Abstract

Background:

Mood disorders are major risk factors for suicidal behavior. While cross-sectional studies implicate frontal systems, data to aid prediction of suicide-related behavior in mood disorders are limited. Longitudinal research on neuroanatomical mechanisms underlying suicide risk may assist in developing targeted interventions. Therefore, we conducted a preliminary study investigating baseline gray and white matter structure and longitudinal structural changes associated with future suicide attempts.

Methods:

High-resolution structural magnetic resonance imaging, diffusion tensor imaging, and suicide-related behavioral assessment data for 46 adolescents and young adults with mood disorders [baseline agemean=18 years; 61% female] were collected at baseline and at follow-up (intervalmean=3 years). Differences in baseline and longitudinal changes in gray matter volume and white matter fractional anisotropy in frontal systems that distinguished the participants who made future attempts from those who did not were investigated.

Results:

Seventeen (37%) of participants attempted suicide within the follow-up period. Future attempters (those attempting suicide between their baseline and follow-up assessment), compared to those who did not, showed lower baseline ventral and rostral prefrontal gray matter volume and dorsomedial frontal, anterior limb of the internal capsule, and dorsal cingulum fractional anisotropy, as well as greater decreases over time in ventral and dorsal frontal fractional anisotropy (p<0.005, uncorrected).

Limitations:

Sample size was modest.

Conclusions:

Results suggest abnormalities of gray and white matter in frontal systems and differences in developmental changes of frontal white matter may increase risk of suicide-related behavior in adolescents/young adults with mood disorders. Findings provide potential new leads for early intervention and prevention strategies.

INTRODUCTION

Suicide is a leading cause of death in adolescents/young adults (Zametkin et al., 2001). Mood disorders, especially those with early onset, are a major risk factor and increase suicide risk 20-fold (Chehil and Kutcher, 2011; Zisook et al., 2007). While estimates vary (Isometsa, 2014), as many as 50% of individuals with bipolar disorder (BD) and 15% with major depressive disorder (MDD) attempt suicide during their lifetime (Abreu et al., 2009; Chen and Dilsaver, 1996). With such high prevalence, research on predictors and development of suicide-related behavior in mood disorders is essential. Few data exist on neural mechanisms underlying development of suicide-related behavior. This is especially true for longitudinal data on neuroanatomical predictors in adolescence and early adulthood, when suicide-related behavior often emerges (Nock et al., 2013). Such data would be key to elucidating targetable neurodevelopmental processes which could assist in development of more effective prevention strategies.

Converging evidence from cross-sectional neuroimaging studies in mood disorders of suicide-related behavior, specifically investigations of suicide attempters, implicate frontal gray and white matter (WM) (Cox Lippard et al., 2014; Sudol and Mann, 2017). In studies of adults, many structural magnetic resonance imaging (sMRI) investigations (Benedetti et al., 2011; Ding et al., 2015; Giakoumatos et al., 2013; Monkul et al., 2007; Wagner et al., 2011; Wagner et al., 2012), but not all (Lee et al., 2016), show associations between past suicide attempts with lower ventral prefrontal cortex (vPFC) and dorsal PFC (dPFC) gray matter volume (GMV), including orbitofrontal (OFC), rostral PFC (rPFC), dorsolateral PFC (dlPFC), and anterior cingulate cortex (ACC), in adults with BD or MDD. Lower GMV in the caudate has been reported in suicide attempters with BD or MDD (Benedetti et al., 2011; Wagner et al., 2011). Additionally, history of a past suicide attempt was associated with lower insula GMV in BD (Giakoumatos et al., 2013).

Frontal WM abnormalities in attempters have also been reported. Past suicide attempts have been associated with lower vPFC fractional anisotropy (FA) in BD (Mahon et al., 2012) and MDD (Jia et al., 2014). In BD, past attempts have also been associated with lower corpus callosum (CC) volume and FA (Cyprien et al., 2016; Matsuo et al., 2010)—although negative findings in the CC also exist (Nery-Fernandes et al., 2012). In MDD, past attempts have been associated with decreased FA in dPFC and corticostriatal WM tract connections, including the anterior limb of the internal capsule (ALIC) (Jia et al., 2010; Olvet et al., 2014), and decreased connectivity strength within OFC and ACC WM connections (Bijttebier et al., 2015). Together, studies suggest frontal gray and WM abnormalities, including paralimbic and striatal connection sites, may be associated with attempts. Associations between Barratt Impulsiveness Scale (BIS) scores and WM abnormalities in the OFC and anterior CC suggest that anterior WM abnormalities may be associated with the suicide risk factor of impulsivity (Mahon et al., 2012; Matsuo et al., 2010).

While few, cross-sectional studies on neural circuitry in adolescents with mood disorders (Cox Lippard et al., 2014; Martin et al., 2015; Pan and Phillips, 2014) support a role for frontal gray and WM abnormalities in the development of suicide-related behavior. A past attempt during adolescence has been found to coincide with lower vPFC GMV and FA, including decreased FA in the uncinate fasciculus (UF), the main WM fiber tract connecting the vPFC to the anterior temporal lobe, in BD (Johnston et al., 2017) and lower ACC GMV in MDD (Goodman et al., 2011). Additionally, hypoconnectivity in ventral and dorsal frontal systems during adolescence has been found to coincide with greater lifetime severity of suicide ideation (Ordaz et al., 2018).

It is possible suicide attempts contribute to the brain abnormalities reported. To determine risk, longitudinal study is needed. However, longitudinal neurobiological studies of adolescents who go on to make future attempts or die by suicide are rare. Few studies have investigated predictors of prospective suicide attempts and none have been structural. A single-photon emission computed tomography imaging study showed an association between lower frontal, insular, and caudate regional cerebral blood flow and death by suicide in adults with a mood disorder (Willeumier et al., 2011). A recent positron emission tomography study also suggests that alterations in serotonergic mechanisms may be involved as it demonstrated a relationship between frontal and insula serotonin1A receptor binding with lethality of future attempts (Oquendo et al., 2016).

This study aimed to assess differences in brain gray and white matter structure (baseline predictors and longitudinal changes in GMV and FA measures), from high-resolution sMRI and diffusion tensor imaging (DTI) scans respectively, among adolescents/young adults with BD or MDD who reported a suicide attempt between their baseline scan and follow-up assessment, on average 3 years later, compared to those who did not. For primary hypothesis testing, participants were assigned to the “Future-SA” group if they made a suicide attempt between their baseline and follow-up assessment and to the “NonFuture-SA” group if they did not. For this preliminary study, we included individuals with BD and MDD in a transdiagnostic approach to suicide-related behaviors as we aimed to identify potential predictors that may generalize to mood disorders and therefore might have broad impact. We hypothesized lower GMV and FA at baseline and progressive decreases in GMV and FA in anterior-paralimbic (vPFC, insula) and dorsofrontal (rPFC, dlPFC, ACC, striatum) systems would distinguish the Future-SA group from the NonFuture-SA group. We also hypothesized that lower baseline, and progressive decreases in, GMV and FA would be observed in future suicide attempters regardless of baseline suicide attempt history. We therefore explored for potential effects of a prior suicide attempt at baseline.

METHODS

Participants

Participants included 46 adolescents/young adults with a mood disorder (34 with BD, 12 with MDD [mean age at baseline ± standard deviation (SD)= 18.2±2.9 years; time between baseline and follow-up=3.1±1.1 years; 61% female]) assessed for suicide attempts at baseline and follow-up assessments using the Columbia Suicide History Form, with attempt defined as a self-injurious act with at least some intent to die (Oquendo et al., 2003a). At baseline, current and lifetime psychiatric diagnoses, clinical characteristics, and current mood state were confirmed based on the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Diagnosis [SCID; (First, 1995)] for participants aged ≥18 years and the Kiddie-Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia [K-SADS; (Kaufman et al., 1997)] for participants <18 years. Twenty-three participants (50%) were euthymic at the time of scan, 11 (24%) were depressed, and 12 (26%) were in an elevated (i.e. manic, hypomanic, or mixed) mood state. Eleven (24%) participants had at least one past suicide attempt at baseline; two of these participants had two prior attempts.

Exclusion criteria included history of major medical illness with possible central nervous system effects or neurological illness, including head trauma with loss of consciousness for ≥5min. Individuals were not excluded for hypothyroidism if treated. On neuroimaging day, urine screens for substances of abuse were negative for all subjects (cannabis, cocaine, amphetamine, methamphetamine, methadone, opiates, phencyclidine, barbiturates, and benzodiazepines). Besides four participants with a current alcohol or other substance use disorder (A/SUD), no subject had history of a A/SUD within five months prior to baseline. After complete description of the study, written informed consent was obtained from subjects ≥18 years, and assent and parent/guardian permission from subjects <18, in accordance with the Yale School of Medicine human investigation committee.

At baseline, 4 participants (3 NonFuture-SA, 1 Future-SA) did not have DTI scanning. Table 1 details clinical characteristics stratified by group. At follow-up, 43 participants (28 NonFuture-SA; 15 Future-SA) and 36 participants (23 NonFuture-SA; 13 Future-SA) underwent repeat sMRI and DTI scans respectively.

Table 1:

Demographic and clinical factors stratified by suicide group.

|

NonFuture-SA

(N=29) |

Future-SA

(N=17) |

p

value |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Demographics/ Clinical Factors | Age at Baseline Scan (SD) | 18.1 (2.7) | 18.2 (3.4) | 0.918 |

| Number of Females (%) | 16 (55) | 12 (71) | 0.301 | |

| Interval Between Scan and Follow-up (SD) | 2.9 (0.9) | 3.5 (1.4) | 0.146 | |

| Years of Education (SD) | 11.4 (2.2) | 11.2 (2.3) | 0.791 | |

| Suicide Attempt Prior to Baseline Assessment (%) | 3 (10) | 8 (47) | 0.010F | |

| Number with MDD Diagnosis at Baseline (%) | 9 (31) | 3 (18) | 0.489F | |

| Mood State [Euthymic(%) / Depressed(%) / Elevated(%)]1 | 14 (48) / 7 (24)/ 8 (28) | 9 (52) / 4 (24) / 4 (24) | 0.944F | |

| Rapid Cycling (%)2 | 10 (50) | 7 (50) | 0.650 | |

| Lifetime Psychosis (%) | 8 (28) | 7 (41) | 0.345 | |

| Current Tobacco Use at Baseline (%) | 9 (31) | 6 (35) | 0.766 | |

| Total Barratt Impulsiveness Scale (BIS)-11 Score (SD)3 | 67.9 (12.3) | 67.2 (10.7) | 0.860 | |

| BIS Nonplanning Impulsiveness (SD)3 | 26.5 (6.4) | 26.3 (5.2) | 0.909 | |

| BIS Motor Impulsiveness (SD)3 | 23.0 (5.3) | 22.3 (3.8) | 0.675 | |

| BIS Cognitive-Attentional Impulsiveness (SD)3 | 18.4 (4.3) | 18.6 (3.8) | 0.882 | |

| Comorbidities | Anxiety Disorders4 | 1 (3) | 4 (24) | 0.055F |

| History of Alcohol/Substance Use Disorders (A/SUDs) (%) | 7 (24) | 5 (29) | 0.738F | |

| Current A/SUDs (%) | 1 (3) | 3 (18) | 0.135 | |

| Medications | Unmedicated at scan (%) | 6 (21) | 4 (24) | 1.000F |

| Antipsychotic (%) | 14 (48) | 8 (47) | 0.936 | |

| Anticonvulsant (%) | 12 (41) | 4 (24) | 0.338F | |

| Antidepressant (%) | 7 (24) | 8 (47) | 0.192 | |

| Stimulant (%) | 6 (21) | 4 (24) | 1.000F | |

| Lithium (%) | 3 (10) | 4 (24) | 0.397F | |

| Benzodiazepine (%) | 2 (7) | 3 (18) | 0.343F | |

| Zolpidem (%) | 1 (3) | 1 (6) | 1.000F | |

| Ketamine (%) | 0 (0) | 1 (6) | 0.354F | |

| Levothyroxine (%)5 | 1 (3) | 2 (12) | 0.545 | |

Age at baseline scan, interval between scan and follow-up, years of education, and BIS impulsivity scores were examined by a t test to investigate potential group differences (NonFuture-SA vs. Future-SA). All other factors were examined with chi-square or Fisher exact tests.

represents p value calculated with Fisher exact test.

Elevated mood includes participants in hypomanic, mixed, and manic mood states.

Rapid Cycling reported is history of rapid cycling in BD participants. Percentage shown is percentage of BD participants with rapid cycling.

One participant in NonFuture-SA group did not complete BIS assessment.

Anxiety disorders included generalized anxiety disorder, panic disorder, social phobia, and specific phobia.

Participants on levothryroxine had hypothyroidism.

With the exception of one NonFuture-SA participant, BIS-11 scores were available for all subjects (Gilbert et al., 2011; Patton et al., 1995). The total BIS score is the sum of three subscale scores: non-planning, cognitive-attentional, and motor impulsivity. At follow-up, Future-SA were evaluated for medical lethality, suicide ideation severity, and suicide intent of most recent suicide attempt with the Beck Medical Lethality Scale, Beck Scale for Suicide Ideation, and Suicide Intent Scale (Beck et al., 1975; Beck et al., 1979).

MRI and DTI Acquisition and Processing

High-resolution sMRI and DTI data were acquired with a 3-Tesla Siemens Trio MR scanner (Siemens, Erlangen, Germany). The sMRI sagittal images were acquired with a three-dimensional magnetization prepared rapid acquisition gradient echo (MPRAGE) T1-weighted sequence with parameters: repetition time (TR)=1500ms, echo time (TE)=2.83ms, matrix=256×256, field of view (FOV)=256×256mm2, and 160 one-mm slices without gap and two averages. MPRAGE images were processed using Statistical Parametic Mapping-12 (SPM12) as previously described (Lippard et al., 2017). DTI data were acquired in alignment with the anterior commissure–posterior commissure plane with diffusion sensitizing gradients applied along 32 non-collinear directions with b-value=1000s/mm2, together with an acquisition without diffusion weighting (b-value=0) (TR=7400ms; TE=115ms; matrix=128×128; FOV=256×256mm2 and 40 three-mm slices without gap). DTI images were processed with SPM8 as previously described (Lippard et al., 2016). The scanner, acquisition parameters and processing were the same for baseline and follow-up sMRI and DTI scans.

Statistical Analyses

Demographic and Clinical Feature Analysis

Two-sample t-tests were performed to assess potential group differences (Future-SA vs. NonFuture-SA) in baseline age, interval between baseline scan and follow-up suicide assessment, years of education, and impulsivity. Chi-square (or Fisher’s exact) tests were performed to explore potential group differences (Future-SA vs. NonFuture-SA) as appropriate. These included number of females, suicide attempt prior to baseline assessment, diagnosis at baseline (BD, MDD), mood state (euthymic, depressed, elevated), history (yes/no) of rapid cycling in individuals with BD, lifetime psychosis, current tobacco use, comorbid diagnosis (yes/no) of A/SUD, anxiety disorders (including generalized anxiety disorder, panic disorder, social phobia, and specific phobia), post-traumatic stress disorder, anorexia nervosa, bulimia nervosa, eating disorder NOS, and medication subclasses (on/off). Childhood comorbidities were not investigated since they were not assessed across all participants. Results were considered significant at p<0.05 (see Table 1).

Neuroimaging Analyses

Baseline Neuroimaging Data Analyses

For primary hypothesis testing, a two-sample t-test in SPM12 assessed group differences (Future-SA vs. NonFuture-SA) in baseline GMV and WM FA. While not significant, the Future-SA group had a longer interval between baseline and follow-up assessment compared to the NonFuture-SA group. Therefore, time between baseline and follow-up assessment was included as a covariate. For this preliminary study, sMRI and DTI results in GMV in hypothesized regions (vPFC, rPFC, dlPFC, ACC, insula, striatum) and FA in WM tracts connecting these regions, including UF, CC, anterior cingulum, and ALIC, were considered significant at p<0.005 (uncorrected) and clusters ≥20 voxels. This threshold was chosen to balance type I and type II errors in preliminary studies as previously described (Forman et al., 1995; Lieberman and Cunningham, 2009; Lippard et al., 2017). For brain regions and WM tracts outside of hypothesized regions, significance threshold was p<0.05 Family-Wise Error (FWE)-corrected and an extent threshold of 10 voxels to account for multiple comparisons. Mean GMV and FA, calculated from clusters showing significant differences between attempter groups (Future-SA vs. NonFuture-SA), were extracted and used in post hoc and exploratory analyses.

A post hoc analysis was performed to explore potential effects of prior attempts by further subdividing the Future-SA group into individuals who transitioned to their first attempt following their baseline assessment (i.e. did not have an attempt prior to baseline; Future-SAno-pastSA) and individuals who had an attempt prior to their baseline (Future-SA+pastSA). Specifically, a one-way ANOVA was performed examining main effect of group (NonFuture-SA, Future-SAno-pastSA, Future-SA+pastSA), with GMV or FA from extracted clusters as the dependent variable and time between baseline and follow-up assessments as a covariate. Following a significant main effect of group (p<0.05), t-tests were performed to determine which groups were significantly different from each other. Additionally, the between group t-test (Future-SA vs. NonFuture-SA) was repeated in SPM12 after excluding four individuals with a current A/SUD. All significant findings are reported below.

Analyses for Longitudinal Changes in Neuroimaging Data

To investigate longitudinal changes in GMV and WM FA associated with a future suicide attempt, a flexible factorial model in SPM12 was used to investigate group (Future-SA, NonFuture-SA) by time (baseline, follow-up) interactions, covarying interval, with time as a repeated variable. Results in hypothesized regions and WM tracts were considered significant at p<0.005 (uncorrected) and clusters ≥20 voxels. For brain regions and WM tracts outside of hypothesized regions, findings were considered significant with p<0.05 Family-Wise Error (FWE)-corrected and an extent threshold of 10 voxels. Mean GMV and FA, calculated from clusters showing significant group by time interactions, were extracted for post hoc analyses.

Repeated t-tests, stratified by group (NonFuture-SA, Future-SA), were performed with GMV or FA from extracted clusters as dependent variables. We were underpowered to investigate group by time interactions when stratifying the Future-SA group into subgroups. To explore for potential effects of prior attempts we therefore calculated individual change in GMV and FA for each cluster (follow-up assessment minus baseline assessment) and performed a one-way ANOVA examining main effect of group (NonFuture-SA, Future-SAno-pastSA, Future-SA+pastSA) with changes in GMV or FA from extracted clusters as dependent variables. Following a significant main effect of group, between group t-tests were performed to determine which groups differed. All significant findings are reported.

Associations between GMV and FA and Suicide-Related Behavior

Correlational relationships between GMV and FA abnormalities with suicide-related behaviors assessed at follow-up, including lethality, suicide intent, and suicide ideation of most recent attempt, were investigated using Spearman (rs). These correlation analyses were performed in the Future-SA group only. Correlational relationships between GMV and FA abnormalities and impulsivity scores were assessed with Pearson (r), stratified by attempter group. Correlations were considered significant at p<0.05, uncorrected.

RESULTS

Demographic and Clinical Feature Analyses

Seventeen (37%) of participants attempted suicide within the follow-up period. Fourteen BD (41%) and three MDD (25%) participants made a future attempt. Future-SA participants were more likely to have a prior suicide attempt compared to NonFuture-SA participants (47% vs. 10%, respectively, p=0.01, Fisher’s exact test). Future-SA participants were more likely to have a history of an anxiety disorder (24% vs. 3%, respectively, p=0.055, Fisher’s exact test). See Table 1 for demographic and clinical factors stratified by suicide group.

Neuroimaging Analyses

Baseline Neuroimaging Data Analyses: GMV

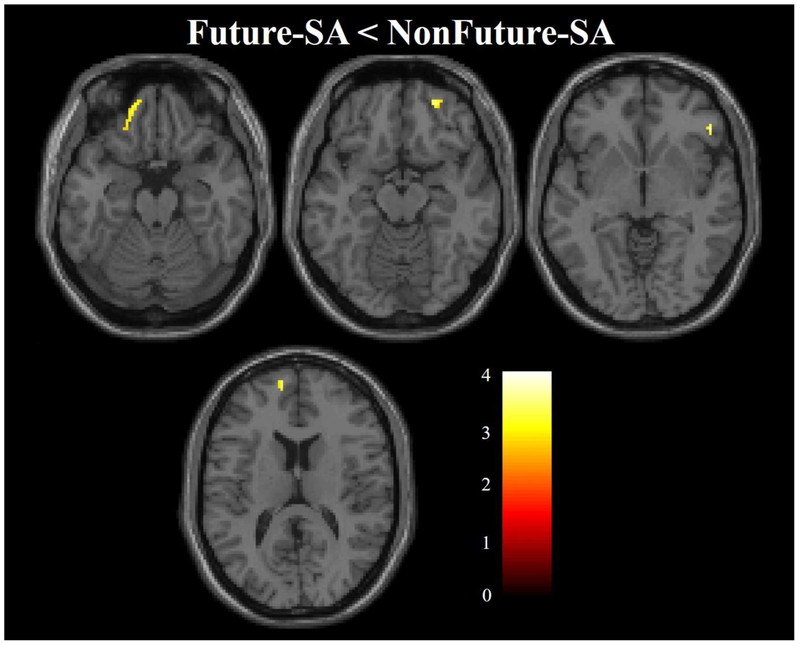

Within hypothesized regions, the Future-SA group, compared to NonFuture-SA group, showed lower GMV in three clusters in the vPFC (left Brodmann area [BA] 11, Montreal Neurological Institute (MNI) space coordinates: x=−14mm, y=48mm, z=−21mm, cluster=107 voxels; right ventral BA10, x=26mm, y=52mm, z=−14mm, cluster=52 voxels; right BA47, x=50mm, y=33mm, z=−3mm, cluster=51 voxels), and one cluster in the left dorsal rPFC (BA10, x=−10mm, y=58mm, z=14mm, cluster=97 voxels) (Figure 1). The Future-SA group, compared to the NonFuture-SA group, did not show any areas of greater GMV in hypothesized regions or any differences in GMV outside hypothesized regions.

Figure 1. Areas of lower gray matter volume in adolescents/young adults with mood disorders that made future suicide attempts compared to those who did not.

The axial-oblique images show the regions of lower gray matter volume in the future suicide group (Future-SA, N=17) compared with the group that did not make a future suicide attempt (NonFuture-SA, N=29). No regions of larger gray matter volume were observed in the Future-SA group compared with the NonFuture-SA group. Significance threshold is p<0.005; cluster>20 voxels. Left of figure denotes left side of brain. The color bar represents the range of T values.

When comparing NonFuture-SA, Future-SAno-pastSA, and Future-SA+pastSA groups for differences in extracted mean GMV from clusters reported above, a main effect of group was observed across all clusters (p<0.05). Both Future-SAno-pastSA and Future-SA+pastSA had lower GMV, compared to NonFuture-SA, across all clusters (p<0.05). There were no significant differences between Futur-SAno-pastSA and Future-SA+pastSA groups.

Regional differences in GMV identified in primary analysis remained significant at p<0.005 (uncorrected), clusters ≥20 voxels when excluding four individuals with current A/SUDs (not shown).

Baseline Neuroimaging Data Analyses: FA

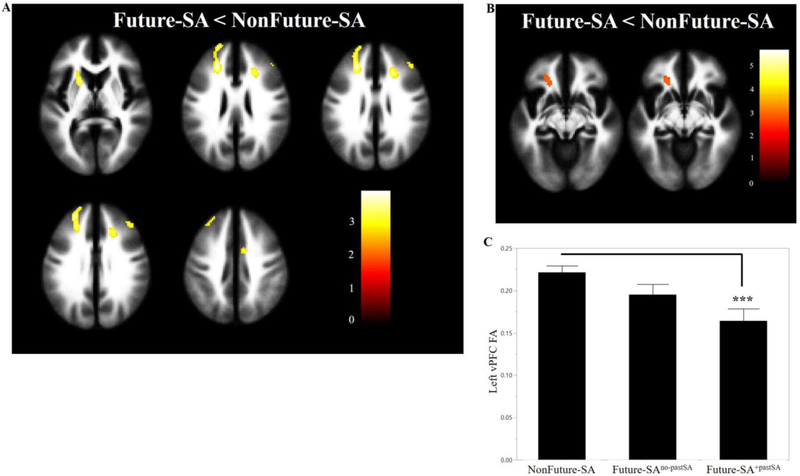

Within our hypothesized regions, the Future-SA group, compared to the NonFuture-SA group, had lower FA in clusters in left and right dorsomedial PFC (dmPFC, x=−20mm, y=58mm, z=20mm, cluster=463 voxels; x=22mm, y=26mm, z=28mm, cluster=92 voxels), right dlPFC (x=42mm, y=36mm, z=30mm, cluster=42 voxels), right dorsal cingulum (x=8mm, y=0mm, z=44mm, cluster=54 voxels), and left ALIC (x=−20mm, y=12mm, z=6mm, cluster=109 voxels) (Figure 2A). The Future-SA group, compared to the NonFuture-SA group, did not show areas of greater FA in hypothesized regions or any differences in FA outside of hypothesized regions.

Figure 2. Areas of lower fractional anisotropy (FA) in adolescents/young adults with mood disorders that made future suicide attempts compared to those who did not.

(A) The axial-oblique images show the regions of lower FA in the future suicide group (Future-SA, N=16)compared with the group that did not make a future suicide attempt (NonFuture-SA, N=26). No regions of larger FA were observed in the Future-SA group compared with the NonFuture-SA group. (B) The axial-oblique images show regions of lower FA in ventral prefrontal white matter in the future suicide group (Future-SA, N=13) compared with the group that did not make a future suicide attempt (NonFuture-SA, N=25) after removing four individuals who had current A/SUDs. (C) The bar graph shows FA at baseline between the NonFuture-SA group (N=25) and Future-SA subgroups [Future-SA subdivided into individuals who made a future attempt and did not have a prior attempt (Future-SAno-pastSA, N=6) and those that did have a prior attempt (Future-SA+pastSA, N=7)]. ***=p<0.005; For (A) and (B) significance threshold is p<0.005; cluster>20 voxels. Left of figure denotes left side of brain. The color bar represents the range of T values.

When comparing NonFuture-SA, Future-SAno-pastSA, and Future-SA+pastSA groups for differences in extracted mean FA from clusters reported above, a main effect of group was observed for all clusters (p<0.05). Both Future-SAno-pastSA and Future-SA+pastSA groups had lower FA, compared to the NonFuture-SA group, for left dmPFC, right dlPFC, and left ALIC clusters (p<0.05). While the Future-SA+pastSA group also showed lower FA in the right dmPFC and right dorsal cingulum clusters (p<0.05), the Future-SAno-pastSA group showed trends for lower FA in the right dmPFC (p=0.11) and right dorsal cingulum (p=0.06) clusters. There were no significant differences between Future-SAno-pastSA and Future-SA+pastSA groups.

Regional differences in FA identified in the primary analysis remained significant at p<0.005 (uncorrected), clusters ≥20 voxels when excluding four individuals with current A/SUDs (not shown). Additionally, after removing these four individuals, the Future-SA group had lower FA in one additional cluster in the left vPFC (x=−20mm, y=30mm, z=−8mm, cluster=71 voxels) (Figure 2B). When comparing NonFuture-SA, Future-SAno-pastSA, and Future-SA+pastSA groups for differences in extracted FA from vPFC cluster, a main effect of group was observed (p<0.01). T-tests (Figure 2C) showed Future-SA+pastSA group had lower FA, compared to the NonFuture-SA group, in the vPFC cluster (p=0.003). Future-SAno-pastSA group was not significantly different from the NonFuture-SA (p=0.12) or Future-SA+pastSA groups (p=0.11).

Analyses for Longitudinal Changes in Neuroimaging Data: GMV

There were no significant group by time interactions when assessing GMV.

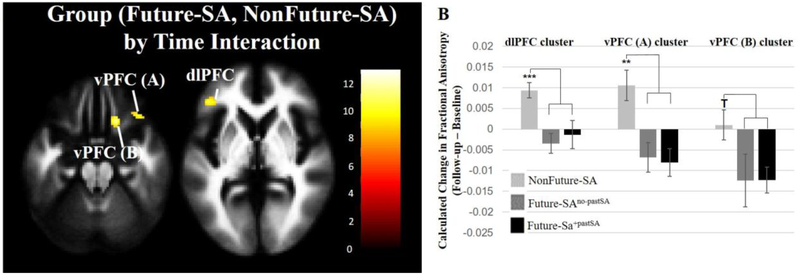

Analyses for Longitudinal Changes in Neuroimaging Data: FA

Within hypothesized regions, significant group by time interactions in FA were observed in two clusters in the right vPFC (x=18mm, y=24mm, z=−24mm, cluster=103 voxels; x=36mm, y=28mm, z=−22mm, cluster=33 voxels) and one cluster in the left dlPFC (x=−44mm, y=36mm, z=4mm, cluster=55 voxels) (Figure 3A). The Future-SA group showed significant decreases in FA over time in all three clusters (p<0.01). The NonFuture-SA group showed significant increases in FA in the dlPFC cluster (p<0.0001) and in the vPFC cluster with maximum at z=−24mm (p=0.01) but no significant change in FA in the other vPFC cluster.

Figure 3. Areas showing differences in FA changes between baseline and follow-up in adolescents/young adults with mood disorders that made future suicide attempts compared to those who did not.

(A) The axial-oblique images show regions where differences in FA changes were observed between the future suicide group (Future-SA, N=13) compared with the group who did not make a future suicide attempt (NonFuture-SA, N=23). The Future-SA group showed progressive decreases in FA of clusters but the NonFuture-SA group did not. Significance threshold is p<0.005; cluster>20 voxels. Left of figure denotes left side of brain. The color bar represents the range of T values. (B) The bar graph shows differences in calculated change in FA (follow-up minus baseline) between the NonFuture-SA group (N=23) and Future-SA subgroups [Future-SA subdivided into individuals who made a future attempt and did not have a prior attempt (Future-SAno-pastSA, N=6) and those that did have a prior attempt (Future-SA+pastSA, N=7]. ***=p<0.005, **=p<0.01; T=p≤0.07.

When comparing NonFuture-SA, Future-SAno-pastSA, and Future-SA+pastSA groups in calculated FA change overtime, a main effect of group was observed for dlPFC FA (p<0.002) and one of the vPFC clusters (p<0.008; cluster with maximum at z=−24). Both Future-SAno-pastSA and Future-SA+pastSA groups had significantly different patterns in changes in FA overtime in clusters identified above, compared to the NonFuture-SA group, but were not significantly different from one another. Specifically, both Future-SAno-pastSA and Future-SA+pastSA groups showed decreases in FA overtime while the NonFuture-SA group showed increases overtime in both clusters. A trend for main effect of group was observed in the other vPFC cluster (p=0.07) with t-tests revealing a similar pattern with both Future-SAno-pastSA (p=0.07) and Future-SA+pastSA (p=0.06) groups showing decreases in FA overtime while the NonFuture-SA group did not show a significant change in FA (Figure 3B).

Associations between GMV and FA and Suicide-Related Behavior

Among Future-SAs, FA in the right dlPFC at baseline and right vPFC at follow-up was negatively correlated with attempt lethality (rs=−0.55, p=0.03, n=16 and rs=−0.56, p=0.04, n=13 respectively). Lower FA at baseline in the right dmPFC and dlPFC was associated with higher cognitive-attentional impulsiveness subscores (r=−0.53, p=0.03, n=16; r=−0.54, p=0.03, n=16 respectively) in Future-SA, but not NonFuture-SA, individuals.

DISCUSSION

To our knowledge, this is the first longitudinal study to examine differences in baseline and changes that occur over time in GMV and WM FA between adolescents/young adults with mood disorders (BD or MDD) who prospectively make a suicide attempt, compared to those who do not, within three years following their baseline assessment. Consistent with hypotheses, participants who subsequently made an attempt showed lower baseline GMV in the medial and lateral vPFC and dorsal rPFC and lower baseline FA in the dlPFC, dmPFC, dorsal cingulum, and ALIC. Findings suggest these reductions in GMV and FA may be associated with risk for future attempt as the reductions were detected in both the Future-SA subgroups who did and who did not make an attempt prior to their baseline scan. FA differences in the vPFC and dlPFC appear to be progressive, as making a future attempt was associated with progressive decreases in FA in the vPFC and dlPFC between scans.

Regions of GMV abnormalities observed in the Future-SA group, including the vPFC and dorsal rPFC, extend previous cross-sectional reported findings in individuals with prior attempts and suggest abnormalities in behaviors subserved by regions of GMV differences may increase risk/vulnerability for future attempts. Medial and lateral vPFC regions implicated are suggested to alter affective processing and regulation, self-awareness, behavioral control, and risky decision-making (Clark et al., 2008; Craig, 2002; Etkin et al., 2011; Kringelbach and Rolls, 2004). Rostral and dorsal PFC are also implicated in affective processing, behavioral control, and decision making (Dumontheil et al., 2008; Etkin et al., 2011; Koechlin and Hyafil, 2007; Kovach et al., 2012) as well as higher-order executive functions, including attentional processes and mentalization (Burgess et al., 2007; Gilbert et al., 2006; Gusnard et al., 2001).

FA abnormalities observed in the Future-SA group, including differences in baseline and longitudinal changes of FA within dorsal frontal systems and the vPFC, and associations with lethality of attempts, are consistent with previous studies. Altered structure, including decreased FA, in dorsal frontal systems and the ALIC has previously been reported in MDD adults with at least one prior attempt (Jia et al., 2010; Olvet et al., 2014; Wagner et al., 2012). Lower vPFC FA has been reported in adolescents with BD and at least one prior attempt (Johnston et al., 2017). Reduced glucose metabolism in frontal systems has been associated with highly lethal attempts (Amen et al., 2009; Oquendo et al., 2003b; Willeumier et al., 2011) and decreased FA in the cingulum and decreased amygdala-rPFC and dACC connectivity associated with current suicide ideation (Chase et al., 2017; Johnston et al., 2017; Yurgelun-Todd et al., 2011). The ALIC provides connections within frontostriatal-thalamic circuits, and abnormalities in this tract could result in difficulties in flexibly generating alternate behavioral responses and greater risk-taking (Duran et al., 2009; Linke et al., 2013; Poletti et al., 2015). Progressive decreases in FA in the vPFC was observed in the area of the UF. Abnormalities in the UF are likely to contribute to altered emotional regulation, reward processing, and impulsive behavior (Olson et al., 2015; Thiebaut de Schotten et al., 2012). Decreased FA in dorsal WM, including progressive decreases in the dlPFC, may disrupt higher-order executive functions, attention, and self-referential processing (Andrews-Hanna et al., 2010; Lemogne et al., 2012; Levy and Goldman-Rakic, 2000; Poletti et al., 2015).

Adolescent suicide attempters show deficits in emotional regulation (Esposito et al., 2003; Johnston et al., 2017; Pan et al., 2013; Zlotnick et al., 1997), with studies suggesting an attempt may occur as a behavioral approach to end unbearable affective states (Reisch et al., 2010). Abnormal self-referential thinking focused on emotional dysregulation is suggested to contribute to development of suicide-related behavior in mood disorders (Marchand et al., 2011). Indeed, recall of suicidal episode(s) is associated with altered rPFC activation in attempters (Reisch et al., 2010) possibly suggesting decreased mental flexibility and self-referential thinking. Combined gray and WM abnormalities in ventral and dorsal systems may alter emotional regulation and evaluation of risk and bias attention towards internalizing state, decreasing mental flexibility and resulting in subsequent risky decisions and behavioral responses. Study of structure-function and behavioral relationships that contribute to suicide-related behavior are needed.

During the follow-up period, 37% of the adolescents/young adults with a mood disorder attempted suicide. While estimated rates of suicide attempt in youth with mood disorders vary (Isometsa, 2014), this rate is consistent with estimates of attempts in adolescents with mood disorders and especially if they have characteristics that increase risk for suicide attempts, which are also present in this study sample, including comorbid A/SUDs, anxiety disorders, and/or past suicide attempt (Algorta et al., 2011; Goldstein et al., 2012; Hauser et al., 2013; Malone et al., 1995; Schaffer et al., 2015a; Strober et al., 1995). We observed more individuals in the Future-SA group, compared to the NonFuture-SA group, had attempted suicide prior to their baseline scan and had comorbid anxiety disorders consistent with evidence that past attempts and comorbid anxiety disorders are risk factors for future attempts (Costa Lda et al., 2015; Hawton et al., 2013; Oquendo et al., 2006; Sudol and Mann, 2017). A/SUDs, including nicotine dependence, are also strongly supported as risk factors for suicide attempts (Bohnert et al., 2014; Goldstein et al., 2008; Hawton et al., 2013; Oquendo et al., 2010; Oquendo et al., 2004). Alcohol use during adolescence has been shown to differentiate between adolescents who attempted suicide and those with suicidal ideation only (McManama O'Brien et al., 2014). We did not observe differences between suicide groups in number of individuals with a history of A/SUDs or nicotine use. However, regional GMV differences reported in this manuscript, suggested to be associated with risk for future suicide attempt, greatly overlap with recently reported regional GMV differences associated with risk for future alcohol and cannabis use problems in adolescents with BD (Lippard et al., 2017). Interactions between longitudinal brain changes and development of A/SUDs and suicide-related behavior warrants more study. We did not observe a difference in impulsivity scores between suicide groups. However, lower baseline FA in the dmPFC and dlPFC was associated with greater cognitive-attentional impulsivity within future attempters. Conflicting findings have been reported regarding an association between impulsivity and suicide-related behavior (Parmentier et al., 2012; Swann et al., 2005; Swann et al., 2008). Data could suggest impulsivity may present as more of a risk factor in a subset of individuals (e.g. individuals with greater deficits in emotional regulation, mental flexibility, self-referential thinking). Greater impulsivity differences may also emerge over time. A/SUDs are suggested to increase impulsivity (McManama O'Brien and Berzin, 2012; Swann et al., 2004). While speculative, it is possible differences in impulsivity may exist between attempter groups at the time of future attempt and clinical factors, such as A/SUDs, may influence this relationship.

We did not observe differences in caudate or insula GMV. Subcortical and paralimbic GMV differences have primarily been reported in adults with at least one prior suicide attempt (Benedetti et al., 2011; Colle et al., 2015; Gosnell et al., 2016; Monkul et al., 2007; Wagner et al., 2011; Willeumier et al., 2011). It is possible underlying mechanisms contributing to suicide attempts may differ in older adults compared to youth. Alternatively, certain clinical trajectories may be associated with neural phenotypes that emerge over time and contribute to development of suicide-related behavior.

We did not have the power to investigate diagnostic group (BD, MDD) by attempter group (Future-SA, NonFuture-SA) interactions. Lower regional GMV and FA were observed in both BD and MDD groups in post hoc exploratory analysis, stratified by diagnostic group, comparing Future-SA and NonFuture-SA groups, with extracted GMV and FA from clusters as the dependent variable (not shown). Findings therefore may generally represent mechanisms contributing to risk of suicide attempt in mood disorders. Differences in suicide-related behavior between BD and MDD are suggested, including attempts being more lethal and occurring at a greater frequency (Holma et al., 2014; Raja and Azzoni, 2004) but less associated with feelings of hopelessness in BD (Zalsman et al., 2006). While more individuals with BD made a future suicide attempt (41% vs. 25% with MDD) this was not statistically significant.

Study limitations include limited power; findings should therefore be considered preliminary and future studies are needed to confirm regional findings suggested to be associated with risk and development of suicide attempt. Certain clinical features—e.g. mood state, rapid cycling, lifetime psychosis—are associated with increased risk for suicide attempts (Gao et al., 2009; Schaffer et al., 2015a; Strakowski et al., 1996). While we did not see differences between groups in these characteristics, we were underpowered to investigate demographic and clinical heterogeneous features. Individuals were re-assessed for suicide-related behavior on average three years after their baseline scan. A longer follow-up period may identify more individuals who transition to making an attempt or show more stable clinical phenotypes providing greater sensitivity for identifying mechanisms of risk or resiliency. In the Future-SA group, suicide attempt occurred sometime during the follow-up period. Progressive decreases in FA observed in future attempters therefore could have emerged before, or as a result of, their future attempt. Studies with multiple and more frequent follow-up MRI assessments are needed to disentangle these temporal relationships. While not all participants were euthymic, exploratory t-tests suggest differences in mood state (being in an elevated or depressed state compared to euthymic state) did not contribute to lower GMV or FA reported (not shown). Results were considered significant in hypothesized regions at p<0.005 uncorrected. As this is the first study to our knowledge investigating GMV and FA predictors of, and longitudinal changes associated with, suicide attempt, we wanted to avoid strict correction so results could help generate hypotheses for future study. We did not correct for multiple comparisons. Therefore, it is important caution is taken when interpreting results at this uncorrected threshold as it raises the risk for type I errors. These results should be viewed as preliminary with future studies incorporating larger sample sizes to confirm and extend these findings.

Future work is warranted with incorporation of a typically developing comparison group, and to investigate differences in brain functioning that may predict future attempts. Nonsuicidal self-injury behavior was not investigated here and warrants study. Additionally, research on gene and environmental factors that may mediate neural phenotypes associated with risk are needed as recently discussed (Isohookana et al., 2013; Sood and Linker, 2017; Sunnqvist et al., 2008). For example, we recently reported genetic variation in Ankyrin G is associated with lower FA in WM in the vPFC, ALIC, and dmPFC; an association between a prior suicide attempt and WM differences associated with Ankyrin G was reported (Lippard et al., 2016). Differences in family functioning and stress are also reported to increase risk for suicide ideation (Goldstein et al., 2009; Goldstein et al., 2011). More work is needed systematically investigating medications, brain development, psychosocial functioning, and risk for suicide-related behavior. An exploratory analysis (not shown) did show significant associations between GMV and FA in the regions of findings after adjusting for suicide attempt status, however these associations did not survive correction for multiple comparisons. Future work is warranted investigating the relationship between gray and white matter in the context of suicide attempts. As previously suggested (Meyer et al., 2010; Schaffer et al., 2015b), prospective data investigating treatment and clinical drug trials adopting standard suicide-related screening instruments could greatly benefit our understanding of pharmacotherapy and risk for suicide attempt.

In summary, data from this preliminary longitudinal study suggests baseline GMV and WM FA differences and differences in longitudinal WM FA changes are associated with future suicide attempts in adolescents/young adults with BD or MDD. Findings suggest lower GMV in vPFC and dorsal rPFC and lower FA in the dmPFC, ALIC, and dorsal cingulum are associated with future attempts and could represent risk factors for future attempts in adolescents/young adults with mood disorders. Preliminary evidence also suggest abnormalities in vPFC and dorsal frontal WM are progressive and may emerge as suicide-related behavior develops during adolescence/young adulthood. More longitudinal research that investigates neural predictors and changes over time, dynamic changes in suicide-related behavior (development of ideation and transitions to planning and acting out an attempt), influence of clinical diagnosis and characteristics, sex, genes, and environment (e.g. stress and A/SUDs), is critically needed to elucidate mechanisms of risk and identify novel prevention and intervention targets.

Highlights.

Suicide in adolescents is prevalent and mood disorders are the most common risk factor; targets for prevention of suicide in adolescents with mood disorders are critically needed.

Magnetic resonance imaging methods were used to investigate gray and white matter structure in prefrontal systems associated with risk for, and development of, future suicide.

In adolescents with mood disorders, structural differences in gray and white matter of frontal systems, as well as changes over time in white matter, were associated with future suicide attempts.

The study provides evidence that developmental alterations in the structure within frontal systems may increase risk for suicide attempts and are potential targets to prevent suicide.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS:

The authors were supported by research grants from the National Institutes of Health (NIH) RC1MH088366 (HPB), R01MH070902 (HPB), R01MH069747 (HPB), T32MH014276 (ETCL), T32DA022975 (ETCL), K01MH086621 (FW), and UL1TR000142 from the National Center for Advancing Translational Science (HPB), as well as the American Foundation for Suicide Prevention (HPB, ETCL), International Bipolar Foundation (HPB), Brain and Behavior Research Foundation (HPB, FW), MQ Brighter Futures Program (HPB), For the Love of Travis (HPB), Women’s Health Research at Yale (HPB) and The John and Hope Furth Endowment (HPB). We thank Cheryl Lacadie, Karen A. Martin, Terry Hickey, and Hedy Sarofin, for their technical expertise, and the research subjects for their participation.

Footnotes

DISCLOSURES:

Maria Oquendo receives royalties for the commercial use of the Columbia Suicide Severity Rating Scale and her family owns stock in Bristol Myers Squibb. Hilary Blumberg received an honorarium for a talk from Aetna. Other authors have no financial conflicts of interest to report.

REFERENCES

- Abreu LN, Lafer B, Baca-Garcia E, Oquendo MA, 2009. Suicidal ideation and suicide attempts in bipolar disorder type I: an update for the clinician. Rev Bras Psiquiatr 31, 271–280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Algorta GP, Youngstrom EA, Frazier TW, Freeman AJ, Youngstrom JK, Findling RL, 2011. Suicidality in pediatric bipolar disorder: predictor or outcome of family processes and mixed mood presentation? Bipolar Disord 13, 76–86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amen DG, Prunella JR, Fallon JH, Amen B, Hanks C, 2009. A comparative analysis of completed suicide using high resolution brain SPECT imaging. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci 21, 430–439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andrews-Hanna JR, Reidler JS, Sepulcre J, Poulin R, Buckner RL, 2010. Functional-anatomic fractionation of the brain's default network. Neuron 65, 550–562. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beck AT, Beck R, Kovacs M, 1975. Classification of suicidal behaviors: I. Quantifying intent and medical lethality. Am J Psychiatry 132, 285–287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beck AT, Kovacs M, Weissman A, 1979. Assessment of suicidal intention: the Scale for Suicide Ideation. J Consult Clin Psychol 47, 343–352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benedetti F, Radaelli D, Poletti S, Locatelli C, Falini A, Colombo C, Smeraldi E, 2011. Opposite effects of suicidality and lithium on gray matter volumes in bipolar depression. J Affect Disord 135, 139–147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bijttebier S, Caeyenberghs K, van den Ameele H, Achten E, Rujescu D, Titeca K, van Heeringen C, 2015. The Vulnerability to Suicidal Behavior is Associated with Reduced Connectivity Strength. Front Hum Neurosci 9, 632. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bohnert KM, Ilgen MA, McCarthy JF, Ignacio RV, Blow FC, Katz IR, 2014. Tobacco use disorder and the risk of suicide mortality. Addiction 109, 155–162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burgess PW, Dumontheil I, Gilbert SJ, 2007. The gateway hypothesis of rostral prefrontal cortex (area 10) function. Trends Cogn Sci 11, 290–298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chase HW, Segreti AM, Keller TA, Cherkassky VL, Just MA, Pan LA, Brent DA, 2017. Alterations of functional connectivity and intrinsic activity within the cingulate cortex of suicidal ideators. J Affect Disord 212, 78–85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chehil S, Kutcher S, 2011. Suicide risk assessment, Suicide risk management: a manual for health professionals 2nd ed. John Wiley and Sons, Ltd., Chichester, UK. [Google Scholar]

- Chen YW, Dilsaver SC, 1996. Lifetime rates of suicide attempts among subjects with bipolar and unipolar disorders relative to subjects with other Axis I disorders. Biol Psychiatry 39, 896–899. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark L, Bechara A, Damasio H, Aitken MR, Sahakian BJ, Robbins TW, 2008. Differential effects of insular and ventromedial prefrontal cortex lesions on risky decision-making. Brain 131, 1311–1322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colle R, Chupin M, Cury C, Vandendrie C, Gressier F, Hardy P, Falissard B, Colliot O, Ducreux D, Corruble E, 2015. Depressed suicide attempters have smaller hippocampus than depressed patients without suicide attempts. J Psychiatr Res 61, 13–18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Costa Lda S, Alencar AP, Nascimento Neto PJ, dos Santos Mdo S, da Silva CG, Pinheiro Sde F, Silveira RT, Bianco BA, Pinheiro RF Jr., de Lima MA, Reis AO, Rolim Neto ML, 2015. Risk factors for suicide in bipolar disorder: a systematic review. J Affect Disord 170, 237–254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cox Lippard ET, Johnston JA, Blumberg HP, 2014. Neurobiological risk factors for suicide: insights from brain imaging. Am J Prev Med 47, S152–162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Craig AD, 2002. How do you feel? Interoception: the sense of the physiological condition of the body. Nat Rev Neurosci 3, 655–666. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cyprien F, de Champfleur NM, Deverdun J, Olie E, Le Bars E, Bonafe A, Mura T, Jollant F, Courtet P, Artero S, 2016. Corpus callosum integrity is affected by mood disorders and also by the suicide attempt history: A diffusion tensor imaging study. J Affect Disord 206, 115–124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ding Y, Lawrence N, Olie E, Cyprien F, le Bars E, Bonafe A, Phillips ML, Courtet P, Jollant F, 2015. Prefrontal cortex markers of suicidal vulnerability in mood disorders: a model-based structural neuroimaging study with a translational perspective. Transl Psychiatry 5, e516. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dumontheil I, Burgess PW, Blakemore SJ, 2008. Development of rostral prefrontal cortex and cognitive and behavioural disorders. Dev Med Child Neurol 50, 168–181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duran FL, Hoexter MQ, Valente AA Jr., Miguel EC, Busatto GF, 2009. Association between symptom severity and internal capsule volume in obsessive-compulsive disorder. Neurosci Lett 452, 68–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Esposito C, Spirito A, Boergers J, Donaldson D, 2003. Affective, behavioral, and cognitive functioning in adolescents with multiple suicide attempts. Suicide Life Threat Behav 33, 389–399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Etkin A, Egner T, Kalisch R, 2011. Emotional processing in anterior cingulate and medial prefrontal cortex. Trends Cogn Sci 15, 85–93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- First MB, Spitzer RL, Gibbon M, Williams JBW, 1995. Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis I & II Disorders (Version 2.0). New York State Psychiatric Institute, New York. [Google Scholar]

- Forman SD, Cohen JD, Fitzgerald M, Eddy WF, Mintun MA, Noll DC, 1995. Improved assessment of significant activation in functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI): use of a cluster-size threshold. Magn Reson Med 33, 636–647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao K, Tolliver BK, Kemp DE, Ganocy SJ, Bilali S, Brady KL, Findling RL, Calabrese JR, 2009. Correlates of historical suicide attempt in rapid-cycling bipolar disorder: a cross-sectional assessment. J Clin Psychiatry 70, 1032–1040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giakoumatos CI, Tandon N, Shah J, Mathew IT, Brady RO, Clementz BA, Pearlson GD, Thaker GK, Tamminga CA, Sweeney JA, Keshavan MS, 2013. Are structural brain abnormalities associated with suicidal behavior in patients with psychotic disorders? J Psychiatr Res 47, 1389–1395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilbert KE, Kalmar JH, Womer FY, Markovich PJ, Pittman B, Nolen-Hoeksema S, Blumberg HP, 2011. Impulsivity in Adolescent Bipolar Disorder. Acta neuropsychiatrica 23, 57–61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilbert SJ, Spengler S, Simons JS, Steele JD, Lawrie SM, Frith CD, Burgess PW, 2006. Functional specialization within rostral prefrontal cortex (area 10): a meta-analysis. J Cogn Neurosci 18, 932–948. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldstein BI, Birmaher B, Axelson DA, Goldstein TR, Esposito-Smythers C, Strober MA, Hunt J, Leonard H, Gill MK, Iyengar S, Grimm C, Yang M, Ryan ND, Keller MB, 2008. Significance of cigarette smoking among youths with bipolar disorder. Am J Addict 17, 364–371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldstein TR, Birmaher B, Axelson D, Goldstein BI, Gill MK, Esposito-Smythers C, Ryan ND, Strober MA, Hunt J, Keller M, 2009. Family environment and suicidal ideation among bipolar youth. Arch Suicide Res 13, 378–388. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldstein TR, Ha W, Axelson DA, Goldstein BI, Liao F, Gill MK, Ryan ND, Yen S, Hunt J, Hower H, Keller M, Strober M, Birmaher B, 2012. Predictors of prospectively examined suicide attempts among youth with bipolar disorder. Arch Gen Psychiatry 69, 1113–1122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldstein TR, Obreja M, Shamseddeen W, Iyengar S, Axelson DA, Goldstein BI, Monk K, Hickey MB, Sakolsky D, Kupfer DJ, Brent DA, Birmaher B, 2011. Risk for suicidal ideation among the offspring of bipolar parents: results from the Bipolar Offspring Study (BIOS). Arch Suicide Res 15, 207–222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodman M, Hazlett EA, Avedon JB, Siever DR, Chu KW, New AS, 2011. Anterior cingulate volume reduction in adolescents with borderline personality disorder and co-morbid major depression. J Psychiatr Res 45, 803–807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gosnell SN, Velasquez KM, Molfese DL, Molfese PJ, Madan A, Fowler JC, Christopher Frueh B, Baldwin PR, Salas R, 2016. Prefrontal cortex, temporal cortex, and hippocampus volume are affected in suicidal psychiatric patients. Psychiatry Res 256, 50–56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gusnard DA, Akbudak E, Shulman GL, Raichle ME, 2001. Medial prefrontal cortex and self-referential mental activity: relation to a default mode of brain function. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 98, 4259–4264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hauser M, Galling B, Correll CU, 2013. Suicidal ideation and suicide attempts in children and adolescents with bipolar disorder: a systematic review of prevalence and incidence rates, correlates, and targeted interventions. Bipolar Disord 15, 507–523. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hawton K, Casanas ICC, Haw C, Saunders K, 2013. Risk factors for suicide in individuals with depression: a systematic review. J Affect Disord 147, 17–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holma KM, Haukka J, Suominen K, Valtonen HM, Mantere O, Melartin TK, Sokero TP, Oquendo MA, Isometsa ET, 2014. Differences in incidence of suicide attempts between bipolar I and II disorders and major depressive disorder. Bipolar Disord 16, 652–661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Isohookana R, Riala K, Hakko H, Rasanen P, 2013. Adverse childhood experiences and suicidal behavior of adolescent psychiatric inpatients. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry 22, 13–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Isometsa E, 2014. Suicidal behaviour in mood disorders--who, when, and why? Can J Psychiatry 59, 120–130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jia Z, Huang X, Wu Q, Zhang T, Lui S, Zhang J, Amatya N, Kuang W, Chan RC, Kemp GJ, Mechelli A, Gong Q, 2010. High-field magnetic resonance imaging of suicidality in patients with major depressive disorder. Am J Psychiatry 167, 1381–1390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jia Z, Wang Y, Huang X, Kuang W, Wu Q, Lui S, Sweeney JA, Gong Q, 2014. Impaired frontothalamic circuitry in suicidal patients with depression revealed by diffusion tensor imaging at 3.0 T. J Psychiatry Neurosci 39, 170–177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnston JA, Wang F, Liu J, Blond BN, Wallace A, Liu J, Spencer L, Cox Lippard ET, Purves KL, Landeros-Weisenberger A, Hermes E, Pittman B, Zhang S, King R, Martin A, Oquendo MA, Blumberg HP, 2017. Multimodal Neuroimaging of Frontolimbic Structure and Function Associated With Suicide Attempts in Adolescents and Young Adults With Bipolar Disorder. Am J Psychiatry, appiajp201615050652. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaufman J, Birmaher B, Brent D, Rao U, Flynn C, Moreci P, Williamson D, Ryan N, 1997. Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia for School-Age Children-Present and Lifetime Version (K-SADS-PL): initial reliability and validity data. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 36, 980–988. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koechlin E, Hyafil A, 2007. Anterior prefrontal function and the limits of human decision-making. Science 318, 594–598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kovach CK, Daw ND, Rudrauf D, Tranel D, O'Doherty JP, Adolphs R, 2012. Anterior prefrontal cortex contributes to action selection through tracking of recent reward trends. J Neurosci 32, 8434–8442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kringelbach ML, Rolls ET, 2004. The functional neuroanatomy of the human orbitofrontal cortex: evidence from neuroimaging and neuropsychology. Prog Neurobiol 72, 341–372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee YJ, Kim S, Gwak AR, Kim SJ, Kang SG, Na KS, Son YD, Park J, 2016. Decreased regional gray matter volume in suicide attempters compared to suicide non-attempters with major depressive disorders. Compr Psychiatry 67, 59–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lemogne C, Delaveau P, Freton M, Guionnet S, Fossati P, 2012. Medial prefrontal cortex and the self in major depression. J Affect Disord 136, e1–e11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levy R, Goldman-Rakic PS, 2000. Segregation of working memory functions within the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex. Exp Brain Res 133, 23–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lieberman MD, Cunningham WA, 2009. Type I and Type II error concerns in fMRI research: re-balancing the scale. Soc Cogn Affect Neurosci 4, 423–428. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Linke J, King AV, Poupon C, Hennerici MG, Gass A, Wessa M, 2013. Impaired anatomical connectivity and related executive functions: differentiating vulnerability and disease marker in bipolar disorder. Biol Psychiatry 74, 908–916. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lippard ET, Jensen KP, Wang F, Johnston JA, Spencer L, Pittman B, Gelernter J, Blumberg HP, 2016. Effects of ANK3 variation on gray and white matter in bipolar disorder. Mol Psychiatry. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lippard ET, Mazure CM, Johnston JA, Spencer L, Weathers J, Pittman B, Wang F, Blumberg HP, 2017. Brain circuitry associated with the development of substance use in bipolar disorder and preliminary evidence for sexual dimorphism in adolescents. J Neurosci Res 95, 777–791. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mahon K, Burdick KE, Wu J, Ardekani BA, Szeszko PR, 2012. Relationship between suicidality and impulsivity in bipolar I disorder: a diffusion tensor imaging study. Bipolar Disord 14, 80–89. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malone KM, Haas GL, Sweeney JA, Mann JJ, 1995. Major depression and the risk of attempted suicide. J Affect Disord 34, 173–185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marchand WR, Lee JN, Garn C, Thatcher J, Gale P, Kreitschitz S, Johnson S, Wood N, 2011. Striatal and cortical midline activation and connectivity associated with suicidal ideation and depression in bipolar II disorder. J Affect Disord 133, 638–645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin PC, Zimmer TJ, Pan LA, 2015. Magnetic resonance imaging markers of suicide attempt and suicide risk in adolescents. CNS Spectr 20, 355–358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsuo K, Nielsen N, Nicoletti MA, Hatch JP, Monkul ES, Watanabe Y, Zunta-Soares GB, Nery FG, Soares JC, 2010. Anterior genu corpus callosum and impulsivity in suicidal patients with bipolar disorder. Neurosci Lett 469, 75–80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McManama O'Brien KH, Becker SJ, Spirito A, Simon V, Prinstein MJ, 2014. Differentiating adolescent suicide attempters from ideators: examining the interaction between depression severity and alcohol use. Suicide Life Threat Behav 44, 23–33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McManama O'Brien KH, Berzin SC, 2012. Examining the impact of psychiatric diagnosis and comorbidity on the medical lethality of adolescent suicide attempts. Suicide Life Threat Behav 42, 437–444. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyer RE, Salzman C, Youngstrom EA, Clayton PJ, Goodwin FK, Mann JJ, Alphs LD, Broich K, Goodman WK, Greden JF, Meltzer HY, Normand SL, Posner K, Shaffer D, Oquendo MA, Stanley B, Trivedi MH, Turecki G, Beasley CM Jr., Beautrais AL, Bridge JA, Brown GK, Revicki DA, Ryan ND, Sheehan DV, 2010. Suicidality and risk of suicide--definition, drug safety concerns, and a necessary target for drug development: a consensus statement. J Clin Psychiatry 71, e1–e21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monkul ES, Hatch JP, Nicoletti MA, Spence S, Brambilla P, Lacerda AL, Sassi RB, Mallinger AG, Keshavan MS, Soares JC, 2007. Fronto-limbic brain structures in suicidal and non-suicidal female patients with major depressive disorder. Mol Psychiatry 12, 360–366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nery-Fernandes F, Rocha MV, Jackowski A, Ladeia G, Guimaraes JL, Quarantini LC, Araujo-Neto CA, De Oliveira IR, Miranda-Scippa A, 2012. Reduced posterior corpus callosum area in suicidal and non-suicidal patients with bipolar disorder. J Affect Disord 142, 150–155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nock MK, Green JG, Hwang I, McLaughlin KA, Sampson NA, Zaslavsky AM, Kessler RC, 2013. Prevalence, correlates, and treatment of lifetime suicidal behavior among adolescents: results from the National Comorbidity Survey Replication Adolescent Supplement. JAMA Psychiatry 70, 300–310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olson IR, Von Der Heide RJ, Alm KH, Vyas G, 2015. Development of the uncinate fasciculus: Implications for theory and developmental disorders. Dev Cogn Neurosci 14, 50–61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olvet DM, Peruzzo D, Thapa-Chhetry B, Sublette ME, Sullivan GM, Oquendo MA, Mann JJ, Parsey RV, 2014. A diffusion tensor imaging study of suicide attempters. J Psychiatr Res 51, 60–67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oquendo MA, Currier D, Liu SM, Hasin DS, Grant BF, Blanco C, 2010. Increased risk for suicidal behavior in comorbid bipolar disorder and alcohol use disorders: results from the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions (NESARC). J Clin Psychiatry 71, 902–909. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oquendo MA, Currier D, Mann JJ, 2006. Prospective studies of suicidal behavior in major depressive and bipolar disorders: what is the evidence for predictive risk factors? Acta Psychiatr Scand 114, 151–158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oquendo MA, Galfalvy H, Russo S, Ellis SP, Grunebaum MF, Burke A, Mann JJ, 2004. Prospective study of clinical predictors of suicidal acts after a major depressive episode in patients with major depressive disorder or bipolar disorder. Am J Psychiatry 161, 1433–1441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oquendo MA, Galfalvy H, Sullivan GM, Miller JM, Milak MM, Sublette ME, Cisneros-Trujillo S, Burke AK, Parsey RV, Mann JJ, 2016. Positron emission tomographic imaging of the serotonergic system and prediction of risk and lethality of future suicidal behavior. JAMA Psychiatry 73, 1048–1055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oquendo MA, Halberstam B, Mann J, 2003a. Risk factors for suicidal behavior: the utility and limitations of research instruments, In: First MB (Ed.), Standardized Evaluation in Clinical Practice. American Psychiatric Publishing, Arlington, VA, pp. 103–130. [Google Scholar]

- Oquendo MA, Placidi GP, Malone KM, Campbell C, Keilp J, Brodsky B, Kegeles LS, Cooper TB, Parsey RV, van Heertum RL, Mann JJ, 2003b. Positron emission tomography of regional brain metabolic responses to a serotonergic challenge and lethality of suicide attempts in major depression. Arch Gen Psychiatry 60, 14–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ordaz SJ, Goyer MS, Ho TC, Singh MK, Gotlib IH, 2018. Network basis of suicidal ideation in depressed adolescents. J Affect Disord 226, 92–99. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pan LA, Hassel S, Segreti AM, Nau SA, Brent DA, Phillips ML, 2013. Differential patterns of activity and functional connectivity in emotion processing neural circuitry to angry and happy faces in adolescents with and without suicide attempt. Psychol Med 43, 2129–2142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pan LA, Phillips ML, 2014. Toward identification of neural markers of suicide risk in adolescents. Neuropsychopharmacology 39, 236–237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parmentier C, Etain B, Yon L, Misson H, Mathieu F, Lajnef M, Cochet B, Raust A, Kahn JP, Wajsbrot-Elgrabli O, Cohen R, Henry C, Leboyer M, Bellivier F, 2012. Clinical and dimensional characteristics of euthymic bipolar patients with or without suicidal behavior. Eur Psychiatry 27, 570–576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patton JH, Stanford MS, Barratt ES, 1995. Factor structure of the Barratt impulsiveness scale. J Clin Psychol 51, 768–774. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poletti S, Bollettini I, Mazza E, Locatelli C, Radaelli D, Vai B, Smeraldi E, Colombo C, Benedetti F, 2015. Cognitive performances associate with measures of white matter integrity in bipolar disorder. J Affect Disord 174, 342–352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raja M, Azzoni A, 2004. Suicide attempts: differences between unipolar and bipolar patients and among groups with different lethality risk. J Affect Disord 82, 437–442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reisch T, Seifritz E, Esposito F, Wiest R, Valach L, Michel K, 2010. An fMRI study on mental pain and suicidal behavior. J Affect Disord 126, 321–325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schaffer A, Isometsa ET, Azorin JM, Cassidy F, Goldstein T, Rihmer Z, Sinyor M, Tondo L, Moreno DH, Turecki G, Reis C, Kessing LV, Ha K, Weizman A, Beautrais A, Chou YH, Diazgranados N, Levitt AJ, Zarate CA Jr., Yatham L, 2015a. A review of factors associated with greater likelihood of suicide attempts and suicide deaths in bipolar disorder: Part II of a report of the International Society for Bipolar Disorders Task Force on Suicide in Bipolar Disorder. Aust N Z J Psychiatry 49, 1006–1020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schaffer A, Isometsa ET, Tondo L, Moreno DH, Sinyor M, Kessing LV, Turecki G, Weizman A, Azorin JM, Ha K, Reis C, Cassidy F, Goldstein T, Rihmer Z, Beautrais A, Chou YH, Diazgranados N, Levitt AJ, Zarate CA Jr., Yatham L, 2015b. Epidemiology, neurobiology and pharmacological interventions related to suicide deaths and suicide attempts in bipolar disorder: Part I of a report of the International Society for Bipolar Disorders Task Force on Suicide in Bipolar Disorder. Aust N Z J Psychiatry 49, 785–802. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sood AB, Linker J, 2017. Proximal Influences on the Trajectory of Suicidal Behaviors and Suicide during the Transition from Adolescence to Young Adulthood. Child Adolesc Psychiatr Clin N Am 26, 235–251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strakowski SM, McElroy SL, Keck PE Jr., West SA, 1996. Suicidality among patients with mixed and manic bipolar disorder. Am J Psychiatry 153, 674–676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strober M, Schmidt-Lackner S, Freeman R, Bower S, Lampert C, DeAntonio M, 1995. Recovery and relapse in adolescents with bipolar affective illness: a five-year naturalistic, prospective follow-up. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 34, 724–731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sudol K, Mann JJ, 2017. Biomarkers of Suicide Attempt Behavior: Towards a Biological Model of Risk. Curr Psychiatry Rep 19, 31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sunnqvist C, Westrin A, Traskman-Bendz L, 2008. Suicide attempters: biological stressmarkers and adverse life events. Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci 258, 456–462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swann AC, Dougherty DM, Pazzaglia PJ, Pham M, Moeller FG, 2004. Impulsivity: a link between bipolar disorder and substance abuse. Bipolar Disord 6, 204–212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swann AC, Dougherty DM, Pazzaglia PJ, Pham M, Steinberg JL, Moeller FG, 2005. Increased impulsivity associated with severity of suicide attempt history in patients with bipolar disorder. Am J Psychiatry 162, 1680–1687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swann AC, Steinberg JL, Lijffijt M, Moeller FG, 2008. Impulsivity: differential relationship to depression and mania in bipolar disorder. J Affect Disord 106, 241–248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thiebaut de Schotten M, Dell'Acqua F, Valabregue R, Catani M, 2012. Monkey to human comparative anatomy of the frontal lobe association tracts. Cortex 48, 82–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wagner G, Koch K, Schachtzabel C, Schultz CC, Sauer H, Schlosser RG, 2011. Structural brain alterations in patients with major depressive disorder and high risk for suicide: evidence for a distinct neurobiological entity? Neuroimage 54, 1607–1614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wagner G, Schultz CC, Koch K, Schachtzabel C, Sauer H, Schlosser RG, 2012. Prefrontal cortical thickness in depressed patients with high-risk for suicidal behavior. J Psychiatr Res 46, 1449–1455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Willeumier K, Taylor DV, Amen DG, 2011. Decreased cerebral blood flow in the limbic and prefrontal cortex using SPECT imaging in a cohort of completed suicides. Transl Psychiatry 1, e28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yurgelun-Todd DA, Bueler CA, McGlade EC, Churchwell JC, Brenner LA, Lopez-Larson MP, 2011. Neuroimaging correlates of traumatic brain injury and suicidal behavior. Journal of Head Trauma Rehabilitation 26, 276–289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zalsman G, Braun M, Arendt M, Grunebaum MF, Sher L, Burke AK, Brent DA, Chaudhury SR, Mann JJ, Oquendo MA, 2006. A comparison of the medical lethality of suicide attempts in bipolar and major depressive disorders. Bipolar Disord 8, 558–565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zametkin AJ, Alter MR, Yemini T, 2001. Suicide in teenagers: assessment, management, and prevention. JAMA 286, 3120–3125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zisook S, Rush AJ, Lesser I, Wisniewski SR, Trivedi M, Husain MM, Balasubramani GK, Alpert JE, Fava M, 2007. Preadult onset vs. adult onset of major depressive disorder: a replication study. Acta Psychiatr Scand 115, 196–205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zlotnick C, Donaldson D, Spirito A, Pearlstein T, 1997. Affect regulation and suicide attempts in adolescent inpatients. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 36, 793–798. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]