ABSTRACT

Objectives

This study tests the accuracy of the Injury Severity Score (ISS), New Injury Severity Score (NISS), Revised Trauma Score (RTS) and Trauma and Injury Severity Score (TRISS) in prediction of mortality in cases of geriatric trauma.

Design

Prospective observational study

Materials and methods

This was a prospective observational study on two hundred elderly trauma patients who were admitted to JSS Hospital, Mysuru over a consecutive period of 18 months between December 2016 to May 2018. On the day of admission, data were collected from each patient to compute the ISS, NISS, RTS, and TRISS.

Results

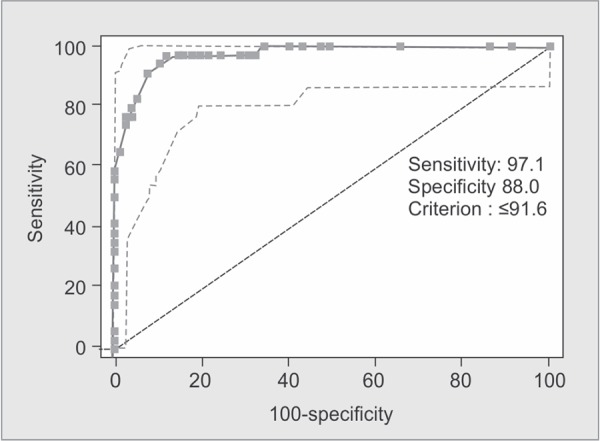

Mean age of patients was 66.35 years. Most common mechanism of injury was road traffic accident (94.0%) with mortality of 17.0%. The predictive accuracies of the ISS, NISS, RTS and the TRISS were compared using receiver operator characteristic (ROC) curves for the prediction of mortality. Best cutoff points for predicting mortality in elderly trauma patient using TRISS system was a score of 91.6 (sensitivity 97%, specificity of 88%, area under ROC curve 0.972), similarly cutoff point under the NISS was score of 17(91%, 93%, 0.970); for ISS best cutoff point was at 15(91%, 89%, 0.963) and for RTS it was 7.108(97%,80%,0.947). There were statistical differences among ISS, NISS, RTS and TRISS in terms of area under the ROC curve (p <0.0001).

Conclusion

TRISS was the strongest predictor of mortality in elderly trauma patients when compared to the ISS, NISS and RTS.

How to cite this article

Javali RH, Krishnamoorthy et al. Comparison of Injury Severity Score, New Injury Severity Score, Revised Trauma Score and Trauma and Injury Severity Score for Mortality Prediction in Elderly Trauma Patients. Indian J of Crit Care Med 2019;23(2):73-77.

Keywords: Elderly, Injury severity score, Mortality, New injury severity score, Revised trauma score, Trauma and injury severity score, Trauma

INTRODUCTION

Trauma is one of the leading causes of mortality and morbidity worldwide1. Injuries in the elderly are rapidly becoming a major public health concern2.

An appropriate scoring system to predict the mortality and morbidity in elderly is necessary because the elderly population has continued to grow and will continue to represent an increasing proportion of patients in our trauma bays. Additionally, elderly trauma patients have an increased morbidity and mortality for a given severity of injury, a decreased 5-year survival compared to their uninjured counterparts, as well as an increase in intensive care unit (ICU) stays and longer hospital length of stay3–6.

Nonetheless, aggressive treatment for elderly trauma patients is paramount, as patients who survive such events often return to independent living7.

Trauma scores were introduced more than 30 years ago for assigning numerical values to anatomical lesions and physiological changes after an injury. Physiological scores describe changes due to a trauma and translated by changes in vital signs and consciousness. Anatomical scores describe all the injuries recorded by clinical examination, imaging, surgery or autopsy. If physiological scores are used at first contact with the patient (for triage) and then repeated to monitor patient progress, anatomical scores are used after the diagnosis is complete, generally after patient discharge or postmortem. They are used to stratify trauma patients and to measure lesion severity. Scores that include both anatomical and physiological criteria (mixed scores) are useful for patient prognosis8.

Anatomical Scoring Systems

Abbreviated injury scale (AIS)

Injury severity score (ISS)

New injury severity score (NISS)

Organ injury scale (OIS)

Anatomic profile

International Classification of Diseases (ICD-9) Injury Severity Score (ICISS)

Physiological Scoring Systems

Revised trauma score

Glasgow coma score

APACHE scoring (Acute physiology and chronic health evaluation (APACHE I, II, III)

Combination of Anatomic and Physiological Scoring Systems

Trauma and injury severity scores (TRISS)

A severity characterization of trauma (ASCOT)

Injury Severity Score (ISS)

The injury severity score (ISS) is an anatomical scoring system that provides an overall score for patients with multiple injuries. Each injury is assigned an abbreviated injury scale (AIS) score and is allocated to one of six body regions. The highest AIS score in each body region is used. The three most severely injured body regions have their score squared and added together to produce the ISS score9.

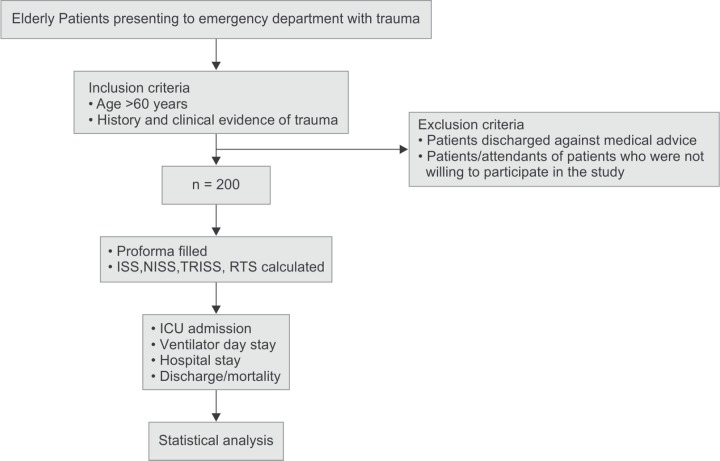

The ISS score takes values from 0 to 75. If an injury is assigned an AIS of 6 (Unsurvivable injury), the ISS score is automatically assigned to 75. The ISS score is virtually the only anatomical scoring system in use and correlates linearly with mortality, morbidity, hospital stay and other measures of severity (Graph 1).

Graph 1.

ROC curve showing validity of ISS score in predicting outcome (i.e. mortality)

Major trauma is considered when ISS> 15.

Bolorunduro etal. categorised and validated the ISS as follows10:

<9 = Mild

9 – 15 =Moderate

16–24 = Severe

>/=25 = Profound

The most important drawback of the ISS is that it only considers one injury in each body region. This leads to injuries being overlooked and to less severe injuries occurring in other body regions being included in the calculation over more serious ones in the same body region11.

New Injury Severity Score (NISS)

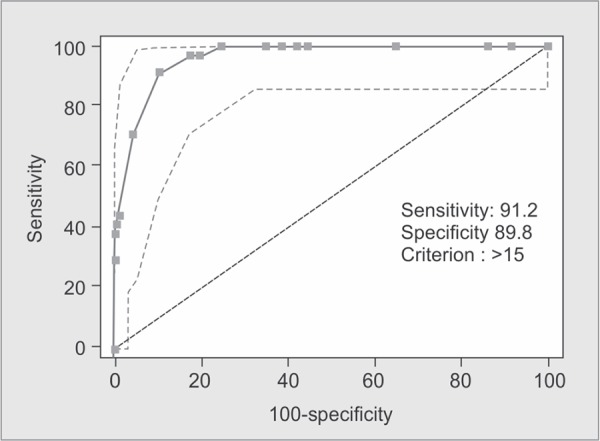

A simple modification to the ISS, the new injury severity score (NISS), was designed by Osler et al. in 1997 to counter this problem12. The NISS is simply the sum of squares of the three most severe injuries, regardless of body region injured. Therefore, the NISS will be equal to or higher than the ISS (Graph 2).

Graph 2.

ROC curve showing validity of NISS score in predicting outcome (i.e. mortality)

Revised Trauma Score (RTS)

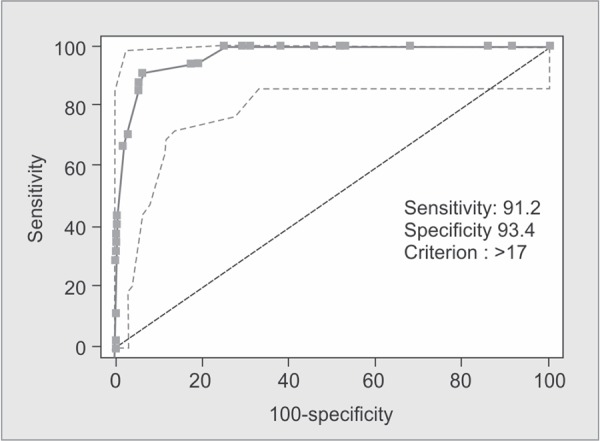

The revised trauma score is a physiological scoring system, with high interrater reliability and demonstrated accuracy in predicting death. It is scored from the first set of data obtained on the patient and consists of glasgow coma scale, systolic blood pressure and respiratory rate (Graph 3)13.

Graph 3.

ROC curve showing validity of RTS score in predicting outcome (i.e. mortality)

RTS = 0.9368 GCS + 0.7326 SBP + 0.2908 RR

RTS score coding is shown in Table 1. Values for the RTS are in the range 0-7.8408. The RTS is heavily weighted towards the Glasgow coma scale to compensate for major head injury without multisystem injury or major physiological changes. A threshold of RTS <4 has been proposed to identify those patients who should be treated in a trauma centre, although this value may be somewhat low.

Table 1.

RTS score coding

| Glasgow coma scale (GCS) | Systolic blood pressure (SBP) | Respiratory rate (RR) | Coded value |

|---|---|---|---|

| 13-15 | >89 | 10-29 | 4 |

| 9-12 | 76-89 | >29 | 3 |

| 6-8 | 50-75 | 6-9 | 2 |

| 4-5 | 1-49 | 1-5 | 1 |

| 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

Trauma and Injury Severity Scores (TRISS)

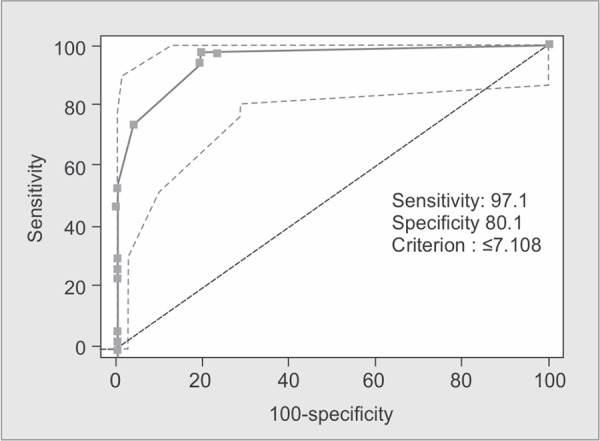

TRISS determines the probability of survival (Ps) of a patient from the ISS and RTS using the following formulae:

Ps= 1/ (1 + e-b)

Where ‘b’ is calculated from:

b = b0 + b1 (RTS) + b2 (ISS) + b3 (Age Index)

The coefficients b0 - b3 are derived from multiple regression analysis of the Major Trauma Outcome Study (MTOS) database. Age Index is 0 if the patient is below 54 years of age or 1 if 55 years and over. b0 - b3 are coefficients which are different for blunt and penetrating trauma. If the patient is less aged than 15 years, the blunt coefficients are used regardless of mechanism (Graph 4).

Graph 4.

ROC curve showing validity of TRISS score in predicting outcome (i.e. mortality)

| Blunt | Penetrating | |

|---|---|---|

| b0 | -0.4499 | -2.5355 |

| b1 | 0.8085 | 0.9934 |

| b2 | -0.0835 | -0.0651 |

| b3 | -1.7430 | -1.1360 |

The TRISS calculator determines the probability of survival from the ISS, RTS and patient's age. ISS and RTS scores can be given independently or calculated from their base parameters14.

TRISS uses combination of both anatomic and physiologic scoring systems and gives a more accurate probability of survival.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Our study was a prospective observational study carried out over a period of 18 months (December 2016 - June 2018) on elderly victims of trauma presenting to the Department of Emergency Medicine. Patients were selected after taking into account the inclusion and exclusion criteria (Flowchart 1).

Flowchart 1.

Methodology of our study-depicting research

Inclusion Criteria

Age more than 60 years.

History and clinical evidence of trauma.

Exclusion Criteria

Patients discharged against medical advice.

Patients/ Attendants of patients who were not willing to participate in the study.

DATA ANALYSIS

The sensitivity, specificity and correct prediction of outcome for each cutoff point were calculated for ISS, NISS, RTS and TRISS. The best cutoff point in each scoring system is determined when the point yields the best specificity and sensitivity in the two-by-two Table. The best Youden index also determines the best cutoff point. The Youden index was used to compare the proportion of cases correctly classified. The higher the Youden index, the more accurate is the prediction (higher true positive and true negatives and fewer false positive and false negatives) at the cutoff point15. Descriptive statistics were expressed as mean ± one standard deviation unless otherwise stated. A receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve depicts the relation between true-positive and false-positive for each scoring system. This method compares scores without fixing arbitrary cutoff points. The area under ROC curve was calculated and evaluated. AUROC represents that a randomly chosen diseased subject is more correctly rated or ranked than a randomly chosen non-diseased subject16.

A value of 0.5 under the ROC curve indicates that the variable performs no better than chance and a value of 1.0 indicates perfect discrimination. A larger area under the ROC curve represents more reliability and good discrimination of the scoring system17.

RESULTS

Two hundred trauma patients aged more than 60 years were included in our study with a mean age of 66.35 ± 6.865 years. Of the total, 74% were men (n= 148) and 26% were women (n=52). Most common mechanism of trauma was road traffic accident (94%), followed by fall (5.5%). All cases were blunt trauma. 166 patients (83%) recovered after treatment in hospital and 34 patients (17%) died (Table 2).

Table 2.

Epidemiological findings

| Variables | Cases | % | |

|---|---|---|---|

| age | 60-70 years | 160 | 80.0 |

| 71-80 years | 34 | 17.0 | |

| >80 years | 6 | 3.0 | |

| Sex | Female | 52 | 26.0 |

| Male | 148 | 74.0 | |

| Assault | 1 | 0.5 | |

| Mode of injury | Fall | 11 | 5.5 |

| RTA | 188 | 94.0 | |

| Nature of Injury | Blunt | 200 | 100.0 |

| Penetrating | 0 | 0 | |

| Outcome | Discharged | 166 | 83.0 |

| Mortality | 34 | 17.0 | |

| Head-neck | 102 | 51 | |

| Face | 81 | 40.5 | |

| Region of trauma | Thorax | 17 | 8.5 |

| Abdomen | 4 | 2 | |

| Extremity | 84 | 42 | |

| External | 110 | 55 |

Among those who were discharged, mean± SD of ISS, NISS, RTS and TRISS scores were 7.52±5.03, 8.80±6.19, 7.60±0.48 and 95.49±4.41 respectively. Among those who were expired, mean ± SD of ISS, NISS, RTS and TRISS scores were 20.85 ±5.00, 27.65 ±7.49, 5.43±1.29 and 58.48 ±25.58 respectively (Table 3).

Table 3.

Mean ISS, NISS, RTS, and TRISS of elderly survivors and non-survivors

| Non-survivors (n = 34) | Survivors (n = 166) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Scores | Mean ± SD | Mean ± SD | p value |

| ISS | 20.85 ± 5.00 | 7.52 ± 5.03 | <0.001* |

| NISS | 27.65 ± 7.49 | 8.80 ± 6.19 | <0.001* |

| RTS | 5.43 ± 1.29 | 7.60 ± 0.48 | <0.001* |

| TRISS | 58.48 ± 25.58 | 95.49 ± 4.41 | <0.001* |

In our study mean trauma scores of ISS and NISS were significantly higher in expired subjects than in Living subjects, RTS and TRISS were significantly lower in expired subjects than in Living subjects.

The predictive accuracies of the ISS, NISS, RTS and the TRISS were compared using receiver operator characteristic (ROC) curves for the prediction of mortality. Best cutoff points for predicting mortality in elderly trauma patients in ISS, NISS, RTS and TRISS systems were 15, 17, 7.108, 91.6 with sensitivity of 91%, 91%, 97%, 97% and specificity of 89%, 93%, 80%, 87%, respectively.

The area under ROC curve was 0.963, 0.970, 0.947, 0.972 in the ISS, NISS, RTS and TRISS respectively. The Youden index had best cut-off points at 0.80, 0.84, 0.77 and 0.85 for ISS, NISS, RTS and TRISS respectively (Table 4).

Table 4.

Comparison of the assessment scores in predicting outcome

| Scores | Cutoff | Sensitivity | Specificity | PPV | NPV | AUC | Youden index | p value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ISS | >15 | 91.18% | 89.76% | 64.6% | 98.0% | 0.963 | 0.8094 | <0.0001 |

| NISS | >17 | 91.18% | 93.37% | 73.8% | 98.1% | 0.970 | 0.8455 | <0.0001 |

| RTS | ≤7.108 | 97.06% | 80.12% | 50% | 99.3% | 0.947 | 0.7718 | <0.0001 |

| TRISS | ≤91.6 | 97.06% | 87.95% | 62.3% | 99.3% | 0.972 | 0.8501 | <0.0001 |

DISCUSSION

Most of elderly trauma patients in the present study were men. Some studies have shown similar results18,19. Mean age of our patients was 66.35 years with age range of 60 to 95 years. This is lesser than other studies20,21. The present study indicated that the most common mechanisms leading to trauma in the elderly were motor vehicle accidents, followed by falls. A study by Aydin et al. also revealed that most common mechanism leading to trauma was motor vehicle accident22. Most frequently injured organ was extremity followed by head and neck. Aydin et al. study also reported that the most common injury sites were head and extremities22. In this study, 17% of elderly trauma patients died. Yousefzadeh-Chabok etal. study reported mortality rate of 13.9%23.

In the present study, mean plus standard deviation of ISS for non-survivors was 20.85±5.00 and 7.52±5.03 for survivors; mean plus standard deviation of NISS for non-survivors was 27.65±7.49 and 8.80±6.19 for survivors, mean plus standard deviation of RTS for non-survivors was 5.43±1.29 and 7.60±0.48 for survivors. Mean plus standard deviation of TRISS for non-survivors was 58.48±25.58 and was 95.49± 4.41 for survivors.

In a study by Orhon et al., mean plus standard deviation of ISS for non-survivors was 24.37 ± 12.85 and 5.78 ± 6.71 for survivors;; mean plus standard deviation of NISS for former was 27.62 ± 12.85 and 6.92 ± 8.13, mean plus standard deviation of RTS for former was 5.62 ± 1.31, and 7.75 ± 0.46 for latter group. Mean plus standard deviation of TRISS for non-survivors was 72.80 ± 19.35 and was 98.34±6.58 for survivors24.

In a study by Yousefzadeh-Chabok et al., mean plus standard deviation of ISS for non-survivors was 15.95±10.46 and 7.31±6.22 for survivors; mean plus standard deviation of RTS for former was 5.65±1.82, and 7.79±0.27 for latter group. Mean plus standard deviation of TRISS for non-survivors was 1.04±1.49 and was 3.49±0.6 for survivors23.

Our results indicated that ISS and NISS value for survivors is significantly lower than for non-survivors. RTS and TRISS value for survivors were higher than non-survivors. This difference was statistically significant.

In the present study, area under ROC curve using ISS, NISS, RTS, and TRISS for predicting death was 0.963, 0.970, 0.947 and 0.972 respectively; all of these scores were statistically significant in terms of mortality prediction.

In Aydin et al. study, area under ROC curve using ISS, NISS and TRISS for predicting death was 0.907, 0.914 and 0.934, respectively22. In Yousefzadeh-Chabok et al. study, area under ROC curve using ISS, RTS and TRISS for predicting death was 0.76, 0.87 and 0.94, respectively23.

In a study conducted by Mitchell et al. in Canada published in 2007, it was reported that scoring systems including TRISS had a good ability to predict the prognosis of patients with trauma25. In a study conducted in India, Hariharan et al. concluded that using TRISS system to predict morbidity and mortality after fall in the elderly can play an important role in treatment planning26.

According to logistic regression model used in our study, NISS and TRISS were strong predictors of mortality in elderly trauma patients.

Drawbacks of Our Study

The sample size is relatively small.

This is a single centre study

CONCLUSION

Our study findings suggest that utility and applicability of injury severity scoring systems in elderly trauma patients using ISS, NISS, RTS, and TRISS scores can better help the emergency physicians in predicting the prognosis. However, TRISS has maximum prediction in outcome when compared with the other scores.

Footnotes

Source of support: Nil

Conflict of interest: None

REFERENCES

- 1.Krug EG, et al., editors. World report on violence and health. Geneva,: World Health Organization,; 2002.. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Center for Disease Control and Prevention. National Center for Health Statistics: All Injuries. Web Site: http://ftp.cdc.gov/pub/Health_Statistics/NCHS/NHIS/SHS/2014_SHS_Table_P-5.pdf. Accessed 04/05/16. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Champion HR,, Copes WS,, et al. Major trauma in geriatric patients. Am J Public Health. Am J Public Health. 1989;;79::1278-–1282.. doi: 10.2105/ajph.79.9.1278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Osler T,, Hales K,, et al. Trauma in the elderly. Am J Surg. 1988;;156::537-–543.. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9610(88)80548-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Perdue PW,, Watts DD,, et al. Differences in mortality between elderly and younger adult trauma patients: Geriatric status increases risk of delayed death. J Trauma. 1998;;45::805-–810.. doi: 10.1097/00005373-199810000-00034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gubler KD,, Davis R,, et al. Long-term survival of elderly trauma patients. Arch Surg. 1997;;132::1010-–4.. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.1997.01430330076013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Day RJ,, Vinen J,, et al. Major trauma outcomes in the elderly. Med J Aust. 1994;;160::675.. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Beuran M,, Negoi I,, et al. [Trauma scores: a review of the literature]. Chirurgia (Bucur). 2012 May-Jun;107((3):):291-297.. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Baker SP,, O'Neill B,, et al. The injury severity score: a method for describing patients with multiple injuries and evaluating emergency care. J Trauma. 1974;;14::187-–196.. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bolorunduro OB,, Villegas C,, et al. Validating the Injury Severity Score (ISS) in different populations: ISS predicts mortality better among Hispanics and females. J Surg Res. 2011 Mar; 166((1):):40-–44.. doi: 10.1016/j.jss.2010.04.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Stevenson M,, Segui-Gomez M,, et al. An overview of the injury severity score and the new injury severity score. Inj Prev. 2001;;7::10-–13.. doi: 10.1136/ip.7.1.10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Husum H,, Strada G. Injury Severity Score versus New Injury Severity Score for penetrating injuries. Prehospital Disaster Med. 2002;;17::27-–32.. doi: 10.1017/s1049023x0000008x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Champion HR, et al. “A Revision of the Trauma Score”, J Trauma. 1989;;29::623-–629.. doi: 10.1097/00005373-198905000-00017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Boyd CR,, Tolson MA,, et al. Evaluating trauma care: the TRISS method. Trauma Score and the Injury Severity Score. J Trauma. 1987;;27::370-–378.. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Youden WJ. Index for rating diagnostic test. Cancer. 1950;;3::32-–5.. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(1950)3:1<32::aid-cncr2820030106>3.0.co;2-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hanley JA,, McNeil BJ. The meaning and use of the area under a receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve. Radiology. 1982;;143::29-–36.. doi: 10.1148/radiology.143.1.7063747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Oh TE,, Hutchinson R,, et al. Verification of the acute physiology and chronic evaluation scoring system in a Hong Kong intensive care unit. Crit Care Med. 1993;;21::689-–705.. doi: 10.1097/00003246-199305000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cevik Y,, Doğan NÖ,, et al. Evaluation of geriatric patients with trauma scores after motor vehicle trauma. Am J Emerg Med. 2013;;31::1453-–1456.. doi: 10.1016/j.ajem.2013.07.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Akköse Aydin S,, Bulut M,, et al. Trauma in the elderly patients in Bursa. Ulus Travma Acil Cerrahi Derg. 2006;;12::230-–234.. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Richmond TS,, Kauder D,, et al. Characteristics and outcomes of serious traumatic injury in older adults. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2002;;50::215-–222.. doi: 10.1046/j.1532-5415.2002.50051.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kim JK,, Choe MS,, et al. Factors Influencing Mortality in Geriatric Trauma. J Korean Soc Emerg Med. 1999;;10::421-–430.. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Aydin SA,, Bulut M,, et al. Should the New Injury Severity Score replace the Injury Severity Score in the Trauma and Injury Severity Score? Ulus Travma Acil Cerrahi Derg. 2008;;14::308-–312.. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yousefzadeh-Chabok S,, Hosseinpour M,, et al. Comparison of revised trauma score, injury severity score and trauma and injury severity score for mortality prediction in elderly trauma patients. Ulus Travma Acil Cerrahi Derg. 2016 Nov;22((6):):536-540.. doi: 10.5505/tjtes.2016.93288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Orhon R,, Eren SH,, et al. Comparison of trauma scores for predicting mortality and morbidity on trauma patients. Ulus Travma Acil Cerrahi Derg. 2014 Jul;20((4):):258-264.. doi: 10.5505/tjtes.2014.22725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mitchell AD,, Tallon JM,, et al. Air versus ground transport of major trauma patients to a tertiary trauma centre: a province-wide comparison using TRISS analysis. Can J Surg. 2007;;50::129-–133.. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hariharan S,, Chen D,, et al. Evaluation of trauma care applying TRISS methodology in a Caribbean developing country. J Emerg Med. 2009;;37::85-–90.. doi: 10.1016/j.jemermed.2007.09.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]