Abstract

Background/Aims

Dementia is an emerging public health problem in sub-Saharan Africa (SSA). In SSA, the stigma suffered by people with dementia (PWD) can be strongly linked to pejorative social representations, interfering in social relationships with informal caregivers. The objective of the study was to analyze the consequences of social representations of PWD in social interactions with informal caregivers.

Methods

A qualitative study was conducted in Republic of Congo among 93 interviewees. Nondirectional interviews were conducted in local languages and complemented by participating observations. The collected data were transcribed literally, synthesized, and then coded to allow extraction and organization of text segments.

Results

Informal caregivers, daughters-in-laws, were considered as abusers and granddaughters as benevolent. The leaders of syncretic churches and traditional healers were the first therapeutic itineraries of PWD, due to pejorative social representations of disease. Of these, some PWD have appeared at front of a customary jurisdiction for accusations of witchcraft. Dementia, perceived as a mysterious disease by informal caregivers, wasn't medicalized by leaders of syncretic churches, traditional healers, nurses, or general practitioners. Conclusion: Stigma, generated by social representations, can change the patient's behavior and the one of informal caregivers, leading to time delay in the search for appropriate help.

Keywords: Dementia, Stigma, Informal caregivers, Sub-Saharan Africa, Traditional healers

Introduction

Aging of the population in addition to the epidemiological transition is leading to an increase in noncommunicable diseases, including dementia. This condition is often synonymous with end of the scroll, end of route, and body that breaks down [1]. Dementia is a major public health problem and was assimilated to a real “tsunami” because of the growing number of people with dementia (PWD) [2, 3]. In 2015, we estimate that 2.13 million people were living with dementia in sub-Saharan Africa (SSA). This number will reach 3.48 million by 2030 and 7.62 million in 2050, with most important increases expected in Eastern and Central SSA [4]. Most of the PWD in low- and middle-income countries receive care from informal caregivers who are neither trained nor compensated [5, 6, 7]. This informal role, usually assigned to family members, is very ambiguous, either supportive or seen as an obstacle [8, 9]. Psychological and behavioral symptoms of dementia are perceived by informal caregivers as a real threat or imbalance in the family, leading either to their maintenance because of the well-being they provide or to their exclusion [10, 11, 12]. These exclusions, often accompanied by abuse, are depending on the pejorative social representations or negative stereotypes informal caregivers have of PWD [13, 14]. In SSA, these are mainly taken care of by traditional medicine and syncretic churches [15, 16]. PWD scare, sometimes they are considered dangerous and accused of witchcraft, causing their confinement, bondage, and expulsion from the family circle or community and society [17, 18]. Stigma toward PWD will arise from these social representations because it is linked to negative stereotypes [19]. Our hypothesis was that the decrease in family solidarity, which is growing more and more in the Republic of Congo [20], has a considerable impact on the exclusion of PWD from the family circle or from society. Each society interprets differently the causes of disease, natural (caused by infections and others, and so on) and unnatural (caused by witches) [21]. The latter, with the accusation of witchcraft as a family and social phenomenon in SSA (Cameroon, Ivory Coast, Central African Republic, Congo), are the most cited by informal caregivers to explain the evil or misfortune, leading to the solicitations from customary jurisdictions [22]. The purpose of the study was first to understand the social relationships between PWD and their informal caregivers, based on the multiple causes of precariousness (unfavorable living conditions, social representations of the disease, high hospital care costs, poverty, and so on) with which they are confronted generating new forms of discrimination and stigmatization. Then, it was to assess degrees of stigmatization (exclusion, unfair treatment, denial of a right, and so on), according to dominant social codes. The specific objectives here were to analyze the consequences of social representations of PWD in social interactions with informal caregivers, to identify their therapeutic itineraries, and to describe the consequences of witchcraft accusations in urban (Brazzaville) and rural (Gamboma) in the Republic of Congo.

Materials and Methods

Design

An ethnological qualitative study was conducted in the Republic of Congo over 3 months (March – May 2015), 45 days in urban and rural areas. In urban area (Brazzaville), 51 interviewees were included: 19 PWD, 19 informal caregivers, 1 general practitioner, 4 traditional healers, 5 leaders of syncretic churches, and 3 members of a customary jurisdiction. Additionally, 42 interviewees in rural area (Gamboma) were included and distributed as follows: 17 PWD, 17 informal caregivers, 3 nurses, 2 traditional healers, and 3 leaders of syncretic churches. PWD come from a door-to-door cross-sectional study in general population. This prevalence survey, Epidemiology of Dementia in Central Africa, was conducted between November 2011 and December 2012 in 2 areas of Republic of Congo [23].

They were studied and compared for 2 reasons. The first, people aged 60 and over in rural area represent 8% against 3.4% of the total population. The second is that social organization is different in rural areas (existence of an extended family and respect for the status of the elderly) in comparison with an urban area. In the latter, there is the existence of nuclear families, individualism to the detriment of the collective, the lack of priority in health care for the elderly over other family members, presence of many syncretic churches, all leading to the denaturation of the protective status of the elderly. The situation is totally opposite in rural areas. The majority of elderly people own ancestral lands, generating income for all. There is also the existence of an extended family and mutual aid through the exchange of goods and services. All this helps to safeguard the protective status of the elderly. That's why it is relevant to compare both settings [24].

The weaknesses of our study were essentially the refusal of some therapists (managers of syncretic churches and therapeutic healers) to participate and to describe step by step process of their care and the refusal of those in charge of the second customary jurisdiction in urban areas to participate. Some caregivers reportedly filed a complaint in the latter.

On the other side, the strengths of our study were immersion with interviews conducted in local languages within the various ethnic groups, high participation of the interviewees, and the flexibility of the unstructured interview guide designed after a first field visit.

Interviews

An unstructured interview guide was designed to gather diverse information from PWD, informal caregivers, general practitioner, nurses, traditional healers, leaders of syncretic churches and members of a customary jurisdiction through nondirective interviews, conducted in local languages (Lingala, Kituba, Teke, Mbochi, Lari, and French) at their homes and their places of work. Mastery of these languages by the principal investigator has made it possible to avoid as far as possible intermediaries, who are usually major sources of bias, and above all not to be perceived as the “outside” element, that is, the element that comes “from elsewhere” [25]. Unstructured interview guide covered 7 different themes: (1) Identity/family situation; (2) living conditions: material and economic aspects; (3) living conditions: administrative and relational aspects; (4) living conditions: hygiene, food, and sanitary aspects; about dementia: (5) perception and social representations; (6) stigmatizing attitudes, and (7) therapeutic and accusation itineraries.

Participating observations were conducted in parallel to record phenomena that an interviewee could, intentionally or not, leave out and control in his statements [26]. Some devices such as voice recorder and digital camera were used respectively to record nondirective interviews and images during the study. Participating observations conducted concomitantly with nondirective interviews were used to collect data during social interactions. In these latter, I observed among:

- informal caregivers, hesitations, anger, crying, laughter, before or during or even after the interviews and accompanied them in agricultural work, animal husbandry, housework, and various intimate moments (funeral wake, etc.),

- PWD, scars from burns, signs of malnutrition and dehydration, deleterious living conditions compared to those of their caregivers, especially in urban areas,

- traditional healers and leaders of syncretic churches, all the ceremonies of taking charge (deliverance sessions of evil spirit, sacraments, scarification sessions, etc),

- members of customary jurisdiction, shoot a pleading session progress and took pictures of the customary jurisdiction.

The qualitative methodology using nondirective interviews and participating observations dates to Erving Goffman (1922–1982). The latter favors a methodology with participant observation and is particularly interested in social interactions. These qualitative methods were used on the social representations of dementia in the Republic of Congo [27], Tanzania [16, 18], and other studies conducted in SSA [4].

Informal Caregivers

According to the French High Authority of Health, the main caregiver is defined as a nonprofessional person who comes to the aid of a dependent person in his or her entourage for daily life activities [28]. A privileged caregiver, as defined by Larousse Dictionary, has a right, a particular advantage granted to an individual or a category, outside the common law [29]. Thus, traditionally, privileged caregivers are firstly a main caregiver but also enjoy other benefits that are recognized by kinship (beliefs, art, mores, customs, languages, religion, and so on) that other caregivers do not have. This distinction is based on the feelings of well-being or not expressed by PWD toward their informal caregivers. Caregivers in the study were all informal, chosen for their cohabitation with the person with dementia and for their documented kinship ties of alliance, filiation, or germanity.

Therapists and Members of the Customary Jurisdiction

Noninstitutional therapists (traditional healers and leaders of syncretic churches), institutional therapists (general practitioners and nurses), and members of the customary jurisdiction designated by caregivers were contacted at their home address or consulting office or by phone.

Syncretic Church

Born in the colonial era, is an association of 2 or more cultural traits between the imported Christianity and local religious and cultural traditions type: Negro-African and Neo-traditional-African [15]. In this context, they were essentially Pentecostal churches or revival churches and independent African Christian prophetic church.

Customary Jurisdictions

Is the set of written or oral rules. It is born from symbolic systems including knowledge, beliefs, art, morals, law, customs, as well as any disposition or use acquired by man in society [30]. The Republic of the Congo has 2 customary jurisdictions recognized by Presidential Decree No. 2010 − 792 of December 31, 2010. The first is Ouenze, located in the 5th district of Brazzaville. The second is Tenrikyo, located in the 1st district of Brazzaville. It was in the second still called Tenrikyo customary jurisdiction or “jurisdiction for sorcerers” (as it is called by the people). Created in 1972, it has been under the authority of a president for fifteen years, who is a retired health worker. He and his members, initiated by peers in the art of thwarting the schemes of witches and wizards, are volunteer judges in black togas with white flaps [31]. They are seized for the following elements: (1) conflicts that are at the origin of the alteration of social relations between family members, spouses, community inhabitants, beautiful families, children and their parents, (2) conflicts due to provocation, indecent comments that are of a nature to cause disturbances, (3) conflicts born of lies and swindles of all kinds, (4) conflicts of concubinage and premarriage, (5) conflicts arising from widowhood and childhood, (6) conflicts related to theft and misunderstanding, and (7) conflicts linked to witchcraft (disease, bewitches of all genres).

Ethics

We ensure anonymity by assigning specific identifying to each study participant, in a list kept by the principal investigator. All participants gave their written consent or expressed it orally (if illiterate) for their participation in the study (including use of their quotes and pictures). Approval was granted from the Committee for the Ethics of Health Sciences Research of the Republic of Congo, under number No 200/MRSIT/DGRST/ CEHSR.

Analysis

All the narratives were analyzed manually. They were collected and analyzed concurrently to the day. This strategy made it possible to start thinking about the first data collected and then to detect transcription errors [32]. These interviews and the notes taken from the participating observations were first ordered and then transcribed literally, including silences, pauses, misunderstandings, laughter, cries, and irritation. The photographs of people and places (customary jurisdiction) helped contextualize the facts for subsequent literal transcription [25, 33, 34]. After this transcription, the data were first synthesized and put in the interview summary sheets, then intelligently dissected in order to preserve the originality of the information as well as the relationships between the data segments. Finally, these sheets were coded to allow better extraction and organization of important text segments. This organizational phase, which compares a system of categorization of the different segments of text, allowed finding, retrieving, and assembling very quickly segments relating to a theme.

Results

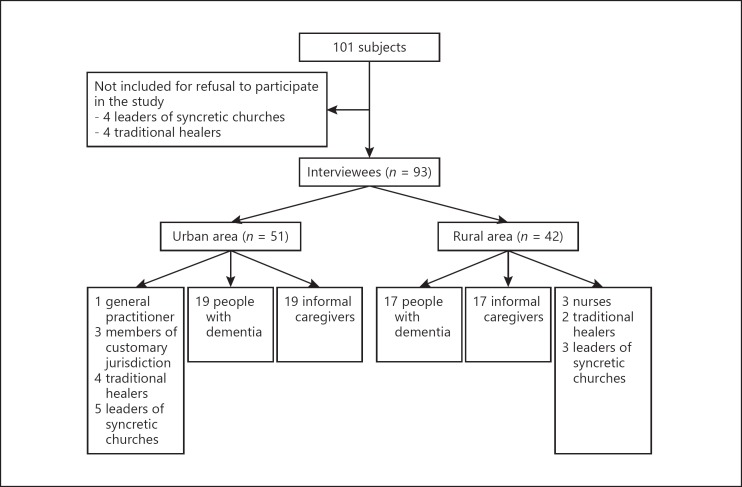

At the beginning of the study, there were 101 subjects, including 4 leaders of syncretic churches and 4 traditional healers were not included for refusal to participate in the study. In total, 93 interviewees divided into 51 in urban areas and 42 in rural areas. Of the 51 in urban, we had: 1 general practitioner, 3 members of customary jurisdiction, 4 traditional healers, 5 leaders of syncretic churches, 19 PWD, and 19 informal caregivers. Of the 42 in rural area, we had: 3 nurses, 2 traditional healers, 3 leaders of syncretic churches, 17 PWD, and 17 informal caregivers (Fig.1).

Fig. 1.

Flow chart.

Sociodemographic Characteristics

PWD were around 80 years old (83.3 ± 6.3 years in urban area vs. 81.4 ± 8.3 years in rural area) and often widows (73.7% in urban vs. 70.6% in rural area) and often frequenting syncretic churches (78.9% in urban vs. 41.2% in rural area). Their caregivers were about forty years old (42.1 years ± 10.8 in urban area vs. 44.1 years ± 18.6 in rural area), mostly of female sex (100% in urban vs. 64.7% in rural area), married (57.9% in urban vs. 58.8% in rural area), and nearly 89.5% attended syncretic churches in urban area vs. 58.8% in rural area. The leaders of syncretic churches and traditional healers were only men aged 42.4 years ± 9.4 in urban area vs. with 53.2 years ± 7.0 in rural area. The general practitioner was a 47-year-old man in urban area, and nurses were all female aged 36.0 years ± 7.0 in rural area. The members of the customary jurisdiction were all men aged 57.3 ± 11.9 years in urban area (Table 1).

Table 1.

Sociodemographic characteristics of the study population, Republic of Congo, 2015

| Urban area, n (%) |

Rural area, n (%) |

|||

| people with dementia (n = 19) |

informal caregivers (n = 19) |

people with dementia (n = 17) |

informal caregivers (n = 17) | |

| Interview time, mean ± SD, min | 95.5±33.6 | 46.4±8.5 | 124.7±33.2 | 48.4±7.8 |

| Age, mean ± SD, years | 83.3±6.3 | 42.4±10.8 | 81.4±8.3 | 44.1±18.6 |

| Gender | ||||

| Female | 13 (68.4) | 19 (100) | 12 (70.6) | 11 (64.7) |

| Male | 6 (31.6) | 0 (0.0) | 5 (29.4) | 6 (35.3) |

| Marital status | ||||

| Married | 3 (15.8) | 11 (57.9) | 4 (23.5) | 10 (58.8) |

| Widow/widower | 16 (84.2) | 0 (0.0) | 13 (76.5) | 0 (0.0) |

| Other | 0 (0.0) | 8 (42.1) | 0 (0.0) | 7 (41.2) |

| Ethnic group | ||||

| Kongo | 13 (68.4) | 7 (36.8) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (5.9) |

| Teke | 3 (15.8) | 2 (10.5) | 14 (82.4) | 12 (70.6) |

| Other | 1 (5.3) | 3 (15.8) | 3 (17.6) | 4 (23.5) |

| School education | ||||

| None | 13 (68.4) | 1 (5.3) | 14 (82.4) | 3 (17.6) |

| Primary | 2 (10.5) | 6 (31.6) | 0 (0.0) | 7 (41.2) |

| Other | 4 (21.1) | 12 (63.2) | 3 (17.6) | 7 (41.2) |

| Religion | ||||

| Syncretic church | 15 (78.9) | 17 (89.5) | 7 (41.2) | 10 (58.8) |

| Other | 4 (21.1) | 2 (10.5) | 10 (58.8) | 7 (41.2) |

| Profession | ||||

| None | 19 (100) | 0 (0.0) | 19 (100) | 0 (0.0) |

| Trader | 0 (0.0) | 12 (63.2) | 0 (0.0) | 4 (23.5) |

| Other | 0 (0.0) | 7 (36.8) | 0 (0.0) | 5 (29.4) |

| GMW | ||||

| ≥137.19 EUR/month | 6 (31.6) | 14 (73.7) | 3 (17.6) | 3 (17.6) |

| ≤137.19 EUR/month | 13 (68.4) | 3 (15.8) | 14 (82.4) | 14 (82.4) |

GMW, Guaranteed minimum wage.

Social Interactions with Informal Caregivers

Data collected from PWD distinguished 2 types of caregivers: main and privileged. In urban area, 68.4% were main caregivers versus 31.6% of privileged caregivers. In rural area, 29.4% were main caregivers vs. 70.6% of privileged caregivers. In general, main caregivers, mainly daughters-in-law, devoted 2–6 h a day on informal care (personal care aids, meal preparation, assistance with household chores, and the different movements) to PWD. In contrast, privileged caregivers, mostly grandchildren devoted 10–15 h a day providing the same informal care to PWD (Table 2).

Table 2.

Repartition between main and privileged informal caregivers of the study population, Republic of Congo, 2015

| Urban area(n = 19),n (%) | Rural area (n = 17),n (%) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| main informal caregivers | privileged informal caregivers | main informal caregivers | privileged informal caregivers | |

| Daughters | 6 (31.6) | 1 (5.3) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (11.8) |

| Daughters-in-law | 5 (26.3) | 2 (10.5) | 3 (17.6) | 2 (11.8) |

| Wives | 2 (10.5) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (5.9) | 1 (5.9) |

| Granddaughters | 0 (0.0) | 3 (15.8) | 0 (0.0) | 3 (17.6) |

| Sons | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (5.9) | 1 (5.9) |

| Younger brothers | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (11.8) |

| Sons-in-law | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (5.9) |

| Informal care duration, h/day | 2–6 | 10–15 | 2–6 | 10–15 |

The following narratives, main and privileged informal caregivers, illustrated the supportive or exclusionary social relationships toward PWD.

“My father abandoned us, we abandon him too....” IDAIB017, Daughter, 40 years old, main caregiver of the PWD, urban area.

“My grandfather, only eats what I cook, only moves with me and only takes his medicine in my presence....” IDAIG008, Daughters-in-law, 25 years old, privileged caregiver of the PWD in rural area.

Therapeutic Itineraries of PWD

In the urban area, the first therapeutic itinerary chosen by informal caregivers was syncretic churches. In this itinerary, 68.4% of PWD were cared for by leaders of syncretic churches. In this pathway, some PWD had undergone exorcism sessions, as well as deprivation of water and food. Others were treated with plants revealed by divine inspiration. The second therapeutic itinerary was that of traditional healers, 26.3% of PWD were treated by medicinal plants and scarifications on the forehead. Only one person with dementia was firstly treated by a leader of syncretic church, then by a traditional healer and finally by the general practitioner. The latter had not recognized the disease and had hospitalized a PWD in the medical department for another problem. Only one person had been seen by the 3 therapists. On the other hand, in the rural area, 58.8% of PWD were treated by traditional healers as the first therapeutic itinerary. The methods used were incantations – prayers, medicinal plants, and scarification on the head, trunk, and limbs. The second therapeutic itinerary was that of leaders of syncretic churches, where 29.4% of PWD were treated by sessions of exorcisms and medicinal plants. Only 11.8% of PWD were initially treated by traditional healers, then leaders of syncretic churches, and finally received by nurses in emergency departments (Table 2). Whether among institutional and noninstitutional therapists, there was a fee for care. Care was paid either in cash or in kind (donation of animals, loincloths, saucepans, hunting weapons, lamps, candles, etc.).

“I am consulted for my medical and spiritual competence.” IDTIB001, General practitioner, 40 years old, urban area.

“She is crazy..., her care can only be done in Brazzaville, not here.” IDTIB003, Nurse, 35 years old, in rural area.

“I have already heard of dementia, ... but there are demons in all dementia: Matthew 17 verse 21: This type of demon comes out only through prayer and fasting.” IDTNIB002, Leaders of syncretic churches, 35 years old, in urban area.

Impact of Income Levels of Informal Caregivers on the Care of PWD

The guaranteed minimum wage in the Republic of Congo is set at 137.19 EUR/month. In urban area, 73.7% of informal caregivers had incomes above the minimum wage. In total, 57.9% of informal caregivers' incomes were destined primarily for the needs of their nuclear families, with excluding the PWD. In rural area, 82.4% of informal caregivers had incomes below the minimum wage (Table 3). These caregivers, in association with the extended family, were supporting PWD daily (meals, medication, clothing, etc.).

Table 3.

Therapeutic itineraries and accusations of witchcraft of people with dementia of the study population, Republic of Congo, 2015

| Urban area (n = 19),n (%) | Rural area (n = 17),n (%) | |

|---|---|---|

| Therapeutic itineraries | ||

| First: leaders of syncretic churches | 13 (68.4) | 10 (58.8) |

| Second: traditional healer | 5 (26.3) | 5 (29.4) |

| Third: leaders of syncretic churches – traditional healer – hospital | 1 (5.3) | 2 (11.8) |

| Accusations of witchcraft by informal caregivers | ||

| No | 6 (31.6) | 12 (70.6) |

| Yes | 13 (68.4) | 5 (29.4) |

“For the care of our sister, mother and grandmother, each one brings what he has food, medicine, clothes......” IDAIG015, Sons-in-law, 38 years old, privileged caregiver of the PWD in rural area.

Accusations of Witchcraft

This accusation of witchcraft came from the narratives recorded of informal caregivers. The latter, based on the social facts (death of a loved one, incurable illnesses, divorce, and so on) with which they were confronted, affirmed that people suffering from dementia would be the culprits. Accused of witchcraft, PWD suffered physical, psychological, and financial abuse. There was 29.6% in rural PWD accused of witchcraft against 68.4% in urban area. Of these charges, there have been no appearances neither convictions of PWD accused of witchcraft in front of the equivalence of a customary jurisdiction in rural area even though they exist. In Brazzaville, 23.1% of PWD had appeared and been sentenced in front of a customary jurisdiction. The latter is official and recognized by a presidential decree, which is not the case of rural area (Table 3).

Consequences for PWD Condemned

They were punished with instruments such as mortar and pestle that accompanies the verdict. These 2 instruments, made of wood and generally placed at the foot of a tree, will be used alternately by the complainant or the accused. At each stroke of pestle in the mortar, the complainant or the accused must repeat the sentences dictated by the person in charge of the ritual. The members of the customary jurisdiction very often use the Nkondi (nail fetishes). This fetish has the role to maintain or restore peace in societies where seat witchcraft. It watches over the interests of individuals, pursues perjuries, and dominates the system and beliefs. It is supposed to carry away with a staggering death any individual who would betray an oath sworn on him. These members also resort in certain circumstances to the leaf from a plant named Ntela (i.e. “tell me or show me who culprit is”). This leaf has the role of identifying the culprit and causing him the maximum harm.

“It took just one death of her grandson for her to be accused of mystical practices. Complaint filed by his daughter-in-law and some family members.” IDTTB001, Member of the customary jurisdiction, 55 years old, urban area.

“Collecting corks (lemonades and beers), at the customary marriages and marital status of his daughter, would have led to divorce in later.” IDTTB001, Member of the customary jurisdiction, 55 years old, urban area.

“People with dementia was HIV-positive and epileptic. Her status as a HIV-positive has always raised questions among her family and neighbours and led them to believe that she was “mystically” transmitting this virus to others. The complaint was filed by his daughter-in-law.” IDTTB001, Member of the customary jurisdiction, 55 years old, urban area.

Discussion

In medicine, ageing is defined as the accumulation of a set of molecular and cellular lesions, which over time will lead to a progressive reduction in physiological resources and a general decrease in the individual's abilities [35]. Aging is considered synonymous with wisdom in Africa. Amadou Hampâtel Bâ, ethnologist and defender of the oral tradition, said “In Africa, when an old man dies, it is a library that burns” [36]. Thus, care for the elderly in this continent is mainly provided by the family, the first informal caregiver in the event of loss of autonomy. The family remains a natural framework, where there are intergenerational relations, social solidarity, exchanges of services, and affectivity [5, 37]. The informal caregivers in our sample mostly were of young women, 40 years old on average, and working in the informal economy. Traditionally, informal caregiver of dependent older people is indeed provided by a family network, predominantly female, who provide multipurpose, and diversified assistance [6, 38]. Women are referred to as “masters of works” of exchanges in the family network and managers of kinship, because they're bringing a psychological help (setting up the support network), a social assistance (administrative management, running), and a domestic help and personal care (medication, dressing, toilets, travel, and so on) [5, 39]. In large part, to maintain this support in the long term, these women are remunerated for services rendered [2, 40, 41]. In low- and middle-income countries, financial compensation of families is virtually nonexistent [4]. In rural area, instability and irregular income of informal caregivers probably have an important role in the exclusion of some PWD. The majority of them have recognition as family well-being because who own the ancestral lands in which informal caregivers work. These ancestral lands generated income to assist firstly PWD and extended families secondly. The large presence of privileged informal caregivers, predominantly of the Teke ethnic group in our rural area, appeases PWD of this same ethnic group which safeguards its specificity. This leads close family members to cooperate with each other regarding the informal care of PWD. Stigmatization of the latter was almost nonexistent [42, 43, 44]. Privileged informal caregivers, mainly granddaughters considered key to kinship, were seen by PWD as providers of better care and especially available. According to kinship, the granddaughter is considered to be the “wife” of the widower, the grandson as the “husband” of the widow or a generational intermediary, which increases the acceptance. They provided an average of 300–450 h/month informal care for PWD, which remains higher at those provided by informal caregivers in France, estimated at 286 h/month [2]. In urban area, despite the regularity and stability of their income informal caregivers were considered as abusers, initiating degrading treatment toward PWD [45, 46, 47, 48]. Daughters and daughter-in-laws were essentially the main informal caregivers. Culturally, daughter-in-laws are considered as “grafts” or “attached pieces” by alliance and ethnic groups that are mostly different from those PWD. This difference could explain in part the depreciation of the latter toward their informal caregivers. The deterioration, social relations between ethnic groups of Congo, finds its meaning in the sociopolitical context that the country knew: fratricidal war in 1993, 1997, 1998, and 2016, leading to avoidance kinship. The deterioration, social relations between ethnic groups of Congo, finds its meaning in the sociopolitical context that the country knew : fratricidal war in 1993, 1997, 1998, and 2016, leading to avoidance kinship [49]. These informal caregivers provided an average of 60–180 h/month informal care for PWD, what remains inferior at those provided by informal caregivers in France, estimated at 286 h/month [2]. Informal caregivers would take revenge on their parents, who today have become ill due to a lack of health care assistance and basic living needs. Decreased support and depreciation toward older people in urban area have been observed in Ghana [48]. This would be caused by the burden of dementia, behavior disorder of PWD, and their pejorative social representations [18, 48, 50]. These will lead to stigma and discrimination against PWD [19], allowing informal caregivers to initiate therapeutic choices (leaders of syncretic churches, hospital, and so on) or in front of a customary jurisdiction. The major form of stigmatization in SSA is the accusation of witchcraft, hence the solicitation of customary jurisdiction [21, 22, 51, 52, 53]. The existence of these customary jurisdictions no longer needs to be demonstrated. Some African countries such as Cameroon, Central African Republic, and Republic of Congo recognize their civil and criminal skills. Cameroonian and Central African Republic criminal law, for example, “witchcraft is punishable by imprisonment for 2–10 years and a fine of EUR 7.62–152.44.” Anyone who engages in witchcraft, magic, or divination that might disturb public order or tranquillity, or harm the persons, property, or fortune of others even in the form of retribution [22]. In this study, the accused of witchcraft, PWD suffered physical, psychological, and financial abuse. In the Middle Ages, in Europe, popular beliefs were dominated by accusations of witchcraft against women who embodied evil, the devil, heresy, and ended up on the stake after appearing before a jurisdiction [54, 55]. Dementia, socioanthropologically, is defined from nine devastating and terrifying images. It is a hollow shell or dehumanizing disease, mysterious disease, sneaky and insidious disease, relentless and inexorable disease, sentence disease, unjust disease, shameful disease, victimizing, and contagious [56]. The nonmedicalization of the disease by informal caregivers leads to preferential attendance by leaders of syncretic churches and traditional healers, than by health structures [57, 58, 59]. In Tanzania, PWD are cared for outside the health system, but by churches and traditional medicine [16].

Conclusion

PWD represent a considerable burden for families that can lead to abusive situations. Stigma, generated by social representations of informal caregivers, can change the patient's behavior, leading to a tendency to mask the disease and a time delay in the search for appropriate help. Involvement in awareness raising capacity building of all actors of civil society could play a crucial role in effective interventions against dementia and abuse of older PWD. The collaboration with these therapists in this type of study will detect cases of not known and undiagnosed dementia.

Disclosure Statement

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Acknowledgments

- AXA Research Fund (2012 – Project – Public Health Institute (Inserm) + APREL CHU LIMOGES,

- ANR Epidemiology of dementia in Central Africa (ANR-09-MNPS-009-01),

- Marien Ngouabi University in Brazzaville (Republic of Congo),

- Ministry of Health of the Republic of Congo,

- University of Limoges, the “Sciences pour l'environnement” Doctoral School and the Limousin Regional Council,

- All administrative authorities in urban and rural areas,

- All participants, informal caregivers, PWD, general practitioner, nurses, leaders of syncretic churches, traditional healers, members of customary jurisdiction.

References

- 1.Duthé G, Pison G, Laurent R. Sénégal: Autrepart; 2010. Situation sanitaire et parcours de soins des personnes âgées en milieu rural africain Une étude à partir des données du suivi de population de Mlomp; pp. pp. 167–87. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Selmès J. John Libbey Eurotext Paris; 2011. La maladie d'Alzheimer, Accompagner votre proche au quotidien. [Google Scholar]

- 3.OMS Rapport mondial sur le vieillissement et la santé. 2016 [cited 2016 May 1];Available from: http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/206556/1/9789240694842_fre.pdf?ua=1. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Guerchet M, Mayston R, Lloyd-Sherlock P, Prince M, Aboderin I, Akinyemi R, et al. Dementia in sub-Saharan Africa Challenges and opportunities. 2017 [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fortin A. La famille, premier et ultime recours. In: Tremblay J.-M., editor. 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dandurand RB, Saillant F. Le réseau familial dans le soin aux proches dépendants. 2005 [cited 2017 Oct 23];Available from: http://www.medsp.umontreal.ca/ruptures/pdf/articles/rup102_199.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Prince M, Wimo A, Guerchet M. The global impact of dementia An analysis of prevalence, incidence, cost and trends. In: Gemma CA, Wu Y-T, Prina M, editors. 2015. [cited 2015 Sep 30];Available from: http://www.alz.co.uk/research/WorldAlzheimerReport2015.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ladouceur L. Dynamique de l'aide informelle auprès des personnes âgées. Reflets Rev D'intervention Soc Communaut. 1996;2((2)):100. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fainzang S. Souffrances familiales. Filiation, couple et parentalité. Paris: Dunod; 2015. Les ambiguïtés du rôle familial. Un regard anthropologique sur le lien famille-santé; pp. pp. 223–30. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Finkel SI, Costa e Silva J, Cohen GD, Miller S, Sartorius N. Behavioral and Psychological Symptoms of Dementia: A Consensus Statement on Current Knowledge and Implications for Research and Treatment. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 1998;6((2)):97–100. doi: 10.1017/s1041610297003943. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Shaji KS, Smitha K, Lal KP, Prince MJ. Caregivers of people with Alzheimer's disease: a qualitative study from the Indian 10/66 Dementia Research Network. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2003 Jan;18((1)):1–6. doi: 10.1002/gps.649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cavayas M, Raffard S, Gély-Nargeot MC. Stigmatisation dans la maladie d'Alzheimer, une revue de la question. Geriatr Psychol Neuropsychiatr Vieil. 2012 Sep;10((3)):297–305. doi: 10.1684/pnv.2012.0356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pitaud P. Exclusion, maladie d'Alzheimer et troubles apparentés : le vécu des aidants. France, ERES, 2007 [cited 2016 Feb 25]. Available from: https://www.cairn.info/exclusion-maladie-d-alzheimer-et-troubles-apparent–9782749206523.htm. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Côté V. La stigmatisation des aidants familiaux de personnes atteintes par la maladie d'Alzheimer. 2008 [cited 2017 Feb 14];Available from: https://papyrus.bib.umontreal.ca/xmlui/handle/1866/2676. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Malu-Malu JJ. KARTHALA Editions; 2014. Le Congo Kinshasa. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hindley G, Kissima J L., Oates L, Paddick S-M, Kisoli A, Brandsma C, et al. The role of traditional and faith healers in the treatment of dementia in Tanzania and the potential for collaboration with allopathic healthcare services: Table 1. Age Ageing. 2016 doi: 10.1093/ageing/afw167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kehoua G, Dubreuil C-M, Ndamba-Bandzouzi B, Guerchet M, Mbelesso P, Dartigues J-F, et al. From the social representation of the people with dementia by the family carers in Republic of Congo towards their conviction by a customary jurisdiction, preliminary report from the EPIDEMCA-FU study: Social representation of demented people and conviction by a tribunal. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2016 doi: 10.1002/gps.4474. n/a-n/a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mushi D, Rongai A, Paddick SM, Dotchin C, Mtuya C, Walker R. Social representation and practices related to dementia in Hai District of Tanzania. BMC Public Health. 2014 Mar;14((1)):260. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-14-260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Goffman E. Stigmate: les usages sociaux des handicaps. Paris, les éditions de minuit. 1975 [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rapport Ministère Affaire Sociale Congo Plan d'action national en faveur des personnes âgées au Congo. 2013 [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bouju J, Martinelli B. KARTHALA Editions; 2012. Sorcellerie et violence en Afrique. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rosny E de. Justice et sorcellerie en Afrique. Études. 2005 [cited 2015 Oct 23];Tome 403:171–181. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Guerchet M, Mbelesso P, Ndamba-Bandzouzi B, Pilleron S, Desormais I, Lacroix P, et al. EPIDEMCA group Epidemiology of dementia in Central Africa (EPIDEMCA): protocol for a multicentre population-based study in rural and urban areas of the Central African Republic and the Republic of Congo. Springerplus. 2014 Jul;3((1)):338. doi: 10.1186/2193-1801-3-338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Batsanga G, Ganga AD, Bilongo J, Mboko Ibara SB, Ampale EG, Mbemba V, et al. Enquête démographique et de santé du Congo (EDSC-II) 2011-2012. 2012 [cited 2015 Nov 27]; Available from: http://www.cnsee.org/pdf/EDSC2012.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Beaud S, Weber F. Guide de l'enquête de terrain. Paris, La découverte, 2010 [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tillard B. Temps d'observation ethnographique et temps d'écriture. Sci Léducation - Pour LÈre Nouv. 2011;44:35. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Faure-Delage A, Mouanga AM, M'belesso P, Tabo A, Bandzouzi B, Dubreuil CM, et al. Socio-Cultural Perceptions and Representations of Dementia in Brazzaville, Republic of Congo: the EDAC Survey. Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord Extra. 2012 Jan;2((1)):84–96. doi: 10.1159/000335626. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.HAS Recommandations de bonne pratique Maladie d'Alzheimer et maladies apparentées: suivi médical des aidants naturels. 2010 [cited 2016 Mar 12]; Available from: http://www.has-sante.fr/portail/upload/docs/application/pdf/2010-03/maladie_dalzheimer_-_suivi_medical_des_aidants_naturels_-_synthese.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rey-Debove J, Rey A. Dictionnaires le Robert Paris; 2000. Le Petit Robet, Dictionnaire de la langue française. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Magnant JP. Droit Cult Rev Int Interdiscip; 2004. Le droit et la coutume dans l'Afrique contemporaine; pp. pp. 167–92. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Talani N, Ndongo AS, Ndongo A. Sorcellerie et fétichisme: un frein à la modernité. 2015 [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lanzarini C, Bruneteaux P. Les entretiens informels. Soc Contemp. 1998;30((1)):157–80. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Laburthe-Tolra P, Warnier JP. PUF; 1993. Ethnologie, Anthropologie. Presses Universitaires de France. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gervereau L. La Découverte Paris; 2004. Voir, comprendre, analyser les images. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Steves CJ, Spector TD, Jackson SH. Ageing, genes, environment and epigenetics: what twin studies tell us now, and in the future. Age Ageing. 2012 Sep;41((5)):581–6. doi: 10.1093/ageing/afs097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.M'Boukou S. La mort du vieillard… Errances, impasses et détours du discours négro-africain contemporain. Portique Rev Philos Sci Hum. 2008 [cited 2018 Mar 4]; Available from: http://journals.openedition.org/leportique/1793. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bucki B, Spitz E, Baumann M. Prendre soin des personnes après AVC : réactions émotionnelles des aidants informels hommes et femmes. Santé Publique. 2012;24:143–156. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Saillant F. Int Rev Community Dev; 1992. La part des femmes dans les soins de santé; p. p. 95. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Facchini C, Lesemann F. Int Rev Community Dev; 1992. Devenir une mère pour sa propre mère; p. p. 63. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lavoie JP, Grand A, Guberman N, Andrieu S. Toulouse: ERES; 2005. L'État face aux solidarités familiales à l'égard des parents âgés fragilisés : substitution, soutien ou responsabilisation. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Guberman N. La rémunération des soins aux proches : enjeux pour les femmes. Nouv Prat Soc. 2003;16((1)):186. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Rakotonarivo A. La solidarité intergénérationnelle en milieu rural malgache. Autrepart. 2010:111–130. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Le Bihan-Youinou B, Martin C. Travailler et prendre soin d'un parent âgé dépendant. Travail Genre Soc. 2006;16((16)):77. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Rosay-Notz H. Prise en charge des personnes âgées dans les sociétés traditionnelles. Etudes Sur Mort. 2004;126((2)):27. [Google Scholar]

- 45.OMS AMP: Réduire la stigmatisation et la discrimination envers les personnes âgées souffrant de troubles mentaux. 2002 [cited 2016 Mar 11]; Available from: http://www.who.int/entity/mental_health/media/en/consensus_elderly_fr.pdf?ua=1. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Harrigan M. La maltraitance des personnes âgées atteintes de la maladie d'Alzheimer ou d'une affection connexe: une analyse documentaire. 2010 [cited 2015 Feb 3]; Available from: http://www.alzheimer.ca/~/media/Files/national/Articles-lit-review/article_elderabuse_2011_f.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Berg N, Moreau A, Giet D. La maltraitance des personnes âgées, un phénomène de société. Rev Med Brux. 2005;26:344–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Aboderin I. Decline in material family support for older people in urban Ghana, Africa: understanding processes and causes of change. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 2004 May;59((3)):S128–37. doi: 10.1093/geronb/59.3.s128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Radcliffe-Brown AR, Marin L, Marin L. Structure et fonction dans la société primitive. Minuit Paris, 1968 [cited 2016 Dec 17]. Available from: http://trafficlight.bitdefender.com/info?url=http%3A//madagascar-interculturel.e-monsite.com/medias/files/a-radcliffe-structure-et-fonction.docx&language=fr_FR. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Truzzi A, Valente L, Ulstein I, Engelhardt E, Laks J, Engedal K. Burnout in familial caregivers of patients with dementia. Br J Psychiatry. 2012 Dec;34((4)):405–12. doi: 10.1016/j.rbp.2012.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Douzima-Lawson E. L'accusation de la sorcellerie et les droits de la femme en République Centrafricaine. 2008 [cited 2015 Feb 4]; Available from: http://recaa.mmsh.univ-aix.fr/2/Documents/2-8.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Bainilago L. Les accusations de la sorcellerie au regard de l'anthropologie. Acte Colloq Univ Bangui. 2008 [cited 2015 Dec 5]; Available from: http://recaa.mmsh.univ-aix.fr/2/Documents/2-9.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Mayneri AC. Sorcellerie et violence épistémologique en Centrafrique. L'Homme. 2014;211:75–95. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Walter P. Jean-Paul Gisserot France; 2017. Croyances populaires au Moyen Âge. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Loi S, Chiu E. Witchcraft and Huntington's disease: a salutary history of societal and medical stigmatisation. Australas Psychiatry. 2012 Oct;20((5)):438–41. doi: 10.1177/1039856212459587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Ngatcha‐Ribert L. Maladie d‘Alzheimer et société : une analyse des représentations sociales. Psychol Neuropsychiatr Vieil. 2004;2:49–66. [cited 2015 Sep 30] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Soiron Fallut M. Les églises de réveil en Afrique centrale et leurs impacts sur l'équilibre du pouvoir et la stabilité des Etats : les cas du Cameroun, du Gabon et de la République du Congo. 2012 [cited 2017 Feb 5]; Available from: http://www.defense.gouv.fr/content/download/198377/2193588/file/EPS2012-Eglises%20de%20r%C3%A9veil%20en%20Afrique%20centrale.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Tonda J. Congo, Gabon: KARTHALA Editions; 2002. La guérison divine en Afrique centrale. [Google Scholar]

- 59.OMS Stratégie de l'OMS pour la médecine traditionnelle pour 2014-2023. 2013 [cited 2016 Dec 2]; Available from: http://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/95009. [Google Scholar]