Abstract

The direct, catalytic substitution of unactivated alcohols remains an undeveloped area of organic synthesis. Moreover, catalytic activation of this difficult electrophile with predictable stereo-outcomes presents an even more formidable challenge. Described herein is a simple iron-based catalyst system which provides the mild, direct conversion of secondary and tertiary alcohols to sulfonamides. Starting from enantioenriched alcohols, the intramolecular variant proceeds with stereoinversion to produce enantioenriched 2- and 2,2-subsituted pyrrolidines and indolines, without prior derivatization of the alcohol or solvolytic conditions.

Keywords: alcohol substitution, asymmetric synthesis, indoline, iron, sulfonamides

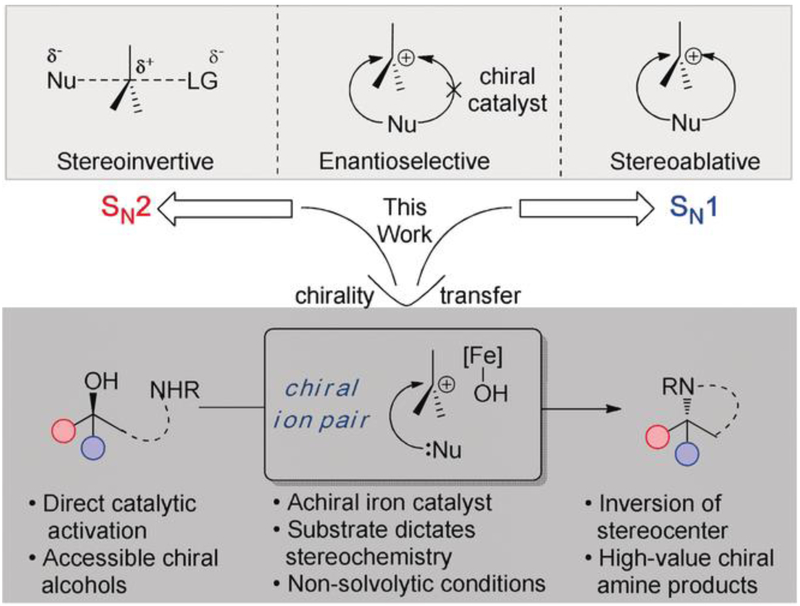

Graphical Abstract

Employing a simple iron catalyst is sufficient for the direct conversion of secondary and tertiary alcohols to sulfonamides. Starting from enantioenriched alcohols, the intramolecular variant pro ceeds with stereoinversion to produce enantioenriched 2- and 2,2-substituted pyrrolidines and indolines, without prior derivatization of the alcohol or solvolytic conditions.

The interconversion of functional groups represents an archetypal operation in organic synthesis. These transformations can leverage the reactivity of a common functional group to install a new, more valuable motif. Classic examples include the SN2 and SN1 reactions (Scheme 1). While the SN2 proceeds stereospecifically with inversion of configuration,[1] the SN1 reaction, owing to the carbocation intermediate, generally proceeds with loss of stereochemistry.[2] Chemists have gone to great lengths to control the facial selectivity of nucleophile attack on the carbocation through the use of enantioenriched catalysts.[3] Transferring the stereochemical information of the starting electrophile that undergoes an ionization event remains a challenge.[4] Herein, we demonstrate that secondary and tertiary alcohols can be used directly as electrophiles with inversion of stereochemistry when displaced with tethered sulfonamides.

Scheme 1.

An ion-pair approach to enantioselective substitution.

Due to their ubiquity and stability, aliphatic alcohols are attractive electrophiles for functional group interconversion. The 2018 ACS Green Chemical Institute Pharmaceutical Roundtable highlighted the activation of alcohols for nucleophilic substitution as a key reaction in need of development.[5] Conventional methods for alcohol substitution often involve converting the alcohol to a halide or pseudohalide before nucleophilic substitution or employ the Mitsunobu reaction.[6,7] Direct, catalytic activation of alcohols for substitution is an attractive approach to form carbon–heteroatom bonds because water is the only stoichiometric byproduct. One approach is the Lewis or Brønsted acid-promoted SN1 substitution[8] of benzylic,[9] allylic,[10] and propargylic[11] alcohols. While п-activated or tertiary alcohols can be substituted with a wide range of nucleophiles,[12] unactivated alcohols remain a significant challenge.[13] Recently, we reported an iron-catalyzed intramolecular Friedel–Crafts arylation of unactivated secondary alcohols that proceeds with chirality transfer.[14] We sought to translate this system into a general conceptual framework for the direct amination of alcohols.

In certain limited cases, enantioenriched secondary alcohols can be utilized directly to transfer chiral information to new carbon–heteroatom bonds. For example, Samec and coworkers used a Brønsted acid catalyst to control the facial approach of the nucleophile for a stereoinvertive dehydrative cyclization.[15] Inverting free tertiary alcohols for this type of substitution, however, remains problematic. Solvolysis represents the only successful approach to transfer the chirality of tertiary electrophiles to the substituted product.[16] Moreover, the starting alcohols must be activated as a nitrobenzoyl ester,[17] alkoxydiphenyl phosphine,[18] or trifluoroacetate[4] to permit ionization. While a substitution of an unactivated tertiary alcohol exists, in studies of a-tocopherol, this also proceeds under solvolytic conditions.[19] The direct substitution of unactivated tertiary alcohols with nitrogen nucleophiles would represent a major advance in this field; providing access to a-tertiary chiral amine products—an amine class that currently necessitates lengthy synthetic sequences.[20] Herein, we report an iron-catalyzed system capable of directly substituting aliphatic alcohols as well as the stereo-invertive, intramolecular substitution of chiral secondary and tertiary alcohols by sulfonamide nucleophiles.

To gain insight into the reactivity of unactivated alcohols in an amination reaction, we began our investigation by treating cyclohexanol with p-toluenesulfonamide in the presence of selected acid catalysts (see the Supporting Information). Iron(II) or iron(III) salts alone proved ineffective in this difficult transformation. Consistent with the enhanced Lewis acidity of iron(III) salts containing “non-coordinating” counterions,[14,21] the combination of iron(III) chloride with AgSbF6 in 1,2-dichloroethane at 80°C for 24 hours afforded the desired amination product in 78% yield (see the Supporting Information). Three equivalents of AgSbF6 relative to iron proved superior to fewer equivalents, consistent with the exchange of all three chlorides for hexafluoroantimonate ions. Brønsted acids, including HSbF6, produced low yield, thereby providing support for an iron-based Lewis acid as the primary activator of the alcohol. However, selected bases (for example, Cs2CO3, K2CO3, and 2,6-di-tert-butyl-4-methylpyridine) did measurably lower the yield, suggesting some background Brønsted acid catalysis (see the Supporting Information).

With suitable conditions for the amination of cyclohexanol 1b, we next evaluated the performance of the intermolecular reaction across a variety of aliphatic alcohols. We were pleased to find that cyclic and symmetric acyclic secondary alcohols resulted in the desired amination products in moderate-to-good yields (2a–f, Table 1). Unfortunately, 2-hexanol (1j) resulted in a 1:1 mixture of 2- and 3-substituted products 2j, suggesting a facile carbocation rearrangement.[22] To test whether the intermolecular reaction proceeds with stereoinversion, enantioenriched (R)-2-butanol (1i) was subjected to the reaction conditions and provided racemic product 2i, possibly due to background Brønsted acid catalysis. Reaction monitoring by GC/MS indicated the formation and consumption of alkene, suggesting an E1 elimination followed by hydroamination of the alkene as an alternative and competing pathway to the substitution.[23] In addition to p-toluenesulfonamide, p-nitrobenzenesulfonamide also functioned well as the nucleophile, providing an easily removable nosyl protecting group in product 2g, while methanesulfonamide provided 2h in 71% yield. Efforts to extend this methodology to other nitrogen nucleophiles such as carbamates, amides, anilines, and aliphatic amines were unsuccessful potentially owing to competitive iron coordination to nitrogen. Primary alcohols proved difficult. While phenethyl alcohol (1k) functions well in the reaction, likely through anchimeric assistance,[24] other primary alcohols

Table 1:

Substrate scope for the intermolecular alcohol substitution with sulfonamides.

|

Yields of isolated products.

4-Nitrobenzenesulfonamide nucleophile used.

Methanesulfonamide nucleophile used.

1:1 Mixture of 2- and 3-substituted products.

FeCl3 only.

resulted in low yields (data not shown). Conversely, tertiary alcohols were excellent substrates, affording the amination products in good (2l and 2m)-to-near quantitative yields (2n). Contrary to primary and secondary alcohols, tertiary alcohols worked better at lower temperature or without the use of AgSbF6.

While the intermolecular amination of secondary alcohols resulted in racemic products, we hypothesized that an intra-molecular amination of enantioenriched alcohols would proceed rapidly to provide access to stereodefined pyrroli-dines and indolines, a motif present in many natural products and bio-active molecules.[25] Current methods to set this difficult stereocenter[26] involve enantioselective hydroaminations,[27] asymmetric hydrogenation,[28] and kinetic resolutions,[29] all of which rely on chiral catalysts. Other approaches required the prefunctionalization of chiral alcohols.[30] We found that the intramolecular substitution of enantioenriched secondary alcohols proceeded with high yields and enantio-specificity, transferring chirality to the formed pyrrolidine ring (Table 2). The reactions did not proceed with Brønsted acids instead of iron and were not inhibited by exogenous bases, in contrast to the intermolecular variants.

Table 2:

Intramolecular stereoinvertive substitution of secondary alcohols.

|

Yields of isolated products. Enantiomeric excess determined by chiral HPLC analysis.

The scope of the intramolecular substitution of chiral secondary alcohol was explored by varying the alcohol sidechain. Simple chains such as methyl in 3a and n-propyl in 3b formed the 2-substituted pyrrolidine with excellent yield and 96% es (enantiospecificity). Alcohols with larger side-chains, such as 2-methylpropyl in 3c, performed better with complete chirality transfer to form 4c. The benzylic alcohol in 3d formed the desired pyrrolidine product 4d as a racemic mixture due to formation of the stabilized benzylic carbocation. Enantioenriched 2-substituted indolines were also accessible with this method. Once again, simple alkyl groups such as methyl in 3e and ethyl in 3f proved high yielding with high levels of enantiospecificity even on gram scale. The electronic properties of the nitrogen nucleophile could be modified with electron-donating or -withdrawing groups on the aniline without reducing the enantiospecificity of the reaction. The reaction tolerated remote functional groups. For example, the inclusion of a primary bromide in 3i or tosylate in 3j proceeded well to provide a synthetic handle for further functionalization. Furthermore, the tosyl group can be efficiently removed affording the deprotected indoline product without racemization (see the Supporting Information).[31] Extending this methodology to six-membered piperadine rings produced an inseparable mixture of six- and five-membered products-arising from a rapid carbocation rearrangement (see the Supporting Information).

Since the intramolecular substitution of secondary alcohols proceeded in high yields and enantiospecificity, we suspected that enantioenriched tertiary alcohols could be substituted through a non-racemic mechanism. We reasoned that the developing tertiary carbocation could be attacked from the face opposite of the departing alcohol, resulting in chirality transfer. To intercept a tertiary carbocation with minimal racemization under non-solvolytic conditions, the iron-ate/carbocation ion pair needs to be tightly associated to block one face of the carbocation (see Scheme 2b).[32] We reasoned that a solvent with lower dielectric constant combined with decreased reaction temperature would fortify the ion pair and favor stereoinversion. To our delight, decreasing the reaction temperature to –40 °C and switching the solvent to toluene produced the enantioenriched 2,2-disubstituted indoline products (Table 3). Indoline 6a with alkyl side chains was formed in 79% ee, transferring 89% of the chiral information from starting alcohol 5a. The electronic properties of the sulfonamide nucleophile could be altered by placing an electron-withdrawing or -donating group at the para position of the aniline ring. Attenuating the nucleophi licity with electron-withdrawing groups, such as CF3 in 5c or F in 5d, decreased both the yield and the enantiospecificity of the reaction. The more electron-rich nucleophile in 5e had little effect on the reaction. In addition to alkyl side chains, electron-rich aromatic rings (5 f and 5g) also proceeded with good es. Silyl-protected phenols were compatible with the reactions conditions. While the triisopropylsilyl (TIPS) group in 5h group proved stable to the reaction conditions, the tertbutyldimethyl silyl (TBS) group for 5i was partially deprotected over the course of the reaction. In all, Table 3 presents an expeditious route to 2,2-disubstituted indolines with useful ee and good yields—a previously challenging and labor-intensive synthetic endeavor.

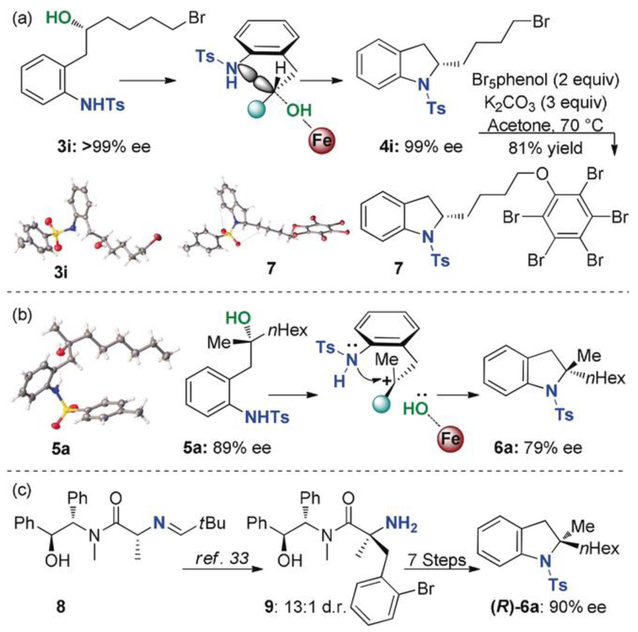

Scheme 2.

Stereochemical model and absolute configuration for the intramolecular substitution of (a) secondary alcohols (b) tertiary alcohols. (c) Absolute configuration determination for indoline product 6a by an asymmetric benzylation of d-alanine derivative 8.

Table 3:

Intramolecular stereoinvertive substitution of tertiary alcohols.

|

Yields of isolated products. Enantiomeric excess determined by chiral HPLC analysis.

Reaction run in (5:1) toluene:DCE.

Phenol of 5i is protected with TBS. Reaction yielded a mixture of TBS protected and deprotected phenol. Mixture converted to the 6i with TBAF (1 equiv).

To determine whether the reaction proceeds with inversion of stereochemistry, the absolute configuration of enantioenriched alcohol 3i and the resulting indoline ring 4i were assigned by X-ray crystallography (Scheme 2a). Alcohol 3icrystalized readily and was assigned the (R) configuration. Pentabromophenol-derived indoline 7, however, had the (S) configuration, thereby confirming that the intramolecular substitution of secondary alcohols proceeds with stereoinversion. For the intramolecular substitution of tertiary alcohols, our model predicts stereoinversion. The departing iron-hydroxide would block the front face of the carbocation favoring rapid attack of nitrogen from the opposite face (Scheme 2b). The stereochemistry of tertiary alcohol 5a was confirmed as (R) configuration by X-ray crystallography. However, since an X-ray-suitable crystal for indoline product 6a remains unrealized, an asymmetric benzylation of dalanine derivative 8 followed by a seven-step sequence produced (R)-6a (Scheme 2c and SI-4 in the Supporting Information),[33] a testament to the limitations of current methods to prepare a-tertiary chiral amines. Indoline product 6a was determined to be in the (S) configuration, thereby confirming the intramolecular substitution of tertiary alcohols also proceeds with stereoinversion.

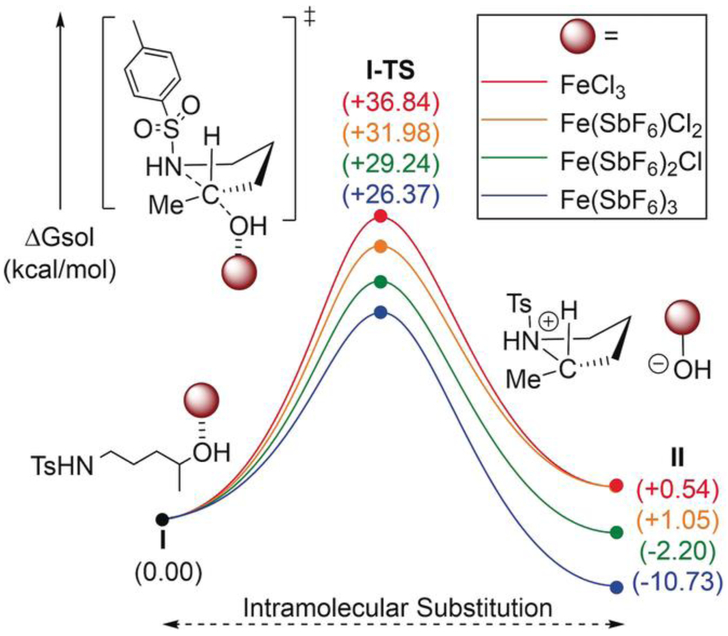

To help elucidate whether Fe(SbF6)3 is the active iron catalyst, we employed density functional theory calculations (Scheme 3 and Figures SI-2—SI-5 in the Supporting Information). We focused on the stereoinversion step for 3a with the alcohol bound to FeCl3, Fe(SbF6)Cl2, Fe(SbF6)2Cl, and Fe(SbF6)3. The lowest barrier for C–N bond formation (I-TS) was 26.4 kcalmol –1 with Fe(SbF6)3. This finding is consistent with our experimental data, where no reaction occurs in the absence of AgSbF6, and the best yields were obtained with three equivalents relative to Fe (see the Supporting Information). These calculations show that the residual reactivity observed with fewer than three equivalents of AgSbF6 is likely due to an equilibrium that includes Fe(SbF6)3—the relevant, active catalyst.

Scheme 3.

Computed free-energy diagram for the intramolecular substitution of 3a.

In conclusion, we have developed a mild and efficient iron-catalyzed substitution of unactivated alcohols with sulfonamide nucleophiles. This methodology allows efficient access to secondary and tertiary alkyl sulfonamides from readily available alcohols. Furthermore, the intramolecular variant of the reaction proceeds with inversion of stereo-chemistry. By employing the concept of tight ion pairing as a solution to cation facial selectivity, this method represents a rare example where secondary and even tertiary alcohols react with an achiral catalyst to transfer the chiral information to the products under non-solvolytic conditions. This method enables efficient access to enantioenriched 2,2-disubstiuted indoline products in far fewer steps than current technology allows. By rapidly intercepting ion pairs, we have leveraged an unconventional tactic to form the Csp3 N bond with predictable stereochemical outcomes.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge the Indiana University for partial support. We also acknowledge the NSF CAREER Award (CHE-1254783), Lilly Grantee Award, and Amgen Young Investigator Award. P.T.M. was supported by the Graduate Training Program in Quantitative and Chemical Biology (T32 GM109825). We also thank the Institute for Basic Science in Korea for financial support (IBS-R010-A1).

Footnotes

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Supporting information and the ORCID identification number(s) for the author(s) of this article can be found under: https://doi.org/10.1002/anie.201812894.

Contributor Information

Deyaa I. AbuSalim, Department of Chemistry, Indiana University, 800 East Kirkwood Avenue, Bloomington, IN 47405 (USA) Department of Chemistry, Korea Advanced Institute of Science and Technology (KAIST), Daejeon 34141 (Republic of Korea).

Maren Pink, Department of Chemistry, Indiana University, 800 East Kirkwood Avenue, Bloomington, IN 47405 (USA).

Mu-Hyun Baik, Department of Chemistry, Korea Advanced Institute of Science and Technology (KAIST), Daejeon 34141 (Republic of Korea); Center for Catalytic Hydrocarbon Functionalizations, Institute for Basic Science (IBS), Daejeon 34141 (Republic of Korea).

Silas P. Cook, Department of Chemistry, Indiana University, 800 East Kirkwood Avenue, Bloomington, IN 47405 (USA)

References

- [1].a) Cowdrey WA, Hughes ED, Ingold CK, Masterman S,Scott AD, J. Chem. Soc 1937, 1252; [Google Scholar]; b) Xie J, Hase WL, Science 2016, 352, 32–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Carey FA, Sundberg RJ, Advanced Organic Chemistry, 5th ed., Springer, New York, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- [3].a) Jacobsen EN, Pfaltz A, Yamamoto H, Comprehensive Asymmetric Catalysis, Springer, New York, 1999; [Google Scholar]; b) Cozzi PG, Benfatti F, Angew. Chem. Int. Ed 2010, 49, 256–259; Angew. Chem. 2010, 122, 264 – 267; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) Wendlandt AE, Vangal P, Jacobsen EN, Nature 2018, 556, 447–451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Pronin SV, Reiher CA, Shenvi RA, Nature 2013, 501, 195–199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Bryan MC, Dunn PJ, Entwistle D, Gallou F, Koenig SG,Hayler JD, Hickey MR, Hughes S, Kopach ME, Moine G, Richardson P, Roschangar F, Steven A, Weiberth FJ, Green Chem. 2018, 20, 5082–5103. [Google Scholar]

- [6].Swamy KCK, Kumar NNB, Balaraman E, Kumar KVPP, Chem. Rev 2009, 109, 2551–2651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].a) An J, Denton RM, Lambert TH, Nacsa ED, Org. Biomol. Chem 2014, 12, 2993–3003; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Beddoe RH, Sneddon HF, Denton RM, Org. Biomol. Chem 2018, 16, 7774–7781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Emer E, Sinisi R, Capdevila MG, Petruzziello D, De Vincentiis F, Cozzi PG, Eur. J. Org. Chem 2011, 647–666. [Google Scholar]

- [9].a) Jana U, Maiti S, Biswas S, Tetrahedron Lett. 2008, 49, 858–862; [Google Scholar]; b) Yamamoto H, Nakata K, Org. Lett 2018, 20, 7057–7061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].a) Gu rinot A, Serra-Muns A, Gnamm C, Bensoussan C, Reymond S, Cossy J, Org. Lett 2010, 12, 1808–1811; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Trillo P, Baeza A, N jera C, Eur. J. Org. Chem 2012, 2929–2934. [Google Scholar]

- [11].Zhan Z-P, Yu J-P, Liu H-J, Cui Y-Y, Yang R-F, Yang W-Z, Li J-P, J. Org. Chem 2006, 71, 8298–8301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].a) Han F, Yang L, Li Z, Xia C, Adv. Synth. Catal 2012, 354, 1052–1060; [Google Scholar]; b) Dryzhakov M, Hellal M, Wolf E, Falk FC, Moran J, J. Am. Chem. Soc 2015, 137, 9555–9558; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) M tro T-X, Fayet C, Arnaud F, Rameix N, Fraisse P, Janody S, Sevrin M, George P, Vogel R, Synlett 2011, 684–688. [Google Scholar]

- [13].Moran J, Dryzhakov M, Richmond E, Synthesis 2016, 48, 935–959. [Google Scholar]

- [14].Jefferies LR, Cook SP, Org. Lett 2014, 16, 2026–2029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Bunrit A, Dahlstrand C, Olsson SK, Srifa P, Huang G, Orthaber A, Sjçberg PJR, Biswas S, Himo F, Samec JSM, J. Am. Chem. Soc 2015, 137, 4646–4649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].a) Hughes ED, Ingold CK, Martin RJL, Meigh DF, Nature 1950, 166, 679–680; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) M ller P, Rossier J-C, J. Chem. Soc. Perkin Trans 2 2000, 2232–2237. [Google Scholar]

- [17].Sommer LH, Carey FA, J. Org. Chem 1967, 32, 800–805. [Google Scholar]

- [18].a) Mukaiyama T, Shintou T, Fukumoto K, J. Am. Chem. Soc 2003, 125, 10538–10539; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Shintou T, Mukaiyama T, J. Am. Chem. Soc 2004, 126, 7359–7367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].a) Schudel P, Mayer H, Metzger J, R egg R, Isler O, Helv. Chim. Acta 1963, 46, 333–343; [Google Scholar]; b) Cohen N, Lopresti RJ, Neukom C, J. Org. Chem 1981, 46, 2445–2450. [Google Scholar]

- [20].Ellman JA, Owens TD, Tang TP, Acc. Chem. Res 2002, 35, 984–995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].a) Jefferies LR, Cook SP, Tetrahedron 2014, 70, 4204–4207; [Google Scholar]; b) Cook S, Jefferies L, Weber S, Synlett 2014, 26, 331–334; [Google Scholar]; c) Beck W, Suenkel K, Chem. Rev 1988, 88, 1405–1421. [Google Scholar]

- [22].Whitmore FC, J. Am. Chem. Soc 1932, 54, 3274–3283. [Google Scholar]

- [23].a) Komeyama K, Morimoto T, Takaki K, Angew. Chem. Int. Ed 2006, 45, 2938–2941; Angew. Chem. 2006, 118, 3004 – 3007; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Michaux J, Terrasson V, Marque S, Wehbe J, Prim D, Campagne J-M, Eur. J. Org. Chem 2007, 2601–2603. [Google Scholar]

- [24].a) Cram DJ, J. Am. Chem. Soc 1949, 71, 3863–3870; [Google Scholar]; b) Cram DJ, J. Am. Chem. Soc 1952, 74, 2129–2137. [Google Scholar]

- [25].Liu D, Zhao G, Xiang L, Eur. J. Org. Chem 2010, 3975–3984. [Google Scholar]

- [26].Anas S, Kagan HB, Tetrahedron: Asymmetry 2009, 20, 2193–2199. [Google Scholar]

- [27].a) Liwosz TW, Chemler SR, J. Am. Chem. Soc 2012, 134, 2020–2023; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Ingalls EL, Sibbald PA, Kaminsky W, Michael FE, J. Am. Chem. Soc 2013, 135, 8854–8856. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].a) Kuwano R, Sato K, Kurokawa T, Karube D, Ito Y, J. Am. Chem. Soc 2000, 122, 7614–7615; [Google Scholar]; b) Duan Y, Li L, Chen M-W, Yu C-B, Fan H-J, Zhou Y-G, J. Am. Chem. Soc 2014, 136, 7688–7700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Saito K, Akiyama T, Angew. Chem. Int. Ed 2016, 55, 3148–3152; Angew. Chem. 2016, 128, 3200 – 3204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Yamamoto H, Pandey G, Asai Y, Nakano M, Kinoshita A, Namba K, Imagawa H, Nishizawa M, Org. Lett 2007, 9, 4029–4032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Shohji N, Kawaji T, Okamoto S, Org. Lett 2011, 13, 2626–2629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].a) Humski K, Sendijarevic V, Shiner VJ, J. Am. Chem. Soc 1976, 98, 2865–2868; [Google Scholar]; b) Humski K, Sendijarevic V, Shiner VJ, J. Am. Chem. Soc 1973, 95, 7722–7728. [Google Scholar]

- [33].Hugelshofer CL, Mellem KT, Myers AG, Org. Lett 2013, 15, 3134–3137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.