Summary

Context

Lactation insufficiency has many aetiologies including complete or relative prolactin deficiency. Exogenous prolactin may increase breast milk volume in this subset. We hypothesized that recombinant human prolactin (r-hPRL) would increase milk volume in mothers with prolactin deficiency and mothers of preterm infants with lactation insufficiency.

Design

Study 1: R-hPRL was administered in an open-label trial to mothers with prolactin deficiency. Study 2: R-hPRL was administered in a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial to mothers with lactation insufficiency that developed while pumping breast milk for their preterm infants.

Patients

Study 1: Mothers with prolactin deficiency (n = 5). Study 2: Mothers of premature infants exclusively pumping breast milk (n = 11).

Design

Study 1: R-hPRL (60 μg/kg) was administered subcutaneously every 12 h for 28 days. Study 2: Mothers of preterm infants were randomized to receive r-hPRL (60 μg/kg), placebo or r-hPRL alternating with placebo every 12 h for 7 days.

Measurements

Change in milk volume.

Results

Study 1: Peak prolactin (27·9 ± 17·3 to 194·6 ± 19·5 μg/l; P < 0·003) and milk volume (3·4 ± 1·6 to 66·1 ± 8·3 ml/day; P < 0·001) increased with r-hPRL administration. Study 2: Peak prolactin increased in mothers treated with r-hPRL every 12 h (n = 3; 79·3 ± 55·4 to 271·3 ± 36·7 μg/l; P < 0·05) and daily (101·4 ± 61·5 vs 178·9 ± 45·9 μg/l; P < 0·04), but milk volume increased only in the group treated with r-hPRL every 12 h (53·5 ± 48·5 to 235·0 ± 135·7 ml/day; P < 0·02).

Conclusion

Twice daily r-hPRL increases milk volume in mothers with prolactin deficiency and in preterm mothers with lactation insufficiency.

Background

Breastfeeding has many important health implications for mothers and infants. In infants, breastfeeding reduces the risk of infectious, immune and atopic diseases and mortality.1 Mothers benefit by protection against breast and ovarian cancer, hip fractures, type 2 diabetes and cardiovascular disease.2,3 Thus, breastfeeding is recommended for all able mothers and infants.1

There can be obstacles to breastfeeding even in the most motivated women. The prevalence of lactation insufficiency may be as high as 15% in new mothers, and the causes are broad.4,5 Rarely, mothers are identified with very low prolactin levels because of genetic deficiency, postpartum pituitary necrosis or idiopathic causes and never produce milk.6,7 Lactation insufficiency is also common among mothers of hospitalized premature neonates. Because these infants are often too small or sick to suckle, mothers express milk with breast pumps for their newborns. While successful lactation can occur in this setting, milk production often decreases after 4–6 weeks of exclusive pumping.8

Prolactin is critical for lactation, but a direct relationship between prolactin and milk volume has not been firmly established. 9 Prolactin levels rise during pregnancy to approximately 200 μg/l at term.10,11 Baseline levels remain elevated in postpartum nursing women, and each suckling episode results in a prolactin rise. Suckling-induced mean and peak prolactin levels decrease with duration of lactation despite continued milk production.12 Yet, milk production fails in the absence of prolactin,6 and bromocriptine abolishes lactation at all stages, even after prolonged lactation when baseline prolactin levels have reached the normal range.13 The majority of studies in women with inadequate lactation demonstrate a correlation between baseline or peak prolactin and milk quantity, while others demonstrate a low baseline prolactin concentration and absence of a prolactin response to suckling. 10,14,15 Of note, prolactin levels in response to breast pumping are lower than with infant suckling.12,16 Taken together, although a relationship exists between prolactin and milk volume, the direct effect of prolactin administration on milk volume has not been tested.

Recombinant human prolactin (r-hPRL) was used in an open-label trial to test the hypothesis that r-hPRL treatment would increase serum prolactin levels and milk production in prolactin-deficient mothers.17 In mothers of premature infants, pretreatment and r-hPRL-stimulated prolactin levels were monitored to test the hypothesis that increasing prolactin levels would increase milk volume in a dose-dependent fashion.

Methods

Both studies were approved by the Partners and Boston University Medical Center Human Research Committees. All subjects gave written informed consent for themselves and their infants. These pilot studies are presented together to provide preliminary evidence for the safety and effectiveness of r-hPRL.

Study 1: Open-label r-hPRL in prolactin-deficient mothers

Subjects (n = 5) were postpartum mothers with congenital or acquired prolactin deficiency (Table 1) who wished to breastfeed their infants. Subjects reported failure of milk production and produced <10 ml of milk per day. Baseline and/or peak prolactin levels were below the normal range for the appropriate postpartum age.12 Subjects had normal adrenal and thyroid function (Table S1).

Table 1.

Characteristics of mothers with prolactin deficiency (Study 1)

| Subject | Diagnosis | Weeks postpartum | Milk volume (ml/day) | Baseline serum PRL★ (μg/l) | Peak serum PRL† (μg/l) | Normal‡ |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Isolated prolactin deficiency | 4·9 | 0 | 0·06 | 0 | 0–7 weeks postpartum Baseline: 13–95 Peak: 122–370 |

| 2 | Idiopathic | 6 | 0 | 8·96 | 33·55 | |

| 3 | Sheehan syndrome | 6 | 8·0 | 34·52 | 93·12 | |

| 4 | Breast augmentation | 6 | 6·2 | 8·0 | 7·78 | |

| 5 | Sheehan syndrome | 39 | 2·9 | 3·77 | 4·93 | ≥8 weeks: Baseline: 4–21 Peak: 22–180 |

PRL, prolactin.

Baseline prolactin level.

Peak prolactin level in response to breast pumping.

Normative data in lactating women.12

Study 2: Randomized, double blind, placebo-controlled trial of r-hPRL in mothers with relative prolactin deficiency and lactation insufficiency

Subjects (n = 11) were mothers with lactation insufficiency who gave birth to preterm infants between 24- and 32-week gestation (Table 2). All subjects were exclusively pumping breast milk but reported a decline in milk production and produced <750 ml per day.18

Table 2.

Characteristics of subjects in the lactation insufficiency trial (Study 2) by treatment group

| Treatment | Age (years) | Gestational age at delivery (weeks) | Weeks postpartum | Pumping frequency (times/day) | Milk volume (ml/day) | Baseline serum PRL★ (μg/l) | Peak serum PRL† (μg/l) | Normal serum PRL‡ (lactating women) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| r-hPRL/r-hPRL n = 3 | 30 ± 5§ | 26·7 (25·9–27·1)¶ | 8·5 (5–12) | 5 (5–6) | 53·5 (10·5–106) | 14·2 (9·8–20·9) | 79·3 (17·5–190) | 0–7 weeks postpartum Baseline: 13–95 Peak: 122–370 ≥8 weeks: Baseline: 4–21 Peak: 22–180 |

| r-hPRL/Placebo n = 3 | 34 ± 3 | 25·7 (24·9–26·3) | 19·5 (9–39) | 7 (5–8) | 183 (29–408) | 21·2 (11·4–36·3) | 129 (16–302) | |

| Placebo/Placebo n = 4 | 32 ± 6 | 25·6 (23·7–29·4) | 7·8 (3·5–10) | 6 (5–7) | 317·2 (<1–726) | 56·5 (5·7–178) | 112 (8·5–308) |

PRL, prolactin; r-hPRL, recombinant human prolactin.

Baseline serum prolactin level.

Peak prolactin level in response to breast pumping.

Normative data in lactating women.12

Mean ± SD.

Mean (range).

Study protocol

Subjects did not take dopamine antagonists for at least 2 weeks before participating. All subjects were seen in the General Clinical Research Center at Massachusetts General or Brigham and Women’s Hospital and received an evaluation and instruction on pumping technique from the study’s lactation consultant (M.A., S.W. or A.M.), including the importance of infant contact, relaxation, hygiene, proper breast shield placement and pumping frequency. On day 1, subjects pumped both breasts simultaneously with a Medela Symphony breast pump (Medela Inc., McHenry, IL, USA) until there was no milk flow for 2 min. The milk volume was measured using a graduated container or syringe and recorded by the study nurses. Subjects continued to pump in this manner eight times per day throughout the study and recorded pumping times and milk volumes in a standardized log. The logs were returned and reviewed with the study physician at each study visit. Subjects also recorded their subjective stress level on a 10-point scale, latching by the infant and other types of contact with the infant before pumping including skin to skin contact (written report). On day 1 (pretreatment, Figs 1 and 3), blood samples were obtained immediately before the onset of pumping, every 10 min for 60 min then every 30 min for a total of 3 h.

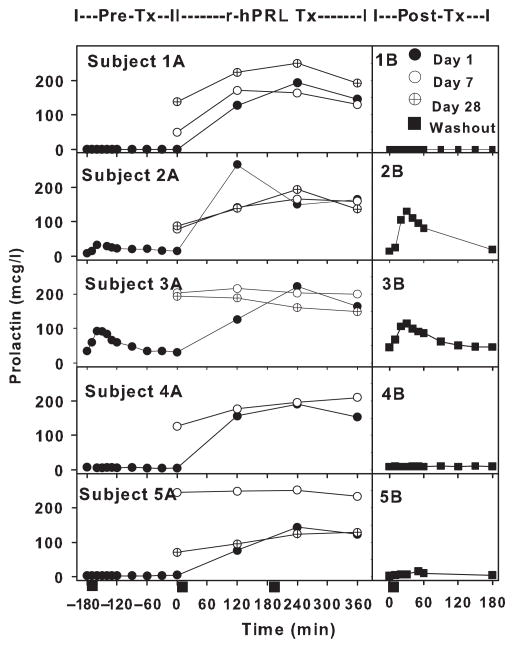

Fig. 1.

Serum prolactin levels in prolactin-deficient mothers (Study 1) before [pre-Tx (Tx = treatment); Subject 1A–5A], during (r-hPRL Tx; Subject 1A–5A) and after treatment (post-Tx; 1B–5B) with recombinant human prolactin (r-hPRL). Time −180 to 0 indicates endogenous serum prolactin levels in individual mothers during a pumping episode before r-hPRL treatment on day 1 (closed circles; pre-Tx; Subject 1A–5A). Serum prolactin levels are depicted starting at time 0 on day 1 (closed circles), day 7 (open circles) and day 28 (cross in circle), with r-hPRL administered at time 0 (r-hPRL Tx; Subject 1A–5A). Endogenous prolactin levels during a pumping episode 1 week after the last dose of r-hPRL are depicted in the second panel for each subject (closed squares; post-Tx; 1B–5B). Breast pumping began at time = 0 and lasted 15 min, as indicated (black rectangles).

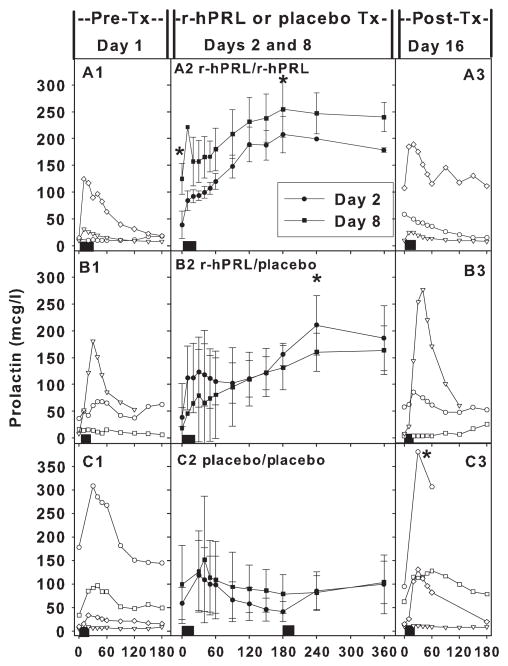

Fig. 3.

Individual prolactin levels pretreatment [day 1; pre-Tx (Tx = treatment); A1–C1] and post-treatment (day 16; post-Tx; A3–C3) and average prolactin levels during treatment on day 2 (closed circles) and day 8 (closed squares) in the three groups in Study 2 (A2 r-hPRL/r-hPRL; B2 r-hPRL/placebo; C2 Placebo/Placebo). (A) Recombinant human prolactin (r-hPRL) administered every 12 h resulted in an increase in baseline prolactin levels on day 8 (A2) compared to days 1(A1) and 2 (A2) (P < 0·05). R-hPRL every 12 h also increased peak prolactin levels on days 2 and 8 (A2) compared to day 1 (A1) (P < 0·03). (B) R-hPRL alternating with placebo resulted in increased peak prolactin levels on days 2 and 8 (B2) compared to day 1(B1) (P < 0·04). (C) Placebo treatment every 12 h demonstrated no change in baseline or peak prolactin levels (C2) compared to day 1 (C1). However, prolactin levels did increase on day 16 (C3) compared to day 1(C1) in the group treated with placebo (P = 0·02). Black rectangles indicate breast pumping.

Study 1

On day 1, 3 h after the initiation of pumping (pretreatment), r-hPRL (60 μg/kg) was administered subcutaneously, and blood samples were taken every 2 h for the next 6-h (r-hPRL treatment, Fig. 1). Subjects were taught to self-administer r-hPRL every 12 h for the subsequent 28 days. Subjects returned weekly for baseline blood sampling along with every 2-h blood sampling for 6 h on days 7 and 28. Blood was sampled 1 week later as on day 1 to document changes in endogenous prolactin levels (post-treatment, Fig. 1). All visits occurred at the same time of day for each subject.

Study 2

Subjects returned on day 2 and were randomized by the research pharmacy to receive r-hPRL (60 μg/kg), placebo (normal saline) or r-hPRL alternating with placebo every 12 h for 7 days (r-hPRL or placebo treatment, Fig. 3). Placebo and r-hPRL syringes were prepared by the research pharmacy and were identical in appearance and labelled with the time to be administered, i.e. am or pm. Blood samples were taken as on day 1, with an injection of the study medication after the first blood sample and additional blood samples 4 and 6 h after the initiation of pumping. Blood sampling was repeated on day 8 (day of the final injection) and on day 16 (after a 1-week washout period; post-treatment, Fig. 3). All visits occurred at the same time of day for each subject.

For both studies, a milk sample from the first morning pumping was obtained. Breast milk from each 24-h period could be fed to the infants if the milk prolactin level in this sample was within the normal range,19–21 but was discarded if the prolactin level was elevated. Infants were monitored for side effects during the first breast milk administration with constant pulse monitoring, blood pressure every 8 h, temperature every 3 h and GI output every 24 h. A subset of mothers and infants participating in Study 2 were followed for up to 1 year after participation (n = 7) with assessment of weight, height and intervening history.

Assays

Prolactin was measured using a 2-site monoclonal nonisotopic system (Axsym; Abbott Laboratories, Abbott Park, Illinois, USA). Development of prolactin antibodies and macroprolactin, a macromolecular complex of monomeric prolactin and an immunoglobulin that retains its immunological activity but not its biological activity,22 was assessed by measurement of prolactin before and after protein precipitation using polyethylene glycol.

Statistical analysis

Milk volumes are reported in ml per 24 h. Pretreatment volume and prolactin levels indicate levels before the study drug or placebo was administered (day 1). Baseline prolactin levels indicate morning prolactin levels prior to pumping and r-hPRL administration. Peak prolactin levels indicate the maximum value measured after pumping or morning injection of study drug. In all analyses, data were log transformed when not normally distributed. Changes in serum prolactin levels and milk volume were assessed using one-way ANOVA with repeated measures, ANOVA on ranks or two-way repeated measures ANOVA to compare groups, with Holm-Sidak or Dunnett’s post hoc testing depending on the number of observations. Infant weight and length were corrected for gestational age23 and compared during follow-up between treatment groups using ANOVA. The relationship between prolactin levels (baseline, peak, and area under the curve) and milk volumes was assessed using a Spearman correlation. Dichotomous variables were compared in treatment and placebo groups using Fisher’s exact test. All data are expressed as mean ± SEM unless otherwise indicated. A P value <0·05 was considered significant.

Results

Study 1: Response to open-label r-hPRL treatment in prolactin-deficient mothers

Characteristics of the mothers with prolactin deficiency are shown in Table 1 (n = 5). The aetiology of prolactin deficiency varied (Table 1 and Data S1). The diagnosis of Subject 1 is notable for isolated prolactin deficiency.6,7 Subject 2 entered 1 week after completing Study 2, where her low prolactin levels during placebo treatment met the criteria for Study 1. Subject 4 had a history of breast augmentation, with presumed nerve damage resulting in failure of afferent lactotroph stimulation.

The pretreatment response to pumping varied. Subject 1 had no detectable endogenous prolactin in her third trimester of pregnancy, prior to pumping (baseline) or in response to pumping (peak) (Table 1 and Fig. 1, Subject 1A). Subjects 4 and 5 also failed to mount a prolactin response (Fig. 1, Subjects 4A and 5A). Subject 3 had the highest response despite a diagnosis of Sheehan syndrome (Fig. 1, Subject 3A; Data S1 and Table S1).

During treatment with r-hPRL, baseline prolactin increased from 11·1 ± 6·1 μg/l at time 0 (day 1) to 140·4 ± 36·6 (day 7), 126·6 ± 25·2 (day 14), 145·6 ± 35·8 (day 21) and 122·4 ± 27·5 μg/l (day 28), with all baseline values significantly greater than on day 1 (P = 0·005; Time 0; Fig. 1, Subjects 1A–5A). Peak prolactin levels also increased on average from 27·9 ± 17·3 μg/l pretreatment (−160 min; Fig. 1, Subjects 1A–5A) to 195·9 ± 16·3 μg/l (day 7) (r-hPRL treatment; Fig. 1, Subjects 1A–5A) and 194·6 ± 19·5 μg/l (day 28), reaching normal postpartum levels in all subjects10,11 and with all values significantly greater than pretreatment (P = 0·002).

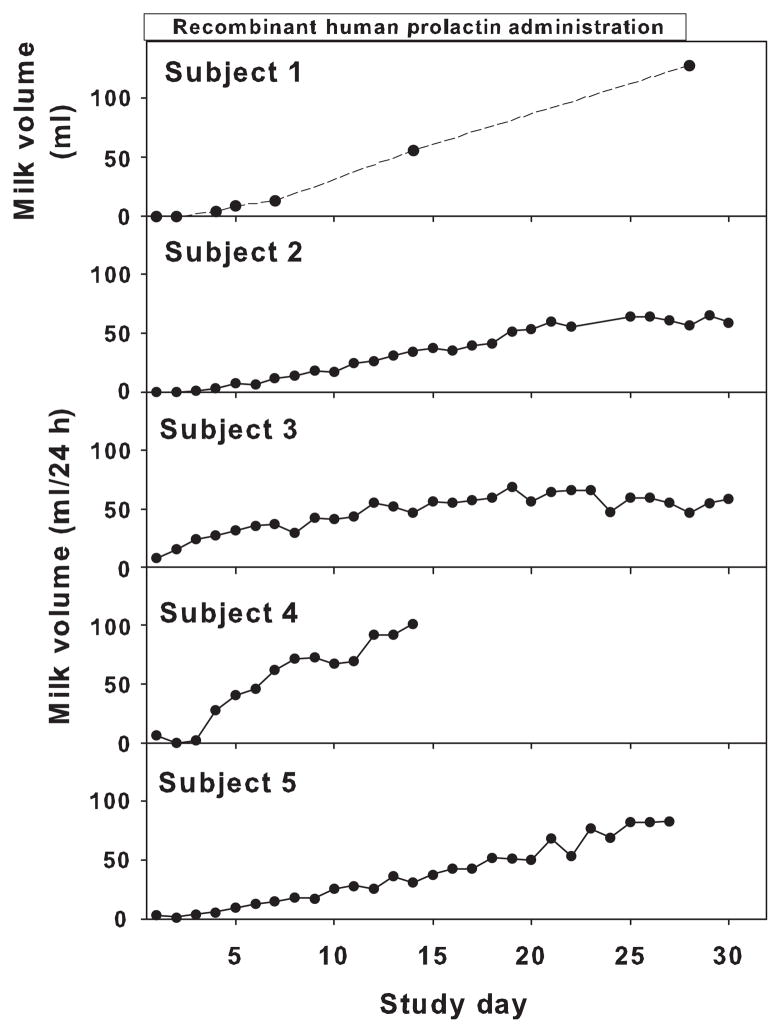

Milk production increased with r-hPRL treatment from 3·4 ± 1·6 ml/day to 66·1 ± 8·3 ml/day (P < 0·001; day 1 vs day 28; Fig. 2, Subjects 1–5). Interestingly, milk production in both subjects 2 and 3, who had endogenous prolactin increases during pretreatment pumping, reached a plateau at approximately 60 ml. Subject 1, who had isolated prolactin deficiency, began to produce drops of milk on day 2 of r-hPRL treatment and progressed to exclusively breastfeed her infant without supplemental formula starting on day 18. Subject 4 discontinued participation for personal reasons on day 14, despite a continued increase in milk production.

Fig. 2.

Individual milk volumes over 24 h (Subjects 2–5) in prolactin-deficient mothers during recombinant human prolactin (r-hPRL) treatment (Study 1). Subject 1, the mother with isolated prolactin deficiency, measured breast milk volume only from the first morning pumping episode. The change in milk volume was significant for all subjects (P < 0·001).

Compared to pretreatment (day 1), the peak prolactin response to pumping was enhanced in Subject 2 and maintained in Subject 3 (day 35; post-treatment; Fig. 1, 2B and 3B), while it declined to pretreatment levels in the rest of the subjects (post-treatment; 1B, 4B and 5B). Thus, there was no increase in the average peak prolactin 1 week after the last r-hPRL dose compared to pretreatment peak levels (post-treatment peak prolactin 54·9 ± 27·9 μg/l; P = 0·2). Milk volume dropped after washout (day 35) and was comparable to the pretreatment volume (post-treatment milk volume 9·4 ± 5·4 ml/day; P = 0·3). There was no correlation between baseline or peak prolactin level and milk volume pretreatment (day 1) or on the last day of treatment (day 28) with r-hPRL.

Study 2: Response to r-hPRL treatment in a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of r-hPRL in mothers with relative prolactin deficiency and lactation insufficiency

Characteristics and medical histories of the mothers and neonates are shown (Tables 2, S2 and S3). The mean gestational age was 25·6 ± 1·8 (mean ± SD) weeks, and the cause of premature delivery included placental abruption, pre-eclampsia, intrauterine growth retardation, premature labour, premature rupture of membranes and chorioamnionitis. Four subjects tried metoclopramide with the current or previous infants, two with no response and two with increases in milk volume that returned to baseline after metoclopramide was stopped (Table S2). The physical exams demonstrated soft breast tissue with absence of glandular fullness and absence of enlarged veins. Three subjects received r-hPRL, three subjects received r-hPRL alternating with placebo and four subjects received placebo every 12 h. One subject randomized to r-hPRL every 12 h did not comply with breast pumping and completed only three injections, therefore, her data were not included. There were no differences in age, gestational age, weeks postpartum, pumping frequency, milk volume, baseline or peak prolactin levels among the three treatment groups (all P > 0·5; Table 2). Baseline prolactin (r = 0·9, P < 0·001) correlated with pretreatment milk volume (day 1), but there was no relationship between pretreatment prolactin peak or area under the curve, age, gestational age or postpartum age and pretreatment milk volume.

Baseline prolactin (14·2 ± 3·4 vs 124·7 ± 28·6 μg/l; day 1 vs day 8; P < 0·05) and peak prolactin levels (79·3 ± 55·4 vs 271·3 ± 36·7 μg/l; day 1 vs day 8; P < 0·03) increased in the group that received twice daily r-hPRL (Fig. 3, A2 vs A1). Peak prolactin levels increased in the group treated with once daily r-hPRL alternating with placebo (101·4 ± 61·5 vs 178·9 ± 45·9 μg/l; day 1 vs day 8; P < 0·04), although baseline levels did not change (21·2 ± 7·6 vs 14·4 ± 5·0 μg/l; day 1 vs day 8; P = 0·2) (Fig. 3, B2 vs B1). Neither baseline (56·5 ± 40·9 vs 98·8 ± 82·9 μg/l; day 1 vs day 8; P = 0·3) nor peak prolactin levels (111·7 ± 68·1 vs 129·9 ± 57·9 μg/l; day 1 vs day 8; P = 0·2) increased in the group treated with placebo every 12 h (Fig. 3 C2 vs C1,), despite the instruction in breast pumping and lactation support that all subjects received. There was an increase in endogenous peak prolactin levels on day 16 compared to day 1 in the group treated with placebo every 12 h (P = 0·02; Fig. 3 C3 vs C1,), but not in the other groups.

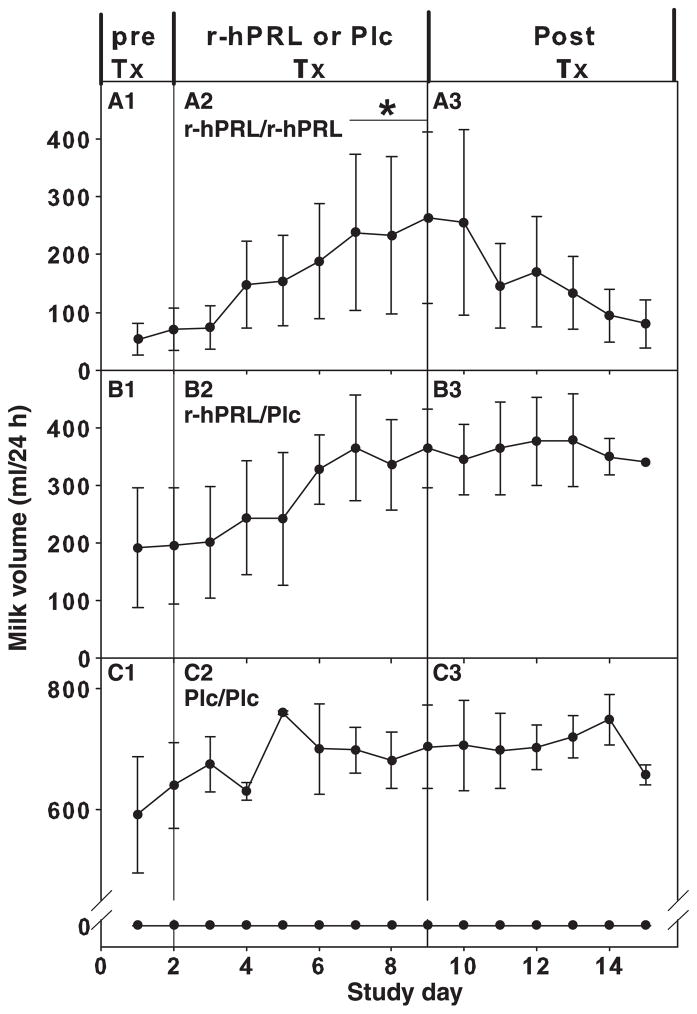

Milk volume increased in subjects treated with twice daily prolactin, but not in subjects treated with once daily prolactin or placebo (P < 0·01; Fig. 4, A2–C2 vs A1–C1). Milk volume was increased on the final 3 days surrounding r-hPRL treatment every 12 h compared to baseline (53·5 ± 48·5 vs 238·3 ± 125·0, 235·0 ± 135·7 and 257·5 ± 148·7 mL/day 1 vs day 7, 8 and 9, respectively; P < 0·05; Fig. 4, A2). The per cent change in milk volume on the final day of r-hPRL administration (day 8 compared to day 1) was different in the three groups (one-way ANOVA on ranks P < 0·05). Post hoc testing revealed that milk volumes were higher in the group treated with twice daily r-hPRL (429 ± 338%) than in the group receiving only placebo (−12 ± 27%; P < 0·05), but not compared to the group receiving r-hPRL alternating with placebo (44 ± 28%). Milk volume was not correlated with baseline serum prolactin level, peak serum prolactin or area under the curve on study day 8. Milk volume was also not correlated with stress level or infant contact.

Fig. 4.

Milk volume in r-hPRL and placebo (Plc) groups (Study 2). (A) Milk volume increased in the group treated with r-hPRL every 12 h (A2 r-hPRL/r-hPRL vs A1). (B) Milk volume did not increase in the group treated with r-hPRL alternating with placebo every 12 h (B2 r-hPRL/Plc vs B1). (C) Milk volume did not increase in the group treated with placebo every 12 h (C2 Plc/Plc vs C1). Subjects with no milk production at baseline are depicted separately from subjects with milk production at baseline. ★Significantly different from baseline (day 2), P < 0·05.

One week after discontinuation of treatment (day 16; post-treatment), there was no decrease in milk volume in the group on average (P = 0·9; Fig. 4, A3–C3), although volume decreased to baseline (day 1) levels in two of three subjects treated with r-hPRL every 12 h. There was no change in the number of pumping episodes per day on the final day of treatment or on the last day of the washout period in the group overall (6·2 ± 0·4, 6·2 ± 0·4 and 6·3 ± 0·6; day 1, day 8 and day 16; P = 0·1) or on the basis of treatment (P = 0·1).

Four subjects had higher (baseline or peak) endogenous prolactin levels in the 3 h surrounding pumping on the final visit, 1 week after completion of r-hPRL or placebo treatment (day 16). The increase was not related to macroprolactin, which decreased after treatment with r-hPRL (31·8 ± 1·8 vs 29·6 ± 1·5%; day 1 vs day 8; P = 0·03), was similar to placebo (24·5 ± 4·6 vs 24·1 ± 4·6%; day 1 vs day 8; P = 0·8) and did not meet the threshold for detection (>60%).22 Three subjects continued to breast feed for 1 year and 2 stopped at 3–6 months for personal reasons. Four subjects stopped before NICU discharge, including two in the placebo group who did not make milk and two whose milk volume plummeted after stopping r-hPRL. One subject did not follow-up. There was no difference in duration of breast milk use on the basis of treatment (P = 0·6).

Safety

Safety measures were assessed combining all 15 study subjects. There were no serious adverse events. Minor adverse effects in mothers were well tolerated and occurred in a similar proportion in the placebo (n = 4) and r-hPRL groups (n = 11; P = 0·1; Table S4). Tiredness (n = 5 r-hPRL, n = 2 placebo), and marks or bruising at the injection site (n = 8 r-hPRL, n = 3 placebo) occurred in both groups. Headache (n = 2), onset of menses, tingling in hands, nausea and dry skin (all n = 1) occurred only in subjects treated with r-hPRL.

Prolactin levels in breast milk were in the normal range with the exception of one high level in one sample in one subject.19–21 No adverse events were observed in the eight infants fed breast milk produced during the study (9/15). Six infants were followed longitudinally in Study 2. The data were compared for infants with any r-hPRL exposure (n = 4) and placebo (n = 2). There was no difference in the weight and height trajectories in the r-hPRL or placebo groups (P = 0·6 and P = 0·1; respectively). There was also no difference in the rate of respiratory illness during follow-up (3 of 4 r-hPRL and 1 of 2 placebo; P = 0·4).

Discussion

R-hPRL increased serum prolactin levels and milk volume in prolactin-deficient mothers. R-hPRL also increased prolactin levels and milk volume in mothers with lactation insufficiency that developed while pumping breast milk for premature infants. Data from the mothers with lactation insufficiency additionally demonstrate that r-hPRL must be administered every 12 h to increase milk volume, suggesting that an elevated baseline prolactin or an increase over a 24-h period may be important. Taken together with few side effects in the treated mothers and infants, these results provide the first evidence that r-hPRL may be a viable option for treatment of lactation insufficiency.

In mothers with Sheehan syndrome or congenital prolactin deficiency, lactotrophs are absent or decreased in number. Dopamine antagonists, such as metoclopromide and domperidone, rely on functional lactotrophs to respond. Therefore, they will fail in central prolactin deficiency, as evidenced in subjects 1–3, who lacked endogenous prolactin secretion or suffered from Sheehan syndrome and failed to respond to domperidone or metoclopramide. Therefore, administration of prolactin is the only viable treatment option for these women.

R-hPRL restored normal lactation in Subject 1 with isolated prolactin deficiency, resulting in an adequate milk supply. In the other four prolactin-deficient women, r-hPRL increased milk production 9- to 65-fold but not adequately to fully feed the infants after 28 days of treatment. Milk volume increased throughout the treatment period in two subjects, suggesting that prolactin continues to drive production of osmotic factors that control volume or enhances mammary epithelial proliferation and that prolonged exposure may be beneficial.24–26 In contrast, milk volumes plateaued in the final two subjects suggesting that increasing epithelial cell or glandular capacity continues to be required for milk production. Regardless of the response during r-hPRL treatment, the milk volume in all subjects decreased to baseline after treatment as expected in subjects with prolactin deficiency, even in two subjects who had an apparent improvement in their endogenous prolactin, demonstrating that r-hPRL treatment must continue throughout lactation in this population of mothers.

Mothers of preterm infants exhibited only relative prolactin deficiency. Five of ten subjects had low peak prolactin levels, and two also had low baseline prolactin levels compared to average values from mothers at the same postpartum stage, as seen previously.8,12 The relatively low prolactin levels may have been related to use of a breast pump.27 Additionally, the number of prolactin peaks and falls across the day and milk removal were inadequate as only one mother pumped 8 times per day as recommended.18 The current study provides evidence that increasing prolactin levels improves milk volume in a group of mothers with relative prolactin deficiency.

While the current study is the first to use r-hPRL, previous studies demonstrated that raising prolactin indirectly, by suppressing dopamine-negative feedback, results in increased milk volume.8,28– 33 Neither dopamine antagonists nor r-hPRL replicates the physiologic prolactin pattern during lactation as they elevate prolactin across the day.12,15 Taken together with the absence of increased milk volume using once daily r-hPRL, it appears that prolactin must be elevated and elevation sustained across the day to increase milk supply. Importantly, the transient increase in prolactin during pumping was maintained with r-hPRL treatment but was not demonstrable in other studies (Fig. 3).8,28 Further, despite similar baseline (90–170 μg/l) and peak prolactin levels (140 μg/l) in r-hPRL and dopamine antagonist-treated subjects, the milk volume increase was slightly better with r-hPRL (450%) than with dopamine antagonists (44–267%).8,28–33 Although no head to head studies have been performed, it is possible that the persistent endogenous prolactin release with pumping may enhance volume in women treated with r-hPRL.

The individual increases in milk volume with treatment were variable and unrelated to baseline or peak prolactin levels. When our raw data were combined with those of da Silva,30 there was an inverse correlation between the per cent increase in milk volume and volume at baseline (r=−0·8; P < 0·001), whereas the final volume achieved correlated with baseline volume (r = 0·8; P < 0·001). Thus, the proportional increase in milk volume appears to be highest in women with the lowest milk volume at baseline, although the final volume achieved appears to be greatest in women with higher volumes at baseline. Thus, the severity of the volume defect may affect the response to r-hPRL in women with lactation insufficiency. Further study is required to test this hypothesis.

There was also a divergence between the endogenous prolactin and milk volume response after cessation of treatment. Three subjects maintained improved lactation after initial r-hPRL treatment as in studies with other galactogogues.29 One of these subjects had an improvement in endogenous prolactin secretion, while the other two subjects exhibited no change, leaving the possibility that milk removal improved or that r-hPRL had a direct effect on breast function. In contrast, three subjects in groups treated with r-hPRL had decreased milk volume after stopping treatment despite paradoxical maintenance or improvement in endogenous prolactin levels on the final visit. Taken together with absence of macroprolactin, which is immunologically but not biologically active prolactin,22,34,35 these observations suggest that endogenous prolactin secretion can be improved without improved milk volume and thus that the degree of the prolactin increase may not be adequate or improvement in other parameters, such as milk removal, is necessary.

R-hPRL was associated with few side effects during short-term administration in a total of 29 women.36,37 In all of these studies, the most common side effect of r-hPRL administration has been bruising or marks at the injection site, followed by tiredness. Thus, the side effect profile may be better than for other galactagogues.9 The administration of r-hPRL did not increase macroprolactin (PRL/anti-PRL antibody complexes), suggesting that the formation of antibodies to the recombinant form is not a major concern.34,35 Finally, r-hPRL is likely excreted in breast milk, but concentrations did not exceed prolactin levels occurring during normal lactation, and there were no noted side effects in infants treated for up to 28 days.

The primary limitation of this investigation was the small sample size. A larger study is needed to confirm short- and long-term safety and to perform an intention to treat analysis. A second limitation was the heterogeneity of the subjects. In Study 1, prolactin deficiency was secondary to a variety of aetiologies, perhaps accounting for the differing responses. Using a standardized prolactin stimulation test for study inclusion may have homogenized the subjects, but was not performed owing to time and concerns about the effect of pretreatment. Milk volume did increase in all subjects treated with r-hPRL regardless of the aetiology of prolactin deficiency, but further study is required to determine which prolactin-deficient mothers will have a complete vs partial response. In Study 2, the timing of r-hPRL treatment initiation may account for differing responses. It is possible that early initiation of r-hPRL therapy in mothers of preterm infants would lead to greater milk volumes. A third limitation is the short-term nature of these studies. Although one prolactin-deficient subject was able to exclusively breastfeed her infant after the initiation of r-hPRL therapy, it is unclear whether longer-term administration would have increased milk volume sufficiently to meet infant requirements in other subjects. However, even a partial response would be of benefit, particularly for premature infants.1

In conclusion, prolactin is required for breast milk production, and direct administration of prolactin increases milk volume. R-hPRL appears to be safe and efficacious for increasing milk supply in both mothers of preterm infants with lactation insufficiency and mothers with prolactin deficiency. Studies of the safety and effectiveness of long-term administration of this agent in mothers of preterm infants and mothers with prolactin deficiency are warranted.

Supplementary Material

Data S1 Case histories: prolactin-deficient mothers.

Table S1 Baseline hormone levels in mothers with prolactin deficiency.

Table S2 Case histories: mothers of premature infants.

Table S3 Case histories: premature infants.

Table S4 Adverse events.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the mothers who participated for their extraordinary efforts during the study. We would also like to thank Genzyme Corporation for supplying the recombinant human prolactin. Finally, we thank Dr. Robert Insoft, Dr. Karen K. Miller and Diane Dady-Goldstein, RN, IBCLC, for advice and assistance while serving on our data safety monitoring board. This work was supported by the Food and Drug Administration FD-R-003014, the March of Dimes Birth Defects Foundation research Grant No. 6-FY04-76 and the National Center for Research Resources General Clinical Research Centers Program grant M01-RR-01066.

Footnotes

Disclosure statement

The recombinant human prolactin was provided by Genzyme Corporation. C.K.W. received an unrestricted grant from Genzyme Corporation. Genzyme Corporation was not involved in the study conception, design, recruitment, data collection, analysis or manuscript preparation.

References

- 1.Gartner LM, Morton J, Lawrence RA, et al. Breastfeeding and the use of human milk. Pediatrics. 2005;115:496–506. doi: 10.1542/peds.2004-2491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cumming RG, Klineberg RJ. Breastfeeding and other reproductive factors and the risk of hip fractures in elderly women. International Journal of Epidemiology. 1993;22:684–691. doi: 10.1093/ije/22.4.684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Stuebe AM, Schwarz EB. The risks and benefits of infant feeding practices for women and their children. Journal of Perinatology. 2010;30:155–162. doi: 10.1038/jp.2009.107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Neifert M, DeMarzo S, Seacat J, et al. The influence of breast surgery, breast appearance, and pregnancy-induced breast changes on lactation insufficiency as measured by infant weight gain. Birth. 1990;17:31–38. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-536x.1990.tb00007.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Neifert MR. Prevention of breastfeeding tragedies. Pediatric Clinics of North America. 2001;48:273–294. doi: 10.1016/s0031-3955(08)70026-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kauppila A, Chatelain P, Kirkinen P, et al. Isolated prolactin deficiency in a woman with puerperal alactogenesis. Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism. 1987;64:309–312. doi: 10.1210/jcem-64-2-309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Turkington RW. Phenothiazine stimulation test for prolactin reserve: the syndrome of isolated prolactin deficiency. Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism. 1972;34:246–249. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ehrenkranz RA, Ackerman BA. Metoclopramide effect on faltering milk production by mothers of premature infants. Pediatrics. 1986;78:614–620. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Anderson PO, Valdes V. A critical review of pharmaceutical galactagogues. Breastfeeding Medicine. 2007;2:229–242. doi: 10.1089/bfm.2007.0013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Aono T, Shioji T, Shoda T, et al. The initiation of human lactation and prolactin response to suckling. Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism. 1977;44:1101–1106. doi: 10.1210/jcem-44-6-1101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Johnston JM, Amico JA. A prospective longitudinal study of the release of oxytocin and prolactin in response to infant suckling in long term lactation. Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism. 1986;62:653–657. doi: 10.1210/jcem-62-4-653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Noel GL, Suh HK, Frantz AG. Prolactin release during nursing and breast stimulation in postpartum and nonpostpartum subjects. Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism. 1973;38:413–423. doi: 10.1210/jcem-38-3-413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Brun del Re R, del Pozo E, de Grandi P, et al. Prolactin inhibition and suppression of puerperal lactation by a Br-ergocryptine (CB 154) Obstetrics and Gynecology. 1973;41:884–890. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hennart P, Delogne-Desnoeck J, Vis H, et al. Serum levels of prolactin and milk production in women during a lactation period of thirty months. Clinical Endocrinology. 1981;14:349–353. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2265.1981.tb00619.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Howie PW, McNeilly AS, McArdle T, et al. The relationship between suckling induced prolactin response and lactogenesis. Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism. 1980;50:670–673. doi: 10.1210/jcem-50-4-670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hill PD, Aldag JC, Demirtas H, et al. Association of serum prolactin and oxytocin with milk production in mothers of preterm and term infants. Biological Research for Nursing. 2009;10:340–349. doi: 10.1177/1099800409331394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Price AE, Logvinenko KB, Higgins EA, et al. Studies on the microheterogeneity and in vitro activity of glycosylated and nonglycosylated recombinant human prolactin separated using a novel purification process. Endocrinology. 1995;136:4827–4833. doi: 10.1210/endo.136.11.7588213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hill PD, Brown LP, Harker TL. Initiation and frequency of breast expression in breastfeeding mothers of LBW and VLBW infants. Nursing Research. 1995;44:352–355. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Healy DL, Rattigan S, Hartmann PE, et al. Prolactin in human milk: correlation with lactose, total protein, and a-lactalbumin levels. American Journal of Physiology. 1980;238:E83–E86. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.1980.238.1.E83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yuen BH. Prolactin in human milk: the influence of nursing and the duration of postpartum lactation. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology. 1988;158:583–586. doi: 10.1016/0002-9378(88)90032-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gala RR, Singhakaowinta A, Brennan MJ. Studies on prolactin in human serum, urine and milk. Hormone Research. 1975;6:310–320. doi: 10.1159/000178680. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Viera JF, Tachibana TT, Obara LH, et al. Extensive experience and validation of polyethylene glycol precipitation as a screening method for macroprolactinemia. Clinical Chemistry. 1998;44:1758–1759. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kessler DB, Dawson P. Failure to Thrive and Pediatric Undernutrition – A Transdisciplinary Approach. Brookes Publishing Co; Baltimore: 1999. p. 579. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Neville MC. Anatomy and physiology of lactation. Pediatric Clinics of North America. 2001;48:13–33. doi: 10.1016/s0031-3955(05)70283-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ostrom KM. A review of the hormone prolactin during lactation. Progress in Food and Nutrition Science. 1990;14:1–43. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Oka T, Topper YJ. Is prolactin mitogenic for mammary epithelium? Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 1972;69:1693–1696. doi: 10.1073/pnas.69.7.1693. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zinaman MJ, Hughes V, Queenan JT, et al. Acute prolactin and oxytocin responses and milk yield to infant suckling and artificial methods of expression in lactating women. Pediatrics. 1992;89:437–440. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wan EW, Davey K, Page-Sharp M, et al. Dose-effect study of domperidone as a galactagogue in preterm mothers with insufficient milk supply, and its transfer into milk. British Journal of Clinical Pharmacology. 2008;66:283–289. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2125.2008.03207.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Petraglia F, De Leo V, Sardelli S, et al. Domperidone in defective and insufficient lactation. European Journal of Obstetrics, Gynecology, and Reproductive Biology. 1985;19:281–287. doi: 10.1016/0028-2243(85)90042-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.da Silva OP, Knoppert DC, Angelini MM, et al. Effect of domperidone on milk production in mothers of premature new-borns: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Canadian Medical Association Journal. 2001;164:17–21. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kauppila A, Kivinen S, Ylikorkala O. Metoclopramide increases prolactin release and milk secretion in puerperium without stimulating the secretion of thyrotropin and thyroid hormones. Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism. 1981;52:436–439. doi: 10.1210/jcem-52-3-436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Campbell-Yeo ML, Allen AC, Joseph KS, et al. Effect of domperidone on the composition of preterm human breast milk. Pediatrics. 2010;125:e107–e114. doi: 10.1542/peds.2008-3441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.de Gezelle H, Ooghe W, Thiery M, et al. Metoclopramide and breast milk. European Journal of Obstetrics, Gynecology, and Reproductive Biology. 1983;15:31–36. doi: 10.1016/0028-2243(83)90294-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hattori N, Ishihara T, Ikekubo K, et al. Autoantibody to human prolactin in patients with idiopathic hyperprolactinemia. Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism. 1992;75:1226–1229. doi: 10.1210/jcem.75.5.1430082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Leite V, Cosby H, Sobrinho LG, et al. Characterization of big, big prolactin in patients with hyperprolactinemia. Clinical Endocrinology. 1992;37:365–372. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2265.1992.tb02340.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Page-Wilson G, Smith PC, Welt CK. Prolactin Suppresses GnRH but Not TSH Secretion. Hormone Research. 2006;65:31–38. doi: 10.1159/000090377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Page-Wilson G, Smith PC, Welt CK. Short-term prolactin administration causes expressible galactorrhea but does not affect bone turnover: pilot data for a new lactation agent. International Breastfeeding Journal. 2007;2:10. doi: 10.1186/1746-4358-2-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data S1 Case histories: prolactin-deficient mothers.

Table S1 Baseline hormone levels in mothers with prolactin deficiency.

Table S2 Case histories: mothers of premature infants.

Table S3 Case histories: premature infants.

Table S4 Adverse events.