Summary

Aim

Exploration of the mechanism of spinal cord degeneration may be the key to treatment of spinal cord injury (SCI). This study aimed to investigate the degeneration of white matter and gray matter and pathological mechanism in canine after SCI.

Methods

Diffusion tensor imaging (DTI) was performed on canine models with normal (n = 5) and injured (n = 7) spinal cords using a 3.0T MRI scanner at precontusion and 3 hours, 24 hours, 6 weeks, and 12 weeks postcontusion. The tissue sections were stained using H&E and immunohistochemistry.

Results

For white matter, fractional anisotropy (FA) values significantly decreased in lesion epicenter, caudal segment 1 cm away from epicenter, and caudal segment 2 cm away from epicenter (P = 0.003, P = 0.004, and P = 0.013, respectively) after SCI. Apparent diffusion coefficient (ADC) values were initially decreased and then increased in lesion epicenter and caudal segment 1 cm away from epicenter (P < 0.001 and P = 0.010, respectively). There are no significant changes in FA and ADC values in rostral segments (P > 0.05). For gray matter, ADC values decreased initially and then increased in lesion epicenter (P < 0.001), and overall trend decreased in caudal segment 1 cm away from epicenter (P = 0.039). FA values did not change significantly (P > 0.05). Pathological examination confirmed the dynamic changes of DTI parameters.

Conclusion

Diffusion tensor imaging is more sensitive to degeneration of white matter than gray matter, and the white matter degeneration may be not symmetrical which meant the caudal degradation appeared to be more severe than the rostral one.

Keywords: canine model, diffusion tensor imaging, gray matter, pathological degeneration, spinal cord injury, white matter

1. INTRODUCTION

Human mature central nervous system (CNS) fails to regenerate spontaneously after severe damage. Similarly, injured spinal cord cannot be effectively repaired currently and patients with complete spinal cord injury (SCI) can only be lifelong paralysis.1 Inhibition of spinal cord degeneration and promotion of nerve regeneration remain the most crucial world‐class problems. Edema, hemorrhage, various inflammatory reactions, and glial scar formation after SCI play a distinct role in axonal regeneration.2, 3, 4 Axon demyelination and necrosis led by Wallerian degeneration can occur rostrally to the lesion in the ascending tracts and caudally to the lesion in the descending tracts.5 Exploring the dynamic degeneration mechanisms of SCI underlying axon regeneration failure acts as fundamental processes in improving CNS repair after traumatic injury, stroke, or degenerative diseases.2, 6, 7

Based on MRI, diffusion tensor imaging (DTI) has been widely used in clinical as well as scientific research in recent years and is considered as an advanced imaging technology.5 It is a sensitive and noninvasive detection method that the microstructure of fiber bundles can not only be visualized, but also can be presented quantitatively.8 Studies have shown that the fractional anisotropy (FA) value was sensitive to axonal degeneration and demonstrated a positive correlation with myelin integrity, fiber densification, and parallelism.5, 9, 10 Apparent diffusion coefficient (ADC) value is a parameter that overlays all the factors that affect the movement of water molecules, reflecting the displacement intensity of water molecules in the direction of the diffusion sensitive gradient, and the ADC value was often decreased in acute phase and increased in subacute and chronic phases.11 Mean diffusivity (MD) and radial diffusivity (RD) values demonstrated considerable significance in studying the pathological changes of SCI. In addition, the canine model of SCI is considered as an ideal transformation model from rodents to humans,12 and our team has also made some progress in making canine SCI models. To the best of our knowledge, studies on retrograde and anterograde degeneration after SCI have been limited to rodents,13 and only white matter was explored and the duration of which remains relatively short.

We hypothesized that DTI could exactly explore the dynamic changes of white matter and gray matter injuries from the lesion epicenter to rostral and caudal levels with an extended duration after SCI. Hence, the purpose of this study was to investigate the retrograde and anterograde degeneration of white and gray matter using DTI and pathological mechanism in canine after SCI.

2. MATERIALS AND METHODS

2.1. Animals and ethic

Twelve healthy female (10 ± 0.5 kg, 2 ± 0.5 years) Beagles (Beijing Marshall Biotechnology Co., Ltd, Beijing, China) were included and allowed access to food and water ad libitum. Five animals underwent laminotomy as controls, whereas seven animals were made into SCI models. The study was conducted according to the ethical rules of Animal Experiments and Experimental Animal Welfare Committee.

2.2. Spinal cord injury

Animals were anesthetized via intraperitoneal administration of 2.5% pentobarbital sodium (Item NO: P11011; Merck: Darmstadt, Germany) with a dose of 125 mg/kg, and an intramuscular administration of xylazine hydrochloride (Dunhua Shengda Animal Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd: Dunhua, Jilin Province, China) 0.1 mL/kg. Retention catheterization was managed using sterile urethral catheter (8Fr, Zhanjiang Star Enterprise Co., Ltd., Guangdong Sheng, China). A rectangular skin area (30 cm × 15 cm) centered on the 10th thoracic vertebra was marked. Vertebral laminae of T10 and part of T9 and T11 vertebra were uncovered to expose a 1‐cm‐long spinal cord. Five animals (underwent laminotomy without SCI) were considered as controls, and seven animals underwent SCI following the previously described method.14

2.3. Postoperative nursing

Hydrogen peroxide and betadine were used to clean the surgical site and covered using sterile gauze. After the dogs regained consciousness, they were administered orally with pregabalin (25 mg/kg, Pfizer Manufacturing Deutschland GmbH, Betriebsstatte Freiburg, Germany) every day for 1 week. All the dogs continued to receive sodium chloride injection (25 mL/kg) intravenously for 3 days postinjury. The antibiotic agent cefoxitin sodium (50 mg/kg) was administered via intramuscular injection daily for seven consecutive days. The details were described previously.14

2.4. MRI

The experiments were performed using Siemens 3.0 T Prisma fit MRI scanner (Siemens Magnetom, Berlin, Germany) with a 32 Ch Spinal cord coil. The animals were placed in the supine position under anesthesia during the entire MRI scan with a mixture of pentobarbital sodium and xylazine hydrochloride. Fat‐saturated sagittal T2‐SPACE sequences were acquired with an in‐plane resolution of 0.84 mm × 0.84 mm (TR/TE = 1500/142 ms) with the slice thickness of 0.75 mm, and with an ACQ matrix size of 320 × 320. Axial diffusion imaging was based on single‐shot EPI sequence using the following parameters: TR/TE of 7300/83 ms, slice thickness of 4 mm with a 0.8 mm gap, in‐plane resolution of 1.3 mm × 1.3 mm, 30 directions, b values of 800, NEX = 2, and extra 4 b0 images. MRI examinations were performed at precontusion and at 3 hours, 24 hours, 6 weeks, and 12 weeks postinjury in both controls and animals with SCI.

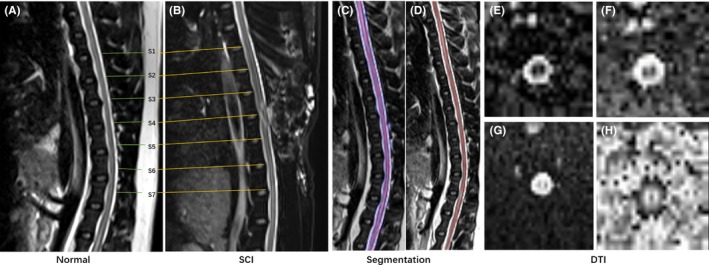

2.5. DTI preprocessing

The center line of white matter was defined on T2W imaging using the custom software. DTI preprocessing pipeline included: (i) registration to T2W images; (ii) correction for eddy current; and (iii) calculation of DTI parameters, FA, ADC, MD, and RD. The injury epicenter was T10, the spinal cord was defined as seven regions of interest (ROIs) from the epicenter to rostral and caudal levels at intervals of 1 cm and designated as sites 1‐7 from rostral to caudal level. Site 4 (S4) corresponds to the epicenter and other sites (S1, S2, S3, S5, S6, and S7) corresponds to nonepicenter. The parameters of the seven sites were analyzed in the study (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Typical example of seven region of interests (ROIs) of normal and SCI groups (A,B). The segmentation example of white matter and gray matter (C,D). The typical DTI images (E,F,G,H)

2.6. Histopathology and immunohistochemistry

Following 3 months of postinjury MRI, animals were anesthetized and surgery was performed as described previously. To maintain consistent sampling, each spinal cord was transected at the rostral T9 spinal root and a 3‐cm spinal cord segment was immediately dissected and postfixed in 4% paraformaldehyde (PFA) at 4°C.8 The injured spinal cord was transected to about 5‐mm segments at the center of injury and the 1 cm rostral and caudal distance to the epicenter, which were juxtaposed with the rostral ends of each cord and were evenly aligned into plastic cryomolds with paraffin embedding. The spinal cords were cut into 3‐μm transverse sections except that the two spinal lesions that were cut longitudinally. The spinal cord sections were mounted on gelatinized slides and stained with hematoxylin and eosin (HE) for histopathological and morphological observation. Immunohistochemical analysis of the spinal cord lesion was conducted by incubating a few longitudinal and transversal sections overnight at 4°C with primary antibodies against NF‐H (dilution 1:100, Santa, USA) and mouse monoclonal anti‐GFAP (1:200, Abcam, Cambridge, UK). After washing with 0.2% phosphate‐buffered saline for 5 minutes, the sections were incubated with conjugated secondary antibody immunoCruz™ goat ABC staining system (Santa) for 2 hours at room temperature, immediately followed by 1‐2 drops of permanent mounting medium, and covered with a glass coverslip.4, 15 Finally, all the sections were imaged with HistoFAXS software (Tissue Gnostics, Vienna, Austria) at a magnification of 20×. (Supplementary Table S1).

For quantitative analysis of scarring, we selected five ROIs on each slice and given cytoplasmic stained score by ImageJ software16 (version 1.48; National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD, USA) on immunohistochemistry‐stained histopathological images, which was considered to represent scarring. We took highly positive and positive scores for calculation.

2.7. Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed with SPSS 21.0 (SPSS Inc, Chicago, IL, USA). The normal distribution of the data was tested using Shapiro‐Wilk normality tests. One‐way ANOVA was used to analyze the time effect on the parameters of each site followed by Tukey’s multiple comparisons test. Two‐way ANOVA was used to analyze the difference between control and SCI group on the parameters of each site. Paired t test was used to analyze the difference of pathological changes between control and the injured group. This study is multifactor and longitudinal observation. So the mixed‐effects modeling was used to analyze the time and site factors and the interaction of it on the DTI parameters. The DTI parameters were dependent variable, and the time and site were independent variables. The data were expressed as mean ± standard deviation (SD). Values of P < 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

3. RESULTS

3.1. Spinal cord contusion model

Following SCI, rapid convulsions were seen in the tails of the dogs. The bilateral hind limbs showed flaccid paralysis after dissipation of the effect of anesthesia. The gait and postural reactions remained scoreless, and nociception in each limb showed one point within 2 days, suggesting in the successful creation of the model.14

3.2. Changes of DTI parameters in white matter and gray matter

3.2.1. White matter

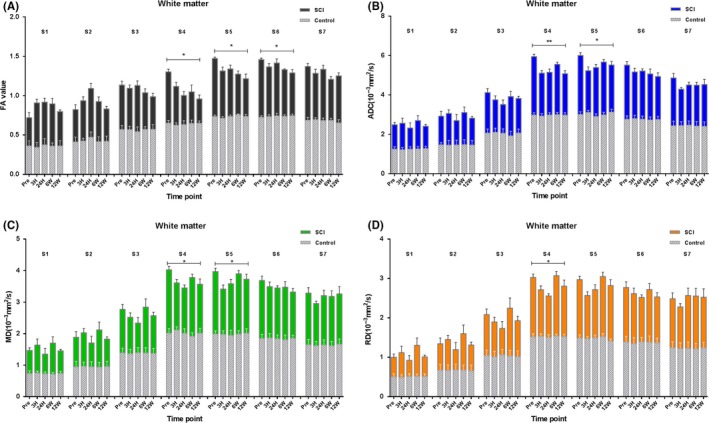

Compared with control, the general trend of the FA value at the injury epicenter after SCI was gradually decreased. Figure 2A showed that the FA values of the nonepicenter also showed a corresponding declination. Two‐way ANOVA of each site showed significant changes in S4, S5, and S6 (P = 0.003, P = 0.004, and P = 0.013, respectively). S1, S2, S3, and S7 also demonstrated corresponding changes, but showed no statistical differences (P > 0.05). The mixed‐effects modeling analysis showed that the site location and time significantly influenced the FA parameters (P < 0.001 and P < 0.001). There was no interaction observed between location and time (P = 0.413). The fixed‐effects results of mixed‐effects model of white matter FA values were listed in Table 1. The estimates of fixed effects of the FA values in white matter were described in Table 2. There were no significant changes in all the corresponding sites of the control group (P > 0.05).

Figure 2.

Comparison of DTI parameters between control and SCI group at all time points of seven sites along the white matter as analyzed by two‐way ANOVA. The histogram below was the control group (N = 5), and the above histogram was the SCI group (N = 7). An error probability of 0.05 (P) was used as the significance level. All parameters are represented as mean ± standard deviation (SD).**P < 0.001, *P < 0.05, S1‐S7, site1‐site7

Table 1.

The fixed‐effects results of mixed‐effects model of white matter

| DTI | Source | F | df | t | N | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| FA | Intercept | 330.936 | 98.599 | 18.192 | 7 | <0.001 |

| Site | 19.580 | 236.000 | 4.425 | 7 | <0.001 | |

| Time | 25.397 | 236.000 | −5.040 | 7 | <0.001 | |

| Site × time | 0.672 | 237.000 | −0.820 | 7 | 0.413 | |

| ADC | Intercept | 141.083 | 212.389 | 11.878 | 7 | <0.001 |

| Site | 152.495 | 269.680 | 12.349 | 7 | <0.001 | |

| Time | 8.010 | 269.680 | −2.830 | 7 | 0.005 | |

| Site × time | 4.671 | 312.428 | −2.161 | 7 | 0.031 | |

| MD | Intercept | 21.239 | 281.299 | 4.609 | 7 | <0.001 |

| Site | 37.582 | 157.478 | 6.130 | 7 | <0.001 | |

| Time | 0.263 | 287.285 | 0.512 | 7 | 0.609 | |

| Site × time | 1.064 | 287.285 | −1.032 | 7 | 0.303 | |

| RD | Intercept | 11.155 | 268.735 | 3.340 | 7 | 0.001 |

| Site | 25.002 | 268.735 | 5.000 | 7 | <0.001 | |

| Time | 0.460 | 189.906 | 0.678 | 7 | 0.498 | |

| Site × time | 0.307 | 268.735 | −0.554 | 7 | 0.580 |

Table 2.

The estimates of fixed effects and random effects of white matter

| DTI | Effects | Estimated coefficient | SE | 95% Confidence interval | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower endpoint | Upper endpoint | ||||

| FA | Fixed effects | ||||

| Intercept | 0.562968** | 0.030947 | 0.501560 | 0.624376 | |

| Site | 0.020843** | 0.004710 | 0.011563 | 0.030122 | |

| Time | −0.033570** | 0.006661 | −0.046694 | −0.020447 | |

| Site × Time | −0.000963 | 0.001175 | −0.003278 | 0.001352 | |

| ADC | Fixed effects | ||||

| Intercept | 0.001340** | 0.000113 | 0.001118 | 0.001560 | |

| Site | 0.000210** | 0.000017 | 0.000177 | 0.000244 | |

| Time | −0.000068* | 0.000024 | −0.000116 | −0.000021 | |

| Site × Time | −0.000026 | 0.000012 | −0.000050 | −0.000002 | |

| MD | Fixed effects | ||||

| Intercept | 0.000652** | 0.000142 | 0.000374 | 0.000931 | |

| Site | 0.000195** | 0.000032 | 0.000132 | 0.000257 | |

| Time | 0.000022 | 0.000043 | −0.000063 | 0.000108 | |

| Site × Time | −0.000010 | 0.000010 | −0.000029 | 0.000009 | |

| RD | Fixed effects | ||||

| Intercept | 0.000442* | 0.000132 | 0.000182 | 0.000703 | |

| Site | 0.000148** | 0.000030 | 0.000090 | 0.000206 | |

| Time | 0.000027 | 0.000040 | −0.000052 | 0.000107 | |

| Site × Time | −0.000005 | 0.000009 | −0.000023 | 0.000013 | |

*P < 0.05

**P < 0.001.

Compared with control, the general trend of the ADC value at the injury epicenter after SCI firstly decreased and then increased. Figure 2B showed that the ADC values of nonepicenter also demonstrated similar changes, and the two‐way ANOVA of each site showed significant changes in S4 and S5 (P < 0.001 and P = 0.010, respectively). The S3, which was symmetrical with S5 and S1, S2, S6, and S7 had similar changes as S4, but showed no statistical differences (P > 0.05). The mixed‐effects modeling analysis showed that the site location and time significantly influenced the ADC parameters (P < 0.001 and P = 0.005). There was a significant interaction observed between location and time (P = 0.031). The fixed‐effects results of mixed‐effects model of white matter ADC values were also listed in Table 1. The estimates of fixed effects of the ADC values in white matter were also described in Table 2. The dynamic changes of MD and RD parameters of whiter matter were similar as ADC and depicted in Figure 2C,D. There were no significant changes in all the corresponding sites of the control group (P > 0.05).

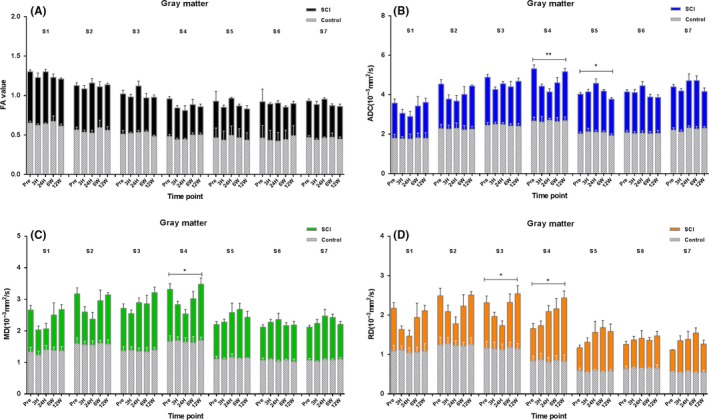

3.2.2. Gray matter

Compared with control, the Figure 3A showed that the FA values of all sites after SCI demonstrated corresponding declination, and the two‐way ANOVA of each site showed no significant changes in the sites (P > 0.05). But the mixed‐effects modeling analysis showed that the site location and time influenced the FA parameters significantly (P < 0.001 and P = 0.012). There was no interaction observed between location and time (P = 0.597). The fixed‐effects results of mixed‐effects model of gray matter FA values were listed in Table 3. The estimates of fixed effects of the FA values in gray matter were described in Table 4. There were no significant changes in all the corresponding sites of the control group (P > 0.05).

Figure 3.

Comparison of DTI parameters between control and SCI group at all time points of seven sites along the gray matter as analyzed by two‐way ANOVA. The histogram below was the control group (N = 5), and the histogram above was the SCI group (N = 7). An error probability of 0.05 (P) was used as the significance level. All parameters are represented as mean ± standard deviation (SD).**P < 0.001, *P < 0.05, S1‐S7, site1‐site7

Table 3.

The fixed‐effects results of mixed‐effects model of gray matter

| DTI | Source | F | df | t | N | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| FA | Intercept | 831.009 | 69.686 | 28.827 | 7 | <0.001 |

| Site | 71.946 | 234.735 | −8.482 | 7 | <0.001 | |

| Time | 7.118 | 31.169 | −2.668 | 7 | 0.012 | |

| Site × Time | 0.280 | 235.000 | −0.529 | 7 | 0.597 | |

| ADC | Intercept | 212.989 | 237.212 | 14.594 | 7 | <0.001 |

| Site | 17.785 | 237.212 | 4.217 | 7 | <0.001 | |

| Time | 0.176 | 406.116 | −0.419 | 7 | 0.675 | |

| Site × Time | 0.983 | 236.368 | −0.991 | 7 | 0.332 | |

| MD | Intercept | 136.187 | 382.947 | 11.670 | 7 | <0.001 |

| Site | 0.318 | 237.132 | 0.564 | 7 | 0.573 | |

| Time | 5.565 | 153.246 | 2.359 | 7 | 0.020 | |

| Site × Time | 3.568 | 287.285 | 1.889 | 7 | 1.000 | |

| RD | Intercept | 69.691 | 400.307 | 8.348 | 7 | <0.001 |

| Site | 2.499 | 237.011 | −1.581 | 7 | 0.115 | |

| Time | 14.478 | 125.531 | 3.805 | 7 | <0.001 | |

| Site × Time | 1.844 | 840.152 | 1.358 | 7 | 0.175 |

Table 4.

The estimates of fixed effects and random effects of gray matter

| DTI | Effects | Estimated coefficient | SE | 95% Confidence interval | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower endpoint | Upper endpoint | ||||

| FA | Fixed effects | ||||

| Intercept | 0.643740** | 0.022331 | 0.599199 | 0.688282 | |

| Site | −0.029432** | 0.003470 | −0.036268 | −0.022596 | |

| Time | −0.013341** | 0.005000 | −0.023537 | −0.003145 | |

| Site × Time | −0.001302 | 0.002463 | −0.006154 | 0.003549 | |

| ADC | Fixed effects | ||||

| Intercept | 0.001549** | 0.000199 | 0.001157 | 0.001941 | |

| Site | 0.000120** | 0.000045 | 0.000032 | 0.000208 | |

| Time | 0.000040 | 0.000063 | −0.000084 | 0.000163 | |

| Site × Time | −0.000013 | 0.000013 | −0.000040 | 0.000013 | |

| MD | Fixed effects | ||||

| Intercept | 0.001082** | 0.000093 | 0.000900 | 0.001264 | |

| Site | 0.000009 | 0.000016 | −0.000023 | 0.000041 | |

| Time | 0.000051* | 0.000022 | 0.000008 | 0.000094 | |

| Site × Time | 0.000007 | 0.000004 | 0.000007 | 0.000007 | |

| RD | Fixed effects | ||||

| Intercept | 0.000768** | 0.000092 | 0.000587 | 0.000949 | |

| Site | −0.000025 | 0.000016 | −0.000055 | 0.000006 | |

| Time | 0.000080** | 0.000021 | 0.000038 | 0.000122 | |

| Site × Time | 0.000005 | 0.000004 | −0.000002 | 0.000012 | |

*P < 0.05

**P < 0.001.

Compared with control, the ADC values of the injury epicenter after SCI firstly decreased and then increased. Figure 3B showed that the ADC values of nonepicenter also appeared similar changes, and the two‐way ANOVA of each site showed significant changes in S4 and S5 (P < 0.001 and P = 0.039, respectively). The S1, S2, S3, S6, and S7 demonstrated similar changes with S4, but showed no statistical differences (P > 0.05). The mixed‐effects modeling analysis showed that the site location influenced ADC parameters significantly (P < 0.001). Time had no significant effect on them (P = 0.675), and there was no interaction between location and time (P = 0.332). The fixed‐effects results of mixed‐effects model of gray matter ADC values were also listed in Table 3. The estimates of fixed effects of the ADC values in gray matter were also described in Table 4. The dynamic changes of MD and RD parameters of gray matter were similar as ADC and depicted in Figure 3C,D. There were no significant changes in all the corresponding sites of the control group (P > 0.05).

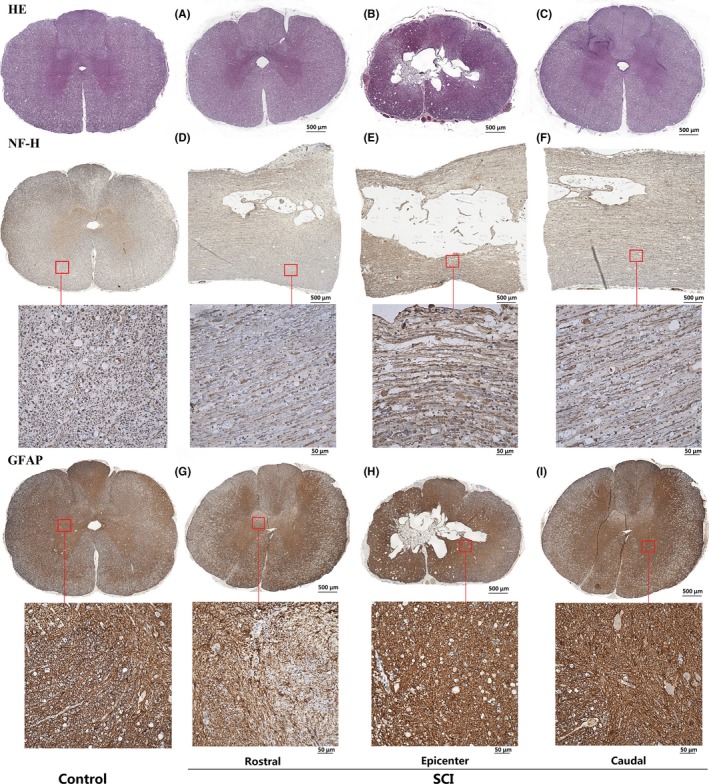

3.3. Histopathology

At 12 weeks after SCI, histological analyses of the postmortem spinal cords were performed to verify the DTI dynamic changes of white matter and gray matter and explore the degeneration and repair of fiber bundles and glial cells after spinal cord contusion. By HE staining at the rostral level 1 cm away from epicenter (Figure 4A), the shape of the white matter and gray matter appeared irregular and the boundaries became unclear. Figure 4B showed that the gray matter part of the epicenter demonstrated the formation of an amorphous cavity, spreading it to the white matter, and was filled with many irregular vacuoles. At the caudal level 1 cm away from the epicenter (Figure 4C), gray matter and white matter also showed irregular degeneration, while the degradation degree of caudal level was more severe than the rostral one, and the scar was formed at the posterior horn of gray matter, showing deformity at the boundary.

Figure 4.

Representation of HE and immunohistochemistry staining in control and SCI groups. A, The shape becomes irregular and the boundaries become unclear. B, Amorphous cavity formation and spreads to the white matter. C, The scar formed at the posterior horn of gray matter, and the boundary had a deformity. D,E,F, The axons of the white matter fiber bundle were degenerated and became messy. G,H,I, The darker reactive glial scar almost occupied most of the spinal cord area in the epicenter. At the rostral and caudal levels, the reactive glial cells proliferated and went beyond the gray matter area. Based on the figures from Liu et al14

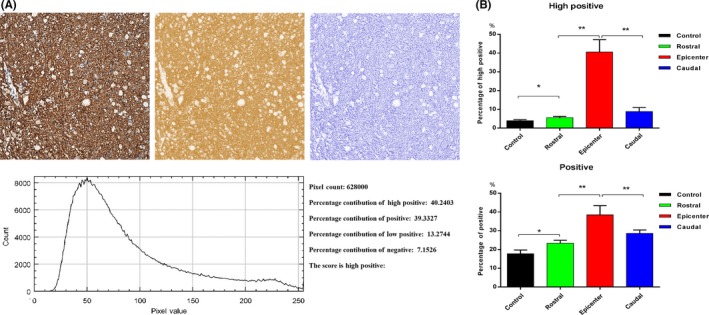

By NF staining, we (Figure 4E) observed that the void was similar to an ellipse from the longitudinal section. Figure 4D,E,F clearly showed that the axons of the white matter fiber bundle degenerated and became messy. By GFAP staining, the darker reactive glial scar almost occupied most of the spinal cord area in the epicenter. At the rostral and caudal levels, reactive glial cells showed proliferation and went beyond the gray matter area. According to the quantitative analysis of scarring, degradation showed in Figure 4H was obvious than it in Figure 4I, the one in Figure 4I was obvious than it in Figure 4G, meaning that the degeneration of epicenter was more severe than the caudal one, the caudal one was more severe than the rostral one. Quantitative analysis of the glial scar was shown in Figure 5.

Figure 5.

Representative histogram profile and score of a cytoplasmic stained image using IHC Profiler. A, Profiling of DAB and hematoxylin‐stained cytoplasmic image sample. The histogram profile corresponds to the pixel intensity value vs corresponding number counts of pixel intensity. The log given below the hematoxylin‐stained image shows the accurate percentage of the pixels present in each zone of pixel intensity and the respective computed score. B, The quantitative analysis results of scarring. The high positive and positive scores are calculated. Both scores are represented as mean ± standard deviation (SD). **P < 0.001, *P < 0.05, N = 5

4. DISCUSSION

In the study, we explored the dynamic changes of the DTI parameters in white matter and gray matter from the lesion epicenter to the rostral and caudal levels over an extended duration post‐SCI and also the pathological mechanism of SCI affecting the DTI changes.

4.1. White matter

The axons were demyelinated and the neural circuit was blocked after SCI. The FA values reflected the proportion of the anisotropic component in the total diffusion tensor. The FA value in white matter was positively correlated with the integrity of myelin, the density, and direction of fibers. Our results showed that the FA value at the epicenter was significantly decreased with time after injury, indicating the disruption of fiber bundle integrity, compactness, and direction. The S5 and S6 that are away from the injury point also showed a statistically significant declination, indicating axonal degeneration at the caudal level. While the sites in the rostral level were away from the injury point, although all the interested areas had undergone the corresponding changes, no site showed a statistically significant change, indicating that the degeneration in caudal ROIs were more severe than the one in rostral ROIs. Glial cells proliferated after SCI and even extended to the white matter area. The proliferative glial cells would aggravate the disorder of density and parallelism of fiber bundles, further promoting the decrease in FA value. Many rodent studies have reported the gradual decrease in the FA values of SCI epicenter with time,8, 13, 17 at the rostral/caudal levels; however, a drastic decrease in FA occurred on day 3 after SCI. The FA at the epicenter and the rostral/caudal levels was stable by day 7 post‐SCI and increased slowly with time.18 In our results, the sites also showed an upward trend or a downward trend, but the overall trend of most sites showed declination. Our results are consistent with most of the similar researches.

The intracellular and extracellular water balance weakened, and cell edema and extracellular space became smaller. A large number of microvasculatures were damaged, leading to hematoma formation. Intramedullary pressure would also increase dramatically. The ADC value reflected the range of diffusion motion of water molecules per unit time, and the ADC value usually declined in the acute phase and often increased in the subacute and chronic phases.19 The results of this study showed that the overall trend of ADC values in different ROIs of white matter was first decreased and then increased, indicating that edema and hematoma were severe in the acute phase. Then, the edema and hematoma were gradually improved with time. Only the ADC values of S4 and S5 that were away from the epicenter showed statistical significance, and the other sites showed no statistical differences. For FA values, the S4, S5, and S6 reached statistical significance, indicating axonal injury, demyelination, and fiber density change were more obvious than edema and hematoma‐related injuries. It meant that anterograde degradation was more obvious than retrograde one. Analysis of MD and RD values for each site throughout the length of the white matter showed similar trends to those observed in ADC values over time.

In addition, the causes that affected diffusion may be consistent with other research reports. Extra‐axonal tissue changes also affected the diffusivity changes in the white matter tracts.17 The decrease in diffusivity was correlated with the severity for up to 40 mm rostral to the injury epicenter, which was consistent with a cellular reaction. Wallerian degeneration in the rostral level from a thoracic injury resulted in microglial and astroglial reactions, with a final formation of glial scar.20, 21, 22 The proteoglycans in the extracellular matrix were increased after SCI, also affecting water diffusion.23 The number of inflammatory cells at locations away from the injury site and even outside the spinal cord could increase24, 25, 26, 27 and the activation of the inflammatory processes helped to explain the changes in water diffusion following SCI in regions remote from the epicenter. In cerebral ischemia,28 the intracellular water compartment determines the overall changes in water diffusion.17 Ischemia after SCI may also aggravate the declination in ADC parameters during acute phase, with recovery of perfusion over time, which in turn contributes to the recovery of ADC.

By analyzing the statistical differences in diffusive changes, we found that there was an obvious asymmetry in the rostral and caudal levels of white matter post‐SCI. Overall, the diffusion changes in the caudal level were higher than that of the rostral level, and the statistical difference at the caudal level was relatively large. Some experts have found dynamic changes of this asymmetry through studying in rats.13 The findings of our study were consistent with the previous studies of asymmetric spinal cord structural degeneration, but previous studies have reported that the caudal level was closer to normal tissue than the rostral, while our results indicated more severe degeneration was at the caudal level than at the rostral level. Previous studies were conducted in rats, while our experiments were conducted in canine models that are ideally used as transformation models from small animals to humans. Animal size and species may be considered as a factor. A previous study observed that the distance between the caudal and rostral levels from epicenter was 6 mm, and our study observed a distance of 3 cm. Hence, distance may be considered as a factor. Previous studies have analyzed ventral, dorsal, and lateral white matter separately, and we analyzed the overall white matter and gray matter cross section. These investigations attributed to the asymmetry of vascular compromise in rostral regions,29 levels of neutrophil enzyme myeloperoxidase,30 expression of the angiogenic gene osteopontin,31 levels of N‐acetyl aspartate,32 and expression of water channel aquaporin‐4.33 In conclusion, previous studies provided an important reference for our research. The mechanisms of degeneration of white matter after SCI are yet to be studied, and the mechanism of action remained somewhat controversial. We also proposed a possible factor. The neural circuit was fractured after SCI, and the caudal levels of spinal cord lacked of nutrient supply, resulting in a relatively severe caudal degradation. Another reason may be the lack of blood supply, which was similar to the reports of other experts. In the future research, we will clarify the research direction and it is worth to explore the gene level mechanism of white matter after SCI.

4.2. Gray matter

Gray matter and white matter have different compositional structures. The gray matter is mainly composed of neuronal soma, dendrites and many glial cells, and a large number of capillaries. SCI easily causes vascular damage, flooding the blood in the gray matter. Neurons that are more sensitive to injury and ischemia rapidly lose their vitality in this microenvironment and promote the proliferation of glial cells.34 Our results showed that the FA values of gray matter were decreased correspondingly with time, but showed no statistical significance. This indicated that the compositional structure of gray matter was not sensitive to the FA value, and there might be less axons in gray matter. There were statistically significant changes in the ADC, MD, and RD values at the injury point, indicating a significant change in the diffusion of water molecules in the gray matter. The microvasculature of gray matter showed injury and bleeding in the acute phase after SCI, while the intracellular and extracellular water balance was weakened. This in turn led to cell edema, the ADC value of the lesion was decreased with time, and the parameters began to rise along with damage recovery. In particular, the formation of cavities after SCI mainly occurred in the gray matter, and there was a large amount of glial scar formation around the hollow edge. This may be another major reason for the variation of the DTI parameters at the point of injury. A study also reported that the astrocytic activity in GM triggered by Wallerian degeneration in WM may also contribute to the changes partially.22, 35, 36 From our findings, FA was not sensitive to the changes in gray matter, and ADC, MD, and RD values are relatively sensitive. So, we recommend to mainly use these three sensitive parameters in the future study. Studies on gray matter should also look for a way to treat SCI.

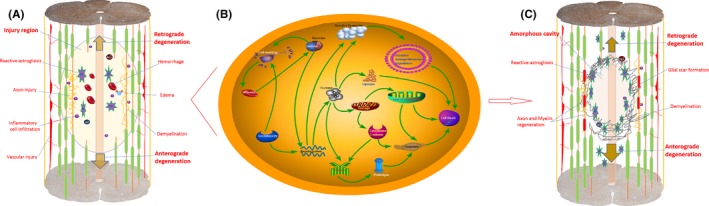

Pathology is the gold standard to verify the SCI and factors affecting the dynamic changes of DTI parameters. After the spinal cord contusion, the oval lesion area was formed in the epicenter area. As time progresses, secondary damage has begun and surpassed the nerve tissue in the damaged area, resulting in the neurological circulatory disturbance and loss of neurological function.37, 38 In our pathological findings, an irregular cavity was formed in the lesion area, which also resulted in various inflammatory factors and glial responses. These results validated the dynamic changes of DTI parameters over time in the gray matter and white matter regions following SCI. The changes of white matter and gray matter in the epicenter were most severe, and the rostral as well as the caudal levels showed corresponding degradation. We further simulated the pathological mechanism of SCI, with retrograde and anterograde degradation rule, based on our findings and related literature reports.39, 40 An oval injured area was formed at the injury site after contusion, axons were injured and fractured, ruptured blood vessels led to hematoma formation, inflammatory cytokines were released and infiltrated at the site of injury (Figure 6). These changes in turn caused intracellular and extracellular homeostasis imbalance and edema, and increased pressure and the damaged axons were demyelinated leading to cell death. The necrotic substance further intensifies the homeostasis, releases the necrosis factor, and causes a vicious cycle of necrosis and cell death. Since then, the nerve conduction pathway was destroyed, and the nerve function was lost. The cascade of this response affected normal spinal cord tissue anterograde and retrograde, resulting in the degenerative responses in normal tissues. Over time, edema, hematoma, and inflammatory cytokines in the damaged area were gradually absorbed and discharged. An irregular cystic cavity in the lesion and reactive glial scar with covered edge were formed. Small amounts of axons and myelin sheaths were repaired, but most of the neural circuits could not be recovered.

Figure 6.

The pathological mechanism simulation of SCI. A, An oval injury area was formed at the injury site in acute stage after SCI, axons were injured and fractured, ruptured blood vessels led to hematoma formation, and inflammatory cytokines were released and infiltrated at the site of injury. These in turn caused intracellular and extracellular homeostasis imbalance and edema, the pressure increased, and then the damaged axons were demyelinated and led to cell death. B, Molecular mechanism simulation of cellular metabolism after ischemia and edema in acute stage after contusion. C, Injury response affected normal spinal cord tissue anterograde and retrograde, resulting in degenerative responses in normal tissues. Over time, the edema, hematoma, and inflammatory cytokines were absorbed and discharged. A cystic cavity was gradually formed, and the reactive glial scar with covered edge was formed. Small amounts of axons and myelin sheaths were repaired, but most of the neural circuits could not be recovered. Based on the figures from Ahuja et al39 and Tyler et al40

The limitations of the current study were as follows: the study animals used are alive under anesthesia, and therefore, the respiratory rate and the heart rate might affect the acquisition of MRI signals. Also, the spatial resolution of DTI was relatively low, and our results were influenced by partial volume effects.

5. CONCLUSION

DTI is more sensitive to the dynamic changes of white matter than gray matter injuries from the lesion epicenter to rostral and caudal levels over an extended duration after SCI. Degeneration of white matter after SCI may be not symmetrical which showed the caudal degradation appeared to be more severe than the rostral one. This indicated the direction for our future research. Based on this, we can find the cause that regulates the pathological mechanism after SCI. This in turn restrains the process of axonal injury, saves the residual nerve tissue, and improves the rehabilitation outcome of SCI.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Supporting information

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (81272164), the Special Fund for Basic Scientific Research of Central Public Research Institutes (2016CZ‐4), Beijing Institute for Brain Disorders (0000‐100031), Basic Scientific Research Foundation of China Rehabilitation Research Center (2017ZX‐22,2017ZX‐20), and the Supporting Program of the “Twelve Five‐year Plan” for Science & Technology Research of China: 2012BAI34B02, the Ministry of Science and Technology of China grants (2015CB351701). And we thank all the other members of Department of Spinal and Neural Function Reconstruction, Beijing Bo’ai Hospital, China Rehabilitation Research Center, thank the company of Xiao‐Qian Ying from School of Rehabilitation Medicine, Capital Medical University and editors of the journal for the help they offered.

Liu C‐B, Yang D‐G, Zhang X, et al. Degeneration of white matter and gray matter revealed by diffusion tensor imaging and pathological mechanism after spinal cord injury in canine. CNS Neurosci Ther. 2019;25:261–272. 10.1111/cns.13044

Chang‐Bin Liu and De‐Gang Yang contributed equally to this work.

Contributor Information

Ming‐Liang Yang, Email: chinayml3@163.com.

Jian‐Jun Li, Email: 13718331416@163.com.

REFERENCES

- 1. Farhadi HF, Kukreja S, Minnema AJ, et al. Impact of admission imaging findings on neurological outcomes in acute cervical traumatic spinal cord injury. J Neurotrauma. 2018;35(12):1398‐1406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Anderson MA, Burda JE, Ren Y, et al. Astrocyte scar formation aids central nervous system axon regeneration. Nature. 2016;532:195‐200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Hu AM, Li JJ, Sun W, et al. Myelotomy reduces spinal cord edema and inhibits aquaporin‐4 and aquaporin‐9 expression in rats with spinal cord injury. Spinal Cord. 2015;53:98‐102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Hu R, Zhou J, Luo C, et al. Glial scar and neuroregeneration: histological, functional, and magnetic resonance imaging analysis in chronic spinal cord injury. J Neurosurg Spine. 2010;13:169‐180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Cohen‐Adad J, Leblond H, Delivet‐Mongrain H, et al. Wallerian degeneration after spinal cord lesions in cats detected with diffusion tensor imaging. Neuroimage. 2011;57:1068‐1076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Liu K, Tedeschi A, Park KK, He Z. Neuronal intrinsic mechanisms of axon regeneration. Annu Rev Neurosci. 2011;34:131‐152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Sun F, Park KK, Belin S, et al. Sustained axon regeneration induced by co‐deletion of PTEN and SOCS3. Nature. 2011;480:372‐375. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Patel SP, Smith TD, VanRooyen JL, et al. Serial diffusion tensor imaging in vivo predicts long‐term functional recovery and histopathology in rats following different severities of spinal cord injury. J Neurotrauma. 2016;33:917‐928. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Wang JY, Bakhadirov K, Devous MS, et al. Diffusion tensor tractography of traumatic diffuse axonal injury. Arch Neurol. 2008;65:619‐626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Huisman TA, Schwamm LH, Schaefer PW, et al. Diffusion tensor imaging as potential biomarker of white matter injury in diffuse axonal injury. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2004;25:370‐376. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Leong D, Calabrese E, White LE, et al. Correlation of diffusion tensor imaging parameters in the canine brain. Neuroradiol J. 2015;28:11‐18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Boekhoff TM, Flieshardt C, Ensinger EM, Fork M, Kramer S, Tipold A. Quantitative magnetic resonance imaging characteristics: evaluation of prognostic value in the dog as a translational model for spinal cord injury. J Spinal Disord Tech. 2012;25:E81‐E87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Ellingson BM, Kurpad SN, Schmit BD. Ex vivo diffusion tensor imaging and quantitative tractography of the rat spinal cord during long‐term recovery from moderate spinal contusion. J Magn Reson Imaging. 2008;28:1068‐1079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Liu C, Yang D, Li J, et al. Dynamic diffusion tensor imaging of spinal cord contusion: a canine model. J Neurosci Res. 2018;96:1093‐1103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Grace CE, Schaefer TL, Herring NR, et al. Effect of a neurotoxic dose regimen of (+)‐methamphetamine on behavior, plasma corticosterone, and brain monoamines in adult C57BL/6 mice. Neurotoxicol Teratol. 2010;32:346‐355. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Varghese F, Bukhari AB, Malhotra R, De A. IHC Profiler: an open source plugin for the quantitative evaluation and automated scoring of immunohistochemistry images of human tissue samples. PLoS One. 2014;9:e96801. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Jirjis MB, Kurpad SN, Schmit BD. Ex vivo diffusion tensor imaging of spinal cord injury in rats of varying degrees of severity. J Neurotrauma. 2013;30:1577‐1586. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Zhao C, Rao JS, Pei XJ, et al. Longitudinal study on diffusion tensor imaging and diffusion tensor tractography following spinal cord contusion injury in rats. Neuroradiology. 2016;58:607‐614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Wang F, Qi HX, Zu Z, et al. Multiparametric MRI reveals dynamic changes in molecular signatures of injured spinal cord in monkeys. Magn Reson Med. 2015;74:1125‐1137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Avellino AM, Hart D, Dailey AT, MacKinnon M,Ellegala D,Kilot M. Differential macrophage responses in the peripheral and central nervous system during wallerian degeneration of axons. Exp Neurol. 1995;136:183‐198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Buss A, Schwab ME. Sequential loss of myelin proteins during Wallerian degeneration in the rat spinal cord. Glia. 2003;42:424‐432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Buss A, Brook GA, Kakulas B, et al. Gradual loss of myelin and formation of an astrocytic scar during Wallerian degeneration in the human spinal cord. Brain. 2004;127:34‐44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Vorisek I, Hajek M, Tintera J, Nicolay K, Syková E. Water ADC, extracellular space volume, and tortuosity in the rat cortex after traumatic injury. Magn Reson Med. 2002;48:994‐1003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Moisse K, Welch I, Hill T, Volkening K, Strong MJ. Transient middle cerebral artery occlusion induces microglial priming in the lumbar spinal cord: a novel model of neuroinflammation. J Neuroinflammation. 2008;5:29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Shi F, Zhu H, Yang S, et al. Glial response and myelin clearance in areas of wallerian degeneration after spinal cord hemisection in the monkey Macaca fascicularis . J Neurotrauma. 2009;26:2083‐2096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Weishaupt N, Silasi G, Colbourne F,Fouad K. Secondary damage in the spinal cord after motor cortex injury in rats. J Neurotrauma. 2010;27:1387‐1397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Gris D, Hamilton EF, Weaver LC. The systemic inflammatory response after spinal cord injury damages lungs and kidneys. Exp Neurol. 2008;211:259‐270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Silva MD, Omae T, Helmer KG, Li F, Fisher M, Sotak CH. Separating changes in the intra‐ and extracellular water apparent diffusion coefficient following focal cerebral ischemia in the rat brain. Magn Reson Med. 2002;48:826‐837. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Deo AA, Grill RJ, Hasan KM, Narayana PA. In vivo serial diffusion tensor imaging of experimental spinal cord injury. J Neurosci Res. 2006;83:801‐810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Carlson SL, Parrish ME, Springer JE, Doty K, Dossett L. Acute inflammatory response in spinal cord following impact injury. Exp Neurol. 1998;151:77‐88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Aimone JB, Leasure JL, Perreau VM,Thallmair M, Christopher Reeve Paralysis Foundation Research Consortium . Spatial and temporal gene expression profiling of the contused rat spinal cord. Exp Neurol. 2004;189:204‐221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Falconer JC, Liu SJ, Abbe RA,Narayana PA. Time dependence of N‐acetyl‐aspartate, lactate, and pyruvate concentrations following spinal cord injury. J Neurochem. 1996;66:717‐722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Nesic O, Lee J, Ye Z, et al. Acute and chronic changes in aquaporin 4 expression after spinal cord injury. Neuroscience. 2006;143:779‐792. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Kluchova D, Kloc P, Klimcik R, Molcakova A, Lovasova K. The effect of long‐term reduction of aortic blood flow on spinal cord gray matter in the rabbit. Histochemical study of NADPH‐diaphorase. Cell Mol Neurobiol. 2006;26:1253‐1264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Ford JC, Hackney DB, Alsop DC, et al. MRI characterization of diffusion coefficients in a rat spinal cord injury model. Magn Reson Med. 1994;31:488‐494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Ellingson BM, Schmit BD, Kurpad SN. Lesion growth and degeneration patterns measured using diffusion tensor 9.4‐T magnetic resonance imaging in rat spinal cord injury. J Neurosurg Spine. 2010;13:181‐192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Yip PK, Malaspina A. Spinal cord trauma and the molecular point of no return. Mol Neurodegener. 2012;7:6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Norenberg MD, Smith J, Marcillo A. The pathology of human spinal cord injury: defining the problems. J Neurotrauma. 2004;21:429‐440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Ahuja CS, Nori S, Tetreault L, et al. Traumatic spinal cord injury‐repair and regeneration. Neurosurgery. 2017;80:S9‐S22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Tyler JY, Xu XM, Cheng JX. Nanomedicine for treating spinal cord injury. Nanoscale. 2013;5:8821‐8836. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials