Abstract

Background

Neuropsychiatric safety and relative efficacy of varenicline, bupropion, and transdermal nicotine patch (NRT) in those with psychiatric disorders is of interest.

Methods

We performed secondary analyses of safety and efficacy outcomes by psychiatric diagnosis in EAGLES, a 12-week, randomized, double-blind, triple-dummy, placebo- and active-(NRT)-controlled trial of varenicline and bupropion with 12-week follow-up, in a subset population, n=4092, with a primary psychotic (n=390), anxiety (n=792) or mood (n=2910) disorder. Primary endpoint parameters were incidence of pre-specified moderate and severe neuropsychiatric adverse events (NPSAEs) and week 9-12 continuous abstinence rates (9-12CAR).

Results

The observed NPSAE incidence across treatments was 5.1-6.3% in those with a psychotic disorder, 4.6-8.0% in those with an anxiety disorder, and 4.6-6.8% in those with a mood disorder. Neither varenicline nor bupropion were associated with significantly increased NPSAEs relative to NRT or placebo in the psychiatric cohort or any psychiatric diagnostic sub-cohort. There was a significant effect of treatment on 9-12CAR (p<0.0001) and no significant treatment by diagnostic sub-cohort interaction (p=0.24). Abstinence rates with varenicline were superior to bupropion, NRT and placebo, and abstinence with bupropion and NRT was superior to placebo. Within-diagnostic sub-cohort comparisons of treatment efficacy yielded estimated odds ratios for 9-12CAR versus placebo of > 3.00 for varenicline, >1.90 for bupropion and > 1.80 for NRT for all diagnostic groups.

Conclusions

Varenicline, bupropion, and nicotine patch are well tolerated and effective in adults with psychotic, anxiety, and mood disorders. The relative effectiveness of varenicline, bupropion and NRT vs placebo did not vary across psychiatric diagnoses.

Keywords: smoking cessation, schizophrenia, anxiety, mood, varenicline, bupropion

INTRODUCTION

Despite strong evidence for efficacy of first-line pharmacotherapies for smoking cessation in those with psychotic and mood disorders,1–10 smoking prevalence remains higher and is declining more slowly in those with mental health conditions than in the general population11–14, with one in 3 cigarettes in the US and UK sold to someone with a mental illness.13,15 Despite the fact that the mortality gap, largely due to smoking-related illness, for those with a serious mental illness compared to those in the general population is large and growing,16–18 pharmacotherapeutic cessation aids are underutilized in those with mental illness, arguably due at least in part to neuropsychiatric (NPS) safety concerns13,19–27. The health benefit of smoking cessation is clear,28,29 thus assessment of relative NPS safety and efficacy of smoking cessation pharmacotherapies in large samples of smokers with psychiatric illness is needed by clinicians, policy-makers, and patients in order to clarify their benefit-to-risk ratio.

Evaluating Adverse Events in a Global Smoking Cessation Study (EAGLES; NCT01456936) was a large, randomized controlled trial to evaluate NPS safety and efficacy of varenicline and bupropion compared with placebo and transdermal nicotine patch (NRT) for smoking cessation in adults with and without psychiatric illness.30 In the overall EAGLES study population, neither varenicline nor bupropion had significantly greater risk for NPSAEs than NRT or placebo, while those assigned to varenicline had significantly superior continuous abstinence rates (CARs) to those on bupropion, NRT or placebo, and those assigned to bupropion and NRT had superior CARs to those on placebo. In the primary report of this study, those with a lifetime psychiatric illness were reported in aggregate to have no difference in relative treatment safety or efficacy than those without a psychiatric illness.30 Random assignment to study medication in the EAGLES psychiatric cohort was stratified according to pre-specified diagnostic categories, those with psychotic (PD), anxiety (AD) and mood disorders (MD).

In order to inform treatment decision-making for smokers with psychotic, anxiety, and mood disorders, the primary aim of this analysis was to estimate the neuropsychiatric adverse event (NPSAE) rate with varenicline, bupropion, transdermal NRT patch and placebo in smokers with PD, AD, and MD. Further, we sought to compare the efficacy for continuous tobacco abstinence from study week 9 to the end of treatment (9-12CAR) and to the 6-month follow up (9-24CAR) for these treatments within these diagnostic categories. We addressed these aims while assessing the impact of patient-level factors: comorbid substance use disorder (SUD), severity of nicotine dependence, and sex, previously reported to impact smoking cessation success.31–33 While the primary aim of the paper was estimation of NPSAE rates in the diagnostic by treatment subgroups outlined, for the abstinence aim, it was our hypothesis that varenicline would be associated with higher rates of smoking cessation than NRT or bupropion, and all active treatments would be associated with superior abstinence rates to placebo in all three diagnostic groups.

MATERIALS and METHODS

Study design

EAGLES was a multinational, multicenter, randomized, double-blind, placebo- and active (NRT)-controlled trial, conducted between November 2011 and January 2015. The primary report provides full details of the study design and primary outcomes.30

Participants

Eligible participants for the psychiatric cohort were adults, aged 18-75 years, who smoked ≥10 cigarettes per day, with exhaled carbon monoxide (CO) >10 parts per million (ppm) at screening, were motivated to stop smoking, met Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition, Text Revision (DSM-IV-TR)34 diagnostic criteria for current or lifetime psychotic disorders (PD) including schizophrenia and schizoaffective disorders; anxiety disorders (AD) including panic disorder, with or without agoraphobia, post-traumatic stress disorder, obsessive-compulsive disorder, social phobia, and generalised anxiety disorder; mood disorders (MD) including major depressive disorder or bipolar disorder; or borderline personality disorder. Those with qualifying primary psychiatric disorders were not excluded for other psychiatric comorbidities, but those secondary allowable diagnoses were also pre-specified and excluded de-stabilizing psychiatric conditions such as alcohol and other drug use disorders within the previous 12 months. Because bupropion use in bipolar disorder was not allowed in European Union countries per prescribing guidelines, potential participants with bipolar disorder were excluded at the EU study sites. Smokers with a primary diagnosis of borderline personality disorder were enrolled; however, this sub-cohort was small (24 participants) and thus not included in these analyses. To operationalize clinical stability required for enrollment, the following were exclusionary: Clinical Global Impression Severity rating ≥5 (i.e., markedly ill with intrusive symptoms that impair social/occupational function or cause intrusive levels of distress)35, exacerbation of psychiatric condition in the prior 6 months, change in psychiatric medication or dose in the prior 3-months, active suicidal ideation with intent or plan, as assessed with Item 5 of the Columbia-Suicide Severity Rating Scale (C-SSRS), suicidal behavior in the prior 12-months as assessed with the C-SSRS, or considered by the investigator to be at imminent risk of suicidal or self-injurious behavior; active SUD in the prior 12-months, urine drug screen positive for non-prescribed addictive drugs.

Randomization, masking, and study treatment

Computer-generated randomized assignment to varenicline 1mg twice-daily, bupropion sustained-release 150mg twice-daily, NRT 21mg per day with taper, or placebo was done in a 1:1:1:1 ratio with block size of 8 for each diagnostic sub-cohort (PD, AD, and MD) by-region combination in a triple-dummy (each participant not in the placebo arm received 1 active and 2 placebo treatments, e.g., 1 patch and 2 pills per day, each pill to be taken bid) parallel-group design for 12-week treatment and 12-week follow-up phases. Participants and research personnel were blinded to treatment assignments.

Participants set a target-quit-date 1 week after randomization, coinciding with the end of varenicline and bupropion up-titration and initiation of NRT. Ten minute individual smoking cessation counseling was provided at each study visit36. Study visits were weekly for 6 weeks, biweekly for 6 weeks, then at weeks 13, 16, 20, and 24. Telephone contacts to determine smoking status were conducted weekly between study visits. Participants were encouraged to complete all study visits even if treatment was discontinued.

Outcomes

Safety

The primary safety endpoint was occurrence of at least one treatment-emergent severe (significant interference with functioning) adverse event of anxiety, depression, feeling abnormal or hostility and/or a moderate (some interference with functioning) or severe adverse event of agitation, aggression, delusions, hallucinations, homicidal ideation, mania, panic, paranoia, psychosis, suicidal ideation, suicidal behavior or completed suicide. The primary endpoint was met when participants reported ≥1 event that coded to any of the pre-defined Medical Dictionary for Regulatory Activities (MedDRA, v.18.0)-derived preferred terms across these 16 symptom categories during treatment or within 30 days of treatment discontinuation. Severity criteria for the primary NPSAE outcome were pre-specified; anxiety, depression, feeling abnormal, and hostility were required to be severe only to try to distinguish them from events that were expected to be common during cessation attempts.

Secondary safety endpoints included incidence of each component of the primary NPSAE endpoint and all that were rated as severe, Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale ratings (HADS)37, and reports of suicidal ideation or behavior elicited by the C-SSRS)38.

Efficacy

The main efficacy endpoint was CAR for weeks 9-12. To meet the endpoint, participants were considered abstinent at a study visit who reported tobacco abstinence since the previous study visit at each weekly visit from weeks 9 to 12 and to have had expired carbon monoxide (CO) concentration of ≤10 ppm at in-clinic study visits (weeks 10 and 12). Participants who discontinued the study or were lost to follow-up through week 12 were considered non-abstinent. The secondary efficacy endpoint was CAR for weeks 9-24, defined similarly, i.e. reported abstinence since the previous visit at each weekly visit from weeks 9 to 24 and CO concentrations < 10 ppm at in-clinic study visits (weeks 10, 12, 13, 16, 20, and 24), with subjects who discontinued the study or were lost to follow-up through week 24 considered non-abstinent.

Assessments

Psychiatric diagnosis was assessed at screening with the Structured Clinical Interviews for DSM-IV-TR Axis I and II Disorders.34,40 Severity of cigarette dependence was assessed with the Fagerström Test for Cigarette Dependence (FTCD).41 NPSAEs were assessed at each study visit with open-ended questions, direct observation, and the semi-structured Neuropsychiatric Adverse Events Interview (NAEI)1,30 Positive responses on the NAEI were evaluated for frequency, duration, and severity to determine if they were NPSAEs. Psychiatric symptom severity was also assessed at each study visit with HADS37 and C-SSRS,38 and tobacco and nicotine use were assessed with a structured questionnaire and expired CO measurement. Investigators evaluated whether positive responses on the C-SSRS or proxy reports from family members or others were NPSAEs.

Statistical Analysis

This is a secondary analysis of safety and efficacy of varenicline and bupropion compared to NRT and placebo in those with PD, AD and MD within the EAGLES psychiatric cohort. The study was sized to assess treatment safety and efficacy within the overall psychiatric cohort that comprised these sub-cohorts, not within the sub-cohorts. The safety and efficacy endpoints were analyzed using generalized linear models (binomial; identity link for safety and logit link for efficacy) with model terms to account for treatment, diagnostic group (PD, AD, MD), region (US and non-US), treatment by diagnostic group interaction, sex, baseline FTCD total score, and history of SUD (presence/absence). The analysis of safety is reported with observed NPSAE rates with confidence intervals, point estimates of NPSAE rates with confidence intervals from the model, and risk differences. Efficacy is reported utilizing observed abstinence rates and odds ratios. To address multiplicity concerns, pairwise treatment comparisons were restricted by psychiatric diagnosis (i.e. a slice procedure) with a Tukey based method for controlling family-wise error rate. Number-needed-to-treat (NNT) was calculated as the inverse of the absolute risk reduction.

RESULTS

Participants: 4050 participants received at least one dose of study medication and were included in the safety cohort, while 4092 participants were randomized to study treatment and included in the efficacy cohort. See Consort Diagram, Supplemental Figure 1. See Table 1 for baseline demographic, smoking-related, and psychiatric characteristics by primary psychiatric diagnostic group and treatment assignment. Over 90% in the MD sub-cohort had a lifetime diagnosis of MDD; the remainder had a bipolar disorder. Half of those with MDD met diagnostic criteria for recurrent MDD. Over 20% of the sample met diagnostic criteria for a prior SUD; over 33% met DSM-IV diagnostic criteria for a comorbid Axis I psychiatric illness, and over 12% of participants reported a prior suicide attempt.

Table 1.

Baseline Demographic and Clinical Characteristics

| Psychotic Disorders (n=386) | Anxiety Disorders (n=782) | Mood Disorders (n=2882) | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Varenicline (n=95) | Bupropion (n=96) | NRT (n=99) | Placebo (n=96) | Varenicline (n=193) | Bupropion (n=200) | NRT (n=195) | Placebo (n=194) | Varenicline (n=731) | Bupropion (n=716) | NRT (n=713) | Placebo (n=722) | |

| Female Sex | 34 (35.8) | 32 (33.3) | 38 (38.4) | 34 (35.4) | 116 (60.1) | 124 (62.0) | 123 (63.1) | 110 (56.7) | 479 (65.5) | 470 (65.6) | 466 (65.4) | 482 (66.8) |

| Age (years) | 44.6 (11.6) | 44.6 (10.7) | 43.3 (10.2) | 45.3 (9.6) | 45.7 (11.6) | 45.2 (12.1) | 46.0 (11.0) | 44.7 (12.5) | 48.0 (11.7) | 47.4 (12.4) | 48.8 (11.5) | 47.7 (11.3) |

| Race | ||||||||||||

| White | 59 (62.1) | 58 (60.4) | 63 (63.6) | 65 (67.7) | 172 (89.1) | 171 (85.5) | 169 (86.7) | 165 (85.1) | 611 (83.6) | 582 (81.3) | 564 (79.1) | 589 (81.6) |

| Black | 33 (34.7) | 36 (37.5) | 31 (31.3) | 26 (27.1) | 17 (8.8) | 21 (10.5) | 18 (9.2) | 21 (10.8) | 95 (13.0) | 108 (15.1) | 126 (17.7) | 108 (15.0) |

| Asian* | 1 (1.1) | 2 (2.1) | 1 (1.0) | 1 (1.0) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.5) | 1 (0.5) | 0 (0.0) | 4 (0.5) | 7 (1.0) | 9 (1.3) | 6 (0.8) |

| Other/Unspecified* | 2 (2.1) | 0 (0.0) | 4 (4.0) | 4 (4.2) | 4 (2.1) | 7 (3.5) | 7 (3.6) | 7 (3.6) | 21 (2.9) | 19 (2.7) | 14 (2.0) | 19 (2.6) |

| Weight (kg) | 91.7 (25.9) | 89.1 (22.0) | 87.9 (21.7) | 87.3 (22.1) | 80.3 (20.2) | 80.9 (22.9) | 79.8 (21.5) | 80.0 (20.9) | 82.6 (20.9) | 82.0 (20.6) | 80.1 (19.3) | 82.9 (21.2) |

| Smoking characteristics | ||||||||||||

| FTCD score, mean (SD) | 6.8 (1.9) | 6.9 (1.6) | 6.8 (2.0) | 7.0 (1.7) | 5.9 (2.1) | 5.9 (2.0) | 6.0 (2.0) | 5.8 (2.3) | 6.0 (1.9) | 6.0 (1.9) | 5.8 (1.9) | 5.8 (1.9) |

| Duration of smoking, mean years (SD) | 26.1 (12.4) | 26.6 (11.4) | 24.9 (11.1) | 25.9 (10.7) | 27.3 (11.3) | 27.1 (12.2) | 28.1 (10.8) | 26.2 (12.2) | 29.7 (11.8) | 28.8 (12.6) | 29.7 (12.1) | 29.2 (11.5) |

| Cigarettes smoked per day in past month, mean (SD) | 22.5 (9.4) | 21.9 (7.2) | 23.9 (14.9) | 24.3 (9.6) | 20.8 (7.5) | 20.5 (8.2) | 22.0 (8.8) | 21.3 (8.1) | 20.2 (7.9) | 20.4 (8.3) | 20.0 (7.9) | 20.0 (7.9) |

| Prior quit attempts, mean (SD) | 2.2 (3.2) | 1.9 (2.1) | 2.2 (2.8) | 3.2 (6.4) | 3.1 (4.8) | 3.5 (6.9) | 2.5 (3.5) | 2.9 (3.9) | 3.6 (8.7) | 3.8 (7.3) | 3.8 (5.9) | 3.9 (12.6) |

| Participants with ≥1 prior quit attempt, (%) | 67 (70.5) | 70 (72.9) | 71 (71.7) | 69 (71.9) | 163 (84.5) | 169 (84.5) | 156 (80.0) | 168 (86.6) | 620 (84.8) | 602 (84.1) | 622 (87.2) | 614 (85.0) |

| Comorbid Axis I Diagnosis | 39 (41.1) | 28 (29.2) | 35 (35.4) | 39 (40.6) | 78 (40.4) | 89 (44.5) | 93 (47.7) | 77 (39.7) | 232 (31.7) | 248 (34.6) | 254 (35.6) | 249 (34.5) |

| Prior Substance Use Disorder | 32 (33.7) | 22 (22.9) | 20 (20.2) | 30 (31.3) | 42 (21.8) | 43 (21.5) | 46 (23.6) | 39 (20.1) | 150 (20.5) | 168 (23.5) | 168 (23.6) | 172 (23.8) |

| Lifetime Suicide Related Behavior from CSSRS | ||||||||||||

| Suicidal Ideation | 25 (26.3) | 28 (29.2) | 31 (31.3) | 27 (28.1) | 34 (17.6) | 48 (24.0) | 45 (23.1) | 45 (23.2) | 275 (37.6) | 277 (38.7) | 252 (35.3) | 275 (38.1) |

| Suicidal Behavior | 15 (15.8) | 19 (19.8) | 22 (22.2) | 14 (14.6) | 8 (4.1) | 13 (6.5) | 12 (6.2) | 11 (5.7) | 110 (15.0) | 108 (15.1) | 72 (10.1) | 97 (13.4) |

| HADS Scores | ||||||||||||

| Anxiety Subscale Score | 4.6 (4.0) | 5.2 (4.0) | 5.5 (4.5) | 4.9 (3.8) | 5.5 (3.8) | 5.6 (3.6) | 5.5 (4.3) | 5.8 (3.9) | 5.0 (3.8) | 5.2 (4.1) | 5.0 (3.8) | 5.0 (3.7) |

| Depression Subscale Score | 4.0 (3.6) | 4.1 (2.8) | 3.8 (3.3) | 3.7 (3.0) | 2.6 (2.9) | 2.9 (3.3) | 3.0 (3.4) | 2.6 (2.8) | 3.2 (3.3) | 3.4 (3.6) | 3.2 (3.2) | 3.1 (3.2) |

| Using Psychotropic Medication (%) | 94 (98.9) | 92 (95.8) | 95 (96.0) | 94 (97.9) | 114 (59.1) | 109 (54.5) | 109 (55.9) | 94 (48.5) | 395 (54.0) | 347 (48.5) | 354 (49.6) | 364 (50.4) |

Table 1 includes the Safety Cohort for the trial.

Asian and Other/Unspecified categories were combined for use in model

Neuropsychiatric Safety

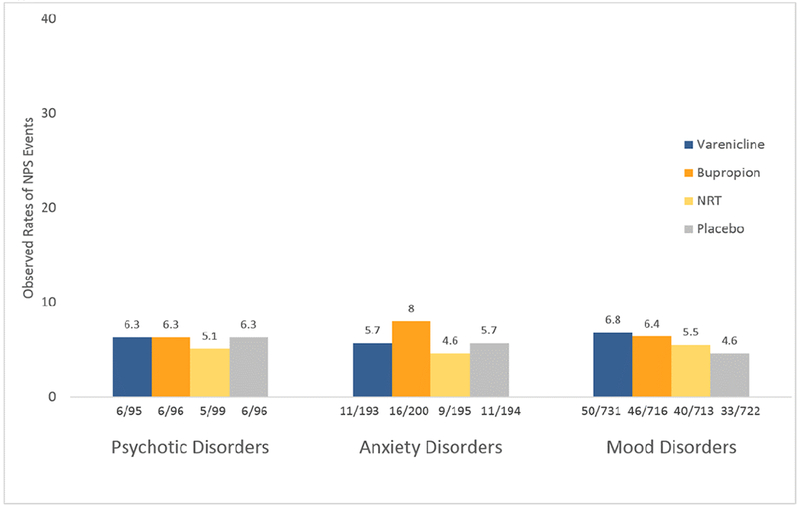

Of 4050 participants in the safety cohort, 239 (5.9%) experienced at least one moderate or severe NPSAE in the pre-specified, primary safety endpoint. The observed incidence of the primary NPSAE varied little across diagnostic by treatment groups. See Figure 1 for observed rates of NPSAEs. In the statistical model of those reporting ≥1 NPSAE, there was no significant main effect of treatment, psychiatric diagnostic subgroup (PD, AD, or MD), region, or baseline FTCD total score, and no treatment by psychiatric diagnostic group interaction. Female sex (p=0.0012) and a prior SUD (p<0.0001) were significantly associated with NPSAE occurrence. The point estimate for incidence of ≥1 moderate to severe NPSAEs during a smoking cessation attempt across treatment groups was 6.2 (1.6-10.8) on varenicline, 8.0 (3.3-12.8) on bupropion, 6.4 (2.3-10.5) on NRT and 7.3 (2.8-11.8) on placebo in those with PD, 6.5 (3.3-9.6) on varenicline, 8.7 (4.9-12.5) on bupropion, 3.8 (0.8-6.8) on NRT, and 6.1 (2.9-9.3) on placebo for those with AD, and 7.7 (5.7-9.6) on varenicline, 6.9 (5.0-8.7) on bupropion, 6.5 (5.0-8.6) on NRT, and 5.9 (4.3-7.5) on placebo for those with MD. See Table 2. Confidence intervals for the estimated difference in NPSAE rate between active treatments and placebo in the overall psychiatric cohort and within psychiatric diagnosis included zero for all comparisons.

Figure 1. Participants with One or More Observed NPSAE in the Primary Endpoint by Diagnostic Group*.

* Period for ascertainment of NPS AEs is during 12 weeks treatment and 30-day follow-up.

Table 2.

Incidence of the Primary Composite Neuropsychiatric Endpoint and Its Components

| Psychotic Disorders (n=386) | Anxiety Disorders (n=782) | Mood Disorders (n=2882)) | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Varenicline (n=95) | Bupropion (n=96) | Nicotine patch (n=99) | Placebo (n=96) | Varenicline (n=193) | Bupropion (n=200) | Nicotine patch (n=195) | Placebo (n=194) | Varenicline (n=731) | Bupropion (n=716) | Nicotine patch (n=713) | Placebo (n=722) | |

| Observed Incidence of the Primary Composite NPS Endpoint | 6 (6.3) | 6 (6.3) | 5 (5.1) | 6 (6.3) | 11 (5.7) | 16 (8.0) | 9 (4.6) | 11 (5.7) | 50 (6.8) | 46 (6.4) | 40 (5.6) | 33 (4.6) |

| Estimated Primary Composite NPS Endpoint (%[95% CI]) | 6.2 (1.6 to 10.8) | 8.0 (3.3 to 12.8) | 6.4 (2.3 to 10.5) | 7.3 (2.8 to 11.8) | 6.5 (3.3 to 9.6) | 8.7 (4.9 to 12.5) | 3.8 (0.8 to 6.8) | 6.1 (2.9 to 9.3) | 7.7 (5.7 to 9.6) | 6.9 (5.0 to 8.7) | 6.8 (5.0 to 8.6) | 5.9 (4.3 to 7.5) |

| Observed Events-All Components of Primary Composite NPS Endpoint | ||||||||||||

| Anxiety | 0 | 0 | 1 (1.0) | 0 | 1 (0.5) | 3 (1.5) | 2 (1.0) | 0 | 4 (0.5) | 1 (0.1) | 3 (0.4) | 2 (0.3) |

| Depression | 1 (1.1) | 0 | 0 | 1 (1.0) | 1 (0.5) | 1 (0.5) | 1 (0.5) | 1 (0.5) | 4 (0.5) | 3 (0.4) | 6 (0.8) | 4 (0.6) |

| Feeling abnormal | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (0.1) | 0 | 0 |

| Hostility | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Agitation | 2 (2.1) | 2 (2.1) | 1 (1.0) | 1 (1.0) | 4 (2.1) | 7 (3.5) | 2 (1.0) | 5 (2.6) | 19 (2.6) | 20 (2.8) | 18 (2.5) | 16 (2.2) |

| Aggression | 2 (2.1) | 0 | 0 | 2 (2.1) | 3 (1.6) | 3 (1.5) | 2 (1.0) | 3 (1.5) | 9 (1.2) | 6 (0.8) | 5 (0.7) | 3 (0.4) |

| Delusions | 1 (1.1) | 0 | 1 (1.0) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (0.1) | 0 | 0 |

| Hallucinations | 2 (2.1) | 2 (2.1) | 1 (1.0) | 0 | 1 (0.5) | 0 | 0 | 1 (0.5) | 2 (0.3) | 2 (0.3) | 1 (0.1) | 1 (0.1) |

| Homicidal ideation | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Mania | 0 | 1 (1.0) | 0 | 1 (1.0) | 1 (0.5) | 0 | 1 (0.5) | 1 (0.5) | 6 (0.8) | 8 (1.1) | 2 (0.3) | 4 (0.6) |

| Panic | 0 | 1 (1.0) | 1 (1.0) | 0 | 1 (0.5) | 6 (3.0) | 3 (1.5) | 2 (1.0) | 6 (0.8) | 9 (1.3) | 9 (1.3) | 5 (0.7) |

| Paranoia | 1 (1.1) | 0 | 0 | 1 (1.0) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (0.1) |

| Psychosis | 1 (1.1) | 1 (1.0) | 2 (2.0) | 1 (1.0) | 0 | 0 | 1 (0.5) | 0 | 3 (0.4) | 1 (0.1) | 0 | 0 |

| Suicidal behavior | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (0.1) | 1 (0.1) | 0 | 1 (0.1) |

| Suicidal ideation | 0 | 1 (1.0) | 1 (1.0) | 0 | 2 (1.0) | 1 (0.5) | 1 (0.5) | 0 | 3 (0.4) | 0 | 2 (0.3) | 2 (0.3) |

| Completed suicide | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

Table 2 presents the observed incidence of the primary NPS endpoint, it’s 16 components, and Supplemental Table 1 presents NPS events that were severe, that were serious adverse events (SAEs) or that led to treatment discontinuation, as well as suicidal ideation or behavior elicited by the C-SSRS. The observed rate of NPSAEs in the composite endpoint meeting criteria for an SAE, e.g. life-threatening, leading to hospitalization, was 1.4% overall, occurring in 55 of 4050 participants. The combined incidence of NPSAEs in the primary endpoint that were either SAEs, of severe intensity, or led to treatment discontinuation was 2.2% overall and similar across diagnostic group and treatment assignment.

Broadening the list of NPSAEs beyond the pre-defined primary NPS endpoint to include mild AEs and any events captured through AE reporting and coded to the MedDRA Psychiatric Disorder and Disturbances System Organ Class (SOC), including sleep-related AEs, yielded observed overall rates of 21.5% (83/386) in the PD cohort, 41.4% (324/782) with AD, and 41.7% (1202/2882) with MD. These were most commonly abnormal dreams with varenicline and NRT, anxiety with bupropion and NRT, and insomnia with bupropion and NRT. See Supplemental Table 2.

Additional Ratings of Anxiety, Depression, and Suicidal Ideation and Behavior

The rate of suicidal ideation and/or behavior on C-SSRS was similar across active treatments and placebo and <4% in each cohort (Supplemental Table 1). Average weekly HADS anxiety and depression subscale scores decreased (improved) from baseline to end of treatment + 30 days similarly across all treatment arms in each psychiatric cohort. See Supplemental Figure 2.

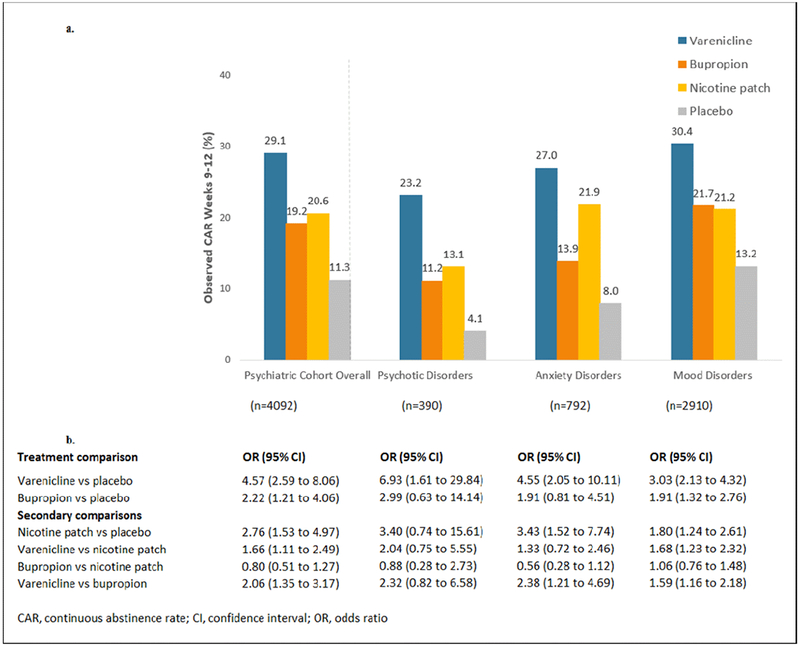

Treatment Efficacy for Continuous Abstinence

Of 4092 randomized participants, 820 achieved continuous abstinence for weeks 9-12 (9-12CA). Observed abstinence rates by treatment group in the psychiatric cohort and by diagnostic group are shown in Figure 2a. In the overall model for 9-12CA, there were significant effects of treatment (p<0.0001), psychiatric diagnostic subgroup (p<0.0001), region (p<0.0001), and FTCD total score (p<0.0001) and no significant treatment by psychiatric diagnosis interaction and no significant effect of sex or prior SUD. The ORs (95% CI) for 9-12CA vs. placebo in the overall psychiatric population were 4.57 (2.59, 8.06) for varenicline, 2.22 (1.21, 4.06) for bupropion and 2.76 (1.53, 4.97) for NRT patch. In within-diagnosis comparisons of treatment efficacy, the estimated odds ratios (OR) for 9-12CA for the active treatments versus placebo were > 3.0 for varenicline, >1.9 for bupropion and > 1.8 for NRT for all diagnostic groups; pairwise comparisons of treatment effects on 9-12CAR within diagnostic subgroups are provided in Figure 2b. The significant effect of psychiatric diagnosis was such that those with a MD were more likely than those with a PD to achieve continuous abstinence for weeks 9-12. Compared to placebo, number needed to treat (NNT) for 9-12CAR for varenicline was 6 for all disorders. NNT for bupropion was 12 for MD, 14 for PD, and 17 for AD. NNT for NRT was 8 for AD, 12 for PD and 13 for MD.

Figure 2.

Comparison of Continuous Abstinence Rates

2a. Observed Rates of Continuous Abstinence for Study Weeks 9-12

2b. Comparison of Odds of Continuous Abstinence for Weeks 9-12 by Treatment Assignment and Diagnostic Group*

* From GLIMMIX model that included terms for treatment, psychiatric diagnostic group, sex, FTND total score, prior alcohol or substance use disorder, and region

There were significant effects of treatment, region, and severity of dependence on continuous abstinence rates for weeks 9-24 (9-24CAR), with no significant effect of psychiatric diagnosis, sex, SUD, and no treatment by psychiatric diagnosis interaction. See Supplemental Figure 2 for pairwise comparisons of treatment effects on 9-24CAR within diagnostic subgroups. Compared to placebo, NNT for week 9-24CAR for varenicline was 8 for PD, and 11 for AD and MD. NNT for bupropion was 17 for PD, 18 for MD, and 26 for AD. NNT for NRT was 11 for AD, 17 for PD and 29 for MD.

DISCUSSION

EAGLES is the largest randomized, placebo-controlled smoking cessation trial in smokers with psychotic, anxiety, or mood disorders and the first trial to allow evaluation of relative neuropsychiatric safety and efficacy of first-line smoking cessation treatments and placebo in smokers with these psychiatric illnesses, who have higher smoking rates, lower cessation rates12, and a large and growing mortality disparity, for which tobacco smoking is considered to be the largest single contributor.13,16

Regarding neuropsychiatric safety, we report no main effect of treatment, no main effect of diagnostic sub-cohort, and no treatment by diagnostic sub-cohort interaction on incidence of NPSAEs in a model that included region, sex, nicotine dependence severity and prior SUD diagnosis. Female sex and prior SUD were associated with higher incidence of NPSAEs. The observed rate of NPSAEs in the primary outcome was 4.6 to 8.0%, similar across treatments within and between diagnostic groups. Thus, psychiatric diagnosis was not predictive of likelihood of experiencing a moderate to severe NPSAE, within the overall psychiatric cohort. Prior reports that female sex 42,43 and prior SUD44 are associated with more severe nicotine withdrawal symptoms are consistent with our findings. NPSAEs of mild intensity were fairly common, were similar across treatments, including placebo, and may represent expected events during a cessation attempt, independent of treatment. Importantly, no psychiatric sub-cohort or treatment by diagnostic sub-cohort category was identified as at particular risk for the most clinically worrisome NPSAEs, including hostility, aggression, severe depression, suicidal ideation, or suicidal behavior. Thus we do not find evidence that primary psychotic, anxiety, or mood disorder diagnosis should guide choice of pharmacotherapeutic cessation aids from a NPS safety standpoint.

In interpreting the safety data, it is notable that, while participants were considered to be clinically stable with respect to their psychiatric illness at enrollment, they were also at risk for NPSAEs in this trial. They had, on average, moderate severity of nicotine dependence at baseline, putting them at risk for nicotine withdrawal symptoms during a cessation attempt. Many had significant baseline psychiatric symptoms, including hallucinations, delusions, and depressive symptoms revealed by baseline assessments, despite clinically-determined best treatment for their psychiatric disorder. Half of those with MDD (90% of the MD sub-cohort) had recurrent MDD and one third met diagnostic criteria for a comorbid psychiatric illness, including a prior SUD, factors associated with heavier smoking, more severe dependence and fewer cessation attempts12,45,46, and 12% reported a suicide attempt in their lifetime. Thus we conclude that these safety results are relevant in a broad range of clinical settings where smokers with psychotic, anxiety, and mood disorders receive care and have the opportunity to be offered smoking cessation treatment, from mainstream physical health services to mental health settings.

Regarding efficacy, we previously reported a significant treatment effect on week 9-12 and 9-24 CARs, with varenicline superior to bupropion, NRT, and placebo, and bupropion and NRT superior to placebo, with no treatment by psychiatric cohort (vs. non-psychiatric cohort) interaction.30 Here, we similarly report a significant main effect of treatment on abstinence within the psychiatric cohort, and no treatment by diagnostic subgroup (PD, AD, or MD) interaction.

The major aim of this analysis was to provide guidance on clinical benefit-risk assessment of smoking cessation treatment choices for smokers with specific mental health conditions. This analysis demonstrates fairly common mild neuropsychiatric symptoms, not different by treatment, and relatively rare serious NPS AEs ascertained with the NAEI, C-SSRS and HADS, also not different by treatment, including placebo, or diagnostic group, while efficacy of all active treatments was demonstrated over placebo across all psychiatric diagnostic subgroups for week 9-12 and 9-24 CAR. Odds ratios for CA9-12 for active treatments compared with placebo within diagnostic groups ranged from 1.8 for bupropion for those with anxiety disorders to 6.9 for varenicline for those with psychotic disorders. The results notably replicate consistent reports of very low abstinence rates of approximately 4% for smokers with psychotic disorders with behavioral treatment (and placebo) alone.3 Low abstinence rates with behavioral treatment alone, combined with underutilization of effective smoking cessation pharmacotherapy13,22 may underlie the persistently high smoking rate and the growing mortality disparity, now estimated at over 28 years in those with psychotic disorders.16

The efficacy effect estimates within diagnostic cohorts are consistent with the prior literature where such comparisons exist3,6,7. Varenicline was superior to placebo for week 9-12 and 9-24 CAR for all diagnostic groups. In smokers with mood disorders, varenicline was significantly superior to bupropion and NRT, and varenicline, bupropion and NRT were significantly superior to placebo. For those with anxiety disorders, varenicline was significantly superior to bupropion and placebo and nominally superior to NRT, while NRT was significantly superior to placebo, and bupropion was nominally superior to placebo. For smokers with psychotic illness, varenicline was significantly superior to placebo and nominally superior to bupropion and NRT patch, while bupropion and NRT patch were nominally superior to placebo. Although some corrected confidence intervals for odds ratios included 1 for the within-diagnosis analyses, the anxiety and psychotic disorder sub-cohorts were not well powered for the comparisons; these did not change our conclusions based on the overall model and lack of significant treatment-by-diagnosis interaction.

An algorithm for clinical best practices is evolving for smoking cessation treatment in the general population, with varenicline and combination NRT having superior efficacy to single NRT and bupropion, all with superior efficacy to placebo.47 While more work is needed, there is interest in developing guidelines for smoking cessation treatment for smokers with psychiatric illnesses 3,48–50. This report should contribute to that effort with the first placebo-controlled efficacy data for NRT in smokers with psychotic disorders, for varenicline, bupropion, and NRT in those with many anxiety disorders, and for replicating findings from prior trials that smokers with psychotic, anxiety, and mood disorders can quit smoking with pharmacotherapeutic cessation aids with minimal effects on psychiatric symptoms.7,50–52 These results, taken in the context of the larger sample, in which varenicline had superior efficacy to NRT and bupropion and all active treatments tested were superior to placebo, with no treatment by diagnosis interaction, suggest that the relative effectiveness of smoking cessation therapies in the general population of smokers47 applies for smokers with psychotic, anxiety, and mood disorders.

Limitations:

This secondary analysis had limitations in addition to those reported for the overall trial.30 Without a control group not attempting to quit smoking, conclusions cannot be drawn regarding whether the observed NPSAE rate is greater than baseline risk for adults with stable psychotic, anxiety and mood disorders. Dual NRT, considered first-line treatment,47 was not tested. According to the a priori efficacy outcomes for the trial, the cutoff for biochemical verification of self-reported abstinence was CO ≤10ppm, though this may not capture light smoking. Pairwise comparisons in some subgroups are likely underpowered. For instance, in the PD sub-cohort, the corrected confidence intervals for efficacy for two of the active treatments against placebo include an odds ratio of 1; however, the point estimates are greater than two. In the psychiatric cohort as a whole, the group for which the study was powered, significant differences were observed for week 9-12 and 9-24 CARs for all active treatments vs. placebo. Our ability to evaluate comorbid SUD as a moderator was limited to those with a prior SUD, thus results may not extend to those with a current SUD.

Conclusion:

In adults with psychotic, anxiety, and mood disorders, 12 weeks of treatment with varenicline, bupropion, and NRT were well-tolerated during a smoking cessation attempt, and comparable to placebo. The preponderance of evidence suggests that in smokers with these psychiatric illnesses, consistent with relative efficacy reported in the general population, varenicline is associated with higher rates of smoking cessation than NRT or bupropion, and all three active treatments are associated with superior abstinence rates to placebo.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank David Schoenfeld, Professor of Biostatistics, Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health, for his statistical assistance.

The EAGLES study was funded by Pfizer and GlaxoSmithKline.

Funding Pfizer and GlaxoSmithKline

Author disclosures/conflicts of interest and sources of funding/support:

Dr. Evins has received research grant funding to her institution from Pfizer, Forum Pharmaceuticals, Brain Solutions LLC, and Alkermes, has served as an advisor to Alkermes, Reckett Benckizer and Pfizer. Support for writing this manuscript was provided by NIDA K24.

Dr. Benowitz is a consultant to Pfizer, Inc. and Achieve Life Sciences, companies that market or are developing smoking cessation medications, and has been a paid expert witness in litigation against tobacco companies.

Dr. West has received fees for consultancy and lectures, and research funding from Pfizer, Inc., Glaxo Smith Kline, Inc. (GSK) and Johnson & Johnson (J&J).

Dr. Russ is a current Pfizer, Inc. employee with both salary and company stock interests.

Dr. McRae is a current Pfizer, Inc. employee with both salary and company stock interests.

Dr. Lawrence is a current Pfizer, Inc. employee with both salary and company stock interests.

Mr. Krishen is an employee of PAREXEL International on behalf of Glaxo Smith Kline Inc (GSK), and a stockholder of GSK. There are no other relationships, conditions or circumstances that present a potential conflict of interest.

Dr. Aubin is a current Pfizer, Inc. employee with both salary and company stock interests.

Dr. Maravic has no conflicts of interest to report.

Dr. Anthenelli receives grants from Alkermes and Pfizer, Inc. and provides consulting and/or advisory board services to Arena Pharmaceuticals, Cerecor, Pfizer, and US WorldMeds. RMA’s writing of this manuscript was supported, in part, by National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism Grant #s U01 AA013641, and National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA) Grant # UO1 DA041731, and NIDA/Veterans Affairs Cooperative Study # 1033.

Footnotes

Portions of this manuscript were presented at the Society for Research on Nicotine and Tobacco Annual Meeting 2016, Chicago IL, USA and the Society for Research on Nicotine and Tobacco International Meeting 2017, Florence, Italy.

Trial registration clinicaltrials.gov identifier: NCT01456936

References Cited

- 1.Anthenelli RM, Morris C, Ramey TS, et al. Effects of varenicline on smoking cessation in adults with stably treated current or past major depression: A randomized trial. Ann Intern Med. 2013;159:390–400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chengappa KN, Perkins KA, Brar JS, et al. Varenicline for smoking cessation in bipolar disorder: A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. J Clin Psychiatry. 2014;75:765–772. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tsoi DT, Porwal M, Webster AC. Interventions for smoking cessation and reduction in individuals with schizophrenia. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013;2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Evins AE, Cather C, Deckersbach T, et al. A double-blind placebo-controlled trial of bupropion sustained-release for smoking cessation in schizophrenia. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2005;25:218–225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Evins AE, Cather C, Culhane MA, et al. A 12-week double-blind, placebo-controlled study of bupropion sr added to high-dose dual nicotine replacement therapy for smoking cessation or reduction in schizophrenia. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2007;27:380–386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Roberts E, Evins AE, McNeill A, et al. Efficacy and tolerability of pharmacotherapy for smoking cessation in adults with serious mental illness: A systematic review and network meta-analysis. Addiction. 2016;111:599–612. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gierisch JM, Bastian LA, Calhoun PS, et al. Smoking cessation interventions for patients with depression: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Gen Intern Med. 2011;27:351–360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Evins AE, Cather C, Pratt SA, et al. Maintenance treatment with varenicline for smoking cessation in patients with schizophrenia and bipolar disorder: A randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2014;311:145–154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Williams JM, Anthenelli RM, Morris CD, et al. A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study evaluating the safety and efficacy of varenicline for smoking cessation in patients with schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder. J Clin Psychiatry. 2012;73:654–660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hall SM, Tsoh JY, Prochaska JJ, et al. Treatment for cigarette smoking among depressed mental health outpatients: A randomized clinical trial. Am J Public Health. 2006;96:1808–1814. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cook BL, Wayne GF, Kafali EN, et al. Trends in smoking among adults with mental illness and association between mental health treatment and smoking cessation. JAMA. 2014;311:172–182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Smith PH, Mazure CM, McKee SA. Smoking and mental illness in the U.S. population. Tob Control. 2014;23:147–153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Harker K, Cheeseman H. The Stolen Years: The Mental Health and Smoking Action Report. London, United Kingdom: Action on Smoking and Health; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dickerson F, Schroeder J, Katsafanas E, et al. Cigarette smoking by patients with serious mental illness, 1999–2016: An increasing disparity. Psychiatr Serv. 2017;69:147–153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Federal Trade Commission. Federal Trade Commission Cigarette Report for 2013. Washington DC; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Olfson M, Gerhard T, Huang C, et al. Premature mortality among adults with schizophrenia in the United States. JAMA Psychiatry. 2015;72:1–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Callaghan RC, Veldhuizen S, Jeysingh T, et al. Patterns of tobacco-related mortality among individuals diagnosed with schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, or depression. J Psychiatr Res. 2014;48:102–110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tiihonen J, Lonnqvist J, Wahlbeck K, et al. 11-year follow-up of mortality in patients with schizophrenia: A population-based cohort study (FIN11 study). Lancet. 2009;374:620–627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Davies NM, Thomas KH. The Food and Drug Administration and varenicline: Should risk communication be improved? Addiction. 2017;112:555–558. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gaballa D, Drowos J, Hennekens CH. Smoking cessation: The urgent need for increased utilization of varenicline. Am J Med. 2017;130:389–391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Himelhoch S, Riddle J, Goldman HH. Barriers to implementing evidence-based smoking cessation practices in nine community mental health sites. Psychiatr Serv. 2014;65:75–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Huang Y, Lewis S, Britton J. Use of varenicline for smoking cessation treatment in UK primary care: An association rule mining analysis. BMC Public Health. 2014;14:1024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Leone FT, Evers-Casey S, Graden S, et al. Academic detailing interventions improve tobacco use treatment among physicians working in underserved communities. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2015;12:854–858. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Prochaska JJ, Reyes RS, Schroeder SA, et al. An online survey of tobacco use, intentions to quit, and cessation strategies among people living with bipolar disorder. Bipolar Disord. 2011;13:466–473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sheals K, Tombor I, McNeill A, et al. A mixed-method systematic review and meta-analysis of mental health professionals’ attitudes toward smoking and smoking cessation among people with mental illnesses. Addiction. 2016;111:1536–1553. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tulloch HE, Pipe AL, Clyde MJ, et al. The quit experience and concerns of smokers with psychiatric illness. Am J Prev Med. 2016;50:709–718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Williams JM, Miskimen T, Minsky S, et al. Increasing tobacco dependence treatment through continuing education training for behavioral health professionals. Psychiatr Serv. 2015;66:21–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pirie K, Peto R, Reeves GK, et al. The 21st century hazards of smoking and benefits of stopping: A prospective study of one million women in the UK. Lancet. 2013;381:133–141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jha P, Ramasundarahettige C, Landsman V, et al. 21st-century hazards of smoking and benefits of cessation in the United States. N Engl J Med. 2013;368:341–350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Anthenelli RM, Benowitz NL, West R, et al. Neuropsychiatric safety and efficacy of varenicline, bupropion, and nicotine patch in smokers with and without psychiatric disorders (EAGLES): A double-blind, randomised, placebo-controlled clinical trial. Lancet. 2016;387:2507–2520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Smith PH, Weinberger AH, Zhang J, et al. Sex differences in smoking cessation pharmacotherapy comparative efficacy: A network meta-analysis. Nicotine Tob Res. 2017;19:273–281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Schuster RM, Cather C, Pachas GN, et al. Predictors of tobacco abstinence in outpatient smokers with schizophrenia or bipolar disorder treated with varenicline and cognitive behavioral smoking cessation therapy. Addict Behav. 2017;71:89–95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Perkins KA, Scott J. Sex differences in long-term smoking cessation rates due to nicotine patch. Nicotine Tob Res. 2008;10:1245–1250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.First MB, Spitzer RL, Gibbon M, et al. Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV-TR Axis I Disorders, Research Version, Non-Patient Edition. New York, New York Biometrics Research, New York State Psychiatric Institute; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Guy W ECDEU Assessment Manual for Psychopharmacology. Washington, DC: US Department of Health, Education, and Welfare; 1976. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Fiore M, Jaen C, Baker T, et al. Treating tobacco use and dependence: 2008 update. Clinical Practice Guideline. Executive Summary. In: Services UDoHaH, ed. Rockville, Maryland: Public Health Service; 2008. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zigmond AS, Snaith RP. The hospital anxiety and depression scale. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 1983;67:361–370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Posner K, Brown GK, Stanley B, et al. The Columbia-Suicide Severity Rating Scale: Initial validity and internal consistency findings from three multisite studies with adolescents and adults. Am J Psychiatry. 2011;168:1266–1277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hughes JR, Keely JP, Niaura RS, et al. Measures of abstinence in clinical trials: Issues and recommendations. Nicotine Tob Res. 2003;5:13–25. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.First M, Gibbon M, Spitzer R, et al. Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis II Personality Disorders, (SCID-II). Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Press, Inc; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Fagerstrom K Determinants of tobacco use and renaming the FTND to the Fagerstrom Test for Cigarette Dependence. Nicotine Tob Res. 2012;14:75–78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Leventhal AM, Waters AJ, Boyd S, et al. Gender differences in acute tobacco withdrawal: Effects on subjective, cognitive, and physiological measures. Exp Clin Psychopharmacol. 2007;15:21–36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Weinberger AH, Gbedemah M, Goodwin RD. Cigarette smoking quit rates among adults with and without alcohol use disorders and heavy alcohol use, 2002–2015: A representative sample of the United States population. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2017;180:204–207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Marks JL, Hill EM, Pomerleau CS, et al. Nicotine dependence and withdrawal in alcoholic and nonalcoholic ever-smokers. J Subst Abuse Treat. 1997;14:521–527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Strong DR, Cameron A, Feuer S, et al. Single versus recurrent depression history: Differentiating risk factors among current US smokers. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2010;109:90–95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.McClave AK, McKnight-Eily LR, Davis SP, et al. Smoking characteristics of adults with selected lifetime mental illnesses: Results from the 2007 National Health Interview Survey. Am J Public Health. 2010;100:2464–2472. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Cahill K, Stevens S, Lancaster T. Pharmacological treatments for smoking cessation. JAMA. 2014;311:193–194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Buchanan RW, Kreyenbuhl J, Kelly DL, et al. The 2009 schizophrenia PORT psychopharmacological treatment recommendations and summary statements. Schizophr Bull. 2010;36:71–93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Evins AE, Cather C, Laffer A. Treatment of tobacco use disorders in smokers with serious mental illness: Toward clinical best practices. A systematic reveiw of the evidence. Harv Rev of Psychiatry. 2015;23:90–98. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Tidey JW, Miller ME. Smoking cessation and reduction in people with chronic mental illness. BMJ. 2015;351:1–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Prochaska JJ, Hall SM, Tsoh JY, et al. Treating tobacco dependence in clinically depressed smokers: Effect of smoking cessation on mental health functioning. Am J Public Health. 2008;98:446–448. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Hall SM. Nicotine interventions with comorbid populations. Am J Prev Med. 2007;33:S406–413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.