Abstract

Background:

Researchers have demonstrated that maternal adverse childhood experiences (ACEs), such as abuse and neglect, are associated with prenatal risk factors and poor infant development. However, associations with child physiologic and health outcomes, including biomarkers of chronic or “toxic” stress, have not yet been explored.

Objectives:

The purpose of this study was to examine associations among past maternal experiences, current maternal posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) symptoms, and children’s indicators of exposure to chronic stress in a multiethnic sample of mothers and children at early school age (4 to 9 years).

Methods:

This cross-sectional study included maternal–child dyads (N = 54) recruited from urban community health centers in New Haven, CT. Mothers reported history of ACEs, family strengths, and current PTSD symptoms. Child measures included biomarkers, and health and developmental outcomes associated with chronic stress. Correlational and regression analyses were conducted.

Results:

Childhood trauma in mothers was associated with higher systolic blood pressure percentile (ρ = .29, p = .03) and behavioral problems (ρ = .47, p = .001) in children, while maternal history of family strengths was associated with lower salivary IL-1β (ρ = −.27, p = .055), salivary IL-6 (ρ = −.27, p = .054), and BMI z-scores (ρ = −.29, p = .03) in children. Maternal PTSD symptoms were associated with more child behavioral problems (ρ = .57, p < .001) and higher odds of asthma history (ρ = .30, p = .03).

Discussion:

Results indicate that past maternal experiences may have important influences on a child’s health and affect his or her risk for experiencing toxic stress.

Keywords: child health, mothers, mother–child relations, physiological, stress

Adverse childhood experiences (ACEs), including abuse, neglect, and household dysfunction, are alarmingly common. Almost half (45%) of all children in the United States have experienced at least one ACE, and the prevalence is even higher among Black (61%) and Hispanic (51%) children (Sacks & Murphey, 2018). ACEs not only disrupt childhood and adolescence, but are also associated with increased health risks across the lifespan including obesity, diabetes, smoking, substance abuse, cancer, and heart disease (Felitti et al., 1998; Hughes et al., 2017).

To further add to these concerns, researchers have recently demonstrated that the effects of ACEs may extend to subsequent generations. For example, maternal experiences of childhood maltreatment are associated with prenatal risk factors including depressive symptoms and psychosocial difficulties, increased risk for entering pregnancy with a chronic health condition, and increased risky behaviors during pregnancy like smoking, alcohol use, and illicit drug use (Chung et al., 2010; McDonnell & Valentino, 2016; Racine, Madigan, Plamondon, McDonald, & Tough, 2018). Maternal ACEs are associated with poor outcomes among children, including decreased birthweight and gestational age, developmental, physical, and emotional health problems during infancy, and developmental concerns during toddlerhood (Folger et al., 2018; Madigan, Wade, Plamondon, Maguire, & Jenkins, 2017; Racine et al., 2018; Smith, Gotman, & Yonkers, 2016; Sun et al., 2017).

The mechanisms linking maternal ACEs with pregnancy and child outcomes remain unclear, but may involve biological or psychosocial risk pathways (Madigan et al., 2017). This aligns with the literature on toxic stress and allostatic load, which suggests that exposure to chronic stressors over time may lead to altered development of the brain and multiple physiologic systems, and ultimately poor mental and physical health throughout the lifespan (Shonkoff et al., 2012). The ecobiodevelopmental (EBD) model also provides a framework for understanding the connections among a child’s ecology (social and physical environment), biology, and health/development (Shonkoff et al., 2012). Primary caregivers represent a critical component of the child’s social environment, and thus caregiver stress related to ACEs may become a source of environmental stress for the child. On the other hand, positive experiences in a caregiver’s childhood may protect against the adverse effects of maternal ACEs. For example, childhood family strengths, such as support and cohesion, are associated with less caregiver depression, posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) symptoms, and fewer stressful life events, which may in turn reduce stress experienced by children (Benzies & Mychasiuk, 2009; Narayan, Rivera, Bernstein, Harris, & Lieberman, 2018).

Despite growing evidence of the long-term and intergenerational effects of early childhood experiences, a number of gaps remain in the literature. To our knowledge, with the exception of the birth outcomes discussed above (Smith et al., 2016), associations between maternal ACEs and child physiology and health outcomes have not yet been examined. Maternal PTSD symptoms, which may reflect current manifestations of childhood or cumulative lifetime trauma, have likewise not been examined in association with child physiologic outcomes. Although family strengths are associated with positive psychosocial outcomes, associations with child biology also have not yet been explored.

While stress responses may play a key role in linking past maternal history with child health, the best biological indicators of chronic stress in children have not yet been defined (Condon, 2018a). Indicators of stress may include primary mediators of the stress response, such as glucocorticoids or cytokines, secondary outcomes of the stress response, including disruptions to immune, metabolic, or cardiovascular functioning, and tertiary endpoints that represent the downstream effects of chronic stress, such as behavioral problems or chronic disease (Condon, 2018a). In the current study, we examine feasible, noninvasive measures to represent primary, secondary, and tertiary outcomes across a range of physiologic systems in an effort to encompass the complexity of the stress response and gain insight into the biological pathways linking maternal history with child health.

Purpose

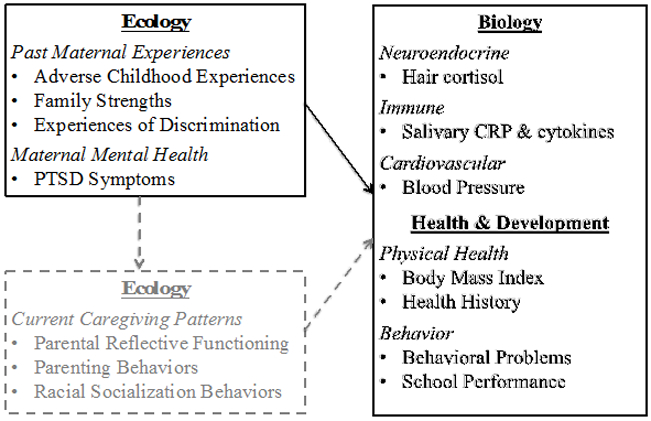

In this study, we examine data drawn from a larger exploratory study designed to examine risk and protective factors for toxic stress among low-income, multiethnic families (Condon et al., 2018b). The purpose of the current study is to examine associations among past maternal experiences (ACEs and family strengths), current maternal PTSD symptoms, and child indicators of exposure to chronic stress in a multiethnic sample of mothers and children (4 to 9 years old; Figure 1). Little is known about the extent to which maternal history influences children’s development beyond the prenatal and infancy periods; thus, an examination of the early school age period may provide insight into the long-term effects of exposure to maternal ACEs and family strengths (Condon et al., 2018b). With this exploratory approach, our goal is to determine effect sizes and generate hypotheses that will inform future research studies on the intergenerational transmission of stress and protective factors among vulnerable families.

Figure 1:

Conceptual Framework; Solid Boxes Indicate Variables Examined in Current Study (reprinted with permission from John Wiley and Sons).

Methods

Design, Sample & Setting

In this cross-sectional study, we recruited participants from the control group arm of Minding the Baby® (MTB), a randomized controlled trial (RCT) [ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT01458145] of a home visiting intervention for first-time mothers with risk factors including poverty, history of trauma, or young maternal age (Ordway et al., 2014; Sadler et al., 2013). Participants were eligible for inclusion in the current study if (a) the child was between 4–9 years of age at the time of data collection; (b) the child’s mother had custody or regular contact with the child; (c) the dyad was residing within the state; and (d) the dyad participated in the control group arm of the MTB RCT. Of 83 families eligible for participation, we recruited 65% (N = 54) and enrolled them in the study. Others could not be reached (n = 13), declined to participate (n = 2), did not meet inclusion criteria (n = 7), or expressed interest, but never scheduled a visit (n = 7). For the complete study protocol, see Condon et al. (2018b).

Procedures

We obtained institutional review board approval from Yale University prior to data collection. Parents provided informed consent and permission to talk with the child, and children ages 7 to 9 years provided assent (Committee on Bioethics, 1995). Consistent with the original MTB study, dyads were compensated $50 for their time.

Variables and Measures

Maternal history of childhood trauma and family strengths.

We measured past maternal history with the Childhood Trauma Questionnaire (CTQ), a retrospective self-report measure used to identify childhood history of abuse and neglect. The 28-item CTQ includes a total score and five subscales: sexual abuse, physical abuse, emotional abuse, physical neglect, and emotional neglect (Bernstein et al., 1994). Following the methods used by Hillis et al. (2010), an additional subscale assessing family strengths was created by using seven items on the CTQ related to family protective factors (e.g. “I felt loved” and “I had someone to take me to the doctor”). Though this subscale has not yet been validated, it was successfully used to examine protective factors for adolescent pregnancy within the original ACEs cohort (Hillis et al., 2010). Internal consistency of the CTQ was high (α = .83 - .96).

Maternal PTSD symptoms.

We measured maternal PTSD symptoms with the PTSD Checklist – Civilian Version (PCL-C); a 17-item self-report instrument used to evaluate the presence of PTSD symptoms over the past month (Weathers, Litz, Herman, Huska, & Keane, 1993). Internal consistency of the PCL-C was high (α =.94).

Children’s indicators of exposure to chronic stress.

Primary mediators of the stress response.

Cortisol.

Hair cortisol is a noninvasive indicator of long-term HPA axis activity and neuroendocrine functioning (Meyer, Novak, Hamel, & Rosenberg, 2014). We cut a 3cm sample of hair from the posterior vertex of the child’s scalp to represent systemic cortisol exposure from the past three months. Information on hair color, product use, frequency of hair washing, and corticosteroid use was recorded. Hair cortisol was analyzed using a high-sensitivity enzyme immunoassay kit (Meyer et al., 2014).

Inflammatory cytokines.

We measured a panel of four pro-inflammatory cytokines [interleukin-1 beta (IL-1β), interleukin-6 (IL-6), interleukin-8 (IL-8), and tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF)] with saliva to assess children’s immune functioning (Haddad, Saadé, & Safieh-Garabedian, 2002). Saliva was primarily collected using a passive drool device (n = 47), but oral swabs were used when necessary based on developmental capabilities (n = 7). A gross oral exam was conducted prior to saliva collection by the principal investigator (PI), an advanced practice nurse, and notable findings (sores, dental caries, loose/missing teeth) were recorded (Riis et al., 2016). The cytokine panel was analyzed using a 4-plex electrochemiluminescence immunoassay, and intra-assay coefficients of variability were acceptable (2.8–6.9%).

Secondary outcomes of the stress response.

Cardiovascular.

Salivary c-reactive protein (CRP) and systolic (SBP) and diastolic (DBP) blood pressure were measured to assess cardiovascular functioning (Cook et al., 2000; Muntner, He, Cutler, Wildman, & Whelton, 2004). Salivary CRP was collected according to saliva collection methods described above and analyzed via enzyme immunoassay. Blood pressure was measured by the PI with a calibrated manual sphygmomanometer after 5 minutes of rest. Three seated measurements were taken at least 1 minute apart and percentiles were calculated based on age, height, and gender (Bird & Michie, 2008). Efforts were made to obtain salivary and blood pressure measurements at the same time of day for each child to account for diurnal variation.

Anthropometric measurements.

Children’s height and weight were measured with a calibrated stadiometer and scale. Body mass index (BMI) percentiles and z-scores were determined based on age and gender-appropriate Centers for Disease Control and Prevention growth charts (Kuczmarski, 2002).

Tertiary endpoints of the stress response.

Physical health.

Mothers reported on children’s health history and healthcare utilization, including chronic illnesses, medication use, and frequency of emergency department (ED) visits, injuries/accidents, and hospitalizations.

Behavior and school performance.

Child behavior was assessed using age-appropriate parent-report versions of the Child Behavior Checklist (CBCL), a 99-item questionnaire designed to assess total, internalizing (anxious, depressive) and externalizing (aggressive, hyperactive) behavior problems (Achenbach & Ruffle, 2000). Mothers reported on children’s school performance using the CBCL academic background section. Cronbach’s alpha was high in the current study (α = .90 - .95).

Laboratory Procedures

Hair and saliva samples were deidentified and stored in a secure location immediately after collection. Hair samples were stored at room temperature and saliva samples were stored in a subzero freezer at < 20 degrees. See Condon et al. (2018b) for more information on collection and storage procedures.

Data Analysis

We analyzed all data using SAS 9.4®. Data were normally distributed for child BMI, DBP percentile, total behavior problems, and internalizing behaviors. Natural log-transformations were applied to improve the normality of the distributions of salivary cytokines, hair cortisol, and externalizing behavior problems. Distributions of the remaining variables did not improve with transformations.

For all child indicators of toxic stress, two-sample t-tests were used to compare differences by child gender, age group, and race/ethnicity. We dichotomized child age into two groups (4–6 years and 7–9 years) based on developmental stage and data distribution. Race/ethnicity was categorized as Hispanic, non-Hispanic Black, and other/mixed race; however, we did not use the other/mixed race group for comparison analyses due to small sample size (n < 5).

Biomarker analyses.

We examined biomarkers for factors that may confound results, such as local oral inflammation or hair-care routines. We used two-sample t-tests to compare salivary biomarker levels for children with and without missing teeth, loose teeth, unfilled caries, recent dental work (past 1 week), and other mouth issues (crowns, fillings, braces). Using two-sample t-tests or analysis of variance (ANOVA) tests, we compared hair cortisol levels for differences by hair shape (curly, wavy, straight), color, style, washing frequency, product use, length (if hair < 3cm) and corticosteroid use. Factors associated with significantly different biomarker levels were controlled for in regression analyses.

Missing biomarker data.

One family chose not to participate in the biomarker portion of the study. We excluded salivary biomarkers for one child due to a diagnosis of streptococcal pharyngitis within 2 days of the research visit, and the laboratory reported that saliva quantity was not sufficient for one child on all salivary biomarkers and for another child on CRP only. Hair samples were not obtained on eight children due to shaved hairstyles; one due to parent refusal, and four hair samples were excluded for reported corticosteroid use.

Correlation and regression analyses.

We used Spearman’s rank (ρ), a nonparametric measure of correlation, to examine associations between the maternal and child variables. Due to the exploratory nature of the study, we did not adjust for multiple hypothesis testing due to the risk of missing an association. For all correlations with a p-value of less than .1, regression analyses were conducted with past maternal history and PTSD symptoms as the independent variables and child measures as the dependent variables. Simple linear regressions were conducted for continuous dependent variables (biomarkers, BMI, blood pressure, CBCL) and simple logistic regressions were conducted for dichotomous dependent variables (health history). For dichotomous health and school outcomes, post-hoc power analyses indicated a frequency of 25% (n > 13) was necessary to detect associations using logistic regression. Thus, analyses were not conducted where the absolute numbers were very small and calculated effect sizes unlikely to be meaningful; this excluded some health history, healthcare utilization, and academic history variables.

Sample size and power.

The relationships in this study have not previously been examined, and thus there was little information from which to estimate effects and statistical power for the sample. Based on previous findings of correlations between maternal depression and hair cortisol (r = .22) in a multiethnic sample of young children (n = 297) (Palmer et al., 2013), we expected our correlation analyses to be underpowered (power = .39 - .45), based on the available sample. However, the goal of this exploratory study was to examine the size of the correlational effects, rather than to obtain statistically significant effects. Though we considered a p-value of .05 to be the significance level for this study, correlations with p-values between .05 and .1 are also highlighted, as these effect sizes may be useful for future research.

Results

Fifty-four maternal-child dyads completed data collection (Table 1). Approximately half identified as Hispanic, with Puerto Rican as the most frequently reported ethnic group (n = 21), and half identified as Black or mixed race. Mothers ranged in age from 19 to 33 years, with a mean of 26.8 (SD = 3.3) years, and mean child age was 6.7 (SD = 2.1) years. Most mothers were single (68%), and all reported receiving some form of public assistance.

Table 1.

Demographic Characteristics of Mothers and Children in the Study Sample

| Characteristic | Mothers | Children | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean (SD) | Range | Mean (SD) | Minimum- Maximum |

|

| Age (years) | 26.8 (3.3) | 19.3 – 33.9 | 6.7 (2.1) | 4 – 9 |

| Education (years) | 13.0 (1.6) | 10 – 16 | 3.2 (2.0) | 0 – 6 |

| n | % | n | % | |

| Grade Level | ||||

| Not enrolled/Other | 6 | 11.1 | ||

| Pre-K to First grade | 27 | 50.0 | ||

| Second to Fourth Grade | 21 | 38.9 | ||

| Race | ||||

| White | 14 | 25.9 | 9 | 16.7 |

| Black | 26 | 48.1 | 27 | 50.0 |

| Other | 14 | 25.9 | 18 | 33.3 |

| Hispanic Ethnicity | 27 | 50 | 28 | 51.9 |

| Hispanic Cultural Group | ||||

| Puerto Rican | 21 | 77.8 | 20 | 71.4 |

| Mexican | 2 | 7.4 | 2 | 7.1 |

| Other/Multiple Groups | 4 | 14.8 | 6 | 21.4 |

| Marital Status | ||||

| Single | 37 | 68.5 | ||

| Married | 12 | 22.2 | ||

| Living Together | 5 | 9.3 | ||

Child Indicators of Exposure to Chronic Stress

Descriptive statistics for child indicators of exposure to chronic stress are presented in Table 2. Very few measures were significantly different by child sex, age, or race/ethnicity; of these, none were included in correlations that met criteria for conducting regression analyses (p-value less than .1). For this reason, as well as the small study sample size, we did not adjust for these characteristics in the regression models.

Table 2.

Descriptive statistics on Maternal Report Measures, Child Biomarkers & Child Health/School History

| Variables | n | Mean | SD | Possible Range |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Maternal Report Measures | ||||

| Childhood Trauma Questionnaire | ||||

| Total Score | 54 | 45.6 | 20.6 | 28 – 140 |

| Sexual Abuse | 53 | 7.77 | 5.61 | 5 – 25 |

| Physical Abuse | 54 | 8.62 | 4.28 | 5 – 25 |

| Emotional Abuse | 54 | 10.5 | 5.5 | 5 – 25 |

| Physical Neglect | 54 | 7.83 | 4.10 | 5 – 25 |

| Emotional Neglect | 54 | 10.7 | 5.4 | 5 – 25 |

| Family Strengths | 54 | 28.0 | 7.0 | 7 – 35 |

| PTSD Checklist-Civilian | 54 | 35.0 | 15.7 | 17 – 85 |

| Child Behavior Checklist (t-scores)7 | ||||

| Total Score | 54 | 52.5 | 11.1 | 0 - 100 |

| Internalizing Behaviors | 54 | 51.6 | 9.9 | 0 - 100 |

| Externalizing Behaviors | 54 | 51.1 | 10.9 | 0 - 100 |

| Child Biomarkers | n | Mean | SD | Sample Range |

| Salivary IL-1B | 51 | 79.24 | 108.27 | 4.84 – 675.82 |

| Salivary IL-6 | 51 | 9.13 | 11.74 | 0.88 – 61.97 |

| Salivary IL-8 | 51 | 903.03 | 978.42 | 113.70 – 4061.92 |

| Salivary TNF | 51 | 5.37 | 5.71 | 0.61 – 30.33 |

| Salivary CRP | 50 | 14413.57 | 24195.58 | 1228.17 – 95571.74 |

| Hair cortisol | 41 | 57.25 | 112.67 | 1.38 – 598.2 |

| Child Health & School History | ||||

| BMI z-score | 54 | 0.75 | 1.13 | −2.54 – 2.97 |

| Systolic Blood Pressure Percentile | 53 | 63.73 | 22.16 | 16 - 99 |

| Diastolic Blood Pressure Percentile | 53 | 71.24 | 15.71 | 29 - 99 |

| Number of ED visits | 35 | 3.03 | 2.84 | 1 - 10 |

| n | % | |||

| Child BMI Category* | ||||

| Underweight (<5%) | 2 | 3.7 | ||

| Normal weight | 28 | 51.8 | ||

| Overweight (85–94%) | 11 | 20.3 | ||

| Obese (>=95%) | 13 | 24.1 | ||

| Child Blood Pressure Category** | ||||

| Prehypertension | 3 | 5.56 | ||

| Hypertension | 5 | 9.36 | ||

| Child Health History | ||||

| Asthma | 15 | 27.8 | ||

| Food Allergies† | 11 | 20.4 | ||

| Seasonal Allergies | 14 | 25.9 | ||

| Eczema | 19 | 35.2 | ||

| Child Healthcare Utilization | ||||

| Ever Visited ED | 35 | 64.8 | ||

| Ever Hospitalized† | 6 | 11.1 | ||

| Ever Had Accident† | 9 | 16.7 | ||

| Ever Had Surgery† | 9 | 16.7 | ||

| Child Academic History | ||||

| Learning Problems† | 10 | 18.5 | ||

| Repeated Grade† | 6 | 11.1 | ||

| Special Education Services† | 8 | 14.8 | ||

| Other School Problems† | 7 | 12.9 |

Note:

Percentiles calculated according to CDC Guidelines for age and gender (Kuczmarski, 2002);

According to the Fourth Report on the Diagnosis, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Pressure in Children and Adolescents (Falkner et al., 2004);

=Not included in correlation analyses per post-hoc power analyses.

Biomarker confounders.

Analyses of salivary biomarkers revealed no significant differences in IL-1β, IL-8, TNF or CRP levels for children with missing teeth (n = 13), loose teeth (n = 18), unfilled caries (n = 6), recent dental work (n = 5) or other mouth issues (n = 6) compared with children who did not have these characteristics. Significant differences in IL-6 levels were noted in children with unfilled caries (t = 2.34, p = .02) when compared with the rest of the sample, and this was subsequently adjusted for in regression analyses. Hair cortisol levels differed by hair shape (F = 9.49, p = .001) and frequency of hair washing (F = 4.15, p = .008), but correlations including this measure did not meet criteria for conducting regression analyses (p-value <.1).

Maternal Characteristics

Descriptive statistics for maternal self-report measures are reported in Table 2. For adverse childhood experiences, mean CTQ subscale scores are presented in Table 2, but this instrument can also be used to evaluate ACEs according to standardized cutoff scores (see Bernstein et al., 1994). Using this method, 18% of mothers reported low to moderate levels of childhood trauma, 22% reported moderate to severe levels, and 15% reported severe to extreme levels. By type of abuse, 28% of mothers reported a history of sexual abuse, 52% reported physical abuse, 48% reported emotional abuse, 33% reported physical neglect, and 43% reported emotional neglect. On the PCL-C, 28% of mothers met DSM criteria for PTSD (Weathers et al., 1993).

Correlations Among Study Variables

Maternal ACEs and child indicators of exposure to chronic stress.

Higher maternal childhood trauma (CTQ total score) and emotional abuse scores were associated with significantly higher systolic blood pressure percentiles in children (ρ = .29, p = .03 and ρ = .28, p = .04, respectively). Small to moderate effect sizes were detected for associations between maternal childhood trauma (all types) and child total (ρ = .29 to 0.52, p < .001 to .03), internalizing (ρ = .18 to 0.51, p < .001 to 0.2), and log-transformed externalizing (ρ= .23 to .43, p < .001 to .09) behavioral problems.

We found other associations with small but notable effect sizes, including between maternal childhood sexual abuse and log-transformed child IL-6 levels (ρ = .24, p = .09), maternal childhood physical abuse and child history of allergies (ρ = .25, p = .06), and maternal emotional abuse history and child asthma history (ρ = .25, p = .06). Child systolic blood pressure percentiles were associated with higher maternal history of childhood physical abuse (ρ = .25, p = .07) and emotional neglect (ρ = .23, p = .09), and increased child diastolic blood pressure percentiles were associated with higher maternal CTQ total score (ρ = .27, p = .054) and childhood sexual abuse history (ρ = .23, p = .09). Correlations are presented in Table 3 and regression models are presented in Table 4.

Table 3.

Spearman Correlations between Maternal Variables (Past Maternal Experiences, PTSD Symptoms) and Child Variables (Primary Mediators, Secondary Outcomes & Tertiary Endpoints Associated with Chronic Stress)

| Measure | CTQ Total Score |

CTQ Sexual Abuse |

CTQ Phys. Abuse |

CTQ Emot. Abuse |

CTQ Phys. Neglect |

CTQ Emot. Neglect |

CTQ Family Strengths |

PTSD Checklist |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Primary Mediators | ||||||||

| IL-1Ba | −.06 | .03 | .15 | −.14 | −.08 | −.14 | −.27** | −.27** |

| IL-6a | −.10 | .24**† | .09 | .03 | .08 | .05 | −.27**† | .10 |

| IL-8a | .02 | .06 | .14 | .01 | −.08 | −.10 | −.18 | .01 |

| TNFa | .11 | .06 | .20 | .07 | .11 | .01 | −.18 | −.04 |

| Hair cortisola | −.02 | −.12 | −.08 | −.05 | .12 | .06 | −.04 | −.09 |

| Secondary Outcomes | ||||||||

| CRP | −.05 | −.08 | −.14 | .02 | −.01 | −.04 | .12 | .19 |

| BMI | .11 | .05 | .16 | .08 | −.02 | .09 | −.29* | .05 |

| SBP % | .29* | .21 | .25** | .28* | .19 | .23** | −.05 | .23 |

| DBP % | .27** | .23** | .13 | .13 | .19 | .22 | −.01 | .08 |

| Tertiary Endpoints | ||||||||

| Asthma | .22 | .11 | .08 | .25** | .11 | .21 | .05 | .30* |

| Seasonal Allergies | .13 | −.08 | .25** | .18 | .16 | .19 | .07 | .08 |

| Eczema | −.11 | −.02 | −.16 | −.05 | −.01 | −.09 | −.36* | −.09 |

| Ever Visited ED | −.13 | −.13 | −.13 | −.09 | −.08 | −.04 | .14 | −.08 |

| No. of ED Visits | −.15 | −.13 | −.18 | −.01 | −.03 | −.07 | −.12 | .11 |

| CBCL Total | .47* | .31* | .48* | .52* | .29* | .35* | .09 | .57* |

| CBCL Internalizing | .51* | .18 | .41* | .51* | .29* | .37* | .02 | .64* |

| CBCL Externalizinga | .33* | .32* | .43* | .41* | .23** | .28* | .07 | .41* |

Note:

p<.05;

p<0.1;

=see Table 4 for adjusted model;

= variable was log transformed; BMI=body mass index; SBP=systolic blood pressure; DBP=diastolic blood pressure; %=Percentile; IL = Interleukin; TNF = Tumor Necrosis Factor-alpha; CRP = C-reactive Protein; ED = Emergency Department; CBCL = Child Behavior Checklist; CTQ=Childhood Trauma Questionnaire.

Table 4.

Regression Analyses between Maternal Independent Variables (Past Maternal Experiences and PTSD Symptoms) and Child Dependent Variables (Indicators of Exposure to Chronic Stress)

| Independent Variable |

Dependent Variable | n | B | P | R2 | Regression model |

Odds Ratio (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CTQ Totala | SBP % | 53 | 16.22 | .02 | .10 | Linear | |

| DBP % | 53 | 9.31 | .07 | .06 | Linear | ||

| CBCL total | 54 | 13.05 | .0001 | .25 | Linear | ||

| CBCL internalizing | 54 | 11.77 | .0001 | .25 | Linear | ||

| CBCL externalizinga | 54 | 0.18 | .007 | .13 | Linear | ||

| CTQ Sexual Abuseb | IL-6a | 51 | 0.36 | .16 | .14 | Linearc | |

| CBCL total | 54 | 8.31 | .01 | .12 | Linear | ||

| CBCL externalizinga | 54 | 0.16 | .01 | .11 | Linear | ||

| CTQ Physical Abusea | SBP % | 53 | 13.74 | .06 | .07 | Linear | |

| Seasonal allergies | 54 | 0.08 | .24 | N/A | Logistic | 1.08 [0.95, 1.23] | |

| CBCL total | 54 | 12.45 | .0004 | .22 | Linear | ||

| CBCL internalizing | 54 | 11.63 | .0002 | .24 | Linear | ||

| CBCL externalizinga | 54 | 0.18 | .008 | .13 | Linear | ||

| CTQ Emotional Abuse | SBP % | 53 | 1.35 | .01 | .11 | Linear | |

| Asthma | 1.15 | .07 | NA | Logistic | |||

| CBCL total | 54 | 1.14 | <.0001 | .32 | Linear | ||

| CBCL internalizing | 54 | 1.06 | <.0001 | .35 | Linear | ||

| CBCL externalizinga | 54 | 0.02 | .002 | .16 | Linear | ||

| CTQ Physical Neglectb | CBCL total | 54 | 8.97 | .004 | .15 | Linear | |

| CBCL internalizing | 54 | 9.27 | .0007 | .20 | Linear | ||

| CBCL externalizinga | 54 | 0.12 | .08 | .06 | Linear | ||

| CTQ Emotional Neglect | SBP % | 53 | 1.07 | .053 | .07 | Linear | |

| Asthma | 0.10 | .07 | N/A | Logistic | 1.11 [0.99, 1.23] | ||

| Seasonal allergies | 0.10 | .08 | N/A | Logistic | 1.11 [0.98, 1.24] | ||

| CBCL total | 54 | 0.86 | .001 | .18 | Linear | ||

| CBCL internalizing | 54 | 0.91 | .0001 | .25 | Linear | ||

| CBCL externalizinga | 54 | 0.01 | .03 | .08 | Linear | ||

| CTQ Family Strengths | BMI z-score | 54 | −0.04 | .06 | .07 | Linear | |

| IL-1b a | 51 | −0.88 | .07 | .07 | Linear | ||

| IL6 a | 51 | −0.87 | .02 | .15 | Linearc | ||

| Eczema | −0.12 | .008 | N/A | Logistic | 0.89 [0.81, 0.96] | ||

| PTSD Checklist | IL-1B a | 51 | −0.63 | .06 | .07 | Linear | |

| Asthma | 54 | 0.05 | .03 | N/A | Logistic | 1.05 [1.01, 1.08] | |

| CBCL Total | 54 | 15.84 | <.0001 | .37 | Linear | ||

| CBCL Internalizing | 54 | 15.01 | <.0001 | .41 | Linear | ||

| CBCL Externalizinga | 54 | 0.21 | .001 | .17 | Linear |

Note:

= variable was log transformed;

= scale dichotomized (none/minimal abuse or greater than minimal abuse) for regression analyses due to frequency of low values;

= controlled for unfilled caries. BMI z-score adjusted for age and sex. Regression analyses only conducted for correlations with significant (<.05) or near significant (<.1) p-values.

Maternal history of family strengths and child indicators of exposure to chronic stress.

Maternal history of childhood family strengths was associated with significantly lower BMI (ρ = −.29, p = .03) and lower odds of eczema (ρ = −.36, p = .007) in children. Though not statistically significant, greater history of family strengths in mothers was also correlated with lower log-transformed IL-1β (ρ = −.27, p = .055) and log-transformed IL-6 (ρ = −.27, p = .054) levels in their children. Of note, the association between family strengths and log-transformed IL-6 levels became significant when controlling for unfilled dental caries (β = −.87, p = .02) (Table 4).

Maternal PTSD symptoms and child indicators of exposure to chronic stress.

Maternal PTSD symptoms were associated with significantly higher CBCL total (ρ = .57, p < .0001), internalizing (ρ = .64, p < .0001) and log-transformed externalizing behavior scores (ρ = .41, p = .002) in children. Maternal PTSD symptoms were also associated with higher odds of child asthma history (ρ = .30, p = .03).

Discussion

The results of this exploratory study suggest that past maternal experiences may influence a child’s risk for experiencing toxic stress, as maternal ACEs were associated with higher blood pressure levels and behavioral problems in children, while family strengths were associated with lower BMI and inflammatory markers in children. While the effect sizes detected were generally small, this is consistent with effects detected in other pediatric biomarker studies and reflects the complexity of factors that influence developing physiology (Condon, 2018a). Though additional research is needed, these findings indicate that immune and metabolic pathways may be important physiologic mechanisms linking past maternal experiences with child health. Here we discuss some potential psychosocial pathways through which maternal ACEs and trauma history may lead to increased stress and disrupted physiological development in children.

The results of this study suggest that the influence of maternal ACEs is not limited to the prenatal or infancy period, but may continue through preschool and the early school age years. Maternal history of trauma is associated with use of corporal punishment and hostile-intrusive and frightening parenting behaviors (Chung et al., 2009; Jacobvitz, Leon, & Hazen, 2006); thus, in some cases, mothers with a history of ACEs may themselves become a source of stress for their child. In this way, negative or unpredictable parenting and disrupted maternal–child relationships may be important pathways through which maternal ACEs lead to increased risk for toxic stress responses in children.

Prevention of the negative effects associated with toxic stress requires the presence of a supportive, nurturing caregiver to help buffer stressful experiences for the child (Shonkoff et al., 2012). However, this parental buffering may be very challenging for mothers with unresolved trauma stemming from childhood experiences. Mothers with a history of ACEs may be emotionally unavailable, experience more parenting stress, and exhibit less sensitive parenting, and therefore may have difficulty providing a nurturing environment and secure base to encourage healthy child development (Pereira et al., 2012). As these mothers likely experienced toxic stress during their own childhood, they also may be poorly equipped to protect their children from stressful experiences or teach effective coping skills in the presence of stressors.

When pregnant women are exposed to stressful environments, child exposure to toxic stress can begin as early as the prenatal period. However, recent evidence suggests that this may not be limited to only mothers’ current stressors; in a study of pregnant women (N = 185), Bublitz, Parade, and Stroud (2014) found that maternal history of severe childhood sexual abuse was associated with increased cortisol awakening response between 25 and 35 weeks gestation. This suggests that maternal history of ACEs may not only affect children through risky maternal behaviors or a disrupted maternal–child relationship, but through prenatal exposure to mothers’ disrupted stress-response systems and altered epigenetic programming (Glover, O’Connell, & O’Donnell, 2010).

Finally, the results of this study also suggest an intergenerational transmission of protective factors in families at risk for toxic stress. Sometimes referred to as “angels in the nursery,” positive childhood experiences may help caregivers to interrupt the cyclical nature of trauma (Lieberman, Padrón, Van Horn, & Harris, 2005). The benefits derived from positive parenting role models or family support may in turn enhance mothers’ capacities to help their own children cope with environmental stressors (Benzies & Mychasiuk, 2009). Family strengths may also indicate that mothers experienced less toxic stress during their own childhoods, suggesting less maternal physiological disruption and a healthier prenatal environment for their child’s early development.

Future studies that aim to uncover the mechanisms underlying the intergenerational transmission of stress and protective factors will be a critical focus of inquiry with important implications for intervention development (Woods-Jaeger, Cho, Sexton, Slagel, & Goggin, 2018). Examination of extended family members, particularly grandparents, will be an important area of research. Research is also necessary to understand the influence of family strengths and protective factors in the presence of ACEs or trauma, as these may often co-occur within families (Narayan et al., 2018). As research in this area continues to emerge, it is imperative for clinicians and interventionists to consider the influence of maternal ACEs and family strengths on child health and take a two-generation approach when working with vulnerable families (Biglan, Van Ryzin, & Hawkins, 2017). The feasibility and acceptability of screening for parental ACEs has been demonstrated in primary care settings; therefore, routine screening for caregiver ACEs and associated sequelae, as well as referral to interventions that promote family strengths, will likely be a vital approach to preventing intergenerational transmission of trauma, maltreatment, and toxic stress (Gillespie & Folger, 2017).

Strengths and Limitations

This study was strengthened by the use of both subjective and objective indicators of exposure to chronic stress, and is one of the first studies to measure hair cortisol and salivary cytokines in ethnic minority children living in stressful environments. As there are currently no standardized pediatric reference ranges for the hair and salivary biomarkers explored in this study, the results of this study make a valuable contribution to biomarker science, especially regarding levels in ethnic minority children with whom biomarker research has been very limited (Gray et al., 2018; Riis et al., 2016). Our limited sample size prevented more complex modeling, such as including multiple measures of stress in a single-regression model; such models could provide additional insight and should be considered in future research with sufficient power.

It is notable that hair cortisol, a measure of chronic HPA axis functioning over time, did not yield any meaningful correlations in this sample. Hair cortisol is thought to offer an advantage over salivary cortisol, as salivary cortisol is sensitive to diurnal rhythms and the oral environment, and requires collection of multiple samples over time (Condon, 2018a). While other studies have detected relationships between child hair cortisol levels and other psychosocial exposures (Karlén et al., 2015), associations with past maternal history are unknown. As several children were unable to provide hair samples due to short hair length, it may be that our sample size was too small to detect significant associations amidst complex maternal–child relationships. Given the age range of our sample, it is also possible that stressors related to peers, school, or other aspects of the social environment may have a greater influence on school-age children than caregiver-related stressors. Future research involving larger samples of ethnic minority children living in stressful environments is necessary to better understand the role of hair cortisol as useful indicators of exposure to chronic stress in children (Gray et al., 2018).

Finally, this study is limited by the use of self-report measures to evaluate child health and behavioral history. Future research would be strengthened by the inclusion of more objective measures, such as medical record review for health history or teacher-reported child behavior, as well as the use of validated measures of family strengths, such as the Benevolent Childhood Experiences scale (Narayan et al., 2018). Future investigations accounting for the influence of maternal mental health symptoms are also necessary to better understand these complex relationships.

Conclusion

The results of this exploratory study suggest that maternal ACEs and PTSD symptoms may contribute to physiological disruptions and health outcomes associated with exposure to chronic stress in children. Our findings can be used to design future studies to better understand the complex interplay among biologic, epigenetic, and psychosocial factors that contribute to the intergenerational transmission of trauma and toxic stress, as well as protective factors that may help prevent the transmission of trauma in vulnerable families.

Acknowledgements:

This work was supported by the National Institute of Nursing Research of the National Institutes of Health (F31NR016385 and T32NR008346), the NAPNAP Foundation, the Connecticut Nurses Foundation, the Jonas Nurse Leaders Scholars Program, and the Alpha Nu chapter of Sigma Theta Tau International. We thank Andrea Miller for her assistance with recruitment and data collection and the Yale School of Nursing Biobehavioral Laboratory for providing necessary resources. We also thank the families who participated in this study for contributing their time and expertise.

Research reported in this publication was supported by National Institute of Nursing Research of the National Institutes of Health under award number F31NR016385. This work was also supported by the NAPNAP Foundation, the Connecticut Nurses Foundation, the Jonas Nurse Leaders Scholars Program, and the Alpha Nu chapter of Sigma Theta Tau International.

Footnotes

The authors have no conflicts of interest to report.

Ethical Conduct of Research: The Yale University Institutional Review Board approved all research reported in this manuscript.

The authors would like to thank Andrea Miller for her assistance with recruitment and data collection and the Yale School of Nursing Biobehavioral Laboratory for providing necessary resources.

The authors also thank the families who participated in this study for contributing their time and expertise.

The Yale University institutional review board approved all research reported in this manuscript.

Contributor Information

Eileen M. Condon, Yale School of Nursing, Orange, CT.

Margaret L. Holland, Yale School of Nursing, Orange, CT.

Arietta Slade, Yale Child Study Center, New Haven CT.

Nancy S. Redeker, Yale School of Nursing and Yale School of Medicine, New Haven, CT.

Linda C. Mayes, Yale Child Study Center, New Haven, CT.

Lois S. Sadler, Yale School of Nursing and Yale Child Study Center, New Haven, CT.

References

- Achenbach TM, & Ruffle TM (2000). The child behavior checklist and related forms for assessing behavioral/emotional problems and competencies. Pediatrics in Review, 21, 265–271. doi: 10.1542/pir.21-8-265 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benzies K, & Mychasiuk R (2009). Fostering family resiliency: A review of the key protective factors. Child & Family Social Work, 14, 103–114. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2206.2008.00586.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bernstein DP, Fink L, Handelsman L, Foote J, Lovejoy M, Wenzel K, . . . Ruggiero J (1994). Initial reliability and validity of a new retrospective measure of child abuse and neglect. American Journal of Psychiatry, 151, 1132–1136. doi: 10.1176/ajp.151.8.1132 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biglan A, Van Ryzin MJ, & Hawkins JD (2017). Evolving a more nurturing society to prevent adverse childhood experiences. Academic Pediatrics, 17, S150–S157. doi: 10.1016/j.acap.2017.04.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bird C & Michie C (2008). Measuring blood pressure in children. BMJ, 336, 1321. doi: 10.1136/bmj.a150 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bublitz MH, Parade S, & Stroud LR (2014). The effects of childhood sexual abuse on cortisol trajectories in pregnancy are moderated by current family functioning. Biological Psychology, 103, 152–157. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsycho.2014.08.014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Committee on Bioethics. (1995). Informed consent, parental permission, and assent in pediatric practice. Pediatrics, 95, 314–317. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Condon EM (2018a). Chronic stress in children and adolescents: A review of biomarkers for use in pediatric research. Biological Research for Nursing, 20, 473–496. doi: 1099800418779214 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Condon EM, Sadler LS, & Mayes LC (2018b). Toxic stress and protective factors in multi-ethnic school age children: A research protocol. Research in Nursing & Health, 41, 97–106. doi: 10.1002/nur.21851 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chung EK, Mathew L, Rothkopf AC, Elo IT, Coyne JC, & Culhane JF (2009). Parenting attitudes and infant spanking: The influence of childhood experiences. Pediatrics, 124, e278–e286. doi: 10.1542/peds.2008-3247 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chung EK, Nurmohamed L, Mathew L, Elo IT, Coyne JC, & Culhane JF (2010). Risky health behaviors among mothers-to-be: The impact of adverse childhood experiences. Academic Pediatrics, 10, 245–251. doi: 10.1016/j.acap.2010.04.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cook DG, Mendall MA, Whincup PH, Carey IM, Ballam L, Morris JE, . . . Strachan DP (2000). C-reactive protein concentration in children: Relationship to adiposity and other cardiovascular risk factors. Atherosclerosis, 149, 139–150. doi: 10.1016/S0021-9150(99)00312-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Falkner B, Daniels SR, Flynn JT, Gidding S, Green LA, Ingelfinger JR, ... Rocchini AP (2004). The fourth report on the diagnosis, evaluation, and treatment of high blood pressure in children and adolescents. Pediatrics, 114(2 III), 555–576. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Felitti VJ, Anda RF, Nordenberg D, Williamson DF, Spitz AM, Edwards V, . . . Marks JS (1998). Relationship of childhood abuse and household dysfunction to many of the leading causes of death in adults: The Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACE) Study. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 14, 245–258. doi: 10.1016/S0749-3797(98)00017-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Folger AT, Eismann EA, Stephenson NB, Shapiro RA, Macaluso M, Brownrigg ME, & Gillespie RJ (2018). Parental adverse childhood experiences and offspring development at 2 years of age. Pediatrics, 141, e20172826. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gillespie RJ, & Folger AT (2017). Feasibility of assessing parental ACEs in pediatric primary care: Implications for practice-based implementation. Journal of Child & Adolescent Trauma, 10, 249–256. doi: 10.1007/s40653-017-0138-z [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Glover V, O’Connor TG, & O’Donnell K (2010). Prenatal stress and the programming of the HPA axis. Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews, 35, 17–22. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2009.11.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gray NA, Dhana A, Van Der Vyver L, Van Wyk J, Khumalo NP, & Stein DJ (2018). Determinants of hair cortisol concentration in children: A systematic review. Psychoneuroendocrinology, 87, 204–214. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2017.10.022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haddad JJ, Saadé NE, & Safieh-Garabedian B (2002). Cytokines and neuro immune-endocrine interactions: A role for the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal revolving axis. Journal of Neuroimmunology, 133, 1–19. doi: 10.1016/S0165-5728(02)00357-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hillis SD, Anda RF, Dube SR, Felitti VJ, Marchbanks PA, Macaluso M, & Marks JS (2010). The protective effect of family strengths in childhood against adolescent pregnancy and its long-term psychosocial consequences. Permanente Journal, 14, 18–27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hughes K, Bellis MA, Hardcastle KA, Sethi D, Butchart A, Mikton C, . . . Dunne MP (2017). The effect of multiple adverse childhood experiences on health: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Public Health, 2, e356–e366. doi: 10.1016/S2468-2667(17)30118-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacobvitz D, Leon K, & Hazen N (2006). Does expectant mothers’ unresolved trauma predict frightened/frightening maternal behavior? Risk and protective factors. Development and Psychopathology, 18, 363–379. doi: 10.1017/S0954579406060196 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karlén J, Ludvigsson J, Hedmark M, Faresjö Å, Theodorsson E, & Faresjö T (2015). Early psychosocial exposures, hair cortisol levels, and disease risk. Pediatrics, 135, e1450–e1457. doi: 10.1542/peds.2014-2561 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuczmarski RJ (2002). 2000 CDC growth charts for the United States: Methods and development (Vital & Health Statistics: Series 11). Atlanta, GA: CDC Stacks. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lieberman AF, Padrón E, Van Horn P, & Harris WW (2005). Angels in the nursery: The intergenerational transmission of benevolent parental influences. Infant Mental Health Journal, 26, 504–520. doi: 10.1002/imhj.20071 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Madigan S, Wade M, Plamondon A, Maguire JL, & Jenkins JM (2017). Maternal adverse childhood experience and infant health: Biomedical and psychosocial risks as intermediary mechanisms. Journal of Pediatrics, 187, 282–289.e1. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2017.04.052 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDonnell CG, & Valentino K (2016). Intergenerational effects of childhood trauma: Evaluating pathways among maternal ACEs, perinatal depressive symptoms, and infant outcomes. Child Maltreatment, 21, 317–326. doi: 10.1177/1077559516659556 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyer J, Novak M, Hamel A, & Rosenberg K (2014). Extraction and analysis of cortisol from human and monkey hair. Journal of Visualized Experiments, 24, e508862. doi: 10.3791/50882 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muntner P, He J, Cutler JA, Wildman RP, & Whelton PK (2004). Trends in blood pressure among children and adolescents. JAMA, 291, 2107–2113. doi: 10.1001/jama.291.17.2107 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Narayan AJ, Rivera LM, Bernstein RE, Harris WW, & Lieberman AF (2018). Positive childhood experiences predict less psychopathology and stress in pregnant women with childhood adversity: A pilot study of the benevolent childhood experiences (BCEs) scale. Child Abuse & Neglect, 78, 19–30. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2017.09.022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ordway MR, Sadler LS, Dixon J, Close N, Mayes L, & Slade A (2014). Lasting effects of an interdisciplinary home visiting program on child behavior: Preliminary follow-up results of a randomized trial. Journal of Pediatric Nursing, 29, 3–13. doi: 10.1016/j.pedn.2013.04.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palmer FB, Anand KJS, Graff JC, Murphy LE, Qu Y, Völgyi E, . . . Tylavsky FA (2013). Early adversity, socioemotional development, and stress in urban 1-year-old children. Journal of Pediatrics, 163, 1733–1739. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2013.08.030 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pereira J, Vickers K, Atkinson L, Gonzalez A, Wekerle C, & Levitan R (2012). Parenting stress mediates between maternal maltreatment history and maternal sensitivity in a community sample. Child Abuse and Neglect, 36, 433–437. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2012.01.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Racine NM, Madigan SL, Plamondon AR, McDonald SW, & Tough SC (2018). Differential associations of adverse childhood experience on maternal health. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 54, 368–375. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2017.10.028 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riis JL, Granger DA, Minkovitz CS, Bandeen-Roche K, DiPietro JA, & Johnson SB (2016). Maternal distress and child neuroendocrine and immune regulation. Social Science and Medicine, 151, 206–214. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2015.12.043 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sacks V, & Murphey D (2018). The prevalence of adverse childhood experiences, nationally, by state, and by race or ethnicity. https://www.childtrends.org/publications/prevalence-adverse-childhood-experiences-nationally-state-race-ethnicity

- Sadler LS, Slade A, Close N, Webb DL, Simpson T, Fennie K, & Mayes LC (2013). Minding the baby: Enhancing reflectiveness to improve early health and relationship outcomes in an interdisciplinary home-visiting program. Infant Mental Health Journal, 34, 391–405. doi: 10.1002/imhj.21406 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shonkoff JP, Garner AS, Siegel BS, Dobbins MI, Earls MF, McGuinn L, . . . Wood DL (2012). The lifelong effects of early childhood adversity and toxic stress. Pediatrics, 129, e232–e246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith MV, Gotman N, & Yonkers KA (2016). Early childhood adversity and pregnancy outcomes. Maternal and Child Health Journal, 20, 790–798. doi: 10.1007/s10995-015-1909-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun J, Patel F, Rose-Jacobs R, Frank DA, Black MM, & Chilton M (2017). Mothers’ adverse childhood experiences and their young children’s development. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 53, 882–891. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2017.07.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weathers FW, Litz BT, Herman DS, Huska JA, & Keane TM (1993, October). The PTSD checklist (PCL): Reliability, validity, and diagnostic utility In Annual Convention of the International Society for Traumatic Stress Studies. San Antonio, TX: (Vol. 462). [Google Scholar]

- Woods-Jaeger BA, Cho B, Sexton CC, Slagel L, & Goggin K (2018). Promoting resilience: Breaking the intergenerational cycle of adverse childhood experiences. Health Education & Behavior, 45, 772–780. doi: 10.1177/1090198117752785 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]