Summary

Aims

Multiple evidence has indicated that myelin injury is common in Alzheimer's disease (AD). However, whether myelin injury is an early event in AD and the relationship between it and cognitive function is still elusive.

Methods

Spatial memory of 5XFAD mice was determined by Morris water maze at 1 and 3 months old. Meanwhile, the deposition of Aβ, the expression of myelin basic protein (MBP), LINGO‐1, NgR, and myelin ultrastructure in many memory‐associated brain regions were detected in one‐month‐old and three‐month‐old mice (before and after LINGO‐1 antibody administration) using immunostaining, Western blot (WB), and transmission electron microscopy (TEM), respectively.

Results

No abnormal Aβ deposition was found in one‐month‐old 5XFAD mice. However, spatial memory deficits were proved in accordance with an obvious demyelination in memory‐associated brain regions in one‐month‐old mice and both deteriorated with age. Administration of LINGO‐1 antibody could obviously restore the myelin impairments in CA1 and DG region and partially ameliorate spatial memory deficits.

Conclusions

Our results demonstrated that myelin injury was an early event in 5XFAD mice even prior to emergence of deposition of Aβ. Intervention with the LINGO‐1 antibody could attenuate impaired spatial memory deficits by remyelination, which suggested that myelin injury was involved in spatial memory deficits and remyelination may be a potential therapeutic strategy in early stage of AD or mild cognitive impairments.

Keywords: 5XFAD mice, Alzheimer's disease, LINGO‐1 antibody, myelin injury, remyelination, spatial memory

1. INTRODUCTION

There is multilevel evidence indicating myelin impairments in Alzheimer's disease (AD). The number of oligodendrocytes (OLGs) and oligodendrocyte progenitor cells (OPCs), which generate myelin, is reduced significantly in both cortex of APP/PS1 double‐transgenic mice and humans.1 The lipid component of myelin in white matter is reduced,2 with changed lipid profile in AD patients.3, 4 The proteins of myelin in regions of cortex and subcortex including myelin basic protein (MBP), 2′,3′‐cyclic nucleotide 3′‐phosphodiesterase, and proteolipid protein are also decreased significantly.5, 6, 7, 8 The concentrations are found to be higher in cerebrospinal fluid, including ceramide,9 MBP,10 and the antibodies of MBP and myelin oligodendrocyte glycoprotein.11, 12, 13 Furthermore, significant loss of myelin integrity has been shown in patients with AD and mild cognitive impairment (MCI) compared to controls measured by diffusion tensor imaging (DTI),14 and this precedes the onset of cognitive impairment in both healthy aging adults and apolipoprotein E (APOE) ε4 carriers.15, 16, 17 Recently, it was demonstrated that transgenic AD mice, including triple‐transgenic AD mice and APP/PS1 mice, exhibit significant abnormalities in myelination patterns and in the expression profiles of oligodendrocyte markers at subregions of the entorhinal cortex (ERC) and hippocampus.18, 19

Myelin ensures saltatory conduction of action potentials, which makes it possible to integrate information across spatially distributed neural networks underlying higher cognitive function,20 such as memory. Preliminary clinical evidence has suggested that the decline in memory is associated with demyelination of neural circuits at AD onset, which is reflected by increases in radial diffusivity (DR) of DTI, especially in the direct or secondary connections to the medial temporal lobe structures, such as parahippocampal white matter (WM), the cingulum, the inferior fronto‐occipital fasciculus/unciform fasciculus, and the splenium of the corpus callosum.21 However, it was still unknown whether demyelination plays an important role in memory impairment independent of amyloid and tau pathology in AD.

LINGO‐1 is an attractive target for remyelination in central nervous system (CNS). This protein, selectively expressed on neurons 22, 23 and OLGs 24 in CNS,22 interacts with the Nogo‐66 receptor (NgR) and p75/TROY/TOJ neurotrophic receptor 25 as a negative regulator for OLGs differentiation and myelination, neuronal survival and axonal regeneration.22, 24 Previous studies found that LINGO‐1 and its associated proteins were elevated significantly,26 and endogenous inhibitors of NgR1 were decreased in hippocampus of aged rats with impaired memory significantly.27 And some researches have shown that LINGO‐1 antagonists increase the expression and phosphorylation status of Fyn and decrease the amount of activated RhoA‐GTP, thereby promoting differentiation and myelination.24, 28 Based on this evidence, a human monoclonal antibody directed against LINGO‐1 (BIIB033) has been used in subjects with relapsing forms of multiple sclerosis (MS) and acute optic neuritis to enhance CNS remyelination.

In this study, we tested the hypothesis that demyelination might be involved in memorial impairment in 5XFAD mice at early stage of AD. It was shown that myelin injury is an early event in 5XFAD mice prior to emergence of deposition of Aβ and involved in spatial memory deficits, while remyelination with LINGO‐1 antibody could attenuate spatial memory deficits.

2. METHODS

2.1. Transgenic and wild mice

5XFAD mice co‐express human APP and presenilin 1 with five familial AD mutations (APP K670N/M671L + I716V + V717I and PS1 M146L + L286V) were obtained from Jackson Laboratories.29 The 5XFAD mice were backcrossed for five generations on the C57BL6/J genetic background in Fujian Medical College. The mice were genotyped using polymerase chain reaction and gel electrophoresis. Only male mice were used for the follow experiments. The experiments used one‐month‐old and three‐month‐old male 5XFAD mice, along with age‐matched wild‐type C57BL6/J mice. All mice were housed in standard 12‐h light–dark cycle (lights on at 7:00 am) with free access to food and water, maintained in a temperature (22 ± 2°C) and humidity (50 ± 5%) controlled environment. All protocols and procedures used in the study were approved by the Jiang Su Animal Care and Use Committee.

2.2. Generation of the LINGO‐1 antibody

The protocols were applied referring previous report 30 in the process of generation, identification, and biophysical characterization analysis of murine monoclonal antibody (mAb) to LINGO‐1. In brief, the recombinant LINGO‐1 (sequence was shown in Figure 1.) was generated in Escherichia coli and purified on protein A‐Sepharose (GenScript Company, China). The antibody to LINGO‐1 was generated subsequently as the MonoExpress™ Gold package service (GenScript Company). The specificity of antibody was tested for combining with the recombinant LINGO‐1 using Western Blot (WB), another dC‐his‐tagged protein as negative control and serum from the immunized mice with recombinant LINGO‐1 as positive control. The specific binding with recombinant LINGO‐1 and LINGO‐1 in brain and spine was also proved with WB and ELISA in previous studies from our group.31

Figure 1.

The sequence of recombinant LINGO‐1 protein

2.3. Affinity, Pharmacokinetics, and administration of antibody to LINGO‐1 in brain of mouse

The 50% of maximal effect (EC50) of the antibody to LINGO‐1 was detected with ELISA. ELISA plate was coated at 4°C overnight with 10 μg/mL of recombinant LINGO‐1. Moreover, ELISA analysis was performed with 3‐fold serial dilutions of test samples in PBS with 0.1% bovine serum albumin. The EC50 was calculated basing on the value of absorption with Richard's five‐parameter dose‐response curve in GraphPad Prism 6.01 software. The generated antibody was prepared for 3 mg/mL in saline and administered to the eight‐week‐old male C57BL6/J mice at 10 mL/kg via intraperitoneal injection to assess pharmacokinetics in brain. Brains of mice were collected at 0, 6, 24, 72, 144, and 216 hours after administration (3 mice/time point). The natural level of antibodies to LINGO‐1 in brain was also assessed in three mice administered with saline. The level of antibody was measured with ELISA as above in homogenate of brains. Tissue concentration of antibody in test samples was interpolated from appropriate standard curves prepared with the antibody to LINGO‐1 known the concentration and reported as amount/volume assuming the densities of brain tissue is 1.

According to the results of pharmacokinetics in brain of mice (Figure 2D), one‐month‐old 5XFAD mice were administrated LINGO‐1 antibody (5XFAD+anti‐LINGO‐1) every 6 day over 2 months. Dosing solution was prepared in saline at 3 mg/mL and administered to mice at 1 mL/kg via subcutaneous injection. Another group one‐month‐old 5XFAD and wild mice were administrated with saline. Our previous study also revealed that the concentration of the antibody could promote remyelination and recovery of motor and cognitive function in experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis and cuprizone‐fed demyelated mice separately 31, 32

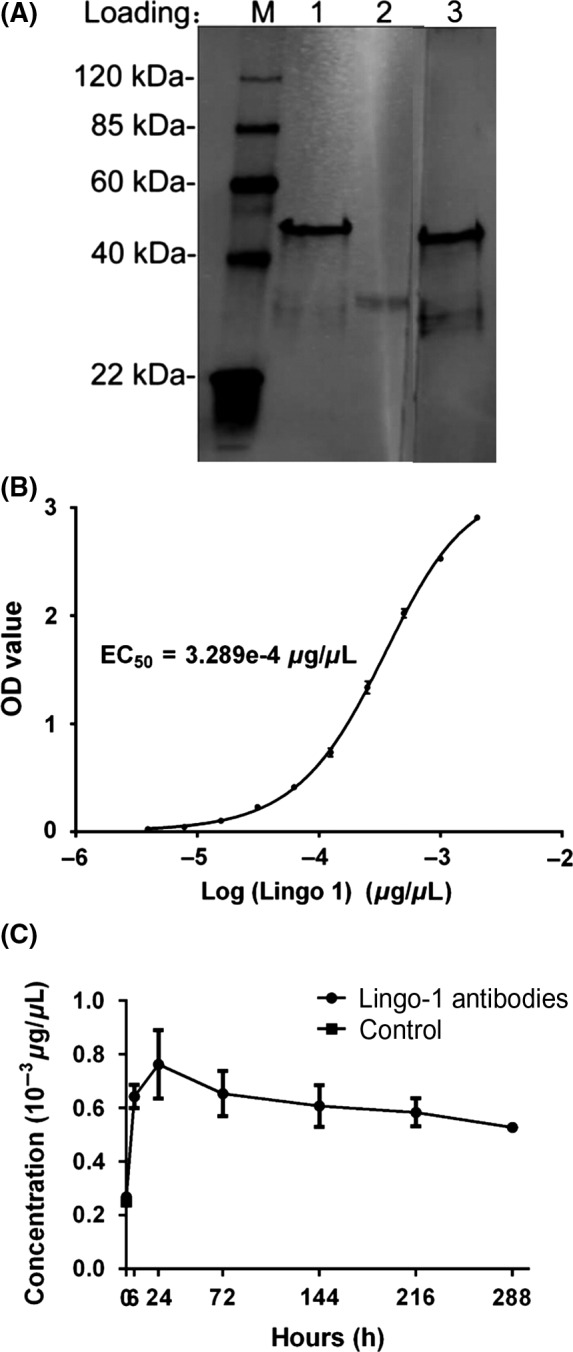

Figure 2.

Anti‐LINGO‐1 monoclonal antibody characterization. A, The monoclonal antibody binds to the recombinant LINGO‐1 protein: Lanes 1 and 3, recombinant LINGO‐1 protein; Lane 2, DC‐tagged fusion protein; Primary antibodies: Lane 1 and 2, LINGO‐1 monoclonal antibody; Lane 3, antiserum of mouse immunized by LINGO‐1 protein. B, Binding curves and EC50 of the antibody to recombinant LINGO‐1 protein was measured by ELISA. C, The pharmacokinetics of the antibody in mice brain (n = 3). Data are presented as mean ± SEM

2.4. Morris water maze test (MWM)

Our MWM has been described elsewhere.31 Briefly, the maze was a 1.2‐m‐diameter circular pool filled with opaque water (22°C) addicted by nontoxic, water‐based white food coloring. A circular Plexiglas escape platform (6 cm in diameter) was located in the center of one quadrant of the pool. The maze is surrounded by blue curtains to obscure prominent room cues, and each quadrant had unique, large geometric figures mounted on them. The platform was mounted 1.5 cm below the surface of the water. Acquisition trials consisted of four trials (20‐30 minutes interval) per day for 5 successive days followed by one additional day for the probe trial. In acquisition trials, mice were started at one of four positions located distal to the quadrant containing the platform in a random order. If an animal failed to find the platform within 60 second, it was picked up and placed on the platform for 30 second. The mice were tested without the platform starting from the opposite quadrant of the platform for 60 second. An automatic tracking system (Mobiledatum Company, China) was used to record swimming speed, time spent in the platform quadrant, and crossovers of the platform position.

2.5. Transmission electron microscopy (TEM)

Mice were processed for TEM analysis as description with slight modifications.1 Brain regions were dissected with a dissecting microscope according to the mouse brain stereotaxic atlas,33 including prelimbic area (PrL) (bregma 2.96 to 1.54 mm), retrosplenial granular cortex (Rsg) (bregma −0.94 to −2.80 mm), ERC (bregma −2.92 to −4.36 mm), and CA1 (bregma −1.46 to −3.08 mm). About ten electron micrographs containing myelin were taken randomly from different field‐of‐view in each ultra‐thin section with TEM (H‐7650, Hitachi High‐Technologies Corporation, Japan), and at least a total number of 150 myelin and axons were analyzed in each brain region. G‐ratio (axon diameter/myelinated fiber diameter) and myelin aberrations per number of axons (%) were counted by two independent persons with the ImageJ software.

2.6. Western Blot (WB)

Tissue samples from different regions of the mice brain were collected, including medial prefrontal cortex (mPFC) (bregma 2.80 to 1.54 mm), caudate putamen (CPu) (bregma 1.70 to −0.82 mm), anterior cingulate (AC) (bregma −1.06 to −2.92 mm), dentate gyrus (DG) (bregma −1.46 to −4.04 mm), hippocampus CA1 (bregma −1.46 to −4.04 mm), retrosplenial cortex (RSC) (bregma −0.94 to −4.16 mm), and entorhinal cortex (ERC) (bregma −2.92 to −5.20 mm). Twenty micrograms of tissue was lysed using 200 ul ice‐cold lysis buffer [20 mmol/L Tris PH7.5, 150 mmol/L NaCl, 1% Triton X‐100, 2.5 mmol/L sodium pyrophosphate, 1 mmol/L EDTA, 1% Na3VO4, 0.5 μg/mL leupeptin, 1 mmol/L phenylmethanesulfonyl fluoride (PMSF)]. WB was performed with primary antibodies against MBP (1:1000, Abcam), LINGO1 (1:1000, Abcam) and NgR (1:500, R&D), and GAPDH (1:5000, sigma) as a loading control. Blots were developed by chemiluminescence (GE Healthcare) and quantified by densitometry. All fractions obtained with antibodies specific to the protein were analyzed.”

2.7. Immunofluorescence

Mice were deeply anesthetized with chloral hydrate and perfused transcardially with saline followed by 4% paraformaldehyde. The animals' brains were removed, postfixed with 4% paraformaldehyde overnight and followed by 10%, 20%, and 30% sucrose solutions, each for at least 16 hours. Brain tissue was embedded in Tissue Freezing Medium (Leica, Germany), frozen at −80 °C and cut with a Leica microtome into 50‐μm coronal sections. Nonspecific binding was blocked with normal nonimmune serum. Slices were stained with rabbit Anti‐Aß 1‐42 monoclonal antibody (ab201060, Abcam) (1:200) overnight at 4°C followed by incubation with a biotinylated secondary antibody. Following the incubation with primary antibodies, sections were washed and incubated for 2 hours at room temperature with secondary antibody goat Alexa Fluor 594 F(ab) anti‐rabbit IgG (1:200). Images were captured with a fluorescence microscope equipped with 10 × objectives.

2.8. Statistical analysis

All values were presented as the means ± standard error (S.E.M). Data from acquisition trials of MWM was analyzed with two‐way repeated‐measures analysis of variance (ANOVA) with two factors, groups (Wild, 5XFAD, and 5XFAD with LINGO‐1 antibody) and time (day 1 to day 5) followed by Sidak's multiple comparisons test (GraphPad Prism 6.07). The crossovers of position were adjusted with swimming speed and analyzed with univariate general linear model (SPSS 22.0). The average percentage of time spent in target quadrant was analyzed by individual one‐way (Quadrants) repeated ANOVA and Holm‐Sidak's post hoc comparison tests (GraphPad Prism 6.07). In other parts, Student's t‐test was used between two groups, and one‐way ANOVA was used among three groups followed by Holm‐Sidak's multiple comparisons as post hoc test (GraphPad Prism 6.07). Correlation analysis was conducted with Pearson's correlation (GraphPad Prism 6.07). Statistical significance was established at P < 0.05.

3. RESULTS

3.1. The characterization of LINGO‐1 monoclonal antibody

As shown in Figure 2A, the monoclonal antibody could bind recombined LINGO‐1 protein specially. It was purified to 93% and efficiently reduced endotoxin levels to ≤3 EU/mg. Binding curves and concentration for EC50 are shown in Figure 2C. The pharmacokinetics in brain of mouse were shown in Figure 2D. The lowest concentration of the antibody was much higher than EC50 (3.289e‐4 μg/μL), and 144 h was chosen as the interval of administration.

3.2. Deposition of Aß in three‐month‐old 5XFAD mice

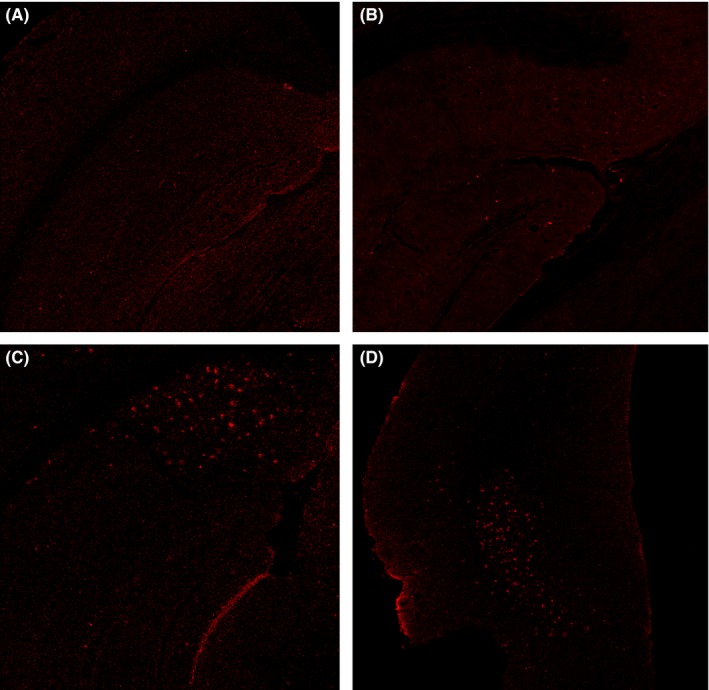

The deposition of Aß was not found in one‐month‐old 5XFAD mice, but shown in three‐month‐old 5XFAD mice in both hippocampus and entorhinal cortex (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Amyloid load using Aß 1‐42 stains in wild and 5XFAD mice at different ages. A,B, No obvious amyloid deposition was observed in hippocampus in one‐month‐old 5XFAD mice and three‐month‐old wild mice. C,D, Amyloid deposition was detected in hippocampus and entorhinal cortex of 5XFAD mice at 3 mo old. Original magnification: 40 ×

3.3. Impairments of memory in one‐month‐old 5XFAD mice and improvement at three‐month‐old administrated with LINGO‐1 antibody

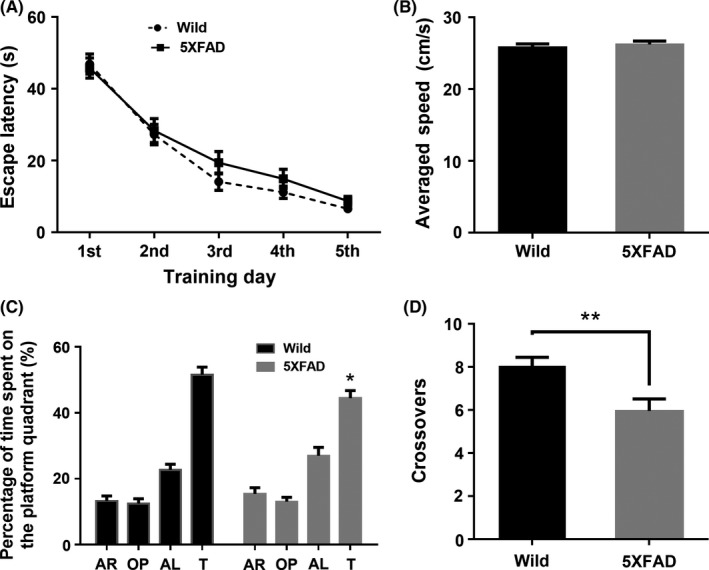

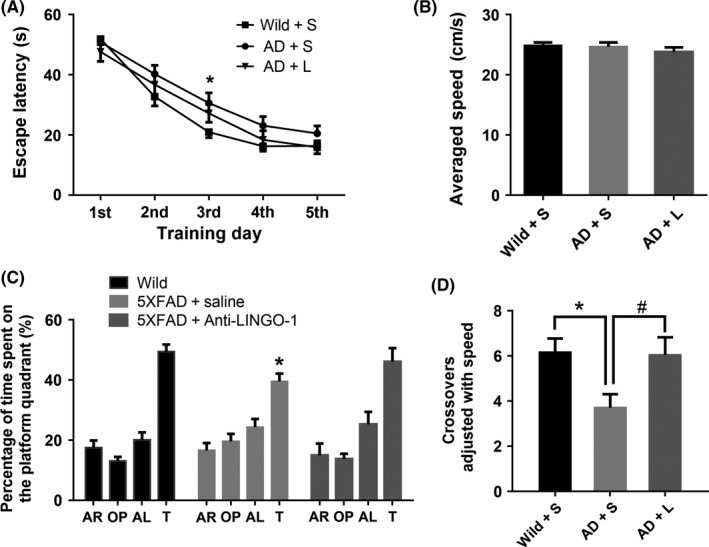

In the MWM test, one‐month‐old 5XFAD mice showed a significant decrease in the percentage of the time spent on the quadrant (t = 2.790, P = 0.005, Figure 4C) and the crossovers of platform (t = 3.000, P = 0.004, Figure 4D) compared with controls, whereas no significant difference in swimming velocity (Figure 4B). In addition, there was no significant difference in the escape latency in the five training days (Figure 4A). Compared with controls group, three‐month‐old 5XFAD mice significantly prolonged the escape latency to find the hidden platform at the third day (t = 2.823, P = 0.016), while it tended to improve with anti‐LINGO‐1 treatment (Figure 5A). In the probe trial of MWM test, there was distinct difference in the percentage of the time spent on the quadrant (F = 3.426, P = 0.041, Figure 5C) and the crossovers of platform (F = 4.801, P = 0.013, Figure 5D). Three‐month‐old 5XFAD mice significantly decreased the percentage of the time spent on the quadrant (P = 0.046, Figure 5C) and the crossovers of platform (P < 0.001, Figure 5D) without abnormal swimming velocity (Figure 5B) compared with age‐matched controls. While anti‐LINGO‐1 treatment for 5XFAD mice had a significant ameliorative effect on crossovers (t = 9.4, P < 0.001, Figure 5D) and ameliorative trend in the time spent on the quadrant (Figure 5C).

Figure 4.

The Morris water maze test of one‐month‐old mice. A,B, In the training session, there were no statistical significances observed in the escape latency and swimming speed in probe trail between groups. C,D, In probe trail, wild‐type mice spent more time in training quadrant compared to the other quadrants. [F = 79.14, P < 0.005, Holm‐Sidak's multiple comparisons test: target > all other quadrants, P < 0.005] Similarly, 5XFAD mice spent more time in training quadrant. [F = 36.19, P < 0.005, Holm‐Sidak's multiple comparisons test: target > all quadrants, P < 0.005]. However, 5XFAD mice spent less time in the quadrant and got less crossovers of platform position (n = 22/group). * P < 0.05, **,P < 0.005

Figure 5.

The Morris water maze test of three‐month‐old mice. A, In training session, 5XFAD mice significantly prolonged the escape latency to find the hidden platform, [F = 2.303, P = 0.020, Holm‐Sidak's multiple comparisons test for group effect: 5XFAD < Wild, P = 0.017] especially at day 3rd. [Holm‐Sidak's multiple comparisons test: 5XFAD < Wild, P = 0.014]. B, There was no statistical significance observed in the swimming speed in probe trail among groups. C, In probe trail, wild‐type mice spent more time in training quadrant compared to the other quadrants. [F = 41.64, P < 0.005, Holm‐Sidak's multiple comparisons test: target > all other quadrants, P < 0.005] 5XFAD mice spent more time in training quadrant. [F = 11.89, P < 0.005, Holm‐Sidak's multiple comparisons test: target > all quadrants, P < 0.005]. 5XFAD + anti‐LINGO‐1mice spent more time in training quadrant. [F = 11.89, P < 0.005, Holm‐Sidak's multiple comparisons test: target > AR, OP quadrants, P < 0.005, AL quadrants, P = 0.040]. However, 5XFAD mice had decreased percentage of the time spent on the quadrant and the crossovers of platform compared with wild mice, D, while LINGO‐1 antibody could recover the crossovers of platform. (n = 18 for wild + saline mice group, n = 18 for 5XFAD + saline mice group, n = 11 for 5XFAD + anti‐LINGO‐1 mice group). *, #, P < 0.05

3.4. Impairments of myelin in one‐month‐old 5XFAD mice and remyelination at three‐month‐old administrated with LINGO‐1 antibody

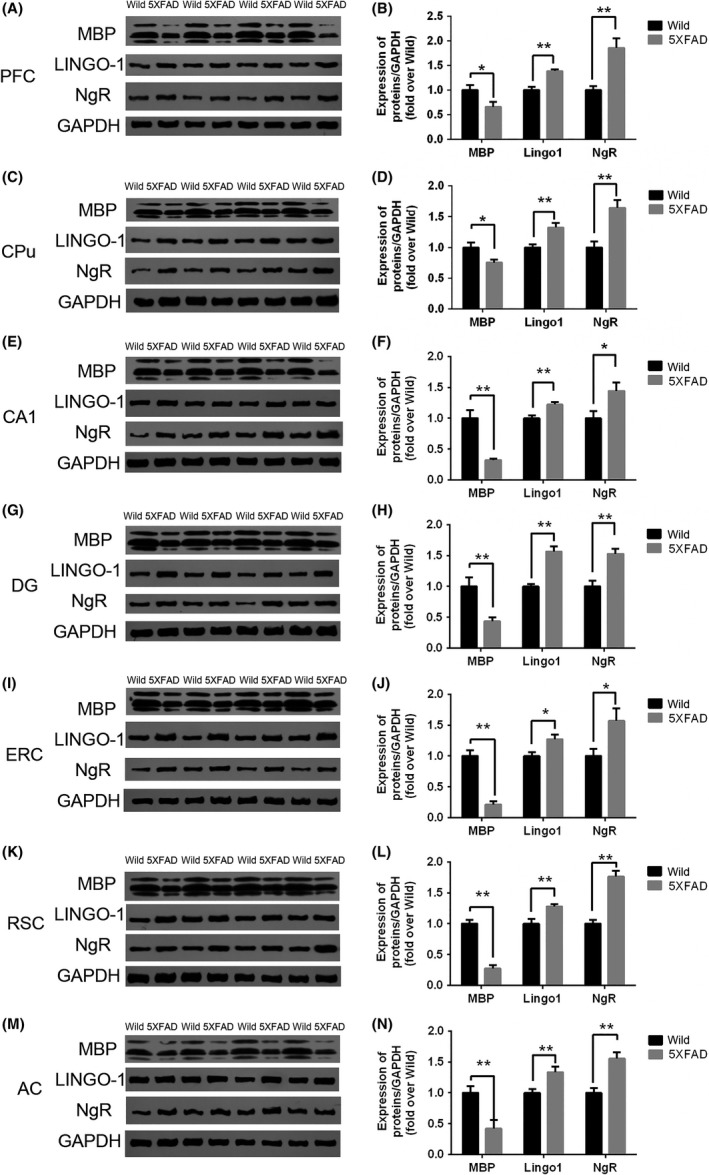

A significant decrease in MBP expression was observed in all detected brain regions (memory‐associated brain regions) in one‐month‐old 5XFAD mice (Figure 6. While significant increases in LINGO‐1 and NgR expression were observed in one‐month‐old 5XFAD mice (Figure 6). At the end of the treatment lasting 2 months, one‐way ANOVA revealed a significant difference in MBP expression of three different groups of mice (Figure 7). Holm‐Sidak's multiple comparisons test showed decrease of MBP in 5XFAD mice, which could be partly reversed by anti‐LINGO‐1 intervention, especially in DG and AC. However, LINGO‐1 was decreased only in DG and CPu after treatment with the LINGO‐1 antibody.

Figure 6.

The expression of MBP, LINGO‐1 and NgR in different brain regions of 1‐month‐old mice. MBP was reduced significantly, while LINGO‐1 and NgR were increased significantly in the selective brain regions of one‐month‐old 5XFAD mice (A‐N). (n = 8/group). *, P < 0.05, **, P < 0.005

Figure 7.

The expression of MBP and LINGO‐1 in different brain regions of three‐month‐old mice Significant decrease in MBP expression was observed in different brain regions, respectively, of 5XFAD mice compared with the wild type. Meanwhile, anti‐LINGO‐1 treatment in 5XFAD mice increased the expression of MBP, especially in DG (G, H) and AC (M, N) in 5XFAD mice. But, it was shown that no significantly improved MBP expression in PFC (A, B), CPu (C, D), CA1 (E, F), ERC (I, J) and RSC (K, L). There was an observable increase in the LINGO‐1 expression level in CPu (C, D) and DG (G, H) in 5XFAD mice compared with the controls. Anti‐LINGO‐1 treatment in 5XFAD mice reverses the increase in DG (G, H). (n = 6/group). *, #, P < 0.05, **, ##, P < 0.005

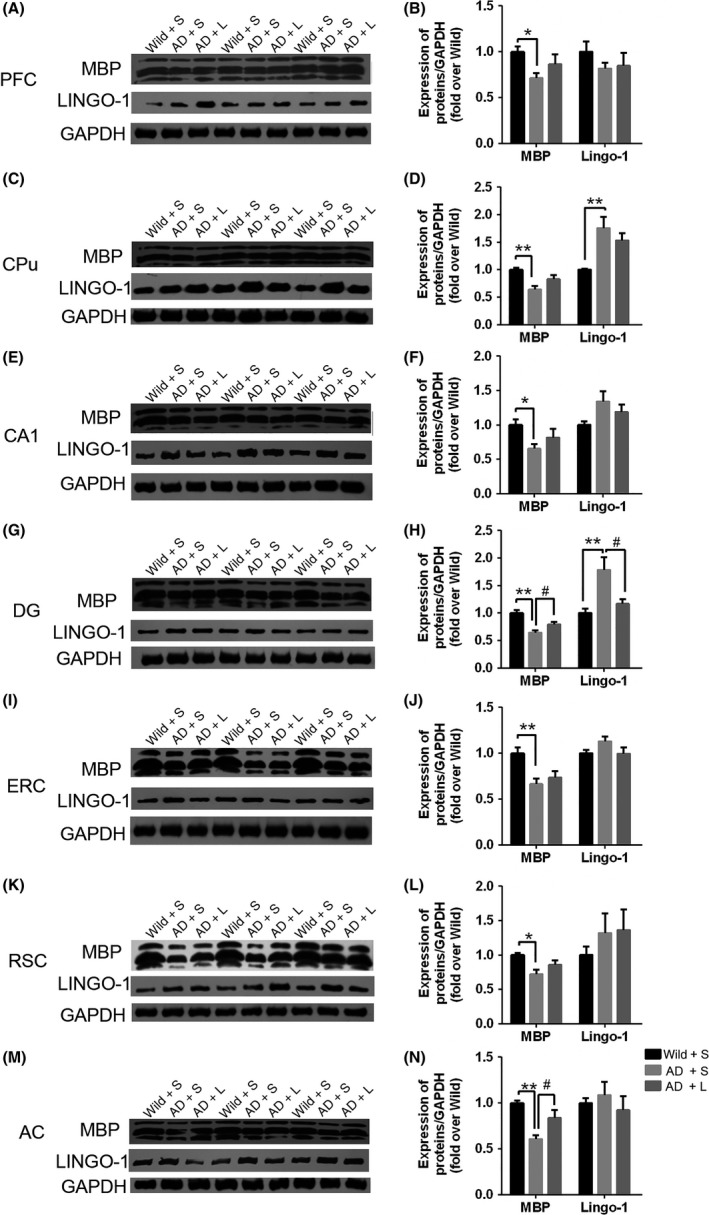

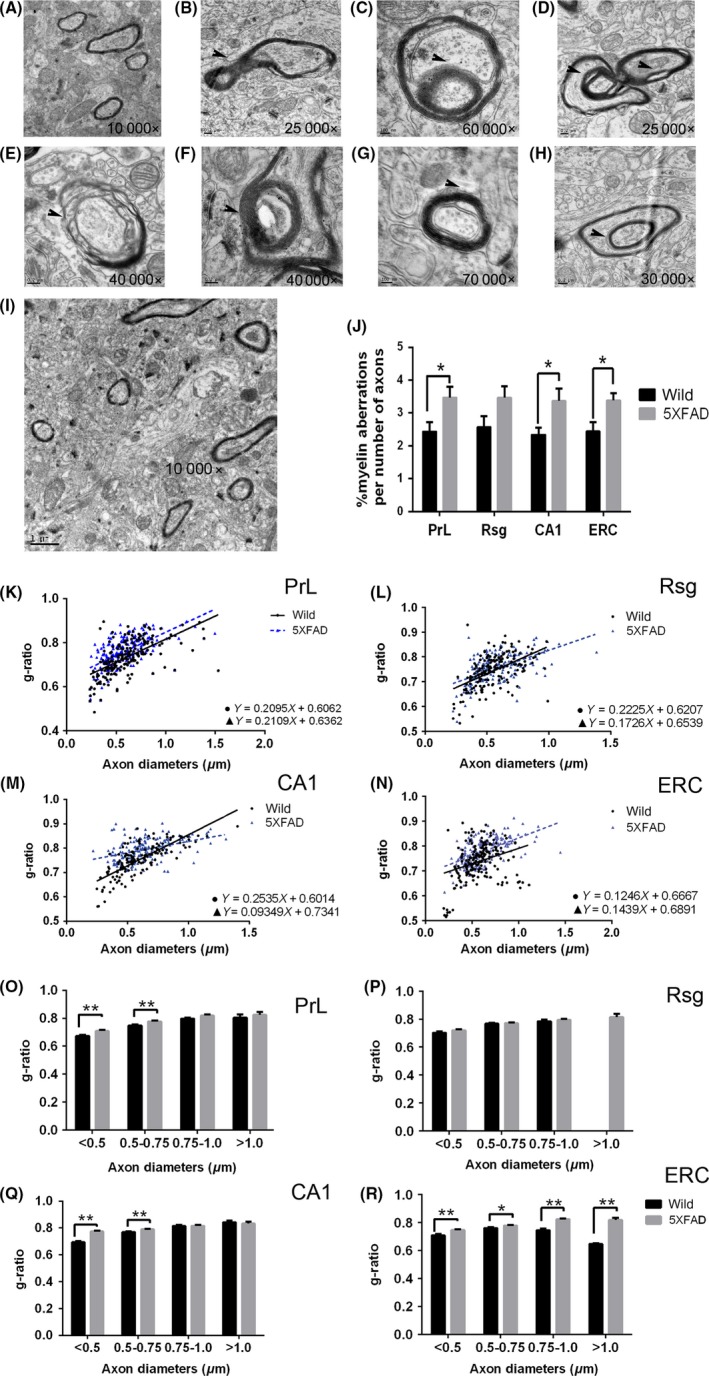

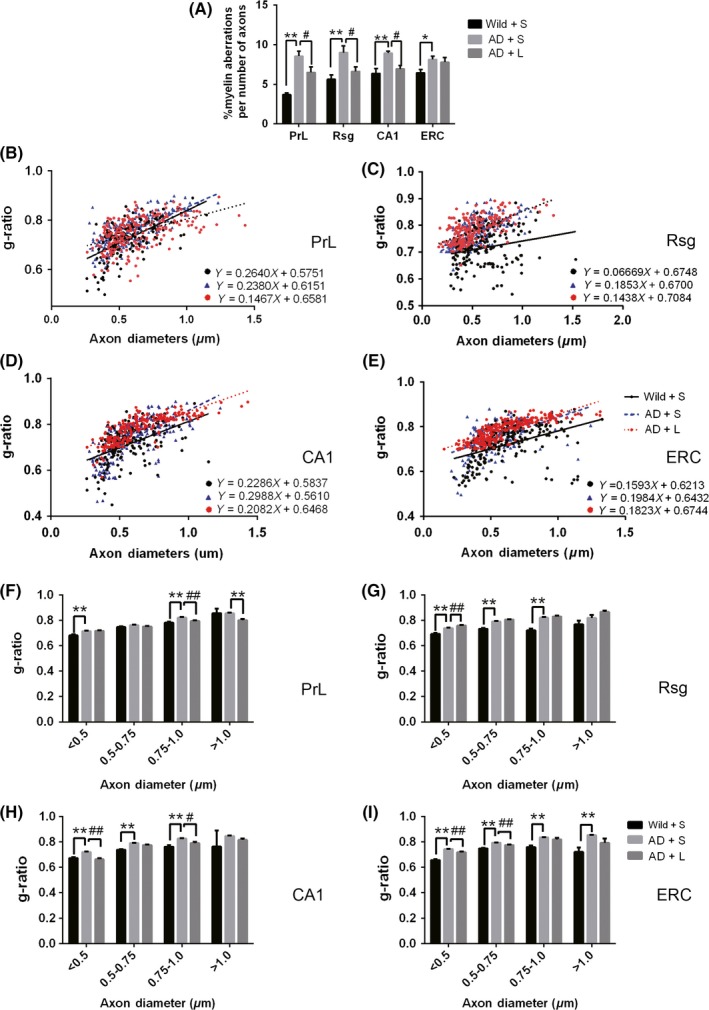

The percentage of aberrant myelinated axons was increased significantly in the regions of cognitive circuit including the PrL (t = 2.423, P = 0.0262), CA1 (t = 2.394, P = 0.0277) and ERC (t = 2.686, P = 0.0151) in one‐month‐old 5XFAD mice compared with controls. Meanwhile, the g‐ratio was also increased in PrL, CA1, and ERC (Figure 8). After anti‐LINGO‐1 treatment, one‐way ANOVA analysis showed the difference in the percentage of aberrant myelinated axons of three different groups and g‐ratio (Figure 9). LINGO‐1 antibody could increase g‐ratio and reduce aberrant myelinated axons.

Figure 8.

The change of ultrastructure in one‐month old 5XFAD mice with TEM. A‐H, The abnormal myelin ultrastructure was shown. I, The TEM image of CA1 of wild type at 1 mo old. J, The percentage of aberrant myelinated axons were increased significantly in PrL, CA1, and ERC. K‐N, Scatter plot of g‐ratio values in wild and 5XFAD mice in four regions. O‐R, The g‐ratio increased in PrL, CA1, and ERC. Scatter plot of g‐ratio values in wild and 5XFAD mice in four regions (D). (n = 2/group). *, P < 0.05, **, P < 0.005

Figure 9.

The change of ultrastructure in three‐month old 5XFAD mice with TEM. A, The percentage of aberrant myelinated axons was increased in PrL, Rsg, CA1, and ERC in 5XFAD mice compared with the controls, and anti‐LINGO‐1 treatment in 5XFAD mice decreased the percentage in PrL, Rsg, and CA1 compared with the 5XFAD mice. B‐E, Scatter plot of g‐ratio values in wild mice with saline administration and 5XFAD mice with saline and LINGO‐1 antibody in four regions. F‐I, G‐ratio was increased in PrL, Rsg, CA1, and ERC in 5XFAD mice compared with the control, and anti‐LINGO‐1 treatment in 5XFAD mice partly decreased the g‐ratio in PrL, Rsg, CA1, and ERC compared with the 5XFAD mice with saline administration. (n = 2/group). *, #, P < 0.05, **, ##, P < 0.005

3.5. The potential relationship of MBP/LINGO‐1 and memory

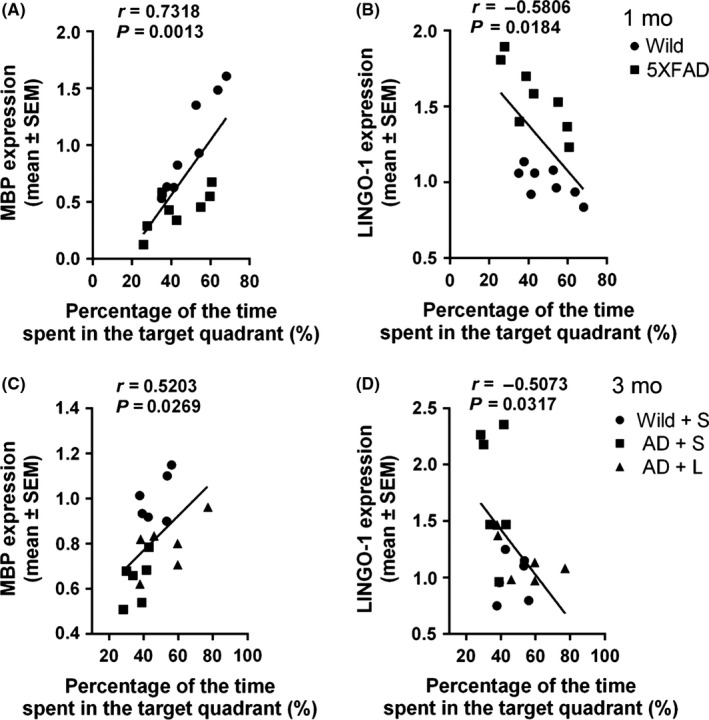

There was positive correlation between increased DG LINGO‐1 expression, decreased MBP expression, and deficits of spatial memory (Figure 10).

Figure 10.

Correlation between the level of MBP or LINGO‐1 in DG and memory behavior in MWM in 5XFAD mice at different ages. A, B, Correlation between MBP or LINGO‐1 and the percentage of time spent in the target quadrant in the probe trial in wild and 5XFAD mice at 1 mo old. C, D, Correlation between MBP or LINGO‐1 and the percentage of time spent in the target quadrant in the probe trial in wild and 5XFAD mice wild mice with saline administration and 5XFAD mice with saline and LINGO‐1 antibody at 3 mo old

4. DISCUSSION

The present study has demonstrated demyelination in an animal model of early AD. Furthermore, spatial memory was found to be impaired in 5XFAD mice at 1 month old and deteriorated with age, which was correlated with demyelination. We also find that administration of an antibody against LINGO‐1 could reverse the impairments of myelin in some brain regions involved in memory and improve memory function of 5XFAD mice. Our results suggested that myelin injury was involved in spatial memory deficits and remyelination may be a potential therapeutic strategy in early stage of AD.

5XFAD mice rapidly recapitulate major features of AD amyloid pathology. Aβ42 was found to increase to 9‐21 ng/mg protein by 2 months old from 0.3 to 0.7 ng/mg protein at 1.5 months old, and the earliest amyloid deposition started at 2 months.29 We also found there was no amyloid pathology at 1 month old in 5XFAD mice. In addition, the concentrations of synaptophysin in the whole brain decrease from 4 months 29 and Ser396 tau phosphorylation is significantly higher than wild‐type mice at age ranging from 2 to 6 months in 5XFAD mice.34 However, we found that spatial memory retrieval is impaired in one‐month‐old mice prior to the emergence of classical pathological markers for AD (amyloid deposition, tau pathologies, and degeneration of synapses). Impairment of learning ability in acquisition trials emerged from 3 months of age, which was later than memorial impairments. There were no motor disabilities for explaining the behavioral abnormalities.

It was shown that abnormalities of myelin occur in different AD mouse models in early stage. These include partially or completely lost myelin sheath within the WM in PDAPP mice at 2 months of age 35 and myelination defects within subregions of the ERC and hippocampus in two‐month‐old 3 × Tg‐AD mice.18 And in clinical study with diffusion tensor imaging, it was also shown that abnormal integrity of myelin concentrated on genu of the corpus callosum, the medial temporal lobe, and their connections in APOEε4 carriers without symptoms,15, 17, 36 Consistent with previous studies, we found the increased abnormal myelinated axons, rising g‐ratio, and decreased MBP in 5XFAD mice at 1 month of age in our study, which is prior to the emergence of classical pathological markers for AD. Combining with previous studies, our results firmly suggested that myelin injury was an early event in AD.

Oligodendroglial LINGO‐1 which regulates developmental myelination, strongly limits OLG differentiation in the process of remyelination, via mechanisms yet to be defined.37 Previous studies have shown that elevated level of LINGO‐1 was found in focal demyelinated regions of MS,24, 38 acute spinal cord injuries,22, 39 and in hippocampus of cognitively impaired aged rats.26 Parallel to the impairments of myelin, we also found LINGO‐1 elevated in some brain regions detected in 5FAD mice at one‐month old age, indicates that LINGO‐1 may be involved in demyelination in early stage of AD, especially in brain regions involved in memorial function. In addition, NgR, the component of LINGO‐1 complex, is elevated in detected regions in our study.

Many studies have demonstrated that myelination is involved in cognition formation. Diffusion tensor imaging shows that abnormal integrity of myelin concentrated on regions of limbic system, prefrontal lobe, and their connections were involved and aggravated in patients with cognitive impairments.40 Our previous study also revealed that demyelination of the parahippocampal cortex (PHC) and fimbria‐fornix may contribute to the cognitive impairment in experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis mice, and the LINGO‐1 antibody ameliorates the spatial memory deficits by promoting remyelination in the PHC.31 In the present study, we found myelin injury in one‐month‐old 5XFAD mice, and the loss of MBP and increase of LINGO‐1 correlated with spatial memory ability, which is consisted with earlier report.26 Furthermore, the administration of LINGO‐1 antibodies could promote remyelination, especially increased MBP in DG and AC, and different levels improvement of myelin structure in many memory‐associated brain regions in accordance with improvement of spatial memory. It was suggested that myelin injury at early stage of AD is involved in spatial memory deficits. However, it was noteworthy that the elevation of LINGO‐1 observed in all brain regions in one‐month‐old mice was not maintained at 3 months, indicating that anti‐LINGO‐1 treatment may not sustain the initial improvement in myelination in the progression of AD. Along with the elevation in LINGO‐1 in cognitively impaired aged rats,26 our results suggest that intervention with the LINGO‐1 antibody would maintain or even restore impaired memorial function partly in 5XFAD mice in the early stage, but may become less efficient with progression of disease.

In conclusion, demyelination was observed prior to emergence of classical AD neuropathology and was related to spatial memory impairment. Intervention with the LINGO‐1 antibody can partly restore impaired regions of memorial function by remyelination, but may become less efficient with disease progression. There are several limitations in the present study. In particular, 5XFAD mice recapitulate AD pathologies during development, while AD is an age‐related illness. In addition, the research did not examine long‐term changes associated with LINGO‐1 antibody administration and the role of remyelination combined with other therapeutic strategies promoting remyelination in disease progression. Furthermore, the different markers for structure and function of synapse were not detected quantitatively; such abnormalities have been reported in early stages of AD, while the change of tau hyperphosphorylation was not measured in this study. Therefore, further comprehensive studies are needed to estimate the role of demyelination at AD onset and to assess intervention aimed at reversing the demyelination.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported in part by grants from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (81420108012 Zhi‐Jun Zhang), the National Major Science and Technology Program of China (No. 2012ZX09506‐001‐009 Zhi‐Jun Zhang), the Key Program for Clinical Medicine and Science and Technology, Jiangsu Provincial Clinical Medical Research Center (BL2013025), the National Key Projects for Research and Development of MOST (2016YFC1305800, 2016YFC1305801 to JZW).

Wu D, Tang X, Gu L‐H, et al. LINGO‐1 antibody ameliorates myelin impairment and spatial memory deficits in the early stage of 5XFAD mice. CNS Neurosci Ther. 2018;24:381–393. 10.1111/cns.12809

The first two authors contributed equally to this work.

Contributor Information

Qing‐Guo Ren, Email: renqingguo1976@163.com.

Zhi‐Jun Zhang, Email: janemengzhang@vip.163.com.

REFERENCES

- 1. Behrendt G, Baer K, Buffo A, et al. Dynamic changes in myelin aberrations and oligodendrocyte generation in chronic amyloidosis in mice and men. Glia. 2013;61:273‐286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Chia LS, Thompson JE, Moscarello MA. X‐ray diffraction evidence for myelin disorder in brain from humans with Alzheimer's disease. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1984;775:308‐312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Wallin A, Gottfries CG, Karlsson I, et al. Decreased myelin lipids in Alzheimer's disease and vascular dementia. Acta Neurol Scand. 1989;80:319‐323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Svennerholm L, Gottfries C‐G, Karlsson I. Neurochemical changes in white matter of patients with Alzheimer's disease. A Multidiscip Approach to Myelin Dis. 1987;142:319‐328. [Google Scholar]

- 5. Reinikainen KJ, Pitkanen A, Riekkinen PJ. 2′,3′‐cyclic nucleotide‐3′‐phosphodiesterase activity as an index of myelin in the post‐mortem brains of patients with Alzheimer's disease. Neurosci Lett. 1989;106:229‐232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Silva PN, Furuya TK, Sampaio Braga I, et al. CNP and DPYSL2 mRNA expression and promoter methylation levels in brain of Alzheimer's disease patients. J Alzheimers Dis. 2013;33:349‐355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Vlkolinsky R, Cairns N, Fountoulakis M, et al. Decreased brain levels of 2′,3′‐cyclic nucleotide‐3′‐phosphodiesterase in Down syndrome and Alzheimer's disease. Neurobiol Aging. 2001;22:547‐553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Roher AE, Weiss N, Kokjohn TA, et al. Increased A beta peptides and reduced cholesterol and myelin proteins characterize white matter degeneration in Alzheimer's disease. Biochemistry. 2002;41:11080‐11090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Satoi H, Tomimoto H, Ohtani R, et al. Astroglial expression of ceramide in Alzheimer's disease brains: a role during neuronal apoptosis. Neuroscience. 2005;130:657‐666. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Noppe M, Crols R, Andries D, et al. Determination in human cerebrospinal fluid of glial fibrillary acidic protein, S‐100 and myelin basic protein as indices of non‐specific or specific central nervous tissue pathology. Clin Chim Acta. 1986;155:143‐150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Maetzler W, Berg D, Synofzik M, et al. Autoantibodies against amyloid and glial‐derived antigens are increased in serum and cerebrospinal fluid of Lewy body‐associated dementias. J Alzheimers Dis. 2011;26:171‐179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Bjerke M, Zetterberg H, Edman A, et al. Cerebrospinal fluid matrix metalloproteinases and tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinases in combination with subcortical and cortical biomarkers in vascular dementia and Alzheimer's disease. J Alzheimers Dis. 2011;27:665‐676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Singh VK, Yang YY, Singh EA. Immunoblot detection of antibodies to myelin basic protein in Alzheimer's disease patients. Neurosci Lett. 1992;147:25‐28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Lee DY, Fletcher E, Martinez O, et al. Regional pattern of white matter microstructural changes in normal aging, MCI, and AD. Neurology. 2009;73:1722‐1728. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Nierenberg J, Pomara N, Hoptman MJ, et al. Abnormal white matter integrity in healthy apolipoprotein E epsilon4 carriers. NeuroReport. 2005;16:1369‐1372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Bartzokis G, Lu PH, Geschwind DH, et al. Apolipoprotein E genotype and age‐related myelin breakdown in healthy individuals: implications for cognitive decline and dementia. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2006;63:63‐72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Bendlin BB, Ries ML, Canu E, et al. White matter is altered with parental family history of Alzheimer's disease. Alzheimers Dement. 2010;6:394‐403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Desai MK, Sudol KL, Janelsins MC, et al. Triple‐transgenic Alzheimer's disease mice exhibit region‐specific abnormalities in brain myelination patterns prior to appearance of amyloid and tau pathology. Glia. 2009;57:54‐65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Mitew S, Kirkcaldie MTK, Halliday GM, et al. Focal demyelination in Alzheimer's disease and transgenic mouse models. Acta Neuropathol. 2010;119:567‐577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Blasko I, Humpel C, Grubeck‐Loebenstein B. Glial Cells: astrocytes and Oligodendrocytes during Normal Brain Aging In: Squire LR, ed. Encycl. Neurosci. Oxford, UK: Academic Press; 2009:743‐747. [Google Scholar]

- 21. Gold BT, Johnson NF, Powell DK, et al. White matter integrity and vulnerability to Alzheimer's disease: preliminary findings and future directions. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2012;1822:416‐422. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Mi S, Lee X, Shao Z, et al. LINGO‐1 is a component of the Nogo‐66 receptor/p75 signaling complex. Nat Neurosci. 2004;7:221‐228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Lööv C, Fernqvist M, Walmsley A, et al. Neutralization of LINGO‐1 during in vitro differentiation of neural stem cells results in proliferation of immature neurons. PLoS ONE. 2012;7:e29771. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Mi S, Miller RH, Lee X, et al. LINGO‐1 negatively regulates myelination by oligodendrocytes. Nat Neurosci. 2005;8:745‐751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Mosyak L, Wood A, Dwyer B, et al. The structure of the Lingo‐1 ectodomain, a module implicated in central nervous system repair inhibition. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:36378‐36390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. VanGuilder Starkey HD, Sonntag WE, Freeman WM. Increased hippocampal NgR1 signaling machinery in aged rats with deficits of spatial cognition. Eur J Neurosci. 2013;37:1643‐1658. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Starkey HDVG, Bixler GV, Sonntag WE, et al. Expression of NgR1‐antagonizing proteins decreases with aging and cognitive decline in rat hippocampus. Cell Mol Neurobiol. 2013;33:483‐488. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Ji B, Li M, Wu W‐T, et al. LINGO‐1 antagonist promotes functional recovery and axonal sprouting after spinal cord injury. Mol Cell Neurosci. 2006;33:311‐320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Oakley H, Cole SL, Logan S, et al. Intraneuronal beta‐amyloid aggregates, neurodegeneration, and neuron loss in transgenic mice with five familial Alzheimer's disease mutations: potential factors in amyloid plaque formation. J Neurosci. 2006;26:10129‐10140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Mi S, Hu B, Hahm K, et al. LINGO‐1 antagonist promotes spinal cord remyelination and axonal integrity in MOG‐induced experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis. Nat Med. 2007;13:1228‐1233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Sun J‐J, Ren Q‐G, Xu L, et al. LINGO‐1 antibody ameliorates myelin impairment and spatial memory deficits in experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis mice. Sci Rep. 2015;5:14235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Sun J, Zhou H, Bai F, et al. Myelin injury induces axonal transport impairment but not AD‐like pathology in the hippocampus of cuprizone‐fed mice. Oncotarget. 2016;7:30003‐30017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Paxinos G, Franklin KBJ. The Mouse Brain in Stereotaxic Coordinates. Houston, TX: Gulf Professional Publishing; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 34. Kanno T, Tsuchiya A, Nishizaki T. Hyperphosphorylation of Tau at Ser396 occurs in the much earlier stage than appearance of learning and memory disorders in 5XFAD mice. Behav Brain Res. 2014;274C:302‐306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Song S‐K, Kim JH, Lin S‐J, et al. Diffusion tensor imaging detects age‐dependent white matter changes in a transgenic mouse model with amyloid deposition. Neurobiol Dis. 2004;15:640‐647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Gold BT, Powell DK, Andersen AH, et al. Alterations in multiple measures of white matter integrity in normal women at high risk for Alzheimer's disease. NeuroImage. 2010;52:1487‐1494. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Bhatt A, Fan LW, Pang Y. Strategies for myelin regeneration: lessons learned from development. Neural Regen Res. 2014;9:1347‐1350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Mi S, Miller RH, Tang W, et al. Promotion of central nervous system remyelination by induced differentiation of oligodendrocyte precursor cells. Ann Neurol. 2009;65:304‐315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Erschbamer MK, Hofstetter CP, Olson L. RhoA, RhoB, RhoC, Rac1, Cdc42, and Tc10 mRNA levels in spinal cord, sensory ganglia, and corticospinal tract neurons and long‐lasting specific changes following spinal cord injury. J Comp Neurol. 2005;484:224‐233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Radanovic M, Pereira FRS, Stella F, et al. White matter abnormalities associated with Alzheimer's disease and mild cognitive impairment: a critical review of MRI studies. Expert Rev Neurother. 2013;13:483‐493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]