Abstract

Background

The search of useful serum biomarkers for the early detection of cervical cancers has been of a high priority. The activation of Macrophage-Colony Stimulating Factor (M-CSF) and Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor (VEGF) is likely involved in the pathogenesis and spread of cancer. We compared the plasma levels of M-CSF and VEGF to the ones of commonly accepted tumor markers CA 125and SCC-Ag in three groups of patients: 1. the cervical cancer group (patients with either squamous cell carcinoma or adenocarcinoma); 2. the cervical dysplasia group; 3. the control group.

Methods

This cohort study included 100 patients with cervical cancer and 55 patients with cervical dysplasia. The control group consisted of 50 healthy volunteers. The plasma levels of VEGF and M-CSF were determined using ELISA, while CA 125 and SCC-Ag concentrations were obtained by the chemiluminescent microparticle immunoassay (CMIA).

Results

The median levels of M-CSF and VEGF as well as CA 125 and SCC-Ag in the entire group of cervical cancer patients, were significantly different compared to the healthy women group. In case of both the squamous cell carcinoma and the adenocarcinoma groups, plasma levels of M-CSF and VEGF were higher compared to the control group. No significant differences in the studied parameters between the squamous cell carcinoma and the adenocarcinoma group were observed. The highest sensitivity and specificity were obtained for VEGF (81.18 and 76.00%, respectively) and SCC-Ag (81.18%; 74.00%) in the squamous cell carcinoma group and for VEGF (86.67%; 76.00%) in the adenocarcinoma group. The area under the ROC curve for VEGF was the largest in the adenocarcinoma group followed by the squamous cell carcinoma group (0.9082 and 0.8566 respectively).

Conclusions

Obtained results indicate a possible clinical applicability and a high diagnostic power for the combination of MSC-F, VEGF, CA 125 and SCC-Ag in the diagnosis of both studied types of cervical cancer.

Keywords: M-CSF, VEGF, Cervical cancer, Serum marker, Tumor marker, Squamous cell carcinoma, Adenocarcinoma

Background

Cervical cancer remains one of the most common type of cancer worldwide and the third cause of death among women in developing countries [1]. What is important, it is characterized by a long period of preclinical disease progression through a number of well-defined pre-cancerous cervical intraepithelial neoplasia (CIN) grades I through III [2]. It has been established that the global introduction of cervical cytology as the preferred screening method resulted in a significant decrease of cervical cancer incidence [3, 4]. Nevertheless, malignancies of the cervix remain an important health issue in the developing countries. Pap smears, although a gold standard in the prevention of cervical cancer, has insufficient sensitivity. The high rate of false negative results of cervical cytology leads to the misdiagnosis of many cervical cancer patients [5]. Currently, an additional HPV (Human Papilloma Virus) - genotyping screening program has been introduced to improve the diagnostic sensitivity [6–8]. However, due to high cost- inputs, new markers are still being sought for early diagnosis of cervical cancer [9–11]. Despite the aggressive operative and systemic treatment procedures, the outlook remains unfavorable for patients with advanced stages of the disease [12]. Therefore, there is an important clinical implication for early diagnosis of cervical cancer and evaluation of overall prognosis [13].

Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor (VEGF) family constitutes one of the most important signaling pathways associated with angiogenesis in the development of malignant disease. VEGF, a dimeric glycoprotein of 34–42 kDa, is expressed by a variety of normal cells and malignant tumors, where it can be secreted by the tumor cells themselves or by stromal cells [14]. In particular, its expression is demonstrated to be correlated to hypoxia [15]. Initial studies have found that anti- VEGF treatment induces vascular regression and consequently is effective in inhibiting tumor growth and metastasis [16, 17]. It has been confirmed by other studies that VEGF plays an important role in the development of breast [18–21], reproductive organ [22–24] and ovarian cancer [25–27].

As the major steps in the development of the studied cervical cancer histotypes are commonly known, the role of chronic inflammation process in cancer invasion has been extensively studied. However, there is still lack of plasma markers identifying the biological processes leading to advanced disease in an early clinical grading [28]. The Macrophage-Colony Stimulating Factor (M-CSF) is one of the cytokines called hematopoietic growth factors (HGFs) and regulates the macrophage homeostasis, primarily the growth, differentiation and function. It has been demonstrated that overexpression of various chemotactic and growth factors such as M-CSF leads to recruitment of tumor-associated macrophages (TAMs) in different types of cancers and can stimulate cancer cell proliferation and/or migration. Studies also indicate crucial role of M-CSF in tumor development, while M-CSF receptor (M-CSFR) signaling inhibitors have the potential to effectively suppress the primary tumor growth, tumor angiogenesis and disorganize extracellular matrix [29–31].

The aim of this study was to determine the plasma levels of M-CSF and VEGF in comparison to known tumor markers CA 125 (Cancer Antigen 125) and SCC-Ag (Squamous Cell Carcinoma Antigen) in patients with 2 different types of cervical cancer (squamous cell carcinoma and adenocarcinoma) in relation to the patients with cervical dysplasia and the control group consisting of healthy subjects.

Methods

Human subjects

The study comprised 85 patients with squamous cell carcinoma, 15 patients with adenocarcinoma and 55 patients with cervical dysplasia who were referred to the Department of Gynaecology, Bialystok Medical University Teaching Hospital, Poland (Table 1). The clinical staging was determined in accordance with 2014 International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics (FIGO) criteria in all cases [32]. Histological evaluation of the obtained samples was performed concordantly with the recent recommendations from the College of American Pathologists and the American Society for Colposcopy and Cervical Pathology [33]. Ethical approval for the study was obtained originally from the local Ethics Committee at the Medical University of Bialystok, Poland (R-I-002/239/2014). Before the study entry all patients participating in the study read and signed forms of informed consent specifically approved for this project by the Ethics Committee. The groups were homogeneous and did not differ regarding the menopausal status. No inflammation process was confirmed by laboratory tests (CRP, leukocytosis) and physical examination. All samples were taken prior to any treatment and any medication was not accepted at the time of blood sample collection. The control group included 50 healthy and untreated women (aged 22–61 years). The included patients were not referred from other medical centers. The gynecological exam, a reproductive organ ultrasound scan and a cervical smear were performed.

Table 1.

Characteristics of cervical cancer, dysplasia patients and control group

| Studygroup | Number of patients | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Examined Groups | Cervical cancer patients | Squamous cell carcinoma | 85 |

| Adenocarcinoma | 15 | ||

| Median age (range) | 46 (25-61) | ||

| Tumor stage | I | 32 | |

| II | 33 | ||

| III+IV | 35 | ||

| Menopausal status: | |||

| - premenopausal | 78 | ||

| - postmenopausal | 22 | ||

| Cervical dysplasia patients | 55 | ||

| Median age (range) | 44 (23-60) | ||

| CIN stage | CIN1 | 15 | |

| CIN2 | 20 | ||

| CIN3 | 20 | ||

| Menopausal status: | |||

| - premenopausal | 33 | ||

| - postmenopausal | 22 | ||

| Control Group | Healthy women | 50 | |

| Median age (range) | 42 (22-61) | ||

| Menopausal status: | |||

| - premenopausal | 40 | ||

| - postmenopausal | 10 | ||

Plasma collection and storage

Venous blood was collected from each patient into a heparin sodium tube as previously [34, 35], centrifuged at 3500 rpm for 20 min to obtain plasma samples, and stored until assayed.

Measurement of M-CSF, VEGF, CA 125 and SCC-ag

The tested cytokines (M-CSF, VEGF) were measured in plasma with enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) (Quantikine Human M-CSF Immunoassay; R&D systems, Abingdon, United Kingdom), according to the manufacturer’s protocols (Fig.1). Plasma concentrations of CA 125 and SCC-Ag were measured by chemiluminescent microparticle immunoassay (CMIA) (Abbott, Chicago, IL, USA). Duplicate samples were assessed for each standard, control, and sample. The value of intra- and inter- assay CVs were calculated by the manufacturers and enclosed in the reagent kits. The assay does not exhibit cross-reactivity or interference with numerous human cytokines and other growth factors [34].

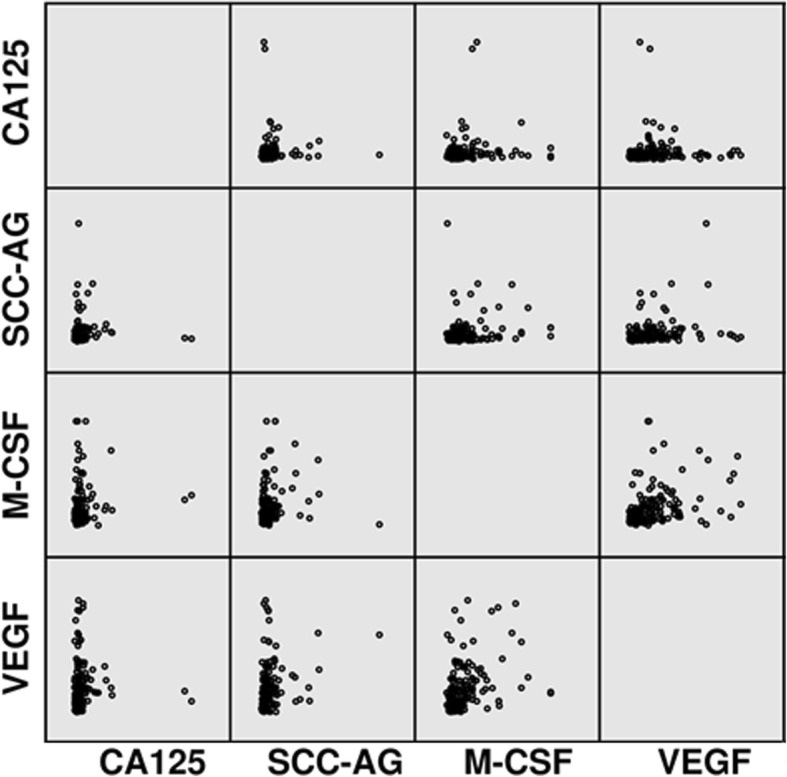

Fig. 1.

Scatterplots of the studied parameters

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed by IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows 20.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA). The Shapiro-Wilk test for preliminary assessment revealed that the cytokine and tumor marker levels did not follow normal distribution. Consequently, statistical analysis between the groups was performed by using the U-Mann Whitney test, the Kruskal-Wallis test and a multivariate analysis of various data by the post-hoc Dwass-Steele-Crichlow-Flinger test [36, 37]. The data were presented as a median and a range. An exploratory, hypothesis generating study was conducted where associations were deemed suggestive if the p- value was less than 0.05. Diagnostic sensitivity (SE) and specificity (SP) were calculated by using cut-off values which were calculated by the Youden’s index (as a criterion for selecting the optimum cut-off point) [38] and for each of the tested parameters were as follows: M-CSF – 397.65 pg/mL; VEGF – 88.46 pg/mL; CA 125–39.30 U/mL; SCC-Ag – 1.25 ng/mL.To estimate total diagnostic value of more than one variable, their linear combinations based on logistic regression model were calculated, and these one-dimensional combinations were used in ROC (Receiver Operator Characteristic) analyses (Table 2). For the diagnostic performance (sensitivity, specificity) and ROC curve, only healthy subjects were used as the control group. All the calculations related to ROC analyses including the construction of the ROC curves were performed using Microsoft Excel 2010 software following the methodology described in literature.

Table 2.

The linear combinations of studied parameters

| Variables | Linear combination |

|---|---|

| CA125, MCSF | -1.281 - 0.00677 * CA125 + 0.00531 * MCSF |

| CA125, VEGF | -1.719 - 0.00353 * CA125 + 0.0261 * VEGF |

| SCCAG, MCSF | -4.428 + 3.22 * SCCAG + 0.00475 * MCSF |

| SCCAG, VEGF | -4.438 + 2.80 * SCCAG + 0.0244 * VEGF |

| CA125, SCCAG, MCSF | -4.539 - 0.00758 * CA125 + 3.26 * SCCAG + 0.00547 * MCSF |

| CA125, SCCAG, VEGF | -4.390 - 0.00385 * CA125 + 2.81 * SCCAG + 0.0250 * VEGF |

Results

Table 3 presents the medians and ranges for the investigated plasma levels of M-CSF, VEGF, CA 125 and SCC-Ag in studied groups (Table 3). The medians of M-CSF, VEGF, CA 125 and SCC-Ag (500.55 pg/ml,142.00 pg/ml,17.60 U/ml, and 1.20 ng/ml respectively) in cervical cancer indicated suggestive differences when compared to the healthy women group (251.50 pg/ml;45.80 pg/ml;11.70 U/ml and 0.75 ng/ml respectively) (p < 0.05). In case of the squamous cell carcinoma and adenocarcinoma groups, differences in plasma levels of M-CSF and VEGF were observed. CA 125 and SCC-Ag median values were statistically different between the squamous cell carcinoma patients and the healthy patients. In contrast, there were no significant differences observed in CA 125 concentrations in the adenocarcinoma patients compared to the control group. Additionally, levels of all tested markers in the squamous cell carcinoma group and total cervical cancer group were notably higher than in the dysplasia group (medians for M-CSF, VEGF, CA 125 and SCC-Ag were 312.34 pg/ml, 62.60 pg/ml, 14.90 U/ml and 0.8 ng/ml respectively) (p < 0.001). No statistical differences were observed between the concentration of any of the tested parameters in patients with CIN I, CIN II, CIN III and the control group. Only M-CSF median was significantly higher in the cervical dysplasia group compared to the control group. We also did not note any difference in plasma level of tested parameters between the two studied groups of cervical cancer.

Table 3.

Plasma levels of tested parameters and CA 125 and SCC-Ag in patients with cervical cancer, dysplasia patients and in control group (median and range)

| M-CSF (pg/mL) | VEGF (pg/mL) | CA 125 (U/mL) | SCC-Ag (ng/mL) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cervical cancer | Squamous cell carcinoma | 510.55a/b/e 102.15–2513.75 |

140.20a/b/c/e 11.80–577.22 |

17.99a/e 4.40–120.10 |

1.20 a/b/c/e 0.50–14.10 |

| Adenocarcinoma | 442.41a/b 95.23–1696.65 |

158.88a/b/e 56.76–615.50 |

15.50 6.34–77.41 |

1.30a 0.70–7.10 |

|

| Total | 500.55 a/e 95.23–2513.75 |

142.00 a/e 11.80–615.50 |

17.60 a/e 4.40–120.10 |

1.20 a/e 0.50–14.10 |

|

| CIN grade | CIN I | 132.40 11.80–615.50 |

47.40 28.20–407.22 |

132.40 11.80–615.50 |

0.74 0.58–0.87 |

| CIN II | 136.90 28.92–395.60 |

48.94 16.90–467.10 |

136.90 28.92–395.60 |

0.70 0.55–1.00 |

|

| CIN III | 199.00 44.50–598.50 |

111.50 27.12–426.86 |

199.00 44.50–598.50 |

0.85 0.65–1.40 |

|

| Total | 312.34 a 126.20–1830.20 |

62.60 16.90–467.10 |

14.90 2.53–78.30 |

0.80 0.30–5.20 |

|

| Control group | 251.50 d/e 119.63–935.29 |

45.80 d 11.20–194.50 |

11.70 3.50–366.00 |

0.75 0.40–1.60 |

|

CA 125: cancer antigen 125; SCC-Ag: squamous cell carcinoma antigen; M-CSF: macrophage-colony stimulating factor; VEGF: vascular endothelial growth factor

aStatistically significant when compared with controls

bStatistically significant when compared with patients with CIN I

cStatistically significant when compared with patients with CIN II

dStatistically significant when compared with patients with CIN III

eStatistically significant when compared with patients with total CIN group

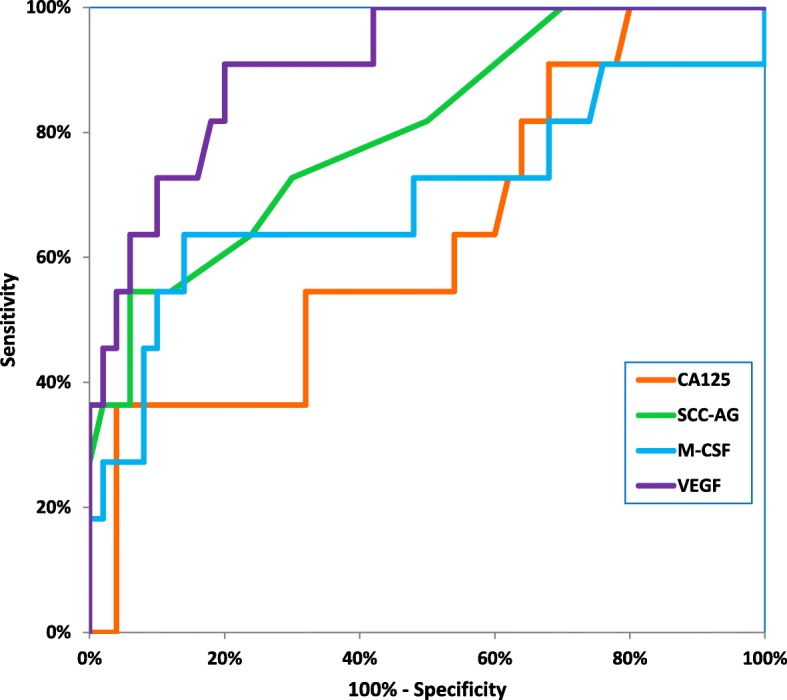

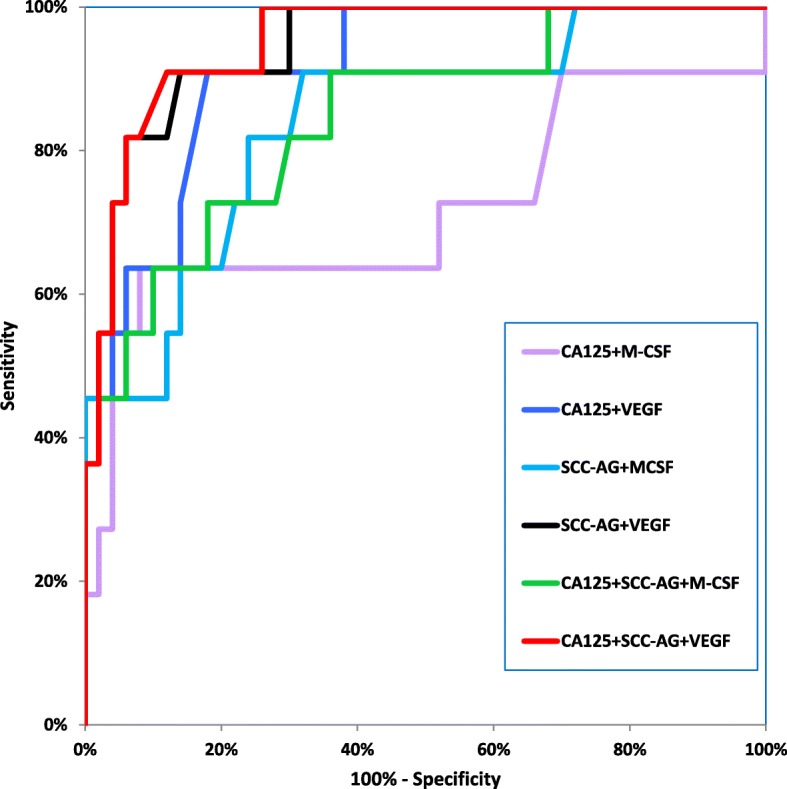

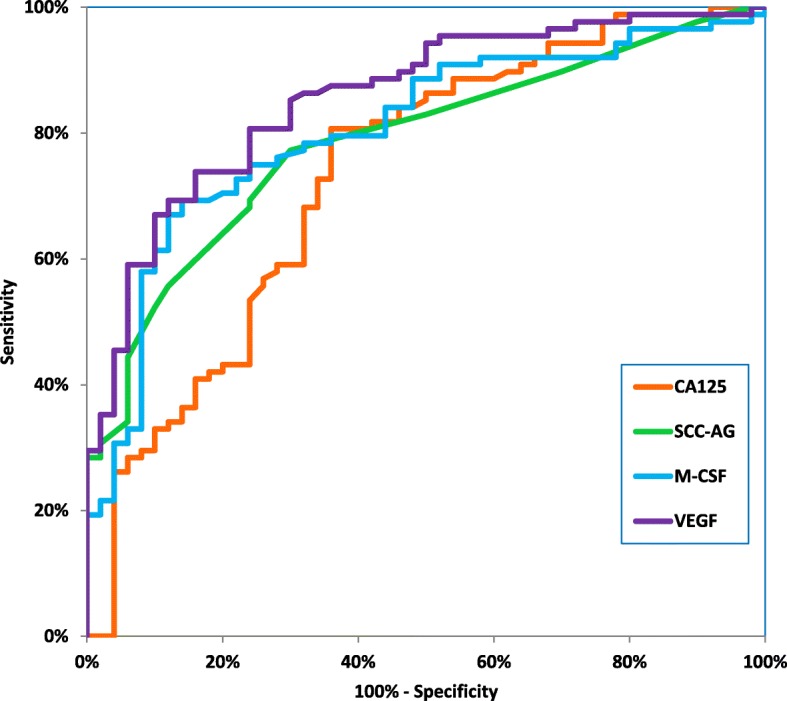

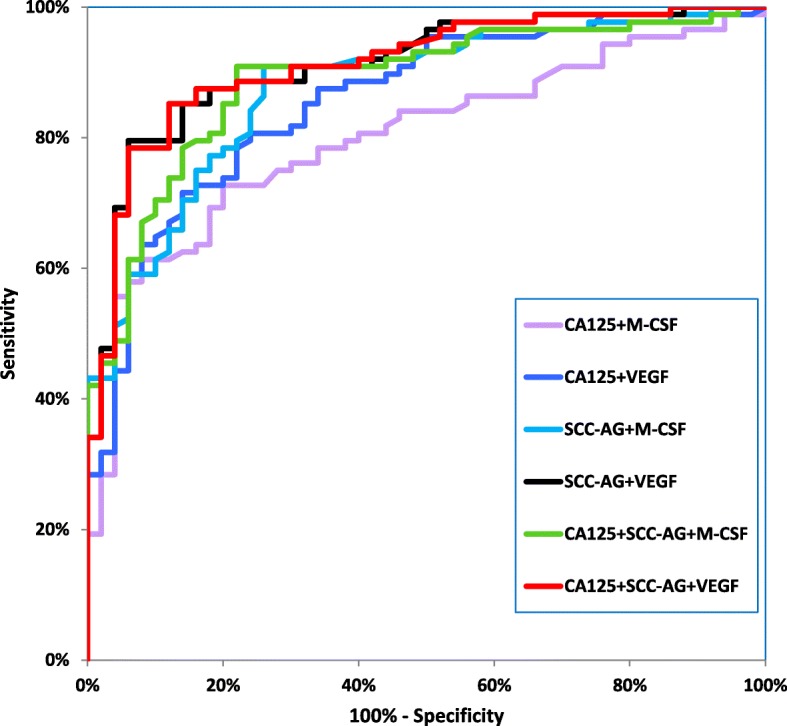

Table 4 shows the following diagnostic criteria: sensitivity (SE) and specificity (SP), in patients with the two histological types of cervical cancer-squamous cell carcinoma and adenocarcinoma (Table 4). We indicated that the SE of tested parameters in the squamous cell carcinoma group was the highest for VEGF and SCC-Ag (81.18%)- higher than that for CA 125 (80.00%) and M-CSF (69.41%) (Fig. 2). When considering the adenocarcinoma group the highest SE value was presented by VEGF (86.67%), and the lowest by SCC-Ag (53.33%), while both CA 125 and M-CSF demonstrated 66.67% (Fig. 3). It is worth noting that in the both cervical cancer groups evaluated as one, the highest SE was also presented by VEGF (82.00%). As displayed in the Table 4, the highest SP value was demonstrated by M-CSF for squamous cell carcinoma group and for adenocarcinoma group (86.00%). The combined use of the tested parameters with CA 125 antigen or SCC-Ag resulted in an increase in SE, but it did not improve the SP in either of the two cervical cancer groups (Fig.4, Fig. 5). The highest values of diagnostic criteria were obtained for the combination of VEGF with CA 125 and SCC-Ag for squamous cell carcinoma, adenocarcinoma and total cervical cancer group.

Table 4.

Diagnostic criteria of tested parameters and in combined analysis with CA 125 and Scc-Ag in cervical cancer patients

| Tested parameters | Diagnostic criteria (%) | Cervical Cancer | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Squamous cell carcinoma | Adenocarcinoma | TOTAL | ||

| M- CSF | SE | 69.41% | 66.67% | 69.00% |

| SP | 86.00% | 86.00% | 86.00% | |

| VEGF | SE | 81.18% | 86.67% | 82.00% |

| SP | 76.00% | 76.00% | 76.00% | |

| CA 125 | SE | 80.00% | 66.67% | 78.00% |

| SP | 68.00% | 68.00% | 68.00% | |

| SCC-Ag | SE | 81.18% | 53.33% | 77.00% |

| SP | 74.00% | 74.00% | 74.00% | |

| M-CSF + CA 125 | SE | 91.76% | 86.67% | 91.00% |

| SP | 66.00% | 66.00% | 66.00% | |

| M-CSF + SCC-Ag | SE | 91.76% | 86.67% | 91.00% |

| SP | 66.00% | 66.00% | 66.00% | |

| M-CSF + CA 125 + SCC-Ag | SE | 98.82% | 93.33% | 98.00% |

| SP | 44.00% | 44.00% | 44.00% | |

| VEGF+CA 125 | SE | 95.29% | 93.33% | 95.00% |

| SP | 52.00% | 52.00% | 52.00% | |

| VEGF+SCC-Ag | SE | 96.47% | 93.33% | 96.00% |

| SP | 60.00% | 60.00% | 60.00% | |

| VEGF+CA 125 + SCC-Ag | SE | 100.00% | 100.00% | 100.00% |

| SP | 36.00% | 36.00% | 36.00% | |

Fig. 2.

Diagnostic criteria of ROC curve for tested parameters in adenocarcinoma cervical cancer group

Fig. 3.

Diagnostic criteria of ROC curve for tested parameters in combination with CA 125 and SCC-Ag in adenocarcinoma cervical cancer group

Fig. 4.

Diagnostic criteria of ROC curve for tested parameters in squamous cell cervical cancer group

Fig. 5.

Diagnostic criteria of ROC curve for tested parameters in combination with CA 125 and SCC-Ag in squamous cell cervical cancer group

The relationship between the diagnostic SE and SP is illustrated by the ROC curve. The AUC indicates the clinical applicability of a tumor marker as a diagnostic tool. Table 5 shows the results of our in-depth analysis of the AUC for all the studied biomarkers separately and in different combinations in the two examined cervical cancer groups (Table 5). The VEGF area under the ROC curve was the largest in the both adenocarcinoma group and squamous cell carcinoma (0.9082 and 0.8566). Interestingly, AUC values for CA 125 were the lowest (0.7340 and 0.6309, respectively) among all tested parameters. Considering the squamous cell carcinoma group, AUC of all the tested parameters was significantly larger in comparison to AUC = 0.5 (borderline of the diagnostic usefulness of the test) (p < 0.001 in all cases), instead of adenocarcinoma group where the AUC of M-CSF did not reach statistical significance comparing to AUC = 0.5 (p = 0.0762). Additionally, the combination of M-CSF or VEGF with CA 125 demonstrated AUC similar to that of these parameters separately. The addition of SCC-Ag to diagnostic panel improved the AUC value in both groups. VEGF in conjunction with both conventional tumor markers achieved the closest results to histopathological diagnosis as a marker of squamous cell carcinoma (0.9120) and adenocarcinoma (0.9509).

Table 5.

Diagnostic criteria of ROC curve for tested parameters and CA 125 and SCC-Ag

| Tested parameters | Squamous cell carcinoma | Adenocarcinoma | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AUC | SE | 95% C.I. (AUC) | p (AUC = 0.5) | AUC | SE | 95% C.I. (AUC) | p (AUC = 0.5) | |

| M-CSF | 0.8051 | 0.0383 | (0.730–0.880) | <0.001 | 0.6973 | 0.1113 | (0.479–0.915) | 0.0762 |

| VEGF | 0.8566 | 0.0321 | (0.794–0.920) | <0.001 | 0.9082 | 0.0447 | (0.821–0.996) | <0.001 |

| CA 125 | 0.7340 | 0.0461 | (0.644–0.824) | <0.001 | 0.6309 | 0.0974 | (0.440–0.822) | 0.0179 |

| SCC-Ag | 0.7866 | 0.0383 | (0.711–0.862) | <0.001 | 0.8018 | 0.0765 | (0.652–0.952) | <0.001 |

| M-CSF+ CA 125 | 0.8006 | 0.0376 | (0.727–0.874) | <0.001 | 0.7164 | 0.1121 | (0.497–0.936) | 0.0536 |

| M-CSF+ SCC-Ag | 0.8760 | 0.0296 | (0.818–0.934) | <0.001 | 0.8427 | 0.0698 | (0.706–0.980) | <0.001 |

| M-CSF+ CA 125+ SCC-Ag | 0.8869 | 0.0287 | (0.831–0.943) | <0.001 | 0.8464 | 0.0692 | (0.711–0.982) | <0.001 |

| VEGF+ CA 125 | 0.8576 | 0.0322 | (0.795–0.921) | <0.001 | 0.9127 | 0.0417 | (0.831–0.995) | <0.001 |

| VEGF+ SCC-Ag | 0.9109 | 0.0250 | (0.862–0.960) | <0.001 | 0.9445 | 0.0320 | (0.882–1.005) | <0.001 |

| VEGF+ CA 125+ SCC-Ag | 0.9120 | 0.0249 | (0.863–0.961)- | <0.001 | 0.9509 | 0.0286 | (0.895–1.007) | <0.001 |

Discussion

Great efforts have been made to identify novel biomarkers aiming at improving the detection of the invasive cervical cancer at the earliest possible stage [2]. Such tumor markers will be molecules arising from the presence of a tumor, which can appear in the surrounding tissue, and then within the blood [11, 13]. Thus, we hypothesized that the cytokines participating in angiogenesis and tumor invasion may be useful in early detection of the cancerous changes. The studied parameters appear to be effective in potential diagnosis of the analyzed histotypes of cervical cancer [39–41]. Although we did not observed any significant changes in the analyzed serum markers between the squamous cell carcinoma and adenocarcinoma group, which is consistent with other study [42], all the analyses were performed separately for the two groups. In this research, we demonstrated significantly higher plasma concentrations of VEGF, M-CSF, CA 125 and SCC-Ag in the squamous cell carcinoma group and VEGF, M-CSF, SCC-Ag in the adenocarcinoma group compared to the healthy women.

Comparable results for VEGF were obtained by Srivastava et al. [43], Zusterzeel et al. [42] and Du et al. [44] where positive correlation between the serum VEGF level, tumor stage and its size was found. On the other hand, Katanyoo et al. demonstrated that the pretreatment serum levels of VEGF in cervical cancer patients do not correlate with stage and tumor characteristic [45]. This discrepancy between the results is probably the effect of different composition and size of the studied groups. Applicability of serum VEGF has been confirmed in diagnosis of gastric [46], liver [47], colorectal [48], lung [49], prostate [50, 51], breast [20, 21, 52], ovarian cancer [27, 53, 54]. The literature data suggest that VEGF can be serum tumor marker in general regardless of its location, but additional analyzes are needed due to the ambiguity of results. Moreover, looking at the available results, attention should be paid to the insufficient sensitivity of this parameter and thus, the necessity to use a panel with the specific commonly known tumor marker. In present study the combination of VEGF with CA 125 or SCC-Ag significantly improved the diagnostic sensitivity.

Hematopoietic cytokines participate in hematopoiesis regulation, but they also appear to play a crucial role in the development of cancers e.g. increased levels of M-CSF in ovarian [53, 55], endometrial [56], breast [52, 57–59] and cervical cancer or cervical intraepithelial neoplasia patients [60]. In this study, M-CSF plasma concentrations were significantly higher compared to control in case of both squamous cervical cancer adenocarcinoma group. In case of diagnostic criteria of cancer, M-CSF demonstrated comparable SE and SP in two studied histological types of cervical cancer.

Porika et al. found that serum SCC-Ag levels in squamous cell carcinoma and CA 125 levels in adenocarcinoma patients were correlated with clinical stage and lymph node metastasis, but no association was observed between the marker levels, tumor size and patient age, concluding that SCC-Ag and CA 125 are relatively specific for the squamous cell carcinoma of cervix and the adenocarcinoma of cervix, respectively [61]. However, in our study, we demonstrated no variations in CA 125 concentrations between adenocarcinoma patients, dysplasia patients and controls, which can be explained by small study group size. It is worth noting that there is limited data evaluating the clinical applicability of serum preoperative CA 125 concentration measurement in patients with cervical adenocarcinoma. Duk et al. found that CA 125 plasma level elevations are correlated with advanced FIGO stage, disease progression, and survival [62] which was confirmed by Bender et al. [63] and Kotowicz et al. [64].

In this work plasma concentrations of SCC-Ag were significantly higher in the cervical cancer group compared to the healthy controls. Our data is in agreement with the results of other researchers regarding the diagnostic usefulness of antigen SCC in this malignancy [65, 66]. Moreover, its prognostic significance, both for the recurrence-free and overall survival, has been confirmed by other researchers in the early stages of cervical cancer [67, 68]. Considering squamous cell cervical cancer group, the highest SE and SP was obtained for both SCC-Ag and CA 125 simultaneously and M-CSF, respectively. Suzuki et al. demonstrated that preoperative serum measurement of M-CSF combined with SCC-Ag can be selective diagnostic marker for squamous cell carcinoma arising in mature cystic teratoma of the ovary [69]. However, in our study, the greatest AUC for this type of cancer was obtained for VEGF, which is in agreement with study performed by Lebrecht et al. [70]. Analysis showed that VEGF in conjunction with SCC-Ag and CA 125 demonstrated the highest SE when assessed together. Nevertheless, some studies state that the most useful serum marker for squamous cell cervical cancer diagnosis is still SCC-Ag [71, 72]. However, our research clearly indicated that M-CSF demonstrated higher diagnostic power in squamous cell carcinoma group compared to the commonly used tumor markers- SCC-Ag and CA 125.

The accuracy of Pap smear in diagnosing cervical precancerous lesions remain low. Sensitivity and specificity of Pap smear in diagnosing cervical dysplasia vary from 34.3 to 93.8% and from 34.7 to 96.5%, respectively [73–77]. Cytology is subjective with poorly reproducible criteria and a trade-off between sensitivity and specificity should be emphasized. A high misdiagnosis percentage of uterine cervical cancer patients results from the high rate of false negative cervical cytology results [78, 79]. Due to this risk of error, there is clearly a need to search for new techniques and markers, which sensitivity will be higher in comparison to the methods currently used. The purpose of the new markers is primarily to reduce the percentage of undiagnosed patients, which will also improve their survival rate. Cytological screening proves successful for squamous lesions [2, 80] however this method is not effective in diagnostics of cervical adenocarcinoma yet [40]. Moreover, the cervical adenocarcinoma seems to be aggressive, and more often, lymph nodes metastases are observed in these patients [1]. A number of studies concerning cervical adenocarcinoma have addressed the use of tumor markers for pretreatment evaluation of this disease. Among all the assessed parameters, VEGF was the only marker that demonstrated sufficient diagnostic sensitivity in cervical adenocarcinoma patients. Serum measurement of VEGF in conjunction with CA 125 and SCC-Ag demonstrated a high diagnostic power based on AUC. VEGF plays a crucial role in neoangiogenesis, thus influencing disease progression and metastasis, including cervical cancer patients [14, 16, 81].

The ROC curve, which is the SE/SP diagram still remains important criterion for tumor markers [38]. The larger AUC corresponds to a better tumor marker. In this study, the ROC area of VEGF was the largest from all the tested parameters in both histological groups. Additionally, we observed statistically significantly larger AUCs for the studied markers compared to AUC = 0.5 in squamous cell cervical cancer and for VEGF, CA 125 and SCC-Ag, but not for M-CSF in adenocarcinoma group. Combined analysis showed that panel consisting of VEGF, CA 125, and SCC-Ag demonstrated the highest diagnostic power in both squamous cell carcinoma and adenocarcinoma groups.

Conclusions

Early detection of cervical cancer in patients is of utter importance. All the studied parameters fail in basic cervical cancer screening when considered separately. In our research the greatest diagnostic value is demonstrated when combined diagnostic panel of tumor markers is used. However, what should be emphasized is that the exploratory analysis need to be confirmed in separate future follow-up studies.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

None.

Availability of data and materials

The data will be available from the authors upon reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- CA 125

Cancer Antigen 125

- CIN

Cervical Intraepithelial Neoplasia

- CMIA

Chemiluminescent Microparticle Immunoassay

- CT

Computed Tomography

- CV%

Coefficient of Variation

- ELISA

Enzyme-Linked Immunosorbent Assay

- FIGO

International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics

- HPV

Human Papilloma Virus

- M-CSF

Macrophage-Colony Stimulating Factor

- M-CSFR

Macrophage-Colony Stimulating Factor Receptor

- ROC

Receiver Operator Characteristic

- SCC-Ag

Squamous Cell Carcinoma Antigen

- TAMs

Tumor Associated Macrophages

- VEGF

Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor

Authors’ contributions

IS, MZ-K and SL contributed to study design; MZ and EL contributed to the acquisition of data; IS, MZ, EL performed statistical analysis and edited the manuscript, IS, MZ-K, KZ and SL drafted the manuscript, EG collected the samples, MS contributed to interpretation of the results and provided critical input into all redrafts of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

All procedures performed in the studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standard of the ethical committee at Medical University of Bialystok (R-I-002/239/2014) and written informed consent was obtained from each patient for research purposes.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Iwona Sidorkiewicz, Email: iwona.sidorkiewicz@umb.edu.pl.

Monika Zbucka-Krętowska, Email: monikazbucka@wp.pl.

Kamil Zaręba, Email: kamilyo@gmail.com.

Emilia Lubowicka, Email: emila_lubowicka@wp.pl.

Monika Zajkowska, Email: monika@zajkowska.com.

Maciej Szmitkowski, Email: msz@umb.edu.pl.

Ewa Gacuta, Email: sunnyeve@wp.pl.

Sławomir Ławicki, Email: slawicki@umb.edu.pl.

References

- 1.Small W, Bacon MA, Bajaj A, Chuang LT, Fisher BJ, Harkenrider MM, et al. Cervical cancer: a global health crisis. Cancer. 2017;123(13):2404–2412. doi: 10.1002/cncr.30667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hillemanns P, Soergel P, Hertel H, Jentschke M. Epidemiology and early detection of cervical Cancer. Oncol Res Treat. 2016;39(9):501–506. doi: 10.1159/000448385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Carter SM, Williams J, Parker L, Pickles K, Jacklyn G, Rychetnik L, et al. Screening for cervical, prostate, and breast Cancer: interpreting the evidence. Am J Prev Med. 2015;49(2):274–285. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2015.01.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Aminisani N, Armstrong BK, Egger S, Canfell K. Impact of organised cervical screening on cervical cancer incidence and mortality in migrant women in Australia. BMC Cancer. 2012;12:491. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-12-491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kim JH, Kim IW, Kim YW, Park DC, Lee KH, Ahn TG, et al. Comparison of single-, double- and triple-combined testing, including pap test, HPV DNA test and cervicography, as screening methods for the detection of uterine cervical cancer. Oncol Rep. 2013;29(4):1645–1651. doi: 10.3892/or.2013.2257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Herbert A. Primary HPV testing: a proposal for co-testing in initial rounds of screening to optimise sensitivity of cervical cancer screening. Cytopathology. 2017;28(1):9–15. doi: 10.1111/cyt.12334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.C Kitchener H, Canfell K, Gilham C, Sargent A, Roberts C, Desai M, et al. The clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of primary human papillomavirus cervical screening in England: extended follow-up of the ARTISTIC randomised trial cohort through three screening rounds. Health Technol Assess 2014;18(23):1–196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 8.Zorzi M, Del Mistro A, Farruggio A, de'Bartolomeis L, Frayle-Salamanca H, Baboci L, et al. Use of a high-risk human papillomavirus DNA test as the primary test in a cervical cancer screening programme: a population-based cohort study. BJOG. 2013;120(10):1260–1267. doi: 10.1111/1471-0528.12272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dasari S, Wudayagiri R, Valluru L. Cervical cancer: biomarkers for diagnosis and treatment. Clin Chim Acta. 2015;445:7–11. doi: 10.1016/j.cca.2015.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mouková L, Nenutil R, Fabian P, Chovanec J. Prognostic factors for cervical cancer. Klin Onkol. 2013;26(2):83–90. doi: 10.14735/amko201383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Perkins GL, Slater ED, Sanders GK, Prichard JG. Serum tumor markers. Am Fam Physician. 2003;68(6):1075–1082. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.McGraw SL, Ferrante JM. Update on prevention and screening of cervical cancer. World J Clin Oncol. 2014;5(4):744–752. doi: 10.5306/wjco.v5.i4.744. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Valenti G, Vitale SG, Tropea A, Biondi A, Laganà AS. Tumor markers of uterine cervical cancer: a new scenario to guide surgical practice? Updat Surg. 2017. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 14.Albini A, Bertolini F, Bassani B, Bruno A, Gallo C, Caraffi SG, et al. Biomarkers of cancer angioprevention for clinical studies. Ecancermedicalscience. 2015;9:600. doi: 10.3332/ecancer.2015.600. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Semeran K, Pawłowski P, Lisowski Ł, Szczepaniak I, Wójtowicz J, Ławicki S, et al. Plasma levels of IL-17, VEGF, and adrenomedullin and S-cone dysfunction of the retina in children and adolescents without signs of retinopathy and with varied duration of diabetes. Mediat Inflamm. 2013;2013:274726. doi: 10.1155/2013/274726. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ferrara N, Gerber HP, LeCouter J. The biology of VEGF and its receptors. Nat Med. 2003;9(6):669–676. doi: 10.1038/nm0603-669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Maj E, Papiernik D, Wietrzyk J. Antiangiogenic cancer treatment: the great discovery and greater complexity (review) Int J Oncol. 2016;49(5):1773–1784. doi: 10.3892/ijo.2016.3709. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Abdalla DR, Simoens C, Bogers JP, Murta EF, Michelin MA. Angiogenesis markers in gynecological tumors and patents for anti-Angiogenic approach: review. Recent Pat Anticancer Drug Discov. 2015;10(3):298–307. doi: 10.2174/1574892810999150827153642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pérez D, Rohde A, Callejón G, Pérez-Ruiz E, Rodrigo I, Rivas-Ruiz F, et al. Correlation between serum levels of vascular endothelial growth factor-C and sentinel lymph node status in early breast cancer. Tumour Biol. 2015;36(12):9285–9293. doi: 10.1007/s13277-015-3663-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zhang SJ, Hu Y, Qian HL, Jiao SC, Liu ZF, Tao HT, et al. Expression and significance of ER, PR, VEGF, CA15-3, CA125 and CEA in judging the prognosis of breast cancer. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2013;14(6):3937–3940. doi: 10.7314/apjcp.2013.14.6.3937. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zhang J, Yin L, Wu J, Zhang Y, Xu T, Ma R, et al. Detection of serum VEGF and MMP-9 levels by Luminex multiplexed assays in patients with breast infiltrative ductal carcinoma. Exp Ther Med. 2014;8(1):175–180. doi: 10.3892/etm.2014.1685. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dobrzycka B, Terlikowski SJ, Kowalczuk O, Kulikowski M, Niklinski J. Serum levels of VEGF and VEGF-C in patients with endometrial cancer. Eur Cytokine Netw. 2011;22(1):45–51. doi: 10.1684/ecn.2011.0276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cuppens T, Tuyaerts S, Amant F. Potential therapeutic targets in uterine sarcomas. Sarcoma. 2015;2015:243298. doi: 10.1155/2015/243298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zbucka M, Koda M, Tomaszewski J, Przystupa W, Sulkowski S, Wołczyński S. Angiogenesis in the female reproductive processes. Ginekol Pol. 2004;75(8):649–657. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cheng D, Liang B, Li Y. Serum vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF-C) as a diagnostic and prognostic marker in patients with ovarian cancer. PLoS One. 2013;8(2):e55309. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0055309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Liang B, Guo Z, Li Y, Liu C. Elevated VEGF concentrations in ascites and serum predict adverse prognosis in ovarian cancer. Scand J Clin Lab Invest. 2013;73(4):309–314. doi: 10.3109/00365513.2013.773593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hui G, Meng M. Prognostic value of vascular endothelial growth factor expression in women with ovarian cancer: a meta-analysis. J BUON. 2015;20(3):870–878. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Guan X. Cancer metastases: challenges and opportunities. Acta Pharm Sin B. 2015;5(5):402–418. doi: 10.1016/j.apsb.2015.07.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Laoui D, Van Overmeire E, De Baetselier P, Van Ginderachter JA, Raes G. Functional Relationship between Tumor-Associated Macrophages and Macrophage Colony-Stimulating Factor as Contributors to Cancer Progression. Front Immunol. 2014;5:489. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2014.00489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ries CH, Cannarile MA, Hoves S, Benz J, Wartha K, Runza V, et al. Targeting tumor-associated macrophages with anti-CSF-1R antibody reveals a strategy for cancer therapy. Cancer Cell. 2014;25(6):846–859. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2014.05.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Van Overmeire E, Stijlemans B, Heymann F, Keirsse J, Morias Y, Elkrim Y, et al. M-CSF and GM-CSF receptor signaling differentially regulate monocyte maturation and macrophage polarization in the tumor microenvironment. Cancer Res. 2016;76(1):35–42. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-15-0869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Oncology FCoG FIGO staging for carcinoma of the vulva, cervix, and corpus uteri. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2014;125(2):97–98. doi: 10.1016/j.ijgo.2014.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Darragh TM, Colgan TJ, Thomas Cox J, Heller DS, Henry MR, Luff RD, et al. The lower Anogenital squamous terminology standardization project for HPV-associated lesions: background and consensus recommendations from the College of American Pathologists and the American Society for Colposcopy and Cervical Pathology. Int J Gynecol Pathol. 2013;32(1):76–115. doi: 10.1097/PGP.0b013e31826916c7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lubowicka E, Zbucka-Kretowska M, Sidorkiewicz I, Zajkowska M, Gacuta E, Puchnarewicz A, et al. Diagnostic power of cytokine M-CSF, metalloproteinase 2 (MMP-2) and tissue Inhibitor-2 (TIMP-2) in cervical Cancer patients based on ROC analysis. Pathol Oncol Res. 2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 35.Zajkowska Monika, Zbucka-Krętowska Monika, Sidorkiewicz Iwona, Lubowicka Emilia, Gacuta Ewa, Szmitkowski Maciej, Chrostek Lech, Ławicki Sławomir. Plasma levels and diagnostic utility of macrophage-colony stimulating factor, matrix metalloproteinase-9 and tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinase-1 as tumor markers in cervical cancer patients. Tumor Biology. 2018;40(7):101042831879036. doi: 10.1177/1010428318790363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Douglas CE, Michael FA. On distribution-free multiple comparisons in the one-way analysis of variance. Communications in Statistics - Theory and Methods. 1991;20(1):127–139. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Nahm FS. Nonparametric statistical tests for the continuous data: the basic concept and the practical use. Korean J Anesthesiol. 2016;69(1):8–14. doi: 10.4097/kjae.2016.69.1.8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Šimundić AM. Measures of diagnostic accuracy: basic definitions. EJIFCC. 2009;19(4):203–211. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Aggarwal P, Kehoe S. Serum tumour markers in gynaecological cancers. Maturitas. 2010;67(1):46–53. doi: 10.1016/j.maturitas.2010.04.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Tabata T, Takeshima N, Tanaka N, Hirai Y, Hasumi K. Clinical value of tumor markers for early detection of recurrence in patients with cervical adenocarcinoma and adenosquamous carcinoma. Tumour Biol. 2000;21(6):375–380. doi: 10.1159/000030143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Guo S, Yang B, Liu H, Li Y, Li S, Ma L, et al. Serum expression level of squamous cell carcinoma antigen, highly sensitive C-reactive protein, and CA-125 as potential biomarkers for recurrence of cervical cancer. J Cancer Res Ther. 2017;13(4):689–692. doi: 10.4103/jcrt.JCRT_414_17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Zusterzeel PL, Span PN, Dijksterhuis MG, Thomas CM, Sweep FC, Massuger LF. Serum vascular endothelial growth factor: a prognostic factor in cervical cancer. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 2009;135(2):283–290. doi: 10.1007/s00432-008-0442-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Srivastava S, Gupta A, Agarwal GG, Natu SM, Uma S, Goel MM, et al. Correlation of serum vascular endothelial growth factor with clinicopathological parameters in cervical cancer. Biosci Trends. 2009;3(4):144–150. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Du K, Gong HY, Gong ZM. Influence of serum VEGF levels on therapeutic outcome and diagnosis/prognostic value in patients with cervical cancer. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2014;15(20):8793–8796. doi: 10.7314/apjcp.2014.15.20.8793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Katanyoo K, Chantarasri A, Chongtanakon M, Rongsriyam K, Tantivatana T. Pretreatment levels of serum vascular endothelial growth factor do not correlate with outcome in patients with locally advanced cervical cancer. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2011;12(3):699–702. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wang L, Chang Y, Xu J, Zhang Q. Predictive significance of serum level of vascular endothelial growth factor in gastric Cancer patients. Biomed Res Int. 2016;2016:8103019. doi: 10.1155/2016/8103019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Mukozu T, Nagai H, Matsui D, Kanekawa T, Sumino Y. Serum VEGF as a tumor marker in patients with HCV-related liver cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma. Anticancer Res. 2013;33(3):1013–1021. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Divella R, Daniele A, DE Luca R, Simone M, Naglieri E, Savino E, et al. Circulating levels of VEGF and CXCL1 are predictive of metastatic Organotropismin in patients with colorectal Cancer. Anticancer Res. 2017;37(9):4867–4871. doi: 10.21873/anticanres.11895. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Balla MM, Desai S, Purwar P, Kumar A, Bhandarkar P, Shejul YK, et al. Differential diagnosis of lung cancer, its metastasis and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease based on serum Vegf, Il-8 and MMP-9. Sci Rep. 2016;6:36065. doi: 10.1038/srep36065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Botelho F, Pina F, Lunet N. VEGF and prostatic cancer: a systematic review. Eur J Cancer Prev. 2010;19(5):385–392. doi: 10.1097/CEJ.0b013e32833b48e1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Sharif MR, Shaabani A, Mahmoudi H, Nikoueinejad H, Akbari H, Einollahi B. Association of the serum vascular endothelial growth factor levels with benign prostate hyperplasia and prostate malignancies. Nephrourol Mon. 2014;6(3):e14778. doi: 10.5812/numonthly.14778. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Zajkowska M, Głażewska EK, Będkowska GE, Chorąży P, Szmitkowski M, Ławicki S. Diagnostic power of vascular endothelial growth factor and macrophage Colony-stimulating factor in breast Cancer patients based on ROC analysis. Mediat Inflamm. 2016;2016:5962946. doi: 10.1155/2016/5962946. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Będkowska GE, Ławicki S, Gacuta E, Pawłowski P, Szmitkowski M. M-CSF in a new biomarker panel with HE4 and CA 125 in the diagnostics of epithelial ovarian cancer patients. J Ovarian Res. 2015;8:27. doi: 10.1186/s13048-015-0153-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.González-Palomares B, Coronado Martín PJ, Maestro de Las Casas ML, Veganzones de Castro S, Rafael Fernández S, Vidaurreta Lázaro M, et al. Vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) polymorphisms and serum VEGF levels in women with epithelial ovarian Cancer, benign tumors, and healthy ovaries. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2017;27(6):1088–1095. doi: 10.1097/IGC.0000000000001006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Skates SJ, Horick N, Yu Y, Xu FJ, Berchuck A, Havrilesky LJ, et al. Preoperative sensitivity and specificity for early-stage ovarian cancer when combining cancer antigen CA-125II, CA 15-3, CA 72-4, and macrophage colony-stimulating factor using mixtures of multivariate normal distributions. J Clin Oncol. 2004;22(20):4059–4066. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2004.03.091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Ławicki S, Bedkowska GE, Gacuta-Szumarska E, Czygier M, Szmitkowski M. The plasma levels and diagnostic utility of stem cell factor in patients with endometrial cancer and myoma uteri. Pol Merkur Lekarski. 2009;26(156):609–615. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Ławicki S, Zajkowska M, Głażewska EK, Będkowska GE, Szmitkowski M. Plasma levels and diagnostic utility of M-CSF, MMP-2 and its inhibitor TIMP-2 in the diagnostics of breast Cancer patients. Clin Lab. 2016;62(9):1661–1669. doi: 10.7754/Clin.Lab.2016.160118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Aharinejad S, Salama M, Paulus P, Zins K, Berger A, Singer CF. Elevated CSF1 serum concentration predicts poor overall survival in women with early breast cancer. Endocr Relat Cancer. 2013;20(6):777–783. doi: 10.1530/ERC-13-0198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Ławicki S, Będkowska GE, Wojtukiewicz M, Szmitkowski M. Hematopoietic cytokines as tumor markers in breast malignancies. A multivariate analysis with ROC curve in breast cancer patients. Adv Med Sci. 2013;58(2):207–215. doi: 10.2478/ams-2013-0023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Ławicki S, Będkowska GE, Gacuta-Szumarska E, Knapp P, Szmitkowski M. Pretreatment plasma levels and diagnostic utility of hematopoietic cytokines in cervical cancer or cervical intraepithelial neoplasia patients. Folia Histochem Cytobiol. 2012;50(2):213–219. doi: 10.5603/fhc.2012.0030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Porika M, Vemunoori AK, Tippani R, Mohammad A, Bollam SR, Abbagani S. Squamous cell carcinoma antigen and cancer antigen 125 in southern Indian cervical cancer patients. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2010;11(6):1745–1747. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Duk JM, De Bruijn HW, Groenier KH, Fleuren GJ, Aalders JG. Adenocarcinoma of the uterine cervix. Prognostic significance of pretreatment serum CA 125, squamous cell carcinoma antigen, and carcinoembryonic antigen levels in relation to clinical and histopathologic tumor characteristics. Cancer. 1990;65(8):1830–1837. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19900415)65:8<1830::aid-cncr2820650828>3.0.co;2-s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Bender DP, Sorosky JI, Buller RE, Sood AK. Serum CA 125 is an independent prognostic factor in cervical adenocarcinoma. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2003;189(1):113–117. doi: 10.1067/mob.2003.443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Kotowicz B, Kaminska J, Fuksiewicz M, Kowalska M, Jonska-Gmyrek J, Gawrychowski K, et al. Clinical significance of serum CA-125 and soluble tumor necrosis factor receptor type I in cervical adenocarcinoma patients. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2010;20(4):588–592. doi: 10.1111/IGC.0b013e3181d5c27a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.de Bruijn HW, Duk JM, van der Zee AG, Pras E, Willemse PH, Boonstra H, et al. The clinical value of squamous cell carcinoma antigen in cancer of the uterine cervix. Tumour Biol. 1998;19(6):505–516. doi: 10.1159/000030044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.van de Lande J, Davelaar EM, von Mensdorff-Pouilly S, Water TJ, Berkhof J, van Baal WM, et al. SCC-ag, lymph node metastases and sentinel node procedure in early stage squamous cell cervical cancer. Gynecol Oncol. 2009;112(1):119–125. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2008.09.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Salvatici M, Achilarre MT, Sandri MT, Boveri S, Vanna Z, Landoni F. Squamous cell carcinoma antigen (SCC-ag) during follow-up of cervical cancer patients: role in the early diagnosis of recurrence. Gynecol Oncol. 2016;142(1):115–119. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2016.04.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Kotowicz B, Fuksiewicz M, Jonska-Gmyrek J, Bidzinski M, Kowalska M. The assessment of the prognostic value of tumor markers and cytokines as SCCAg, CYFRA 21.1, IL-6, VEGF and sTNF receptors in patients with squamous cell cervical cancer, particularly with early stage of the disease. Tumour Biol. 2016;37(1):1271–1278. doi: 10.1007/s13277-015-3914-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Suzuki M, Tamura N, Kobayashi H, Ohwada M, Terao T, Sato I. Clinical significance of combined use of macrophage colony-stimulating factor and squamous cell carcinoma antigen as a selective diagnostic marker for squamous cell carcinoma arising in mature cystic teratoma of the ovary. Gynecol Oncol. 2000;77(3):405–409. doi: 10.1006/gyno.2000.5784. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Lebrecht A, Ludwig E, Huber A, Klein M, Schneeberger C, Tempfer C, et al. Serum vascular endothelial growth factor and serum leptin in patients with cervical cancer. Gynecol Oncol. 2002;85(1):32–35. doi: 10.1006/gyno.2001.6517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Takeda M, Sakuragi N, Okamoto K, Todo Y, Minobe S, Nomura E, et al. Preoperative serum SCC, CA125, and CA19-9 levels and lymph node status in squamous cell carcinoma of the uterine cervix. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2002;81(5):451–457. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0412.2002.810513.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Li J, Cheng H, Zhang P, Dong Z, Tong HL, Han JD, et al. Prognostic value of combined serum biomarkers in predicting outcomes in cervical cancer patients. Clin Chim Acta. 2013;424:292–297. doi: 10.1016/j.cca.2013.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Castle PE, Glass AG, Rush BB, Scott DR, Wentzensen N, Gage JC, et al. Clinical human papillomavirus detection forecasts cervical cancer risk in women over 18 years of follow-up. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30(25):3044–3050. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.38.8389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Nkwabong E, Laure Bessi Badjan I, Sando Z. Pap smear accuracy for the diagnosis of cervical precancerous lesions. Trop Dr 2018:49475518798532. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 75.Szarewski A, Ambroisine L, Cadman L, Austin J, Ho L, Terry G, et al. Comparison of predictors for high-grade cervical intraepithelial neoplasia in women with abnormal smears. Cancer Epidemiol Biomark Prev. 2008;17(11):3033–3042. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-08-0508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Sørbye SW, Arbyn M, Fismen S, Gutteberg TJ, Mortensen ES. Triage of women with low-grade cervical lesions--HPV mRNA testing versus repeat cytology. PLoS One. 2011;6(8):e24083. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0024083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Sørbye SW, Suhrke P, Revå BW, Berland J, Maurseth RJ, Al-Shibli K. Accuracy of cervical cytology: comparison of diagnoses of 100 pap smears read by four pathologists at three hospitals in Norway. BMC Clin Pathol. 2017;17:18. doi: 10.1186/s12907-017-0058-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Castillo M, Astudillo A, Clavero O, Velasco J, Ibáñez R, de Sanjosé S. Poor cervical Cancer screening attendance and false negatives. A call for organized screening. PLoS One. 2016;11(8):e0161403. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0161403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Castanon A, Ferryman S, Patnick J, Sasieni P. Review of cytology and histopathology as part of the NHS cervical screening Programme audit of invasive cervical cancers. Cytopathology. 2012;23(1):13–22. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2303.2011.00948.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Jin L, Xu ZX. Recent advances in the study of HPV-associated carcinogenesis. Virol Sin. 2015;30(2):101–106. doi: 10.1007/s12250-015-3586-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Siveen KS, Prabhu K, Krishnankutty R, Kuttikrishnan S, Tsakou M, Alali FQ, et al. Vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) signaling in tumour vascularization: potential and challenges. Curr Vasc Pharmacol. 2017. [DOI] [PubMed]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The data will be available from the authors upon reasonable request.