Abstract

Background:

To assess reproducibility and accuracy of overall Nottingham grade and component scores using digital whole slide images (WSIs) compared to glass slides.

Methods:

Two hundred and eight pathologists were randomized to independently interpret 1 of 4 breast biopsy sets using either glass slides or digital WSI. Each set included 5 or 6 invasive carcinomas (22 total invasive cases). Participants interpreted the same biopsy set approximately 9 months later following a second randomization to WSI or glass slides. Nottingham grade, including component scores, was assessed on each interpretation, providing 2045 independent interpretations of grade. Overall grade and component scores were compared between pathologists (interobserver agreement) and for interpretations by the same pathologist (intraobserver agreement). Grade assessments were compared when the format (WSI vs. glass slides) changed or was the same for the two interpretations.

Results:

Nottingham grade intraobserver agreement was highest using glass slides for both interpretations (73%, 95% confidence interval [CI]: 68%, 78%) and slightly lower but not statistically different using digital WSI for both interpretations (68%, 95% CI: 61%, 75%; P= 0.22). The agreement was lowest when the format changed between interpretations (63%, 95% CI: 59%, 68%). Interobserver agreement was significantly higher (P < 0.001) using glass slides versus digital WSI (68%, 95% CI: 66%, 70% versus 60%, 95% CI: 57%, 62%, respectively). Nuclear pleomorphism scores had the lowest inter- and intra-observer agreement. Mitotic scores were higher on glass slides in inter- and intra-observer comparisons.

Conclusions:

Pathologists’ intraobserver agreement (reproducibility) is similar for Nottingham grade using glass slides or WSI. However, slightly lower agreement between pathologists suggests that verification of grade using digital WSI may be more challenging.

Keywords: Digital whole slide imaging, image analysis, interobserver agreement, interobserver variability, interrater, intraobserver agreement, intrarater, kappa, Nottingham grade, reproducibility

INTRODUCTION

Pathological assessment of biopsy specimens is more complex than simply differentiating benign from malignant histology and includes evaluation of prognostic factors. The Nottingham grading system was introduced in 1991[1] and is recommended as a standard prognostic factor reported for all breast cancer diagnoses.[2,3,4,5] Nottingham grade stratifies invasive breast carcinoma into low-, intermediate-, or high-grade categories by scoring three major histopathological features: proportion of tubule/gland formation, nuclear pleomorphism, and calibrated mitotic score.[6] Large international studies have validated the independent prognostic value of Nottingham grade in predicting disease-free survival and recurrence.[7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16] Nottingham grade is prognostically equivalent to lymph node classification and exceeds the prognostic value of other important factors such as tumor size,[11] patient age, menopausal status, and adjuvant treatment completion.[8,14] Nottingham grade is one of the three main pathologic determinants of treatment selection in clinical practice,[8] and its omission is thought to result in overuse of adjuvant treatment.[12] Nottingham grade has been incorporated into the Prognostic Stage Groups in the Eighth Edition of the AJCC Cancer Staging Manual.[17]

Concordance between pathologists assessing Nottingham grade is not ideal with published interobserver kappa coefficients ranging from 0.43 to 0.83.[18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26] Because second opinions are thought to improve clinical care and diagnostic accuracy, there is interest in expanding and expediting methods of consultative review,[27] including using digital whole slide images (WSIs). Digital WSI is used globally for archiving, teaching, teleconsultation, and increasingly for primary pathology diagnosis[28,29] with published studies supporting adoption of digital WSI citing nonsignificant reductions in overall diagnostic accuracy using digital WSI compared to traditional glass slides.[30,31,32] In 2017, the Food and Drug Administration approved the first digital WSI system for primary pathology diagnosis in the U.S.

As digital WSI rapidly disseminates into clinical practice, more comprehensive and nuanced studies comparing digital WSI to glass microscopy are required.[30,31,33] Our study addresses an important current knowledge gap by quantifying interobserver concordance and intraobserver reproducibility of Nottingham grade assessment using digital WSI compared to traditional glass slides.

METHODS

Study overview

Data collected during a large randomized study assessing accuracy and reproducibility of breast pathology diagnoses using glass microscopy and digital WSI were used for this analysis of Nottingham overall grade and component scores. The methods for the study, summarized below, have been described in detail.[32,34,35] The Institutional Review Boards of all participating organizations approved all study procedures; all participating pathologists signed an informed consent.

Study population: Pathologists

Pathologists were recruited from 8 U.S. states (AK, ME, MN, NH, NM, OR, VT, WA). All participants had experience interpreting breast specimens; fellows and residents were not eligible. The study involved a web-based survey capturing pathology experience and attitudes regarding digital WSI format.[36,37]

Biopsy case development: Traditional glass slides

Breast biopsy specimens (excisional and core) were identified from pathology registries in New Hampshire and Vermont.[38] New slides from candidate cases were prepared in a single laboratory for consistency. Three experienced breast pathologists established a consensus reference diagnosis for each case using a modified Delphi approach.[39] A single slide best representing the reference diagnosis was selected for each case. The cases included the full spectrum of breast pathology, from benign, to atypia, to ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS), to invasive carcinoma. Each case was digitized using an iScan Coreo Au® digital scanner as previously described.[32] The original study included a total of 240 cases, with 23 invasive carcinomas as defined by the consensus panel. One invasive case was excluded from the current analysis because it was a microinvasive carcinoma in a background of DCIS, and a standardized 10-field mitotic count could not be assessed. The analysis of grade presented here includes the remaining 22 cases defined as invasive carcinoma by the consensus reference panel.

Participant interpretations of biopsy cases

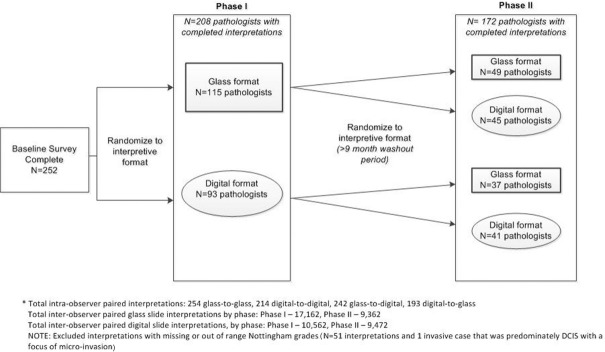

Figure 1 shows the overall study design and random assignment schema. In Phase I, pathologists were randomly assigned to independently interpret one of the four test sets in either glass or digital format. Pathologists were instructed to review the biopsy cases as they would in their routine clinical practice. Written instructions or training sets were not provided, and there was no intent to standardize diagnostic criteria. Phase I was followed by a washout period of at least 9 months. In Phase II, participants were randomly assigned either to the same diagnostic format they had used in Phase I or to the alternate format. The pathologists interpreted the same set of biopsy cases in Phase II; however, the order of presentation was different. Pathologists were not informed that they were interpreting the same cases in both phases.

Figure 1.

Study overview by phase and case format

An online diagnostic form was used to capture participants’ diagnoses on each case.[32,34,35,40] Pathologists selected a score of 1–3 for each component of Nottingham grade (tubule formation, nuclear pleomorphism, mitotic score) and selected an overall Nottingham grade of low, intermediate, or high. Nottingham grade is only assessed for cases the pathologists interpreted as invasive breast cancer. Although the data on grade were prospectively collected during the study, they have not been previously analyzed.

Statistical analysis

The Pearson Chi-squared test and the nonparametric Wilcoxon Rank-Sum test were used to compare pathologist characteristics and assignment to interpretive formats. Measures of agreement included the kappa statistic and proportional agreement. Intra- and Interobserver agreement were both assessed.

Associations between interpretative format (glass versus digital) and pathologists’ agreement (no versus yes) on Nottingham grade were tested in logistic regression analyses. To address correlated responses, the general estimating equations approach was used for estimating proportional agreement and 95% confidence intervals (CIs). Interaction terms using effect modifiers described in previously published work[34,37] were considered in the models. To test if the magnitude of the relationship between agreement and interpretative format was associated with a participant or case characteristic, a two-way interaction term was included along with each main effect. The effect modifiers included binary categories of breast pathology expert status (no versus yes), reported familiarity in use of digital format (no versus yes), and breast density on prior mammogram for the case (low vs. high).

Finally, for intraobserver analysis of reproducibility, we compared Phase I and Phase II responses for departures from agreement between row and column proportions. Departures from the main agreement line (diagonal) of the cross classifications of three-category Nottingham grade interpretations were tested for symmetry. To examine whether the same pathologist exhibited tendencies to classify interpretations higher or lower across identical or opposing interpretive formats, row marginal proportions and the corresponding column proportions were tested for statistical significance using a test for marginal homogeneity. The Bowker's test of symmetry was used to evaluate frequencies in discordant matched pairs and Bhapkar statistic for examining nominal differences in the distributions of marginal proportions in rows and columns of matched-pair cross-classification tables (as a test for marginal homogeneity).[41] All P values were two-sided, with statistical significance evaluated at the 0.05 alpha level. All analyses were performed using SAS software for Windows v9.4 (SAS, Inc., Cary, NC, USA).

RESULTS

Pathologists characteristics

As previously reported, 252 pathologists, 65% of those invited, were eligible and agreed to participate.[32,34,35] Table 1 shows characteristics and clinical experience of pathologists who completed Phase I (n = 208) and Phase II (n = 172) interpretations. A majority (93%) reported confidence interpreting breast pathology. Nearly half (48%) reported using the digital format in their professional work, mostly for conferences and education.

Table 1.

Participant characteristics by Phase I and II interpretive formata

| Participant Characteristics | Study phase | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Phase I | Phase II | |||

| Glass, n (%) | Digital, n (%) | Glass, n (%) | Digital, n (%) | |

| Total | 115 (55) | 93 (45) | 86 (50) | 86 (50) |

| Demographics | ||||

| Age at survey (years) | ||||

| 30-39 | 16 (14) | 12 (13) | 12 (14) | 11 (13) |

| 40-49 | 41 (36) | 29 (31) | 30 (35) | 26 (30) |

| 50-59 | 42 (37) | 32 (34) | 29 (34) | 35 (41) |

| 60+ | 16 (14) | 20 (22) | 15 (17) | 14 (16) |

| Sex | ||||

| Men | 69 (60) | 63 (68) | 54 (63) | 56 (65) |

| Women | 46 (40) | 30 (32) | 32 (37) | 30 (35) |

| Clinical practice and breast pathology expertise | ||||

| Fellowship training in breast pathology | ||||

| No | 109 (95) | 88 (95) | 82 (95) | 82 (95) |

| Yes | 6 (5) | 5 (5) | 4 (5) | 4 (5) |

| Affiliation with academic medical center | ||||

| No | 87 (76) | 66 (71) | 55 (64) | 67 (78) |

| Yes, adjunct/affiliated | 17 (15) | 18 (19) | 20 (23) | 12 (14) |

| Yes, primary appointment | 11 (10) | 9 (10) | 11 (13) | 7 (8) |

| Do your colleagues consider you an expert in breast pathology? | ||||

| No | 90 (78) | 74 (80) | 67 (78) | 69 (80) |

| Yes | 25 (22) | 19 (20) | 19 (22) | 17 (20) |

| Breast specimen case load (percentage of total clinical work) | ||||

| <10 | 59 (51) | 45 (48) | 44 (51) | 41 (48) |

| 10-24 | 45 (39) | 42 (45) | 35 (41) | 38 (44) |

| 25-49 | 8 (7) | 5 (5) | 5 (6) | 5 (6) |

| ≥50 | 3 (3) | 1 (1) | 2 (2) | 2 (2) |

| How confident are you interpreting breast pathology?b | ||||

| More confident (1, 2 or 3) | 107 (93) | 86 (92) | 81 (94) | 76 (88) |

| Less confident (4, 5, 6) | 8 (7) | 7 (8) | 5 (6) | 10 (12) |

| Do you have any experience using digitized whole slides in your professional work?c | ||||

| No | 63 (55) | 46 (49) | 38 (44) | 46 (53) |

| Yes | 52 (45) | 47 (51) | 48 (56) | 40 (47) |

aWithin each phase, P values for differences by format were nonsignificant for all characteristics listed. P values correspond to Pearson Chi-square test for difference in distributions of each pathologist characteristic between glass and digital formats within each study phase. A Wilcoxon Rank-Sum test was used for factors with ordered categories, bConfidence was reported on a 6-point Likert Scale from 1: “High confidence” to 6: “Not confident at all.” Responses were combined into a binary variable for analysis with 1, 2, and 3 confident and 4, 5, and 6 not confident, cPathologists were asked, “In what ways do you use digitized whole slides in your professional work?” Pathologists were deemed to have experience in digital pathology if they reported any answer other than “Not at all.” The full list of possible answers included: Primary pathology diagnosis; tumor board/clinical conference; consultative diagnosis; CME/Board exams/teaching in general; archival purposes; research; other (text box provided); not at all. CME: Continuing Medical Education

Pathologist reproducibility (intraobserver concordance)

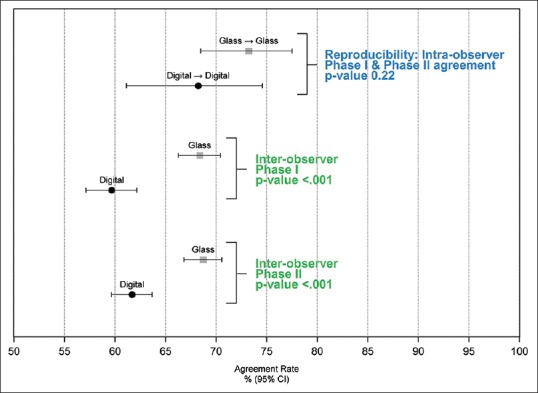

Histological grade reproducibility for the 172 pathologists interpreting the same cases in both Phases I and II is shown by format (glass vs. digital) in Table 2, including pathologists using glass slides (n = 49) or digital WSI (n = 41) in both phases. Higher Kappa coefficients and higher percentage agreement for the individual TNM scores and overall Nottingham grade were noted when glass slide format was used in both phases. Figure 2 (top portion) shows Nottingham grade reproducibility when interpretations were made by the same pathologist using glass slides in both phases (73% agreement, 95% CI 68,78) or digital WSI in both phases (68% agreement, 95% CI 61, 75; P = 0.22).

Table 2.

Intraobserver reproducibility of histological grading for invasive breast carcinoma by study pathologists who interpreted the same cases in Phase I and II, with data shown by phase and interpretive format (22 invasive cases)

| Intraobserver reproducibilitya | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Phase of study and format | Number of pathologists | Number of paired interpretations | κb (95% CIs) | Percentage agreementc,d (95% CIs) | ||||||||

| Phase I | Phase II | T | N | M | Nottingham grade | T | N | M | Nottingham grade | |||

| Same format | Glass slide format | Glass slide format | 49 | 254 | 0.73 (0.66-0.81) | 0.44 (0.34-0.54) | 0.52 (0.42-0.62) | 0.57 (0.48-0.66) | 84* (79-88) | 68 (62-73) | 79 (73-84) | 73 (68-78) |

| Digital format | Digital format | 41 | 214 | 0.48 (0.38-0.59) | 0.41 (0.30-0.53) | 0.37 (0.26-0.49) | 0.48 (0.37-0.58) | 72 (65-78) | 69 (62-75) | 72** (65-79) | 68 (61-75) | |

| Change in format | Glass slide format | Digital format | 45 | 242 | 0.50 (0.41-0.60) | 0.27 (0.16-0.38) | 0.37 (0.26-0.48) | 0.35 (0.25-0.46) | 72 (66-77) | 62* (55-69) | 74*,e (68-79) | 61 (55-67) |

| Digital format | Glass slide format | 37 | 193 | 0.50 (0.39-0.61) | 0.38 (0.26-0.50) | 0.44 (0.33-0.55) | 0.42 (0.30-0.53) | 73 (68-78) | 65 (58-72) | 77* (71-82) | 66 (59-73) | |

| Combinedf | 82 | 435 | 0.50 (0.43-0.57) | 0.32 (0.24-0.40) | 0.40 (0.32-0.48) | 0.38 (0.30-0.46) | 72 (68-76) | 63 (58-68) | 75 (71-79) | 63 (59-68) | ||

aThe exact same measurement was taken within each study phase with an intervening 9 months or more hiatus, bSimple κ coefficient, cGEE multivariable modeling, dContingency tables tested for homogeneity of marginal distribution (Bhapkar) and symmetry (Bowker), eFor the marginal homogeneity test only, fCombined represents both the glass to digital results in combination with the digital to glass results, *P<0.05, **P<0.01. CIs: Confidence intervals, T: Tubular score, N: Nuclear pleomorphism score, M: Mitotic score, GEE: General estimating equation

Figure 2.

Intraobserver and interobserver agreement of Nottingham grade score comparing interpretive format of glass slides to digital whole slide images. Data are based on independent interpretations of 22 invasive breast carcinoma cases

In general, the kappa coefficients for nuclear pleomorphism were lower than the kappa coefficients for tubule formation and mitotic score, particularly when the format changed between phases. The kappa statistic for overall Nottingham grade was highest when glass slides were used (κ = 0.57; 95% CI 0.48, 0.66); lower when digital WSI were used in both phases (κ = 0.48; 95% CI 0.37, 0.58); and lowest when the format changed between phases (κ = 0.38; 95% CI 0.30, 0.46). Similar trends were noted for the percent agreement with the lowest agreement noted for nuclear pleomorphism score, particularly when the interpretive format changed [Table 2].

Mitotic counts tended to be higher when interpretations were made using glass slides compared with digital WSI. For example, when the same cases were interpreted using digital WSI in Phase I followed by glass slides in Phase II, the mitotic score was statistically significantly higher using glass slides (test for marginal homogeneity, P = 0.013). A similar trend was noted when interpretations were performed using glass in Phase I followed by digital WSI in Phase II, with mitotic index classified lower using digital WSI (P = 0.034) [Supplemental Figure 1 (551.9KB, tif) ]

Multivariable modeling adjustments for matching at the case and participant level revealed a lower agreement for overall Nottingham grade when the interpretative format changed between phases compared with interpretation using glass slides in both phases (P = 0.004). No significant differences were noted between Nottingham grade reproducibility when the digital format was used in both phases compared with glass in both phases (P = 0.22).

Interobserver concordance between pathologists

Pathologists tended to be more likely to agree with their peers’ nuclear pleomorphism score, the mitotic score, and the Nottingham overall grade when the interpretations were made in glass slide format compared to when interpretations were made in the digital format [Table 3]. For example, the kappa statistic for the Phase I overall Nottingham grade interobserver concordance was significantly (P < 0.001) higher on glass slides (κ = 0.48) than on digital WSI format (κ = 0.32) [Table 3 and Figure 1]. In addition, both tubule score and mitotic score had higher interobserver concordance on glass slides (Tubule score κ = 0.51, Mitotic Score κ = 0.42) than digital WSI format (Tubule score κ = 0.40, Mitotic Score κ = 0.25). Interobserver concordance findings in Phase II were consistent with Phase I findings.

Table 3.

Interobserver concordance of histological grading for invasive breast carcinoma among different pathologists interpreting the same cases (interobserver concordance) by study phase and interpretive format (22 invasive cases)

| Interobserver concordancea | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Phase of study and format | Number of pathologists | Number of paired interpretations | κb (95% CIs) | Agreementc (95% CIs) | ||||||

| T | N | M | Nottingham grade | T | N | M | Nottingham grade | |||

| Phase I | ||||||||||

| Glass slide format | 115 | 17,162 | 0.51 (0.50-0.52) | 0.22 (0.21-0.24) | 0.42 (0.40-0.43) | 0.48 (0.47-0.49) | 71 (69-73) | 58 (56-59) | 74 (72-77) | 68 (66-70) |

| Digital format | 93 | 10,562 | 0.40 (0.39-0.42) | 0.22 (0.20-0.23) | 0.25 (0.23-0.27) | 0.32 (0.31-0.34) | 67 (65-70) | 58 (56-61) | 70 (67-73) | 60 (57-62) |

| Phase II | ||||||||||

| Glass slide format | 86 | 9362 | 0.47 (0.45-0.48) | 0.25 (0.23-0.27) | 0.45 (0.44-0.47) | 0.49 (0.48-0.51) | 71 (68-73) | 56 (54-59) | 76 (73-78) | 69 (67-71) |

| Digital format | 86 | 9472 | 0.37 (0.35-0.38) | 0.17 (0.15-0.19) | 0.23 (0.21-0.25) | 0.36 (0.34-0.37) | 65 (62-67) | 56 (53-58) | 68 (65-70) | 62 (60-64) |

aAll pairwise combinations excluding overlapping pathologists, bSimple κ coefficient, cGEE multivariable modeling. CIs: Confidence intervals, T: Tubular score, N: Nuclear pleomorphism grade, M: Mitotic score, GEE: General estimating equation

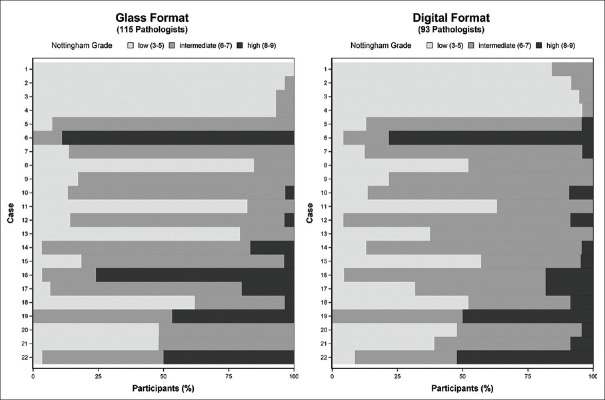

The variation in pathologists’ assessment of Nottingham grade was not restricted to just one or two difficult cases. Figure 3 shows the Nottingham grade score assignment for each of the 22 cases in Phase I, with results of interpretations in glass on the left panel and of interpretations in digital format on the right panel. Only one case (Case 1) had unanimous agreement in the Nottingham grade among the pathologists providing independent interpretations when all interpretations were made using glass slides. There were no cases with unanimous agreement in Nottingham grade using digital WSI format for the interpretations. Eight of the 22 cases interpreted by multiple pathologists using glass slides included overall Nottingham grade assessments ranging from low to high grade on the same case. When digital WSI was used, agreement among pathologists was lower, with 13 of 22 cases assigned assessments in all three Nottingham grade categories.

Figure 3.

Nottingham grade combined histological score as assessed by 208 pathologists independently interpreting 22 invasive breast carcinoma cases. Results are depicted by case and interpretive format (Phase I data only)

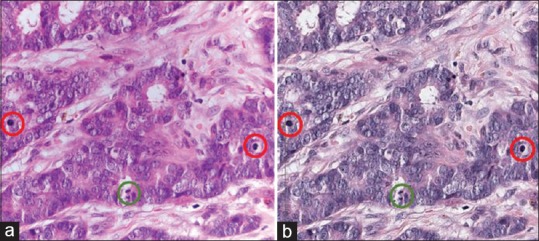

On review of these cases, two (Cases 15 and 16) were noted to have high variation in mitotic score between glass and digital format interpretations, and both cases had atypical mitotic figures. On review of all of the study cases, the digital image appeared more hyperchromatic than the glass slide, which made the samples appear more basophilic on digital WSI. In many cases, this did not seem to impact diagnosis or Nottingham grade and could be likened to interpreting a slide from another institution where the hematoxylin and eosin staining technique is different. However, for Cases 15 and 16, the atypical mitotic figures appeared similar to lymphocytes on the darker digital image background. Figure 4 shows images of Case 15 from the two interpretive formats. In addition, the loss of z-plane focus on digital format made it more difficult or impossible to verify some mitotic figures. Consequently, the majority of participants assigned a higher mitotic score when using glass slides (Mitotic Score 3; 64% vs. 14%, glass vs. WSI, respectively). This difference in mitotic score assignment was large enough to shift the overall Nottingham grade, with 74% of pathologists assigning intermediate grade for Case 15 on glass slides and 57% assigning low grade using digital WSI. Similar results were noted in Phase II for interpretations of this case.

Figure 4.

Example Case #15 illustrating the difference in mitotic figures between formats. The mitotic scores and overall Nottingham grade scores presented for this case are based on interpretations from 46 pathologists using glass sides and 37 pathologists using digital whole slide images (Case #15 in Figure 3). (a) Photomicrograph of glass slide. N = 46 total interpretations on glass for PI + PII. Percent of total interpretations. Mitotic Count Score: (1) 7%, (2) 30%, (3) 63%. Nottingham grade: L: 20%, I: 74%, H: 7%. (b) Screen capture of digital slide viewer. N = 37 total interpretations on digital for PI + PII. Percent of total interpretations. Mitotic Count Score: (1) 32%, (2) 54%, (3) 14%. Nottingham grade: L: 57%, I: 38%, H: 5%. Green circles: Clear mitotic figure in both formats. Red circles: Mitotic figures seen clearly on glass when using z-plane focus but appearing as lymphocytes on digital format. (Note that the photomicrograph does not fully capture the clarity of mitotic figures that was seen on microscopy using z-plane focus)

Interobserver concordance for Nottingham grade was lower when using digital WSI than when using glass slides, regardless of patient breast density noted on previous mammography or pathologists’ self-reported breast pathology expertise or digital experience [Supplemental Figure 2 (799.6KB, tif) ].

CONCLUSIONS

Digital pathology is expected to transform diagnostic and prognostic interpretation mandating careful evaluation of the effect on clinical practice, including important prognostic factors such as breast cancer Nottingham grade. Our current analysis of data collected from a large cohort of practicing pathologists demonstrates increased variability between pathologists in Nottingham grade assessments using digital WSI compared to glass slides. Diagnostic variability in Nottingham grade assessment using traditional glass slide microscopy is a known challenge;[18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26] thus, our study design examining pathologists’ reproducibility in two formats is germane (intraobserver agreement on Phase I vs. Phase II interpretations on the same case). Nottingham grade reproducibility was highest when glass was used in both phases, lower with digital WSI, and lowest when the format changed between phases. While this finding suggests grade may be less reproducible if assessed using digital images, we found no significant differences between Nottingham grade reproducibility when the digital format was used in both phases compared with glass in both phases (P = 0.22).

The overall Nottingham grade also had significantly lower interobserver concordance on digital WSI format than on traditional glass slides with a kappa statistic lower than any previously published kappa values for agreement of Nottingham grade on glass slide format.[18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26] The lower kappa for overall Nottingham grade on digital WSI is reflective of lower kappa coefficients in the three major histopathological features – tubule/gland formation, nuclear pleomorphism, and mitotic score – on digital format. This suggests that there may be more disagreement on grade if a second opinion is obtained using digital WSI to confirm a grade obtained by glass slide evaluation. These nuances in prognostic factor assessment may require additional research, including determining whether these observations persist as pathologists gain more experience using digital WSI for diagnosis and prognosis.

Nuclear pleomorphism scores were the most variable of the three components in both formats, with no clear bias toward higher or lower score by format. In addition, side-by-side examination of both formats for these cases showed no clear clinical explanations for nuclear pleomorphism variability. Interpreting pathologists used their own computer monitors, and it is unknown how monitor characteristics may have affected their assessments, an area which should be studied.

While both inter- and intra-observer agreement was higher for mitotic count score than nuclear pleomorphism score, there was a clearer bias in the variation of mitotic count score by format. Pathologists were more likely to assign a higher mitotic score when interpreting the same case in the glass slide format. In addition, the interobserver agreement for mitotic score was biased toward higher scores on glass slide format. This differs from previous published research which found no significant change in mitotic score between formats.[42] Unlike previous studies, we did not preselect and identify the area for mitotic score assessment, but instead let each pathologist choose the area on each slide as they would in clinical practice, likely lowering pathologists’ agreement. It may be that it is easier for pathologists to select the most mitotically active area (the starting point according to the grading rules for the 10-field count) on glass slides than on digital format since the digital image is larger and more cumbersome to navigate. In addition, based on review of cases with discordant mitotic scores between formats, we concluded atypical mitotic figures were less readily identifiable using the digital WSI, partly due to z-plane focus capability on a microscope. This variation was great enough to shift the overall grade assignment of the carcinoma for some observations.

The mitotic score component of grade can be challenging, and importantly, intratumoral mitotic rate heterogeneity coupled with variation in observer technique can alter the overall grade assessment. Reproducibility might be improved with more training in the digital format or with advances in digital viewing software, including the addition of z-plane focus. Some literature also suggests that interpretations using digitally scored immunostains, such as automated phosphohistone H3 (PHH3), may be more accurate and reproducible.[43] A standardized Ki-67 immunohistochemical assay approach could potentially replace or augment the mitotic score component of grading. In addition, challenges such as the Assessment of Mitosis Detection Algorithms 2013 have been launched with the goal of finding an automatic computer-aided mitosis detection method to improve interobserver concordance, and top-performing automated computer methods are comparable to concordance among pathologists.[44]

We acknowledge the limitations inherent in a one-slide-per-case study. Pathologists will often review multiple slides and access more clinical background information, request immunohistochemical stains, and obtain second opinions in clinical practice. However, these limitations applied equally to the digital and glass slide formats in this study. The representative slide for each case was carefully selected by an experienced pathologist, and all corresponding digital images were carefully examined by the study pathologist (DW) and a technician to ensure quality. We also acknowledge that most pathologists have limited experience with digital WSI in clinical practice.

While prior studies have reported variability among pathologists in Nottingham grade assessments,[18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26] this is the first study to evaluate both interpretive formats among a large cohort of pathologists representing a broad spectrum of clinical experience. With multiple participants interpreting the same case twice, our study uniquely evaluates intraobserver reproducibility in Nottingham grade within and between interpretive formats. Our randomized study design, with two phases of interpretation in both glass and digital formats, also allows for side-by-side comparisons, which has not been previously reported. The design methods developed and used in this study have application beyond breast cancer and may be important to a broader community in other tumor systems.

While digitized pathology slides offer multiple advantages, use of the WSI digital format may be associated with increased variability among pathologists in assigning the Nottingham grade for invasive breast carcinomas. Advances in digital technology resolution, development of digital image analysis aids, and training in digital WSI interpretation may help address current limitations in grade assessment and be important for provision of the highest quality of clinical care.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

The data in this manuscript were presented in part at the 106th annual meeting of the United States and Canadian Academy of Pathology, March 4-10, 2017, San Antonio, TX, USA. (Platform presentation, Abstract 2032).

Proportion of tubule/gland formation, nuclear pleomorphism, and mitotic scores assigned to 22 invasive breast carcinoma cases interpreted by same participant in Phase II, with data shown by phase and interpretive format

Interobserver agreement of Nottingham grade combined histological score for 22 invasive breast carcinoma cases by participant (a) or case characteristic (b) (Phase I, n = 17,162 paired interpretations on glass, n = 10,562 paired interpretations on digital). (a) N = 115 participants. (b) N = 22 cases

Acknowledgments

Authors DW, TO, PF, LS, and JE report grants from NIH/NCI, during the conduct of the study. Author JE also reports personal fees from UpToDate, outside of the submitted work. Supported by the National Cancer Institute (R01CA140560, R01CA172343, K05 CA104699, U01CA86082, U01CA70013), the NCI-funded Breast Cancer Surveillance Consortium (HHSN261201100031C), and the University of Washington Medical Student Research Training Program (MSRTP).

The collection of cancer and vital status data was supported in part by several state public health departments and cancer registries throughout the U.S. For a full description of these sources, please see: http://www.breastscreening.cancer.gov/work/acknowledgement.html.

The authors wish to thank Ventana Medical Systems, Inc., Tucson, AZ, USA, a member of the Roche Group, for use of iScan Coreo Au™ whole slide imaging system, and HD View SL for the source code used to build our digital viewer. For a full description of HD View SL please http://hdviewsl.codeplex.com/.

Footnotes

Available FREE in open access from: http://www.jpathinformatics.org/text.asp?2019/10/1/11/255394

REFERENCES

- 1.Elston CW, Ellis IO. Pathological prognostic factors in breast cancer. I. The value of histological grade in breast cancer: Experience from a large study with long-term follow-up. Histopathology. 1991;19:403–10. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2559.1991.tb00229.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Edge SB, Byrd DR, Compton CC, Fritz AG, Greene FL, Trotti A, editors. AJCC cancer staging manual. 7th ed. New York, NY: Springer; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lyon: IARC Press, International Agency for Research on Cancer; 2003. World Health Organization Classification of Tumours: Tumors of the Breast and Female Genital Organs; pp. 18–9. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sheffield: NHS Cancer ScreeningProgrammes and The Royal College of Pathologists; 2005. Pathology Reporting of Breast Disease: A Joint Document Incorporating the Third Edition of the NHS Breast Screening Programme's Guidelines for Pathology Reporting in Breast Cancer Screening and the Second Edition of The Royal College of Pathologists' Minimum Dataset for Breast Cancer Histopathology. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Aebi S, Davidson T, Gruber G, Cardoso F. ESMO Guidelines Working Group. Primary breast cancer: ESMO Clinical Practice Guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Ann Oncol. 2011;22(Suppl 6):vi12–24. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdr371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Assessment of Breast Cancer Grading Using the Nottingham Combined Histological Grading System: University of Nottingham and Nottingham University Hospitals NHS Trust. [Last accessed on 2017 Jan 12]. Available from: http://www.nottingham.ac.uk/~mrzarg/nott.htm .

- 7.Rakha EA, Reis-Filho JS, Baehner F, Dabbs DJ, Decker T, Eusebi V, et al. Breast cancer prognostic classification in the molecular era: The role of histological grade. Breast Cancer Res. 2010;12:207. doi: 10.1186/bcr2607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rakha EA, El-Sayed ME, Lee AH, Elston CW, Grainge MJ, Hodi Z, et al. Prognostic significance of nottingham histologic grade in invasive breast carcinoma. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:3153–8. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.15.5986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Walker R. 1st ed. New York: Informa Health Care; 2003. Prognostic and Predictive Factors in Breast Cancer. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pereira H, Pinder SE, Sibbering DM, Galea MH, Elston CW, Blamey RW, et al. Pathological prognostic factors in breast cancer. IV: Should you be a typer or a grader? A comparative study of two histological prognostic features in operable breast carcinoma. Histopathology. 1995;27:219–26. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2559.1995.tb00213.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Saimura M, Fukutomi T, Tsuda H, Sato H, Miyamoto K, Akashi-Tanaka S, et al. Prognosis of a series of 763 consecutive node-negative invasive breast cancer patients without adjuvant therapy: Analysis of clinicopathological prognostic factor. J Surg Oncol. 1999;71:101–5. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1096-9098(199906)71:2<101::aid-jso8>3.0.co;2-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lundin J, Lundin M, Holli K, Kataja V, Elomaa L, Pylkkänen L, et al. Omission of histologic grading from clinical decision making may result in overuse of adjuvant therapies in breast cancer: Results from a nationwide study. J Clin Oncol. 2001;19:28–36. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2001.19.1.28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Simpson JF, Gray R, Dressler LG, Cobau CD, Falkson CI, Gilchrist KW, et al. Prognostic value of histologic grade and proliferative activity in axillary node-positive breast cancer: Results from the Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group Companion Study, EST 4189. J Clin Oncol. 2000;18:2059–69. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2000.18.10.2059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Frkovic-Grazio S, Bracko M. Long term prognostic value of nottingham histological grade and its components in early (pT1N0M0) breast carcinoma. J Clin Pathol. 2002;55:88–92. doi: 10.1136/jcp.55.2.88. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Warwick J, Tabàr L, Vitak B, Duffy SW. Time-dependent effects on survival in breast carcinoma: Results of 20 years of follow-up from the Swedish two-county study. Cancer. 2014;100:1331–6. doi: 10.1002/cncr.20140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Blamey RW, Hornmark-Stenstam B, Ball G, Blichert-Toft M, Cataliotti L, Fourquet A, et al. ONCOPOOL – A European database for 16,944 cases of breast cancer. Eur J Cancer. 2010;46:56–71. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2009.09.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Amin MB, Edge S, Greene F, Byrd DR, Brookland RK, Washington MK, et al., editors. 8th ed. Springer International Publishing: American Joint Commission on Cancer; 2017. AJCC Cancer Staging Manual. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Longacre TA, Ennis M, Quenneville LA, Bane AL, Bleiweiss IJ, Carter BA, et al. Interobserver agreement and reproducibility in classification of invasive breast carcinoma: An NCI breast cancer family registry study. Mod Pathol. 2006;19:195–207. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.3800496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sloane JP, Amendoeira I, Apostolikas N, Bellocq JP, Bianchi S, Boecker W, et al. Consistency achieved by 23 European pathologists in categorizing ductal carcinoma in situ of the breast using five classifications. European Commission Working Group on breast screening pathology. Hum Pathol. 1998;29:1056–62. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Meyer JS, Alvarez C, Milikowski C, Olson N, Russo I, Russo J, et al. Breast carcinoma malignancy grading by bloom-richardson system vs. proliferation index: Reproducibility of grade and advantages of proliferation index. Mod Pathol. 2005;18:1067–78. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.3800388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Reed W, Hannisdal E, Boehler PJ, Gundersen S, Host H, Marthin J, et al. The prognostic value of p53 and c-erb B-2 immunostaining is overrated for patients with lymph node negative breast carcinoma: A multivariate analysis of prognostic factors in 613 patients with a follow-up of 14-30 years. Cancer. 2000;88:804–13. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0142(20000215)88:4<804::aid-cncr11>3.0.co;2-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Frierson HF, Jr, Wolber RA, Berean KW, Franquemont DW, Gaffey MJ, Boyd JC, et al. Interobserver reproducibility of the nottingham modification of the bloom and richardson histologic grading scheme for infiltrating ductal carcinoma. Am J Clin Pathol. 1995;103:195–8. doi: 10.1093/ajcp/103.2.195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zhang R, Chen HJ, Wei B, Zhang HY, Pang ZG, Zhu H, et al. Reproducibility of the nottingham modification of the scarff-bloom-richardson histological grading system and the complementary value of Ki-67 to this system. Chin Med J (Engl) 2010;123:1976–82. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ellis IO, Coleman D, Wells C, Kodikara S, Paish EM, Moss S, et al. Impact of a national external quality assessment scheme for breast pathology in the UK. J Clin Pathol. 2006;59:138–45. doi: 10.1136/jcp.2004.025551. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Boiesen P, Bendahl PO, Anagnostaki L, Domanski H, Holm E, Idvall I, et al. Histologic grading in breast cancer – Reproducibility between seven pathologic departments. South Sweden Breast Cancer Group. Acta Oncol. 2000;39:41–5. doi: 10.1080/028418600430950. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sikka M, Agarwal S, Bhatia A. Interobserver agreement of the nottingham histologic grading scheme for infiltrating duct carcinoma breast. Indian J Cancer. 1999;36:149–53. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Elmore JG, Tosteson AN, Pepe MS, Longton GM, Nelson HD, Geller B, et al. Evaluation of 12 strategies for obtaining second opinions to improve interpretation of breast histopathology: Simulation study. BMJ. 2016;353:i3069. doi: 10.1136/bmj.i3069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Têtu B, Evans A. Canadian licensure for the use of digital pathology for routine diagnoses: One more step toward a new era of pathology practice without borders. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2014;138:302–4. doi: 10.5858/arpa.2013-0289-ED. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Thorstenson S, Molin J, Lundström C. Implementation of large-scale routine diagnostics using whole slide imaging in Sweden: Digital pathology experiences 2006-2013. J Pathol Inform. 2014;5:14. doi: 10.4103/2153-3539.129452. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Montalto MC. An industry perspective: An update on the adoption of whole slide imaging. J Pathol Inform. 2016;7:18. doi: 10.4103/2153-3539.180014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rice S. Put it on the board. FDA Open to Whole-slide Imaging as Class II Device: CAP Today. 2016. [Last updated on 2016 Feb 19]. Available from: http://www.captodayonline. com/put-board-0216/

- 32.Elmore JG, Longton GM, Pepe MS, Carney PA, Nelson HD, Allison KH, et al. A randomized study comparing digital imaging to traditional glass slide microscopy for breast biopsy and cancer diagnosis. J Pathol Inform. 2017;8:12. doi: 10.4103/2153-3539.201920. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Parwani AV, Hassell L, Glassy E, Pantanowitz L. Regulatory barriers surrounding the use of whole slide imaging in the United States of America. J Pathol Inform. 2014;5:38. doi: 10.4103/2153-3539.143325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Elmore JG, Longton GM, Carney PA, Geller BM, Onega T, Tosteson AN, et al. Diagnostic concordance among pathologists interpreting breast biopsy specimens. JAMA. 2015;313:1122–32. doi: 10.1001/jama.2015.1405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Oster NV, Carney PA, Allison KH, Weaver DL, Reisch LM, Longton G, et al. Development of a diagnostic test set to assess agreement in breast pathology: Practical application of the Guidelines for Reporting Reliability and Agreement Studies (GRRAS) BMC Womens Health. 2013;13:3. doi: 10.1186/1472-6874-13-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Geller BM, Nelson HD, Carney PA, Weaver DL, Onega T, Allison KH, et al. Second opinion in breast pathology: Policy, practice and perception. J Clin Pathol. 2014;67:955–60. doi: 10.1136/jclinpath-2014-202290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Onega T, Weaver D, Geller B, Oster N, Tosteson AN, Carney PA, et al. Digitized whole slides for breast pathology interpretation: Current practices and perceptions. J Digit Imaging. 2014;27:642–8. doi: 10.1007/s10278-014-9683-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Division of Cancer Control and Population Sciences Healthcare Delivery Research Program. Breast Cancer Surveillance Consortium. 2015. [Last updated on 2015 Jul 06; Last accessed on 2015 Apr 16]. Available from: http://www.breastscreening.cancer.gov/

- 39.Helmer-Hirschberg O. Santa Monica, CA: The RAND Corporation; 1964. The Systematic Use of Expert Judgement in Operations Research. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Allison KH, Reisch LM, Carney PA, Weaver DL, Schnitt SJ, O’Malley FP, et al. Understanding diagnostic variability in breast pathology: Lessons learned from an expert consensus review panel. Histopathology. 2014;65:240–51. doi: 10.1111/his.12387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Agresti A. 2nd ed. New Jersey: John Wiley & Sons; 2002. Categorical Data Analysis; pp. 644–6. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Al-Janabi S, van Slooten HJ, Visser M, van der Ploeg T, van Diest PJ, Jiwa M, et al. Evaluation of mitotic activity index in breast cancer using whole slide digital images. PLoS One. 2013;8:e82576. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0082576. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Dessauvagie BF, Thomas C, Robinson C, Frost FA, Harvey J, Sterrett GF, et al. Validation of mitosis counting by automated phosphohistone H3 (PHH3) digital image analysis in a breast carcinoma tissue microarray. Pathology. 2015;47:329–34. doi: 10.1097/PAT.0000000000000248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Veta M, van Diest PJ, Willems SM, Wang H, Madabhushi A, Cruz-Roa A, et al. Assessment of algorithms for mitosis detection in breast cancer histopathology images. Med Image Anal. 2015;20:237–48. doi: 10.1016/j.media.2014.11.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Proportion of tubule/gland formation, nuclear pleomorphism, and mitotic scores assigned to 22 invasive breast carcinoma cases interpreted by same participant in Phase II, with data shown by phase and interpretive format

Interobserver agreement of Nottingham grade combined histological score for 22 invasive breast carcinoma cases by participant (a) or case characteristic (b) (Phase I, n = 17,162 paired interpretations on glass, n = 10,562 paired interpretations on digital). (a) N = 115 participants. (b) N = 22 cases