Abstract

Gene expression is the fundamental driving force that coordinates normal cellular processes and adapts to dysfunctional conditions such as oncogenic development and progression. While transcription is the basal process of gene expression, RNA transcripts are both the templates that encode proteins as well as perform functions that directly regulate diverse cellular processes. All levels of gene expression require coordination to optimize available resources, but how global gene expression drives cancers or responds to disrupting oncogenic mutations is not understood. Post-transcriptional coordination is controlled by RNA regulons that are governed by RNA-binding proteins (RBPs) and noncoding RNAs (ncRNAs) that bind and regulate multiple overlapping groups of functionally related RNAs. RNA regulons have been demonstrated to affect many biological functions and diseases, and many examples are known to regulate protein production in cancer and immune cells. In this review, we discuss RNA regulons demonstrated to coordinate global post-transcriptional mechanisms in carcinogenesis and inflammation.

Discovery of multi-targeting of RNAs and RNA regulons

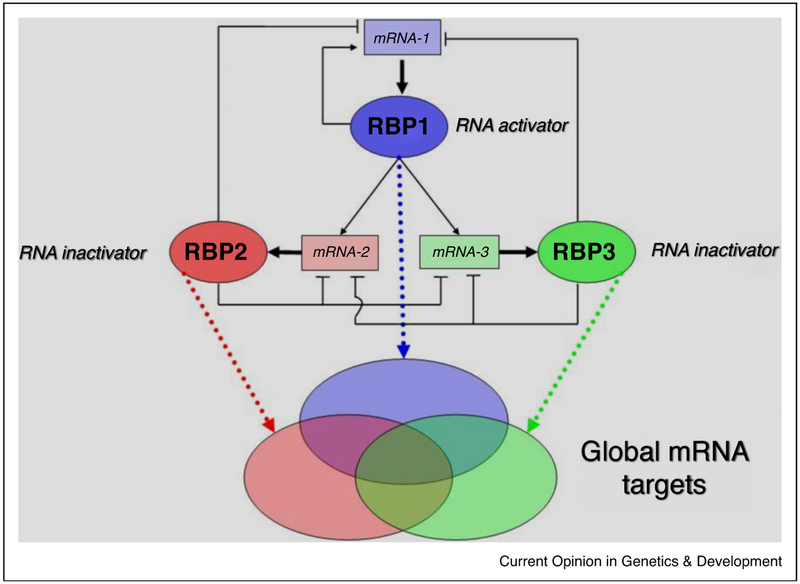

Historically, RNA binding discoveries involved one-on-one interactions between a putative RNA-binding protein and a single RNA that indicated a target site with a meaningful binding affinity. However, in the 1990s, Gao et al. generated a mRNA sequence library by devising an iterative mRNA selection procedure that used naturally occurring human brain RNAs, and they demonstrated that the RBP ELAVL2 (HuB) could bind to multiple mRNAs in vitro [1]. This study produced the first global mRNA targeting discovery and laid the groundwork for the post-transcriptional RNA regulon theory [2,3]. The dynamic RNA regulon model is one of overlapping and coordinated RBP–mRNA networks that balance post-transcriptional regulation as generalized in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Depiction of an interaction balance network of RNA-binding proteins. Three RBPs are exemplified that interact in a network with each other’s and their own messenger RNAs. Any changes in the expression levels of either RBP will bind and potentially modulate the larger population of mRNAs that each regulates globally. Activator refers to any positive molecular activation, while inactivator refers to negative repression of RNA target(s). Source: Reprinted from Mansfield and Keene, Biology of the Cell (2009) 101, 169–181.

The development of Ribonucleoprotein Immunoprecipitation (RIP) procedures coupled with microarrays or sequencing enabled the in vivo confirmation of multi-mRNA targeting for many RBPs from cell extracts. Various adaptations of RIPs performed with and without chemical or UV crosslinking have provided abundant information regarding global RNA targeting and RNA regulons [4]. Recently, RNA regulons have been traced back to the earliest metazoans, and the RNA Recognition type RBPs are more conserved than transcription factors in stem cells [5]. The adaptive advantage that conserved these ancient RBPs is attributed to the necessity to preserve RNA regulons that coordinate basic cell processes. This study, along with others, demonstrates the evolutionary and functional importance of RNA coordination in regulons [6–8].

RNA regulons in malignant progression

Cancer has traditionally been viewed as being driven by aberrant transcriptional regulation and signaling events, though, over the past several years, many RBPs and non-coding RNAs have emerged as critical players in tumor development [9,10•,11]. It is now recognized that RBPs influence cancer-related gene expression patterns by regulating many mRNAs encoding proto-oncogenes, growth factors, and cell cycle regulators. Mutations or alterations in RBP expression or localization can significantly impact gene expression programs. Indeed, global RNA expression levels of RBPs have been shown to be drastically different in cancer versus normal tissues and cells [12,13,14•]. However, mRNA abundance does not always correspond to protein levels due to changes in translation, post-translational modifications, and protein turnover. It is therefore important to experimentally validate the functional consequences of RBP misexpression in cancers. Here we discuss such validated examples of RBPs that coordinate cancer-related mRNA regulons to directly impact disease phenotypes. Though, it is important to point out that most cell culture models used in these experiments involve cell lines that are either immortalized or transformed. Our recent work suggests gene expression changes of RBPs occur during the immortalization of primary cells [14•]. Therefore, future studies that examine these RBPs in the context of primary cell immortalization will likely be relevant to oncogenesis.

HuR

ELAVL1 (HuR) is one of the most widely studied RRM–RBPs in the context of tumorigenesis. HuR typically stabilizes and/or promotes the translation of mRNA targets through preferentially binding to AU-rich elements (AREs), highly conserved repetitive sequences often found in 3′UTRs of normally labile mRNAs, including those encoding growth factors and oncogenes. Increased levels of cytoplasmic HuR have been linked to the increased stability of mRNA targets, and global analyses of HuR-bound mRNAs have provided evidence that HuR coordinates a diversity of RNA regulons that are remodeled during tumorigenesis. For example, comparison of low and high tumorigenic MCF7 cells demonstrated that HuR lost association with mRNAs encoding proteins involved in preventing tumorigenesis and gained association with mRNAs encoding cancer related mRNAs with increasing malignancy [15]. Similar findings were obtained through the comparison of immortalized MCF10A cells and cells transformed with MCT-1 oncogene, suggesting that HuR acts as a downstream effector of oncogenes [16]. Another study compared HuR targets in MCF7 and MDA-MB-231 cell lines and found that subsets of mRNAs involved in cancer-related pathways, including epithelial cell differentiation, vasculature development and signal transduction, were differentially regulated [17]. Also, activation of leukemia-derived T-cells resulted in coordinate changes in HuR RNPs [18]. The sum of these global studies suggests that HuR contributes to malignant progression by dynamically regulating cancer-related mRNA regulons.

In support of this idea, it has been extensively demonstrated that HuR is essential for maintaining cancer-related phenotypes. For example, a recent study demonstrated that HuR knockdown in activated microglia reduced invasion and resulted in altered expression levels for a group of 172 mRNAs enriched for those encoding proteins involved in proliferation, migration and inflammatory response [19•]. Changes in expression for many of the significantly changed mRNAs were demonstrated to be through the regulation of promoter activity, possibly through regulation of NF-kB. Another study revealed that HuR CRISPR knockout in a pancreatic cancer cell line reduced proliferation, increased cell death, altered the cell cycle, and reduced anchorage independent growth [20•]. HuR knockout cells were more sensitive to chemotherapy, PARP inhibitors and glucose deprivation and showed reduced tumor formation in mice [20•].

By contributing growth, survival, proangiogenic and ECM modifying factors, tumor associated inflammation may promote the development of malignancies through enabling the acquisition of essential hallmarks of cancer [21,22]. HuR has been reported to promote tumor-associated inflammation through the stabilization of many key inflammatory regulators, including COX-2, IL-2, IL-6, IL-8, IL-17, TNF-α, TGFβ and CXCL8 [23–27]. Paradoxically, HuR expression in myeloid cells protected mice from inflammation and colitis-associated cancer, and activated macrophages from these mice had higher levels of inflammatory mRNAs [28]. Furthermore, HuR overexpression in mouse macrophages induced translational silencing of several pro-inflammatory cytokines [29]. Thus, understanding the precise context-dependent roles of RBPs is critical.

CELF1

Another RRM–RBP emerging as a central regulator in malignancies is CELF1, a member of the CUG binding protein ELAV-like family of RBPs. CELF1 preferentially binds to GU-rich elements (GRE) primarily in introns and 3′UTRs. The GRE consensus sequence was originally identified as being a decay element in the 3′UTRs of many labile mRNAs in primary human T-cells [30], and, similar to AREs, GREs are evolutionarily conserved motifs that play important roles in post-transcriptional regulation of mRNAs involved in proliferation, apoptosis and cell motility [31]. A transposon based genetic screen in mice colorectal cancer identified CELF1 as a potential cancer driver [32], and depletion of CELF1 in several cancer cell lines reduced cell proliferation and increased protein levels of pro-apoptotic factors [33]. Recent work demonstrated that CELF1 is bound to different subsets of messages in primary T-cells compared to malignant T-cells [34•]. This altered binding led to the upregulation of mRNAs involved in cell proliferation, motility, and cell survival through decreased CELF1 binding, and the downregulation of cell cycle and apoptotic regulators through increased CELF1 binding [34•]. Additionally, CELF1 regulates an RNA regulon containing the mRNA encoding the signal recognition particles (SRP), and CELF1 knockdown resulted in higher SRP expression and reduced migration in vitro [35•].

Many mRNAs identified as being enriched in CELF1 RIP-chips [31] were also identified as enriched in HuR IPs [18], suggesting a potential mechanism of combinatorial regulation (Figure 1). Indeed, this has been demonstrated for individual mRNA targets in intestinal epithelium: HuR and CELF1 compete for binding to the same 3′UTR elements of Occludin [36], Myc [37], and E-cadherin [38], and regulate their translation in opposite directions. Although CELF1 normally acts as a negative regulator of expression, it has been shown to positively regulate expression levels in certain contexts. CELF1 increased survivin mRNA stability in esophageal cancer cells, contributing to apoptotic resistance [39]. It has also been demonstrated to promote translation of p21 in human fibroblasts and HeLa cells treated with the chemotherapeutic bortezomib [40]. A recent study from Joel Neilson’s lab reported a role for CELF1 in positively regulating the translation of ten mRNAs encoding proteins necessary and sufficient for the induction of an epithelial to mesenchymal transition [41••]. It is clear that the CELF1 PTR regulatory network is complex, and understanding the precise, context dependent mechanisms by which CELF1 regulates protein expression in combination with other RBPs is important.

ESRP

Alternative splicing, a process by which mRNAs can be differentially spliced, significantly broadens the potential number of gene products that can be produced through generating distinct mRNA isoforms that vary in both coding and non-coding regions. Not only can alternative splicing result in differences in mRNA stability and translation, but also localization, protein–protein interactions, post-translational modifications and ultimately function of the final protein product. Regulation of alternative splicing requires the recruitment of RBPs and formation of RBP–RNA complexes, the dysregulation of which is associated with many disease states, including cancer [42]. For example, epithelial splicing regulatory proteins 1 and 2 (ESRP1 and 2) are RRM–RBPs that regulate a broad splicing switch which, along with transcriptional and epigenetic regulation, mediate the transition between epithelial and mesenchymal cells, a process closely linked to metastatic dissemination [43•,44]. ESRP proteins were discovered in a screen to identify regulators of alternative splicing of epithelial and mesenchymal specific isoforms of the fibroblast growth factor receptor 2 (FGFR2) [45], and, since their discovery, it has been revealed that they regulate over 1000 epithelial related alternative splicing events in combination with other RBPs including RBM47, and Quaking [43•,44]. By contrast, the RBP RBFOX2 promotes a more mesenchymal alternative splicing signature [44], although in some cases it can cooperate with ESRPs [46]. The mechanisms that determine alternative splicing events associated with cancer progression are only just beginning to be elucidated. Understanding how alternative splicing is regulated during cancer progression could lead to new therapeutics and prognostic markers.

UNR/CSDE1

The importance and underlying mechanisms of RNA regulons as master switches of metastasis have recently begun to emerge. The most compelling example to date is the ‘Upstream of NRAS’ (UNR) pro-metastatic regulons discovered by Wurth and colleagues [47••]. The name ‘Upstream of NRas’ does not indicate a functional relationship between UNR and N-RAS, but instead describes UNRs chromosomal location. The UNR RBP, also called CSDE1, contains five cold-shock domains (CSD), each of which is a 70 amino acid binding domain that contains both an RNP1 octamer in beta strand #2 and an RNP2 hexamer in beta strand #3, which are characteristic of an RRM; yet the rest of the CSD motif/domain bears little similarity to an RRM [48]. CSD-containing proteins bind to RNA and DNA and are found in all three domains of life: Bacteria, Archaea and Eukaryota [48]. Studies using various biological systems indicate that CSD family members can regulate cellular proliferation, apoptosis, and differentiation, depending on the context, and UNR has been shown to regulate stability and translation of bound mRNA targets [47••,48–50].

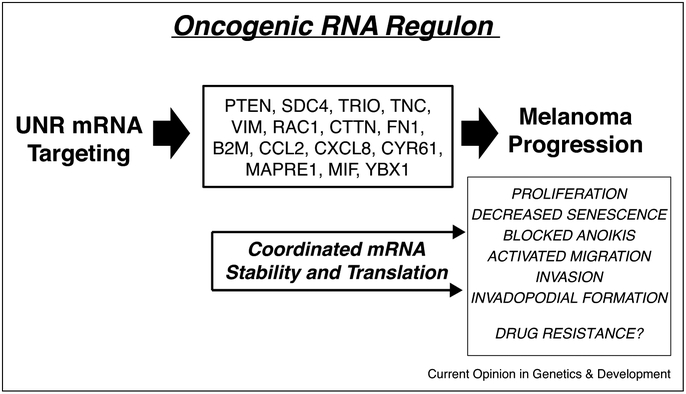

The pro-metastatic RNA regulon discovered by Wurth and colleagues drives melanoma invasion and metastasis by coordinating mRNA targets of UNR [47••]. UNR is overexpressed in melanoma cell lines and in metastatic samples from patients. Moreover, UNR is essential for anchorage independent growth, migration and invasion in vitro, as well as tumor formation and metastatic dissemination in mouse xenograft models. Using a combination of iCLIP-seq, RNA-seq, and ribosome profiling techniques, the authors identified subsets of invasive and metastasis-related mRNAs coordinated by UNR (Figure 2). Importantly, after UNR expression was depleted, the tumor-suppressive UNR targets, for example PTEN, were increased, and expression of tumor promoting UNR targets, including VIM and RAC1, were decreased, indicating that UNR can both positively and negatively influence gene expression and may therefore coordinate multiple mRNA regulons [47••]. Mechanistically, UNR can control RNA translation at the elongation or termination steps. Overall, UNR coordinates RNA regulons that act as metastatic switches in melanoma.

Figure 2.

Flow chart describing UNR RNA regulons discovered by Wurth et al. [47••]. Shown in the center box are known melanoma genes that are mRNA components of one or more regulons coordinately regulated by UNR. Through regulating translation of melanoma specific mRNAs UNR enhances melanoma progression.

GAIT

There is significant literature that indicates an intimate relationship between the immune system and cancers, and many RNA regulons, including those involved in cancer, are linked to inflammation [21,51,52]. One of the most interesting is the Gamma-Interferon (IFN-γ) Activated Inhibitor of Translation (GAIT) protein complex that forms a RNA regulon that was discovered in macrophage [53]. Structurally, GAIT is a heterotetrameric ribonucleoprotein complex consisting of NS1-associated protein 1 (NSAP1or hnRNP Q1), the glutamyl-prolyl tRNA synthetase (EPRS), glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH), and ribosomal protein RPL13a. Following activation of macrophages with IFN-γ, phosphorylation of the EPRS and L13a proteins releases them from the tRNA multisynthetase complex and the ribosomes, respectively, to initiate assembly of the GAIT complex, followed by addition of the NSAP1 and GAPDH components that, in turn, form a RNA regulon that binds to specific mRNA targets [53–55]. Each of the mRNA targets of the GAIT RNA regulon has a highly specific RNA stem-loop with a RNA recognition element in the 3′UTRs termed the ‘GAIT element.’ In the model by Fox and coworkers, the EPRS mRNA binding functions are modulated by interactions with the NSAP1 protein, while EPRS interactions with ribosomal protein L13a can modulate the initiation of translation [56]. Thus, competitive RNA binding interactions and the phosphorylation of EPRS and L13a can modulate the translation of messenger RNA subsets that encode inflammatory proteins such as cytokines and chemokines. Moreover, activation of macrophages by the GAIT RNA regulon provides coordinated feedback and feed-forward mechanisms (e.g. Figure 1) that balance protein production and subsequently modulates inflammation to sustain a chronic rather than aggressive response [53,57]. In conclusion, the GAIT RNA regulon is one of the most thoroughly studied examples of a ribonucleoprotein regulatory network that utilizes both feedback and feed-forward post-transcriptional and post-translational mechanisms to coordinate critical inflamma-tory functions related to cancer [58].

TTP

Tristetraprolin (TTP), a member of the ZFBP family, binds to AU-rich elements in the 3′UTRs of mRNAs that encode immunoreactive proteins and suppresses immunoreactivity by accelerating mRNA degradation [59]. TTP is thus hypothesized to provide a default mechanism to keep early response-type mRNAs encoding highly reactive cytokines from being produced during inappropriate times and conditions [60,61]. While the importance of TTP was originally linked to the immune system, more recent studies have recognized it as a tumor suppressor in multiple cancer types [59]. Tumor-associated inflammation requires the coordination of inflamma-tory proteins, the stability and translation of which are determined by RBPs. TTP has been demonstrated to coordinate RNA regulons consisting of such proteins, suppressing their expression and thereby acting as a tumor suppressor. For example, TTP levels were reduced in gastric cancer cell lines and patient tumors, and its expression inversely correlated with the expression of the pro-inflammatory cytokine IL-33 [62]. TTP expression inhibited migration and invasion in vitro and resulted in the formation of smaller tumors with reduced IL-33 expression in nude mice.

Another study demonstrated that TTP overexpression in transgenic mice had a protective effect against Myc-induced lymphomagenesis, and several ARE-containing genes, including cyclin D1 and the pro-inflammatory cytokine Fst1, had altered expression in B cells with and without TTP [63]. Furthermore, in tumor-associated macrophages TTP regulates cytokine and chemokine production through translational suppression [64]. Therefore, TTP may coordinate a tumor suppressive RNA regulon by degrading transcripts encoding both proliferation and pro-inflammatory cytokines and chemokines involved in malignancy, in both cancer cells themselves as well as in cells of the surrounding tumor microenvironment. Finally, it is interesting to note that HuR and TTP share many 3′UTR ARE-type mRNA targets [59]. Consistent with the RNA regulon model, over expression of HuR under certain circumstances can stabilize the mRNA encoding TTP that, in turn, activates degradation of the common mRNA targets (Figure 1).

Future implications of RNA regulons in cancer research

RBPs are crucial regulators of cancer traits. Given the increasing number of cancer RNA regulons that have been discovered in recent years, it is likely that this is a common and important mechanism of regulation in many, if not all, cancer types. In conventional cancer therapies, only one gene or pathway is targeted at a time. While irradiation, chemotherapy and immunotherapies are commonly used to treat most cancers, resistance remains a critical problem. Through modulating RNA regulons, therapeutically targeting master RBPs and ncRNAs would affect multiple genes, and likely multiple signaling pathways, at one time, reducing the potential for cancer cells to develop resistance through exploiting redundancies in cellular signaling. Future work should focus on understanding the global spectrum of RBP expression and functional outcome (i.e. translation of mRNAs contained within cancer regulons) during tumor initiation and malignant progression to prioritize discovery of small molecules that target RBPs.

Acknowledgements

We thank Matt Friedersdorf for helpful discussions related to the manuscript. We apologize to colleagues whose work and subjects were not cited given the length constrictions. Grant support National Institutes of Health, National Cancer Institute: R01CA157268, F31CA185892.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest statement

Nothing declared.

References and recommended reading

Papers of particular interest, published within the period of review, have been highlighted as:

• of special interest

•• of outstanding interest

- 1.Gao FB et al. : Selection of a subset of mRNAs from combinatorial 3′ untranslated region libraries using neuronal RNA-binding protein Hel-N1. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 1994, 91:11207–11211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Keene JD: The globalization of messenger RNA regulation. Natl Sci Rev 2014, 1:184–186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Blackinton JG, Keene JD: Post-transcriptional RNA regulons affecting cell cycle and proliferation. Semin Cell Dev Biol 2014, 34:44–54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wheeler EC, Van Nostrand EL, Yeo GW: Advances and challenges in the detection of transcriptome-wide protein– RNA interactions. Wiley Interdiscip Rev RNA 2017. 10.1002/wrna.1436. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Alie A et al. : The ancestral gene repertoire of animal stem cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2015, 112:E7093–E7100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jiang H, Guan W, Gu Z: Tinkering evolution of post-transcriptional RNA regulons: puf3p in fungi as an example. PLoS Genet 2010, 6:pe1001030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wilinski D et al. : Recurrent rewiring and emergence of RNA regulatory networks. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2017, 114:E2816–E2825. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hogan GJ, Brown PO, Herschlag D: Evolutionary conservation and diversification of Puf RNA binding proteins and their mRNA targets. PLoS Biol 2015, 13:pe1002307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wurth L, Gebauer F: RNA-binding proteins, multifaceted translational regulators in cancer. Biochim Biophys Acta 2015, 1849:881–886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.•.Ennajdaoui H et al. : IGF2BP3 modulates the interaction of invasion-associated transcripts with RISC. Cell Rep 2016, 15:1876–1883. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; This study demonstrates a cancer RNA regulon that promotes an invasive phenotype in pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma cells is driven by the IGF2BP3 RBP and a RISC/miR regulatory network of mRNA targets.

- 11.Nielsen FC, Hansen HT, Christiansen J: RNA assemblages orchestrate complex cellular processes. Bioessays 2016, 38:674–681. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Galante PA et al. : A comprehensive in silico expression analysis of RNA binding proteins in normal and tumor tissue: Identification of potential players in tumor formation. RNA Biol 2009, 6:426–433. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kechavarzi B, Janga SC: Dissecting the expression landscape of RNA-binding proteins in human cancers. Genome Biol 2014, 15:R14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.•.Bisogno LS, Keene JD: Analysis of post-transcriptional regulation during cancer progression using a donor-derived isogenic model of tumorigenesis. Methods 2017, 126:193–200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; This paper demonstrated that large global changes in expression of mRNAs encoding RBPs, many of which have been previously identified to play a role in cancer formation, occur during immortalization of primary human mammary epithelial cells. No additional expression changes occurred during malignant transformation. This suggests that post-transcriptional regulation by RBPs may be an early event during cancer initiation, and that these regulatory mechanisms may be missed in studies that begin with already immortalized cell lines.

- 15.Mazan-Mamczarz K et al. : Post-transcriptional gene regulation by HuR promotes a more tumorigenic phenotype. Oncogene 2008, 27:6151–6163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mazan-Mamczarz K et al. : Identification of transformation-related pathways in a breast epithelial cell model using a ribonomics approach. Cancer Res 2008, 68:7730–7735. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Calaluce R et al. : The RNA binding protein HuR differentially regulates unique subsets of mRNAs in estrogen receptor negative and estrogen receptor positive breast cancer. BMC Cancer 2010, 10:126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mukherjee N et al. : Coordinated posttranscriptional mRNA population dynamics during T-cell activation. Mol Syst Biol 2009, 5:288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.•.Matsye P et al. : HuR promotes the molecular signature and phenotype of activated microglia: implications for amyotrophic lateral sclerosis and other neurodegenerative diseases. Glia 2017, 65:945–963. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; This study used RNA-sequencing to compare LPS stimulated mouse primary microglia after treatment with HuR siRNA. mRNAs with altered expression were enriched for proliferation, migration and inflammatory response, although these changes in expression levels were demonstrated to be through the regulation of promoter activity, not mRNA stability.

- 20.•.Lal S et al. : CRISPR knockout of the HuR gene causes a xenograft lethal phenotype. Mol Cancer Res 2017, 15:696–707. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; HuR CRISPR knockout reduced proliferation, increased cell death, altered the cell cycle, and reduced anchorage independent growth in pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma cells. HuR knockout affected K-RAS activity, and the authors suggest that HuR may regulate a subset of prooncogenic mRNAs involved in RAS pathway activation.

- 21.Lin WW, Karin M: A cytokine-mediated link between innate immunity, inflammation, and cancer. J Clin Invest 2007, 117:1175–1183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hanahan D, Weinberg RA: Hallmarks of cancer: the next generation. Cell 2011, 144:646–674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dixon DA et al. : Altered expression of the mRNA stability factor HuR promotes cyclooxygenase-2 expression in colon cancer cells. J Clin Invest 2001, 108:1657–1665. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Dan C et al. : Modulation of TNF-alpha mRNA stability by human antigen R and miR181s in sepsis-induced immunoparalysis. EMBO Mol Med 2015, 7:140–157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Shi JX et al. : HuR post-transcriptionally regulates TNF-alpha-induced IL-6 expression in human pulmonary microvascular endothelial cells mainly via tristetraprolin. Respir Physiol Neurobiol 2012, 181:154–161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Abdelmohsen K, Gorospe M: Posttranscriptional regulation of cancer traits by HuR. Wiley Interdiscip Rev RNA 2010, 1:214–229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Srikantan S, Gorospe M: HuR function in disease. Front Biosci (Landmark Ed) 2012, 17:189–205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yiakouvaki A et al. : Myeloid cell expression of the RNA-binding protein HuR protects mice from pathologic inflammation and colorectal carcinogenesis. J Clin Invest 2012, 122:48–61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Katsanou V et al. : HuR as a negative posttranscriptional modulator in inflammation. Mol Cell 2005, 19:777–789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Vlasova IA et al. : Conserved GU-rich elements mediate mRNA decay by binding to CUG-binding protein 1. Mol Cell 2008, 29:263–270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lee JE et al. : Systematic analysis of cis-elements in unstable mRNAs demonstrates that CUGBP1 is a key regulator of mRNA decay in muscle cells. PLoS One 2010, 5:pe11201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Starr TK et al. : A transposon-based genetic screen in mice identifies genes altered in colorectal cancer. Science 2009, 323:1747–1750. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gao C et al. : Overexpression of CUGBP1 is associated with the progression of non-small cell lung cancer. Tumour Biol 2015, 36:4583–4589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.•.Bohjanen PR et al. : Altered CELF1 binding to target transcripts in malignant T cells. RNA 2015, 21:1757–1769. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; This study used RIP-chip to demonstrate that the CELF1 RBP is bound to different subsets of messages in primary T-cells compared to malignant T-cells. This altered binding led to the upregulation of mRNAs involved in cell proliferation, motility, and cell survival through decreased CELF1 binding, and the downregulation of cell cycle and apoptotic regulators through increased CELF1 binding.

- 35.•.Russo J et al. : The CELF1 RNA-binding protein regulates decay of signal recognition particle mRNAs and limits secretion in mouse myoblasts. PLoS One 2017, 12:e0170680. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; This study demonstrated that CELF1 regulates an RNA regulon containing the mRNA encoding the signal recognition particles (SRP). CELF1 knockdown resulted in higher SRP expression and reduced migration in vitro.

- 36.Yu TX et al. : Competitive binding of CUGBP1 and HuR to occludin mRNA controls its translation and modulates epithelial barrier function. Mol Biol Cell 2013, 24:85–99. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Liu L et al. : Competition between RNA-binding proteins CELF1 and HuR modulates MYC translation and intestinal epithelium renewal. Mol Biol Cell 2015, 26:1797–1810. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Yu TX et al. : CUGBP1 and HuR regulate E-cadherin translation by altering recruitment of E-cadherin mRNA to processing bodies and modulate epithelial barrier function. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 2016, 310:C54–C65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Chang ET et al. : The RNA-binding protein CUG-BP1 increases survivin expression in oesophageal cancer cells through enhanced mRNA stability. Biochem J 2012, 446:113–123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Gareau C et al. : p21(WAF1/CIP1) upregulation through the stress granule-associated protein CUGBP1 confers resistance to bortezomib-mediated apoptosis. PLoS One 2011, 6:pe20254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.••.Chaudhury A et al. : CELF1 is a central node in post-transcriptional regulatory programmes underlying EMT. Nat Commun 2016, 7:13362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; This exceedingly important study identified the CELF1 RBP as a positive translational regulator of an mRNA regulon consisting of at least 10 mRNAs necessary and sufficient for inducing an epithelial-tomesenchymal transition in MCF10A immortalized breast epithelial cells.

- 42.Oltean S, Bates DO: Hallmarks of alternative splicing in cancer. Oncogene 2014, 33:5311–5318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.•.Yang Y et al. : Determination of a comprehensive alternative splicing regulatory network and combinatorial regulation by key factors during the epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition. Mol Cell Biol 2016, 36:1704–1719. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; This paper defined alternative splicing networks coordinated by multiple RBPs, and revealed that ESRPs are major regulators of alternative splicing during the epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition, but that other RBPs, including RBM47, also contribute to EMT-specific alternative splicing events. Notably, this study highlights the importance of coordinated and combinatorial regulation by multiple RBPs during developmental and malignant transitions.

- 44.Shapiro IM et al. : An EMT-driven alternative splicing program occurs in human breast cancer and modulates cellular phenotype. PLoS Genet 2011, 7:pe1002218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Warzecha CC et al. : ESRP1 and ESRP2 are epithelial cell-type-specific regulators of FGFR2 splicing. Mol Cell 2009, 33:591–601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Dittmar KA et al. : Genome-wide determination of a broad ESRP-regulated posttranscriptional network by high-throughput sequencing. Mol Cell Biol 2012, 32:1468–1482. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.••.Wurth L et al. : UNR/CSDE1 drives a post-transcriptional program to promote melanoma invasion and metastasis. Cancer Cell 2016, 30:694–707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; This exceedingly important study identified a pro-metastatic RNA regulon coordinated by the UNR RBP. Using a combination of iCLIP-seq, RNA-seq, and ribosome profiling techniques, the authors identified subsets of invasive and metastasis-related mRNAs coordinated by UNR. This UNR mRNA regulon functions at the level of translation by controlling ribosomal association of subsets of specific mRNAs that, in turn, act as switches that determine non-metastatic from metastatic melanomas.

- 48.Mihailovich M et al. : Eukaryotic cold shock domain proteins: highly versatile regulators of gene expression. Bioessays 2010, 32:109–118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Dormoy-Raclet V et al. : Unr, a cytoplasmic RNA-binding protein with cold-shock domains, is involved in control of apoptosis in ES and HuH7 cells. Oncogene 2007, 26:2595–2605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Mihailovic M et al. : Widespread generation of alternative UTRs contributes to sex-specific RNA binding by UNR. RNA 2012, 18:53–64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Anderson P: Post-transcriptional regulons coordinate the initiation and resolution of inflammation. Nat Rev Immunol 2010, 10:24–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Yuan J, Muljo SA: Exploring the RNA world in hematopoietic cells through the lens of RNA-binding proteins. Immunol Rev 2013, 253:290–303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Ray PS, Fox PL: A post-transcriptional pathway represses monocyte VEGF-A expression and angiogenic activity. EMBO J 2007, 26:3360–3372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Sampath P et al. : Noncanonical function of glutamyl-prolyltRNA synthetase: gene-specific silencing of translation. Cell 2004, 119:195–208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Mazumder B, Sampath P, Fox PL: Translational control of ceruloplasmin gene expression: beyond the IRE. Biol Res 2006, 39:59–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Ray PS, Arif A, Fox PL: Macromolecular complexes as depots for releasable regulatory proteins. Trends Biochem Sci 2007, 32:158–164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Mukhopadhyay R et al. : DAPK–ZIPK–L13a axis constitutes a negative-feedback module regulating inflammatory gene expression. Mol Cell 2008, 32:371–382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Mukhopadhyay R et al. : The GAIT system: a gatekeeper of inflammatory gene expression. Trends Biochem Sci 2009, 34:324–331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Wang H et al. : Dysregulation of TTP and HuR plays an important role in cancers. Tumour Biol 2016, 37:14451–14461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Blackshear PJ: Tristetraprolin and other CCCH tandem zinc-finger proteins in the regulation of mRNA turnover. Biochem Soc Trans 2002, 30(Pt 6):945–952. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Lykke-Andersen J, Wagner E: Recruitment and activation of mRNA decay enzymes by two ARE-mediated decay activation domains in the proteins TTP and BRF-1. Genes Dev 2005, 19:351–361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Deng K et al. : Tristetraprolin inhibits gastric cancer progression through suppression of IL-33. Sci Rep 2016, 6: p24505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Rounbehler RJ et al. : Tristetraprolin impairs myc-induced lymphoma and abolishes the malignant state. Cell 2012, 150:563–574. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Kratochvill F et al. : Tristetraprolin limits inflammatory cytokine production in tumor-associated macrophages in an mRNA decay-independent manner. Cancer Res 2015, 75:3054–3064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]