Abstract

Non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma is reportedly common in Africa; however, there is limited data on renal involvement. Acute kidney injury only at presentation is rare for lymphoproliferative malignancies. A 7-year old presented to our facility with a 2-week history of progressive abdominal distension and pain, examination revealed anasarca and hypertension. On further evaluation, there were bilateral nephromegaly, acute kidney injury (AKI) and cytomorphological findings suggestive of lymphoma. Patient management was mostly supportive, and evolution was unfavourable leading to his demise. We discuss diagnostic and therapeutic challenges due to unavailability of state-of-the-art facilities in resource-constrained settings.

Keywords: Acute kidney injury, lymphoma, Cameroon

Introduction

Kidney involvement in non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma documented in the literature across the globe1–3 is often asymptomatic and rarely presents with renal failure.2,4,5 We present a case of aggressive non-Hodgkin lymphoma, with renal failure, nephromegaly and bone marrow involvement, normal white cell counts and no lymph node enlargement. We equally discuss diagnostic challenges in a resource poor setting in Cameroon.

Case presentation

A 7-year-old male presented with progressive abdominal pain and distension over 2 weeks, associated with vomiting. There was no diarrhoea, no constipation, no fever, night sweats nor weight loss. Previous interventions included antimalarials and antibiotics in a peripheral health centre 1 week prior to consultation. There was no family history of malignancy or chronic disease.

His height was 108 cm, weight 18 kg and blood pressure 120/80 mmHg (> 95thcentile for age and height).6 His pulse was 130 beats/minute, oxygen saturation 95%, axillary temperature 36.4°C and urine output was 80 mL/h. He had anarsaca, abdominal distention with mild generalized tenderness and ballotable flank masses. There was no hepatomegaly, splenomegaly, nor palpable lymph nodes.

Serum creatinine was 4.35 mg/dL and there was no proteinuria. Detailed laboratory tests results are summarized in Table 1. Ultrasonography revealed bilateral enlarged hyperechoic kidneys with smooth outlines (right kidney: 177 × 117 × 114 mm and left: 171 × 93 × 92 mm), mild pelvicaliectasis, with no discrete mass. Liver, biliary tree and spleen appeared normal, and no intraabdominal mass nor enlarged lymph node was seen.

Table 1.

Laboratory investigations.

| Values (in SI units) | Reference ranges (in SI units) | |

|---|---|---|

| Creatinine | 4.35 mg/dL (384.55 μmol/L) | 0.7–1.2 mg/dL (61.88–106.08 μmol/L) |

| Sodium | 139 meq/L (139 mmol/L) | 136–145 meq/L (136–145 mmol/L) |

| Potassium | 7.41 meq/L (7.41 mmol/L) | 3.5–5.1 meq/L (3.5–5.1 mmol/L) |

| Chloride | 94 meq/L (94 mmol/L) | 98–107 meq/L (98–107 mmol/L) |

| Calcium | 9.58 mg/dL (2.39 mmol/L) | 8.6–10.0 mg/dL (2.15–2.50 mmol/L) |

| Uric acid | 13.7 mg/dL (1.5 mmol/L) | 3.4–7.0 mg/dL (0.4–0.8 mmol/L) |

| Lactate dehydrogenase | 774U/L (12.9 µkat/L) | 135–225 U/L (2.25–3.75 µkat/L) |

| Glucose | 42.3 mg/dL (2.3 mmol/L) | 74–106 mg/dL (4.1–5.9 mmol/L) |

| Albumin | 3.80 g/dL (38 g/L) | 3.5–5.2 g/dL (35–52 g/L) |

| Aspartate aminotransferase | 19.1 U/L (0.32 µkat/L) | 0.1–40 U/L (0.0–0.67 µkat/L) |

| Alanine aminotransferase | 8.0 U/L (0.13 µkat/L) | 0.1–41 U/L (0.0–0.68 µkat/L) |

| Total bilirubin | 0.3 mg/dL (5.13 µmol/L) | 0.1–1.2 mg/dL (1.71–20.52 µmol/L) |

| Total leukocyte | 5.2 × 109/L | 4.0–10.0 × 109/L |

| Neutrophil count | 2.5 × 109/L | 1.5–7.5 × 109/L |

| Lymphocyte count | 2.0 × 109/L | 1.2–4.0 × 109/L |

| Platelets | 324 × 109/L | 100–35,0109/L |

| Haemoglobin | 7.8 g/dL (78 g/L) | 13.0–17.0 g/dL (130–170 g/L) |

| Urine dipstick/microscopy | 1–3 leukocytes | |

| 0 erythrocytes | ||

| +2 ketones | ||

| 0 casts | ||

| 0 protein | ||

| Urine sodium | 80 mmol/L | 40–220 mmol/L |

| Urine chloride | 60.4 mmol/L | 110–250 mmol/L |

| Urine potassium | 18.20 mmol/L | 25–125 mmol/L |

| Urine creatinine | 28.2 mg/dL (2492.93 µmol/L) | 1–500 mg/dL (88.40–44,200.85 µmol/L) |

| HIV serology | Negative | |

| Rapid diagnostic test for malaria | Negative |

Laboratory investigations and results with equivalent conversions in SI units.

A non-contrast computed tomography (CT) scan revealed bilateral nephromegaly (right: 17.5 cm longest diameter and left: 17.0 cm), mild bilateral pelvicaliectasis, but no discrete mass nor lymph nodes. The liver and spleen were normal (Figure 1). Intravenous contrast could not be employed due to existing renal failure and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) was unavailable.

Figure 1.

Bilateral homogeneous nephromegaly on CT scan.

Non-contrast computed tomography (CT) scan showing bilateral homogeneous nephromegaly with no identifiable mass.

In light of AKI with nephromegaly, and the absence of evident prerenal or obstructive causes, cytopathological investigations were undertaken. The peripheral blood smear demonstrated erythroblastosis, anisocytosis, rare tear drops, 13% eosinophilia, normochromic normocytic anaemia and atypical lymphoid cells (nucleolated lymphocytes, 13% of leukocytes). Platelets appeared adequate and there were no Burkitt cells or lymphoblast.

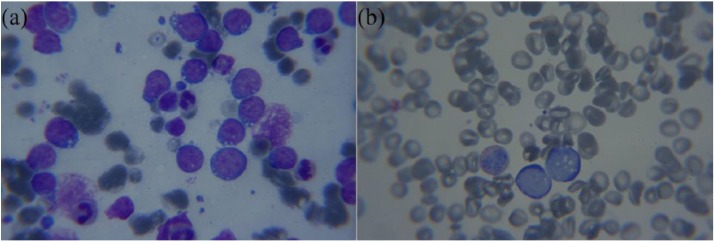

Percutaneous ultrasound guided fine needle aspirate cytopathology (FNAC) of the right kidney revealed lymphoglandular bodies, chromatin streaming and individual lymphoid cells with immature chromatin, nucleoli and scant dark blue vacuolated cytoplasm (Figure 2(a)). Bone marrow aspirate revealed 64.5% malignant lymphoid cells with blast-like chromatin, scant dark blue vacuolated cytoplasm. Cellularity could not be estimated due to lack of spicules. No megakaryocytes were seen. The myeloid-to-erythroid ratio was 1.7 (Figure 2(b)).

Figure 2.

Kidney and bone marrow slides. (a) Kidney aspirate with lymphoglandular bodies, lymphoid cells with nucleoli and scant dark blue vacuolated cytoplasm. (b) Bone marrow aspirate with 64.5% malignant lymphoid cells with blast-like chromatin, scant dark blue vacuolated cytoplasm.

Based on clinical presentation and available investigations, our differentials included Burkitt and lymphoblastic lymphoma/leukaemia. Biopsy and accompanying ancillary techniques such as immunocytochemistry, flow cytometry and cytogenetics were unavailable in our setting.

Management was largely supportive and comprised allopurinol to forestall tumour lysis, nifedipine for hypertension, frusemide for fluid overload, and insulin, glucose plus kayexalate for hyperkalaemia (haemodialysis being unavailable). Kidney function however worsened. Consciousness began to deteriorate on the 9th day of admission, and he died on the 11th day, pending establishment of a definitive diagnosis and initiation of chemotherapy.

Discussion

Renal involvement in non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma is usually clinically silent and discovered incidentally on routine imaging.5 When kidney impairment occurs (usually not at presentation), it results from one or a combination of several mechanisms, notably; parenchymal infiltration, uric acid nephropathy, glomerulopathy, obstruction, cytotoxic drugs, nephrotic syndrome, sepsis, amyloidosis and hypotension.7 Parenchymal infiltration usually takes the form of a mass and less commonly diffuse infiltration.8–10 When present, diffuse lymphomatous infiltration causes bilateral nephromegaly, distortion of normal architecture or tubular compression and though rare, can result in renal failure8 at presentation,7 probably explaining our patient’s presentation with mild pelvicaliectasis. However, conditions like transitional cell, collecting duct or medullary carcinoma and pyelonephritis can equally cause nephromegaly without a mass and require adequate imaging to exclude.5,8,9

Uric acid nephropathy constitutes a second hypothesis for AKI in our patient. It usually occurs secondary to tumour lysis during chemotherapy in high-grade tumours but reports of uric acid induced AKI in lymphoblastic leukaemia prior to chemotherapy exist.11 Uric acid, lactate dehydrogenase and potassium levels were elevated but calcium levels were normal. However, hyperphosphatemia and thus secondary hypercalcemia are considered less common in spontaneous tumour lysis.12 Management in our case was restricted to allopurinol and careful hydration because haemodialysis facilities and recombinant urate oxidase were unavailable.

Renal lymphomas are hypo vascular, and of lower density than parenchyma on imaging.8 On ultrasound, masses are hypoechoic and homogeneous,8 while diffuse infiltration is heterogenous without deformity of kidney shape.8 Ultrasound findings in our case alluded to hyperechoic kidneys without cortical distortion reflecting findings in another report.13 Our findings were equally consistent with expectations in a non-contrast CT of diffuse lymphomatous kidney infiltration, described in the literature as, ‘fairly homogeneous with slightly higher attenuation than surrounding parenchyma’.8

Contrast-enhanced CT scan is the gold standard for the diagnosis of renal lymphoma.8 It permits depiction of subtle lesions, visualizing renal vessels, differentiating poorly enhancing hypo vascular lymphomas from hyper vascular tumours (like renal cell carcinomas), as well as identifying perirenal and retroperitoneal masses.8 Intravenous contrast was contraindicated in our case due to AKI. MRI, a recognized alternative in this subset of patients, was equally impossible due to limited finances and unavailability of the tool in our facility.

Kidney FNAC in our patient demonstrated lymphoglandular bodies and a monomorphic population of atypical lymphoid cells suggesting a lymphoma.5,14 This was substantiated with bone marrow cytology. Cytomorphology suggested lymphoblastic or Burkitt’s lymphoma/leukaemia, both of which are known to have overlapping features.14 Lymphoblastic leukaemia appeared likely considering the extent of bone marrow involvement (65%). Determination of the histologic subtype is important for management and prognosis. Accurate characterization however, which could have been achieved by immunohistochemical analysis of trephine biopsies or by other ancillary techniques, was not possible in our setting.

Primary renal lymphoma (arising in kidneys) is a rare entity. Some authors propose five diagnostic criteria: AKI at presentation; renal enlargement without obstruction or other organ/node involvement; absence of other causes of AKI; diagnosis with biopsy and improvement of renal function with chemotherapy.2,15 Another definition however is a lymphoma manifesting with signs and symptoms of renal disease;14 hence, our patient may have had the rather elusive primary renal lymphoma. Alternatively, our patient could have had the equally uncommon multifocal extra-nodal lymphoma (bone marrow and kidneys), with one of three distinct entities described by some authors:16 (1) the primary nodal in lymph nodes, Waldeyer’s ring, spleen or thymus, with no/minor extra-nodal involvement (usually bone marrow); (2) primary extra-nodal at other sites, with no or only regional lymph node involvement and (3) extensive disease; combined nodal and extra-nodal localization.

In any case, renal function and size are expected to rapidly improve with initiation of chemotherapy.14 However, as was substantiated in our patient, kidney impairment complicates treatment, is associated with poorer prognosis and shortened survival in children with renal lymphoma.17

Conclusion

Renal lymphoma has been sparsely described in African literature. AKI secondary to diffuse renal infiltration of aggressive multifocal extra-nodal disease is a rare presentation. With proper diagnostic facilities, patients can benefit from early lifesaving chemotherapy. However, outcome is poor in the absence of appropriate and timely intervention especially in low-income settings, as described here. While the absence of renal biopsy and accompanied advanced diagnostic techniques prevent us from establishing a definitive diagnosis in our case, to the best of our knowledge, this is the first report of AKI secondary to renal lymphoma in Cameroon. We present it to highlight diagnostic challenges in our setting and to raise the index of suspicion of our primary care physicians.

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to the patient’s family for providing consent. The authors acknowledge the contributions of Dr Richard L. Bardin, MD, FACP, FCAP (Internal Medicine and Pathology), at Mbingo Baptist Hospital who interpreted the patient’s slides and proof read the manuscript.

Footnotes

Consent to participate: Informed consent was obtained for the use of the patient’s information from the legally authorized representative, in this case the parent.

Declaration of conflicting interests: The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship and/or publication of this article.

Ethics approval: Ethical approval to report this case was obtained from Cameroon Baptist Convention Health Board Institutional Review Board (CBC Health Board IRB: 03/09/18).

Funding: The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship and/or publication of this article.

Informed consent: Written informed consent was obtained from a legally authorized representative(s) for anonymized patient information to be published in this article.

ORCID iD: Jeannine Anyingu Aminde  https://orcid.org/0000-0003-3149-6494

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-3149-6494

References

- 1. Li S-J, Chen H-P, Chen Y-H, et al. Renal involvement in non-Hodgkin lymphoma: proven by renal biopsy. PLos ONE 2014; 9(4): e95190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Da’as N, Polliack A, Cohen Y, et al. Kidney involvement and renal manifestations in non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma and lymphocytic leukemia: a retrospective study in 700 patients. Eur J Haematol 2002; 67: 158–164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Yunus SA, Usmani SZ, Ahmad S, et al. Renal involvement in non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma: the Shaukat Khanum experience. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev 2007; 8(2): 249–252. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Fajardo L, Ramin GDA, Penachim TJ, et al. Abdominal manifestations of extranodal lymphoma: pictorial essay. Radiol Bras 2016; 49(6): 397–402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Subhawong AP, Subhawong TK, Vanden Bussche CJ, et al. Lymphoproliferative disorders of the kidney on fine-needle aspiration: cytomorphology and radiographic correlates in 33 cases. Acta Cytol 2013; 57(1): 19–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Flynn JT, Kaelber DC, Baker-Smith CM, et al. Clinical practice guideline for screening and management of high blood pressure in children and adolescents. Pediatrics. Epub ahead of print 1 September 2017. DOI: 10.1542/peds.2017-1904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Boldukyz DT, Ludmila BS, Hunan J, et al. Kidney damage in the manifestation of lymphoproliferative diseases. Blood 2016; 128: 5313. [Google Scholar]

- 8. Sheth S, Ali S, Fishman E. Imaging of renal lymphoma: patterns of disease with pathologic correlation. RadioGraphics 2006; 26(4): 1151–1168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Lee W-K, Lau EWF, Duddalwar VA, et al. Abdominal manifestations of extranodal lymphoma: spectrum of imaging findings. Am J Roentgenol 2008; 191(1): 198–206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Manzella A, Borba-Filho P, D’Ippolito G, et al. Abdominal manifestations of lymphoma: spectrum of imaging features. ISRN Radiol 2013; 2013: 483069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Bhatia NG, Sneha LM, Selvan SM, et al. Acute renal failure as an initial manifestation of acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Indian J Nephrol 2013; 23(4): 292–293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Wilson FP, Berns JS. Onco-nephrology: tumor lysis syndrome. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 2012; 7(10): 1730–1739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Monfared A, Orangpoor RO, Fakheri TF, et al. Acute renal failure and bilateral kidney infiltration as the first presentation of non-Hodgkin lymphoma. Iran J Kidney Dis 2009; 3(1): 50–53. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Truong LD, Caraway N, Ngo T, et al. Renal lymphoma. The diagnostic and therapeutic roles of fine-needle aspiration. Am J Clin Pathol 2001; 115(1): 18–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Malbrain ML, Lambrecht GL, Daelemans R, et al. Acute renal failure due to bilateral lymphomatous infiltrates. Primary extranodal non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma (p-EN-NHL) of the kidneys: does it really exist? Clin Nephrol 1994; 42(3): 163–169. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Economopoulos T, Papageorgiou S, Rontogianni D, et al. Multifocal extranodal non-Hodgkin lymphoma: a clinicopathologic study of 37 cases in Greece, a Hellenic Cooperative Oncology Group study. Oncologist 2005; 10(9): 734–738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Büyükpamukçu M, Varan A, Aydın B, et al. Renal involvement of non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma and its prognostic effect in childhood. Nephron Clin Pract 2005; 100(3): c86–c91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]