Abstract

Background

Solid-state fermentation (SSF) mimics the natural decay environment of soil fungi and can be employed to investigate the production of plant biomass-degrading enzymes. However, knowledge on the transcriptional regulation of fungal genes during SSF remains limited. Herein, transcriptional profiling was performed on the filamentous fungus Penicillium oxalicum strain HP7-1 cultivated in medium containing wheat bran plus rice straw (WR) under SSF (WR_SSF) and submerged fermentation (WR_SmF; control) conditions. Novel key transcription factors (TFs) regulating fungal cellulase and xylanase gene expression during SSF were identified via comparative transcriptomic and genetic analyses.

Results

Expression of major cellulase genes was higher under WR_SSF condition than that under WR_SmF, but the expression of genes involved in the citric acid cycle was repressed under WR_SSF condition. Fifty-six candidate regulatory genes for cellulase production were screened out from transcriptomic profiling of P. oxalicum HP7-1 for knockout experiments in the parental strain ∆PoxKu70, resulting in 43 deletion mutants including 18 constructed in the previous studies. Enzyme activity assays revealed 14 novel regulatory genes involved in cellulase production in P. oxalicum during SSF. Remarkably, deletion of the essential regulatory gene PoxMBF1, encoding Multiprotein Bridging Factor 1, resulted in doubled cellulase and xylanase production at 2 days after induction during both SSF and SmF. PoxMBF1 dynamically and differentially regulated transcription of a subset of cellulase and xylanase genes during SSF and SmF, and conferred stress resistance. Importantly, PoxMBF1 bound specifically to the putative promoters of major cellulase and xylanase genes in vitro.

Conclusions

We revealed differential transcriptional regulation of P. oxalicum during SSF and SmF, and identified PoxMBF1, a novel TF that directly regulates cellulase and xylanase gene expression during SSF and SmF. These findings expand our understanding of regulatory mechanisms of cellulase and xylanase gene expression during fungal fermentation.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (10.1186/s13068-019-1445-4) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Transcriptional regulation, Cellulase, Xylanase, Solid-state fermentation, Submerged fermentation, Penicillium oxalicum

Background

As decomposers, soil fungi play essential roles in global carbon cycling due to their ability to produce enzymes that degrade plant biomass into monosaccharides such as glucose and xylose. Solid-state fermentation (SSF) mimics the natural decay environment of soil fungi, and can be used to investigate production of plant biomass-degrading enzymes, the global carbon cycle, and commercial production of high value-added bioproducts including ancient Chinese liquor, soy sauce, vinegar, penicillin and other antibiotics, pigments, and environmentally friendly sources of alternative energy [1, 2]. Compared with submerged fermentation (SmF), SSF has various advantages including direct use of agricultural and industrial residues as carbon sources, resulting in lower cost.

The filamentous fungus Penicillium oxalicum secretes integrated cellulolytic and xylolytic enzymes, and can be used as an alternative to the industrial fungal strain Trichoderma reesei owing to its high β-glucosidase (EC 3.2.1.21) activity [3]. Production of fungal cellulases and xylanases not only depends on stimulation of exogenous carbon sources under certain cultivation conditions; it is also strictly controlled by regulatory networks comprising numerous transcriptional factors (TFs), signal sensors, and receptors. For example, culturing of P. oxalicum strain EU2106 in medium containing wheat bran (WB) under SSF reportedly achieved higher cellulase production than in medium containing corncob, rice husk, rice straw, or sugarcane bagasse [4]. Furthermore, induction of P. oxalicum strain HP7-1 using WB plus Avicel under SmF proved more favourable for cellulase and xylanase production than induction using WB alone [3].

Experiments showed higher expression of the glucoamylase gene glaB in Aspergillus oryzae cultivated on wheat-based solid medium than wheat-based liquid medium [5]. Moreover, transcriptional levels of laccase genes from Pleurotus ostreatus are upregulated under SmF conditions containing wheat straw, but downregulated under SSF [6]. However, systematic analysis of genome-wide gene expression in filamentous fungi under different cultivation conditions, including SSF and SmF, is scare.

Most recent studies on TFs regulating the expression of genes encoding cellulolytic and xylolytic enzymes have mainly focused on filamentous fungi, including Trichoderma, Aspergillus, Penicillium, and Neurospora crassa, under SmF condition, such as transcriptional activators CLR-2/ClrB [3, 7, 8], PoxCxrA [9], and the carbon catabolite repressor CreA/CRE1/CRE-1 [10, 11]. Nevertheless, knowledge of the regulatory roles of TFs in cellulase and xylanase gene expression in filamentous fungi during SSF remains limited.

In the present study, the transcriptomes of P. oxalicum during SSF and SmF in medium containing wheat bran plus rice straw (WR) were comparatively analysed. Candidate genes potentially regulating cellulase and xylanase production in P. oxalicum during SSF were screened out and knocked out in the parental strain ∆PoxKu70. The essential gene PoxMBF1, encoding Multiprotein Bridging Factor 1, was found to control cellulase and xylanase gene expression in P. oxalicum during SSF and SmF via genetic and biochemical analyses.

Results

Comparative transcriptomic analysis of P. oxalicum strain HP7-1 during SSF and SmF

The P. oxalicum wild-type strain HP7-1 was, respectively, cultivated in solid and liquid media containing WR as the carbon source for 24 h, and total RNA was extracted and subjected to RNA sequencing (RNA-Seq) on an Illumina HiSeq 2000 system. Approximately 24 million clean reads were generated for each sample, and the length of each read was 100 bp. More than 90% of clean reads were mapped onto the genome of P. oxalicum strain HP7-1 (Additional file 1: Table S1).

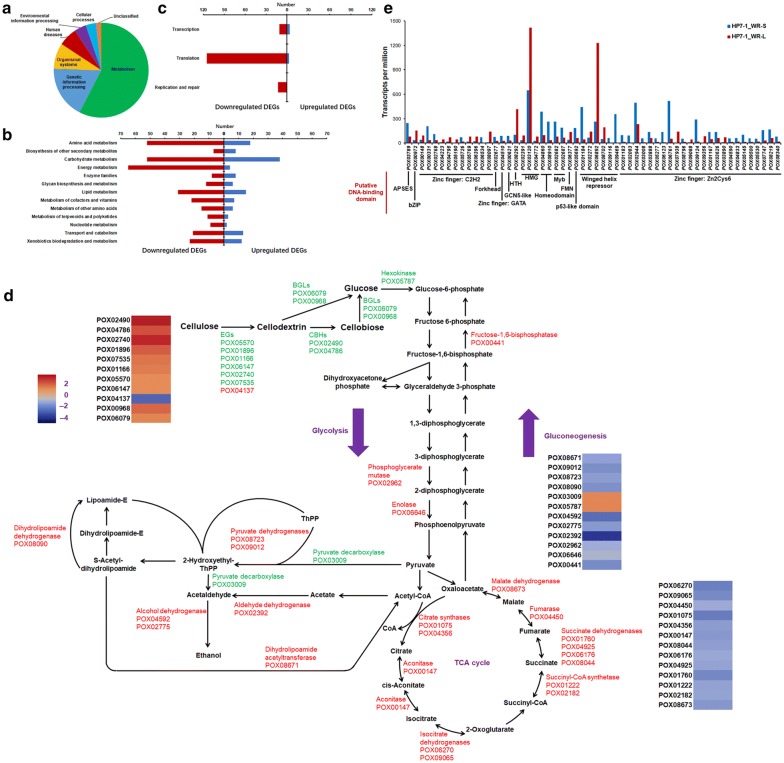

Using |log2-fold change| ≥ 1 and probability ≥ 0.8 as thresholds, 1724 differentially expressed genes (DEGs) were identified by comparing P. oxalicum strain HP7-1 grown in solid medium containing WR (HP7-1_WR-S) and liquid medium containing WR (HP7-1_WR-L), comprising 772 upregulated (1.0 ≤ log2-fold change ≤ 12.9) and 952 downregulated (− 2.3 ≤ log2-fold change ≤ − 1.0) genes (Additional file 2: Table S2). Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) annotation analysis revealed that three quarters of the detected DEGs were involved in metabolism and genetic information processing (Fig. 1a). Among them, downregulated DEGs were more prevalent in almost all branches of metabolism and genetic information processing than upregulated DEGs, especially DEGs involved in translocation (Fig. 1b, c).

Fig. 1.

Comparative analysis of transcriptomes from P. oxalicum strain HP7-1 cultivated in media containing WR under SSF and SmF. a KEGG annotation of proteins encoded by DEGs in HP7-1_WR-S compared with HP7-1_WR-L. The screening criteria for DEGs were |log2-fold change| ≥ 0.8 and probability ≥ 1.0. b Number of upregulated and downregulated DEGs involved in metabolism in HP7-1_WR-S. c Number of upregulated and downregulated DEGs involved in genetic information processing in HP7-1_WR-S. d Transcriptional levels of DEGs involved in glycolysis/gluconeogenesis and the TCA cycle in HP7-1_WR-S. e Transcriptional levels of DEGs encoding putative TFs in HP7-1_WR-S. HP7-1_WR-S, P. oxalicum strain HP7-1 cultivated on solid medium containing WR under SSF; HP7-1_WR-L, P. oxalicum strain HP7-1 cultivated in liquid medium containing WR under SmF. WR, wheat bran plus rice straw; SSF, solid-state fermentation; SmF, submerged fermentation

Among DEGs involved in glycolysis and gluconeogenesis, 12 were detected in the transcriptome of HP7-1_WR-S, including 10 downregulated with a log2-fold change of 1.0–5.0 and two upregulated with a log2-fold change of 1.2, compared with those in HP7-1_WR-L. These DEGs included hexokinase gene POX05787, fructose-1,6-bisphosphatase gene POX00441, phosphoglycerate mutase gene POX02962, enolase gene POX06646, pyruvate dehydrogenase genes POX08723 and POX09012, pyruvate decarboxylase gene POX03009, aldehyde dehydrogenase gene POX02392, dihydrolipoamide dehydrogenase gene POX08090, alcohol dehydrogenase genes POX04592 and POX02775, and dihydrolipoamide acetyltransferase gene POX08671. Moreover, 13 genes associated with the citric acid or tricarboxylic acid (TCA) cycle were identified, including citrate synthase genes POX01075 and POX04356, aconitase gene POX00147, isocitrate dehydrogenase genes POX06270 and POX09065, succinyl-CoA synthetase genes POX01222 and POX02182, four succinate dehydrogenase genes (POX01760, POX04925, POX06176, and POX08044), fumarase gene POX04450, and malate dehydrogenase gene POX08673, all exhibiting a 2.3–4.5-fold decrease in transcript levels in HP7-1_WR-S compared with HP7-1_WR-L (Fig. 1d).

In general, glucose used for glycolysis in fungal cells is derived from exogenous carbon sources such as cellulose or starch. Exogenous carbon sources are degraded into glucose by carbohydrate-active enzymes (CAZymes), especially cellulases and amylases. Among the 1724 DEGs identified in HP7-1_WR-S, 158 encode putative CAZymes, including 106 upregulated and 52 downregulated genes with 1.1 ≤ log2-fold change ≤ 8.8 and − 7.2 ≤ log2-fold change ≤ − 1.1, respectively. Remarkably, 11 key cellulase genes, including two cbh genes POX04786/Cel7A-1 and POX02490/Cel6B, seven, eg genes (POX01166/Cel5B, POX01896/Cel5C, POX02740, POX04137, POX05570/Cel45A, POX06147/Cel5A, and POX07535/Cel12A), and two β-glucosidase genes POX00968 and POX06079, were identified among the 158 putative CAZyme genes. Except for POX04137, transcriptional levels of these cellulase genes were 2.1–11.4-fold higher in HP7-1_WR-S than in HP7-1_WR-L (Fig. 1d).

Comparative analysis of the transcriptomes of HP7-1_WR-S and HP7-1_WR-L also revealed significant differences in the transcription of 56 genes encoding putative TFs. Based on the DNA-binding domain predicted using Bioinformatics, these TFs could be classified into 12 types: zinc finger domain (Zn2Cys6, C2H2, GATA; 64%), winged helix repressor (11%), APSES domain (ASM-1, Phd1, StuA, EFG1, and Sok2), bZIP, Forkhead, GCN5-like, high mobility group, helix–turn–helix (HTH), homeodomain, p53-like domain, FMN-binding split barrel, and Myb. In HP7-1_WR-S, transcripts of 36 of the 56 TF-encoding DEGs were upregulated between 1.1- and 315.1-fold compared with HP7-1_WR-L (Fig. 1e). It should be noted that 16 DEGs (POX00331/FlbC, POX00972/ClrC, POX01184, POX01167/CxrA, POX02768/PacC, POX03789/StuA, POX03888/PrtT, POX03890/AmyR, POX04772/HmbB, POX04795/PDE_07134, POX04860, POX05692/Vib1, POX05726, POX08097/PDE_01706, POX08910, and POX09356) are reportedly involved in cellulase production in filamentous fungi [9, 11–15].

Novel regulatory genes potentially controlling cellulase production in P. oxalicum during SSF

To identify the key TFs regulating cellulase gene expression in P. oxalicum during SSF, attempts were made to knock out 56 candidate TF-encoding genes in the ∆PoxKu70 parental strain using homologous recombination (Additional file 3: Figure S1a). The resulting deletion mutants were confirmed by PCR using specific primer pairs (Additional file 4: Table S3), and 43 were successfully generated (Additional file 3: Figure S1b; Additional file 5: Table S4), including 18 mutants constructed in the previous studies [9, 16]. Enzyme activity assays revealed significant alterations in filter paper cellulase (FPase) production in 14 mutants (∆POX00972, ∆POX01183, ∆POX02083, ∆POX03888, ∆POX04772, ∆POX04860, ∆POX05692, ∆POX05726, ∆POX06377, ∆POX08292, ∆POX08910, ∆POX09124, ∆POX09469, and ∆POX09500) during SSF using WR as the carbon source for 5 days compared with ∆PoxKu70 (p ≤ 0.05, Student’s t test; Fig. 2a). To the best of our knowledge, the present study is the first to confirm the involvement of these genes in cellulase production in P. oxalicum during SSF (Table 1). Intriguingly, to date, five of the 14 genes (POX02083, POX08292, POX09124, POX09469, and POX09500) have not been reported previously to be associated with cellulase production in P. oxalicum during SSF or SmF. In the present study, ∆POX08292 exhibited the highest FPase production (44.3% increase) among the five deletion mutants (∆POX02083, ∆POX08292, ∆POX09124, ∆POX09469, and ∆POX09500) compared with ∆PoxKu70 (Fig. 2a). Hence, POX08292 was selected for further investigation of its regulatory roles. To exclude the possibility of multiple copies of the POX08292 deletion cassette being integrated into the genome of ∆PoxKu70, Southern hybridisation was performed using a specific probe (Additional file 4: Table S3). The appearance of the expected bands on the gel (Additional file 3: Figure S1c) suggests that only one copy of the POX08292 knockout cassette was inserted into the genome of ∆PoxKu70.

Fig. 2.

Screening and identification of novel regulatory genes involved in cellulase production in P. oxalicum during SSF. a FPase activities of deletion mutants of P. oxalicum strain ∆PoxKu70 obtained through deletion of candidate regulatory genes during SSF using WR as the carbon source for 5 days after inoculation. *p ≤ 0.05 and **p ≤ 0.01 indicate significant differences between deletion mutants and parental strain ∆PoxKu70 (Student’s t tests). b Analysis of conserved domains in the POX08292 protein. c Phylogenetic tree of POX08292 and its putative homologs. The tree was constructed based on the neighbour-joining method and Poisson model. Bootstrap values, derived from 1000 replicates, are shown at nodes. WR wheat bran plus rice straw, SSF solid-state fermentation

Table 1.

Novel regulatory genes potentially regulating cellulase production in P. oxalicum during SSF

| Gene ID | GenBank accession number | InterPro annotationa | Domain description | Known homologous TFs under SmFb | Identity (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| POX00972 | MK389644 | IPR004827 | Basic leucine zipper (bZIP) | ClrC | 100 |

| POX01183 | MK389645 | IPR001138 | Zinc finger: Zn2Cys6 type | NA | NA |

| POX02083 | MK389646 | IPR001138 | Zinc finger: Zn2Cys6 type | NA | NA |

| POX03888 | MK389647 | IPR001138 | Zinc finger: Zn2Cys6 type | PrtT | 100 |

| POX04772 | KY860736 | IPR009071 | High mobility group box | HmbB | 41 |

| POX04860 | KY922971 | IPR009057 | Homeodomain-like | PDE_07199 | 99 |

| POX05692 | MK389648 | IPR008967 | p53-like | Vib1 | NA |

| POX05726 | KY860737 | IPR007087 | Zinc finger: C2H2 type | NA | NA |

| POX06377 | MK389649 | IPR007396 | PAI2-type | PAIB | 27 |

| POX08292 | MK389650 | IPR001387 | Helix–turn–helix type 3 | Mbf1p | 51 |

| POX08910 | KY860739 | IPR009057 IPR007526 |

Homeodomain-like; SWIRM domain | NA | NA |

| POX09124 | MK389651 | IPR001138 | Zinc finger: Zn2Cys6 type | NA | NA |

| POX09469 | MK389652 | IPR011991 | Winged helix repressor DNA-binding domain | NA | NA |

| POX09500 | MK389653 | IPR001138 IPR007219 |

Zinc finger, Zn2Cys6 type; Fungal_Trans | NA | NA |

aIPR, InterPro database (http://www.ebi.ac.uk/interpro/scan.html)

bTF, transcription factor: ClrC and PrtT from P. oxalicum 114-2 (EPS34061.1 and EPS29021.1); Vib1 from Neurospora crassa OR74A (XP_011394570.1); PAIB from Saccharomyces cerevisiae 131 (ONH80768.1); HmbB from A. nidulans FGSC A4 (XP_658871); Mbf1p from S. cerevisiae S288C (NP_014942.4)

Sequence analysis of POX08292

Simple Modular Architecture Research Tool (SMART) analysis revealed that the POX08292 protein, comprising 154 amino acids, contains an MBF1 domain (PF08523, E value = 5.9e−29) and an HTH XRE-family domain (SM000530, E value = 1.7e−08; http://smart.embl-heidelberg.de/; Fig. 2b). Protein alignment using NCBI BLASTP indicated that POX08292 shares 100%, 82%, and 51% identity with PDE_01903 in P. oxalicum 114-2 (GenBank accession number EPS26963.1), AN2996.2 in A. nidulans FGSC A4 (XP_660600.1), and Mbf1p in S. cerevisiae S288C (NP_014942.4), respectively. Furthermore, POX08292 was found to be evolutionarily close to orthologs in Aspergillus and Talaromyces (Fig. 2c). To facilitate subsequent study, POX08292 was re-designed as PoxMBF1 (where Pox represents P. oxalicum).

Regulation of cellulase and xylanase production in P. oxalicum by PoxMBF1 during SSF and SmF following induction

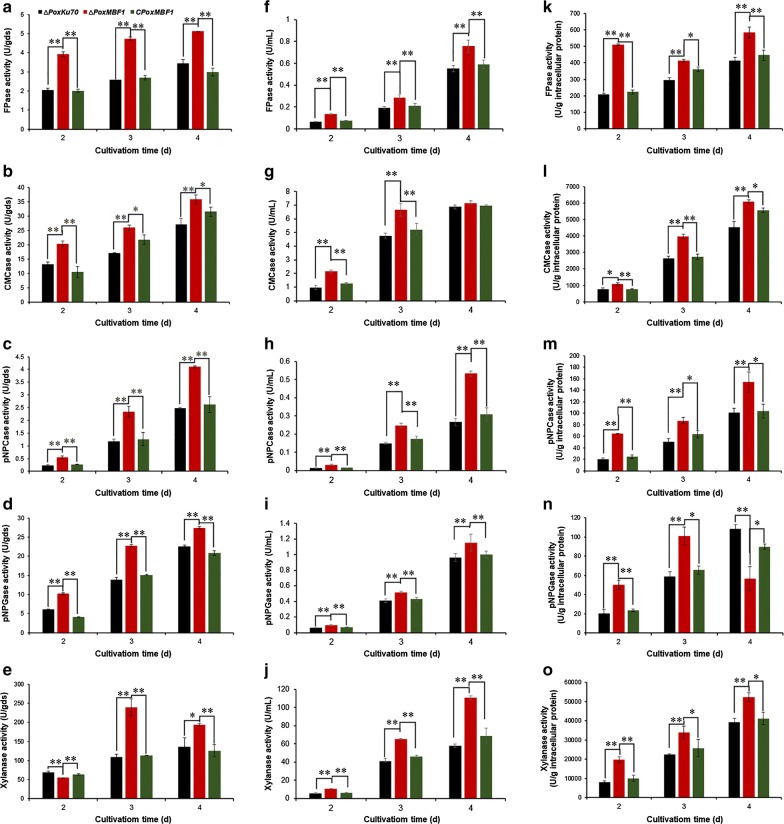

To further investigate the regulatory roles of PoxMBF1 in detail, P. oxalicum strain ∆PoxMBF1 (∆POX08292) and the parental strain ∆PoxKu70 were cultivated under different fermentation conditions (SSF and SmF) for 2–4 days after transfer from glucose. Enzyme activity tests revealed a 21.6–131.4% increase in cellulase activity corresponding to FPase, carboxymethylcellulase (CMCase), p-nitrophenyl-β-cellobiosidase (pNPCase), and p-nitrophenyl-β-glucopyranosidase (pNPGase), as well as xylanase production, by ∆PoxMBF1 during SSF using WR as the carbon source (except for xylanase production at 2 days) compared with ∆PoxKu70 (Fig. 3a–e).

Fig. 3.

Cellulase and xylanase production in P. oxalicum deletion mutant ∆PoxMBF1, parental strain ∆PoxKu70, and complementary strain CPoxMBF1 cultivated in solid medium containing WR (a–e) and liquid medium containing WR (f–j) or Avicel (k–o) after a shift from glucose. Enzymatic activity was determined at 2–4 days after transfer from glucose. *p ≤ 0.05 and **p ≤ 0.01 indicate significant differences between deletion mutants and parental strain ∆PoxKu70 or complementary strain CPoxMBF1 (Student’s t tests)

Cultivation of P. oxalicum strains ∆PoxMBF1 and ∆PoxKu70 in liquid medium containing WR under SmF for 2–4 days after a shift from glucose resulted in a 20.0–122.6% increase in cellulase and xylanase production by ∆PoxMBF1 compared with ∆PoxKu70, except for CMCase production at 4 days (Fig. 3f–j). Similar results were observed when cultured in liquid medium containing Avicel, and PoxMBF1 deletion resulted in a ~ 34.0–217.3% increase in cellulase production by P. oxalicum, except for pNPGase production at 4 days (Fig. 3k–o).

Furthermore, to confirm that the increase in cellulase and xylanase production by ∆PoxMBF1 was the result of PoxMBF1 deletion, complementary strain CPoxMBF1 was constructed and confirmed by PCR with specific primers (Additional file 4: Table S3; Additional file 6: Figure S2). The FPase, CMCase, pNPCase, pNPGase, and xylanase cellulase yields from complementary strain CPoxMBF1 were not significantly different from those of ∆PoxKu70 during SSF or SmF (Fig. 3).

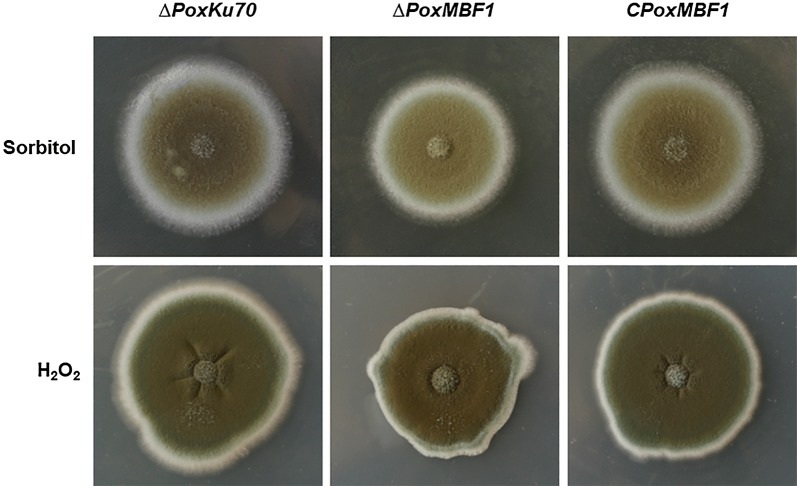

Effects of PoxMBF1 on growth and extracellular stress adaptation in P. oxalicum

To investigate the effects of PoxMBF1 on the growth of P. oxalicum, the ∆PoxMBF1 deletion mutant and ∆PoxKu70 parental strain were inoculated into liquid medium containing either glucose or Avicel as the carbon source. Neither ∆PoxMBF1 nor ∆PoxKu70 displayed significant differences in growth (Additional file 7: Figure S3).

To determine whether PoxMBF1 was involved in the responses of P. oxalicum to extracellular stress, strains ∆PoxMBF1, ∆PoxKu70, and CPoxMBF1 were inoculated onto potato dextrose agar (PDA) plates containing 1.5 M sorbitol or 1.8 mM H2O2. The results revealed smaller colonies for the ∆PoxMBF1 mutant than ∆PoxKu70 and CPoxMBF1, and colonies of ∆PoxKu70 and CPoxMBF1 were similar (Fig. 4), suggesting that PoxMBF1 deletion resulted in high sensitivity of P. oxalicum to exogenous stress.

Fig. 4.

Phenotypic investigation of P. oxalicum deletion mutant ∆PoxMBF1, parental strain ∆PoxKu70, and complementary strain CPoxMBF1 cultivated under extracellular stress

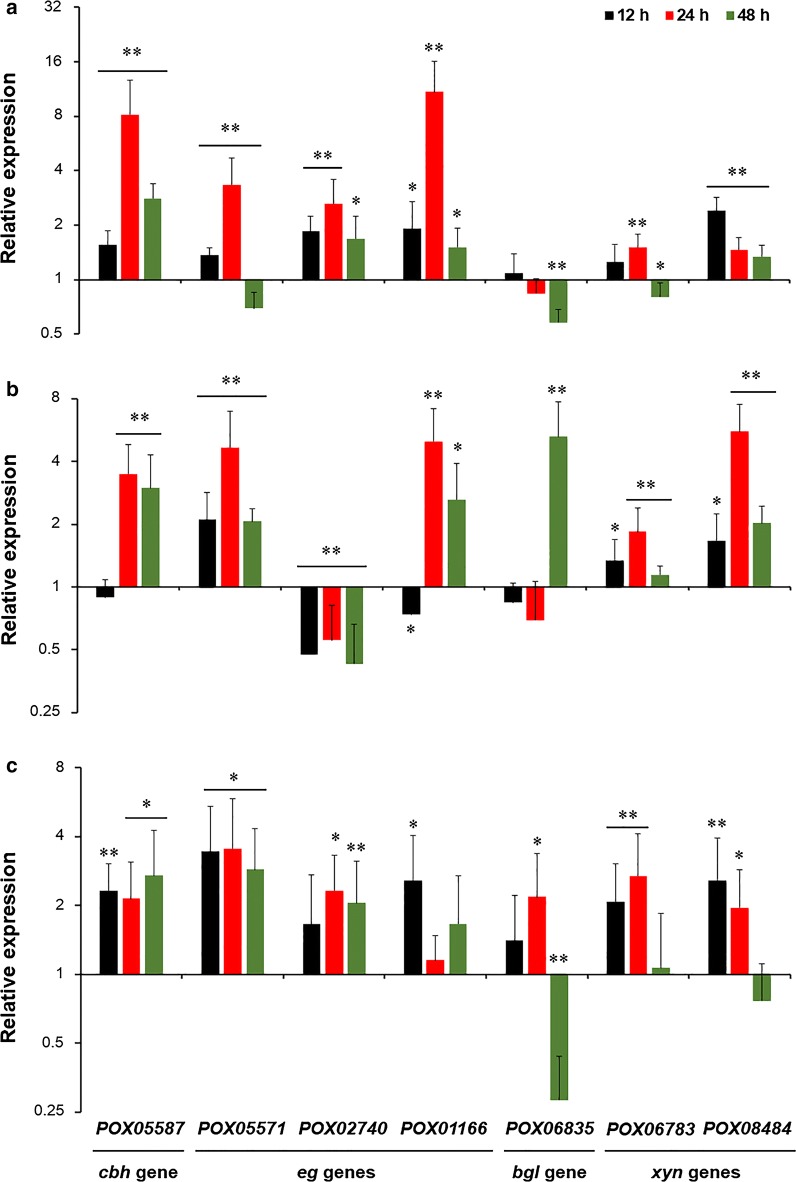

Transcriptional regulation of cellulase and xylanase genes in P. oxalicum by PoxMBF1 during SSF and SmF

PoxMBF1 was found to be involved in cellulase and xylanase production in P. oxalicum, possibly due to alterations in cellulase and xylanase genes at the mRNA level. To explore this further, real-time quantitative reverse-transcription PCR (RT-qPCR) was performed on cbh gene POX05587/Cel7A-2, eg genes POX01166/Cel5B, POX02740 and POX05571/Cel7B, β-glucosidase gene POX06835/Bgl1, and xyn genes POX06783/Xyn11A and POX08484/Xyn11B. The transcriptional levels of these genes were measured in P. oxalicum strains ∆PoxMBF1 and ∆PoxKu70 cultivated under different fermentation conditions at 12, 24, and 48 h after a shift from glucose.

In ∆PoxMBF1 under SSF with WR as the carbon source, transcripts of POX05587/Cel7A-2, POX02740, POX01166/Cel5B, and POX08484/Xyn11B were increased by 33.8–718.3% compared with ∆PoxKu70 during the entire induction period (12–48 h), whereas POX05571/Cel7B and POX06783/Xyn11A transcripts were increased only at 12–24 h or 24 h. Strikingly, transcripts of POX05571/Cel7B, POX06783/Xyn11A and POX06835/Bgl1 were decreased by 19.6–42.1% at 48 h (Fig. 5a). In addition, expression of these cellulase and xylanase genes was also observed in ∆PoxMBF1 and ∆PoxKu70 during SmF using either WR or Avicel as the carbon source. These results indicate that the expression of most of the tested cellulase and xylanase genes was significantly increased in ∆PoxMBF1 compared with ∆PoxKu70 at certain induction periods, although the extent varied with different carbon sources used for induction. For example, transcription of POX05587/Cel7A-2 was increased by 132.6–270.7% after 12–48 h of induction with Avicel, and by 198.7% and 248.5% at 24 and 48 h of induction with WR, respectively (Fig. 5b, c).

Fig. 5.

Transcriptional levels of major cellulase and xylanase genes regulated by PoxMBF1 in P. oxalicum at three timepoints (12, 24, and 48 h) after a shift from glucose. a Solid medium containing WR; b liquid medium containing WR; c liquid medium containing Avicel. All gene expression levels were normalised against the parental strain ∆PoxKu70. ** or * indicates significant differences (p ≤ 0.01 or p ≤ 0.05, respectively) between the deletion mutant ∆PoxMBF1 and parental strain ∆PoxKu70 (Student’s t tests). WR, wheat bran plus rice straw

In vitro binding of PoxMBF1

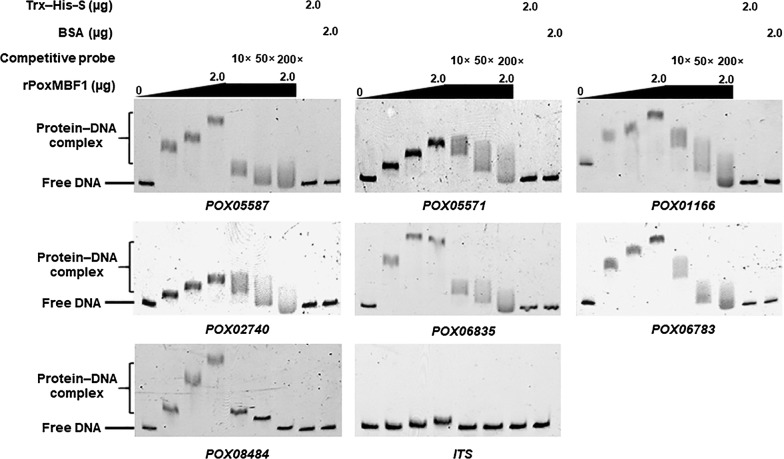

The above results revealed that PoxMBF1 regulates cellulase and xylanase production in P. oxalicum by controlling transcription of cellulase and xylanase genes. To determine whether PoxMBF1 directly or indirectly controls the expression of these genes, in vitro binding experiments were performed. Electrophoretic mobility shift assay (EMSA) results indicated that the rPoxMBF1–DNA complex was formed with each probe, and the concentration and size of each complex gradually increased with increasing quantity of rPoxMBF1 (0–2.0 µg). By contrast, rPoxMBF1 did not bind the fusion protein Trx–His–S, bovine serum albumin (BSA), or the internal transcribed spacer (ITS) sequence controls (Fig. 6). Moreover, when a mixture of 6-carboxyfluorescein (6-FAM)-labelled EMSA probes and competitive probes lacking 6-FAM were loaded into buffer containing a certain amount of rPoxMBF1, a gradual decrease was observed in the concentration and size of complexes with increasing amounts of competitive probes. These results suggest that PoxMBF1 binds specifically to the putative promoters of major cellulase and xylanase genes in P. oxalicum (Fig. 6).

Fig. 6.

In vitro binding experiments using recombinant protein rPoxMBF1 and the promoter regions of target genes. Each EMSA reaction system contained 0–2.0 μg of Trx–His–S-tagged rPoxMBF1 and ~ 40 ng of each candidate probe. The same amounts of purified Trx–His–S fusion protein, BSA, and ITS sequence were, respectively, employed as negative controls

Discussion

In the present study, transcriptional profiling was performed on the soil fungus P. oxalicum cultivated under different fermentation conditions (SSF and SmF), and transcription of genes involved in metabolism and genetic information processing was found to vary. Intriguingly, compared with WR-based SmF, WR-based SSF induced higher expression of major cellulase genes in P. oxalicum, but repressed the transcription of genes involved in the TCA cycle, suggesting that SSF is favourable for fungal cellulase production. Indeed, cellulase and xylanase production was greater in SSF than SmF during both early and intermediate induction periods (Fig. 3). These findings demonstrate the advantages of SSF for cellulase production at the molecular level.

Comparative transcriptomic and genetic analyses identified 14 genes putatively regulating cellulase (FPase) production in P. oxalicum during SSF. However, the roles of these regulatory genes varied; four genes (POX02083, POX05692, POX08292/PoxMBF1, and POX09500) negatively regulated FPase production, while the others positively regulated FPase production. Some of these genes were found to function only during SSF (POX01183, POX03888, and POX06377), SmF (POX01167 and POX03890), or both (PoxMBF1, POX04772, and POX08910) [9, 15], suggesting the presence of distinct regulatory networks that differ in SSF and SmF. Furthermore, detailed investigation of the regulatory role of the novel key TF PoxMBF1 in cellulase and xylanase production in P. oxalicum during SSF and SmF revealed that PoxMBF1 functions by binding directly to the promoter regions of major cellulase and xylanase genes. Thus, PoxMBF1 could be a potential direct target for genetic engineering to improve cellulase and xylanase yields.

The transcriptional co-activator MBF1 is present in a wide variety of organisms including archaea, humans, plants, and filamentous fungi, and plays significant roles in regulating diverse cellular processes. For example, in the plant Arabidopsis thaliana, MBF1 controls development and environmental stress tolerance [17, 18]. Human MBF1 functions in the differentiation of endothelial cells [19]. In Magnaporthe oryzae, MBF1 is involved in vegetative growth, osmotic stress, and virulence [20]. In the present study, MBF1 was found to directly control the expression of cellulase and xylanase genes in the filamentous fungus P. oxalicum.

Notably, MBF1 mediates transcriptional regulation via bridging specific regulatory factors and TATA-box binding protein (TBP) [21]. In insects such as the silkworm Bombyx mori and Drosophila, MBF1 is a transcriptional cofactor that links TBP and the nuclear hormone receptor FTZ-F1 by stimulating FTZ-F1 binding to its recognition site. FTZ-F1 is involved in the activation of the fushi tarazu gene during embryogenesis [21]. Yeast MBF1 mediates the GCN4-dependent transcriptional activation of the HIS3 gene-encoding imidazole-3-phosphate dehydratase by directly binding to TBP and the DNA-binding domain of GCN4 [22]. However, remarkably, no interaction between MBF1 and GCN4 (Cpc1) was detected in M. oryzae [20] or Fusarium fujikuroi [23], suggesting that the biological functions of MBF1 are diverse and dependent on host cells. In addition, human EDF-1, a homolog of MBF1, can bind to calmodulin, which is mediated by Ca2+ concentration and phosphorylation of EDF-1 by protein kinase C [24].

In addition to the MBF1 domain (PF08523), the MBF1 protein includes an HTH XRE-family domain (SM000530), also known as a Cro/C1-type HTH domain (IPR001387), located in the C-terminus, that is annotated as a DNA-binding domain of transcriptional regulators. The HTH XRE domain contains four α-helices, and is responsible for MBF1 function [25–27]. In the present study, purified recombinant rPoxMBF1 protein could directly bind to the promoter regions of major cellulase and xylanase genes in vitro, thereby controlling their transcriptional levels in P. oxalicum. Remarkably, the regulatory role of PoxMBF1 in cellulase and xylanase production in P. oxalicum tended to diminish as fermentation proceeded in both SSF and SmF, and the extent of PoxMBF1 regulation was higher in SSF than SmF. In addition, levels of cellulase and xylanase transcripts varied due to differences in PoxMBF1 regulation under different induction conditions. These findings suggest that PoxMBF1 function is dependent on regulatory networks and host specificity. Nevertheless, further studies are needed to investigate the exact regulatory roles of PoxMBF1 in cellulase and xylanase production in P. oxalicum.

Conclusions

In this study, we revealed differences in transcriptomic regulation in P. oxalicum cultivated under SSF and SmF; WR_SSF induced higher expression of major cellulase genes than WR_SmF, but repressed the transcription of genes involved in the citric acid cycle. A PoxMFB1 null mutant displayed significantly higher cellulase and xylanase production than the parental strain in both SSF and SmF, accompanied by an increase in transcription of a subset of cellulase and xylanase genes via specific binding to their putative promoters. These findings expand our understanding of the regulatory mechanisms of fungal cellulase and xylanase genes during SSF, and could assist genetic engineering of fungal strains with improved cellulase and xylanase yields.

Methods

Microbial strains and media

Fungal strains were maintained on PDA plates at 4 °C for passage. Fungal spores were generated and collected from the PDA plates and incubated for 6 days at 28 °C. In general, fungal spores were resuspended in 0.1% Tween 80, and their concentration was adjusted to 1 × 108/mL.

For enzyme activity assays and RT-qPCR, P. oxalicum strains were directly inoculated onto solid medium containing WR as the carbon source as described previously [4] and cultured for 5 days at 28 °C. WR medium contained 6.0 g of wheat bran, 4.0 g of rice straw, and 20 mL of mineral salt solution (2.5 g/L KH2PO4, 2.5 g/L MgSO4·7H2O, 5.0 g/L yeast extract, 0.1% Tween 80, 5.0 mg/mL FeSO4·7H2O, 1.6 mg/L MnSO4·H2O, 1.4 mg/L ZnSO4·7H2O, and 2.0 mg/L CoCl2; pH 5.0). Raw wheat bran and rice straw were purchased from a local farmer’s market (Nanning, China). All plant materials were dried in an oven at 50 °C overnight, and then milled to 40-mesh particle size for further study. For shift experiments, P. oxalicum spores (1.0 × 108) were precultured in glucose medium comprising 4 g/L (NH4)2SO4, 4 g/L KH2PO4, 0.6 g/L CaCl2, 0.6 g/L MgSO4·7H2O, 0.005 g/L FeSO4·7H2O, 0.0016 g/L MnSO4, 0.0017 g/L ZnCl2, 0.002 g/L CoCl2, 10 g/L glucose, and 1 mL of Tween 80 for 20 h at 28 °C. Subsequently, a defined amount of precultured mycelia was transferred to fresh solid or liquid WR medium and incubated for 2–4 days at 28 °C (for enzyme activity assays) or 12, 24, and 48 h (for RT-qPCR). Crude cellulase solution was extracted from solid and liquid media according to a previous method [4] and by centrifugation, respectively. The resulting mycelia were used for the extraction of total RNA for RT-qPCR or RNA sequencing.

To perform phenotypic investigation, a defined number of fungal spores were inoculated onto PDA plates containing different carbon sources (glucose, WR or Avicel) or chemical agents (H2O2 or sorbitol) for 3–5 days. For RNA sequencing of P. oxalicum strain HP7-1 obtained from the China General Microbiological Culture Collection (CGMCC) 10781, 1 mL of spore suspension at a concentration of 1.0 × 108/mL was inoculated into solid or liquid WR medium and incubated at 28 °C for 24 h under static or shaking conditions, and mycelia were used for total RNA extraction. Escherichia coli cells (TransGen, Beijing, China) were cultivated in Luria–Bertani medium at 37 °C and used for genetic engineering.

Total DNA and RNA extraction

Extraction of total DNA and RNA from P. oxalicum was performed as described previously [3]. The collected mycelia were mechanically ground into powder with liquid nitrogen, mixed with lysate buffer (10.0 mM ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid, 20.0 mM sodium acetate, 1.0% sodium dodecyl sulfate, and 40.0 mM TRIS–HCl; pH 8.0), and used for extracting fungal total DNA. For total RNA extraction, a TRIzol RNA Kit (Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA, USA) was employed according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Electrophoresis on 1% agarose gels and A260/A280 values were used to assess the quantity and quality of extracted DNA and RNA.

RNA sequencing

Total RNA extracted from fungal mycelia cultivated for 24 h was employed for RNA sequencing using an Illumina HiSeq 2000 system. As reported previously [3], a cDNA library was constructed and evaluated with an ABI StepOnePlus Real-Time PCR System (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA) and an Agilent 2100 Bioanalyzer (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA, USA). Each cDNA fragment in the constructed cDNA library was 100 bp in length. After filtering, the obtained clean reads were mapped onto the P. oxalicum HP7-1 genome for functional annotation using BWA v0.7.10-r789 [28] and Bowtie2 v2.1.0 [29]. Levels of gene transcripts were calculated as fragments per kilobase of exon per million mapped reads (FPKM) values using RSEM v1.2.12 [30]. DEGs were screened and selected by comparative analysis using NOISeq [31].

Construction of gene deletion mutant and complementary strains

Deletion mutants of candidate regulatory genes and complementary strain CPoxMBF1 were constructed using P. oxalicum parental strains ∆PoxKu70 and ∆PoxMBF1, respectively, by homologous recombination according to previously described methods [9]. Briefly, ∆PoxKu70 protoplasts were prepared using OM solution comprising 1.2 mM MgSO4·7H2O, 10 mM NaH2PO4, 4 g/L lysozyme, 6 g/L lysing enzymes from Trichoderma harzianum (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA), and 6 g/L snailase (pH 5.8). Knockout cassettes for each candidate gene, comprising ~ 2 kb of DNA sequence upstream and downstream of the target gene and a 1.8 kb DNA fragment encoding the G418 resistance gene, were constructed by recombinant PCR. Subsequently, ~ 2 µg of each knockout cassette was mixed with a defined number of ∆PoxKu70 protoplasts on ice and transferred to plates containing OCM medium comprising 1 g/L casein enzymatic hydrolysate, 1 g/L yeast extract, and 10 g/L agar, and incubated at 50 °C for 30 min. PDA medium containing 250 μg/mL hygromycin B and 500 μg/mL G418 was then poured onto the surface of the OCM medium and incubated for 5 days at 28 °C, and transformants were selected and confirmed.

To further verify that only the PoxMBF1 gene was deleted in the ∆PoxMBF1 mutant compared with the parental strain ∆PoxKu70 and that the phenotypic alteration of ∆PoxMBF1 was due to deletion of PoxMBF1 in ∆PoxKu70, a complementary strain was constructed. A complementary cassette was integrated at the site of aspartic protease gene POX05007 in deletion mutant ∆PoxMBF1, and included ~ 2 kb of DNA sequence upstream and downstream of POX05007, a 1.2 kb DNA fragment encoding the bleomycin resistance gene, and a 4.7 kb complete PoxMBF1 gene containing its promoter, coding region, and terminator. The complementary cassette was introduced into ∆PoxMBF1 protoplasts, and bleomycin was used for selection of complementary transformants.

Enzyme activity assays

Cellulase and xylanase activities of P. oxalicum strains were determined as described previously [3]. Appropriately diluted crude enzyme solution was added to 100 mM citrate buffer (pH 5.0) containing Whatman No. 1 filter paper (50 mg, 1.0 × 6.0 cm2), 1.0% CMC-Na (Sigma-Aldrich, Darmstadt, Germany), and 1.0% xylan from beechwood (Megazyme International Ireland, Wicklow, Ireland) to measure the activities of FPase, CMCase, and xylanase. Assays were incubated for 1 h, 30 min, or 10 min at 50 °C. The concentration of the resulting reducing sugars was determined using DNS reagent comprising 200 g/L potassium sodium tartrate, 0.5 g/L Na2SO3, 10 g/L 3,5-dinitrosalicyclic acid, 20 g/L NaOH, and 2 g/L phenol at 540 nm [32]. One unit (U) of enzyme activity was defined as the amount of enzyme required to produce 1 μmol of reducing sugar per min from the substrate.

Enzyme activities of pNPCase and pNPGase were determined using p-nitrophenyl-β-d-cellobioside and p-nitrophenyl-β-d-glucopyranoside (Sigma-Aldrich) as substrate, respectively, at 50 °C for 15 min, and the resulting p-nitrophenol (pNP) was measured at 410 nm. One unit (U) of enzyme activity was defined as the amount of enzyme required to produce 1 μmol of pNP per min from the substrates. Furthermore, a Detergent Compatible Bradford Assay Kit (Pierce Biotechnology, Rockford, IL, USA) was employed to determine the protein concentration in fungal cells according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

RT-qPCR assays

RT-qPCR was performed as reported previously [3]. Briefly, first-stand cDNA was synthesised using the extracted total fungal RNA as template by employing a PrimeScript RT Reagent Kit (TaKaRa Bio Inc, Dalian, China). Subsequently, the tested DNA fragments were amplified by PCR using the synthesised cDNA as template in a 20 µL reaction containing 0.8 μL of 10 μM primers (Additional file 4: Table S3), 0.2 μL of first-stand cDNA, and 10 μL of SYBR Premix Ex Taq II (TaKaRa Bio Inc.). All reactions were run for 40 cycles at 95 °C for 5 s and 60 °C for 40 s, and fluorescent signals were determined at the end of the extension step at 80 °C. Relative gene expression levels in the ΔPoxMBF1 deletion mutant were calculated using the actin gene POX09428 as an internal control, and normalised against the ΔPoxKu70 parental strain. Each RT-qPCR experiment was performed independently at least three times.

Heterologous expression of PoxMBF1

A DNA fragment encoding the ProMBF1 protein was amplified by PCR with a specific primer pair (Additional file 4: Table S3) and cloned into the pET-32a(+) vector to generate recombinant plasmid pET32-PoxMBF1. This construct was introduced into E. coli Rosetta cells (Transgen Biotech, Beijing, China), and the resulting recombinant strain was first cultured in Luria–Bertani medium for 4 h and then induced with 1.0 mM isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside at 25 °C for 20 h to produce the fusion protein possessing a TRX–His–S tag. The recombinant rPoxMBF1 protein was purified by affinity chromatography on TALON Metal Affinity Resin (Clontech, Palo Alto, CA, USA). TRX–His–S was purified from E. coli cells harbouring the empty pET-32a(+) vector and used as a control.

In vitro binding experiments

To investigate whether the recombinant rPoxMBF1 protein directly binds to the promoter regions of major cellulase and xylanase genes, in vitro EMSA was performed as described previously [9]. DNA fragments (~ 1 kb upstream from the translation initiation ATG codon) labelled with 6-FAM at the 3′-terminus were amplified by PCR using specific primer pairs (Additional file 4: Table S3) and used as EMSA probes. The rPoxMBF1 and EMSA probes were mixed with binding buffer comprising 0.1 mg/mL BSA, 20 mM TRIS–HCl (pH 8.0), 5% glycerol, 50 mM KCl, 1 mM DTT, and 5.4 μg of sheared salmon sperm DNA, at room temperature for 20 min. The mixture was loaded onto a polyacrylamide TRIS–acetic acid–EDTA gel and run at 150 V for 77 min. The resulting protein–DNA complexes were investigated using a ChemiDoc MP imaging system (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, CA, USA). Competitive EMSA was performed as described above using EMSA probes without 6-FAM. Purified TRX–His–S from E. coli cells transformed with the empty pET-32a(+) vector and BSA alone were used as controls, along with the control probe ITS sequence.

Phylogenetic analysis

The PoxMBF1 protein and its homologs (downloaded from the NCBI website) were subjected to phylogenetic analysis using MEGA7.0 [33]. A phylogenetic tree was constructed based on the neighbour-joining method and Poisson correction model. Bootstrap values were calculated from 1000 replicates.

Data analysis and accession numbers

Experimental data were statistically analysed using Student’s t tests in Microsoft Excel within Microsoft Office 2016 (Microsoft, Redmond, WA, USA). Gene expression data and DNA sequences have been deposited in the Sequence Read Archive database (accession numbers SRR8392062–SRR8392067) and the GenBank database (accession numbers MK389644–MK389653), respectively.

Additional files

Additional file 1: Table S1. Summary of RNA-sequencing data generated from P. oxalicum strain HP7-1.

Additional file 2: Table S2. DEGs identified in P. oxalicum strain HP7-1 grown in solid medium containing WR (HP7-1_WR-S) and liquid medium containing WR (HP7-1_WR-L).

Additional file 3: Figure S1. Confirmatory analysis of 25 deletion mutants constructed from the parental strain ΔPoxKu70. (a) Schematic illustration of deletion mutant construction. (b) PCR analysis. M, 1 kb DNA markers; Lanes 1–3, three transformants for each candidate gene; Lane 4, ΔPoxKu70; Lane 5, ddH2O. The top panel shows amplification of the region using primers Gene-Left-F/G418VR; the middle panel shows amplification of the region using primers G418VF/Gene-Right-R; the bottom panel shows amplification of the region of the target gene using primers GeneVF/GeneVR. (c) Southern hybridisation analysis of deletion mutant ΔPOX08292. M, 1 kb DNA markers; Lane 1, ΔPoxKu70; Lane 2, ΔPOX08292-2; Lane 3, ΔPOX08292-6; Lane 4, ΔPOX08292-12.

Additional file 4: Table S3. Primers used in this study.

Additional file 5: Table S4. Candidate regulatory genes knocked out in P. oxalicum.

Additional file 6: Figure S2. Confirmation of complementary strain CPoxMBF1. (a) Schematic illustration of complementary strain construction. (b–g) PCR analysis. M, 1 kb DNA markers; Lane 1, ΔPoxMBF1; Lane 2, ΔPoxKu70; Lanes 3–5, three transformants of CPoxMBF1; (b) PCR using primers bleVF/bleVR; (c) PCR using primers POX05007-V-F/POX05007-V-R; (d) PCR using primers Pro-V-F/Pro-V-R; (e) PCR using primers CPOX08292-F/CPOX08292-R; (f) PCR using primers 5007bleVF/CPOX05007-R–R; (g) PCR using primers CPOX05007-L-F/5007bleVR.

Additional file 7: Figure S3. Growth curve of P. oxalicum mutants ΔPoxMBF1 and ΔPoxKu70 in glucose (a) and Avicel (b) media.

Authors’ contributions

SZ conceived, supervised this study, wrote, and revised the manuscript. JXF codesigned and co-supervised this study, and was involved in the data analysis and manuscript revision. QL carried out measurement of enzymatic activities, RT-qPCR, phenotypic investigation, construction of complementary strain, and in vitro binding experiments. JXW and XZL constructed deletion mutants and PCR confirmation. HG preformed Southern hybridization confirmation of deletion mutant and data analysis. CXL conducted bioinformatic analyses. LSL and XML were involved in preparation of experimental materials and the analysis of experimental data. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Availability of supporting data

Gene expression data and DNA sequences have been deposited in the Sequence Read Archive database (accession numbers SRR8392062–SRR8392067) and the GenBank database (accession numbers MK389644–MK389653), respectively.

Consent for publication

All authors consent for publication.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Funding

This work was financially supported by the grants from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant Nos. 31660305 and 31760023), and the ‘One Hundred Person’ Project of Guangxi.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Abbreviations

- 6-FAM

6-carboxyfluorescein

- BSA

bovine serum albumin

- CMCase

carboxymethylcellulase

- EMSA

electrophoretic mobility shift assay

- DEGs

differentially expressed genes

- FPase

filter paper cellulase

- HP7-1_WR-S

P. oxalicum strain HP7-1 grown in solid medium containing wheat bran plus rice straw

- HP7-1_WR-L

P. oxalicum strain HP7-1 grown in liquid medium containing wheat bran plus rice straw

- PDA

potato dextrose agar

- pNPCase

p-nitrophenyl-β-cellobiosidase

- pNPGase

p-nitrophenyl-β-glucopyranosidase

- RT-qPCR

real-time quantitative reverse-transcription PCR

- SSF

solid-state fermentation

- SmF

submerged fermentation

- TBP

TATA-box binding protein

- TFs

transcriptional factors

- WB

wheat bran

- WR

wheat bran plus rice straw

Contributor Information

Shuai Zhao, Email: shuaizhao0227@gxu.edu.cn.

Qi Liu, Email: 2990852550@qq.com.

Jiu-Xiang Wang, Email: 504025253@qq.com.

Xu-Zhong Liao, Email: 535534559@qq.com.

Hao Guo, Email: 497485701@qq.com.

Cheng-Xi Li, Email: 904375941@qq.com.

Feng-Fei Zhang, Email: 2411533361@qq.com.

Lu-Sheng Liao, Email: 1528746151@qq.com.

Xue-Mei Luo, Email: luoxuemei1003@163.com.

Jia-Xun Feng, Email: jiaxunfeng@sohu.com.

References

- 1.Lizardi-Jiménez MA, Hernández-Martínez R. Solid state fermentation (SSF): diversity of applications to valorize waste and biomass. 3 Biotech. 2017;7:44. doi: 10.1007/s13205-017-0692-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Behera SS, Ray R. Solid state fermentation for production of microbial cellulase: recent advance and improvement strategies. Int J Biol Macromol. 2016;86:656–669. doi: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2015.10.090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zhao S, Yan YS, He QP, Yang L, Yin X, Li CX, Mao LC, Liao LS, Huang JQ, Xie SB, Nong QD, Zhang Z, Jing L, Xiong YR, Duan CJ, Liu JL, Feng JX. Comparative genomic, transcriptomic and secretomic profiling of Penicillium oxalicum HP7-1 and its cellulase and xylanase hyper-producing mutant EU2106, and identification of two novel regulatory genes of cellulase and xylanase gene expression. Biotechnol Biofuels. 2016;9:203. doi: 10.1186/s13068-016-0616-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Su LH, Zhao S, Jiang SX, Liao XZ, Duan CJ, Feng JX. Cellulase with high β-glucosidase activity by Penicillium oxalicum under solid state fermentation and its use in hydrolysis of cassava residue. World J Microbiol Biotechnol. 2017;33:37. doi: 10.1007/s11274-016-2200-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.te Biesebeke R, van Biezen N, de Vos WM, van den Hondel C, Punt PJ. Different control mechanisms regulate glucoamylase and protease gene transcription in Aspergillus oryzae in solid-state and submerged fermentation. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 2005;67:75–82. doi: 10.1007/s00253-004-1807-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Castanera R, Pérez G, Omarini A, Alfaro M, Pisabarro AG, Faraco V, Amore A, Ramírez L. Transcriptional and enzymatic profiling of Pleurotus ostreatus laccase genes in submerged and solid-state fermentation cultures. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2012;78:4037–4045. doi: 10.1128/AEM.07880-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Amore A, Giacobbe S, Faraco V. Regulation of cellulase and hemicellulase gene expression in fungi. Curr Genom. 2013;14:230–249. doi: 10.2174/1389202911314040002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Coradetti ST, Craig JP, Xiong Y, Shock T, Tian CG, Glass NL. Conserved and essential transcription factors for cellulase gene expression in ascomycete fungi. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2012;109:7397–7402. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1200785109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yan YS, Zhao S, Liao LS, He QP, Xiong YR, Wang L, Li CX, Feng JX. Transcriptomic profiling and genetic analyses reveal novel key regulators of cellulase and xylanase gene expression in Penicillium oxalicum. Biotechnol Biofuels. 2017;10:279. doi: 10.1186/s13068-017-0966-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Huberman LB, Liu J, Qin LN, Glass NL. Regulation of the lignocellulolytic response in filamentous fungi. Fungal Biol Rev. 2016;30:101–111. doi: 10.1016/j.fbr.2016.06.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Li ZH, Yao GS, Wu RM, Gao LW, Kan QB, Liu M, Yang P, Liu GD, Qin YQ, Song X, Zhong YH, Fang X, Qu YB. Synergistic and dose-controlled regulation of cellulase gene expression in Penicillium oxalicum. PLoS Genet. 2015;11:e1005509. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1005509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chen L, Zou G, Zhang L, de Vries RP, Yan X, Zhang J, Liu R, Wang CS, Qu YB, Zhou ZH. The distinctive regulatory roles of PrtT in the cell metabolism of Penicillium oxalicum. Fungal Genet Biol. 2014;63:2–54. doi: 10.1016/j.fgb.2013.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kunitake E, Hagiwara D, Miyamoto K, Kanamaru K, Kimura M, Kobayashi T. Regulation of genes encoding cellulolytic enzymes by Pal-PacC signaling in Aspergillus nidulans. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 2016;100:3621–3635. doi: 10.1007/s00253-016-7409-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Xiong Y, Sun JP, Glass NL. VIB1, a link between glucose signaling and carbon catabolite repression, is essential for plant cell wall degradation by Neurospora crassa. PLoS Genet. 2014;10:e1004500. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1004500. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Xiong YR, Zhao S, Fu LH, Liao XZ, Li CX, Yan YS, Liao LS, Feng JX. Characterization of novel roles of a HMG-box protein PoxHmbB in biomass-degrading enzyme production by Penicillium oxalicum. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 2018;102:3739–3753. doi: 10.1007/s00253-018-8867-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zhang MY, Zhao S, Ning YN, Fu LH, Li CX, Wang Q, You R, Wang CY, Xu HN, Luo XM, Feng JX. Identification of an essential regulator controlling the production of raw starch-digesting glucoamylase in Penicillium oxalicum. Biotechnol Biofuels. 2019;12:7. doi: 10.1186/s13068-018-1345-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Suzuki N, Bajad S, Shuman J, Shulaev V, Mittler R. The transcriptional co-activator MBF1c is a key regulator of thermotolerance in Arabidopsis thaliana. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:9269–9275. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M709187200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Suzuki N, Rizhsky L, Liang HJ, Shuman J, Shulaev V, Mittler R. Enhanced tolerance to environmental stress in transgenic plants expressing the transcriptional coactivator multiprotein bridging factor 1c. Plant Physiol. 2005;139:1313–1322. doi: 10.1104/pp.105.070110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Leidi M, Mariotti M, Maier JA. The effects of silencing EDF-1 in human endothelial cells. Atherosclerosis. 2010;211:55–60. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2010.01.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fan GL, Zhang K, Huang H, Zhang H, Zhao A, Chen LB, Chen RQ, Li GP, Wang ZH, Lu GD. Multiprotein-bridging factor 1 regulates vegetative growth, osmotic stress, and virulence in Magnaporthe oryzae. Curr Genet. 2017;63:293–309. doi: 10.1007/s00294-016-0636-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Takemaru K, Li FQ, Ueda H, Hirose S. Multiprotein bridging factor 1 (MBF1) is an evolutionarily conserved transcriptional coactivator that connects a regulatory factor and TATA element-binding protein. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:7251–7256. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.14.7251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Takemaru K, Harashima S, Ueda H, Hirose S. Yeast coactivator MBF1 mediates GCN4-dependent transcriptional activation. Mol Cell Biol. 1998;18:4971–4976. doi: 10.1128/MCB.18.9.4971. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Schönig B, Vogel S, Tudzynski B. Cpc1 mediates cross-pathway control independently of Mbf1 in Fusarium fujikuroi. Fungal Genet Biol. 2009;46:898–908. doi: 10.1016/j.fgb.2009.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Maritotti M, de Benedictis L, Avon E, Maier JAM. Interaction between endothelial differentiation-related factor-1 and calmodulin in vitro and in vivo. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:24047–24051. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M001928200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.de Koning B, Blombach F, Wu H, Brouns SJ, van der Oost J. Role of multiprotein bridging factor 1 in archaea: bridging the domains? Biochem Soc Trans. 2009;37:52–57. doi: 10.1042/BST0370052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ozaki J, Takemaru K, Ikegami T, Mishima M, Ueda H, Hirose S, Kabe Y, Handa H, Shirakawa M. Identification of the core domain and the secondary structure of the transcriptional coactivator MBF1. Genes Cells. 2001;4:415–424. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2443.1999.00267.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mishima M, Ozaki J, Ikegami T, Kabe Y, Goto M, Ueda H, Hirose S, Handa H, Shirakawa M. Resonance assignments, secondary structure and 15N relaxation data of the human transcriptional coactivator hMBF1 (57–148) J Biomol NMR. 1999;14:373–376. doi: 10.1023/A:1008347729176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Li H, Durbin R. Fast and accurate short read alignment with Burrows–Wheeler transform. Bioinformatics. 2009;25:1754–1760. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Langmead B, Salzberg SL. Fast gapped-read alignment with Bowtie 2. Nat Methods. 2012;9:357–359. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1923. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Li B, Dewey CN. RSEM: accurate transcript quantification from RNA-Seq data with or without a reference genome. BMC Bioinform. 2011;12:323. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-12-323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Huber W, Carey VJ, Gentleman R, Anders S, Carlson M, Carvalho BS, Bravo HC, Davis S, Gatto L, Girke T, Gottardo R, Hahne F, Hansen KD, Irizarry RA, Lawrence M, Love MI, MacDonald J, Obenchain V, Oleś AK, Pagès H, Reyes A, Shannon P, Smyth GK, Tenenbaum D, Waldron L, Morgan M. Orchestrating high-throughput genomic analysis with bioconductor. Nat Methods. 2015;12:115–121. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.3252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Miller GL. Use of dinitrosalicylic acid reagent for determination of reducing sugar. Anal Chem. 1959;31:426–428. doi: 10.1021/ac60147a030. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kumar S, Stecher G, Tamura K. MEGA7: molecular evolutionary genetics analysis version 7.0 for bigger datasets. Mol Biol Evol. 2016;33:1870–1874. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msw054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Additional file 1: Table S1. Summary of RNA-sequencing data generated from P. oxalicum strain HP7-1.

Additional file 2: Table S2. DEGs identified in P. oxalicum strain HP7-1 grown in solid medium containing WR (HP7-1_WR-S) and liquid medium containing WR (HP7-1_WR-L).

Additional file 3: Figure S1. Confirmatory analysis of 25 deletion mutants constructed from the parental strain ΔPoxKu70. (a) Schematic illustration of deletion mutant construction. (b) PCR analysis. M, 1 kb DNA markers; Lanes 1–3, three transformants for each candidate gene; Lane 4, ΔPoxKu70; Lane 5, ddH2O. The top panel shows amplification of the region using primers Gene-Left-F/G418VR; the middle panel shows amplification of the region using primers G418VF/Gene-Right-R; the bottom panel shows amplification of the region of the target gene using primers GeneVF/GeneVR. (c) Southern hybridisation analysis of deletion mutant ΔPOX08292. M, 1 kb DNA markers; Lane 1, ΔPoxKu70; Lane 2, ΔPOX08292-2; Lane 3, ΔPOX08292-6; Lane 4, ΔPOX08292-12.

Additional file 4: Table S3. Primers used in this study.

Additional file 5: Table S4. Candidate regulatory genes knocked out in P. oxalicum.

Additional file 6: Figure S2. Confirmation of complementary strain CPoxMBF1. (a) Schematic illustration of complementary strain construction. (b–g) PCR analysis. M, 1 kb DNA markers; Lane 1, ΔPoxMBF1; Lane 2, ΔPoxKu70; Lanes 3–5, three transformants of CPoxMBF1; (b) PCR using primers bleVF/bleVR; (c) PCR using primers POX05007-V-F/POX05007-V-R; (d) PCR using primers Pro-V-F/Pro-V-R; (e) PCR using primers CPOX08292-F/CPOX08292-R; (f) PCR using primers 5007bleVF/CPOX05007-R–R; (g) PCR using primers CPOX05007-L-F/5007bleVR.

Additional file 7: Figure S3. Growth curve of P. oxalicum mutants ΔPoxMBF1 and ΔPoxKu70 in glucose (a) and Avicel (b) media.

Data Availability Statement

Gene expression data and DNA sequences have been deposited in the Sequence Read Archive database (accession numbers SRR8392062–SRR8392067) and the GenBank database (accession numbers MK389644–MK389653), respectively.