Abstract

Background: Although abundant research documented the vulnerability of left-behind children in rural China, little is known about whether early left-behind experiences are linked to their positive psychosocial functioning in later life, as well as the potential protective factors for their psychosocial adjustment.

Purpose: Informed by positive youth development framework and a positive adjustment framework in migrants, the current study compares psychosocial adjustment characterized by self-esteem and prosocial behavior between emerging adults with early left-behind experiences (LB-E) and their counterparts (Non-LB-E). Of importance, this study also examines the potential protective roles of social context (ie, peer support) and individual characteristic (ie, resilience) in psychosocial outcomes among Chinese emerging adults with and without early left-behind experiences.

Methods: A propensity score matching was used to balance the two groups regarding age, gender, socioeconomic status, and potentially traumatic life events. Finally, a total of 182 emerging adults with early left-behind experiences and 182 their counterparts was involved in the current study, who were asked to complete self-report questionnaires.

Results: The results showed that there were no significant differences in self-esteem and prosocial behavior between the two groups. In addition, resilience was found to moderate the link between peer support and self-esteem. Specifically, in the context of higher levels of peer support, emerging adults with higher levels of resilience reported higher levels of self-esteem.

Conclusion: The current study suggests that early left-behind experiences are not an adversity for emerging adults’ positive psychosocial adjustment, and the protective roles of peer support and resilience are highlighted in Chinese emerging adults. Intervention or prevention programs may focus on the enhancement of resilience as well as the quality of peer relationships, shifting away from risk towards positive development models.

Keywords: resilience, left-behind children, peer support, self-esteem, prosocial behavior, emerging adult

Introduction

Based on a recent report released by Ministry of Education (2017), China has been experiencing an unprecedented rural-to-urban migration, as a result of an increasing number of left-behind children in rural China (15 million in 2017).1 Left-behind children involve the children who are under 18 years and are left at home when both or one of their parents migrate to urban areas to work for at least six months.2 While it is well documented that left-behind children in rural China are disadvantaged in terms of psychosocial and academic functioning,3,4 there are still some gaps in the literature: (1) whether early left-behind experiences are linked to psychosocial functioning in later life, especially for emerging adulthood; (2) extensive studies focus on negative outcomes of left-behind populations,5 however, how about the positive psychosocial functioning of this vulnerable group; and (3) little is known about the protective factors for psychosocial adjustment in this vulnerable group.

Guided by positive youth development framework (PYD) and a positive adaptation perspective of migrants,6,7 this study aimed to answer these research questions: (1) to compare psychosocial adjustment operationalized by self-esteem and prosocial behavior between emerging adults with early left-behind experience (LB-E) and their counterparts (non-LB-E); and (2) to ascertain the direct and interactive effects of peer support and resilience on psychosocial adjustment in emerging adults with and without early left-behind experiences. To answer these research questions, it may shed light on the roles of peer support and resilience in left-behind populations. Most importantly, the current study may provide critical insights into the targeted intervention or prevention programs for emerging adults with early left-behind experiences.

Psychosocial adjustment of emerging adults

During life transition - emerging adulthood, it is characterized by changes and explorations in love, work and worldviews (eg, living independently, engagement in romantic relations, job-seeking and pursuing higher education).8 In the last decade, indeed, a growing body of research has pointed out psychosocial difficulties during this period, describing the complex challenges that emerging adults face and the patterns of adjustment that follow from their ambitions.9 In line with the vulnerability of emerging adults, the current study provides more insights into psychosocial adjustment in this period.

Psychosocial adjustment is a multidimensional construct involving subjective, emotional, and cognitive evaluation of quality of life.10 Despite several years of intense research, there continues to be heterogeneity in how and what should be assessed when addressing psychosocial adjustment. Deeply rooted in Confucianism, Chinese cultures attach special importance to social harmony, mutual help as well as positive self-worth.11 Informed by PYD and a positive adaptation perspective in migrants,6,7 as well as these traditional Chinese cultural values, the current study defines psychosocial adjustment from a positive perspective, namely self-esteem and prosocial behavior. Also, suggested by previous research, this conceptualization allows us to obtain a more nuanced measure of psychosocial adjustment encompassing both ‘internal psychological approach’ (ie, subjective self-evaluation) and 'external social approach' (ie, self-motived helping and sharing behaviors to others) of positive adjustment.12

Self-esteem involves the evaluation of an individual’s subjective worth as a person.13 Prior research showed that higher levels of self-esteem can facilitate the success of work performance or school outcomes, and reduce the risk for mental health problems.14 Moreover, identity and self-evaluation are the critical developmental task during the transition to adulthood.10 In view of these findings, a better understanding of self-esteem during emerging adulthood may be critical. On the other side, prosocial behavior refers to self-motivated behavior that benefits another person, including helping, sharing, comforting, guiding, rescuing and defending others.15 Previous studies showed that prosocial behavior is positively associated with several positive outcomes, such as academic performance and social competence.16 In light of these empirical implications, it is important to regard prosocial behavior as one of the indicators for psychosocial adjustment among emerging adults.

Although extensive studies showed that positive psychosocial adjustment is, indeed, crucial to emerging adults, little is known about whether early left-behind experiences in rural China is a risk factor for psychosocial functioning of later life. Moreover, the knowledge about the protective factors in psychosocial adjustment is still lacking. Followed by a risk and resilience ecological framework, social contexts are regarded as one of the essential protective aspects.7 Given the majority of time emerging adults spend in their affiliated peer groups, the current study focuses on supportive peer contexts, namely peer support.

Peer support and psychological adjustment

Peer support is one of the important resources of social support which refers to a subjective evaluation of the quality of peer networks.17 Abundant studies showed that peer support is an important protective factor for ethnically diverse college students’ psychosocial adjustment in terms of depressive symptoms, somatization, and loneliness.18 Similarly, a recent study showed that positive peer relationships can facilitate adjustment operationalized by internalizing problems, academic grades and attachment to the school for emerging adults with ADHD (Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder).19 In terms of self-esteem, the evidence from previous research showed increased social support from friends, but not from family, predicts positive socioemotional adjustment including self-esteem in emerging adults.20 With regard to prosocial behavior, previous studies found that peer relations influence youth adult’s helping and sharing behaviors in adolescence, suggesting that prosocial behavior may gradually increase after prosocial feedback from peers.21

Indeed, extensive research has shown that supportive peer relationships contribute to positive psychosocial adjustment in emerging adults. However, the knowledge about the role of peer support in emerging adults with early left-behind experiences is still scarce. Moreover, little is known about the interactive effect between peer support and individual characteristic in this vulnerable group. Followed by a risk and resilience framework, we proposed that resilience may serve as a potential moderator in the association between peer support and psychosocial outcomes.7

The moderating role of resilience

Resilience refers to effective coping and adaptation in the face of loss, hardship, or adversity.22 Previous studies showed that resilience is an effective protective factor in the unfavorable populations. For example, the study found that resilience resources attenuate the association between adverse childhood experiences (ie, abuse, neglect, and household dysfunction in childhood and adolescence) and later health outcomes in adulthood.23 Similarly, a recent systematic review revealed that resilience factors can reduce mental health problems of young adults who experienced childhood adversity.24 In terms of Chinese left-behind children, prior research showed that resilience can moderate the link between social support and loneliness. Specifically, in the context of lower levels of social support, higher levels of resilience are a protective factor for loneliness.25

While extensive studies documented the buffering role of resilience in the negative outcomes, little is known about whether the interactive effect between peer support and resilience explains positive outcomes in emerging adults with and without early left-behind experiences.

The present study

To sum up, the current study has two main goals: (1) to compare self-esteem and prosocial behavior between LB-E and their non-LB-E counterparts in China; and (2) to examine the moderating role of resilience in the association between peer support and psychosocial adjustment in emerging adults with and without early left-behind experiences.

Specifically, we tested the following hypotheses (H):

(H1) LB-E report lower levels of self-esteem and prosocial behavior compared to their non-LB-E counterparts.

(H2) Emerging adults reporting higher quality of peer support and higher levels of resilience score higher on self-esteem and prosocial behavior compared with their peers reporting lower levels of resilience (ie, two-way interaction; H2a), and this association is stronger for emerging adults with early left-behind experiences (ie, three-way interaction; H2b).

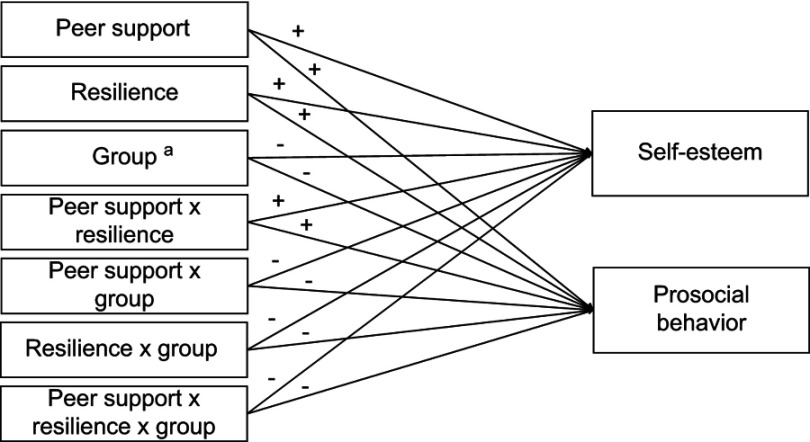

A graphical representation of the hypothesized model is depicted in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Hypothesized model. Age, gender, socioeconomic status (SES) and potentially traumatic life events (PTE) were considered as potential covariates. aCoded as 1= emerging adults with early left-behind experiences, 0= emerging adults without early left-behind experiences. + refers to positive association and - refers to negative association.

Method

Participants and procedure

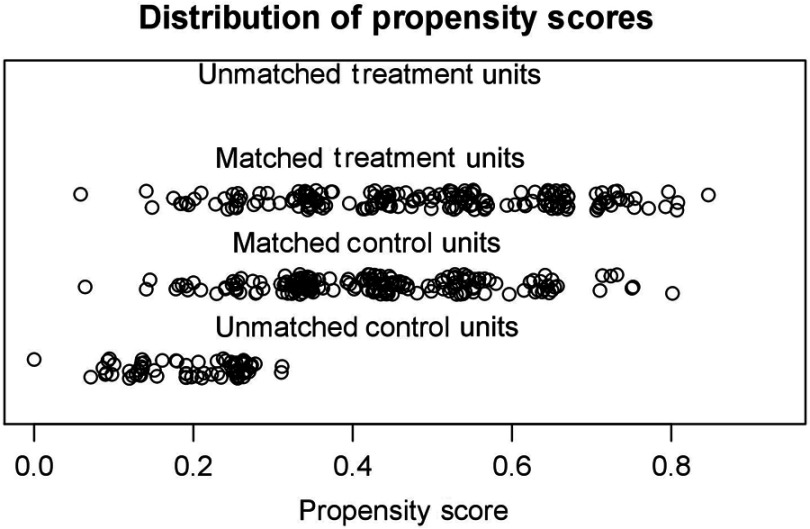

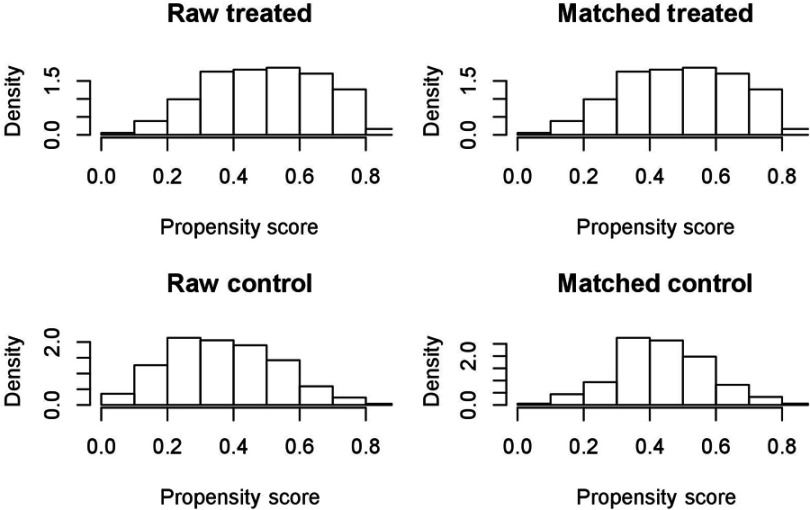

To balance the two groups (ie, LB-E and non-LB-E), we performed a propensity score matching analysis in terms of age, gender, socioeconomic status (SES), and potentially traumatic life events (PTE), with a ratio of one-to-one. Finally, 182 emerging adults from non-LB-E group were extracted to match with the LB-E group. The visualized figures showed that the matching between the two groups fit well (see Appendix A).

Finally, participants in this study involved 182 LB-E (45.6% girls; 55.4% left-behind by one parent) and 182 non-LB-E (51.1% girls) Chinese emerging adults aged from 18 to 22 years (Mage =19.29; SD =0.93), who were attending 1st and 2nd grades in the two public colleges in North Mainland of China. We excluded the emerging adults from 3rd and 4th grades since they are highly engaged in job-seeking and preparation for post-graduate entrance examination. The majority of fathers (47.3%) and mothers (43.4%) had just completed middle school. In addition, 94.5% of the participants belonged to the Han ethnic group, which is the majority ethnic group in China, in order to control the potential multiethnic influence.

Prior to data collection, ethical approval for the study was obtained by Beijing Normal University, and this study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. The experimenter contacted the public colleges located in North Mainland of China. After obtaining permission from school principals, informed consent forms were given to emerging adults who attended the classes. After confirming written informed consent participants provided, emerging adults were recruited in the current study. Overall, the participation rate was 95%, which is in line with previous studies conducted in a Chinese population.26 During school hours, a trained experimenter provided standardized instructions, and adults were asked to complete the online questionnaires during a 25-min period in the classroom.

Measures

Peer support was measured by the four-item subscale of the Multidimensional Scale of Perceived Social Support (MSPSS).27 One of the examples is “I have friends with whom I can share my joys and sorrows.” Participants were asked to rate each item ranging from 1 (very strongly disagree) to 7 (very strongly agree). The average of four items was calculated to yield the score of peer support, with a higher score indicating higher levels of the quality of peer relationships. Previously, the scale was utilized in a Chinese population and showed a good internal consistency.28 In the current study, Cronbach alphas were 0.94 for LB-E and 0.92 for non-LB-E, respectively.

Resilience was measured by the 25-item Connor–Davidson Resilience Scale (CD-RISC), which was previously validated in Chinese populations by Yu and Zhang.22,29 One of the examples is “I am able to adapt when changes occur.” Participants rated items on a Likert-type scale ranging from 0 (not true at all) to 4 (true nearly all the time), and higher scores reflect greater resilience. Prior research signified a good internal consistency of this scale in a Chinese population.29 In the current study, Cronbach alphas were 0.97 for LB-E and 0.97 for non-LB-E, respectively.

Self-esteem was assessed by the 10-item Rosenberg Self-esteem Scale (RSES), which was validated in a Chinese population.30,31 One of the examples is “I am able to do things as well as most other people.” Each item was rated on a four-point Likert-type scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 4 (strongly agree). The average score of 10 items was obtained to reflect global self-esteem in emerging adults. In the current study, Cronbach’s alphas were 0.82. for LB-E, and 0.83 for non-LB-E, respectively.

Prosocial behavior was measured via the 15-item Prosocial Behavior Scale (PBS), which was developed for Chinese adolescents by Kou and Zhang.32 One of the examples is that “I like participating in social activities for public good.” Participants were asked to rate each item ranging from 1 (Definitely does not apply to me) to 7 (Definitely applies to me). The average score of 15 items was calculated, with a higher score indicating higher levels of prosocial behavior. According to previous research among Chinese adolescents, this scale exhibited a good internal consistency.33 In the current study, Cronbach alphas were 0.95 for LB-E and 0.96 for non-LB-E, respectively.

Control variables

Age, Gender, and SES. SES was measured by the sum of paternal and maternal educational levels. With regard to parental education, four categories were available: (1) middle school graduation or lower, (2) high school graduation, (3) bachelor’s degree graduation, and (4) master’s degree graduation or higher.

PTE were assessed by the 25-item Lifetime Exposure to Traumatic Events, which assesses the exposure to a wide range of traumatic events in an undergraduate-level population.34 The prevalence of exposure to traumatic events (eg, relatives passing away, being bullied at school and being in a car accident) was included and prior research revealed a good internal consistency of this scale.34 All the items were averaged to yield the score of PTE, with the higher score indicating higher levels of traumatic experiences. In the current study, Cronbach alphas were 0.94 for LB-E and 0.95 for non-LB-E, respectively.

Data analyses

Data analyses were performed using R software.35 Thirty-three cases were excluded due to the age range (ie, less than 18 years old). Due to the reminder of inserting any missing values in the online questionnaire system, the current study did not identify any influential missing cases (more than 20%).

Means and standard deviations for continuous variables were used for descriptive statistics, and Pearson’s correlations were used to evaluate the associations among the study variables. Multivariate Analysis of Variance (MANOVA) was used to examine the group differences in self-esteem and prosocial behavior. Moreover, path analysis was conducted to test the moderating role of resilience in the expected associations between peer support and psychosocial adjustment in emerging adults with and without early left-behind experiences.

Results

Descriptive statistics

Means and standard deviations for study variables and bivariate correlations are reported in Table 1, separately for LB-E and non-LB-E.

Table 1.

Descriptive statistics and bivariate correlations of study variables between LB-E and non-LB-E

| LB-E (n=182) | Non-LB-E (n=182) | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | SD | Range | Mean | SD | Range | |||||||||

| 1. Peer support | 5.14 | 1.25 | 1–7 | 5.30 | 1.19 | 1–7 | − | 0.58*** | 0.44*** | 0.61*** | 0.10 | 0.12 | 0.09 | −0.13 |

| 2. Resilience | 2.37 | 0.77 | 0–4 | 2.41 | 0.79 | 0–4 | 0.52*** | − | 0.63*** | 0.72*** | 0.08 | 0.20** | 0.09 | −0.13 |

| 3. Self-esteem | 2.92 | 0.43 | 1–4 | 2.95 | 0.46 | 1–4 | 0.49*** | 0.68*** | − | 0.52*** | 0.07 | 0.17** | 0.12 | −0.08 |

| 4. PB | 5.04 | 1.07 | 1–7 | 5.04 | 1.16 | 1–7 | 0.47*** | 0.63*** | 0.52*** | − | 0.12 | 0.09 | 0.10 | −0.05 |

| 5. Age | 19.37 | 0.99 | 18–22 | 19.20 | 0.87 | 18–22 | −0.11 | −0.01 | −0.09 | 0.07 | − | 0.20** | 0.01 | −0.02 |

| 6. Gender | − | − | 1–2 | − | − | 1–2 | 0.12 | 0.05 | 0.06 | 0.14 | 0.00 | − | −0.14 | −0.17* |

| 7. SES | 3.81 | 1.41 | 2–8 | 4.16 | 1.39 | 2–8 | 0.01 | −0.08 | −0.01 | −0.04 | −0.18* | 0.07 | − | −0.07 |

| 8. PTE | 0.60 | 0.74 | 0–5 | 0.62 | 0.79 | 0–5 | 0.08 | 0.01 | −0.14 | 0.02 | 0.17* | −0.05 | −0.09 | − |

Notes: Correlation coefficients displayed above the diagonal are for the non-LB-E group, below for the LB-E group. *p< 0.05 **p< 0.01 ***p< 0.001.

Abbreviations: LB-E, emerging adults with early left-behind experiences; non-LB-E, emerging adults without early left-behind experiences; PB, prosocial behavior; SES, socioeconomic status; PTE, potentially traumatic life events.

As shown in Table 1, the results indicated that peer support and resilience were each significantly and positively associated with self-esteem and prosocial behavior in both groups.

MANOVA indicated that there were no significant differences in self-esteem (F (1, 358)=0.09, p=0.76, η2p=0.001) and prosocial behavior (F (1, 358)=0.001, p=0.98, η2p=0.001) between LB-E and non-LB-E.

Path analyses

Path analyses for observed variables were used to evaluate the contributions of peer support and resilience to self-esteem and prosocial behavior in both groups. In this analysis, gender, age, SES, and PTE were considered as control variables, since previous research has shown that these variables are related to self-esteem and prosocial behavior. For example, a recent study revealed that higher levels of SES are negatively associated with prosocial behavior in Chinese adolescents.36

Our hypothesized model was tested using the R package lavaan.35,37 Direct and interactive path coefficients from peer support to self-esteem and prosocial behavior were estimated using the maximum likelihood method, with a single observed score (ie, centered mean score) for each variable. Also, the correlation (r =0.52, p<0.001) between self-esteem and prosocial behavior was controlled in the model. To test for moderation, products between centered variables were computed and included in the model as interaction terms. First, the baseline model was tested (see Figure 1). In addition to the main effects of peer support, resilience, and group membership (LB-E vs non-LB-E), we also included two- and three-way interactions among these variables. The inspection of path coefficients showed many nonsignificant links between interaction terms and outcome variables. For the sake of parsimony, these links were removed, and the model was re-evaluated step by step. The final model, presented in Figure 2, fit the data well, χ2(3)=3.27, p=0.35; Tucker–Lewis Index (TLI)=0.99; Comparative Fit Index (CFI)=0.99; Standardized Root Mean Square Residual (SRMR)<0.01. In this model, all estimated coefficients were statistically significant with sufficient effect sizes. The R2 for the endogenous variables indicated that the model accounted for 45.4% of the variance in self-esteem, 51.0% in prosocial behavior.

Figure 2.

Structural path diagram of the final model. aCoded as 1= emerging adults with early left-behind experiences, 0= emerging adults without early left-behind experiences. Only significant paths are shown with p<0.05.

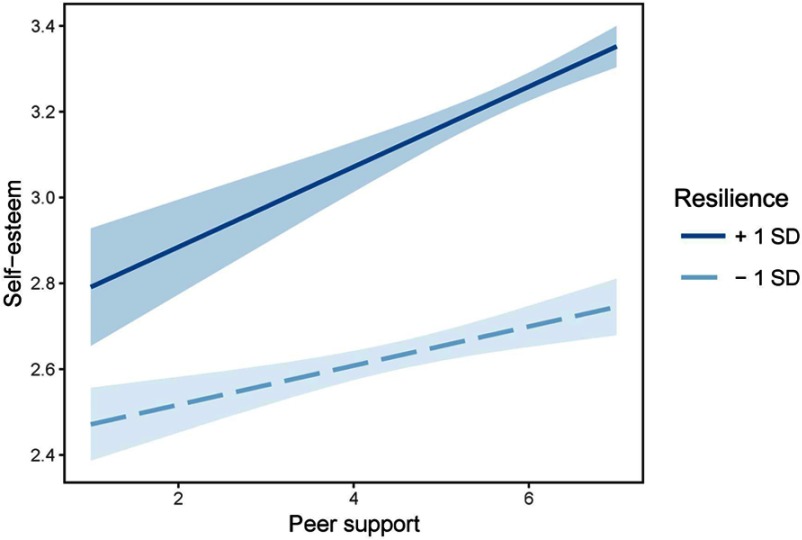

As shown in Figure 2, peer support and resilience were each significantly and positively associated with self-esteem and prosocial behavior. Furthermore, the interaction effect of peer support and resilience was significantly positively associated with self-esteem. Simple slope analysis revealed that the association between peer support and self-esteem was stronger at higher (B =0.09, SE =0.02, t=4.25, p<0.001) than at lower levels of resilience (B =0.05, SE =0.02, t=2.59, p<0.01). Specifically, in the context of higher levels of peer support, emerging adults with higher levels of resilience reported higher levels of self-esteem (see Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Interactive effect of peer support and resilience on self-esteem. Resilience was divided into two levels based on mean: low = mean – 1 SD, high = mean +1 SD. Light blue bands represent 95% confidence intervals.

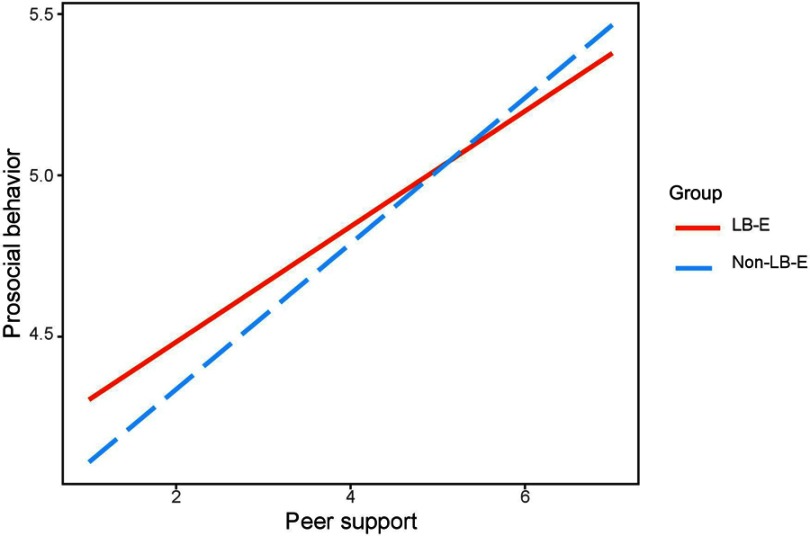

In addition, peer support interacted with group membership to explain the variation in prosocial behavior. Simple slope analysis revealed that the positive association between peer support and prosocial behavior was stronger in the non-LB-E group (B =0.29, SE =0.05, t=5.27, p<0.001), compared with the LB-E group (B =0.17, SE =0.05, t=3.27, p<0.001). To be specific, in the context of lower levels of peer support, emerging adults with early left-behind experiences reported higher levels of prosocial behavior (see Figure 4). No other two- or three-way interactions were identified.

Figure 4.

Interactive effect of peer support and group membership on prosocial behavior.

Abbreviations: LB-E, emerging adults with early left-behind experiences; Non-LB-E, emerging adults without early left-behind experiences.

Discussion

The main goal of this study was to compare self-esteem and prosocial behavior between LB-E and non-LB-E. Also, the potential protective roles of peer support and resilience were examined in both groups. Indeed, while extant research suggests that left-behind children are disadvantaged in terms of academic and psychological functioning, little is known about whether early left-behind experiences influence later life’s positive psychosocial functioning. The current findings suggest that early left-behind experiences are not a disadvantage for positive psychosocial adjustment in Chinese emerging adults. Of importance, resilience was found to enhance the levels of self-esteem in the context of higher levels of peer support. Moreover, in the context of negative peer support, emerging adults with early left-behind experiences showed higher levels of prosocial behavior.

Our first purpose was to compare the group differences in self-esteem and prosocial behavior. Against the hypothesis, the results showed there was no significant difference in self-esteem between the two groups, implying that early left-behind experiences may not influence individual’s subject evaluation in later life. Consistent with previous studies conducted by left-behind children in South Asia context, less significant results were recognized in self-esteem.38 Although left-behind experiences in rural China are an unfavorable condition for children and adolescents, the negative effect of these experiences may be less influenced in later life, such as emerging adulthood. Indeed, emerging adults are more engaged in peer and romantic relationships, leaving their home to start a college life in a new urban context, fulfilled with educational resources and supportive social contexts. As such, these resources may help emerging adults with early left-behind experiences to improve their self-evaluation and self-worth.

Similarly, no significant difference was found in prosocial behavior between the two groups, suggesting that early left-behind experiences may not disturb emerging adults’ self-motivated helping behaviors. One possible explanation is that helping behaviors are much influenced by individual stable traits and contextual cues from peers and teachers.39 However, emerging adults start to live outside of their parents and are highly engaged in peer and romantic relations. Thus, prosocial behavior is less influenced by parental migration and parenting. Another explanation is in line with previous research that emerging adults’ prosocial behavior increases linearly over time, which is regardless of early adverse experiences, since emerging adults are more involved in social interactions and socialization.40

Our second purpose was to investigate the protective roles of peer support and resilience in psychosocial functioning. Consistent with the hypothesis, our results showed that resilience could moderate the link between peer support and self-esteem. Specifically, in the context of higher levels of peer support, higher levels of resilience were found to enhance self-esteem. This pattern is congruent with previous research that higher levels of resilience interact with family resources to explain emotional adaption in rural-to-urban migrants.41 Also, our findings confirmed a risk and resilience perspective that the interaction between social contexts and personal traits can explain the variation in positive psychosocial adjustment.7 One possible explanation is ascribed to Chinese cultural values that social relations and perseverance in the face of adversity are highly emphasized. In the college context, peer relations, indeed, are influential in individuals’ self-evaluation. Moreover, when emerging adults encounter difficulties, personal resilience as well as peer support can buffer these negative effects to promote individual perception of self-worth.

However, our study did not find the interactive effect between peer support and resilience in prosocial behavior. One possible explanation is that humanity and mutual help are underscored in Chinese cultures, and the positive association between peer support and prosocial behavior is independent of the levels of resilience. Also, consistent with recent findings, other resilience-related factors (eg, grit) but not psychological resilience can enhance the levels of prosocial behavior. For example, Lan, Marci, and Moscardino (2019) found in the context of higher levels of parental autonomy support, higher levels of grit can promote prosocial behavior in Chinese adolescents.36

Also, our study failed to find the three-way interactions among peer support, resilience, and early left-behind experiences status. The results suggest that the protective effect of resilience in the association between peer support and psychosocial adjustment is independent of parental migration. One possible explanation is that the two groups were relatively homogeneous in terms of contextual background (ie, SES and PTE). Also, the role of peer contexts during emerging adulthood is prioritized, instead of parents. Thus, the influence of parental migration and family composition may be weakened. Moreover, in line with the current findings, early left-behind experiences are not a disadvantage for positive psychosocial adjustment in emerging adults. Relatedly, the significant two-way interaction between peer support and group membership supported that in the context of lower levels of peer support, LB-E showed higher levels of prosocial behavior.

Limitations and implications

While our study extends prior research by documenting the role of early left-behind experiences in positive psychosocial adjustment, and the promotive role of resilience in positive outcomes among Chinese emerging adults, a number of limitations should be considered when interpreting the results.

First, the cross-sectional and correlational design does not allow to establish causality. It may be, for example, that higher levels of psychosocial adjustment lead to a better quality of peer relationship. Also, the present study relies on a retrospective report, which may yield inaccurate results. Future studies may consider a longitudinal design that is warranted to confirm the current results. Second, the current study does not differentiate the residence (rural vs urban during their early life) of emerging adults from the non-LB-E group. As individuals living in urban areas hold more educational and social resources than those in rural areas, future studies may make a three-group comparison (ie, emerging adults with early left-behind experiences, emerging adults without early left-behind experiences reside in rural areas during early life; emerging adults without early left-behind experiences reside in urban areas during early life) to disentangle this effect. Third, the details of early left-behind experiences (eg, the duration of being left-behind children in rural China, the frequency of contacting with their parents) are lacking in the current study, which may covariate the current results. Future studies are warranted to include these details to confirm the current findings.

To conclude, the present study highlights early left-behind experiences are not an adversity for emerging adults’ positive psychosocial adjustment. Of importance, the promotive roles of peer support and resilience in positive psychological functioning in Chinese emerging adults are confirmed. From an applied perspective, the present study suggests that both LB-E and non-LB-E may benefit from targeted school activities or interventions aimed at boosting positive peer relations and resilience. In particular, educators and practitioners may organize group cooperation activities to elevate the quality of peer relations and to reduce the discrepancies. In the face of difficulties, effective coping and adaptation are practiced to approach to the targeted goals that are set up at the beginning of the activities.

Supplementary materialsAppendix A.

Propensity score matching analysis using the R package MatchIt was adopted to match the two groups regarding age, gender, socioeconomic status and potentially traumatic life events (PTE) (Randolph, Falbe, Manuel, & Balloun, 2014). Nearest neighbor method and one-to-one matching ratio were implemented. Namely, each emerging adult with early left-behind experiences was matched with one emerging adult without early left-behind experiences.

The results showed that the matching fit well in the current study. According to jitter plot where each circle represents a case’s propensity score (see Figure S1), the absence of cases in the uppermost stratification indicated that there were no unmatched subjects from the LB-A group. The middle stratification showed the close match between the LB-A group and the non-LB-A group. The downmost stratification showed the unmatched non-LB-A units, which were not used in any follow-up analyses. Moreover, histogram plot showed that the distribution between LB-A and non-LB-A group after matching was quite similar (see Figure S2). To sum up, the visualized figures showed that the matching was acceptable. The final analytical sample consisted of 364 individuals, with 182 emerging adults in the LB-E group and 182 emerging adults in the non-LB-E group.

Figure S1.

Jitter plot for matching the LB-E group and non-LB-E group. Treatment units = LB-E group, control units = non-LB-E group.

Figure S2.

Histogram plot for matching the LB-A group and non-LB-A group. Raw Treated = raw LB-E group, Raw Control = raw non-LB-E group, Matched Treated = matched LB-E group, Matched Control = matched non-LB-E group.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- 1.National Health and Family Planning Commission. Report on China’s Migrant Population Development. Beijing: China Population Press; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wang X, Ling L, Su H, et al. Self-concept of left-behind children in China: A systematic review of the literature. Child Care Health Dev. 2015;41(3):346–355. doi: 10.1111/cch.12172 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wen M, Lin D. Child development in rural China: children left behind by their migrant parents and children of nonmigrant families. Child Dev. 2012;83(1):120–136. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2011.01698.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Liang Y, Wang L, Rui G. Depression among left-behind children in China. J Health Psychol. 2017;22(14):1897–1905. doi: 10.1177/1359105316676333 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hu H, Lu S, Huang CC. The psychological and behavioral outcomes of migrant and left-behind children in China. Child Youth Serv Rev. 2014;46:1–10. doi: 10.1016/j.childyouth.2014.07.021 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Catalano RF, Berglund ML, Ryan JA, et al. Positive youth development in the United States: research findings on evaluations of positive youth development programs. Ann Am Acad Polit Ss. 2014;591(1):98–124. doi: 10.1177/0002716203260102 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Suárez-Orozco C, Motti-Stefanidi F, Marks A, Katsiaficas D. An integrative risk and resilience model for understanding the adaptation of immigrant-origin children and youth. Am Psychol. 2018;73(6):781–796. doi: 10.1037/amp0000265 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Arnett JJ. Emerging adulthood: A theory of development from the late teens through the twenties. Am Psychol. 2000;55(5):469. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.55.5.469 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Schulenberg JE, Zarrett NR. Mental Health during Emerging Adulthood: Continuity and Discontinuity in Courses, Causes, and Functions. Washington, DC, US: American Psychological Association; 2006:135–172. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Schwartz SJ, Beyers W, Luyckx K, et al. Examining the light and dark sides of emerging adults’ identity: a study of identity status differences in positive and negative psychosocial functioning. J Youth Adolescence. 2011;40(7):839–859. doi: 10.1007/s10964-010-9606-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hwang KK. Foundations of Chinese Psychology: Confucian Social Relations. New York: Springer; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lindsey EW, Colwell MJ, Frabutt JM, et al. Mother-child dyadic synchrony in European American and African American families during early adolescence: relations with self-esteem and prosocial behavior. Merrill-Palmer Q J DevPsychol. 2008;54(3):289–315. doi: 10.1353/mpq.0.0003 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chung JM, Robins RW, Trzesniewski KH, et al. Continuity and change in self-esteem during emerging adulthood. J Pers Soc Psychol. 2014;106(3):469–483. doi: 10.1037/a0035135 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sowislo JF, Orth U. Does low self-esteem predict depression and anxiety? A meta-analysis of longitudinal studies. Psychol Bull. 2013;139(1):213–240. doi: 10.1037/a0028931 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Eisenberg N, Fabes RA, Spinrad TL. Prosocial development. In: Eisenberg N, Damon W, Lerner RM, editors. Handbook of child psychology. Vol. 3. Social, emotional and personality development. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley; 2006: 646–718. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Caprara GV, Barbaranelli C, Pastorelli C, Bandura A, Zimbardo PG. Prosocial foundations of children’s academic achievement. Psychol Sci. 2000;11(4):302–306. doi: 10.1111/1467-9280.00260 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dennis JM, Phinney JS, Chuateco LI. The role of motivation, parental support, and peer support in the academic success of ethnic minority first-generation college students. J Coll Stud Dev. 2005;46(3):223–236. doi: 10.1353/csd.2005.0023 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Juang L, Ittel A, Hoferichter F, Gallarin M. Perceived racial/ethnic discrimination and adjustment among ethnically diverse college students: family and peer support as protective factors. J Coll Stud Dev. 2016;7(4):380–394. doi: 10.1353/csd.2016.0048 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Khalis A, Mikami AY, Hudec KL. Positive peer relationships facilitate adjustment in the transition to university for emerging adults with ADHD symptoms. Emer Adulth. 2018;6(4):243–254. doi: 10.1177/2167696817722471 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Friedlander LJ, Reid GJ, Shupak N, Cribbie R. Social support, self-esteem, and stress as predictors of adjustment to university among first-year undergraduates. J Coll Stud Dev. 2007;48(3):259–274. doi: 10.1353/csd.2007.0024 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.van Hoorn J, van Dijk E, Meuwese R, et al. Peer influence on prosocial behavior in adolescence. J Res Adolesc. 2016;26(1):90–100. doi: 10.1111/jora.12173 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Connor KM, Davidson JT. Development of a new resilience scale: the Connor-Davidson resilience scale (CD-RISC). Depress Anxiety. 2003;18(2):76–82. doi: 10.1002/da.10113 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gouin JP, Caldwell W, Woods R, Malarkey WB. Resilience resources moderate the association of adverse childhood experiences with adulthood inflammation. Ann Behav Med. 2017;51(5):782–786. doi: 10.1007/s12160-017-9891-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fritz J, de Graaff AM, Caisley H, Van AL, Wilkinson PO. A systematic review of amenable resilience factors that moderate and/or mediate the relationship between childhood adversity and mental health in young people. Front Psychiatry. 2018;9. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2018.00230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ai H, Hu J. Psychological resilience moderates the impact of social support on loneliness of “left-behind” children. J Health Psychol. 2016;21(6):1066–1073. doi: 10.1177/1359105314544992 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lan X, Scrimin S, Moscardino U. Perceived parental guan and school adjustment among Chinese early adolescents: the moderating role of interdependent self-construal. J Adolesc. 2018;71:18–27. doi: 10.1016/j.adolescence.2018.12.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zimet GD, Dahlem NW, Zimet SG, Farley GK. The multidimensional scale of perceived social support. J Pers Assess. 1988;52(1):30–41. doi: 10.1207/s15327752jpa5201_2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kong F, Zhao J, You X. Emotional intelligence and life satisfaction in Chinese university students: the mediating role of self-esteem and social support. Pers Indivi Differ. 2012;53(8):1039–1043. doi: 10.1016/j.paid.2012.07.032 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Yu X, Zhang J. Factor analysis and psychometric evaluation of the connor-davidson resilience scale (CD-RISC) with chinese people. Soc Behav Pers. 2007;35(1):19–30. doi: 10.2224/sbp.2007.35.1.19 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rosenberg M. Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale. Vol. 61 Acceptance and Commitment Therapy, Measures Package. New York; 1965:52. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Du H, King RB, Chi P. The development and validation of the relational self‐esteem scale. Scand J Psychol. 2012;53(3):258–264. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9450.2012.00946.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kou Y, Zhang Q. Conceptual representation of early adolescents’ prosocial behavior. Sociological Stud. 2006;5:169–187. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Yang Y, Li P, Fu X, Kou Y. Orientations to happiness and subjective well-being in Chinese adolescents: the roles of prosocial behavior and internet addictive behavior. J Happiness Stud. 2017;18(6):1747–1762. doi: 10.1007/s10902-016-9794-1 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Frazier P, Anders S, Perera S, et al. Traumatic events among undergraduate students: prevalence and associated symptoms. J Couns Psychol. 2009;56(3):450–460. doi: 10.1037/a0016412 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 35.R Core Team. R: A language and environment for statistical computing. Vienna, Austria: R Foundation for Statistical Comuti; 2017; Available from: http://www.R-project.org/. Accessed September 27, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lan X, Marci T, Moscardino U. Parental autonomy support, grit, and psychological adjustment in Chinese adolescents from divorced families. J Fam Psychol. 2019;33(1):1–9. doi: 10.1037/fam0000436 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rosseel Y. lavaan : an R package for structural equation. J Stat Softw. 2012;48(2):1–36. doi: 10.18637/jss.v048.i02 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Graham E, Jordan LP. Migrant parents and the psychological well-being of left-behind children in Southeast Asia. J Marriage Fam. 2011;73(4):763–787. doi: 10.1111/j.1741-3737.2011.00844.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wentzel KR, Filisetti L, Looney L. Adolescent prosocial behavior: the role of self-processes and contextual cues. Child Dev. 2007;78(3):895–910. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2007.01039.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Crocetti E, Moscatelli S, Van GJ, et al. The interplay of self‐certainty and prosocial development in the transition from late adolescence to emerging adulthood. Eur J Personal. 2016;30(6):594–607. doi: 10.1002/per.2084 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Huang S, Han M, Sun L, et al. Family socioeconomic status and emotional adaptation among rural‐to‐urban migrant adolescents in China: the moderating roles of adolescent’s resilience and parental positive emotion. Int J Psychol. 2018. doi: 10.1002/ijop.12499 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]