For much of the 20th century, cardiovascular disease (CVD) was considered a disorder of men despite its being a major cause of mortality among women. In the emerging era of evidence‐based medicine, CVD in women was treated based on studies conducted exclusively or predominantly in middle‐aged Caucasian men. Not surprisingly, advances in the recognition and management of cardiovascular illness resulted in decreased mortality for men, but not for their female peers.

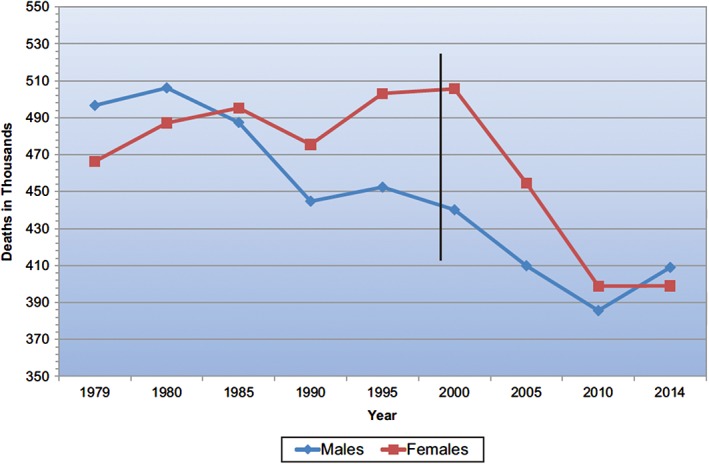

Sex‐ and gender‐based cardiovascular medicine have been advanced by the participation of women in clinical research studies. The emphasis on sex and gender differences in the prevention, recognition, and management of cardiovascular illness, coupled with efforts by major national groups, in particular the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute and the American Heart Association, created awareness that the female heart is vulnerable to cardiovascular illness.1 The results have been stunning. Since 2000, there has been a sharp decline in cardiovascular mortality among women, and for the first time in 2012 to 2013, fewer US women than men died annually from cardiovascular illness, with this pattern continuing the following year (Figure 1).2 In the early years of data collection, 1 out of 2 US women died of CVD, subsequently deceasing to 1 out of 3 women; current data identified that 1 out of 4 female deaths in the United States is due to CVD.3

Figure 1.

Cardiovascular disease mortality trends for males and females (United States: 1979–2013). Cardiovascular disease excludes congenital cardiovascular defects (International Classification of Diseases, 10th Revision codes I00–I99). Source: Benjamin et al.2

We have learned that conventional coronary risk factors impact women differently (and generally more adversely) than their male peers and have identified a sizeable number of risk attributes unique to or predominant in women.4 Heart disease related to pregnancy and to systemic autoimmune illness has come to the forefront. Although women share with men the problem of atherosclerotic obstructive disease of the epicardial coronary arteries, myocardial ischemia in women is far more complex, encompassing sizeable contributions of nonobstructive coronary atherosclerosis and microvascular disease. Gender‐specific approaches to diagnostic testing for suspected ischemic heart disease have been published.5 Relatively uncommon but life‐threatening illnesses that predominate in women, such as spontaneous coronary artery dissection and Takotsubo cardiomyopathy, are being investigated to pursue optimal approaches to care. Gender differences in arrhythmias have been identified, with the highlighting of atrial fibrillation as a prominent problem for elderly women, one that is under‐recognized and suboptimally managed. The differential use of electrophysiologic devices by gender has been highlighted, as has the limited data available for women. Heart failure with preserved ejection fraction, a problem that predominates in older women, has yet to receive evidence‐based therapy.

Obviously, the journey has just begun. Almost half of US women are unaware that CVD is their number 1 health problem, with the lack of awareness predominating among women of racial and ethnic minorities.6 Women remain under‐represented in cardiovascular clinical trials, and we look forward to the salutary effects of the Heart Research for All Act of 2015 in remedying this problem.7

The editors recognize with appreciation the authors of the articles in this issue of Clinical Cardiology, highlighting important areas that impact the cardiovascular health of women. The knowledge gaps cited that require elucidation will provide a research agenda for the decade to come. Importantly, we need to be advocates for women's health and policy, and our authors address this in this special issue. Additionally, the importance of attracting and retaining women in the cardiology work force is paramount to continuing the focus on women's cardiovascular health, but also creating a diverse work force that will benefit both men and women, and improve the health of our nation.

The editors acknowledge with admiration and appreciation the peer reviewers for this issue—Drs. Puja Mehta, Monika Sanghavi, Stacey Rosen, Margo Minissian, and Annabelle Volgman—for their willingness to evaluate a sizeable number of manuscripts in a constrained time frame so as to permit timely publication for Heart Month.

To advance gender‐specific science and improve outcomes for women, we continue to pursue the multifaceted mission of investigate–educate–advocate–and legislate.8 These form the underpinnings for the enhancement of women's heart health.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare no potential conflicts of interest.

Gulati M, Wenger NK. You've come a long way, baby. Clin Cardiol. 2018;41:171–172. 10.1002/clc.22879

REFERENCES

- 1. Heart National, Lung and Blood Institute. National Institutes of Health. U.S. Department of Health & Human Services. About the heart truth. https://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/health/educational/hearttruth/about/index.htm. Updated March 17, 2016. Accessed December 13, 2017.

- 2. Benjamin EJ, Blaha MJ, Chiuve SE, et al; American Heart Association Statistics Committee and Stroke Statistics Subcommittee. Heart disease and stroke statistics‐2017 update: a report from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2017;135:e146–e603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Xu J, Murphy SL, Kochanek KD, Bastian BA. Deaths: final data for 2013. Natl Vital Stat Rep. 2016;64:1–119. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Gulati M. Improving the cardiovascular health of women in the nation: moving beyond the bikini boundaries. Circulation. 2017;135:495–498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Mieres JH, Gulati M, Bairey Merz N, et al. Role of noninvasive testing in the clinical evaluation of women with suspected ischemic heart disease: a consensus statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2014;130:350–379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Mosca L, Mochari‐Greenberger H, Dolor RJ, Newby LK, Robb KJ. Twelve‐year follow‐up of American women's awareness of cardiovascular disease risk and barriers to heart health. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2010;3:120–127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Congressional Research Service for the 114th Congress (2015‐2016). H.R.2101—Research for All Act of 2015. Congress.gov website. https://www.congress.gov/bill/114th-congress/house-bill/2101/text. Accessed December 1, 2017.

- 8. Perspective Wenger N.: a heartfelt plea. Nature 2017;550:S9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]