Abstract

Key points

Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy (HCM) is a genetic disease that causes thickening of the heart's ventricular walls and is a leading cause of sudden cardiac death.

HCM is caused by missense mutations in muscle proteins including myosin, but how these mutations alter muscle mechanical performance in largely unknown.

We investigated the disease mechanism for HCM myosin mutation R249Q by expressing it in the indirect flight muscle of Drosophila melanogaster and measuring alterations to muscle and flight performance.

Muscle mechanical analysis revealed R249Q decreased muscle power production due to slower muscle kinetics and decreased force production; force production was reduced because fewer mutant myosin cross‐bridges were bound simultaneously to actin.

This work does not support the commonly proposed hypothesis that myosin HCM mutations increase muscle contractility, or causes a gain in function; instead, it suggests that for some myosin HCM mutations, hypertrophy is a compensation for decreased contractility.

Abstract

Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy (HCM) is an inherited disease that causes thickening of the heart's ventricular walls. A generally accepted hypothesis for this phenotype is that myosin heavy chain HCM mutations increase muscle contractility. To test this hypothesis, we expressed an HCM myosin mutation, R249Q, in Drosophila indirect flight muscle (IFM) and assessed myofibril structure, skinned fibre mechanical properties, and flight ability. Mechanics experiments were performed on fibres dissected from 2‐h‐old adult flies, prior to degradation of IFM myofilament structure, which started at 2 days old and increased with age. Homozygous and heterozygous R249Q fibres showed decreased maximum power generation by 67% and 44%, respectively. Decreases in force and work and slower overall muscle kinetics caused homozygous fibres to produce less power. While heterozygous fibres showed no overall slowing of muscle kinetics, active force and work production dropped by 68% and 47%, respectively, which hindered power production. The muscle apparent rate constant 2πb decreased 33% for homozygous but increased for heterozygous fibres. The apparent rate constant 2πc was greater for homozygous fibres. This indicates that R249Q myosin is slowing attachment while speeding up detachment from actin, resulting in less time bound. Decreased IFM power output caused 43% and 33% decreases in Drosophila flight ability and 19% and 6% drops in wing beat frequency for homozygous and heterozygous flies, respectively. Overall, our results do not support the increased contractility hypothesis. Instead, our results suggest the ventricular hypertrophy for human R249Q mutation is a compensatory response to decreases in heart muscle power output.

Keywords: Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy, Myosin, Muscle physiology, Insect, Locomotion

Key points

Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy (HCM) is a genetic disease that causes thickening of the heart's ventricular walls and is a leading cause of sudden cardiac death.

HCM is caused by missense mutations in muscle proteins including myosin, but how these mutations alter muscle mechanical performance in largely unknown.

We investigated the disease mechanism for HCM myosin mutation R249Q by expressing it in the indirect flight muscle of Drosophila melanogaster and measuring alterations to muscle and flight performance.

Muscle mechanical analysis revealed R249Q decreased muscle power production due to slower muscle kinetics and decreased force production; force production was reduced because fewer mutant myosin cross‐bridges were bound simultaneously to actin.

This work does not support the commonly proposed hypothesis that myosin HCM mutations increase muscle contractility, or causes a gain in function; instead, it suggests that for some myosin HCM mutations, hypertrophy is a compensation for decreased contractility.

Introduction

Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy (HCM) is a genetically heritable disease that causes thickening of the heart's ventricular walls. It is one of the leading causes of sudden death in young adults, particularly in athletes, and affects about 1 in 500 individuals (Maron & Maron, 2013). It is associated with obstructed blood flow, cardiac arrhythmias and myofibrillar disarray, and typically arises from mutations in the genes of sarcomeric proteins. The mutation R403Q in myosin heavy chain (MHC) was the first identified mutation to cause HCM (Geisterfer‐Lowrance et al. 1990). Now, after nearly three decades, over 300 missense mutations in MHC alone have been shown to cause HCM (Buvoli et al. 2008). Patients show variable clinical phenotypes ranging from nearly asymptomatic to extremely life threatening conditions (Maron et al. 1995; Maron & Maron, 2013). Due to the large number of mutations known to cause HCM and to the variability of their phenotypes, an inclusive and detailed analysis of the disease is a challenge, and a complete understanding of HCM's molecular mechanisms is difficult.

A wide range of studies have attempted to elucidate the mechanisms by which myosin mutations cause HCM, with some studies showing conflicting results. Initially, scientists hypothesized that HCM mutations yielded improper filament assembly leading to myofibrillar disarray. This idea originated from observations that some missense mutations in myosin heavy chain disrupted sarcomeric assembly in Caenorhabditis elegans (Bejsovec & Anderson, 1988, 1990). However, when this hypothesis was tested with R403Q and R249Q HCM mutations, poor sarcomeric arrangement was not observed in rat cardiomyocytes (Becker et al. 1997). Subsequent studies of mutations R403Q, L908V, D239N and H251N showed increases in actin sliding velocity, ATPase activity and force generation (Palmiter et al. 2000; Adhikari et al. 2016). These results suggested that a gain in function, or hypercontractility, caused heart hypertrophy and myofibrillar disarray. Conversely, studies on the R403Q mutation in skinned fibres (Lankford et al. 1995) and optical trapping experiments (Nag et al. 2015) suggested decreased contractility, as supported by decreases in power output, maximum shortening velocity and single myosin force production. This decreased contractility led to the hypothesis that increased cardiac muscle mass is incorporated into the ventricles to compensate for the lower power and force production. Because of these diverse findings, it remains difficult to conclude whether HCM is a result of a gain or loss in myosin motor function (Davis et al. 2016).

Mutation R249Q was one of the earliest identified HCM mutations (Rosenzweig et al. 1991). Seven of the eight affected living adult relatives in this 1991 study showed the characteristic left‐ventricular hypertrophy. However, the genetically affected children in this study showed little to no evidence of hypertrophy, leading to the initial conclusion that this mutation was neither severe, nor caused early onset symptoms. Conversely, a second clinical study on a 10‐year‐old female expressing R249Q showed a severe phenotype, exhibiting chest pain and shortness of breath (Greber‐Platzer et al. 2001). Experimental studies of expressed cardiac β‐myosin characterized the R249Q mutation as having an intermediate effect on myosin motor function compared to other HCM mutants (R403G and R453C), with ∼50% decreases in Ca2+‐ATPase and actin translocation (Sata & Ikebe, 1996). A second set of R249Q‐myosin experiments also showed an approximate 40% decrease in the maximal velocity (V max) of ATPase, with an additional 1.85‐fold increase in the myosin K m for actin, suggesting reduced actin affinity (Roopnarine & Leinwand, 1998). Additional investigation into the mechanism of disease for R249Q would help resolve the debate on increased versus decreased contractility.

Experiments investigating the R249Q mutation would also help define structure‐function relationships within the myosin molecule. The R249 residue is located on the sixth strand of the central β‐sheet of myosin, a structure that has been proposed to influence the intramolecular communication between the actin and nucleotide binding sites (Coureux et al. 2004; Cecchini et al. 2008). Investigation of the R249Q mutation could provide insight into how the central β‐sheet influences myosin performance.

To examine the mechanism by which R249Q causes HCM, we generated Drosophila lines that transgenically express R249Q in the indirect flight muscles (IFMs). The extensively studied Drosophila genome streamlines mutation expression, especially for MHC where only one gene encodes all muscle MHC isoforms due to alternative exon splicing (George et al. 1989). Myofibrils in the IFMs are similar in structure to vertebrate muscle and generate power using similar cyclical lengthening and shortening contractions as the human heart. We found that the R249Q mutation yielded defective flight performance due to reduced maximum power and work generation in IFM fibres and lowered active force production. The mutation slowed cross‐bridge rates associated with actin attachment and the power stroke, but increased rates associated with detachment from actin. These results support the hypothesis that the R249Q HCM mutation causes decreased contractility rather than increased contractility.

Methods

DNA constructs

Site‐directed mutagenesis was used to introduce the R249Q mutation into the Drosophila P element‐containing Mhc transgene. Wild‐type genomic construct pwMhc2 (Swank et al. 2000) was digested with EagI to produce two subclones, pwMhc‐5ʹ and pMhc‐3ʹ. The pwMhc‐5ʹ subclone contained an 11.3 kb EagI Mhc fragment that was cloned into the pCasper vector, and the pMhc‐3ʹ subclone contained a 12.5 kb EagI Mhc fragment that was cloned into the pBluescriptKS EagI site (Stratagene, La Jolla, CA, USA). The pwMhc‐5ʹ subclone was further digested with XhoI and AvrII. A 6.8 kb XhoI‐AvrII‐digested fragment from pwMhc‐5ʹ was gel isolated and ligated into an XhoI‐AvrII site in the pLitmus 28I vector (New England Biolabs (NEB), Ipswich, MA, USA), to produce the pMhc‐5ʹ‐XA subclone, which was further digested with PstI and AvrII. The 4.3 kb PstI‐AvrII digested fragment from pwMhc‐5ʹ‐XA was then gel isolated and ligated into a PstI‐AvrII site in vector pLitmus 28I, to produce the pMhc‐5ʹ‐PA subclone. This was further digested with AgeI and BamHI, and the resulting 370 bp digested fragment was gel isolated and ligated into an AgeI‐BamH I site in the pLitmus 28I vector, to produce the pMhc‐5ʹ‐AB370 subclone. This subclone was subjected to site‐directed mutagenesis using the QuickChange II kit (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA, USA) and the exon specific‐primer 5ʹ‐TAAATTCATCCAGATCCACTTCG‐3ʹ containing the R249Q nucleotide mutation (underlined) to yield pR249Q‐5ʹAB370. Upon sequence confirmation of the R249Q site‐directed mutagenesis product, the pR249Q‐5ʹAB370 subclone was sequentially cloned back into the next intermediate subclone from which it originated. The resulting subclone, pwMhcR249Q‐5ʹ, was digested with EagI.

The 12.5‐kb pMhc‐3ʹ fragment was digested with EagI, gel isolated and ligated into the EagI site of the pwMhcR249Q‐5ʹ subclone, to yield pwMhcR249Q. The entire coding region and all ligation sites of the final pwMhcR249Q plasmid were confirmed by DNA sequencing (Eton Bioscience Inc., San Diego, CA, USA) before P element transformation.

P element transformation of Mhc genes

Transgenic Drosophila lines for pwMhcR249Q were generated by P element‐mediated transformation (Rubin & Spradling, 1982) by BestGene, Inc. (Chino Hills, CA, USA). Thirty‐three transgenic lines were obtained from 1200 injected embryos. The transgene location for each transgenic line was mapped to its chromosome location using balancer chromosomes and standard genetic crosses. Fourteen lines were mapped to the second chromosome, one line was mapped to the X chromosome, and 18 lines were mapped to the third chromosome. Transgenic lines mapped to the second chromosome were not examined because the endogenous myosin gene is located on that chromosome. Three independent transgenic lines mapped to the third chromosome (pwMhcR249Q‐12, pwMhcR249Q‐13, and pwMhcR249Q‐19) were crossed into the Mhc10 background, which is null for myosin heavy chain (MHC) in IFM and jump muscle (Collier et al. 1990), such that our R249Q myosin is the only myosin expressed in both of these muscles. Homozygotes for the R249Q transgene and Mhc10 were then crossed with wild‐type pwMhc2 lines (Swank et al. 2000) to produce heterozygotes (one copy of R249Q transgene and one copy of wild type) for transmission electron microscopy (TEM), flight testing and mechanical analysis (Swank, 2012).

Reverse‐transcription PCR

Reverse‐transcription PCR (RT‐PCR) was used to confirm that the Mhc transcripts from pwMhcR249Q homozygous transgenic lines were spliced correctly and contained the appropriate site‐directed nucleotide changes. The LiCl2 extraction method was used on upper thoraces of 2‐day‐old female flies to prepare RNA (Becker et al. 1992). The Protoscript cDNA synthesis kit (NEB) was used to generate cDNAs for each transgenic line using a reverse specific primer (5ʹ‐GTTCGTCACCCAGGGCCGTA‐3ʹ) to exon 8 and a forward specific primer (5ʹ‐TGGATCCCCGACGAGAAGGA‐3ʹ) to exon 2, which included the R249Q mutation. The resulting RT‐PCR products were sequenced by Eton Bioscience, Inc.

Myosin expression

To determine myosin expression levels relative to actin accumulation for each transgenic line, sodium dodecyl sulphate polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS‐PAGE) was used as previously described (O'Donnell et al. 1989). Briefly, five replicates of upper thoraces from six 2‐day‐old homozygous female flies were homogenized in 60 μl SDS gel buffer, and 6 μl of each homogenate was then loaded on a 9% polyacrylamide gel. Protein accumulation was determined using Coomassie Blue stained gels that were digitally scanned and analysed using NIH Image J software (https://imagej.nih.gov/ij/).

Light and transmission electron microscopy

Half‐thorax images were acquired from adult 2‐day‐old control, homozygous and heterozygous animals. Animals were cut in half in dissection solution (pCa 8.0, 5 mm MgATP, 1 mm free Mg2+, 0.25 mm phosphate, 5 mm EGTA, 20 mm N,N‐bis(2‐hydroxyethyl)‐2‐aminoethanesulfonic acid (BES, pH 7.0), 175 mm ionic strength, adjusted with sodium methane sulfonate, 1 mm DTT, 50% glycerol, and 0.5% Triton X‐100) under a Wild Heerbrugg M5A dissection microscope at 50× magnification with a Canon EOS Digital Rebel XTi camera.

Transmission electron microscopy was performed as previously described (O'Donnell & Bernstein, 1988) to determine the effects of transgene expression on muscle structure in homozygous and heterozygous backgrounds. Cross‐sections were obtained from females of R249Q transgenic lines 12, 13 and 19, and at least three different flies were examined per transgenic line.

Muscle mechanics

Newly eclosed female flies were collected every 30 min and allowed to mature for 2 h. Individual IFM fibres were isolated from the 2‐h‐old flies by microdissection as previously described (Swank, 2012). Briefly, flies were anaesthetized, the head and abdomen removed, thoraces split in half, and the IFM fibre bundle was extracted. The fibres were chemically skinned in dissection solution for 1 h at 6°C, separated from the bundle, and split in half. The fibres were fitted with a pair of aluminium foil t‐clips and mounted on a piezo motor and force transducer (Aurora Scientific) on our mechanics apparatus. The cross‐sectional area was measured to determine tension values. Passive (pCa 8.0) and total (pCa 5.0) isometric tension were recorded at the start of each experiment, and active tension was calculated by subtracting passive from total tension.

Optimal sarcomere length was found by stretching the fibre until it generated maximum power, as measured by sinusoidal analysis (described below). Small amplitude power, work, stiffness, and active isometric tension measurements were all measured at this optimal length. The acquisition frequency of the force and/or muscle length traces for these measurements was 8 kHz. A low acquisition frequency chart recorder also recorded the force trace and was used to continuously monitor the condition of the fibre during each experiment. The fibres underwent larger amplitude length changes to generate work loops, with oscillation amplitudes more similar to in vivo flight conditions (Josephson, 1985). Lastly, sinusoidal analysis was used to evaluate the effects of different ATP and inorganic phosphate (Pi) concentrations on fibre performance.

Sinusoidal analysis

Sinusoidal analysis was performed by oscillating IFM fibres with the piezo motor over 0.5 Hz to 650 Hz frequencies at 0.125% of the muscle length (ML) (Swank, 2012). Elastic and viscous moduli were calculated from amplitude and phase differences, plotted against each other, and fitted with the following equation adapted from Kawai & Brandt (1980):

| (1) |

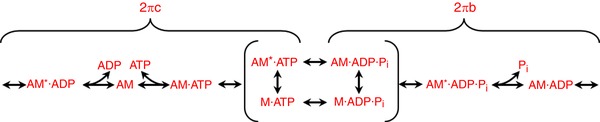

where A represents passive element stiffness, α is 1 Hz, f is frequency of muscle length oscillation, k is an exponent, i is the √−1, B and C are the amplitudes of work produced in work generating and work absorbing cross‐bridge steps, respectively, and b and c are the respective frequencies at which these amplitudes occur (Kawai & Brandt, 1980; Swank, 2012). Multiplying b and c by 2π gives apparent rate constants for the work producing and work absorbing cross‐bridge steps, which provide insight into cross‐bridge kinetic rates (Fig. 1). Total work was calculated as π(−E v)(ΔL/L)2, where E v is viscous modulus and ΔL/L is the sinusoidal length change of 0.125% divided by the length of the fibre. Power was calculated by multiplying total work by the frequency of oscillation.

Figure 1. Schematic representation of the cross‐bridge cycle depicting the steps that most influence 2πb and 2πc .

Sinusoidal analysis was used to generate muscle apparent rate constants for work generating (2πb) and work absorbing (2πc) steps of the cross‐bridge cycle. M, myosin; A, actin; Pi, inorganic phosphate. The asterisk indicates a second conformational state.

Work loop analysis

By performing work loop experiments on Drosophila IFM fibres, we are able to measure power production at longer muscle length (ML) oscillations than when using small amplitude sinusoidal analysis. The work loop length change amplitudes are more similar to ML changes Drosophila IFMs experience during in vivo flight. The fibres were subjected to a series of 10 identical ML changes (otherwise referred to as cycles) at a chosen amplitude between 0.25 and 1.25% ML and a frequency between 50 and 200 Hz. Power measurements from cycles 7 or 8 were analysed because the tension values have been shown to stabilize after cycle 6 (Ramanath et al. 2011). Different amplitudes and frequencies were tested until the optimal conditions for generating maximum power were found. After work loop experiments, the fibre was subjected to sinusoidal analysis to ensure that maximum power generation had not decreased by more than 10%, establishing that the fibre had not degraded.

Response to different ATP and Pi concentrations

The fibre's response to ATP was evaluated starting in a 20 mm ATP activating solution (pCa 5.0), which was decreased in a stepwise manner to 0.5 mm using partial exchanges with a 0 mm ATP activating solution. Sinusoidal analysis was performed at each concentration. A similar procedure was used to analyse Pi response, where [Pi] was increased from 0 mm to 16 mm starting with a 0 mm activating solution and partially exchanging with a 20 mm Pi activating solution. ATP data were fitted with a Michaelis‐Menten curve to calculate K m and V max values, and Pi data were fitted with a linear regression to compare how mechanical properties changed as [Pi] increased.

Locomotion assays

Free flight, wing beat frequency (WBF) and jump analyses were performed on 2‐day‐old heterozygous or homozygous females, at both 15 and 20°C. Free flight assays were performed by releasing flies into a Plexiglas flight arena where they were scored based on their flight pattern as outlined by Drummond et al. (1990). The WBF was measured (in Hz) by attaching a nylon tether to the fly thorax and holding it in front of an optical tachometer for 20 s (Tohtong et al. 1995). Each fly was tested three times and values were averaged. Jump assays consisted of removing the wings from the fly and inducing a jump with a paintbrush or pencil tip. Jump distance was marked, measured (in cm) and averaged. Each fly was tested eight times.

Protein structure modelling

The human β‐cardiac myosin crystal structure (PDB 4P7H) was used as a template to analyse the predicted protein structure of the R249Q mutant (Winkelmann et al. 2011). Wild‐type indirect flight isoform (IFI) and R249Q myosin S1 amino acid sequences were modelled onto the human β‐cardiac myosin backbone using the SWISS‐MODEL homology modelling server (http://swissmodel.expasy.org/; Arnold et al. 2006). Structures were viewed using the PyMOL Molecular Graphics System v. 1.8 (Schrödinger, LLC).

Statistical analyses

Data from control, homozygous and heterozygous lines are reported as means ± SEM and were compared using one‐way ANOVA with Holm‐Sidak pairwise multiple comparisons in Sigma Plot (v11.0), with the exception of the comparison between work generated and work absorbed values for each genotype in Table 3, where a Student's paired t test in Excel was used. Statistical significance was set at P<0.05. All n values are reported in the tables and figures.

Table 3.

Work loop experiments

| %ML amp. | f Pmax (Hz) | Power (W/m3) | Net‐work (J/m3) | Work gen. (J/m3) | Work abs. (J/m3) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control | 0.79 ± 0.06 | 115 ± 8.40 | 240 ± 34.4 | 2.18 ± 0.30 | 36.2 ± 4.19 | −34.0 ± 3.95 |

| R249Q/R249Q | 0.48 ± 0.04* | 100 ± 6.15 | 57.8 ± 9.09* | 0.54 ± 0.10* | 21.0 ± 2.40* , # | −20.5 ± 2.30* |

| R249Q/+ | 0.50 ± 0.00* | 142 ± 3.56* , + | 90.3 ± 9.69* | 0.60 ± 0.07* | 16.9 ± 1.39* , # | −16.2 ± 1.33* |

| Control | — | — | 221 ± 35.6 | 1.74 ± 0.29 | 32.9 ± 3.12 | −31.2 ± 2.91 |

| R249Q/R249Q | — | — | 26.2 ± 10.6* | 0.18 ± 0.08* | 36.2 ± 2.14 | −36.0 ± 2.09 |

| R249Q/+ | — | — | 34.5 ± 16.8* | 0.18 ± 0.14* | 26.1 ± 2.12 | −26.0 ± 2.06 |

Top three rows: the average measurements from work loop experiments where maximum power was optimized for each fibre. %ML amp. and frequency of muscle oscillation are adjusted to reach optimal power generation. Bottom three rows: the average work and power measurements of the fibres performing at the control's optimal power generating conditions; 0.75% ML amplitude and 125 Hz. *Significant difference from the control; +significant difference between homozygous and heterozygous lines (one‐way ANOVA; P < 0.05). #Significant difference between work generated and work absorbed values (paired t test, P < 0.05). n = 12 for all groups, except homozygous fibres under control conditions (second‐to‐last row), where n = 5. The data set of individual fibre values used to calculate these averages, SEMs and P values can be found in the fourth tab of Supplemental File S1 in Supporting Information.

Results

Production and verification of R249Q transgenic lines

Thirty‐three R249Q transgenic lines of Drosophila were produced by P element‐mediated germline transformation. Three third chromosome lines, pwMhcR249Q‐12, ‐13, and ‐19 were assessed for Mhc gene and protein expression. The RT‐PCR performed on the RNAs extracted from the upper thoraces of 2‐day‐old adult female flies showed that each line produced the predicted 1.3‐kb cDNA encompassing exon 2 through exon 8. We verified that alternative exons 3b and 7d were spliced correctly and confirmed the nucleotide base change from CGT to CAG encoded by the R249Q DNA construct. Proteins extracted from the upper thoraces of 2‐day‐old adult female flies showed that the ratio of MHC to actin levels was statistically equal to wild‐type levels and between each transgenic line (Table 1). Two homozygous transgenic lines, abbreviated as R249Q‐19 and R249Q‐12, were tested for similar changes in phenotype using flight assays and sinusoidal analysis. No differences were found between the two lines, meaning the insertion site of the gene did not affect the phenotype (Tables 2 and 4). All analyses on IFM mechanics were performed using R249Q‐19.

Table 1.

Transgenic lines, chromosome locations, and myosin expression levels

| Transgenic line name | Chromosome location | Protein accumulation |

|---|---|---|

| pwMhc2 | X | 1.00 ± 0.04 |

| pwMhcR249Q‐12 | 3 | 0.97 ± 0.04 |

| pwMhcR249Q‐13 | 3 | 0.96 ± 0.06 |

| pwMhcR249Q‐19 | 3 | 0.96 ± 0.06 |

Protein expression levels of R249Q transgenic lines were compared to pwMhc2 (control) and none were statistically different (one‐way ANOVA, P < 0.05). Protein amounts are means ± standard error of the mean (SEM).

Table 2.

Sinusoidal analysis

| Power (W/m3) | f max (Hz) | −E v (kN/m2) | E e (kN/m2) at max. power | E e (kN/m2) at 650 Hz | fE e (Hz) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control | 100 ± 11 | 151 ± 2.9 | 146 ± 15 | 326 ± 22.5 | 389 ± 26.5 | 248 ± 4.82 |

| R249Q/R249Q line 19 | 33 ± 4.7* | 121 ± 3.8* | 63 ± 8.2* | 323 ± 19.8 | 318 ± 21.4 | 250 ± 17.3 |

| R249Q/R249Q line 12 | 24 ± 2.3* | 111 ± 3.2* | 44 ± 4.8* | 346 ± 35.2 | 418 ± 43.3# | 229 ± 5.30* |

| R249Q/+ | 55 ± 6.1* | 155 ± 2.9+ | 78 ± 8.9* | 301 ± 22.7 | 297 ± 23.2* | 271 ± 8.21+ |

Numbers are the average of values derived from the sinusoidal experimental run that generated maximum power for each fibre (± SEM). The only exceptions are the dip frequency (fE e), which represents the frequency where the elastic modulus (E e) is lowest, and the E e at 650 Hz. −E v is viscous modulus. f max is the oscillation frequency where maximum power (Power) was generated. *Significant difference from the control; +significant difference between homozygous line 19 and heterozygous lines; #significant difference between R249Q/R249Q line 12 and R249Q/R249Q line 19 (one‐way ANOVA; P < 0.05). n = 12 for control, R249Q/R249Q line 19, and R249Q/+ fibres. n = 8 for R249Q/R249Q line 12. The data set of individual fibre values used to calculate these values can be found in the third tab of Supplemental File S1 in Supporting Information.

Table 4.

Kinetic rate constants

| A | B | C | 2πb (s−1) | 2πc (s−1) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control | 339 ± 23 | 741 ± 73 | 923 ± 76 | 1036 ± 34.8 | 5376 ± 168 |

| R249Q/R249Q line 19 | 277 ± 18 | 312 ± 31* | 945 ± 164 | 690 ± 23.3* | 21272 ± 5034* |

| R249Q/R249Q line 12 | 280 ± 25 | 272 ± 26* | 664 ± 52* | 697 ± 26.2* | 14378 ± 2362* |

| R249Q/+ | 234 ± 19* | 504 ± 54* , + | 696 ± 34 | 1123 ± 31.6* , + | 7775 ± 525+ |

A, B, C, b, and c are derived from eqn (1), and are the average of the values (± SEM) taken from the sinusoid experimental run that generated maximum power for each fibre. 2πb and 2πc are muscle apparent rate constants for work generating and work absorbing steps of the cross‐bridge cycle, respectively (see Fig. 1). *Significant difference from the control; +significant difference between R249Q/R249Q line 19 homozygous, and heterozygous lines; #significant difference between R249Q/R249Q line 12 and R249Q/R249Q line 19 (one‐way ANOVA; P < 0.05). n = 12 for control, R249Q/R249Q line 19, and R249Q/+ fibres. n = 8 for R249Q/R249Q line 12. The data set of individual fibre values used to calculate these average kinetic rate constants can be found in the fifth tab of Supplemental File S1 in Supporting Information.

Muscle ultrastructure

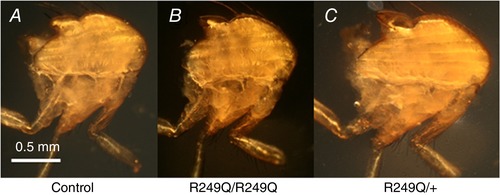

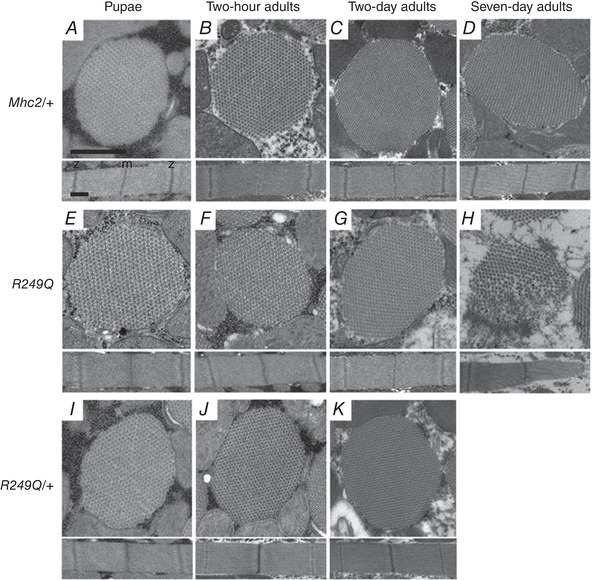

The dorsal longitudinal muscles (DLMs) are one of two sets of IFMs that power insect flight. They horizontally span the upper half of the thorax. DLMs appear normal in the R249Q homozygous and heterozygous animals 2 days post eclosion (Fig. 2). All 6 fibres spanned the full thorax from anterior to posterior and show no hypercontraction or other irregular shape. To study muscle structure at a higher resolution, we performed transmission electron microscopy on IFM fibres. The ultrastructure of Mhc/+ control fibres resembled that of wild type throughout development, as myofibril morphology remained oval shaped and the normal thick and thin filament assembly formed a double hexagonal array in transverse sections; sarcomeres displayed well‐formed M‐ and Z‐lines in longitudinal sections (Fig. 3 A–D). Homozygous R249Q fibres appeared essentially identical to the control at the late stage pupal and 2‐h‐old stages (Fig. 3 E and F). However, homozygous R249Q hexagonal packing around the fibre edges showed minor degradation at 2‐days‐old (Fig. 3 G) and by 7‐days‐old, fibres were severely disrupted (Fig. 3 H). Our analysis of transverse and longitudinal sections from R249Q heterozygotes at three stages showed normal assembly of thick and thin filaments and maintenance of fibril morphology, resembling that of the control (Fig. 3 I–K). Because myofibril integrity was maintained in homozygous and heterozygous fibres at 2 h old, fibre dissections for mechanical experiments were performed on flies of this age. Using fibres from younger flies helps decrease the possibility that mechanical changes observed are a result of possible myofibril degradation.

Figure 2. Images of dorsal longitudinal IFMs in fly thoraces.

Two days post eclosion, control (A), homozygous (B) and heterozygous (C) flies were cut in half longitudinally. The anterior end of the fly is facing the right of the figure and the 6 DLM fibres run anterior to posterior. The mutant fibres appear indistinguishable from control fibres. There is no evidence of hypercontraction or irregular shape in any of the DLM fibres.

Figure 3. Transmission electron micrographs of R249Q IFM cross‐sections (top) and longitudinal sections (bottom).

Four different stages of development were analysed: late stage pupae, 2‐h‐old adults, 2‐day‐old adults, and 7‐day‐old adults. Mhc2/+ controls at all ages show that thick and thin filaments are arranged in a normal double‐hexagonal pattern and that myofibril morphology remains intact (A–D). We have shown previously that pwMhc2 and wild‐type fibres show no differences in myofibril and sarcomere formation (Swank et al. 2000). Sarcomere structure with regularly spaced M‐ and Z‐lines are evident at all stages. Homozygous R249Q late stage pupae and 2‐h‐old adults are essentially identical to Mhc2/+ (E and F). Homozygous R249Q fibres begin to experience a very small amount of disruption in fibril morphology and hexagonal packing at the edges of the myofibril at 2 days old (G), but disruption is evident at 7 days old (H). Heterozygous R249Q late stage pupae, 2‐h‐old adults, and 2‐day‐old adults are essentially identical to Mhc2/+ (I–K). Myofibrils shown in each panel are representative of the entire population at that given stage of development. Scale bars, 0.5 μm. M line and Z disk are labelled as ‘m’ and ‘z’, respectively, in panel A.

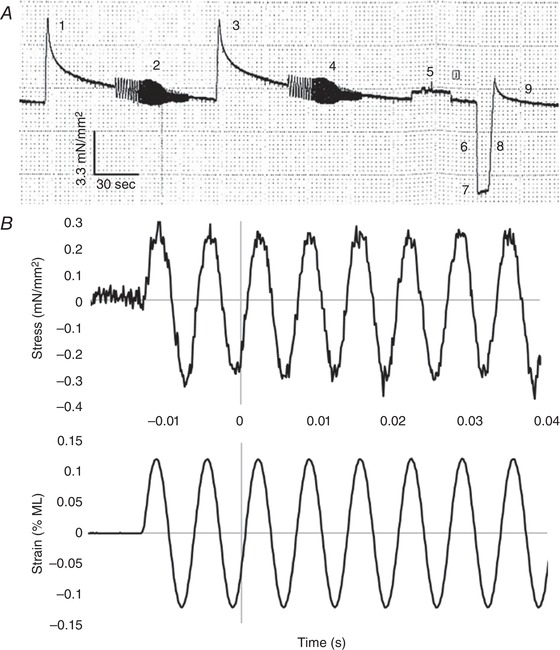

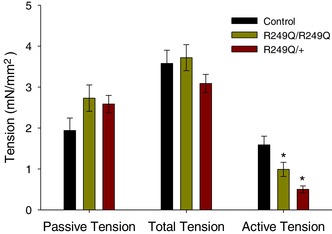

R249Q lowers active tension

Based on the increased contractility HCM hypothesis, we expected increased tension generation by fibres expressing the R249Q mutation. However, our mechanical measurements of homozygous and heterozygous fibres showed either no change or a decrease in tension values compared to control fibres. Example tension traces for each fibre type and how isometric tension is measured (labelled 6–9) are shown in Fig. 4 A. Passive isometric tension values (pCa 8.0) between the control and mutant IFM fibres were not statistically different (1.99 ± 0.29, 2.73 ± 0.32 and 2.59 ± 0.21 for control, homozygous and heterozygous, respectively). Once activated with calcium (pCa 5.0), the total amount of isometric tension was also not statistically different between fibres (3.58 ± 0.32, 3.72 ± 0.32 and 3.09 ± 0.22 for control, homozygous and heterozygous fibres, respectively). However, when active tension was calculated (total – passive), homozygous and heterozygous fibres generated 38% and 68% less tension than control fibres, respectively (1.59 ± 0.21, 0.99 ± 0.17 and 0.50 ± 0.08 for control, homozygous and heterozygous fibres, respectively) (Fig. 5).

Figure 4. Representative stress and strain traces.

A, an example low time resolution tension trace from a control fibre is shown. Numbers 1–9 indicate events during the experiment. The first portion of the trace shows how we determined optimal fibre length. Because it is not possible to measure IFM sarcomere length, we instead stretch the fibre in increments of 2% of its muscle length (labelled 1 and 3) and run a sinusoidal analysis at each length (labelled 2 and 4) until the power does not increase by more than 3%. The final sinusoid run is performed at the optimal length. This length is used for the remainder of the experiment. The perturbation at 5 is due to removing the cover over the mounted fibre to visually check fibre integrity. At 6 we are shortening the muscle to slack length to determine 0 tension (baseline) (labelled 7). Label 8 is where we return the fibre to its optimal length. Label 9 is gradual tension recovery. We allow the fibre to recover for 2 min before measuring active isometric tension. B, example high time resolution traces (8 kHz) of a portion of our sinusoidal analysis perturbations (2 and 4 in A). Recorded stress (top) and strain (bottom) traces for control fibres are shown for a 0.125% ML change sinusoidal perturbation at 150 Hz. Note that the first couple of cycles are not included in the analysis (to allow the response to achieve a steady state) and this is why 0 s is not at the start of the trace. A total of 77 cycles were run at this frequency. The average amplitude and phase of the stress response relative to the strain is used to calculate elastic and viscous moduli, as well as work and power.

Figure 5. Isometric tension generation.

Passive and total tension show no significant differences between R249Q and control fibres, but R249Q fibres produce lower active tension (Active = Total − Passive). Bars are means ± SEM. n = 12 for each fibre type. *Statistically significant difference from control fibres (one‐way ANOVA; P < 0.05). The full data set used to create this figure can be found in the first tab of Supplemental File S1 in Supporting Information.

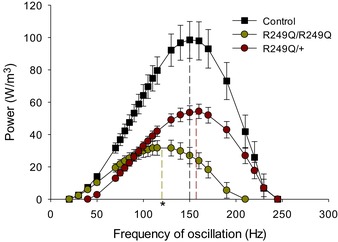

R249Q decreases power and work production

The primary function of heart muscle is to cyclically generate power to pump blood throughout the body. Similarly, IFMs cyclically contract to power wing beating. We found R249Q impaired IFM power production. Maximum small amplitude sinusoidal power production was reduced 67% and 45% in homozygous and heterozygous fibres, respectively, compared to control fibres (Table 2, Figs 4 B and 6). Considering the frequencies where positive power was produced, homozygous fibres produced the same amount of power as the control from 30 to 70 Hz, but generated lower power at higher frequencies. Conversely, heterozygous fibres produced lower power than the control starting at 50 Hz, and power output remained lower until 210–250 Hz, when power values of heterozygous and control fibres were the same. This suggested that the heterozygous fibres performed better than homozygous fibres at higher frequencies.

Figure 6. Skinned fibre power output versus frequency of muscle length oscillation.

Maximum power output and the frequency at which maximum power is generated (f max, vertical dashed lines) were measured by sinusoidal analysis of control, R249Q homozygous (R249Q/R249Q), and heterozygous (R249Q/+) IFM fibres. Both mutant fibre types show significantly decreased maximum power production, and homozygous fibres have a lower f max (*, one‐way ANOVA: P < 0.05). n = 12 for each fibre type. The full data set used to create this figure can be found in the second tab of Supplemental File S1 in Supporting Information. Additionally, an example stress trace of a control fibre during sinusoidal analysis (150 Hz) can be found in Fig. 4 B.

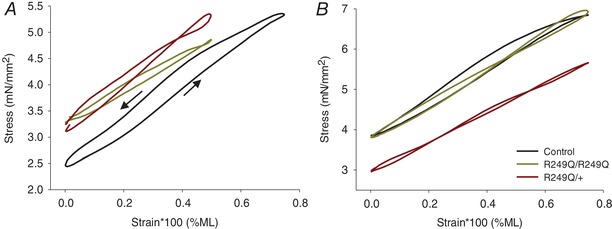

Large amplitude work loop experiments revealed the optimal muscle length change amplitude and oscillation frequency parameters that produced maximum power for each fibre. Overall, both homozygous and heterozygous mutant fibres performed optimally at muscle length oscillations lower than control fibres. However, homozygous fibres generated maximum power at slower oscillation frequencies, while heterozygous fibres performed optimally at faster frequencies (Table 3). Even under these optimized parameters, homozygous and heterozygous fibres still produced, respectively, 76% and 63% less power than the control fibres (Table 3). Net‐work production decreased in these work loop experiments, by 79% and 72% in homozygous and heterozygous fibres, respectively, as determined by measuring the reduced area within the traces for R249Q fibres (Fig. 7 A). Both the work generating and work absorbing portions of the work loop were decreased; 42% and 40% lower for homozygotes, and 53% and 52% for heterozygotes compared to control fibres, respectively (Table 3). Although both work generated and work absorbed decreased, a greater decrease in the amount of work generated occurred, resulting in decreased net‐work production.

Figure 7. Work loop traces for R249Q mutants and control lines.

The area inside the traces is the amount of work generated, which is significantly smaller for mutant fibres (one‐way ANOVA; P < 0.05). A, traces from representative fibres when the generation of maximum power was optimized by varying percentage muscle length (%ML) and ML oscillation frequency. B, representative traces from work loop runs conducted using identical %ML and oscillation frequency values. These values correspond to those where control fibres generated maximum power: 0.75% ML and 125 Hz. Arrows in panel A indicate the counterclockwise direction of the work loop trace for the control. All other traces also run counterclockwise, indicating positive work production.

We also analysed R249Q fibres using the parameters under which control fibres most frequently generated maximum power, at 0.75% ML at 125 Hz (Fig. 7 B). Under these parameters they performed worse than during their smaller, optimal 0.5% ML oscillation work loops, as homozygous and heterozygous fibres’ work and power decreased by ∼90% from the control (Table 3). Therefore, the increased stretch amplitude required for control fibre optimal performance had a major negative impact on R249Q work and power generation.

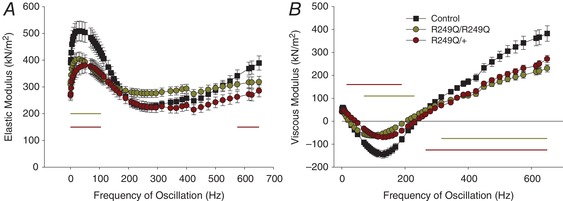

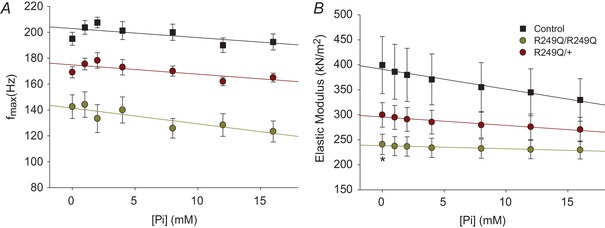

Alterations to elastic and viscous properties

We found that the R249Q mutation altered both instantaneous muscle stiffness (elastic modulus) characteristics and viscous stiffness (viscous modulus) characteristics. Active muscle stiffness, at the frequency where maximum small amplitude power was generated, was not statistically different between homozygous and heterozygous mutant fibres, nor between mutant and control fibres (Table 2). However, at frequencies ≤105 Hz, homozygous fibres decreased elastic modulus, while heterozygous fibres decreased elastic modulus at ≤105 Hz and ≥575 Hz (Fig. 8 A) relative to the control. Viscous modulus (E v) was less negative for both mutant fibres at low frequencies, indicating a decrease in work generation (Fig. 8 B). Significantly lower –E v values were observed at frequencies ≥315 Hz and ≥265 Hz for homozygous and heterozygous fibres, respectively, suggesting less work absorption at higher frequencies for R249Q mutant fibres.

Figure 8. Elastic and viscous modulus versus muscle length oscillation frequency.

A, both mutant fibre types show lower elastic modulus (stiffness) values at frequencies indicated by the horizontal lines (one‐way ANOVA; P < 0.05). B, the smaller negative viscous modulus values of the R249Q mutants indicate these fibres produce less work. Horizontal lines show where the viscous modulus is significantly different from the control (one‐way ANOVA; P < 0.05). n = 12 for each fibre type.

R249Q alters cross‐bridge kinetics

The value of the maximum frequency of muscle length oscillation, f max, provides insight into overall IFM kinetics. In homozygous mutant fibres, f max was slowed by 20% compared to the control value and heterozygous f max was not different from that of control fibres. Furthermore, the frequency where maximum power was produced in work loop experiments (f Pmax) for homozygous fibres was 100 Hz, while that of control fibres was 115 Hz, which was not statistically different. However, heterozygous f Pmax at 140 Hz, was significantly higher than that of control fibres.

Breaking the kinetics down into work generating and work absorbing steps of the cross‐bridge cycle, the homozygous mutant fibres showed a 33% decrease in the 2πb value and a dramatic three‐fold increase in the 2πc value (Table 4). The slower 2πb rate suggests slower transitions through work producing steps of the cross‐bridge cycle (attachment and Pi release), while the faster 2πc rate suggests faster transitions through the work absorbing steps (ADP release and ATP binding and detachment) of the cycle (Fig. 1) (Kawai & Brandt, 1980; Swank et al. 2006). For heterozygous fibres, we observed a statistically significant increase in 2πb compared to control fibres, but even though 2πc increased by 45%, it was not statistically significant at P < 0.05 (one‐way ANOVA) (Table 4). While 2πb is similar in value to f max, they are not reflective of an identical molecular mechanism. 2πb is primarily influenced by work generating steps of the cross‐bridge cycle, such as Pi release and the power‐stroke, which are also major influencers on f max, resulting in similarity between 2πb and f max. However, f max, is also significantly influenced by additional steps of the cycle that have little to no influence on 2πb.

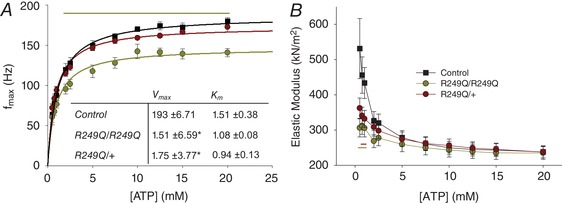

A decrease in the number of actin bound R249Q myosins is supported by its response to ATP and Pi

f max values were plotted against [ATP] and fitted with the Michaelis‐Menten equation (Fig. 9 A). Whereas V max was significantly lower for both homozygous and heterozygous mutant fibres than for control fibres, there were no significant differences in K m values among the three groups (Fig. 9 A, inset). However, there was a trend towards higher ATP affinity, as suggested by slightly lower K m values for the R249Q fibres. Higher ATP affinity was supported by significantly lower stiffness values (elastic modulus) in the mutant fibres at low ATP concentrations (Fig. 9 B). The control stiffness values behaved as expected, displaying an exponential increase as the fibres approached the rigor state, but the homozygote and heterozygote mutants only showed modest increases in stiffness with decreasing ATP concentration.

Figure 9. Fibres’ response to changing ATP concentrations.

The experiment was conducted starting with 20 mm ATP and decreasing to 0.5 mm. A, f max values plotted over changing [ATP], and fitted with the Michaelis‐Menten equation. The table inset lists the mean and SEM for Michaelis‐Menten parameters K m and V max. *Significant difference from the control. The yellow horizontal line indicates at which concentrations homozygous f max is significantly lower (one‐way ANOVA; P < 0.05). n = 12 for control, n = 11 for heterozygous, and n = 10 for homozygous fibres. B, elastic modulus values plotted against [ATP]. Yellow and red horizontal lines show where homozygous and heterozygous fibres differ significantly (one‐way ANOVA; P < 0.05) in stiffness from the control. n = 12 for control fibres and n = 11 for homozygous and heterozygous fibres.

The R249Q fibres displayed a lower f max at all [Pi], but the change in f max as [Pi] increased was not different between mutant and control fibres, nor between homozygous and heterozygous fibres (Fig. 10 A). This showed that R249Q f max was not differentially affected by increasing Pi compared to the control, indicating that Pi release remains the rate limiting step of the cross‐bridge cycle (Swank et al. 2006). The R249Q stiffness values at 100 Hz decreased less than the control as [Pi] increased, as shown by less negative regression slopes (Fig. 10 B).

Figure 10. Fibres’ response to changing inorganic phosphate [Pi] concentrations.

All plots are fitted with a linear regression. A, f max values for each of the three fibre types plotted over changing [Pi]. All homozygous and heterozygous f max values are statistically lower than the control (one‐way ANOVA; P < 0.05). n = 8, 6 and 11 for control, homozygous, and heterozygous fibres, respectively. B, stiffness values as [Pi] increases at 100 Hz. *Significant difference from the control (one‐way ANOVA; P < 0.05) at 0 mm Pi. n = 9, 6 and 11 for control, homozygous and heterozygous fibres, respectively.

Low power impedes flight ability

Flight capability was determined at the temperature used for mechanical experiments (15°C) as well as ambient temperature (20°C). Free flight ability and WBF of the homozygous flies, at both 15 and 20°C, decreased about 50% and 19%, respectively, compared to control flies (Table 5, columns 1–4). Heterozygous flies displayed 33% and 15% decreases in flight index at 15 and 20°C, respectively. WBF in the heterozygous flies showed small, but significant decreases of 6% and 5%, at 15 and 20°C, respectively. The distance homozygous flies jumped was about 30% less than control flies, but heterozygous flies did not differ in jump distance from the controls (Table 5, columns 5 and 6).

Table 5.

Locomotion assays

| Flight index | WBF (Hz) | Jump ability (cm) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 15°C | 20°C | 15°C | 20°C | 15°C | 20°C | |

| Control | 2.29 ± 0.12 | 4.14 ± 0.16 | 155 ± 1.81 | 197 ± 2.08 | 1.70 ± 0.10 | 1.84 ± 0.09 |

| R249Q/R249Q | 1.30 ± 0.11* | 1.78 ± 0.11* | 126 ± 3.78* | 158 ± 1.82* | 1.14 ± 0.08* | 1.44 ± 0.09* |

| R249Q/+ | 1.53 ± 0.11* | 3.50 ± 0.17* , + | 146 ± 2.33* , + | 188 ± 4.07* , + | 1.60 ± 0.06+ | 1.89 ± 0.09+ |

*Significant difference from the control; +significant difference between homozygous and heterozygous lines (one‐way ANOVA; P < 0.05). n = 111 for free flight, n = 10 for wing beat frequency (WBF), and n = 10 for jump tests, except for homozygous R249Q flies’ WBF at 15°C (n = 3) and at 20°C (n = 5) because homozygous flies had difficulty beating their wings for 20 consecutive seconds, which often caused unreliable WBF measurement.

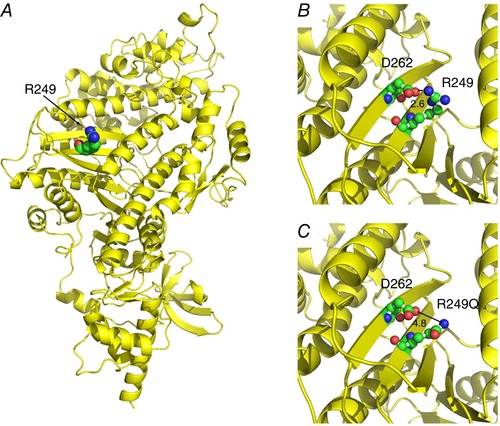

Modelling myosin R249

Molecular modelling was used to determine the location and potential interactions of the amino acid residue corresponding to human HCM mutation R249Q. The human β‐cardiac myosin motor domain (PDB 4P7H) was used as the template on which we modelled the Drosophila IFM myosin heavy chain sequence (Fig. 11). The R249 residue is conserved in human and Drosophila myosins, and it is located on the sixth strand of the seven stranded β‐sheet, which forms part of the transducer region (Coureux et al. 2004) (Fig. 11 A). The positively charged R249 residue possibly interacts with a negatively charged residue D262, located on the seventh strand of the β‐sheet (Fig. 11 B), with a 2.6 Å contact distance. The loss of charge due to the R249Q mutation disrupts this potential interaction, increasing the D262 contact distance to 4.8 Å (Fig. 11 C).

Figure 11. Location of R249 on the myosin molecule.

A, R249 is conserved in human and Drosophila myosins. The human β‐cardiac myosin motor domain (PDB 4P7H) was used as a template to model the Drosophila indirect flight muscle myosin heavy chain sequence in order to analyse the R249 residue involved in HCM (displayed as spheres). R249 is on the sixth strand of the central β‐sheet. B, the positively charged R249 residue potentially interacts with a negatively charged residue D262 (located on the seventh strand of the β‐sheet) with a 2.6 Å contact distance. C, the HCM mutation R249Q disrupts the charged interaction with D262, with an increase in contact distance to 4.8 Å.

Discussion

We found that the R249Q HCM myosin mutation expressed in Drosophila IFM allowed normal myofibril assembly but caused decreases in force, work, power generation and active muscle stiffness. These findings contradict the increased contractility hypothesis for HCM being caused by myosin heavy chain mutations (Palmer et al. 2004; Alpert et al. 2005; Kirschner et al. 2005; Debold et al. 2007; Kronert et al. 2018; Trivedi et al. 2018). The decrease in maximum power production for flies expressing both homozygous and heterozygous R249Q mutations is the best evidence that this HCM mutation decreases muscle contractile performance. This was evident at the full organism level as we observed decreased flight performance (Table 5), which relies heavily on IFM power production. Power production by IFM is influenced by two factors: net‐work production and f max. Both small amplitude sinusoidal analysis and large amplitude work loop experiments showed lower net‐work generation, which was due to decreased work generation rather than increased work absorption (Table 3 and Fig. 8). Lower work generation suggests decreased muscle force production, as supported by decreased active isometric tension (Fig. 5). The f max value was also reduced and along with contributing to lower power production, suggested a net slowing of cross‐bridge cycling. Therefore, both slower muscle speed and lower work generation were responsible for R249Q fibres’ decreased power production.

R249Q myosin mechanisms

Although lower f max suggests a net slowing of cross‐bridge cycling, our data indicate that the R249Q mutation alters at least two rate constants of the cross‐bridge cycle; one is increased and the other decreased. The decreased muscle apparent rate constant 2πb in homozygous fibres suggests a slowing of myosin attachment and/or steps associated with the power stroke steps. This decrease is also supported by reduced and slower work production (Table 3). In contrast, 2πc values increased, suggesting that the mutation increases ADP release, ATP binding, and/or myosin detachment rates (Fig. 1) (Kawai & Brandt, 1980; Swank et al. 2006). This increase was supported by very low elastic modulus values near rigor conditions and by the trends towards a higher myosin affinity for ATP (Fig. 9). If the R249Q mutation slows the rates of the steps associated with myosin attachment, and increases the rates contributing to myosin detachment, there should be a reduction in the time that an individual myosin head spends attached to actin, and therefore a net decrease in the total number of cross‐bridges bound at any given time. This would result in decreased muscle stiffness and lower active isometric tension, both of which we observed in the present study (Figs 5 and 8). An alternative or additional explanation is that each myosin head is producing less force. We cannot rule this out because we did not measure myosin unitary force production, but the internal location of the R249Q within the catalytic domain seems an unlikely location to alter myosin head stiffness or step size.

Heterozygous fibre properties

In HCM patients, the causative mutation is typically expressed in a heterozygous state, so we evaluated the results from heterozygous R249Q Drosophila IFM fibres. In both small amplitude power measurements and work loop experiments, heterozygous fibres produced less power than control fibres, and statistically similar maximum power production as homozygous fibres. However, muscle kinetics in the heterozygous fibres were the same or only slightly different from control fibres, while homozygous fibre kinetics were much slower than control fibre kinetics. For example, heterozygous f max values were not different from control values, while homozygous f max values were much slower than control fibre values. This was also true at the level of myosin kinetics, but more apparent for steps associated with actin attachment than detachment. Indicators of myosin and actin attachment rate, e.g. 2πb, were not different or slightly faster than control values, while homozygous values were much slower than control values. In contrast, indicators of myosin detachment rate, e.g. ATP affinity and stiffness at low [ATP] (Fig. 9), suggested faster detachment rates for both heterozygous and homozygous fibres than control fibres. Thus, it appears that the presence of wild‐type myosin can significantly compensate for the mutation's deteriorative slowing of steps associated with myosin attachment to actin in heterozygous fibres, but can only partially mitigate the mutant's faster detachment kinetics. This interpretation is supported by previous work suggesting that faster myosin heads dominate actin attachment kinetics, while slower myosins dominate actin detachment kinetics (Cuda et al. 1997). The faster heterozygous detachment kinetics will still result in fewer myosin heads bound at any given time and hence explain why the heterozygous fibres produce less force and work. Thus, for the heterozygotes, we observed a decrease in muscle performance and lower net‐work and power production, which supports the decreased contractility hypothesis.

Molecular modelling

The R249Q mutation results in increased contact distances between the sixth and seventh strands of the central β‐sheet, which probably alters the normal sheet distortion required to move through chemo‐mechanical transduction. There is strong evidence in the myosin V structure that the central β‐sheet is responsible for coordinating the transition from the rigor‐like to near‐rigor states and that it “forms the structural basis for communication between the actin interface and nucleotide binding pocket” (Coureux et al. 2003, 2004). In fact, the importance of the interaction between the two β‐sheets containing R249 and D262 (Fig. 11) is reinforced by the presence of the analogous interaction in myosin V, except that the charges of the residues are reversed. Therefore, poor structural communication between the nucleotide and actin binding sites could result in the observed changes in myosin kinetics and force production.

Comparisons to other studies

Our results agree with findings from the first functional analysis of R249Q‐expressed myosin (Sata & Ikebe, 1996). This study showed approximately 50% decreases in Ca2+‐ATPase, V max of actin‐activated ATPase, and actin translocation velocity. These ATPase assays and our decreased f max results both support the conclusion that the R249Q mutation results in a slowing of overall myosin kinetics. Roopnarine & Leinwand (1998) also showed that the R249Q mutation had a larger K m value in actin activated ATPase experiments, which suggested decreased actin affinity. This falls in line with our results, as R249Q myosin appears to dissociate from actin more readily as shown by increased 2πc and increased ATP affinity, and by our lower 2πb values, which could be due to a lower affinity of myosin for actin. Overall, these past studies and our current results, which include the first fibre mechanical analyses on R249Q MHC, suggest R249Q causes decreased contractility. There has also been evidence of HCM mutations in other sarcomeric proteins, such as troponin, tropomyosin and the myosin light chains, decreasing contractility. Frequently, these mutations result in decreases in maximum force production and stiffness in skinned and intact muscles, which mirrors the results presented here (Hernandez et al. 2005; Kerrick et al. 2009; Bai et al. 2011, 2014, 2015; Kazmierczak et al. 2013).

However, our current results conflict with the increased contractility hypothesis for HCM mutations. Much of the evidence for increased contractility comes from single molecule studies on other MHC HCM mutations, which showed increases in ATPase rates, actin sliding velocity, and/or increases in power generation calculated from force‐velocity measurements (Palmiter et al. 2000; Tyska et al. 2000; Yamashita et al. 2000; Keller et al. 2004; Palmer et al. 2004, 2008; Alpert et al. 2005; Debold et al. 2007; Belus et al. 2008). Skinned fibre studies on MHC HCM mutations have also shown increases in unloaded shortening velocity, force generation, and/or calcium sensitivity (Blanchard et al. 1999; Köhler et al. 2002; Kirschner et al. 2005; Seebohm et al. 2009). In agreement with these observations, we have previously found, using our Drosophila model, that the HCM mutation R146N increased IFM contractility (Kronert et al. 2018). Interestingly, the mutations characterized in these studies (that lead to increased contractility) have been frequently associated with more severe clinical symptoms compared to the R249Q mutation (Tyska et al. 2000; Palmer et al. 2004; Alpert et al. 2005; Seebohm et al. 2009). Comparing the effects of the Drosophila increased‐contractile‐mutant R146N with our current results revealed that R146N caused more damage to IFM myofibrils than R249Q, which is in agreement with the less severe symptoms observed in humans. Perhaps this might be a general trend for HCM mutations, but further studies on more HCM mutations are required to verify it.

Our TEM images also suggest that the R249Q mutation does not, in general, have severe effects on IFM morphology, when compared to the TEM images from Drosophila mutants that are known to cause a hypercontractile IFM phenotype (Kronert et al. 1995; Barton et al. 2007; Viswanathan et al. 2015). This suggests that low force production and decreased muscle stiffness due to R249Q myosin leads to less muscle fibre damage than increased contractility, which again could help explain the less severe clinical symptoms associated with R249Q HCM.

Super‐relaxed state

A recently proposed molecular mechanism for HCM is the disrupted super‐relaxed (SRX) state hypothesis. The myosin structure that may be associated with the SRX is called the interacting head motif (IHM) (Wendt et al. 1999; Zhao et al. 2009; Stewart et al. 2010). The IHM is characterized by dimeric myosin heads interacting and bending backward over the converter region and binding to the S2/rod domain of myosin, thereby reducing the ATPase activity of these sequestered heads when a muscle is relaxed. Based on their location in myosin, some HCM mutations have been proposed to inhibit the ability of myosin to form the IHM and SRX state (Moore et al. 2012; Spudich, 2014). The plateau‐like surface between the actin binding site and the converter domain, named the ‘myosin mesa’ contains many known HCM mutations. From TEM images and computational modelling, this area appears to bind to S2 while in the IHM (Spudich, 2015). However, HCM mutations on the ‘myosin mesa’ (such as R403Q) have been suggested to disrupt the stability of this structure, causing heads to be active when they should not be, resulting in increased muscle contractility. Recently, the R249Q mutation has been studied with respect to this hypothesis (Nag et al. 2017). Computer modelling showed R249's location on the blocking myosin head, suggesting it might interact with the proximal head's S2 region, and predicted that R249Q myosin would significantly reduce binding to proximal S2 compared to wild type. However, this interpretation of R249Q disrupting the IHM and SRX state, and thus increasing contractility does not agree with our results. First, if fewer heads were sequestered during the SRX state, a significant increase in passive tension would be expected. Second, if interpretations of the effect of impairing the SRX state are correct, we would also expect to see increased active tension, but we instead observed several indications of decreased force production. Third, the changes in cross‐bridge rate constants (implied from changes in 2πb and 2πc) are not easily explained by disruption of the SRX state. Finally, most proposed SRX state disruptions are predicted to produce a hypercontraction phenotype, but our R249Q results showed a clear decrease in contractility. In fact, our results could be more easily explained by the mutation increasing the likelihood of myosin entering the IHM, to stabilize the SRX state. A recent study of the regulatory light chain HCM mutation R58Q found evidence that it may be stabilizing the SRX state (Yadav et al. 2019).

Conclusions

Using our Drosophila IFM expression system, we observed the effect of HCM myosin mutation R249Q at the muscle and full organism levels and provided insights into its molecular mechanism. Understanding mechanisms behind HCM has been a challenge for decades. Conflicting data from varying approaches, plus the hundreds of known mutations, makes is difficult to discern whether a unifying mechanism exists or if multiple mechanisms yield various severities of HCM. We found that R249Q mainly decreased muscle mechanical function, with observed reductions in muscle force, speed and power, suggesting it does not fit the proposed increased contractile mechanism of HCM. Rather, this mutation probably yields its hypertrophic effect by some form of cardiac compensation for the decreased contractile activity arising from the mutant myosin motor.

Additional information

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Author contributions

Conception and design of the study: W.A.K., S.I.B., D.M.S. Mechanics experiments: K.M.B. Generation and characterization of the fly lines, TEM and molecular modelling: W.A.K. Full organism experiments: A.H. Data analysis and interpretation: K.M.B., W.A.K., A.H., D.M.S. Funding curation: S.I.B., D.M.S. Manuscript preparation: K.M.B., D.M.S. Manuscript editing: K.M.B., D.M.S., S.I.B. All authors have approved the final version of the manuscript and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work. All persons designated as authors qualify for authorship, and all those who qualify for authorship are listed.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health grants to D.M.S. (R01 AR055611) and S.I.B. (R37 GM32443). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Supporting information

Supplemental File S1: Data set.

Acknowledgements

Electron microscopy was carried out in the SDSU Electron Microscopy Facility.

Biography

Kaylyn Bell received her Bachelor's Degree in Biochemistry and Biophysics at Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute. She is continuing her research in biophysics at RPI with Dr. Douglas Swank for her PhD. Her work uses the Drosophila model system to characterize the muscle mechanical properties of myosin mutations that cause the heart disease hypertrophic cardiomyopathy, and the skeletal muscle disease Freeman‐Sheldon Syndrome. She is also investigating a possible myosin based mechanism behind the muscle phenomenon known as stretch activation.

K. M. Bell and W. A. Kronert contributed equally to this work.

Edited by: Michael Hogan & Satoshi Matsuoka

References

- Adhikari AS, Kooiker KB, Sarkar SS, Liu C, Bernstein D, Spudich JA & Ruppel KM (2016). Early‐onset hypertrophic cardiomyopathy mutations significantly increase the velocity, force, and actin‐activated ATPase activity of human β‐cardiac myosin. Cell Rep 17, 2857–2864. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alpert NR, Mohiddin SA, Tripodi D, Jacobson‐Hatzell J, Vaughn‐Whitley K, Brosseau C, Warshaw DM & Fananapazir L (2005). Molecular and phenotypic effects of heterozygous, homozygous, and compound heterozygote myosin heavy‐chain mutations. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 288, H1097–H1102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arnold K, Bordoli L, Kopp J & Schwede T (2006). The SWISS‐MODEL workspace: a web‐based environment for protein structure homology modelling. Bioinformatics 22, 195–201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bai F, Caster HM, Dawson JF & Kawai M (2015). The immediate effect of HCM causing actin mutants E99K and A230K on actin‐Tm‐myosin interaction in thin‐filament reconstituted myocardium. J Mol Cell Cardiol 79, 123–132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bai F, Caster HM, Rubenstein PA, Dawson JF & Kawai M (2014). Using baculovirus/insect cell expressed recombinant actin to study the molecular pathogenesis of HCM caused by actin mutation A331P. J Mol Cell Cardiol 74, 64–75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bai F, Weis A, Takeda AK, Chase B & Kawai M (2011). Enhanced active cross‐bridges during diastole: Molecular pathogenesis of tropomyosin's HCM mutations. Biophys J 100, 1014–1023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barton B, Ayer G & Maughan DW (2007). Site directed mutagenesis of Drosophila flightin disrupts phosphorylation and impairs flight muscle structure and mechanics. J Muscle Res Cell Motil 28, 219–230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Becker KD, Gottshall KR, Hickey R, Perriard JC & Chien KR (1997). Point mutations in human β cardiac myosin heavy chain have differential effects on sarcomeric structure and assembly: an ATP binding site change disrupts both thick and thin filaments, whereas hypertrophic cardiomyopathy mutations display normal assembly. J Cell Biol 137, 131–140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Becker KD, O'Donnell PT, Heitz JM, Vito M & Bernstein SI (1992). Analysis of Drosophila paramyosin: identification of a novel isoform which is restricted to a subset of adult muscles. J Cell Biol 116, 669–681. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bejsovec A & Anderson P (1988). Myosin heavy chain mutations that disrupt Caenorhabditis elegans thick filament assembly. Genes Dev 2, 1307–1317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bejsovec A & Anderson P (1990). Functions of the myosin ATP and actin binding sites are required for C. elegans thick filament assembly. Cell 60, 133–140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belus A, Piroddi N, Scellini B, Tesi C, D'Amati G, Girolami F, Yacoub M, Cecchi F, Olivotto I & Poggesi C (2008). The familial hypertrophic cardiomyopathy‐associated myosin mutation R403Q accelerates tension generation and relaxation of human cardiac myofibrils. J Physiol 586, 3639–3644. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blanchard E, Seidman C, Seidman JG, LeWinter M & Maughan D (1999). Altered crossbridge kinetics in the alphaMHC403/+ mouse model of familial hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Circ Res 84, 475–483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buvoli M, Hamady M, Leinwand LA & Knight R (2008). Bioinformatics assessment of β‐myosin mutations reveals myosin high sensitivity to mutations. Trends Cardiovasc Med 18, 141–149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cecchini M, Houdusse A & Karplus M (2008). Allosteric communication in Myosin V: from small conformational changes to large directed movements. PLoS Comp Biol 4, e1000129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collier VL, Kronert WA, O'Donnell PT, Edwards KA & Bernstein SI (1990). Alternative myosin hinge regions are utilized in a tissue‐specific fashion that correlates with muscle contraction speed. Genes Dev 4, 885–895. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coureux PD, Sweeney HL & Houdusse A (2004). Three myosin V structures delineate essential features of chemo‐mechanical transduction. EMBO J 23, 4527–4537. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coureux PD, Wells AL, Ménétrey J, Yengo CM, Morris CA, Sweeney HL & Houdusse A (2003). A structural state of the myosin V motor without bound nucleotide. Nature 425, 419–423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cuda G, Fananapazir L, Epstein ND & Sellers JR (1997). The in vitro motility activity of β‐cardiac myosin depends on the nature of the β‐myosin heavy chain gene mutation in hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. J Muscle Res Cell Motil 18, 275–283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis J, Davis LC, Correll RN, Makarewich CA, Schwanekamp JA, Moussavi‐Harami F, Wang D, York AJ, Wu H, Houser SR, Seidman CE, Seidman JG, Regnier M, Metzger JM, Wu JC & Molkentin JD (2016). A tension‐based model distinguishes hypertrophic versus dilated cardiomyopathy. Cell 165, 1147–1159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Debold EP, Schimitt JP, Patlak JB, Beck SE, Moore JR, Seidman JG, Seidman C & Warshaw DM (2007). Hypertrophic and dilated cardiomyopathy mutations differentially affect the molecular force generation of mouse α‐cardiac myosin in the laser trap assay. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 293, H284–H291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drummond DR, Hennessey ES & Sparrow JC (1990). Characterization of missense mutations in the Act88F gene of Drosophila melanogaster . Mol Gen Genet 226, 70–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geisterfer‐Lowrance AA, Kass S, Tanigawa G, Vosberg HP, McKenna W, Seidman CE & Seidman JG (1990). A molecular basis for familial hypertrophic cardiomyopathy: a β‐cardiac myosin heavy chain gene missense mutation. Cell 62, 999–1006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- George EL, Ober MB & Emerson CP Jr (1989). Functional domains of the Drosophila melanogaster muscle myosin heavy‐chain gene are encoded by alternatively spliced exons. Mol Cell Biol 9, 2957–2974. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greber‐Platzer S, Marx M, Fleischmann C, Suppan C, Dobner M & Wimmer M (2001). Beta‐myosin heavy chain gene mutations and hypertrophic cardiomyopathy in Austrian children. J Mol Cell Cardiol 33, 141–148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hernandez O, Szczesna‐Cordary D, Knollmann BC, Miller T, Bell M, Zhao J, Sirenko SG, Diaz Z, Guzman G, Xu Y, Wang Y, Kerrick WGL & Potter JD (2005). F110I and R278C troponin T mutations that cause familial hypertrophic cardiomyopathy affect muscle contraction in transgenic mice and reconstituted human cardiac fibers. J Biol Chem 280, 37183–37194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Josephson RK (1985). The mechanical power output of a tettigoniid wing muscle during singing and flight. J Exp Biol 117, 357–368. [Google Scholar]

- Kawai M & Brandt PW (1980). Sinusoidal analysis: a high resolution method for correlating biochemical reaction with physiological processes in activated skeletal muscles of rabbit, frog and crayfish. J Muscle Res Cell Motil 1, 279–303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kazmierczak K, Paulino EC, Huang W, Muthu P, Liang J, Yuan C, Rojas AI, Hare JM & Szczesna‐Cordary D (2013). Discrete effects of A57G‐myosin essential light chain mutation associated with familial hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 305, H575–H589. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keller DI, Coirault C, Rau T, Cheav T, Weyand M, Amann K, Lecarpentier Y, Richard P, Eschenhagen T & Carrier L (2004). Human homozygous R403W mutant cardiac myosin presents disproportionate enhancement of mechanical and enzymatic properties. J Mol Cell Cardiol 36, 355–362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kerrick WGL, Kazmierczak K, Xu Y, Wang Y, Szczesna‐Cordary D (2009). Malignant familial hypertrophic cardiomyopathy D166V mutation in the ventricular myosin regulatory light chain causes profound effects in skinned and intact papillary muscle fibers from transgenic mice. FASEB J 23, 855–865. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirschner SE, Becker E, Antognozzi M, Kubis HP, Francino A, Navarro‐López F, Bit‐Avragim N, Perrot A, Mirrakhimov MM, Osterziel KJ, McKenna WJ, Brenner B & Kraft T (2005). Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy‐related beta‐myosin mutations cause highly variable calcium sensitivity with functional imbalances among individual muscle cells. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 288, H1242–H1251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Köhler J, Winkler G, Schulte I, Scholz T, McKenna W, Brenner B & Kraft T (2002). Mutation of the myosin converter domain alters cross‐bridge elasticity. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 99, 3557–3562. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kronert WA, Bell KM, Viswanathan MC, Melkani GC, Trujillo AS, Huang A, Melkani A, Cammarato A, Swank DM & Bernstein SI (2018). Prolonged cross‐bridge binding triggers muscle dysfunction in a Drosophila model of myosin‐based hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. eLife 7, 1–27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kronert WA, O'Donnell PT, Fieck A, Lawn A, Vigoreaux JO, Sparrow JC & Bernstein SI (1995). Defects in the Drosophila myosin rod permit sarcomere assembly but cause flight muscle degeneration. J Mol Biol 249, 111–125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lankford EB, Epstein ND, Fananapazir L & Sweeney HL (1995). Abnormal contractile properties of muscle fibers expressing beta‐myosin heavy chain gene mutations in patients with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. J Clin Invest 95, 1409–1414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maron BJ, Gardin JM, Flack JM, Gidding SS, Kurosaki TT & Bild DE (1995). Prevalence of hypertrophic cardiomyopathy in a general population of young adults. Circ 92, 785–789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maron BJ & Maron MS (2013). Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Lancet 381, 242–255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moore JR, Leinwand L, Warshaw DM (2012). Understanding cardiomyopathy phenotypes based on the functional impact of mutations in the myosin motor. Circ Res 111, 375–385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nag S, Sommese RF, Ujfalusi Z, Combs A, Langer S, Sutton S, Leinwand LA, Geeves MA, Ruppel KM & Spudich JA (2015). Contractility parameters of human β‐cardiac myosin with the hypertrophic cardiomyopathy mutation R403Q show loss of motor function. Sci Adv 1, 1–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nag S, Trivedi DV, Sarkar SS, Adhikari AS, Sunitha MS, Sutton S, Ruppel KM & Spudich JA (2017). The myosin mesa and the basis of hypercontractility caused by hypertrophic cardiomyopathy mutations. Nat Struct Mol Biol 24, 525–533. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Donnell PT & Bernstein SI (1988). Molecular and ultrastructural defects in a Drosophila myosin heavy chain mutant: differential effects on muscle function produced by similar thick filament abnormalities. J Cell Biol 107, 2601–2612. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Donnell PT, Collier VL, Mogami K & Bernstein SI (1989). Ultrastructural and molecular analyses of homozygous‐viable Drosophila melanogaster muscle mutants indicate there is a complex pattern of myosin heavy‐chain isoform distribution. Genes Dev 3, 1233–1246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palmer BM, Fishbaugher DE, Schmitt JP, Wang Y, Alpert NR, Seidman CE, Seidman JG, VanBuren P & Maughan DW (2004). Differential cross‐bridge kinetics of FHC myosin mutations R403Q and R453C in heterozygous mouse myocardium. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 287, H91–H99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palmer BM, Wang Y, Teekakirikul P, Hinson JT, Fatkin D, Strouse S, VanBuren P, Seidman CE, Seidman JG & Maughan DW (2008). Myofilament mechanical performance is enhanced by R403Q myosin in mouse myocardium independent of sex. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 294, H1939–H1947. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palmiter KA, Tyska MJ, Haeberle JR, Alpert NR, Fananapazir L & Warshaw DM (2000). R403Q and L908V mutant beta‐cardiac myosin from patients with familial hypertrophic cardiomyopathy exhibit enhanced mechanical performance at the single molecule level. J Muscle Res Cell Motil 21, 609–620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramanath S, Wang Q, Bernstein SI & Swank DM (2011). Disrupting the myosin converter‐relay interface impairs Drosophila indirect flight muscle performance. Biophys J 101, 1114–1122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roopnarine O & Leinwand LA (1998). Functional analysis of myosin mutations that cause familial hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Biophys J 75, 3023–3030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenzweig A, Watkins H, Hwang DS, Miri M, McKenna W, Traill TA, Seidman JG & Seidman CE (1991). Preclinical diagnosis of familial hypertrophic cardiomyopathy by genetic analysis of blood lymphocytes. N Engl J Med 325, 1753–1760. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rubin GM & Spradling AC (1982). Genetic transformation of Drosophila with transposable element vectors. Science 218, 348–353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sata M & Ikebe M (1996). Functional analysis of the mutations in the human cardiac beta‐myosin that are responsible for familial hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Implication for the clinical outcome. J Clin Invest 98, 2866–2873. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seebohm B, Matinmehr F, Köhler J, Francino A, Navarro‐López F, Perrot A, Ozcelik C, McKenna WJ, Brenner B & Kraft T (2009). Cardiomyopathy mutations reveal variable region of myosin converter as major element of cross‐bridge compliance. Biophys J 97, 806–824. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spudich JA (2014). Hypertrophic and dilated cardiomyopathy: four decades of basic research on muscle lead to potential therapeutic approaches to these devastating genetic diseases. Biophys J 106, 1236–1249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spudich JA (2015). The myosin mesa and a possible unifying hypothesis for the molecular basis of human hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Biochem Soc Trans 43, 64–72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stewart MA, Franks‐Skiba K, Chen S & Cooke R (2010). Myosin ATP turnover rate is a mechanism involved in thermogenesis in resting skeletal muscle fibers. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 107, 430–435. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swank DM (2012). Mechanical analysis of Drosophila indirect flight and jump muscles. Methods 56, 69–77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swank DM, Vishnudas VK & Maughan DW (2006). An exceptionally fast actomyosin reaction powers insect flight muscle. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 103, 17543–17547. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swank DM, Wells L, Kronert WA, Morrill GE & Bernstein SI (2000). Determining structure/function relationships for sarcomeric myosin heavy chain by genetic and transgenic manipulation of Drosophila . Microsc Res Tech 50, 430–442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tohtong R, Yamashita H, Graham M, Haeberle J, Simcox A & Maughan D (1995). Impairment of muscle function caused by mutations of phosphorylation sites in myosin regulatory light chain. Nature 374, 650–653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trivedi DV, Adhikari AS, Sarkar SS, Ruppel KM & Spudich JA (2018). Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy and the myosin mesa: viewing and old disease in a new light. Biophys Rev 10, 27–48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]