Abstract

Introduction

Before their clinical rotations, medical students have limited exposure to women's health issues, particularly abortion.

Methods

We piloted a problem-based learning (PBL) module to introduce second-year medical students at the University of Louisville School of Medicine to counseling patients about pregnancy options. Students were divided into groups of 10 and met for two 2-hour sessions. In the first session, learners were presented with a case about a woman diagnosed with Zika virus who was considering pregnancy termination. Students discussed the case and developed learning objectives to research. One week later, students reconvened and shared what they had learned individually. Students were asked to complete pre- and post-PBL surveys. PBL facilitators also completed a survey evaluating the module.

Results

Fifty-eight percent of students felt informed or very informed about abortion after the PBL, compared to 30% before (p < .001). Students' mean quiz score increased from 29% on the pretest to 40% on the posttest (p < .001). Ninety-three percent of facilitators believed this PBL provided students with tools to better counsel about abortion, but only 56% of faculty felt adequately trained to facilitate this discussion.

Discussion

Students appreciated this PBL as an opportunity to discuss pregnancy options counseling and to clarify their own values surrounding abortion provision. Despite their positive response to the module, students identified barriers that would prevent them from implementing knowledge learned from this module in practice.

Keywords: Counseling, Abortion, Professionalism, Pregnancy, Pregnancy Complications, Problem-Based Learning, Medical Ethics, Preclinical Medical Education

Educational Objectives

By the end of this module, learners will be able to:

-

1.

Evaluate the physician's responsibility in counseling a patient about pregnancy options, including abortion, and provide this counseling.

-

2.

Recognize the types of laws that affect abortion provision.

-

3.

List surgical and nonsurgical methods of pregnancy termination and describe any contraindications or potential complications related to these methods.

Introduction

A 2017 study estimated that one in four women in the United States will seek an abortion by the time they reach age 45.1 Given the prevalence of this procedure, ensuring physicians' knowledge of and capability to provide safe abortion is an important matter of public health and safety. As such, abortion education is considered a valuable component of medical education.

At the postgraduate level, residents receive training in abortion procedures only if they choose to practice in a specialty that directly provides abortion care.2,3 However, professional medical education organizations recognize the importance of abortion training for all medical students prior to selecting their intended specialties. The Association of Professors of Gynecology and Obstetrics (APGO), the organization that sets national standards for medical student education in obstetrics and gynecology, has guidelines stating that “regardless of personal views about abortion, students should be knowledgeable about its public health importance as well as techniques and complications.”4 APGO states that students should meet the following objectives:

-

•

Provide nondirective counseling to patients surrounding pregnancy, including unintended pregnancy.

-

•

List surgical and nonsurgical methods of pregnancy termination.

-

•

Identify potential complications of pregnancy termination.

-

•

Describe the public health impact of the legal status of abortion.4

While students are expected to master the educational objectives set forth by APGO by the end of their undergraduate medical education, individual medical schools determine when and how they wish to include abortion education in their curricula.5 Abortion is a unique topic within medical education in that it involves aspects of clinical care, basic science, public health, and, most certainly, ethics. The topic is commonly introduced to preclinical medical students in the form of a lecture.6 At many medical schools, abortion is only included in the curriculum as it relates to medical ethics.5,6 Abortion does provide a forum for important ethical discussions, but when it is included only within ethics courses, learners miss out on the essential clinical elements of abortion education, such as maternal and fetal indications, pharmacology, and patient counseling skills. Furthermore, teaching medical students about abortion solely within the framework of an ethics discussion severely limits students' understanding of abortion as a legitimate medical procedure beyond its ethical and political components.5

Studies have shown that medical students value the opportunity to learn about abortion and want to see this topic included in their curricula.7,8 In a survey of students at one U.S. medical school, the majority of medical students reported that they found abortion to be an appropriate topic within the preclinical curriculum and felt discussions about abortion and reproductive care were worthwhile.7 In another study of medical students' knowledge about abortion, many students indicated that they “would include some aspect of abortion care in their medical practice if given sufficient opportunity to learn about the procedure.”9 The challenge comes in deciding where the subject best fits within the medical school curriculum.

One potential method for introducing abortion education into the preclinical curriculum is in the form of problem-based learning (PBL). PBL is a small-group, discussion-based learning method that has been introduced into health care curricula worldwide. PBL, as well as other methods of active learning such as case-based learning and team-based learning, is believed to increase learner satisfaction, which positively contributes to improved academic performance and sense of well-being.10 Furthermore, PBL is believed to be an effective method for teaching ethical decision-making skills to medical students and has been found to be superior to traditional instructional methods in the areas of teamwork skills, appreciation of social and emotional aspects of health care, appreciation of legal and ethical aspects of health care, and ability to cope with uncertainty.11 Previous publications about PBL as an instructional method for controversial issues within medical education, such as disorders of sexual development, have proven that PBL serves as a natural home for these issues within the preclinical medical school curriculum.12 Thus, it seems that PBL would provide an ideal forum for introducing preclinical medical students to abortion. This PBL module was piloted at the University of Louisville School of Medicine in the spring of 2017 with second-year medical students.

Methods

Students completed this case in two 2-hour sessions. We split students into groups of about 10 learners and one facilitator. Groups were the same for both the first and second sessions. In the first session, we presented students with a case about a pregnant woman diagnosed with Zika virus who was seeking pregnancy termination (Appendix A). During the session, students discussed the case in depth and identified questions and areas where they would like more information or background knowledge. By the end of the first 2-hour session, each group had created a list of learning objectives to research. One week later, the students reconvened for the second session, where we asked them to share what they had learned individually and discuss how this new knowledge pertained to the case. We gave learners access to the case (hard copy or electronic) as well as a whiteboard to organize questions and learning objectives and take notes on the case.

This PBL case can be modified for institutions at which PBL takes place in one session. In this format, students are given the case before the PBL session and come prepared with their own educational objectives and preliminary research. In the session, students discuss and teach one another about findings from their independent research.

In either the 1- or 2-week PBL formats, facilitators should be present to assist and offer clarification. At our institution, facilitators for this case were either clinical or nonclinical faculty members, residents, or fourth-year medical students. They had been previously trained about the goals and logistics of PBL modules and made aware of the case ahead of time. They had access to the facilitators' guide (Appendix B) to ensure that students addressed the case in a thorough manner and to clarify any discrepancies as they arose. One week before the first PBL session, we sent facilitators an email introducing them to the case and sharing resources with which to familiarize themselves with the subject matter. After the first PBL session, facilitators forwarded the learning objectives developed by their group to the study team via email. No data linked individual students to the learning objectives submitted by facilitators. After the second PBL session, facilitators completed a survey on their comfort facilitating this discussion and their suggestions for improving this PBL (Appendix C).

We assessed changes in students' knowledge and attitudes using pre- and posttests that we designed. These pre- and postquizzes had not been previously administered or validated. At the start of the first session, we asked students to complete a pretest that collected baseline data on knowledge of abortion procedures and laws, as well as on their attitudes toward and level of comfort with this topic. The pretest included 15 multiple-choice knowledge questions and six questions about students' attitudes and self-assessed competency regarding abortion (Appendix D). After the second session, we asked students to complete the same questions as on the pretest, as well as 11 additional questions offering feedback about the PBL module (Appendix E). Each group submitted its own learning objectives to the study team for thematic analysis. Facilitators graded students on their participation in discussion during both sessions. The study was deemed exempt by the Institutional Review Board at the University of Louisville School of Medicine.

Results

The second-year medical school class completed this PBL in the spring of 2017. A total of 113 second-year medical students completed both pre- and post-PBL surveys, for a 75% response rate. Students' average composite score on the knowledge-based questions significantly increased from answering an average of 29% of questions correctly on the pre-PBL survey to 40% of questions correctly on the post-PBL survey (p < .001). These results are consistent with students' own self-reported increased knowledge after the intervention. Fifty-eight percent of students described themselves as informed or very informed about abortion after the module, versus only 30% before the PBL (p < .001).

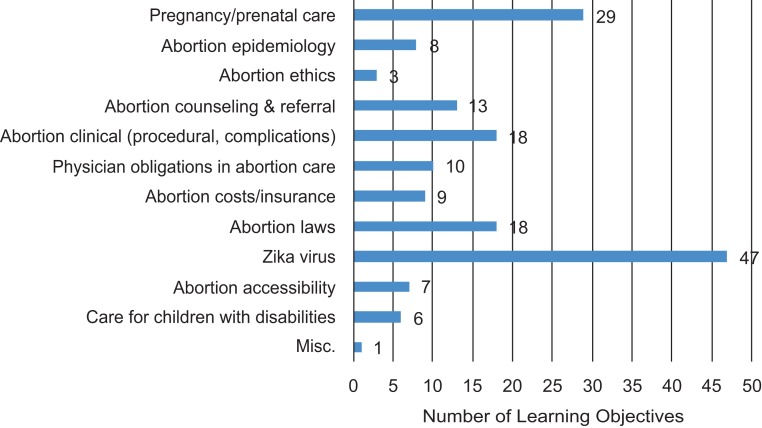

Themes that students chose to explore for their learning objectives were evaluated (see the Figure). The number of learning objectives pertaining to abortion varied between groups. Roughly half of each group's learning objectives were related to abortion (49%).

Figure. Frequency of learning objective themes. Bars reflect the number of times a given theme was addressed in the groups' submitted learning objectives.

Despite their positive response to the module, 17% of students indicated that there were barriers that would prevent them from implementing the knowledge obtained from this module in practice. Political and legal issues surrounding abortion were the most commonly cited barriers. We received thoughtful responses to the open-ended questions exploring how students would navigate their decisions about abortion care. These responses suggest that this PBL was effective in prompting students to consider their own opinions and values surrounding abortion. Four main themes emerged: (1) professional obligation, (2) patient autonomy, (3) moral and ethical considerations, and (4) sociopolitical climate surrounding abortion.

-

•Professional obligation: Students felt it was their duty as physicians to provide patients with counseling and resources to obtain an abortion, regardless of their personal beliefs. Many students cited the legal status of abortion, stating that as long abortion was legal, they considered it their job to provide patients with information regarding the procedure.

-

○“It is not my job to decide what is right or wrong. It is my job to provide care as long as the care is legal.”

-

○

-

•Patient autonomy: Students valued the idea of informed consent and of ensuring patients had enough information to make sound decisions. Respondents felt it was their responsibility to remain neutral, to avoid pushing patients toward a particular choice.

-

○“It is the mother's right to know all of the medical options available to her and it is my duty as a physician to inform her of those options.”

-

○

-

•Moral and ethical considerations: Those students who would and those students who would not participate in abortion care cited moral and ethical reasons for their decisions. Some students mentioned their support for abortion rights as the reason they felt morally compelled to participate in abortion care. Other students mentioned their faith and beliefs about the origins of life as reasons they would not participate in abortion provision.

-

○“My religion and faith are the most important thing in my life. That will never be overshadowed by medical practice. No matter the circumstances I find it hard to justify abortion.”

-

○

-

•Sociopolitical climate surrounding abortion: Respondents frequently cited the controversial nature of abortion provision, mentioning the legality of the procedure and even citing specific laws. Students also described their own feelings about the stigmatization of abortion providers and the danger they perceived in providing abortion care.

-

○“I don't feel comfortable being seen as the doctor who does abortions because I honestly don't think it's 100% safe in terms of the doctor's personal safety. Right now there's a lot of tension in terms of politics.”

-

○

Overall, students felt this PBL was helpful in increasing their knowledge about abortion and reported having a positive experience, regardless of their personal opinions about abortion or interest in future abortion provision. They overwhelmingly indicated that abortion should be part of the medical school curriculum and that this PBL would benefit their future medical practice (see the Table).

Table. Student Evaluation of This PBL Module and Abortion Educationa.

| Statement | Strongly Disagree/Disagree | Neutral | Agree/Strongly Agree | M (SD) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. | % | No. | % | No. | % | ||

| I know more about abortion care than before I completed this PBL. | 3 | 3% | 12 | 11% | 98 | 87% | 4.21 (0.74) |

| Abortion education should be included in my preclinical medical curriculum. | 6 | 5% | 16 | 14% | 91 | 81% | 4.16 (0.92) |

| This PBL was useful to my medical education. | 3 | 3% | 15 | 13% | 95 | 84% | 4.12 (0.73) |

| This PBL will benefit my future medical practice. | 6 | 5% | 19 | 17% | 88 | 78% | 3.97 (0.83) |

| I believe this PBL provided me with tools to better counsel a patient seeking abortion. | 7 | 6% | 25 | 22% | 81 | 72% | 3.90 (0.88) |

| This PBL will help me consider approaching patients seeking abortion differently. | 8 | 7% | 20 | 18% | 85 | 75% | 3.81 (0.85) |

Abbreviation: PBL, problem-based learning.

Rated on a 5-point Likert scale (1 = Strongly Disagree, 5 = Strongly Agree).

Sixteen facilitators completed post-PBL surveys, for a 100% response rate. Facilitators were both clinical and nonclinical faculty. Clinical faculty included physicians from various departments within the School of Medicine, including internal medicine, family medicine, and general surgery. Nonclinical faculty were from various basic science departments, including biochemistry and immunology. There were no obstetrician/gynecologists who fulfilled the role of facilitator for this module. Faculty response to the PBL was overwhelmingly positive. Ninety-three percent of respondents either agreed or strongly agreed that they believed this PBL provided students with tools to better counsel a patient seeking abortion. However, only 56% of faculty reported that they felt adequately prepared to facilitate this discussion. Because only 50% of faculty identified their department within the School of Medicine on the survey, we were unable to determine if a correlation existed between facilitators' area of training and their comfort with facilitating abortion-related content in this PBL. When asked for feedback about training faculty to facilitate this content in future sessions, the group was evenly divided into those who would like to see formal faculty development on teaching the content and those who thought references and links to resources would be sufficient.

Discussion

Overall, this PBL module appears to have achieved its primary objective of introducing medical students to clinical and ethical issues surrounding abortion care. In addition, comparing students' pre- and post-PBL quizzes and self-assessed competency scores demonstrated that this intervention increased students' knowledge. Students appreciated the PBL as an opportunity to discuss abortion and to evaluate the ethical and professional considerations surrounding abortion provision. It is evident from analysis of students' open-ended responses that the PBL prompted students to thoughtfully consider their own values and opinions about abortion provision, including issues of professional obligation, patient autonomy, and moral and ethical considerations surrounding abortion care. This intervention was effective in increasing awareness of the sociopolitical factors that affect patients seeking abortion, as well as physicians who provide such services.

We believe that the attrition in student response (75% response rate) was a result of the voluntary nature of students' participation in the evaluation of this module. While all students were required to attend the PBL as part of their regular instructional curriculum, they were given the option to forgo completion of the pre- and post-PBL surveys. In future iterations of this PBL that are not being studied for research purposes, student completion of pre- and post-PBL surveys can be made mandatory.

We propose two changes to future iterations of this PBL that we believe will improve its efficacy. First, we propose that this module be preceded by a didactic instructional component, either in person or online. The students who completed the module had previously been introduced to ethical topics surrounding abortion during their first 2 years of medical school, but they had not had any prior instruction about clinical abortion care or the epidemiology of abortion. We believe that adding a didactic component before the case would enhance students' PBL experience, allowing them to approach the case with a more solid understanding of how and why abortions are provided. Second, we plan to emphasize the importance of adequate training for facilitators, including adding optional training opportunities to clarify any questions or knowledge gaps facilitators have about abortion provision and pregnancy options counseling. Our post-PBL facilitator survey revealed that facilitators had varying degrees of comfort and expertise with the subject matter. Therefore, it is possible that some facilitators lacked the comfort and knowledge to appropriately direct student learning during the module.

In the future, we may also expand the scope of this learning experience by adding an existing validated standardized patient case, in which students can practice counseling patients about their pregnancy options, and/or a formal professionalism workshop, in which students can identify strategies for communicating with patients who make choices with which they disagree.13,14 There are many innovative modules that can be combined with this PBL to maximize the use of abortion education as a method for teaching preclinical medical students about professionalism and ethical issues affecting patient care.

We believe this case to be highly generalizable to medical students, as well as other health science students, in the United States and worldwide. Medical students not only must learn aspects of prenatal care and diagnosis before entering their clinical clerkships but also should learn to engage with ethically charged topics within the medical school curriculum in a professional manner. This module challenges students to articulate their thoughts about abortion and contemplate their approach to counseling pregnant patients. Developing these skills in a safe, low-stakes environment before students are tasked with having these conversations with patients during their clinical rotations is crucial. This session originally contained material relevant to Kentucky law, which has been removed for generalizability. Curriculum developers may consider altering the case to involve location-specific laws, practices, or challenges that pertain to abortion provision in their state or region.

This case was useful for helping students begin to explore their own values and opinions about abortion care and as a first step for teaching medical students how to interact with patients seeking advice about abortion. Based on the data and comments, students valued the opportunity to engage with classmates and explore their feelings about this topic, and the module was effective in teaching them the importance of nonjudgmental, nonbiased pregnancy options counseling. While the majority of medical students who completed this case will not go on to provide abortion care, many or all of them will treat reproductive-age female patients, and this PBL served to make them more sensitive to the concerns, feelings, and needs of patients who seek to terminate pregnancies.

Appendices

A. Case - Student Copy.docx

B. Case - Discussion Guide.docx

C. Evaluation - Faculty Survey.docx

D. Evaluation - Student Pretest.docx

E. Evaluation - Student Posttest.docx

All appendices are peer reviewed as integral parts of the Original Publication.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Amy Holthouser, associate dean for medical education, and the staff of the Office of Undergraduate Medical Education for their support implementing this module.

Disclosures

None to report.

Funding/Support

Dr. Bergin reports personal fees from Merck outside the submitted work.

Prior Presentations

Pomerantz T, Bergin A, Miller K, Ziegler C, Hoffman J, Patel P. Teaching abortion through problem-based learning: an evaluation of medical students' knowledge and experiences. Poster presented at: Research!Louisville; September 12, 2017; Louisville, KY.

Pomerantz T, Patel P, Miller K, Ziegler C, Hoffman J, Bergin A. Teaching abortion through problem-based learning: an evaluation of medical students' knowledge and experiences. Poster presented at: American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists Annual Meeting; April 29, 2018; Austin, TX.

Ethical Approval

The Institutional Review Board at the University of Louisville School of Medicine approved this study.

References

- 1.Jones RK, Jerman J. Population group abortion rates and lifetime incidence of abortion: United States, 2008–2014. Am J Public Health. 2017;107(12):1904–1909. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2017.304042 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Review Committee for Obstetrics and Gynecology. Clarification on requirements regarding family planning and contraception. http://www.acgme.org/portals/0/pfassets/programresources/220_obgyn_abortion_training_clarification.pdf Published 2017. Accessed June 24, 2018.

- 3.Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education. ACGME Program Requirements for Graduate Medical Education in Family Medicine. http://www.msm.edu/Education/GME/Documents/FamilyMedicine/ACGME_Requirements_120_family_medicine_2016.pdf Accessed June 24, 2018.

- 4.Educational Topic 34: pregnancy termination. In: Association of Professors of Gynecology and Obstetrics (APGO). APGO Medical Student Educational Objectives. 10th ed. Crofton, MD: Association of Professors of Gynecology and Obstetrics (APGO); 2013:37. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Steinauer J, LaRochelle F, Rowh M, Backus L, Sandahl Y, Foster A. First impressions: what are preclinical medical students in the US and Canada learning about sexual and reproductive health? Contraception. 2009;80(1):74–80. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.contraception.2008.12.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Espey E, Ogburn T, Chavez A, Qualls C, Leyba M. Abortion education in medical schools: a national survey. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2005;192(2):640–643. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajog.2004.09.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Espey E, Ogburn T, Leeman L, Nguyen T, Gill G. Abortion education in the medical curriculum: a survey of student attitudes. Contraception. 2008;77(3):205–208. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.contraception.2007.11.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Smith KG, Gilliam ML, Leboeuf M, Neustadt A, Stulberg D. Perceived benefits and barriers to family planning education among third year medical students. Med Educ Online. 2008;13(1):4474 https://doi.org/10.3402/meo.v13i.4474 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cessford TA, Norman W. Making a case for abortion curriculum reform: a knowledge-assessment survey of undergraduate medical students. J Obstet Gynaecol Can. 2011;33(1):38–45. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1701-2163(16)34771-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kilgour JM, Grundy L, Monrouxe LV. A rapid review of the factors affecting healthcare students’ satisfaction with small-group, active learning methods. Teach Learn Med. 2016;28(1):15–25. https://doi.org/10.1080/10401334.2015.1107484 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Koh GC-H, Khoo HE, Wong ML, Koh D. The effects of problem-based learning during medical school on physician competency: a systematic review. CMAJ. 2008;178(1);34–41. https://doi.org/10.1503/cmaj.070565 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Neff A, Kingery S. Complete androgen insensitivity syndrome: a problem-based learning case. MedEdPORTAL. 2016;12:10522 https://doi.org/10.15766/mep_2374-8265.10522 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lupi CS, Ward-Peterson M, Castro CA. Non-directive pregnancy options counseling: online instructional module, objective structured clinical exam, and rater and standardized patient training materials. MedEdPORTAL. 2017;13:10566 https://doi.org/10.15766/mep_2374-8265.10566 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Steinauer J, Sufrin C, Hawkins M, Koenemann K, Preskill F, Dehlendorf C. Caring for challenging patients workshop. MedEdPORTAL. 2014;10:9701 https://doi.org/10.15766/mep_2374-8265.9701 [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

A. Case - Student Copy.docx

B. Case - Discussion Guide.docx

C. Evaluation - Faculty Survey.docx

D. Evaluation - Student Pretest.docx

E. Evaluation - Student Posttest.docx

All appendices are peer reviewed as integral parts of the Original Publication.