This study assesses the frequency of PDGFRB mutations in sporadic solitary myofibroma and multifocal myofibromatosis found in samples from an international population of adults and children and describes their use as a diagnostic biomarker and a therapeutic target.

Key Points

Questions

What is the frequency of PDGFRB mutations in sporadic solitary myofibroma and multifocal myofibromatosis, and what are the implications for clinical management?

Findings

In this international study of 69 patient samples, we identified activating PDGFRB mutations in children and infants but not adults, and the presence of mutations was strongly associated with multicentric disease. Most PDGFRB mutations were sensitive to the tyrosine kinase inhibitor imatinib, suggesting that they were attractive therapeutic targets.

Meaning

The findings suggest that the presence of PDGFRB activating mutations provides a molecular diagnostic test and a basis for targeted therapy of infantile myofibromatosis.

Abstract

Importance

Myofibroma is the most frequent fibrous tumor in children. Multicentric myofibroma (referred to as infantile myofibromatosis) is a life-threatening disease.

Objective

To determine the frequency, spectrum, and clinical implications of mutations in the PDGFRB receptor tyrosine kinase found in sporadic myofibroma and myofibromatosis.

Design, Setting, and Participants

In this retrospective study of 69 patients with sporadic myofibroma or myofibromatosis, 85 tumor samples were obtained and analyzed by targeted deep sequencing of PDGFRB. Mutations were confirmed by an alternative method of sequencing and were experimentally characterized to confirm gain of function and sensitivity to the tyrosine kinase inhibitor imatinib.

Main Outcomes and Measures

Frequency of gain-of-function PDGFRB mutations in sporadic myofibroma and myofibromatosis. Sensitivity to imatinib, as assessed experimentally.

Results

Of the 69 patients with tumor samples (mean [SD] age, 7.8 [12.7] years), 60 were children (87%; 29 girls [48%]) and 9 were adults (13%; 4 women [44%]). Gain-of-function PDGFRB mutations were found in samples from 25 children, with no mutation found in samples from adults. Mutations were particularly associated with severe multicentric disease (13 of 19 myofibromatosis cases [68%]). Although patients had no familial history, 3 of 25 mutations (12%) were likely to be germline, suggesting de novo heritable alterations. All of the PDGFRB mutations were associated with ligand-independent receptor activation, and all but one were sensitive to imatinib at clinically relevant concentrations.

Conclusions and Relevance

Gain-of-function mutations of PDGFRB in myofibromas may affect only children and be more frequent in the multicentric form of disease, albeit present in solitary pediatric myofibromas. These alterations may be sensitive to tyrosine kinase inhibitors. The PDGFRB sequencing appears to have a high value for diagnosis, prognosis, and therapy of soft-tissue tumors in children.

Introduction

Myofibromas are the most frequent fibrous tumors in children.1 The presence of multiple myofibromas in an individual defines infantile myofibromatosis (IMF). These benign tumors can appear in the skin, muscles, bones, and internal organs, and they often regress spontaneously. However, visceral involvement of myofibromatosis, sometimes referred to as generalized IMF,2 is a life-threatening disease.1 Unlike children, adults develop only solitary myofibromas. In 2013, the World Health Organization classified myofibroma among pericytic tumors, which also include myopericytoma, based on the morphologic continuum between these lesions.3

Recently, PDGFRB mutations were identified in a few familial4,5 and sporadic cases of IMF.6 The PDGFRB gene encodes a receptor tyrosine kinase that binds platelet-derived growth factor B (PDGFB) and platelet-derived growth factor D (PDGFD) and is highly expressed in fibroblasts and pericytes. A recent study5 showed that the PDGFRB variants found in IMF were oncogenic and sensitive to tyrosine kinase inhibitors, such as imatinib, in vitro. Recent clinical reports confirmed the safety and efficacy of tyrosine kinase inhibitors in 2 patients with PDGFRB mutations.7,8 In 1 patient, however, a PDGFRB mutation was identified that was fully resistant to imatinib in vitro,5 suggesting that primary resistance may be an issue. A limited number of patients with IMF has been analyzed, and the presence of mutations in adult myofibroma and in myopericytoma remains a matter of debate.9,10 The goal of the present study was to evaluate the value of PDGFRB mutations as a diagnostic biomarker and therapeutic target in a large group of patients.

Methods

We retrospectively collected archived samples from 102 patients from clinical centers in Belgium, France, the United States, and the Netherlands (the Dutch nationwide population-based pathology database [PALGA], Houten),11 who were diagnosed with sporadic myofibroma, myopericytoma, or myofibromatosis according to the World Health Organization classification. Tumor samples were analyzed by targeted deep sequencing of PDGFRB. Mutations were confirmed by an alternative method of sequencing and were experimentally characterized to confirm gain of function and sensitivity to the tyrosine kinase inhibitor imatinib (details are given in the eMethods in the Supplement). This study was approved by the medical ethics review board of the University of Louvain, Brussels, Belgium. Samples were retrospectively obtained from biobanks, and data were deidentified. One patient was included prospectively after diagnosis with written informed consent from a parent.

Statistical analysis was computed in R, version 3.5.1 (R Foundation) and Excel, 2016 version (Microsoft). Two-sided P < .05 was considered to be statistically significant.

Results

Of the 69 patients with tumor samples (mean [SD] age, 7.8 [12.7] years), 60 were children (87%; 29 girls [48%]) and 9 were adults (13%; 4 women [44%]); 85 samples were included in the analysis. None of the patients had a family history of myofibroma or myofibromatosis. The Table presents patient clinical characteristics. We extracted DNA from fresh frozen or formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded tissue and performed targeted deep sequencing of PDGFRB (coverage depth >1000×), as previously described.6

Table. Demographic and Clinical Characteristics of the Patients Overall and by Myofibromatosis Status.

| Characteristic | No. (%) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| All Patients | Patients With Myofibromatosis | ||

| Multicentrica | Solitary | ||

| Study patients | 69 | 19 | 50 |

| Sex | |||

| Male | 34 (49) | 9 (47) | 25 (50) |

| Female | 34 (49) | 10 (53) | 24 (48) |

| NA | 1 (1) | 0 | 1 (2) |

| Country of origin | |||

| Belgium | 26 (41) | 8 (42) | 18 (36) |

| France | 10 (13) | 4 (21) | 6 (12) |

| The Netherlands | 32 (48) | 6 (32) | 26 (52) |

| United States | 1 (1) | 1 (5) | 0 |

| Age at diagnosis, y | |||

| <2, y | 31 (45) | 15 (79) | 16 (32) |

| 2-18, y | 28 (41) | 4 (21) | 24 (48) |

| >18, y | 9 (13) | 0 | 9 (18) |

| NA | 1 (1) | 0 | 1 (2) |

| Mean (SD), y | 7.8 (12.7) | 1 (2) | 10 (12) |

| Visceral involvement | 8 (12) | 8 (42) | 0 |

| Treatment | |||

| Spontaneous involution | 9 (13) | 7 (37) | 2 (4) |

| Surgical resection | 55 (80) | 8 (42) | 48 (96) |

| Chemotherapy | 4 (6) | 4 (21) | 0 |

| Mutation status | |||

| PDGFRB mutant | 25 (36) | 13 (68) | 12 (24) |

| PDGFRB wild type | 44 (64) | 6 (32) | 38 (76) |

| PDGFRB mutants | |||

| Single hit | 14 (20) | 6 (32) | 8 (16) |

| Multiple hits | 11 (16) | 7 (37) | 4 (8) |

| Recurrence | 3 (4) | 1 (5) | 2 (4) |

| Mortality | 2 (3) | 2 (11) | 0 |

Abbreviation: NA, not available.

This subgroup includes the case of multicentric myopericytoma.

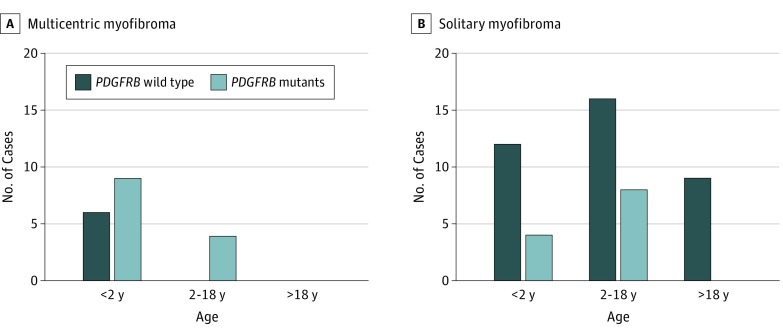

We identified PDGFRB mutations in 25 patients including infants and children but none in adults (Figure 1 and eTables 1 and 2 in the Supplement). The PDGFRB mutations were more frequent in IMF (68%) compared with solitary tumors (24%) (Fisher exact test, P = .002). Three patients carrying PDGFRB mutants had visceral involvement, including 1 patient with multicentric myopericytoma; none died of the disease.

Figure 1. PDGFRB Mutant Distribution by Patient Age and Myofibroma Subtype.

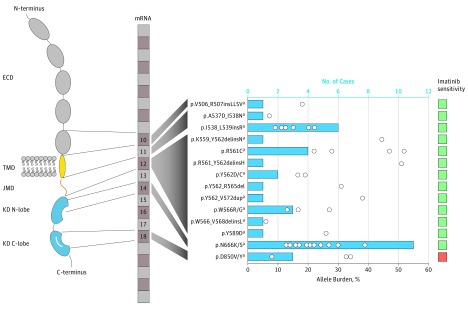

All mutations are reported in Figure 2. Of 25 patients with PDGFRB variants, 11 (44%) carried multiple mutations. Of the 11 patients, 7 (64%) had multicentric disease, with no significant association between multiple-hit status of PDGFRB and clinical phenotype. In 3 cases, these mutations were in cis (ie, on the same allele), as detailed in the eMethods in the Supplement. The mutations were detected at allele frequencies ranging from 6% to 52% (mean [SD], 20.3% [12.2%]) of sequencing reads (Figure 2).

Figure 2. PDGFRB Gain-of-Function Mutations in Myofibroma.

Variants are reported according to protein location and affected exon. The activation loop is represented in white in the C-lobe of the kinase domain. Pairs of mutations identified in multiple-hits samples were p.R561C + p.N666K, p.R561C + p.N666S, p.A537D + p.I538N, p.N666K + p.W566R, p.W566R + p.Y589D, p.Y562_R565del + p.N666K, and R561_Y562delinsH + p.N666K (eTable 1 and eTable 2 in the Supplement). Variants p.K559_Y562delinsN and p.N666K were identified in 2 distinct myopericytomas from the same patient; the variants p.N666K (c.1998C>G), p.N666K (C>A), p.W566_V568delinsL, and p.Y562D were identified in 4 distinct IMF lesions from the same patient. Blue bars indicate the frequency of each variant; white circles, allele burden; green, sensitive to imatinib; red, resistant to imatinib. ECD indicates extracellular domain; IMF, infantile myofibromatosis; JMD, juxta-membrane domain; KD, kinase domain; and TMD, transmembrane domain.

aVariants were validated by an alternative method.

Of the mutant cases, 17 (68%) had mutations located in the 2 classical hotspots of oncogenic mutations of receptor tyrosine kinases, the juxta-membrane and the kinase domains (forming the core of the catalytic part of the protein). There was an in-frame duplication of 33 nucleotides in the juxta-membrane domain. The remaining mutations were located in the transmembrane domain and the extracellular part of the receptor, a unique finding in our experiences with sequencing of PDGFRB, and an uncommon oncogenic event for other receptor tyrosine kinases.

Copy-number variation analysis by multiplex ligation-dependent probe amplification experiments for 12 samples, regardless of PDGFRB mutation status, did not reveal any amplification of the PDGFRB locus.

Discussion

We found a broad catalog of 18 different PDGFRB mutations in myofibroma lesions, 12 of which were novel. We validated most variants by allele-specific polymerase chain reaction or Sanger sequencing after cloning. The latter technique also allowed us to confirm the allele burden of the mutations, which was consistent with the percentage of mutant reads obtained from next-generation sequencing. Because samples contained variable amounts of adjacent normal tissue and tumor stromal cells, this proportion was indicative of the somatic or germline nature of the mutations. Although none of the 69 patients had a family history of myofibroma or myofibromatosis, our sequencing data suggested germline (likely de novo) mutations in 3 of 25 patients (12%) carrying a PDGFRB variant (eMethods in the Supplement). All 3 variants affected R561, the most frequently mutated residue in IMF families.4 Furthermore, they were all associated with somatic second hits at residue N666. Healthy tissue was not available to confirm the germline nature of the mutations. These results suggest that a substantial proportion of patients may require genetic counseling.

We also characterized the functional outcome of the variants by performing luciferase reporter assays as a readout of mitogen-activated protein kinases and signal transducers and activators of transcription. These pathways are potent downstream mediators of PDGFRB signaling.12 All the identified mutations were associated with constitutive activation of the receptor (eFigure in the Supplement), suggesting a potential causative nature and excluding passenger mutations. We then showed that these oncogenic forms of PDGFRB mutations were efficiently associated with inhibition by imatinib used at a clinically relevant concentration (eFigure in the Supplement). The only exception was the previously reported p.D850V mutant6 affecting the kinase activation loop. This high sensitivity rate to pharmacologic inhibitor contrasts with that of many tumor types harboring kinase mutations, in which primary resistance is frequent.

A recent study5 described the cooperation between a weak mutation affecting the juxta-membrane domain (ie, p.R561C) and a strong mutation of the kinase domain. The positive selection of 2 mutations on the same allele is unusual but has also been described for epidermal growth factor receptor in lung cancer and for endothelial tyrosine kinase in sporadic, multifocal venous malformations.13,14 In 2 cases, we identified different mutations in distinct lesions from the same patient. This finding suggests an underlying mechanism predisposing mesenchymal progenitor cells to PDGFRB mutation and, thereby, development of multiple pericytic lesions, each seeded by a different mutated cell-of-origin.

Of particular interest was an in-frame duplication of 33 nucleotides in the juxta-membrane domain, to our knowledge described here for the first time in PDGFRB, but highly reminiscent of the internal tandem duplications described in FMS-related tyrosine kinase 3 in acute myeloid leukemia.15

The presence of a PDGFRB mutation in myopericytoma is consistent with a recent report by Hung and Fletcher10 but contrasts with the report by Agaimy et al.9 The high frequency of PDGFRB mutations in IMF, myopericytoma, and solitary lesions affecting young children suggests that these entities may represent a morphologic continuum with common molecular bases, arguing for a refinement of the classification of these tumors as pericytic tumors with PDGFRB mutation.

Limitations

A limitation of our study is that we cannot rule out selection bias in our case series. This may explain the discrepancy with a previous report describing PDGFRB mutations in adult myofibromas using direct Sanger sequencing of polymerase chain reaction products.9 However, this technology is prone to false-positive results, and the results of that previous study await confirmation by an independent method.

Conclusions

The findings suggest that gain-of-function mutations of PDGFRB affect only children. They were more frequent in the multicentric form of the disease, albeit present in solitary pediatric myofibromas. The PDGFRB alteration status may help identify a specific patient subgroup to be carefully monitored. Our results shed light on the molecular basis of the pericytic tumors and point to the high value of PDGFRB sequencing for prognosis, diagnosis, and therapy of soft-tissue neoplasms in children.

eMethods. Study Design

eTable 1. Called Variants Related to Patients and Samples

eTable 2. Clinical Characteristics of Patients Harboring a PDGFRB Mutation

eFigure. Novel PDGFRB Mutations in Myofibroma Lesions Induce Constitutive Activation of PDGFRB and are Sensitive to Imatinib

References

- 1.Mashiah J, Hadj-Rabia S, Dompmartin A, et al. Infantile myofibromatosis: a series of 28 cases. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;71(2):264-270. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2014.03.035 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Oudijk L, den Bakker MA, Hop WC, et al. Solitary, multifocal and generalized myofibromas: clinicopathological and immunohistochemical features of 114 cases. Histopathology. 2012;60(6B):E1-E11. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2559.2012.04221.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jo VY, Fletcher CD. WHO classification of soft tissue tumours: an update based on the 2013 (4th) edition. Pathology. 2014;46(2):95-104. doi: 10.1097/PAT.0000000000000050 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cheung YH, Gayden T, Campeau PM, et al. A recurrent PDGFRB mutation causes familial infantile myofibromatosis. Am J Hum Genet. 2013;92(6):996-1000. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2013.04.026 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Arts FA, Chand D, Pecquet C, et al. PDGFRB mutants found in patients with familial infantile myofibromatosis or overgrowth syndrome are oncogenic and sensitive to imatinib. Oncogene. 2016;35(25):3239-3248. doi: 10.1038/onc.2015.383 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Arts FA, Sciot R, Brichard B, et al. PDGFRB gain-of-function mutations in sporadic infantile myofibromatosis. Hum Mol Genet. 2017;26(10):1801-1810. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddx081 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pond D, Arts FA, Mendelsohn NJ, Demoulin JB, Scharer G, Messinger Y. A patient with germ-line gain-of-function PDGFRB p.N666H mutation and marked clinical response to imatinib. Genet Med. 2018;20(1):142-150. doi: 10.1038/gim.2017.104 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mudry P, Slaby O, Neradil J, et al. Case report: rapid and durable response to PDGFR targeted therapy in a child with refractory multiple infantile myofibromatosis and a heterozygous germline mutation of the PDGFRB gene. BMC Cancer. 2017;17(1):119. doi: 10.1186/s12885-017-3115-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Agaimy A, Bieg M, Michal M, et al. Recurrent somatic PDGFRB mutations in sporadic infantile/solitary adult myofibromas but not in angioleiomyomas and myopericytomas. Am J Surg Pathol. 2017;41(2):195-203. doi: 10.1097/PAS.0000000000000752 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hung YP, Fletcher CDM. Myopericytomatosis: clinicopathologic analysis of 11 cases with molecular identification of recurrent PDGFRB alterations in myopericytomatosis and myopericytoma. Am J Surg Pathol. 2017;41(8):1034-1044. doi: 10.1097/PAS.0000000000000862 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Casparie M, Tiebosch AT, Burger G, et al. Pathology databanking and biobanking in the Netherlands, a central role for PALGA, the nationwide histopathology and cytopathology data network and archive. Cell Oncol. 2007;29(1):19-24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Demoulin JB, Essaghir A. PDGF receptor signaling networks in normal and cancer cells. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 2014;25(3):273-283. doi: 10.1016/j.cytogfr.2014.03.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Limaye N, Wouters V, Uebelhoer M, et al. Somatic mutations in angiopoietin receptor gene TEK cause solitary and multiple sporadic venous malformations. Nat Genet. 2009;41(1):118-124. doi: 10.1038/ng.272 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chen Z, Feng J, Saldivar JS, Gu D, Bockholt A, Sommer SS. EGFR somatic doublets in lung cancer are frequent and generally arise from a pair of driver mutations uncommonly seen as singlet mutations: one-third of doublets occur at five pairs of amino acids. Oncogene. 2008;27(31):4336-4343. doi: 10.1038/onc.2008.71 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Toffalini F, Demoulin JB. New insights into the mechanisms of hematopoietic cell transformation by activated receptor tyrosine kinases. Blood. 2010;116(14):2429-2437. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-04-279752 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

eMethods. Study Design

eTable 1. Called Variants Related to Patients and Samples

eTable 2. Clinical Characteristics of Patients Harboring a PDGFRB Mutation

eFigure. Novel PDGFRB Mutations in Myofibroma Lesions Induce Constitutive Activation of PDGFRB and are Sensitive to Imatinib