As the number of older adults with cancer increases, the number of caregivers for these patients is also rising. A 2015 report estimated that 2.4 million Americans provide unpaid care to an adult aged ≥50 with cancer. Cancer caregivers are more likely to report a higher burden of care compared to those caring for non-cancer patients,1 and caregiving can impact caregivers’ emotional and physical health.2,3 However, little is known about how increasing aging-related impairments in this vulnerable population impact caregiver health and quality of life (QOL). The study by Kehoe et al. in this issue sought to evaluate the relationships between geriatric assessment (GA) impairments in older adults with cancer and their caregivers’ QOL, physical health, and emotional health.4

Kehoe et al. conducted a cross-sectional study using baseline data from older adults with advanced cancer and their caregivers from 31 community oncology practice clusters enrolled in the Improving Communication in Older Cancer Patients and Their Caregivers (COACH) study.4 The COACH study is a cluster-randomized trial evaluating if GA-guided recommendations improve communication between patients, caregivers, and oncologists.5 Eligible patients were aged ≥70, had advanced solid tumor or lymphoma, were considering or receiving cancer treatment, and had ≥1 GA domain impairment at enrollment. Caregiver QOL, physical health, and emotional health were assessed with the Short Form Health Survey-12 (SF-12), Patient Health Questionnaire-2 (depression), and Generalized Anxiety Disorder 7-item scale. In total, 414 patients were enrolled with a caregiver. The authors found that a higher number of patient GA domain impairments was associated with worse caregiver QOL (regression coefficient β=−1.14, p<0.001), caregiver physical health (β=−1.24, p<0.001), and caregiver depression (adjusted odds ratio=1.29, p<0.001). Patient functional impairment was associated with lower caregiver QOL, and patient nutritional impairment was associated with caregiver depression.

As the authors note, this study’s cross-sectional design precludes conclusions about causality and the direction of the associations. Nonetheless, the findings are hypothesis-generating and reveal important areas of cancer caregivers’ health that require further evaluation. In addition, the study sample consisted of patients and caregivers enrolled in a clinical trial and thus may not be representative of the general older population with cancer. However, the trial recruited from community oncology sites rather than academic cancer centers, which increases the generalizability of the results.

This study adds to a small number of prior studies that examined associations between patient GA results and caregiver outcomes. Rajasekaran et al.6 evaluated 244 patients aged ≥70 with a new diagnosis of cancer and assessed caregiver burden with the Zarit Burden Interview.7 While multiple GA measures were associated with higher caregiver burden in unadjusted analysis, only Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) performance status of 3–4 and hemoglobin <12 g/dL were associated with higher caregiver burden after adjustment for confounders. In another study, Hsu et al.8 evaluated 100 cancer patients aged ≥65 with caregiver-reported GA measures (except cognition) and caregiver burden as assessed by the Caregiver Strain Index.9 In a multivariable analysis, caregiver employment and patient instrumental activities of daily living (IADL) impairment were associated with higher caregiver burden. Lastly, Germain et al.10 conducted a prospective observational study of 98 patients aged ≥70 and evaluated caregiver burden (Zarit Burden Interview) and QOL (SF-12) at the time of geriatric oncology consultation, 3 months, and 6 months. In a multivariable analysis over 6 months, caregiver age <70, lower caregiver burden, and patient independence in activities of daily living (ADL) were associated with better caregiver QOL on the emotional domain.

Overall, these studies support the finding that worse patient functional status (from global performance status by ECOG to functional status by ADL/IADL) is associated with higher caregiver burden. Kehoe et al.’s study4 identified additional associations with poor caregiver outcomes (e.g., impaired patient nutrition and caregiver depression), likely due to the larger sample size resulting in greater power to detect smaller associations. In addition, Kehoe et al. captured a frailer population with more advanced disease due to the inclusion criteria of advanced cancer and ≥1 GA impairment at enrollment, which were not required in the other studies. Lastly, Kehoe et al. assessed outcomes beyond caregiver burden including QOL, physical health, and emotional health. The main novel finding of this study was that the number of GA domain impairments is associated with all three important caregiver outcomes: overall QOL, physical health, and depression.

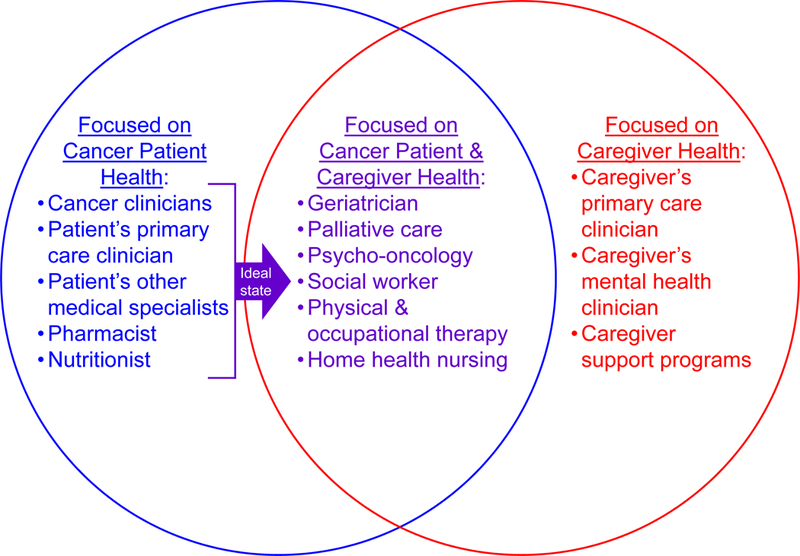

While the study precludes conclusions about the causal direction of the findings (e.g., does patient functional impairment lead to lower caregiver QOL or does lower caregiver QOL contribute to patient functional impairment?), it highlights the complex needs of both older adults with cancer and their caregivers. Just as caring for frail older adults with cancer is challenging for oncologists, geriatricians, and primary care clinicians and requires a multidisciplinary team, caring for these frail older adults at home is equally, if not more, challenging. Providing high quality care for frail older adults with cancer and their caregivers requires a network of multidisciplinary teams with interdisciplinary collaboration and interventions (Figure 1). However, healthcare for cancer patients is commonly fragmented from healthcare for their caregivers. Screening for caregiver burden and needs can help identify areas where caregivers need extra assistance.11 Based on these results, social workers can help secure home health support or transportation assistance. Physical and occupational therapists can help patients improve their mobility and teach caregivers how to safely assist with transfers. A home safety evaluation can provide suggestions for accommodations to reduce caregiver burden. However, these multidisciplinary resources may not be available in smaller community settings, and cancer caregivers may not have established primary care to address their own physical and emotional health. Oncologists, geriatricians, and primary care clinicians for cancer patients should encourage their patients’ caregivers to seek regular healthcare, especially if the cancer patient is frail. Primary care clinicians of cancer caregivers should ask about the impact of caregiving on their health, with attention to mental health. Additionally, some cancer centers offer psycho-oncology support to caregivers independent of whether the patient is receiving psycho-oncology services.

Figure 1. Proposed model of multidisciplinary teams to care for both the older adult with cancer and their caregiver.

Cancer clinicians traditionally focus on the health of cancer patients while interactions with caregivers are often limited to how the caregiver can support the cancer patient’s care. For frail older adults with cancer, these interactions are ideally also opportunities to evaluate caregiver physical and emotional health and provide support to ultimately improve outcomes for both patients and caregivers.

Meta-analyses of intervention studies targeting caregivers or caregiver-patient dyads show overall positive effects on both caregiver and patient outcomes.2,3,12–14 Many studies have evaluated psychosocial interventions (e.g., coping, communication), which help reduce caregiver burden and improve QOL.12,15 Fewer studies have focused on practical skills training (e.g., assisting with ADL/IADLs, medication administration, symptom management).16 Given the impact of patient functional status on caregiver outcomes, skills training-based interventions should be further investigated. Research is also needed to help identify high-risk caregiver-patient dyads and evaluate the optimal intervention type and dose. In addition, although many interventions have been tested in randomized controlled trials, few have moved beyond the research setting into real-world clinical settings. Implementation of evidence-based interventions in the clinical setting should include an evaluation of their potential for cost savings and revenue generation, which are important metrics for stakeholders in the healthcare system.15,17 Overall, caregivers of older adults with cancer face many challenges, and there are multiple barriers to successful interventions (Table 1). Interdisciplinary collaboration as well as institutional level investment and policy change are needed to overcome these challenges.

Table 1.

Challenges and barriers to successful caregiver interventions and potential strategies to overcome challenges

| Challenges and barriers | Potential strategies |

|---|---|

| Clinician Factors | |

| Lack of awareness about caregiver needs | - Oncologists should routinely involve caregivers in visits, with inquiry about whether they have adequate support or resources and place referrals as needed. - Primary care clinicians of caregivers should inquire about their needs, particularly mental health. |

| Lack of screening tools or ability to identify high-risk patient-caregiver dyads | - Research to develop caregiver screening tools. - Consider evaluation of patient geriatric assessment results, such as the number of impairments, as a screening tool for high-risk patient-caregiver dyads. |

| Lack of comfort in addressing caregiver needs, lack of awareness about caregiver interventions | - Improved dissemination and education about evidence-based interventions by cancer centers, clinic caregiver champions, or advocacy groups. |

| Competing demands in high-volume oncology clinics | - Designate a dedicated caregiver champion such that burden does not fall on clinicians alone. - Insurance reimbursement mechanism for caring for caregivers. |

| Inadequate interdisciplinary care | - Multidisciplinary team rounds. - Co-location of oncology with palliative care, psycho-oncology, and other supportive care teams. |

| Patient/caregiver Factors | |

| Physical hardships of taking care of functionally impaired patient | - Referral to physical/occupational therapy if patients require assistance with ADL/IADLs. - Referral to social work for evaluation for home health support. |

| Emotional hardships of patient and caregiver | - Referral to psycho-oncology and palliative care. - Provide information about caregiver support programs, respite care, and other resources. |

| Financial hardships | - Referral to social work or financial counselors. - Develop legislation for paid family or medical leave or other financial compensation for family caregivers. |

| Lack of healthcare literacy, practice skills training (medication administration, monitoring side effects, symptom management, etc) | - Skills training programs initiated by cancer centers to provide knowledge and skills required for addressing common patient needs. - Education by clinician, pharmacist, infusion center staff. - Research on skills training-based interventions. |

| Number of healthcare visits competing for their time | - Utilize telehealth visits if possible. - Social work assistance with transportation alternatives. |

| Institutional/Policy Factors | |

| Inadequate translation of evidence-based interventions to real-world clinical practice | - Implementation research, ideally involving end users of interventions, to develop practical interventions that can be adapted to patient, caregiver, clinic, and institutional needs. |

| Low organizational support for caregiver interventions | - Research should include evaluation of outcomes important for institutional stakeholders, such as decreasing healthcare utilization, cost savings, revenue generation. |

| Lack of funding | - Fee-for-service payment model or insurance reimbursement mechanism for clinicians caring for caregivers. - Institutional support of caregiver programs. |

| Inadequate recognition of the financial toxicity experienced by informal caregivers | - Policy makers should develop legislation for paid family or medical leave or other financial compensation for long-term family caregivers. |

Though U.S. national policy is lacking compared to the need, state legislation and caregiver policy from other countries provide exemplars for a national template. The U.S. Family and Medical Leave Act of 1993 provides unpaid, job-protected leave from work for medical and family reasons for up to 12 weeks.18 For chronic illnesses such as cancer, this short-term relief is often insufficient, and many families struggle financially with unpaid leave. A few states have extended the family leave provisions by providing paid leave (i.e., California, New Jersey, Rhode Island, New York).18 Other countries have developed policies that pay family members for caregiving. Sweden and the United Kingdom have implemented policies that pay family members for whom caregiving becomes a regular job, and Canada’s Compassionate Care Benefit enables caregivers to take partially paid leave to care for a terminally ill family member.2 The U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) has successfully implemented various resources for caregivers, including Caregiver Support Coordinators, Caregiver Support Line, peer support and mentoring, online workshops, and services such as Adult Day Health Care Centers and Respite Care.19 Cancer centers and healthcare systems can learn from these VA examples, and oncology professionals and organizations should consider partnering with caregiving organizations to develop national guidelines and advocate for policy changes.

In summary, Kehoe et al. found that a greater number of GA impairments in an older adult with cancer is associated with worse caregiver outcomes.4 Similar to how geriatric cancer patients benefit from multidisciplinary assessment and management of their needs, caregivers of these patients can also benefit from interdisciplinary interventions. Yet, our current clinical practice and healthcare system are poorly equipped to address their needs. Additional research is needed to identify high-risk caregiver-patient dyads, develop and evaluate interventions, and determine how to practically implement evidence-based interventions in clinical settings. Healthcare institutions, insurance companies, and policy makers should recognize the importance of addressing caregiver needs to improve outcomes for both older cancer patients and caregivers.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Financial disclosure: This work was supported by the National Institute on Aging (T32AG000212, P30AG044281, R03AG056439) and the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences (KL2TR001870).

Sponsor’s role: The authors declare no role for any sponsor in the preparation of this editorial.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest: Dr. Wong has reported a conflict of interest outside of the submitted work (immediate family member is an employee of Genentech with stock ownership). The remaining authors have no conflicts to report.

REFERENCES

- 1.National Alliance for Caregiving, AARP Public Policy Institute. Caregiving in the U.S. 2015; https://www.caregiving.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/05/2015_CaregivingintheUS_Final-Report-June-4_WEB.pdf. Accessed January 21, 2019.

- 2.Northouse L, Williams AL, Given B, McCorkle R. Psychosocial care for family caregivers of patients with cancer. Journal of clinical oncology : official journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology. 2012;30(11):1227–1234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kent EE, Rowland JH, Northouse L, et al. Caring for caregivers and patients: Research and clinical priorities for informal cancer caregiving. Cancer. 2016;122(13):1987–1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kehoe LA, Xu H, Duberstein P, et al. Quality of Life of Caregivers of Older Patients with Advanced Cancer. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mohile SG, Epstein RM, Hurria A, et al. Improving communication with older patients with cancer using geriatric assessment (GA): A University of Rochester NCI Community Oncology Research Program (NCORP) cluster randomized controlled trial (CRCT). Journal of clinical oncology : official journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology. 2018;36(18_suppl):LBA10003–LBA10003. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rajasekaran T, Tan T, Ong WS, et al. Comprehensive Geriatric Assessment (CGA) based risk factors for increased caregiver burden among elderly Asian patients with cancer. Journal of geriatric oncology. 2016;7(3):211–218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zarit SH, Reever KE, Bach-Peterson J. Relatives of the impaired elderly: correlates of feelings of burden. The Gerontologist. 1980;20(6):649–655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hsu T, Loscalzo M, Ramani R, et al. Factors associated with high burden in caregivers of older adults with cancer. Cancer. 2014;120(18):2927–2935. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Robinson BC. Validation of a Caregiver Strain Index. Journal of gerontology. 1983;38(3):344–348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Germain V, Dabakuyo-Yonli TS, Marilier S, et al. Management of elderly patients suffering from cancer: Assessment of perceived burden and of quality of life of primary caregivers. Journal of geriatric oncology. 2017;8(3):220–228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wang T, Molassiotis A, Chung BPM, Tan JY. Unmet care needs of advanced cancer patients and their informal caregivers: a systematic review. BMC palliative care. 2018;17(1):96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Badr H, Krebs P. A systematic review and meta-analysis of psychosocial interventions for couples coping with cancer. Psycho-oncology. 2013;22(8):1688–1704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Candy B, Jones L, Drake R, Leurent B, King M. Interventions for supporting informal caregivers of patients in the terminal phase of a disease. The Cochrane database of systematic reviews 2011(6):Cd007617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hartmann M, Bazner E, Wild B, Eisler I, Herzog W. Effects of interventions involving the family in the treatment of adult patients with chronic physical diseases: a meta-analysis. Psychotherapy and psychosomatics. 2010;79(3):136–148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Trevino KM, Healy C, Martin P, et al. Improving implementation of psychological interventions to older adult patients with cancer: Convening older adults, caregivers, providers, researchers. Journal of geriatric oncology. 2018;9(5):423–429. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mollica MA, Litzelman K, Rowland JH, Kent EE. The role of medical/nursing skills training in caregiver confidence and burden: A CanCORS study. Cancer. 2017;123(22):4481–4487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ratcliff CG, Vinson CA, Milbury K, Badr H. Moving family interventions into the real world: What matters to oncology stakeholders? Journal of psychosocial oncology. 2018:1–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.United States Department of Labor. What’s the Difference? Paid Sick Leave, FMLA, and Paid Family and Medical Leave 2016; https://www.dol.gov/sites/default/files/PaidLeaveFinalRuleComparison.pdf. Accessed January 21, 2019.

- 19.United States Department of Veterans Affairs. VA Caregiver Support. https://www.caregiver.va.gov/. Accessed January 21, 2019.