemployment rate was 6.62 (2.08) per 100 000 population. Median household income was $58 071 and a mean (SD) of 14% (3%) of the state population had income below the FPL (eTable 1 in the Supplement). Figure 1 reports the trend in the average annual SUD-related deaths per 100 000 US population from 2002 to 2015. Overall, national SUD-related deaths increased from 16.0 deaths per 100 000 population (46 071 deaths) in 2002 to approximately 27.5 per 100 000 in 2015 (88 364). During the same period, the average Medicaid eligibility threshold increased from 87.2% of the FPL in 2002 to 97.1% in 2015. One reason for the change in Medicaid eligibility was the ACA: by 2015, 58% of states had expanded Medicaid under the ACA, bringing their eligibility thresholds to at least 138% of the FPL. We show state Medicaid eligibility thresholds over the study period in eTable 2 in the Supplement.

Figure 1. Substance Use Disorder–Related Deaths in the United States, 2002 to 2015.

Deaths are categorized as substance use disorder related if the underlying cause of death on the individual’s death certificate is identified as induced by drugs or alcohol. For diagnosis codes, see eAppendix 1 in the Supplement. Source: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention mortality data.27,28

Base-Case Model

Results from the regression analyses suggest that a higher Medicaid eligibility threshold was associated with decreased SUD-related deaths. Specifically, in our base-case sample of 538 state-years, every 100 percentage point increase in a state’s Medicaid eligibility threshold (eg, from 50% to 150% of FPL) was associated with 1.373 (95% CI, −2.732 to −0.014) fewer SUD-related deaths per 100 000 residents (eTable 3 in the Supplement), a reduction of 6.50%. In 2014, Minnesota had the highest eligibility threshold, 205% of the FPL. According to our results, if all states with Medicaid eligibility thresholds below Minnesota’s had increased their thresholds to 205% in 2014, there might have been 5207 (95% CI, −10 231 to −182) fewer SUD-related deaths nationwide in 2015 (Table 1), a 5.89% reduction. Similarly, if all states with thresholds below the median (133% of the FPL) in 2014 had increased their thresholds to 133%, there might have been 2359 (95% CI, −4635 to −83) fewer SUD-related deaths in 2015, a 2.67% reduction.

Table 1. Predicted Changes in National SUD-Related Deaths in 2015 Associated With Medicaid Eligibility Scenarios in 2014.

| Scenario | Predicted Change in SUD-Related Deaths, No. (95% CI)a | Change, % |

|---|---|---|

| Raising the Medicaid eligibility threshold in all states with thresholds below the median to the median threshold (133% of federal poverty level) | −2359 (−4635 to −83) | −2.67 |

| Raising the Medicaid eligibility threshold in all states to match the level of state with the highest threshold (205% of federal poverty level) | −5207 (−10 231 to −182) | −5.89 |

Abbreviation: SUD, substance use disorder.

Negative values indicate lives saved. Changes in SUD-related deaths are the predicted outcome associated with nationwide changes in the given policies. Predicted changes were estimated from a fixed-effects regression model of SUD-related deaths on Medicaid eligibility threshold with economic controls demographic controls and other policy controls.

Presence of state-supported naloxone programs, the number of drug courts per state, and the existence of medical cannabis programs were also associated with increases in SUD-related deaths in the base-case model (eTable 3 in the Supplement).

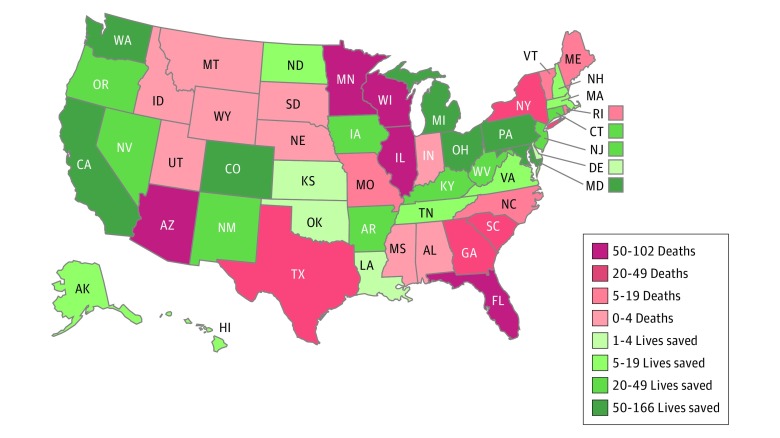

We observed differences across states. Figure 2 shows the association between cumulative lives saved (or lost) and changes in Medicaid eligibility thresholds from 2005 to 2015 by state. For each state in each year, we estimated the lives saved (or lost) associated with expansions (or contractions) in the Medicaid eligibility threshold. We summed across years to estimate the total lives saved or lost in the state. Over this period, in the 22 states with net contractions in Medicaid eligibility thresholds, we estimate 570 SUD-related deaths (bootstrapped 95% CI, −143 to 1283) may have been associated with these contractions. Conversely, in the 28 states with net increases in eligibility thresholds, we estimate 1045 SUD-related deaths (bootstrapped 95% CI, −209 to 2299) may have been averted in association with these increases. Note that states with net eligibility expansions could contract in some years and vice versa, and states that ended with high thresholds (such as Minnesota) may experience lives lost on net if contractions outweighed expansions over this period. This may explain why some states that ended up with high thresholds showed net lives lost and vice versa.

Figure 2. Estimated Substance Use Disorder–Related Deaths Associated With Changes in Medicaid Eligibility, 2005 to 2015.

Rhode Island only contains Medicaid eligibility data from 2011 to 2015.

We also observed regional differences in the potential lives saved in 2015 if all states had adopted the ACA Medicaid expansion in 2014, ranging from 6 in Maine (95% CI, 0-12) and Wyoming (95% CI, 0-13) to 449 (95% CI, 5-893) in Texas (Table 2). States with larger populations overall and larger populations with SUDs might be associated with more lives saved.

Table 2. Estimated SUD-Related Deaths Avoided if Nonexpansion States Had Expanded Medicaid in 2015.

| Statea | Estimated Deaths Avoided, No. (95% CI) | SUD-Related Deaths in 2015, No. |

|---|---|---|

| Alabama | 80 (1-159) | 1126 |

| Florida | 289 (3-576) | 5866 |

| Georgia | 140 (1-279) | 2096 |

| Idaho | 25 (0-50) | 464 |

| Kansas | 40 (0-80) | 627 |

| Louisiana | 73 (1-145) | 1289 |

| Maine | 6 (0-12) | 472 |

| Missouri | 96 (1-191) | 1610 |

| Mississippi | 45 (0-90) | 544 |

| Montana | 12 (0-25) | 346 |

| North Carolina | 128 (1-255) | 2551 |

| Nebraska | 22 (0-43) | 338 |

| Oklahoma | 49 (1-98) | 1281 |

| South Carolina | 48 (0-95) | 1288 |

| South Dakota | 10 (0-20) | 224 |

| Tennessee | 32 (0-63) | 2183 |

| Texas | 449 (5-893) | 4805 |

| Utah | 38 (0-75) | 933 |

| Virginia | 107 (1-213) | 1725 |

| Wisconsin | 30 (0-60) | 1532 |

| Wyoming | 6 (0-13) | 251 |

Abbreviation: SUD, substance use disorder.

States that already expanded Medicaid under the Affordable Care Act as of 2015 are not included in the table.

Sensitivity Analyses

The results from our sensitivity analyses were similar to those from the base-case model (eTable 4 in the Supplement). Across all analyses, an increase in the Medicaid eligibility threshold was associated with fewer SUD-related deaths. The number of drug courts and medical cannabis programs remained significantly associated with increased SUD-related deaths. The overall magnitudes of the estimated effects were similar, although statistical significance was weaker in some specifications. However, the number of SUD-related deaths was not significantly associated with changes in Medicaid eligibility thresholds (eTable 5 in the Supplement). Finally, the base-case model with a shortened panel data set (2010-2015) indicated that most policy measures, with the exception of medical cannabis and mandatory minimum sentencing, lost their significance (eTable 6 in the Supplement). This suggests that a longer panel data set may help clarify the association between SUD-related deaths and changes in Medicaid access, and, consequently, that the data used by the Department of Health and Human Services study26 were likely too short in duration to make firm conclusions.

Discussion

During a period of steady increases in SUD-related deaths nationally between 2002 and 2015, states have implemented various policies that may directly or indirectly increase treatment for SUDs and mitigate related deaths. One relevant policy is Medicaid eligibility expansion. By 2015, 29 states had expanded Medicaid eligibility to 138% of the FPL under the ACA, with 2 more (Louisiana and Montana) expanding eligibility in 2016.30,31,36 Although changes in Medicaid eligibility resulted from state and federal policies that did not necessarily target SUDs, our analysis suggests that more SUD-related deaths may have occurred in the absence of Medicaid eligibility expansions.

We found that expanding Medicaid eligibility was associated with reduced SUD-related deaths. Specifically, each 100–percentage point increase in the Medicaid eligibility threshold as a percentage of the FPL (eg, from 50% to 150% of FPL) was associated with 1.373 (95% CI, −2.732 to −0.014) fewer SUD-related deaths per 100 000 residents, a reduction of 6.50%. Consequently, raising states’ Medicaid eligibility thresholds in 2014 so that all states at least reached the median (133% of the FPL) could potentially have been associated with 2359 fewer SUD-related deaths (95% CI, −4635 to −83) in 2015, and increasing all states’ thresholds to the most generous threshold across the states in 2014 (205% of FPL) could potentially have been associated with 5207 fewer deaths (95% CI, −10 231 to −182) in 2015.

The Medicaid eligibility threshold increase was the only policy in our analysis found to be significantly associated with reduced SUD-related deaths. Mental health parity, mandatory minimum sentencing, and good Samaritan laws showed negligible evidence of association with SUD-related deaths. Funding from SAMHSA in the following year, the number of drug courts, and existence of medical cannabis programs were significantly associated with increases in SUD-related deaths. These seemingly surprising findings may be the result of reverse causality, as supported by the results from our sensitivity analysis. That is, states experiencing a more severe SUD epidemic would be more likely to implement SUD-specific policies. For example, states with higher rates of SUD would likely be interested in increasing the number of drug courts, as they are an effective justice intervention in treating SUDs.37,38,39,40,41 In contrast, Medicaid policies are often determined by a more complex interaction of the federal and state policy environments and are, therefore, less responsive to the prevalence of SUDs or other events in the state. Results of our sensitivity analysis support this interpretation.

The results of this study suggest broader Medicaid eligibility as a potential policy option to help reduce SUD-related deaths. While individual SUD treatment and overdose prevention programs have demonstrated reductions of SUD-related deaths at a local level, broader Medicaid eligibility may affect more patients with SUDs and the overall health care system. The Massachusetts Medicaid specialty mental health managed care plan, established in 1992, offers 1 example.42 Between 1992 and 1993, freestanding detoxification program enrollment increased by 45.2%, methadone counseling by 15.5%, and methadone dosing by 20.2%. Additionally, inpatient substance abuse treatment decreased by 61.2%. Another example is the Oregon Health Plan Medicaid expansion,43 during which the percentage of Medicaid enrollees admitted to SUD treatment programs increased from 5.5% annually in 1994 to 7.7% in 1997. Those who accessed care through Medicaid eligibility expansion were 66% more likely to participate in SUD treatment than those who were enrolled in Medicaid because of a disability. Members with plans that reimbursed SUD treatment with a modified fee-for-service schedule were 55% more likely to access this treatment than members with case rate–based plans. More recently, a study conducted within the Massachusetts Medicaid program, MassHealth, demonstrated the association between Medicaid coverage for SUD treatments and deaths, specifically. Between 2003 and 2007, among 33 923 individuals with 53 557 treatment episodes for opioid dependence, mortality was evaluated for patients with buprenorphine treatment, methadone treatment, behavioral health outpatient treatment, and no treatment. Compared with those treated with buprenorphine, mortality rates for methadone treatment recipients were similar; however, mortality rates were 75% greater for those receiving behavioral health treatment only and more than 2 times greater for those receiving no treatment. In summary, the results of our study are consistent with previously published evidence that supports an association between Medicaid eligibility expansion, increased access to and participation in SUD treatment, and reduced SUD-related deaths.

While this study and others demonstrate that access to Medicaid programs is associated with mitigation of adverse health outcomes for certain subpopulations, including people with SUDs, there is also evidence that shows no improvement in health outcomes in some state Medicaid programs and populations. Critics of Medicaid cite long wait times,44 physician unwillingness to take on Medicaid patients,45 later-stage treatment of preventable diseases and conditions,46,47 and higher in-hospital mortality rates compared with privately insured populations.48 A more recent study assessed Medicaid enrollment for low-income adults in Oregon with a lottery-based opportunity for application.49 Researchers found that Medicaid coverage was beneficial in that it was associated with increased probability of diagnosing and treating diabetes and depression, increased health care service utilization, improved perceived health-related quality of life among enrollees, and reduced financial burden. However, they found no association with clinical measures of blood pressure, hypertension, cholesterol, hypercholesterolemia, glycated hemoglobin, or depression. Additionally, Medicaid expansion comes at a cost. Under the ACA, states that expand Medicaid pay 10% of the additional cost, while the federal government pays the other 90%. This is funded through taxation, which could distort individuals’ labor supply and investment decisions. The populations that may benefit from expanded Medicaid services are likely not those contributing the most funding through taxation. It is important to note the shortcomings of state Medicaid programs, but also to highlight where Medicaid could contribute to improving health-related outcomes, including SUD-related death reduction and lives saved.

Limitations

Our study has a number of limitations. First, state Medicaid policies are complex, and our measure of Medicaid eligibility captured only 1 dimension of states’ Medicaid policies. Choosing the eligibility thresholds for parents provided greater variation in policies between states over the entire study period than did eligibility for childless adults, which was necessary to identify the effect of the change in policy. Additionally, parents represent a majority of the US adult population and a majority of younger US adults aged 18 to 40 years.50 However, we could not distinguish the effects of coverage expansion from other policy characteristics, such as whether states with more generous eligibility policies for parents also have generous policies for other groups (eg, blind and disabled individuals) or whether they offer more generous coverage of medical services and have better access to care. Therefore, we were unable to identify the particular components of Medicaid that had the greatest association with changes in SUD-related deaths. Moreover, our estimation of the association between Medicaid eligibility thresholds and SUD-related deaths relies on states with large changes in thresholds for identification. Second, our study relies on detailed cause-of-death data, which have known limitations in coding accuracy.51,52 Third, owing to the inherent limitations of observational data, our regression results are associations that may not reflect causal effects. While our interpretations of these results suggest causation, we maintain that these relationships cannot be absolutely proven. Despite these limitations, our results suggest that increased Medicaid coverage may be a tool to help combat the opioid epidemic and potentially reduce SUD-related deaths.

Conclusions

Given the current policy debates over proposed changes to Medicaid, continued evaluation of Medicaid policies and their association with SUD-related (and other) health outcomes is warranted. In particular, investigating the specific mechanism by which Medicaid could reduce SUD-related deaths may inform future policies and strategies for mitigating the current epidemic.

eAppendix 1. Data Sources

eTable 1. Summary Statistics

eTable 2. Medicaid Eligibility Threshold as a Proportion of the Federal Poverty Level

eTable 3. Fixed Effects Regression Results

eAppendix 2. Results of Sensitivity Analyses

eTable 4. Main Sensitivity Analyses

eTable 5. Sensitivity Analysis Measuring Whether SUD Deaths in Previous Years Predict Policy in Current Year

eTable 6. Sensitivity Analysis Measuring Whether a Shortened Panel Data Demonstrated a Significant Relationship Between SUD Deaths and Medicaid Expansions

eReferences

References

- 1.Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration SAMHSA grant awards by state. https://www.samhsa.gov/grants-awards-by-state. Accessed January 25, 2017.

- 2.Warner M, Chen LH, Makuc DM, Anderson RN, Miniño AM. Drug poisoning deaths in the United States, 1980-2008. NCHS Data Brief. 2011;(81):-. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rudd RA, Seth P, David F, Scholl L. Increases in drug and opioid-involved overdose deaths—United States, 2010-2015. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2016;65(50-51):1445-1452. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm655051e1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kochanek KD, Xu J, Murphy SL, Miniño AM, Kung H-C. Deaths: final data for 2009. Natl Vital Stat Rep. 2011;60(3):1-116. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kochanek KD, Murphy SL, Xu J, Tejada-Vera B. Deaths: final data for 2014. Natl Vital Stat Rep. 2016;65(4):1-122. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.National Institute on Drug Abuse Overdose death rates. https://www.drugabuse.gov/related-topics/trends-statistics/overdose-death-rates. Accessed August 1, 2017.

- 7.Hoyert DL. 75 years of mortality in the United States, 1935-2010. NCHS Data Brief. 2012;1200(88):1-8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Case A, Deaton A. Mortality and morbidity in the 21st century. Brookings Pap Econ Act. 2017;2017:397-476. doi: 10.1353/eca.2017.0005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Case A, Deaton A. Rising morbidity and mortality in midlife among white non-Hispanic Americans in the 21st century. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2015;112(49):15078-15083. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1518393112 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Florence CS, Zhou C, Luo F, Xu L. The economic burden of prescription opioid overdose, abuse, and dependence in the United States, 2013. Med Care. 2016;54(10):901-906. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0000000000000625 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Murthy VH. Ending the opioid epidemic—a call to action. N Engl J Med. 2016;375(25):2413-2415. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1612578 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ault A. Opioid crisis in America: experts call for action. http://www.medscape.com/viewarticle/878336#vp_1. Published April 7, 2017. Accessed August 11, 2017.

- 13.President’s Commission on Combating Drug Addiction and the Opioid Crisis Draft Interim Report. Washington, DC: Office of National Drug Control Policy; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 14.McCarty D. Substance Abuse Treatment Benefits and Costs Knowledge Asset. The Robert Wood Johnson Foundation. 2008. http://saprp.org/knowledgeassets/knowledge_brief.cfm?KAID=1. Accessed August 3, 2017.

- 15.Stewart D, Gossop M, Marsden J. Reductions in non-fatal overdose after drug misuse treatment: results from the National Treatment Outcome Research Study (NTORS). J Subst Abuse Treat. 2002;22(1):1-9. doi: 10.1016/S0740-5472(01)00206-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Perron BE, Mowbray OP, Glass JE, Delva J, Vaughn MG, Howard MO. Differences in service utilization and barriers among blacks, Hispanics, and whites with drug use disorders. Subst Abuse Treat Prev Policy. 2009;4(1):3. doi: 10.1186/1747-597X-4-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jacob V, Qu S, Chattopadhyay S, et al. Economic effects of legislations and policies to expand mental health and substance abuse benefits in health insurance plans: a community guide systematic review. J Ment Health Policy Econ. 2015;18(1):39-48. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wickizer TM, Krupski A, Stark KD, Mancuso D, Campbell K. The effect of substance abuse treatment on Medicaid expenditures among general assistance welfare clients in Washington state. Milbank Q. 2006;84(3):555-576. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-0009.2006.00458.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Medicaid.gov Behavioral health services. https://www.medicaid.gov/medicaid/benefits/bhs/index.html. Accessed November 9, 2016.

- 20.Mann C. Essential Health Benefits in the Medicaid Program Baltimore, MD: Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Healthcare.gov. Health benefits and coverage: what Marketplace health insurance plans cover. https://www.healthcare.gov/coverage/what-marketplace-plans-cover/. Accessed August 1, 2017.

- 22.Boozang P, Bachrach D, Detty A. Coverage and Delivery of Adult Substance Abuse Services in Medicaid Managed Care. Baltimore, MD: Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Busch SH, Meara E, Huskamp HA, Barry CL. Characteristics of adults with substance use disorders expected to be eligible for Medicaid under the ACA. Psychiatr Serv. 2013;64(6):520-526. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.201200011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Garfield RL, Lave JR, Donohue JM. Health reform and the scope of benefits for mental health and substance use disorder services. Psychiatr Serv. 2010;61(11):1081-1086. doi: 10.1176/ps.2010.61.11.1081 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Haegerich TM, Paulozzi LJ, Manns BJ, Jones CM. What we know, and don’t know, about the impact of state policy and systems-level interventions on prescription drug overdose. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2014;145:34-47. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2014.10.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Johnson CK, Alonso-Zaldivar R Medicaid fueling opioid epidemic? new theory is challenged. Associated Press. https://www.apnews.com/a860fb7b0e0c4117b9420b3bcfb928c6. Published August 31, 2017. Accessed September 13, 2017.

- 27.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Opioid overdose: drug overdose deaths. http://www.cdc.gov/drugoverdose/data/statedeaths.html. Accessed November 10, 2016.

- 28.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Alcohol poisoning deaths infographic. http://www.cdc.gov/vitalsigns/alcohol-poisoning-deaths/infographic.html#infographic. Accessed November 10, 2016.

- 29.Rudd RA, Aleshire N, Zibbell JE, Gladden RM. Increases in drug and opioid overdose deaths—United States, 2000-2014. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2016;64(50-51):1378-1382. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6450a3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kaiser Family Foundation Status of state action on the Medicaid expansion decision. http://kff.org/health-reform/state-indicator/state-activity-around-expanding-medicaid-under-the-affordable-care-act. Accessed August 8, 2017.

- 31.Kaiser Family Foundation Medicaid income eligibility limits for parents, 2002-2017. http://www.kff.org/medicaid/state-indicator/medicaid-income-eligibility-limits-for-parents/?currentTimeframe=0&sortModel=%7B%22colId%22:%22Location%22,%22sort%22:%22asc%22%7D. Accessed January 24, 2017.

- 32.US Census Bureau QuickFacts. https://www.census.gov/quickfacts/fact/table/US/PST045216. Accessed February 1, 2017.

- 33.Health Resources & Services Administration. HRSA data warehouse: area health resources files. https://datawarehouse.hrsa.gov/topics/ahrf.aspx. Accessed February 1, 2017.

- 34.National Conference of State Legislatures Mental health benefits: state laws mandating of regulating. http://www.ncsl.org/research/health/mental-health-benefits-state-mandates.aspx#3. Published December 30, 2015. Accessed January 23, 2017.

- 35.Bureau of Labor Statistics Consumer Price Index for all urban consumers: all items. https://www.bls.gov/cpi/home.htm. Accessed July 10, 2017.

- 36.Advisory Board Where the states stand on Medicaid expansion: 31 states, D.C., have expanded Medicaid. https://www.advisory.com/daily-briefing/resources/primers/medicaidmap. Updated February 6, 2019. Accessed August 8, 2017.

- 37.Marinelli-Casey P, Gonzales R, Hillhouse M, et al. ; Methamphetamine Treatment Project Corporate Authors . Drug court treatment for methamphetamine dependence: treatment response and posttreatment outcomes. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2008;34(2):242-248. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2007.04.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Rawson RA, Marinelli-Casey P, Anglin MD, et al. ; Methamphetamine Treatment Project Corporate Authors . A multi-site comparison of psychosocial approaches for the treatment of methamphetamine dependence. Addiction. 2004;99(6):708-717. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2004.00707.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Marlowe DB, DeMatteo DS, Festinger DS. A sober assessment of drug courts. Federal Sentencing Reporter. 2003;16(2):153-157. doi: 10.1525/fsr.2003.16.2.153 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Belenko S. Research on drug courts: a critical review. Natl Drug Court Inst Rev. 1998;1(1):1-42. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Gottfredson DC, Najaka SS, Kearley B. Effectiveness of drug treatment courts: evidence from a randomized trial. Criminol Public Policy. 2003;2(2):171-196. doi: 10.1111/j.1745-9133.2003.tb00117.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Callahan JJ, Shepard DS, Beinecke RH, Larson MJ, Cavanaugh D. Mental health/substance abuse treatment in managed care: the Massachusetts Medicaid experience. Health Aff (Millwood). 1995;14(3):173-184. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.14.3.173 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Deck DD, McFarland BH, Titus JM, Laws KE, Gabriel RM. Access to substance abuse treatment services under the Oregon Health Plan. JAMA. 2000;284(16):2093-2099. doi: 10.1001/jama.284.16.2093 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Oostrom T, Einav L, Finkelstein A. Outpatient office wait times and quality of care for Medicaid patients. Health Aff (Millwood). 2017;36(5):826-832. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2016.1478 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Decker SL. In 2011 nearly one-third of physicians said they would not accept new Medicaid patients, but rising fees may help. Health Aff (Millwood). 2012;31(8):1673-1679. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2012.0294 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Bradley CJ, Given CW, Roberts C. Disparities in cancer diagnosis and survival. Cancer. 2001;91(1):178-188. doi: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Roetzheim RG, Pal N, Gonzalez EC, Ferrante JM, Van Durme DJ, Krischer JP. Effects of health insurance and race on colorectal cancer treatments and outcomes. Am J Public Health. 2000;90(11):1746-1754. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.90.11.1746 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Hasan O, Orav EJ, Hicks LS. Insurance status and hospital care for myocardial infarction, stroke, and pneumonia. J Hosp Med. 2010;5(8):452-459. doi: 10.1002/jhm.687 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Baicker K, Taubman SL, Allen HL, et al. ; Oregon Health Study Group . The Oregon experiment—effects of Medicaid on clinical outcomes. N Engl J Med. 2013;368(18):1713-1722. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa1212321 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Newport F, Wilke J. Desire for children still norm in US: US birthrate down but attitudes toward having children unchanged. Gallup Politics; https://news.gallup.com/poll/164618/desire-children-norm.aspx. Published September 25, 2013. Accessed January 29, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Cowper DC, Kubal JD, Maynard C, Hynes DM. A primer and comparative review of major US mortality databases. Ann Epidemiol. 2002;12(7):462-468. doi: 10.1016/S1047-2797(01)00285-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Redelings MD, Sorvillo F, Simon P. A comparison of underlying cause and multiple causes of death: US vital statistics, 2000-2001. Epidemiology. 2006;17(1):100-103. doi: 10.1097/01.ede.0000187177.96138.c6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

eAppendix 1. Data Sources

eTable 1. Summary Statistics

eTable 2. Medicaid Eligibility Threshold as a Proportion of the Federal Poverty Level

eTable 3. Fixed Effects Regression Results

eAppendix 2. Results of Sensitivity Analyses

eTable 4. Main Sensitivity Analyses

eTable 5. Sensitivity Analysis Measuring Whether SUD Deaths in Previous Years Predict Policy in Current Year

eTable 6. Sensitivity Analysis Measuring Whether a Shortened Panel Data Demonstrated a Significant Relationship Between SUD Deaths and Medicaid Expansions

eReferences