Abstract

Components of sexual minority (SM) status—including lesbian or bisexual identity, having same-sex partners, or same-sex attraction—individually predict substance use and sexual risk behavior disparities among women. Few studies have measured differing associations by sexual orientation components (identity, behavior, and attraction), particularly over time. Data were drawn from the 2002-2015 National Survey of Family Growth female sample (n = 31,222). Multivariable logistic regression (adjusted for age, race/ethnicity, education, marital/cohabitation status, survey cycle, and population-weighted) compared past-year sexual risk behavior, binge drinking, drug use, and sexually transmitted infection treatment among sexual minority women (SMW) versus sexual majority women (SMJW) by each sexual orientation component separately and by all components combined, and tested for effect modification by survey cycle. In multivariable models, SM identity, behavior, and attraction individually predicted significantly greater odds of risk behaviors. SM identity became non-significant in final adjusted models with all three orientation components; non-monosexual attraction and behavior continued to predict significantly elevated odds of risk behaviors, remaining associated with sexual risk behavior and drug use over time (attenuated in some cases). Trends in disparities over time between SMW vs. SMJW varied by sexual orientation indicator. In a shifting political and social context, research should include multidimensional sexual orientation constructs to accurately identify all SMW—especially those reporting non-monosexual behavior or attraction—and prioritize their health needs.

Keywords: sexual minority women, sexual orientation, bisexuality, non-monosexual, substance use, sexual risk behavior

INTRODUCTION

Sexual orientation is a multidimensional construct often comprised of sexual identity, sexual behavior, and sexual attraction (Badgett, 2009; Institute of Medicine, 2011). When compared to sexual majority women, sexual minority women—those who self-identify as lesbian, gay, or bisexual (LGB), or who report attraction to or sex with women—have indicated greater levels of substance use and abuse (Hughes, 2011; Lehavot & Simoni, 2011; Parsons, Kelly, & Wells, 2006) and sexual behavior associated with risk for sexually transmitted infections (STIs) and HIV (Goodenow, Szalacha, Robin, & Westheimer, 2008; Herrick, Matthews, & Garofalo, 2010; Lindley, Walsemann, & Carter, 2013).

Research regarding substance use and sexual risk among sexual minority women has varied in its operationalization of sexual orientation, from sexual identity (Hughes, Szalacha, & McNair, 2010; Parsons et al., 2006), to sexual behavior (Bolton & Sareen, 2011; Corliss, Grella, Mays, & Cochran, 2006; Eisenberg, 2001; Kerr, Ding, Burke, & Ott-Walter, 2015; Muzny, Sunesara, Martin, & Mena, 2011), to a combination of identity and behavior (Bauer, Jairam, & Baidoobonso, 2010; Goodenow et al., 2008; Kann, 2011), of identity and attraction (Corliss, Austin, Roberts, & Molnar, 2009), or of identity, behavior, and attraction (Herrick et al., 2010; McCabe, Hughes, Bostwick, West, & Boyd, 2009). Such variation is potentially problematic given that sexual identity, behavior, and attraction are often related but also likely distinct aspects of broader sexual orientation. For example, in the 2011-2013 cycle of the National Survey of Family Growth (NSFG), nearly 13% of females who identified as heterosexual had had same-sex partners and over 25% expressed attraction to women or uncertainty regarding their sexual attractions (Copen, Chandra, & Febo-Vazquez, 2016).

Observed differences in health outcomes among sexual minority vs. sexual majority populations have varied depending on how sexual orientation is measured (Wolff, Wells, Ventura-DiPersia, Renson, & Grov, 2017). Variable measurement of sexual orientation that does not capture the complexities of sexuality has obscured a full understanding of disparities in sexual risk and substance use among sexual minority women (Lindley et al., 2013; Wolff et al., 2017).

Sexual Minority Women and Sexual Behavior Related to STIs and HIV

Minimal research has examined STI/HIV-related sexual behavior among sexual minority women using multidimensional measures of sexual orientation, but studies that have done so have found variable health outcomes by different sexual orientation components. For example, one study looked at adolescent women’s engagement in HIV-related risk behaviors in terms of sexual identity and the sex of sex partners. Lesbian and bisexual identity, as well as a history of female sex partners, both independently predicted increased odds of having numerous sex partners. However, when sexual identity and the sex of sex partners were considered simultaneously, partner sex was a more salient indicator of having numerous partners, outweighing sexual identity (Goodenow et al., 2008). In a study that drew from Youth Risk Behavior Survey data, students who identified as gay or lesbian reported greater rates of previous sexual intercourse in conjunction with substance use compared to bisexually identified students in one survey site. However, when sex under the influence was measured in terms of sex of sex partners, findings were reversed: students with exclusively same-sex partners indicated lower levels of concurrent substance use and sexual intercourse compared to students who had had both male and female sex partners (Kann, 2011). Despite these variations in sexual risk behavior by sexual orientation component, some research has demonstrated that non-monosexual women—that is, women who identify as bisexual or have sex with or express attraction to both men and women—consistently report the highest rates of sexual risk compared to all other women (Everett, 2013; Muzny et al., 2011; Ripley, 2012).

Sexual Minority Women and Substance Use

Substance use outcomes among sexual minority women have also varied by sexual orientation component (Brewster & Tillman, 2012; Matthews, Blosnich, Farmer, & Adams, 2014; McCabe et al., 2009). For example, one study compared substance use and dependence among sexual minority vs. sexual majority adults in the U.S. using indicators of sexual identity, behavior, and attraction. When substance use outcomes were examined in terms of sexual identity, substance use and dependence were elevated for both lesbian and bisexually identified compared to heterosexually identified women. By contrast, when outcomes were examined in terms of sexual behavior, women who had had both male and female sex partners had significant disparities in susbtance use and dependence, but women who had only had female sex partners were no different from those with only male partners (McCabe et al., 2009). In a study of substance use among youth, sexual minority identity was significantly associated with substance use disparities when measured separately from attraction and behavior, but similar to the aforementioned study of HIV-related risk behaviors, identity was no longer significant when regression models also adjusted for sexual attraction and behavior (Brewster & Tillman, 2012). Despite variations by sexual orientation component, non-mono sexual women have also emerged with the greatest substance use disparities compared to other women (Przedworski, McAlpine, Karaca-Mandic, & VanKim, 2014).

Mechanisms of Risk among Sexual Minority Women in the Context of Policy Changes

Minority stress theory suggests that sexual minority individuals experience unique stressors associated with having a sexual minority status (Meyer, 2003). Research has documented a link between experiences of minority stress (e.g., stigma, discrimination, and internalized homophobia) and adverse health outcomes for sexual minority individuals, with stress spurring negative mental health processes (Hatzenbuehler, 2009; Meyer, 2003), substance use (Lehavot & Simoni, 2011), and sexual risk behavior (Goodenow et al., 2008) as potential resultant coping responses.

Some research suggests that sexual identity is a key predictor of health risk behaviors given that openly identifying as a sexual minority exposes individuals to greater likelihood of discrimination, stigma, and violence (McCabe et al., 2009). However, additional research purports that disclosing one’s sexual identity may be protective against health risk behaviors given that disclosure allows for greater access to social support (Juster, Smith, Ouellet, Sindi, & Lupien, 2013). Although some research has shown how different components of sexual orientation differentially predict health disparities for sexual minorities, research remains less conclusive on which sexual orientation components are the most relevant for understanding health disparities among sexual minority women.

Further confounding an understanding of the relationship between various sexual orientation components and health outcomes is how a rapidly evolving political and social climate in the U.S. may impact sexual minority health disparities. Research suggests that a policy environment more favorable to sexual minorities can mitigate minority stress (Hatzenbuehler, McLaughlin, Keyes, & Hasin, 2010; Pachankis et al., 2017). When discrimination and stigma have dissipated and legal protections against discrimination have created a sense of security for sexual minorities, risk behaviors that once functioned as stress coping mechanisms could have also declined (Hatzenbuehler et al., 2010). Between 2000 and 2009, policy changes reflected such growing support of sexual minorities (Movement Advancement Project, 2010). For example, support for permitting openly gay individuals to serve in the military and for gay and lesbian people to adopt children both increased by 21%. The number of states prohibiting sexual orientation-related discrimination increased from 12 to 22, the percent of Fortune 500 companies prohibiting job-based sexual orientation-related discrimination increased from 0.6% to 35%, and the passage of the 2009 Matthew Shepard and James Byrd, Jr. Hate Crimes Prevention Act marked the first U.S. federal law to increase punishment of hate crimes against sexual minorities (Movement Advancement Project, 2010). In 2015, the U.S. Supreme Court pronounced same-sex marriage legal at the federal level (Chappell, 2015).

Much of the existing literature examining the political influence on the health of sexual minorities has treated sexual minority individuals as a composite group without exploring differential effects for various sexual minority and gender subgroups. Most of these studies have measured sexual minority status in terms of sexual identity alone (Hatzenbuehler, 2009, 2011; Hatzenbuehler et al., 2010; Hatzenbuehler, Wieringa, & Keyes, 2011), despite sexual orientation being a multifaceted construct (Laumann, Gagnon, Michael, & Michaels, 1994) with only moderate correlations between sexual identity, behavior, and attraction (Brewster & Tillman, 2012). To our knowledge, only one study examining the impact of structural stigma on sexual minority health has also included sexual attraction and behavior as elements of sexual orientation (Pachankis et al., 2017). Furthermore, although recent research has examined changing trends in health disparities between sexual minorities and sexual majority individuals, these studies have focused on youth and have employed singular measures of sexual orientation (Fish, Watson, Porta, Russell, & Saewyc, 2017; Watson, Goodenow, Porta, Adjei, & Saewyc, 2017).

In addition to policy advances, the new millennium also ushered in increasing social acceptance of sexual minorities (Movement Advancement Project, 2010; Twenge, Sherman, & Wells, 2016). Between 2000 and 2009, the proportion of Americans viewing same-sex relationships as morally acceptable increased by 23% (Movement Advancement Project, 2010). According to the General Social Survey (GSS), the proportion of U.S. adults who perceived same-sex sexual behavior as “not wrong at all” increased from 11% in 1973 to 49% in 2014 (Twenge et al., 2016).

Despite increasingly positive attitudes toward same-sex sexual behavior and burgeoning policy protections for LGB individuals more broadly, research has not found growing positivity toward bisexually identified individuals (Dodge et al., 2016). Perceptions of same-sex relationships do not capture changes in attitudes toward non-monosexual individuals in same- vs. different-sex relationships. Moreover, policies more favorable to sexual minorities may not address the stigma and stereotyping of non-monosexual people that persist among both heterosexual and sexual minority communities (Brewster & Moradi, 2010; Dyar, Feinstein, & London, 2014; Wandrey, Mosack, & Moore, 2015). Because of such ongoing stigma, non-monosexual people may continue to lack community support (Ross et al., 2018) and to face limited social acceptance (Dyar, Feinstein, Schick, & Davila, 2017) regardless of policies that protect against discrimination at an institutional level.

Present Study

In order to understand how each component of sexual orientation contributes to health disparities, both among sexual minority women and compared to sexual majority women, multidimensional measurement of sexual orientation is critical (Wolff et al., 2017). This is especially true in the context of a rapidly shifting political and social environment that can influence the health of sexual minorities overtime (Hatzenbuehler et al., 2010). Specific attention to women who express non-monosexual identity, attraction, and/or sex with more than one sex or gender is also vital given that attitudes toward bisexually identified people have not advanced at the same pace as attitudes toward same-sex relationships more broadly (Dodge et al., 2016).

Using 2002-2015 data from the NSFG, we sought to examine the association of risk behaviors with women’s sexual minority status—with sexual orientation defined in terms of sexual identity, behavior, and attraction—and to explore whether these associations have changed over time as policies implemented during the same period of survey data collection became increasingly supportive of sexual minorities (Movement Advancement Project, 2010).

METHOD

Participants

Data for this study were drawn from the NSFG, a national survey weighted to be representative of the U.S. population age 15 to 44 (Lepkowski et al., 2013). The NSFG began collecting sexual orientation data in its 2002 sample (Groves, Mosher, Lepkowski, & Kirgis, 2009); thus, this study used a combined NSFG dataset from 2002 to 2015 (the most current dataset available at the time of data analysis). The NSFG is unique as one of the few national health surveys to collect data on sexual identity, behavior, and attraction (Wolff et al., 2017).

The NSFG 2002 (Cycle 6) sample included 7,643 female respondents (80% response rate) out of a total sample of 12,571. For the 2006-2010 cycle (continuous interviewing over the cycle), interviews were completed for 48 weeks of each year from June 2006 through June 2010. The sample included 12,279 female respondents (77.7% response rate) out of a total sample of 22,682. The 2011-2015 interviews occurred from September 2011 through September 2015 and included a sample of 11,300 female respondents (response rate 72.3%) out of a total sample of. 20,621 (National Center for Health Statistics, 2016a). Despite the change from 12-month to multi-year data interviewing cycles in the NSFG (Groves et al., 2009), the survey items of interest for the present study remained identical.

Measures

Sexual Orientation

The primary independent variables were the three aforementioned sexual orientation components: sexual identity, sexual attraction, and sexual behavior.

Sexual identity was assessed by responses to the question: “Do you think of yourself as: heterosexual or straight; (2) homosexual, gay, or lesbian; (3) bisexual; or (4) something else?” (Reference = heterosexual/straight). Given that “something else” was not available as a response option in the 2011-2015 survey cycle, we excluded those who identified as such from this analysis.

Sexual attraction was assessed by responses to the question: “People are different in their sexual attraction to other people. Which best describes your feelings? (1) only attracted to males; mostly attracted to males; (3) equally attracted to males and females; (4) mostly attracted to females; (5) only attracted to females; or (6) not sure.” We collapsed responses into a four-category variable: (1) only attracted to males; (2) only attracted to females; (3) attracted to both males and females; or (4) not sure (reference = only attracted to males). “Not sure” was retained for this analysis as a separate category within the four-item variable given that we could not ascertain whether these respondents were simply unsure of their sexual attraction, if they misunderstood the other response options, or if they would have indicated exclusive attraction to males, females, or both had they not been given the “not sure” response option.

Sexual behavior in this analysis was limited to measurement of past-year behavior with male and/or female partners (partner gender identity was not assessed) given that women’s sexual behavior may be fluid across the lifespan as their sexual desires and identity evolve (Diamond, 2003; Meyer & Wilson, 2009). Our sexual behavior variable included four categories: past-year sexual behavior (i.e., oral, vaginal, or anal sex) with (1) only male partners; (2) only female partners; (3) both male and female partners; and (4) no past-year partners (reference = only male partners).

Demographic Characteristics

Demographic characteristics included age in years, race/ethnicity (Hispanic, any race; Black/African-American, non-Hispanic; White, non-Hispanic; and any other race, non-Hispanic), education level (no high school degree to Bachelor’s degree or higher), and marital/cohabitation status (married to/living with versus not married to/not living with a partner). Participants were only directly asked about their marital/cohabitation status with an “opposite sex” partner. NSFG recorded voluntary responses about same-sex partnerships as comments but same-sex relationship status was not formally assessed nor was it integrated into the responses to the marital/cohabitation status question.

STI/HIV-Related Sexual Risk Behavior

We measured past-year STI/HIV-related sexual risk behavior as having engaged in any sexual risk behavior with male partners (again, partner gender identity was not assessed) in the past year, defined as any self-reported transactional sex, sex with male partners with high HIV risk (i.e., HIV-positive males, males who used injection drugs, males who had sex with males, or males who had other concurrent partners of any sex), having had five or more male partners in the past year, or any past-year condomless penile-vaginal intercourse with male partners. Given that the NSFG did not assess for it, we were unable to examine HIV and STI-related sexual risk behaviors with female partners. Any past-year condomless sex was assessed by the following question: “Thinking back over the past 12 months, would you say you used a condom with your partner for sexual intercourse [which referred to penile-vaginal intercourse]: (1) every time; (2) most of the time; (3) about half the time; (4) some of the time; (5) none of the time.” We collapsed responses into a dichotomous indicator for any past year condomless sex (responses two through five), which was included within the larger sexual risk behavior variable. Anal sex was not included given that the NSFG only asked about condom use at last, rather than any, occurrence of anal sex within the previous year.

STI Treatment

We defined STI treatment as report of having been treated for gonorrhea, chlamydia, herpes, or syphilis over the past year. This variable was used in place of a variable assessing for STI diagnoses because in the 2002 and 2006-2010 survey cycles, participants were only asked questions about whether they had received an actual STI diagnosis if they first responded “yes” to questions about whether they had been treated for an STI. As such, using the STI treatment variable avoided excluding participants who may have been diagnosed, but who did not receive treatment for STIs.

Recreational Drug Use

The NSFG assessed past-year recreational drug use in four separate questions using the following language: “During the last 12 months, how often have you: [Question 1] smoked marijuana? [Question 2] used cocaine? [Question 3] used crack? [Question 4] used crystal or meth, also known as tina, crack, or ice?” A fifth question asked, “During the last 12 months, how often have you shot up or injected drugs other than those prescribed to you? “ Response options ranged from “never” to “about once a day.” For this study, we measured recreational drug use in the past year as having used any of the aforementioned substances or engaging in non-prescription injection drug use at least once in the past 12 months. Although crystal methamphetamine use was not assessed in the 2002 sample, meth use was included in the drug use indicator given that all but 5 respondents in the 2006-2010 and 2011-2015 samples that had used crystal methamphetamine had also used other drugs.

Binge Drinking

Binge drinking was assessed through the following question: “During the last 12 months, how often did you have 4 or more drinks within a couple of hours? (1) never; (2) once or twice during the year; (3) several times during the year; (4) about once a month; (5) about once a week; (6) about once a day?” For the purposes of this analysis, we used the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration definition of binge drinking (National Center on Alcohol Use and Alcoholism, n.d.), which is operationalized as (females) having four or more drinks on one occasion at least once a month (responses 4-6).

Data Analyses

Analyses were conducted on the merged 2002, 2006-2010, and 2011-2015 NSFG female datasets, which the NSFG maintains separately from the male datasets. Weights were adjusted to account for the different survey cycles (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2014).

We first describe the sample overall and stratified by each sexual orientation measure and with sexual orientation and health behaviors stratified by survey cycle. The Rao Scott modified chi square test was used to assess the significance of associations between sexual orientation indicators and categorical variables. Next, we examined the proportion of those within each sexual orientation group reporting each health outcome, stratified across survey cycles. Separate crude logistic regression models then explored the association of each of the three indicators of sexual orientation—sexual identity, sexual behavior, and sexual attraction—with each heath outcome.

Subsequently, four separate multivariable logistic regression models were run for each health outcome, with each model adjusted for age, race, ethnicity, education level, survey cycle, and marital/cohabitation status. The first set of regression models (Models A1 through A4) included sexual identity as the main predictor for each separate outcome, the second set (Models B1 through B4) included past-year sexual attraction as the main predictor, and the third set (Models Cl through C4) included sexual behavior. Finally, we ran an additional set of models (Models D1 through D4) that included all three measures of sexual orientation to look at their independent associations; a separate model was run for each of the four outcomes.

Chi square tests using Cramer’s V coefficients explored correlations between each indicator of sexual orientation to ensure that the indicators were not highly correlated and could be included in the same regression model. Sexual attraction and sexual identity—as well as identity and sexual behavior—were moderately correlated with Cramer’s V coefficients of 0.59 and 0.53 respectively; sexual behavior and sexual attraction had a low correlation with a Cramer’s v coefficient of 0.37.

We then ran the final adjusted models (Models D1 through D4) including all the aforementioned characteristics but leaving out marital/cohabitation status as a sensitivity analysis to see if the results differed without adjustment for this variable, which excluded marital/cohabitation with same-sex partners. The sensitivity analysis also addressed the fact that the large proportion of women reporting past-year sexual risk behavior was driven by the over 90% of married/cohabiting and about 82% of unmarried/not cohabiting respondents who reported condomless sex within the past year. Given that excluding marital/cohabitation status as a potential covariate had a minimal overall effect on the association between sexual minority status and the primary outcomes, the multivariable results include marital/cohabitation status as a covariate.

For Models D1 through D4 (the models that included all three measures of sexual orientation simultaneously), we then assessed whether the association between sexual minority status and each outcome differed by NSFG survey cycle by adding interaction terms for survey cycle by each of the three measures of sexual orientation, using separate interaction terms for each sexual orientation indicator. We were not able to examine interactions of sexual orientation by individual year of survey interview given that discrete interview years are not publicly available (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2017). If the p-value for any of the interaction terms was significant, final combined models were stratified on survey cycle to examine the direction of the effect modification. We report on trends in health outcomes among sexual minority vs. heteterosexual women and women attracted to/who had had sex with only males across survey cycles, focusing on where we observed significant interactions of sexual orientation indicators and survey cycle (Homma, Saewyc, & Zumbo, 2016).

Women who had not had sex with a male partner within the past year were excluded from models examining STI/HIV-related sexual risk behavior (Models A1 through D1). For the models exploring past-year STI treatment, given that only 21 lesbian identified women, 17 women exclusively attracted to females, and five who had sex only with women in the past year reported any past-year STI treatment, these groups were excluded from the adjusted models.

All analyses accounted for the complex sampling method and were weighted to the population. Analyses were performed in SAS 9.3 (SAS Institute, Cary NC) using the proc survey functions. Statistical significance was set at an alpha of .05 for regression models and an alpha of .10 for interaction terms, given that power decreases when examining effect modification (Marshall, 2007).

RESULTS

Table 1 displays demographic characteristics of the female U.S. population drawn from NSFG data, 2002 to 2015. The mean age was 29.68 years (SE = 0.09). About 41% of the sample was legally married to or living with an opposite-sex partner (40.93%) and the majority identified as non-Hispanic white (60.81%). Roughly a quarter of women fell within each category of education level. Most women reported a heterosexual identity (93.68%), being exclusively attracted to males (85.52%), and having had only male partners during the previous year (90.46%).

Table 1.

Demographic Characteristics, National Survey of Family Growth. 2002-2015. Females Aged 15-44 (N=31,222)a

| Unweighted n (weighted %)/M age (SE) | |

|---|---|

| Sexual Identity | |

| Heterosexual | 38,217 (93.68) |

| Gay/lesbian | 508 (1.47) |

| Bisexual | 1,648 (4.99) |

| Sexual Attraction | |

| Only to Males | 25,286 (85.52) |

| Only to Females | 315 (0.88) |

| To Both | 5,068 (15.62) |

| Not sure | 337 (0.99) |

| Sexual Behavior, Past Year | |

| Only Males | 23,417 (90.46) |

| Only Females | 365 (1.26) |

| Both | 1,087 (3.54) |

| No Sex Partners | 1,495 (4.74) |

| Race & Ethnicity | |

| Hispanic (any race) | 7,164 (17.96) |

| Black, Non-Hispanic | 6,485 (14.46) |

| Other Race, Non-Hispanic | 1,848 (6.78) |

| White, Non-Hispanic | 15,725 (60.81) |

| Education Level | |

| No High School | 7657 (20.64) |

| High School/GED | 8,069 (25.05) |

| Some College/Associate’s | 8,864 (29.14) |

| Bachelor’s or Higher | 6,631 (25.18) |

| Married/living with partner | 10,461 (40.93) |

| Age (continuous) | 29.68 (0.09) |

Total n may not add up to 100% due to missing responses.

Table 2 shows the overall proportion within sexual orientation category and engaging in past-year risk behaviors, as well as stratified by NSFG survey cycle. Overall, 87.50% of women who had sex with a male partner in the past year reported any STI/HIV-related sexual risk behavior during that time, but as noted, this was driven by the over 90% of married/cohabiting women who reported any past-year condomless sex with a male partner. Nearly 4% of women reported having received STI treatment within the previous year. Close to 15% of women reported binge drinking once a month or more within the past year; 16.37% indicated any past-year recreational drug use (including marijuana). From 2002 to 2011-2015, women were significantly less likely to report sexual risk behavior (89.43% in 2002 vs. 87.22% in 2011-2015, p = .001) and binge drinking (16.87% in 2002 vs. 12.44% in 2011-2015, p < .001) (Table 2). Despite these declines, health disparities largely persisted between sexual minority and sexual majority women regardless of how sexual orientation was measured (see Table 3). We further describe specific trends below in the context of effect modification.

Table 2.

Sexual Orientation & Past-Year Health Behaviors Stratified by National Survey of Family Growth Survey Cycles,2002-2015, Females Aged 15-44 (N = 31,222)a

| 2002 (n = 7,643) | 2006-2010 (n = 12,279) | 2011-2015 (n = 11,300) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unweighted N (weighted %)/M age (SD) | Unweighted n (weighted %) | Unweighted n (weighted %) | Unweighted n (weighted %) | χ2 | pb | |

| Sexual Orientation | ||||||

| Sexual Identity | ||||||

| Heterosexual | 38,217 (93.68) | 6,780 (95.35) | 11,275 (94.54) | 10,162 (92.27) | 43.87 | < .001 |

| Gay/lesbian | 508 (1.47) | 100 (1.34) | 197 (1.23) | 211 (1.64) | 4.20 | .123 |

| Bisexual | 1,648 (4.99) | 258 (3.29) | 591 (4.24) | 799 (6.18) | 54.21 | < .001 |

| Sexual Attraction | ||||||

| Only to Males | 25,286 (85.52) | 6,483 (85.78) | 9,960 (82.92) | 8,843 (80.41) | 42.52 | < .001 |

| Only to Females | 315 (0.88) | 56 (0.67) | 124 (0.77) | 135 (1.07) | 6.00 | .050 |

| To Both | 5,068 (15.62) | 987 (12.75) | 1,985 (15.55) | 2,096 (17.30) | 34.65 | < .001 |

| Not sure | 337 (0.99) | 70 (0.80) | 117 (0.76) | 150 (1.22) | 7.49 | .023 |

| Sexual Behavior, Past Year | ||||||

| Only Males | 23,417 (90.46) | 5,925 (90.06) | 9,208 (89.87) | 8,284 (91.05) | 3.43 | .179 |

| Only Females | 365 (1.26) | 92 (1.33) | 160 (1.11) | 113 (1.31) | .88 | .645 |

| Both | 1,087 (3.54) | 222 (3.37) | 439 (3.48) | 426 (3.68) | .67 | .717 |

| No Sex Partners | 1,495 (4.74) | 410 (5.25) | 733 (5.53) | 352 (3.96) | 13.41 | .001 |

| Health Behaviors, Past Year | ||||||

| Sexual risk behaviorc | 19,628 (87.50) | 4,918 (89.43) | 7,576 (86.09) | 7,134 (87.22) | 14.37 | .001 |

| Received medication for STIs | 1,504 (3.93) | 310 (3.38) | 591 (4.00) | 603 (4.21) | 5.89 | .052 |

| Binge drinking ≥ once a month | 3,590 (14.81) | 951 (16.87) | 1,542 (16.95) | 1,097 (12.44) | 34.20 | < .001 |

| Any recreational drug use | 5,571 (16.37) | 1,308 (16.39) | 2,220 (16.63) | 2,043 (16.20) | .24 | .885 |

Total n may not add up to 100% due to missing responses.

Results based on Rao-Scott modified chi square tests.

Sexual risk behavior defined as: any self-reported past-year transactional sex with male partners, any sex with male partners with high HIV risk (i.e., HIV-positive males, males who use injection drugs, males who had sex with males, or males who had other concurrent partners of any sex), any sex with five or more male partners, or any condomless penile-vaginal intercourse with male partners.

Table 3.

Past-Year Health Behaviors by Sexual Orientation and National Survey of Family Growth Survey Cycles, 2002-2015, Females Aged 15-44 (N = 31,222) a

| Sexual Orientation | Unweighted N | Health Behavior Unweighted n (weighted %) | 2002 Unweighted n (weighted %) | 2006-2010 Unweighted n (weighted %) | 2011-2015 Unweighted n (weighted %) | χ2 | p b |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| STI/HIV-Related Sexual Risk Behavior c | |||||||

| Sexual Identity | |||||||

| Heterosexual | 38,217 | 18,103 (87.37) | 4,462 (89.14) | 7,082 (86.06) | 6,559 (87.14) | 11.40 | .003 |

| Gay/lesbian | 508 | 82 (78.32) | 31 (89.14) | 27 (80.53) | 24 (62.98) | 28.32 | < .001 |

| Bisexual | 1,648 | 1,093 (89.81) | 172 (94.17) | 401 (87.57) | 520 (89.53) | 4.90 | .087 |

| Sexual Attraction | |||||||

| Only to Males | 25,286 | 15,905 (87.23) | 4,181 (89.48) | 6,111 (85.35) | 5,613 (86.96) | 18.53 | < .001 |

| Only to Females | 315 | 47 (72.29) | 14 (83.51) | 17 (80.78) | 16 (59.38) | 292.96 | < .001 |

| To Both | 5,068 | 3,519 (89.07) | 690 (89.19) | 1,400 (90.04) | 1,429 (88.50) | 0.97 | .615 |

| Not sure | 337 | 141 (89.68) | 28 (93.22) | 47 (79.93) | 66 (92.44) | 11.21 | .004 |

| Sexual Behavior, Past Year | |||||||

| Only Males | 23,417 | 18,608 (87.39) | 4,697 (89.22) | 7,184 (86.00) | 6,727 (87.17) | 12.75 | .002 |

| Only Females | 365 | 0 (0.00) | 0 (0.00) | 0 (0.00) | 0 (0.00) | -- | -- |

| Both | 1,087 | 943 (90.46) | 192 (93.44) | 379 (88.25) | 372 (90.13 | 3.00 | .223 |

| No Sex Partners | 1,495 | 0 (0.00) | 0 (0.00) | 0 (0.00) | 0 (0.00) | -- | -- |

| Received Medication for STIs | |||||||

| Sexual Identity | |||||||

| Heterosexual | 38,217 | 1,295 (3.73) | 264 (3.20) | 508 (3.75) | 523 (4.02) | 4.92 | .086 |

| Gay/lesbian | 508 | 21 (2.74) | 2 (2.52) | 11 (3.73) | 8 (2.41) | 1.15 | .564 |

| Bisexual | 1,648 | 144 (6.88) | 15 (5.54) | 63 (9.17) | 66 (6.36) | 3.04 | .221 |

| Sexual Attraction | |||||||

| Only to Males | 25,286 | 1,063 (3.44) | 241 (3.10) | 408 (3.31) | 414 (3.73) | 3.22 | .200 |

| Only to Females | 315 | 17 (4.12) | 3 (4.54) | 5 (4.00) | 9 (4.02) | 0.06 | .968 |

| To Both | 5,068 | 394 (6.38) | 59 (5.16) | 171 (7.81) | 164 (6.16) | 4.19 | .123 |

| Not sure | 337 | 27 (5.93) | 6 (4.73) | 7 (2.55) | 14 (5.60) | 5.12 | .080 |

| Sexual Behavior | |||||||

| Only Males | 23,417 | 1,236 (4.28) | 260 (3.70) | 490 (4.41) | 486 (4.55) | 4.48 | .106 |

| Only Females | 365 | 5 (1.50) | 1 (1.69) | 2 (0.81) | 2 (1.74) | 0.53 | .767 |

| Both | 1,087 | 158 (12.05) | 20 (8.70) | 73 (12.89) | 65 (13.41) | 2.19 | .334 |

| No Sex Partners | 1,495 | 37 (2.32) | 15 (2.56) | 13 (1.77) | 9 (2.58) | 0.42 | .811 |

| Any Recreational Drug Use | |||||||

| Sexual Identity | |||||||

| Heterosexual | 38,217 | 4,576 (14.83) | 1,099 (15.46) | 1,851 (15.11) | 1,626 (14.32) | 1.93 | .380 |

| Gay/lesbian | 508 | 171 (32.40) | 21 (20.55) | 75 (41.02) | 75 (34.13) | 12.22 | .002 |

| Bisexual | 1,648 | 723 (42.34) | 116 (42.63) | 270 (44.75) | 337 (41.31) | 0.82 | .665 |

| Sexual Attraction | |||||||

| Only to Males | 25,286 | 3,434 (12.46) | 883 (13.37) | 1,384 (12.38) | 1.167 (11.94) | 3.20 | .203 |

| Only to Females | 315 | 109 (34.12) | 15 (21.97) | 45 (38.91) | 49 (36.50) | 8.62 | .013 |

| To Both | 5,068 | 1,963 (36.11) | 395 (36.66) | 772 (38.68) | 796 (34.55) | 3.48 | .176 |

| Not Sure | 337 | 57 (18.90) | 12 (19.32) | 18 (12.54) | 27 (21.03) | 1.60 | .448 |

| Sexual Behavior | |||||||

| Only Males | 23,417 | 4,125 (15.89) | 988 (15.72) | 1,662 (16.54) | 1,475 (15.61) | 1.05 | .591 |

| Only Females | 365 | 113 (25.08) | 23 (23.36) | 58 (36.61) | 32 (20.32) | 6.22 | .044 |

| Both | 1,087 | 621 (55.42) | 137 (61.45) | 256 (56.83) | 228 (51.36) | 3.04 | .218 |

| No Sex Partners | 1,495 | 148 (9.64) | 38 (9.17) | 71 (8.52) | 39 (10.95) | 1.02 | .600 |

| Binge Drinking at Least Once a Month | |||||||

| Sexual Identity | |||||||

| Heterosexual | 38,217 | 3,075 (13.83) | 797 (15.71) | 1,369 (16.01) | 909 (11.53) | 30.92 | < .001 |

| Gay/lesbian | 508 | 102 (25.41) | 21 (27.89) | 39 (25.79) | 42 (19.58) | 10.10 | .006 |

| Bisexual | 1,648 | 323 (25.83) | 62 (30.45) | 121 (28.92) | 140 (23.25) | 4.33 | .115 |

| Sexual Attraction | |||||||

| Only to Males | 25,286 | 2,487 (12.92) | 701 (15.10) | 1,080 (14.74) | 706 (10.57) | 30.45 | < .001 |

| Only to Females | 315 | 71 (26.33) | 15 (29.46) | 28 (41.19) | 28 (19.18) | 14.05 | .001 |

| To Both | 5,068 | 984 (22.30) | 218 (25.34) | 420 (25.47) | 346 (19.37) | 10.33 | .006 |

| Not Sure | 337 | 43 (27.05) | 15 (49.03) | 13 (29.98) | 15 (17.26) | 33.90 | < .001 |

| Sexual Behavior | |||||||

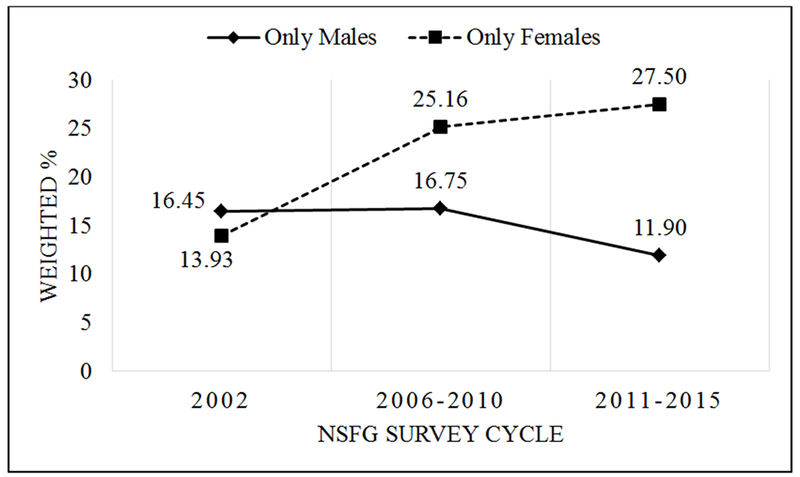

| Only Males | 23,417 | 2,840 (14.40) | 764 (16.45) | 1,238 (16.75) | 838 (11.90) | 30.73 | < .001 |

| Only Females | 365 | 67 (23.17) | 14 (13.93) | 31 (25.16) | 22 (27.50) | 3.75 | .153 |

| Both | 1,087 | 335 (37.70) | 74 (42.68) | 148 (44.00) | 113 (32.45) | 6.63 | .036 |

| No Sex Partners | 1,495 | 89 (9.27) | 24 (12.54 | 49 (10.87) | 16 (5.64) | 4.87 | .088 |

Total N may not add up to 100% due to missing responses.

Results based on Rao-Scott modified chi square tests.

Sexual risk behavior defined as: any self-reported past-year transactional sex with male partners, any sex with male partners with high HIV risk (i.e., HIV-positive males, males who use injection drugs, males who had sex with males, or males who had other concurrent partners of any sex), any sex with five or more male partners, or any condomless penile-vaginal intercourse with male partners.

Logistic Regressions, Interactions, and Stratified Models

Table 4 shows results of unadjusted (crude) logistic regression models and results of the combined adjusted Models D1-D4. Table 5 shows interactions between each sexual orientation component and each NSFG survey cycle. Table 6 shows final adjusted models stratified by survey cycle.

Table 4.

Logistic Regression Models, National Survey of Family Growth, 2002-2015, Females Aged 15-44

| Crude Associations | Final Multivariable Models a | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR (95% CI) | p | AOR (95% CI) | p | |

| Past-Year STI/HIV-Related Sexual Risk Behaviors b (Final Multivariable Model D1, n = 22,140) | ||||

| Sexual Identity | n = 22,230 | |||

| Heterosexualc | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||

| Gay/Lesbian | 0.52 (0.26, 1.07) | .076 | 0.57 (0.28, 1.17) | .123 |

| Bisexual | 1.28 (0.98, 1.67) | .075 | 1.10 (0.80, 1.51) | .548 |

| Sexual Attraction | n = 22,600 | |||

| Only to Males c | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||

| Only to Females | 0.38 (0.16, 0.92) | .033 | 0.40 (0.14, 1.16) | .093 |

| To Both | 1.19 (1.02, 1.40) | .030 | 1.26 (1.04, 1.53) | .016 |

| Not Sure | 1.27 (0.60, 2.71) | .527 | 1.29 (0.54, 3.22) | .588 |

| Sexual Behavior, Past Year | n = 22,531 | |||

| Only Males c | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||

| Only Females | d | -- | d | |

| Both | 1.37 (1.04, 1.79) | .024 | 1.75 (1.29, 2.37) | < .001 |

| No Sex Partners | d | -- | d | |

| Survey Cycle | n = 22,621 | |||

| 2002c | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||

| 2006-2010 | 0.73 (0.63, 0.85) | < .001 | 0.76 (0.66, 0.89) | .001 |

| 2011-2015 | 0.81 (0.69, 0.94) | .007 | 0.84 (0.73, 0.98) | .030 |

| n = 22,621 | ||||

| Age (continuous) | 1.05 (1.04, 1.05) | < .001 | 1.04 (1.03, 1.04) | < .001 |

| Race & Ethnicity | n = 22,621 | |||

| Hispanic, Any Race | 0.82 (0.71, 0.94) | .006 | 0.83 (0.71, 0.97) | .018 |

| Black, Non-Hispanic | 0.78 (0.68, 0.89) | < .001 | 0.94 (0.81, 1.09) | .423 |

| Other Race, Non-Hispanic | 0.66 (0.53, 0.81) | < .001 | 0.70 (0.56, 0.87) | .001 |

| White, Non-Hispanic c | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||

| Education Level | n = 22,621 | |||

| No High School | 0.92 (0.78, 1.06) | .231 | 1.47 (1.24, 1.73) | < .001 |

| High School/GED | 1.32 (1.11, 1.57) | .002 | 1.70 (1.43, 2.01) | < .001 |

| Some College/Associate’s | 1.07 (0.94, 1.23) | .314 | 1.39 (1.21, 1.59) | .018 |

| Bachelor’s or Higher c | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||

| Married/Living with Partner | n = 22,621 | |||

| Yes | 2.05 (1.83, 2.30) | < .001 | 2.24 (1.99, 2.53) | < .001 |

| No c | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||

| Received Medication for STIs in the Past Year (Final Multivariable Model D2, n = 25,289) | ||||

| Sexual Identity | n = 30,339 | |||

| Heterosexualc | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||

| Gay/Lesbian | 0.73 (0.41, 1.28) | .268 | d | |

| Bisexual | 1.91 (1.43, 2.53) | < .001 | 0.78 (0.54, 1.15) | .213 |

| Sexual Attraction | n = 30,971 | |||

| Only to Males c | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||

| Only to Females | 1.21 (0.67, 2.19) | .535 | d | |

| To Both | 1.92 (1.58, 2.32) | < .001 | 1.58 (1.24, 2.02) | < .001 |

| Not Sure | 1.77 (1.01, 3.10) | .047 | 0.95 (0.47, 1.93) | .888 |

| Sexual Behavior, Past Year | n = 26,342 | |||

| Only Males c | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||

| Only Females | 0.34 (0.11, 1.05) | .060 | d | |

| Both | 3.06 (2.29, 4.10) | < .001 | 1.77 (1.24, 2.52) | .002 |

| No Sex Partners | 0.53 (0.30, 0.93) | .027 | 0.42 (0.23, 0.76) | .004 |

| Survey Cycle | n = 31,040 | |||

| 2002 c | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||

| 2006-2010 | 1.91 (1.00, 1.43) | .057 | 1.18 (0.97, 1.43) | .100 |

| 2011-2015 | 1.26 (1.04, 1.51) | .018 | 1.25 (1.01, 1.54) | .042 |

| n = 31,040 | ||||

| Age (continuous) | 0.97 (0.96, 0.98) | < .001 | 0.97 (0.96, 0.98) | < .001 |

| Race & Ethnicity | n = 31,040 | |||

| Hispanic, Any Race | 1.28 (1.02, 1.59) | .031 | 1.15 (0.87, 1.49) | .297 |

| Black, Non-Hispanic | 2.21 (1.85, 2.65) | < .001 | 1.72 (1.40, 2.10) | < .001 |

| Other Race, Non-Hispanic | 1.22 (0.81, 1.84) | .349 | 1.26 (0.76, 2.11) | .372 |

| White, Non-Hispanic c | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||

| Education Level | n = 31,040 | |||

| No High School | 1.95 (1.49, 2.56) | < .001 | 1.75 (1.30, 2.37) | < .001 |

| High School/GED | 1.84 (1.41, 2.40) | < .001 | 1.35 (1.03, 1.78) | .029 |

| Some College/Associate’s | 1.70 (1.27, 2.27) | < .001 | 1.31 (0.98, 1.75) | .065 |

| Bachelor’s or Higher c | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||

| Married/Living with Partner | n = 31,040 | |||

| Yes | 0.55 (0.46, 0.65) | < .001 | 0.54 (0.45, 0.64) | < .001 |

| No c | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||

| Any Past-Year Recreational Drug Use (Final Multivariable Model D3, n = 25,792) | ||||

| Sexual Identity | n = 30,323 | |||

| Heterosexual c | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||

| Gay/Lesbian | 2.75 (2.13, 3.54) | < .001 | 0.81 (0.50, 1.31) | .381 |

| Bisexual | 4.22 (3.59, 4.95) | < .001 | 1.14 (0.90, 1.43) | .272 |

| Sexual Attraction | n = 30,956 | |||

| Only to Males c | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||

| Only to Females | 3.64 (2.62, 5.06) | < .001 | 3.11 (1.84, 5.26) | < .001 |

| To Both | 3.97 (3.61, 4.38) | < .001 | 2.91 (2.54, 3.34) | < .001 |

| Not Sure | 1.64 (1.01, 2.67) | .048 | 2.03 (1.23, 3.34) | .006 |

| Sexual Behavior, Past Year | n = 26,372 | |||

| Only Males c | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||

| Only Females | 1.77 (1.27, 2.47) | .001 | 0.52 (0.34, 0.91) | .004 |

| Both | 6.58 (5.27, 8.21) | < .001 | 2.21 (1.70, 2.88) | < .001 |

| No Sex Partners | 0.57 (0.34, 0.74) | < .001 | 0.42 (0.31, 0.56) | < .001 |

| Survey Cycle | n = 31,057 | |||

| 2002 c | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||

| 2006-2010 | 1.02 (0.98, 1.16) | .795 | 0.99 (0.86, 1.14) | .903 |

| 2011-2015 | 0.99 (0.87, 1.12) | .834 | 0.91 (0.79, 1.05) | .206 |

| n = 31,057 | ||||

| Age (continuous) | 0.94 (0.94, 0.95) | < .001 | 0.94 (0.94, 0.95) | < .001 |

| Race & Ethnicity | n = 31,057 | |||

| Hispanic, Any Race | 0.67 (0.60, 0.76) | < .001 | 0.57 (0.49, 0.66) | < .001 |

| Black, Non-Hispanic | 1.04 (0.94, 1.16) | .445 | 0.78 (0.69, 0.88) | < .001 |

| Other Race, Non-Hispanic | 0.68 (0.54, 0.86) | .001 | 0.76 (0.57, 1.01) | .058 |

| White, Non-Hispanic c | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||

| Education Level | n = 31,057 | |||

| No High School | 2.00 (1.74, 2.29) | < .001 | 1.44 (1.21, 1.71) | < .001 |

| High School/GED | 1.89 (1.67, 2.16) | < .001 | 1.47 (1.26, 1.71) | < .001 |

| Some College/Associate’s | 2.00 (1.75, 2.28) | < .001 | 1.52 (1.33, 1.74) | < .001 |

| Bachelor’s or Higher c | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||

| Married/Living with Partner | n = 31,057 | |||

| Yes | 0.42 (0.38, 0.46) | < .001 | 0.46 (0.41, 0.52) | < .001 |

| No c | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||

| Any Past-Year Binge Drinking at Least Once a Month (Final Multivariable Model D4, n = 20,252) | ||||

| Sexual Identity | n = 22,663 | |||

| Heterosexualc | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||

| Gay/Lesbian | 2.12 (1.50, 3.00) | < .001 | 1.06 (0.51, 2.19) | .881 |

| Bisexual | 2.17 (1.77, 2.65) | < .001 | 1.09 (0.83, 1.42) | .546 |

| Sexual Attraction | n = 23,012 | |||

| Only to Males c | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||

| Only to Females | 2.41 (1.58, 3.67) | < .001 | 1.92 (0.90, 4.11) | .093 |

| To Both | 1.93 (1.70, 2.20) | < .001 | 1.44 (1.20, 1.71) | < .001 |

| Not Sure | 2.50 (1.51, 4.13) | < .001 | 1.71 (0.73, 4.00) | .214 |

| Sexual Behavior, Past Year | n = 20,569 | |||

| Only Males c | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||

| Only Females | 1.79 (1.10, 2.93) | .020 | 0.82 (0.34, 1.95) | .649 |

| Both | 3.60 (2.87, 4.52) | < .001 | 2.03 (1.54, 2.66) | < .001 |

| No Sex Partners | 0.61 (0.42, 0.88) | .008 | 0.44 (0.30, 0.66) | < .001 |

| Survey Cycle | n = 23,061 | |||

| 2002c | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||

| 2006-2010 | 1.01 (0.86, 1.17) | 0.94 | 1.04 (0.89, 1.21) | .622 |

| 2011-2015 | 0.70 (0.60, 0.82) | < .001 | 0.69 (0.59, 0.80) | < .001 |

| 0.70 (0.60, 0.82) n = 23,061 | ||||

| Age (continuous) | 0.96 (0.95, 0.96) | < .001 | 0.97 (0.96, 0.97) | < .001 |

| Race & Ethnicity | n = 23,061 | |||

| Hispanic, Any Race | 0.88 (0.76, 1.03) | .108 | 0.87 (0.74, 1.03) | .103 |

| Black, Non-Hispanic | 0.03 (0.72, 0.96) | .013 | 0.64 (0.54, 0.76) | < .001 |

| Other Race, Non-Hispanic | 0.8 (0.54, 0.87) | .002 | 0.70 (0.53, 0.92) | .010 |

| White, Non-Hispanic c | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||

| Education Level | n = 23,061 | |||

| No High School | 1.71 (1.42, 2.05) | < .001 | 1.10 (0.88, 1.38) | .387 |

| High School/GED | 1.93 (1.62, 2.30) | < .001 | 1.51 (1.25, 1.83) | < .001 |

| Some College/Associate’s | 1.82 (1.54, 2.14) | < .001 | 1.42 (1.20, 1.67) | < .001 |

| Bachelor’s or Higher c | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||

| Married/Living with Partner | n = 23,061 | |||

| Yes | 0.49 (0.43, 0.54) | < .001 | 0.49 (0.42, 0.56) | < .001 |

| No c | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||

All final multivariable models adjusted for age, race/ethnicity, education level, marital/cohabitation status, and survey cycle.

Sexual risk behavior defined as: any self-reported past-year transactional sex with male partners, any sex with male partners with high HIV risk (i.e., HIV-positive males, males who use injection drugs, males who had sex with males, or males who had other concurrent partners of any sex), any sex with five or more male partners, or any condomless penile-vaginal intercourse with male partners.

Reference category

Excluded due to inapplicability or small sample size.

Table 5.

Trends in Health Disparities among Sexual Minority Women in the National Survey of Family Growth, 2002-2015, Females Aged 15-44; Interactions between Sexual Orientation Components and Survey Cycles in Logistic Regression Models D1-D4

| Interactions | AOR (95% CI) | p |

|---|---|---|

| Model D1 - Past-Year STI/HIV-Related Sexual Risk Behaviors a | ||

| Sexual Identity by Survey Cycle | ||

| Heterosexual by 2002 b | 1.00 | |

| Lesbian by 2006-2010 | 0.56 (0.07, 4.39) | .581 |

| Bisexual by 2006-2010 | 0.40 (0.14, 1.09) | .074 |

| Lesbian by 2011-2015 | 0.25 (0.04, 1.61) | .145 |

| Bisexual by 2011-2015 | 0.63 (0.24, 1.64) | .340 |

| Sexual Attraction by Survey Cycle | ||

| Only to Males by 2002 b | 1.00 | |

| Only to Females by 2006-2010 | 2.65 (0.19, 37.39) | .472 |

| To Both by 2006-2010 | 2.02 (1.31, 3.12) | .002 |

| Not Sure by 2006-2010 | 0.49 (0.07, 3.56) | .478 |

| Only to Females by 2011-2015 | 1.80 (0.16, 20.62) | .638 |

| To Both by 2011-2015 | 1.27 (0.82, 1.97) | .295 |

| Not Sure by 2011-2015 | 1.80 (0.28, 11.68) | .537 |

| Past-Year Sexual Behavior by Survey Cycle | ||

| Only Males by 2002 b | 1.00 | |

| Both by 2006-2010 | 0.53 (0.21, 1.34) | .180 |

| Both by 2011-2015 | 0.76 (0.32, 1.79) | .527 |

| Model D2 - Received Medication for STIs in the Past Year | ||

| Sexual Identity by Survey Cycle | ||

| Heterosexual by 2002 b | 1.00 | |

| Bisexual by 2006-2010 | 1.33 (0.41, 4.31) | .638 |

| Bisexual by 2011-2015 | 0.97 (0.31, 3.05) | .954 |

| Sexual Attraction by Survey Cycle | ||

| Only to Males by 2002 b | 1.00 | |

| To Both by 2006-2010 | 1.44 (0.77, 2.70) | .257 |

| Not Sure by 2006-2010 | 0.30 (0.06, 1.43) | .133 |

| To Both by 2011-2015 | 1.01 (0.53, 1.93) | .966 |

| Not Sure by 2011-2015 | 0.46 (0.11, 1.98) | .297 |

| Past-Year Sexual Behavior by Survey Cycle | ||

| Only Males by 2002 b | 1.00 | |

| Both by 2006-2010 | 0.79 (0.26, 2.42) | .687 |

| No Sex Partners by 2006-2010 | 0.60 (0.20, 1.74) | .346 |

| Both by 2011-2015 | 1.22 (0.44, 3.39) | .700 |

| No Sex Partners by 2011-2015 | 0.84 (0.23, 3.10) | .798 |

| Model D3 - Any Past-Year Recreational Drug Use | ||

| Sexual Identity by Survey Cycle | ||

| Heterosexual by 2002 b | 1.00 | |

| Lesbian by 2006-2010 | 3.60 (1.16, 11.17) | .028 |

| Bisexual by 2006-2010 | 1.40 (0.81, 2.45) | .232 |

| Lesbian by 2011-2015 | 1.89 (0.61, 5.87) | .269 |

| Bisexual by 2011-2015 | 2.22 (1.27, 3.87) | .005 |

| Sexual Attraction by Survey Cycle | ||

| Only to Males by 2002 b | 1.00 | |

| Only to Females by 2006-2010 | 0.67 (0.18, 2.48) | .554 |

| To Both by 2006-2010 | 1.17 (0.83, 1.65) | .372 |

| Not Sure by 2006-2010 | 0.29 (0.06, 1.44) | .133 |

| Only to Females by 2011-2015 | 1.76 (0.48, 6.40) | .393 |

| To Both by 2011-2015 | 1.05 (0.75, 1.46) | .788 |

| Not Sure by 2011-2015 | 0.47 (0.12, 1.88) | .288 |

| Past-Year Sexual Behavior by Survey Cycle | ||

| Only Males by 2002 b | 1.00 | |

| Only Females by 2006-2010 | 0.73 (0.24, 2.26) | .592 |

| Both by 2006-2010 | 0.53 (0.28, 1.00) | .052 |

| No Sex Partners by 2006-2010 | 0.80 (0.46, 1.39) | .420 |

| Only Females by 2011-2015 | 0.31 (0.10, 0.95) | .042 |

| Both by 2011-2015 | 0.46 (0.25, 0.85) | .015 |

| No Sex Partners by 2011-2015 | 1.19 (0.62, 2.27) | .604 |

| Model D4 - Any Past-Year Binge Drinking at Least Once a Month | ||

| Sexual Identity by Survey Cycle | ||

| Heterosexual by 2002 b | 1.00 | |

| Lesbian by 2006-2010 | 1.25 (0.30, 5.25) | .761 |

| Bisexual by 2006-2010 | 0.83 (0.46, 1.51) | .546 |

| Lesbian by 2011-2015 | 0.30 (0.06, 1.61) | .160 |

| Bisexual by 2011-2015 | 1.15 (0.61, 2.15) | .670 |

| Sexual Attraction by Survey Cycle | ||

| Only to Males by 2002 b | 1.00 | |

| Only to Females by 2006-2010 | 0.59 (0.11, 3.13) | .532 |

| To Both by 2006-2010 | 1.12 (0.76, 1.63) | .568 |

| Not Sure by 2006-2010 | 0.32 (0.04, 2.57) | .287 |

| Only to Females by 2011-2015 | 0.66 (0.11, 4.02) | .649 |

| To Both by 2011-2015 | 1.08 (0.70, 1.66) | .741 |

| Not Sure by 2011-2015 | 0.37 (0.06, 2.43) | .300 |

| Past-Year Sexual Behavior by Survey Cycle | ||

| Only Males by 2002 b | 1.00 | |

| Only Females by 2006-2010 | 1.67 (0.46, 5.99) | .435 |

| Both by 2006-2010 | 1.04 (0.53, 2.05) | .908 |

| No Sex Partners by 2006-2010 | 0.80 (0.35, 1.84) | .600 |

| Only Females by 2011-2015 | 6.40 (1.29, 31.83) | .024 |

| Both by 2011-2015 | 0.84 (0.43, 1.62) | .598 |

| No Sex Partners by 2011-2015 | 0.58 (0.21, 1.57) | .287 |

Sexual risk behavior defined as: any self-reported past-year transactional sex with male partners, any sex with male partners with high HIV risk (i.e., HIV-positive males, males who use injection drugs, males who had sex with males, or males who had other concurrent partners of any sex), any sex with five or more male partners, or any condomless penile-vaginal intercourse with male partners.

Reference category

Table 6.

Final Multivariable Models (D1, D3, D4) Stratified by National Survey of Family Growth Survey Cycle, Females Aged 15-44

| 2002 (n = 5,126) | 2006-2010 (n = 8,776) | 2011-2015 (n =8,143) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AOR (95% CI) | p | AOR (95% CI) | p | AOR (95% CI) | p | |

| Past-Year STI/HIV-Related Sexual Risk Behaviors,a Stratified Model D1 | ||||||

| Sexual Identity | ||||||

| Heterosexual b | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | |||

| Gay/Lesbian | 1.04 (0.24, 4.54) | .233 | 0.63 (0.14, 2.75) | .537 | 0.27 (0.09, 0.84) | .024 |

| Bisexual | 1.69 (0.70, 4.06) | .244 | 0.70 (0.41, 1.19) | .192 | 1.17 (0.76, 1.82) | .474 |

| Sexual Attraction | ||||||

| Only to Males b | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | |||

| Only to Females | 0.29 (0.04, 1.89)) | .194 | 0.78 (0.12, 5.19) | .793 | 0.52 (0.11, 2.38) | .395 |

| To Both | 0.90 (0.65, 1.25) | .531 | 1.92 (1.43, 2.57) | < .001 | 1.18 (0.87, 1.61) | .285 |

| Not Sure | 1.18 (0.30, 4.63) | .817 | 0.58 (0.13, 2.560 | .470 | 2.22 (0.59, 8.32) | .238 |

| Sexual Behavior, Past Year | ||||||

| Only Males b | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | |||

| Only Females | c | -- | c | -- | c | -- |

| Both | 2.31 (1.08, 4.95) | .032 | 1.31 (0.75, 2.27) | .343 | 1.99 (1.30, 3.07) | .002 |

| No Sex Partners | c | -- | c | -- | c | -- |

| Age (continuous) | 1.02 (1.01, 1.04) | .012 | 1.04 (1.03, 1.05) | < .001 | 1.04 (1.02, 1.05) | < .001 |

| Race & Ethnicity | ||||||

| Hispanic, Any Race | 0.92 (0.69, 1.24) | .594 | 0.93 (0.73, 1.18) | .558 | 0.77 (0.61, 0.97) | .028 |

| Black, Non-Hispanic | 1.03 (0.75, 1.40) | .866 | 0.92 (0.71, 1.19) | .528 | 0.90 (0.73, 1.12) | .355 |

| Other Race, Non-Hispanic | 0.84 (0.57, 1.23) | .366 | 0.57 (0.38, 0.86) | .007 | 0.74 (0.52, 1.04) | .085 |

| White, Non-Hispanic b | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | |||

| Education Level | ||||||

| No High School | 1.39 (0.95, 2.03) | .087 | 1.84 (1.44, 2.34) | < .001 | 1.26 (0.98, 1.62) | .067 |

| High School/GED | 2.26 (1.60, 3.21) | < .001 | 1.62 (1.29, 2.04) | < .001 | 1.59 (1.20, 2.10) | .001 |

| Some College/Associate’s | 1.30 (0.99, 1.72) | .062 | 1.31 (1.05, 1.63) | .015 | 1.52 (1.24, 1.89) | < .001 |

| Bachelor’s or Higher b | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | |||

| Married/Living with Partner | ||||||

| Yes | 1.73 (1.34, 2.25) | < .001 | 2.26 (1.88, 2.72) | < .001 | 2.51 (2.08, 3.03) | < .001 |

| No b | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | |||

| 2002 (n = 6,374) | 2006-2010 (n = 10,408) | 2011-2015 (n = 9,110) | ||||

| AOR (95% CI) | p | AOR (95% CI) | p | AOR (95% CI) | p | |

| Sexual Identity | ||||||

| Heterosexual b | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | |||

| Gay/Lesbian | 0.38 (0.18, 0.81) | .126 | 1.45 (0.64, 1.34) | .375 | 0.77 (0.34, 1.77) | .537 |

| Bisexual | 0.62 (0.39, 0.98) | .041 | 0.96 (0.69, 1.35) | .807 | 1.52 (1.08, 2.14) | .017 |

| Sexual Attraction | ||||||

| Only to Males b | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | |||

| Only to Females | 3.00 (1.17, 7.08) | .022 | 1.88 (0.75, 4.71) | .175 | 4.71 (1.88, 11.80) | .001 |

| To Both | 2.74 (2.09, 3.61) | < .001 | 3.16 (2.54, 3.93) | < .001 | 2.78 (2.25, 3.44) | < .001 |

| Not Sure | 4.05 (1.09, 15.14) | .037 | 1.17 (0.45, 3.03) | .744 | 2.03 (1.06, 3.87) | .033 |

| Sexual Behavior, Past Year | ||||||

| Only Males b | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | |||

| Only Females | 0.93 (0.36, 2.40) | .885 | 0.69 (0.35, 1.35) | .275 | 0.33 (0.17, 0.63) | .001 |

| Both | 3.91 (2.39, 6.40) | < .001 | 2.15 (1.44, 3.20) | < .001 | 1.81 (1.22, 2.69) | .003 |

| No Sex Partners | 0.39 (0.26, 0.60) | < .001 | 0.31 (0.20, 0.47) | < .001 | 0.54 (0.31, 0.94) | .028 |

| Age (continuous) | 0.94 (0.93, 0.96) | < .001 | 0.96 (0.95, 0.97) | < .001 | 0.93 (0.92, 0.94) | < .001 |

| Race & Ethnicity | ||||||

| Hispanic, Any Race | 0.47 (0.36, 0.63) | < .001 | 0.48 (0.38, 0.60) | < .001 | 0.67 (0.54, 0.83) | < .001 |

| Black, Non-Hispanic | 0.62 (0.49, 0.77) | < .001 | 0.74 (0.59, 0.94) | .013 | 0.91 (0.76, 1.09) | .316 |

| Other Race, Non-Hispanic | 1.01 (0.51, 2.01) | .976 | 0.85 (0.53, 1.36) | .492 | 0.60 (0.42, 0.85) | .004 |

| White, Non-Hispanic b | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | |||

| Education Level | ||||||

| No High School | 1.90 (1.33, 2.72) | .001 | 1.52 (1.16, 2.00) | .003 | 1.14 (0.86, 1.51) | .363 |

| High School/GED | 1.85 (1.39, 2.46) | < .001 | 1.33 (1.04, 1.70) | .022 | 1.39 (1.08, 1.79) | .002 |

| Some College/Associate’s | 1.61 (1.22, 2.12) | .001 | 1.21 (0.98, 1.50) | .071 | 1.67 (1.34, 2.07) | < .001 |

| Bachelor’s or Higher b | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | |||

| Married/Living with Partner | ||||||

| Yes | 0.40 (0.31, 0.52) | < .001 | 0.43 (0.36, 0.52) | < .001 | 0.52 (0.43, 0.63) | < .001 |

| No b | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | |||

| 2002 (n = 4,840) | 2006-2010 (n = 8,163) | 2011-2015 (n = 7,249) | ||||

| AOR (95% CI) | p | AOR (95% CI) | p | AOR (95% CI) | p | |

| Sexual Identity | ||||||

| Heterosexual b | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | |||

| Gay/Lesbian | 1.59 (0.76, 3.34) | .217 | 1.85 (0.51, 6.69) | .350 | 0.44 (0.10, 1.93) | .278 |

| Bisexual | 1.01 (0.64, 1.58) | .983 | 0.88 (0.59, 1.29) | .503 | 1.23 (0.81, 1.85) | .336 |

| Sexual Attraction | ||||||

| Only to Males b | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | |||

| Only to Females | 2.82 (0.80, 9.97) | .108 | 1.88 (0.53, 6.68) | .329 | 2.14 (0.54, 8.42) | .278 |

| To Both | 1.26 (0.92, 1.71) | .153 | 1.43 (1.13, 1.81) | .003 | 1.48 (1.08, 2.02) | .014 |

| Not Sure | 3.09 (0.81, 11.82) | .099 | 1.34 (0.27, 6.62) | .720 | 1.50 (0.48, 4.67) | .481 |

| Sexual Behavior, Past Year | ||||||

| Only Males b | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | |||

| Only Females | 0.29 (0.13, 0.64) | .002 | 0.49 (0.17, 1.39) | .179 | 1.99 (0.52, 7.68) | .315 |

| Both | 2.02 (1.21, 3.37) | .007 | 2.32 (1.48, 3.64) | < .001 | 1.92 (1.25, 2.97) | .003 |

| No Sex Partners | 0.53 (0.28, 1.00) | .048 | 0.45 (0.25, 0.79) | .006 | 0.34 (0.15, 0.75) | .008 |

| Age (continuous) | 0.96 (0.95, 0.98) | < .001 | 0.96 (0.94, 0.97) | < .001 | 0.98 (0.96, 0.99) | .003 |

| Race & Ethnicity | ||||||

| Hispanic, Any Race | 0.75 (0.55, 1.01) | .057 | 0.69 (0.51, 0.93) | .013 | 1.07 (0.83, 1.39) | .593 |

| Black, Non-Hispanic | 0.52 (0.40, 0.69) | < .001 | 0.52 (0.39, 0.68) | < .001 | 0.83 (0.62, 1.10) | .197 |

| Other Race, Non-Hispanic | 0.81 (0.49, 1.35) | .422 | 0.47 (0.30, 0.73) | .001 | 0.83 (0.56, 1.23) | .352 |

| White, Non-Hispanic b | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | |||

| Education Level | ||||||

| No High School | 1.35 (0.91, 2.00) | .140 | 0.95 (0.70, 1.27) | .714 | 1.04 (0.67, 1.62) | .851 |

| High School/GED | 1.61 (1.12, 2.33) | .011 | 1.32 (1.01, 1.72) | .043 | 1.63 (1.18, 2.26) | .004 |

| Some College/Associate’s | 1.54 (1.14, 2.08) | .005 | 1.26 (1.01, 1.58) | .039 | 1.46 (1.09, 1.96) | .012 |

| Bachelor’s or Higher b | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | |||

| Married/Living with Partner | ||||||

| Yes | 0.32 (0.25, 0.41) | < .001 | 0.47 (0.38, 0.59) | < .001 | 0.56 (0.44, 0.72) | < .001 |

| No b | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | |||

Sexual risk behavior defined as: any self-reported past-year transactional sex with male partners, any sex with male partners with high HIV risk (i.e., HIV-positive males, males who use injection drugs, males who had sex with males, or males who had other concurrent partners of any sex), any sex with five or more male partners, or any condomless penile-vaginal intercourse with male partners.

Reference category

Excluded from analyses due to inapplicability or small sample size.

Past-Year Sexual Behavior Related to STI/HIV Risk

This set of results describes findings from logistic regression models with past-year STI/HIV sexual risk behaviors as the main outcome. We first examined sexual risk behaviors by sexual orientation indicators in unadjusted models, and subsequently in three separate models (adjusted for age, race/ethnicity, education level, survey cycle, and marital/cohabitation status) by sexual identity (Model A1), attraction (Model B1), and behavior (Model C1). In Model D1, we then adjusted for all three sexual orientation indicators simultaneously. Below, we report on unadjusted models and the combined Model D1; see Supplemental tables for Models A1-C1.

In unadjusted logistic regression models (Table 4), women reporting women attracted to males and females (OR: 1.19, p = .030), as well as both male and female partners within the past year (OR: 1.37, p = .024) had significantly greater odds of past-year sexual risk behavior compared to women who only had male partners, while women reporting attraction only to females had 62% decreased odds of sexual risk behavior (OR: 0.38, p = .033). Sexual minority identity was not a significant predictor of elevated sexual risk behavior in unadjusted models (Table 4).

In Model D1, which included all three indicators of sexual orientation simultaneously, sexual identity remained non-significant, and attraction to both males and females (AOR: 1.26, p = .016) as well as having had partners of both sexes in the past year (AOR: 1.75, p = < .001) remained significantly associated with greater odds of sexual risk behavior (Table 4).

Next, we added interaction terms between each sexual orientation measure and survey cycle to Model D1. There was significant interaction between bisexual identity and survey cycle 2006-2010 (p = .074) and between attraction to both males and females and cycle 2006-2010 (p = .002) (Table 5). Because we found significant interactions, we stratified Model D1 by survey cycle to examine effect modification (Table 6).

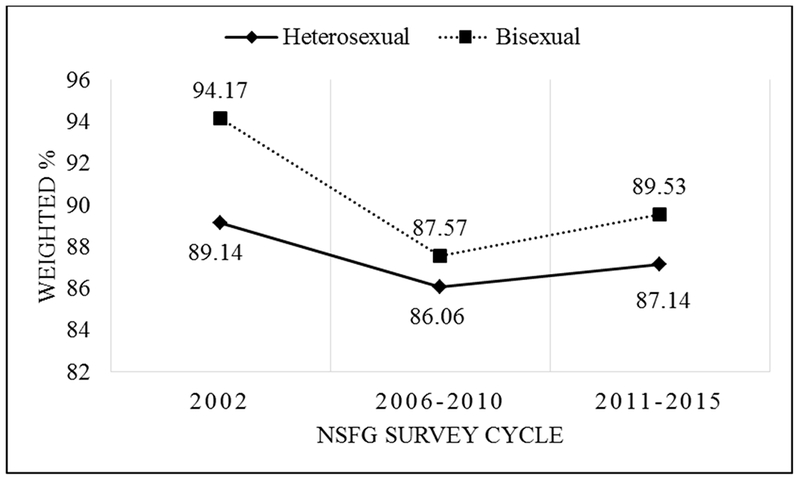

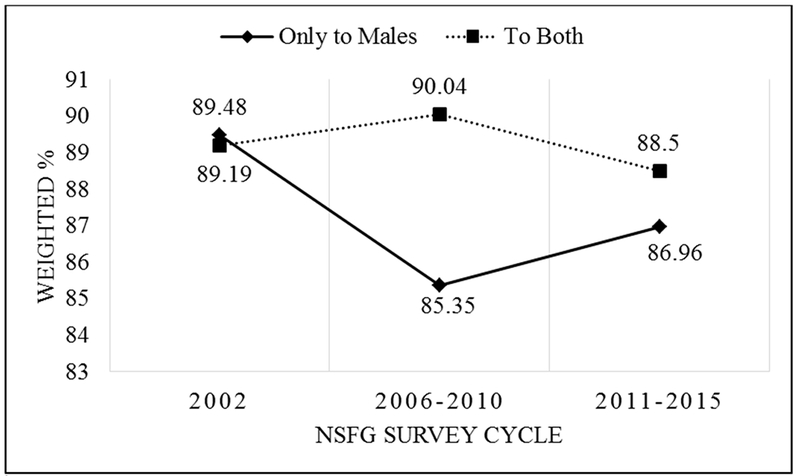

In stratified models (see Table 6), bisexual compared to heterosexual identity was associated with 1.69 times the odds of sexual risk behavior (p = .244) in 2002 but a 30% decreased odds in 2006-2010 (p = .192). An odds ratio less than 1 for the interaction of bisexual identity and survey cycle 2006-2010 (AOR: 0.40; see Table 5) indicates that the disparity in sexual risk behavior between women who identified as bisexual and heterosexual narrowed from the 2002 to the 2006-2010 survey cycles (Homma et al., 2016). Reporting attraction to both males and females was associated with a non-significant decreased odds of sexual risk behavior in 2002 (AOR: 0.90, p = .531) but a significantly increased odds of risk behavior in the 2006-2010 cycle (AOR: 1.92, p < .001). An odds ratio greater than 1 for the interaction of attraction to both males and females and survey cycle 2006-2010 (AOR: 2.02; see Table 5) indicates that the disparity in sexual risk behavior between women attracted to both males and females compared to those exclusively attracted to males widened from 2002 to 2006-2010 (Homma et al., 2016). Figures 1 and 2 visually depict changes in the proportion of these groups that engaged in sexual risk behaviors, without adjustment for age, race/ethnicity, education level, or marital status.

Figure 1.

STI/HIV-Related Sexual Risk Behavior by Sexual Identity, National Survey of Family Growth, 2002-2015, Females Aged 15-44

Figure 2.

STI/HIV-Related Sexual Risk Behavior by Sexual Attraction, National Survey of Family Growth, 2002-2015, Females Aged 15-44

Past-Year STI Treatment

Here, we report on findings from logistic regression models with past-year STI treatment as the main outcome. We first examined STI treatment by sexual orientation indicators in unadjusted models, and subsequently in three separate models for each sexual orientation indicator (Model A2: by sexual identity; Model B2: by sexual attraction; Model C2: by sexual behavior), adjusted for age, race/ethnicity, education level, survey cycle, and marital/cohabitation status. In Model D2, we then adjusted for all three sexual orientation indicators simultaneously. Below, we report on unadjusted models and the combined Model D2; see Supplemental tables for Models A2-C2.

In unadjusted models (see Table 4), non-monosexuality in terms of identity, behavior, and attraction were each associated with greater odds of STI treatment as compared to exclusive heterosexuality (bisexual identity OR: 1.91, p < .001; attraction to both males and females OR: 1.92,p < .001; sex with both male and female partners in the past year OR: 3.06, p < .001) (Table 4). In the model that combined all three indicators of sexual orientation (Model D2, Table 4), bisexual identity was no longer significantly associated with STI treatment in the past year, but being attracted to and having both male and female partners remained significant (AOR: AOR: 1.58, p < .001; 1.77, p = .002 respectively) (Table 4).

Next, we added interaction terms between each sexual orientation measure and survey cycle to Model D2. Since none of the interactions were significant, we did not stratify Model D2 by survey cycle.

Past-Year Drug Use

Next, we report on findings from logistic regressions with past-year drug use as the main outcome. We first examined drug use by sexual orientation indicators in unadjusted models, and subsequently in three separate models for each sexual orientation component (Model A3: by sexual identity; Model B3: by sexual attraction; Model C3: by sexual behavior) adjusted for age, race/ethnicity, education level, survey cycle, and marital/cohabitation status. In Model D3, we then adjusted for all three sexual orientation indicators simultaneously. Below, we report on unadjusted models and the combined Model D3; see Supplemental tables for Models A3-C3.

In unadjusted logistic regression models (see Table 4), sexual minority identity (lesbian OR: 2.75, p < .001; bisexual OR: 4.22, p < .001), attraction (only attracted to females OR: 3.64, p < .001; attracted to both males and females OR: 3.97, p < .001), and behavior (exclusively female past-year partners OR: 1.77, p = .001, both male and female past-year partners OR: 6.58, p < .001) were all significantly associated with increased odds of self-reported past-year drug use compared to sexual majority women. For each measure of sexual orientation, women with self-reported non-monosexual identity, attraction, and behavior had the greatest odds of past-year drug use compared to other groups.

In Model D3, which adjusted for all three measures of sexual orientation, sexual minority identity was no longer a significant predictor of drug use, while attraction exclusively to females (AOR: 3.11, p < .001) and attraction to both males and females (AOR: 2.91, p < .001), as well as having both male and female past-year sex partners (AOR: 2.21, p < .001) remained significantly associated with higher odds of drug use. Having exclusively female past-year sex partners, however, was associated with lower odds of drug use in this adjusted model, predicting a 48% decreased odds of past-year use compared to those with exclusively male past-year partners (p = .004) (Table 4).

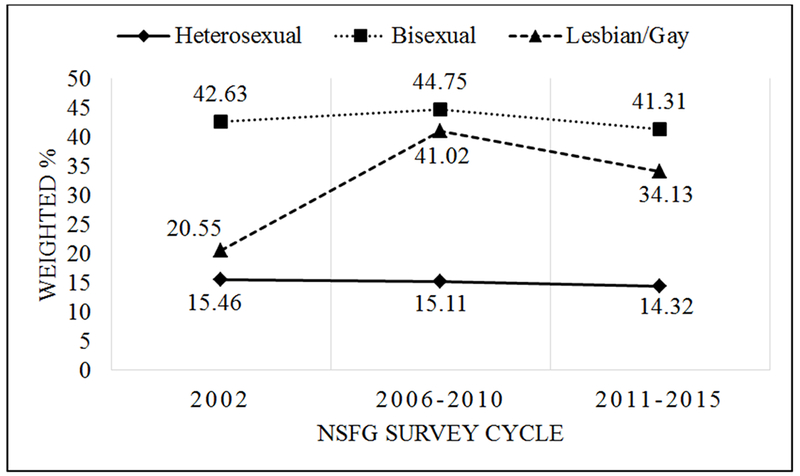

Next, we added interaction terms between each sexual orientation measure and survey cycle to Model D3 (see Table 5). Because we found significant interaction between lesbian identity and survey cycle 2006-2010 (p = .028); bisexual identity and 2011-2015 (p = .005); having exclusively female past-year partners and cycle 2011-2015 (p = .042); having both male and female past-year partners in cycles 2010-2006 (p = .052) and 2011-2015 (p = .015) (Table 5), we then stratified Model D3 by survey cycle.

Lesbian identity predicted non-significant decreased odds of drug use in 2002 (AOR: 0.38, p = .126) but increased odds in 2006-2010 (AOR: 1.45, p = .375). A similar pattern was observed for bisexually identified women: Bisexual identity was associated with significantly decreased odds of drug use in 2002 (AOR: 0.62, p = .041) but increased odds in 2011-2015 (AOR: 1.52, p = .017). An odds ratio greater than 1 for interactions between lesbian identity and survey cycle 2006-2010 (AOR: 3.60) and for the interaction of bisexual identity and survey cycle 2011-2015 (AOR: 2.22, see Table 5 for interactions) demonstrates that the disparities in drug use among lesbian vs. heterosexual women widened from 2002 to 2006-2010, and among bisexual vs. heterosexual women from 2002 to 2011-2015 (Homma et al., 2016).

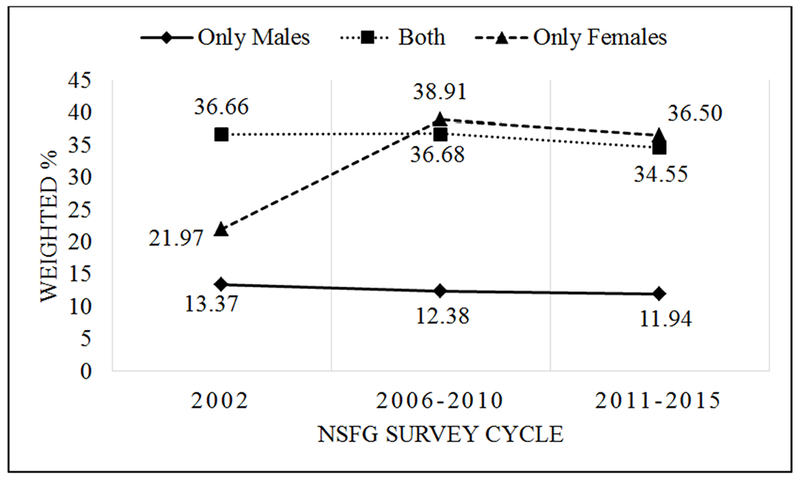

Having both male and female past-year sex partners was associated with significantly higher odds of past-year drug use relative to women with exclusively male past-year partners in all three survey cycles, but with the strength of the association decreasing over time (2002 AOR: 3.91, p < .001; 2006-2010 AOR: 2.15, p < .001; 2011-2015 AOR: 1.81, p = .003) (Table 6). Having exclusively female partners was associated with decreasing odds of drug use compared to women with exclusively male partners in each survey cycle, but the association was only significant in the 2011-2015 cycle (2002 AOR: 0.93 p = .885; 2006-2010 AOR: 0.69, p = .275; 2011-2015 AOR: 0.33, p = .001) (Table 6). Odds ratios less than 1 for the interactions between sex with male and female partners and survey cycles 2006-2010 (AOR: 0.53) and 2011-2015 (AOR: 0.46), and between exclusively female sex partners and 2011-2015 (AOR: 0.31; see Table 5 for interactions) indicate narrowing disparities in drug use among sexual minority women compared to women with exclusively male partners (Homma et al., 2016). See Figs. 3 and 4 for visual representations of these changing trends without adjustment for age, race/ethnicity, education level, or marital status.

Figure 3.

Recreational Drug Use by Sexual Identity, National Survey of Family Growth, 2002-2015, Females Aged 15-44

Figure 4.

Drug Use by Sexual Behavior, National Survey of Family Growth, 2002-2015, Females Aged 15-44

Past-Year Binge Drinking Once a Month or More

Finally, we report on findings from logistic regression models with past-year binge drinking once a month or more as the main outcome. We first examined binge drinking by sexual orientation indicators in unadjusted models, and subsequently in three models adjusted for age, race/ethnicity, education level, survey cycle, and marital/cohabitation status: Model A4 examined past-year binge drinking by sexual identity, Model B4 by sexual attraction, and Model C4 by sexual behavior. In Model D4, we then adjusted for all three sexual orientation indicators simultaneously. Below, we report on unadjusted models and the combined Model D4; see Supplemental tables for Models A4-C4.

In the unadjusted logistic regression models (see Table 4) examining self-reported past-year binge drinking at least once a month, women reporting exclusive attraction to females had the greatest odds of past-year binge drinking when compared to women who reported exclusive attraction to males (OR: 2.41, p < .001; attraction to both OR: 1.93, p < .001); however, women with a bisexual identity (OR: 2.17, p < .001; lesbian identity OR: 2.12, p < .001) and with both male and female past-year partners (OR: 3.60,p < .001; exclusively female partners OR: 1.79,p = .020) had the highest odds of past-year binge drinking compared to heterosexually identified women and women who only had sex with male partners in the past year.

In Model D4 that included all three measures of sexual orientation, sexual minority identity was no longer significantly associated with self-reported binge drinking in the past year. Attraction to both males and females (AOR: 1.44, p < .001) and having had both male and female past-year partners (AOR: 2.03,p < .001) remained significant predictors of binge drinking compared to those with exclusively male past-year male partners.

When we added interaction terms between each sexual orientation measure and survey cycle to Model D4, we found significant interaction between having exclusively female past-year partners and survey cycle 2011-2015 (p = .024, see Table 5). Having only female partners (versus only male partners) predicted decreased odds of drinking in 2002 (AOR: 0.29, p = .002) and 2006-2010 (AOR: 0.49, p = .179) but was associated with (non-significant) greater odds of binge drinking in 2011-2015 (AOR: 1.99, p = .315). An odds ratio greater than 1 (AOR: 6.40) for the interaction of exclusively female partners and survey cycle 2011-2015 (see Table 5) shows that the disparity in binge drinking compared to those with exclusively male partners widened from 2002 to 2011-2015 (Homma et al., 2016) (see Fig. 5).

Figure 5.

Binge Drinking by Sexual Behavior, National Survey of Family Growth, 2002-2015, Females Aged 15-44

Results with Non-Monosexual Women as the Reference Group

Given that non-monosexual women generally presented with the highest levels of risk behavior, we re-ran the final models (D1-D4) with bisexual identity, attracted to both males and females, and past-year sex with both males and females as reference groups to assess if differences between non-monosexual and monosexual women were significant. In most cases, we found that non-monosexual women, regardless of how sexual orientation was measured, had significantly higher odds of risk behavior compared to both monosexual sexual minority (e.g., lesbian identified or exclusively female partners) and sexual majority women (e.g., heterosexual identified or exclusively male partners). See Supplemental Table 5 for full details.

DISCUSSION

We examined three dimensions of sexual orientation—sexual identity, behavior, and attraction—across three survey cycles of the NSFG. Concurrently accounting for sexual identity behavior, and attraction allowed for exploration of which sexual orientation components are independently associated with each health behavior relative to sexual majority women. The results of this study echo previous research showing that sexual minority orientation is associated with elevated odds of risky health behaviors among women, and that sexual attraction and behavior emerged as stronger predictors of health disparities between sexual minority and sexual majority women than sexual identity (Brewster & Tillman, 2012; Goodenow et al., 2008).

Similar to existing literature, non-monosexual women generally had the greatest disparities relative to other groups. Health disparities for women identifying as bisexual seemed to be explained by attraction to and sex with both males and females, rather than having a bisexual identity in and of itself. We suggest three hypotheses for this finding. First, women who identify as bisexual may have greater access to supportive communities as bisexual identity becomes increasingly common in the U.S. (England, Mishel, & Caudillo, 2016). Social support may protect against the deleterious effects of minority stress (Hatzenbuehler, 2009) among bisexual women (MacKay, Robinson, Pinder, & Ross, 2017). For women who express attraction to or have sex with both men and women without assuming a bisexual or other non-monosexual (e.g., queer; pansexual) identity, however, community connection may not be as readily available. Second, the association between both-sex attractions, as well as both-sex sexual partners and health risk behaviors may also be a result of concealment of a bisexual or other non-monosexual identity in anticipation of rejection and/or discrimination (Paul, Smith, Mohr, & Ross, 2014), which has been linked to decreased social support (Pachankis, 2007). Coming out as bisexual can decrease internalized bisexual stigma (Paul et al., 2014), but women who express bisexual attractions and behaviors without assuming a bisexual or other non-monosexual identity may not experience the health benefits of coming out. Finally, “internalized monosexism” (e.g., internalizing stereotypes that non-monosexuality is a temporary identity or indicative of promiscuity) (Dyar et al., 2017) may also contribute to greater health disparities among women expressing non-monosexual attraction and behavior (Goodenow et al., 2008). For non-monosexual people who do not divulge a bisexual identity, internalized monosexism appears to be particularly heightened (Dyar et al., 2017).

Changing Health Disparity Trends Across NSFG Survey Cycles

In models stratified by NSFG survey cycle, we found variable trends in health disparities depending on how sexual orientation was measured. For example, disparities in sexual risk behavior between bisexually and heterosexually identified women narrowed from the 2002 to the 2006-2010 survey cycles, but disparities between women attracted to males and females and those attracted exclusively to males widened from 2002 to 2006-2010. In models with drug use as the outcome, disparities widened between bisexually and heterosexually identified women, but narrowed between women with both male and female partners and those with only male partners from 2006-2010 to 2011-2015. Thus, the measure of sexual orientation used to assess trends across survey cycles impacts depiction of health disparities between sexual minority and sexual majority women.

Although researchers may determine at the data analysis phase that not all indicators of sexual orientation are relevant to the research questions at hand, we recommend that each component be made available within national health surveys to allow for more robust analyses of sexual orientation data and to provide health researchers with more options to explore which elements of sexual orientation are associated with health disparities among sexual minorities (Wolff et al., 2017), particularly women expressing non-monosexuality. We also suggest that sexual minority health disparity studies explore correlations between each component of sexual orientation to determine whether different indicators of orientation are measuring different constructs and thus should be examined separately (Wolff et al., 2017).