Abstract

Objective:

Research on the heterogeneity in drinking patterns of urban minorities within a socioecological framework is rare. The purpose of this study was to explore multiple, distinct patterns of drinking from adolescence to young adulthood in a sample of urban minority youth and to examine the influence of neighborhood, family, and peers on these trajectories.

Method:

Data are from a longitudinal study of 584 (56% male) primarily Black (87%) youth who were first sampled in childhood based on their residence in low-income neighborhoods in Baltimore City and followed up annually through age 26. Data were analyzed using group-based trajectory modeling and multinomial logistic regression.

Results:

Modeling revealed six trajectories from ages 14 to 26: abstainer, experimenter, adult increasing, young adult increasing, adolescent limited, and adolescent increasing. Neighborhood disadvantage was a risk factor for drinking regardless of the timing of onset. Perceptions of availability, peer drinking, and parental approval for drinking were risk factors for underage drinking trajectories, whereas parental supervision was a significant protective factor. Positive social activities in neighborhoods was protective against increased drinking, whereas a decline in perceptions of peer drinking was associated with adolescent-limited drinking.

Conclusions:

Our findings uniquely highlight the importance of developing interventions involving parents for urban minority youth for whom family is particularly relevant in deterring underage drinking. Perhaps most importantly, our data suggest that interventions that support positive social activities in disadvantaged neighborhoods are protective against adolescent drinking and altering perceptions of peer drinking may reduce adolescent drinking among low-income, urban minority youth.

Studies of drinking frequency during the life course generally focus on the most common pattern of drinking, which typically begins during adolescence, peaks during emerging adulthood, and declines during the mid-20s (Chen & Jacobson, 2012). Within this larger pattern, however, there is likely a great deal of heterogeneity that warrants further exploration. Trajectory modeling is one approach that has been used to identify multiple patterns of drinking through which individuals initiate, progress, and desist in their drinking (Nagin, 1999). Findings are generally consistent with most studies of drinking frequency identifying patterns of no/low use, adolescent limited use, late adolescent increasing use, and chronic, early use (Colder et al., 2002; Flory et al., 2004; Jackson & Sher, 2005; Li et al., 2002; Lynne-Landsman et al., 2010; Wanner et al., 2006).

Most studies of drinking trajectories use national probability or primarily White samples. Few focus on racial/ethnic minorities or, in particular, Blacks, who disproportionately live in low-income, urban neighborhoods and for whom the problems associated with drinking are a particular public health concern. Although national surveillance data indicate that rates of underage drinking are highest among Whites, heavy drinking and abuse peak later, persist longer, and result in more drinking problems among Blacks (Caetano, 1997; Lee et al., 2010; Mulia et al., 2009). Urban Blacks are less likely to experience factors that promote maturation out of heavy drinking, such as having a steady job (Haynie & Payne, 2006). They get married later, do not stay married as long, and are less likely to reduce their drinking once married (Mudar et al., 2002; Wilson, 1987). In one of the few studies examining drinking trajectories from adolescence to young adulthood among urban Blacks, Flory et al. (2006) identified three groups between Grades 6–10 and age 20: a group that used alcohol in 6th grade and peaked in 9th grade, a group that began using alcohol in 9th grade, and a group of nonusers. In an ethnically diverse sample (29% Black) with longer and more frequent follow-up, Nelson et al. (2015) found eight trajectories between ages 12 and 24: (a) abstainers, (b) early-onset low users, (c) young adult– onset moderate increasers, (d) young adult–onset moderate decreasers, (e) young adult–onset steep increasers, (f) post– high school steep increasers, (g) high school–onset steep increasers, and (h) early-onset moderate increasers with several characterizing later onset use.

Research on factors associated with drinking patterns of racial/ethnic minorities is also rare (D’Amico et al., 2014). Because individual-level behavior is embedded within social contexts such as neighborhoods, peer groups, and families, we use a socioecological framework (Bronfenbrenner, 1994) to guide our understanding of the correlates of drinking trajectories. In impoverished urban neighborhoods, residents may be unable to maintain social control over activities in their neighborhoods (e.g., monitoring street corner activity) and as a result, underage drinking may flourish, thereby promoting ease of availability to youth as well as reinforcement of positive drinking norms (Sampson et al., 1997). Findings of an association between neighborhood disadvantage and drinking, however, are limited and inconsistent (Bryden et al., 2013; Karriker-Jaffe et al., 2011). In contrast, Ryan et al. (2010) identified multiple features of family relationship quality that were important protective factors in delaying the onset of drinking (e.g., parental monitoring). Family context may be more important for Blacks, with several studies demonstrating a protective effect of positive parenting in disadvantaged but not conventional neighborhoods (Chuang et al., 2005; Plybon & Kliewer, 2001; Rankin & Quane, 2002). Permissive family norms regarding drinking, however, confer an increased risk (Kosterman et al., 2000; Tobler et al., 2009).

The pressure of living in urban neighborhoods can degrade family functioning and overwhelm parenting effectiveness (Byrnes & Miller, 2012). This can precipitate drift into deviant peer groups where youth have opportunities to engage in drinking, and drinking is likely modeled and reinforced (Patterson et al., 1992). Impoverished urban neighborhoods with limited capacity to monitor and control youth activities also facilitate the formation of deviant peer groups, thereby providing a context in which values conducive to adolescent drinking can arise and spread (Dishion & Tipsord, 2011; Elliott et al., 2006; Harrop & Catalano, 2016). According to Jencks and Mayer (1990), youth in disadvantaged neighborhoods are more likely to be influenced by deviant peer groups than youth living in conventional neighborhoods. On the other hand, youth in conventional neighborhoods may be more likely to select peers whose alcohol use correlates with their own use or socialize with friends who drink because they believe it is a high-status activity (Osgood et al., 2013).

The present study contributes to the limited literature on trajectories of drinking in urban, minority samples by estimating trajectories of drinking from age 14 to 26 in a sample of primarily low-income, urban Blacks and examining the influence of risk and protective factors on trajectories within a socioecological framework that may be particularly relevant for this population. This work builds on previous work by spanning the entire period from adolescence through young adulthood and considering both objective and subjective measures, including census data and field-rater assessments of the neighborhood, as well as peer and family factors on multiple, distinct drinking trajectories of urban, minority youth.

Method

Sample

Data were drawn from a longitudinal study conducted by the Baltimore Prevention Intervention Research Center at Johns Hopkins University. The study population consisted of 799 children and families entering first grade in nine Baltimore City public elementary schools in 1993. Children were recruited for participation in interventions targeting early learning and aggressive behavior (Ialongo et al., 1999). Interventions were limited to the first-grade year. The sample was predominantly Black (85%), and 46% were male. About two thirds received free or reduced-price meals in first grade, a proxy for low socioeconomic status. This research was reviewed and approved by the Institutional Review Board of the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health. The analytic sample consisted of 584 participants who had at least an eighth-grade assessment. Fifty-six percent were male, 87% were Black, and 52% were receiving free or reduced-price meals in eighth grade. The mean age in eighth grade was 13.8 years. There were no differences with respect to participant sex, receipt of free or reduced-price meals in first grade, intervention group membership, or teacher ratings of behavior in first grade between participants lost to follow-up and those with an eighth-grade assessment. Among those with an eighth-grade assessment, 82% (n = 477) had an age 26 assessment. Those missing an age 26 assessment were significantly more likely to be male (65% vs. 54%; ϕ = .09), less likely to be Black (78% vs. 89%; ϕ = -.13), and more likely to be receiving free or reduced-price meals in eighth grade (63% vs. 50%; ϕ = .10). They did not differ on neighborhood, peer, or family factors or frequency of drinking.

Measures

Alcohol use.

Data on substance use were collected annually using an audio computer-assisted interview to increase accurate reporting of sensitive behavior. Past-year frequency of use of alcohol was used in this analysis (0 = none, 1 = once, 2 = twice, 3 = 3–4 times, 4 = 5–9 times, 5 = 10–19 times, 6 = 20–39 times, 7 = 40 or more times) to identify trajectories from eighth grade (approximately age 14) to age 26.

Neighborhood factors.

Perceptions of neighborhood disorder were assessed in eighth grade using 10 items from the Neighborhood Environment Scale (Elliott et al., 1985). This scale contains true/false items that assess neighborhood safety, violent crime, and drug use and sales. Items are rated on a 4-point Likert scale (1 = not at all true to 4 = very true) and summed to create a total score.

Level of neighborhood disadvantage was assessed using the Objective Neighborhood Disadvantage Score and calculated using items from the 2000 U.S. census and the participant’s eighth-grade address. The items include the percentage of (a) adults age 24 years and older with a college degree, (b) owner-occupied housing, (c) households with incomes below the federal poverty threshold, and (d) female-headed households with children. Higher values indicate greater disadvantage (Ross & Mirowsky, 2001).

Perception of alcohol availability was measured in eighth grade with the question, “How difficult do you think it would be to get alcohol if you wanted it?” and is rated on a 5-point Likert scale (1 = probably impossible, 2 = very difficult, 3 = fairly difficult, 4 = fairly easy, 5 = very easy).

Field-rater assessments of neighborhood physical disorder (e.g., broken windows) and positive social activity (e.g., adults watching youth) were performed in Baltimore City on the block face where youth lived in 12th grade. Resources were not available to perform assessments in neighborhoods where youth relocated outside of Baltimore City. Youth with a field-rater assessment were more likely to be Black, receiving free or reduced-price meals, and living in more disordered neighborhoods. Assessments were conducted using the Neighborhood Inventory for Environmental Typology, a reliable and valid instrument developed by Furr-Holden et al. (2008, 2010).

Family factors.

Perceived parental drinking approval was measured in eighth grade with the question, “How do you think your parents would feel about you using alcohol occasionally?” and is rated on a 3-point Likert scale (1 = would not disapprove, 2 = disapprove, 3 = strongly disapprove). Because of the low prevalence of the “would not disapprove” response, we compared youth who perceived that their parents “would not disapprove” or “disapprove” to those who perceived that their parents would “strongly disapprove.” Parental supervision was assessed in eighth grade with the question, “When you get home from school, how often is someone there within an hour? By someone, we mean an adult like your parents or a babysitter,” and was rated on a 5-point Likert scale (1 = never, 2 = hardly ever, 3 = sometimes, 4 = most times, 5 = all of the time).

Peer factors.

Perceived peer drinking approval was measured in eighth grade with the question, “How do you think your close friends would feel about you drinking alcohol occasionally?” and was rated on a 3-point Likert scale (1 = would not disapprove, 2 = disapprove, 3 = strongly disapprove). Similar to parental perceptions, this item was dichotomized to compare youth whose friends do not “strongly disapprove” to all other responses. Perceived peer drinking was assessed in eighth grade with the question, “How many of your friends get drunk at least once a week?” and was rated on a 5-point scale (1 = none, 2 = very few, 3 = some, 4 = most of them, 5 = all of them).

Statistical analyses

Group-based trajectory modeling was used to identify patterns of past-year drinking frequency from age 14 to 26 (Nagin, 1999). Models used a zero-inflated Poisson distribution to account for the large number of youth who did not drink. Linear and quadratic terms for each trajectory group were included and compared. One to seven group models were considered. The best model was selected based on a combination of the Bayesian information criteria (BIC), entropy, group interpretability, and having reasonably large groups. Trajectory models were constructed using PROC TRAJ in SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC). Maximum likelihood estimation was used to estimate model parameters. Participants were assigned to the drinking trajectory group with the highest probability of membership.

Overall tests of associations between trajectory groups and covariates were assessed via chi-squared tests. A multinomial logistic regression model examined associations between trajectory groups and neighborhood, family, and peer factors in a combined model adjusting for individuallevel factors. Continuous covariates were standardized in all regression models to facilitate the comparison of effect sizes across predictors. Odds ratios (ORs) of 1.5, 2, and 3 were considered small, medium, and large effect sizes, respectively, for ORs >1 and 0.7, 0.5, and 0.3 for ORs < 1 (Sullivan & Feinn, 2012).

The only covariate in eighth grade with missing data was free or reduced-price meal status (23.3% missing). Because of the large degree of missingness, we imputed missing lunch values using multiple imputations by chained equations (Royston et al., 2009). Lunch status was imputed using a prediction model containing the variables with complete data used in the primary analysis. Twenty imputations were performed using PROC MI in SAS Version 9.4. Primary analysis of the imputed data sets was performed using PROC MIANALYZE.

Results

Trajectory modeling

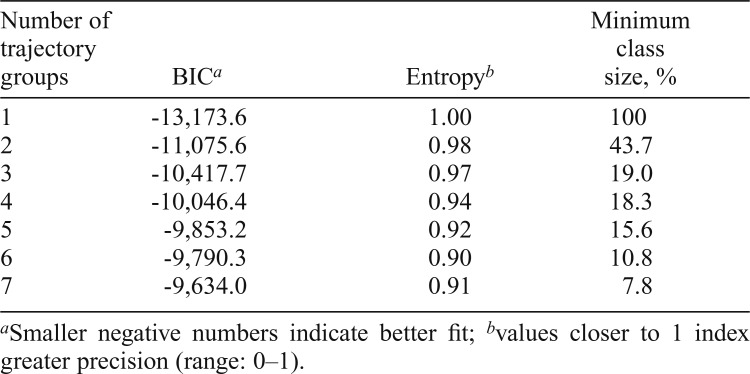

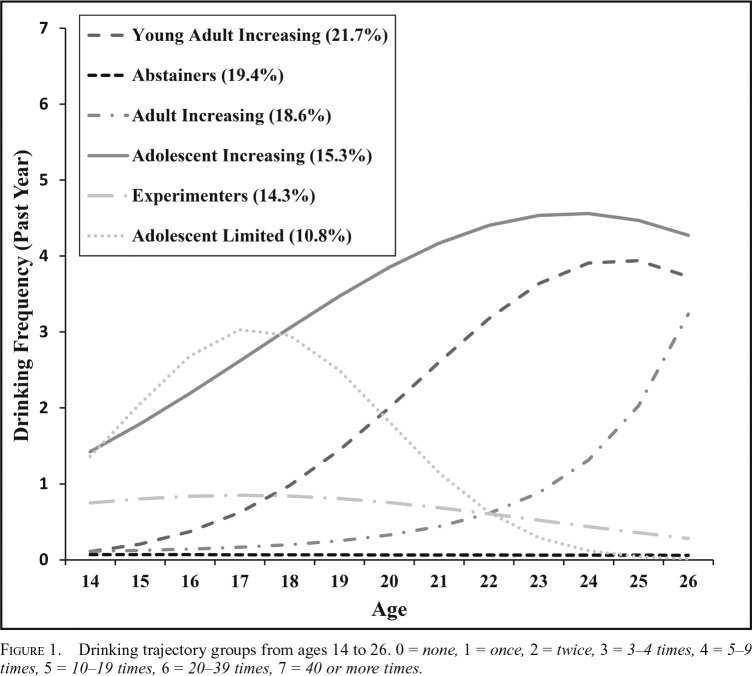

The BIC increased with the addition of each trajectory group but the rate of improvement declined and reached an elbow at six groups (Table 1). Entropy measures indicated that classification accuracy was adequate for all models. The six-group model is presented in Figure 1. The largest group shows a rapid increase in drinking at age 18 or early in young adulthood (Group 1; young adult increasing; prevalence: 21.7%). The second largest group reports little to no drinking between ages 14 and 26 (Group 2; abstainers; prevalence: 19.4%). The third group reports very little drinking until after the legal drinking age of 21, at which point drinking frequency increases steadily until age 26 (Group 3; adult increasing; prevalence: 18.6%). The fourth group initiates drinking in adolescence and rapidly increases to more frequent drinking (Group 4; adolescent increasing; prevalence: 15.3%). The fifth group begins drinking in adolescence but very infrequently, declining to little to no drinking by age 26 (Group 5; experimenters; prevalence: 14.3%). The sixth group initiates drinking in adolescence but declines in drinking at age 18 (Group 6; adolescent limited; prevalence: 10.8%). The addition of a seventh group resulted in a small group of “young adult limited” drinkers. In regression models, this group did not differ from abstainers or the other group of young adult drinkers (“young adult increasing”) (data not shown). Therefore, because of concerns about potentially overfitting of the model, we chose the more parsimonious six-group trajectory model.

Table 1.

Fit indices for alcohol trajectory group solutions

| Number of trajectory groups | BICa | Entropyb | Minimum class size, % |

| 1 | -13,173.6 | 1.00 | 100 |

| 2 | -11,075.6 | 0.98 | 43.7 |

| 3 | -10,417.7 | 0.97 | 19.0 |

| 4 | -10,046.4 | 0.94 | 18.3 |

| 5 | -9,853.2 | 0.92 | 15.6 |

| 6 | -9,790.3 | 0.90 | 10.8 |

| 7 | -9,634.0 | 0.91 | 7.8 |

Smaller negative numbers indicate better fit

values closer to 1 index greater precision (range: 0–1).

Figure 1.

Drinking trajectory groups from ages 14 to 26. 0 = none, 1 = once, 2 = twice, 3 = 3–4 times, 4 = 5–9 times, 5 = 10–19 times, 6 = 20–39 times, 7 = 40 or more times.

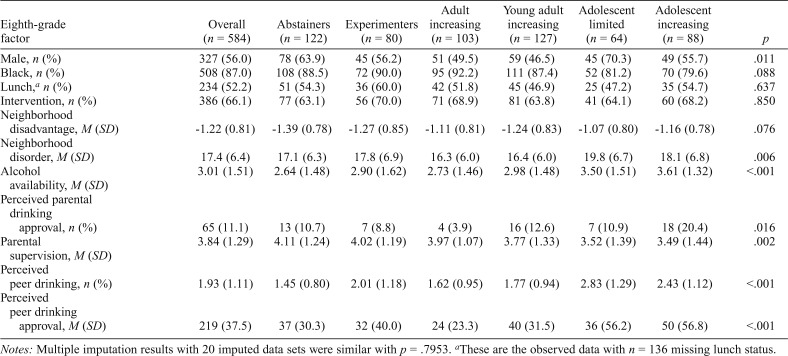

Trajectory associations with covariates

Alcohol trajectory groups did not vary significantly across individual demographic characteristics except gender, with males less likely to be in the adult and young adult increasing groups (Table 2). Although 52% of youth received free or reduced-priced meals in eighth grade, youth generally did not perceive their neighborhoods to be disordered (M = 17.4, range: 10–40) or for alcohol to be easily obtained (M = 3.01, range: 1–5). Only 11% perceived that their parents approved of their drinking compared to 38% of peers. There was variation in these factors, however, across trajectory groups supporting their validity (Table 2). Both groups of adolescent drinkers reported higher levels of neighborhood disorder, greater perceived availability of alcohol, perceptions that more friends drink, and the lowest frequency of after-school supervision compared with other groups. Adolescent increasers reported the highest prevalence of perceived parental and friend approval of their drinking.

Table 2.

Individual, neighborhood, family and peer factors by alcohol trajectory group

| Eighth-grade factor | Overall (n = 584) | Abstainers (n = 122) | Experimenters (n = 80) | Adult increasing (n = 103) | Young adult increasing (n = 127) | Adolescent limited (n = 64) | Adolescent increasing (n = 88) | p |

| Male, n (%) | 327 (56.0) | 78 (63.9) | 45 (56.2) | 51 (49.5) | 59 (46.5) | 45 (70.3) | 49 (55.7) | .011 |

| Black, n (%) | 508 (87.0) | 108 (88.5) | 72 (90.0) | 95 (92.2) | 111 (87.4) | 52 (81.2) | 70 (79.6) | .088 |

| Lunch,a n (%) | 234 (52.2) | 51 (54.3) | 36 (60.0) | 42 (51.8) | 45 (46.9) | 25 (47.2) | 35 (54.7) | .637 |

| Intervention, n (%) | 386 (66.1) | 77 (63.1) | 56 (70.0) | 71 (68.9) | 81 (63.8) | 41 (64.1) | 60 (68.2) | .850 |

| Neighborhood disadvantage, M (SD) | -1.22 (0.81) | -1.39 (0.78) | -1.27 (0.85) | -1.11 (0.81) | -1.24 (0.83) | -1.07 (0.80) | -1.16 (0.78) | .076 |

| Neighborhood disorder, M (SD) | 17.4 (6.4) | 17.1 (6.3) | 17.8 (6.9) | 16.3 (6.0) | 16.4 (6.0) | 19.8 (6.7) | 18.1 (6.8) | .006 |

| Alcohol availability, M (SD) | 3.01 (1.51) | 2.64 (1.48) | 2.90 (1.62) | 2.73 (1.46) | 2.98 (1.48) | 3.50 (1.51) | 3.61 (1.32) | <.001 |

| Perceived parental drinking approval, n (%) | 65 (11.1) | 13 (10.7) | 7 (8.8) | 4 (3.9) | 16 (12.6) | 7 (10.9) | 18 (20.4) | .016 |

| Parental supervision, M (SD) | 3.84 (1.29) | 4.11 (1.24) | 4.02 (1.19) | 3.97 (1.07) | 3.77 (1.33) | 3.52 (1.39) | 3.49 (1.44) | .002 |

| Perceived peer drinking, n (%) | 1.93 (1.11) | 1.45 (0.80) | 2.01 (1.18) | 1.62 (0.95) | 1.77 (0.94) | 2.83 (1.29) | 2.43 (1.12) | <.001 |

| Perceived peer drinking approval, M (SD) | 219 (37.5) | 37 (30.3) | 32 (40.0) | 24 (23.3) | 40 (31.5) | 36 (56.2) | 50 (56.8) | <.001 |

Notes: Multiple imputation results with 20 imputed data sets were similar with p = .7953.

These are the observed data with n = 136 missing lunch status.

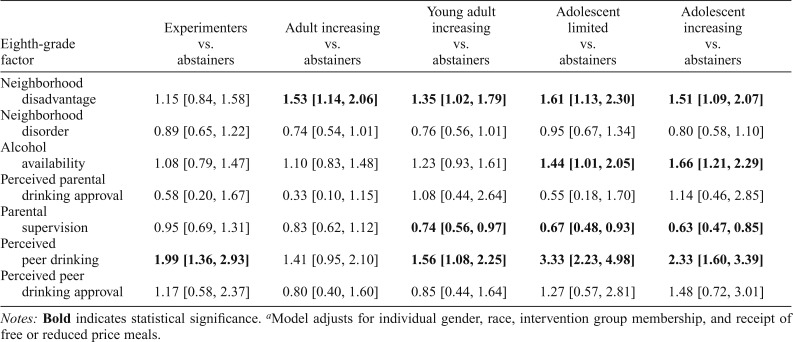

Regression modeling

First, we compared each drinking trajectory group to abstainers to examine predictors of drinking (Table 3). Youth living in disadvantaged neighborhoods were more likely to drink alcohol than be abstainers, regardless of the timing of the onset of drinking (OR = 1.53, 95% CI [1.14, 2.06], adult increasing; OR = 1.35, 95% CI [1.02, 1.79], young adult increasing; OR = 1.61, 95% CI [1.13, 2.30], adolescent limited; OR = 1.51, 95% CI [1.09, 2.07], adolescent increasing). Youth with higher levels of parental supervision after school were less likely to be underage drinkers (OR = 0.74, 95% CI [0.56, 0.97], young adult increasing; OR = .67, 95% CI [0.48, 0.93], adolescent limited; OR = 0.63, CI [0.47, 0.85], adolescent increasing), whereas youth who perceived that more friends drink were more likely to be underage drinkers (OR = 1.56, 95% CI [1.08, 2.25], young adult increasing; OR = 3.33, 95% CI [2.23, 4.98], adolescent limited; OR = 2.33, 95% CI [1.60, 3.39], adolescent increasing) relative to abstainers. Youth who perceived greater availability of alcohol were more likely to initiate alcohol use in adolescence (OR = 1.44, 95% CI [1.01, 2.05], adolescent limited; OR = 1.66, 95% CI [1.21, 2.29], adolescent increasing) relative to abstainers. Youth who perceived that more friends drink were more likely to be experimenters than abstainers (OR = 1.99, 95% CI [1.36, 2.93]). Among youth residing in Baltimore City in 12th grade, youth with more positive social activity in their neighborhood were less likely to be adolescent increasers relative to abstainers (OR = 0.70, 95% CI [0.52, 0.96]; data not shown in the table).

Table 3.

Multivariable multinomial alcohol trajectory group model comparing each drinking group to abstainers: Odds ratios [95% confidence intervals]a

| Eighth-grade factor | Experimenters vs. abstainers | Adult increasing vs. abstainers | Young adult increasing vs. abstainers | Adolescent limited vs. abstainers | Adolescent increasing vs. abstainers |

| Neighborhood disadvantage | 1.15 [0.84, 1.58] | 1.53 [1.14, 2.06] | 1.35 [1.02, 1.79] | 1.61 [1.13, 2.30] | 1.51 [1.09, 2.07] |

| Neighborhood disorder | 0.89 [0.65, 1.22] | 0.74 [0.54, 1.01] | 0.76 [0.56, 1.01] | 0.95 [0.67, 1.34] | 0.80 [0.58, 1.10] |

| Alcohol availability | 1.08 [0.79, 1.47] | 1.10 [0.83, 1.48] | 1.23 [0.93, 1.61] | 1.44 [1.01, 2.05] | 1.66 [1.21, 2.29] |

| Perceived parental drinking approval | 0.58 [0.20, 1.67] | 0.33 [0.10, 1.15] | 1.08 [0.44, 2.64] | 0.55 [0.18, 1.70] | 1.14 [0.46, 2.85] |

| Parental supervision | 0.95 [0.69, 1.31] | 0.83 [0.62, 1.12] | 0.74 [0.56, 0.97] | 0.67 [0.48, 0.93] | 0.63 [0.47, 0.85] |

| Perceived peer drinking | 1.99 [1.36, 2.93] | 1.41 [0.95, 2.10] | 1.56 [1.08, 2.25] | 3.33 [2.23, 4.98] | 2.33 [1.60, 3.39] |

| Perceived peer drinking approval | 1.17 [0.58, 2.37] | 0.80 [0.40, 1.60] | 0.85 [0.44, 1.64] | 1.27 [0.57, 2.81] | 1.48 [0.72, 3.01] |

Notes: Bold indicates statistical significance.

Model adjusts for individual gender, race, intervention group membership, and receipt of free or reduced price meals.

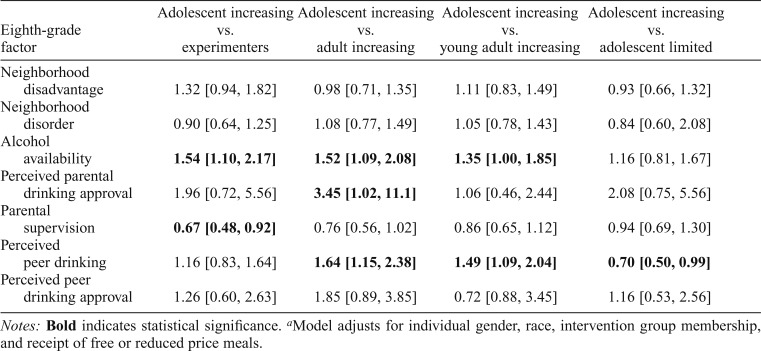

Next, we compared the adolescent increasing trajectory with the other drinking trajectories to examine predictors of what we consider the riskiest drinking trajectory (Table 4). Youth who perceived greater availability of alcohol were more likely to be in the adolescent increasing group relative to the experimenter (OR = 1.54, 95% CI [1.10, 2.17]), adult increasing (OR = 1.52, 95% CI [1.09, 2.08]), and young adult increasing (OR = 1.35, 95% CI [1.00, 1.85]) groups. Similarly, youth who perceived that more friends drink were more likely to be in the adolescent increasing group relative to the adult increasing (OR = 1.64, 95% CI [1.15, 2.38]) and young adult increasing (OR = 1.49, 95% CI [1.09, 2.04]) groups. Youth who perceived that their parents approved of their drinking were more likely to be adolescent increasers relative to adult increasers (OR = 3.45, 95% CI [1.02, 11.1]). Youth with more parental supervision after school were less likely to be in the adolescent increasing group relative to the experimenter group (OR = 0.67, 95% CI [0.37, 0.92]). Among youth residing in Baltimore City in 12th grade, youth with more positive social activity in their neighborhood were less likely to be adolescent increasers relative to experimenters (OR = 0.69, 95% CI [0.50, 0.94]; data not shown in the table).

Table 4.

Multivariable multinomial alcohol trajectory group model results comparing each drinking group to the adolescent increasing trajectory group: Odds ratios [95% confidence intervals]a

| Eighth-grade factor | Adolescent increasing vs. experimenters | Adolescent increasing vs. adult increasing | Adolescent increasing vs. young adult increasing | Adolescent increasing vs. adolescent limited |

| Neighborhood disadvantage | 1.32 [0.94, 1.82] | 0.98 [0.71, 1.35] | 1.11 [0.83, 1.49] | 0.93 [0.66, 1.32] |

| Neighborhood disorder | 0.90 [0.64, 1.25] | 1.08 [0.77, 1.49] | 1.05 [0.78, 1.43] | 0.84 [0.60, 2.08] |

| Alcohol availability | 1.54 [1.10, 2.17] | 1.52 [1.09, 2.08] | 1.35 [1.00, 1.85] | 1.16 [0.81, 1.67] |

| Perceived parental drinking approval | 1.96 [0.72, 5.56] | 3.45 [1.02, 11.1] | 1.06 [0.46, 2.44] | 2.08 [0.75, 5.56] |

| Parental supervision | 0.67 [0.48, 0.92] | 0.76 [0.56, 1.02] | 0.86 [0.65, 1.12] | 0.94 [0.69, 1.30] |

| Perceived peer drinking | 1.16 [0.83, 1.64] | 1.64 [1.15, 2.38] | 1.49 [1.09, 2.04] | 0.70 [0.50, 0.99] |

| Perceived peer drinking approval | 1.26 [0.60, 2.63] | 1.85 [0.89, 3.85] | 0.72 [0.88, 3.45] | 1.16 [0.53, 2.56] |

Notes: Bold indicates statistical significance.

Model adjusts for individual gender, race, intervention group membership, and receipt of free or reduced price meals.

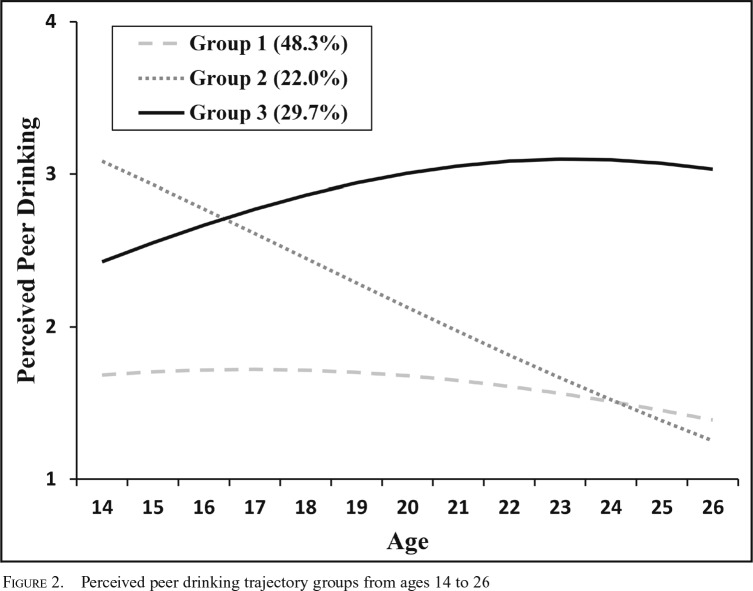

Using group-based trajectory modeling, we explored whether changes in perceptions of peer drinking explained differences between the adolescent increasing and adolescent limited trajectories. A three-group trajectory model provided the best fit to the data (Figure 2). The largest group (48.3%) perceived that few peers drink through adulthood, whereas one group increased in its perceptions of peer drinking (29.7%) and the other decreased (22.0%). Youth whose perceptions of peer drinking decreased were significantly more likely than those whose increased to be in the adolescent limited group compared with the adolescent increasing group (OR = 10.9, 95% CI [4.3, 27.4]).

Figure 2.

Perceived peer drinking trajectory groups from ages 14 to 26

Discussion

We identified six trajectories that reflect variation in both the timing of onset and drinking frequency from adolescence to young adulthood in an urban, primarily Black sample. Almost 40% of our sample abstained from drinking or did not initiate use until after age 21, findings that are consistent with national data showing that Blacks have higher rates of complete abstinence and initiate drinking later than other racial/ethnic groups (Flewelling et al., 2004). Similar to Nelson et al.’s (2015) findings in an ethnically diverse sample, the most prevalent underage drinking pattern was drinking that commenced during the transition from high school to young adulthood, rapidly escalating until age 26. Despite these later initiation patterns, 40% of our sample exhibited adolescent-onset drinking patterns typically found in non-minority samples. Whereas one group drank infrequently and desisted in their drinking, one group escalated use into adulthood. This group has been shown to be at greatest risk for alcohol-related problems (e.g., Colder et al., 2002). A third group exhibited a developmentally limited drinking pattern. The life course perspective emphasizes how specific “turning points,” such as college enrollment, employment, marriage, or parenting, can redirect a negative trajectory (Elder & Caspi, 1988). In impoverished communities with fewer job opportunities, later marriage, and earlier parenting, it is important to understand what other factors may redirect trajectories as well as identify malleable factors early in the life course that prevent early initiation.

Youth living in disadvantaged neighborhoods were more likely to exhibit increasing levels of drinking regardless of the timing of onset. Research has found that alcohol outlets are more likely to be located in poor and disadvantaged communities (LaVeist & Wallace, 2000) and that the density of alcohol outlets is associated with increased alcohol consumption (Huckle et al., 2008; Treno et al., 2008). Youth living in disadvantaged neighborhoods may therefore be at increased risk for initiation and continued use of alcohol because it is widely available. Perceptions of availability had similar but small effects on the risk for adolescent-onset drinking and, in particular, adolescent increasing drinking relative to both young adult and adult increasing drinking. Some studies have found an association between aspects of the neighborhood environment (e.g., alcohol outlets) and perceived availability among youth (Kuntsche et al., 2008; Milam et al., 2016). The presence of alcohol outlets can shape perceptions of availability by giving the impression that underage drinking is common and socially endorsed as well as strengthen positive expectancies of use (Sampson et al., 1997). Youth may also perceive that alcohol is easily obtainable and have increased opportunities for use through their peer networks.

Perceived parental approval had the largest effect on any drinking trajectory, specifically adolescent increasing drinking relative to adult-onset drinking. This finding is consistent with studies showing that permissive family norms are strongly associated with adolescent drinking (Kosterman et al., 2000; Tobler et al., 2009). Having a parent or guardian at home after school had a small protective effect for underage drinking (both adolescent and young adult) relative to abstaining from drinking. It also distinguished adolescent increasers and experimenters. Supervision after school may buffer youth from peer influence, which may be especially important in disadvantaged neighborhoods where neighbors are unable to monitor youth activities and peers have more influence than in conventional neighborhoods (Jencks & Mayer, 1990; Skinner et al., 2009). In fact, perceptions of peer drinking had significant small to medium-size effects on underage drinking (both adolescent and young adult) relative to abstaining from drinking, suggesting that socialization of drinking may occur through modeling (Giletta et al., 2012). Perceptions of peer drinking were also associated with the riskiest drinking trajectory, adolescent-onset increasing drinking, relative to young adult and adult increasing trajectories. Perceptions of peer approval, however, were not associated with drinking trajectories. These findings are consistent with a study by Biddle et al. (1980) that found peers are more likely to influence adolescents through modeling, whereas parental influence is more strongly exerted through norms. We also found a large effect of decreases in perceptions of peer drinking on desistance in drinking, suggesting that interventions focused on changing peer networks may have the ability to redirect a risky drinking trajectory.

Last, positive social activity in the neighborhood, which is a potential proxy for increased neighborhood surveillance and prosocial neighborhood-level norms, had a small protective effect. Youth living in neighborhoods with prosocial activities were significantly less likely to initiate and rapidly escalate their drinking in adolescence relative to being an experimenter or abstainer, demonstrating that even in economically disadvantaged urban neighborhoods social interactions beyond the family have a positive impact on drinking.

Some limitations should be noted. First, as is the case with most longitudinal studies, some youth were lost to follow-up or had moved outside of Baltimore City by 12th grade so that field-rater objective neighborhood measures were not available. These youth tended to have fewer social and economic resources. Second, several individual-level (externalizing symptoms, temperament) as well as social contextual (peer delinquency, parental substance use, alcohol outlet density) factors associated with adolescent drinking were not included in our models and should be considered in future research. We also did not examine changes over time in predictor variables except for perceptions of peer drinking. Similar to perceptions of peer drinking, changes in factors like alcohol availability may redirect the course of a drinking trajectory. Third, our use of perceptions of peer drinking and alcohol availability, which are known to be biased by an adolescent’s own use, may provide inflated estimates of associations (Henry et al., 2011). Last, although the frequency of drinking is relatively low in this sample and could be attributable to our use of self-reports, it did confer an increased risk for negative outcomes; a third of adolescent-onset drinkers and 14% of young adult–onset drinkers reported alcohol abuse or dependence by age 26 compared with 8% of adult-onset drinkers. The greatest strength of this study is the availability of a large sample of low-income, urban, primarily Black youth participating in a longitudinal study designed to be sensitive to ethnic-minority populations. Although national probability studies have provided critical information on drinking in the U.S. population as a whole, they are less informative in understanding prevalence in subgroups, particularly low-income, minority populations living in large urban areas. This is one of the few studies that follows low-income Blacks from childhood to young adulthood and includes extensive measures of individual and social factors as well as an innovative field-rater assessment of the urban neighborhoods where they live.

This study lends support to the hypothesis that social factors are particularly relevant to understanding the etiology of drinking among urban minorities. Perceptions of availability that may be influenced by malleable targets such as neighborhood activities, parental norms, presence of alcohol outlets, and peer drinking were associated with adolescent drinking. Our findings uniquely highlight the importance of developing interventions involving parents of urban minority youth, for whom family is particularly relevant in deterring underage drinking. Perhaps most important, our data suggest that interventions that support positive social activities in disadvantaged neighborhoods are protective against adolescent drinking, and altering perceptions of peer drinking has the potential to reduce drinking among low-income, urban minority youth.

Footnotes

This research was supported by Grant DA032550 from the National Institute on Drug Abuse.

References

- Biddle B. J., Bank B. M., Marlin M. M. Parental and peer influences on adolescents. Social Forces. 1980;58:1057–1079. doi:10.1093/sf/58.4.1057. [Google Scholar]

- Bronfenbrenner U. Ecological models of human development. In: Husen T., Postlethwaite T., editors. The international encyclopedia of education. New York, NY: Elsevier Sciences; 1994. pp. 1643–1647. [Google Scholar]

- Bryden A., Roberts B., Petticrew M., McKee M. A systematic review of the influence of community level social factors on alcohol use. Health & Place. 2013;21:70–85. doi: 10.1016/j.healthplace.2013.01.012. doi:10.1016/j.healthplace.2013.01.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Byrnes H. F., Miller B. A. The relationship between neighborhood characteristics and effective parenting behaviors: The role of social support. Journal of Family Issues. 2012;33:1658–1687. doi: 10.1177/0192513X12437693. doi:10.1177/0192513X12437693. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caetano R. Prevalence, incidence and stability of drinking problems among whites, blacks and Hispanics: 1984-1992. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 1997;58:565–572. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1997.58.565. doi:10.15288/jsa.1997.58.565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen P., Jacobson K. C. Developmental trajectories of substance use from early adolescence to young adulthood: Gender and racial/ethnic differences. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2012;50:154–163. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2011.05.013. doi:10.1016/j.jadohealth.2011.05.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chuang Y.-C., Ennett S. T., Bauman K. E., Foshee V. A. Neighborhood influences on adolescent cigarette and alcohol use: Mediating effects through parent and peer behaviors. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 2005;46:187–204. doi: 10.1177/002214650504600205. doi:10.1177/002214650504600205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colder C. R., Campbell R. T., Ruel E., Richardson J. L., Flay B. R. A finite mixture model of growth trajectories of adolescent alcohol use: Predictors and consequences. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2002;70:976–985. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.70.4.976. doi:10.1037/0022-006X.70.4.976. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D’Amico E. J., Tucker J. S., Shih R. A., Miles J. N. V. Does diversity matter? The need for longitudinal research on adolescent alcohol and drug use trajectories. Substance Use & Misuse. 2014;49:1069–1073. doi: 10.3109/10826084.2014.862027. do i:10.3109/10826084.2014.862027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dishion T. J., Tipsord J. M. Peer contagion in child and adolescent social and emotional development. Annual Review of Psychology. 2011;62:189–214. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.093008.100412. doi:10.1146/annurev.psych.093008.100412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elder G. H., Jr., Caspi A. Human development and social change: An emerging perspective on the life course. In: Bolger N., Caspi A., Downey G., Moorehouse M., editors. Persons in context: Developmental processes, human development in cultural and historical contexts. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press; 1988. pp. 77–113. [Google Scholar]

- Elliott D. S., Huizinga D., Ageton S. S. Explaining delinquency and drug use. Beverly Hills, CA: Sage; 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Elliott D. S., Menard S., Rankin B., Elliott A., Wilson W. J., Huizinga D. Good kids from bad neighborhoods: Successful development in social context. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Flewelling R. L., Paschall M. J., Ringwalt C. The epidemiology of underage drinking in the United States: An overview. In: Bonnie R. J., O’Connell M. E., editors. Reducing underage drinking: A collective responsibility. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2004. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flory K., Brown T. L., Lynam D. R., Miller J. D., Leukefeld C., Clayton R. R. Developmental patterns of African American and Caucasian adolescents’ alcohol use. Cultural Diversity & Ethnic Minority Psychology. 2006;12:740–746. doi: 10.1037/1099-9809.12.4.740. doi:10.1037/1099-9809.12.4.740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flory K., Lynam D., Milich R., Leukefeld C., Clayton R. Early adolescent through young adult alcohol and marijuana use trajectories: Early predictors, young adult outcomes, and predictive utility. Development and Psychopathology. 2004;16:193–213. doi: 10.1017/s0954579404044475. doi:10.1017/S0954579404044475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Furr-Holden C. D. M., Campbell K. D. M., Milam A. J., Smart M. J., Ialongo N. A., Leaf P. J. Metric properties of the Neighborhood Inventory for Environmental Typology (NIfETy): An environmental assessment tool for measuring indicators of violence, alcohol, tobacco, and other drug exposures. Evaluation Review. 2010;34:159–184. doi: 10.1177/0193841X10368493. doi:10.1177/0193841X10368493. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Furr-Holden C. D. M., Smart M. J., Pokorni J. L., Ialongo N. S., Leaf P. J., Holder H. D., Anthony J. C. The NIfETy method for environmental assessment of neighborhood-level indicators of violence, alcohol, and other drug exposure. Prevention Science. 2008;9:245–255. doi: 10.1007/s11121-008-0107-8. doi:10.1007/s11121-008-0107-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giletta M., Scholte R. H., Prinstein M. J., Engels R. C., Rabaglietti E., Burk W. J. Friendship context matters: Examining the domain specificity of alcohol and depression socialization among adolescents. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2012;40:1027–1043. doi: 10.1007/s10802-012-9625-8. doi:10.1007/s10802-012-9625-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harrop E., Catalano R. F. Evidence-based prevention for adolescent substance use. Child and Adolescent Psychiatric Clinics of North America. 2016;25:387–410. doi: 10.1016/j.chc.2016.03.001. doi:10.1016/j.chc.2016.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haynie D. L., Payne D. C. Race, friendship networks, and violent delinquency. Criminology. 2006;44:775–805. doi:10.1111/j.1745-9125. °2006.00063.x. [Google Scholar]

- Henry D. B., Kobus K., Schoeny M. E. Accuracy and bias in adolescents’ perceptions of friends’ substance use. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2011;25:80–89. doi: 10.1037/a0021874. doi:10.1037/a0021874. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huckle T., Huakau J., Sweetsur P., Huisman O., Casswell S. Density of alcohol outlets and teenage drinking: Living in an alcogenic environment is associated with higher consumption in a metropolitan setting. Addiction. 2008;103:1614–1621. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2008.02318.x. doi:10.1111/j.1360-0443.2008.02318.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ialongo N. S., Werthamer L., Kellam S. G., Brown C. H., Wang S., Lin Y. Proximal impact of two first-grade preventive interventions on the early risk behaviors for later substance abuse, depression, and antisocial behavior. American Journal of Community Psychology. 1999;27:599–641. doi: 10.1023/A:1022137920532. doi:10.1023/A:1022137920532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jackson K. M., Sher K. J. Similarities and differences of longitudinal phenotypes across alternate indices of alcohol involvement: A methodologic comparison of trajectory approaches. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2005;19:339–351. doi: 10.1037/0893-164X.19.4.339. doi:10.1037/0893-164X.19.4.339. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jencks C., Mayer S. E. Inner-city poverty in the United States. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 1990. The social consequences of growing up in a poor neighborhood; pp. 111–186. [Google Scholar]

- Karriker-Jaffe K. J. Areas of disadvantage: A systematic review of effects of area-level socioeconomic status on substance use outcomes. Drug and Alcohol Review. 2011;30:84–95. doi: 10.1111/j.1465-3362.2010.00191.x. doi:10.1111/j.1465-3362.2010.00191.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kosterman R., Hawkins J. D., Guo J., Catalano R. F., Abbott R. D. The dynamics of alcohol and marijuana initiation: Patterns and predictors of first use in adolescence. American Journal of Public Health. 2000;90:360–366. doi: 10.2105/ajph.90.3.360. doi:10.2105/AJPH.90.3.360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuntsche E., Kuendig H., Gmel G. Alcohol outlet density, perceived availability and adolescent alcohol use: A multilevel structural equation model. Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health. 2008;62:811–816. doi: 10.1136/jech.2007.065367. doi:10.1136/jech.2007.065367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LaVeist T. A., Wallace J. M., Jr. Health risk and inequitable distribution of liquor stores in African American neighborhood. Social Science & Medicine. 2000;51:613–617. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(00)00004-6. doi:10.1016/S0277-9536(00)00004-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee C., Mun E. Y., White H. R., Simon P. Substance use trajectories of black and white young men from adolescence to emerging adulthood: A two-part growth curve analysis. Journal of Ethnicity in Substance Abuse. 2010;9:301–319. doi: 10.1080/15332640.2010.522898. doi:10.1080/15332640.2010.522898. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li F., Barrera M., Hops H., Fisher K. J. The longitudinal influence of peers on the development of alcohol use in late adolescence: a growth mixture analysis. Journal of Behavioral Medicine. 2002;25:293–315. doi: 10.1023/a:1015336929122. doi:10.1023/A:1015336929122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lynne-Landsman S. D., Bradshaw C. P., Ialongo N. S. Testing a developmental cascade model of adolescent substance use trajectories and young adult adjustment. Development and Psychopathology. 2010;22:933–948. doi: 10.1017/S0954579410000556. doi:10.1017/S0954579410000556. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Milam A. J., Johnson S. L., Furr-Holden C. D. M., Bradshaw C. P. Alcohol outlets and substance use among high schoolers. Journal of Community Psychology. 2016;44:819–832. doi: 10.1002/jcop.21802. doi:10.1002/jcop.21802. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mudar P., Kearns J. N., Leonard K. E. The transition to marriage and changes in alcohol involvement among black couples and white couples. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 2002;63:568–576. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2002.63.568. doi:10.15288/jsa.2002.63.568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mulia N., Ye Y., Greenfield T. K., Zemore S. E. Disparities in alcohol-related problems among white, black, and Hispanic Americans. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 2009;33:654–662. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2008.00880.x. doi:10.1111/j.1530-0277.2008.00880.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagin D. S. Analyzing developmental trajectories: A semiparametric, group-based approach. Psychological Methods. 1999;4:139–157. doi: 10.1037/1082-989x.6.1.18. doi:10.1037/1082-989X.4.2.139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nelson S. E., Van Ryzin M. J., Dishion T. J. Alcohol, marijuana, and tobacco use trajectories from age 12 to 24 years: Demographic correlates and young adult substance use problems. Development and Psychopathology. 2015;27:253–277. doi: 10.1017/S0954579414000650. doi:10.1017/S0954579414000650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Osgood D. W., Ragan D. T., Wallace L., Gest S. D., Feinberg M. E., Moody J. Peers and the emergence of alcohol use: Influence and selection processes in adolescent friendship networks. Journal of Research on Adolescence. 2013;23:500–512. doi: 10.1111/jora.12059. doi:10.1111/jora.12059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patterson G. R., Reid J. B., Dishion T. J. A social learning approach. IV. Antisocial boys. Eugene, OR: Castalia; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Plybon L. E., Kliewer W. Neighborhood types and externalizing behavior in urban school-age children: Tests of direct, mediated, and moderated effects. Journal of Child and Family Studies. 2001;10:419–437. doi:10.1023/A:1016781611114. [Google Scholar]

- Rankin B. H., Quane J. M. Social contexts and urban adolescent outcomes: The interrelated effects of neighborhoods, families, and peers on African-American youth. Social Problems. 2002;49:79–100. doi:10.1525/sp.2002.49.1.79. [Google Scholar]

- Ross C. E., Mirowsky J. Neighborhood disadvantage, disorder, and health. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 2001;42:258–276. doi:10.2307/3090214. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Royston P., Carlin J. B., White I. R. Multiple imputation of missing values: New features for mim. The Stata Journal. 2009;9:252–264. doi:10.1177/1536867X0900900205. [Google Scholar]

- Ryan S. M., Jorm A. F., Lubman D. I. Parenting factors associated with reduced adolescent alcohol use: A systematic review of longitudinal studies. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry. 2010;44:774–783. doi: 10.1080/00048674.2010.501759. doi:10.1080/00048674.2010.501759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sampson R. J., Raudenbush S. W., Earls F. Neighborhoods and violent crime: A multilevel study of collective efficacy. Science. 1997;277:918–924. doi: 10.1126/science.277.5328.918. doi:10.1126/science.277.5328.918. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skinner M. L., Haggerty K. P., Catalano R. F. Parental and peer influences on teen smoking: Are White and Black families different? Nicotine & Tobacco Research. 2009;11:558–563. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntp034. doi:10.1093/ntr/ntp034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sullivan G. M., Feinn R. Using effect size—or why the P value is not enough. Journal of Graduate Medical Education. 2012;4:279–282. doi: 10.4300/JGME-D-12-00156.1. doi:10.4300/JGME-D-12-00156.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tobler A. L., Komro K. A., Maldonado-Molina M. M. Relationship between neighborhood context, family management practices and alcohol use among urban, multi-ethnic, young adolescents. Prevention Science. 2009;10:313–324. doi: 10.1007/s11121-009-0133-1. doi:10.1007/s11121-009-0133-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Treno A. J., Ponicki W. R., Remer L. G., Gruenewald P. J. Alcohol outlets, youth drinking, and self-reported ease of access to alcohol: A constraints and opportunities approach. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 2008;32:1372–1379. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2008.00708.x. doi:10.1111/j.1530-0277.2008.00708.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wanner B., Vitaro F., Ladouceur R., Brendgen M., Tremblay R. E. Joint trajectories of gambling, alcohol and marijuana use during adolescence: A person- and variable-centered developmental approach. Addictive Behaviors. 2006;31:566–580. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2005.05.037. doi:10.1016/j.addbeh.2005.05.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson W. The truly disadvantaged: The inner city, the under class, and public policy. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press; 1987. [Google Scholar]