Summary

Introduction

Neural stem cells (NSCs) are the most promising cells for cell replacement therapy for Parkinson's disease (PD). However, a majority of the transplanted NSCs differentiated into glial cells, thereby limiting the clinical application. Previous studies indicated that chronic neuroinflammation plays a vital role in the degeneration of midbrain DA (mDA) neurons, which suggested the developing potential of therapies for PD by targeting the inflammatory processes. Thus, Nurr1 (nuclear receptor‐related factor 1), a transcription factor, has been referred to play a pivotal role in both the differentiation of dopaminergic neurons in embryonic stages and the maintenance of the dopaminergic phenotype throughout life.

Aim

This study investigated the effect of Nurr1 on neuroinflammation and differentiation of NSCs cocultured with primary microglia in the transwell coculture system.

Results

The results showed that Nurr1 exerted anti‐inflammatory effects and promoted the differentiation of NSCs into dopaminergic neurons.

Conclusions

The results suggested that Nurr1 protects dopaminergic neurons from neuroinflammation insults by limiting the production of neurotoxic mediators by microglia and maintain the survival of transplanted NSCs. These phenomena provided a new theoretical and experimental foundation for the transplantation of Nurr1‐overexpressed NSCs as a potential treatment of PD.

Keywords: coculture, inflammatory, microglia, neural stem cells, Nurr1

1. INTRODUCTION

Parkinson's disease (PD) is the second common neurodegenerative disorder after Alzheimer's disease and is increasingly prevalent with aging. The typical pathophysiological characteristics of PD include the progressive degeneration of dopaminergic neurons (DA neurons) in the substantia nigra pars compacta (SNpc) and accumulation of Lewy bodies containing misfolded α‐synuclein,1 yet the pathogenesis of PD is uncertain. However, previous studies have indicated that chronic neuroinflammation plays a vital role in the degeneration of midbrain DA (mDA) neurons.2, 3 A number of PD risk factors such as environmental toxins, heavy metals, head trauma, and bacterial or viral infections are involved in inflammation.4 Thus, development of potential therapies for PD specifically by targeting the inflammatory processes is imperative.

Current therapies for PD, including drugs and surgery, can only alleviate the symptoms and do not impede the progression of the disease.5, 6 Substantia nigra dopaminergic neurons, which project to the striatum, are mainly affected in PD. Therefore, cell‐based therapy by transplanting the dopamine‐releasing cells in the substantia nigra/striatum is a promising method for PD treatment. Neural stem cells (NSCs) are self‐renewing with multipotency cells and can differentiate into various neural cells, such as astrocytes, oligodendrocytes, and neurons including dopaminergic neurons.7 Transplantation of dopaminergic cells derived from embryonic stem cells in a rat model of PD has shown that the grafted cells can survive, differentiate, and extend the processes beyond the graft core and establish synaptic contacts with the host striatum.8, 9 Therefore, NSCs are considered as one of the most promising donor cells for the treatment of PD and other neurodegenerative diseases. However, most NSCs differentiated into glial cells instead of neurons.10 Moreover, only 5%‐10% of the NSCs survive after transplantation,11, 12, 13 which indicates that their unlikeliness to play the expected functions due to poor integration into the host neuronal circuits and inadequate release of neurotransmitter. Therefore, developing a method to improve the host microenvironment is essential. Thus, it can protect the mDA neurons against neuroinflammation insults and promote the survival of transplanted NSCs and differentiation into dopaminergic neurons for PD treatment.

Nuclear receptor‐related factor 1 (Nurr1, also known as NR4A2) is an orphan nuclear receptor, required for the transcription of tyrosine hydroxylase (TH), vesicular monoamine transporter (VMAT), and dopamine active transporter (DAT). Thus, Nurr1 plays a fundamental role in both the differentiation of dopaminergic neurons in embryonic stages and long‐term maintenance of the dopaminergic phenotype throughout life.14, 15, 16 Previous studies showed that Nurr1 is one of the nuclear targets relevant in PD pathology. A recent study17 demonstrated that Nurr1 plays an anti‐inflammatory role in microglia exposed to lipopolysaccharide (LPS) by removal of NF‐kB from the promoter regions of proinflammatory cytokines.18 Therefore, increased Nurr1 levels or activated Nurr1 may be a promising strategy for the treatment of PD, which considers the role of Nurr1 in maintaining dopaminergic neuronal phenotype and mitigating the proinflammatory signals.

In this study, we cocultured the Nurr1 gene overexpressing NSCs and microglia in transwell coculture system. Reportedly, the overexpressed Nurr1 suppressed the inflammatory reaction induced by activated microglia and promoted the differentiation of NSCs into dopaminergic neurons. The present results provided new theoretical and experimental evidence for the application of Nurr1‐overexpressed NSCs transplantation in the treatment of PD.

2. METHODS

2.1. Ventral mesencephalic neural stem cells (mNSCs) cultures

Animal experiments were conducted according to protocols approved by the United States National Institutes of Health Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals. Ventral mesencephalic neural tissue was harvested from fetal Sprague Dawley (SD) rats at embryonic day 14.5 (E14.5) under sterile conditions. The mNSCs were isolated, expanded, and detected according to the method described previously.19 Briefly, mNSCs were cultured in serum‐free DMEM/F12 medium containing 2% B27 (Gibco, Shanghai, China), supplemented with the mitogens basic fibroblast growth factor (bFGF; 20 ng/mL; PeproTech, USA) and epidermal growth factor (EGF; 20 ng/mL; PeproTech).

2.2. Microglia cultures

Primary cultures containing astrocytes and microglia were derived from the cerebrum of SD rat pups on postnatal day 1 (PN1), according to the protocol described previously.20 Briefly, the cerebrum was removed and minced and the cells cultured in DMEM/high‐glucose containing 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS, HyClone, USA). The cells were plated in 75‐cm2 T‐flasks; 12‐14 days after initial seeding, the microglia were separated by gentle shaking and collected for further use. The enriched microglia were >95% pure as determined by CD11‐B immunostaining.

2.3. Construction and transfection of recombinant pLenO‐DCE‐Nurr1

The coding sequence of human Nurr1 (GenBank NM_019328.3) was amplified by gene synthesis. Plasmid pLenO‐DCE, harboring the reporter gene of green fluorescent protein (GFP), was used as a vector. pLenO‐DCE‐Nurr1 recombinant plasmid was constructed by in a molar ratio of 1:3 (Nurr1 gene: pLenO‐DCE). The viral particles were generated by transient transfection into 293T cells. 10‐fold concentrated stocks were obtained by ultracentrifugation, resuspended in 1% bovine serum albumin (BSA; HyClone) in phosphate‐buffered saline (PBS; HyClone), and stored at −80°C. The titers of the concentrated GFP‐expressing virus (2.2 × 109 TU/mL) and Nurr1‐expressing virus (3.1 × 109 TU/mL) were determined in 293T cells. The cells were exposed to GFP‐expressing or Nurr1‐expressing virus for 18 hour at desired multiplicity of infection (MOI 200 for NSCs and MOI 2 for microglia). After 48 hour, GFP was observed under an inverted fluorescent microscope. RT‐PCR and Western blot were utilized to characterize Nurr1. The RT‐PCR primers are summarized in Table 1, and rabbit anti‐Nurr1 antibody (1:500; Abcam, Shanghai, China) was utilized for Western blot.

Table 1.

Primers for PCR

| Gene | Forward primer (5′–3′) | Reverse primer (5′–3′) |

|---|---|---|

| GAPDH | TGCCTCCTGCACCACCAACT | CCCGTTCAGCTCAGGGATGA |

| Nurr1 | AAGCCACCTTGCTTGTACCAAA | CTTGTAGTAAACCGACCCGCTG |

| TH | CTCCTCCTTGTCTCGGGCTGTA | CCGGGTCTCTAAGTGGTGAATT |

| Otx2 | CAACAGAACGGAGGTCAGAACA | GGGGTCAGACAGTGGGGAGA |

| Pitx3 | CCGCCTCCTCCCCTTATG | CGTGCTGCTTGGCTTTGA |

| DAT | TTGCAGCTGGCACATCTATC | ATGCTGACCACGACCACATA |

2.4. Effects of Nurr1 on microenvironment of microglia in different treatments

Microglia were isolated from mixed glial cell cultures of neonatal rat brain tissue as described above. Purified cells were divided into 4 groups: control group was treated with PBS, LPS group was treated with LPS (10 μg/mL); Nurr1 group was treated with PBS 48 hour post‐transfection with pLenO‐DCE‐Nurr1 (MOI 2), and LPS‐Nurr1 group was treated with LPS (10 μg/mL) 48 hour post‐transfection with pLenO‐DCE‐Nurr1 (MOI 2). The culture medium was harvested to evaluate the inflammation‐related factors (IL‐1 and TNF‐α) and neurotrophic factors (BDNF, GDNF, and PDNF) in the culture medium via ELISA (Sigma Aldrich, Shanghai, China) 24 hour post‐treatment with LPS/PBS.

2.5. Effects of Nurr1 and microglia microenvironment on the dopaminergic neuron differentiation of mNSCs

mNSCs and microglia were cocultured in the 24‐well transwell permeable support (polyester; thickness, 10 μm; pore size, 0.4 μm; pore density, 1 × 108 pores/cm2, Corning Company, USA). Cells were divided into 6 groups: mNSC (control), Nurr1‐overexpressed mNSCs (NmNSC), mNSC cocultured with microglia (mNSC+MG), mNSC cocultured with Nurr1‐overexpressed microglia (mNSC+NMG), Nurr1‐overexpressed mNSCs cocultured with microglia (NmNSC+MG), and Nurr1‐overexpressed mNSCs cocultured with Nurr1‐overexpressed microglia (NmNSC+NMG). RT‐PCR, Western blot, and immunofluorescence characterized the differentiation of NSCs after 3, 6, and 9‐days of coculture, respectively. RT‐PCR primers are summarized in Table 1. The antibodies for Western blot were rabbit anti‐rat DAT (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, 1:200),rabbit anti‐rat TH (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, 1:200), goat anti‐rat Pitx3 (Santa Cruz, Biotechnology, 1:200), rabbit anti‐rat Otx2 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, 1:200); while the primary antibodies for immunocytochemistry were rabbit anti‐rat DAT (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, 1:50), rabbit anti‐rat TH (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, 1:50), goat anti‐rat Pitx3 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, 1:50), and rabbit anti‐rat Otx2 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, 1:50).

2.6. Image processing and statistical analysis

Images were processed using ImageJ software (NIH) by researchers blinded to experimental conditions. The results were confirmed in more than 3 independent experiments. Statistical software SPSS 17.0 was used to perform statistical analysis. The statistical significance of differences between 2 groups was determined using independent samples t test. Unpaired Student's t test and 1‐way ANOVA was used to determine the statistical significance of differences among groups. P < .05 was considered as statistically significant.

3. RESULTS

3.1. Identification of Nurr1 overexpression in mNSCs and microglia

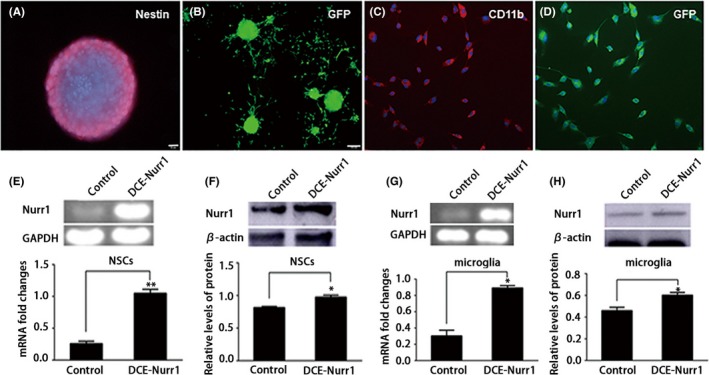

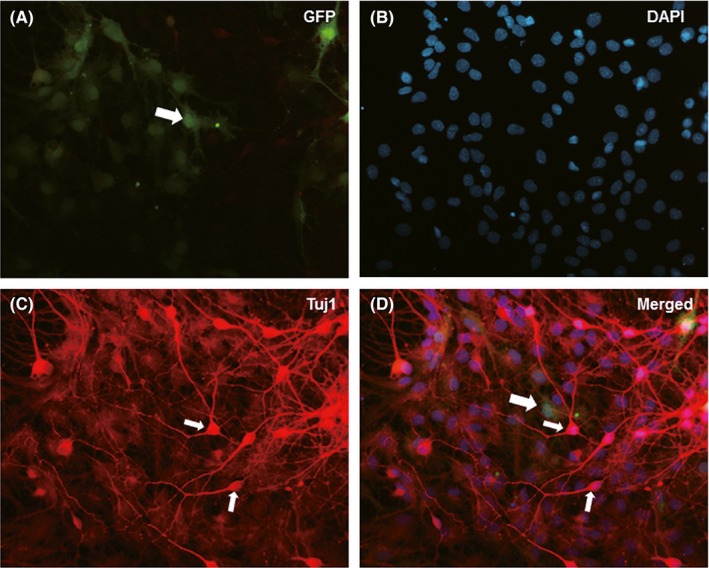

To study the efficiency of Nurr1 expression in mNSCs and microglia transfected with recombinant plasmids, we established the pLenO‐DCE‐Nurr1 recombinant plasmid containing the reporter gene of GFP. The fused expression of the reporter gene GFP (green) with Nurr1 emitted green fluorescence, which indicated that Nurr1 was expressed in mNSCs and microglia. The expression of GFP was observed 72 hour after transfection (Figure 1B,D). RT‐PCR and Western blotting analyses demonstrated that Nurr1 was overexpressed in Nurr1‐modified mNCSs and microglia (Figure 1E‐H). Next, to assess the effect of recombinant plasmid infection on mNSCs differentiation, we differentiated pLenO‐DCE‐Nurr1‐infected neurospheres 72 hour postinfection with 2% B27‐containing medium, in which, EGF and bFGF were removed. At 7 days after differentiation, most of the cells derived from neurospheres were positive for Tuj1 (Abcam) (Figure 2). These results suggested that mNSCs and microglia observed the overexpression of Nurr1 via pLenO‐DCE‐Nurr1 recombinant plasmid transfection and that it did not inhibit the self‐renewal of mesencephalic neural and their ability to differentiate into neurons.

Figure 1.

Identification of Nurr1 overexpression in mNSCs and MG. A, The neurosphere from E14.5 rat cerebrum was immunoreactive to the neuroepithelial marker nestin. B, Neurospheres were infected with pLenO‐DCE‐Nurr1 (MOI 200), and GFP‐expressing cells were observed at 72 h. C, Purified microglia were immunoreactive to CD11B. D, Microglia were infected with pLenO‐DCE‐Nurr1 (MOI 2), and GFP‐expressing cells were seen at 72 h. E, F, RT‐PCR and Western blot were performed for detection of Nurr1 expression in mNSCs. G, H, RT‐PCR and Western blot were performed for the detection of Nurr1 expression in microglia. Nuclei of these cells were stained with DAPI. Scale bar in A, C, and D, 20 μm; Scale bar in B, 100 μm. *P < .05, **P < .01 compared to the control group, unpaired Student's t test. The experiment was repeated 3 times in triplicate using independently prepared cells

Figure 2.

Differentiation of mNSCs after transduced by pLenO‐DCE‐Nurr1. Seven days after differentiation culture, the reporter protein, GFP, transfected into pLenO‐DCE‐Nurr1 (A) was still detectable in the cells derived from neurospheres. Most of the cells were immunoreactive to Tuj1 (C, D); small arrows in C and D showed the cell bodies of neurons. Scale bar in A–D, 20 μm

3.2. Nurr1 suppresses the production of inflammatory factors and promotes the expression of neurotrophic factors in microglia exposed to LPS

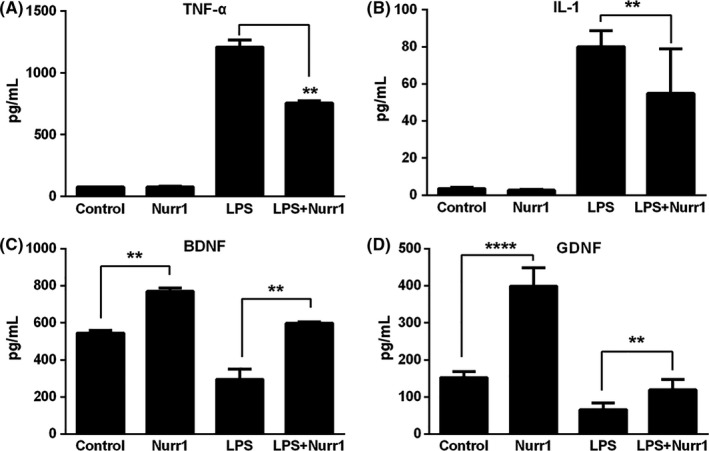

The effect of overexpressed Nurr1 in the primary microglia was evaluated. The microglia were divided into 4 groups as described above. The expression levels of proinflammatory cytokines and neurotrophic factors in the culture medium were measured by ELISA after microglia were exposed to LPS (10 μg/mL) for 24 hour. The results showed that, as compared to the LPS group, microglia‐overexpressed Nurr1 demonstrated significantly decreased levels of IL‐1 and TNF‐α (Figure 3A,B). On the other hand, the expression levels of brain‐derived neurotrophic factors (BDNF) and glial cell‐derived neurotrophic factors (GDNF) were increased in activated microglia overexpressed with Nurr1 (Figure 3C,D).

Figure 3.

Neuroprotective roles by Nurr1‐expressing primary microglia. A‐B, ELISA showed that, as compared to with the LPS group, Nurr1 overexpression microglia suppressed the inflammatory factors, including IL‐1 and TNF‐α. C‐D, Moreover, the neurotrophic factors were increased after infection by pLenO‐DCE‐Nurr1. **P < .01, ****P < .0001, compared to the LPS group, 1‐way ANOVA followed by Bonferroni post hoc test. The experiment was repeated 3 times in triplicate with independent preparation of the cells

3.3. Effects of overexpressed Nurr1 and microglia environment on dopaminergic differentiation of mNSCs

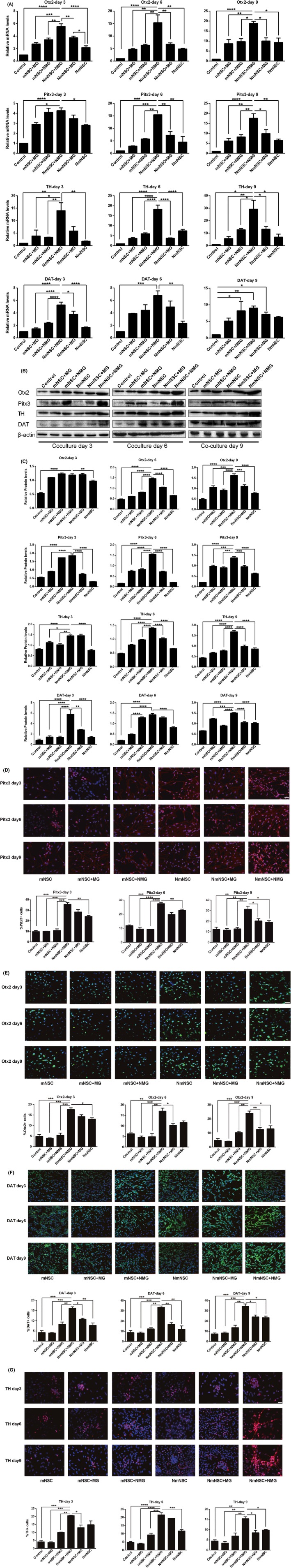

Next, we examined the overexpression of Nurr1 created a microenvironment conclusive for the survival of mNSCs and as well as their differentiation into DA neurons. Thus, we adopted the transwell coculture system mimicking the complex niche in vivo at SNpc, which contains mNSCs and microglia. In this transwell coculture system, the neurospheres were plated in the lower compartment, while microglia were seeded in the 0.4‐μm pore inserts. The cells were divided into 6 groups as described above. Previous studies identified some midbrain DA‐specific transcription factors, such as Otx2, Pitx3, TH, and DAT, that play essential roles in the development of mDA neurons from the early stage to full maturity.21, 22, 23 After 3‐, 6‐, and 9‐day coculture, the mNSCs were collected, and the transcription factors were assessed through real‐time PCR, Western blot, and immunocytochemistry, respectively. The results showed significantly higher expression levels as well as an abundance of cells labeled with DAT, TH, Otx2, and Pitx3 in Nurr1‐overexpressed NSCs cocultured with Nurr1‐overexpressed microglia compared to groups not transfected with Nurr1. (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Effect of Nurr1 overexpression and MG microenvironment on dopaminergic differentiation NSCs. A, Real‐time PCR showed that, as compared to the other groups, the mRNA expression levels of DAT, TH, Otx2, and Pitx3 were significantly higher in Nurr1‐overexpressed NSCs cocultured with Nurr1‐overexpressed microglia (NmNSC+NMG group). B–C, Western blot showed that, as compared to the other groups, the protein levels of DAT, TH, Otx2, and Pitx3 were high in the NmNSC+NMG group. D–G, Immunohistochemistry showed that, as compared to the other groups, abundant DAT, TH, Otx2, and Pitx3‐positive neurons were observed in the NmNSC+NMG group. *P < .05, **P < .01, ***P < .001, ****P < .0001, compared to the NmNSC+NMG group, 1‐way ANOVA followed by Bonferroni post hoc test. Scale bar in D‐G, 50 μm. The experiment repeated 3 times in triplicate using independently prepared cells

4. DISCUSSION AND CONCLUSION

Currently, the strategy using NSCs for PD treatment is transplantation that induces proliferation and dopaminergic differentiation of NSCs. The other research groups and we have shown that the motor symptoms of the PD animals were improved after cell transplantation.24, 25 However, the results were not satisfactory. One of the critical challenges of administering cell‐based therapies to PD is low survival, proliferation, and dopaminergic differentiation rate of transplanted NSCs due to hostile microenvironment.13, 26 Therefore, in order to treat PD by transplantation of NSCs, a strategy to improve the host microenvironment, promote the survival of transplanted NSCs, and their differentiation into dopaminergic neurons is essential.

Further evidence demonstrated that PD is associated with inflammatory mediators such as TNFα, nitric oxide (NO), and IL‐1, primarily derived from activated microglia.27, 28 In order to clarify the influence of Nurr1 on PD microenvironment and the differentiation of NSCs in vitro, we used the transwell system to mimic the interaction between the microglia microenvironment and NSCs. The results showed that the overexpression of Nurr1 not only suppressed the inflammation reaction of microglia, but it can also promote the differentiation of cocultured NSCs into dopaminergic neurons.

In the present study, we combined the Nurr1 gene with microglia to explore its roles in the PD as a therapeutic tool. First, the studies on the molecular mechanism of development and differentiation of dopaminergic neurons indicated that Nurr1 was one of the most important transcriptional factors involved in the development of dopaminergic neurons.29, 30 Deletion of the Nurr1 gene in mice resulted in a severe reduction in dopaminergic neurons and perinatal lethality.31, 32 Also, human mutations resulting in a reduced expression of Nurr1 are associated with late‐onset familial PD.33 Therefore, increased levels of Nurr1 may provide beneficial effects to the grafted NSCs. Herein, we showed that overexpression of Nurr1 could promote differentiation of mNSCs into DA neurons, as evident by positive immunocytochemistry staining for TH and DAT.

Secondly, previous studies demonstrated that the continuous release of proinflammatory cytokines by activated astrocytes and microglia led to the exacerbation of DA neuron degeneration in the SNpc.34 Hence, the chronic microglia activation was proposed to serve as a potential target for neuroprotective therapies in PD.35 Importantly, in addition to the essential roles in the development and maintenance of dopaminergic neurons, Nurr1 exerts a protective effect on neurons from inflammation‐induced neurotoxicity while acting as an inhibitor of inflammatory gene expression in microglia;17, 36 this theory was in agreement with that from a previous study.37 Furthermore, the reduction in Nurr1 expression in isolated microglia could result in the exaggerated production of neurotoxic factors in response to inflammatory stimuli.17

Taken together, the present results suggested that the level of proinflammatory cytokines produced by primary microglia was significantly decreased in the presence of Nurr1 overexpression. This phenomenon illustrated that in addition to promoting the differentiation of NSCs into DA neurons, Nurr1 exerts protective role in mDA neurons. Furthermore, the overexpression of Nurr1 in microglia can improve the inflammatory environment such that it may be detrimental to the mDA neurons effectuated not only by reduced levels of proinflammatory cytokines but also increased the level of neurotrophic factors. Therefore, the present results have provided a novel and potential strategy, whereby cells were transplanted with genetically modified NSCs: overexpression of Nurr1 in the treatment of PD.

DISCLOSURE

The authors confirm that the content of this article has no conflict of interest.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This work was supported by the grants (81241126 and 81360197) from the National Natural Sciences Foundation of China, (2013C227) Department of Science and Technology of Yunnan Province, and (2014FB041) the Joint Special Funds for the Department of Science and Technology of Yunnan Province—Kunming Medical University.

Chen X‐X, Qian Y, Wang X‐P, et al. Nurr1 promotes neurogenesis of dopaminergic neuron and represses inflammatory factors in the transwell coculture system of neural stem cells and microglia. CNS Neurosci Ther. 2018;24:790–800. 10.1111/cns.12825

The first two authors contributed equally to this work.

[Correction added on 09 March 2018, after first online publication: An additional affiliation was added to Yuan Qian.]

REFERENCES

- 1. Kalia LV, Lang AE. Parkinson's disease. Lancet. 2015;386:896‐912. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Hirsch EC, Vyas S, Hunot S. Neuroinflammation in Parkinson's disease. Parkinsonism Relat Disord. 2012;18(Suppl 1):S210‐S212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Ransohoff RM. How neuroinflammation contributes to neurodegeneration. Science. 2016;353:777‐783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Wirdefeldt K, Adami HO, Cole P, Trichopoulos D, Mandel J. Epidemiology and etiology of Parkinson's disease: a review of the evidence. Eur J Epidemiol. 2011;26(Suppl 1):S1‐S58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. LeWitt PA, Fahn S. Levodopa therapy for Parkinson disease: A look backward and forward. Neurology. 2016;86(14 Suppl 1):S3‐S12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Oertel W, Schulz JB. Current and experimental treatments of Parkinson disease: a guide for neuroscientists. J Neurochem. 2016;139(Suppl 1):325‐337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Martino G, Pluchino S. The therapeutic potential of neural stem cells. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2006;7:395‐406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Diaz‐Martinez NE, Tamariz E, Diaz NF, Garcia‐Pena CM, Varela‐Echavarria A, Velasco I. Recovery from experimental parkinsonism by semaphorin‐guided axonal growth of grafted dopamine neurons. Mol Ther. 2013;21:1579‐1591. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Drouin‐Ouellet J, Barker RA. The challenges of administering cell‐based therapies to patients with Parkinson's disease. NeuroReport. 2013;24:1000‐1004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Lindvall O, Kokaia Z, Martinez‐Serrano A. Stem cell therapy for human neurodegenerative disorders‐how to make it work. Nat Med. 2004;10(Suppl):S42‐S50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Jin G, Tan X, Tian M, et al. The controlled differentiation of human neural stem cells into TH‐immunoreactive (ir) neurons in vitro. Neurosci Lett. 2005;386:105‐110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Haas SJ, Beckmann S, Petrov S, Andressen C, Wree A, Schmitt O. Transplantation of immortalized mesencephalic progenitors (CSM14.1 cells) into the neonatal Parkinsonian rat caudate putamen. J Neurosci Res. 2007;85:778‐786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Brundin P, Karlsson J, Emgård M, et al. Improving the survival of grafted dopaminergic neurons: a review over current approaches. Cell Transplant. 2000;9:179‐195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Alavian KN, Jeddi S, Naghipour SI, Nabili P, Licznerski P, Tierney TS. The lifelong maintenance of mesencephalic dopaminergic neurons by Nurr1 and engrailed. J Biomed Sci. 2014;21:27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Smith GA, Rocha EM, Rooney T, et al. A Nurr1 agonist causes neuroprotection in a Parkinson's disease lesion model primed with the toll‐like receptor 3 dsRNA inflammatory stimulant poly(I:C). PLoS ONE. 2015;10:e0121072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Luo Y. The function and mechanisms of Nurr1 action in midbrain dopaminergic neurons, from development and maintenance to survival. Int Rev Neurobiol. 2012;102:1‐22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Saijo K, Winner B, Carson CT, et al. A Nurr1/CoREST pathway in microglia and astrocytes protects dopaminergic neurons from inflammation‐induced death. Cell. 2009;137:47‐59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Lallier SW, Graf AE, Waidyarante GR, Rogers LK. Nurr1 expression is modified by inflammation in microglia. NeuroReport. 2016;27:1120‐1127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Azari H, Sharififar S, Rahman M, Ansari S, Reynolds BA. Establishing embryonic mouse neural stem cell culture using the neurosphere assay. J Vis Exp. 2011;47:e2457. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Tamashiro TT, Dalgard CL, Byrnes KR. Primary microglia isolation from mixed glial cell cultures of neonatal rat brain tissue. J Vis Exp. 2012;66:e3814. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Ang SL. Transcriptional control of midbrain dopaminergic neuron development. Development. 2006;133:3499‐3506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Smits SM, Smidt MP. The role of Pitx3 in survival of midbrain dopaminergic neurons. J Neural Transm Suppl. 2006;70:57‐60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Saucedo‐Cardenas O, Quintana‐Hau JD, Le WD, et al. Nurr1 is essential for the induction of the dopaminergic phenotype and the survival of ventral mesencephalic late dopaminergic precursor neurons. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:4013‐4018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Deng X, Liang Y, Lu H, et al. Co‐transplantation of GDNF‐overexpressing neural stem cells and fetal dopaminergic neurons mitigates motor symptoms in a rat model of Parkinson's disease. PLoS ONE. 2013;8:e80880. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Grow DA, McCarrey JR, Navara CS. Advantages of nonhuman primates as preclinical models for evaluating stem cell‐based therapies for Parkinson's disease. Stem Cell Res. 2016;17:352‐366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Sortwell CE, Pitzer MR, Collier TJ. Time course of apoptotic cell death within mesencephalic cell suspension grafts: implications for improving grafted dopamine neuron survival. Exp Neurol. 2000;165:268‐277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. De Virgilio A, Greco A, Fabbrini G, et al. Parkinson's disease: autoimmunity and neuroinflammation. Autoimmun Rev. 2016;15:1005‐1011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Herrero MT, Estrada C, Maatouk L, Vyas S. Inflammation in Parkinson's disease: role of glucocorticoids. Front Neuroanat. 2015;9:32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Jankovic J, Chen S, Le WD. The role of Nurr1 in the development of dopaminergic neurons and Parkinson's disease. Prog Neurobiol. 2005;77:128‐138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Rodriguez‐Traver E, Solis O, Diaz‐Guerra E, et al. Role of Nurr1 in the generation and differentiation of dopaminergic neurons from stem cells. Neurotox Res. 2016;30:14‐31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Zetterstrom RH, Solomin L, Jansson L, Hoffer BJ, Olson L, Perlmann T. Dopamine neuron agenesis in Nurr1‐deficient mice. Science. 1997;276:248‐250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Jiang C, Wan X, He Y, Pan T, Jankovic J, Le W. Age‐dependent dopaminergic dysfunction in Nurr1 knockout mice. Exp Neurol. 2005;191:154‐162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Nichols WC, Uniacke SK, Pankratz N, et al. Evaluation of the role of Nurr1 in a large sample of familial Parkinson's disease. Mov Disord. 2004;19:649‐655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Wang Q, Liu Y, Zhou J. Neuroinflammation in Parkinson's disease and its potential as therapeutic target. Transl Neurodegener. 2015;4:19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Joers V, Tansey MG, Mulas G, Carta AR. Microglial phenotypes in Parkinson's disease and animal models of the disease. Prog Neurobiol. 2016;155:57‐75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Wei X, Gao H, Zou J, et al. Contra‐directional Coupling of Nur77 and Nurr1 in Neurodegeneration: a novel mechanism for memantine‐induced anti‐inflammation and anti‐mitochondrial impairment. Mol Neurobiol. 2016;53:5876‐5892. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Oh SM, Chang MY, Song JJ, et al. Combined Nurr1 and Foxa2 roles in the therapy of Parkinson's disease. EMBO Mol Med. 2015;7:510‐525. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]