Abstract

Background:

Emerging evidence shows that cognitively normal older adults with preclinical Alzheimer’s disease (AD) make more errors and are more likely to receive a marginal/fail rating on a standardized road test compared to older adults without preclinical AD, but the extent to which preclinical AD impacts everyday driving behavior is unknown.

Objective:

To examine self-reported and naturalistic longitudinal driving behavior among persons with and without preclinical AD.

Method:

We prospectively followed cognitively normal drivers (aged 65 + years) with (n = 10) and without preclinical AD (n = 10) for 2.5 years. Preclinical AD was assessed using amyloid positron emission tomography (PET) with Pittsburgh Compound B. The Driving Habits Questionnaire assessed self-reported driving outcomes. Naturalistic driving was captured using a commercial GPS data logger plugged into the on-board diagnostics II port of each participant’s vehicle. Data were sampled every 30 seconds and all instances of speeding, hard braking, and sudden acceleration were recorded.

Results:

Preclinical AD participants went to fewer places/unique destinations, traveled fewer days, and took fewer trips than participants without preclinical AD. The preclinical AD group reported a smaller driving space, greater dependence on other drivers, and more difficulty driving due to vision difficulties. Persons with preclinical AD had fewer trips with any aggression and showed a greater decline across the 2.5-year follow-up period in the number of days driving per month and the number of trips between 1–5 miles.

Conclusion:

Changes in driving occur even during the preclinical stage of AD.

Keywords: Alzheimer’s disease, automobile driving, biomarkers, motor vehicles

INTRODUCTION

In the United States (US), 38 million drivers are aged 65 years or older; by 2050, this age group will expand to 84 million and will represent 1 in every 4 drivers [1, 2]. In 2015, 19 older adults were killed, and 712 were injured in a crash on a daily basis; both numbers will increase as the pool of older drivers continues to grow [3].

Alzheimer’s disease (AD) is one of the most prevalent chronic, neurological diseases affecting older adults, and adversely impacts driving [4]. Symptomatic AD affects 11% of older adults (≥65 years), and is associated with more driving difficulties and an increased likelihood of failing a driving test with time [5, 6]. Drivers with symptomatic AD are twice as likely to have a crash compared to healthy older adults [7, 8]. People with symptomatic AD will eventually need to stop driving entirely. An integral part of driving cessation is a period during which older adults actively change their driving behavior, more commonly known as driving reduction [9–11].

However, it is not clear how early driving reduction begins within the pathological process of AD development. In addition to those with symptomatic AD, another 30% of older adults have preclinical AD, the condition in which observable dementia symptoms are not yet present, but the underlying disease process has begun [12]. Preclinical AD can be detected among cognitively normal individuals using positron emission tomography (PET) imaging and cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) biomarkers. Studies have shown that cognitively normal older adults with preclinical AD make more errors and are more likely to receive a marginal/fail rating on a road test compared to older adults without preclinical AD [13, 14]. Furthermore, increases in brain amyloid deposition are associated with a higher frequency of crashes and traffic violations in cognitively normal older adult drivers [15]. Given these changes in driving outcomes, it is therefore possible that driving reduction also occurs early in the AD pathological process.

Due to limitations of road tests and driving simulators in reflecting day-to-day driving behavior [16], naturalistic methodologies using sensors have been increasingly used to passively gather data on daily driving as older adults drive their personal vehicles in their own environment [17–20]. Several naturalistic studies show that drivers with symptomatic AD drive fewer miles, reduce their number of trips, go to fewer unique destinations, and have a reduced driving space (<10 miles from home) compared to cognitively normal peers [16, 21–23]. To date, hypotheses about the impact of preclinical AD on everyday driving behavior have been primarily based on what is known about driving among individuals with symptomatic AD. To our knowledge, our group is the first to examine naturalistic driving behavior in older adults with or without preclinical AD [24].

Previously, we presented data as a small cross-sectional study to examine driving behaviors in cognitively normal individuals with (n = 10) and without preclinical AD (n = 10). In this paper, we report on the extension of the data collection and evaluate changes in both self-reported and objective driving behaviors over a 2.5-year period.

METHODS

Participants

Participants were recruited from longitudinal studies conducted at the Washington University Knight Alzheimer’s Disease Research Center. All participants were cognitively normal (Clinical Dementia Rating [CDR] = 0) [25], ≥65 years old, had a valid driver’s license, drove at least once per week, and had in vivo imaging of brain amyloid using PET with Pittsburgh compound B (PIB) [26].

Participants were divided into those without (n = 10) or with (n = 10) preclinical AD, based on a previously defined mean cortical binding potential (MCBP) using PIB (≥0.18) [27]. The 20 participants recruited for data logger installation were drawn from the larger sample [28, 29]. We first identified all participants who indicated on the Driving Habits Questionnaire (DHQ) that they were always the driver when they went out in their vehicle and determined whether they were PIB positive or negative. PIB positive participants were recruited until 10 agreed to data collection using the data logger, and these 10 participants were then frequency-matched on age with 10 PIB negative participants who also agreed to data logger installation. Of 22 individuals approached, only two participants (9.1%; one who was PIB positive and one who was PIB negative) refused participation in this study. Additional information concerning amyloid PET imaging and matching procedures has been previously published [24]. Lumbar puncture was used to obtain CSF for determination of fluid brain levels of Aβ42, tau, and ptau181. Study protocols were approved by the Washington University Human Research Protection Office, and written informed consent was obtained from all participants.

Driving performance and behavior

A commercial global positioning system (GPS) data logger (G2 Tracking Device™, Azuga Inc, San Jose, CA) was plugged into the vehicle’s onboard diagnostics–II (OBD-II) port and data collected every 30 s. This methodology, termed the Driving Real World In-Vehicle Evaluation System (DRIVES) [30], collected data each time a vehicle was driven. Aggressive actions (hard braking, sudden acceleration, and speeding) were recorded anytime they occurred during a trip, regardless of the 30 s sampling that occurred for other data logger measures. Speeding was determined based on the data logger’s GPS, specifically the latitude and longitude and the posted speed limit in the vehicle’s location. The device compared the vehicle’s speed to the posted speed limit and if the driver was going 6 miles per hour or more above the posted speed limit in that area, an occurrence of speeding was recorded. Data were collected between July 1, 2015 and January 30, 2018 for each participant, although one participant died approximately one year after data collection began. Participants also completed the DHQ [31], a self-report measure of driving behavior over the past year. To maximize the probability that the participant was the driver of the vehicle at all times (as opposed to a spouse, child, friend, etc.), we only recruited individuals who indicated on the DHQ that they were always the driver when they used their vehicle.

Additional clinical testing

Near and far visual acuity and contrast sensitivity were measured using the King-Devick Variable Contrast Sensitivity Chart (https://itunes.apple.com/us/app/variable-contrast-sensitivity-chart-by-king-devick/id527148325?mt=8). Participants also completed the Santa Barbara Sense of Direction Scale [32], the free-recall subtest of the Selective Reminding Test [33], Animal Naming [34], and Trailmaking A and B tests [35].

Statistical analysis

Data were collected and managed securely using a research electronic data capture tool (REDCap) [36]. For data obtained by the DRIVES data logger, a “trip” was defined as data gathered from the period of “ignition on” to “ignition off”. For example, an excursion from home to the grocery store and back to home without any other stops would be considered two trips. For each trip, the date of the trip, the distance of that trip, the time spent traveling, and the route were recorded. Data logger data were aggregated by month so that an individual followed for 2.5 years would have 30 data points across time for each data logger variable. As noted earlier, DHQ data were obtained one time per year. Statistical analyses were conducted in SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc.). Linear mixed models examined whether there was a difference at the y-intercept and over time (i.e., slope) for the preclinical and no preclinical groups for the DRIVES data logger and the DHQ.

RESULTS

At the baseline clinical assessment (Table 1), the 20 participants were well educated (Mean = 16.3 y; SD = 2.3), predominately Caucasian (n = 18), mostly male (n = 13), and ranged in age from 66.4 to 80.8 years (Mean = 73.1 y; SD = 3.9). Seven participants had at least one apolipoprotein ε4 allele and performance on the Mini-Mental State Examination [37] was generally high (Mean = 29.1; SD = 1.1). There were no statistically significant differences between the two groups on any of the aforementioned demographic variables (p > 0.05). MCBP values ranged from –0.004 to 0.07 for the PIB negative group and from 0.18 to 1.06 for the PIB positive group. As expected, participants in the preclinical AD group also had more abnormal mean values of MCBP, and CSF Aβ42, tau, and ptau181 (Table 1). However, participants with preclinical AD at baseline recalled significantly fewer words on the free recall subtest of the Selective Reminding Test [33] (p = 0.03), and reported a marginally worse (p = 0.052) sense of direction as assessed by the Santa Barbara Sense of Direction Scale (Table 1). Participants with preclinical AD had lower near visual acuity values compared to those without preclinical AD, although the difference did not reach statistical significance (p = 0.083).

Table 1.

Demographics and baseline testing

| PIB Negative |

PIB Positive |

p | Total |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N/Mean | %/SD | N/Mean | %/SD | N/Mean | %/SD | ||

| Age, y | 71.9 | 3.1 | 74.5 | 4.3 | 0.139 | 73.2 | 3.9 |

| Women, N | 5 | 50.0% | 2 | 20.0% | 0.160 | 7 | 35.0% |

| APOE ɛ4, N | 3 | 30.0% | 4 | 40.0% | 0.639 | 7 | 35.0% |

| Education, y | 16.6 | 1.7 | 16.0 | 2.8 | 0.565 | 16.3 | 2.3 |

| MCBP for PIB | 0.03 | 0.03 | 0.46 | 0.26 | <0.001 | 0.25 | 0.28 |

| CSF Aβ42, pg/mL | 840.4 | 221.8 | 524.5 | 206.6 | 0.004 | 682.5 | 264.2 |

| tau, pg/mL | 227.9 | 64.3 | 523.5 | 285.1 | 0.001 | 375.7 | 251.9 |

| ptau181, pg/mL | 45.2 | 8.5 | 85.7 | 36.4 | 0.007 | 65.5 | 33.1 |

| Selective Reminding Test - Free Recall | 34.6 | 5.1 | 28.1 | 7.2 | 0.031 | 31.4 | 6.9 |

| Animal Naming | 23.0 | 5.8 | 19.6 | 4.6 | 0.166 | 21.3 | 5.4 |

| Trailmaking A, s | 27.7 | 7.4 | 32.7 | 10.7 | 0.240 | 30.2 | 9.3 |

| Trailmaking B, s | 79.4 | 39.8 | 92.1 | 41.1 | 0.516 | 85.8 | 39.8 |

| Santa Barbara Sense of Direction | 5.8 | 1.0 | 4.7 | 1.2 | 0.052 | 5.2 | 1.2 |

| Near acuity | 68.0 | 1.8 | 65.5 | 3.9 | 0.083 | 66.8 | 3.2 |

| Far acuity | 48.6 | 7.3 | 48.4 | 43.6 | 0.950 | 48.5 | 6.8 |

| Contrast sensitivity | 21.8 | 8.5 | 21.0 | 8.4 | 0.834 | 21.4 | 8.2 |

PIB, Pittsburgh Compound B; SD, standard deviation; MCBP, mean cortical binding potential; s, seconds.

All participants were followed for exactly 2.5 years, except for one participant who died approximately one year after data collection began. Because our major interest was change in DHQ and data logger variables across time, and our main analyses were conducted using linear mixed models, there was no “baseline” visit for these variables. Instead, y-intercepts generated by the mixed models, and differences between them, were taken to indicate whether there were statistical differences between the groups on the driving outcomes at the beginning of data collection. The y-intercept estimates yielded by the mixed modes indicated that differences existed at the beginning of data collection on multiple driving variables between participants with and without preclinical AD (Table 2). Based on data from both self-report and the DRIVES data logger at the beginning of the follow-up period, participants with preclinical AD traveled more miles, but went to fewer places/unique destinations, drove on fewer days, and took fewer trips than participants without preclinical AD. The DRIVES data also demonstrated that persons with preclinical AD drove more miles per trip and spent more time driving per trip. The preclinical AD group reported a smaller driving space and more difficulty driving due to vision. Despite all participants indicating on the DHQ that they were always the driver when they used their vehicle, individuals with preclinical AD reported greater dependence on other drivers. The data logger indicated that persons with preclinical AD had fewer trips with any aggression (Table 2).

Table 2.

Y-intercept values yielded by the mixed models for driving outcomes

| PIB Negative |

PIB Positive |

p | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | SE | Mean | SE | ||

| Self-report on the DHQ (per average week) | |||||

| # miles | 174.43 | 55.60 | 186.71 | 55.47 | 0.002 |

| # trips total | 10.03 | 1.17 | 9.22 | 1.65 | <0.001 |

| # places visited | 5.19 | 0.71 | 4.73 | 0.71 | <0.001 |

| Driving space | 5.38 | 0.28 | 4.95 | 0.28 | <0.001 |

| Dependence on other drivers | 1.00 | 0.12 | 1.18 | 0.12 | <0.001 |

| Average days/week usually drive? | 6.35 | 0.59 | 5.73 | 0.58 | <0.001 |

| Difficulty driving due to vision | 95.96 | 3.82 | 98.69 | 3.82 | <0.001 |

| DRIVES data logger (per month) | |||||

| # miles | 847.69 | 250.09 | 891.57 | 250.38 | <0.001 |

| # trips total | 122.04 | 14.92 | 106.79 | 14.95 | <0.001 |

| # trips <1 mile | 26.88 | 5.89 | 21.43 | 5.90 | <0.001 |

| # trips 1–5 miles | 46.83 | 7.26 | 44.97 | 7.27 | <0.001 |

| # trips 5–10 miles | 25.20 | 2.99 | 14.97 | 3.00 | <0.001 |

| # trips 10–20 miles | 13.44 | 3.57 | 15.88 | 3.57 | <0.001 |

| # trips 20 + miles | 9.56 | 5.19 | 10.14 | 5.19 | 0.032 |

| # hours driven | 29.81 | 5.79 | 27.04 | 5.80 | <0.001 |

| # days driven | 24.33 | 1.33 | 24.03 | 1.33 | <0.001 |

| Mean miles/trip | 6.37 | 1.49 | 8.35 | 1.49 | <0.001 |

| Mean hours/trip | 0.23 | 0.03 | 0.26 | 0.00 | <0.001 |

| Mean trips/day | 4.91 | 0.42 | 4.34 | 0.32 | <0.001 |

| Mean trips at night | 0.06 | 0.01 | 0.05 | 0.01 | <0.001 |

| # unique destinations | 44.42 | 5.47 | 39.40 | 5.48 | <0.001 |

| Mean trips with speeding | 3.83 | 1.98 | 4.19 | 1.98 | 0.036 |

| Mean trips with sudden acceleration | 17.20 | 6.26 | 10.09 | 6.27 | 0.020 |

| Mean trips with hard braking | 13.11 | 2.28 | 10.91 | 2.29 | <0.001 |

| Mean trips some aggression | 27.44 | 6.38 | 20.75 | 6.38 | <0.000 |

AD, Alzheimer’s disease; DHQ, Driving Habits Questionnaire; DRIVES, Driving Real-World In-Vehicle Evaluation System.

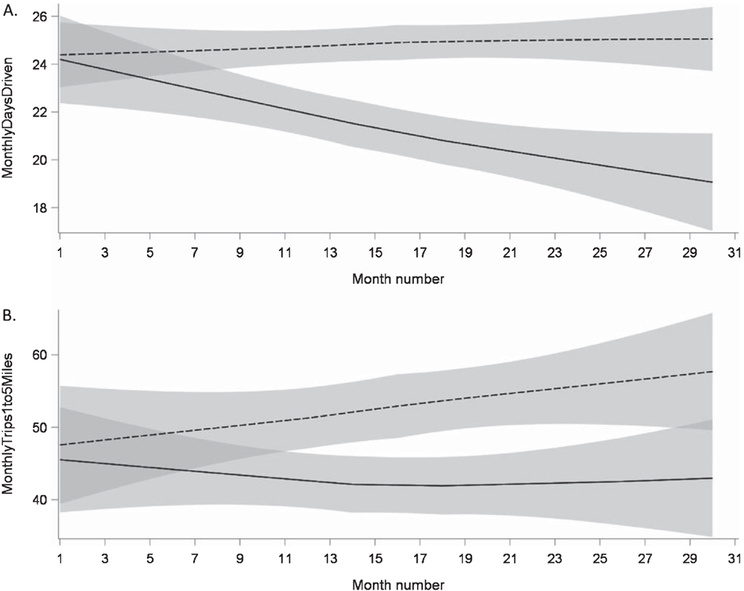

Generally, the linear mixed models showed little difference between the two groups in longitudinal change in driving behaviors over time (Table 3). However, data logger results showed that participants with preclinical AD showed a greater decline over the follow-up period in the number of days driven per month compared to those without preclinical AD (Fig. 1B) and the groups differed in the rate of change of the number of trips between one and five miles (Fig. 1C) This is particularly notable since the majority of trips made by participants across the 2.5–year observation period were below five miles, comprising approximately 70% of all trips (Table 2).

Table 3.

Slope (change/year) values yielded by the mixed models for driving outcomes

| No preclinical AD |

Preclinical AD |

Prob. | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | SE | Mean | SE | |||

| Self-report on the DHQ (per average week) | ||||||

| # miles | 19.31 | 28.95 | 13.61 | 28.93 | 0.890 | |

| # trips total | 0.94 | 0.85 | 0.79 | 0.79 | 0.898 | |

| # places visited | −0.16 | 0.25 | 0.20 | 0.25 | 0.326 | |

| Driving space | −0.17 | 0.15 | −0.31 | 0.15 | 0.555 | |

| Dependence on other drivers | 0.08 | 0.14 | 0.11 | 0.13 | 0.913 | |

| Average days/week usually drive? | −0.07 | 0.21 | 0.06 | 0.21 | 0.661 | |

| Difficulty driving due to vision | −0.38 | 3.55 | −1.69 | 3.55 | 0.794 | |

| Data logger (per month) | ||||||

| # miles | −0.28 | 7.22 | −9.08 | 7.45 | 0.367 | |

| # trips total | 0.25 | 0.43 | −0.70 | 0.45 | 0.147 | |

| # trips < 1 mile | −0.05 | 0.13 | −0.15 | 0.13 | 0.307 | |

| # trips 1–5 miles | 0.36 | 0.19 | −0.22 | 0.19 | 0.040 | |

| # trips 5–10 miles | −0.01 | 0.08 | −0.14 | 0.09 | 0.280 | |

| # trips 10–20 miles | 0.03 | 0.07 | −0.16 | −0.16 | 0.102 | |

| # trips 20 + miles | −0.07 | 0.14 | −0.09 | 0.14 | 0.950 | |

| # hours driven | −0.003 | 0.16 | −0.22 | 0.17 | 0.349 | |

| # days driven | 0.02 | 0.05 | −0.17 | 0.06 | 0.026 | |

| Mean miles/trip | −0.01 | 0.04 | −0.04 | 0.04 | 0.594 | |

| Mean hours/trip | −0.0002 | 0.001 | −0.001 | 0.001 | 0.572 | |

| Mean trips/day | 0.005 | 0.01 | 0.001 | 0.01 | 0.869 | |

| Mean trips at night | −0.0002 | 0.0004 | 0.005 | 0.0005 | 0.259 | |

| Driving area, m2 | 8.10E + 07 | 2.63E + 08 | −4.99E + 08 | 2.72E + 08 | 0.136 | |

| Driving perimeter, m2 | 2,993.02 | 4,592.28 | −4,947.07 | 4,852.93 | 0.252 | |

| # unique destinations | 0.11 | 0.17 | −0.26 | 0.18 | 0.183 | |

| Mean trips with speeding | 0.00 | 0.03 | 0.06 | 0.03 | 0.516 | |

| Mean trips with sudden acceleration | −0.41 | 0.14 | −0.18 | 0.14 | 0.262 | |

| Mean trips with hard braking | −0.16 | 0.06 | −0.11 | 0.06 | 0.543 | |

| Mean trips some aggression | −0.39 | 0.14 | −0.15 | 0.15 | 0.259 | |

AD, Alzheimer disease; DHQ, Driving Habits Questionnaire; DRIVES, Driving Real-World In-Vehicle Evaluation System.

Fig. 1.

Longitudinal change in selected DRIVES data logger outcomes for the preclinical (solid line) and control (dashed line) groups, showing A. differences in both intercept (p > 0.001) and slope (p = 0.026) for days driven per month; and B. differences in both intercept (p < 0.001) and slope (p = 0.040) for monthly trips between 1 and 5 miles.

Given the differences between the preclinical and no preclinical groups at the baseline office testing session, we also examined correlations between the free recall and reported sense of direction scores with the driving outcomes. DHQ outcomes at baseline were used in these analyses. For DRIVES data logger outcomes, the mean for each outcome was calculated across all study months and these calculated means were used as dependent variables. Greater self-reported sense of direction was correlated with driving more days per week on the DHQ (r = 0.46, p = 0.040); and as recorded by the data logger, driving more days per month (r = 0.46, p = 0.041) and taking a greater number of trips between 5 and 10 miles (r = 0.49, p = 0.030).

DISCUSSION

Comparison of the estimates yielded by linear mixed models demonstrated that at the beginning of the follow-up period (i.e., y-intercepts) older adults with preclinical AD were statistically different from those without preclinical AD on both self-reported driving habits and DRIVES daily driving behavior recordings. Furthermore, over time, older adults with preclinical AD experienced greater rates of change (slopes) in selected driving behaviors compared to those without preclinical AD.

These results confirm and extend our cross-sectional findings [24]. Despite a limited sample size, we found that older drivers with preclinical AD have decreased driving space and driving exposure (miles, trips, places visited, days/week) based on both self-report and objective measurement of driving behavior compared to those without preclinical AD. Drivers with preclinical AD also had a lower number of trips with aggressive behavior (especially, hard braking and sudden acceleration). Most notably, older adults with preclinical AD experience a greater rate of decline over two and one-half years in certain driving behaviors compared to those without preclinical AD, specifically in the number of days driven in a month and number of trips made between one to five miles.

Previous studies examining naturalistic driving behavior among persons with normal cognition and those with cognitive impairment have typically used in-car cameras [16–18, 38, 39], although use of OBD II-connected data loggers, as in this study, is increasing [19, 20]. The differences found in this study are consistent with previous studies comparing persons with symptomatic AD and controls [16], but provide further insight demonstrating that differences in naturalistic driving behavior are evident even during the long preclinical stage of AD. Participants with preclinical AD may be already self-limiting their daily driving behavior as evidenced by a lower number of overall trips and number of unique places from the DRIVES data logger and DHQ data. It has been suggested that changes in executive function would lead to later recognition of dangerous situations, and this might lead to more last-minute braking.

However, as in symptomatic AD, we found a lower rate of aggressive behaviors in participants with preclinical AD. This may suggest an active process of internal behavior monitoring [16, 39]. However, although participants with preclinical AD made fewer trips, they traveled more miles per trip than those without preclinical AD. The overall lower scores on the Santa Barbara Sense of Direction Scale [32], a self-report measure of environmental spatial ability, suggests that persons with preclinical AD may have more difficulty navigating their environment.

Emerging research is beginning to establish that changes in sensory (e.g., vision, hearing, olfaction) and motor function occur in the preclinical stage of AD, and may precede any measurable cognitive decline [40]. An increase in vision problems like cataracts and macular degeneration has been associated with preclinical AD [40]. Additionally, decline in strength, range of motion, and reaction time have been shown in individuals with preclinical AD [41, 42]. The visual system is the primary sensory skill used in driving and directly influences the motor system; deficits in one or both of these crucial systems will impact driving behavior. Thus, there may be an effect of vision problems linked to preclinical AD impacting driving space and exposure in our sample. Screenings of the visual system (e.g., visual acuity, contrast sensitivity) and motor system (grip strength, range of motion) are common in medical settings and Departments of Motor Vehicles for licensure renewal. Since function of the sensory and motor systems are also age-dependent, understanding their individual and combined functions (e.g., reaction time) on driving in the context of preclinical AD may help to better understand driving decline and eventual driving retirement. The findings that greater self-reported sense of direction is associated with both driving on more days, as well as not having preclinical AD, suggest that larger samples should explore the comparative predictive ability of AD biomarkers and self-reported sense of direction on driving outcomes.

There are several limitations to this study. The sample size was small, and despite having results that were statistically significant, not all may be clinically meaningful. PET-PIB imaging is not readily available to the public nor is it reimbursable by health insurance. Since an objective method to detect the driver of the vehicle was unavailable, self-report of being the only driver of a vehicle may not always be accurate, and another driver (e.g., spouse, family, friend) may have made a small percentage of trips. Given the length of the longitudinal follow-up period, this is not expected to affect the study results. Finally, this study occurred in the greater St. Louis metropolitan area, therefore our findings may not be generalizable to regions with different geography or traffic density.

In conclusion, this study suggests that changes in driving behavior appear in preclinical AD and progress through conversion to dementia. Driving reduction during the preclinical stage may reflect awareness by the individuals of subtle intra-individual differences in driving skills and associated efforts to reduce driving risk. With progression of the AD pathological process, as executive function declines, drivers may take longer to anticipate dangerous situations and show increases in outcomes such as hard braking and crashes. Future longitudinal studies with larger samples and additional participant populations are needed to test these hypotheses.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors thank the participants, investigators, and staff of the Knight Alzheimer Disease Research Center Clinical Core for participant assessments, Genetics Core for APOE ε genotyping, and the Imaging Core for amyloid imaging. Imaging facilities were supported by the Washington University Institute of Clinical and Translational Sciences grant UL1TR000448 from the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences (NCATS) of the National Institutes of Health (NIH). Imaging analyses used the services of the Neuroimaging Informatics and Analysis Center, supported by NIH grant 5P30NS048056. Funding for this study was provided by the National Institute on Aging [R01AG056466, R01AG043434 P50AG005681, P01AG003991, and P01AG026276]; Fred Simmons and Olga Mohan, the Farrell Family Research Fund, the Paula and Rodger O. Riney Fund, the Daniel J Brennan MD Fund, and the Charles and Joanne Knight Alzheimer’s Research Initiative of the Washington University Knight Alzheimer Disease Research Center. The sponsors had no role in the design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; and preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript.

Footnotes

Authors’ disclosures available online (https://www.j-alz.com/manuscript-disclosures/18-1242r2).

REFERENCES

- [1].Mizenko AJ, Tefft BC, Arnold LS, Grabowski J (2014) Older American Drivers and Traffic Safety Culture: A LongROAD Study Transportation Research Board. [Google Scholar]

- [2].National Center for Statistics and Analysis (2015) Older Population: Traffic Safety Facts 2012 Data US Department of Transportation. [Google Scholar]

- [3].Centers for Disease Control Prevention, Web-based Injury Statistics Query and Reporting System (WISQARS), https://www.cdc.gov/motorvehiclesafety/older_adult_drivers/index.html,

- [4].Alzheimer’s Association, 2017. Alzheimer’s disease facts and figures, Elsevier, http://www.alz.org/documents_custom/2017-facts-and-figures.pdf, [Google Scholar]

- [5].Duchek JM, Carr DB, Hunt L, Roe CM, Xiong C, Shah K, Morris JC (2003) Longitudinal driving performance in early stage dementia of the Alzheimer type. J Am Geriatr Soc 51, 1342–1347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Ott BR, Heindel W, Papandonatos GD, Festa EK, Davis JD, Daiello LA, Morris JC (2008) A longitudinal study of drivers with Alzheimer’s disease. Neurology 70, 1171–1178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Carr DB, O’Neill D (2015) Mobility and safety issues in drivers with dementia. Int Psychogeriatr 27, 1613–1622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Ott BR, Daiello LA (2010) How does dementia affect driving in older patients? Aging Health 6, 77–85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Molnar LJ, Eby DW, Charlton JL, Langford J, Koppel S, Marshall S, Man-Son-Hing M (2013) Driving avoidance by older adults: Is it always self-regulation? Accid Anal Prev 57, 96–104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Molnar LJ, Eby DW, Langford J, Charlton JL, Louis RMS, Roberts JS (2013) Tactical, strategic, and life-goal self-regulation of driving by older adults: Development and testing of a questionnaire. J Safety Res 46, 107–117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Anstey KJ, Windsor TD, Luszcz MA, Andrews GR (2006) Predicting driving cessation over 5 years in older adults: Psychological well-being and cognitive competence are stronger predictors than physical health. J Am Geriatr Soc 54, 121–126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Jansen WJ, Ossenkoppele R, Knol DL, Tijms BM, Scheltens P, Verhey FRJ, Visser PJ, Aalten P, Aarsland D, Alcolea D, Alexander M, Almdahl IS, Arnold SE, Baldeiras I, Barthel H, Van Berckel BNM, Bibeau K, Blennow K, Brooks DJ, Van Buchem MA, Camus V, Cavedo E, Chen K, Chetelat G, Cohen AD, Drzezga A, Engelborghs S, Fagan AM, Fladby T, Fleisher AS, Van Der Flier WM, Ford L, Forster S, Fortea J, Foskett N, Frederiksen KS, Freund-Levi Y, Frisoni GB, Froelich L, Gabryelewicz T, Gill KD, Gkatzima O, Gomez-Tortosa E, Gordon MF, Grimmer T, Hampel H, Hausner L, Hellwig S, Herukka SK, Hildebrandt H, Ishihara L, Ivanoiu A, Jagust WJ, Johannsen P, Kandimalla R, Kapaki E, Klimkowicz-Mrowiec A, Klunk WE, Kohler S, Koglin N, Kornhuber J, Kramberger MG, Van Laere K, Landau SM, Lee DY, De Leon M, Lisetti V, Lleo A, Madsen K, Maier W, Marcusson J, Mattsson N, De Mendonca A, Meulenbroek O, Meyer PT, Mintun MA, Mok V, Molinuevo JL, Mollergard HM, Morris JC, Mroczko B, Van Der Mussele S, Na DL, Newberg A, Nordberg A, Nordlund A, Novak GP, Paraskevas GP, Parnetti L, Perera G, Peters O, Popp J, Prabhakar S, Rabinovici GD, Ramakers IHGB, Rami L, De Oliveira CR, Rinne JO, Rodrigue KM, Rodriguez-Rodriguez E, Roe CM, Rot U, Rowe CC, Ruther E, Sabri O, Sanchez-Juan P, Santana I, Sarazin M, Schroder J, Schutte C, Seo SW, Soetewey F, Soininen H, Spiru L, Struyfs H, Teunissen CE, Tsolaki M, Vandenberghe R, Verbeek MM, Villemagne VL, Vos SJB, Van Waalwijk Van Doorn LJC, Waldemar G, Wallin A, Wallin AK, Wiltfang J, Wolk DA, Zboch M, Zetterberg H(2015) Prevalence of cerebral amyloid pathology in persons without dementia: A meta-analysis. JAMA 313, 1924–1938. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Roe CM, Babulal GM, Head DM, Stout SH, Vernon EK, Ghoshal N, Garland B, Barco PP, Williams MM, Johnson A, Fierberg R, Fague MS, Xiong C, Mormino E, Grant EA, Holtzman DM, Benzinger TLS, Fagan AM, Ott BR, Carr DB, Morris JC (2017) Preclinical Alzheimer’s disease and longitudinal driving decline. Alzheimers Dement (N Y) 3, 74–82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Roe CM, Barco PP, Head DM, Ghoshal N, Selsor N, Babulal GM, Fierberg R, Vernon EK, Shulman N, Johnson A, Fague S, Xiong C, Grant EA, Campbell A, Ott BR, Holtzman DM, Benzinger TLS, Fagan AM, Carr DB, Morris JC (2017) Amyloid imaging, cerebrospinal fluid biomarkers predict driving performance among cognitively normal individuals. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord 31, 69–72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Ott BR, Jones RN, Noto RB, Yoo DC, Snyder PJ, Bernier JN, Carr DB, Roe CM (2017) Brain amyloid in preclinical Alzheimer’s disease is associated with increased driving risk. Alzheimers Dement (Amst) 6, 136–142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Eby DW, Silverstein NM, Molnar LJ, LeBlanc D, Adler G (2012) Driving behaviors in early stage dementia: A study using in-vehicle technology. Accid Anal Prev 49, 330–337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Dingus TA, Hankey JM, Antin JF, Lee SE, Eichelberger L, Stulce KE, McGraw D, Perez M, Stowe L (2015) Naturalistic Driving Study: Technical Coordination and Quality Control

- [18].Marshall SC, Man-Son-Hing M, Bedard M, Charlton J, Gagnon S, Gelinas I, Koppel S, Korner-Bitensky N, Langford J, Mazer B (2013) Protocol for Candrive II/Ozcandrive, a multicentre prospective older driver cohort study. Accid Anal Prev 61, 245–252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Seelye A, Mattek N, Sharma N, Witter P, Brenner A, Wild K, Dodge H, Kaye J (2017) Passive assessment of routine driving with unobtrusive sensors: A new approach for identifying and monitoring functional level in normal aging and mild cognitive impairment. J Alzheimers Dis 59, 1427–1437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Li G, Eby DW, Santos R, Mielenz TJ, Molnar LJ, Strogatz D, Betz ME, DiGuiseppi C, Ryan LH, Jones V, Pitts SI, Hill LL, DiMaggio CJ, LeBlanc D, Andrews HF, Bogard S, Chihuri S, Engler AM, Feng M, Gessner R, Grabowski JG, Guralnik J, Hewitt B, Johnson A, Kostyniuk LP, Lang BH, Leu C, Merlel D, Nyquist LV, Parnham T, Scott K, Renée M, Ventura M, Yung R, Zanier N, Zakrajsek J (2017) Longitudinal Research on Aging Drivers (LongROAD): Study design and methods. Inj Epidemiol 4, 22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Davis JD, Papandonatos GD, Miller LA, Hewitt SD, Festa EK, Heindel WC, Ott BR (2012) Road test and naturalistic driving performance in healthy and cognitively impaired older adults: Does environment matter? J Am Geriatr Soc 60, 2056–2062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Kostyniuk LP, Molnar LJ (2008) Self-regulatory driving practices among older adults: Health, age and sex effects. Accid Anal Prev 40, 1576–1580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Molnar LJ, Eby DW (2008) The relationship between selfregulation and driving-related abilities in older drivers: An exploratory study. Traffic Inj Prev 9, 314–319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Babulal GM, Stout SH, Benzinger TL, Ott BR, Carr DB, Webb M, Traub CM, Addison A, Morris JC, Warren DK, Roe CM (2019) A naturalistic study of driving behavior in older adults and preclinical Alzheimer disease. J Appl Gerontol 38, 277–289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Morris JC (1993) The Clinical Dementia Rating (CDR): Current version and scoring rules. Neurology 43, 2412–2414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Klunk WE, Engler H, Nordberg A, Wang Y, Blomqvist G, Holt DP, Bergström M, Savitcheva I, Huang GF, Estrada S, Ausén B, Debnath ML, Barletta J, Price JC, Sandell J, Lopresti BJ, Wall A, Koivisto P, Antoni G, Mathis CA, Långström B (2004) Imaging brain amyloid in Alzheimer’s disease with Pittsburgh Compound-B. Ann Neurol 55, 306–319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Morris JC, Roe CM, Xiong C, Fagan AM, Goate AM, Holtzman DM, Mintun MA (2010) APOE predicts amyloid-beta but not tau Alzheimer pathology in cognitively normal aging. Ann Neurol 67, 122–131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Roe CM, Barco PP, Head DM, Ghoshal N, Selsor N, Babulal GM, Fierberg R, Vernon EK, Shulman N, Johnson A, Fague S, Xiong C, Grant EA, Campbell A, Ott BR, Holtzman DM, Benzinger TL, Fagan AM, Carr DB, Morris JC (2017) Amyloid imaging, cerebrospinal fluid biomarkers predict driving performance among cognitively normal individuals. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord 31, 69–72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Roe CM, Babulal GM, Head DM, Stout SH, Vernon EK, Ghoshal N, Garland B, Barco PP, Williams MM, Johnson A, Fierberg R, Fague MS, Xiong C, Mormino E, Grant EA, Holtzman DM, Benzinger TLS, Fagan AM, Ott BR, Carr DB, Morris JC (2017) Preclinical Alzheimer’s disease and longitudinal driving decline. Alzheimers Dement (N Y) 3, 74–82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Babulal GM, Traub CM, Webb M, Stout SH, Addison A, Carr DB, Ott BR, Morris JC, Roe CM (2016) Creating a driving profile for older adults using GPS devices and naturalistic driving methodology. F1000Res 5, 2376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Owsley C, Stalvey B, Wells J, Sloane ME (1999) Older drivers and cataract: Driving habits and crash risk. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 54, M203–M211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Hegarty M, Richardson AE, Montello DR, Lovelace K, Subbiah I (2002) Development of a self-report measure of environmental spatial ability. Intelligence 30, 425–447. [Google Scholar]

- [33].Grober E, Buschke H, Crystal H, Bang S, Dresner R (1988) Screening for dementia by memory testing. Neurology 38, 900–903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Goodglass H, Kaplan E (1983) The assessment of aphasia and related disorders, Lea & Febiger, Philadelphia. [Google Scholar]

- [35].Armitage SG (1946) An analysis of certain psychological tests used in the evaluation of brain injury. Psychol Monogr 60, 1–48. [Google Scholar]

- [36].Harris PA, Taylor R, Thielke R, Payne J, Gonzalez N, Conde JG (2009) Research electronic data capture (REDCap)-A metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. J Biomed Inform 42, 377–381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Folstein MF, Folstein SE, McHugh PR (1975) Mini-mental State: A practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinicians. J Psychiatr Res 12, 189–198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Paire-Ficout L, Lafont S, Conte F, Coquillat A, Fabrigoule C, Ankri J, Blanc F, Gabel C, Novella JL, Morrone I, Mahmoudi R (2018) Naturalistic driving study investigating self-regulation behavior in early Alzheimer’s disease: A pilot study. J Alzheimers Dis 63, 1499–1508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Festa EK, Ott BR, Manning KJ, Davis JD, Heindel WC (2013) Effect of cognitive status on self-regulatory driving behavior in older adults an assessment of naturalistic driving using in-car video recordings. J Geriatr Psychiatry Neurol 26, 10–18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Albers MW, Gilmore GC, Kaye J, Murphy C, Wingfield A, Bennett DA, Boxer AL, Buchman AS, Cruickshanks KJ, Devanand DP (2015) At the interface of sensory and motor dysfunctions and Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimers Dement 11, 70–98. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Patten RV, Fagan AM, Kaufman DAS (2018) Differential cued-stroop performance in cognitively asymptomatic older adults with biomarker-identified risk for Alzheimer’s disease: A pilot study. Curr Alzheimer Res 15, 820–827. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].Gorus E, De Raedt R, Lambert M, Lemper J-C, Mets T (2008) Reaction times and performance variability in normal aging, mild cognitive impairment, and Alzheimer’s disease. J Geriatr Psychiatry Neurol 21, 204–218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]