Abstract

Intramuscular collagen may affect the value of meat by limiting its tenderness and cooking convenience. Production factors such as age of animal at slaughter, the use of steroids and beta-adrenergic agonists as growth promotants, and cattle breed may affect the contribution of collagen to beef quality. Recent research has indicated that concentrations of the mature collagen cross-link pyridinoline (PYR) are positively correlated with Warner-Bratzler shear force (WBSF) and animal age at slaughter, while contribution of the concentration of a second mature collagen cross-link Ehrlich’s Chromogen (EC) to beef toughness declines with cattle age. Cattle breed influences total collagen content of muscle due to differing rates of maturation among breeds. Growth promoting technologies do not appear to affect collagen solubility, but do influence PYR and EC densities and concentrations in some beef muscles. Concentrations of PYR and EC do not account for all the variation in collagen heat solubility in beef muscles, nor do advanced glycation end products given the relative immaturity of cattle at slaughter. In light of this, other collagen cross-links such as heat-stable divalent cross-links may warrant reconsideration with regard to their contribution to cooked beef toughness.

Keywords: beef, collagen solubility, Ehrlich’s Chromogen, pyridinoline

INTRODUCTION

Collagen is one of the most abundant proteins in the mammalian body, being the primary protein of skeletal and muscle connective tissues. Collagen is the main protein of cartilage, tendon, and bone, connecting bones and muscle throughout the vertebrate body and conducting the movement from muscle fibers to the tendons to effect movement through lever action. Its ubiquity is enabled through its many different structures, with there being at present 28 different types of collagen characterized (Shoulders and Raines, 2009). Collagen proteins display 3 distinguishing features: first, they are triple helical, consisting of 3 left-handed helical α-chains combined into a right-handed triple helix. Second, they contain hydroxyproline, an imino acid resulting from a post-translational modification by lysyl hydroxylase of proline within the collagen α-chain, which stabilizes each α-chain by conferring increased thermal stability with its concentration. Third, glycine is almost every third amino acid in the helical portion of the molecule, as it is the smallest amino acid and thus allows for the tight turn of each α-chain to accommodate the triple helix structure (Shoulders and Raines, 2009). Collagens are synthesized intracellularly in the endoplasmic reticulum like other proteins and then are secreted extracellularly as procollagens once the formation of the triple helix is complete (Myllyharju and Kivirikko, 2004). The N and C procollagen propeptides are clipped by N and C endopeptidases prior to each molecule self-assembling into a connective tissue structure that is stabilized by covalent cross-links between adjacent collagen molecules through lysine aldehydes formed by lysyl oxidase (Holmes et al., 2018). A large proportion of collagen cross-links are divalent in young animals (Horgan et al., 1990) and in newly formed connective tissue (Robins et al., 1973). Divalent cross-links have been postulated to condense with lysine and hydroxylysine in neighboring α-chains to form trivalent cross-links (Eyre and Wu, 2005). Two trivalent collagen cross-links have been characterized, specifically pyridinoline (PYR) and Ehrlich’s Chromogen (EC), and as its name suggests, PYR contains a pyridine, 6-sided ring, while EC contains a pyrrole, 5-sided ring. Each cross-link connects 3 collagen α-chains, and increasing concentrations of PYR and EC have been associated with increasing thermal denaturation temperature (Horgan et al., 1990).

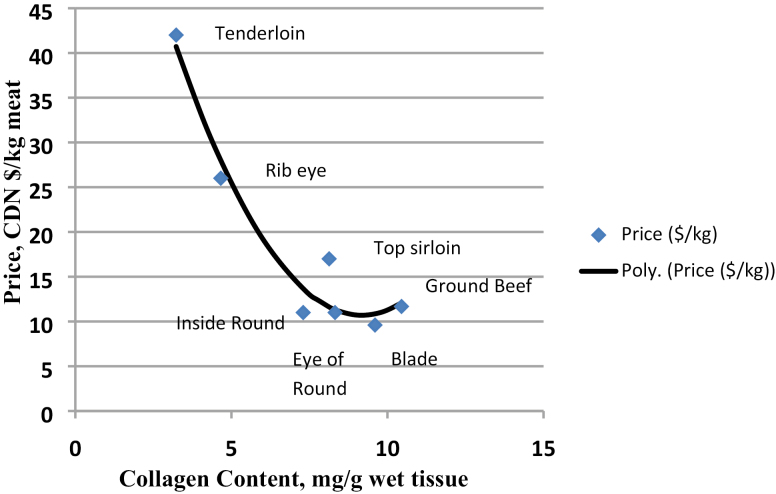

Collagen is found throughout skeletal muscle as a constituent of the epimysium, perimysium, and endomysium, and the concentration of intramuscular collagen from the perimysium and endomysium drives the value of meat from food animals that are relatively mature at slaughter. For beef, which is an example of a food animal that is postpubertal at slaughter, a strong polynomial relationship (R2 = 0.95) exists between price/kg of beef and collagen content (mg/g wet tissue, from McKeith et al., 1985; Fig. 1), indicating that increased collagen content is related to a perception of low value in the market as collagen reduces the ability of consumers to grill and eat the product quickly. Collagen, therefore, can be related to cooked beef toughness through either its concentration, with increased concentration of collagen associated with increased cooked beef toughness (Ngapo et al., 2002), or through the heat resistance and stability of the cross-links formed within it, with the cooked beef toughness increasing as the concentration of heat stable cross-links increases and the heat solubility of the collagen decreases (Girard et al., 2011, 2012). As a result, it would be advantageous for beef producers to be able to minimize the contribution of collagen concentration and cross-linking to beef toughness through modification of production practices. Collagen concentration and cross-link types may be affected by age at slaughter, growth rate, the use of steroids and ractopamine (RAC), breed and genetics, and muscle type, and to understand how to mitigate the effects of these common production practices, their effects on collagen will be reviewed.

Figure 1.

Relationship between collagen content (McKeith et al. 1985) of a beef cut and its value in Canadian (CDN) dollars per kg of meat (beef prices as per June 28, 2018, www.realcanadiansuperstore.ca).

PRODUCTION FACTORS AFFECTING INTRAMUSCULAR COLLAGEN CHARACTERISTICS

Age at Slaughter

It is well known that connective tissue toughness of high connective tissue muscles increases with beef cattle age (Shorthose and Harris, 1990), with collagen heat solubility decreasing with cattle age in Hill (1966). Recent research in our laboratory (Girard et al., 2011, 2012) investigated the effect of animal age at slaughter (calf-fed 12 to 13 mo old vs. yearling-fed 18 to 20 mo old at slaughter), steroid use (control vs. treated), RAC supplementation (control vs. treated), and breed [Hereford × Aberdeen Angus (HAA) vs. Charolais × Red Angus (CRA)] on the quality of the semitendinosus (ST) and gluteus medius (GM) muscles from steer carcasses. Girard et al. (2011) showed that the heat solubility of collagen decreased (P < 0.05) in the GM, more so than in the ST (P < 0.10), suggesting that the chronology of cross-link formation in bovine intramuscular collagen differed between muscles. Girard et al. (2011) also showed that total collagen increased in the GM but not the ST with steer age, indicating that collagen accretion with age varied by muscle. Intramuscular collagen content has been shown to increase through mechanotransduction, where both work load associated with increased body weight and passive stretch resulting from the lengthening of bone during growth can both contribute to increased collagen synthesis and accumulation, with the effect most pronounced in muscles where red muscle fibers predominate (Kjær, 2004).

That total collagen content increased and collagen solubility decreased in the GM of Girard et al. (2011) suggested that mechanotransduction forces predominated in the GM and changed the collagen cross-link profile as well to lead to reduced collagen solubility. Interestingly, the mature collagen cross-links PYR and EC concentrations were not affected by age or correlated to collagen solubility in the GM in the Girard et al. (2011) study as shown by Roy et al. (2015), indicating that the concentrations of PYR and EC did not entirely account for changes in collagen solubility related to age in this muscle. This lack of relationship between PYR and collagen solubility has been observed by others (Young et al., 1994) and in the GM in a subsequent experiment in our laboratory (Roy et al., 2018, personal communication), with PYR increasing with cattle age with no concomitant decrease in collagen solubility until cattle were approximately 5 yr of age. In subsequent experimentation (Roy et al., personal communication), PYR was related to collagen solubility in the ST as well, with PYR concentration significantly greater and collagen solubility significantly reduced in the muscle of cows with an average age of 5 yr than in muscle from steers less than 20 mo of age. Large ranges in animal ages and maturities appear to be required to observe the increase in intramuscular PYR with age in cattle as the density of the cross-link appears to change slowly (Horgan et al., 1991). Palokangas et al. (1992) showed in rats that intramuscular collagen PYR concentration increased substantially within the first 4 mo, but rats are more immature at birth than cattle, and so this increase may occur in cattle prenatally. Palokangas et al., (1992) also concluded that the concentration of PYR at any age was related to muscle function rather than muscle fiber type, with slow-twitch postural muscles having the highest intramuscular PYR concentrations. Although the PYR concentrations in the GM and ST were not directly compared by Roy et al. (2015), they did not appear to differ, which may be unexpected given the difference in function, but the presence of elastin in the ST may affect the requirement for PYR in the ST.

Notably, in the same subsequent experiment in our laboratory (Roy et al., personal communication), which compared the GM and ST of carcasses from steers with average ages of 11 and 20 mo with that of carcasses of cows with an average age of 5 yr, EC concentrations in both muscles decreased with cattle age, being significantly less in the muscles of cows with an average age of 5 yr than in the muscles of steers with an average age of either 11 or 20 mo. These results were in agreement with those of Horgan et al., (1991) who also observed a decrease in intramuscular collagen EC concentrations with animal age in the m. longissimus thoracis et lumborum from the carcasses of goats that ranged in age from 1 d to 13 yr. Why the concentration of EC decreases in intramuscular collagen is unclear, but Horgan et al., (1991) postulated that it may be that the EC cross-link progressively lost its ability to be detected using the Ehrlich’s reagent (p-dimethylaminobenzaldehyde) through further reaction of its pyrrole ring over time in situ.

Three additional intramuscular connective tissue cross-links have been identified as potentially contributing to muscle strength and connective tissue stiffness due to age: glycosepane (Sell et al., 2005), arginoline (Eyre et al., 2010), and pentosidine (Avery et al., 1996; Haus et al., 2007). All are considered to be advanced glycation end products, of which glycosepane is the most common, and result from a Schiff-base reaction between glucose and lysine in different collagen molecules that stabilize into a keto amine (Snedeker and Gautieri, 2014). These cross-links are notable in that once formed they cannot be broken in vivo, and may impair the ability of intrinsic collagenases to turnover collagen involved in them (Reddy, 2004). These cross-links are unlikely to contribute to cooked beef toughness in young cattle, but may influence the toughness of beef from mature cattle. Study of the chemical structures of these cross-links also indicates that these cross-links are unlikely to be products of further reaction of the EC cross-link, as none contain a pyrrole ring. Pentosidine appears to be based upon a purine ring, while glycosepane contains a piperidine ring and arginoline contains an imidazole ring.

Steroidal Implants

Steroidal implants have been associated with increased toughness of cooked beef m. longissimus lumborum (Foutz et al., 1997; Faucitano et al., 2008; Ebarb et al., 2016, 2017) although not consistently (Cranwell et al., 1996; Kerth et al., 2003). Girard et al. (2012) showed no effect of steroid implants on the Warner-Bratzler shear force (WBSF) of the GM, but an increase in WBSF in the ST. Regardless of the effect of steroid implants on the WBSF, Girard et al. (2011) showed no effect of steroidal implants on intramuscular collagen content of the ST or GM, and steroidal implants did not affect the heat solubility of the collagen in either muscle. These results agree with those of Ebarb et al. (2016) who showed no effect of growth promoting technologies on collagen solubility. Despite no effects on total collagen contents and collagen heat solubility in either the ST or GM in the Girard et al. (2011) study, concentrations of PYR and EC cross-links were affected by the use of steroidal growth promotants in the same cattle. Roy et al. (2015) observed that PYR and EC densities increased in the GM muscle of implanted steers and that the concentration of PYR in yearling-fed cattle was increased in HAA cattle that were implanted. Roy et al. (2015) postulated that the use of steroids in cattle may increase the concentration of PYR and EC through suppression of matrix metalloproteinase (MMP) activity by inducing expression of the transcription factor nuclear factor kappa-β (NF-κβ) (Chevronnay et al., 2012) through increased expression of interleukin (IL)-1β (Montaseri et al., 2011). Insulin-like growth factor-1 (IGF-1), the operative growth factor associated with steroids (Johnson et al., 1998), has however been associated with increased collagen synthesis and decreased collagen maturity (Reiser et al., 1996), suggesting that mechanisms other than inhibition of MMP were involved.

These changes observed by Roy et al. (2015), although not affecting other collagen phenotypic measurements, indicated purposeful formation of EC and PYR within the GM of cattle receiving steroid implants, as the densities of both mature cross-links increased with steroid use. This implied that any new collagen synthesized in cattle with steroid implants had PYR and EC cross-links established preferentially, which contrasts with the premise that mature collagen cross-links form randomly due to condensation reactions between closely situated divalent cross-links and helical or telopeptidyl lysines and hydroxylysines with time in situ. Such preferential and purposeful cross-link formation would require either upregulation of lysyl hydroxylase 1 (LH1), which hydroxylates lysine in the collagen helix and enables the formation of EC and PYR cross-links, or upregulation of lysyl hydroxylase 2b (LH2b), which preferentially hydroxylates lysines in the telopeptides of Type I collagen, enabling formation of PYR (Eyre and Wu, 2005; Yamauchi and Sricholpech, 2012). Transforming growth factor β1 (TGFβ1) is known to increase both collagen synthesis and PYR density (van der Slot et al., 2005; Gjaltema et al., 2015). The results of Roy et al., (2015) do not preclude LH2b expression being increased, but LH2 is the only LH that is responsive to TGFβ1 (Gjaltema et al., 2015) and so an increase in PYR due to increased expression of LH2b would likely not be accompanied by an increase in EC as formation of the hydroxylysylpyrrole would require hydroxylation of the helix lysines (Eyre and Wu, 2005).

Another known regulator of lysyl hydroxylase activity is pituitary homeobox 2 (PITX2; Hjalt et al., 2001; Cox et al., 2002), which is upregulated in activated satellite cells (Lhonore et al., 2018). Steroids have been shown to increase satellite cell numbers in bovine muscle cell systems (Johnson et al., 1998); therefore, it is possible that PITX2 upregulation in the activated satellite cells may upregulate both LH1 and 2, and promote the simultaneous formation of PYR and EC in cattle implanted with steroids. That there was no concomitant increase in total intramuscular collagen with the use of steroids suggested that TGFβ1 may not have been the operative growth factor involved in the collagen cross-link formation observed by Roy et al. (2015). The promotion of satellite cell activation however, has been associated with IGF-1 (Johnson et al., 1998) while TGFβ promotes satellite cell quiescence and differentiation (Delaney et al., 2017).

Ractopamine

Unlike in beef steers implanted with steroid growth promotants, supplementation of beef steers with RAC decreased PYR density in the GM and increased EC in the ST (Girard et al., 2011), suggesting that RAC increased synthesis of new collagen along with the synthesis and deposition of new muscle protein. Although total collagen per gram of GM muscle did not change with RAC administration, the density of PYR was lowered in the GM, suggesting that newly synthesized collagen cross-linked with divalent cross-links was deposited in the GM in response to RAC supplementation. Roy et al. (2015) suggested that collagen synthesis was promoted by RAC through the TGFβ1 pathway, but this pathway preferentially establishes PYR (Gjaltema et al., 2015) and thus increases rather than decreases PYR density. The beta-agonist RAC, however, is used just prior to slaughter and insufficient time may have elapsed after collagen synthesis for the formation of PYR cross-links in the muscle of RAC-supplemented cattle to occur, precluding an accurate estimate of the level of telopeptide lysine hydroxylation.

The increase in EC in the ST (Roy et al., 2015) with RAC supplementation suggested that LH1 was the operative LH in the modification of newly synthesized collagen, as LH1 preferentially hydroxylates lysines in the helix (Yamauchi and Sricholpech, 2012) and helix hydroxylysines are necessary for the formation of the lysyl and hydroxylysyl pyrroles (Eyre and Wu, 2005). What would provoke increased expression of LH1 only is not known, as TGFβ1 increases PYR cross-link density through preferential expression of LH2b (Gjaltema et al., 2015). Also, beta-agonists have been shown to not affect circulating level of IGF-1 (Winterholler et al., 2008) or to decrease it (Johnson et al., 2014) and to not increase satellite cell proliferation, thus discouraging implication of PITX2 as the promoter of LH1 expression. Little research appears available investigating regulation of the expression of LH1 or the effects of LH expression on EC, although knockout mice models indicated that reduction in LH1 expression reduces PYR formation profoundly (Takaluoma et al., 2007).

As postulated by Roy et al. (2015), preferential disposition of EC in the ST may occur through the circulating cyclic adenosine monophosphate (cAMP) response element binding protein (CREB) binding protein (CRP1)—P300 transcriptional coactivating protein complex. Increased expression of LH2b via the TGF-β1 pathway does not require the CRP-1/P300 complex binding to the SMAD2-SMAD3-SMAD4 complex (Gjaltema et al., 2015), so the role of the CRP-1/p300 complex is unclear, but may be related to expression of LH1. Notably, IGF-1 is associated with increased synthesis of intramuscular collagen (Doessing et al., 2010), and a decrease in IGF-1 in response to beta-agonist administration may reduce the synthesis of collagen relative to myofibrillar protein synthesis.

Breed

Roy et al. (2015) showed that the amount of perimysium in the ST varied with breed, with the HAA having more mg perimysium per g of muscle, which resulted in an increased PYR concentration in the muscle as well. As indicated by Roy et al. (2015), the difference in perimysium collagen content may have been indicative of the difference in physiological maturity of the 2 crossbreeds, with the HAA crossbred anticipated to be more physiologically advanced at the same chronological age due to British breeds maturing earlier than those considered Continental European (Arango et al., 2002). Others have shown no differences in total collagen content in muscles between beef breeds (Martins et al., 2015), although results of a large meta-analysis by Blanco et al. (2013) supported differences in total collagen among breeds based upon physiological maturity.

Roy et al. (2015) also noted that the concentration of EC in the ST was decreased in yearling CRA that received RAC relative to CRA that were not supplemented with RAC and yearling HAA that did receive RAC. Why this occurred was unclear, but again may indicate that much of the collagen deposited was newly synthesized and cross-linked with immature, divalent cross-links. Characterization of how deposition of EC is regulated by LH1 clearly requires additional research, as PYR rather than EC is at present the priority of connective tissue researchers given the substantial role of PYR in fibrosis and its impact on human health through the mechanical failure of affected skeletal and cardiac tissues.

FUTURE RESEARCH

Subsequent research in our laboratory investigating the GM from carcasses of calf-fed and yearling-fed steers and mature cows has shown that collagen solubility decreases with age without significant effect on Warner-Bratzler shear force (Roy et al., personal communication). The Warner-Bratzler shear force method has been shown to be less sensitive to the influence of connective tissue than compression measurements (Bouton et al., 1978). Christensen et al. (2011) also showed no correlations between Warner-Bratzler shear force and collagen characteristics for the m. longissimus thoracis. In contrast to this, Girard et al. (2012) showed that peak Warner-Bratzler shear force values were correlated to heat soluble collagen in the GM (r = −0.32, P < 0.0002), but not the ST unless the connective tissue peak of the Warner-Bratzler shear force deformation curve was considered (r = −0.31, P < 0.0002). Interestingly, Girard et al. (2012) cooked experimental beef samples quickly using a grill to 71 °C, while the studies of Bouton et al., (1978), Christensen et al., (2011) and that most recently performed in our laboratory (Roy et al., personal communication) cooked their beef samples slowly to 80, 75, and 71 °C, respectively, using a water bath immersion method. It is unlikely that any effect of collagen would be observed on Warner-Bratzler shear force by Bouton et al., (1978), Christensen et al., (2011), or in our recent research (Roy et al., personal communication) given that all collagen in the muscle would have been gelatinized by prolonged cooking above 65 °C (Bozec and Odlyha, 2011). The contribution of collagen can be apparent even in muscles considered to have moderate collagen content when cooked with a grill. Ebarb et al. (2016), who used a grill to cook m. longissimus lumborum steaks, showed that the correlations between total collagen (r = 0.54, P < 0.01) and insoluble collagen (r = 0.49, P < 0.01) and Warner-Bratzler shear force of those steaks became apparent after 21 d of postmortem aging. The results of Ebarb et al. (2016) and Girard et al. (2012) substantiate that the contribution of collagen to cooked beef toughness is relevant even in bovine muscles considered to have low concentrations of intramuscular collagen when the muscle is grilled quickly.

The recent results in our laboratory (Roy et al., personal communication) substantiated the findings of Roy et al. (2015) that EC is not associated with age-related toughening of beef although PYR is. Not all the variation in age-related toughness of beef is accounted for by PYR concentration (Roy et al., 2015), suggesting that other cross-links are contributing to this toughness. Oxlund et al. (1996) showed that the concentrations of PYR between osteoporotic and nonosteoporotic bones were not different, although the mechanical strength of the bone was, with osteoporotic bone not as strong as nonosteoporotic bone. Oxlund et al. (1996) showed, however, that the concentrations of divalent collagen cross-links were lowest in osteoporotic bone. The reduced form of the divalent collagen cross-link de-hydrodihydroxy-lysinonorleucine (DeH-DHLNL), specifically dihydroxylysinonorleucine (DHLNL), has been positively correlated along with PYR with increasing connective tissue mechanical strength in native cervical connective tissue (Yoshida et al., 2014). Mechanical properties observed in raw bovine connective tissue do not necessarily reflect those of the tissue when it is cooked beef (Christensen et al., 2011); therefore, for divalent cross-links to contribute to beef toughness, their mechanical strength in the native state must persist after cooking. The cross-link deH-DHLNL has been shown to be heat stable, remaining detectable after connective tissue has been heated at 80 °C for 3 h (Jackson et al., 1974), as has the divalent cross-link hydroxylysinonorleucine (HLNL) (Jackson et al., 1974; Mechanic 1974). DeH-DHLNL is the precursor to deoxy-PYR, the most common form of PYR in bone, but the density of DHLNL (mol/mol collagen) in intramuscular collagen was shown by Ngapo et al. (2002) to be negatively correlated with the WBSF of m. gluteobiceps cooked to 75 °C for 1 h and not correlated with WBSF when the same muscle was grilled to 80 °C. This is unexpected given that DHLNL is heat stable, but deoxy-PYR is not the predominant form of PYR in intramuscular collagen, and so DHLNL is present at very low levels in intramuscular collagen (Ngapo et al., 2002). Ngapo et al. (2002) showed that HLNL density (mol/mol collagen) and muscle concentration (nmol/g muscle) were correlated with WBSF of grilled m. gluteobiceps. The same researchers however showed no relationships between collagen divalent and trivalent cross-links in the ST; rather total collagen content in the ST was correlated with WBSF, suggesting that the relationships between collagen cross-links and WBSF were muscle specific.

Another immature collagen cross-link histidinohydroxymerodesmosine (HHMD), recently shown to be an artifact of sodium borohydride reduction (Eyre et al., 2019), was positively correlated with WBSF of m. gluteobiceps grilled to 80 °C by Ngapo et al. (2002), but was not linearly associated with WBSF in the same muscle cooked to 75 °C in a water bath for 1 h. Jackson et al. (1974) showed that HHMD was not heat stable in connective tissue heated at 80 °C for 3 h, so its heat lability at 75 °C at 1 h is not unexpected. Based upon the results of Ngapo et al. (2002), however, the aldimine cross-link from which HHMD is derived contributes to cooked beef toughness in some muscles when the beef is cooked quickly, and it may warrant reconsideration as a cross-link that contributes to the toughness of grilled beef.

SUMMARY AND CONCLUSIONS

Beef cattle breed and animal age at slaughter affect collagen characteristics the most, with beef producers targeting guaranteed tenderness programs potentially benefiting from reducing cattle age at slaughter. Beef producers targeting guaranteed tenderness programs for beef may also wish to consider not using steroid growth promotants, which may increase PYR in intramuscular collagen. Understanding the contribution of divalent heat stable collagen cross-links would allow for improved understanding of the effects of production factors on the contribution of collagen to beef connective tissue structure and ultimately its influence on cooked beef toughness.

Footnotes

The authors gratefully acknowledge financial support for their research from Alberta Beef Producers, the Beef Cattle Research Council, Agricultural Funding Consortium, Alberta Livestock and Meat Agency, and Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada.

Based on presentation given at the Meat Science and Muscle Biology Symposium: Biological Influencers of Meat Palatability titled “Production factors affecting the contribution of collagen to meat toughness” at the 2018 Annual Meeting of the American Society of Animal Science held in Vancouver, BC, Canada, July 8–12, with publication sponsored by the Journal of Animal Science and the American Society of Animal Science.

LITERATURE CITED

- Arango J. A., L. V. Cundiff, and Van Vleck L. D.. 2002. Breed comparisons of angus, charolais, hereford, jersey, limousin, simmental, and south devon for weight, weight adjusted for body condition score, height, and body condition score of cows. J. Anim. Sci. 80:3123–3132. doi:10.2527/2002.80123123x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Avery N. C., T. J. Sims C. Warkup, and Bailey A. J.. 1996. Collagen cross-linking in porcine m. Longissimus lumborum: Absence of a relationship with variation in texture at pork weight. Meat Sci. 42:355–369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blanco M., C. Jurie D. Micol J. Agabriel B. Picard, and Garcia-Launay F.. 2013. Impact of animal and management factors on collagen characteristics in beef: A meta-analysis approach. Animal. 7:1208–1218. doi:10.1017/S1751731113000177 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bouton P. E., A. L. Ford P. V. Harris W. R. Shorthose D. Ratcliff, and Morgan J. H.. 1978. Influence of animal age on the tenderness of beef: Muscle differences. Meat Sci. 2:301–311. doi:10.1016/0309-1740(78)90031-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bozec L., and Odlyha M.. 2011. Thermal denaturation studies of collagen by microthermal analysis and atomic force microscopy. Biophys. J. 101:228–236. doi:10.1016/j.bpj.2011.04.033 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chevronnay H. P. G., C. Selvais H. Emonard C. Galant E. Marbaix, and Henriet P.. 2012. Regulation of matrix metalloproteinases activity studied in human endometrium as a paradigm of cyclic tissue breakdown and regeneration. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1824:146–156. doi:10.1016/j.bbapap.2011.09.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christensen M., P., Ertbjerg S., Failla C., Sañudo R. I., Richardson G. R., Nute J. L., Olleta B., Panea P., Albertí M., Juárez, et al. 2011. Relationship between collagen characteristics, lipid content and raw and cooked texture of meat from young bulls of fifteen European breeds. Meat Sci. 87:61–65. doi:10.1016/j.meatsci.2010.09.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cox C. J., H. M. Espinoza B. McWilliams K. Chappell L. Morton T. A. Hjalt E. V. Semina, and Amendt B. A.. 2002. Differential regulation of gene expression by PITX2 isoforms. J. Biol. Chem. 277:25001–25010. doi:10.1074/jbc.M201737200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cranwell C. D., J. A. Unruh J. R. Brethour, and Simms D. D.. 1996. Influence of steroid implants and concentrate feeding on carcass and longissimus muscle sensory and collagen characteristics of cull beef cows. J. Anim. Sci. 74:1777–1783. doi:10.2527/1996.7481777x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delaney K., P. Kasprzycka M. A. Ciemerych, and Zimowska M.. 2017. The role of TGF-β1 during skeletal muscle regeneration. Cell Biol. Int. 41:706–715. doi:10.1002/cbin.10725 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doessing S., K. M., Heinemeier L., Holm A. L., Mackey P., Schjerling M., Rennie K., Smith S., Reitelseder A. M., Kappelgaard M. H., Rasmussen, et al. 2010. Growth hormone stimulates the collagen synthesis in human tendon and skeletal muscle without affecting myofibrillar protein synthesis. J. Physiol. 588(Pt 2):341–351. doi:10.1113/jphysiol.2009.179325 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ebarb S. M., J. S. Drouillard K. R. Maddock-Carlin K. J. Phelps M. A. Vaughn D. D. Burnett C. L. Van Bibber-Krueger C. B. Paulk D. M. Grieger, and Gonzalez J. M.. 2016. Effect of growth-promoting technologies on longissimus lumborum muscle fiber morphometrics, collagen solubility, and cooked meat tenderness. J. Anim. Sci. 94:869–881. doi:10.2527/jas.2015-9888 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ebarb S. M., K. J., Phelps J. S., Drouillard K. R., Maddock-Carlin M. A., Vaughn D. D., Burnett J. A., Noel C. L., Van Bibber-Krueger C. B., Paulk D. M., Grieger, et al. 2017. Effects of anabolic implants and ractopamine-hcl on muscle fiber morphometrics, collagen solubility, and tenderness of beef longissimus lumborum steaks. J. Anim. Sci. 95:1219–1231. doi:10.2527/jas.2016.1263 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eyre D. R., Weis M., and Rai J.. 2019. Analyses of lysine aldehyde cross-linking in collagen reveal that the mature cross-link histidinohydroxylysinonorleucine is an artifact. J. Biol. Chem. In press. doi:10.1074/jbc.RA118.007202 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eyre D. R., M. A. Weis, and Wu J. J.. 2010. Maturation of collagen ketoimine cross-links by an alternative mechanism to pyridinoline formation in cartilage. J. Biol. Chem. 285:16675–16682. doi:10.1074/jbc.M110.111534 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eyre D. R., and Wu J-J.. 2005. Collagen cross-links. Top. Curr. Chem. 247:207–229. doi:10.1007/b103828 [Google Scholar]

- Faucitano L., P. Y. Chouinard J. Fortin I. B. Mandell C. Lafrenière C. L. Girard, and Berthiaume R.. 2008. Comparison of alternative beef production systems based on forage finishing or grain-forage diets with or without growth promotants: 2. Meat quality, fatty acid composition, and overall palatability. J. Anim. Sci. 86:1678–1689. doi:10.2527/jas.2007-0756 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foutz C. P., H. G. Dolezal T. L. Gardner D. R. Gill J. L. Hensley, and Morgan J. B.. 1997. Anabolic implant effects on steer performance, carcass traits, subprimal yields, and longissimus muscle properties. J. Anim. Sci. 75:1256–1265. doi:10.2527/1997.7551256x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Girard I., Aalhus J. L., Basarab J. A., Larsen I. L., and Bruce H. L.. 2011. Modification of muscle inherent properties through age at slaughter, growth promotants and breed crosses. Can. J. Anim. Sci. 91: 635–648. doi:10.4141/cjas2011-058 [Google Scholar]

- Girard I., H. L. Bruce J. A. Basarab I. L. Larsen, and Aalhus J. L.. 2012. Contribution of myofibrillar and connective tissue components to the Warner-Bratzler shear force of cooked beef. Meat Sci. 92:775–782. doi:10.1016/j.meatsci.2012.06.037 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gjaltema R. A., S. de Rond M. G. Rots, and Bank R. A.. 2015. Procollagen lysyl hydroxylase 2 expression is regulated by an alternative downstream transforming growth factor β-1 activation mechanism. J. Biol. Chem. 290:28465–28476. doi:10.1074/jbc.M114.634311 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haus J. M., J. A. Carrithers S. W. Trappe, and Trappe T. A.. 2007. Collagen, cross-linking, and advanced glycation end products in aging human skeletal muscle. J. Appl. Physiol. (1985). 103:2068–2076. doi:10.1152/japplphysiol.00670.2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hill F. 1966. The solubility of intramuscular collagen in meat animals of various ages. J. Food Sci. 31:161–166. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2621.1966.tb00472.x [Google Scholar]

- Hjalt T. A., B. A. Amendt, and Murray J. C.. 2001. PITX2 regulates procollagen lysyl hydroxylase (PLOD) gene expression: Implications for the pathology of rieger syndrome. J. Cell Biol. 152:545–552. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holmes D. F., Y. Lu T. Starborg, and Kadler K. E.. 2018. Collagen fibril assembly and function. Curr. Top. Dev. Biol. 130:107–142. doi:10.1016/bs.ctdb.2018.02.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horgan D. J., P. N. Jones N. L. King L. B. Kurth, and Kuypers R.. 1991. The relationship between animal age and the thermal stability and cross-link content of collagen from five goat muscles. Meat Sci. 29:251–262. doi:10.1016/0309-1740(91)90054-T [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horgan D. J., N. L. King L. B. Kurth, and Kuypers R.. 1990. Collagen crosslinks and their relationship to the thermal properties of calf tendons. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 281:21–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jackson D. S., Ayad S., and Mechanic G.. 1974. Effect of heat on some collagen cross-links. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 336: 100–107. doi:10.1016/0005-2795(74)90388-2 [Google Scholar]

- Johnson B. J., N. Halstead M. E. White M. R. Hathaway A. DiCostanzo, and Dayton W. R.. 1998. Activation state of muscle satellite cells isolated from steers implanted with a combined trenbolone acetate and estradiol implant. J. Anim. Sci. 76:2779–2786. doi:10.2527/1998.76112779x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson B. J., S. B. Smith, and Chung K. Y.. 2014. Historical overview of the effect of β-adrenergic agonists on beef cattle production. Asian-Australas. J. Anim. Sci. 27:757–766. doi:10.5713/ajas.2012.12524 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kerth C. R., J. L. Montgomery K. J. Morrow M. L. Galyean, and Miller M. F.. 2003. Protein turnover and sensory traits of longissimus muscle from implanted and nonimplanted heifers. J. Anim. Sci. 81:1728–1735. doi:10.2527/2003.8171728x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kjær M. 2004. Role of extracellular matrix in adaptation of tendon and skeletal muscle to mechanical loading. Physiol. Rev. 84:649–698. doi:10.1152/physrev.00031.2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lhonore A., Commère P-H., Negroni E., Pallafacchina G., Friguet B., Drouin J., Buckingham M., and Montarras D.. 2018. The role of Pitx2 and Pitx3 in muscle stem cells gives new insights into P38α MAP kinase and redox regulation of muscle regeneration. eLife. 7:e32991, doi: 10.7554/eLife.32991 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martins T. S., L. M., Sanglard W., Silva M. L., Chizzotti L. N., Rennó N. V., Serão F. F., Silva S. E., Guimarães M. M., Ladeira M. V., Dodson, et al. 2015. Molecular factors underlying the deposition of intramuscular fat and collagen in skeletal muscle of Nellore and Angus cattle. Plos One. 10:e0139943. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0139943 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKeith F. K., De Vol D. L., Miles S., Bechtel P. J., and Carr T. R.. 1985. Chemical and sensory properties of thirteen major beef muscles. J. Food Sci. 50: 869–872. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2621.1985.tb12968.x [Google Scholar]

- Mechanic G. L. 1974. Collagen crosslinks: Direct evidence of a reducible stable form of the schiff base delta-6 dehydro-5,5-dihydroxylysinonorleucine as 5-keto-5’hydroxylysinonorleucine in bone collagen. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 56:923–927. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montaseri A., F. Busch A. Mobasheri C. Buhrmann C. Aldinger J. S. Rad, and Shakibaei M.. 2011. IGF-1 and PDGF-bb suppress IL-1β-induced cartilage degradation through down-regulation of NF-κb signaling: Involvement of src/PI-3K/AKT pathway. Plos One. 6:e28663. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0028663 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Myllyharju J., and Kivirikko K. I.. 2004. Collagens, modifying enzymes and their mutations in humans, flies and worms. Trends Genet. 20:33–43. doi:10.1016/j.tig.2003.11.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ngapo T. M., P. Berge J. Culioli E. Dransfield S. De Smet, and Claeys E.. 2002. Perimysial collagen crosslinking and meat tenderness in Belgian blue double-muscled cattle. Meat Sci. 61:91–102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oxlund H., L. Mosekilde, and Ortoft G.. 1996. Reduced concentration of collagen reducible cross links in human trabecular bone with respect to age and osteoporosis. Bone. 19:479–484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palokangas H., V. Kovanen A. Duncan, and Robins S. P.. 1992. Age-related changes in the concentration of hydroxypyridinium crosslinks in functionally different skeletal muscles. Matrix. 12:291–296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reiser K., P. Summers J. F. Medrano, R. Rucker, J. Last, and McDonald R.. 1996. Effects of elevated circulating IGF-1 on the extracellular matrix in “high growth” C57BL/6J mice. Am. J. Physiol. 271 (Regulatory Integrative Comp. Physiol. 40):R696–R703. doi:10.1152/ajpregu.1996.271.3.R696 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robins S. P., M. Shimokomaki, and Bailey A. J.. 1973. The chemistry of the collagen cross-links. Age-related changes in the reducible components of intact bovine collagen fibres. Biochem. J. 131:771–780. doi:10.1042/bj1310771 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roy B. C., G. Sedgewick J. L. Aalhus J. A. Basarab, and Bruce H. L.. 2015. Modification of mature non-reducible collagen cross-link concentrations in bovine m. Gluteus medius and semitendinosus with steer age at slaughter, breed cross and growth promotants. Meat Sci. 110:109–117. doi:10.1016/j.meatsci.2015.07.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sell D. R., K. M. Biemel O. Reihl M. O. Lederer C. M. Strauch, and Monnier V. M.. 2005. Glucosepane is a major protein cross-link of the senescent human extracellular matrix. Relationship with diabetes. J. Biol. Chem. 280:12310–12315. doi:10.1074/jbc.M500733200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shorthose W. R., and Harris P. V.. 1990. Effect of animal age on the tenderness of selected beef muscles. J. Food Sci. 55:1–8: 14. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2621.1990.tb06004.x [Google Scholar]

- Shoulders M. D., and Raines R. T.. 2009. Collagen structure and stability. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 78:929–958. doi:10.1146/annurev.biochem.77.032207.120833 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van der Slot A. J., E. A. van Dura E. C. de Wit J. De Groot T. W. Huizinga R. A. Bank, and Zuurmond A. M.. 2005. Elevated formation of pyridinoline cross-links by profibrotic cytokines is associated with enhanced lysyl hydroxylase 2b levels. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1741:95–102. doi:10.1016/j.bbadis.2004.09.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Snedeker J. G., and Gautieri A.. 2014. The role of collagen crosslinks in ageing and diabetes - the good, the bad, and the ugly. Muscles. Ligaments Tendons J. 4:303–308. doi:10.11138/mltj/2014.4.3.303 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reddy G. K. 2004. Cross-linking in collagen by nonenzymatic glycation increases the matrix stiffness in rabbit achilles tendon. Exp. Diabesity Res. 5:143–153. doi:10.1080/15438600490277860 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takaluoma K., M. Hyry J. Lantto R. Sormunen R. A. Bank K. I. Kivirikko J. Myllyharju, and Soininen R.. 2007. Tissue-specific changes in the hydroxylysine content and cross-links of collagens and alterations in fibril morphology in lysyl hydroxylase 1 knock-out mice. J. Biol. Chem. 282:6588–6596. doi:10.1074/jbc.M608830200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winterholler S. J., G. L. Parsons D. K. Walker M. J. Quinn J. S. Drouillard, and Johnson B. J.. 2008. Effect of feedlot management system on response to ractopamine-hcl in yearling steers. J. Anim. Sci. 86:2401–2414. doi:10.2527/jas.2007-0482 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamauchi M., and Sricholpech M.. 2012. Lysine post-translational modifications of collagen. Essays Biochem. 52:113–133. doi:10.1042/bse0520113 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoshida K., H. Jiang M. Kim J. Vink S. Cremers D. Paik R. Wapner M. Mahendroo, and Myers K.. 2014. Quantitative evaluation of collagen crosslinks and corresponding tensile mechanical properties in mouse cervical tissue during normal pregnancy. Plos One. 9:e112391. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0112391 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Young O. A., T. J. Braggins, and Barker G. J.. 1994. Pyridinoline in ovine intramuscular collagen. Meat Sci. 37:297–303. doi:10.1016/0309-1740(94)90088-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]