Abstract

Background

We aimed to explore electrophysiological characteristics of premature atrial contractions (PACs) originating from pulmonary veins (PVs) and non‐PVs and to evaluate the effectiveness and safety of catheter ablation for PACs.

Hypothesis

Symptomatic PACs originated from different positions and whether could be ablated.

Methods

Symptomatic, frequent, and drug‐refractory PAC patients were enrolled in this study. All patients underwent electrophysiological study and catheter ablation.

Results

A total of 81 patients were enrolled: 45 patients with PACs originating from PVs (group A), 24 patients with PACs originating from non‐PVs (group B), and 12 patients with PACs arising from both PVs and non‐PVs (group C). Twenty (44.4%) patients in group A, 6 (50.0%) patients in group C, and 3 (12.5%) patients in group B presented paroxysmal atrial fibrillation (P < 0.05). PV isolation was performed in groups A and C. Focal ablation or superior vena cava isolation was performed in groups B and C, depending on patient condition. PACs were abolished in all patients except one patient in group B. During a median follow‐up period of 21.3 ± 14.3 months, 40 (88.9%) patients in group A, 10 (83.3%) patients in group C, and 21 (87.5%) patients in group B were free of recurrence after initial ablation.

Conclusions

Frequent PACs originating from PVs were associated with increased incidence of atrial fibrillation compared with PACs originating from non‐PVs. Catheter ablation yields a satisfactory success rate and could be a good choice for eliminating symptomatic, frequent, and drug‐refractory PACs.

Keywords: Atrial Fibrillation, Catheter Ablation, Electrophysiological Techniques, Premature Atrial Contractions, Pulmonary Vein Isolation

1. INTRODUCTION

Catheter ablation is at the forefront of the management of a range of atrial arrhythmias, including focal atrial tachycardia (AT), atrial flutter, and atrial fibrillation (AF).1 However, only a few reports on catheter ablation of premature atrial contractions (PACs) are available.2, 3, 4 Frequent PACs are occasionally symptomatic and refractory to multiple antiarrhythmic drugs.2, 3, 4 Frequent PACs are typically associated with an increased risk of AF and stroke.2, 5, 6, 7

In fact, PACs may be a target for catheter ablation. PACs arising from the pulmonary veins (PVs) are the main triggers of AF and may be easily treated by PV isolation.8, 9 However, there are few studies on the ablation of PACs originating from non‐PVs, given the low incidence and the variety of sites.10, 11 Furthermore, the differences between PACs arising from PVs and those associated with non‐PV origins are unknown. To date, no guidelines are available recommending catheter ablation for PACs in patients. Given that the technique and efficacy of ablation have been established for the treatment of arrhythmias, it will be valuable to recognize the electrophysiological characteristics of PACs originating from PVs and non‐PVs and of ablation for PACs.

This study aims to evaluate the electrophysiological features of frequent PACs originating from PVs and non‐PVs and to study the effectiveness and safety of catheter ablation for these types of PACs.

2. METHODS

2.1. Patient selection

Our study included patients who presented with symptomatic PACs from January 2012 to April 2017 at Nanfang Hospital of Southern Medical University in China. These patients with symptomatic, frequent, and drug‐refractory PACs exhibited the following clinical presentations: frequent incidence (>5 bpm on average), single or few P‐wave morphologies in the main PACs on the surface electrocardiogram (ECG), and few or short episodes of AT or AF. Patients with recent ischemic events (<1 month) or abnormal thyroid function were excluded.

All patients ceased antiarrhythmic medications other than amiodarone for ≥5 half‐lives before the study, and amiodarone was paused for ≥1 month. All patients provided written informed consent for ablation.

2.2. Electrophysiology study and mapping

Before the ablation procedure, all patients received either low‐molecular‐weight heparin for ≥7 days or continuous warfarin therapy for 1 month. Patients underwent transthoracic and transesophageal echocardiography to exclude thrombosis in the left atrial appendage. Each patient underwent a standard diagnostic electrophysiological study (EPS) before radiofrequency (RF) ablation. Local anesthesia with lidocaine was applied for vein catheterization. Electrophysiological mapping was performed on patients with spontaneously induced PACs, or PACs were induced by isoproterenol infusion (2–20 μg/min) prior to electrophysiological mapping. Intracardiac electrograms (30–500 Hz bandpass filter) were recorded with a multiple‐channel digital system and displayed at a speed of 50 to 100 mm/s.

One 6‐Fr steerable decapolar catheter was placed in the coronary sinus (CS) via the subclavian vein or femoral vein for recording and stimulation. First, the ectopic P‐wave pattern on surface ECGs and the activation sequence of CS were used to identify the origin site of the PACs.2 The ECG algorithm was primarily based on the morphology of the ectopic P wave on lead V1,12 which was the most useful for differentiating between the left (positive P wave) and right (negative P wave) atrial focal sites. In addition, proximal‐to‐distal CS activation suggested PACs of a right‐side origin, and distal‐to‐proximal CS activation indicated PACs of a left‐side origin.

Three‐dimensional (3D) electroanatomic mapping was performed in groups A and C using the CARTO 3 system (Biosense Webster, Diamond Bar, CA). After 2 transseptal procedures, two L1‐type Swartz sheaths (St. Jude Medical, Minneapolis, MN) were introduced into the left atrium (LA). After the first transseptal puncture, anticoagulation was achieved with heparin using a single 100‐IU/kg bolus followed by continuous intravenous infusion at 1000 IU/h. Intracardiac recordings and surface ECGs were recorded for analysis. If the pulmonary vein potentials (PVPs) preceded the A wave and other atrial sites, then the PV was considered the site of origin. LA geometry was constructed, and PV isolation was performed in both groups. Then, non‐PV origins were searched by mapping the superior vena cava (SVC) or other non‐PV areas. The activation sequence was displayed in a color‐coded manner on the left or right atrial geometry. Care was taken to exclude the PACs caused by mechanical bumping. The earliest activation site was suggested as the possible site of origin.

Conventional activation mapping or 3D mapping using the CARTO 3 system was performed in group B. Based on the morphology of the ectopic P wave, the right atrium (RA) was initially mapped during PACs. If the site of the earliest activation was located in the RA, detailed mapping of the earliest atrial activation was performed around that area. In addition, a long sheath (Swartz SR0; St. Jude Medical) was required to support more stable contact with the origin of PACs. If the earliest atrial activation site was close to the left side or His bundle area, or the PACs did not terminate during RA RF ablation, access to the left heart was achieved using the transseptal puncture technique for mapping, or mapping in the aortic cusps was achieved via a retrograde aortic approach.13, 14 Aortic angiography was performed prior to aortic cusp mapping to delineate the anatomy of the coronary cusps.

2.3. Radiofrequency ablation

The site with the earliest atrial activation and successful ablation was defined as the origin of the arrhythmia. The PV was identified as the foci of PACs in groups A and C. Mild sedation was achieved by the administration of intravenous fentanyl and propofol for ablation. Similar to AF ablation, circumferential pulmonary vein isolation (CPVI) was performed to isolate all PVs. Prior to CPVI, an irrigated catheter or a ThermoCool SmartTouch catheter (St. Jude Medical) was inserted into the LA via another transseptal puncture. First, the ostia of PVs were tagged on the LA geometry by selective PV angiography and/or 3D mapping. Then, RF energy was delivered for PV isolation with a power output of 30 to 35 W under fluoroscopic and CARTO guidance. The temperature of the tip was maintained at <43 °C with 0.9% heparin sodium chloride (normal saline) at an irrigation rate of 17 mL/min based on the patient's condition. Finally, PV isolation was confirmed by the disappearance of the PVP or the dissociation of PVPs with atrial electrical activity. In group C, non‐PVs foci were found after CPVI, and focal ablation was performed at the earliest activation site.

In group B, RF ablation was typically delivered at the earliest activation site but was avoided in the His area. RF energy was delivered at 30 to 35 W and 43 °C. If PACs disappeared within 20 seconds, then the RF delivery would be prolonged to 40 to 60 seconds and the ablation would be performed around the target point. Otherwise, the ablation would be stopped, and mapping was applied again. If the earliest activation site was close to the His area, mapping in the noncoronary cusp (NCC) was performed. If activation timing at the NCC was similar or slightly later than that at the RA septum (≤5–10 ms), radiofrequency application at the earliest activation site was initiated at 20 W and titrated to ≤30 to 35 W for a maximum temperature of 55 °C (if the saline‐irrigated catheter was used, then RF energy was typically delivered at a low saline irrigation flow of 2 mL/min) to avoid the potential risk of damaging atrioventricular (AV) node conduction.13, 15

Successful ablation in PAC patients was defined as the disappearance of PACs by RF application and the lack of PAC induction by burst atrial pacing (to a cycle length as short as 200 ms) during an isoproterenol challenge ≥30 minutes after the last RF application.

2.4. Patient follow‐up

All patients underwent 24‐hour Holter monitoring prior to discharge. Therapeutic warfarin anticoagulation was applied during the blanking period in groups A and C. No antiarrhythmic drugs were applied, except for β‐blocker drugs. Clinical success was defined as freedom from the recurrence of frequent PACs during follow‐up, and most patients were followed up at 3‐month intervals. Atrial arrhythmia symptoms were assessed based on the patients' complaints. In addition, 12‐lead ECG and 24‐hour Holter monitoring were performed if necessary.

2.5. Statistical analysis

All values are expressed as the mean ± SD. Independent samples t tests were performed in this study. Discrete variables were expressed as counts and compared by Pearson χ2 test or Fisher exact test. The recurrence‐free survival probability was estimated using the Kaplan–Meier method and compared using the log‐rank test. A 2‐tailed P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS software, version 20.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY).

3. RESULTS

3.1. Baseline characteristics and procedural data

A total of 81 patients with an average age of 53.9 ± 14.2 years were included in the study. The mean PACs were 13 199 ± 5744 per 24 hours (range, 7234–30 652). The baseline characteristics of the 3 groups are presented in the Table 1. No significant differences were noted between groups A and C; however, the mean age was younger, and the average PAC rate was increased in group B. Furthermore, a history of AF was more prevalent in groups A and C.

Table 1.

Comparison of baseline characteristics among the 3 groups

| Group A, n = 45 | Group B, n = 24 | Group C, n = 12 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, y | 57.6 ± 14.9a | 45.2 ± 9.1 | 57.3 ± 13.0a |

| Sex, M/F | 28/17 | 11/13 | 7/5 |

| BMI, kg/m2 | 23.1 ± 3.0 | 22.2 ± 2.9 | 22.9 ± 2.6 |

| History of PACs, mo | 18.4 ± 13.5 | 16.4 ± 11.1 | 16.9 ± 15.1 |

| No. of PACs | 10 202 ± 2681a | 19 879 ± 5233 | 11 041 ± 3376a |

| Proof of AF, n (%) | 20 (44.4)a | 3 (12.5) | 6 (50)a |

| LAD, mm | 40.6 ± 5.9 | 38.1 ± 4.3 | 39.0 ± 5.1 |

| LVEF, % | 53.5 ± 7.8 | 56.3 ± 4.6 | 53.7 ± 6.2 |

| CHA2DS2‐VASc score | 1.9 ± 1.2 | 1.6 ± 1.0 | 1.9 ± 1.1 |

| Stroke, n (%) | 3 (6.7) | 0 (0) | 1 (8.3) |

Abbreviations: AF, atrial fibrillation; BMI, body mass index; CHA2DS2‐VASc, congestive HF, HTN, age A, age, ≥75 y, DM, stroke/TIA, vascular disease, age 65–74 y, sex category (F); DM, diabetes mellitus; F, female; HF, heart failure; HTN, hypertension; LAD, left atrial dimension; LVEF, left ventricular ejection fraction; M, male; SD, standard deviation; TIA, transient ischemic attack.

Data are expressed as mean ± SD unless otherwise noted.

There was significant difference compared with group B.

3.2. Results of PAC mapping and ablation in the 3 groups

During PAC mapping, concurrent arrhythmia was observed in 4 patients, including slow‐fast AV nodal re‐entrant tachycardia (n = 3) and fast‐slow AV nodal re‐entrant tachycardia (n = 1). All patients were successfully ablated.

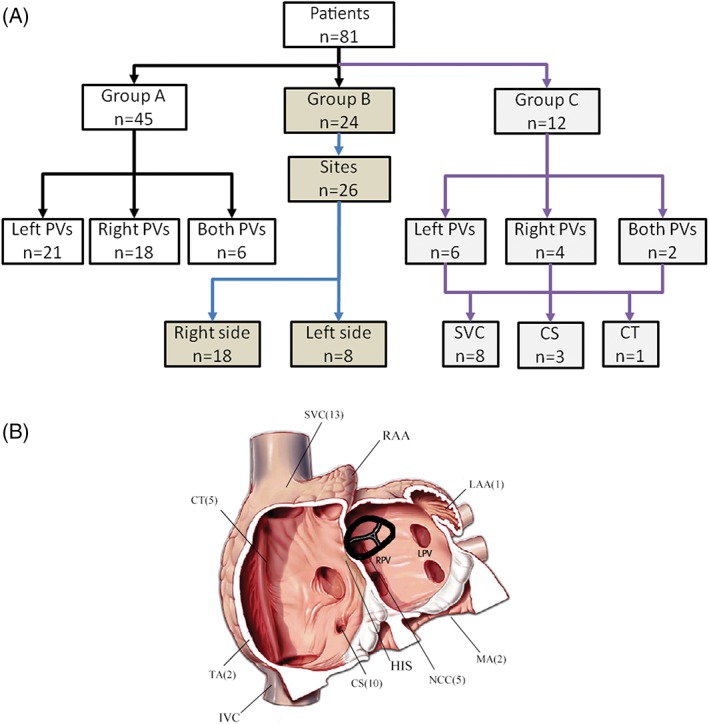

Clinical PACs were spontaneous in 65 (80.2%) patients and inducible with isoproterenol in 16 (19.8%) patients. In group A, circular or high‐resolution mapping revealed that ectopic foci were in left‐sided PVs in 21 patients, in right‐sided PVs in 18 patients, and in both sides in 6 patients (Figure 1A). CPVI was performed and successfully abolished the PACs. After a 30‐minute wait, PV reconnection was observed in 3 (6.7%) patients, and re‐ablation was performed.

Figure 1.

(A) Study profile detailing the outcomes of 81 patients who underwent catheter ablation for PACs. (B) Total anatomic distribution of PACs from groups B and C. Common anatomic distribution of non‐PVs arising PACs depicting total case distributions recorded in our study. Abbreviations: CS, coronary sinus; CT, crista terminalis; IVC, inferior vena cava; LAA, left atrial appendage; LPV, left pulmonary veins; MA, mitral annulus; NCC, noncoronary cusp; PAC, premature atrial contraction; PV, pulmonary vein; RAA, right atrial appendage; RPV, right pulmonary veins; SVC, superior vena cava; TA, tricuspid annulus

In group C, ectopic foci were located in left‐sided PVs in 6 patients, in right‐sided PVs in 4 patients, and in both sides in 2 patients. CPVI was successfully performed. Then, other atrial ectopic foci were examined. A total of 12 atrial ectopic foci were identified (Figure 1B), including 8 foci located at the SVC, 3 foci located at the CS, and 1 focus at the crista terminalis (CT). All patients were successfully ablated, and none of them required re‐ablation during the waiting time.

In group B, 26 sites of focal PAC origins were identified in 24 patients (Figure 2). The origins of PACs were on the right side in 18 cases (16 patients) and on the left side in 8 cases (8 patients). Among the patients who underwent successful ablation on the right side, the 18 origins were distributed as follows: 7 at the CS, 5 in the SVC, 4 at the CT, and 2 at the tricuspid annulus. During the mapping of PACs, the distal electrode of the ablation catheter recorded an activation that preceded the P‐wave onset by 32.4 ± 9.2 ms (range, 18–54 ms) at the site of the successful ablation.

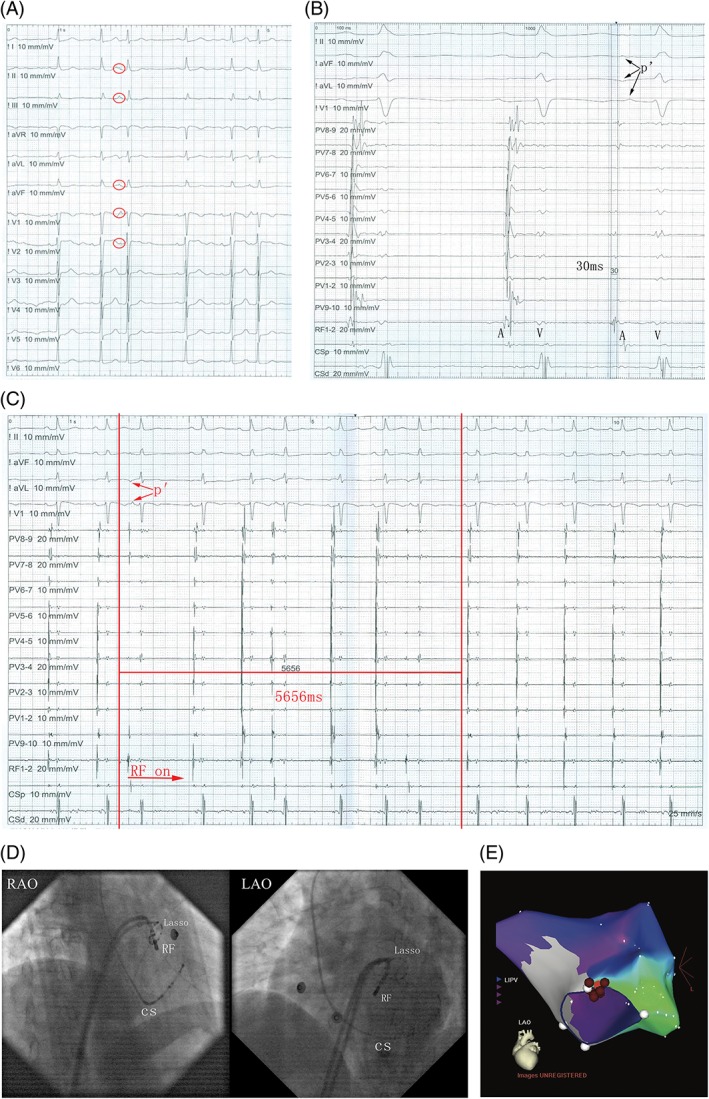

Figure 2.

(A) The ECG reveals sinus heart rhythm with PACs. (B) The potential detected by the ablation catheter preceded P‐wave onset by 30 ms. (C) The PACs dissipated in 5656 ms following the delivery of RF energy. (D) The precise RF fluoroscopy position is depicted at LAO 45° and RAO 30°. (E) The 3D mapping shows the origination of PACs. The pink dot indicates the earliest activation point of PACs and red dots indicate the ablation points. Abbreviations: 3D, three‐dimensional; CS, coronary sinus; ECG, electrocardiogram; LAO, left anterior oblique; LIPV, left inferior pulmonary vein; PAC, premature atrial contraction; RAO, right anterior oblique; RF, radiofrequency

Among the 8 patients who underwent successful mapping on the left side, the 8 origins of atrial arrhythmia were as follows: 5 at the NCC, 2 at the mitral annulus, and 1 at the left atrial appendage. However, ablation failed in 1 patient due to the origin being too close to the His area. For successfully ablated PACs, the distal electrode of the ablation catheter recorded an activation that preceded the P‐wave onset by 22.5 ± 8.8 ms (range, 16–48 ms) at the site of the successful ablation. A young woman suffered from drug‐resistant palpitation for >3 years. Her 12‐lead ECG revealed a sinus rhythm with PACs in a trilogy form (Figure 2A). The PACs exhibited a high P wave at the inferior axis and positive P in V1. Twenty‐four‐hour Holter monitoring revealed that the PACs burden was 30%. Her echocardiographic examinations and laboratory tests, including thyroid function, were within the normal range. An EPS was performed under a fasting state after obtaining informed consent. The ECG and EPS indicated that the PACs originated from the left heart. We then used the transseptal puncture technique for mapping. The distal electrode of the ablation catheter recorded the earliest activation potential at the apical annulus of the mitral valve. The potential detected by the ablation catheter preceded the P‐wave onset by 30 ms (Figure 2B). RF power was delivered, and the PACs disappeared in 5656 ms (Figure 2C). The precise RF fluoroscopy position is presented in Figure 2D, and the 3D mapping is presented in Figure 2E.

The procedures were performed on 81 patients, and no major complications occurred. No significant changes in the AV nodal conduction time were observed (the P‐R intervals before and after ablation were 168 ± 6.4 ms and 174 ± 8.3 ms, respectively; P > 0.05). The procedure time and fluoroscopy time were 146.3 ± 46.3 and 12.5 ± 8.1 minutes, respectively.

3.3. Clinical effectiveness during follow‐up

After the RF ablation, antiarrhythmic drugs were no longer administered to patients. The average PACs in patients were decreased to 439.3 ± 146.1 per 24 hours (range, 0–2434) at 3.5 ± 1.0 days after the ablation.

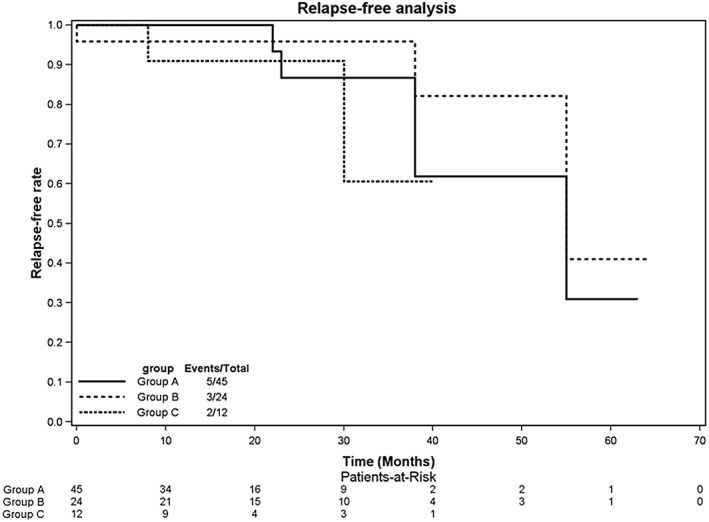

The occurrence of PACs after discharge was assessed based on patient complaints, 12‐lead ECG, and 24‐hour Holter monitoring. During the 21.3 ± 14.3 months of follow‐up, 40 (88.9%) patients in group A and 10 (83.3%) patients in group C were free of recurrent atrial arrhythmias after the initial procedure. Four of 7 patients who experienced recurrence underwent re‐ablation. During re‐ablation, PV reconnection was identified. After CPVI, all PVs were re‐isolated. In group B, 21 (87.5%) patients were free from PAC recurrence at the end of follow‐up. However, 2 patients with NCC origins experienced PAC recurrence but refused re‐ablation. The recurrence‐free survival curve after the first ablation is presented in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

Kaplan–Meier curves comparing freedom from atrial arrhythmia recurrence after ablation. No significant differences in recurrence‐free probability were noted among the 3 groups

4. DISCUSSION

4.1. Major findings

There were several main findings in this study. First, symptomatic, frequent, and drug‐refractory PACs can be successfully ablated. Second, the PV, CS, SVC, annulus, and NCC were the most common origin sites. Third, a significant difference in origins was noted between PACs that induced AF and those that did not induce AF. PACs that trigger AF typically originate from PVs.

4.2. Mapping and ablation of PACs

In our study, the mapping of PACs was rather successful. The morphology of the P wave on ECGs and the activation sequence of CS provided useful information for the determination of the PAC origin site.12 Anatomic localization of the atrial focus was undertaken in the presence of PACs, which are necessary for mapping. The use of 3D mapping systems allows for more effective mapping. In the area of interest, precise mapping was achieved with a steerable ablation catheter to locate the earliest site of activation. After careful mapping, we confirmed that PVs were the most common sites of PAC origin; the CS, SVC, CT, annulus, and NCC were other potential origins. Anatomic localization of the PAC origin site was similar to the localization of focal ATs.1, 12

CPVI is the standard ablation strategy for AF. Furthermore, most atrial arrhythmias, including focal ATs and PACs, originate from the PV and could easily be ablated by PV isolation. Wang et al. reported only culprit ipsilateral PV isolation2; however, both PVs were isolated in our study. In previous studies, Hu et al16 reported that for focally triggered PAF, selective ipsilateral CPVI of triggering PV had a high success rate of freedom from AF in patients age < 50 years with an LA diameter < 40 mm. However, in patients age ≥ 50 years with an LA diameter ≥ 40 mm, bilateral CPVI achieved a higher success rate. In our study, the average age was 57.6 ± 14.9 years in group A and 57.3 ± 13.0 years in group C with PACs originating from PVs. In our opinion, PV isolation could not only eliminate the PACs, but also reduce potential AF incidence. The follow‐up results supported the use of CPVI for the treatment of PACs arising from PVs and revealed that PAC recurrence was due to PV reconnection.

If the PACs did not arise from PVs, precise mapping was very important. In fact, PAC ablation might be more challenging than PVC ablation due to the difficulty in identifying the P‐wave morphology pre‐ablation as well as potentially uncertain mapping and ablating.2 P‐wave and CS activation were very important. According to our results, the SVC, CS, CT, annulus, and NCC were the typical origins not only for focal AT,1, 2, 4, 8, 13, 14, 15 but also for PACs.2 These findings should help guide the decision to pursue further mapping in those anatomic locations. In the area of interest, precise mapping is performed with a steerable ablation catheter to locate the earliest site of activation. RF energy is then delivered to this focus. The use of 3D mapping systems allows for more effective mapping.

Ablation near the para‐His area has been a challenge, given its proximity to the AV node. In our study, the ablation site for 1 PAC patient was too close to the para‐Hisian, and 2 patients experienced recurrent PACs. An increasing number of studies have reported that most of the ATs near the para‐His can be eliminated from within the NCC with minimal risk. Thus, the NCC is typically the preferential ablation site.2, 13, 14, 15 We mapped para‐Hisian PACs in the NCC via the retrograde aortic approach and eliminated most of the PACs. Furthermore, the risk–benefit of para‐Hisian PAC ablation should be considered. The potential risk of AV block should be kept in mind if repeated RF ablation is performed in this area.

4.3. The relationship between the origins of PACs and AF

Our study showed that 20 (44.4%) patients in group A, 6 (50.0%) patients in group C, and 3 (12.5%) patients in group B (P < 0.05) presented with paroxysmal AF or had a history of AF. Thus, PACs arising from PVs are more likely to lead to AF. The result was consistent with that from previous studies.2, 8 Nevertheless, PACs with a non‐PV origin may be another source for AF, and the SVC or CS is the most popular site. Regardless of origin, catheter ablation can be used to treat PACs.

5. CONCLUSION

In this study, we found that focal PACs commonly originate from PVs, which are more likely to lead to AF. The SVC, CS, para‐His area, CT, and annulus were common PAC origin sites. For focal PACs, catheter ablation could represent better treatment due to high success rates and very low complication rates in experienced electrophysiological centers.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare no potential conflicts of interest.

Huang X, Chen Y, Xiao J, et al. Electrophysiological characteristics and catheter ablation of symptomatic focal premature atrial contractions originating from pulmonary veins and non‐pulmonary veins. Clin Cardiol. 2018;41:74–80. 10.1002/clc.22853

Funding information This research was partly supported by the Guangdong Provincial Science and Technology Program (2013B021800140), Guangzhou Science and Technology Project (201300000146), the Southern Medical University Clinical Research Project (LC2016ZD002), and the President's Fund of Nanfang Hospital (2016B015).

REFERENCES

- 1. Lee G, Sanders P, Kalman JM. Catheter ablation of atrial arrhythmias: state of the art. Lancet. 2012;380:1509–1519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Wang X, Li Z, Mao J, He B. Electrophysiological features and catheter ablation of symptomatic frequent premature atrial contractions. Europace. 2017;19:1535–1541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Hasdemir C, Simsek E, Yuksel A. Premature atrial contraction–induced cardiomyopathy. Europace. 2013;15:1790. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Ip JE, Lerman BB. Deceptive nature of atrial premature contractions: ablating 2 arrhythmias with 1 burn. Circulation. 2014;130:e148–e150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Suzuki S, Sagara K, Otsuka T, et al. Usefulness of frequent supraventricular extrasystoles and a high CHADS2 score to predict first‐time appearance of atrial fibrillation. Am J Cardiol. 2013;111:1602–1607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Weber‐Krüger M, Gröschel K, Mende M, et al. Excessive supraventricular ectopic activity is indicative of paroxysmal atrial fibrillation in patients with cerebral ischemia. PLoS One. 2013;8:e67602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Chong BH, Pong V, Lam KF, et al. Frequent premature atrial complexes predict new occurrence of atrial fibrillation and adverse cardiovascular events. Europace. 2012;14:942–947. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Haïssaguerre M, Jaïs P, Shah DC, et al. Spontaneous initiation of atrial fibrillation by ectopic beats originating in the pulmonary veins. N Engl J Med. 1998;339:659–666. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Chen SA, Hsieh MH, Tai CT, et al. Initiation of atrial fibrillation by ectopic beats originating from the pulmonary veins: electrophysiological characteristics, pharmacological responses, and effects of radiofrequency ablation. Circulation. 1999;100:1879–1886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Dobran IJ, Niebch V, Vester EG. Successful radiofrequency catheter ablation of atrial trigeminy in a young patient. Heart. 1998;80:301–302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Yamada T, Murakami Y, Okada T, et al. Electroanatomic mapping in the catheter ablation of premature atrial contractions with a non‐pulmonary vein origin. Europace. 2008;10:1320–1324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Kistler PM, Roberts‐Thomson KC, Haqqani HM, et al. P‐wave morphology in focal atrial tachycardia: development of an algorithm to predict the anatomic site of origin. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2006;48:1010–1017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Wang Z, Ouyang J, Liang Y, et al. Focal atrial tachycardia surrounding the anterior septum: strategy for mapping and catheter ablation. Circ Arrhythm Electrophysiol. 2015;8:575–582. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Wang Y, Li D, Zhang J, et al. Focal atrial tachycardia originating from the septal mitral annulus: electrocardiographic and electrophysiological characteristics and radiofrequency ablation. Europace. 2016;18:1061–1068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Toniolo M, Rebellato L, Poli S, et al. Efficacy and safety of catheter ablation of atrial tachycardia through a direct approach from noncoronary sinus of Valsalva. Am J Cardiol. 2016;118:1847–1854. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. JQ Hu, Ma J, Ouyang F, et al. Is selective ipsilateral PV isolation sufficient for focally triggered paroxysmal atrial fibrillation? Comparison of selective ipsilateral pulmonary vein isolation versus bilateral pulmonary vein isolation. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol. 2012;23:130–136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]