Abstract

Background

Pulmonary embolism (PE) is a fatal condition, with a subsequent variety of complications. Although rare, the ensuing presentation of atrial fibrillation (AF) secondary to PE is evident in the literature. However, there has been no report of AF with slow ventricular response requiring a pacemaker as a complication of PE.

Case presentation

A 78-year-old obese female presented to the emergency room with new onset dyspnea. Computed tomography pulmonary angiogram revealed bilateral PE. Twenty-four hours later, the patient developed new onset AF with slow ventricular response. Therefore, a single chamber pacemaker was implanted.

Conclusion

PE causing AF with slow ventricular response has not been reported or explained in the literature. The mechanism of this complication is yet to be understood and will require further investigation to explain this newly presented relationship.

Keywords: Atrial fibrillation, Arrhythmia, Case report, Pacemaker, Pulmonary embolism, Slow

Background

Pulmonary embolism (PE) is a fatal condition, which can cause a variety of complications. One of these rare complications are arrythmias such as atrial fibrillation (AF) [1]. Although rare, the ensuing presentation of AF secondary to PE is evident in the literature, however there has been no report of PE causing AF with slow ventricular response requiring a pacemaker [1–3]. We present a case of AF with slow ventricular response caused by a bilateral PE, with a conceivable pathophysiological hypothesis.

Case presentation

A 78-year-old obese female presented to the emergency room with new onset dyspnea of one day duration, which worsened in the past couple of hours. Her medical history included hypertension and a hemorrhagic stroke two years prior which left her bedbound. She denied any familial history of PE, leg pain, or palpitation. At admission, blood pressure, pulse rate and peripheral oxygen saturation were 116/78 mmHg, 135 beats/min and 88%, respectively. On physical examination, she had tachypnea (30 breaths/minute) and electrocardiography revealed sinus tachycardia. Arterial blood gas analysis on room air yielded pH 7.44, PCO2 33.9 mmHg, and PO2 72.9 mmHg. Routine blood tests demonstrated a normal cardiac troponin I levels and no evidence of electrolyte imbalances, while chest X-ray revealed no signs of heart failure. Nevertheless, D-dimer was highly elevated (> 4000 ng/dL) increasing the suspicion of PE. Computed tomography pulmonary angiogram was sought revealing bilateral PE (Fig. 1a). Lower limb Doppler was negative for deep vein thrombosis.

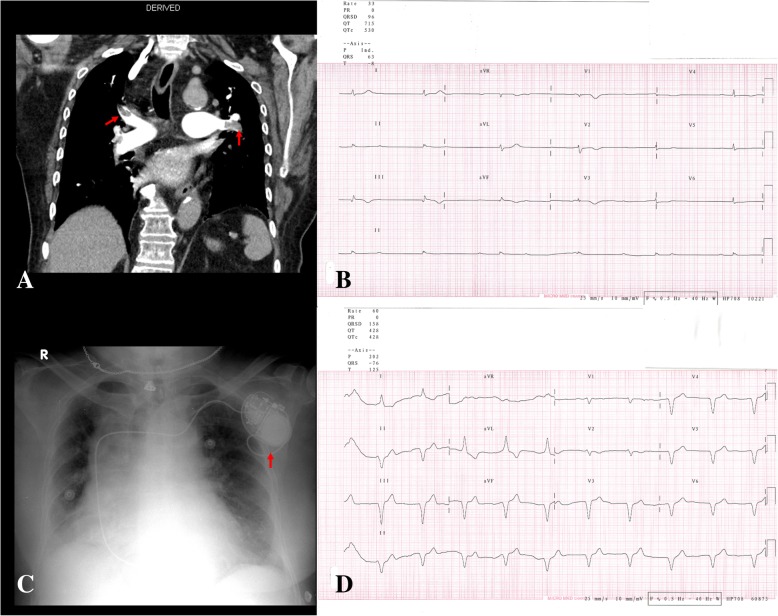

Fig. 1.

a Computed tomography pulmonary angiography revealing filling defects (red arrow) in the distal left and right main pulmonary arteries b Twelve lead electrocardiograph showing atrial fibrillation with ventricular response of 33 beats per minute. c Chest x-ray after implantation of a single chamber pacemaker (red arrow) in the left pectoral pocket. d Twelve lead electrocardiograph post pacemaker implantation

Twenty-four hours after diagnosing bilateral PE and stabilizing the patient with anticoagulation and hemodynamic support, the patient developed new onset palpitation, dizziness, and fatigue. Cardiac enzymes were repeated showing a mild elevation. Electrocardiography reveled new onset AF with slow ventricular response of 33 beats/min (Fig. 1b). She was not on any negative chronotropic drugs and no electrolyte imbalance was detected. Echocardiography revealed normal left ventricular systolic function and dimensions, left ventricular regional wall motion, and both left and right atrium dimensions. However, it highlighted dilated right ventricular dimensions with a basal diameter of 50 mm and evidence of McConnell’s sign (right ventricular free wall hypokinesia) with paradoxical septal wall motion. In addition, it revealed impaired right ventricular systolic function with tricuspid annular plane systolic excursion of around 1.5 cm, flattening of intraventricular septum, and moderate tricuspid regurgitation with pulmonary artery systolic pressure around 50 mmHg. As the patient was developing hemodynamic instability, 48 h later, single chamber pacemaker was implanted in the left pre-pectoral pocket and the basal heart rate was set up to 60 beats per minute (Fig. 1c and d). After a 2-month follow-up, the patient showed normal vital signs and her electrocardiogram showed a paced rhythm with a heart rate of 60 beats per minute. She developed no further complications or clinical morbidities in spite her poor prognosis.

Discussion and conclusion

The association of causation between PE and AF with slow ventricular response remains to be vague in the literature in which the exact pathophysiology and causal mechanism is yet to be fully understood [2, 3]. On a pathophysiological level that might demonstrate AF, Flegel concluded that a PE may trigger AF by causing acute right ventricular dilatation with strain, something that was evident in our case [4]. Another case by Marti et al. hypothesized about a similar pathology stating that a PE could trigger an adrenergic surge stimulating the Bezold-Jarish reflex, a vagal response and decreased sympathetic tone, leading to abnormal heart electrical conduction which in part may cause slow conduction [5]. Another plausible hypothesis for the slow conduction is that the massive PE may have caused transient myocardial ischemia and dysfunction to the atrioventricular node. The consequence of this massive PE was demonstrated in the echocardiography as regional pattern of right ventricular dysfunction, with akinesia of the mid free wall and hyper contractility of the apical wall, which is also known as McConnell’s sign [6]. We believe the conclusion of Flegel along with one of the latter two hypothesis may be an explanation of the AF with slow ventricular response caused by PE [4, 5].

To our knowledge, PE causing AF with slow ventricular response has not been reported or explained in the literature. Hence, the mechanism of this complication is yet to be understood and will require further investigation to explain this newly presented relationship.

Acknowledgments

Not applicable.

Funding

The authors did not receive any funding for this manuscript.

Availability of data and materials

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article and in its additional files.

Abbreviations

- AF

Atrial fibrillation

- PE

Pulmonary embolism

Authors contributions

MAA and MNE managed the patient and revised the manuscript. AJA wrote the manuscript and revised the manuscript and figures. All the authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

All the procedures performed in this study were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee, and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments; or with comparable ethical standards.

Consent for publication

Written informed consent was obtained from the patient for publication of this case report and any accompanying images and videos. A copy of the written consent is available for review by the editor of this journal.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Mohammad A. Abdulsalam, Phone: +96597923190, Email: msalam87@hotmail.com

Mohammed N. Elganainy, Email: mohammednabil_eg@hotmail.com

Ahmad J. Abdulsalam, Email: dr.ahmad.j.abdulsalam@gmail.com

References

- 1.Ng ACC, Adikari D, Yuan D, Lau JK, Yong ASC, Chow V, et al. The prevalence and incidence of atrial fibrillation in patients with acute pulmonary embolism. PLoS One. 2016;11:e0150448. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0150448. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gex G, Gerstel E, Righini M, Le Gal G, Aujesky D, Roy P, et al. Is atrial fibrillation associated with pulmonary embolism? J Thromb Hemost. 2012;10:347–351. doi: 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2011.04608.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Krajewska A, Ptaszynska-Kopczynska K, Kiluk I, Kosacka U, Milewski R, Krajewski J, et al. Paroxysmal atrial fibrillation in the course of acute pulmonary embolism: clinical significance and impact on prognosis. Biomed Res Int. 2017;2017:5049802. doi: 10.1155/2017/5049802. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Flegel KM. When atrial fibrillation occurs with pulmonary embolism, is it the chicken or the egg? CMAJ. 1999;160:1181–1182. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Martí J, Casanovas N, Recasens L, Comín J, García A, Bruguera J. Complete atrioventricular block secondary to pulmonary embolism. Rev Esp Cardiol. 2005;58:230–232. doi: 10.1157/13071899. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.López-Candales A, Edelman K, Candales MD. Right ventricular apical contractility in acute pulmonary embolism: the McConnell sign revisited. Echocardiography. 2010;27:614–620. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-8175.2009.01103.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article and in its additional files.