Summary

Aims

Palmitoylation of α‐amino‐3‐hydroxy‐5‐methyl‐4‐isoxazolepropionic acid receptors (AMPARs) subunits or their “scaffold” proteins produce opposite effects on AMPAR surface delivery. Considering AMPARs have long been identified as suitable drug targets for central nervous system (CNS) disorders, targeting palmitoylation signaling to regulate AMPAR function emerges as a novel therapeutic strategy. However, until now, much less is known about the effect of palmitoylation‐deficient state on AMPAR function. Herein, we set out to determine the effect of global de‐palmitoylation on AMPAR surface expression and its function, using a special chemical tool, N‐(tert‐Butyl) hydroxylamine (NtBuHA).

Methods

BS 3 protein cross‐linking, Western blot, immunoprecipitation, patch clamp, and biotin switch assay.

Results

Bath application of NtBuHA (1.0 mM) reduced global palmitoylated proteins in the hippocampus of mice. Although NtBuHA (1.0 mM) did not affect the expression of ionotropic glutamate receptor subunits, it preferentially decreased the surface expression of AMPARs, not N‐methyl‐d‐aspartate receptors (NMDARs). Notably, NtBuHA (1.0 mM) reduces AMPAR‐mediated excitatory postsynaptic currents (mEPSCs) in the hippocampus. This effect may be largely due to the de‐palmitoylation of postsynaptic density protein 95 (PSD95) and protein kinase A‐anchoring proteins, both of which stabilized AMPAR synaptic delivery. Furthermore, we found that changing PSD95 palmitoylation by NtBuHA altered the association of PSD95 with stargazin, which interacted directly with AMPARs, but not NMDARs.

Conclusion

Our data suggest that the palmitoylation‐deficient state initiated by NtBuHA preferentially reduces AMPAR function, which may potentially be used for the treatment of CNS disorders, especially infantile neuronal ceroid lipofuscinosis (Batten disease).

Keywords: AMPA receptor, N‐(tert‐Butyl) hydroxylamine, palmitoylation, postsynaptic density protein 95, stargazin

1. INTRODUCTION

Glutamate is the major excitatory neurotransmitter in the central nervous system (CNS). Ionotropic glutamate receptors (iGluRs), including α‐amino‐3‐hydroxy‐5‐methyl‐4‐isoxazolepropionic acid (AMPA)‐type and N‐methyl‐D‐aspartate (NMDA)‐type receptors, mediate the most of glutamate functions. Moreover, AMPARs mainly mediate the majority of fast excitatory synaptic transmission in the mammalian brain.1 The number of postsynaptic AMPARs is closely linked to excitatory synaptic strength2 and is dynamically regulated by activity‐dependent mechanisms, including post‐translational protein modification of AMPARs and their “scaffold” proteins, which stabilize receptors to specific subcellular locations.3, 4

Recently, a post‐translational modification targeting the cysteine residue, named S‐palmitoylation, has emerged to be critical for the modulation of AMPARs function.5, 6 S‐palmitoylation refers to the formation of a reversible thioester linkage of a palmitoyl lipid as sticky “tag” to the thiol of cysteine residue, which is tuned by the palmitoyl acyl transferase‐catalyzed palmitoylation and a reverse process, palmitoyl‐protein thioesterase‐catalyzed de‐palmitoylation.7 Both AMPARs and their binding partners are especially key targets for palmitoylation.8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15 For instance, AMPARs subunits, such as GluA1 and GluA2, have a cysteine residue close to the pore (C585 in GluA1, C610 in GluA2), which can be palmitoylated, following by a decrease in their insertion into the plasma membrane and an increase in their accumulation in the Golgi apparatus.8 Another residue in GluA1, C811 has been seen to be important in the modulation of 4.1N‐dependent GluA1 surface insertion via a mechanism to restrict phosphorylation of S816 and S818 residues.9 In contrast, palmitoylation of N‐terminal polybasic domain of protein kinase A‐anchoring protein 79/150 (AKAP79/150), a key AMPAR regulatory scaffold protein, facilitates surface delivery of AMPAR.10, 11 Postsynaptic density protein 95 (PSD95), the key postsynaptic scaffold protein for GluRs, is associated with AMPARs or NMDARs only in its palmitoylated conformation.12, 13, 14, 15 As for AMPARs, NMDAR function is also affected by palmitoylation,16, 17 although the regulation of NMDARs by palmitoylation is complex.18 Palmitoylation of AMPARs and their partners is mediated by a group of enzymes named palmitoyl transferases (PATs), which contains an Asp‐His‐His‐Cys (DHHC) Cys‐rich domain. Conversely, de‐palmitoylation is mediated by different thioesterases, of which very few have been identified so far.

Aberrant protein palmitoylation signaling may be implicated in the pathogenesis of various diseases, including human cancer, infantile neuronal ceroid lipofuscinosis (INCL), and brain insulin resistance.19, 20, 21, 22, 23 Emerging evidence shows that palmitoylation of AMPARs is sensitive to psychostimulants such as cocaine,24 which may control psychomotor sensitivity to the psychostimulants. Thus, pharmacological initiation of palmitoylation‐deficient state may potentially be used for drug addiction. Furthermore, AMPARs have long been identified as suitable drug targets for central nervous system (CNS) disorders, such as epilepsy and autism.25, 26 Thus, targeting palmitoylation signaling to regulate AMPAR function emerges as a novel therapeutic strategy. However, until now, much less is known about the effect of palmitoylation‐deficient state on AMPAR function. It should be noted that palmitoylation of receptors or their “scaffold” proteins always produces opposite effects on the surface delivery of AMPAR. Thus, global deficiency in palmitoylation signaling may produce complex effects.

For the lack in the knowledge about depalmitoylases for AMPAR and its binding partners, 2‐bromopalmitate (2‐BP), the broad‐spectrum palmitoylation inhibitor, has been widely used to investigate the effect of de‐palmitoylation via downregulating the palmitoylated protein level.21, 27, 28, 29, 30, 31 Interestingly, the effect of 2‐BP on the AMPAR function seems contradictory. It has been reported that 2‐BP attenuates AMPAR‐activated Ca2+ signaling and cytotoxicity in motor neurons.29 However, 2‐BP exerts little effect on the palmitoylation or surface expression of AMPAR in the normal rats, but reverts GluA1 hyper‐palmitoylation in the rats treated by high‐fat diet or cocaine,21, 24 which may upregulate surface expression of AMPAR. It should be noted that as an irreversible nonselective inhibitor of palmitoyl acyl transferases, 2‐BP only blocks palmitate addition27, 28 and allows palmitoylation “run down” naturally, not de‐palmitoylation rapidly and directly. Moreover, it has been revealed that 2‐BP is a nonselective probe with many targets beyond palmitoyl transferases.32 Thioester linkage in palmitoyl~CoA as well as in palmitoylated proteins is cleaved by hydroxylamine with high specificity.33 N‐(tert‐Butyl) hydroxylamine (NtBuHA) is a nontoxic hydroxylamine derivative that screened from hydroxylamine derivatives that mimic thioesterases22, 23 to treat diseases such as INCL. In this study, we used NtBuHA as a specific chemical tool to investigate the effect of globally de‐palmitoylation on the surface expression and function of GluRs.

2. MATERIALS AND METHODS

2.1. Animals

Male C57BL/6J mice (7‐9 weeks,22‐24 g) were purchased from Hunan SJA Laboratory Animal (Changsha, Hunan, China) and maintained on a controlled 12:12 hours light cycle at a constant temperature (22 ± 2°C) and humidity of 50 ± 10% with food and water. The use of animals for experimental procedures was conducted in accordance with the Guide for Care and Use of Laboratory Animals as adopted and promulgated by the National Institutes of Health. The experimental procedures were approved by the Animal Welfare Committee of Huazhong University of Science & Technology.

2.2. Agents

N‐(tert‐Butyl)hydroxylamine hydrochloride (NtBuHA), methyl methane thiosulfonate (MMTS), hydroxylamine (HA) hydrochloride, neocuproine, and streptavidin‐agarose were purchased from Sigma‐Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA). N‐(6‐(Biotinamido)hexyl)‐3′‐(2′‐pyridyldithio)‐propionamide (HPDP)‐biotin and Bis(sulfosuccinimidyl) suberate (BS3) were purchased from Thermo Fisher Scientific (Waltham, MA, USA). Protein A/G PLUS‐Agarose was purchased from Santa Cruz Biotechnology. Other agents were purchased from commercial suppliers.

2.3. NtBuHA treatment

NtBuHA was directly dissolved in the artificial cerebrospinal fluid (aCSF) consisting of (mmol/L): (119.0 mmol/L NaCl, 3.5 KCl, 1.0 NaH2PO4, 1.3 MgSO4, 26.2 NaHCO3, 2.5 CaCl2, and 11.0 glucose to the final concentrations at room temperature.

We performed molecular studies using hippocampal slices to maintain consistency with electrophysiology experiment condition. Male C57BL/6J mice were anesthetized with pentobarbital sodium (45 mg/kg, ip, Sinopharm Chemical Reagent Co., Ltd., China). The brains were quickly decapitated (within 1 minute) and then moved to ice‐cold oxygenated aCSF. Coronal bilateral slices (350 μm in thickness) containing the hippocampus were cut by a vibratome (VT 1000S, Leica, Wetzlar, Germany) in aCSF and then transferred to a holding chamber with aCSF to incubate at 27°C for 1.0 hours. Then, hippocampal slices were transferred into a chamber with aCSF containing NtBuHA of various concentrations (0, 0.25, 0.5, and 1 mmol/L) to incubate at 27°C for 30 minutes. Finally, slices were collected and transferred into Eppendorf tubes or a submerged recording chamber to perform following experiments, including Western blot, the surface cross‐linking assay, the Co‐IP experiments, and the electrophysiological experiments.

2.4. Western blot

Western blot was performed as described in our previous studies.34 After treatment, hippocampal slices were collected and transferred into the Eppendorf tubes, homogenizing with Radio‐Immunoprecipitation Assay (RIPA) buffer (50 mM Tris‐HCl, pH 7.4, 1% NP‐40, 0.5% Na‐deoxycholate, 0.1% Sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS), 150 mmol/L NaCl, 2 mmol/L EDTA, and 50 mmol/L NaF) including protease and phosphatase inhibitors (10 μL/mg tissue). Lysates were clarified by centrifuged at 12 000 g for 15 minutes at 4°C, and then, the concentration of protein was measured by Coomassie blue protein‐binding assay (Nanjing Jiancheng Institute of Biological Engineering, Nanjing, China). Protein samples were boiled at 95°C in SDS‐loading buffer for 5 minutes. Samples (30 μg) were separated by 10% SDS‐polyacrylamide gel and then transferred to nitrocellulose membranes (Schleicher and Schuell, Keene, NH, USA). After blocking with 5% bovine serum albumin (BSA) in Tris‐buffered saline containing 0.1% Tween‐20 (TBST) for 1 hours at room temperature, the membranes were incubated overnight at 4°C with the following primary antibodies: β‐actin (1:3000, sc‐47778, Santa Cruz), PSD95 (1:1000, ab12093, Abcam), GluA1 (1:1000, ab31232, Abcam), GluA2 (1:1000, ab20673, Abcam), GluN1 (1:500, D65B7, CST), GluN2A (1:1000, ab124913, Abcam), GluN2B (1:1000, ab65783, Abcam), AKAP79/150 (1:200, sc‐6445, Santa Cruz).

After rinses by TBST, the membrane was incubated with horseradish peroxidase (HRP)‐conjugated secondary antibodies (Thermo Scientific, Rockford, IL) for 1.5 hours at room temperature. Then, after three repeated washes, membranes were immersed in enhanced chemiluminescence‐detecting substrate (SuperSignal West Pico; Pierce Chemical) and visualized with Micro Chemi (DNR Bio‐Imaging Systems, Jerusalem, Israel). The optical densities of the immunoblots were measured by NIH ImageJ software. All of the results were presented as a percentage of control following normalization.

2.5. Analysis of palmitoylation via acyl‐biotin exchange (ABE) method

ABE assay was performed as described in our previous studies.35, 36 Hippocampus slices were collected and homogenized with RIPA buffer (50 mM Tris‐HCl, PH 7.4, 1% NP‐40, 0.5% Na‐deoxycholate, 0.1% SDS, 150 mmol/L NaCl, 2 mmol/L EDTA, and 50 mmol/L NaF) including protease and phosphatase inhibitors (10 μL/mg tissue). Then, it was homogenized quickly by sonication, reacted 30 minutes on the ice, and then centrifuged at 12 000 g for 20 minutes at 4°C. The supernatant fraction was collected. All samples were mixed with 4 times volume of blocking buffer (1 vol 25% SDS solution and 9 vol of HEN buffer [250 mmol/L HEPES‐NaOH (pH 7.7), 1 mM EDTA, and 0.1 mmol/L neocuproine] adjusted to 20 mmol/L MMTS at 50°C for 30 minutes with gentle agitation to block free thiols. The samples were then mixed with 4 times volume of precold acetone, incubated at −20°C for 20 minutes, and centrifuged at 12 000 g for 20 minutes to remove the residual MMTS. Precipitates were suspended in RIPA buffer. The above steps were repeated for twice. At last, precipitates were redissolved in RIPA buffer and equally divided into two portions. One portion was incubated in 4 times volume of RIPA buffer containing 0.7 mmol/L HA to cleave thioester bonds and 1.0 mmol/L HPDP‐biotin to link biotin to newly exposed thiols. The other was incubated with the RIPA buffer with only HPDP‐biotin as a control. All samples were incubated with frequent vortexing in the dark place for 2‐3 hours at room temperature. The proteins were precipitated by 4 times volume of cold acetone and centrifuged at 12 000 g for 20 minutes to remove the remaining HPDP‐biotin and HA. After acetone removal, the proteins were resuspended in HENS buffer. The concentration of protein was measured via Coomassie blue protein‐binding assay (Nanjing Jiancheng Institute of Biological Engineering, Nanjing, China). The HRP‐streptavidin is used to detect the global palmitoylation via Western blot.

For detection of the palmitoylated proteins, the protein sample after ABE was divided into two portions. One portion was directly added into SDS‐PAGE sample loading buffer, to serve as “input.” The other portion was used to purify biotin‐labeled palmitoylated proteins with the streptavidin‐agarose, washed 3 times by RIPA buffer after repeated 10 times purification to assure bind completely, then eluted and denatured by SDS‐PAGE sample loading buffer at 95°C for 30 minutes. All of the samples were stored at −80°C before using for Western blot. The palmitoylated proteins are normalized to the input proteins (total proteins), which was internally controlled by actin.

2.6. Surface receptor cross‐linking assays with BS3

The membrane protein cross‐linking was performed as described in our previous studies.37, 38 Mice were decapitated after anesthesia with pentobarbital sodium (45 mg/kg, ip), and then, their brains were removed quickly. Coronal slices (350 μm) were cut with a vibratome (Leica VT 1000S, Solms, Germany) in ice‐cold artificial cerebrospinal fluid (aCSF) consisting of (mmol/L): (119.0 mmol/L NaCl, 3.5 KCl, 1.0 NaH2PO4, 1.3 MgSO4, 26.2 NaHCO3, 2.5 CaCl2, and 11.0 glucose (bubbled with 95% O2/5% CO2; pH 7.4). After NtBuHA treatment, the hippocampus was dissected and placed into Eppendorf tube containing ice‐cold aCSF with 2 mmol/L BS3 (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) for 30 minutes with gentle shaking. The reaction was terminated by quenching with 20 mmol/L glycine on ice for 10 minutes and then washed with aCSF for three times. Finally, it was homogenized with RIPA buffer (50 mmol/L Tris‐HCl, pH 7.4, 0.1% SDS, 150 mmol/L NaCl, 1% NP‐40, 0.5% Na‐deoxycholate, 2 mmol/L EDTA, and 50 mmol/L NaF, 10 μl/mg tissue) including protease inhibitor mixture and then centrifuged at 12 000 g for 15 minutes at 4°C. The supernatant fraction was collected and measured via Coomassie blue protein‐binding assay. Finally, the protein was denatured by SDS‐loading buffer at 95°C for 10 minutes and stored at −80°C before using for Western blot. The surface level of receptors was evaluated by the signal at molecular weight >300 kDa.

2.7. Co‐immunoprecipitation

Co‐immunoprecipitation was performed as described in our previous studies.39 Hippocampus slices were lysed with 0.2 mL extraction buffer (in mmol/L) (150 NaCl, 0.2% NP‐40 (v/v), 1 Na3VO4, 50 NaF, 3 Na‐pyrophosphate, 6 Na‐deoxycholate, 1% cocktail of protease inhibitor (v/v), 1% phosphatase inhibitor (v/v)), homogenized on the ice for 40 minutes, and then centrifuged at 12 000 g for 20 minutes at 4°C; the supernatant fraction (500 μg) was then incubated with 2 μg of PSD95 antibody overnight at 4°C with gentle shaking. The antibody‐antigen complexes were precipitated by incubating with 50 μL settled Protein A/G PLUS‐Agarose for 2‐4 hours at 4°C. The beads were collected by centrifugation at 4000 g for 3 minutes and washed three times with washing buffer (in mM) (1 EDTA, pH 7.5, 100 NaCl, 10 HEPES, 10% glycerol, and 0.1% Triton X‐100). Finally, proteins were released from the beads with 50 μl SDS‐loading buffer at 95°C for 5 minutes and then stored at −80°C before using for Western blot.

2.8. Electrophysiological recording

Electrophysiological recording was performed as described in our previous studies.40 Mice were decapitated after deep anesthesia with isoflurane and perfused with 40 mL ice‐cold oxygenated (95% O2 and 5% CO2) dissection buffer that consisted of (in mmol/L) 210 sucrose, 3.1 sodium pyruvate, 11.6 sodium L‐ascorbate, 1.0 NaH2PO4, 26.2 NaHCO3, 5.0 MgCl2, 20.0 glucose, PH 7.4 (300 mOsm), and then, their brains were removed quickly. Coronal slices (350 μm) were cut with a vibaratome (VT1000S, Leica, Wetzlar, Germany) in the ice‐cold oxygenated (95% O2 and 5% CO2) dissection buffer. In control group, the slices were incubated for 1.5 hours in an interface chamber containing aCSF that consisted of (in mM) (119.0 NaCl, 3.5 KCl, 1.0 NaH2PO4, 1.3 MgSO4, 26.2 NaHCO3, 2.5 CaCl2 and 11.0 glucose) at 28°C. In NtBuHA group, hippocampal slices were incubated in aCSF for 1 hour and then transferred into a chamber with aCSF containing NtBuHA and incubated for 30 minutes. Then, hippocampal slices were transferred into a submerged recording chamber and continuously bathed with aCSF at room temperature (25 ± 1°C). Patch electrodes (4‐6 MΩ resistance) filled with an intracellular solution contained the following (in mM): 122.5 Cs‐gluconate, 17.5 CsCl, 0.2 EGTA, 10.0 HEPES, 1.0 MgCl2, 4.0 Mg‐ATP, 0.3 Na‐GTP, and 5.0 QX314, pH 7.2 (280‐300 mOsm). The data were discarded if the series resistance changed by more than 20%. We used a Multiclamp 700B amplifier (Molecular Devices, Sunnyvale, CA, USA) under an upright Olympus microscope (BX51WIF, Olympus, Tokyo, Japan) to record CA1 pyramidal cells. AMPAR‐mediated miniature excitatory postsynaptic currents (mEPSCs) were recorded in the presence of tetrodotoxin (1 μmol/L) and bicuculline (20 μmol/L) and APV (50 μmol/L). All recordings were performed at a holding potential of −70 mV, filtered at 2 kHz, and sampled at 10 kHz using Digidata 1322A digitizer (Molecular Devices). Data were collected by the Clampex 10 software and analyzed by Mini Analysis Program (Synaptosoft, Decatur, GA, USA) with an amplitude threshold of 5 pA for mEPSC analysis.

2.9. Data statistical analysis

All of the analyses were performed by employing SPSS 18.0 software (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). Values were presented as mean ± SEM. All statistical tests were two‐tailed, and significance was assigned to P < 0.05. Sample size was chosen based on our past experience performing similar experiments. The data were evaluated by a two‐sided unpaired Student's t test, except for cumulative IEI probability was use K‐S test. The difference at the P < 0.05 was considered to be statistically significant.

3. RESULTS

3.1. NtBuHA exerts little effects on the expression of AMPAR, but reduces its surface delivery

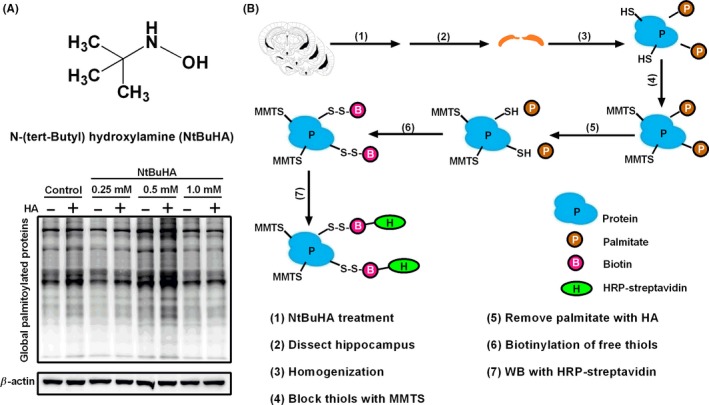

NtBuHA is a hydroxylamine derivative that has been recently identified as a mimic of thioesterase (Figure 1A). After HPDP‐biotin reaction, the global protein palmitoylation was detected by HRP‐streptavidin (Figure 1B). We found that incubation of hippocampal slices with NtBuHA (1.0 mmol/L) for 30 minutes significantly reduced global protein palmitoylation, indicating a rapid cleavage of palmitoylthioester (Figure 1C). Little changes induced were observed under the ‐HA conditions, indicating the effect of NtBuHA was mainly attributed to the palmitoylation. Thus, the concentration of NtBuHA used in other experiments was set at 1.0 mM.

Figure 1.

The structural formula of NtBuHA and NtBuHA (1.0 mmol/L) remarkably reduced global protein palmitoylation. A, Representative structure of NtBuHA. B, Global protein palmitoylation is detected in the WB with HRP‐streptavidin followed by acyl‐biotin exchange (ABE) protocol. C, The effect of NtBuHA (0, 0.25, 0.5, and 1.0 mmol/L) on global palmitoylated proteins in the hippocampus of mice in vitro. Incubation of hippocampal slices with NtBuHA (1.0 mmol/L) remarkably reduced global protein palmitoylation

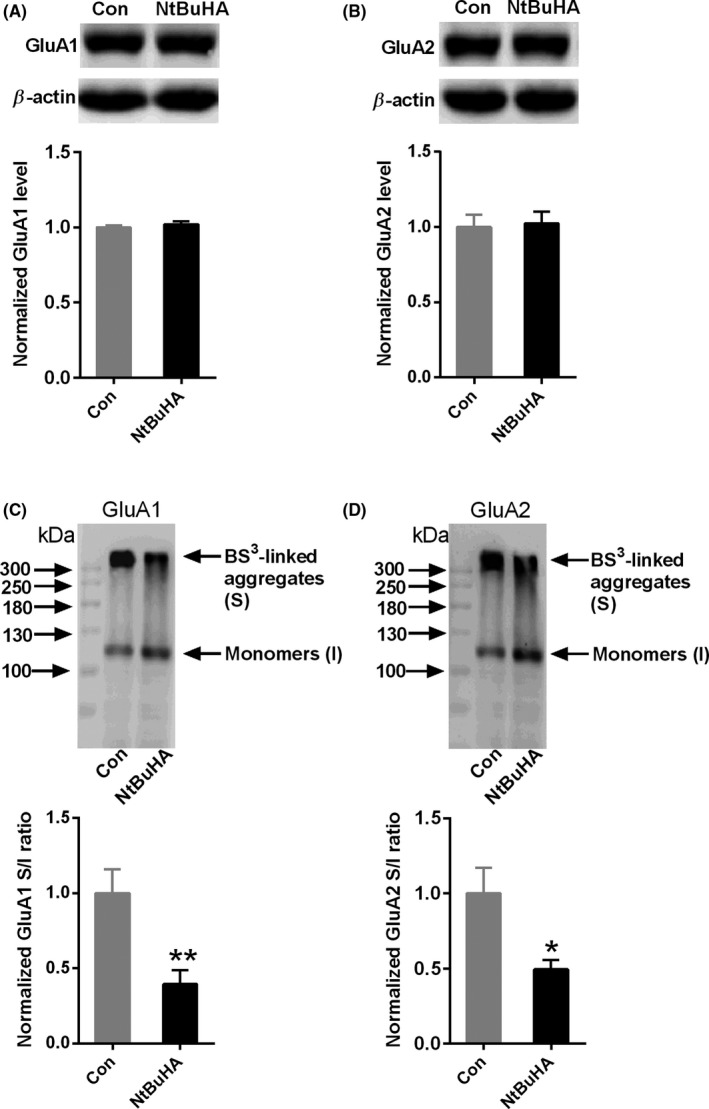

Firstly, we detected the total protein level of GluA1 and GluA2 in the hippocampus of mice exposure to NtBuHA incubation (Figure 2A,B). There were no obvious changes in the total protein level of AMPARs subunits GluA1 (NtBuHA: 1.02 ± 0.02 vs Control: 1.00 ± 0.01, n = 4, unpaired Student's t test, P > 0.05, Figure 2A) and GluA2 (NtBuHA: 1.02 ± 0.07 vs Control: 1.00 ± 0.08, n = 4, unpaired Student's t test, P > 0.05, Figure 2B). Then, we further tested the surface level of AMPAR subunits after NtBuHA incubation using BS3, a cytomembrane‐impermeable cross‐linker that specifically cross‐links the N‐terminus of surface cytomembrane proteins. The surface level of receptors was evaluated by the value of surface signals and intracellular signals. The protein signal at molecular weight >300 kDa was defined as surface signal. Compared to control group, the normalized surface content of both GluA1 (Figure 2C, NtBuHA: 0.39 ± 0.09 vs Control: 1.00 ± 0.15, n = 8, unpaired Student's t test, P < 0.01) and GluA2 (Figure 2D, NtBuHA: 0.49 ± 0.06 vs Control: 1.00 ± 0.16, n = 6, unpaired Student's t test, P < 0.05) was decreased in the hippocampus. Taken together, these results suggest that de‐palmitoylation reduced the surface delivery of AMPARs in the hippocampus.

Figure 2.

NtBuHA decreases the surface expression of AMPARs. A, B, Representative Western blots and statistical histogram showing NtBuHA (1.0 mmol/L) did not affect the total expression of GluA1(A) and GluA2 (B) (n = 4 mice for each group). C, Representative Western blots and statistical histogram showing NtBuHA (1.0 mmol/L) decreased the surface expression of GluA1 (n = 8 mice for each group). D, Representative Western blots and statistical histogram showing NtBuHA (1.0 mmol/L) decreased the surface expression of GluA2 (D) (n = 6 mice for each group). *P < 0.05 and **P < 0.01 vs control. Data are normalized to the untreated control group and presented as mean ± SEM. The data were evaluated by Student's t test. GluA1(S): surface GluA1; GluA1(I): Intracellular GluA1; GluA2(S): surface GluA2; GluA2(I): Intracellular GluA2. The data were evaluated by a two‐sided unpaired Student's t test

3.2. NtBuHA does not affect the surface expression of NMDAR

NMDAR is also important ionotropic receptor that contains an obligatory GluN1 subunit and different NR2 subunits. GluN1 subunit is essential for the function of NMDARs, while both GluN2A and GluN2B are the predominant NR2 subunits in the hippocampal neurons. Thus, we performed experiments to examine whether NtBuHA changes the total protein level and surface expression of NMDARs. As shown in Figure 3A‐C, incubation with NtBuHA (1.0 mmol/L) for 30 minutes did not influence the total protein level of GluN1 (NtBuHA: 1.05 ± 0.03 vs Control: 1.00 ± 0.04, n = 4, unpaired Student's t test, P > 0.05, Figure 3A), GluN2A (NtBuHA: 0.90 ± 0.16 vs Control: 1.00 ± 0.07, n = 4, unpaired Student's t test, P > 0.05, Figure 3B), and GluN2B (NtBuHA: 1.01 ± 0.03 vs Control: 1.00 ± 0.02, n = 4, unpaired Student's t test, P > 0.05, Figure 3C). Then, we asked whether NtBuHA affects the surface level of NMDARs. It was found that NtBuHA (1.0 mmol/L) did not change the surface level of GluN1 (NtBuHA: 0.97 ± 0.10 vs Control: 1.00 ± 0.10, n = 9, unpaired Student's t test, P > 0.05, Figure 3D), GluN2A (NtBuHA: 1.02 ± 0.15 vs Control: 1.00 ± 0.13, n = 9, unpaired Student's t test, P > 0.05, Figure 3E), and GluN2B (NtBuHA: 0.95 ± 0.08 vs Control: 1.00 ± 0.08, n = 9, unpaired Student's t test, P > 0.05, Figure 3F). In summary, these results suggest that de‐palmitoylation may not affect the surface expression of NMDARs.

Figure 3.

NtBuHA exerts little effect on the total expression and surface level of NMDARs. A‐C, Representative Western blots and a statistical histogram showing NtBuHA (1.0 mmol/L) did not affect the total expression of GluN1(A), GluN2A (B), and GluN2B (C) (n = 4 mice for each group). D‐F, Representative Western blots and a statistical histogram showing NtBuHA (1.0 mmol/L) did not affect the surface expression of GluN1 (D), GluN2A (E), and GluN2B (F) (n = 8 mice for each group). *P < 0.05 vs control. Data are normalized to the control group and presented as mean ± SEM. The data were evaluated by Student's t test. GluN1(S): surface GluN1; GluN1(I): Intracellular GluN1; GluN2A(S): surface GluN2A; GluN2A(I): Intracellular GluN2A; GluN2B(S): surface GluN2B; GluN2B(I): Intracellular GluN2B

3.3. NtBuHA decreases AMPAR‐mediated mEPSC in the hippocampal neurons

Considering that NtBuHA decreased the surface expression of GluA1 and GluA2, AMPARs function may be secondarily influenced. To further address this point, AMPAR‐mediated mEPSCs were monitored by whole‐cell recording on hippocampal slices. The frequency of mEPSCs mainly depends on the probability of release from presynaptic terminals,41 whereas the amplitude is dependent on several factors, including the amount of transmitter released, the postsynaptic sensitivity, and the driving force for the ions mediating the synaptic current.42 There was little difference of frequency between two groups (NtBuHA: 0.89 ± 0.14 Hz vs Control: 1.02 ± 0.16 Hz, n = 13‐14 neurons from 11 to 12 mice, unpaired Student's t test, P > 0.05, Figure 4A‐C). We found a significant reduction in the amplitude of mEPSC in NtBuHA‐treated hippocampal neurons (NtBuHA: 10.4 ± 0.46 vs Control: 13.58 ± 0.58, n = 13‐14 neurons from 11 to 12 mice, unpaired Student's t test, P < 0.01, Figure 4D‐E). These results suggest that de‐palmitoylation by NtBuHA decreases AMPAR‐mediated synaptic function via a postsynaptic mechanism in the hippocampus. We analyzed the kinetics of the mEPSC waveform between two groups using Mini Analysis 6.0(Synaptosoft, Decatur, GA, USA), and little difference were found in the mean rise time (3.22 ± 0.04 ms in the control group, 3.35 ± 0.04 in the NtBuHA group, n = 12 cells from 11 to 12 mice per group, unpaired Student's t test, P > 0.05, Figure 4F) and the mean decay time of mEPSCs (14.4 ± 0.25 ms in the control group, 15.07 ± 0.30 in the NtBuHA group, n = 12 cells from 11 to 12 mice per group, unpaired Student's t test, P > 0.05, Figure 4G).

Figure 4.

NtBuHA decreases the amplitude of AMPAR‐mediated mEPSC in the hippocampal neurons. A, Representative mEPSCs recording in the hippocampal pyramidal neurons. Scale bars, 20 pA and 1 s. B‐E, Cumulative probabilities and average mEPSCs frequencies and amplitudes from the control group and NtBuHA group and statistical histogram showing NtBuHA (1.0 mmol/L) decreased the mEPSCs amplitude of hippocampal pyramidal neurons, not frequency (n = 13‐14 cells from 11 to 12 mice). F, The mean rise time and (G) the mean decay time of mEPSCs were shown. No significant difference was observed in the kinetics of the mEPSC waveform between two groups (n = 12 cells from 11 to 12 mice per group). **P < 0.01 vs control. Data are normalized to the control group and presented as mean ± SEM. The data were evaluated by a two‐sided unpaired Student's t test

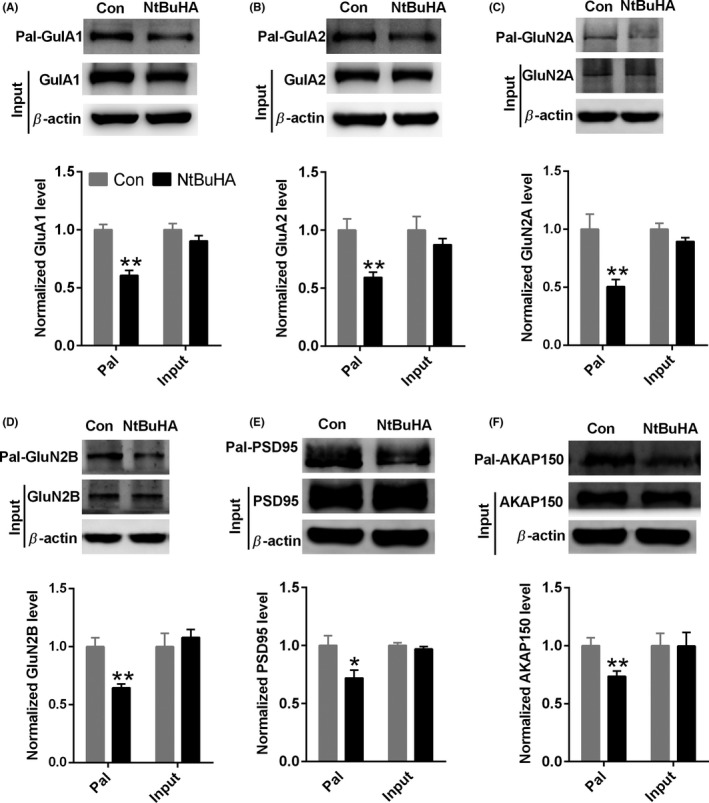

3.4. NtBuHA reduces the palmitoylation of PSD95 and AKAP79/150 in the hippocampus

Considering that palmitoylation of regulatory scaffold proteins of AMPAR plays a critical role in AMPAR synaptic targeting and stabilization, and NtBuHA decreased AMPAR‐mediated mEPSC, we hypothesized that NtBuHA may act via de‐palmitoylation of AMPAR regulatory scaffold proteins. PSD95 and AKAP79/150 are two key binding partners of AMPARs. We found that NtBuHA decreased the palmitoylation of PSD95 (NtBuHA: 0.72 ± 0.06 vs Control: 1.00 ± 0.08, n = 6‐8, unpaired Student's t test, P < 0.05, Figure 5E) and AKAP150 (NtBuHA: 0.73 ± 0.04 vs Control: 1.00 ± 0.06, n = 8, unpaired Student's t test, P < 0.01, Figure 5F), which may underlie the impairment of NtBuHA on AMPAR surface delivery and synaptic stabilization. Interestingly, NtBuHA also reduced the palmitoylation level of GluA1 (NtBuHA: 0.60 ± 0.04 vs Control: 1.00 ± 0.04, n = 7, unpaired Student's t test, P < 0.01, Figure 5A) and GluA2 (NtBuHA: 0.59 ± 0.04 vs Control: 1.00 ± 0.09, n = 7, unpaired Student's t test, P < 0.01, Figure 5B), which may help the AMPAR surface insertion from the Golgi apparatus. We also found that NtBuHA reduced the palmitoylation level of GluN2A (NtBuHA: 0.50 ± 0.06 vs Control: 1.00 ± 0.13, n = 6, unpaired Student's t test, P < 0.01, Figure 5C) and GluN2B (NtBuHA: 0.64 ± 0.03 vs Control: 1.00 ± 0.07, n = 6, unpaired Student's t test, P < 0.01, Figure 5D). Taken together, these data suggest that palmitoylation of regulatory scaffold proteins, not AMPAR itself, may be more critical in the regulation of AMPAR synaptic stability.

Figure 5.

NtBuHA decreases the palmitoylation of PSD95 and AKAP79/150 in the hippocampus. A, B, Representative Western blot and a statistical histogram showing NtBuHA (1.0 mmol/L) decreased the level of GluA1 (A) and GluA2 (B) palmitoylation (n = 7 mice for each group). C, D, Representative Western blot and a statistical histogram showing NtBuHA (1.0 mmol/L) decreased the level of GluN2A (C) and GluN2B (D) palmitoylation (n = 6 mice for each group). E, Representative Western blot and a statistical histogram showing NtBuHA (1.0 mmol/L) decreased the level of PSD95 palmitoylation (n = 6 ‐ 8 mice for each group). (F) Representative Western blot and a statistical histogram showing NtBuHA (1.0 mmol/L) decreased the level of AKAP150 palmitoylation (n = 8 mice for each group). *P < 0.05 and **P < 0.01 vs control. Data are normalized to control group and presented as mean ± SEM. The data were evaluated by a two‐sided unpaired Student's t test

3.5. NtBuHA preferentially reduces the association of PSD95 with AMPARs, not NMDARs

PSDs are a family of homologous scaffold protein distributed mainly in synapses. It has been reported that PSD95, the key postsynaptic scaffold protein in PSD family, associated with AMPARs or NMDARs only in its palmitoylated conformation.13 Thus, we hypothesized that de‐palmitoylation of PSD95 by NtBuHA may abolish the association of iGluRs with PSD95. NtBuHA did not affect the expression of AMPARs, NMDARs, Stargazin, and PSD95 (Input, Figure 6A). Co‐immunoprecipitation assay revealed that the association between GluA1 and PSD95 was decreased by NtBuHA (NtBuHA: 0.59 ± 0.09 vs Control: 1.00 ± 0.11, n = 3, unpaired Student's t test, P < 0.05, Figure 6B‐C). The interactions between GluA2 and PSD95 were also weakened (NtBuHA: 0.75 ± 0.07 vs Control: 1.00 ± 0.03, n = 4, unpaired Student's t test, P < 0.05, Figure 6B‐C). Although PSD95 also stabilizes NMDARs at synapses, we observed a same level of co‐immunoprecipitation between PSD95 and GluN1 (NtBuHA: 0.89 ± 0.01 vs Control: 1.00 ± 0.07, n = 4, unpaired Student's t test, P > 0.05, Figure 6B‐C), GluN2A (NtBuHA: 0.93 ± 0.07 vs Control: 1.00 ± 0.11, n = 3, unpaired Student's t test, P > 0.05, Figure 6B‐C), and GluN2B (NtBuHA: 1.0 ± 0.04 vs Control: 1.00 ± 0.08, n = 4, unpaired Student's t test, P > 0.05, Figure 6B‐C). Considering that AMPARs interact with PSD95 through stargazin, we examined the association between stargazing and PSD95 after NtBuHA treatment. Co‐immunoprecipitation assay revealed that NtBuHA significantly decreased the stargazing‐PSD95 association (NtBuHA: 0.74 ± 0.02 vs Control: 1.00 ± 0.07, n = 4, unpaired Student's t test, P < 0.05, Figure 6B‐C).Our results demonstrated that de‐palmitoylation selectively disturbed the association of PSD95 with AMPARs, not NMDARs, which was consistent with previous report.13

Figure 6.

NtBuHA preferentially reduces the interactions of PSD95 with AMPARs, not NMDARs. A, NtBuHA (1.0 mmol/L) did not change the expression of AMPARs, stargazin and NMDARs (Input). B, C, Representative Western blot and a statistical histogram showing NtBuHA (1.0 mmol/L) disrupted the interactions between PSD95 and AMPARs and stargazin, but not NMDARs (n = 3‐4 mice for each group). *P < 0.05 vs control. Data are normalized to control group and presented as mean ± SEM. The data were evaluated by a two‐sided unpaired Student's t test

4. DISCUSSION

Targeting palmitoylation signaling emerges as a novel therapeutic strategy for AMPAR regulation. Many pieces of evidence indicate that palmitoylation of receptor subunits or “scaffold” proteins produces opposite effects on AMPAR surface delivery, but much less is known about the effect of pharmacological de‐palmitoylation on AMPARs function. Here, we examined the effect of NtBuHA on iGluRs‐mediated synaptic transmission. We identified that NtBuHA reduced AMPAR surface expression and synaptic function in the hippocampus. These effects are mainly attributed to the de‐palmitoylation of their anchoring partners, not AMPARs themselves. Our findings endowed the NtBuHA with new pharmacological properties and reinforced its therapeutic values, not only in infantile neuronal ceroid lipofuscinosis (INCL), but also in other CNS disorders associated with aberrant glutamate signaling.

Many evidence indicates that aberrant palmitoylation signaling leads to pathology.19, 20, 21, 22, 23 Thus, pharmacological inhibition of palmitoylation may be potentially used as in the treatment of diseases associated with aberrant palmitoylation signaling, such as human cancer,19 INCL,22 brain insulin resistance,21 and cocaine addiction 24 As a hydroxylamine derivative that mimics palmitoyl‐protein thioesterase, the unique medical value of NtBuHA is to treat INCL (Batten disease), a devastating neurodegenerative lysosomal storage disease caused by mutations in the gene encoding palmitoyl‐protein thioesterase‐1. Here, we observed that palmitoylation‐deficient state initiated by NtBuHA preferentially inhibited AMPAR function. Interestingly, it has been reported that an increase in AMPA‐mediated neurotoxicity in granule cells and cerebellar slices happens in the mouse model of Batten disease.43 Pharmacological attenuation of AMPAR function improved motor skills and decreased the sensitivity of cerebellar granule cells to excitotoxicity in the INCL.44, 45 Considering the hyper‐palmitoylation state underlay INCL, the inhibition of AMPAR function by NtBuHA may be more significant, which would decrease AMPAR surface levels and thus neuronal death. Our findings reinforced the therapeutic value of NtBuHA in INCL. However, some recent findings argued against AMPAR changes in Batten disease and ascribed its synaptopathy to presynaptic changes, not aberrant levels of AMPARs.46, 47 Thus, further investigations are required. Considering the lower toxicity, the good blood‐brain barrier permeability, and the strong antioxidant activity, NtBuHA may also be used in the treatment of other CNS disorders, such as epilepsy, autism, ischemic brain injury, and cocaine addiction.

Our data reinforced the idea that the palmitoylated scaffold partners played a critical role in the AMPAR function using a specific chemical tool and indicated that palmitoylated scaffold partners, not palmitoylated receptor themselves, may be more sensitive as targets to be functional affected by pharmacological approaches. Palmitoylation of AMPARs and their partners produced the opposite effects on the surface AMPARs: the decrease in extra‐synaptic insertion of AMPARs from Golgi apparatus and the increase in the stabilization of AMPARs at synapses.10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15 At synapses, the de‐palmitoylation of PSD‐95 and AKAP79/150 by NtBuHA may reduce the number of AMPARs on the surface. In marked contrast, at Golgi apparatus, the de‐palmitoylation of AMPARs may increase their surface insertion. We found that nonselectively de‐palmitoylation by NtBuHA reduced AMPAR surface expression and synaptic function. This finding indicates that palmitoylated partners at synapses controlled AMPAR surface expression and stability. The low level of AMPARs at Golgi apparatus may mask the effect of de‐palmitoylation on AMPAR subunits. We tested the NMDAR palmitoylation state and found that NtBuHA also reduced NMDAR palmitoylation. However, NtBuHA exerted little effect on NMDAR surface expression. It should be noted that NMDARs directly interact with PSD95,48 whereas AMPARs interact with PSD95 through auxiliary subunits as stargazin.49 The stargazin‐PSD‐95 interaction plays a crucial role to trap and transiently stabilize diffusing AMPARs in the postsynaptic density.49 We further detected and found that de‐palmitoylation of PSD‐95 by NtBuHA significantly decreased its interactions with stargazin, but not NMDARs. Thus, selectively disrupting stargazing‐PSD95 associations might explain the differential functional outcome on both receptors upon NtBuHA. A series of proteins were also de‐palmitoylated by NtBuHA. Except for stargazing‐PSD95 association, other AMPAR‐interacting proteins that selectively affect the surface localization of AMPAR, but not NMDAR, such as activity‐regulated cytoskeletal‐associated protein (Arc)50 and AMPA receptor‐binding protein (ABP),51 may also serve as effectors of NtBuHA.

Our result that de‐palmitoylation by NtBuHA decreased the AMPAR function in the hippocampal slices was consistent with a previous study in cultured motor neurons that, 2‐BP, a widely used an irreversible nonselective inhibitor of palmitoyl acyltransferases, attenuates AMPAR‐activated Ca2+ signaling and cytotoxicity.29 However, in some other studies, 2‐BP exerted little effect on AMPARs palmitoylation and their surface expression in the normal animals. 2‐BP only blocks palmitate addition via acting on PATs, which may be enriched at Golgi apparatus. The low activity of PAT may limit the effect of 2‐BP under physiological condition. Under the pathological condition, the increased PAT activity may promote the effect of 2‐BP. Thus, it has been reported that 2‐BP reverts GluA1 hyper‐palmitoylation in the rats treated by high‐fat diet or cocaine exposure.21, 24 Different from 2‐BP, the direct de‐palmitoylation by NtBuHA is not dependent on PATs. Thus, both AMPARs and their partners were rapidly affected by NtBuHA. Further experiments are required to address this issue.

In summary, our study provides evidence that palmitoylation of scaffold partners is essential for the AMPARs function in the hippocampal neurons. These results suggest that total de‐palmitoylation of neuronal proteins may produce a preferential inhibitory effect on the AMPARs, which may be used in the treatment of CNS disorders associated with aberrant glutamate signaling.

CONFLICT OF INTERESTS

All the authors report no biomedical financial interests or potential conflict of interests.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This work was supported by grants from the Foundation for Innovative Research Groups of NSFC (No. 81721005), the National Basic Research Program of China (973 Program, No. 2014CB744601 to F.W.), National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 81471377 to F.W., No. 81773712 to P.F.W., No. 81473198 to J.G.C.) and the National Major Scientific Instrument and Equipment Development Projects (2013YQ03092306). Zhi‐Xuan Xia performed electrophysiological experiments, analyzed data, and wrote the study. Zu‐Cheng Shen performed most molecular experiments and analyzed data. Shao‐Qi Zhang performed BS3 surface receptor cross‐linking assay. Ji Wang, Tai‐Lei Nie, and Qiao Deng performed co‐immunoprecipitation. Jian‐Guo Chen, Fang Wang, and Peng‐Fei Wu supervised the project, designed the experiments, revised the manuscript, and supported funding acquisition.

Xia Z‐X, Shen Z‐C, Zhang S‐Q, et al. De‐palmitoylation by N‐(tert‐Butyl) hydroxylamine inhibits AMPAR‐mediated synaptic transmission via affecting receptor distribution in postsynaptic densities. CNS Neurosci Ther. 2019;25:187–199. 10.1111/cns.12996

Contributor Information

Fang Wang, Email: wangfangtj0322@163.com.

Peng‐Fei Wu, Email: wupengfeipharm@foxmail.com.

REFERENCES

- 1. Malinow R, Malenka RC. AMPA receptor trafficking and synaptic plasticity. Annu Rev Neurosci. 2002;25:103‐126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Anggono V, Huganir RL. Regulation of AMPA receptor trafficking and synaptic plasticity. Curr Opin Neurobiol. 2012;22:461‐469. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. van der Sluijs P, Hoogenraad CC. New insights in endosomal dynamics and AMPA receptor trafficking. Semin Cell Dev Biol. 2011;22:499‐505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Ehlers MD. Dendritic trafficking for neuronal growth and plasticity. Biochem Soc Trans. 2013;41:1365‐1382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Fukata Y, Fukata M. Protein palmitoylation in neuronal development and synaptic plasticity. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2010;11:161‐175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Han J, Wu P, Wang F, Chen J. S‐palmitoylation regulates AMPA receptors trafficking and function: a novel insight into synaptic regulation and therapeutics. Acta Pharm Sin B. 2015;5:1‐7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Mumby SM. Reversible palmitoylation of signaling proteins. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 1997;9:148‐154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Hayashi T, Rumbaugh G, Huganir RL. Differential regulation of AMPA receptor subunit trafficking by palmitoylation of two distinct sites. Neuron. 2005;47:709‐723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Lin DT, Makino Y, Sharma K, et al. Regulation of AMPA receptor extrasynaptic insertion by 4.1N, phosphorylation and palmitoylation. Nat Neurosci. 2009;12:879‐887. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Keith DJ, Sanderson JL, Gibson ES, et al. Palmitoylation of A‐kinase anchoring protein 79/150 regulates dendritic endosomal targeting and synaptic plasticity mechanisms. J Neurosci. 2012;32:7119‐7136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Woolfrey KM, Sanderson JL, Dell'Acqua ML. The palmitoyl acyltransferase DHHC2 regulates recycling endosome exocytosis and synaptic potentiation through palmitoylation of AKAP79/150. J Neurosci. 2015;35:442‐456. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. El‐Husseini Ael D, Schnell E, Dakoji S, et al. Synaptic strength regulated by palmitate cycling on PSD‐95. Cell. 2002;108:849‐863. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Jeyifous O, Lin EI, Chen X, et al. Palmitoylation regulates glutamate receptor distributions in postsynaptic densities through control of PSD95 conformation and orientation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2016;113:E8482‐E8491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. El‐Husseini AE, Craven SE, Chetkovich DM, et al. Dual palmitoylation of PSD‐95 mediates its vesiculotubular sorting, postsynaptic targeting, and ion channel clustering. J Cell Biol. 2000;148:159‐172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Vallejo D, Codocedo JF, Inestrosa NC. Posttranslational modifications regulate the postsynaptic localization of PSD‐95. Mol Neurobiol. 2017;54:1759‐1776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Hayashi T, Thomas GM, Huganir RL. Dual palmitoylation of NR2 subunits regulates NMDA receptor trafficking. Neuron. 2009;64:213‐226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Mattison HA, Hayashi T, Barria A. Palmitoylation at two cysteine clusters on the C‐terminus of GluN2A and GluN2B differentially control synaptic targeting of NMDA receptors. PLoS ONE. 2012;7:e49089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Lussier MP, Sanz‐Clemente A, Roche KW. Dynamic Regulation of N‐Methyl‐d‐aspartate (NMDA) and alpha‐Amino‐3‐hydroxy‐5‐methyl‐4‐isoxazolepropionic Acid (AMPA) Receptors by Posttranslational Modifications. J Biol Chem. 2015;290:28596‐28603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Yeste‐Velasco M, Linder ME, Lu YJ. Protein S‐palmitoylation and cancer. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2015;1856:107‐120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Hornemann T. Palmitoylation and depalmitoylation defects. J Inherit Metab Dis. 2015;38:179‐186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Spinelli M, Fusco S, Mainardi M, et al. Brain insulin resistance impairs hippocampal synaptic plasticity and memory by increasing GluA1 palmitoylation through FoxO3a. Nat Commun. 2017;8:2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Sarkar C, Chandra G, Peng S, et al. Neuroprotection and lifespan extension in Ppt1(−/−) mice by NtBuHA: therapeutic implications for INCL. Nat Neurosci. 2013;16:1608‐1617. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Bagh MB, Peng S, Chandra G, et al. Misrouting of v‐ATPase subunit V0a1 dysregulates lysosomal acidification in a neurodegenerative lysosomal storage disease model. Nat Commun. 2017;8:14612. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Van Dolah DK, Mao LM, Shaffer C, et al. Reversible palmitoylation regulates surface stability of AMPA receptors in the nucleus accumbens in response to cocaine in vivo. Biol Psychiatry. 2011;69:1035‐1042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Citraro R, Aiello R, Franco V, De Sarro G, Russo E. Targeting alpha‐amino‐3 ‐hydroxyl‐5‐methyl‐4‐isoxazole‐propionate receptors in epilepsy. Expert Opin Ther Targets. 2014;18:319‐334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Lee K, Goodman L, Fourie C, et al. AMPA receptors as therapeutic targets for neurological disorders. Adv Protein Chem Struct Biol. 2016;103:203‐261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Webb Y, Hermida‐Matsumoto L, Resh MD. Inhibition of protein palmitoylation, raft localization, and T cell signaling by 2‐bromopalmitate and polyunsaturated fatty acids. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:261‐270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Jones ML, Collins MO, Goulding D, Choudhary JS, Rayner JC. Analysis of protein palmitoylation reveals a pervasive role in Plasmodium development and pathogenesis. Cell Host Microbe. 2012;12:246‐258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Krishnamurthy K, Mehta B, Singh M, Tewari BP, Joshi PG, Joshi NB. Depalmitoylation preferentially downregulates AMPA induced Ca2 + signaling and neurotoxicity in motor neurons. Brain Res. 2013;1529:143‐153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Leong WF, Zhou T, Lim GL, Li B. Protein palmitoylation regulates osteoblast differentiation through BMP‐induced osterix expression. PLoS ONE. 2009;4:e4135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Fukata M, Fukata Y, Adesnik H, Nicoll RA, Bredt DS. Identification of PSD‐95 palmitoylating enzymes. Neuron. 2004;44:987‐996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Davda D, El Azzouny MA, Tom CT, et al. Profiling targets of the irreversible palmitoylation inhibitor 2‐bromopalmitate. ACS Chem Biol. 2013;8:1912‐1917. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Drisdel RC, Alexander JK, Sayeed A, Green WN. Assays of protein palmitoylation. Methods. 2006;40:127‐134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Yu DF, Shen ZC, Wu PF, et al. HFS‐triggered AMPK activation phosphorylates GSK3beta and induces E‐LTP in rat hippocampus in vivo. CNS Neurosci Ther. 2016;22:525‐531. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Han J, Zhang H, Wang S, et al. Potentiation of surface stability of AMPA receptors by sulfhydryl compounds: a redox‐independent effect by disrupting palmitoylation. Neurochem Res. 2016;41:2890‐2903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Li YL, Wu PF, Chen JG, et al. Activity‐dependent sulfhydration signal controls n‐methyl‐D‐aspartate subtype glutamate receptor‐dependent synaptic plasticity via increasing d‐serine availability. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2017;27:398‐414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Li YL, Zhou J, Zhang H, et al. Hydrogen sulfide promotes surface insertion of hippocampal AMPA receptor GluR1 subunit via phosphorylating at serine‐831/serine‐845 Sites through a sulfhydration‐dependent mechanism. CNS Neurosci Ther. 2016;22:789‐798. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Mao LM, Wang W, Chu XP, et al. Stability of surface NMDA receptors controls synaptic and behavioral adaptations to amphetamine. Nat Neurosci. 2009;12:602‐610. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Lu HF, Wu PF, Yang YJ, et al. Interactions between N‐ethylmaleimide‐sensitive factor and GluR2 in the nucleus accumbens contribute to the expression of locomotor sensitization to cocaine. J Neurosci. 2014;34:3493‐3508. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Li MX, Zheng HL, Luo Y, et al. Gene deficiency and pharmacological inhibition of caspase‐1 confers resilience to chronic social defeat stress via regulating the stability of surface AMPARs. Mol Psychiatry. 2017;23:556‐568. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Fatt P, Katz B. Spontaneous subthreshold activity at motor nerve endings. J Physiol. 1952;117:109‐128. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Van der Kloot W. The regulation of quantal size. Prog Neurobiol. 1991;36:93‐130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Kovács AD, Weimer JM, Pearce DA. Selectively increased sensitivity of cerebellar granule cellsto AMPA receptor‐mediated excitotoxicity in a mouse model of Batten disease. Neurobiol Dis. 2006;22:575‐585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Kovacs AD, Pearce DA. Attenuation of AMPA receptor activity improves motor skills in a mouse model of juvenile Batten disease. Exp Neurol. 2008;209:288‐291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Kovacs AD, Saje A, Wong A, et al. Temporary inhibition of AMPA receptors induces a prolonged improvement of motor performance in a mouse model of juvenile Batten disease. Neuropharmacology. 2011;60:405‐409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Grünewald B, Lange MD, Werner C, et al. Defective synaptic transmission causes disease signs in a mouse model of juvenile neuronal ceroid lipofuscinosis. Elife. 2017;6:pii: e28685. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Studniarczyk D, Needham EL, Mitchison HM, Farrant M, Cull‐ Candy SG. Altered cerebellar short‐term plasticity but no change in postsynaptic AMPA‐type glutamate receptors in a mouse model of juvenile batten disease. eNeuro 2018;5: pii: ENEURO.0387‐17.2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Hirao K, Hata Y, Ide N, et al. A novel multiple PDZ domain‐containing molecule interacting with N‐methyl‐D‐aspartate receptors and neuronal cell adhesion proteins. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:21105‐21110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Bats C, Groc L, Choquet D. The interaction between Stargazin and PSD‐95 regulates AMPA receptor surface trafficking. Neuron. 2007;53:719‐734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Barylko B, Wilkerson JR, Cavalier SH, et al. Palmitoylation and membrane binding of Arc/Arg3.1: a potential role in synaptic depression. Biochemistry. 2018;57:520‐524. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. DeSouza S, Fu J, States BA, Ziff EB. Differential palmitoylation directs the AMPA receptor‐binding protein ABP to spines or to intracellular clusters. J Neurosci. 2002;22:3493‐3503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]