Summary

Aims

Remote ischemic conditionings, such as pre‐ and per‐conditioning, are known to provide cardioprotection in animal models of ischemia. However, little is known about the neuroprotection effect of postconditioning after cerebral ischemia. In this study, we aim to evaluate the motor function rescuing effect of remote limb ischemic postconditioning (RIPostC) in a rat model of acute cerebral stroke.

Methods

Left middle cerebral artery occlusion (MCAO) was performed to generate the rat model of ischemic stroke, followed by daily RIPostC treatment for maximum 21 days. The motor function after RIPostC was assessed with foot fault test and balance beam test. Local infarct volume was measured through MRI scanning. Neuronal status was evaluated with Nissl's, HE, and MAP2 immunostaining. Lectin immunostaining was performed to evaluate the microvessel density and area.

Results

Daily RIPostC for more than 21 days promoted motor function recovery and provided long‐lasting neuroprotection after MCAO. Reduced infarct volume, rescued neuronal loss, and enhanced microvessel density and size in the injured areas were observed. In addition, the RIPostC effect was associated with the up‐regulation of endogenous tissue kallikrein (TK) level in circulating blood and local ischemic brain regions. A TK receptor antagonist HOE‐140 partially reversed RIPostC‐induced improvements, indicating the specificity of endogenous TK mediating the neuroprotection effect of RIPostC.

Conclusion

Our study demonstrates RIPostC treatment as an effective rehabilitation therapy to provide motor function recovery and alleviate brain impairment in a rat model of acute cerebral ischemia. We also for the first time provide evidence showing that the up‐regulation of endogenous TK from remote conditioning regions underlies the observed effects of RIPostC.

Keywords: cerebral ischemia, rehabilitation, remote limb ischemic postconditioning, tissue kallikrein

1. INTRODUCTION

Stroke is a leading cause of death and disability worldwide. Patients surviving stroke still suffer devastating sensory and motor deficits including lack of coordination and partial paralysis. One of the major pathological outcomes of ischemic stroke is cerebral infarction, which causes great damage to ischemic brain regions, particularly to local neurons. Rescuing of the impaired locomotor function and reduction in the cerebral infarction are two main aims for the establishment and optimization of an effective poststroke therapy.

The concept of remote ischemic conditioning was first raised in 1993, in which a protection of the myocardium from ischemia/reperfusion injury by a short period of coronary artery occlusion was observed.1 In general, remote ischemic conditioning represents an experimental intervention which is designed to improve local ischemia through an induction of a distal sub‐lethal ischemic insult. Remote ischemic pre‐ and per‐conditionings stand for a distal ischemic insult before and during the local ischemia, respectively, both of which have been proved to be highly effective against ischemia in animal models.2, 3, 4, 5, 6 Besides, the ischemic preconditioning has been shown highly valuable in clinical application for the prevention of recurrent stroke.7 However, due to the unpredictability and acuteness of cerebral ischemia, the onset and progression of it could not be efficiently prevented by the neuroprotection effect of pre‐conditioning and per‐conditioning.8 In contrast, remote ischemic postconditioning mainly represents a distal intervention after the acute onset of local ischemia, making it a good candidate for poststroke rehabilitation. Accumulating evidence suggests that ischemic postconditioning in various distal regions might result in considerable protections in heart, liver, lung, kidney, and brain regions of animal models such as rat, rabbit, and pig.3, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13 In cerebral ischemia, reduced infarct size,10 rescued neuronal apoptosis,13 and ameliorated functional outcomes 14 were commonly observed after remote postconditioning. However, the potential therapeutic application of remote postconditioning is still inconclusive.

Tissue kallikrein (TK; kallidinogenase) is a serine protease specifically acting in the release of the potent vasoactive peptides bradykinin and Lys‐bradykinin.15 The biological effects of kinins are mediated by B1 and B2 transmembrane receptors.16 In ischemic stroke, TK has shown protection effect through multiple pathways such as inhibition of apoptosis,17 inhibition of inflammation, promotion of angiogenesis, and neurogenesis.18 In clinical, intravenous injection of exogenous TK such as human urinary kallidinogenase has been used as a treatment for acute ischemic stroke. However, few studies have focused on endogenous TK and its therapeutic effects on acute ischemic stroke. Notably, endogenous bradykinin stimulation has been implicated as one of several potential mechanisms underlying remote ischemic conditioning,19 leading us to consider the possibility of endogenous TK as a critical mediator linking remote ischemic postconditioning and its potential application in stroke treatment.

To test the effectiveness and efficiency of remote limb ischemic postconditioning (RIPostC) in poststroke neuro‐rehabilitation, daily short‐term hind limb ischemia was performed for maximum 21 days with rat models of cerebral ischemia. To clarify the potential roles of TK mentioned above, TK antagonist HOE‐140 was injected after RIPostC. Locomotor function, infarct sizes, structure, and neuronal damage of the ischemic areas were then examined.

2. MATERIALS AND METHODS

2.1. Experimental design

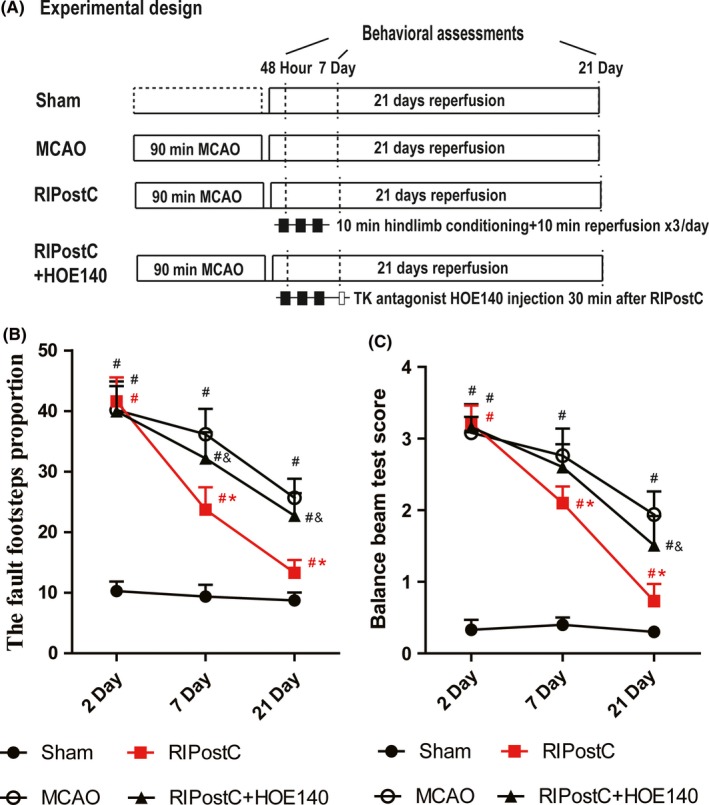

Four experimental groups were designed, each group contains 10 rats: sham‐operated, MCAO, RIPostC, and RIPostC+HOE140 injection. RIPostC were performed 2 days after MCAO and HOE140 injection was performed 30 minutes after RIPostC. For detailed illustration, see Figure 1A.

Figure 1.

Effect of RIPostC on locomotor function recovery. A, illustration of experimental design. B, foot fault test measuring the fault footsteps proportions of four experimental groups at three time points, the higher proportion indicating severer dysfunction of the limb affected. C, balance beam test measuring the locomotor capability of the four experimental groups, the higher score indicating a worse locomotor outcome. Data are expressed as mean ± SD, n = 10/group. # P < 0.05 vs Sham, *P < 0.05 vs MCAO, & P < 0.05 vs RIPostC

2.2. Rat model of cerebral stroke

A cerebral ischemic rat model20 was employed to investigate the effect of RIPostC on brain functional recovery. Male Sprague–Dawley rats (250‐300 g) were obtained from Shanghai SIPPR‐BK LAB Animal Ltd., Shanghai, China (license number: SCXK (Hu) 2013‐0016) and were housed under diurnal lighting conditions (12 hours darkness/light). Experiments were performed according to the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of Fudan University (Shanghai, China). The experimental protocol was approved by the Department of Laboratory Animal Science, Fudan University (approval number: 20140143C001). To generate MCAO model, rats were anesthetized with 10% chloral hydrate (0.36 mL/100 g, intraperitoneal). The body temperature of the rats was maintained at 37°C with a heating pad. Surgical procedures for MCAO and reperfusion were performed as previously reported.20 Briefly, a midline incision about 2 cm was made in the neck skin, and the left carotid artery, external carotid artery, and internal carotid artery were carefully isolated. A filament with a poly‐L‐lysine coated blunted tip was used to occlude rats’ left middle cerebral artery. The length of the filament inserted through the internal carotid artery was approximately 20 mm. The blood flow was monitored using laser Doppler anemometry (Moor Instruments Ltd, Miuwev AxIllinster, EXl3 5HU, UK) to make sure its loss reached 70% to 80%. After a 1.5‐hour occlusion, the filament was withdrawn and reperfusion was established. After recovering from anesthesia, the neurologic deficits were measured with a five‐point scale. Rats with scores of 1‐3 were considered successful models and included in the study and the rats with a score of 0 or 4 were excluded from the study. Rats in the sham‐operated group underwent the MCAO procedures without insertion of the filament and occlusion of the middle cerebral artery.

2.3. Procedure of RIPostC

We hypothesize that RIPostC might help alleviate the brain damage and rescue the motor dysfunction after cerebral ischemia. RIPostC was performed as previously described.21 Briefly, 2 days after MCAO, rats in the RIPostC and HOE‐140 groups underwent remote limb conditioning through tight hind limb restriction with thin elastics for 10 min followed by 10 min of reperfusion, and the conditioning was repeated three times one after another daily for 21 consecutive days. Limb ischemia was confirmed by the pale color and the underskin temperature decrease of the limb (>3°C).

2.4. Administration of HOE‐140

The selective bradykinin B2 receptor antagonist HOE‐140 was chosen to inhibit the potential effect of kallikrein due to its high specificity, long duration of action, and good tolerability.22 HOE‐140 (100 μg/kg) dissolved in 0.9% NaCl was intraperitoneally injected in the rats 30 min after RIPostC as previously described.23

2.5. Foot fault test

The foot‐fault test assessed placement dysfunction of affected limb. A horizontal ladder with 34 rods (2‐cm interval between adjacent rods) was used as previously described.24 All animals were trained on this system before the first test. If the forelimb of the affected side fell off or slipped through the rod, this was counted as one fault footstep. The percentage of foot faults of the right paw out of total steps was calculated. The higher score represents a worse functional outcome. The test was repeated three times for each rat by a rater blinded to the group division and was performed at 48 hours, 7 days, and 21 days after surgery. Functional test was performed by an investigator adequately trained in functional measurements and blinded to the experimental groups.

2.6. Balance beam test

The balance beam walking test was used to evaluate the ability of rats to maintain balance while walking along an elevated beam, thus reflecting their gross motor function and balance ability. The apparatus consisted of a 1.5‐m beam with a flat surface of 25 mm width resting 55 cm above the table top on two poles. A box was placed at the end of the beam as the finish point. Before the first test, rats were trained to walk on the beam from one end to the other. The test was repeated three times for each rat by a rater blinded to the group division. The test was performed before, and at 48 hours, 7 days, and 21 days after surgery. A 5‐point scale was adopted in the test as follows: 0, the rat was able to balance and walk on the beam using its forelimbs symmetrically; 1, the rat was able to balance and walk on the beam using its unaffected limb preferentially; 2, the rat was able to balance and walk on the beam mostly relying on the unaffected limb; 3, the rat was not able to balance on the beam once moved; 4, the rat fell off the beam immediately. The average scores were calculated for statistical analysis. The higher score represented a worse functional outcome.

2.7. Measurement of TK levels

Two micromole blood was extracted through external jugular vein, followed by 2500 r/min centrifugation for 10 minutes at 4°C. TK levels were measured using commercial enzyme‐linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) kit, according to manufacturer's guidelines (Rat kallikrein 1 ELISA Kit; CUSABIO BIOTECH CO., LTD, China; CSB‐EL012446RA). All samples were tested in triplicates. Concentrations were calculated from a standard curve and expressed in nanogram per milliliter. The threshold for detection was 0.23 ng/mL.

2.8. Western blotting analysis

For brain tissue preparation, rats were sacrificed under anesthesia at 48 hours, 72 hours, 5 days, 10 days, 15 days, and 21 days after 90 minutes of MCAO. Western blotting analysis was carried out on 10% SDS‐PAGE. Proteins were electro‐transferred onto nitrocellulose filters (pore size 0.45 μm). After blocking for 3 hours in phosphate‐buffered saline (PBS) with 0.1% Tween‐20 (PBST) and 3% bovine serum albumin (BSA), the membranes were incubated overnight with primary antibody (KLK1, Santa Cruz; Actin, Cell Signaling) in PBST containing 3% BSA. Detection was carried out by the use of proper alkaline phosphatase‐conjugated IgG and developed with an NBT/BCIP assay kit (Promega, Madison, WI). After immunoblotting, the density of the bands was scanned with an image analyzer (LabWorks Software UVP, Upland, CA).

2.9. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scanning

MRI scanning was performed on a 7.0 Tesla MRI scanner (BioSpec 70/20 USR, Bruker, Germany). Animals were anesthetized and anchored in prone position on a scanning bed, with head fixed. T2 weighted images (T2WI) sequence was scanned (TR = 3162 ms, TE = 33 ms, sampling matrix 256 × 256, slice thickness 1.0 mm, layer spacing 0 mm, 30 layers in all, visual field 3.0 × 3.0 cm). Lesion volume, tissue losses were quantified.

2.10. Histopathological examination

Hematoxylin–eosin (HE) staining and Nissl's staining were employed to observe the pathological change and the morphological features of injured neurons in the cerebral cortex. 21 days after surgery, rats were sacrificed, and the brains were fixed by transcardial perfusion with saline solution, followed by perfusion and immersion in 4% paraformaldehyde. Brains were then dehydrated in a graded series of alcohols and embedded in paraffin. A series of 4‐μm‐thick sections were cut from the block. Finally, the sections were stained with HE and Nissl's reagents. The slices were observed and photographed with an Olympus BX53 microscope (Tokyo, Japan).

2.11. Immunofluorescence analysis

Immunofluorescent staining of MAP2 (Santa Cruz) for brain tissue was performed on fixed frozen ultra thin sections as previously described.25 Two areas in each section were chosen at random and photographed by an investigator blinded to the experimental groups. For microvessel immunostaining, samples were incubated with fluorescein lycopersicon esculentum (tomato) lectin (1:1000; Vector laboratories, Burlingame, CA) for 1 hour, rinsed with PBS and directly mounted with mounting medium containing Hoechst dye. To quantify the microvessel density, vessel branch points were averaged as positive branch points per field. To quantify the size of microvessels, the percentage of microvessel area per relative to total analyzed field were measured.26

2.12. Statistical analysis

All experimental data were analyzed using SPSS20.0 software. Multi‐group comparisons of the means were carried out by one‐way analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by Fisher's least square difference post hoc test. For behavioral tests, four experimental groups were compared with each other, and the animal number of each group is 10. t‐test was applied when only two groups were compared. P < 0.05 was considered as statistically significant. Data are presented as mean ± standard deviation (SD).

3. RESULTS

3.1. RIPostC results in functional recovery of cerebral ischemic rats

RIPostC was performed daily for 48 hours, 7 and 21 days, respectively. The rats undergoing no MCAO were used as sham‐operated group. Two functional tests, including a foot fault test and a balance beam test, were performed after each time point to assess the motor impairment of limb functioning of the rats (experimental design illustrated in Figure 1A). As shown in Figure 1B and C, compared with sham‐operated group, MCAO caused severe loss of function in all three time points, suggesting the successful generation of our stroke animal model. Interestingly, 7 days of RIPostC remarkably reduced the fault foot step proportion (Figure 1B; RIPostC 23.72 ± 3.68% vs MCAO 36.17 ± 4.19%) and 21 days of RIPostC resulted in a more dramatic recovery (Figure 1B; RIPostC 13.31 ± 2.09% vs MCAO 25.68 ± 3.13%), while no significant difference was observed at 2 days of RIPostC. In balance beam test, MCAO caused an increased score of imbalance in all three time points. Consistently, RIPostC for 7 and 21 days significantly alleviated the balancing dysfunction compared with MCAO‐operated group (Figure 1C). These data strongly indicated that a long‐term RIPostC therapy can help relieve the functional disability after cerebral ischemia.

Notably, an additional daily treatment of HOE‐140 (Icatibant), a peptidic bradykinin B2 receptor antagonist, partially but significantly blocked the RIPostC‐induced reduction of fault foot step proportion as well as imbalance score on days 7 and 21, suggesting that the kallikrein–kinin system might mediate the long‐term recovery effect of RIPostC.

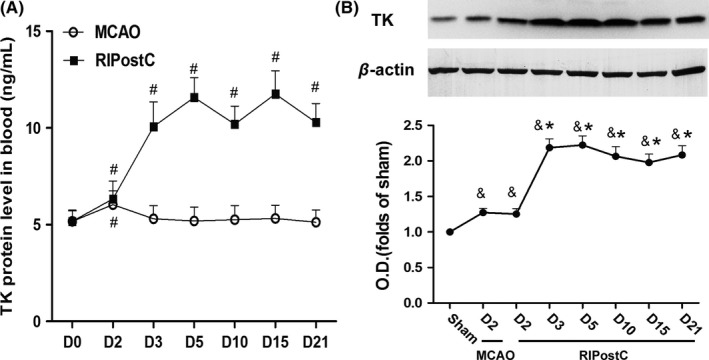

3.2. Tissue kallirein level in blood is increased after RIPostC

To give insight into the role of kallikrein–kinin system in RIPostC, an ELISA assay was performed with differential blood samples harvested from different days of RIPostC to detect the TK expression in the blood. MCAO slightly increased TK level in the first 48 hours of MCAO, but the level returned to baseline after 72 hours. Despite of the similar level with MCAO group in the first 48 hours, RIPostC strikingly increased the blood TK expression in 72 hours, and the level remained high for the last 18 days (Figure 2A; 72 hours, 10.774 ± 1.268 ng/mL; 5 days 11.379 ± 0.934 ng/mL; 10 days, 11.194 ± 0.934 ng/mL; 15 days, 11.194 ± 1.198 ng/mL, 21 days, 10.967 ± 0.973 ng/mL). This result indicated that RIPostC was able to cause increase in TK in the circulating blood. To assess TK level in brain local ischemia region, Western blotting analysis was performed with tissue samples harvested from the temporoparietal cortex of rats. Forty‐eight hours after MCAO, local TK level in RIPostC group was similar to the level in MCAO group, both of which were slightly increased compared to sham group. However, TK level was greatly increased from 72 hours of RIPostC and sustained in high level for at least 18 days (Figure 2B). The ascending trend and onset time of local TK level were consistent with TK level in the blood, suggesting a possible TK delivery from distal conditioning region toward local ischemia region due to RIPostC. Taken together, our results showed that an over 3‐day daily RIPostC increased the endogenous TK level in both blood and ischemic area, suggesting the potential role of TK in RIPostC effect. Thus, to further reveal the potential role of kallikrein–kinin in our RIPostC therapy, RIPostC+HOE‐140 treatment was included in all the following experiments.

Figure 2.

Elevation of TK levels in circulating blood and ischemic regions by RIPostC. A, TK protein level in circulating blood at various time points in groups with or without RIPostC. B, Western blotting analysis of TK protein expression in local ischemic regions. β‐actin was used as control. Upper is the representative images, and lower is the quantification of the band density. As local TK level in Sham remained stable in 21 days, only D2 Sham is shown. Data are expressed as mean ± SD, n = 5/group. # P < 0.05 vs D0, & P < 0.05 vs Sham; *P < 0.05 vs D2 RIPostC

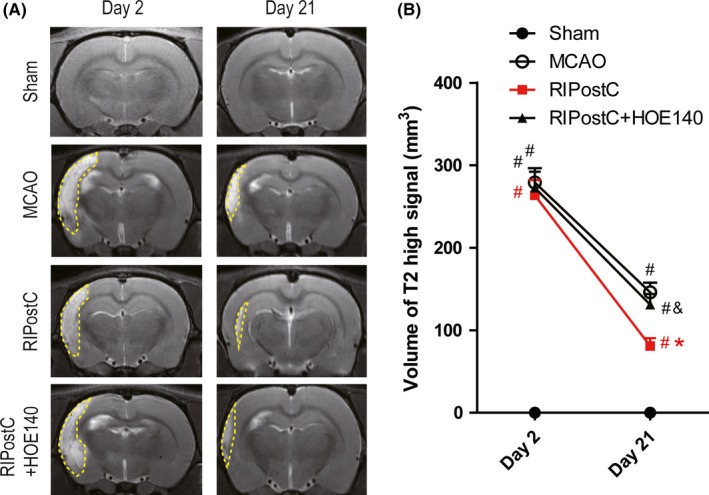

3.3. RIPostC reduces cerebral infarction volume and attenuates neuronal cell death after cerebral ischemic injury

To look into the pathological outcomes of RIPostC, multiple imaging analyses were applied to assess the cerebral infarct volume and neuronal survival at the ischemic brain regions. The infarct volume was monitored by MRI scanning and shown by T2 weighted imaging. No distinguished abnormalities were seen in the sham‐operated group at 2 days and 21 days after surgery (Figure 3A). By contrast, high T2WI signals were detected in the ischemic cerebral cortex 2 days and 21 days after MCAO (Figure 3A, yellow dotted lines), suggesting severe and lasting induction of cerebral infarction volumes due to MCAO injury. The infarction volume was not reduced after 2 days of RIPostC therapy (Figure 3A). However, after 21 days of RIPostC, a significant reduction in infarction volume was seen (Figure 3A). Quantification of the volume of high T2WI signals showed an up to 44.52% reduction of the infarct size by RIPostC compared to MCAO (Figure 3B; RIPostC 81.01 ± 9.54 mm3 versus MCAO 146 ± 11.67 mm3). Interestingly, additional treatment of HOE‐140 for 21 days partially but significantly reversed the rescuing effect of RIPostC on infarction volume (RIPostC+HOE‐140 131.12 ± 12.96 mm3 versus RIPostC 81.01 ± 9.54 mm3).

Figure 3.

Effect of RIPostC on infarct volume reduction. A, Representative MRI T2 weighted images of the 15th layer of the brains coronally scanned at two time points (2 days, 21 days after MCAO). The ischemic regions are marked with yellow dotted lines. B, quantification of T2 high signal volumes of four experimental groups. Data are expressed as mean ± SD, n = 10/group. # P < 0.05 vs Sham, *P < 0.05 vs MCAO, & P < 0.05 vs RIPostC

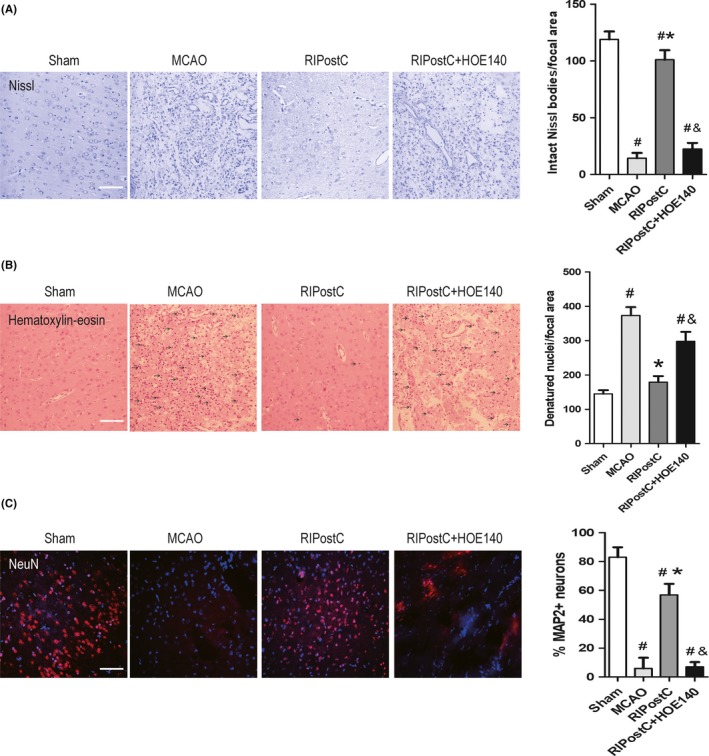

To look into the rescuing effect of RIPostC on local neurons, the rat brains were sectioned 21 days after MCAO injury and the neuronal morphology and number at ischemic region was examined by pathohistological Nissl's and HE staining. In Nissl's staining, MCAO caused swelling morphology, disordered distribution, and shrunk Nissl bodies of cells at ischemic core, while RIPostC greatly rescued the situation. Importantly, the rescuing effect was partially blocked by the additional treatment of HOE‐140 (Figure 4A, left). Quantification analysis showed that the cell number with intact Nissl bodies in RIPostC group was comparable to Sham group, which was completely different to that in MCAO and HOE‐140 group (Figure 4A, right). In support of this, HE staining showed that MCAO caused frequent vacuolization and pyknotic dead cells, and in RIPostC group, these pathologies were much less severe. Additional treatment of HOE140 with RIPostC worsened those pathologies to the level similar with MCAO (Figure 4B, left). The quantification result of denatured nuclei from HE staining showed similar trend as in Nissl's staining (Figure 4B, right). To characterize the cells lost at the ischemic regions, we performed fluorescence immunostaining of neuronal marker MAP2 and found that MAP2+ neurons were present as the major cell type (83.06 ± 6.89%) in cerebral cortex of sham‐operated brain. MCAO significantly eliminated MAP2+ neurons (5.94 ± 7.31%) at the same region. By contrast, RIPostC largely restored the percentage to 56.93 ± 7.64%, the effect of which was abolished by additional HOE‐140 (7.03 ± 3.25%; Figure 4C). These results strongly suggested a neuronal rescuing effect of RIPostC. Taken together, our results indicated that RIPostC therapy could rescue the pathological outcomes of ischemic stroke, suggesting the importance of kallikrein–kinin system in RIPostC process.

Figure 4.

Effect of RIPostC on cell morphology and neuronal loss at ischemic brain regions. A, representative images of Nissl's staining from same ischemic regions (cortex) of four experimental groups. Left panel showing MCAO‐induced disappearance of normal Nissl body structure in the cytoplasm, accumulation of staining dye in pathological cell nuclei, and its protection effect by RIPostC. Right is the quantification of intact cell number in Nissl's staining (clear and large Nissl bodies). B, representative images of HE staining. Left panel showing significantly increased vacuoles and pyknotic cells (indicated with arrow) after MCAO and its protection effect by RIPostC. Note the prevention of RIPostC effect by HOE140. Right is the quantification of denatured cell number in HE staining. C, left is the representative immunoflurescence images of NeuN+ neurons in four experimental groups. Cell nuclei were stained with Hoechst. Right is the quantification of percentage of NeuN+ cell number. Data are expressed as mean ± SD, n = 10/group. # P < 0.05 vs Sham, *P < 0.05 vs MCAO, & P < 0.05 vs RIPostC. Scale bar = 50 μm

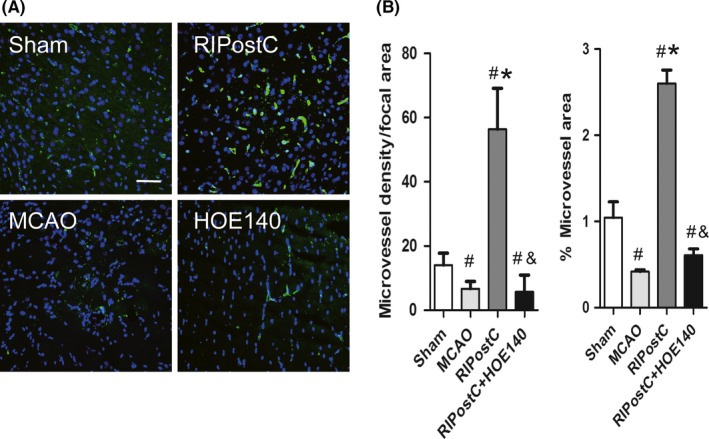

3.4. RIPostC increases microvessel density in ischemic area

Angiogenesis is often observed after ischemia and believed to be involved in damage recovery. Microvessel density was evaluated in the ischemic area 21 days after MCAO injury by lectin immunohistochemistry. MCAO caused severe reduction in lectin + microvessels compared with sham‐operated group (Figure 5A). Notably, the quantity of lectin + microvessels was significantly increased after RIPostC treatment, together with the enhanced microvessel size (Figure 5B). By contrast, HOE‐140 co‐treatment resulted in lower microvessel density and size, to the similar level of MCAO group (Figure 5A and B).

Figure 5.

Effect of RIPostC on microvessel growth at ischemic brain regions. A, representative images of lectin immunostaining to mark the microvessels. B, quantification of microvessel density (number of Lectin+ vascular profiles per focal area) and microvessel area (percentage of Lectin+ vascular area relative to total analyzed focal area). Cell nuclei were stained with Hoechst. Data are expressed as mean ± SD, n = 10/group. # P < 0.05 vs Sham, *P < 0.05 vs MCAO, & P < 0.05 vs RIPostC. Scale bar = 50 μm

4. DISCUSSION

RIPostC is a new postconditioning procedure with great potential for neuroprotection following ischemic insult. In this study, we investigated the application and outcome of RIPostC in a rat stroke model as a rehabilitation therapy for acute stroke. Rescued motor function, reduced infarct volume, improved neuronal survival of infarct region, and increased vascular density were observed after daily RIPostC treatment for more than 7 days. We further identified increased endogenous TK levels in blood and ischemic brain tissue, suggesting that enhanced TK signaling pathway might at least partially underlie the observed RIPostC effect. This proposed mechanism was evidenced by the fact that the treatment of TK antagonist HOE‐140 partially reversed all of the improvements resulted from long‐term RIPostC mentioned above. To our knowledge, our findings have not been reported in any other studies previously.

The purpose of using MCAO rodent model is to replicate the onset and progress of acute cerebral stroke in human. MCAO‐induced neurological deficits such as motor uncoordination and asymmetry serve as good scales to assess the recovery efficacy of RIPostC for the future optimization and application of this rehabilitation therapy on stroke patients. The foot fault test is a sensitive indicator for detecting functional impairment of both forelimbs and hindlimbs after cerebral ischemia in rodents, while the balance beam test is a more specific assessment for hindlimb placing deficits.27 In our study, both tests showed significant difference between RIPostC and nonconditioning groups, confirming the reliability and validity of RIPostC on overall motor recovery. Furthermore, the balance beam test is also a good assessment to show motor learning, as its experimental procedure requires pretraining until the animal can successfully walk across the beam without turning around or making faults.28 Although we did not distinguish motor learning from motor recovery in this work, the consistency of foot fault test result might suggest that the motor recovery effect is the most striking, if not all, functional outcomes of RIPostC for the poststroke therapy. Tests regarding other neurological deficits such as sensory capacities and dexterity should be performed in the future to explore other potential benefits of RIPostC.

Spontaneous recovery is often observed long term after stroke in both human patients and rodent animal models, which might conceal some of the effects of rehabilitation. We noticed a spontaneous recovery in behavioral tests as well as pathological outcomes 21 days after MCAO. However, the RIPostC could further induce at least twice functional and pathological recoveries as great as the spontaneous one. Notably, TK level remained in the basal level in MCAO group starting from 72 hours to 21 days after MCAO injury, suggesting that increased TK was not the consequence of spontaneous recovery but a RIPostC‐specific one in our rat model. The evidence that RIPostC provides additional benefits together with spontaneous recovery might support the further optimization of RIPostC procedure and its potential translational applications.

The pathological outcomes in our study are consistent with other researches documented. 7.0 T MRI was used to detect infarct area and a significant reduction in infarct volume was found in RIPostC group at 21 days postischemic. This finding is supported by studies showing that RIPostC could reduce the reperfusion injury, edema, blood–brain barrier permeability, and the final infarct size.2, 5 It has been recently shown that RIPostC could stop the onset of neurodegeneration and prevent occurrence of massive cell necrosis effectively, and the surviving neurons retained a substantial part of their learning and memory ability.10 In line with this, our data demonstrate that RIPostC therapy reduced the average severity score of pathology in the brain. Despite the fact that MAP2+ neurons were greatly lost in the ischemic core of MCAO group, both Nissl and HE staining showed seemingly more cell number in the pathological area. This is likely due to an inflammatory gliosis represented by enhanced recruitment of GFAP+ glial cells (data not shown) as well as structure alteration resulting in accumulation of more cells in the optical view.

Repeated short ischemic stimuli was shown to reduce critical ischemic injury by promoting angiogenesis and increasing cerebral blood flow (CBF).13 We found that the density of lectin+ microvessels was significantly increased after RIPostC therapy. Despite the low possibility that microvessels were less eliminated by RIPostC, it might more likely suggest that RIPostC promoted capillary regeneration and improved collateral circulation. It is also likely that the effectiveness of TK from remote region was agonized by the increased microvessels and CBF.

To date, most studies regarding RIPostC are observational, with its underlying mechanisms to be elucidated. A number of key molecules and signaling pathways have been connected to preconditioning in the nervous system, such as delta opioid receptor, GABA receptor, nitric oxide, adenosine, growth factors, mitochondrial, and nuclear survival proteins. We propose here a necessary role of TK in RIPostC‐induced functional and pathological outcomes. TK is known as an important mediator of functional recovery following brain injury. It cleaves low molecular weight kininogen to produce bradykinin, which is subsequently bound to the kinin B2 receptor to elicit an array of biological effects.15, 29 The kinin B2 receptor is constitutively expressed with a wide tissue distribution, but can be blocked by the B2 receptor antagonist icatibant (HOE‐140). No potential off‐target effects were observed due to the high potency, good tolerability, and appropriate dose of HOE‐140 we used in our work.

Neuroprotective effects were observed upon local injection of the human TK gene into rat brain immediately after cerebral I/R injury. A double‐blinded clinical trial showed TK has an effective treatment for patients with acute brain infarction when infused within 48 hours.30 The protector mechanism was related with an inhibition of apoptosis, inflammation,31 hypertrophy, and fibrosis, as well as an enhancement of neovascularization.32 It has been clearly established that TK has pro‐angiogenic activity.33 Exogenous TK is a promising regimen in the treatment of ischemic stroke in humans. However, the use of exogenous TK in the clinic is limited, due to its commercial unavailability and inconvenient intravenous administration. Intriguingly, we observed here a significant increase in endogenous TK levels and capillary density after RIPostC and verify it as the underlying mechanism of observed RIPostC outcomes. Our study suggests that an up‐regulation of endogenous expression of TK by RIPostC might compensate those usage disadvantages of exogenous TK.

5. CONCLUSIONS

Our results highlight the RIPostC as a potential poststroke therapy to rescue the disability and reduce pathological indices in ischemic areas through the up‐regulation of endogenous TK from remote conditioning regions. We propose that RIPostC might serve as feasible, inexpensive, clinically relevant, and safe therapy for the rehabilitation of cerebral stroke.

6. ACKNOWLEGMENT

This work was supported by grants from the National Natural Science Foundation of China, No. 81372119 and National Natural Science Foundation of China, No. 81501134.

Liang D, He X‐B, Wang Z, et al. Remote limb ischemic postconditioning promotes motor function recovery in a rat model of ischemic stroke via the up‐regulation of endogenous tissue kallikrein. CNS Neurosci Ther. 2018;24:519–527. 10.1111/cns.12813

The first two authors contributed equally to this work.

REFERENCES

- 1. Przyklenk K, Bauer B, Ovize M, Kloner RA, Whittaker P. Regional ischemic “preconditioning” protects remote virgin myocardium from subsequent sustained coronary occlusion. Circulation. 1993;87:893‐899. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Ren C, Gao X, Steinberg GK, Zhao H. Limb remote‐preconditioning protects against focal ischemia in rats and contradicts the dogma of therapeutic time windows for preconditioning. Neuroscience. 2008;151:1099‐1103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Pignataro G, Esposito E, Sirabella R, et al. nNOS and p‐ERK involvement in the neuroprotection exerted by remote postconditioning in rats subjected to transient middle cerebral artery occlusion. Neurobiol Dis. 2013;54:105‐114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Costa FL, Teixeira RK, Yamaki VN, et al. Remote ischemic conditioning temporarily improves antioxidant defense. J Surg Res. 2016;200:105‐109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Hahn CD, Manlhiot C, Schmidt MR, Nielsen TT, Redington AN. Remote ischemic per‐conditioning: a novel therapy for acute stroke? Stroke. 2011;42:2960‐2962. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Czigány Z, Turóczi Z, Ónody P, et al. Remote ischemic perconditioning protects the liver from ischemia–reperfusion injury. J Surg Res. 2013;185:605‐613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Meng R, Asmaro K, Meng L, et al. Upper limb ischemic preconditioning prevents recurrent stroke in intracranial arterial stenosis. Neurology. 2012;79:1853‐1861. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Brevoord D, Kranke P, Kuijpers M, Weber N, Hollmann M, Preckel B. Remote ischemic conditioning to protect against ischemia‐reperfusion injury: a systematic review and meta‐analysis, Moretti C, editor. PLoS ONE 2012;7:e42179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Gritsopoulos G, Iliodromitis EK, Zoga A, et al. Remote postconditioning is more potent than classic postconditioning in reducing the infarct size in anesthetized rabbits. Cardiovasc Drugs Ther. 2009;23:193‐198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Burda R, Danielisova V, Gottlieb M, et al. Delayed remote ischemic postconditioning protects against transient cerebral ischemia/reperfusion as well as kainate‐induced injury in rats. Acta Histochem. 2014;116:1062‐1067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Seifi B, Kadkhodaee M, Najafi A, Mahmoudi A. Protection of liver as a remote organ after renal ischemia‐reperfusion injury by renal ischemic postconditioning. Int J Nephrol. 2014;2014:1‐4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Dorsa RC, Pontes JCDV, Antoniolli ACB, et al. Effect of remote ischemic postconditioning inflammatory changes in the lung parenchyma of rats submitted to ischemia and reperfusion. Braz J Cardiovasc Surg 2015;30:353‐359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Khan MB, Hoda MN, Vaibhav K, et al. Remote ischemic postconditioning: harnessing endogenous protection in a murine model of vascular cognitive impairment. Transl Stroke Res. 2015;6:69‐77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Ren C, Yan Z, Wei D, Gao X, Chen X, Zhao H. Limb remote ischemic postconditioning protects against focal ischemia in rats. Brain Res. 2009;1288:88‐94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Bhoola KD, Figueroa CD, Worthy K. Bioregulation of kinins: kallikreins, kininogens, and kininases. Pharmacol Rev. 1992;44:1‐80. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Regoli D, Nsa Allogho S, Rizzi A, Gobeil FJ. Bradykinin receptors and their antagonists. Eur J Pharmacol. 1998;348:1‐10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Xia C‐F, Yin H, Borlongan CV, Chao L, Chao J. Kallikrein gene transfer protects against ischemic stroke by promoting glial cell migration and inhibiting apoptosis. Hypertension. 2004;43:452‐459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Xia C‐F, Yin H, Yao Y‐Y, Borlongan CV, Chao L, Chao J. Kallikrein protects against ischemic stroke by inhibiting apoptosis and inflammation and promoting angiogenesis and neurogenesis. Hum Gene Ther. 2006;17:206‐219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Schoemaker RG, van Heijningen CL. Bradykinin mediates cardiac preconditioning at a distance. Am J Physiol‐Heart Circ Physiol. 2000;278:H1571‐H1576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Zhang B, He Q, Li Y, et al. Constraint‐induced movement therapy promotes motor function recovery and downregulates phosphorylated extracellular regulated protein kinase expression in ischemic brain tissue of rats. Neural Regen Res. 2015;10:2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Jeanneteau J, Hibert P, Martinez MC, et al. Microparticle release in remote ischemic conditioning mechanism. Am J Physiol‐Heart Circ Physiol. 2012;303:H871‐H877. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Wirth K, Hock FJ, Albus U, et al. Hoe 140 a new potent and long acting bradykinin‐antagonist: in vivo studies. Br J Pharmacol. 1991;102:774‐777. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Bagaté K, Grima M, Imbs J‐L, Jong WD, Helwig J‐J, Barthelmebs M. Signal transduction pathways involved in kinin B 2 receptor‐mediated vasodilation in the rat isolated perfused kidney. Br J Pharmacol. 2001;132:1735‐1742. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Doycheva D, Shih G, Chen H, Applegate R, Zhang JH, Tang J. Granulocyte‐colony stimulating factor in combination with stem cell factor confers greater neuroprotection after hypoxic‐ischemic brain damage in the neonatal rats than a solitary treatment. Transl Stroke Res. 2013;4:171‐178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Jiang C, Zuo F, Wang Y, Lu H, Yang Q, Wang J. Progesterone changes VEGF and BDNF expression and promotes neurogenesis after ischemic stroke. Mol Neurobiol. 2017;54:571‐581. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Jasek E, Furgal‐Borzych A, Lis GJ, Litwin JA, Rzepecka‐Wozniak E, Trela F. Microvessel density and area in pituitary microadenomas. Endocr Pathol. 2009;20:221‐226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Schaar KL, Brenneman MM, Savitz SI. Functional assessments in the rodent stroke model. Exp Transl Stroke Med. 2010;2:13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Schallert T. Behavioral tests for preclinical intervention assessment. NeuroRx J Am Soc Exp Neurother. 2006;3:497‐504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Albert‐Weißenberger C, Sirén A‐L, Kleinschnitz C. Ischemic stroke and traumatic brain injury: The role of the kallikrein–kinin system. Prog Neurobiol. 2013;101–102:65‐82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Wang Y‐X, Chen Y, Zhang C‐H, et al. Study on the effect of urinary kallidinogenase after thrombolytic treatment for acute cerebral infarction. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci. 2015;19:1009‐1012. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Nokkari A, Mouhieddine TH, Itani MM, et al. Characterization of the kallikrein‐kinin system post chemical neuronal injury: an in vitro biochemical and neuroproteomics assessment. PLoS ONE. 2015;10:e0128601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Chao J, Shen B, Gao L, Xia C‐F, Bledsoe G, Chao L. Tissue kallikrein in cardiovascular, cerebrovascular and renal diseases and skin wound healing. Brain Res. 2009;1288:88‐94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Yao Y, Sheng Z, Li Y, et al. Tissue kallikrein promotes cardiac neovascularization by enhancing endothelial progenitor cell functional capacity. Hum Gene Ther. 2012;23:859‐870. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]