Abstract

Objective.

To evaluate the safety and efficacy of low-frequency, inhibitory, deep rTMS with a novel H coil specifically designed to stimulate the insula.

Methods.

In a randomized, crossover order, sixteen healthy volunteers underwent 2 sessions (sham; active) of 1 Hz repetitive TMS at an intensity of 120% of individual motor threshold, over the right anterior insular cortex localized using a neuro-navigation system. Before, immediately after, and 1h after rTMS, subjects performed 2 tasks that have previously been shown in fMRI experiments to activate insular cortex: a blink suppression task and a forced-choice risk-taking task.

Results.

No drop-outs or adverse events occurred. Active deep rTMS did not result in decreased urge to blink compared to sham. Similarly, no significant time x condition interaction on risk-taking behavior was found.

Conclusions.

Low-frequency deep rTMS using a novel H8 coil was shown to be safe but did not affect any of the behavioral markers used to investigate modulation of insula activity.

Our findings highlight the challenges of modulating the activity of deep brain regions with TMS. Further studies are necessary to identify effective stimulation parameters for deep targets, and to characterize the effects of deep TMS on overlying cortical regions.

Keywords: Insula, Deep transcranial magnetic stimulation, H-coil, Urge, Risk

1. Introduction

In recent years, the introduction of Hesed coils (H-coils), a new family of coils for transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS), has offered the opportunity of non-invasively modulate activity in brain targets that previously were accessible only by neurosurgical techniques.

Compared to conventional figure-of-eight coils, H-coils can achieve broader and deeper stimulation of the brain, thereby affecting both cortical and subcortical regions (1, 2). As indicated by model electrical fields distribution maps, two different H-coils (H1 and H2) have been shown to enable activation of lateral and medial frontal regions at depths of up to 4.5 to 5.5 cm, with a stimulator output at 120% of the hand motor threshold (3).

Several different H-coils have been evaluated for the treatment of a variety of psychiatric and neurological disorders, including major depression (4, 5), addiction (6, 7), and blepharospasm (8), with encouraging results. This has prompted the development of novel H-coils designed to target specific brain regions, and diseases, on the basis of precise neurobiological hypotheses. Their use, however, requires assessment of their safety, efficacy and optimal stimulation parameters.

In this preliminary, randomized, cross-over study, we evaluated the novel H8 coil, which allows for uni- or bilateral stimulation of the insula. We investigated whether low frequency, inhibitory, repetitive TMS was able to affect activity of the anterior insula (aINS), by examining behavioral responses during tasks known to activate this region. Specifically, we focused on a ‘blink task’, which evaluates urge processing, and on a ‘forced-choice risk task’, which assesses risk-taking behavior. Our primary hypothesis was that low-frequency deep TMS would inhibit insula activity during urge processing, thus attenuating the urge sensation. Further, we aimed at evaluating whether temporary disruption of insula activity would also lead to risk-aversion.

The aINS has been shown to play a critical role in the buildup and suppression of bodily urges and behaviors [for a review see (9)], and in different aspects of decision-making involving risk (10–13). Furthermore, dysregulations in aINS activity is found in subjects with various neuropsychiatric diseases, including Tourette syndrome (14–16), OCD (17, 18), and addictions (19–21), which are characterized by alterations in some of the aforementioned processes. Thus, modulating insula activity using deep TMS may have important therapeutic implications.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Subjects

Sixteen healthy volunteers (9 females, 20–53 aged, mean age ± SD: 37.7 ± 8) participated in this study. Exclusion criteria included left-handedness, as assessed by the Edinburgh Inventory (22); contraindications to TMS (23); use of any medication on a regular basis; and a positive history of psychiatric or neurologic diseases. To exclude structural brain lesions and identify anatomical target for stimulation, a T1-weighted MRI image was obtained for all participants using a 3T MRI scanner (General Electric; Fairfield, CT).

This study was approved by the Neuroscience Institutional Review Board of the National Institutes of Health, USA. All participants gave written informed consent prior to the experiment.

2.2. Apparatus and Procedures

TMS was delivered via a super rapid stimulator (Magstim Inc, Wales, UK), connected to the H8 coil (Hesed coil, Brainsway Inc, Delaware, USA). This device contains two symmetric wings, designed to stimulate one or both hemispheres. Differently from a double-cone coil, the windings of the H8 coil are not fixed at a specific angle but can be adjusted around the head (Fig. 1).

Figure 1.

The H8 coil device contains two symmetric components designed to stimulate one or both hemispheres. Lateral (a) and frontal (b) view of H8 coil placement on subject’ head. Figure (c) shows the coil elements contained in the H8 device.

We choose to target the right aINS, since neuroimaging studies have shown preferential involvement of the right hemisphere in the tasks used in our study (11, 24–26). By targeting the aINS and placing the H-coil as tangential as possible to the scalp surface, we aimed to stimulate along the full frontal operculum (Fig. 2). To provide a precise and individual-tailored identification of the target area, we used structural MRI data previously acquired for each patient. The aINS was identified and marked on the subject’ MRI, and the individual MNI coordinates were used to identify the stimulation target on the subject’ skull, using a neuronavigation software (Brainsight Navigation System - Rogue Research, Montreal, QC, Canada), which matches skull landmarks with MRI information. The location of the aINS was drawn on a fabric cap wore by the participants during the experimental sessions and was used to center the H8 coil. To ensure that the cap placement was identical between sessions, scalp and facial landmarks (i.e., inion, nasion, ear to ear distance) were utilized.

Figure 2.

Target area (right anterior insula) and its relationship with coil placement over the scalp. The target area, located at approximately 4 cm from the scalp surface, was mapped using an MRI-guided navigation system for TMS. Target location was marked on a cap wore by the participants during the experimental session. The center of the coil, where the magnetic field is at the maximum, was also marked on the inner surface of the right wing of the H8 coil, which was placed on the target.

The stimulation intensity used in our study was set at 120% of the hand resting motor threshold (rMT) on the basis of a previous efficacious deep TMS study targeting the prefrontal and insular cortex (7). The motor threshold was defined as the lowest stimulus intensity able to elicit 5 motor evoked potentials (MEPs) of at least 50 µV amplitude in a series of 10 stimuli delivered over the MC at intervals longer than 5 s (27). MEPs were recorded from the contralateral FDI at rest with Ag\Cl surface electrodes fixed on the skin with a belly tendon montage.

In a counterbalanced order, participants received a session of active or sham rTMS for 10 minutes at 1Hz frequency (600 continuous pulses), on separate days. The interval between sessions was at least 72 hours. Both active and sham stimulation were delivered using the same coil placement. During the sham stimulation, the H8 coil produced a sound artefact similar to the active TMS condition, although did not induce scalp sensations or muscle twitches. To preserve subjects’ blindness to the stimulation condition, we explained to the participants that the somatosensory effects of TMS depended on the particular stimulation intensity used during each experimental session.

The selection of the operation mode (1Hz, sham) was done using a magnetic treatment card individually assigned to each subject and pre-programmed to activate the respective condition when inserted into the device by a staff member not involved in data collection and analysis. Study personnel did not know which mode was activated by any particular card.

During each experimental session, eye blink rate (BR), urge to blink and risky decision-making tasks were measured at baseline (t0), immediately after (t1), and 60 minutes after (t2) receiving rTMS, with task order counterbalanced across participants. The entire session lasted approximately 120 minutes. At the end of each session participants were interviewed for TMS-related adverse events.

2.3. Tasks

Eye blink suppression task (16). In this task participants fixated on a computer screen and were instructed to try inhibiting any eye blinking over a 5 minute-period. When a blink occurred, subjects were told to return immediately to the mode of blink suppression. In order to avoid any straining of eye position during the experiment, the position of the computer screen was adjusted for each subject such that it was located in the center of their visual field with eyes in a comfortable, midline position (approximately when the bottom of the iris was at the level of the resting bottom eye lid).

The BR during the 5 minutes-period was detected and recorded using electrooculography (EOG) [for details see (16)]. Eye blinks were also captured by a video camera to ensure that EOG waveforms accurately corresponded to actual blinks. During the task, none of the subjects wore corneal lenses; eyeglasses were used by the habitual wearers. Also, same room luminance conditions and temperature were kept during both TMS experimental sessions.

While trying to inhibit eye blinking, subjects were simultaneously asked to rate their urge to blink in real time, using an electronic numeric visual analog scale, similarly to previously described methods (28). In brief, participants were instructed to indicate their current urge intensity level on a 100-point visual analog scale (0 = no urge at all and 100 = the strongest urge) displayed on the computer screen, by continuously clicking on a mouse. Each time a blink occurred, the urge rating was set back to zero, and subjects returned to suppress blinking and rate urge levels, as the intensity built up. In this way, patients were able to continuously track changes in urge intensity without having to compare them to the previous urge intensity across a time gap.

Forced-choice risk task (29). The task comprised 40 trails and lasted approximately 8 minutes. Subjects were asked to choose between a safe and a risky option. The safe option was guaranteed always to win $0.25, whereas when choosing the risky option, participants could win $1.00 or $5.00, but they also risked losing $1.00 or $5.00. Fifty percent of risky choices resulted in wins and 50% resulted in losses, but the participants had no knowledge of these probabilities. Wins and losses were pseudorandomized. Participants were read an instruction script describing the task, and performed approximately 5 practice trials, prior to each experimental session.

2.4. Statistical Analysis.

For the blink suppression task, BR was considered as the number of blinks occurring during the 5 min-period, with the exception of the first 5 seconds to allow for adaptation to the task. Blink occurrence was assessed by a single rater that visually examined the EOG recordings. Eye blink was defined as a sharp high amplitude wave ≥ 100 μV, peaking from the baseline in no more than 100 ms, and ≤ 400 ms in duration (20). In addition, the number of eye blinks was also counted in close-up video pictures of the face of each subject, recorded during each experimental session. The number yielded by video counting matched with those yielded by the EOG analysis.

To evaluate the urge to blink, we calculated the area under the curve (AUC) of the individual urge intensity ratings reported during the interval between the end of an eye blink, when urge intensity rating corresponded to 0, and the consecutive eye blink, corresponding with the highest rating reported immediately before blinking.

Given that baseline scores of BR and AUC significantly differed between the active and sham stimulation condition, we used the relative change from baseline as our outcome measures. The relative change was calculated as 100* (Ti-T0)/T0, where Ti was BR or AUC measure at timepoint Ti (i=1, 2) and T0 was the measure at baseline. Statistical analyses were performed using SAS (version 9.3; SAS Institute, Cary, NC). The mixed model procedure (PROC MIXED) was used to test the effects of condition (active vs. sham), time point, and their interaction on changes in BR and AUC of the urge to blink, with condition and time as the within-subject factor, and subject as a random effect. Test-retest reliability for BR and AUC was assessed by calculating Pearson correlation coefficients between baseline values for the sham and stimulation conditions.

With regard to the risk task, the relative change from baseline in the number of risky choices made during the task were similarly analyzed using repeated measures analysis of variance (ANOVA) in the SAS PROC MIXED modeling, with condition and time point as the within-subject factor.

For all analyses, the factor of session order (i.e. group a or B) was included as a covariate.

3. Results

None of the subjects experienced any severe adverse effects during or after the study, but all subjects reported mild discomfort during the active TMS sessions. Furthermore, two subjects reported mild headache immediately after the end of active rTMS which resolved spontaneously shortly after its onset. The mean RMT at the motor cortex assessed in the first experimental session was 51 ± 8% of the maximum stimulator output (MSO), and 53 ± 8% MSO in the second session.

Blink task.

Mean BR and AUC (±SD) assessed at baseline (t0), immediately after (t1), and 60 minutes later receiving TMS (t2) during the active and sham experimental condition, are reported in Table 2. Test-retest reliability for BR was high (r =0.85), while the baseline values for AUC were moderately correlated between the sham and stimulation conditions, indicating modest test-retest reliability for this measure (r =0.54).

Since baseline scores of BR and AUC significantly differed between the active and sham stimulation condition, relative change from baseline were used as outcome measures. We first examined the effects of active and sham stimulation on BR. ANOVA showed a significant effect of condition [F(1, 23.2)= 4.55; p= 0.04], such that, compared to baseline, BR decreased following active stimulation, while it increased after subjects received sham stimulation [Fig. 3a]. No significant effect of time on BR was observed, indicating that BR scores did not significantly change over time following stimulation in both conditions [F(1, 10.6)= 0.01; p= 0.92], and no significant interaction between condition and time was found [F(1, 10.2)=0.01; p=0.99).

Figure 3.

Relative changes from baseline for eye blinking rate (BR) and urge to blink (AUC) following sham and active rTMS.

With regard to the AUC of urge to blink, ANOVA showed a significant effect of condition [F(1, 19.7)=5.36; p=0.03], and a significant effect of time on AUC [F(1, 16.9)=5.86; p=0.03], indicating that in the active condition post-TMS AUC values were higher than in the sham condition. Also, on average there was an increase in AUC scores from t1 to t2 [Fig. 3b], such that the urge to blink increased over time in both conditions. No significant condition by time interaction was found [F(1, 13.7)=1.84; p=0.20].

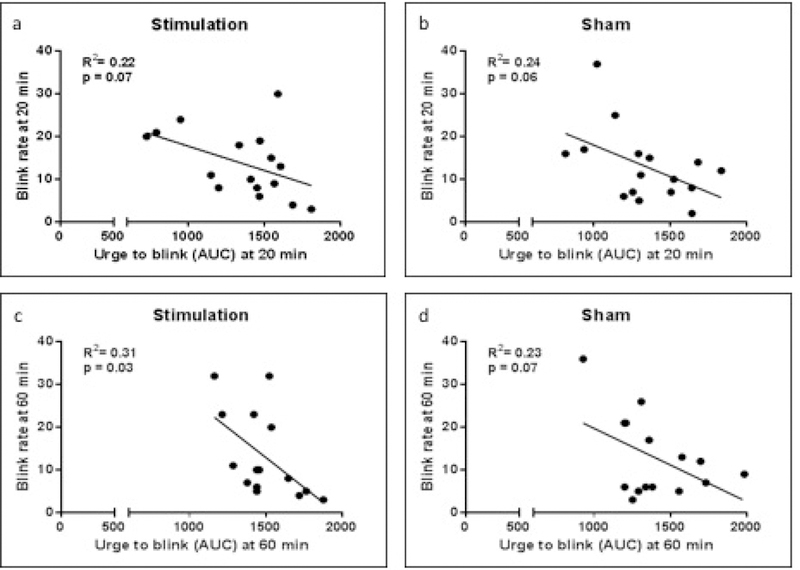

Furthermore, to explore whether the number of eye blinks were related to the reported urge to blink, we examined the correlation of the AUC to BR scores at each time point, following both active and sham TMS (Fig. 4). Overall, an inverse correlation between blink rate and urge to blink at a trend level of significance was observed at each time point and under both active (T1: r = .22, p = .07; T2: r = .31, p = .003), and sham conditions (T1: r = .24, p = .06; T2: r = .31, p = .07), supporting the validity of our outcome measures.

Figure 4.

Correlations of the AUC to BR scores at each time point, following both active and sham TMS.

Risk task.

There was a trend for a main effect of TMS condition on the relative change from baseline in the number of risky choices [F(1, 23.8)=3.06; p=0.09]. ANOVA showed no significant condition by time interaction on the number of risky choices in response to active vs. sham stimulation [F(1,13.3) = 0.52, p = 0.48]. There was no main effect of time [F(1, 23.7) = 1.18, p = 0.29].

4. Discussion

In the present study, deep rTMS applied over the right aINS via a novel H8 coil was shown to be safe. Following a single session of active, low-frequency rTMS subjects reported greater urge to blink compared to baseline, whereas post-TMS blink rate was decreased. Conversely, following sham stimulation there was an increase in blink rate, and only a modest effect on the urge to blink as compared to baseline. We also observed an inverse correlation between urge intensity and blink occurrence, such that when subjects showed increased blinking, their urge to blink subsided. Finally, we did not find any condition×time interaction or main effect of TMS condition in the number of risky choices made by study participants during the forced-choice risk task.

Together, these findings do not lend support to our primary hypothesis that low-frequency deep rTMS would inhibit insula activity during urge processing, thus attenuating the urge sensation. Our hypothesis was based on several studies showing that increased activity in aINS was associated with the buildup of urge sensations during suppression of natural bodily functions (14, 16), as well as with the ‘urge‐for‐action’ associated with natural behaviors (9). Furthermore, increased aINS activity is observed in clinical disorders characterized by abnormal urge-for-action (e.g., Tourette syndrome, obsessive-compulsive disorder, addiction) (17, 19, 21, 26). Also relevant is the observation reported by lesion studies indicating that patients with selective insular damage exhibited a dramatic decrease in urge to smoke, which leads to disruption of their smoking addiction (30–33).

In the current study, we used low-frequency TMS to achieve a non-invasive and temporary disruption of insula activity, since such frequency is known to consistently inhibit motor cortical excitability (34), with the aim to replicate the findings from lesion studies and to explore whether urge processing could be modulated. Our results, however, indicated that following active stimulation the urge to blink increased, although the decrease in blink rate may suggest that active stimulation increased tolerance to the urge, thus allowing to delay the action associated with urge relief.

This interpretation, although interesting especially for the potential clinical implications, appears to be challenged by several considerations. In particular, we observed that baseline values for both blink rate and urge to blink were significantly different among the two experimental conditions, although there were no differences in terms of room conditions or instructions given to participants to perform the blink task. Furthermore, the order of TMS conditions was randomized and counter-balanced among subjects. Nevertheless, we found that in the active TMS condition, BR mean at baseline was greater compared to the sham TMS condition, while the opposite was observed for the mean AUC of the urge to blink. Mean values at baseline were not driven by outliers; therefore, we included all subjects in our analysis, which was performed using relative change to account for the different baseline values. However, the lack of significant time×condition interaction suggest that active stimulation did not affect any of our outcome measures. This also includes results from the forced-choice risk task, which showed that risk-taking behavior was not affected by active TMS. Selection of risky options has been associated with increased activity in aINS (11, 13), while insula inactivation or damage led to risk-aversion in animals and humans, respectively (35, 36).

Since we believe that the testing paradigm used in our study reliably involved aINS activation, the lack of target modulation observed in our study could be related to the stimulation parameters used. In particular, we chose to set the intensity of stimulation at 120% of the rMT based on previous studies evaluating the effects of TMS on deep targets, including the insula (25, 37). At 120% of the rMT the H8 coil is expected to produce 100 V/m to a depth of 3.5 cm from the scalp (personal communication, Abraham Zangen and Yiftach Roth, October 2016). Affecting neural activity 3.5 cm from the scalp is deep enough to include the entire frontal operculum, but at the depth of our target (approximately 4 cm from the scalp), the intensity of stimulation would be reduced (between 66% and 81% of the maximal field induced at the surface of the skull, as measured for H1 and H2 coils (38)). On the other hand, a study evaluating the field characteristics of coils for deep TMS reported that to reach depth of 4 cm, the superficial cortical strength would be 145% of motor threshold (39), which exceeds the range of intensities covered in the current rTMS safety guidelines (≤ 130% motor threshold) (23).

With regard to the direction of the stimulation (excitatory vs. inhibitory), we chose to deliver low-frequency rTMS on the basis of the aforementioned lesion studies. Nevertheless, a recent study investigating the effects of bilateral deep rTMS of the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (DLPFC) and the insula on smoking addiction, indicated that high- but not low-frequency deep TMS reduced cigarette consumption (7). However, several factors, including the use of a different H coil, the choice to stimulating bilaterally both DLFC and insula, the number of TMS sessions, a study sample of patients and the exposure to smoking-related cues prior to stimulation, critically affect stimulation outcomes. Furthermore, the authors reported that deep TMS reduced the number of cigarettes smoked, but had no effect on urge to smoke, a process mediated by the aINS.

The lack of neuroimaging markers in both studies leaves open the question whether deep TMS may reach the insula, or whether the effects observed are related to the stimulation of overlying cortical regions. In this regard, a recent study showed that 1 Hz deep TMS at 100% of rMT over the secondary somatosensory cortex reduced somatosensory BOLD response in this cortical area but did not affect the insula (40).

In addition to the lack of neuroimaging markers, other limitations of our study are represented by the small sample size and by the characteristics of the sham condition provided by the H8 coil. Although in the sham operation mode, the H8 coil produced a sound artefact similar to the active TMS condition, it did not induce the same somatic sensation of scalp muscle contractions. Following active stimulation, the levels of discomfort reported by subjects were greater compared to sham TMS, thus suggesting that blinding conditions may not be optimal. We should also notice that the time interval ( ≥ 72 hours) between stimulation sessions might not have been enough to completely wash out potential carryover effects, although active and sham stimulations were delivered in counter balanced order and no effect of session order was observed. Finally, we found a modest test-retest reliability for AUC of the urge to blink. This may be due to the occurrence of involuntary blinks during the suppression task, which might lead to a transient decrease in the urge to blink. The number and timing of these blinks vary considerably among subjects and the degree to which such a blink would reduce the level of urge for an individual subject may be difficult to assess (16).

In summary, although the aforementioned limitations emphasize the need for caution, our findings indicate that low-frequency deep TMS with the novel H8 coil did not affect the behavioral markers of insula activity used in the current study. The use of low-frequency stimulation may have led to a sub-threshold stimulation of the aINS. Thus, further studies will be necessary to identify whether different stimulation parameters should be used in order to achieve stimulation of deep targets, without increasing the risk for adverse effects. Furthermore, it will be critical to evaluate the possible distinct effects of these stimulation parameters on the overlying cortical regions, also affected by the broad field produced by deep TMS coils, given that their stimulation can contribute to modulate activity of deeper, interconnected regions.

Figure 5.

Relative changes from baseline for risk choices following sham and active rTMS

Table 1.

Mean BR and AUC (±SD) assessed at baseline (t0), immediately after and 60 minutes later the TMS sessions, during the active and sham experimental condition.

| Mean | SD | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| AUC | real | t0 | 1214.39 | 318.86 |

| t1 | 1360.31 | 316.32 | ||

| t2 | 1452.67 | 239.4 | ||

| sham | t0 | 1444.08 | 304.68 | |

| t1 | 1341.99 | 285.05 | ||

| t2 | 1401.57 | 265.54 | ||

| BR | real | t0 | 16.25 | 7.32 |

| t1 | 13.69 | 7.7 | ||

| t2 | 13.27 | 10.04 | ||

| sham | t0 | 10.75 | 8.41 | |

| t1 | 13 | 8.58 | ||

| t2 | 12.87 | 9.52 |

Acknowledgments

Funding

This work was supported by the NINDS Intramural Program, National Institutes of Health

Dr. Hallett serves as Chair of the Medical Advisory Board for and may receive honoraria and funding for travel from the Neurotoxin Institute. He may accrue revenue on US Patent #6,780,413: Immunotoxin (MAB-Ricin) for the treatment of focal movement disorders and US Patent #7,407,478: Coil for Magnetic Stimulation and methods for using the same (H-coil); in relation to the latter, he has received license fee payments from the NIH (from Brainsway) for licensing of this patent. He has received royalties and/or honoraria from publishing from Cambridge University Press, Oxford University Press, and Elsevier. Research funds have been granted by UniQure for a clinical trial of AAV2-GDNF for Parkinson Disease, Merz for treatment studies of focal hand dystonia, and Allergan for studies of methods to inject botulinum toxins.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest

Primavera A Spagnolo, Han Wang, Prachaya Srivanitchapoom, Melanie Schwandt, Markus Heilig have no conflict of interest to report.

References

- 1.Zangen A, Roth Y, Voller B, Hallett M (2005): Transcranial magnetic stimulation of deep brain regions: evidence for efficacy of the H-coil. Clin Neurophysiol 116:775–779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Roth Y, Zangen A, Hallett M (2002): A coil design for transcranial magnetic stimulation of deep brain regions. J Clin Neurophysiol 19:361–370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Roth Y, Amir A, Levkovitz Y, Zangen A (2007): Three-dimensional distribution of the electric field induced in the brain by transcranial magnetic stimulation using figure-8 and deep H-coils. J Clin Neurophysiol 24:31–38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Harel EV, Rabany L, Deutsch L, Bloch Y, Zangen A, Levkovitz Y (2014): H-coil repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation for treatment resistant major depressive disorder: An 18-week continuation safety and feasibility study. World J Biol Psychiatry 15:298–306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Levkovitz Y, Harel EV, Roth Y, Braw Y, Most D, Katz LN, et al. (2009): Deep transcranial magnetic stimulation over the prefrontal cortex: evaluation of antidepressant and cognitive effects in depressive patients. Brain Stimul 2:188–200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ceccanti M, Inghilleri M, Attilia ML, Raccah R, Fiore M, Zangen A, et al. (2015): Deep TMS on alcoholics: effects on cortisolemia and dopamine pathway modulation. A pilot study. Can J Physiol Pharmacol 93:283–290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dinur-Klein L, Dannon P, Hadar A, Rosenberg O, Roth Y, Kotler M, et al. (2014): Smoking cessation induced by deep repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation of the prefrontal and insular cortices: a prospective, randomized controlled trial. Biol Psychiatry 76:742–749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kranz G, Shamim EA, Lin PT, Kranz GS, Hallett M (2010): Transcranial magnetic brain stimulation modulates blepharospasm: a randomized controlled study. Neurology 75:1465–1471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jackson SR, Parkinson A, Kim SY, Schuermann M, Eickhoff SB (2011): On the functional anatomy of the urge-for-action. Cogn Neurosci 2:227–243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pletzer B, MO T (2016): Neuroimaging supports behavioral personality assessment: Overlapping activations during reflective and impulsive risk taking. Biol Psychol 119:46–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Paulus MP, Rogalsky C, Simmons A, Feinstein JS, Stein MB (2003): Increased activation in the right insula during risk-taking decision making is related to harm avoidance and neuroticism. Neuroimage 19:1439–1448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ernst M, Bolla K, Mouratidis M, Contoreggi C, Matochik JA, Kurian V, et al. (2002): Decision-making in a risk-taking task: a PET study. Neuropsychopharmacology 26:682–691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bossaerts P (2010): Risk and risk prediction error signals in anterior insula. Brain Struct Funct 214:645–653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lerner A, Bagic A, Boudreau EA, Hanakawa T, Pagan F, Mari Z, et al. (2007): Neuroimaging of neuronal circuits involved in tic generation in patients with Tourette syndrome. Neurology 68:1979–1987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Draper A, Jackson GM, Morgan PS, Jackson SR (2016): Premonitory urges are associated with decreased grey matter thickness within the insula and sensorimotor cortex in young people with Tourette syndrome. J Neuropsychol 10:143–153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Berman BD, Horovitz SG, Morel B, Hallett M (2012): Neural correlates of blink suppression and the buildup of a natural bodily urge. Neuroimage 59:1441–1450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zhu Y, Fan Q, Zhang H, Qiu J, Tan L, Xiao Z, et al. (2016): Altered intrinsic insular activity predicts symptom severity in unmedicated obsessive-compulsive disorder patients: a resting state functional magnetic resonance imaging study. BMC Psychiatry 16:104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Luigjes J, Figee M, Tobler PN, van den Brink W, de Kwaasteniet B, van Wingen G, et al. (2016): Doubt in the Insula: Risk Processing in Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder. Front Hum Neurosci 10:283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Garavan H (2010): Insula and drug cravings. Brain Struct Funct 214:593–601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Barbato G, De Padova V, Paolillo AR, Arpaia L, Russo E, Ficca G (2007): Increased spontaneous eye blink rate following prolonged wakefulness. Physiol Behav 90:151–154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Droutman V, Read SJ, Bechara A (2015): Revisiting the role of the insula in addiction. Trends Cogn Sci 19:414–420. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Oldfield RC (1971): The assessment and analysis of handedness: the Edinburgh inventory. Neuropsychologia 9:97–113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rossi S, Hallett M, Rossini PM, Pascual-Leone A, Safety of TMSCG (2009): Safety, ethical considerations, and application guidelines for the use of transcranial magnetic stimulation in clinical practice and research. Clin Neurophysiol 120:2008–2039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Garavan H, Ross TJ, Stein EA (1999): Right hemispheric dominance of inhibitory control: an event-related functional MRI study. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 96:8301–8306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chambers CD, Bellgrove MA, Stokes MG, Henderson TR, Garavan H, Robertson IH, et al. (2006): Executive “brake failure” following deactivation of human frontal lobe. J Cogn Neurosci 18:444–455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tinaz S, Malone P, Hallett M, Horovitz SG (2015): Role of the right dorsal anterior insula in the urge to tic in Tourette syndrome. Mov Disord 30:1190–1197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rothwell JC (1997): Techniques and mechanisms of action of transcranial stimulation of the human motor cortex. J Neurosci Methods 74:113–122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Brandt VC, Beck C, Sajin V, Baaske MK, Baumer T, Beste C, et al. (2016): Temporal relationship between premonitory urges and tics in Gilles de la Tourette syndrome. Cortex 77:24–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gilman JM, Smith AR, Ramchandani VA, Momenan R, Hommer DW (2012): The effect of intravenous alcohol on the neural correlates of risky decision making in healthy social drinkers. Addict Biol 17:465–478. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Abdolahi A, Williams GC, Benesch CG, Wang HZ, Spitzer EM, Scott BE, et al. (2015): Damage to the insula leads to decreased nicotine withdrawal during abstinence. Addiction 110:1994–2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Abdolahi A, Williams GC, Benesch CG, Wang HZ, Spitzer EM, Scott BE, et al. (2015): Smoking cessation behaviors three months following acute insular damage from stroke. Addict Behav 51:24–30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Abdolahi A, Williams GC, Benesch CG, Wang HZ, Spitzer EM, Scott BE, et al. (2017): Immediate and Sustained Decrease in Smoking Urges After Acute Insular Cortex Damage. Nicotine Tob Res 19:756–762. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Naqvi NH, Rudrauf D, Damasio H, Bechara A (2007): Damage to the insula disrupts addiction to cigarette smoking. Science 315:531–534. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Chen R, Classen J, Gerloff C, Celnik P, Wassermann EM, Hallett M, et al. (1997): Depression of motor cortex excitability by low-frequency transcranial magnetic stimulation. Neurology 48:1398–1403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ishii H, Ohara S, Tobler PN, Tsutsui K, Iijima T (2012): Inactivating anterior insular cortex reduces risk taking. J Neurosci 32:16031–16039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Weller JA, Levin IP, Shiv B, Bechara A (2009): The effects of insula damage on decision-making for risky gains and losses. Soc Neurosci 4:347–358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ciampi de Andrade D, Galhardoni R, Pinto LF, Lancelotti R, Rosi J Jr., Marcolin MA, et al. (2012): Into the island: a new technique of non-invasive cortical stimulation of the insula. Neurophysiol Clin 42:363–368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Deng ZD, Lisanby SH, Peterchev AV (2013): Electric field depth-focality tradeoff in transcranial magnetic stimulation: simulation comparison of 50 coil designs. Brain Stimul 6:1–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Deng ZD, Lisanby SH, Peterchev AV (2014): Coil design considerations for deep transcranial magnetic stimulation. Clin Neurophysiol 125:1202–1212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Case LK, Laubacher CM, Richards EA, Spagnolo PA, Olausson H, Bushnell MC (2017): Inhibitory rTMS of secondary somatosensory cortex reduces intensity but not pleasantness of gentle touch. Neurosci Lett 653:84–91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]