Abstract

We present a case of Syringocystadenocarcinoma papilliferum that originated in the eyelid and extended into the orbit. These tumors are very rare and have the potential to metastasize. A literature review of all the previous cases has been compiled from the Medline, EMBASE, and PubMed databases. We found that the majority of cases present on the head and neck and up to 17% of cases showed metastatic progression. This is the first case to show orbital involvement and highlights the need to remain vigilant with such lesions, as they have a tendency to become aggressive.

Keywords: eyelid, orbit, Syringocystadenocarcinoma papilliferum

Introduction

Syringocystadenocarcinoma papilliferum (SCACP) is a rare malignant sudoriferous gland tumor that is related to its more common, benign counterpart, syringocystadenoma papilliferum (SCAP). Since the original description of SCAP in 1917,1 only 43 cases of SCACP have been described in the literature. To date, only one has appeared in the eyelid.2 SCACP is thought to develop from SCAP, nevus sebaceous, and linear nevus verrucosus lesions.3 However, due to the rarity of this tumor, little is known regarding its etiology and origin.3

In this study, we report the first case of SCACP with orbital involvement. Interestingly, it recurred following exenteration. An informed written consent was obtained from the patient for the publication of medical data and images.

Case report

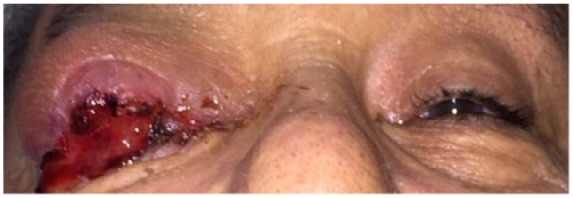

A 63-year-old man presented with a lesion on the right upper eyelid that had been present for 7 years. The lesion was nodular, measuring 5.0 cm × 7.0 cm, ulcerated, indurated, and erythematous. It involved the lower eyelid (Figure 1). The patient had no light perception with the right eye and had a visual acuity of 20/20 on the left. Due to the presence of the tumor over the right eye, his intraocular pressure could not be measured, and it was found to be 18 mmHg on the left.

Figure 1.

Lesion on presentation.

The left orbital examination did not reveal any abnormalities. A full examination of his local lymph nodes and lacrimal duct did not reveal any abnormalities. He explained that he did not have any previous therapy for this lesion. He was otherwise systemically well with no relevant family history. He did not have any history of trauma and informed us that he was a farmer by occupation.

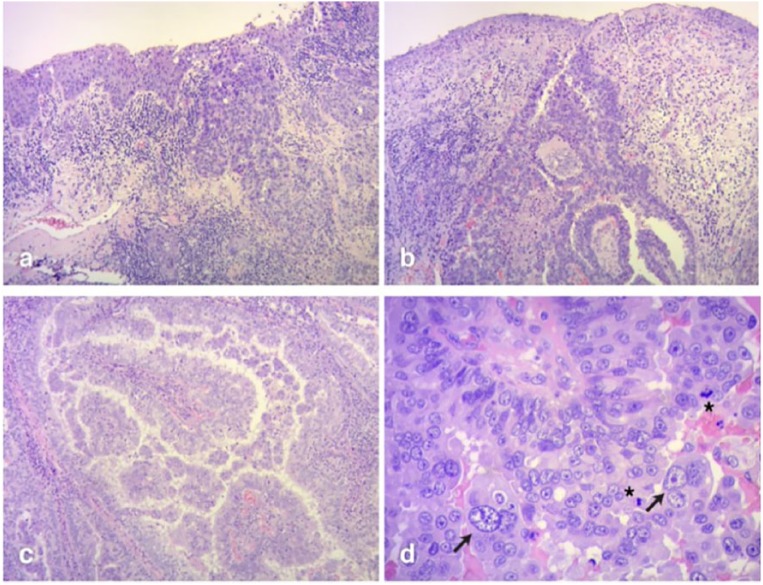

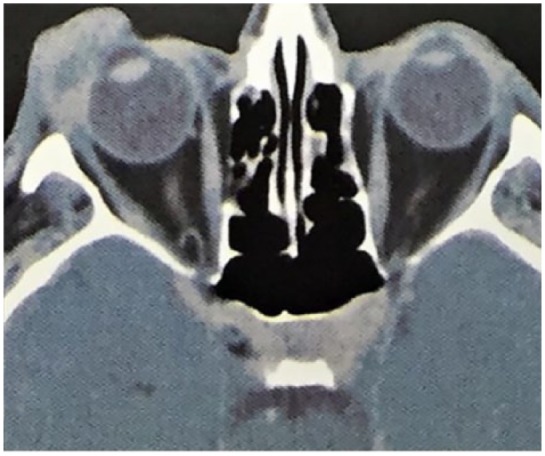

A computed tomography (CT) scan of the orbit revealed right anterior orbital invasion with no bony or lacrimal gland involvement (Figure 2). A subsequent incisional biopsy revealed squamous cell invaginations extending from the epidermis into the dermis. The invaginations and papillary projections were lined with a bilayer epithelium: the luminal layer was composed of columnar cells with decapitation secretion and the outer layer was composed of small cuboidal cells. These cells had significant nuclear pleomorphism, prominent nucleoli, and increased mitotic activity (Figure 3). Immunohistochemical staining demonstrated positivity for epithelial membrane antigen (EMA), Cytokeratin 8/18, and a Cytokeratin cocktail of high and low density (Figure 3). It was negative for GCDFP-15 (protein 15 of the fibrocystic disease of the breast), which excluded a lesion of breast origin and carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA). The diagnosis of SCACP was therefore confirmed. A positron emission tomography (PET) scan did not reveal any metastatic spread.

Figure 2.

CT imaging of the lesion at presentation.

Figure 3.

Hematoxylin and eosin staining (H&E): (a) the transition between squamous and glandular epithelium (100×). (b) Large areas of superficial epithelium were sphacelated. Glandular invaginations showed a characteristic funnel shape. Papillary structures can be identified inside a dermal cyst (100×). (c) The papillary structures are lined with a stratified atypical epithelium. Micropapillae and secretion by decapitation can be seen (100×). (d) At high power magnification, atypical nuclei are evident. Large atypical nuclear shapes are seen and increased mitotic activity is observed (*).

The patient was treated with exenteration of the right orbit to remove the tumor. After 11 months of follow-up, we noted local recurrence of the original tumor (confirmed with biopsy) in the anophthalmic orbit. There was no associated lymph node enlargement on examination, though the patient refused any further imaging. Radical exenteration with adjuvant radiotherapy has been planned for the patient.

Discussion

SCACP is an extremely rare adnexal neoplasm of the sweat glands and has only been documented 43 times in the literature. It is believed to arise from a malignant transformation of SCAP lesions.4 Clinically, it may present as an asymptomatic long-standing lesion, which may be flat or nodular, cystic, or ulcerated. We performed a literature review of the Medline, EMBASE, and Cochrane databases to characterize the cases previously listed in the literature (Table 1).

Table 1.

Previous case reports on SCACP.

| Reference | Age | Sex | Location | Size (mm) | Duration | Diagnosis | Association | Follow-up | Treatment |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dissanayake and Salm5 | 74 | F | Scalp | 65 | 30 years | SCACP in situ | SCAP | NED (6.75 years) | Surgery |

| 71 | F | Back | 30 | N/A | SCACP invasive | N/A | NED (7 years) | Surgery | |

| Seco Navedo and colleagues6 | 50 | F | Scalp | 65 | Congenital | SCACP invasive | Nevus sebaceous | 3 Local lymph node, lymph node metastasis | Surgery + Rt + Ct (NED—2 years) |

| Numata and colleagues7 | 52 | F | Chest | 130 × 80 | 20 years | SCACP invasive | N/A | 1 Local lymph node, lymph node metastasis | Surgery NED (12 months) |

| Bondi and Urso8 | 47 | M | Scalp | 25 | N/A | SCACP invasive | N/A | N/A | Surgery |

| Ishida-Yamamoto and colleagues9 | 61 | M | Perianal | 60 | 10 years | SCACP in situ | N/A | NED (11 months) | Surgery |

| Arai and colleagues10 | 64 | M | Scalp | 35 | 2 years | SCACP in situ | SCAP | N/A | Surgery |

| Chi and colleagues11 | 60 | M | Auricle | 40 × 10 | Since childhood | SCACP invasive | SCAP | NED (72 months) | Surgery |

| Woestenborghs and colleagues12 | 81 | F | Scalp | 15 | N/A | SCACP in situ | SCAP | N/A | Surgery |

| Park and colleagues13 | 65 | M | Suprapubic region | 35 | 2 years | SCACP in situ | N/A | NED (24 months) | Surgery |

| Langner and Ott14 | 83 | M | Perianal | 15 | N/A | SCACP in situ | SCAP | N/A | Surgery |

| Sroa and colleagues15 | 77 | M | Calf | 25 | 9 years | SCACP invasive | N/A | NED (15 months) | Surgery |

| Kazakov and colleagues16 | 56 | F | Neck | 20 | 10 years | SCACP in situ | SCAP | NED (9 months) | Surgery |

| 58 | M | Forehead | 25 | 25 years | SCACP invasive | SCAP | NED (4 years) | Surgery | |

| 46 | F | Scalp | 35 | N/A | SCACP invasive | SCAP | NED (6 years) | Surgery | |

| 67 | M | Scalp | 25 | N/A | SCACP in situ | SCAP | NED (2 years) | Surgery | |

| 60 | F | Scalp | 30 | >30 years | SCACP invasive | SCAP | N/A | Surgery | |

| 81 | M | Scalp | 20 | N/A | SCACP invasive | SCAP | NED (21 months) | Surgery | |

| Leeborg and colleagues17 | 86 | F | Neck | 45 | 4 months | SCACP invasive | Invasive squamous cell carcinoma | Local recurrence (18 months) | Surgery + Rt |

| Abrari and Mukherjee18 | 62 | M | Axilla | 35 | 6 months | SCACP invasive | N/A | N/A | Surgery |

| Aydin and colleagues19 | 67 | M | Scalp | 40 | Since childhood | SCACP invasive | SCAP | NED (2 years) | Surgery |

| Hoekzema and colleagues3 | 83 | F | Arm | 30 | 7 years | SCACP invasive | SCAP nevus verrucosus | N/A | Surgery |

| Hoguet and colleagues20 | 86 | M | Eyelid | 4 | N/A | SCACP invasive | N/A | NED (3 months) | Surgery |

| Plant and colleagues21 | 83 | M | Penis | 12 | N/A | SCACP in situ | N/A | N/A | Surgery |

| Bakhshi and colleagues22 | 45 | F | Scalp | 60 × 30 | 12 months | N/A | SCAP | NED (12 months) | Surgery in situ |

| Zhang and colleagues23 | 75 | F | Arm | 15 | 12 months | SCACP invasive | SCAP | NED (6 months) | Surgery |

| Peterson and colleagues24 | 65 | M | Scalp | 30x30 | 12 months | SCACP invasive | SCAP | NED | Surgery |

| Arslan and colleagues2 | 66 | M | Scalp | N/A | 20 years | SCACP invasive | SCAP | 3 Local lymph node, lymph node metastasis | Surgery + Rt (NED—15 months) |

| 66 | F | Scalp | 30 | >12 months | SCACP invasive | N/A | NED (2 years) | Surgery | |

| Castillo and colleagues25 | 32 | F | Scalp | 22 | N/A | SCACP in situ | N/A | Local recurrence (8 years) | Surgery |

| Paradiso and colleagues26 | 88 | M | Shoulder | 15 × 15 | N/A | SCACP invasive | N/A | Died from other cause | N/A |

| Shan and colleagues27 | 93 | M | Popliteal fossa | 20 | >10 years | N/A | SCAP | NED | Surgery |

| Mohanty and colleagues28 | 80 | F | Scalp | 50 | 8 years | SCACP in situ | N/A | NED (5 years) | Surgery |

| Satter and colleagues29 | 42 | M | Scalp | 45 × 40 | >1 month | SCACP invasive | SCAP and Nevus sebaceous | Lymph node metastasis | Surgery |

| Parekh and colleagues4 | 74 | M | Scalp | 20 | Since childhood | SCACP invasive | SCAP, nevus sebaceous of Jadassohn, trichoblastoma | Lymph node metastasis | Surgery |

| Chen and colleagues30 | 60 | F | Scalp | 28 × 20 | 12 months | SCACP in situ | Nevus sebaceous | N/A | Surgery |

| Singh and colleagues31 | 60 | F | Back | 15 × 10 | >10 years | SCACP in situ | SCACP in situ with macular amyloidosis | N/A | Surgery |

| Zhang and colleagues32 | 26 | M | Chest | 50 | 22 years | SCACP in situ | Invasive adenocarcinoma subcutis | Left axillary lymph node and bilateral lung metastases, DOD 2 months after diagnosis | Surgery + Ct |

| 47 | M | Abdomen | 15 | 23 years | SCACP in situ | N/A | NED (9 years) | Surgery | |

| 67 | M | Left Axilla | 20 | 6 years | SCACP in situ | Invasive adenocarcinoma subcutis | N/A | Surgery + left axilla lymphadenectomy | |

| 64 | M | Scalp | 20 | 1 years | SCACP in situ | Invasive adenocarcinoma in dermis + mucinous metaplasia | Metastases to multiple distant lymph nodes and lung metastases, DOD 34 months after diagnosis | Surgery + Rt | |

| 63 | M | Chest | 10 | 10 years | SCACP in situ | Invasive adenocarcinoma in dermis | NED (36 months) | Surgery | |

| 74 | M | Chest | 20 | 6 years | SCACP in situ | Invasive adenocarcinoma subcutis | NED (30 months) | Surgery | |

| 63 | F | Axilla | 50 | 3 months | SCACP in situ | Invasive adenocarcinoma + invasive squamous cell carcinoma | Widespread subcutaneous metastases, DOD 20 months after diagnosis | Surgery + right axilla lymphadenectomy | |

| 40 | M | Chest | 50 | 5 years | SCACP in situ | Invasive adenocarcinoma subcutis | NED (14 months) | Surgery + bilateral lymphadenectomy + Ct | |

| 29 | F | Forehead | 15 | 2 years | SCACP in situ | Invasive squamous cell carcinoma | NED (10 months) | Surgery | |

| 64 | M | Axilla | 22 | 10 years | SCACP in situ | Invasive adenocarcinoma subcutis | NED (3 months) | Surgery + right axilla lymphadenectomy + Ct | |

| Present case | 63 | M | Eyelid | 50 × 70 | >6 years | SCACP invasive | SCAP | Local recurrence | Surgery |

Ct, chemotherapy; Rt, radiation therapy; N/A, not available; NED, no evidence of disease; DOD, died of disease.

The tumor appears to affect middle-aged or elderly individuals15 and does not seem to have a gender bias. The most frequent location is the head and neck (53%), with only one case in the eyelid. Other locations where these lesions occur frequently are the back, chest, suprapubic, and perianal regions.

Treatment is based on a complete tumor resection with oncological margins, which is essential for a better prognosis. Mohs surgery has also been successfully used for this purpose.11 Sentinel lymph node biopsy may be feasible in some cases when there is suspicion of lymph spread, although lymphatic spread has been shown to be rare with this tumor (6 of the 42 documented cases; Table 1). Radiotherapy and chemotherapy have also been used rarely, but the experience with these treatments is scarce due to the rarity of the lesion.25

SCACP characteristically presents with squamous cell invaginations extending from the epidermis into the dermis. The invaginations and papillary projections are lined by two-layer epithelium: the luminal layer composed of columnar cells with decapitation secretions and the outer layer composed of small cuboidal cells. The immunohistochemical features of SCACP are still under study, but the most frequently reported markers are CEA,15,20,28 followed by EMA,9,28 GDFP-15,20,28,32 and cytokeratin.11,28,32

Due to its appearance, the differential diagnosis includes other skin tumors such as basal cell carcinoma, squamous cell carcinoma, sebaceous carcinoma, metastatic breast or gastrointestinal adenocarcinomas, and other sweat gland neoplasms.2,20

Of the cases that reported head and neck involvement, 16 (72.72%) were in remission following therapy, 2 (9.09%) had local recurrence, 3 (13.63%) had regional lymphatic invasion, and 1 (4.54%) had distant metastases. Of the reports describing involvement of the thorax, abdomen, and pelvis, 17 (85%) went into remission following therapy, none had local recurrence, 1 (5%) had regional lymphatic invasion and 2 (10%) had distant metastases.

This is the first reported case of SCACP with extension into the anterior orbit. While SCACP is an exceedingly rare tumor, we found that of the reported cases, 16% showed signs of metastasis. It is therefore an important diagnosis to consider when reviewing skin lesions around the orbit. It also encourages us to monitor patients with SCAP more closely as our literature review suggests that SCACP may be more aggressive than previously considered.

Footnotes

Funding: The authors received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Conflict of interest statement: The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

ORCID iD: Shoaib Ugradar  https://orcid.org/0000-0003-4479-3033

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-4479-3033

Contributor Information

Carla Pagano Boza, Oculoplastics Department, Hospital Italiano de Buenos Aires, Buenos Aires, Argentina.

Joaquin Gonzalez-Barlatay, Oculoplastics Department, Hospital Italiano de Buenos Aires, Buenos Aires, Argentina.

Shoaib Ugradar, Division of Orbital and Ophthalmic Plastic Surgery, Stein Eye Institute, University of California, Los Angeles, Los Angeles, CA, USA.

Melina Pol, Pathology Department, Hospital Italiano de Buenos Aires, Buenos Aires, Argentina.

Eduardo Jorge Premoli, Oculoplastics Department, Hospital Italiano de Buenos Aires, Buenos Aires, Argentina.

References

- 1. Stokes J. A clinico-pathologic study of an unusual cutaneous neoplasm combining nevus syringadenomatosus papilliferus and a granuloma. J Cutan Dis 1917; 35: 411–419, https://books.google.com/books?id=9PFYAAAAYAAJ&pg=PA671&lpg=PA671&dq=A+clinico-pathologic+study+of+an+unusual+cutaneous+neoplasm+combining+nevus+syringadenomatosus+papilliferus+and+a+granuloma.+J+Cutan+Dis&source=bl&ots=MH440aj-Em&sig=WAwobjiLCvgBPsX4Zxqp (accessed 24 January 2018). [Google Scholar]

- 2. Arslan H, Diyarbakrl M, Batur Demirkesen ŞC. Syringocystadenocarcinoma papilliferum with squamous cell carcinoma differentiation and with locoregional metastasis. J Craniofac Surg 2013; 24: e38–e40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Hoekzema R, Leenarts MFE, Nijhuis EWP. Syringocystadenocarcinoma papilliferum in a linear nevus verrucosus. J Cutan Pathol 2011; 38: 246–250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Parekh V, Guerrero CE, Knapp CF, et al. A histological snapshot of hypothetical multistep progression from nevus sebaceus to invasive syringocystadenocarcinoma papilliferum. Am J Dermatopathol 2016; 38: 56–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Dissanayake RV, Salm R. Sweat-gland carcinomas: prognosis related to histological type. Histopathology 1980; 4: 445–466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Seco Navedo MA, Fresno Forcelledo M, Orduna Domingo A, et al. [Syringocystadenoma papilliferum with malignant evolution. Presentation of a case]. Ann Dermatol Venereol 1982; 109: 685–689, http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/7187194 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Numata M, Hosoe S, Itoh N, et al. Syringadenocarcinoma papilliferum. J Cutan Pathol 1985; 12: 3–7, http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/2982933 (accessed 17 October 2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Bondi R, Urso C. Syringocystadenocarcinoma papilliferum. Histopathology 1996; 28: 475–477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Ishida-Yamamoto A, Sato K, Wada T, et al. Syringocystadenocarcinoma papilliferum: case report and immunohistochemical comparison with its benign counterpart. J Am Acad Dermatol 2001; 45: 755–759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Arai Y, Kusakabe H, Kiyokane K. A case of syringocystadenocarcinoma papilliferum in situ occurring partially in syringocystadenoma papilliferum. J Dermatol 2003; 30: 146–150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Chi CC, Tsai RY, Wang SH. Syringocystadenocarcinoma papilliferum: successfully treated with Mohs micrographic surgery. Dermatol Surg 2004; 30: 468–471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Woestenborghs H, VanEyken P, Dans A. Syringocystadenocarcinoma papilliferum in situ with pagetoid spread: a case report. Histopathology 2006; 48: 869–870. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Park SH, Shin YM, Shin DH, et al. Syringocystadenocarcinoma papilliferum: a case report. J Korean Med Sci 2007; 22: 762–765. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Langner C, Ott A. Syringocystadenocarcinoma papilliferum in situ originating from the perianal skin. APMIS 2009; 117: 148–150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Sroa N, Sroa N, Zirwas M. Syringocystadenocarcinoma Papilliferum. Dermatologic Surg 2010; 36: 261–263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Kazakov DV, Requena L, Kutzner H, et al. Morphologic diversity of syringocystadenocarcinoma papilliferum based on a clinicopathologic study of 6 cases and review of the literature. Am J Dermatopathol 2010; 32: 340–347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Leeborg N, Thompson M, Rossmiller S, et al. Diagnostic pitfalls in syringocystadenocarcinoma papilliferum: case report and review of the literature. Arch Pathol Lab Med 2010; 134: 1205–1209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Abrari A, Mukherjee U. Syringocystadenocarcinoma papilliferum at unusual site: inherent lesional histologic polymorphism is the pathognomon. BMJ Case Rep 2011; 2011: bcr0520114254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Aydin OE, Sahin B, Ozkan HS, et al. A rare tumor: syringocystadenocarcinoma papilliferum. Dermatologic Surg 2011; 37: 271–274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Hoguet AS, Dolphin K, McCormick SA, et al. Syringocystadenocarcinoma papilliferum of the eyelid. Ophthalmic Plast Reconstr Surg 2012; 28: e27–e19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Plant MA, Sade S, Hong C, et al. Syringocystadenocarcinoma papilliferum in situ of the penis. Eur J Dermatol; 22: 405–406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Bakhshi GD, Wankhede KR, Tayade MB, et al. Carcino-sarcoma in a case of syringocystadenoma papilliferum: a rare entity. Clin Pract 2012; 2: e71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Zhang YH, Wang W-L, Rapini RP, et al. Syringocystadenocarcinoma papilliferum with transition to areas of squamous differentiation. Am J Dermatopathol 2012; 34: 428–433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Peterson J, Tefft K, Blackmon J, et al. Syringocystadenocarcinoma papilliferum: a rare tumor with a favorable prognosis. Dermatol Online J 2013; 19: 19620. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Castillo L, Moreno A, Tardío JC. Syringocystadenocarcinoma papilliferum in situ. Am J Dermatopathol 2014; 36: 348–352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Paradiso B, Bianchini E, Cifelli P, et al. A new case of syringocystadenocarcinoma papilliferum: a rare pathology for a wide-ranging comprehension. Case Rep Med 2014; 2014: 453874. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Shan S-J, Chen S, Heller P, et al. Syringocystadenocarcinoma papilliferum with intraepidermal pagetoid spread on an unusual location. Am J Dermatopathol 2014; 36: 1007–1010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Mohanty SK, Pradhan D, Diwaker P, et al. Long-standing exophytic mass in the right infratemporal region. Int J Dermatol 2014; 53: 539–542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Satter E, Grady D, Schlocker CT. Syringocystadenocarcinoma papilliferum with locoregional metastases. Dermatol Online J 2014; 20: 22335. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Chen J, Beg M, Chen S. Syringocystadenocarcinoma papilliferum in situ, a variant of cutaneous adenocarcinoma in situ. Am J Dermatopathol 2016; 38: 762–765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Singh S, Khullar G, Sharma T, et al. An unusual case of syringocystadenocarcinoma papilliferum in situ with macular amyloidosis. JAMA Dermatol 2017; 153: 725–727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Zhang Y, Kong Y-Y, Cai X, et al. Syringocystadenocarcinoma papilliferum: clinicopathologic analysis of 10 cases. J Cutan Pathol 2017; 44: 538–543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]