Abstract

Background

Currently, there are no standard treatment guidelines for colpocleisis. Clinical practice varies widely for this safe and effective procedure.

Objective

The aim of this study was to evaluate the current practice patterns in the United States among surgeons who perform colpocleisis.

Methods

A 27-item anonymous Web-based survey was sent to all practicing physicians affiliated with the American Urogynecologic Society. It consisted of questions regarding the demographic background of the physicians and their current practice as it relates to colpocleisis.

Results

Of the 1422 physicians contacted, 322 responded (23%) to the questionnaire. Slightly more than half were female with an average time of 15 years in practice. The majority of respondents (79%) were urogynecologists. Most surgeons chose colpocleisis for its high success rate, short operating time, and low risk of complications. Approximately half of the providers performed both LeFort and total colpocleisis. Only 18% performed a routine hysterectomy at the time of surgery. Routine preoperative endometrial evaluation was preferred by 68% of the respondents, with 81% utilizing a transvaginal ultrasound first. Almost all providers would perform concomitant incontinence procedures, with 54% requiring a positive cough stress test and normal postvoid residual.

Conclusions

There is variation in the current practice of colpocleisis in the United States. LeFort colpocleisis is most commonly performed, and routine hysterectomy is uncommon. Two thirds of surgeons evaluate the endometrium prior to surgery. Concomitant anti-incontinence procedures appear to be standard.

Keywords: colpocleisis, hysterectomy, LeFort

Pelvic organ prolapse (POP) is a common problem, with approximately 200,000 procedures performed for prolapse in the United States each year.1,2 One in 9 women will undergo surgery for prolapse or incontinence by 80 years of age.3 Colpocleisis is an obliterative procedure for POP ideal for women who are no longer sexually active or cannot tolerate a more extensive procedure. It remains one of the most durable and least invasive surgical procedures for prolapse, with success rates of 98% to 100% reported.4–6 Recent studies continue to confirm high success rates and improved body image, with low morbidity and mortality.6–9 All colpocleisis procedures involve removal of the vaginal epithelium. The 2 most common types are partial and total colpocleisis. Partial colpocleisis (LeFort) involves surgical creation of a longitudinal vaginal septum by apposition of denuded anterior and posterior vaginal walls. LeFort colpocleisis is the only obliterative option if the uterus is to be preserved; however, it is also appropriate in cases of posthysterectomy prolapse. Both partial and total colpocleisis are commonly combined with levator plication and perineorrhaphy.4

Currently, there are no standard guidelines for colpocleisis. Among the wide variation that exists in clinical practice are LeFort versus total colpocleisis, routine preoperative endometrial evaluation, and concomitant procedures such as hysterectomy and procedures for urinary incontinence. The objective of this study was to evaluate the current practice patterns among providers performing colpocleisis and describe physician characteristics that might influence surgical decision making.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Institutional review board approval was obtained. A 4-page, 27-item Web-based survey was created using REDCap (Vanderbilt University, Memphis, Tenn). We utilized the CHERRIES (Checklist for Reporting Results of Internet E-Surveys) statement and checklist (www.equator-net-org) when creating and administering the survey.10 E-mail addresses of the physicians were obtained from a listing that was previously made available by the American Urogynecologic Society. All practicing physicians were contacted electronically via e-mail. Residents and fellows were excluded from the study. There were no incentives offered for survey completion. Respondents were not able to review or change answers to the survey once it was submitted. Information collected included physician year of birth, gender, race, years in practice, practice location, scope of practice, and practice setting. In addition, participants answered questions regarding reasons for choosing colpocleisis; minimum age cutoffs; preferred type of colpocleisis; concomitant procedures performed, including hysterectomy, levator myorrhaphy, anterior colporrhaphy, perineorrhaphy, and incontinence procedures, and any diagnostic workup performed to evaluate the uterus prior to surgery. Up to 3 e-mails were sent until a response was obtained between October 2013 and January 2014. All analyses were performed using R Core Team (2013) (R foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria).

RESULTS

A total of 1422 physicians were contacted, and 322 physicians responded to the survey during the study period. The response rate for this Web-based survey was 23%. One hundred nonrespondents were randomly sampled. Nonrespondents were of similar age to those who responded to the survey with a median age of 46 years compared with a median of 47 years for respondents. Nonrespondents were less likely to be female compared with respondents (40% vs 54%). The majority of nonrespondents, 60%, were practicing urogynecologists, compared with 83% for respondents.

Demographics of respondents are delineated in Table 1. The majority of respondents self-identified as urogynecologists, 79%, and 12% of respondents were general obstetrician-gynecologists. Of all the respondents, 98% reported performing at least 1 to 2 POP procedures each week.

TABLE 1.

Demographics of Respondents

| Characteristics | n(%) |

|---|---|

| Gender | |

| Female | 180(54) |

| Male | 151(46) |

| Race | |

| White | 261(80) |

| Asian | 32 (10) |

| Latino/Latina | 13 (4) |

| African American | 12 (4) |

| Other | 7 (2) |

| Location | |

| Urban, not inner city | 133(40) |

| Suburban | 120(36) |

| Urban, inner city | 59 (18) |

| Rural | 14 (3) |

| Other | 7 (2) |

| Setting | |

| Academic | 127(38) |

| Private practice | 120(36) |

| Hospital based | 74 (22) |

| Other | 9 (3) |

| Scope | |

| Urogynecology | 263(79) |

| General obstetrician-gynecologist | 40 (12) |

| Gynecology | 17 (5) |

| Female urology | 13 (4) |

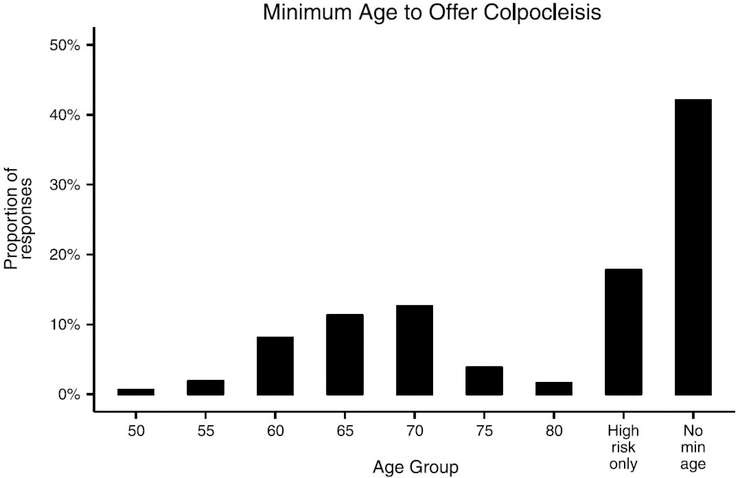

Almost all (97%) of the survey participants stated that they performed colpocleisis as part of their practice. The top 3 reasons cited for choosing colpocleisis were high success rate, short operating time, and low complication rates. When asked if there was a minimum age at which the practitioner would offer a colpocleisis, most respondents reported that age 65 to 70 years would be an acceptable minimum age (Fig. 1). Forty-one percent had no age cutoff for offering colpocleisis, whereas 18% reserved colpocleisis for only high-risk surgical candidates with multiple comorbidities.

FIGURE 1.

Minimum age to offer colpocleisis.

Routine hysterectomy at the time of colpocleisis was of particular interest in this study. Only 57 participants (18%) reported routine hysterectomy at the time of colpocleisis. When all respondents were questioned regarding their policy on performing hysterectomy, 45% reported performing hysterectomy only on those who were young and healthy (Fig. 2). A very small fraction (2.5%) reported they would perform a hysterectomy only if there were other indications for it. When we further evaluated the characteristics of those who favored concomitant hysterectomy, it was more popular among the female practitioners. Approximately one fourth of all female respondents (24%) routinely reported this compared with 12% of males, P = 0.004. Geographic location was also significantly influential in this practice pattern, with those in the Northeast performing routine hysterectomy the most and those in the South the least. We also found that routine hysterectomy was performed more frequently in nonacademic settings (23%) compared with academic hospitals (12%) (Fig. 3) (Table 2).

FIGURE 2.

Routine hysterectomy with colpocleisis.

FIGURE 3.

Colpocleisis type most often performed.

TABLE 2.

Routine Hysterectomy Performed at Time of Colpocleisis, Respondents Characteristics

| % | n | |

|---|---|---|

| Gender | ||

| Female | 0.23 | 37 |

| Male | 0.121 | 17 |

| Setting | ||

| Academic | 0.134 | 16 |

| Hospital based | 0.152 | 10 |

| Other | 0.25 | 2 |

| Private practice | 0.239 | 26 |

| Region | ||

| Midwest | 0.23 | 20 |

| Northeast | 0.277 | 13 |

| South | 0.092 | 9 |

| West | 0.171 | 12 |

When queried on the type of colpocleisis performed most often, approximately half (47%) of providers reported performing both LeFort and total colpocleisis with equal frequency. Among providers who performed only 1 type of colpocleisis, LeFort appeared to be the more common, 31% versus 22%. Providers who performed LeFort exclusively cited the shorter operating time and less dissection as their primary reasons for doing so. Those who performed only total colpocleisis preferred it because they felt LeFort would fail more often (29%), they were better trained in total colpocleisis (19%), or that the channels may not be wide enough to allow for drainage (15%). The most commonly cited “other” reason for performing total colpocleisis was that most of their patients had no uterus or that they would be performing concomitant hysterectomy (22%). A greater proportion of female providers (23%) performed total colpocleisis compared with male (21%), and total colpocleisis was more frequently performed in nonacademic settings (hospital based: 24%, private practice: 26%) compared with those at academic institutions (18%). LeFort colpocleisis was most commonly performed in the West and least commonly in the Midwest, whereas total colpocleisis was most commonly performed in the Midwest and least commonly in the South (Fig. 3).

The majority (68%) of respondents stated that they routinely performed preoperative workup for endometrial evaluation to rule out uterine pathology on all colpocleisis candidates. Pelvic ultrasound was the most commonly (81%) performed evaluation method followed by dilatation and curettage with or without hysteroscopy (14%). Only 6% of the participants thought a routine gynecologic examination and, if indicated, a Papanicolaou smear would be sufficient. There were no specific practitioner characteristics that influenced the providers’ inclination to perform a preoperative workup.

Concurrent anti-incontinence procedures were routinely performed by 94% of participating providers, but 50% require a positive cough stress test and the absence of urinary retention, whereas 36% recommend a sling regardless of urinary retention. Fourteen percent recommend an anti-incontinence procedure on all patients undergoing colpocleisis. When we stratified the data by gender and scope of practice, we found that women were more likely not to offer any anti-incontinence procedure compared with men (8% of women and 4% of men). Providers in nonacademic settings were also more likely to recommend anti-incontinence procedures with colpocleisis. There were no regional differences.

Routine concomitant procedures were common. The most frequently performed procedures were posterior colpoperineorrhaphy (73%) and levator myorrhaphy (35%), either alone or in combination. Forty-three respondents (10%) reported no routine concomitant procedures. There was no obvious variability in procedures by gender, location, or practice type.

DISCUSSION

Despite its increasing popularity in our aging population, there still is no standard approach to colpocleisis, likely because of lack of long-term prospective studies. Our survey indicated that more providers reported performing LeFort colpocleisis because it requires less dissection and shorter operating time. This seems to be a reasonable choice especially because many colpocleisis candidates are older and frail women with multiple comorbid conditions.

Another interesting finding of this survey is that colpocleisis is not necessarily reserved for only older women with high surgical risks. In fact, more than 40% of survey participants did not even consider a lower age limit for colpocleisis. In this age of liability concerns with mesh-based procedures, many surgeons may favor colpocleisis for advanced and recurrent prolapse cases. Patients may also be wary of mesh use for their surgeries when their native tissue repairs fail.

In our survey, more than 80% of respondents did not choose to perform hysterectomy routinely at the time of colpocleisis, but almost 70% preferred routine preoperative endometrial evaluation. Most practitioners reported pelvic ultrasound (81%) as their first choice, followed by dilatation and curettage with or without hysteroscopy (14%). In a recent study by Ramm et al,11 reporting from 4 institutions, they noted a wide variation in this practice without any clear algorithms at any of these centers. In their sample, only 27% of the patients were screened with endometrial sampling and/or ultrasound.

Our survey suggested that fear from future cancer risk compelled most surgeons to do preoperative endometrial evaluation but did not convince the majority of them to consider routine hysterectomy. This is likely due to anticipation of increased morbidity associated with hysterectomy. This practice is supported by 3 studies that showed increased blood loss, conversion to laparotomy, and operating time without any clinical benefit when hysterectomy was performed concomitant with colpocleisis.12–14

There is no doubt that all practitioners would evaluate the uterus in symptomatic women considering pelvic floor repair. The dilemma regarding endometrial screening occurs when a totally asymptomatic woman is preparing for colpocleisis. Our extensive search of MEDLINE from its inception to March 2016 indicated that there have been only 4 reported cases of uterine cancer after colpocleisis.12–17 Recently, tremendous attention has been focused on the incidence of uterine malignancy, the role of routine hysterectomy, and preoperative uterine evaluation particularly in women undergoing surgery for POP. These studies indicated that unexpected uterine cancer occurred in only 0% to 0.8%18–20 In addition, a recent cost-utility analysis concluded that universal endometrial evaluation with ultrasound and/or endometrial sampling was not cost-effective in asymptomatic women who underwent colpocleisis.21 Finally, a decision analysis done by our group revealed that concomitant hysterectomy would be justified only if the risk of endometrial cancer was 36.8% or higher.22

One should bear in mind that LeFort approach does not preclude the timely diagnosis of endometrial cancer. As long as channels are built appropriately, and their patency is confirmed on follow-up examinations, the presentation of any endometrial pathologic process should not be affected. If the endometrial bleeding can pass through tight postmenopausal cervical canal, so it should via the vaginal channels that remain after colpocleisis. In addition, successful endometrial evaluation through vaginal channels via hysteroscopy and subsequent minimally invasive hysterectomy has been described.23

Many patients with advanced prolapse present with elevated postvoid residual despite urinary incontinence. Studies have shown that anti-incontinence procedures at the time of colpocleisis do not worsen patient outcomes, and urinary retention rarely persists.2 In this study, anti-incontinence procedures appeared to be standard, with more than 95% of surgeons performing concomitant incontinence procedures. Fourteen percent of surgeons chose to perform an anti-incontinence procedure on all patients despite preoperative incontinence testing. A recent decision analysis determined that both a staged or concomitant midurethral sling is clinically reasonable strategies.24 A retrospective study of more than 200 patients confirmed that a concomitant midurethral sling improves continence with minimal risk of voiding dysfunction.25

This study is the first to describe practice patterns among practitioners performing colpocleisis. Almost 80% of the respondents in this study were urogynecologists; thus, in essence, this study is a reflection of urogynecologic practice in this country. Hence, the information elucidated here could be useful when developing standards for best clinical practice. The weakness of the study is its low response rate despite 3 separate mailings. Although controversial, we could have added an incentive to boost our response rate. In addition, response to Web-based survey is considerably different to paper-based surveys and as such should be held to different standards. In order to design our survey, we followed the CHERRY guidelines, which are regarded as the standard for Web-based surveys.10 According to the book titled, Conducting Online Surveys by Sue and Ritter,26 our study qualifies as an exploratory survey, which has an important place in developing concepts and generating hypotheses through nonrandom samples of target population.

Our current survey has left us with many questions regarding colpocleisis. Because of the variability in procedures performed, we limited our survey to include total and LeFort colpocleisis. It is clear that many surgeons perform some variation of the afore-mentioned procedures. A future survey should include questions regarding variations in the definition of the procedure, as well as questions addressing variability in technique. In addition, this survey focused on endometrial cancer workup as we anticipated that most surgeons would have a higher age cutoff for performing the procedure. We learned that for 40% there is no age cutoff for considering colpocleisis. As such, questions regarding screening patterns for Pap smears and human papillomavirus testing when leaving the uterus in situ would be important to explore.

Our survey results indicate that there are variations in practice among surgeons performing colpocleisis. In general, practice patterns do appear to follow current literature. Gender and practice setting appear to influence practice patterns. More research is needed to standardize clinical practice. We are hopeful that long-term outcome data from recently implemented registries may be able to provide the basis of evidence-based clinical guidelines and algorithms for colpocleisis as well.

Acknowledgments

This project was supported by the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences, National Institutes of Health, award no. UL1TR000073 and no. UL1TR001064. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH.

Footnotes

The authors declare that they have nothing to disclose.

The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

REFERENCES

- 1.Jones KA, Shepherd JP, Oliphant SS, et al. Trends in inpatient prolapse procedures in the United States, 1979–2006. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2010; 202(5):501.e1–e7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Boyles SH, Weber AM, Meyn L. Procedures for pelvic organ prolapse in the United States, 1979–1997. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2003;188(1): 108–115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Olsen AL, Smith VJ, Bergstrom JO, et al. Epidemiology of surgically managed pelvic organ prolapse and urinary incontinence. Obstet Gynecol 1997;89(4):501–506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fitzgerald MP, Richter HE, Siddique S, et al. Colpocleisis: a review. Int Urogynecol J Pelvic Floor Dysfunct 2006;17(3):261–271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Abbasy S, Kenton K. Obliterative procedures for pelvic organ prolapse. Clin Obstet Gynecol 2010;53(1):86–98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zebede A, Smith AL, Plowright LN, et al. Obliterative LeFort colpocleisis in a large group of elderly women. Obstet Gynecol 2013; 121(2 pt 1):279–284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Crisp CC, Book NM, Smith AL, et al. Body image, regret, and satisfaction following colpocleisis. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2013;209 (5):473.e1–473.e7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Vij M, Bombieri L, Dua A, et al. Long-term follow-up after colpocleisis: regret, bowel, and bladder function. Int Urogynecol J 2014;25(6):811–815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mueller MG, Ellimootil C, Abernethy MG, et al. Colpocleisis: a safe, minimally invasive option for pelvic organ prolapse. Female Pelvic Med Reconstr Surg 2015;21(1):30–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Eysenbach G Improving the quality of Web surveys: the Checklist for Reporting Results of Internet E-Surveys (CHERRIES). J Med Internet Res 2004;6(3):e34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ramm O, Gleason JL, Segal S, et al. Utility of preoperative endometrial assessment in asymptomatic women undergoing hysterectomy for pelvic floor dysfunction. Int Urogynecol J 2012;23(7):913–917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.von Pechmann WS, Mutone M, Fyffe J, et al. Total colpocleisis with high levator plication for the treatment of advanced pelvic organ prolapse. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2003;189(1):121–126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hoffman MS, Cardosi RJ, Lockhart J, et al. Vaginectomy with pelvic herniorrhaphy for prolapse. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2003;189(2): 364–370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hill AJ, Walter MD, Unger CA. Perioperative adverse events associated with colpocleisis for uterovaginal and posthysterectomy vaginal vault prolapse. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2016;214(4):501.e1–501.e6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mazer C, Israel SL. The Le Fort colpocleisis; an analysis of 43 operations. Am J Obstet Gynecol 1948;56(5):944–949. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Falk HC, Kaufman SA. Partial colpocleisis: the Le Fort procedure; analysis of 100 cases. Obstet Gynecol 1955;5(5):617–627. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hanson GE, Keettel WC. The Neugebauer–Le Fort operation. A review of 288 colpocleises. Obstet Gynecol 1969;34(3):352–357. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bonnar J, Kraszewski A, Davis WB. Incidental pathology at vaginal hysterectomy for genital prolapse. J Obstet Gynaecol Br Commonw 1970;77(12):1137–1139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Renganathan A, Edwards R, Duckett JR. Uterus conserving prolapse surgery—what is the chance of missing a malignancy? Int Urogynecol J 2010;21(7):819–821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wan OY, Cheung RY, Chan SS, et al. Risk of malignancy in women who underwent hysterectomy for uterine prolapse. Aust N Z J Obstet Gynaecol 2013;53(2):190–196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kandadai P, Flynn M, Zweizig S, et al. Cost-utility of routine endometrial evaluation before Le Fort colpocleisis. Female Pelvic Med Reconstr Surg 2014;20(3):68–173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jones KA, Zhuo Y, Solak S, et al. Hysterectomy at the time of colpocleisis: a decision analysis. Int Urogynecol J 2015;27(5): 805–810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Harmanli O, Celik H, Jones KA, et al. Minimally invasive diagnosis and treatment of endometrial cancer after LeFort colpocleisis. Female Pelvic Med Reconstr Surg 2013;19(4):242–244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Oliphant SS, Shepherd JP, Lowder JL. Midurethral sling for treatment of occult stress urinary incontinence at the time of colpocleisis: a decision analysis. Female Pelvic Med Reconstr Surg 2012;18(4): 216–220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Smith AL, Karp DR, Lefevre R, et al. LeFort colpocleisis and stress incontinence: weighing the risk of voiding dysfunction with sling placement. Int Urogynecol J 2011;22(11):1357–1362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sue VM, Ritter LA. Conducting Online Surveys. 2nd ed. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications; 2012. [Google Scholar]