Abstract

Women have been reported to suffer from impaired outcome after acute myocardial infarction (AMI). The aim of our study was to determine the impact of sex and age on utilization of inpatient healthcare and outcome in patients with AMI (STEMI and NSTEMI) in a real‐life setting. We performed a routine‐data‐based analysis of 203 106 nationwide inpatients hospitalized with STEMI and NSTEMI, focusing on sex differences regarding risk constellation, treatments, and in‐hospital outcome. A logistic regression model was designed to evaluate the use of coronary angiography and interventions and their sex‐related impact on mortality (within 30 days). Compared with males, female STEMI patients (25 146, vs 52 965 males) were older and had a higher incidence of diabetes mellitus (27.4% vs 20.6%), heart failure (32.8% vs 26.2%), and chronic kidney disease (19.1% vs 13.5%, respectively; all P < 0.05), and had higher observed in‐hospital mortality (STEMI, 16.9% vs 9.9%; NSTEMI, 11.7% vs 8.7%). Females were less likely to receive coronary angiography in STEMI in the age groups <60 and ≥ 80 years (odds ratio: 0.8, 95% confidence interval: 0.76–0.83, P < 0.05), despite similar mortality risk reduction. Estimated overall in‐hospital mortality showed no differences with respect to sex in STEMI for age groups 40 to 79 years. However, females age ≥ 80 years had slightly higher in‐hospital mortality after adjustment. The increased observed in‐hospital mortality in females was attributed to the impact of more unfavorable risk and age distribution. Coronary angiography was associated with lower in‐hospital mortality; particularly, older females were less frequently treated.

Keywords: Acute Coronary Care, Acute Coronary Syndrome, Epidemiology, Gender, Women

1. INTRODUCTION

Acute myocardial infarction (AMI) is one of the most prevalent diseases worldwide, remaining among the most common causes of death in males and females.1 In the recent past, female sex has been emerged to be associated with an unfavorable outcome in AMI.2, 3 Until today, the undeniable impact on mortality of an increased risk profile and older age in female patients has been controversially debated, and published data showed inconsistent results. Whereas some data showed no sex‐related differences in AMI mortality,4, 5, 6 other analyses revealed worse outcome in females compared with males persisting after adjustment for age or risk profile.3, 7, 8, 9 In addition, delayed diagnostics and potential undertreatment of females have been argued to further deteriorate the prognosis of female AMI patients.10, 11, 12 However, it has been suggested that differences in medical history, clinical severity, and early management accounted for only about one‐third of the difference in the mortality risk between male and female patients.8 But irrespective of the underlying reasons, these data pointed out the need for improved AMI prevention and optimized therapeutic strategies in females.13 The effectiveness of the measures taken to overcome these sex‐related differences is predominantly derived from highly selected populations of randomized clinical trials14 and therefore may present an idealized scenario.

The aim of our nationwide analysis is to present the status of inpatient healthcare of male and female patients with AMI. We distinguish between ST‐segment elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI) and non–ST‐segment elevation myocardial infarction (NSTEMI) by reason of differing epidemiological, pathological, and prognostic characteristics13, 15 and differing guideline recommendations in matters of the type of AMI. We sought to examine the impact of sex on risk profile, STEMI and NSTEMI frequency, treatments, and in‐hospital outcome in a real‐world setting.

2. METHODS

Data on diagnoses, comorbidities, diagnostic and therapeutic procedures, and in‐hospital mortality from all hospitalized patients with AMI as the primary diagnosis in 2009 were obligatorily transferred to the German Institute for the Hospital Remuneration System (InEK). Either STEMI or NSTEMI as the primary diagnosis (International Classification of Diseases [ICD] I21–I22) and coexisting diseases as secondary diagnoses were encoded according to the German Modification of the International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems, Tenth Revision (ICD‐10‐GM). All diagnostic, endovascular, and surgical procedures were coded in detail according to the German Procedure Classification (OPS). Diagnoses and procedures assigned to the respective ICD/OPS codes are listed in Supporting Information, Table 1, in the online version of this article. Data retrieval was subject to the regulations of the diagnosis‐ and procedure‐related remuneration system (German Diagnosis Related Groups). These anonymized data were further processed with respect to sex and age using the SAS statistical analysis program, version 9.2 (SAS Institute, Inc., Cary, NC) and made available for further analysis by the Research Data Centre of the Federal Statistical Office and the Statistical Offices of the Länder (Statistisches Bundesamt [DESTATIS]; https://www.destatis.de) as an aggregated, anonymized, case‐based dataset. The provided data comprise a statement of all inpatient cases in Germany, except for psychiatric or psychosomatic units or medical care provided by office‐based specialists. For the purpose of data‐protection measures, subgroups consisting of <6 patients were excluded from further analysis.

Approval by the ethics committee was not required in accordance with German law, because no individual patient data were obtained and analyzed. Further details on data acquisition have been described previously.15, 16

2.1. Statistical analysis

To assess the effect of sex on STEMI or NSTEMI in‐hospital mortality, specific logistic regression analyses were performed for each combination of age and the comorbidity of interest (hypertension [HTN], type 2 diabetes mellitus [T2DM], chronic heart failure [CHF], chronic kidney disease [CKD], and peripheral arterial disease) as covariates. To allow for potential dependencies of the sex‐specific mortality on age and/or the specific comorbidity, corresponding interaction terms were added. Quadratic age dependencies were used because model fit was improved with this choice, and the corresponding likelihood‐ratio test was significant. For reasons of data protection, only datasets with 1 comorbidity were available, and combining different comorbidities in 1 model was not allowed. Datasets were separated by comorbidities, and merging of aggregated data was not possible. Therefore, we estimated sex and age, but no further comorbidity‐adjusted effects. As reference, a model without any comorbidity was calculated.

Furthermore, the frequency of application of coronary angiography (CA) was analyzed by modeling sex and age, as well as their interaction, as predictors, as before a nonlinear age effect was assumed.

For all models, a backward elimination based on likelihood‐ratio tests was performed to select the subset of significant predictors. With the resulting models, odds ratios (ORs) for sex with corresponding 95% confidence intervals (CIs) as well as predicted probabilities for mortality or application of CA with corresponding 95% CI were calculated. To visualize potential sex differences, these predicted probabilities were depicted across the observed proportions.

Nominal P values were reported without correction for multiplicity. Two‐sided P values <0.05 were considered significant. All analyses were computed using Stata Statistical Software, release 14.0 (StataCorp LP, College Station, TX).

3. RESULTS

A total of 203 106 patients (females: 73 651 [36.3%]) were hospitalized nationwide with AMI in 2009. Of the 203 106 total patients, 78 111 (38.5%) presented with STEMI and 124 995 (61.5%) with NSTEMI. Male sex predominated, with 67.8% in STEMI and 61.2% in NSTEMI (Table 1).

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of patients

| Male, n (% Within Subgroup) | Female, n (% Within Subgroup) | Total, N (% Within Subgroup) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total | 129 455 | 73 651 | 203 106 |

| STEMI | 52 965 (40.9) | 25 146 (34.1) | 78 111 (38.5) |

| Age | |||

| <40 y | 1299 (2.4) | 292 (1.2) | 1591 (2.0) |

| 40–49 y | 7359 (13.9) | 1499 (6.0) | 8858 (11.3) |

| 50–59 y | 12 772 (24.1) | 2839 (11.3) | 15 611 (20.0) |

| 60–69 y | 12 838 (24.2) | 4141 (16.5) | 16 979 (21.7) |

| 70–79 y | 12 813 (24.2) | 7658 (30.5) | 20 471 (26.2) |

| 80–89 y | 5464 (10.3) | 7500 (29.8) | 12 964 (16.6) |

| ≥95 y | 409 (0.7) | 1204 (4.8) | 1613 (2.1) |

| ≥60 y | 31 524 (59.5) | 20 503 (81.5) | 52 027 (66.6) |

| ≥75 y | 11 204 (21.2) | 12 585 (50.0) | 23 789 (30.5) |

| HTN | 31 928 (60.3) | 16 216 (64.5) | 48 144 (61.6) |

| T2DM | 10 908 (20.6) | 6899 (27.4) | 17 807 (22.8) |

| CHF | 13 855 (26.2) | 8238 (32.8) | 22 093 (28.3) |

| CKD | 7171 (13.5) | 4797 (19.1) | 11 968 (15.3) |

| PAD | 1896 (3.6) | 819 (3.3) | 2715 (3.5) |

| NSTEMI | 76 490 (59.1) | 48 505 (65.9) | 124 995 (61.5) |

| Age | |||

| <40 y | 871 (1.1) | 240 (0.5) | 1111 (0.8) |

| 40–49 y | 5148 (6.7) | 1303 (2.7) | 6451 (5.2) |

| 50–59 y | 11 500 (15.0) | 3110 (6.4) | 14 610 (11.7) |

| 60–69 y | 17 541 (22.9) | 6285 (13.0) | 23 826 (19.1) |

| 70–79 y | 24 997 (32.7) | 15 238 (31.4) | 40 235 (32.2) |

| 80–89 y | 14 990 (19.6) | 19 030 (39.2) | 34 020 (27.2) |

| ≥95 y | 1438 (1.9) | 3289 (6.8) | 4727 (3.8) |

| ≥60 y | 58 966 (77.1) | 43 842 (90.4) | 102 808 (82.2) |

| ≥75 y | 28 138 (36.8) | 30 442 (62.8) | 58 580 (46.9) |

| HTN | 52 012 (68.0) | 34 101 (70.3) | 86 113 (68.9) |

| T2DM | 22 563 (29.5) | 16 582 (34.2) | 39 145 (31.3) |

| CHF | 23 545 (30.8) | 17 149 (35.4) | 40 694 (32.6) |

| CKD | 18 677 (24.4) | 13 440 (27.7) | 32 117 (25.7) |

| PAD | 5244 (6.9) | 2334 (4.8) | 7578 (6.1) |

Abbreviations: CHF, chronic heart failure; CKD, chronic kidney disease; HTN, hypertension; NSTEMI, non–ST‐segment elevation myocardial infarction; PAD, peripheral arterial disease; STEMI, ST‐segment elevation myocardial infarction; T2DM, type 2 diabetes mellitus.

Unadjusted 2009 data. All P < 0.05.

3.1. Baseline characteristics

There was a strong correlation between AMI frequency and age, with male cases peaking at a younger age compared with females (see Supporting Information, Figure 1, in the online version of this article). In the STEMI group, 21.2% of male patients were age ≥ 75 years, vs 50.0% in females (Table 1); in the NSTEMI group, 36.8% of male patients were age ≥ 75 years, compared with 62.8% of female patients.

Further, males and females differed significantly with regard to comorbidities (Table 1). Females had a higher incidence of HTN (64.5% female vs 60.3% male), T2DM (27.4% vs 20.6%), CHF (32.8% vs 26.2%), and CKD (19.1% vs 13.5%) in the STEMI group, as well as in the NSTEMI group (HTN, 70.3% vs 68.0%; T2DM, 34.2% vs 29.5%; CHF, 35.4% vs 30.8%; and CKD, 27.7% vs 24.4% female vs male, respectively).

3.2. Therapeutic strategies

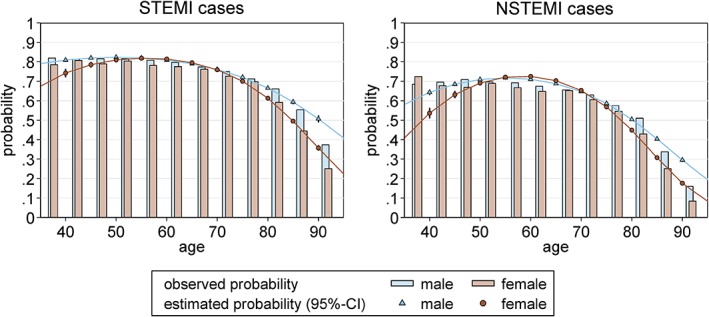

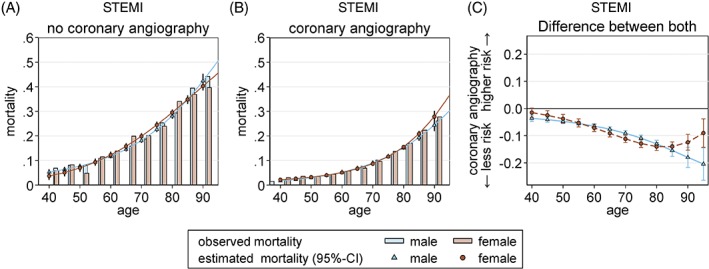

In the STEMI group, CA was performed in 76.5% of male and 65.9% of female patients (Table 2). Corresponding logistic regression modeling showed the probability of CA to be highly dependent on age for both sexes (Figure 1). There was no significant sex‐related difference in STEMI patients age < 70 years, and the chance of invasive diagnostics decreased, particularly in females, at higher ages (at age 80 years, OR: 0.8, 95% CI: 0.76–0.83, P < 0.001; at age 90 years, OR: 0.54, 95% CI: 0.49–0.59, P < 0.001). There was a statistically significantly lower chance of CA for females age < 50 years (age 40 years, female vs male OR: 0.68, 95% CI: 0.6–0.77, P < 0.01; age 50 years, female vs male OR: 0.91, 95% CI: 0.85–0.98, P = 0.012); however, in this age group, the regression model loses accuracy due to the low number of cases. Indeed, CA was associated with an increasing reduction of in‐hospital mortality at a similar level for males and females up to the age of 80 years (Figure 2), and beyond that there existed a further increasing benefit for male (but not female) STEMI patients (Figure 2). Percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) was performed in 91.9% of male and 89.0% of female STEMI patients who received CA (Table 2). The usage of bare‐metal stents (BMS; 64.4% in males vs 61.7% in females) and drug‐eluting stents (DES; 24.4% in males vs 22.3% in females) was lower in females than in males with STEMI.

Table 2.

Procedures and therapies

| Male, n (% Within Subgroup) | Female, n (% Within Subgroup) | Total, N (% Within Subgroup) | P Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| STEMI | 52 965 | 25 146 | 78 111 | <0.001 |

| CA | 40 526 (76.5) | 16 560 (65.9) | 57 086 (73.1) | <0.001 |

| PCI | 37 255 (70.3) | 14 743 (58.6) | 51 998 (66.6) | <0.001 |

| % of CAa | 91.9 | 89.0 | 91.1 | |

| BMS | 26 099 (49.3) | 10 218 (40.6) | 36 317 (46.5) | <0.001 |

| % of CAa | 64.4 | 61.7 | 63.6 | |

| DES | 9898 (18.7) | 3691 (14.7) | 13 589 (17.4) | <0.001 |

| % of CAa | 24.4 | 22.3 | 23.8 | |

| Lysis | 1117 (2.1) | 433 (1.7) | 1550 (2.0) | <0.001 |

| GpIIb/IIIa | 14 259 (26.9) | 5101 (20.3) | 19 360 (24.8) | <0.001 |

| DTI | 407 (0.8) | 155 (0.6) | 526 (0.7) | 0.022 |

| CABG | 2529 (4.8) | 798 (3.2) | 3327 (4.3) | <0.001 |

| NSTEMI | 76 490 | 48 505 | 124 995 | <0.001 |

| CA | 45 941 (60.1) | 22 856 (47.1) | 68 797 (55.0) | <0.001 |

| PCI | 31 608 (41.3) | 14 092 (29.1) | 45 700 (36.6) | <0.001 |

| % of CAa | 68.8 | 61.7 | 66.4 | |

| BMS | 19 034 (24.9) | 8769 (18.1) | 27 803 (22.2) | <0.001 |

| % of CAa | 41.4 | 38.4 | 40.4 | |

| DES | 10 989 (14.4) | 4513 (9.3) | 15 502 (12.4) | <0.001 |

| % of CAa | 23.9 | 19.7 | 22.5 | |

| Lysis | 451 (0.6) | 208 (0.4) | 659 (0.5) | 0.06 |

| GpIIb/IIIa | 6973 (9.1) | 2610 (5.4) | 9583 (7.7) | <0.001 |

| DTI | 312 (0.4) | 141 (0.3) | 453 (0.4) | 0.001 |

| CABG | 5456 (7.1) | 1718 (3.5) | 7174 (5.7) | <0.001 |

Abbreviations: BMS, bare‐metal stent; CA, coronary angiography; CABG, coronary artery bypass grafting; DES, drug‐eluting stent; DTI, direct thrombin inhibitor; GpIIb/IIIa, glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibitor; NSTEMI, non–ST‐segment elevation myocardial infarction; PCI, percutaneous coronary intervention; STEMI, ST‐segment elevation myocardial infarction.

Unadjusted 2009 data.

% of CA indicates relative use of the procedure within the subgroup that received CA.

Figure 1.

Age‐dependent CA application in STEMI and NSTEMI. The observed (bars) and adjusted (lines) probability of CA is given for female (red) and male (blue) patients for STEMI and NSTEMI. Whereas at the age groups of 55 to 70 years no significant difference of the application of CA could be observed, the chance of receiving CA decreases, particularly in females, at the upper and lower bounds of the age distribution in both STEMI and NSTEMI. Estimated probabilities (with corresponding 95% CIs) by sex at 5‐year age intervals are depicted, calculated with a logistic regression model that included age (quadratic) and sex and its interaction (NSTEMI, P interaction < 0.001; STEMI, P interaction < 0.001). Abbreviations: CA, coronary angiography; CI, confidence interval; NSTEMI, non–ST‐segment elevation myocardial infarction; STEMI, ST‐segment elevation myocardial infarction

Figure 2.

In‐hospital mortality dependent on CA and sex, STEMI group. Observed (bars) and adjusted (lines) data show in‐hospital mortality of STEMI without CA (panel A) compared with sex‐stratified in‐hospital mortality with CA (panel B). In STEMI, there is a significantly favorable impact of CA on the in‐hospital mortality in both sexes, showing an increasing trend with age (panel C). Probabilities were calculated with a logistic regression model that included age, sex, and CA and its interaction for STEMI (P 4‐way interaction = 0.002). Abbreviations: CA, coronary angiography; STEMI, ST‐segment elevation myocardial infarction

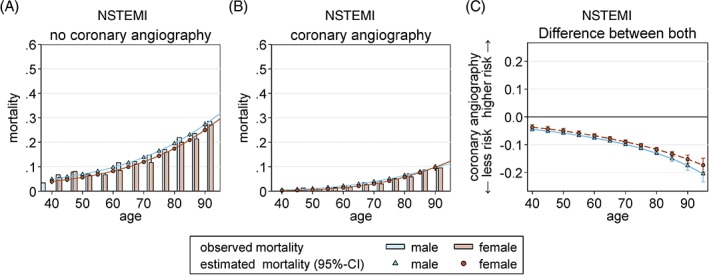

In the NSTEMI group, CA was performed in 60.1% of male and 47.1% of female patients (Table 2). The corresponding logistic regression showed lower rates of CA in females age > 75 years (Figure 1), despite CA being associated with a considerable reduction of in‐hospital mortality in males and (slightly less) in females, particularly at higher ages (Figure 3). In NSTEMI, the PCI rate was lower compared with STEMI; and again, it was lower in females (68.8% in males vs 61.7% in females; Table 2). Coronary stenting was more frequent in male NSTEMI patients (BMS, 41.4%; DES, 23.9%) compared with female NSTEMI patients (BMS, 38.4%; DES, 19.7%). Further, females less often underwent coronary artery bypass grafting (CABG) surgery compared with males (STEMI group: 4.8% male vs 3.2% female; NSTEMI group, 7.1% male vs 3.5% female). Moreover, regarding pharmacological treatment, females less often received thrombolysis, glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibitors, and the direct thrombin inhibitor bivalirudin in both STEMI and NSTEMI groups (Table 2).

Figure 3.

In‐hospital mortality dependent on CA and sex, NSTEMI group. Observed (bars) and adjusted (lines) data show in‐hospital mortality of NSTEMI without CA (panel A) compared with sex‐stratified in‐hospital mortality with CA (panel B). In NSTEMI, the benefit from CA is slightly more pronounced in male (blue) compared with female patients (red), showing an increasing trend with age in both sexes (panel C). Probabilities were calculated with a logistic regression model that included age, sex, and CA and its interaction for NSTEMI (P interaction = 0.045; P CA × age×age = 0.003). Abbreviations: CA, coronary angiography; NSTEMI, non–ST‐segment elevation myocardial infarction

3.3. In‐hospital mortality

In the STEMI group, the observed in‐hospital mortality was 9.9% in males compared with 16.9% in females (P < 0.001; see Supporting Information, Table 2, in the online version of this article). However, the logistic regression model applied to STEMI data revealed a strong correlation with age, with no persistent sex‐related difference concerning in‐hospital mortality after adjustment at the age groups of 40 to 79 years (Table 3; see Supporting Information, Figure 2, in the online version of this article). In fact, estimated in‐hospital mortality was slightly impaired in females at higher age groups (OR: 1.09, 95% CI: 1.01–1.19, P < 0.05).

Table 3.

Estimated in‐hospital mortality

| Age, y | Estimated Mortality in % (95% CI) | OR (95% CI) | P Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Female | Male | |||

| STEMI | ||||

| 40 | 2.5 (2.0–2.9) | 2.5 (2.2–2.8) | 0.99 (0.83–1.16) | 0.868 |

| 50 | 3.9 (3.5–4.4) | 3.9 (3.7–4.1) | 1.01 (0.89–1.14) | 0.916 |

| 60 | 6.6 (6.2–7.0) | 6.4 (6.2–6.7) | 1.03 (0.95–1.12) | 0.521 |

| 70 | 11.6 (11.1–12.1) | 11.1 (10.8–11.4) | 1.05 (0.99–1.11) | 0.078 |

| 80 | 20.7 (20.1–21.3) | 19.6 (19.0–20.2) | 1.07 (1.02–1.13) | 0.011 |

| 90 | 35.7 (34.5–37.0) | 33.7 (32.0–35.4) | 1.09 (1.01–1.19) | 0.034 |

| NSTEMI | ||||

| 40 | 1.4 (1.1–1.7) | 2.0 (1.7–2.3) | 0.71 (0.60–0.85) | <0.001 |

| 50 | 2.2 (1.9–2.5) | 2.9 (2.6–3.1) | 0.76 (0.66–0.86) | <0.001 |

| 60 | 3.6 (3.3–3.9) | 4.4 (4.2–4.6) | 0.81 (0.74–0.89) | <0.001 |

| 70 | 6.4 (6.1–6.7) | 7.3 (7.1–7.5) | 0.86 (0.82–0.91) | <0.001 |

| 80 | 11.9 (11.6–12.2) | 12.8 (12.4–13.1) | 0.92 (0.89–0.96) | <0.001 |

| 90 | 22.5 (21.8–23.2) | 22.8 (21.8–23.7) | 0.98 (0.92–1.05) | 0.621 |

Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; NSTEMI, non–ST‐segment elevation myocardial infarction; OR, odds ratio; STEMI, ST‐segment elevation myocardial infarction.

Based on 2009 data.

In the NSTEMI group, the adjusted in‐hospital mortality was even lower in females compared with males (age‐dependent OR ranging between 0.71 [95% CI: 0.6–0.85] and 0.92 [95% CI: 0.89–0.96], P < 0.001; Table 3 and Supporting Information, Figure 2, in the online version of this article) before aligning to that of males at the age of 90 years. A marked age‐dependent effect of the increased crude in‐hospital mortality could be shown in female NSTEMI patients (see Supporting Information, Figure 2, in the online version of this article).

The outcome of AMI was altered by the patients' comorbidity, as indicated by the encoded secondary diagnoses (see Supporting Information, Figure 3, in the online version of this article). Logistic regression analyses accounting for age and sex showed T2DM to have a beneficial effect in younger STEMI patients (males age < 50 years, females age < 70 years) and particularly in older male patients age > 70 years. In the NSTEMI group, there was a somewhat beneficial effect similar for both sexes (see Supporting Information, Figure 3A, in the online version of this article). Moreover, HTN was associated with a significant risk reduction of estimated in‐hospital mortality with increasing age in AMI cases of both sexes, but especially in females with STEMI (see Supporting Information, Figure 3B, in the online version of this article). Contrariwise, CKD was associated with an increased risk of in‐hospital mortality in both sexes up to the age of 75 years; in STEMI, the estimated risk associated with CKD is higher in males compared with females, whereas in NSTEMI no relevant sex‐related difference could be displayed (see Supporting Information, Figure 3C, in the online version of this article). CHF impaired in‐hospital mortality in STEMI and to a lower extent also in NSTEMI, affecting males at any age and females up to age 85 years (see Supporting Information, Figure 3D, in the online version of this article).

4. DISCUSSION

In this real‐world setting including all nationwide AMI cases from Germany in the year 2009, the frequency of AMI was markedly higher in males compared with females, with an approximate ratio of 2:1. Our data showed consistently that the manifestation of AMI in female patients appeared at an older age compared with male patients. As to the causes for this, differences in rheological, haemostatic, or inflammatory activity17, 18 might be considered, yet not completely understood. Further, younger females in particular tend in general to exhibit a more atypical presentation of symptoms,19, 20, 21 which may lead to AMI being under‐recognized more often in females compared with males, as has been seen in data from the Framingham population.22 In a recent study, female sex has been shown to be independently associated with the absence of chest pain,23 which has been reported to be a significant predictor of death in AMI.20 This seems in line with the often‐reported increased mortality of female patients.8, 11, 19

Indeed, our crude data showed a highly increased observed in‐hospital mortality of STEMI patients in females compared with males. Data from the Swedish Web System for Enhancement of Evidence‐Based Care in Heart Disease Evaluated According to Recommended Therapies (SWEDEHEART) registry24 report a comparable trend, with a poor prognosis particularly in female STEMI patients. However, this trend was driven by a high risk of cardiogenic shock in the prehospital phase, which is not covered in our analysis. Likewise to our German nationwide analysis, Redfors et al. found this effect to be highly age‐dependent, with even lower 30‐day mortality in Swedish female AMI patients. In a Polish nationwide AMI cohort, female sex was not found to increase in‐hospital mortality (OR: 0.97, P = 0.79).25 Consistently, our data on NSTEMI patients indicated a marked impact of the increased risk profile and higher age in female patients on the observed in‐hospital mortality, and adjustment resulted in an even slightly lower estimated in‐hospital mortality of females compared with males.

4.1. Impact of comorbidities

As in most studies,4, 7, 19 we found differing baseline characteristics with a more unfavorable risk constellation of females compared with males. It is controversially discussed to what extent these factors in detail have an impact on AMI morbidity, success rate of treatment, or mortality.7, 8, 11 Concomitant diagnosis of CKD led to an impaired survival in either sex, which may illustrate the dramatic impact of CKD on the cardiovascular system relating to pathological metabolic and hemodynamic changes.26, 27 CHF is associated with increased in‐hospital mortality, interestingly more often in male than in female cases. CHF may be the result of previous AMI, and therefore indicates patients with high‐risk profiles. On the other hand, patients with heart failure have previously been shown to receive deficient evidence‐based therapy.28, 29 T2DM and HTN are acknowledged risk factors for cardiovascular events2, 8; however, they were not associated with an increased in‐hospital mortality after data adjustment. Manifestation of AMI at earlier stages of cardiovascular disease in these patients may have selected younger patients with more favorable conditions in terms of short‐term outcome.

4.2. Impact of therapy

In numerous studies, females with coronary artery disease have been shown to receive optimized treatment less often, as well as a lower rate of invasive procedures.4, 30, 31 For example, data from the Swiss National Registry of Acute Myocardial Infarction (AMIS Plus) report an underuse of PCI in female acute coronary syndrome patients at an adjusted OR of 0.7 (95% CI: 0.64–0.76).3 Our real‐world‐reflecting data parallel these findings, showing that particularly elderly female patients with AMI receive CA, PCI, or CABG less often compared with males. As an underlying cause, a potentially worse eligibility of the more multimorbid female patients, combined with a higher periprocedural risk, is broadly discussed.4, 7, 32, 33 In STEMI, the observed undertreatment therefore may at least partially contribute to the slightly increased overall in‐hospital mortality in older females compared with males. Parallel to our findings, a smaller German population‐based registry34 showed female sex to be independently associated with a higher chance for noninvasive treatment strategy (OR: 1.28, P = 0.002). Invasive treatment strategy in this cohort was inversely associated with the 28‐day case facility rate in female AMI patients irrespective of age, substantiating the expected benefit. Polish nationwide data show invasive treatment to be less frequently applied in female patients (OR: 0.84, P < 0.0001) against the background of in‐hospital mortality rates being lowest in the invasively treated subgroup.25 Also, the circumstances surrounding initial admission seem to have a profound impact on the choice of (invasive) therapeutic options. Udell et al.. showed equally improved 90‐minute door‐to‐balloon time between 2003 and 2008 in male and female AMI patients; however, there was a modestly lower achievement of this goal in young women in particular.35

In the NSTEMI group, the lower rate of CA in females did not reflect a similarly lower overall mortality. In fact, in the Fragmin and Fast Revascularisation During Instability in Coronary Artery Disease II (FRISC‐II)36 and Third Randomized Intervention Treatment of Angina (RITA‐3) trial,37 females with NSTEMI did not seem to benefit significantly from an early invasive therapy compared with a conservative strategy. Also, data from the international CLARIFY registry on patients with stable coronary artery disease showed outcome after 1 year not to differ significantly38 between male and female patients, although females received noninvasive diagnostic testing less often and underwent invasive procedures less often. However, Tillmanns et al.. showed equally successful results in both sexes for early revascularization in STEMI, and an even better adjusted short‐term outcome in females compared with males.39 These findings are further substantiated by Treat Angina With Aggrastat and Determine the Cost of Therapy With Invasive or Conservative Strategy–Thrombolysis In Myocardial Infarction 18 (TACTICS‐TIMI 18)40 and an observational study of the Bad Krozingen area in Germany,41 which confirmed a benefit from an early invasive therapy in females with acute coronary syndrome. As suggested by Hochmann et al, differing inclusion criteria and varying baseline risk scores may have contributed to the conflicting results.42 Despite all these reservations, our adjusted data substantiate a reduction of in‐hospital mortality in STEMI and NSTEMI patients following CA, among all age groups and in both sexes.

4.3. Study limitations

The large database allowing for a nationwide analysis in a real‐world scenario is a major strength of our analysis. The logistic regression model designed for sex‐focused statistical data processing provides a reliable validity beyond a purely descriptive character of many other previous studies. The use of the German DRG system serves as a dependable data source, because all hospitals are legally obligated to transfer their data to the DESTATIS for remuneration purposes. Further, diagnostic and procedural codes are automatically cross‐checked by specific software, and > 20% of diagnoses are additionally verified for accuracy by special physicians of the MDK (Medizinischer Dienst der Krankenversicherung/Medical Service of Health Insurance), who work independently from hospitals and health insurance providers. However, in the absence of peer‐reviewed validation studies, some uncertainty about the issue remains.

Further limitations comprise the following: For the estimation of mortality, the aging process was assumed to be linear or quadratic, as these models are frequently used to test the effects of sex and age. However, these statistical models typically have limited accuracy at the upper and lower bounds of the age distribution due to the smaller case numbers. It is reasonable to assume that other age‐dependent covariates not available in the German federal database may further contribute to these deviations. Due to the configuration of the database, which does not include intersecting sets between multiple encoded diagnoses, possible interdependencies of comorbidities cannot be addressed. With regard to the utilization of invasive therapeutic procedures, eligibility of patients as well as further potentially confounding factors such as stage of disease at the time of referral (eg, ongoing resuscitation or death before CA could be performed) or further cardiovascular risk factors are not included in the analysis. Because medication is not encoded in the DRG system, the database does not include information on antiplatelet/anticoagulant medication or statin use. Other reasons for CA not being performed include immediate CABG surgery or denial of invasive therapy by the patient/precautionary authorized person. Regarding the number of DES‐PCI in about one‐quarter of STEMI and one‐third of NSTEMI patients undergoing PCI, this should be regarded in the temporal context of data from the year 2009. Due to the primary remuneration purpose of the data source in the healthcare system, there is a delay of several years for its scientific use; however, encoding guidelines and the respective ICD/OPS codes did not change in the meantime. Further development of new devices with increased availability and stronger guideline recommendation of DES may certainly have increased its use in the very recent past.

5. CONCLUSION

Our analysis shows CA to be associated with reduced in‐hospital mortality, particularly in patients with STEMI. In terms of utilization of invasive procedures, older female patients undergo CA less frequently compared with males. However, impaired observed in‐hospital mortality in females was largely attributed to the impact of the more unfavorable risk and age distribution in this nationwide real‐world setting. Therefore, the extent of additional benefits to expect from invasive procedures, particularly in NSTEMI patients, need to be further investigated. However, the reservations of physicians toward the treatment of female AMI patients of older age seem unfounded based on this observational statistical analysis. Moreover, further research is needed, particularly on young female AMI patients, who, as a subgroup, have a notably poor prognosis.

Supporting information

Appendix Table 1: Diagnostic and procedural codes

Appendix Table 2: Observed in‐hospital mortality

Appendix Figure 1: STEMI and NSTEMI frequency in male and female

Appendix Figure 2: Overall in‐hospital mortality in male vs. female

Appendix Figure 3: Co‐morbidities – Impact on in‐hospital mortality male vs. female A Diabetes

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors are indebted to the personnel of the Research Data Centres of the Federal Statistical Office and the Statistical Offices of the Länder for providing the original data and expert assistance during the analysis. Further, the authors would like to thank Mrs. Susanne Schüler and Dr. Christiane Engelbertz, Division of Vascular Medicine, Department of Cardiovascular Medicine, University Hospital Münster, Münster, Germany, for their technical support and contribution to this work.

Conflicts of interest

EF was supported by the DGA (Deutsche Gesellschaft für Angiologie) and has received travel support from Bard and Novartis. NMM has received travel support from Bard, Bayer, Cordis, Daiichi‐Sankyo, and Medtronic and speaker honoraria from Medac Pharma and UCB. HR has received speaker honoraria from Bristol‐Myers Squibb, Sanofi‐Aventis, Daiichi‐Sankyo, The Medicines Company, Cordis, and Novartis; has acted as a consultant for Bristol‐Myers Squibb and Pluristem; and took part in conducting multicenter trials for Bard, Bayer, Biotronik, and Pluristem. KW has received consulting fees/honoraria from Biotronik, Medtronic, Merck, and Takeda. The authors declare no other potential conflicts of interest.

Freisinger E, Sehner S, Malyar NM, Suling A, Reinecke H, Wegscheider K. Nationwide Routine‐Data Analysis of Sex Differences in Outcome of Acute Myocardial Infarction. Clin Cardiol. 2018;41:1013–1021. 10.1002/clc.22962

REFERENCES

- 1. Finegold JA, Asaria P, Francis DP. Mortality from ischaemic heart disease by country, region, and age: statistics from World Health Organisation and United Nations. Int J Cardiol. 2013;168:934–945. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Vakili BA, Kaplan RC, Brown DL. Sex‐based differences in early mortality of patients undergoing primary angioplasty for first myocardial infarction. Circulation. 2001;104:3034–3038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Radovanovic D, Erne P, Urban P, et al; AMIS Plus Investigators . Gender differences in management and outcomes in patients with acute coronary syndromes: results on 20 290 patients from the AMIS Plus Registry. Heart. 2007;93:1369–1375. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Gan SC, Beaver SK, Houck PM, et al. Treatment of acute myocardial infarction and 30‐day mortality among women and men. N Engl J Med. 2000;343:8–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Abdel‐Qadir HM, Ivanov J, Austin PC, et al. Sex differences in the management and outcomes of Ontario patients with cardiogenic shock complicating acute myocardial infarction. Can J Cardiol. 2013;29:691–696. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Fiebach NH, Viscoli CM, Horwitz RI. Differences between women and men in survival after myocardial infarction: biology or methodology? JAMA. 1990;263:1092–1096. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Hochman JS, Tamis JE, Thompson TD, et al; Global Use of Strategies to Open Occluded Coronary Arteries in Acute Coronary Syndromes IIb Investigators . Sex, clinical presentation, and outcome in patients with acute coronary syndromes. N Engl J Med. 1999;341:226–232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Vaccarino V, Parsons L, Every NR, et al. Sex‐based differences in early mortality after myocardial infarction. National Registry of Myocardial Infarction 2 Participants. N Engl J Med. 1999;341:217–225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Blöndal M, Ainla T, Marandi T, et al. Sex‐specific outcomes of diabetic patients with acute myocardial infarction who have undergone percutaneous coronary intervention: a register linkage study. Cardiovasc Diabetol. 2012;11:96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Jneid H, Fonarow GC, Cannon CP, et al; Get With the Guidelines Steering Committee and Investigators . Sex differences in medical care and early death after acute myocardial infarction. Circulation. 2008;118:2803–2810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Maynard C, Litwin PE, Martin JS, et al. Gender differences in the treatment and outcome of acute myocardial infarction: results from the Myocardial Infarction Triage and Intervention Registry. Arch Intern Med. 1992;152:972–976. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Otten AM, Maas AH, Ottervanger JP, et al; Zwolle Myocardial Infarction Study Group . Is the difference in outcome between men and women treated by primary percutaneous coronary intervention age dependent? Gender difference in STEMI stratified on age. Eur Heart J Acute Cardiovasc Care. 2013;2:334–341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Mehta LS, Beckie TM, DeVon HA, et al; American Heart Association Cardiovascular Disease in Women and Special Populations Committee of the Council on Clinical Cardiology, Council on Epidemiology and Prevention, Council on Cardiovascular and Stroke Nursing, and Council on Quality of Care and Outcomes Research . Acute Myocardial Infarction in Women: a Scientific Statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2016;133:916–947. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Mosca L, Benjamin EJ, Berra K, et al. Effectiveness‐Based Guidelines for the Prevention of Cardiovascular Disease in Women—2011 update: a guideline from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2011;123:1243–1262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Freisinger E, Fürstenberg T, Malyar NM, et al. German nationwide data on current trends and management of acute myocardial infarction: discrepancies between trials and real‐life. Eur Heart J. 2014;35:979–988. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Malyar N, Fürstenberg T, Wellmann J, et al. Recent trends in morbidity and in‐hospital outcomes of inpatients with peripheral arterial disease: a nationwide population‐based analysis. Eur Heart J. 2013;34:2706–2714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Paul L, Jeemon P, Hewitt J, et al. Hematocrit predicts long‐term mortality in a nonlinear and sex‐specific manner in hypertensive adults. Hypertension. 2012;60:631–638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Wennberg P, Wensley F, Di Angelantonio E, et al. Haemostatic and inflammatory markers are independently associated with myocardial infarction in men and women. Thromb Res. 2012;129:68–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Poon S, Goodman SG, Yan RT, et al. Bridging the gender gap: insights from a contemporary analysis of sex‐related differences in the treatment and outcomes of patients with acute coronary syndromes. Am Heart J. 2012;163:66–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Canto AJ, Kiefe CI, Goldberg RJ, et al. Differences in symptom presentation and hospital mortality according to type of acute myocardial infarction. Am Heart J. 2012;163:572–579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Kirchberger I, Heier M, Kuch B, et al. Sex differences in patient‐reported symptoms associated with myocardial infarction (from the population‐based MONICA/KORA Myocardial Infarction Registry). Am J Cardiol. 2011;107:1585–1589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Lerner DJ, Kannel WB. Patterns of coronary heart disease morbidity and mortality in the sexes: a 26‐year follow‐up of the Framingham population. Am Heart J. 1986;111:383–390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Khan NA, Daskalopoulou SS, Karp I, et al; GENESIS PRAXY Team . Sex differences in acute coronary syndrome symptom presentation in young patients. JAMA Intern Med. 2013;173:1863–1871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Redfors B, Angerås O, Råmunddal T, et al. Trends in gender differences in cardiac care and outcome after acute myocardial infarction in western Sweden: a report from the Swedish Web System for Enhancement of Evidence‐Based Care in Heart Disease Evaluated According to Recommended Therapies (SWEDEHEART). J Am Heart Assoc. 2015;4:e001995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Gierlotka M, Zdrojewski T, Wojtyniak B, et al. Incidence, treatment, in‐hospital mortality and one‐year outcomes of acute myocardial infarction in Poland in 2009–2012—nationwide AMI‐PL database. Kardiol Pol. 2015;73:142–158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Go AS, Chertow GM, Fan D, et al. Chronic kidney disease and the risks of death, cardiovascular events, and hospitalization [published correction appears in N Engl J Med 2008;18:4]. N Engl J Med. 2004;351:1296–1305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Raggi P, Boulay A, Chasan‐Taber S, et al. Cardiac calcification in adult hemodialysis patients: a link between end‐stage renal disease and cardiovascular disease? J Am Coll Cardiol. 2002;39:695–701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Zhang H, Goodman SG, Yan RT, et al; Canadian GRACE and CANRACE Investigators . In‐hospital management and outcomes of acute coronary syndromes in relation to prior history of heart failure. Eur Heart J Acute Cardiovasc Care. 2016;5:214–222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Desta L, Jernberg T, Löfman I, et al. Incidence, temporal trends, and prognostic impact of heart failure complicating acute myocardial infarction. The SWEDEHEART Registry (Swedish Web‐System for Enhancement and Development of Evidence‐Based Care in Heart Disease Evaluated According to Recommended Therapies): a study of 199 851 patients admitted with index acute myocardial infarctions, 1996 to 2008. JACC Heart Fail. 2015;3:234–242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Ayanian JZ, Epstein AM. Differences in the use of procedures between women and men hospitalized for coronary heart disease. N Engl J Med. 1991;325:221–225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Kostis JB, Wilson AC, O'Dowd K, et al; MIDAS Study Group . Sex differences in the management and long‐term outcome of acute myocardial infarction: a statewide study. Myocardial Infarction Data Acquisition System. Circulation. 1994;90:1715–1730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Akhter N, Milford‐Beland S, Roe MT, et al. Gender differences among patients with acute coronary syndromes undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention in the American College of Cardiology–National Cardiovascular Data Registry (ACC‐NCDR). Am Heart J. 2009;157:141–148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Kudenchuk PJ, Maynard C, Martin JS, et al. Comparison of presentation, treatment, and outcome of acute myocardial infarction in men versus women (the Myocardial Infarction Triage and Intervention Registry). Am J Cardiol. 1996;78:9–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Amann U, Kirchberger I, Heier M, et al. Predictors of non‐invasive therapy and 28‐day‐case fatality in elderly compared to younger patients with acute myocardial infarction: an observational study from the MONICA/KORA Myocardial Infarction Registry. BMC Cardiovasc Disord. 2016;16:151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Udell JA, Fonarow GC, Maddox TM, et al; Get With the Guidelines Steering Committee and Investigators . Sustained sex‐based treatment differences in acute coronary syndrome care: insights from the American Heart Association Get With the Guidelines Coronary Artery Disease Registry. Clin Cardiol. 2018. doi: 10.1002/clc.22938 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Lagerqvist B, Säfström K, Ståhle E, et al; FRISC II Study Group Investigators . Is early invasive treatment of unstable coronary artery disease equally effective for both women and men? J Am Coll Cardiol. 2001;38:41–48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Clayton TC, Pocock SJ, Henderson RA, et al. Do men benefit more than women from an interventional strategy in patients with unstable angina or non–ST‐elevation myocardial infarction? The impact of gender in the RITA 3 trial. Eur Heart J. 2004;25:1641–1650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Fox KA, Goodman SG, Klein W, et al. Management of acute coronary syndromes: variations in practice and outcome. Findings from the Global Registry of Acute Coronary Events (GRACE). Eur Heart J. 2002;23:1177–1189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Tillmanns H, Waas W, Voss R, et al. Gender differences in the outcome of cardiac interventions [article in English, German]. Herz. 2005;30:375–389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Glaser R, Herrmann HC, Murphy SA, et al. Benefit of an early invasive management strategy in women with acute coronary syndromes. JAMA. 2002;288:3124–3129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Mueller C, Neumann FJ, Roskamm H, et al. Women do have an improved long‐term outcome after non–ST‐elevation acute coronary syndromes treated very early and predominantly with percutaneous coronary intervention: a prospective study in 1450 consecutive patients. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2002;40:245–250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Hochman JS, Tamis‐Holland JE. Acute coronary syndromes: does sex matter? JAMA. 2002;288:3161–3164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Appendix Table 1: Diagnostic and procedural codes

Appendix Table 2: Observed in‐hospital mortality

Appendix Figure 1: STEMI and NSTEMI frequency in male and female

Appendix Figure 2: Overall in‐hospital mortality in male vs. female

Appendix Figure 3: Co‐morbidities – Impact on in‐hospital mortality male vs. female A Diabetes