Abstract

NADPH donates high energy electrons for antioxidant defense and reductive biosynthesis. Cytosolic NADP is recycled to NADPH by the oxidative pentose phosphate pathway (oxPPP), malic enzyme 1 (ME1) and isocitrate dehydrogenase 1 (IDH1). Here we show that any one of these routes can support cell growth, but the oxPPP is uniquely required to maintain a normal NADPH/NADP ratio, mammalian dihydrofolate reductase (DHFR) activity and folate metabolism. These findings are based on CRISPR deletions of glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase (G6PD, the committed oxPPP enzyme), ME1, IDH1, and combinations thereof in HCT116 colon cancer cells. Loss of G6PD results in high NADP, which induces compensatory increases in ME1 and IDH1 flux. But the high NADP inhibits dihydrofolate reductase (DHFR), resulting in impaired folate-mediated biosynthesis, which is reversed by recombinant expression of E. coli DHFR. Across different cancer cell lines, G6PD deletion produced consistent changes in folate-related metabolites, suggesting a general requirement for the oxPPP to support folate metabolism.

Introduction

The cofactor NADPH provides high-energy electrons for antioxidant defense and reductive biosynthesis. Consumption and production of NADPH is compartmentalized, with cytosolic NADPH used by enzymes including fatty acid synthase, ribonucleotide reductase, thioredoxin reductase, and glutathione reductase1,2. Regeneration of cytosolic NADPH from NADP occurs by three well-validated routes: malic enzyme 1 (ME1), isocitrate dehydrogenase 1 (IDH1), and the oxidative pentose phosphate pathway (oxPPP), in which NADPH is produced by both glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase (G6PD) and 6-phosphogluconate dehydrogenase (PGD) (Fig. 1a)3,4. Each of these enzymes is ubiquitously expressed across mammalian cells and tissues.

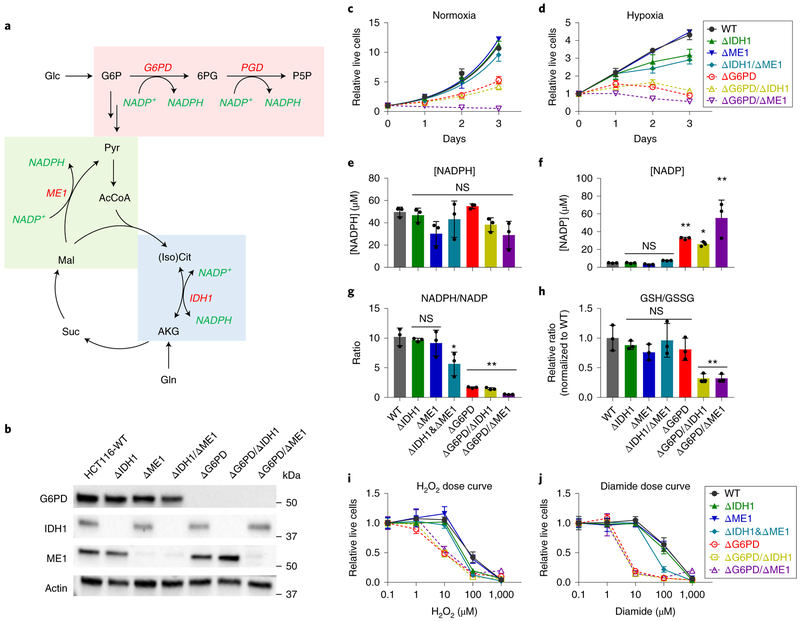

Figure 1. G6PD is required to maintain cell growth, NADPH/NADP ratio, and redox defense.

(a) Schematic of cytosolic NADPH production pathways. (b) Western blot for G6PD, IDH1, and ME1 protein levels in clonal HCT116 deletion cell lines. (c) Normoxic and (d) hypoxic growth (0.5% O2) of clonal HCT116 deletion cell lines lacking the indicated NADPH production enzymes in DMEM (plated at 2500 cells per well, n = 4). Note that ΔG6PD/ΔME1 cells die at low cell density, (e) NADPH and (f) NADP concentration. (g) NADPH/NADP ratio and (h) relative GSH/GSSG ratio (n = 3 for e-h). (i,j) Relative live cells after H2O2 or diamide treatment for 3 days, normalized to untreated cells (n = 6). Data are mean ± SD with n indicating the number of biological replicates. *p < 0.05 and **p < 0.01 by one-way ANOVA with Dunnett’s multiple comparison correction (see Supplementary Table 3 for exact P values).

G6PD is the best studied, largely because G6PD deficiency is the most common human enzyme defect5. Hypomorphic alleles of G6PD result in protection from malaria at the expense of red blood cell sensitivity to oxidative stressors6. Except for in red blood cells, which are unique in lacking mitochondria, hypomorphic alleles of G6PD are well tolerated, suggesting that adequate oxPPP flux is maintained despite the partially defective enzyme or that other NADPH production pathways can compensate for the decreased oxPPP. In mice, homozygous deletion of G6PD but not IDH1 or ME1 is embryonic lethal7–9.

To explore the physiological activity of metabolic enzymes, a classical approach is tracing using isotope-labeled carbon (13C or 14C)10–12. This approach has limited utility for ME1 and IDH1, as the same carbon transformation can be carried out by other isozymes that do not make NADPH. An alternative approach uses deuterium (2H) to probe more directly the source of NADPH’s redox active hydrogen13,14. Deuterium tracing studies suggest that, in most cultured mammalian cells, the oxPPP is the largest cytosolic NADPH producer1,15. But exceptions exist. For example, ME1 plays the largest role in differentiating adipocytes14. Moreover, deuterium tracing is complicated by the potential for loss of the 2H tracer via hydrogen-deuterium exchange and the significant deuterium kinetic isotope effect of many NADPH-producing enzymes, i.e. the greater mass of deuterium resulting in the reaction occurring more slowly with labeled substrate16. In addition, some estimates of cytosolic NADPH demand for fatty acid, proline, and deoxyribonucleotide synthesis and redox defense) have exceeded measurements of the combined production by the oxPPP, IDH1, and ME113. Due to these issues, it remains unclear whether cytosolic NADPH production in most cell types is fully accounted for by the oxPPP, IDH1, and ME1, or whether other NADPH production routes are significant.

One potential alternative NADPH source is folate metabolism13. The canonical function of folate metabolism is to provide activated one-carbon units to enable synthesis of thymidine, purines, and methionine17–20. The one-carbon carrier tetrahydrofolate (THF) is made from dihydrofolate (DHF) by the enzyme dihydrofolate reductase (DHFR). THF is then loaded with a one-carbon unit, usually from serine, to make methylene-THF. Oxidation of this one-carbon unit can make NADPH via two different reactions: (i) production of formyl-THF, a key substrate for purine synthesis, from methylene-THF and (ii) oxidation of formyl-THF’s one-carbon unit to CO2. In most cell types, folate metabolism does not make substantial cytosolic NADPH, although it can contribute substantially to mitochondrial NADPH via formyl-THF oxidation1,21,22.

Here we systematically genetically dissect cytosolic NADPH sources. We find that cancer cells can tolerate loss of any two of the three canonical cytosolic NADPH production routes. Among these, loss of the oxPPP due to G6PD knockout is most impactful, resulting in decreased NADPH/NADP ratio, oxidative stress sensitivity, and slow growth. Strikingly, the strongest metabolic effect of G6PD knockout does not relate to any of the canonical NADPH products, like fatty acids or glutathione. Instead, we observed profound defects in folate metabolism. These arise from impaired DHFR activity and are overcome by engineered expression of E. coli, reflecting a requirement for the oxPPP to maintain mammalian DHFR flux.

Results

G6PD is necessary and sufficient to maintain cytosolic NADPH/NADP homeostasis

To probe the importance of different cytosolic NADPH producing pathways, we targeted G6PD, PGD, ME1 and IDH1 genes for CRISPR-mediated deletion (Fig. 1a). HCT116 cells (k-Ras mutant colon cancer line) were transfected with a plasmid expressing Cas9 nickase, guide RNA, and a puromycin resistance marker23. After selection with puromycin, we obtained batch knockouts that were subjected to single cell cloning. Sequencing of the resulting clonal cells readily yielded ME1 and IDH1 knockout cell lines (> 20% of single colonies) (Fig. 1b, Supplementary Fig. 1a). These ΔIDH1 and ΔME1 cells grew equivalently to the parental cell line (Fig. 1c). For G6PD and PGD, in contrast, initial efforts failed to yield any knockout cells. With persistence, however, we were able to obtain clonal deletions, albeit with low frequency (< 2% of clones). Once obtained, the ΔG6PD cells were readily passaged, with a roughly 30% decrease in growth rate (Fig. 1b-c). ΔPGD cells, despite showing a greater growth defect, continued G6PD flux, which led to marked (and likely toxic) 6-phoshogluconate accumulation and eventual excretion of gluconate (Supplementary Fig. 1b, c). Accordingly, here we use G6PD but not PGD deletion to reflect functional oxPPP ablation, with G6PD growth promoting but not fully essential.

Given the viability of the single pathway deletions, we proceeded to make double deletion cell lines for G6PD, ME1, and IDH1 (Fig. 1b). Knockout of ME1 in the ΔIDH1 background resulted in viable cells with no overt growth defect. Knockout of IDH1 in the ΔG6PD background yielded viable cells that grew similarly to ΔG6PD (Fig. 1c). Knockout of ME1 in the ΔG6PD background resulted in profoundly growth impaired cells: While clonal ΔG6PD/ΔME1 cell lines were obtained and could be passaged by maintaining high cell density, they showed no growth in standard proliferation assay conditions. Hence, ME1 activity facilitates the growth of G6PD knockout cells.

NADP and NADPH were measured in the resulting single and double-deletion cell lines using LC-MS. NADPH concentration was maintained in all of the cell lines (Fig. 1e). NADP, however, rose in the ΔG6PD cells (but none of the other single deletions, including PGD), and more profoundly in the ΔG6PD/ΔME1 cells (Fig. 1f and Supplementary Fig. 1d). The decreased NADPH/NADP ratio (Fig. 1g) resulted in more oxidized glutathione and thus a decreased reduced/oxidized glutathione ratio in ΔG6PD/ΔIDH1 and ΔG6PD/ΔME1 cells (Fig. 1h and Supplementary Fig. 1e). All of the lines lacking G6PD were more sensitive to diamide and H2O2 (Fig. 1i,j). Both IDH1 and G6PD knockout cells, but not ME1 knockout cells, showed defective growth in a hypoxic environment, although the defect associated with G6PD loss was more severe (Fig. 1d). In The hypoxic G6PD knockout cells, addition of glutathione or N-acetyl cysteine mitigated these defects (Supplementary Fig. 1f). Overall, these findings are consistent with the G6PD deficient cells having impaired growth and oxidative defense because they fail to maintain a high NADPH/NADP ratio.

The oxPPP, ME1, and IDH1 are the only major cytosolic NADPH producers

Previous studies have yielded conflicting evidence as to whether there are significant contributors to cytosolic NADPH production beyond the oxPPP, IDH1, and ME11,13,15. We previously proposed that folate metabolism could potentially produce both cytosolic and mitochondrial NADPH13, although subsequent research showed that such production is typically limited to the mitochondrion except in mitochondrial folate pathway mutants21. Using 2H-serine to trace folate-dependent NADPH production, we confirmed minimal contribution in HCT116 cells (Supplementary Fig. 2a). To explore the possibility of other cytosolic NADPH production routes, we first attempted to make triple deletion ΔG6PD/ΔIDH1/ΔME1 cells by knocking out IDH1 (whose loss is well-tolerated in both wild-type and ΔG6PD cells) in ΔG6PD/ΔME1 cells. Although we did obtain a single cell line with heterozygous loss of one copy of IDH1, repeated efforts using CRISPR, puromycin selection, and single cell cloning never resulted in viable ΔG6PD/ΔME1/ΔIDH1 cells. Thus, HCT116 cells require at least one of the three major known cytosolic NADPH production routes.

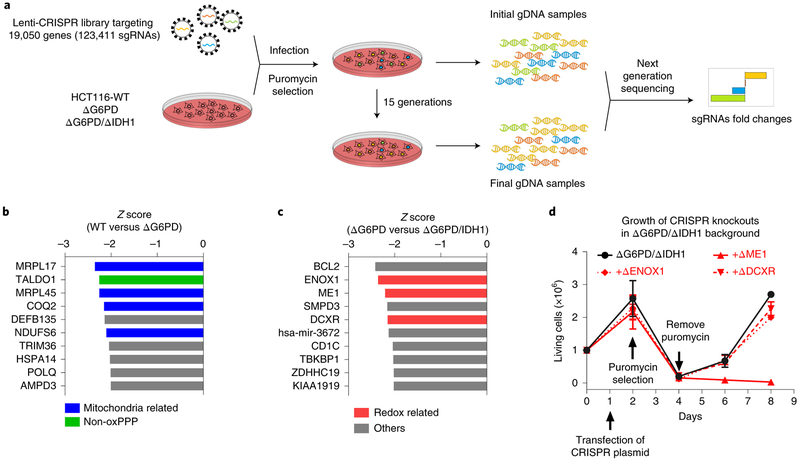

Despite not being sufficient on their own to support cell growth, other enzymes may contribute to HCT116’s cytosolic NADPH production. To search for potential unknown enzymes that might contribute to cytosolic NADPH homeostasis, we carried out a genome-scale CRISPR deletion screen for genes that are conditionally essential upon loss of G6PD or both G6PD and IDH1. This was done by infecting ΔG6PD cells or ΔG6PD/ΔIDH1 cells with GeCKOv2 Lenti-CRISPR library. After selection with puromycin, we allowed cells to passage for 15 doublings and collected gDNAs from the first and last generations of cells for sequencing (Fig. 2a). A challenge in such screens is the potential for clonal effects, i.e. genes that are conditionally essential in a particular single-cell clone, irrespective of the G6PD/IDH1 status. To address this, the screen was conducted in two independent ΔG6PD cell lines and two independent ΔG6PD/ΔIDH1 cell lines (Supplementary Fig. 2b-d). In the ΔG6PD background, a top hit was TALDO1 (Fig, 2b), a logical outcome given that the loss of the oxidative pentose phosphate pathway should render the non-oxidative pentose phosphate pathway essential for ribose production. Several mitochondria-related genes were also hits, suggesting that G6PD loss sensitizes to mitochondrial dysfunction (Fig. 2b). The screen did not yield any hits related to cytosolic NADPH.

Figure 2. CRISPR-based genetic screen identifies no cytosolic NADPH producers beyond oxPPP, ME1 and IDH1.

(a) Schematic of screen, which is based on comparing gene essentiality both in WT versus ΔG6PD knockout cells and in ΔG6PD versus ΔG6PD/ΔIDH1 knockout cells. (b) Top 10 conditional essential genes in ΔG6PD compared to WT HCT 116 cells based on Z score. (c) Top 10 conditional essential genes in ΔG6PD/ΔIDH1 compared to ΔG6PD cells based on Z score. (d) Cell growth of targeted pooled CRISPR knockout of DCXR, ENOX1 or ME1 in the ΔG6PD/ΔIDH1 background (mean ± SD, n = 4). After puromycin selection of transfected cells, only ME1, but not the other tested screen hits, was validated in the targeted knockout experiments.

In the ΔG6PD/ΔIDH1 background, the top three overall hits were BCL2, ENOX1, and ME1 (Fig. 2c). Thus, the screen effectively identified ME1 as being essential in cells already lacking G6PD and IDH1. BCL2 is presumably essential for preventing apoptosis in cells stressed by G6PD and IDH1 loss. ENOX1 encodes an enzyme involved in NAD(P)H oxidation at the plasma membrane, which appears to play a role in angiogenesis and protection of cancer from radiotherapy. Another top 10 hit was the DCXR gene, which encodes an NADPH-consuming xylulose reductase that makes the osmolyte xylitol in renal tubules. While ENOX1 and DCXR are annotated to consume, not make, NAD(P)H, we were curious if they might act in reverse to contribute to NADPH homeostasis in ΔG6PD/ΔIDH1 cells. In an effort to validate their importance for growth in the absence of G6PD and IDH1, we performed directed knockout of these two genes, as well as ME1, in ΔG6PD/ΔIDH1 cells (Fig. 2d). Successful knockout was validated by sequencing (Supplementary Fig. 2e). Loss of ENOX1 and DCXR were tolerated, whereas loss of ME1 was not (Fig. 2d). Thus, HCT116 cells require at least one of G6PD, IDH1, and ME1 to grow. Our failure to identify other NADPH producers in these genome-scale screens (or genes of unknown function that turned out to be NADPH producers) supports the perspective that HCT116 cells rely solely on G6PD, IDH1, and ME1 for cytosolic NADPH production.

Increased ME1 and IDH1 flux compensates for loss of G6PD

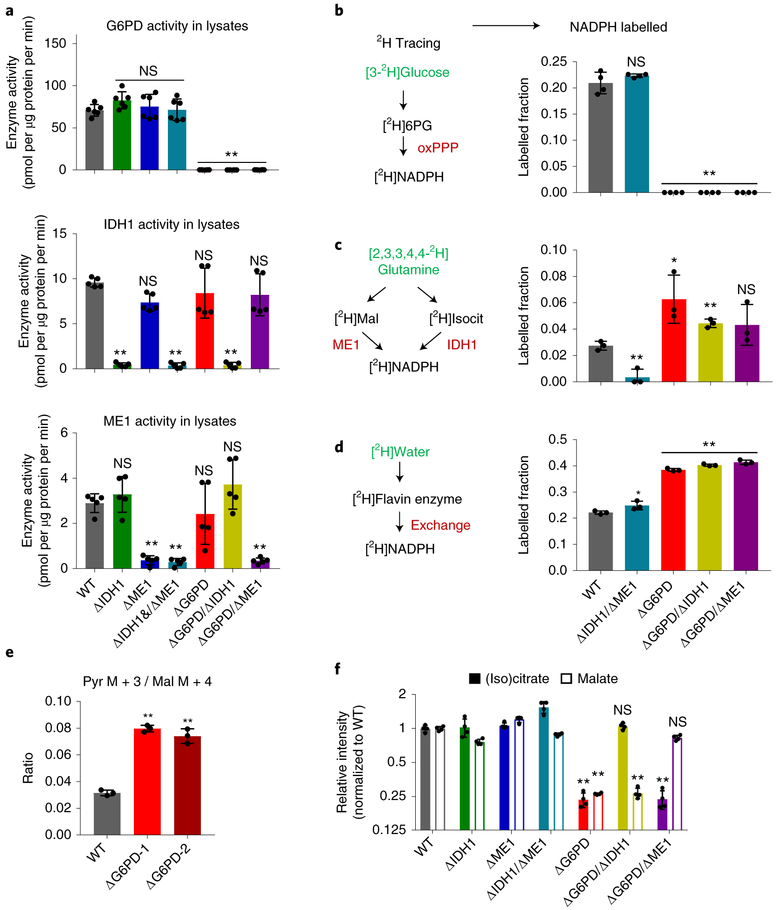

Having confirmed the absence of other substantial cytosolic NADPH producers, we investigated the mechanism by which loss of any two of the three major producers can be compensated. Western blots of lysates from single and double deletion cells showed clean knockout patterns consistent with their genetic background, but no compensatory expression of the remaining enzyme(s) (Fig. 1b). Similarly, enzymatic assays in cytosolic lysates revealed expected knockouts patterns without compensatory upregulation of other NADPH enzyme activities (Fig. 3a). Thus, there is no compensation for loss of G6PD, ME1, or IDH1 by enzyme induction.

Figure 3. Loss of G6PD induces ME1 and IDH1 flux without altering their enzyme activities.

(a) Enzyme activity of G6PD (top), IDH1 (middle) and ME1 (bottom) in clonal HCT116 deletion cell lysates (n = 6). (b) Labeling of NADPH’s redox active hydrogen in cells fed [3-2H]glucose to trace NADPH production from oxPPP (n = 3). (c) Labeling of NADPH’s redox active hydrogen in cells fed [2,3,3,4,4-2H]glutamine to trace NADPH production from ME1 and/or IDH1, which are not differentiated by this tracer (n = 3). (d) Labeling of NADPH’s redox active hydrogen in HCT116 mutants cultured in 45% D2O to trace H-D exchange of redox-active hydrogen nucleus (but not high-energy electrons) of NADPH with water (n = 3). (e) Ratio of pyruvate M+3 / malate M+4 from [U-13C]glutamine, reflecting the ratio of malic enzyme flux to glycolysis flux (n = 3). (f) Relative malate and (iso) citrate levels in NADPH gene deletion cell lines (n = 4). Data are mean ± SD with n indicating the number of biological replicates. *p < 0.05 and **p < 0.01 by one-way ANOVA with Dunnett’s multiple comparison correction (see Supplementary Table 3 for exact P values).

Even if enzyme levels and in vitro activities remain the same, fluxes may differ due to changes in substrate, product, and effector levels in cells. To probe NADPH production fluxes, we used deuterated tracers. [3-2H]glucose labels the redox-active hydrogen of NADPH at the PGD step of the oxPPP. As expected, this labeling is abolished by G6PD deletion (Fig. 3b). The labeling did not change with deletion of IDH1 and ME1, consistent with oxPPP flux exceeding IDH1 and ME1 flux even before loss of these enzymes. [2,3,3,4,4-2H]glutamine labels malate and isocitrate, and there by can label NADPH via ME1 and IDH1. We observed NADPH redox-active hydrogen labeling from [2,3,3,4,4-2H]glutamine in wild-type cells, which is lost with deletion of both ME1 and IDH1. Labeling increased with deletion of G6PD (Fig. 3c). These tracer studies show that, in HCT116 cells,the oxPPP is the default cytosolic NADPH production pathway. When this pathway is eliminated, IDH1 and ME1 compensate for G6PD loss.

The extent of NADPH active hydrogen labeling is far from complete in either [3-2H]glucose or [2,3,3,4,4-2H]glutamine. We recently discovered that a major source of NADPH’s redox-active hydrogen nucleus (but not its high-energy electrons) is H-D exchange with water15. This exchange occurs when NADPH’s redox-active hydrogen, normally held in a stable C-H bond, is transferred reversibly to a Flavin cofactor. The Flavin cofactor holds the redox-active hydrogen an N-H bond that quickly trades the hydrogen nucleus back and forth with water. The net effect is dilution of labeling from substrates like [3-2H]glucose and [2,3,3,4,4-2H]glutamine. To quantify such exchange, we used 2H-labeled water as a tracer. This exchange was not altered by ME1 and IDH1 deletion, but increased substantially with G6PD loss. The increased NADPH labeling from deuterated water upon G6PD knockout is consistent with increased NADP leading to greater Flavin enzyme reversibility: more NADP is available to accept Flavin’s redox-active hydrogen, which is labeled from the added D2O. Taking into consideration the extent of H-D exchange (see Methods), labeling from [3-2H]glucose is consistent with the oxPPP accounting for most of NADPH in wild-type HCT116 cells, and from [2,3,3,4,4-2H]glutamine is consistent with malic enzyme and IDH together accounting for most of NADPH in ΔG6PD cells, consistent with increased NADP availability driving ME1 and IDH1 flux.

As further confirmation of the increased malic enzyme flux in ΔG6PD cells, we employed [U-13C]glutamine tracer. Catabolism of [U-13C]glutamine generates [U-13C]malate. Malic enzyme activity can then generate [U-13C]pyruvate, with the fraction of [U-13C]pyruvate, normalized to the fraction of [U-13C]malate, indicative the relative flux of malic enzyme compared to glycolysis. These 13C-based measurements track total malic enzyme activity, without regard to the isozyme, compartment, or cofactor involved. Using this approach, we observed a 2-fold increase in total malic enzyme activity in the ΔG6PD clones (Fig. 3e).

If sufficiently substantial, increased ME1 and IDH1 flux might manifest as decreased concentrations of the enzymes’ substrates, malate and isocitrate. Citrate and isocitrate are isomers that are connected by the reversible aconitase reaction and are not readily distinguished by LC-MS. Strikingly, in G6PD knockout cells, we observed a 4-fold decrease in the intracellular concentrations of both (iso) citrate and malate (Fig. 3f). These concentration changes reflected increased consumption by ME1 and IDH1: malate depletion was reversed by ME1 knockout, and (iso) citrate depletion was reversed by IDH1 knockout. Thus, G6PD knockout triggers, likely through increased NADP rather than altered enzyme activities, sufficiently enhanced flux through ME1 and IDH1 as to deplete cellular malate and citrate.

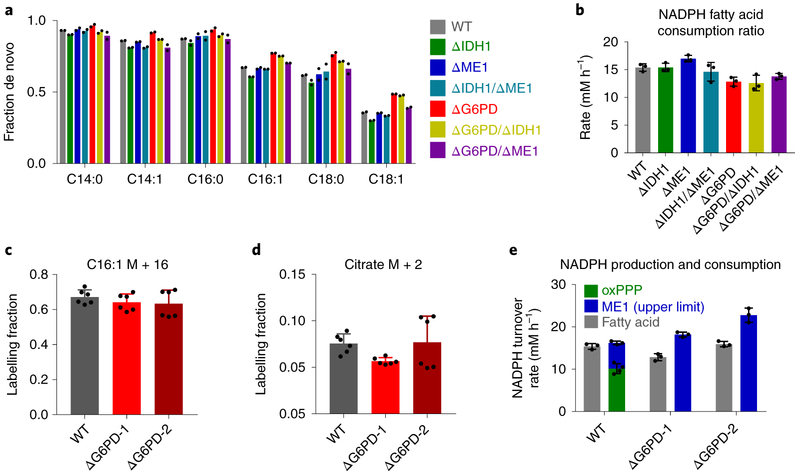

Fatty acid biosynthesis is maintained in G6PD knockout cells

In addition to turning on ME1 and IDH1, another way of coping with G6PD loss would be to decrease NADPH demand. Two major uses of NADPH in growing cultured cancer cells are deoxyribonucleotide synthesis and fatty acid synthesis. Deoxyribonucleotide synthesis is essential for cell growth. Fatty acid synthesis, however, can be decreased by scavenging serum fatty acids from the media or decreasing fatty acid oxidation flux. To measure fatty acid synthesis, we fed the various knockout cell lines [U-13C]glucose and monitored the extent of fatty acid labeling. De novo fatty acid synthesis can be distinguished from scavenging of serum fat by 13C incorporation. The fraction of fatty acids containing multiple 13C atoms, indicative of de novo synthesis, was similar across cell lines lacking different cytosolic NADPH producing enzymes (Fig. 4a and Supplementary Fig. 3). Moreover, the NADPH consumption to support fatty acid synthesis, calculated based on the abundances and extent of labeling of the different major fatty acid species, was also similar (Fig. 4b). To examine fatty acid oxidation in G6PD knockout cells, we fed cells [U-13C]palmitate (conjugated to BSA). Both wild type and knockout cells similarly assimilated the added labeled palmitate (C16:0) into palmitoleic acid (C16:1), indicating effective penetration of the tracer into both cell types (Fig. 4c). Moreover, in both cell types, labeling of TCA intermediates was similar, suggesting a similar rate of fatty acid oxidation (Fig. 4d). Based on the similar accumulation of de novo synthesized fatty acids from labeled glucose, and similar fatty acid oxidation rate, we conclude that NADPH usage for fatty acid synthesis is largely maintained in the G6PD knockout cells.

Figure 4. Fatty acid synthesis is maintained in HCT116 G6PD knockout cells.

(a) Fraction of different non-essential fatty acid species synthesized de novo based on extent of labeling from U-13C-glucose (for full labeling patterns, see Supplementary Fig. 3, n = 2). (b) NADPH consumption for fatty acid synthesis (n = 3). (c,d) Palmitoleic acid (C16:1) and citrate labeling fraction in cells fed 100 μM [U-13C]palmitate (conjugated to BSA) for 24 h (n = 6). (e) NADPH production by the oxPPP (measured using 14C-CO2 release from [1-14C] and [6-14C]glucose, n = 4) and the upper limit of production by ME1 (measured based on [U-13C-] lactate production from [U-13C]glutamine, n = 3) and NADPH consumption flux for fatty acid synthesis (n = 3). Data are mean ± SD with n indicating the number of biological replicates.

We were curious if the malic enzyme flux is sufficient to support this maintained rate of fatty acid synthesis. To this end, we used 13C-based measurements of malic enzyme flux. While not ME1 specific, total malic enzyme flux can be determined by comparing the fraction of pyruvate made by malicenzyme to pyruvate made via glycolysis, with the absolute glycolytic flux measured based on lactate secretion rate. We observed a basal malic enzyme flux of 6mM h−1, which increased by 12 – 14 mM h−1 in two separate ΔG6PD clones. This increase is similar to the absolute NADPH production flux of the oxPPP in wild-type cells, as measured by 14CO2 release from [1-14C]glucose versus [6-14C]glucose (10mM h−1). These values can also be compared to absolute NADPH flux required to support de novo fatty acid synthesis, as measured by the [U-13C]glucose labeling experiment, of 12 to 15 mM h−1 (Fig. 4e). Thus, increased flux through malic enzyme is sufficient to compensate for G6PD loss without compromising NADPH-dependent biosynthesis. The malic enzyme flux is driven by NADP accumulation. Accordingly, while NADPH production flux is maintained, the NADPH/NADP ratio is not.

Untargeted metabolomics of G6PD knockout cells reveals altered folate metabolism

To search for additional consequences of impaired cytosolic NADPH production, we next conducted untargeted metabolomics in the various HCT116 single and double deletion cell lines (Fig. 5a). G6PD deletion resulted in a stronger and broader change in the metabolome than either IDH1 or ME1 deletion. With a few exceptions, such as citrate being higher selectively in IDH1 knockout cells, similar direction of change was observed across the different cell lines lacking G6PD. Several of these changes were expected, such as strong depletion of 6-phosphogluconate, ribose phosphate, and octulose phosphate (which is made from ribose phosphate by aldolase). Substantial accumulation occurred for malonyl-CoA, especially in the cells lacking both G6PD and ME1, consistent with impairment of the reductive steps of fatty acid synthesis and thus buildup of the upstream substrate, which pushes the pathway forward.

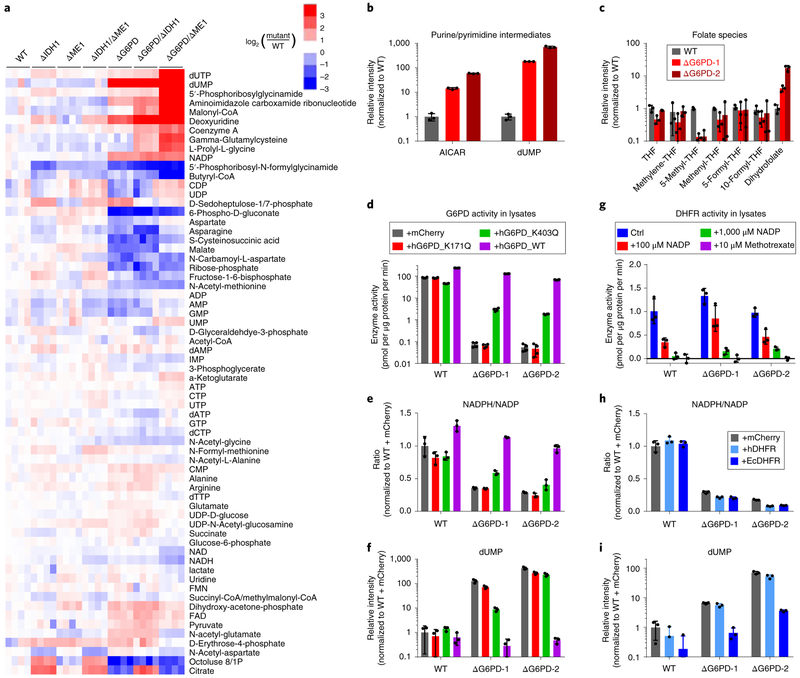

Figure 5. G6PD knockout cells are defective in folate metabolism due to impaired DHFR activity.

(a) Heat map showing intracellular levels of water-soluble metabolites in clonal HCT116 deletion cell lines. For each cell line,four individual biological replicates are shown, normalized to WT cells. (b) Relative levels of 1C-related purine/pyrimidine intermediates in ΔG6PD cells. (c) Relative levels of folate species in ΔG6PD cells, (d-f) G6PD lysate activity (d), relative NADPH/NADP ratio (e) and dUMP levels (f) in ΔG6PD cells with doxycycline-induced expression of mCherry control or catalytically inactive (K171Q), impaired (K403Q), or WT human G6PD. (g) DHFR enzyme activity in lysates from WT and ΔG6PD cells and its inhibition by NADP. (h,i) Relative NADPH/NADP ratio and dUMP levels in ΔG6PD cells with doxycycline-induced expression of mCherry control or human DHFR or E. coli DHFR. All results are mean ± SD with n = 3 biological replicates.

In addition to these changes that related to known roles of the pentose phosphate pathway, we observed striking changes in a set of metabolites related to one-carbon metabolism. The two main products of one-carbon metabolism in cell culture are purines and thymidine. Thymidylate synthase methylates dUMP using methylene-THF as the one-carbon donor. Although levels of the direct DNA precursor dTTP were maintained, we observed marked accumulation of dUMP, as well as its phosphorylated and dephosphorylated derivatives (dUTP, deoxyuridine) (Fig. 5a,b).

Purine biosynthesis involves two different reactions that consume formyl-THF. While purine end product levels were maintained, we observed strong accumulation of the substrates of both of the formyl-THF consuming reactions: 5’-phosphoribosylglycinamide (GAR) and 5-aminoimidazole-4-carboxamide ribonucleotide (AICAR) (Fig. 5a, b). In addition, the product of the first of these reactions, 5’-phosphoribosyl-N-formylglycinamide (FGAR), was strongly depleted. Collectively, these observations suggest an unanticipated dependence of one-carbon metabolism on the oxPPP.

To confirm that this unexpected dependence of one-carbon metabolism is a direct consequence of G6PD loss, we re-expressed wild type G6PD. This fully restored the knockout cells’ NADPH/NADP ratio, malate and (iso)citrate levels, and dUMP levels (Fig. 5d,e and Supplementary 4a). Consistent with the maintained G6PD flux and NADPH/NADP ratio in PGD knockout cells, these cells did not accumulate dUMP (Supplementary Fig. 4b). To investigate whether these changes relate to the catalytic activity of G6PD, we expressed two G6PD point mutants: a dimerization interface mutant with markedly impaired catalytic activity (K403Q) and a catalytically dead mutant (K171Q) (Fig. 5d and Supplementary Fig. 4c). The K403Q mutant modestly restored the NADPH/NADP ratio and dUMP level in ΔG6PD cells, while the catalytically dead K171Q mutant had no effect (Fig. 5e,f). To investigate the sufficiency of G6PD catalytic activity in reversing the knockout phenotype, we re-expressed yeast G6PD. The yeast enzyme expression achieved lysate activities less than one-tenth of those normally found in HCT116 cells (Supplementary Fig. 4d). Nevertheless, this partially normalized the NADPH/NADP ratio and dUMP levels (Supplementary Fig. 4e). Thus, rescue of the folate phenotype tracks with G6PD catalytic activity.

To explore why folate metabolism depends on G6PD, we fed ΔG6PD cells the soluble one-carbon donor formate. Formate provides a soluble source of 1C units and can normalize metabolite level changes due to 1C unit shortage. It cannot, however, compensate for impaired DHF reduction or blockade of folate - dependent biosynthetic enzymes. Formate did not mitigate the buildup of dUMP or AICAR in ΔG6PD cells (Supplementary Fig. 4f), suggesting that the defective metabolism was not related to an impaired supply of 1C units. To explore whether oxidative stress was the cause of the dysfunctional folate metabolism, we incubated wild-type cells with H2O2. This decreased NADPH and the NADPH/NADP ratio, but unlike G6PD deletion,did not significantly increase NADP or dUMP levels (Supplementary Fig. 4g). To further explore the mechanism of the one-carbon deficiency in the ΔG6PD cells, we measured cellular folate species. In ΔG6PD cells,the levels of all 1C-loaded THF species dropped 2-10 fold, with depletion of 5-methyl-THF, which is used for methionine biosynthesis, particularly profound. While THF levels were only modestly affected, dihydrofolate (DHF) increased 5-15 fold (Fig. 5c). DHF is a byproduct of thymidylate synthase and converted to THF by DHFR using NADPH as the reductant. A simple explanation for these findings is impairment of DHFR activity inΔG6PD cells.

We next investigated how G6PD deficiency may impair DHFR activity. Interestingly, DHFR protein levels and enzyme activity in lysates were comparable, if not higher, in both ΔG6PD clones (Fig. 5g and Supplementary Fig. 5a). We accordingly hypothesized that high NADP in ΔG6PD cells may inhibit DHFR. Consistent with this possibility, NADP impaired DHFR activity in cell lysates (Fig. 5g) and with recombinant human DHFR (Supplementary Fig. 5b).

We reasoned that mammalian DHFR might be particularly susceptible to product inhibition by NADP. To explore this, we engineered expression of both human and E. coli DHFR in ΔG6PD cells, to check for reversal of the one-carbon defects. Similar expression of both the human and E. coli enzyme was achieved based on western blotting of their FLAG-tag (Supplementary Fig. 5c). Based on lysate activity assays, the E. coli enzyme was more active, and this was particularly true in the presence of high NADP (Supplementary Fig. 5d). Strikingly, the E. coli but not human enzyme largely reversed dUMP accumulation (Fig. 5h,i). This occurred without any rescue of oxidative stress sensitivity or increased folate-mediated NADPH production (Supplementary Fig. 5e,f). Thus, HCT116 cells require the oxPPP to maintain low NADP, which is necessary for DHFR activity and thereby folate homeostasis24.

Generality of the dependence of folate metabolism on G6PD

We next explored the generality of the connection between G6PD, DHFR, and folate metabolism across cultured cell lines. Analysis of cell lysates from 12 different cancer cell lines revealed that the activity of G6PD exceeded IDH1 and ME1 in each line, with the extent of IDH1 and ME1 activity variable (Supplementary 6a,b). We then examined the impact of G6PD gene knockout in five cell lines: transformed human embryonic kidney cells (HEK293T), triple negative breast cancer cells (MDA-468), pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma cells (8988T), Ras-mutant lung adenocarcinoma cells (A549), and hepatocellular carcinoma cells (HepG2). Among these, A549 had the highest G6PD protein level and lysate activity, and 8988T the lowest.

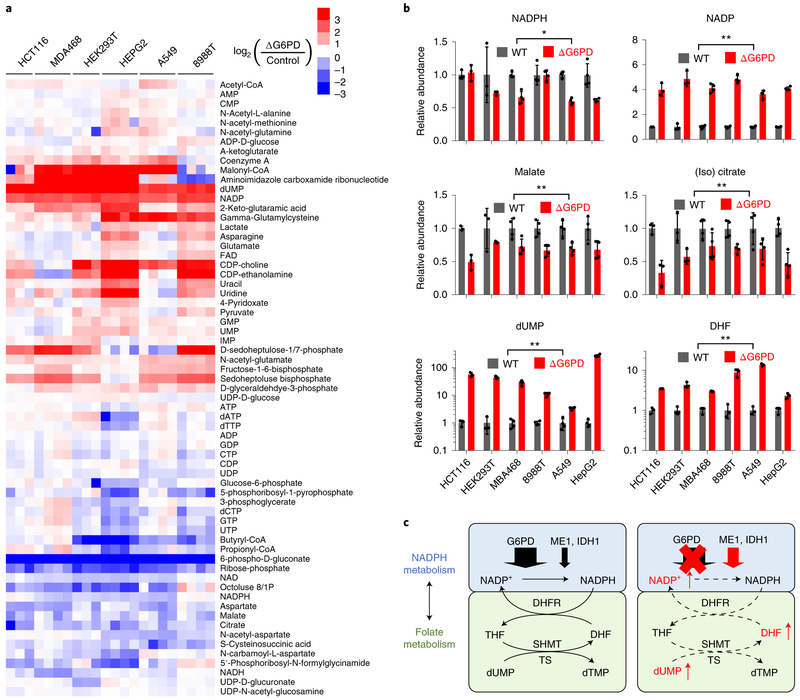

Cells were infected with lentivirus expressing CRISPR enzymes, puromycin resistance markers and sgRNA targeting either a control sequence or G6PD gene. After puromycin selection, we obtained batch G6PD knockouts, with substantial G6PD depletion based on immunoblotting (Supplementary Fig. 6c). Metabolomics analysis recapitulated the major metabolic changes observed in clonal HCT116 deletion cell lines (Fig. 6a). 6-phosphogluconate and ribose phosphate were strongly depleted (Fig. 6a), NADPH was nearly steady, NADP rose, and malate and (iso) citrate were moderately decreased consistent with their consumption by compensatory ME1 and IDH1 flux. Most strikingly, dUMP and DHF increased greatly (Fig. 6b). Thus, G6PD is required to maintain NADP and folate homeostasis (Fig. 6c).

Figure 6. Across cell lines, G6PD knockout consistently causes folate deficiency.

(a) Heat map showing intracellular levels of water-soluble metabolites in G6PD deletion cells. For each cell line, three or four individual biological replicates are shown, normalized to respective WT cells. (b) Relative levels of NADPH, NADP, malate, (iso)citrate, dUMP (n = 3 for HCT116 and HEK293T, n = 4 for others), and DHF (n = 3). Note that the dUMP and DHF panels are on a logarithmic Y-axis. (c) Schematic: G6PD deletion leads to accumulation of NADP, DHF and dUMP. Data are mean ± SD with n indicating the number of biological replicates, ns p ≥ 0.05, * p < 0.05 and ** p < 0.01 by two-tailed paired t-test assessing whether G6PD KO cell lines (as a group) differs from WT, with the geometric mean value for each cell type treated as one sample and n = 6 the number of cell lines (see Supplementary Table 3 for full statistical parameters.)

Discussion

NADPH’s high-energy electrons drive reductive biosynthesis and redox defense. Here we systematically examine in HCT116 cells the impact of losing each or combination of the major cytosolic NADPH production routes: oxPPP, IDH1 and ME1. While all three are expressed and can contribute to NADPH production, we observe a hierarchy of functional significance. The oxPPP is the largest contributor to NADPH production, and required to maintain a high NADPH/NADP ratio. IDH1 and ME1 appear to be “backups”, as (1) knocking them out did not impact growth in normoxia, yet either alone can support growth in the absence of oxPPP, with ME1 superior to IDH1 and (2) IDH1 or ME1 loss have minimal impact on sensitivity to oxidative stress. The primary role of the oxPPP seems to be shared across most cultured cancer cells, as (3) lysate enzyme activity measurements indicated that G6PD has higher NADPH production capacity than ME1 or IDH1 across 12 different cancer cell lines and (4) pooled G6PD knockouts of G6PD results in NADP build-up across 5 different cancer cell lines.

In vivo, the predominant cytosolic NADPH production pathway is likely to vary by tissue and cell type. Red blood cells depend on the oxPPP, as indicated by their sensitivity to hypomorphic G6PD alleles. This sensitivity may in part reflect their low expression of ME1 (despite strong expression of IDH1)25. Lipogenic cells may depend more on IDH1 or malic enzyme14,26,27. The importance of different NADPH production routes also presumably varies in respond to environmental conditions. Intriguingly, in HCT116 cells, IDH1 was required for optimal growth in hypoxia, despite the presence of functional oxPPP, consistent with IDH1 being particularly important in low oxygen, perhaps for its role in reductive carboxylation28–30. Understanding the tissue, cell-type, and environmental dependency of NADPH production routes is an important topic for ongoing study.

Are there additional biologically significant cytosolic NADPH producing enzymes? Previous 2H tracing studies in several transformed cell lines showed that 30%-50% of cytosolic NADPH labeled from the oxPPP and only small amounts by ME1 or IDH1, suggesting a missing source for at least half of NADPH. In an effort to uncover the responsible enzyme, we carried out a CRISPR-based genetic screen in HCT116 cells engineered for sensitivity to loss of backup NADPH pathways by knockout of G6PD ± IDH1. The screen successfully identified ME1, the positive control, but no other NADPH producing genes. While several hits were mitochondrial, they did not include any mitochondrial NADPH-producing enzymes, suggesting limited crosstalk between the cytosolic and mitochondrial NADPH pools. Consistent with the lack of other backups for making cytosolic NADPH, triple knockout of G6PD, ME1 and IDH1 was lethal. These findings align with recent evidence that the deficiency in NADPH labeling from the oxPPP, IDH1, and ME1 is due to Flavin enzyme-catalyzed H-D exchange with water, rather than an alternative route of NADP reduction15. Thus, although a substantial fraction of NADPH’s redox active hydrogen nucleus comes from H-D exchange with water, the high-energy electrons of cytosolic NADPH are almost exclusively from the oxPPP, ME1, and IDH1. It remains possible, however, that alternative pathways, either ALDH1L1 or yet to be characterized enzymes, are active in certain cell types or tissues.

In characterizing NADPH’s H-D exchange process using D2O labeling, we observed higher D2O labeling in G6PD deletion cells15. The extent of such labeling depends on the degree of equilibration between NADPH and Flavins. By decreasing the NADPH/NADP ratio, knockout of G6PD narrows the electrochemical potential difference between NADPH’sand Flavin’s electrons, leading to more complete equilibration and higher D2O labeling. In this manner, the extent of NADPH labeling from deuterated water serves as a surrogate for the NADP/NADPH ratio and rises with G6PD knockout.

Unexpectedly, a particularly sensitive cellular process to G6PD knockout proved to be folate metabolism. In ΔG6PD cells, impaired folate metabolism is evidenced by the accumulation of dUMP, GAR, and AICAR, the substrates of folate-dependent reactions in thymidine and purine biosynthesis. It is reinforced by direct measurements of DHF accumulation and depletion of active 1C-loaded THF species. The most affected THF species is 5-methyl-THF, whose production requires NADPH not only to make THF but also to reduce methylene-THF to 5-methyl-THF. 5-methyl-THF is a substrate for methionine synthase. In cell culture, this reaction is not functionally significant, due to methionine in media, but in vivo it maintains methylation potential.

The DHF accumulation suggests a mechanism in which G6PD knockout impairs DHFR activity. To provide evidence for this mechanism, we engineered expression of both human and E. coliDHFR, finding that only the latter could rescue the functional folate deficiency induced by G6PD loss. A likely mechanism by which G6PD might support human DHFR activity is maintenance of low levels of NADP, a product inhibitor of DHFR31. It is possible that the dependence of mammalian folate metabolism on G6PD reflects evolutionary selection for tight DHFR-NADP binding, which turns off DHFR in response to a disfavored NADPH/NADP ratio, thereby saving NADPH and/or decreasing nucleotide synthesis. We have previously shown that the antibiotic trimethoprim induces a cascade of enzyme inhibition in E. coli, starting with DHFR inhibition and propagating due to enzyme inhibition by accumulated DHF species32. Here a cascade of inhibition seems to be triggered initially by NADP accumulation, and to propagate via DHFR inhibition and accumulation of DHF species.

This is the second connection between NADPH and folate metabolism to be uncovered in the past few years. The first involved folate-dependent NADPH production1,13, which can occur via the ALDH1L1 enzyme in the cytosol or ALDH1L2 in the mitochondrion, which oxidize 10-formyl-THF to make NADPH, THF, and CO2 (Supplementary Fig. 7). In HCT116 cells, ALDH1L1 and ALDH1L2 enzyme expression is minimal and therefore the folate pathway does not contribute substantial NADPH1,19,21,33 While the biological significance of cytosolic folate-mediated NADPH production remains unclear, ALDH1L2 plays a key role in metastasis by enhancing tumor cell oxidative defense34.

What is the biological rationale for the connections between NADPH and folate metabolism? Balanced quantities of NADPH and 1C units are needed for growth and proliferation. In cases where 1C unit supply exceeds NADPH availability, ALDH1L enzymes can burn a 1C unit to make NADPH35. When this is insufficient to restore the NADPH/NADP ratio, high NADP impairs folate metabolism and thus nucleotide biosynthesis, halting proliferation to prioritize cell survival. In the cytosol, IDH1, ME1, and the oxPPP can all carry sufficient flux to meet the biosynthetic demand for NADPH. But only the oxPPP can do so while maintaining low NADP, rendering the oxPPP required for both redox and folate homeostasis.

Methods

Cell lines, growth conditions, and reagents.

HCT116 (CCL-247, lot#60506215) was purchased fresh from ATCC (Manassas, VA). HEK293T, MDA-MB-468, A549, HepG2, LnCap, MeWo, MDA-MB-231, U2OS, HT29, LN229 were from ATCC; 8988T, 8988S and KELLY cells were from DSMZ (Braunschweig, Germany). Cell lines were cultured in 5%CO2at 37 °C using DMEM (CellGro 10-017, Mediatech Inc., Manassas, VA) supplemented with 10%fetal bovine serum (F2442, Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) unless otherwise specified. Cas9 nickase and guide RNA expression plasmid pSpCasn(BB)-2A-Puro (48141), LentiCRISPR v2 (52961) and GeCKOv2 in lentiCRISPRv2 (1000000048), and plasmid containing E.coli DHFR sequence (20214) were purchased from Addgene (Cambridge, MA). cDNA of G6PD (MHS6278-202826068) was from Dharmacon Inc. cDNA of Human DHFR (RC200089) was purchased from OriGene Technologies. All primers were synthesized by IDT (Coralvi, IA). Standard laboratory chemicals were from Sigma.

Generation of CRISPR knockouts.

Clonal CRISPR knockouts were generated using protocol of Ran and colleagues23. Briefly, guide RNAs against exons of target genes (Supplementary Table 1) were cloned into a plasmid containing Cas9 nickase expression vector, and puromycin resistant genes. Cells were transiently transfected with plasmid targeting specific genes using Lipofectamine 3000 (Life Technologies) and selected for 48 hr with 2 μg mL−1 puromycin. After selection, cells were allowed to grow to confluence before plating in 96 wells for single cell selection. The single deletion cell lines lost puromycin resistance during single cell cloning, which was conducted in the absence of puromycin. Double gene knockouts ΔG6PD/ΔIDH1 and ΔG6PD/ΔME1 were generated from knocking out IDH1 or ME1 in ΔG6PD background. ΔIDHl/ΔME1 was generated from knocking out ME1 in ΔIDH1 cell background. ΔG6PD knockout cells were grown in RPMI medium + 20% FBS during the recovery and single cell selection period, as this yielded a greater fraction of clonal deletion cells than use of DMEM + 10% FBS. Functional gene deletion was confirmed by targeted genomic sequencing followed by western blotting.

Pool CRIPSR G6PD knockouts were generated with protocol of Sanjana and colleagues37. Briefly, sgRNAs targeting intragenic control or G6PD gene was cloned into LentiCRISPR v2 vector plasmid using the BsmBI restriction endonuclease (NEB R0580S). Lentivirus was prepared by transfecting 10 cm plate of 293T cells with mixture of 30 μL lipo3000 reagents, 6 μg prepared plasmid, 3 μg pMD2.G and 4.8 μg psPAX2 in 600 μOpti-MEM. Medium containing pooled lentivirus was collected two days after transfection, filtered with a PES filter (0.22 μm, Millipore), and stored in 1 mL aliquots at −80 °C. HCT116, HEK293T, MBA468, 8988T, A549 and HepG2 cells were transduced with the control or G6PD targeting lentiviral constructs and 4 μL−1 polybrene (Invitrogen). After 2 days of lentivirus transduction, cells were selected in l-2μg mL−1 puromycin for 3 days. Cell stocks were made after first confluence, and a new stock was used every 4 weeks. Functional gene deletion was confirmed by targeted genomic sequencing followed by western blotting.

CRISPR-based genetic screen.

The CRISPR-based genetic screen was carried out using human GeCKOv2 in lentiCRISPRv2 (Addgene, 1000000048)37. Two lentivirus libraries (A and B), each containing Cas9, puro resistance genes, and sgRNA targeting 19,050 gene were generated by transfecting 15 cm plate of 293T cells with mixture of 40 μL lipo3000 reagents, 10 μg GeCKOv2 library plasmid, 5 μg pMD2.G and 8 μg psPAX2 in 1000 μL Opti-MEM. Medium containing pooled lentivirus was collected two days after transfection, filtered with a PES filter (0.22 μm, Millipore), and stored in 5 mL aliquots at −80 °C. Two separate clones of HCT116 WT, ΔG6PD and ΔG6PD/ΔIDH1 cells were used. For each clone, two of 15 cm cultured plates with 15 × 106 cells each cultured in RPMI1640 medium supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum, were transduced with the above lentivirus libraries A and B separately. After 2 days of lentivirus transduction, cells were selected in 1.5 μg mL−1 puromycin for 2 days. Cells were then allowed to proliferate ~15 generations in RPMI1640 medium supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum. A minimum of 15 × 106 cells were kept during every passaging to maintain the diversity of guide RNA libraries.

Genomic DNA of the first and last generation cells (20-30× 106 cells each) were extracted (Qiagen, 13343). SgRNA inserts were amplified by PCR, purified by gel filtration, and sequenced on an Illumina HiSeq 2500 sequencer. Reads of each sgRNA were normalized to total reads within the sample. Results from two clones with same genetic background were pooled together to calculate z-score between different genetic backgrounds (Supplementary data).

Doxycycline-induced protein expression.

Lentiviral Tet-On 3G Inducible Expression Systems (Clontech) was used for expression of WT, K171Q or K403Q human G6PD38, yeast G6PD, human DHFR and E. coli DHFR, with synthetic DNA sequences containing a FLAG-tag. Gene of interests were cloned into pLVX- TRE3G vector through the NotI and MluI restriction sites.

Cells were first infected with lentivirus generated from pLVX-Tet3G (Clontech), and selected in 500 μg mL−1 G418 for 3 days to establish Tet-On 3G transactivator protein expression. Then cells were infected with lentivirus generated from empty pLVX-TRE3G vector or pLVX-TRE3G containing human G6PD, human DHFR, or E. coli DHFR. Cells were selected in 1.5 μg mL−1 puromycin for 2 days to incorporate gene of interest under the control of a TRE3G promoter. Protein expression was induced by incubating cells with 1 μg mL−1 doxycycline.

Metabolite profiling.

Cells were plated in 6-well plates with DMEM supplemented with 10% dialyzed fetal bovine serum (Sigma). Fresh medium was supplied 24 h and 2 h before extraction. Cells were 60-90 confluent at the time of extraction. Media was removed by aspiration and metabolism was immediately quenched (without any washing steps) and metabolites extracted by adding 500 μL −20 °C 40:40:20 acetonitrile : methanol: water containing 0.5% formic acid and incubating on ice for 1-2 min before neutralizing with 44 μL 15% ammonium bicarbonate. The cell extracts were then transferred to 1.5 mL tubes and stored at −20 °C for 30 min. The extracts were cleared by centrifuging at 16,000 × g for 10 minutes, and the supernatant was used for LC-MS analysis. LC-MS measurement was performed with a quadrupole orbitrap mass spectrometer (Q Exactive Plus, Thermo Fisher Scientific) operating in negative ion mode and coupled to hydrophilic interaction chromatography via electrospray ionization39. The scan range was m/z 73 to 1000. LC separation was achieved on a XBridge BEH Amide column (2.1 mm× 150 mm, 2.5μm particle size, 130 Å pore size;Waters) using a gradient of solve nt A (20 mM ammonium acetate + 20 mM ammonium hydroxide in 95:5 water:acetonitrile,pH 9.45) and solvent B (acetonitrile). Flow rate was 150 μl min−1. The gradient was: 0 min, 85% B; 2 min, 85% B; 3 min, 80% B; 5 min, 80% B; 6 min, 75% B; 7 min, 75% B; 8 min, 70% B; 9 min, 70% B; 10 min, 50% B; 12min, 50% B; 13 min, 25% B; 16 min, 25% B; 18 min,0% B; 23 min, 0% B; 24 min, 85% B; 30 min, 85% B. Peak identification and integration used MAVEN and ElMaven software, with compounds identified based on exact mass and retention time match to commercial standards40. After normalization to the average of WT samples, the resulting metabolites data were clustered using Cluster 3.0 software and plotted in Java Treeview.

Cell growth assay.

Cell growth was measured using the CyQUANT proliferation assay kit according to manufacturer’s instructions (Thermo). Briefly, cells were plated into 96 well plate at 2,500 - 5,000 cells per well with 150 μL DMEM supplemented with 10% FBS. Fluorescence intensity, which is proportional to the DNA content in the well, was read on consecutive days using a Synergy HT plate reader (BioTek Instruments). For hypoxic cell growth, the oxygen level was 0.5%. For oxidative stress cell growth, diamide or H2O2 was added during initial cell plating and cells were grown for the same duration thereafter.

In vitro enzyme activity assays.

G6PD, IDH1, ME1 enzyme activity were determined in a diaphrase- resazurin coupled assay. The cytosolic fraction of cell lysates was collected using subcellular protein fractionation kit according to manufacturer’s instruction (Thermo, 78840). The cytosolic fraction was added to assay buffer containing 50 mM Tris pH = 7.4, 5 mM MgCl2,1 mM resazurin, 0.25 mM NADP,0.1 U mL−1 diaphrase and 0.1 mg mL−1 bovine serum albumin. 1mM substrate (glucose-6-phosphate for G6PD, isocitrate for IDH1 and malate for ME1) was added to the above mixture to initiate reactions. Addition of glucose-6-phosphate can lead, via G6PD,to the production of 6-phosphogluconate and thus also NADPH production by PGD. Direct addition of 6-phosphogluconate to lysates resulted in <10% of the NADPH signal upon glucose-6-phosphate addition, suggesting that the present assay largely measures G6PD activity.

To measure DHFR enzyme activity, whole cell lysates were collected using CelLytic™ M (Sigma, C2978) according to manufacturer’s instruction. Lysate was mixed with assay buffer containing 50 mM K2HPO4/KH2PO4 pH 7.4, 10 mM BME and 0.05 mM DHF and methotrexate or NADP as indicated. 0.1 mM NADPH was added to the above mixture to initiate reactions. Activity was measured as the rate of decrease in NADPH fluorescence (in the absence of methotrexate) minus the decrease in the presence of methotrexate. Assay readout was by fluorescence for assays including diaphorase (530 nm excitation and 590 emission) and otherwise by absorption of NADPH at 340nm, using a Synergy HT plate reader (BioTek Instruments). Enzyme activities were quantified from the slope of the fluorescence or absorption changes, and the absolute rate was calculated based on the plateau which indicates full conversion of the limiting substrate. Measured enzyme activities were normalized to lysate protein concentration measured by BCA protein assay kit (Thermo, 23225).

Immunoblotting.

Cells were cultured to 50-90% confluency in 6 cm plates. For whole cell lysates, cells were washed with 4°C PBS once and lysed in RIPA buffer with phosphatase and protease inhibitors (Roche). Subcellular lysates were collected using subcellular protein fractionation kit according to manufacturer’s instruction (Thermo, 78840). Lysates were cleared by 10 min centrifugation at 16,000 g at 4°C. Samples were resolved by SDS-PAGE on precast gels (Bio-Rad) and transferred to a nitrocellulose membrane using the Trans-Blot Turbo system (Bio-Rad). Primary antibodies and horseradish peroxidase- conjugated secondary antibodies were used according to manufacturer’s directions. The ChemiDoc XRS+ system was used for image acquisition. Antibodies were used according to their manufacturer’s directions. Anti-β-actin (5125) and Flag-tag (2368) were obtained from cell Signaling Technologies (Danvers, MA). Anti-G6PD (ab993), ME1 (ab97445), IDH1 (EPR12296) and PGD (EPR6565) were obtained from Abcam Inc. (Cambridge, MA). Anti-DHFR (377091) and TS (390945) were obtained from Santa Cruz Biotechnology. Uncropped blots are provided in the Supplementary Information.

Isotope labeling.

The following isotopic tracers were purchased from the indicated sources: D2O, [U- 13C]glucose, [U-13C]glutamine, [2,3,3,4,4-2H]glutamine (Cambridge Isotope Laboratories); [U-2H]myristic acid (Sigma); [3-2H]glucose (Omicron Biochemicals). Isotope-labeled glucose, glutamine or D2O medium was prepared from phenol red– glucose-, glutamine-, sodium pyruvate–, sodium bicarbonate–free DMEM powder (Cellgro) supplemented with 3.7g L−1 sodium bicarbonate, 25 mM glucose, 4 mM glutamine and 10% dialyzed fetal bovine serum.

NADPH measurement and redox-active hydrogen calculation.

cells were plated in 6-well plates with DMEM supplemented with 10% dialyzed fetal bovine serum (Sigma) for 24 hours. Cells were fed with [3- 2H]glucose, [2,3,3,4,4-2H]glutamine or D2O medium for 2 h. NADPH and NADP labeling was extracted and measured as described in metabolite profiling section, except in the LC-MS analysis, an additional scan event with m/z window ranging from 650 to 760 was included.

The mass difference between 13Ciand 1 and 2H1 NADPH and NADP cannot be resolved using the Q Exactive PLUS. Therefore, the natural 13C abundance was corrected from the raw data. Over 2 h labeling duration, NADPH became M+1 and M+2 labeled, while NADP was only M+1 labeled. The labeling of the redox-active hydrogen of NADPH ([Active-H]) was determined using the following equation:

| (1) |

Correction for solvent exchange on active-H labeling was performed according to previous literature15. In brief, the extent of solvent exchange fraction can be quantified by dividing active-H labeling fraction from D2O to media D2O percentage. Then active-H labeling from [2,3,3,4,4-2H]glutamine or [3-2H]glucose can be corrected by normalizing to the un-exchanged fraction, or 1- solvent exchange fraction.

| (2) |

It should be noted that, the solvent exchange correction may be overestimated in cells that mainly use ME1 and IDH1 to make NADPH, because D2O not only labels NADPH directly through Flavin-dependent proton exchange, but also labels malate and isocitrate and thereby indirectly labels NADPH.

Folate measurements.

Folate species were measured according to previous literature41. In short, Folates were extracted from cultured cells with 50:50 H2O:MeOH containing 25 mM sodium ascorbate and 25 mM NH4OAc at pH 7. Cell extracts were heated to 60 °C for 5 min to fully denature proteins, and were cleared by centrifugation at 16000×g for 5 min at 4 °C. Supernatants were dried under N2 flow and resuspended in 450 μL potassium phosphate buffer (50 mM with 30 mM ascorbic acid and 0.5% 2- mercaptoethanol at pH 7) and 25 μL rat serum for 37 °C incubation for 2 h. To clean up samples before LC-MS, Bond Elut-PH SPE columns (Agilent) were conditioned with 1 mL MeOH and then with 1 mL wash buffer (30 mM ascorbic acid in 25 mM NH4OAc buffer at pH 4.0). After adjusting the samples to pH 4 with 7 μL of 40% formic acid solution at 4 °C,the samples were loaded onto the conditioned SPE columns, washed with 1 mL wash buffer, and subsequently eluted with 400 μL elution buffer (50:50 H2O:MeOH containing 0.5% 2-mercaptoethanol and 25 mM NH4OAc at pH 7). The eluate was dried down under N2 flow, resuspended into HPLC water, centrifuged to remove possible precipitate, kept at 4 °C in an autosampler, and analyzed by reverse phase LC-MS within 12h to minimize degradation.

Fatty acid synthesis measurements.

Cells were cultured in [U-13C]glucose DMEM medium supplemented with 10% dialyzed fetal bovine serum for 5 generations. Then the cells were plated in a 6- well plate for additional 2 days with [U-13C]glucose medium. Metabolism was quenched and cells were extracted using 90:10 MeOH : water containing 0.3 M KOH and 3.9 nmol of [U-2H]myristic acid internal standard. The extraction mixture was transferred into a 4 mL glass vial and incubated for 1 h at 80°C for saponification. The saponified fatty acids were acidified with 100 μL formic acid and extracted with 1 mL hexane into a 2 mL sample loading vial. Hexane was dried under N2 and the resulting fatty acids were re-dissolved into 50:50 MeOH : isopropanol for LC-MS analysis. LC-MS analysis was achieved as described previously39. Briefly, MS analysis was conducted on an Exactive orbitrap mass spectrometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific) operating in negative ion mode. LC separation was on reversed-phase ion-pairing chromatography on a Luna C8 column (150×2.0mm, 3μm particle size, 100 Å pore size; Phenomenex) with a gradient of solvent A (10 mM tributylamine + 15 mM acetic acid in 97:3 H2O : MeOH, pH 4.5) and solvent B (MeOH).

Fatty acid content per cell volume was calculated by first normalizing measured fatty acid intensity to the internal standard and then dividing by the measured packed cell volume (PCV). Fatty acid denovo synthesis fraction was the sum of specific 13C labeling fractions as described in the table below. 13C2 (i.e. M2) species were not included in the de novo synthesis fraction for C18 fatty acids, as we observed a substantial M2 peak consistent with elongation from pre-existing C16 species (Supplementary Fig. 3). NADPH consumption per fatty acid species was the product of de novo synthesis fraction and the number of NADPH used to synthesize that fatty acid species. Total NADPH consumption for fatty acid is the sum of NADPH consumption for 6 fatty acid species (Supplementary Table 2), which account for the most of fatty acid content in cultured cells. NADPH consumption rate for fatty acid synthesis was calculated as total NADPH consumed for fatty acid per cell volume multiply by cell proliferation rate.Cell proliferation rate is equal to ln (2) divided by doubling time.

Malic enzyme flux calculation.

Total malic enzyme flux, including all isozymes, was quantified on the basis of M+3 pyruvate labeling from [U-13C]glutamine relative to glycolysis flux as described previously14. Forward flux of TCA cycle from [U-13C]glutamine results in M+4 malate. Turning TCA cycle or reductive carboxylation of glutamine coupled to citrate lyase can produce M+3 malate. While M+4 malate produces M+3 pyruvate, isotopologues of M+3 malate produce half M+2 and half M+3 pyruvate. Spent media after 24 h of cell cultures were measured by YSI 2900 instrument to obtain the lactic secretion flux, which is approximate to glycolysis flux.

| (3) |

CO2 release and oxPPP flux.

The absolute oxPPP flux was quantified using 14CO2 release from [1- 14C]glucose and [6-14C]glucose as previously described 13. Briefly,cells were grown in 12.5-cm2tissue culture flasks with pH= 7.4 DMEM containing 6 g L−1 HEPES (D9805 US biological) and low bicarbonate (0.74 g L−1). 0.5 μCi mL−1 [l-14C]glucose or [6-14C]glucose was added to the medium and the flask was sealed with a rubber stopper with a center well (Kimble Chase) containing thick pieces of filter paper saturated with 150 μL 10 M KOH. Cells were incubated for 24 h. Metabolism was quenched and CO 2 was released by injecting 1 mL 3 M acetic acid through the stopper. The flask was incubated at 37°C for 1 hour to allow full absorption of released CO2 to the filter paper. The filter paper, KOH solution in the center well was transferred into a scintillation vial containing 10 mL liquid scintillation cocktail (PerkinElmer). 100 μL H2O was used to rinse the well and was combined with the same scintillation vial for scintillation counting. The signal was corrected for the percentage of radioactive tracer in the medium. OxPPP flux was calculated as follow:

| (4) |

Statistics and reproducibility.

Samples sizes, error bars, and p values are defined in each figure legend. For immunoblotting results or DNA sequencing results, we show representative data from multiple replicate: Figure 1b (n=3), Supplementary Figure 1a (n=3), Supplementary Figure 2e (n=2), Supplementary Figure 4c (n=2), Supplementary Figure 5a (n=2), Supplementary Figure 5c (n=2), Supplementary Figure 6c (n=2). Sample sizes, center values, error bars and statistical test methods are specified in the figure legends. All statistical calculations were performed using the software package GraphPad Prism 7.03.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgement.

We thank G. Ducker, J. Ghergurovich and X.Teng for scientific discussion and help. This work was supported by funding from the US National Institutes of Health (R01CA163591, P30CA072720, DP1DK113643, P30DK019525) and Department of Energy (DE-SC0018420, DE- SC0018260).

Footnotes

Competing interests. J.D.R. is a founder of Raze Therapeutics and advisor to L.E.A.F. pharmaceuticals. J.D.R. is a co-inventor on patent application owned by Princeton University covering diagnostics and therapeutics related to NADPH production by the 10-formyl-THF pathway (US20170000769).

Data availability. Source Data used to generate Figs 2a-c and Supplementary Figs 2b-d are provided as Supplementary Data 1. Uncropped versions of blots are provided in Supplementary Figures 8-13. Other data that support the findings of this study are available from the authors upon request.

Code availability. Matlab code used for matrix deconvolution for NADPH redox hydride is provided with manuscript. R code and R package used for natural abundance correction are publicly available from GitHub (https://github.com/XiaoyangSu/Isotope-Natural-Abundance-Correction and https://github.com/lparsons/accucor)36.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This Author Accepted Manuscript is a PDF file of an unedited peer-reviewed manuscript that has been accepted for publication but has not been copyedited or corrected. The official version of record that is published in the journal is kept up to date and so may therefore differ from this version.

Reference

- 1.Lewis CA et al. Tracing compartmentalized NADPH metabolism in the cytosol and mitochondria of mammalian cells. Mol Cell 55, 253–263 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lunt SY & Heiden MGV Aerobic Glycolysis: Meeting the Metabolic Requirements of Cell Proliferation. Annual Review of Cell and Developmental Biology 27, 441–464 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jiang P et al. p53 regulates biosynthesis through direct inactivation of glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase. Nature cell biology 13, 310–6 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jiang P, Du W, Mancuso A, Wellen KE & Yang X Reciprocal regulation of p53 and malic enzymes modulates metabolism and senescence. Nature 493, 689–693 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cappellini M & Fiorelli G Glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase deficiency. The Lancet 371, 64–74 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Howes RE et al. Spatial distribution of G6PD deficiency variants across malaria-endemic regions. Malaria journal 12, 418 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Al-Dwairi A, Pabona JMP, Simmen RCM & Simmen FA Cytosolic Malic Enzyme 1 (ME1) Mediates High Fat Diet-Induced Adiposity, Endocrine Profile, and Gastrointestinal Tract Proliferation-Associated Biomarkers in Male Mice. PLOS ONE 7, e46716 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Itsumi M et al. Idh1 protects murine hepatocytes from endotoxin-induced oxidative stress by regulating the intracellular NADP+/NADPH ratio. Cell Death and Differentiation 22, 1837–1845 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nicol CJ, Zielenski J, Tsui L-C & Wells PG An embryoprotective role for glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase in developmental oxidative stress and chemical teratogenesis. FASEB J 14, 111–127 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Buescher JM et al. A roadmap for interpreting 13C metabolite labeling patterns from cells. Current Opinion in Biotechnology 34, 189–201 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Katz J & Rognstad R The labeling of pentose phosphate from glucose-14C and estimation of the rates of transaldolase, transketolase, the contribution of the pentose cycle, and ribose phosphate synthesis. Biochemistry 6, 2227–2247 (1967). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Metallo CM, Walther JL & Stephanopoulos G Evaluation of 13C isotopic tracers for metabolic flux analysis in mammalian cells. Journal of Biotechnology 144, 167–174 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fan J et al. Quantitative flux analysis reveals folate-dependent NADPH production. Nature 510, 298–302 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Liu L et al. Malic enzyme tracers reveal hypoxia-induced switch in adipocyte NADPH pathway usage. Nat Chem Biol 12, 345–352 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zhang Z, Chen L, Liu L, Su X & Rabinowitz JD Chemical basis for deuterium labeling of fat and NADPH. J. Am. Chem. Soc (2017). doi: 10.1021/jacs.7b08012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Shreve DS & Levy HR Kinetic mechanism of glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase from the lactating rat mammary gland. Implications for regulation. J. Biol. Chem 255, 2670–2677 (1980). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ducker GS & Rabinowitz JD One-Carbon Metabolism in Health and Disease. Cell Metabolism 0, (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Locasale JW Serine, glycine and one-carbon units: cancer metabolism in full circle. Nature Reviews Cancer 13, 572–583 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tibbetts AS & Appling DR Compartmentalization of Mammalian Folate-Mediated One-Carbon Metabolism. Annual Review of Nutrition 30, 57–81 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yang M & Vousden KH Serine and one-carbon metabolism in cancer. Nat Rev Cancer 16, 650–662 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ducker GS et al. Reversal of Cytosolic One-Carbon Flux Compensates for Loss of the Mitochondrial Folate Pathway. Cell Metabolism 0, (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ye J et al. Serine Catabolism Regulates Mitochondrial Redox Control during Hypoxia. Cancer Discov 4, 1406–1417 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ran FA et al. Genome engineering using the CRISPR-Cas9 system. Nat. Protocols 8, 2281–2308 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Appleman JR et al. Unusual transient- and steady-state kinetic behavior is predicted by the kinetic scheme operational for recombinant human dihydrofolate reductase. J. Biol. Chem 265, 2740–2748 (1990). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nemkov T et al. Metabolism of Citrate and Other Carboxylic Acids in Erythrocytes As a Function of Oxygen Saturation and Refrigerated Storage. Front. Med 4, (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Flatt JP & Ball EG Studies on the Metabolism of Adipose Tissue XV. AN EVALUATION OF THE MAJOR PATHWAYS OF GLUCOSE CATABOLISM AS INFLUENCED BY INSULIN AND EPINEPHRINE. J. Biol. Chem 239, 675–685 (1964). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Koh H-J et al. Cytosolic NADP+-dependent isocitrate dehydrogenase plays a key role in lipid metabolism. J. Biol. Chem 279, 39968–39974 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Jiang L et al. Reductive carboxylation supports redox homeostasis during anchorage-independent growth. Nature 532, 255–258 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Metallo CM et al. Reductive glutamine metabolism by IDH1 mediates lipogenesis under hypoxia. Nature 481, 380 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wise DR et al. Hypoxia promotes isocitrate dehydrogenase-dependent carboxylation of α-ketoglutarate to citrate to support cell growth and viability. PNAS 108, 19611–19616 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Liu CT et al. Functional significance of evolving protein sequence in dihydrofolate reductase from bacteria to humans. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 110, 10159–10164 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kwon YK et al. A domino effect in antifolate drug action in Escherichia coli. Nature Chemical Biology 4, 602–608 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Field MS, Kamynina E, Watkins D, Rosenblatt DS & Stover PJ Human mutations in methylenetetrahydrofolate dehydrogenase 1 impair nuclear de novo thymidylate biosynthesis. PNAS 112, 400–405 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Piskounova E et al. Oxidative stress inhibits distant metastasis by human melanoma cells. Nature 527, nature15726 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zheng Y et al. Mitochondrial One-Carbon Pathway Supports Cytosolic Folate Integrity in Cancer Cells. Cell 175, 1546–1560.e17 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Su X, Lu W & Rabinowitz JD Metabolite Spectral Accuracy on Orbitraps. Anal. Chem 89, 5940–5948 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sanjana NE, Shalem O & Zhang F Improved vectors and genome-wide libraries for CRISPR screening. Nat Meth 11, 783–784 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wang Y-P et al. Regulation of G6PD acetylation by SIRT2 and KAT9 modulates NADPH homeostasis and cell survival during oxidative stress. The EMBO Journal 33, 1304–1320 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hui S et al. Glucose feeds the TCA cycle via circulating lactate. Nature 551, 115–118 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Melamud E, Vastag L & Rabinowitz JD Metabolomic Analysis and Visualization Engine for LC–MS Data. Anal. Chem 82, 9818–9826 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Chen L, Ducker GS, Lu W, Teng X & Rabinowitz JD An LC-MS chemical derivatization method for the measurement of five different one-carbon states of cellular tetrahydrofolate. Anal Bioanal Chem 409, 5955–5964 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.