Abstract

Background

Methane emissions from pigs account for 10% of total methane production from livestock in China. Methane emissions not only contribute to global warming, as it has 25 times the global warming potential (GWP) of CO2, but also represent approximately 0.1~3.3% of digestive energy loss. Methanogens also play an important role in maintaining the balance of the gut microbiome. The large intestines are the main habitat for the microbiome in pigs. Thus, to better understand the mechanism of methane production and mitigation, generic-specific and physio-ecological characteristics (including redox potential (Eh), pH and volatile fatty acids (VFAs)) and methanogens in the large intestine of pig were studied in this paper. Thirty DLY finishing pigs with the same diet and feeding conditions were selected for this experiment.

Result

A total of 219 clones were examined using the methyl coenzyme reductase subunit A gene (mcrA) and assigned to 43 operational taxonomic units (OTUs) based on a 97% species-level identity criterion. The family Methanobacteriaceae was the dominant methanogen in colonic digesta of finishing pigs, accounting for approximately 70.6% of the identified methanogens, and comprised mainly the genera Methanobrevibacter (57%) and Methanosphaera (14%). The order Methanomassiliicoccales, classified as an uncultured taxonomy, accounted for 15.07%. The methanogenic archaeon WGK1 and unclassified Methanomicrobiales belonging to the order of Methanomicrobiales accounted for 4.57 and 1.37%, respectively. The Eh was negative and within the range − 297.00~423.00 mV and the pH was within the range 5.04~6.97 in the large intestine. The populations of total methanogens and Methanobacteriales were stable in different parts of the large intestine according to real-time PCR.

Conclusion

The major methanogen in the large intestine of finishing pigs was Methanobrevibacter. The seventh order Methanomassiliicoccales and species Methanosphaera stadtmanae present in the large intestine of pigs might contribute to the transfer of hydrogen and fewer methane emissions. The redox potential (Eh) was higher in the large intestine of finishing pigs, which had a positive correlation with the population of Methanobacteriale.

Keywords: Methanogen, Redox potential, Large intestine, Pig

Background

With the progression of global warming, research has been increasingly focused on greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions from livestock. This is due to the large number of livestock in the world and the rapid growth in the number of livestock in developing countries in recent decades [1, 2]. Methane has a global warming potential (GWP) 25 times that of CO2, and represents substantial gross feed energy loss [3]. Although methane emissions from pigs are lower than those from ruminants, China farms the most pigs of any country in the world. In 2016, there were 0.435 billion pigs in China, accounting for 57% of the global total (data from National Bureau of Statistics of China). Methane emissions from pigs in China account for 10% of the total methane emissions from livestock [4]. The methane emissions from pigs also represent approximately 0.1~3.3% of digestive energy loss depending on the age and types of feed [5]. Therefore, reducing methane emissions from pigs is essential for controlling GHG emissions and improving feed efficiency.

Methane is produced by methanogens in the gut and manure, which mainly converts the substrates CO2 and H2 to methane [2]. Methanogens also play an important role in host health and have existed in the guts of pigs for millions of years [6, 7]. Some special methanogens exist in pigs; for example, Methanobrevibacter gottschalkii has been isolated from pig faeces [8]. Unlike the microbiota of ruminants, the microbiota of pigs, as monogastric animals, is mainly distributed in the hindgut [9]. Thus, to explore the mechanism of methane production, investigating the potential mitigation strategies from enteric fermentation, the mechanism of potential benefit for the host, the community composition and diversity of methanogenic archaea and the correlation with the parameters in the hindgut of pigs is essential. Methyl coenzyme Mreductase (mcrA) encodes that catalyses the terminal step in methane emissions and is ubiquitous among known methanogens [10]. Additionally, the relationship between mcrA transcription and methanogenesis has a positive correlation, meaning mcrA can be used as a biomarker for methanogenesis [11]. Some studies have investigated methanogens in the faeces of pigs or in vitro fermentation systems [12–14]. However, faeces and in vitro systems may not accurately represent the hindgut environment. Therefore, we investigated the diversity of methanogens in the hindgut of finishing pigs using an mcrA gene clone library and real-time PCR analysis. Because oxidation-reduction potential (Eh), pH and VFA production are regarded as the main factors affecting methanogen activity, these parameters were also determined to confirm the relationship between the gut environment and the diversity and community of methanogens in the hindgut of finishing pigs. Methanogens are an exclusively anaerobic microbiome that can only grow in low Eh environments. Otherwise, methanogens would be inhibited or unable to survive after oxygen exposure. Therefore, we will focus on the interaction between Eh and methanogens in this study.

Results

The diversity and community structure of methanogens in the hindgut of finishing pigs

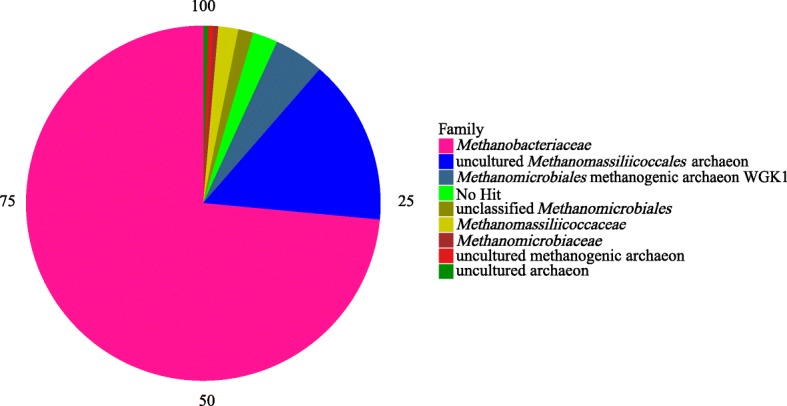

A total of 219 positive clones were obtained from the mcrA gene amplicons from the colonic digesta of finishing pigs (Table 1). The coverage of the library was 80%. The Chao1 index, Shannon index, and Simpson index of the library were 3.219, 97.6 and 0.077, respectively. Five sequences were not assigned to any methanogen taxa in the database (Table 1). The remaining 214 sequences were classified into 38 OTUs. Of these, 101 sequences belonged to Methanobrevibacter sp. WBY1. Of these, 26 and 24 sequences, were identified as Methanosphaera stadtmanae DSM 3091 and uncultured Methanomassiliicoccales archaeon, respectively. These three OTUs represented 70% of the valid sequences. The family Methanobacteriaceae was the dominant methanogen in the colonic digesta of finishing pigs, accounting for approximately 70.6%. Methanobacteriaceae mainly comprised the genera Methanobrevibacter (57%) and Methanosphaera (14%) (Table 1). The order Methanomassiliicoccales was identified as an uncultured taxonomy, accounting for 15.07% (Fig. 1). The methanogenic archaeon WGK1 and unclassified Methanomicrobiales belonging to the order of Methanomicrobiales accounted for 4.57 and 1.37%, respectively. We also identified the families Methanomassiliicoccaceae, Methanobacteriaceae, Methanomassiliicoccaceae, and Methanomicrobiaceae at less than 1%. At the species level, Methanobrevibacter sp. WBY1 (119 sequences), Methanobrevibacter smithii (2 sequences), Methanobrevibacter olleyae (1 sequence), and Methanosphaera stadtmanae DSM 3091 (31 sequences) were detected in the colonic digesta of finishing pigs (Table 1).

Table 1.

Operational taxonomic units (OTUs) of mcrA gene sequences from colonic digesta of finishing pigs

| OTUmcrAb | Clones | Nearest Taxon | % Sequence Identity |

|---|---|---|---|

| OTU0 | 1 | NHa | \ |

| OTU1 | 1 | Methanobrevibacter sp. WBY1 (EU919429.1) | 93 |

| OTU2 | 1 | NH | \ |

| OTU3 | 2 | Methanogenic archaeon WGK1 (GQ339874.1) | 99 |

| OTU4 | 1 | Uncultured Archaeon (AB557213.1) | 81 |

| OTU5 | 1 | Methanosphaera stadtmanae DSM 3091 (AJ584650.1) | 85 |

| OTU6 | 3 | Methanobrevibacter smithii (CP017803.1) | 95 |

| OTU7 | 1 | Methanobrevibacter sp. WBY1 (EU919429.1) | 92 |

| OTU8 | 2 | Methanosphaera stadtmanae DSM 3091 (AJ584650.1) | 84 |

| OTU9 | 101 | Methanobrevibacter sp. WBY1 (EU919429.1) | 97 |

| OTU10 | 1 | Methanobrevibacter olleyae (CP014265.1) | 92 |

| OTU11 | 1 | Candidatus Methanoplasma termitum (CP010070.1) | 88 |

| OTU12 | 2 | Candidatus Methanoplasma termitum (CP010070.1) | 84 |

| OTU13 | 4 | uncultured Methanobrevibacter sp. (JF973609.1) | 94 |

| OTU14 | 7 | Methanogenic archaeon WGK1 (GQ339874.1) | 85 |

| OTU15 | 1 | NH | \ |

| OTU16 | 1 | Methanobrevibacter sp. WBY1 (EU919429.1) | 96 |

| OTU17 | 1 | uncultured Methanomassiliicoccales archaeon (KT225447.1) | 82 |

| OTU18 | 1 | Methanobrevibacter sp. WBY1 (EU919429.1) | 96 |

| OTU19 | 1 | Methanobrevibacter sp. WBY1 (EU919429.1) | 92 |

| OTU20 | 1 | uncultured Methanomassiliicoccales archaeon (EF628111.1) | 81 |

| OTU21 | 3 | unclassified Methanomicrobiales (miscellaneous) (GQ339874.1) | 93 |

| OTU22 | 2 | Methanosphaera stadtmanae DSM 3091 (AJ584650.1) | 84 |

| OTU23 | 5 | Methanobrevibacter sp. WBY1 (EU919429.1) | 93 |

| OTU24 | 1 | uncultured Methanobrevibacter sp. (KC618377.1) | 96 |

| OTU25 | 1 | Candidatus Methanomethylophilus. (KC412011.1) | 97 |

| OTU26 | 1 | Methanobrevibacter sp. WBY1 (EU919429.1) | 90 |

| OTU27 | 1 | Methanobrevibacter sp. WBY1 (EU919429.1) | 84 |

| OTU28 | 1 | NH | \ |

| OTU29 | 1 | Methanobrevibacter sp. WBY1 (EU919429.1) | 85 |

| OTU30 | 1 | uncultured Methanoculleus sp. (AM284387.1) | 100 |

| OTU31 | 1 | Methanobrevibacter smithii (LT223564.1) | 88 |

| OTU32 | 6 | uncultured Methanomassiliicoccales archaeon (KT225454.1) | 86 |

| OTU33 | 26 | Methanosphaera stadtmanae DSM 3091 (AJ584650.1) | 88 |

| OTU34 | 1 | NH | \ |

| OTU35 | 1 | Methanobrevibacter sp. WBY1 (EU919429.1) | 93 |

| OTU36 | 24 | uncultured Methanomassiliicoccales archaeon (KT225454.1) | 85 |

| OTU37 | 1 | Methanobrevibacter sp. WBY1 (EU919429.1) | 96 |

| OTU38 | 1 | Methanogenic archaeon WGK1 (GQ339874.1) | 94 |

| OTU39 | 1 | Methanobrevibacter smithii (CP017803.1) | 84 |

| OTU40 | 1 | uncultured methanogenic archaeon (EF628097.1) | 90 |

| OTU41 | 1 | Methanobrevibacter sp. WBY1 (EU919429.1) | 88 |

| OTU42 | 1 | uncultured Methanomassiliicoccales archaeon (KT225454.1) | 75 |

| OTU43 | 2 | Methanobrevibacter sp. WBY1 (EU919429.1) | 94 |

aNH-No hit sequence on methanogens in the database

bOTUmcrA-mcrA sequences were obtained from the DOTUR program as a unique sequence, while OTUs were generated by the DOTUR program at 97% species-level identity

Fig. 1.

Taxonomic composition of methanogen (mcrA) communities from the clone libraries of finishing pigs

Phylogeny of abundant methanogens

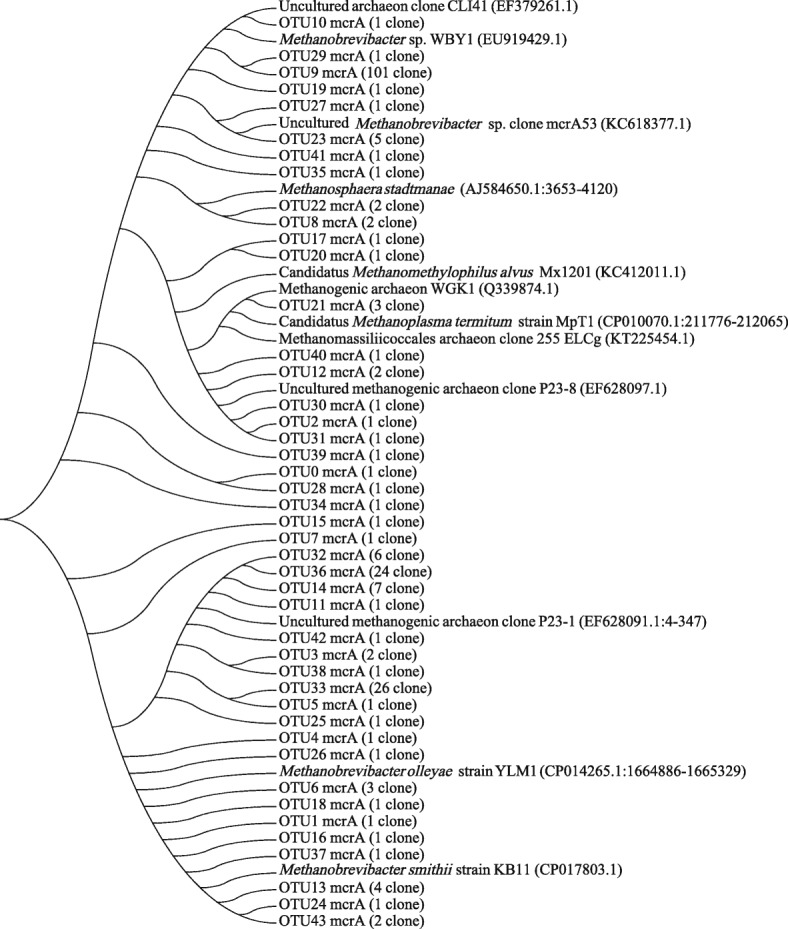

To investigate the phylogenetic placement of OTUsmcrA methanogen sequences from finishing pigs, the clone reference sequences were aligned to build a distance-matrix phylogenetic tree (Fig. 2). Most OTUsmcrA clustered with Methanobrevibacter of different species (Fig. 2). A total of 91 OTUsmcrA clustered closely with an unclassified sequence from the database and was not affiliated with any cultured species. Four OTUsmcrA clustered with Methanosphaera stadtmanae. Three OTUsmcrA were affiliated with Candidatus Methanoplasma termitum.

Fig. 2.

Phylogenetic analysis of methanogen partial mcrA sequences from finishing pig clone libraries inferred using MEGA (ver. 7). Evolutionary distances were calculated using the Neighbour-joining method. The tree was bootstrap resampled 1000 times.The 219 clones examined were assigned to 43 OTUs by DOTUR using a 97% species-level identity

The abundance of total methanogens and order Methanobacteriales and other parameters in the colonic samples

The copy number of total methanogens and Methanobacteriales was not different in different gut intestines (Table 2). The Eh was negative and within the range of − 297.00~423.00 mV in the large intestine, showing an increasing trend from the caecum to the rectum in the digesta of the large intestine of finishing pigs. The pH was within the range of 5.04~6.97 in the large intestine. Both pH and total VFAs had no significant difference among different intestines of finishing pigs. The acetate and propionate levels were lowest in the digesta of the rectum (P < 0.05, Table 3). The correlation between the number of methanogens and Eh is shown in Fig. 3.

Table 2.

The population Log 10 (copy number/μg DNA) of methanogens and Methanobacteriales in the different large intestines of finishing pigs

| Caecum | Ascending colon | Transverse colon | Descending colon | Rectum | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total Methanogens | 7.81 ± 0.51 | 8.32 ± 0.33 | 8.22 ± 0.31 | 8.22 ± 0.21 | 7.75 ± 0.61 |

| Methanobacteriales | 5.83 ± 0.24 | 5.67 ± 0.17 | 5.86 ± 0.24 | 5.94 ± 0.31 | 6.30 ± 0.27 |

Table 3.

The Eh (mV), pH and volatile fatty acid (VFA, mmol/L) values in the different large intestines of finishing pigs

| Items | Caecum | Ascending colon | Transverse colon | Descending colon | Rectum |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Eh | −379.47 ± 5.09a | −379.33 ± 3.63a | − 375.03 ± 4.19a | − 363.10 ± 6.52ab | − 355.50 ± 7.01b |

| pH | 6.15 ± 0.08 | 6.11 ± 0.07 | 6.09 ± 0.07 | 6.10 ± 0.05 | 6.13 ± 0.06 |

| Acetate | 33.13 ± 1.65ab | 33.50 ± 1.87a | 29.43 ± 1.96ab | 29.24 ± 1.69ab | 27.82 ± 1.74b |

| Propionate | 12.78 ± 0.99a | 11.75 ± 0.91b | 11.22 ± 1.00 b | 10.24 ± 1.01b | 10.04 ± 0.98b |

| Butyrate | 5.60 ± 0.74 | 7.26 ± 1.09 | 6.44 ± 0.90 | 5.19 ± 0.85 | 5.87 ± 0.73 |

| A/P (Acetate to Propionate) | 2.79 ± 0.12 | 3.19 ± 0.20 | 3.18 ± 0.38 | 3.49 ± 0.30 | 3.40 ± 0.34 |

| Total VFAs | 51.48 ± 3.03 | 52.41 ± 3.45 | 46.98 ± 3.41 | 44.57 ± 3.25 | 43.62 ± 3.01 |

Different letters in the same column indicate significant differences (P < 0.05)

Fig. 3.

The relationship between the number of total methanogens, Methanobacteriales and Eh

Discussion

The results of this study indicated that Methanobrevibacter was the dominant methanogen in the large intestine of finishing pigs. Methanobrevibacter mainly utilizes hydrogen and carbon dioxide to produce methane, which is similar to findings in ruminants [15]. Dietary fibre can increase Methanobrevibacter in the hindgut of pigs [13, 16, 17]. The hydrogen produced by bacteria is consumed by Methanobrevibacter and is beneficial for maintaining gut health by improving the degradation of fibre [18]. Similar results were found in our previous study of the hindgut in Lantang pigs [17]. All clone sequences belonged to Methanobrevibacter in the piglets fed with a basal diet [16]. Methanobrevibacter sp. WBY1 was the predominant methanogen (Table 1), followed by M. smithii and M. olleyae, in accordance with previous studies of pig faeces [12, 14, 16]. However, in our study, we did not find M. gottschalkii, which was isolated from pig faeces in a previous study [8]. Candidatus Methanoplasma termitum was observed in our study and recently divided into the seventh order of methanogens as Methanomassiliicoccales, previously designated Methanoplasmatales [19]. Unlike most methanogens that have a pathway for the reduction of CO2 to methyl coenzyme M, Methanomassiliicoccales produces methane by the reduction of methanol or methylamines, which contributes to lower methane emissions [19, 20]. A total of 29/219 OTUsmcrA belonged to Methanosphaera stadtmanae DSM 3091 in our study, which produce methane only by the reduction of methanol with H2 and acetate as a carbon source [21]. However, the sequence identity of Methanosphaera stadtmanae DSM 3091 and Candidatus Methanoplasma termitum was in the range of 84~88%, indicating that these methanogens in the hindgut of finishing pigs should be studied further.

Environmental parameters and VFAs are highly important for maintaining microbiome balance in the gut [22]. Eh is an important factor that influences the microbiome composition because oxidation-reduction reactions are needed by the microbiome [23]. Different microorganisms need specific Eh values to survive; in general, anaerobes require an Eh range from + 100 to − 250 mV [24]. Many studies have been conducted on ruminants [25, 26]. The Eh value varies mostly within the range from − 300 to + 200 mV in the digestive tract of ruminants, from − 130 to − 200 mV in the rumen medium and from − 145 to − 190 mV in the fluid of goats [27, 28]. The Eh values in the large intestine of finishing pigs in our study were from − 297 to − 423 mV and were lower than in rumen, indicating that the hindgut of finishing pigs has a stricter environment. The correlation analysis between Eh and Methanobacteriales shows that the higher Eh value within the range in our study improves the growth of Methanobacteriales in the rectum, the descending colon, and the caecum. Overall, the methanogens in pigs require stricter anaerobic conditions and are difficult to isolate and culture compared to those of ruminants. However, whether the high Eh values in the gut of finishing pigs improve the growth of methanogens requires further study. VFAs are generated via fermentation in the large intestine and maintain a pH between 6 and 7. In this study, the pH in the large intestine was between 5.04 and 6.97. The pH, total methanogens, and Methanobacteriales numbers were stable in the different large intestines. The reason for this result might be that the dominant effect of the identical diet for the finishing pigs in our study was the same.

Methanogens are more difficult to culture than bacteria. Metagenomics has been used to discover the dark matter of methanogen in the environment [29]. The 16S rRNA, mcrA or library clone sequences have similar compositions of methanogens [11, 16]. However, clone library is one of the classic methods to analyse the community of microorganisms. However, according to the results, the coverage of the library was only 80%, indicating an insufficient number of selected monoclones in our study. Recently, Koskinen et al. (2017) reported a new archaeal sequencing method to discover the specific archaeal communities associated with different sites in the human body [6]. This method could be used to investigate the methanogen diversity across different treatments with diet or age in pigs to improve the poor recovery of methanogen species in gut microbiome studies. Moreover, isolation and culture of a single methanogen to understand its generic-specific physio-ecological characteristics, and expanding the reference database for community analysis for sequencing are also necessary for CH4 emissions research [30]. However, cultivation of methanogens is difficult using traditional methods because of the strict conditions requirements. Culturomics, as a new technology, might contribute to addressing the difficulties of cultivation [31].

Conclusions

The major methanogen in the large intestine of finishing pigs is Methanobrevibacter. The seventh order Methanomassiliicoccales and genus Methanosphaera stadtmanae in the large intestine of pigs might contribute to transferring hydrogen to reduce methane emissions. The redox potential (Eh) was high in the large intestine of finishing pigs and was positively correlated with the population of Methanobacteriales. New sequencing methods and culturomics should be used to expand the understanding of methanogens in the gut of pigs.

Methods

Animals and collection of samples

Thirty finishing pigs (Duroc * Landrace * Yorkshire), weighing 95 ± 5 kg (140–150 days old, of which half were male and half female) with the same diet and feeding conditions for 30 days, were selected for this experiment. The pigs were owned by Shenzhen Nongmu Meiyi Meat Industry Co., Ltd. Permission for using these pigs was granted by the senior management in the company. All experimental procedures involving animals were approved by the Animal Experimental Committee of South China Agricultural University (SYXK2014–0136). The composition and nutrient content of the experimental diets provided by the farm can be seen in Table 4. The pigs were slaughtered by stunning with electrical currents followed within 30 s with bloodletting. Bloodletting was completed within 5 min. All procedures followed the “operating procedures of pig slaughtering” (GB/T 17236–2008). Subsequently, the caecum, the ascending colon, the transverse colon, the descending colon, and the rectum were removed immediately. Eh, and pH were immediately measured with a 6010 ORP Analyzer (JENCO, USA) with an ORP electrode (Bowen, China) and an AZ8651 pH metre (Heng Xin, China). Approximately 10 g of digesta from each intestine was collected and placed immediately into liquid nitrogen and stored at − 80 °C for methanogen clone library construction and analysis, and VFA determination [32].

Table 4.

Ingredients and composition of the diets of the finishing pigs

| Ingredient, g per kg feed | Calculated composition | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Dry corn grain | 690 | Gross energy (MJ/kg) | 13.39 |

| Bean meal | 200 | NDF (mg/g) c | 162.3 |

| Rapeseed meal | 40 | ADF (mg/g) d | 70.4 |

| DDGSa | 30 | Crude protein (mg/g) | 161 |

| Premixb | 40 | Lysine (mg/g) | 8.4 |

| Met + Cys (mg/g) | 5.1 | ||

| Calcium (mg/g) | 5.3 | ||

| Phosphorus (mg/g) | 4.5 | ||

| Available phosphorus (mg/g) | 1.9 | ||

aDistillers dried grains with solubles

bCommercial premix consisting of trace elements (i.e., Fe, Cu, Zn, Mn, I, and Se), vitamins (i.e., A, D, K, E, B1, B2, B6, B12, C, folic acid, and biotin), amino acids (i.e., lysine, and methionine), Ca, P and salts

cNeutral detergent fibre

dAcid detergent fibre

DNA extraction, clone library construction and DNA sequencing

DNA was extracted from 300 mg of wet colonic digesta using the bead-beating method followed by the Soil DNA kit (Omega, USA). The mcrA gene was amplified using primer pairs, and the amplification protocols were utilized according to previously report [33]. PCR products were purified using the EasyPure Quick Gel Extraction Kit (Trans, Beijing, China), ligated into pEASY-T3 (Trans, Beijing, Chain) and transformed into Trans1-T1 Phage resistant chemically competent cell. Plasmid DNA was recovered from recombinant cell colonies and the DNA library was screened by PCR analysis using previously described primer pairs [33]. A total of 219 positive insert-containing clones were randomly selected, and the nucleotide sequences of the clones’ inserts were determined by Beijing AuGCT DNA-SYN Biotechnology Co., Ltd.

Statistical analysis and phylogenetic analysis

The phylogenetic software package PHYLIP was used to calculate the evolutionary distances between pairs of nucleotide sequences [34]. The distance matrix was then used to assign nucleic acid segments in various OTUs using the furthest neighbour algorithm by DOTUR [35]. Nucleic acid sequences showing ≥97% identity were assigned to a similar OTU. The sampling effort in the library was evaluated by calculating the coverage (C) according to the eq. C = [1-(n/N)], where n is the number of sequences represented by a single clone and N is the total number of clones analysed in the library [36]. The Shannon index, Species Richness, and Simpson index were calculated by the SPADEprogram and were used to characterize species diversity in the library [37]. Sequences were compared with NCBI GenBank entries (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov) using the nucleotide–nucleotide BLAST. The phylogenetic tree was constructed by the neighbour-joining method of the MEGA 7 program using the bootstrap test based on 1000 replicates [38]. The sequences have been submitted to GenBank under the accession numbers JN105737-JN105780.

Real-time PCR analysis

The copy numbers of the 16S rDNA gene of the group-specific methanogens were quantified with SYBR Green real-time PCR analysis. All real-time PCR assays were performed using a LightCycler instrument (Mx3005P, USA). The characteristics of the primer sets for real-time PCR of methanogens and Methanobacteriales are listed in Table 5. Plasmid DNA of the target genes was extracted from positive recombinant plasmids and the DNA concentration was measured by Qubit 2.0 (ThermoFisher Scientific, USA). The serial gradient concentration of plasmid DNA was used to generate a standard curve for methanogens and Methanobacteriales. The copies of each target methanogen were run in triplicate, and the mean values were calculated using a standard curve.

Table 5.

The characteristics of the primer and probe sets used in this study

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Bing Yu from Shenzhen Farming Meiyi Meat Industry Co., Ltd. for his instrumental assistance with the experimental design and sample collection during the study.

Funding

This work was supported by the earmarked fund for National Natural Science Foundation of China (31802108, 31772646).

Availability of data and materials

The sequences have been submitted to GenBank under the accession numbers JN105737-JN105780.

Abbreviations

- ADF

Acid detergent fiber

- DDGS

Distillers dried grains with solubles

- GHG

Greenhouse gas

- GWP

Global warming potential (GWP)

- mcrA

methyl coenzyme mreductase

- NCBI

National Center for Biotechnology Information

- NDF

Neutral detergent fiber

- OTUs

Operational taxonomic units

- VFA

Volatile fatty acids

Authors’ contributions

JM, HP, YW, YW, and XL conceived and designed the study. HP collected and processed the samples. JM and HP analyzed the data. JM and HP drafted the manuscript. All authors revised and edited the manuscript, gave final approval for the version to be published, and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Ethics approval

All experimental procedures involving animals were approved by the Animal Experimental Committee of South China Agricultural University (SYXK2014–0136).

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Jiandui Mi, Email: mijiandui@gmail.com.

Haiyan Peng, Email: 23796922@qq.com.

Yinbao Wu, Email: wuyinbao@scau.edu.cn.

Yan Wang, Email: 39169401@qq.com.

Xindi Liao, Phone: 86-20-85280279, Email: xdliao@scau.edu.cn.

References

- 1.Herrero M, Henderson B, Havlík P, Thornton PK, Conant RT, Smith P, et al. Greenhouse gas mitigation potentials in the livestock sector. Nat Clim Chang. 2016;6:452–461. doi: 10.1038/nclimate2925. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Philippe FX, Nicks B. Review on greenhouse gas emissions from pig houses: production of carbon dioxide, methane and nitrous oxide by animals and manure. Agric Ecosyst Environ. 2015;199:10–25. doi: 10.1016/j.agee.2014.08.015. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zhang B, Chen GQ. Methane emissions in China 2007. Renew Sust Energ Rev. 2014;30:886–902. doi: 10.1016/j.rser.2013.11.033. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zhou JB, Jiang MM, Chen GQ. Estimation of methane and nitrous oxide emission from livestock and poultry in China during 1949–2003. Energ Policy. 2007;35(7):3759–3767. doi: 10.1016/j.enpol.2007.01.013. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jørgensen H. Methane emission by growing pigs and adult sows as influenced by fermentation. Livest Sci. 2007;109(1):216–219. doi: 10.1016/j.livsci.2007.01.142. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Koskinen K, Pausan MR, Perras AK, Beck M, Bang C, Mora M, et al. First insights into the diverse human archaeome: specific detection of archaea in the gastrointestinal tract, lung, and nose and on skin. MBio. 2017. 10.1128/mBio.00824-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 7.Pike LJ, Forster SC. A new piece in the microbiome puzzle. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2018;16(4):186. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro.2018.24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Seshadri R, Leahy SC, Attwood GT, Teh KH, Lambie SC, Cookson AL, et al. Cultivation and sequencing of rumen microbiome members from the Hungate1000 collection. Nat Biotechnol. 2018;36(4):359–367. doi: 10.1038/nbt.4110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Donaldson GP, Lee SM, Mazmanian SK. Gut biogeography of the bacterial microbiota. Nat Rev Micro. 2016;14(1):20–32. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro3552. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Friedrich MW. Methyl-coenzyme M reductase genes: unique functional markers for methanogenic and anaerobic methane-oxidizing archaea. Method Enzymol. 2005;397:428–442. doi: 10.1016/S0076-6879(05)97026-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wilkins D, Lu XY, Shen Z, Chen J, Lee PKH. Pyrosequencing of mcrA and archaeal 16S rRNA genes reveals diversity and substrate preferences of methanogen communities in anaerobic digesters. Appl Environ Microb. 2015;81(2):604–613. doi: 10.1128/AEM.02566-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Su Y, Smidt H, Zhu WY. Comparison of fecal methanogenic archaeal community between Erhualian and landrace pigs using denaturing gradient gel electrophoresis and real-time PCR analysis. J Integr Agr. 2014;13(6):1340–1348. doi: 10.1016/S2095-3119(13)60529-8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Luo YH, Li H, Luo JQ, Zhang KY. Yeast-derived β-1,3-glucan substrate significantly increased the diversity of methanogens during in vitro fermentation of porcine colonic digesta. J Integr Agr. 2013;12(12):2229–2234. doi: 10.1016/S2095-3119(13)60381-0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mao SY, Yang CF, Zhu WY. Phylogenetic analysis of methanogens in the pig feces. Curr Microbiol. 2011;62(5):1386–1389. doi: 10.1007/s00284-011-9873-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Janssen PH, Kirs M. Structure of the archaeal community of the rumen. Appl Environ Microb. 2008;74(12):3619–3625. doi: 10.1128/AEM.02812-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Luo YH, Chen H, Yu B, He J, Zheng P, Mao XB, et al. Dietary pea fiber increases diversity of colonic methanogens of pigs with a shift from Methanobrevibacter to Methanomassiliicoccus-like genus and change in numbers of three hydrogenotrophs. BMC Microbiol. 2017. 10.1186/s12866-016-0919-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 17.Cao Z, Liang JB, Liao XD, Wright AD, Wu YB, Yu B. Effect of dietary fiber on the methanogen community in the hindgut of Lantang gilts. Animal. 2016;10(10):1666–1676. doi: 10.1017/S1751731116000525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chaucheyras-Durand F, Masséglia S, Fonty G, Forano E. Influence of the composition of the cellulolytic flora on the development of hydrogenotrophic microorganisms, hydrogen utilization, and methane production in the rumens of gnotobiotically reared lambs. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2010;76(24):7931–7937. doi: 10.1128/AEM.01784-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lang K, Schuldes J, Klingl A, Poehlein A, Daniel R, Brune A. New mode of energy metabolism in the seventh order of methanogens as revealed by comparative genome analysis of “Candidatus Methanoplasma termitum”. Appl Environ Microb. 2015;81(4):1338–1352. doi: 10.1128/AEM.03389-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Huang XD, Tan HY, Long R, Liang JB, Wright AD. Comparison of methanogen diversity of yak (Bos grunniens) and cattle (Bos taurus) from the Qinghai-Tibetan plateau, China. BMC Microbiol. 2012;12:237. doi: 10.1186/1471-2180-12-237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fricke WF, Seedorf H, Henne A, Kruer M, Liesegang H, Hedderich R, et al. The genome sequence of Methanosphaera stadtmanae reveals why this human intestinal archaeon is restricted to methanol and H2 for methane formation and ATP synthesis. J Bacteriol. 2006;188(2):642–658. doi: 10.1128/JB.188.2.642-658.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Koh A, De Vadder F, Kovatcheva-Datchary P, Bäckhed F. From dietary fiber to host physiology: short-chain fatty acids as key bacterial metabolites. Cell. 2016;165(6):1332–1345. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2016.05.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kueneman JG, Parfrey LW, Woodhams DC, Archer HM, Knight R, McKenzie VJ. The amphibian skin-associated microbiome across species, space and life history stages. Mol Ecol. 2014;23(6):1238–1250. doi: 10.1111/mec.12510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ray B. Factors influencing microbial growth in food. In: Ray B, Bhunia A, editors. Fundamental food microbiology. Buch. 2004. pp. 67–80. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Huang Y, Marden J, Julien C, Bayourthe C. Redox potential: an intrinsic parameter of the rumen environment. J Anim Physiol Anim Nutr. 2018;102(2):393–402. doi: 10.1111/jpn.12855. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Huang Y, Marden JP, Benchaar C, Julien C, Auclair E, Bayourthe C. Quantitative analysis of the relationship between ruminal redox potential and pH in dairy cattle: influence of dietary characteristics. Agr Sci. 2017;8(07):616. doi: 10.4236/as.2017.87047. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kalachniuk HI, Marounek M, Kalachniuk LH, Savka OH. Rumen bacterial metabolism as affected by extracellular redox potential. Ukr Biokhim Zh. 1994;66(1):30–40. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Marounek M, Bartos S, Kalachnyuk GI. Dynamics of the redox potential and rh of the rumen fluid of goats. Physiol Bohemoslov. 1982;31(4):369–374. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Evans PN, Parks DH, Chadwick GL, Robbins SJ, Orphan VJ, Golding SD, et al. Methane metabolism in the archaeal phylum Bathyarchaeota revealed by genome-centric metagenomics. Science. 2015;350(6259):434–438. doi: 10.1126/science.aac7745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mayumi D, Mochimaru H, Tamaki H, Yamamoto K, Yoshioka H, Suzuki Y, et al. Methane production from coal by a single methanogen. Science. 2016;354(6309):222–225. doi: 10.1126/science.aaf8821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lagier JC, Khelaifia S, Alou MT, Ndongo S, Dione N, Hugon P, et al. Culture of previously uncultured members of the human gut microbiota by culturomics. Nat Microbiol. 2016;1:16203. doi: 10.1038/nmicrobiol.2016.203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 32.Zhang YT, Lu DD, Chen JY, Yu B, Liang JB, Mi JD, et al. Effects of fermented soybean meal on carbon and nitrogen metabolisms in large intestine of piglets. Animal. 2018;12(10):2056–2064. doi: 10.1017/S1751731118000058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Luton PE, Wayne JM, Sharp RJ, Riley PW. The mcrA gene as an alternative to 16S rRNA in the phylogenetic analysis of methanogen populations in landfill. Microbiology. 2002;148(11):3521–3530. doi: 10.1099/00221287-148-11-3521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Shimada MK, Nishida T. A modification of the PHYLIP program: a solution for the redundant cluster problem, and an implementation of an automatic bootstrapping on trees inferred from original data. Mol Phylogenet Evol. 2017;109:409–414. doi: 10.1016/j.ympev.2017.02.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Schloss PD, Handelsman J. Introducing DOTUR, a computer program for defining operational taxonomic units and estimating species richness. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2005;71(3):1501–1506. doi: 10.1128/AEM.71.3.1501-1506.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Good IJ. The population frequencies of species and the estimation of population parameters. Biometrika. 1953;40(3–4):237–264. doi: 10.1093/biomet/40.3-4.237. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Chao A, Shen T. User’s guide for program SPADE (Species prediction and diversity estimation) Taiwan: National Tsing Hua University; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Tamura K, Dudley J, Nei M, Kumar S. MEGA4: molecular evolutionary genetics analysis (MEGA) software version 4.0. Mol Biol Evol. 2007;24(8):1596–1599. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msm092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Yu Y, Lee C, Kim J, Hwang S. Group-specific primer and probe sets to detect methanogenic communities using quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction. Biotechnol Bioeng. 2005;89(6):670–679. doi: 10.1002/bit.20347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The sequences have been submitted to GenBank under the accession numbers JN105737-JN105780.