Abstract

Plasma cholesterol levels of high-density lipoproteins (HDL) have been associated with cardioprotection for decades. However, there is an evolving appreciation that this lipoprotein class is highly heterogeneous with regard to composition and functionality. With the advent of advanced lipid-testing techniques and methods that allow both the quantitation and recovery of individual particle populations, we are beginning to connect the functionality of HDL subspecies with chronic metabolic diseases. In this review, we examine type 2 diabetes (T2D) and explore our current understanding of how obesity, insulin resistance, and hyperglycemia affect, and may be affected by, HDL subspeciation. We discuss mechanistic aspects of how insulin resistance may alter lipoprotein profiles and how this may impact the ability of HDL to mitigate both atherosclerotic disease and diabetes itself. Finally, we call for more detailed studies examining the impact of T2D on specific HDL subspecies and their functions. If these particles can be isolated and their compositions and functions fully elucidated, it may become possible to manipulate the levels of these specific particles or target the protective functions to reduce the incidence of coronary heart disease.

Keywords: high-density lipoprotein, lipids, type 2 diabetes, lipoprotein, lipoprotein subspecies

LOOKING BEYOND HIGH-DENSITY LIPOPROTEIN CHOLESTEROL

From the Framingham Heart Study in the 1970s1 to the Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities (ARIC) study 3 decades later,2 epidemiologic studies have consistently shown that low serum high-density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL-C) is a strong, independent risk factor for coronary heart disease (CHD). Indeed, the risk of CHD increases by 3% in men and 2% in women with each 1 mg/dL drop in HDL-C.3 Furthermore, numerous animal model studies have shown that raising HDL-C by infusion or overexpression of the major HDL protein, apolipoprotein AI (apoAI), reduces atherosclerosis. Thousands of in vitro studies have also demonstrated HDL properties that are predicted to be antiatherogenic. This underpins the long-held assertion that HDL, as quantified by its cholesterol content, is an active cardioprotective entity.

However, this dogma has hit some major speed bumps in the last decade. Pharmacological interventions targeting HDL-C have not produced the expected reduction in coronary events despite the 2- to 3-fold increase in HDL-C.4–9 Additionally, Mendelian randomization studies have not supported the hypothesis that HDL-C is in the causal pathway of CHD.10 These results are discordant with human epidemiology, leading some to conclude that HDL-C is a bystander, a nonfunctional secondary marker of a more integral beneficial pathway. Alternatively, it has been argued that HDL-C shows a consistent but weak correlation with cardioprotection because the cholesterol portion of HDL does not fully reflect the functionality of all particle types in the HDL family. Indeed, cholesterol accounts for only about 20% of total HDL mass, and there is ample evidence that potentially important HDL subspecies contain little cholesterol.11,12 Pre-beta HDL, for example, is poorly lipidated but promotes efficient lipid efflux from cells.11 All this has led to the idea that specific HDL particles or HDL function may be more important than their cholesterol content. Indeed, there has been an explosion of studies assessing the ability of serum HDL to promote cholesterol efflux because, in several cases, this proved to be better than HDL-C at predicting CHD.12

HDL is a heterogeneous group of particles that differ according to density, size, charge, protein, and lipid composition. This heterogeneity is accompanied by a staggering degree of functional diversity, with documented HDL roles in lipid transport, endothelial protection, anti-inflammation, antioxidation, antithrombosis, and the acute phase response.13 HDL also has less-appreciated roles in complement pathway activation, anti-infection, and protease inhibition.13 This functional diversity is driven by some 95 proteins that have been found to be associated with HDL particles, as tracked by the HDL Proteome Watch website.14

It is becoming clear that these proteins differentially segregate on HDL subspecies depending on their density and size,15,16 producing HDL subparticles with distinct proteomic makeups. Furthermore, there is evolving evidence that these distinct particles specialize in unique functions. For example, the trypanosome lytic factor of HDL contains two specific proteins that allow the particle to kill invading parasites.17 The presence or absence of apolipoprotein AII appears to dictate whether a given HDL particle participates in lipid transport functions or other activities, such as complement activation.18 Given the arguments above, it stands to reason that HDL-C does not adequately capture the full measure or uniqueness of an individual's HDL subspecies profile, a profile that may impact disease susceptibility. The importance of this concept is evidenced by the rapid rise of advanced lipoprotein testing techniques,19 in which analytical approaches such as differential ion mobility, 2-dimensional (2D) gel electrophoresis, and nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) spectroscopy have been used to track lipoprotein subspecies in clinical samples. Table 1 summarizes the different types of lipoprotein analysis methods and their advantages/disadvantages. Here, we explore the current state of the art for understanding HDL subspeciation in the context of type 2 diabetes, a major risk factor for the development of CHD.

Table 1.

An overview of methods used to isolate high-density lipoprotein subspecies. HDL: high-density lipoprotein

| METHOD | SUBSPECIES | ADVANTAGES | DISADVANTAGES |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ultracentrifugation | HDL 1,2,3 HDL 2b,2a, 3A,3b, and 3c |

Size and density separation | Overlap with density similar lipoproteins like Lp (a) Imparts ionic strength and sheer stress and uses high salt concentrations |

| Two-dimensional gel electrophoresis | Charge: pre-beta, alpha, and pre-alpha Size: pre-beta-1 HDL, pre-beta-2, alpha 4- HDL, alpha 3- HDL, alpha-2 HDL, alpha-1 HDL, pre-alpha |

Charge and size separation | Particles are not recoverable from the gel for functional analyses |

| Nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy | Small, medium, large. Newer algorithms can detect seven subclasses of HDL | Size separation High throughput Can quantify a particle number and particle size |

Assumes that a constant number of methyl groups on each HDL subclass is constant, although newer algorithms account for variation Potential interference from plasma proteins Collinearity among subclasses needs to be accounted for in the analysis |

| Ion mobility | Very large, large, medium, small, and very small subspecies | Size separation Can quantify a particle number |

HDL is isolated by ultracentrifugation first |

| Gel filtration | Six HDL subclasses and four lipid poor subspecies | Size separation Ability to isolate low abundant HDL particles Recoverability of HDL subclasses to study function |

Time intensive Coelution with other plasma proteins such as albumin and globulins |

HIGH-DENSITY LIPOPROTEIN SUBSPECIES IN TYPE 2 DIABETES

Type 2 diabetes (T2D) is a chronic metabolic disease characterized by insulin resistance and impaired pancreatic insulin secretion that eventually leads to high plasma glucose levels. It is associated with serious comorbidities including dyslipidemia, hypertension, kidney and eye disease, and blindness, and most patients die from complications of premature CHD or stroke. As serious as this is in adults, youth with T2D tend to exhibit even greater insulin resistance, more comorbidities, and poorer responses to medical treatment.

One of the most striking lipoprotein abnormalities in T2D is an increase in circulating triglycerides and a lowering of plasma HDL-C levels. Early studies using density ultracentrifugation to differentiate HDL density subspecies revealed that patients with T2D tend to exhibit lower levels of cholesterol-rich, larger HDL2 species but higher levels of cholesterol-poorer HDL3.20 Two-dimensional gel separation studies have shown that women with T2D exhibit lower levels of large α-1, α-2, and pre-α-1 particles. They also showed higher levels of smaller species such as lipid-poor α-3, which is consistent with the ultracentrifugation studies.21 Nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy can ascertain lipoprotein size profiles while simultaneously quantitating particle concentrations in a high-throughput manner. There have been several studies in patients with T2D using this method.22–24 These studies are remarkably consistent and generally show that adults with new or established T2D exhibit reduced levels of medium (9.0–11.5 nm) and large (11.5–18.9 nm) HDL particles but enrichment of small (7.8–9.0 nm) HDL compared to controls without diabetes. In addition, it appears that subtle particle size shifts in HDL may precede the T2D diagnosis. For example, Mora et al. found that levels of small HDL particles were positively associated with future T2D risk and large HDL particles was inversely associated.24

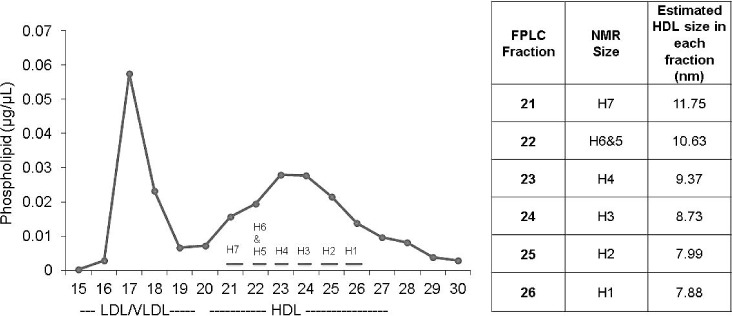

Recognizing the need for a lipoprotein analysis that allows the recovery and functional characterization of lipoprotein subspecies, our laboratory developed a gel filtration (size exclusion) chromatography technique to separate lipoproteins by size across 15 fractions.16 We applied this to a cohort of age- and sex-matched adolescents who were either lean, obese, or obese with T2D. Youth with T2D exhibited dramatically lower phospholipid content in large HDL subspecies compared to lean youth, likely reflecting reduced particle numbers. These species correlated negatively and significantly to pulse wave velocity, a measure of vascular stiffness, indicating that a lower amount of large HDL particles was associated with predictors of eventual CHD. With the ability to analyze these particles, we found that youth with T2D exhibited decreased levels of apoAI as well as apoE, apoCI, and paraoxonase 1 in large HDL and a reduced ability to participate in cholesterol efflux and protect LDL from oxidation, likely due to fewer large HDL present.25,26 The gel filtration method corresponds well to the most recent particle size algorithms for the NMR analysis (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

The relationship between size exclusion chromatography and nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) spectroscopy. Plasma was separated by size exclusion chromatography. Choline-containing phospholipid was quantified in each fraction using a kit from Wako. Eluted fractions were also quantified by NMR spectroscopy at LabCorp (formerly LipoScience) using an optimized version (LP4) of NMR LipoProfile. The average size particles from each of the gel filtration fraction quantified by NMR is shown in the table to the right and are consistent with those obtained by NMR. LDL: low-density lipoprotein; VLDL: very low-density lipoprotein; HDL: high-density lipoprotein; FPLC: fast protein liquid chromatography

EFFECTS OF MEDICAL TREATMENT ON HDL SUBSPECIES

In the context of T2D, several groups have investigated the effects of clinical interventions on HDL subspecies profile. Using ultracentrifugation, Hiukka et al. showed that treatment with fenofibrate, a PPARα activator, further lowered HDL2 and increased HDL3, thus exacerbating the apparently deleterious T2D profile, at least in terms of HDL.27 Similarly, 2D gel studies showed that fenofibrate treatment increased smaller α-3 and α-4 species in T2D. Statins had the opposite effect and tended to increase large α-1 HDL particles in T2D.28 Intensive diabetes control targeting a hemoglobin A1c of < 6% was similar to statins; there was an improvement in NMR profile resulting in fewer small HDL particles and higher concentrations of medium HDL particles.29 Our laboratory asked whether the surgical weight loss with vertical sleeve gastrectomy (VSG) could restore the HDL particle size profile that we observed in lean adolescents.30 We studied obese adolescents prior to and 1 year after VSG. At follow-up, mean body mass index decreased by 32%, insulin resistance improved by 75%, and we observed remarkable rescue of the large HDL subspecies that approached levels in lean controls. Interestingly, there were relatively minor differences in LDL and very low-density lipoprotein (VLDL) subspecies in these participants, suggesting that HDL is particularly sensitive to changes in adiposity and insulin sensitivity. Thus, statins and treatments that specifically target glucose control, obesity, and insulin resistance appear to exhibit favorable shifts in the HDL profile.

MECHANISMS OF HDL SUBSPECIES PROFILE SHIFTS IN T2D

Nascent HDL particles of various sizes are created on the surface of liver and peripheral cells via the interaction of apoAI with ATP binding cassette transporter A1 (ABCA1). These particles appear to mature independently in the circulation via interaction with HDL remodeling enzymes such as lecithin:cholesterol acyl transferase (LCAT) and cholesteryl ester transfer protein (CETP), among others.31 Additionally, some HDL is derived from the hydrolysis of triglyceride (TG)-rich VLDL and chylomicrons during postprandial lipemia. Goldberg et al. put forth a plausible model for HDL-C lowering in T2D.32 Patients with T2D tend to have more TG-rich VLDL due to greater free fatty acid availability in the liver. Thus, VLDL catabolism-derived HDL particles become enriched in TG at the expense of cholesterol ester (CE) via the action of CETP. This has a net effect of driving plasma HDL-C lower. Additionally, these TG-rich HDL species are excellent substrates for lipolysis via hepatic lipase, driving a shift from large to smaller, denser HDL. This shift in HDL size can also be envisioned from the perspective of HDL maturation. LCAT levels negatively correlate with glycemic control (hemoglobin A1c).33 Nakhajavani et al. suggested that HDL glycation reduces LCAT catalyzed CE formation, a proposal supported by in vitro evidence of lower LCAT reactivity toward glycated HDL.34,35 This hinders the formation of large HDL in favor of smaller CE-poor HDL.

We have investigated the risk factors associated with fewer large HDL subspecies in adolescents with T2D. We studied five adolescent groups of similar age, race, and sex who were lean/insulin sensitive, lean/insulin resistant, obese/insulin sensitive, obese/insulin resistant, or obese with T2D. Using a regression model analysis, we found that obesity, insulin resistance, and hyperglycemia explained about half of the phospholipid content variance in large HDL subspecies, with the majority driven by obesity. This, along with data showing reversibility of the HDL size species profile with weight-loss surgery, suggests that the shifts in the HDL subspecies profile are influenced by a complex interplay of adiposity and insulin sensitivity.

PHYSIOLOGICAL CONSEQUENCES OF HDL SUBSPECIES SHIFTS IN T2D

There is a large body of data showing deleterious effects of T2D on HDL function. T2D influences the HDL proteome.26 HDL from patients with T2D is impaired at reducing superoxide production induced by TNF-α in endothelial cells.36 HDL in T2D also is less able to inhibit oxidized LDL-induced endothelial relaxation37 and is less effective at stimulating endothelial nitric oxide synthase activity in the endothelium.38 Additionally, ample in vitro studies have shown that nonenzymatic glycation exhibits deleterious effects in most HDL-attributed antiatherosclerotic functions, though the relevance of the glycation levels in these studies versus those occurring in T2D circulation is debatable. Beyond effects of T2D on HDL as a whole, significantly less information is available about the impact on the functionality of individual HDL subspecies. Most of the evidence suggests an association between large HDL species and atheroprotection in population studies.39 Many have extolled the virtues of small HDL subspecies; however, most of these claims have been extrapolated from presumably atheroprotective functions identified in vitro.

The impact of differing size species in reverse cholesterol transport is complex. In vitro large phospholipid-rich HDL are known to be more efficient acceptors of cellular cholesterol transferred by aqueous diffusion mediated mechanisms, whereas smaller, lipid-poor forms work best via ABCA1.40 Tan and colleagues showed that cholesterol efflux from macrophages correlated well with levels of medium-sized HDL, and not small HDL, in patients with well-controlled T2D.41 Larger species bind more avidly to SR-BI than smaller particles at the last step of reverse cholesterol transport,42 perhaps facilitating more CE delivery to the liver via selective uptake. With respect to LDL retention in the vessel wall, Umareus et al. speculated that larger HDL2 subspecies, perhaps due to increased apoE content, can compete with LDL to bind proteoglycans and thereby prevent its entrapment in the intima.43 The reduction of these species in T2D could therefore be envisioned to facilitate LDL aggregation in the vessel wall. Given the known roles of HDL in these and many other processes, it is likely that T2D attenuates HDL atheroprotection through a combination of different mechanisms.

OTHER LIPOPROTEINS IN TYPE 2 DIABETES

The data reviewed above has focused on HDL in the setting of T2D. However, it should be noted that other lipoproteins are also affected in T2D. For example, VLDL consistently shifts towards larger particles while LDL particles tend to get smaller and more dense. There is little doubt that these changes also influence CHD risk in patients with T2D. However, in work published by us and others in which the same patients are studied before and after weight-loss surgery (bypass or gastric banding), we note dramatic changes in HDL subspecies but no significant differences in VLDL/LDL subspecies.30,44 This suggests that the obesity and insulin resistance underlying T2D, and their reversal, may have a greater influence on HDL than VLDL/LDL, which is why it has been the focus of this article.

LOOKING FORWARD

In summary, T2D clearly results in a reduction of HDL-C that is underpinned by a marked shift from large CE-rich HDL particles to smaller, denser TG-rich HDL subspecies. This change in HDL distribution is accompanied by changes in proteomic composition that undoubtedly affect the functionality of the particles, likely shifting the balance from functional to dysfunctional HDL. These observations raise several important questions. Chief among these is whether the HDL subspecies profile is actively protective against deleterious effects of T2D (i.e., causal) or if the subspecies profile changes passively as a consequence of the disease progression. A recent Mendelian randomization study found that HDL-C levels were not associated with an increased risk of T2D.45 However, this analysis focused on the relatively uninformative marker of HDL-C and did not address HDL subspecies. On the other hand, recent studies have clearly shown that HDL has antidiabetic functions including inhibiting pancreatic β-cell death and improving insulin-mediated uptake of glucose in skeletal muscle.46 Furthermore, a recent meta-analysis of CETP clinical trials hints that these drugs reduce the incidence of diabetes, presumably via HDL effects.47

To fully address this question, HDL subspecies will need to be manipulated with minimal impact on other metabolic parameters, a daunting task. Furthermore, we have yet to identify an animal model that fully recapitulates the HDL species changes observed in response to T2D or obesity seen in humans. As a result, it is not surprising that there are so few molecular and functional characterizations of HDL subspecies, before or after T2D onset. We believe that if the HDL particles can be isolated and their compositions and functions fully elucidated, this may point to subspecies particularly important in CHD. Then it may become possible to design therapies that will either manipulate the levels of these specific particles or target the protective functions that they mediate, thereby reducing CHD in patients with T2D.

KEY POINTS

High-density lipoproteins (HDL) are a heterogeneous group of particles of different size and composition.

Advanced lipid testing allows for size and charge separation of HDL particles with the ability to quantify particle number in some cases.

Type 2 diabetes affects the distribution of HDL particles, with a shift from large HDL particles rich in cholesteryl esters to smaller, denser triglyceride-rich HDL subspecies.

HDL particles need to be linked to function in order to fully elucidate HDL's role in cardiovascular disease.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute, R01HL67093, P01HL128203, and R01HL104136 to W.S.D. and K23HL118132 to A.S.S.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest Disclosure: The authors have completed and submitted the Methodist DeBakey Cardiovascular Journal Conflict of Interest Statement and none were reported.

REFERENCES

- 1.Gordon T, Castelli WP, Hjortland MC, Kannel WB, Dawber TR. High density lipoprotein as a protective factor against coronary heart disease. The Framingham Study. Am J Med. 1977 May;62(5):707–14. doi: 10.1016/0002-9343(77)90874-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sharrett AR, Ballantyne CM, Coady SA et alCoronary heart disease prediction from lipoprotein cholesterol levels, triglycerides, lipoprotein(a), apolipoproteins A-I and B, and HDL density subfractions: The Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities (ARIC) Study. Circulation. 2001 Sep 4;104(10):1108–13. doi: 10.1161/hc3501.095214. .; Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities Study Group. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gordon DJ, Probstfield JL, Garrison RJ et al. High-density lipoprotein cholesterol and cardiovascular disease. Four prospective American studies. Circulation. 1989 Jan;79(1):8–15. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.79.1.8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.HPS2-THRIVE Collaborative Group HPS2-THRIVE randomized placebo-controlled trial in 25 673 high-risk patients of ER niacin/laropiprant: trial design, pre-specified muscle and liver outcomes, and reasons for stopping study treatment. Eur Heart J. 2013 May;34(17):1279–91. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/eht055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Barter PJ, Caulfield M, Eriksson M et alEffects of torcetrapib in patients at high risk for coronary events. N Engl J Med. 2007 Nov 22;357(21):2109–22. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0706628. .; ILLUMINATE Investigators. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.AIM-HIGH Investigators. Boden WE, Probstfield JL et al. Niacin in patients with low HDL cholesterol levels receiving intensive statin therapy. N Engl J Med. 2011 Dec 15;365(24):2255–67. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1107579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Schwartz GG, Olsson AG, Abt M et alEffects of dalcetrapib in patients with a recent acute coronary syndrome. N Engl J Med. 2012 Nov 29;367(22):2089–99. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1206797. .; dal-OUTCOMES Investigators. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ferri N, Corsini A, Sirtori CR, Ruscica M. Present therapeutic role of cholesteryl ester transfer protein inhibitors. Pharmacol Res. 2018 Feb;128:29–41. doi: 10.1016/j.phrs.2017.12.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.HPS2-THRIVE Collaborative Group. Landray MJ, Haynes R et al. Effects of extended-release niacin with laropiprant in high-risk patients. N Engl J Med. 2014 Jul 17;371(3):203–12. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1300955. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Voight BF, Peloso GM, Orho-Melander M et al. Plasma HDL cholesterol and risk of myocardial infarction: a mendelian randomisation study. Lancet. 2012 Aug 11;380(9841):572–80. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60312-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Castro GR, Fielding CJ. Early incorporation of cell-derived cholesterol into pre-beta-migrating high-density lipoprotein. Biochemistry. 1988 Jan 12;27(1):25–9. doi: 10.1021/bi00401a005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rohatgi A. High-Density Lipoprotein Function Measurement in Human Studies: Focus on Cholesterol Efflux Capacity. Prog Cardiovasc Dis. 2015 Jul-Aug;58(1):32–40. doi: 10.1016/j.pcad.2015.05.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rye KA. High density lipoprotein structure, function, and metabolism: a new Thematic Series. J Lipid Res. 2013 Aug;54(8):2031–3. doi: 10.1194/jlr.E041350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.The Davidson/Shah Lab {Internet] Cincinnatti, OH: University of Cincinnatti; c2015. HDL Proteome Watch; 2015 Aug 14 {cited 2018 Oct10]. Available from: http://homepages.uc.edu/~davidswm/HDLproteome.html. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Davidson WS, Silva RA, Chantepie S, Lagor WR, Chapman MJ, Kontush A. Proteomic analysis of defined HDL subpopulations reveals particle-specific protein clusters: relevance to antioxidative function. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2009 Jun;29(6):870–6. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.109.186031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gordon SM, Deng J, Lu LJ, Davidson WS. Proteomic characterization of human plasma high density lipoprotein fractionated by gel filtration chromatography. J Proteome Res. 2010 Oct 1;9(10):5239–49. doi: 10.1021/pr100520x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Raper J, Fung R, Ghiso J, Nussenzweig V, Tomlinson S. Characterization of a novel trypanosome lytic factor from human serum. Infect Immun. 1999 Apr;67(4):1910–6. doi: 10.1128/iai.67.4.1910-1916.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Melchior JT, Street SE, Andraski AB et al. Apolipoprotein A-II alters the proteome of human lipoproteins and enhances cholesterol efflux from ABCA1. J Lipid Res. 2017 Jul;58(7):1374–85. doi: 10.1194/jlr.M075382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chandra A, Rohatgi A. The role of advanced lipid testing in the prediction of cardiovascular disease. Curr Atheroscler Rep. 2014 Mar;16(3):394. doi: 10.1007/s11883-013-0394-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bakogianni MC, Kalofoutis CA, Skenderi KI, Kalofoutis AT. Clinical evaluation of plasma high-density lipoprotein subfractions (HDL2, HDL3) in non-insulin-dependent diabetics with coronary artery disease. J Diabetes Complications. 2001 Sep-Oct;15(5):265–9. doi: 10.1016/s1056-8727(01)00159-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Russo GT, Giandalia A, Romeo EL et al. Markers of Systemic Inflammation and Apo-AI Containing HDL Subpopulations in Women with and without Diabetes. Int J Endocrinol. 2014;2014 doi: 10.1155/2014/607924. 607924. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Amor AJ, Catalan M, Pérez A et al. Nuclear magnetic resonance lipoprotein abnormalities in newly-diagnosed type 2 diabetes and their association with preclinical carotid atherosclerosis. Atherosclerosis. 2016 Apr;247:161–9. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2016.02.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Garvey WT, Kwon S, Zheng D et al. Effects of insulin resistance and type 2 diabetes on lipoprotein subclass particle size and concentration determined by nuclear magnetic resonance. Diabetes. 2003 Feb;52(2):453–62. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.52.2.453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mora S, Otvos JD, Rosenson RS, Pradhan A, Buring JE, Ridker PM. Lipoprotein particle size and concentration by nuclear magnetic resonance and incident type 2 diabetes in women. Diabetes. 2010 May;59(5):1153–60. doi: 10.2337/db09-1114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Davidson WS, Heink A, Sexmith H et al. Obesity is associated with an altered HDL subspecies profile among adolescents with metabolic disease. J Lipid Res. 2017 Sep;58(9):1916–23. doi: 10.1194/jlr.M078667. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gordon SM, Davidson WS, Urbina EM et al. The effects of type 2 diabetes on lipoprotein composition and arterial stiffness in male youth. Diabetes. 2016 Jul;65(7):2100. doi: 10.2337/db16-er07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hiukka A, Leinonen E, Jauhiainen M et al. Long-term effects of fenofibrate on VLDL and HDL subspecies in participants with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Diabetologia. 2007 Oct;50(10):2067–75. doi: 10.1007/s00125-007-0751-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Soedamah-Muthu SS, Colhoun HM, Thomason MJ et alThe effect of atorvastatin on serum lipids, lipoproteins and NMR spectroscopy defined lipoprotein subclasses in type 2 diabetic patients with ischaemic heart disease. Atherosclerosis. 2003 Apr;167(2):243–55. doi: 10.1016/s0021-9150(02)00428-8. .; CARDS Investigators. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Azar M, Lyons TJ, Alaupovic P et al. Apolipoprotein-defined and NMR lipoprotein subclasses in the veterans affairs diabetes trial. J Diabetes Complications. 2013 Nov-Dec;27(6):627–32. doi: 10.1016/j.jdiacomp.2013.05.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Davidson WS, Inge TH, Sexmith H et al. Weight loss surgery in adolescents corrects high-density lipoprotein subspecies and their function. Int J Obes (Lond) 2017 Jan;41(1):83–9. doi: 10.1038/ijo.2016.190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mendivil CO, Furtado J, Morton AM, Wang L, Sacks FM. Novel Pathways of Apolipoprotein A-I Metabolism in High-Density Lipoprotein of Different Sizes in Humans. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2016 Jan;36(1):156–65. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.115.306138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Goldberg IJ. Clinical review 124: Diabetic dyslipidemia: causes and consequences. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2001 Mar;86(3):965–71. doi: 10.1210/jcem.86.3.7304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Awadallah S, Madkour M, Hamidi RA et al. Plasma levels of Apolipoprotein A1 and Lecithin:Cholesterol Acyltransferase in type 2 diabetes mellitus: Correlations with haptoglobin phenotypes. Diabetes Metab Syndr. 2017 Dec;11(Suppl 2):S543–S546. doi: 10.1016/j.dsx.2017.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Nakhjavani M, Esteghamati A, Esfahanian F, Ghanei A, Rashidi A, Hashemi S. HbA1c negatively correlates with LCAT activity in type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2008 Jul;81(1):38–41. doi: 10.1016/j.diabres.2008.01.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Fournier N, Myara I, Atger V, Moatti N. Reactivity of lecithin-cholesterol acyl transferase (LCAT) towards glycated high-density lipoproteins (HDL) Clin Chim Acta. 1995 Jan 31;234(1–2):47–61. doi: 10.1016/0009-8981(94)05975-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sorrentino SA, Besler C, Rohrer L et al. Endothelial-vasoprotective effects of high-density lipoprotein are impaired in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus but are improved after extended-release niacin therapy. Circulation. 2010 Jan 5;121(1):110–22. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.108.836346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Perségol L, Vergès B, Foissac M, Gambert P, Duvillard L. Inability of HDL from type 2 diabetic patients to counteract the inhibitory effect of oxidised LDL on endothelium-dependent vasorelaxation. Diabetologia. 2006 Jun;49(6):1380–6. doi: 10.1007/s00125-006-0244-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Vaisar T, Couzens E, Hwang A et al. Type 2 diabetes is associated with loss of HDL endothelium protective functions. PLoS One. 2018 Mar 15;13(3) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0192616. e0192616. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Asztalos BF, Tani M, Schaefer EJ. Metabolic and functional relevance of HDL subspecies. Curr Opin Lipidol. 2011 Jun;22(3):176–85. doi: 10.1097/MOL.0b013e3283468061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Asztalos BF, de la Llera-Moya M, Dallal GE, Horvath KV, Schaefer EJ, Rothblat GH. Differential effects of HDL subpopulations on cellular ABCA1- and SR-BI-mediated cholesterol efflux. J Lipid Res. 2005 Oct;46(10):2246–53. doi: 10.1194/jlr.M500187-JLR200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Tan HC, Tai ES, Sviridov D et al. Relationships between cholesterol efflux and high-density lipoprotein particles in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. J Clin Lipidol. 2011 Nov-Dec;5(6):467–73. doi: 10.1016/j.jacl.2011.06.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.de Beer MC, Durbin DM, Cai L, Jonas A, de Beer FC, van der Westhuyzen DR. Apolipoprotein A-I conformation markedly influences HDL interaction with scavenger receptor BI. J Lipid Res. 2001 Feb;42(2):309–13. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Umaerus M, Rosengren B, Fagerberg B, Hurt-Camejo E, Camejo G. HDL2 interferes with LDL association with arterial proteoglycans: a possible athero-protective effect. Atherosclerosis. 2012 Nov;225(1):115–20. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2012.08.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Heffron SP, Singh A, Zagzag J et al. Laparoscopic gastric banding resolves the metabolic syndrome and improves lipid profile over five years in obese patients with body mass index 30–40 kg/m2. Atherosclerosis. 2014 Nov;237(1):183–90. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2014.08.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Haase CL, Tybjarg-Hansen A, Nordestgaard BG, Frikke-Schmidt R. HDL Cholesterol and Risk of Type 2 Diabetes: A Mendelian Randomization Study. Diabetes. 2015 Sep;64(9):3328–33. doi: 10.2337/db14-1603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.von Eckardstein A, Widmann C. High-density lipoprotein, beta cells, and diabetes. Cardiovasc Res. 2014 Aug 1;103(3):384–94. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvu143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Masson W, Lobo M, Siniawski D et al. Therapy with cholesteryl ester transfer protein (CETP) inhibitors and diabetes risk. Diabetes Metab. 2018 Feb 20; doi: 10.1016/j.diabet.2018.02.005. pii: S1262-3636(18)30045-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]