Abstract

Purpose

To study the proportion of eyelid malignant tumors in an Asian Indian population and to review their clinical features and outcomes.

Methods

This is a retrospective study of 536 patients.

Results

The mean age at presentation with eyelid malignancy was 58 years. Histopathology-proven diagnoses of these patients included sebaceous gland carcinoma (SGC) (n = 285, 53%), basal cell carcinoma (BCC) (n = 128, 24%), squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) (n = 99, 18%), and miscellaneous tumors (n = 24, 4%). The statistically significant differences between eyelid malignant tumors included age at presentation, tumor location, and tumor extent. The clinicopathological correlation of SGC, BCC, SCC, and miscellaneous tumors was 91, 86, 46, and 38% (p = 0.001), respectively. Comparing SGC with BCC, SCC, and miscellaneous tumors, SGC was more commonly associated with tumor recurrence (21 vs. 3, 8, and 13%; p = 0.001), systemic metastasis (13 vs. 0, 4, and 13%; p = 0.001), and death (9 vs. 0, 4, and 0%; p = 0.004). Compared to SGC, BCC, and SCC, locoregional lymph node metastasis was more common with miscellaneous tumors (26 vs. 16, < 1, and 8%; p = 0.001) over a mean follow-up period of 19 months.

Conclusion

In Asian Indians, SGC is twice as common as BCC and 3 times more common than SCC. SGC is associated with poorer prognosis compared to other eyelid malignant tumors.

Keywords: Eyelid malignant tumors, Asian Indian population, Sebaceous gland carcinoma, Basal cell carcinoma, Squamous cell carcinoma, Miscellaneous tumors

Introduction

In America and Europe, the most common malignant tumor of the eyelid is basal cell carcinoma (BCC), accounting for 80–95% of all eyelid malignancies [1, 2, 3, 4, 5]. Squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) (< 5%), sebaceous gland carcinoma (SGC) (1–3%), malignant melanoma (1%), and miscellaneous tumors (< 1%) constitute the rest of eyelid malignancies [1]. In a large series of 5,504 cases with eyelid tumors in a European population including 894 malignant eyelid tumors, BCC was seen in 86%, SCC in 7%, SGC in 3%, and miscellaneous tumors in 4% of cases [2]. Similarly, in studies from the USA, BCC was seen in 82–91%, SCC in 2–9%, SGC in 0–6%, and miscellaneous tumors in < 1–9% of cases [3, 5].

The reports from Asia and our personal experience are contrary to this observation. BCC is less common (11–65%) while SCC (5–48%) and SGC (7–56%) occur more frequently than in the West [6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17, 18, 19, 20, 21]. In a large study of 1,086 malignant eyelid tumors from China, BCC accounted for 38%, SCC was seen in 19%, SGC in 32%, and miscellaneous tumors in 7% of cases [6]. However, there are no large case series on malignant eyelid tumors from an Asian Indian population. In this study, we will discuss the proportion of all histopathology-proven eyelid malignancies in an Asian Indian population and compare the clinical presentation, treatment, and outcomes of common eyelid malignancies.

Methods

This is a retrospective study conducted at the Operation Eyesight Universal Institute for Eye Cancer, LV Prasad Eye Institute, Hyderabad, India. Institutional review board approval was obtained. A search was conducted in our medical records and ophthalmic pathology database for the diagnosis of eyelid malignancies. All cases with histopathology-proven eyelid malignancy during the period from January 1995 to December 2016 were included in this analysis. Those patients with a single visit to our institute with a clinical diagnosis of an eyelid malignancy but without a histopathology confirmation of the diagnosis were excluded from the study.

The following data was extracted from the medical records: age (years), gender, tumor location, tumor extent, tumor growth pattern, tumor size, tumor classification based on the 8th edition of the American Joint Committee Classification [22], clinical diagnosis, treatment details, and final histopathology diagnosis. Clinical photographs were reviewed in all cases to confirm the tumor details. The following data related to outcome were recorded: tumor recurrence, globe salvage, locoregional lymph node metastasis, systemic metastasis, and death. The follow-up duration of each patient was also recorded.

The data were analyzed based on age at presentation and gender. They were further grouped into 4 categories and analyzed based on the diagnosis of SGC, BCC, SCC, and miscellaneous tumors.

For the literature review, a search was conducted with the keywords “malignant,” “tumor,” “eyelid,” and “cancer” in PubMed and Google Scholar, and all related articles were reviewed. Publications from Asian countries were analyzed further.

Statistical Analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using the software Origin v7.0 (OriginLab Corporation, Northampton, MA, USA). Continuous data were analyzed for normality by the Shapiro-Wilk test and described in terms of mean, median, and range. Among the 4 groups, the data were compared using the Kruskal-Wallis test and post hoc analysis was performed using the Mann-Whitney test (multiple comparisons). Categorical data were described in terms of proportions; among the 4 groups, comparisons were made using the χ2 test and post hoc analysis was performed also using the χ2 test (multiple comparisons). Kaplan-Meier survival analysis was performed to evaluate the probability of survival over time (events being lymph node involvement, distant metastasis, or death). The log-rank test was performed to test if the survival probabilities differed among the tumor subtypes. A p value of less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

A total of 536 patients with a histopathology-proven diagnosis of eyelid malignancy were included in this study. The mean age at presentation with eyelid malignancy was 58 years (median, 60 years; range, 4–100 years). The mean age at presentation was 58 years for SGC, 60 years for BCC, 55 years for SCC, and 50 years for miscellaneous tumors. Histopathology-proven diagnoses of these patients (Table 1; Fig. 1) included SGC (n = 285, 53%), BCC (n = 128, 24%), SCC (n = 99, 18%), malignant melanoma (n = 12, 2%), mucoepidermoid/adenosquamous carcinoma (n = 7, 1%), lymphoma (n = 2, < 1%), Merkel cell carcinoma (n = 1, < 1%), adenoid cystic carcinoma (n = 1, < 1%), and metastases from lung adenocarcinoma (n = 1, < 1%). There was a female preponderance for all malignant tumors of the eyelid (Table 2). History of prior surgical intervention was present in 189 (35%) cases including SGC (n = 118, 41%), BCC (n = 23, 18%), SCC (n = 42, 42%), and miscellaneous tumors (n = 16, 67%). Based on multiple comparisons and statistical analysis, statistically significant differences were noted among various tumors (Table 3). The statistically significant differences among the 4 groups (SGC, BCC, SCC, and miscellaneous tumors) are mentioned below.

Table 1.

Patients with malignant tumors of the eyelid (n = 536)

| Feature | n (%) |

|---|---|

| Histopathology diagnosis Sebaceous gland carcinoma | 285 (53) |

| Basal cell carcinoma | 128 (24) |

| Squamous cell carcinoma | 99 (l8) |

| Malignant melanoma | 12 (2) |

| Mucoepidermoid carcinoma | 7 (1) |

| Lymphoma | 2 (<1) |

| Merkel cell carcinoma | 1 (<1) |

| Adenoid cystic carcinoma | 1 (<1) |

| Metastasis | 1 (<1) |

Fig. 1.

Malignant eyelid tumors in Asian Indian patients. a Nodular variant of sebaceous gland carcinoma (SGC) involving the upper eyelid. b Nodulo-ulcerative variant of SGC with predominant upper tarsal conjunctival involvement. c Large nodular variant of SGC involving lower eyelid. d, e Pigmented basal cell carcinoma (BCC) involving lower eyelid. f Pigmented BCC involving lateral canthus and extending into the lateral orbit. g Diffuse squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) with thickening of lower eyelid. h SCC of the lower eyelid with extensive keratin. i Nodulo-ulcerative SCC of the upper eyelid with central ulceration. j Malignant melanoma of the lower eyelid. k Mucoepidermoid/adenosquamous carcinoma of the lower eyelid and medial canthus. l Diffuse Merkel cell carcinoma of the upper eyelid with purplish-red discoloration.

Table 2.

Malignant eyelid tumors in Asian Indian population based on age, gender, and diagnosis

| Age, years |

SGC (n = 285) |

BCC (n = 128) |

SCC (n = 99) |

Miscellaneous tumors (n = 24) |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| male | female | male | female | male | female | male | female | |

| <10 | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1 (1) | 1 (1) | 0 (0) | 1 (4) |

| 11–20 | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1 (1) | 1 (1) | 0 (0) | 2 (8) | 0 (0) |

| 21–30 | 3 (1) | 5 (3) | 1 (1) | 3 (2) | 3 (3) | 1 (1) | 2 (8) | 0 (0) |

| 31–40 | 10 (4) | 14 (5) | 4 (3) | 4 (3) | 3 (3) | 4 (4) | 3 (13) | 2 (8) |

| 41–50 | 13 (5) | 40 (14) | 5 (4) | 10 (8) | 13 (13) | 12 (12) | 1 (4) | 1 (4) |

| 51–60 | 30 (11) | 51 (18) | 13 (10) | 23 (18) | 8 (8) | 18 (18) | 1 (4) | 0 (0) |

| 61–70 | 37 (13) | 34 (12) | 14 (11) | 14 (11) | 12 (12) | 9 (9) | 2 (8) | 1 (4) |

| 71–80 | 15 (5) | 20 (7) | 11 (9) | 16 (13) | 4 (4) | 5 (5) | 4 (17) | 3 (13) |

| 81–90 | 5 (3) | 6 (2) | 4 (3) | 5 (4) | 1 (1) | 3 (3) | 1 (4) | 0 (0) |

| >90 | 2 (<1) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

Values aren (%).

Table 3.

Details of patients with malignant tumors of the eyelid

| Feature | SGC (n = 285) | BCC (n = 128) | SCC(n = 99) | Miscellaneous(n = 24) | All cases(n = 536) | p value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age at presentation, years | 58 (60, 21–100) | 60 (61, 20–88) | 55 (55, 8–90) | 50 (49, 4–81) | 58 (60, 4–100) | 0.01**a |

| Gender | ||||||

| Male | 115 (40) | 52 (41) | 46 (46) | 16 (67) | 229 (43) | 0.47*** |

| Female | 170 (60) | 76 (59) | 53 (54) | 8 (33) | 307 (57) | 0.53*** |

| Tumor epicenter | ||||||

| Upper eyelid | 168 (59) | 22 (17) | 40 (40) | 11 (46) | 241 (45) | <0.001***<, b |

| Lower eyelid | 82 (29) | 75 (59) | 41 (41) | 9 (38) | 207 (39) | 0.003***c |

| Medial canthus | 9 (3) | 13 (10) | 5 (5) | 3 (13) | 30 (6) | 0.03***d |

| Lateral canthus | 7 (2) | 10 (8) | 5 (5) | 0 (0) | 22 (4) | 0.07*** |

| Diffuse | 19 (7) | 8 (6) | 8 (8) | 1 (4) | 36 (7) | 0.92*** |

| Tumor pattern (n = 519) | ||||||

| Nodular | 155 (56) | 52 (42) | 51 (52) | 13 (54) | 271 (51) | 0.52*** |

| Nodulo-ulcerative | 88 (31) | 63 (51) | 40 (40) | 5 (21) | 196 (37) | 0.07*** |

| Papillary | 7 (2) | 0 (0) | 3 (3) | 2 (8) | 12 (2) | 0.07*** |

| Cystic | 7 (2) | 5 (4) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 12 (2) | 0.22*** |

| Fungating mass | 20 (7) | 3 (2) | 3 (3) | 2 (8) | 28 (5) | 0.17*** |

| Tumor diameter, mm | 18 (14, 1–100) | 15 (12, 2–50) | 18 (15, 2–60) | 19 (14, 1–55) | 17 (13, 1–100) | 0.46** |

| Tumor thickness, mm | 6 (4, 1–44) | 5 (4, 1–28) | 8 (4, 1–55) | 7 (4, 1–36) | 6 (4, 1–55) | 0.15** |

| Tumor extent at presentation | ||||||

| Orbit | 35 (12) | 8 (6) | 16 (16) | 7 (29) | 66 (12) | 0.03***e |

| Maxillary sinus | 4 (1) | 1 (<1) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 5 (<1) | 0.61*** |

| Frontal sinus | 2 (<1) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 2 (<1) | 0.63*** |

| Ethmoid sinus | 2 (<1) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 2 (<1) | 0.63*** |

| Intracranial extension | 3 (1) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 3 (<1) | 0.45*** |

| T classification based on8th edition AJCC staging | ||||||

| T1 | 104 (37) | 49 (38) | 26 (26) | 8 (33) | 187 (35) | 0.54*** |

| T2 | 92 (32) | 47 (37) | 37 (37) | 3 (13) | 179 (33) | 0.32*** |

| T3 | 30 (11) | 13 (10) | 7 (7) | 3 (13) | 53 (10) | 0.80*** |

| T4 | 59 (21) | 19 (15) | 29 (29) | 10 (42) | 117 (22) | 0.054*** |

| Primary treatment (n = 518) | 275 | 123 | 97 | 23 | ||

| Wide excision biopsy | 218 (79) | 116 (94) | 74 (76) | 16 (70) | 424 (82) | 0.62*** |

| Orbital exenteration | 38 (14) | 6 (5) | 18 (19) | 6 (26) | 68 (13) | 0.02***,f |

| Systemic chemotherapy | 17 (6) | 0 (0) | 4 (4) | 1 (4) | 22 (4) | 0.06*** |

| External beam radiotherapy | 2 (<1) | 1 (<1) | 1 (1) | 0 (0) | 4 (<1) | 0.97*** |

| Clinical diagnosis correlating histopathological diagnosis | 258 (91) | 110 (86) | 46 (46) | 9 (38) | 423 (79) | 0.001***,g |

| Outcome (n = 518)* | ||||||

| Tumor recurrence | 60 (21) | 4 (3) | 8 (8) | 3 (13) | 75 (14) | 0.001***h |

| Locoregional lymph node metastasis | 45 (16) | 1 (<1) | 8 (8) | 6 (26) | 60 (12) | 0.001***i |

| Systemic metastasis | 35 (13) | 0 (0) | 4 (4) | 3 (13) | 42 (8) | 0.001***,j |

| Death due to the disease | 24 (9) | 0 (0) | 4 (4) | 0 (0) | 28 (5) | 0.004***,k |

| Globe salvage | 225 (82) | 116 (94) | 77 (79) | 16 (70) | 434 (84) | 0.72*** |

| Follow-up period, months | 15 (5, <1–185) | 29 (11, <1–273) | 22 (10, <1–149) | 12 (5, <1–83) | 19 (7, <1–273) | na |

Values aren (%) or mean (median, range), as appropriate. SGC, sebaceous gland carcinoma; BCC, basal cell carcinoma; SCC, squamous cell carcinoma;

18 patients were lost to follow-up after incision biopsy at presentation;

Kruskal-Wallis test;

χ2 test; na, not applicable.

Post hoc analysis with Bonferroni correction showed that only BCC and SCC were significantly different from each other (p = 0.003, Mann-Whitney test).

Post hoc analysis with Bonferroni correction showed that only BCC was significantly different from SCC (p = 0.004,χ2 test) and SGC (p &amp;amp;lt; 0.001,χ2 test).

Post hoc analysis with Bonferroni correction showed that only BCC was significantly different from SGC (p &amp;amp;lt; 0.001,χ2 test).

Post hoc analysis with Bonferroni correction showed that only BCC was significantly different from SGC (p = 0.006,χ2 test).

Post hoc analysis with Bonferroni correction showed that only BCC was significantly different from miscellaneous tumors (p = 0.003,χ2 test).

Post hoc analysis with Bonferroni correction showed that only BCC was significantly different from SCC (p = 0.004,χ2 test) and miscellaneous tumors (p = 0.003,χ2 test).

Post hoc analysis with Bonferroni correction showed that only SCC was significantly different from SGC (p = 0.001,χ2 test) and BCC (p = 0.005,χ2 test).

Post hoc analysis with Bonferroni correction showed that only SGC was significantly different from BCC (p &amp;amp;lt; 0.001,χ2 test) and SCC (p = 0.012,χ2 test).<

Post hoc analysis with Bonferroni correction showed that only BCC was significantly different from SGC (p &amp;amp;lt; 0.001,χ2 test), SCC (p = 0.007,χ2 test), and miscellaneous tumors (p &amp;amp;lt; 0.001,χ2 test).

Post hoc analysis with Bonferroni correction showed that only BCC was significantly different from SGC (p &amp;amp;lt; 0.001,χ2 test) and miscellaneous tumors (p &amp;amp;lt; 0.001,χ2 test).

Post hoc analysis with Bonferroni correction showed that only BCC was significantly different from SGC (p = 0.001,χ2 test).

SGC versus BCC

The tumor epicenter was most often the upper eyelid in SGC (59%) and the lower eyelid in BCC (59%) (p < 0.001). Statistically significant differences between SGC and BCC included higher rates of tumor recurrence (21 vs. 3%; p < 0.001), regional lymph node metastasis (16 vs. < 1%; p < 0.001), systemic metastasis (13 vs. 0%; p < 0.001), and death due to metastasis (9 vs. 0%; p = 0.001).

SGC versus SCC

The clinicopathological correlation was better with SGC compared to SCC (91 vs. 46%; p = 0.001). Tumor recurrence was more common with SGC compared to SCC (21 vs. 8%; p = 0.012).

BCC versus SCC

The patients with BCC were older than those with SCC (60 vs. 55 years; p = 0.003). The following factors were more common and statistically significant with SCC compared to BCC: tumor epicenter location in the upper eyelid (40 vs. 17%; p = 0.004), the need for orbital exenteration (19 vs. 5%; p = 0.004), and locoregional lymph node metastasis (8 vs. < 1%; p = 0.007). The clinicopathological correlation was better with BCC compared to SCC (86 vs. 46%; p = 0.005).

BCC versus Miscellaneous Tumors

The following factors were more common with miscellaneous tumors compared to BCC: orbital tumor extension (29 vs. 6%; p = 0.003), need for orbital exenteration (26 vs. 5%; p = 0.003), locoregional lymph node metastasis (26 vs. < 1%; p < 0.001), and systemic metastasis (13 vs. 0%; p < 0.001).

Overall, SGC (n = 38) and miscellaneous tumors (malignant melanoma [n = 3], mucoepidermoid/adenosquamous carcinoma [n = 2], lymphoma [n = 1], and metastasis [n = 1]) were more commonly associated with locoregional tumor invasion into the orbit/paranasal sinuses/brain compared to SCC (n = 16) and BCC (n = 9). Locoregional lymph node metastasis was more common in patients with miscellaneous tumors (n = 6, including malignant melanoma [n = 2], Merkel cell carcinoma [n = 1], lymphoma [n = 1], eyelid metastasis [n = 1], and mucoepidermoid/adenosquamous carcinoma [n = 1]). Over a mean follow-up period of 19 months (median, 7 months; range, 1 week to 273 months), tumor recurrence (21%), systemic metastasis (13%), and death due to metastasis (9%) occurred more commonly in patients with SGC compared to other eyelid malignancies.

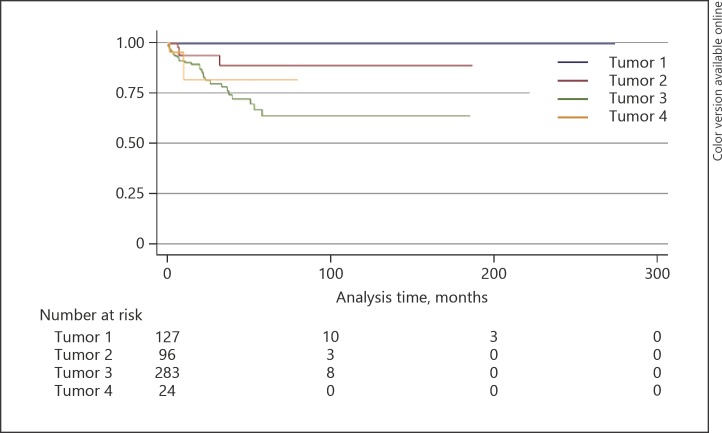

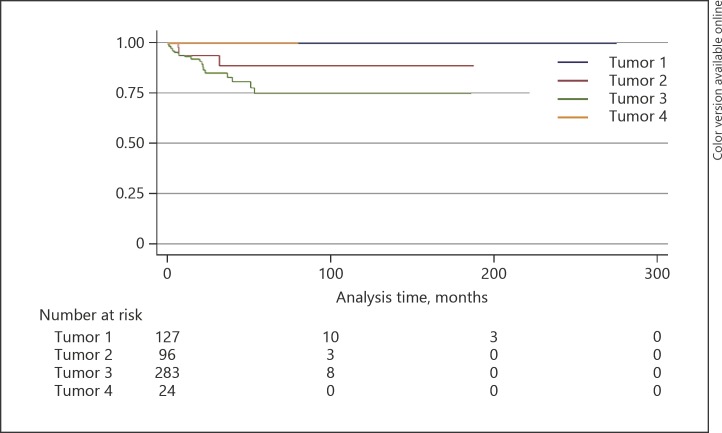

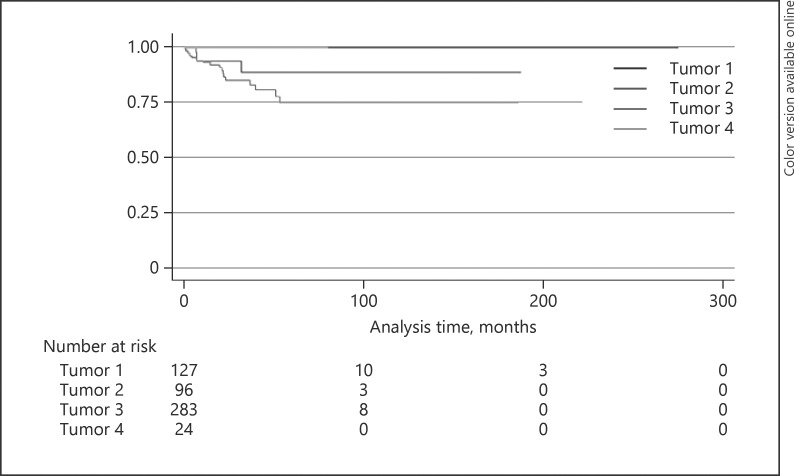

The 5-year Kaplan-Meier estimates for locoregional lymph node metastasis for SGC, BCC, SCC, and miscellaneous tumors were 43, 1, 22, and 47% (p < 0.0001), respectively (Fig. 2; Table 4), for distant metastasis 36, 0, 11, and 18% (p = 0.0002), respectively (Fig. 3; Table 4), and for metastasis-related death 25, 0, 11, and 16% (p = 0.003), respectively (Fig. 4; Table 4).

Fig. 2.

Kaplan-Meier analysis of lymph node metastasis. Tumor 1, basal cell carcinoma; tumor 2, squamous cell carcinoma; tumor 3, sebaceous gland carcinoma; tumor 4, miscellaneous tumor.

Table 4.

Kaplan-Meier estimates of malignant eyelid tumors

| Kaplan-Meier estimate | SGC (n = 285) | BCC (n = 128) | SCC (n = 99) | Miscellaneous (n = 24) | All cases (n = 536) | p value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Locoregional lymph node metastasis | ||||||

| 1 year | 11.07 (6.74–15.41) | 1.43 (0–4.21) | 8.08 (1.06–15.09) | 22.99 (2.81–43.17) | 9.05 (6.03–12.08) | <0.0001 |

| 3 years | 29.73 (20.18–39.28) | 1.43 (0–4.21) | 12.91 (1.54–24.29) | 33.99 (7.58–60.41) | 21.42 (15.08–27.76) | |

| 5 years | 42.55 (30.27–54.83) | 1.43 (0–4.21) | 21.62 (2.47–40.78) | 47.19 (15.85–78.53) | 31.28 (22.76–39.81) | |

| 10 years | 48.93 (32.86–65.01) | 1.43 (0–4.21) | 41.22 (4.99–77.45) | na | 36.93 (26.07–47.78) | |

| Distant metastasis | ||||||

| 1 year | 9.35 (5.28–13.42) | 0 | 5.91 (0–12.42) | 17.86 (0–36.71) | 7.09 (4.34–9.85) | 0.0002 |

| 3 years | 23.47 (14.54–32.41) | 0 | 10.86 (0–22.14) | 17.86 (0–36.71) | 16.01 (10.3–21.72) | |

| 5 years | 35.74 (23.20–48.29) | 0 | 10.86 (0–22.14) | 17.86 (0–36.71) | 22.96 (15.05–30.87) | |

| 10 years | 35.74 (23.20–48.29) | 0 | 10.86 (0–22.14) | na | 22.96 (15.05–30.87) | |

| Metastasis-related death | ||||||

| 1 year | 6.68 (3.15–10.22) | 0 | 6.05 (0–12.69) | 0 | 4.64 (2.39–6.89) | 0.003 |

| 3 years | 16.79 (8.85–24.73) | 0 | 10.99 (0–22.33) | 0 | 11.21 (6.23–16.18) | |

| 5 years | 24.88 (13.56–36.2) | 0 | 10.99 (0–22.33) | 0 | 15.66 (0.81–22.5) | |

| 10 years | 24.88 (13.56–36.2) | 0 | 10.99 (0–22.33) | na | 15.66 (0.81–22.5) | |

Values are % (95% confidence interval). na, not applicable.

Fig. 3.

Kaplan-Meier analysis of distant metastasis. Tumor 1, basal cell carcinoma; tumor 2, squamous cell carcinoma; tumor 3, sebaceous gland carcinoma; tumor 4, miscellaneous tumor.

Fig. 4.

Kaplan-Meier analysis of metastasis-related death. Tumor 1, basal cell carcinoma; tumor 2, squamous cell carcinoma; tumor 3, sebaceous gland carcinoma; tumor 4, miscellaneous tumor.

Discussion

BCC is the most common malignant eyelid tumor in the West [1, 2, 3, 4, 5]. In our series, SGC was the most common malignant eyelid tumor and this finding is consistent with some studies from other Asian countries including India, Japan, and Nepal [8, 15, 18, 19, 20, 21, 23, 24, 25, 26]. In our study, SGC (53%) was twice as common as BCC (24%) and 3 times more common than SCC (18%). Other studies from China, Korea, Singapore, Taiwan, and Thailand have shown BCC as the most common malignant eyelid tumor [7, 9, 11, 14, 16, 24, 27, 28, 29, 30, 31, 32, 33]. However, these studies have also shown a lower proportion of BCC and a higher proportion of SGC compared to the West [1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 7, 9, 11, 14, 16, 27, 28, 29, 30, 31, 32, 33] (Table 5). A study from Japan has shown SCC as the most common malignant eyelid tumor, constituting 48% of all eyelid malignancies [17], while in our study SCC was less common compared to SGC and BCC, constituting only 24% of all eyelid malignancies. Similar to our study, the majority of studies on malignant eyelid tumors in Asian Indians have shown that SGC is the most common eyelid malignancy (32–56%) in the Asian Indian population [15, 18, 19, 20, 21, 23, 25, 26]. Referral bias to the tertiary care referral institution may also play a role in this difference of eyelid tumor proportions. The referral of BCC would be much lower compared to other tumors since these tumors may have been more easily managed by referring physicians. In our study, the history of prior intervention was highest for miscellaneous tumors (67%), SCC (42%), and SGC (41%), suggestive of difficulty in managing these cases compared to BCC (18%).

Table 5.

Review of the literature on the proportion of eyelid tumors in Asians

| Author(s), year | Country | Patients with malignant eyelid tumors,n | BCC, % | SCC, % | SGC, % | Miscellaneous tumors, % | Most common malignant eyelid tumor |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Abeet al.[17], 1983 | Japan | 52 | 33 | 48 | 13 | 6 | SCC |

| Ni et al. [33], 1983 | China | 525 | 47 | 10 | 33 | 10 | BCC |

| Sihota et al. [15], 1996 | India | 178 | 30 | 30 | 33 | 7 | SGC |

| Abdi et al. [36], 1996 | India | 85 | 39 | 22 | 27 | 12 | BCC |

| Dai et al. [27], 1997 | China | 960 | 37 | 8 | 31 | 24 | BCC |

| Lee et al. [29], 2000 | Singapore | 325 | 84 | 3 | 10 | 2 | BCC |

| Wang et al. [16], 2003 | Taiwan | 127 | 62 | 9 | 24 | 5 | BCC |

| Changet al. [30], 2003 | Taiwan | 18 | 78 | 6 | 17 | 0 | BCC |

| Obata et al. [24], 2005 | Japan | 24 | 38 | 0 | 38 | 25 | BCC, SGC |

| Pornpanich et al. [28], 2005 | Thailand | 32 | 41 | 6 | 38 | 15 | BCC |

| Takamura et al. [34], 2005 | Japan | 38 | 40 | 11 | 29 | 21 | BCC |

| Lin et al. [14], 2006 | Taiwan | 1,121 | 65 | 13 | 8 | 14 | BCC |

| Xu et al. [12], 2008 | China | 363 | 41 | 5 | 39 | 15 | BCC |

| Kumar[8], 2010 | Nepal | 37 | 24 | 27 | 41 | 8 | SGC |

| Mak et al. [35], 2011 | China | 36 | 75 | 6 | 11 | 8 | BCC |

| Kaleet al. [10], 2012 | India | 85 | 48 | 14 | 31 | 7 | BCC |

| Lim et al. [31], 2012 | Singapore | 333 | 82 | 4 | 11 | 5 | BCC |

| Wang et al. [7], 2013 | China and Korea | 75 | 48 | 9 | 29 | 15 | BCC |

| Hussainet al. [11], 2013 | Pakistan | 222 | 59 | 32 | 7 | 3 | BCC |

| Bagheri et al. [32], 2013 | Iran | 100 | 83 | 8 | 6 | 3 | BCC |

| Ho et al. [13], 2013 | China | 28 | 43 | 18 | 7 | 32 | BCC |

| Ramya et al. [21], 2014 | India | 24 | 27 | 22 | 41 | 10 | SGC |

| Krishnamurthy et al. [23], 2014 | India | 19 | 26 | 21 | 32 | 21 | SGC |

| Rathod et al. [25], 2015 | India | 39 | 41 | 10 | 41 | 8 | BCC, SGC |

| Huanget al. [9], 2015 | Taiwan | 227 | 58 | 10 | 21 | 11 | BCC |

| Karanet al. [20], 2016 | India | 9 | 33 | 11 | 56 | 0 | SGC |

| Mohanet al. [19], 2017 | India | 41 | 15 | 22 | 24 | 39 | SGC |

| Guptaet al. [18], 2017 | India | 9 | 22 | 11 | 44 | 22 | SGC |

| Jangir et al. [26], 2017 | India | 17 | 29 | 24 | 47 | 0 | SGC |

| Present study, 2018 | India | 536 | 18 | 24 | 53 | 4 | SGC |

BCC, basal cell carcinoma; SCC, squamous cell carcinoma; SGC, sebaceous gland carcinoma.

Malignant eyelid tumors occur more commonly in the elderly [1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17, 18, 19, 20, 21, 23, 24, 25, 26, 27, 28, 29, 30, 31, 32, 34, 35, 36]. In our series, the mean age at presentation of all malignant eyelid tumors was ≥50 years. The patients presenting with miscellaneous tumors (50 years) and SCC (55 years) were younger compared to those with SGC (58 years) and BCC (60 years). Female predominance of malignant eyelid tumors was noted in some studies, while male predominance or no predilection has also been reported [34]. In our study, though there was a slight female predilection, it was not statistically significant. The reason for female preponderance in our study is unknown, though it may be related to increased cosmetic concerns of eyelid disfigurement in females, resulting in a higher rate of doctor consult in females compared to males.

Periocular SGC most commonly arises in the upper eyelid, accounting for half to two thirds of cases due to a predominance of meibomian glands in the upper eyelid [1]. In our study, 59% of tumors arose from the upper eyelid. Female preponderance of SGC has been reported in previous studies [33, 37, 38], while few studies have shown a male preponderance [39]. In our study, there was a female predilection with a male:female ratio of 1: 1.5. A Chinese-American collaborative study on malignant eyelid tumors including 525 cases from China and 1,543 cases from the USA revealed a disparity between the frequencies of SGC in both populations, accounting for 33% in China and 2% in the USA [33]. Based on these findings, the authors proposed that the incidence of SGC is higher in the Asian population compared to Caucasians and this could be related to genetics and racial predisposition for SGC in Asians [33]. Subsequent studies from Asian countries have supported this theory. However, this theory of racial predilection may not be true. In a retrospective study of 1,349 cases from a US-based population registry, the incidence of SGC was 2.03 cases per 1000,000 population in Whites versus 1.07 cases per 1,000,000 population in Asian/Pacific Islanders versus 0.48 per 1,000,000 population in Blacks, suggestive of a lack of racial predilection of SGC [39]. In Asians, SGC accounts for a higher proportion of eyelid malignancies, similar to our study, but this is not due to a higher incidence of SGC but to a relative lack of other malignant eyelid tumors [39]. Asians with malignant eyelid tumors are 6.21 times (range, 3.8–10.1) more likely to have SGC compared to non-Asians [39].

Overall, BCC is the most common malignant eyelid tumor in the world [1, 40], with a male predilection [41]. However, it has been reported that eyelid BCC is more common in young females (< 50 years) [39]. In our study, BCC was more common in females across all age groups, with a male:female ratio of 1: 1.5. BCC is more common in the lower eyelid (50–66%), followed by medial canthus (13–30%), upper eyelid (15–16%), and lateral canthus (3–5%) [42, 43]. In our study, the most common tumor location was the lower eyelid (59%) and the tumor epicenter location in the medial canthus was less frequent at 10%. Pigmented BCC of the eyelid has been noted in 1–50% patients and was more common in patients with darker skin color [44, 45, 46]. Haye and Dufier [45] noted that pigmented BCC of the eyelid was 1% in a Parisian population and increased to 45% in a Mediterranean population, suggestive of increased incidence in a darker-skinned population. In our study, pigmented BCC was noted in 55% of cases.

Eyelid SCC is a disease of the elderly, with a mean age at presentation of 60 years, and has a male predilection [47]. However, in our study, the mean age at presentation of SCC was 55 years and the disease had a slight female preponderance with a male:female ratio of 1: 1.1. There was no preference for upper or lower eyelids. The occurrence of malignant melanoma and other eyelid tumors was rare in our series. However, younger patients (< 20 years of age) had a preponderance for non-SGC/BCC/SCC eyelid malignancies.

The recommended modality of treatment for all malignant eyelid tumors is wide excision biopsy under frozen section or Moh's micrographic surgery control. In our study, wide excision biopsy under frozen section was performed in all cases when the tumor was limited to the eyelid. Clinical misdiagnosis was more common with SCC and miscellaneous malignant eyelid tumors with a clinicopathological correlation of 46% for SCC and 38% for miscellaneous tumors. Eyelid SCC (85%) was commonly misdiagnosed as SGC, and the most common misdiagnosis of miscellaneous tumors was eyelid metastasis (29%). Locoregional tumor invasion (13%), locoregional lymph node metastasis (16%), tumor recurrence (21%), systemic metastasis (13%), and disease-related death (9%) were more common with SGC compared to SCC and BCC. These findings are comparable with other studies [1, 4, 37, 38, 39]. Locoregional lymph node metastasis was also more common with miscellaneous tumors (25%), including malignant melanoma (n = 2), Merkel cell carcinoma (n = 1), lymphoma (n = 1), metastasis (n = 1), and mucoepidermoid/adenosquamous carcinoma (n = 1).

In summary, the proportion of SGC is higher in Asian Indians compared to other malignant eyelid tumors. This finding differs from the Western population. SGC, malignant melanoma, and Merkel cell carcinoma are associated with poorer prognosis, with higher chances of locoregional lymph node and systemic metastasis compared to BCC and SCC. This finding is similar to studies from the Western population.

Statement of Ethics

This was a retrospective study conducted at the Operation Eyesight Universal Institute for Eye Cancer, LV Prasad Eye Institute, Hyderabad, India. Institutional review board approval was obtained.

Disclosure Statement

No conflicting relationship exists for any author.

Acknowledgments

Support was provided by The Operation Eyesight Universal Institute for Eye Cancer (S.K.) and the Hyderabad Eye Research Foundation (S.K.), Hyderabad, India. The funders had no role in the preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript.

References

- 1.Font RL, Croxatto JO, Rao NA, editors. In: Tumors of the Eye and Ocular Adnexa. Washington, DC: American Registry of Pathology, AFIP; 2006. Tumors of the eyelids. pp. 155–221. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Deprez M, Uffer S. Clinicopathological features of eyelid skin tumors. A retrospective study of 5504 cases and review of literature. Am J Dermatopathol. 2009 May;31((3)):256–62. doi: 10.1097/DAD.0b013e3181961861. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tesluk GC. Eyelid lesions: incidence and comparison of benign and malignant lesions. Ann Ophthalmol. 1985 Nov;17((11)):704–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Aurora AL, Blodi FC. Lesions of the eyelids: a clinicopathological study. Surv Ophthalmol. 1970;15:94–104. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cook BE, Jr, Bartley GB. Epidemiologic characteristics and clinical course of patients with malignant eyelid tumors in an incidence cohort in Olmsted County, Minnesota. Ophthalmology. 1999 Apr;106((4)):746–50. doi: 10.1016/S0161-6420(99)90161-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ni Z. [Histopathological classification of 3,510 cases with eyelid tumor] Zhonghua Yan Ke Za Zhi. 1996 Nov;32((6)):435–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wang CJ, Zhang HN, Wu H, Shi X, Xie JJ, He JJ, et al. Clinicopathologic features and prognostic factors of malignant eyelid tumors. Int J Ophthalmol. 2013 Aug;6((4)):442–7. doi: 10.3980/j.issn.2222-3959.2013.04.06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kumar R. Clinicopathologic study of malignant eyelid tumours. Clin Exp Optom. 2010 Jul;93((4)):224–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1444-0938.2010.00475.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Huang YY, Liang WY, Tsai CC, Kao SC, Yu WK, Kau HC, et al. Comparison of the clinical characteristics and outcome of benign and malignant eyelid tumors: an analysis of 4521 eyelid tumors in a tertiary medical center. BioMed Res Int. 2015;2015:453091. doi: 10.1155/2015/453091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kale SM, Patil SB, Khare N, Math M, Jain A, Jaiswal S. Clinicopathological analysis of eyelid malignancies - A review of 85 cases. Indian J Plast Surg. 2012 Jan;45((1)):22–8. doi: 10.4103/0970-0358.96572. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hussain I, Khan FM, Alam M, Khan BS. Clinicopathological analysis of malignant eyelid tumours in north-west Pakistan. J Pak Med Assoc. 2013 Jan;63((1)):25–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Xu XL, Li B, Sun XL, Li LQ, Ren RJ, Gao F, et al. Eyelid neoplasms in the Beijing Tongren Eye Centre between 1997 and 2006. Ophthalmic Surg Lasers Imaging. 2008 Sep-Oct;39((5)):367–72. doi: 10.3928/15428877-20080901-18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ho M, Liu DT, Chong KK, Ng HK, Lam DS. Eyelid tumours and pseudotumours in Hong Kong: a ten-year experience. Hong Kong Med J. 2013 Apr;19((2)):150–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lin HY, Cheng CY, Hsu WM, Kao WH, Chou P. Incidence of eyelid cancers in Taiwan: a 21-year review. Ophthalmology. 2006 Nov;113((11)):2101–7. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2006.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sihota R, Tandon K, Betharia SM, Arora R. Malignant eyelid tumors in an Indian population. Arch Ophthalmol. 1996 Jan;114((1)):108–9. doi: 10.1001/archopht.1996.01100130104031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wang JK, Liao SL, Jou JR, Lai PC, Kao SC, Hou PK, et al. Malignant eyelid tumours in Taiwan. Eye (Lond) 2003 Mar;17((2)):216–20. doi: 10.1038/sj.eye.6700231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Abe M, Ohnishi Y, Hara Y, Shinoda Y, Jingu K. Malignant tumor of the eyelid—clinical survey during 22-year period. Jpn J Ophthalmol. 1983;27((1)):175–84. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gupta P, Gupta RC, Khan L. Profile of eyelid malignancy in a Tertiary Health Care Center in North India. J Cancer Res Ther. 2017 Jul-Sep;13((3)):484–6. doi: 10.4103/0973-1482.183215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mohan BP, Letha V. Profile of eye lid lesions over a decade: a histopathological study from a tertiary care center in South India. Int J Adv Med. 2017;4((5)):1406–11. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Karan S, Nathani M, Khan T, Ireni S, Khader S. Clinicopathological study of eyelid tumors in Hyderabad - A review of 57 cases. J Med Appl Sci. 2016;6((2)):72–6. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ramya BS, Dayananda SB, Chinmayee JT, Raghupathi AR. Tumours of the eyelid-A histopathological study of 86 cases in a tertiary hospital. Int J Sci Res Pub. 2014;4:1–5. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Esmaeli B, Dutton JJ, Graue GF, et al. Eyelid Carcinoma. In: Edge SB, Greene FL, Byrd DR, et al., editors. Carcinoma of the Eyelid. In: AJCC Cancer Staging Manual. 8th ed. New York (NY): Springer; 2017. pp. pp. 779–85. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Krishnamurthy H, Tanushree V, Venkategowda HT, Archana S, Mobin G, Archana S, et al. Profile of eyelid tumors at tertiary care institute in Karnataka: A 5-Years Survey. J Evolut Med Dent Sci. 2014;3((50)):11818–32. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Obata H, Aoki Y, Kubota S, Kanai N, Tsuru T. [Incidence of benign and malignant lesions of eyelid and conjunctival tumors] Nippon Ganka Gakkai Zasshi. 2005 Sep;109((9)):573–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rathod A, Modini P, Kavitha T, Samir B. A clinicopathological study of eyelid tumours and its management at a tertiary eye care centre of Southern India. MRIMS J Health Sciences. 2015;3:54–8. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jangir MK, Kochar A, Khan NA, Jaju M. Profile of eyelid tumours: histopathological examination and relative frequency at tertiary centre in north-west Rajasthan. Delhi J Ophthalmol. 2017;28((2)):30–5. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Dai J, Sun X, Li B, Zheng B, Hu S, Li L, et al. [Histopathology studies on 8,673 cases of ocular adnexal hyperplastic lesions and tumors] Zhonghua Yan Ke Za Zhi. 1999 Jul;35((4)):258–61. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pornpanich K, Chindasub P. Eyelid tumors in Siriraj Hospital from 2000-2004. J Med Assoc Thai. 2005 Nov;88(Suppl 9):S11–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lee SB, Au Eong KG, Saw SM, Chan TK, Lee HP. Eye cancer incidence in Singapore. Br J Ophthalmol. 2000 Jul;84((7)):767–70. doi: 10.1136/bjo.84.7.767. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Chang CH, Chang SM, Lai YH, Huang J, Su MY, Wang HZ, et al. Eyelid tumors in southern Taiwan: a 5-year survey from a medical university. Kaohsiung J Med Sci. 2003 Nov;19((11)):549–54. doi: 10.1016/S1607-551X(09)70505-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lim VS, Amrith S. Declining incidence of eyelid cancers in Singapore over 13 years: population-based data from 1996 to 2008. Br J Ophthalmol. 2012 Dec;96((12)):1462–5. doi: 10.1136/bjophthalmol-2012-302032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bagheri A, Tavakoli M, Kanaani A, Zavareh RB, Esfandiari H, Aletaha M, et al. Eyelid masses: a 10-year survey from a tertiary eye hospital in Tehran. Middle East Afr J Ophthalmol. 2013 Jul-Sep;20((3)):187–92. doi: 10.4103/0974-9233.114788. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ni C, Searl SS, Kuo PK, Chu FR, Chong CS, Albert DM. Sebaceous cell carcinomas of the ocular adnexa. Int Ophthalmol Clin. 1982;22((1)):23–61. doi: 10.1097/00004397-198202210-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Takamura H, Yamashita H. Clinicopathological analysis of malignant eyelid tumor cases at Yamagata university hospital: statistical comparison of tumor incidence in Japan and in other countries. Jpn J Ophthalmol. 2005 Sep-Oct;49((5)):349–54. doi: 10.1007/s10384-005-0229-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mak ST, Wong AC, Io IY, Tse RK. Malignant eyelid tumors in Hong Kong 1997-2009. Jpn J Ophthalmol. 2011 Nov;55((6)):681–5. doi: 10.1007/s10384-011-0077-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Abdi U, Tyagi N, Maheshwari V, Gogi R, Tyagi SP. Tumours of eyelid: a clinicopathologic study. J Indian Med Assoc. 1996 Nov;94((11)):405–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Shields JA, Demirci H, Marr BP, Eagle RC, Jr, Shields CL. Sebaceous carcinoma of the ocular region: a review. Surv Ophthalmol. 2005 Mar-Apr;50((2)):103–22. doi: 10.1016/j.survophthal.2004.12.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kaliki S, Ayyar A, Dave TV, Ali MJ, Mishra DK, Naik MN. Sebaceous gland carcinoma of the eyelid: clinicopathological features and outcome in Asian Indians. Eye (Lond) 2015 Jul;29((7)):958–63. doi: 10.1038/eye.2015.79. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Dasgupta T, Wilson LD, Yu JB. A retrospective review of 1349 cases of sebaceous carcinoma. Cancer. 2009 Jan;115((1)):158–65. doi: 10.1002/cncr.23952. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Saleh GM, Desai P, Collin JR, Ives A, Jones T, Hussain B. Incidence of eyelid basal cell carcinoma in England: 2000-2010. Br J Ophthalmol. 2017 Feb;101((2)):209–12. doi: 10.1136/bjophthalmol-2015-308261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Gilbody JS, Aitken J, Green A. What causes basal cell carcinoma to be the commonest cancer? Aust J Public Health. 1994 Jun;18((2)):218–21. doi: 10.1111/j.1753-6405.1994.tb00231.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Allali J, D'Hermies F, Renard G. Basal cell carcinomas of the eyelids. Ophthalmologica. 2005 Mar-Apr;219((2)):57–71. doi: 10.1159/000083263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Loeffler M, Hornblass A. Characteristics and behavior of eyelid carcinoma (basal cell, squamous cell sebaceous gland, and malignant melanoma) Ophthalmic Surg. 1990 Jul;21((7)):513–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hornblass A, Stefano JA. Pigmented basal cell carcinoma of the eyelids. Am J Ophthalmol. 1981 Aug;92((2)):193–7. doi: 10.1016/0002-9394(81)90769-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Haye C, Dufier JL. [Pigmented epitheliomas of the eyelids] Arch Ophtalmol (Paris) 1976 Oct;36((10)):633–44. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Lin LK, Lee H, Chang E. Pigmented basal cell carcinoma of the eyelid in Hispanics. Clin Ophthalmol. 2008 Sep;2((3)):641–3. doi: 10.2147/opth.s2110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Wawrzynski J, Tudge I, Fitzgerald E, Collin R, Desai P, Emeriewen K, et al. Report on the incidence of squamous cell carcinomas affecting the eyelids in England over a 15-year period (2000-2014) Br J Ophthalmol. 2018 Jan;:bjophthalmol-2017-310956. doi: 10.1136/bjophthalmol-2017-310956. Epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]