Abstract

Purpose:

Although the microvascular system is a significant target for radiation-induced effects, the lymphatic response to radiation has not been extensively investigated. This is one of the first investigations characterizing the lymphatic endothelial response to ionizing radiation.

Materials and Methods:

Rat mesenteric lymphatic endothelial cells (RMLECs) were exposed to X-ray doses of 0, 0.5, 1, 1.5, and 2 Gy. RMLEC cellular response was assessed 24 and 72-h post-irradiation via measures of cellular morphometry and junctional adhesion markers. RMLEC functional response was characterized via permeability experiments.

Results:

Cell morphometry showed radiation sensitivity at all doses. Notably there was a loss of cell-to-cell adhesion with irradiated cells increasing in size and cellular roundness. This was coupled with decreased β-catenin and VE-cadherin intensity and altered F-actin anisotropy, leading to a loss of intercellular contact. RMLEC monolayers demonstrated increased permeability at all doses 24h post-irradiation and at 2-Gy 72h post-irradiation.

Conclusions:

In summary, lymphatics show radiation sensitivity in the context of these cell culture experiments. Our results may have functional implications of lymphatics in tissue, with endothelial barrier dysfunction due to loss of cell-cell adhesion leading to leaky vessels and lymphedema. These preliminary experiments will build the framework for future investigations towards lymphatic radiation exposure response.

Keywords: lymphatic endothelium, permeability, barrier function, ionizing radiation, radiation biology, lymphedema

Introduction:

The lymphatic vascular system is part of the circulatory system comprising a network of vessels complementary to the blood vascular system. The lymphatics act as the main transport path of the fluid and elements (proteins, antigens, cytokines, and cells) that constitute lymph from the parenchymal tissues to the nodes via the afferent lymphatic and from the nodes back to the venous blood via the efferent lymphatics. Lymph transport in humans amounts to ~ 4–5 liters of interstitial fluid daily, with effective lymphatic function requiring the formation of lymph from the interstitium at the lymphatic capillaries. Lymphatics capillaries are thin walled, endothelial-lined, highly compliant vessels that begin the lymphatic network (Zawieja 2009). The lymphatic endothelium have the critical function of modulating lymphatic contractility and lymph transport of lymphatics vessels (Zawieja 2009; Scallan and Huxley 2010).

In supporting lymph transport, lymphatic endothelial cells (LECs) maintain lymphatic permeability, or the capacity of allowing flux of lymph contents in and out of lymphatic vessels (Zawieja 2009; Scallan and Huxley 2010; Cromer et al. 2014). Lymphatic permeability is large compared to blood vessels, due to larger intercellular gaps between LECs. Consequently, an impairment of LEC barrier function (i.e. via enlargement of the intercellular gaps between LECs) results in impaired lymph transport, edema development, and lymphatic dysfunction (Scallan and Huxley 2010, Sabine et al. 2012, Cromer et al. 2014). Indeed, regulating lymphatic permeability is important to the control of lymphatic function, with the lymphatic endothelium considered the principle regulator of lymphatic permeability (Scallan and Huxley 2010).

The exact molecular mechanisms involved in LEC permeability, i.e. barrier function, is not as well understood as in blood vasculature. Recent evidence suggests the mechanisms involved in the lymphatics are analogous to mechanisms regulating the post-capillary venous endothelium (Dorland and Huveneers 2017, Shen et al. 2010). Blood and lymphatic vascular permeability is tied to control of respective endothelial cell size, shape, cytoskeletal arrangement, contractile elements, intercellular adhesion molecules, and integrins, as well as the downstream molecular pathways which regulate these elements. A precise equilibrium exists between blood and lymphatic microvascular endothelial cell-cell adhesion and corresponding intracellular actin-myosin-based centripetal tension, which controls the semi-permeability of blood and lymphatic microvascular barriers (Dorland and Huveneers 2017, Shen et al. 2010). Disequilibrium in these cell-cell adhesion mechanisms, controlled by intracellular cytoskeletal units, leads to impairment in maintaining blood and lymphatic permeability function (Dorland and Huveneers 2017). Indeed, losses in cell-cell adhesion and cell morphometry due to irradiation are associated with increases in blood microvascular permeability, documented previously in human dermal blood microvasculature and umbilical vein endothelial cells (Gabrys et al. 2007). Furthermore, these losses in blood vascular cell-cell adhesion were mechanistically tied to VE-cadherin redistribution, a classical adherens junctional (Gabrys et al. 2007).

Protein complexes between endothelial cells, for both blood and lymphatic endothelium, include adherens junctions that link to the intracellular cytoskeleton via actin. Adherens junctions consist of the transmembrane protein VE-cadherin, and intracellular protein components such as β-catenin (Di Lorenzo et al. 2013, Iyer et al. 2004, Lampugnani et al. 1995). VE-cadherin initiate intercellular contacts through trans-pairing between cadherins on opposing cells. β-catenin binds to the cytoplasmic domain of VE-cadherin, with actin consequently binding to β-catenin to link the adherens junction with the intracellular actin cytoskeletal arrangement. The lack of catenin association with VE-cadherin destabilizes VE-cadherin mediated cell adhesion, which causes lack of cell-cell adhesion and leads to increases in endothelial permeability (Di Lorenzo et al. 2013, Iyer et al. 2004, Lampugnani et al. 1995). Whether there is impairment in cell-cell adhesion, and thus permeability function, of LECs upon exposure to ionizing radiation is unknown to date, a concern given the documented reports of cancer radiation therapy causing lymphedema as a side-effect that suggests impaired LEC barrier function (Mortimer et al. 1991, Rockson 2014).

Indeed, the endothelium appears to be the most radiosensitive cell type in the blood vasculature, wherein tissue exposure to clinically-relevant doses results in blood vessel damage evident within hours of irradiation (Wang et al. 2016). Apoptosis, increased permeability, edema, and lymphocyte infiltration are common features of such damage. Delayed blood vascular effects, such as capillary collapse, scarring, and fibrosis, can also become evident weeks or months after irradiation (Krishnan et al. 1988, Baker and Krochak 1989, Roth et al. 1999, Wang et al. 2016). The dermal lymphatics, which are predominantly a LEC-comprised lymphatic network, also have temporal-dependent changes in response to radiation, with initial impairments in lymphatic flow that recovers, but ultimately, impaired lymph flow and lymphedema returns months later (Mortimer et al. 1991, Avraham et al. 2010). However, it is not yet known if the impaired lymph flow in any prior investigation was due to lymphatic endothelial cell damage and changes in their functional phenotype. To our knowledge this is the first investigation identifying the dose-dependent responses of the lymphatic endothelial cells to acute ionizing radiation exposures and what those cellular responses mean to the fundamental role of the LEC in regulating microvascular barrier function and lymphatic function.

Methods:

Cell culture

Isolation of rat mesenteric lymphatic endothelial cells (RMLECs) was performed as previously described (Cromer et al. 2014). Briefly, male Sprague-Dawley rats were anesthetized by intramuscular injection of Diazepam (2.5 mg/kg) and InnovarVet (0.3 mL/kg). Innovar-Vet was a combination solution of droperidol (20 mg/ml) and fentanyl (0.4 mg/ml). A midline abdominal incision was made through the skin, underlying fascia, and abdominal muscle layers and a loop of small intestine, 7–8 cm long, was exteriorized through the incision. A single post-nodal lymphatic vessel was isolated from connective and fatty tissue (size ranged from 50 to 150 μm in diameter). The peripheral end of the lymphatic was cannulated and tied onto a glass pipette (80–100 μm tip diameter). Negative pressure was applied to the micropipette, resulting in the closure of the upstream valve, and the free end of the vessel was everted into the micropipette. While still everted within the micropipette, the ligature was loosened and the everted vessel carefully withdrawn from within the micropipette. The everted vessel was transferred and attached to a 35 mm 2% gelatin-coated tissue culture dish, containing Endothelial Growth Media (EGM) - 2MV at 37°C, 5% CO2, supplemented with 2% FBS, human Epidermal Growth Factor (hEGF), hydrocortisone, GA-1000 (Gentamicin, Amphotericin-B), Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor (VEGF), human Fibroblast Growth Factor-b (hFGF-b), rat Insulin-like Growth Factor 1 (rIGF1), and ascorbic acid in volume’s as per Lonza’s instructions. Endothelial cells were allowed to migrate off the vessels for ~1 week before the vessel was removed aseptically and cells were allowed to expand out. After the first passage of cells, they were then characterized and confirmed via positive staining for LEC specific markers; Lyve-1, podoplanin, VEGFR3 and PROX-1 (Abcam). Subsequently, the verified RMLEC (passaged up to 11 times) were maintained in culture under 5% CO2 in EGM-2MV and used from passage 6 to passage 11.

Irradiation

Irradiation by X-rays was performed at the TAMU Nuclear Science Center with the Norelco MG300 250-keV X-ray machine operating at 250 keV. The X-ray dose rates were set to 0.7 Gy/min. Dosimetry was measured by using a RadCal AccuPro dosimeter. Prior to being irradiated, all cells were serum-starved for 3 hours for cell cycle synchronicity, with cells kept in serum-free EGM-2MV (Lonza) during the radiation process. Cells were irradiated in doses from 0.5 to 2 Gy. After cells had been irradiated, they were quickly replenished with the standard EGM-2MV media used for culturing. Sham controls were serum-starved prior to being placed in corresponding radiation facilities while equipment was powered off and stored for an equivalent period of time equivalent to that of the maximum dose rate.

Immunofluorescence and Imaging

In brief for all immunofluorescence studies, RMLEC were plated onto 18 mm2, No. 1 slides (Electron Microscopy Sciences) and grown to confluence (approximately 5–7 days). After irradiation, cells were rinsed in PBS and fixed for 10 min with 4% paraformaldehyde at room temperature. Cells were subsequently washed three times in PBS buffer for 5 min. The fixed and permeabilized cells were then incubated for 1 h in 10% goat serum, followed by overnight incubation in primary antibodies (β-catenin, VE-cadherin, Santa Cruz) at 4C. The subsequent day, cells were washed three times for 5 min each and then were subsequently incubated in complementary secondary antibodies (Alexa Fluor 488-Goat anti-rabbit, Thermo Fisher) for 1 h at room temperature. This was followed with three more 5 min washes in PBS and then incubation for 20 min at room temperature in rhodamine phalloidin (1:40 from stock, Thermo Fisher) and 5 uM DRAQ7 (nuclear stain, Thermo Fisher). After this final incubation step, cells were washed again and mounted on glass slides using a Prolong® antifade (Thermo Fisher), allowed to cure overnight at room temperature, and imaged by Leica AOBS SP2 confocal microscopy (63×, 0.5 micron z-stack step sizes). Images were quantified via ImageJ v. 1.51, by importing images, splitting into appropriate color channels, and image analysis from sum-slice Z-projections. Individual cells were selected in the field of view via the polygon-selection tool and measured via analysis in ImageJ to obtain mean fluorescence intensity and area measurements. To ascertain changes in F-actin orientation, the ImageJ plug-in FibrilTool was utilized, which provides a quantitative description of anisotropy of fiber arrays and the average orientation per cell. Image analysis utilizing FibrilTool was performed as instructed (Boudaoud et al. 2014).

Permeability experiments

Monolayer barrier function assays were performed using 0.4 um pore cell culture inserts coated with 2% porcine gelatin placed in 24 well plates (BD falcon). These inserts were seeded at 70% confluence by area with RMLECs and allowed to grow to confluence for 2–3 days. Assays were performed at least 72 h after plating to ensure confluence was obtained and to allow RMLECs to establish a stable basement membrane and cell-to-cell contacts. Cells were then irradiated at the various doses. All experiments were repeated a minimum of 6 times. At 24- and 72-hours after irradiation, cell culture media was removed and replaced with experimental medium consisting of phenol-free EBM-2 (with 2% serum and pen/strep mix, Lonza) with 200 uL in the upper chamber and 600 uL in the lower chamber. After a 3-hr stabilization period in serum-free, growth-factor free EGM-2MV (Lonza), 10 uL of media containing 10 mg/mL of the FITC labeled bovine serum albumin (FITC-BSA, 66 kDa, Sigma-Aldrich) was added to the upper chamber and incubated for 30 minutes at 37 °C. During this 30 minute incubation step, FITC-BSA will translocate from the upper chamber to the lower chamber based on the monolayer permeability, to quantify FITC-BSA flux through the RMLEC monolayer. Thus, 10 uL aliquots of media were removed from the lower chamber and mixed with 90 uL Milli-Q water and placed in a 96 black-well fluorescence plate and read at the excitation and emission pair of 485 nm/528 nm on a Biotek synergy H1 micro plate reader. The fluorescence intensity correlates with the FITC-BSA concentration in the lower chamber, with a higher fluorescence intensity indicating elevated FITC-BSA concentration. Permeability was quantified at all radiation doses and normalized with respect to 0 Gy control, denoted and assessed as fold changes.

Cell Viability

A 96-well plate was set up for the cell viability assay using the XTT Cell Proliferation Assay (TACS) for timepoints subsequent to radiation: 0 h, 6 h, 24 h, 72 h, 120 h, 168 h, 216 h, and 264 h. Each timepoint had triplicate wells, and all wells had a plating density of 12500 cells based on a cell density calibration curve at the linear positive slope range of cell viability. Cells were plated in the 96-well plate 3 days prior to irradiation and were measured for XTT absorbance at each time via 490–630 nm absorbance readings by spectrophotometry.

Statistical Analyses

Statistical analyses were performed using RStudio v. 1.0.143 (R version 3.3.1). Data presented are expressed as mean +/− SEM. 1-way ANOVA were run at each time point, p < 0.05. If significant, pre-planned non-orthogonal contrast was performed by testing against 0 Gy control. Pre-planned non-orthogonal contrasts were used in the place of a traditional post hoc when comparing with the 0 Gy control versus within the irradiated groups (0.5, 1, 2 Gy). Regression analysis was completed testing RMLEC VE-Cadherin expression to RMLEC permeability.

Results:

Lymphatic endothelial cell adherens junctional protein disruption post-irradiation exposure

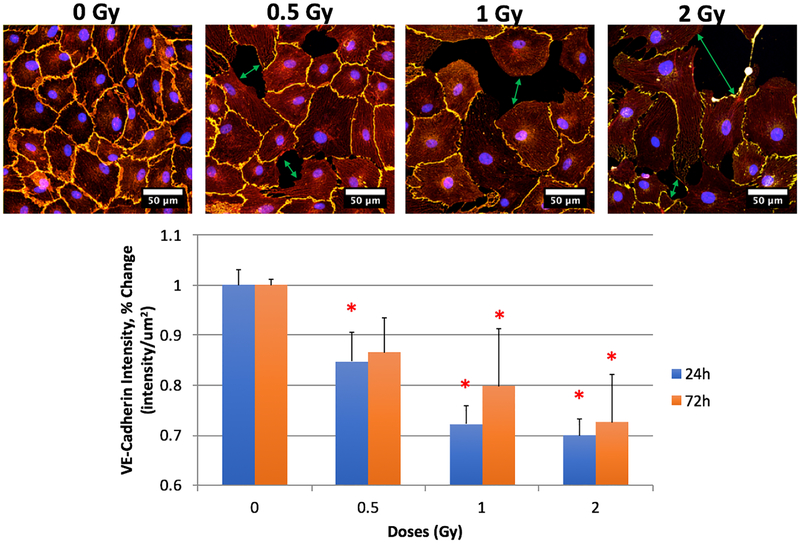

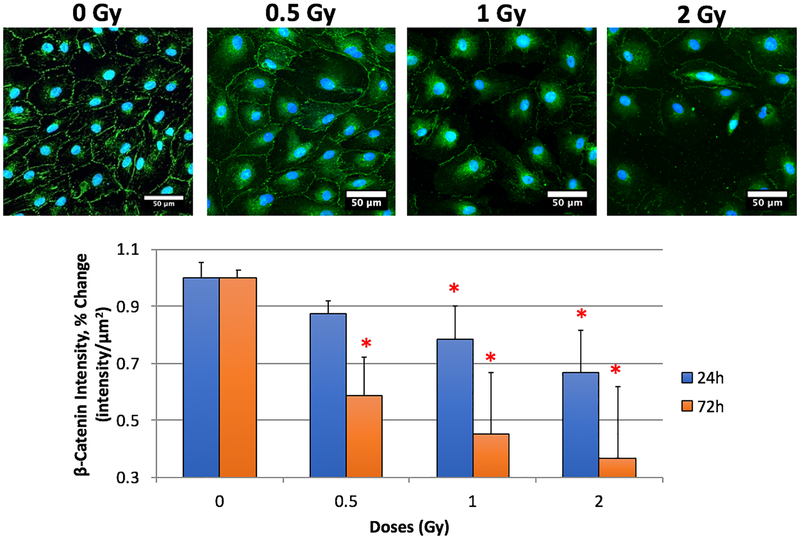

We assessed cellular localization and expression of VE-cadherin and β-catenin, critical protein components of the junctional complex responsible for maintaining endothelial barrier function. We noted significant changes post irradiation. Our sham controls expressed VE-cadherin and β-catenin at the cell membrane at both 24 h and 72 h as expected. We noted significant decreases in protein expression for both VE-Cadherin and β-catenin at all doses and at both 24 h and 72 h post-irradiation (Figures 1 and 2). These results suggest a loss of cell-cell adhesion amongst the RMLECs, which is observationally visible in the representative immunofluorescence images for both VE-Cadherin and β-catenin (Figures 1 and 2, top rows). Significant intercellular gaps formed at 0.5 Gy, which were more profound at 1 and 2 Gy exposures. These large gaps can lead to increased flux of macromolecules and fluid across the endothelial monolayer.

Fig. 1:

LEC expression of VE-cadherin and F-actin. Top row: VE-cadherin (yellow), F-actin (red), DRAQ7 (blue) representative images from 24h 0, 0.5, 1, and 2 Gy. Bottom: Expression changes of VE-Cadherin 24- and 72-hours after X-ray irradiation exposure. N = 3 per time-point + dose, p < 0.05 denoted by *, statistical difference from corresponding time-point 0 Gy control.

Fig. 2:

LEC expression of β-catenin. Top row: β-catenin (green), DRAQ7 (blue) representative images from 24h 0, 0.5, 1, and 2 Gy. Bottom: Expression changes of β-catenin 24- and 72-hours after X-ray irradiation exposure. N = 3 per time-point + dose, p < 0.05 denoted by *, statistical difference from corresponding time-point 0 Gy control.

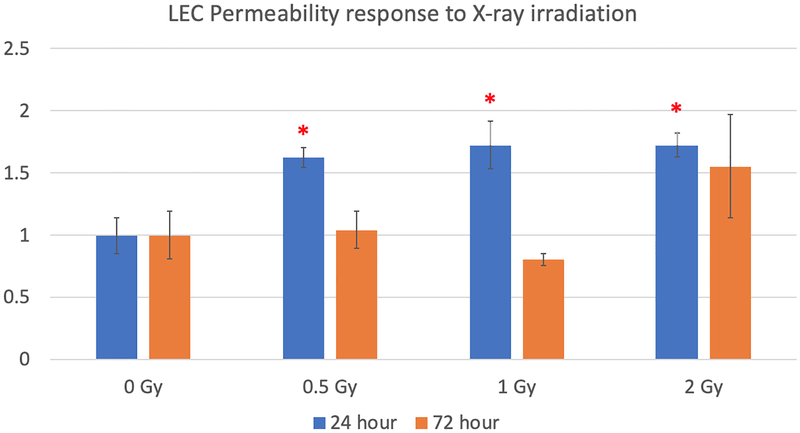

Single dose of irradiation induces elevated permeability in lymphatic endothelial cells

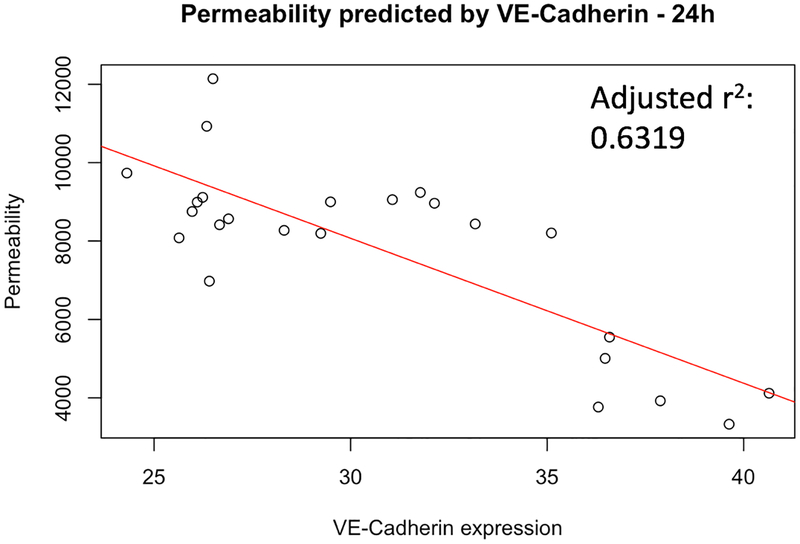

RMLEC radiation exposure led to disruption in VE-cadherin and β-catenin expression and reduced localization of these proteins for maintaining cell-cell adhesion at the cellular membrane. These data would suggest increased permeability and impaired barrier function. To assess RMLECs barrier function, we performed permeability assays after exposure to 0, 0.5, 1, and 2 Gy and characterized 24- and 72- hours post-irradiation. Indeed, we observed permeability increases of >50% at 0.5, 1, and 2 Gy 24 h post-irradiation compared to the 0 Gy control. The 2 Gy irradiated sample maintained this increase in permeability 72 h post-irradiation (Figure 3). Furthermore, a linear regression analysis supports VE-cadherin expression predicting ~63% of the variability in RMLEC permeability response to irradiation (R2 = 0.6479, see Figure 4).

Fig. 3:

LEC permeability response 24 h and 72 h post-irradiation. Data were normalized at corresponding time-point 0 Gy control. N = 6 per experiment, p < 0.05 denoted by *, statistical difference from corresponding time-point 0 Gy control.

Fig. 4:

VE-cadherin expression statistically predicts approximately 63% of the variability in RMLEC permeability response to irradiation (R2=0.6479, adjusted R2=0.6319, p = 2.106*10−6)

Cell-cell adhesion loss is tied to morphometry changes and cytoskeletal rearrangement

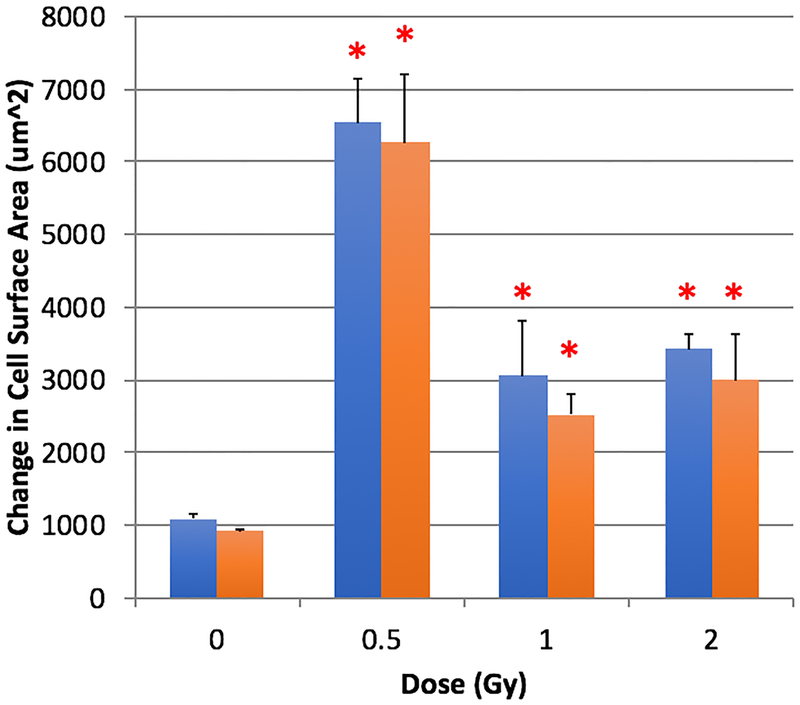

Impairments in cell-cell adhesion can lead to changes in cell morphometry as adherens junctions biochemically and mechanically interact with the intracellular cytoskeletal arrangement via catenin and F-actin interactions. We assessed cell morphology and orientation of the actin cytoskeleton after exposure to 0, 0.5, 1, and 2 Gy and characterized 24- and 72-h post irradiation. A quantifiable increase in absolute cell surface area was determined in irradiated cells (see Figure 5). Notably, 0.5 Gy at both 24 and 72 h post-irradiation demonstrated the greatest increase in absolute cell surface area, with 1 Gy and 2 Gy responses showing statistically elevated absolute cell surface area. Before irradiation, RMLECs were allowed to form a confluent, monolayer that orients each cells’ internal cytoskeleton architecture in a unilateral direction. However due to the loss of cell-cell adhesion and increase in cell surface area (which causes a radial expansion of the cell via its filopodia), a decrease in F-actin anisotropic homogeneity was statistically shown at 0.5, 1, and 2 Gy 24 h post irradiation (see Table 1). After 72 h, anisotropy values of cells exposed to 1 and 2 Gy were comparable or greater than the 0 Gy control, while the 0.5 Gy treated cells anisotropy remained statistically lower than the 0 Gy control (see Table 1).

Fig. 5:

Changes in absolute cell surface area 24- and 72-hours after X-ray irradiation exposure, p < 0.05 denoted by *, statistical difference from corresponding time-point 0 Gy control.

Table 1:

F-actin anisotropy determined FibrilTool, ImageJ plug-in. Anisotropy was calculated as instructions in Boudaoud et al. 2014. * denote statistical difference from 0 Gy control (p < 0.05) at corresponding time-point.

| F-actin Anisotropy | ||

|---|---|---|

| Dose (Gy) | 24h | 72h |

| 0 | 0.124 | 0.135 |

| 0.5 | 0.010* | 0.011* |

| 1 | 0.018* | 0.169* |

| 2 | 0.009* | 0.117 |

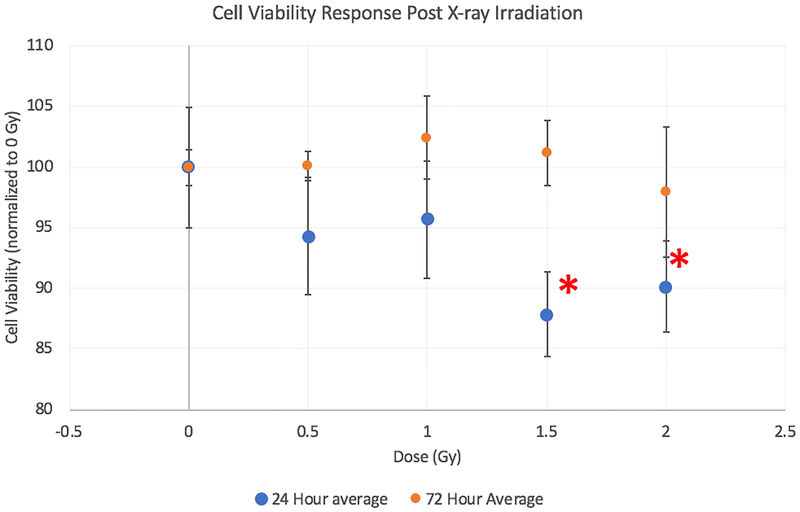

Reduced lymphatic endothelial cell viability post-irradiation

Endothelial function can be impaired even with a lack of cytotoxicity, as the endothelium are a slowly-dividing cell type. We assessed the sensitivity of RMLECs to irradiation via XTT cell viability assays to assess their metabolic response. We found reduced cell viability compared to 0 Gy control cells at 1.5 and 2 Gy 24 h post-irradiation and 2 Gy at 72 h post-irradiation. 72 h and later time points [data not shown] show a return to control values in cells exposed to irradiation (see Figure 6). Although 72 h post-irradiation showed a return to control metabolic activity, it is noteworthy that there remained decrements in adherens junctional protein expression and increased cell surface area 72 h post-irradiation.

Fig. 6:

Cell viability 24h after irradiation via XTT. N = 3 per dose, * denote statistical difference from 0 Gy control (p < 0.05) at corresponding time-point.

Discussion:

Understanding the response to radiation of lymphatic endothelium is critical in large part due to its investment in nearly every tissue in the body (in particular sites that are radiation sensitive such as the gastrointestinal system). This enhances lymphatic endothelium’s chances to be in a radiation field irrespective of site-directed or whole-body exposure. Furthermore, the lymphatic endothelium is critical for lymph formation and the transport of lymph from the lymphatic capillaries towards the lymphatic collecting vessels (Zawieja 2009). Lymphatic endothelial dysfunction consequently results in edema and inflammation. In the present study, we found significant increases in lymphatic endothelial monolayer permeability due to disruption of cell-to-cell adherens junctional protein structure and expression. Our study is the first to explore the effects of irradiation on the permeability of the lymphatic endothelium.

Vascular permeability describes the microvasculature’s capacity to allow transport of micro- (nutrients, ions, low molecular weight proteins, water, etc.) and macro- (large molecular weight proteins, cells) contents from the surrounding vessel environment into and out of the vessel lumen. The directionality and magnitude of transport of micro- and macro-contents in the blood and lymph are described by Starling forces (Huxley and Scallan 2011, Levick and Michel 2010). Albumin is the major macromolecule for maintaining oncotic pressure carried by blood that is transported to the interstitium as well carried away from the parenchymal tissues in lymph (Huxley and Scallan 2011, Levick and Michel 2010). We assessed in vitro FITC-BSA (66 kDa) flux across the RMLECs monolayer as an assessment of barrier function, and identified significant increases in FITC-BSA translocation 24 h and 72 h after low dose (≤ 2 Gy) radiation exposure (see Figure 3). In vitro experiments testing blood vascular permeability of blood-brain-barrier microvasculature and blood dermal microvasculature have also shown elevated permeability acutely (6 – 24 h) after irradiation with 70 kDa FITC-conjugated macromolecules at much higher doses (20 Gy X-ray) (Yuan et al. 2003, Gabrys et al. 2007). Various studies have shown blood vasculature permeability elevations in response to irradiation (although in the dose range of 5–20 Gy compared with here), in both in vitro cell culture and in vivo tissue beds (Mount and Bruce 1964, Song et al. 1966, Evans et al. 1986, Krishnan et al. 1988, Baker and Krochak 1989, Waters et al. 1996, Roth et al. 1999, Yuan et al. 2003, Sharma et al. 2013). These studies, as well as our findings, suggest both blood and lymphatic endothelium have functional impairments upon acute exposure to radiation. In particular, our in vitro RMLECs experiments showed permeability dysfunction at doses as low as 0.5 Gy. This may be of consideration in the context of radiation therapy, as treatment consist of multi-fractionated dose regimen delivery of 2 Gy fractions 5-times per week to an accumulative dose up to 50–70 Gy (Hellevik and Martinez-Zubiaurre 2014). Even at the low fraction deliveries, our data suggests the lymphatic endothelium may be fairly sensitive and thus negatively impacted.

To further assess the cellular mechanism of RMLEC monolayer disruption and increased permeability, we characterized the molecular regulators of their cell-cell adhesion, VE-cadherin and β-catenin adherens junctional protein configuration (see Figures 1 and 2). Previously in in vitro experiments of blood microvascular brain endothelial cells exposed to ≥5 Gy X-rays, a redistribution of VE-cadherin junctions tied with increased permeability was seen (Gabrys et al. 2007). Large cellular gaps were also observed in those experiments due to decreased cell-to-cell junctional protein expression (Gabrys et al. 2007). Indeed, in our studies of RMLECs exposed to comparably lower dose regiments (0.5 – 2 Gy), we see similar phenomena, with a linear regression model demonstrating approximately 63% of the variability in the RMLEC permeability response to irradiation was predicted by VE-cadherin expression. This indicates the level of VE-cadherin protein expression influences the degree of RMLEC permeability changes (see Figure 4). We also noted significant actin stress fiber redistribution that were associated with changes in cellular morphology (see Figure 5) and reduced anisotropic homogeneity of the F-actin orientation (see Table 1). These in vitro cellular morphology changes are directly tied to permeability and maintenance of a cellular monolayer via cell-cell interactions, for blood and lymphatic endothelial para-cellular permeability is modulated by two events: 1) intercellular junctional disruption, and 2) intracellular contraction of the actin/myosin cytoskeleton. The resultant para-cellular permeability is regulated by interplay of cell-cell adhesive forces, maintained by adherens junctional proteins such as VE-cadherin and β-catenin, against intracellular counter-adhesive forces, produced by interactions with actin (Lampugnani et al. 1995, Iyer et al. 2004, Mehta and Malik 2006, Hartsock and Nelson 2008). Here we see these forces are evidently disturbed in vitro in RMLECs by ionizing radiation exposure, with disruption in the typical, VE-cadherin, β-catenin, and F-actin organization after irradiation.

Our observations of LEC permeability dysfunction were at doses much lower than the blood vascular literature, perhaps due to prior blood vascular work not exploring low dose regiments, i.e. <2 Gy, or that there may be radiation sensitivity differences between blood and lymphatic endothelium. This could be may be attributed to the cell culture environment, as blood and lymphatic endothelium are both shear sensitive but are also exposed to vastly different flow environments. Hydrodynamic flow across blood and lymphatic endothelium and the resultant shear stress’ activate mechanotransduction signaling pathways that regulate both blood and lymphatic endothelial function and biology (Ng et al. 2004). Radiation injury to vascular endothelium under varying hydrodynamic-flow shear stress’ influence critical regulators of vascular function such as endothelial nitric oxide synthase (eNOS). Furthermore, eNOS protein expression is elevated in in vitro experiments of blood vascular endothelial cells exposed to ionizing radiation with and without shear, but under shear conditions, eNOS expression is much greater than without (Natarajan et al. 2016). eNOS-derived nitric oxide has also been shown to regulate in vitro blood vascular permeability through VE-Cadherin and Rho GTPase-dependent regulation of actin cytoskeletal arrangement (Di Lorenzo et al. 2013). It has been previously shown LECs, under varying in vitro shear conditions, release intracellular calcium that results in eNOS activation. Both eNOS and intracellular calcium dynamics regulate F-actin cytoskeletal mechanics, and consequently inter-cellular adhesive forces (Jafarnejad et al. 2015). Although we did not test varying flow conditions across the RMLEC monolayer in our experiments, LEC shear flow states may influence response to radiation exposure via eNOS interplay with inter- and intra-cellular forces regulated by VE-cadherin, β-catenin, and F-actin, a consideration of interest for future investigations.

Previously it has been shown that LECs have similar clonogenic survival curves as blood vascular endothelium, suggesting radiation sensitivity although fairly low overall (Kesler et al. 2014). Cell viability in our in vitro studies was lower at the high dose range 24 h (≥1.5 Gy) and 72 h (≥ 2 Gy, data not shown) but returned to comparable control values 120 h post-irradiation (data not shown). However, these were acute measurements and relatively low doses, with apoptosis and/or senescence not characterized specifically. Other in vivo studies have shown LEC apoptosis at much higher doses in the range of 15 – 30 Gy X-ray exposure (Avraham et al. 2010, Cui et al. 2014), but a minimum dose of 8–10 Gy has been suggested to induce apoptosis blood endothelial cells (Boström et al. 2018). Whether a similar minimum dose exists for LECs is unknown. We did not observe significant nuclear condensation and/or fragmentation at any doses via nuclear staining, but as LECs are a slowly-dividing cell type and apoptosis processes may not have yet been activated given our time-points and doses. Furthermore, our data supports significant functional implications even with modest changes in cell viability.

Study limitations include not assessing cell damage using specific markers of apoptosis, senescence, etc., or activated DNA repair mechanisms. Furthermore, upon identifying dose sensitivities in cultured LECs, characterizing this response in intact lymphatic vessels via in/ex vivo experiments in future investigations would lead to determining how lymphatic vessel permeability is influenced in response to radiation. In vivo studies of mouse lung lymphatic irradiation responses show decreased lymphatic capillary vessel density and increased apoptosis at 20 Gy X-ray exposures, which also leads to edema development 16-weeks after exposure (Cui et al. 2014). These in vivo results are supported by additional in vivo experiments with data reporting impaired lymph flow upon acute irradiation of tissues containing lymphatics (Mortimer et al. 1991, Avraham et al. 2010, Baker et al. 2014). None of these studies assessed lymphatic endothelial permeability specifically, but all describe edema development that suggests impaired lymphatic endothelial barrier function at doses ≥15 Gy. Whether these in vivo responses exist at much lower doses or different dosing regiments (i.e. fractionated) is unknown. In conclusion, our studies assessed the acute sensitivity of in vitro LEC irradiation and corresponding functional consequences. These findings provide a framework moving forward to ascertain the role of LECs in radiation-induced lymphedema and lymphatic permeability dysfunction.

Acknowledgments

Sources of support: This work was funded by NIH (Grant: U01HL123420). SAN was supported by the NASA-National Space Biomedical Research Institute Predoctoral Fellowship via NASA Cooperative Agreement NCC 9–58.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest Declaration: The authors report no conflicts of interest.

References:

- 1.Avraham T, Yan A, Zampell JC, Daluvoy SV, Haimovitz-Friedman A, Cordeiro AP, Mehrara BJ. 2010. Radiation therapy causes loss of dermal lymphatic vessels and interferes with lymphatic function by TGF-β1-mediated tissue fibrosis. American Journal of Physiology-Cell Physiology. 299(3):C589–605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Baker DG, Krochak RJ. 1989. The response of the microvascular system to radiation: a review. Cancer investigation. 7(3):287–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Baker A, Semple JL, Moore S, Johnston M. 2014. Lymphatic function is impaired following irradiation of a single lymph node. Lymphatic research and biology. 12(2):76–88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Boström M, Kalm M, Eriksson Y, Bull C, Ståhlberg A, Björk-Eriksson T, Hellström Erkenstam N, Blomgren K. 2018. A role for endothelial cells in radiation-induced inflammation. International journal of radiation biology. 94(3):259–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Boudaoud A, Burian A, Borowska-Wykręt D, Uyttewaal M, Wrzalik R, Kwiatkowska D, Hamant O. 2014. FibrilTool, an ImageJ plug-in to quantify fibrillar structures in raw microscopy images. Nature protocols. 9(2):457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cui Y, Wilder J, Rietz C, Gigliotti A, Tang X, Shi Y, Guilmette R, Wang H, George G, Nilo de Magaldi E, Chu SG. 2014. Radiation-induced impairment in lung lymphatic vasculature. Lymphatic research and biology. 12(4):238–50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cromer WE, Zawieja SD, Tharakan B, Childs EW, Newell MK, Zawieja DC. 2014. The effects of inflammatory cytokines on lymphatic endothelial barrier function. Angiogenesis. 17(2):395–406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Di Lorenzo A, Lin MI, Murata T, Landskroner-Eiger S, Schleicher M, Kothiya M, Iwakiri Y, Yu J, Huang PL, Sessa WC. 2013. eNOS-derived nitric oxide regulates endothelial barrier function through VE-cadherin and Rho GTPases. J Cell Sci. 126(24):5541–52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dorland YL, Huveneers S. 2017. Cell-cell junctional mechanotransduction in endothelial remodeling. Cellular and Molecular Life Sciences. 74(2), 279–292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Evans ML, Graham MM, Mahler PA, Rasey JS. 1986. Changes in vascular permeability following thorax irradiation in the rat. Radiation research. 107(2):262–71. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gabryś D, Greco O, Patel G, Prise KM, Tozer GM, Kanthou C. 2007. Radiation effects on the cytoskeleton of endothelial cells and endothelial monolayer permeability. International Journal of Radiation Oncology• Biology• Physics. 69(5):1553–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hartsock A, Nelson WJ. 2008. Adherens and tight junctions: structure, function and connections to the actin cytoskeleton. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA)-Biomembranes. 1778(3):660–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hellevik T, Martinez-Zubiaurre I. 2014. Radiotherapy and the tumor stroma: the importance of dose and fractionation. Frontiers in oncology. 4:1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Huxley V, Scallan J. 2011. Lymphatic fluid: exchange mechanisms and regulation. The Journal of Physiology. 589(12):2935–2943. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Iyer S, Ferreri DM, DeCocco NC, Minnear FL, Vincent PA. 2004. VE-cadherin-p120 interaction is required for maintenance of endothelial barrier function. American Journal of Physiology-Lung Cellular and Molecular Physiology. 286(6):L1143–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jafarnejad M, Cromer WE, Kaunas RR, Zhang SL, Zawieja DC, Moore JE Jr. 2015. Measurement of shear stress-mediated intracellular calcium dynamics in human dermal lymphatic endothelial cells. American Journal of Physiology-Heart and Circulatory Physiology. 308(7):H697–706. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kesler CT, Kuo AH, Wong HK, Masuck DJ, Shah JL, Kozak KR, Held KD, Padera TP. 2014. Vascular endothelial growth factor-C enhances radiosensitivity of lymphatic endothelial cells. Angiogenesis. 17(2):419–27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Krishnan L, Krishnan EC, Jewell WR. 1988. Immediate effect of irradiation on microvasculature. International Journal of Radiation Oncology• Biology• Physics. 15(1):147–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lampugnani MG, Corada M, Caveda L, Breviario F, Ayalon O, Geiger B, Dejana E. 1995. The molecular organization of endothelial cell to cell junctions: differential association of plakoglobin, beta-catenin, and alpha-catenin with vascular endothelial cadherin (VE-cadherin). The Journal of cell biology. 129(1):203–17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Levick JR, Michel CC. 2010. Microvascular fluid exchange and the revised Starling principle. Cardiovascular Research. 87: 198–210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Malek AM, Izumo S. 1996. Mechanism of endothelial cell shape change and cytoskeletal remodeling in response to fluid shear stress. Journal of cell science. 109(4):713–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mehta D, Malik AB. 2006. Signaling mechanisms regulating endothelial permeability. Physiological reviews. 86(1):279–367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mortimer PS, Simmonds RH, Rezvani M, Robbins ME, Ryan TJ, Hopewell JW. 1991. Time-related changes in lymphatic clearance in pig skin after a single dose of 18 Gy of X rays. The British journal of radiology. 64(768):1140–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mount D, Bruce WR. 1964. Local plasma volume and vascular permeability of rabbit skin after irradiation. Radiation research. 23(3):430–45. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Natarajan M, Aravindan N, Sprague EA, Mohan S. 2016. Hemodynamic flow-induced mechanotransduction signaling influences the radiation response of the vascular endothelium. Radiation research. 186(2):175–88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ng CP, Helm CL, Swartz MA. 2004. Interstitial flow differentially stimulates blood and lymphatic endothelial cell morphogenesis in vitro. Microvascular research. 68(3):258–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rockson SG. 2014. The Role of Lymph Node Irradiation in the Pathogenesis of Acquired Lymphedema. 65–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Roth NM, Sontag MR, Kiani MF. 1999. Early effects of ionizing radiation on the microvascular networks in normal tissue. Radiation research. 151(3):270–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sabine A, Agalarov Y, Maby-El Hajjami H, Jaquet M, Hägerling R, Pollmann C, Bebber D, Pfenniger A, Miura N, Dormond O, Calmes JM. 2012. Mechanotransduction, PROX1, and FOXC2 cooperate to control connexin37 and calcineurin during lymphatic-valve formation. Developmental cell. 22(2):430–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Scallan JP, Huxley VH. 2010. In vivo determination of collecting lymphatic vessel permeability to albumin: a role for lymphatics in exchange. The Journal of physiology. 588(1):243–54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sharma P, Templin T, Grabham P. 2013. Short term effects of gamma radiation on endothelial barrier function: uncoupling of PECAM-1. Microvascular research. 86:11–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Shen Q, Rigor RR, Pivetti CD, Wu MH, Yuan SY. 2010. Myosin light chain kinase in microvascular endothelial barrier function. Cardiovascular research. 87(2):272–80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Song CW, Anderson RS, Tabachnick J. 1966. Early effects of beta irradiation on dermal vascular permeability to plasma proteins. Radiation research. 27(4):604–15. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Waters CM, Taylor JM, Molteni A, Ward WF. 1996. Dose-response effects of radiation on the permeability of endothelial cells in culture. Radiation research. 146(3):321–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wang Y, Boerma M, Zhou D. 2016. Ionizing radiation-induced endothelial cell senescence and cardiovascular diseases. Radiation research. 186(2):153–61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Yang Y, Oliver G. 2014. Development of the mammalian lymphatic vasculature. The Journal of clinical investigation. 124(3):888–97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Yuan H, Gaber MW, McColgan T, Naimark MD, Kiani MF, Merchant TE. 2003. Radiation-induced permeability and leukocyte adhesion in the rat blood–brain barrier: modulation with anti-ICAM-1 antibodies. Brain research. 969(1–2):59–69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zawieja DC. 2009. Contractile physiology of lymphatics. Lymphatic research and biology. 7(2):87–96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]