Abstract

Background

Cardiac resynchronization therapy (CRT) is highly beneficial in patients with heart failure (HF) and left bundle branch block (LBBB); however, up to 30% of patients in this selected group are nonresponders.

Hypothesis

We hypothesized that clinical and echocardiographic variables can be used to develop a simple mortality risk stratification score in CRT.

Methods

Best‐subsets proportional‐hazards regression analysis was used to develop a simple clinical risk score for all‐cause mortality in 756 patients with LBBB allocated to the CRT with defibrillator (CRT‐D) group enrolled in the multicenter automatic defibrillator implantation trial with cardiac resynchronization therapy. The score was used to assess the mortality risk within the CRT‐D group and the associations with mortality reduction with CRT‐D vs implantable cardioverter defibrillator (ICD) in each risk category.

Results

Four clinical variables comprised the risk score: age ≥ 65, creatinine ≥ 1.4 mg/dL, history of coronary artery bypass graft, and left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) < 26%. Every 1 point increase in the score was associated with 2‐fold increased mortality within the CRT‐D arm (P < 0.001). CRT‐D was associated with mortality reduction as compared with ICD only in patients with moderate risk: score 0 (HR = 0.80, P = 0.615), score 1 (HR = 0.54, P = 0.019), score 2 (HR = 0.54, P = 0.016), score 3‐4 risk factors (HR = 1.08, P = 0.811); however, the device by score interaction was not significant (P = 0.306). The score was also significantly predictive of left ventricular reverse remodeling (P < 0.001).

Conclusions

Four clinical variables can be used for improved mortality risk stratification in mild HF patients with LBBB implanted with CRT‐D.

Keywords: cardiac resynchronization therapy, heart failure, left bundle branch block, risk factors

1. INTRODUCTION

Cardiac resynchronization therapy (CRT) has been shown to reduce heart failure (HF)‐related morbidity in patients with mild HF and prolonged QRS duration in numerous clinical trials in the last decade.1, 2, 3, 4, 5 Analysis of the long‐term data from the multicenter automatic defibrillator implantation trial with cardiac resynchronization therapy (MADIT‐CRT) trial provided further evidence of mortality reduction with CRT in this population.4 The beneficial effects of CRT were shown mainly in patients with left bundle branch block (LBBB).4, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10 Accordingly, current guidelines emphasize LBBB and QRS duration as the major determinants that should be considered prior to CRT implantation.11, 12

Although prior data suggested that most patients with mild HF and LBBB respond to CRT treatment, some patients are still considered nonresponders. Currently, there are limited data regarding risk stratification within the LBBB subgroup. Due to the high cost of CRT devices, recurrent procedures that are needed for maintenance over the time, and the possibility of procedural complications, it is very important to identify patient subgroups that are less likely to respond to this therapy.

Therefore, the aim of our study was to assess clinical factors that are associated with mortality in CRT with defibrillator (CRT‐D) treated patients with LBBB from the MADIT‐CRT that can be used to identify both clinical and echocardiographic responders to CRT.

2. METHODS

2.1. Study population

The study population comprised of 1281 patients enrolled in the MADIT‐CRT trial with LBBB on baseline electrocardiogram (70% of the original 1820 patient cohort). Of these 1281 subjects, 756 patients were included in the risk score derivation as described below; these patients had been randomized to CRT‐D and had complete data regarding the variables of interest. The design, follow‐up, and results of the MADIT‐CRT trial have been reported previously.4, 5, 13 The respective institutional review boards at each participating site in the trial approved the study protocol. Briefly, patients who had ischemic cardiomyopathy (New York Heart Association [NYHA] class I or II) or nonischemic cardiomyopathy (NYHA class II), left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) ≤ 30%, normal sinus rhythm, and QRS duration ≥ 130 ms were randomized to receive CRT‐D or ICD therapy in a 3:2 ratio. Definition for LBBB was published previously.9 Patients were followed for a median of 5.6 years, which included two phases of post‐trial follow‐up (Clinical trial registration: ClinicalTrials.gov numbers NCT00180271, NCT01294449, and NCT02060110).

2.2. Echocardiography protocol and definitions

Echocardiograms were obtained according to a study‐specific protocol at baseline, before device implantation and at 1‐year after device implantation. An independent core laboratory, at the Brigham and Women's Hospital in Boston, Massachusetts, analyzed the echocardiography recordings off‐line. Echocardiography investigators analyzing the images were blinded to treatment assignment or clinical outcome. Left ventricular volumes were measured using the Simpson's disk method in the apical 4‐ and 2‐chamber views, and LVEF was calculated.14

2.3. Definitions and outcome measures

We used the end points of the original MADIT‐CRT trial.5, 13 The primary end point in the current study was all‐cause mortality (secondary end‐point in the original trial). The cause of mortality was adjudicated and classified by independent morbidity and mortality committee to either cardiac, noncardiac, or unknown based on information provided by the enrolling centers using the Hinkle‐Thaler classification.15 Secondary end points included death classified by cause (cardiac or noncardiac), the combined outcome of HF hospitalization or death (primary end‐point in the original trial), and the change in either LVEF, left ventricular end systolic volume (LVESV), left ventricular end diastolic volume (LVEDV) or left atrial volume (LAV) after 12 months with CRT‐D treatment, calculated as the percent change compared to baseline measures.

2.4. Risk score

We developed a risk score to predict the likelihood of mortality for LBBB patients within the CRT‐D treatment arm on the 756 subjects who had complete data on the covariates of interest in the MADIT‐CRT trial. A best‐subsets regression analysis16 was conducted using 47 prespecified candidate variables (continuous and categorical, shown in Table 1) that were previously shown to be associated with mortality.17, 18, 19, 20 In our study, the models of varying sizes chosen by the best subsets procedure were each estimated to check on the statistical significance of each of the variables in each model by the Wald test. Each of the covariates in the final four variable model, including: age ≥ 65 years, creatinine≥1.4 mg/dL, history of CABG, and LVEF, were significant (P < 0.05).

Table 1.

Univariate analysis of mortality risk factors in the cardiac resynchronization therapy with defibrillator treatment arm (these variables were considered in the multivariate model)

| Risk factor (covariate) | HR | 95% CI | P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 1.04 | 1.02‐1.06 | <0.001 |

| Age ≥ 65 years | 2.12 | 1.37‐3.27 | <0.001 |

| Creatinine (mg/dL) | 3.88 | 2.35‐6.40 | <0.001 |

| Creatinine ≥ 1.4 (mg/dL) | 2.91 | 1.92‐4.41 | <0.001 |

| BUN (mg/dL) | 1.04 | 1.03‐1.06 | <0.001 |

| BUN > 25 (mg/dL) | 2.16 | 1.42‐3.28 | <0.001 |

| GFR (mg/dL) | 0.98 | 0.96‐0.99 | <0.001 |

| GFR ≥ 60 (mg/dL) | 0.42 | 0.28‐0.63 | <0.001 |

| Brain natriuretic peptide (pg/mL) | 1.02 | 1.01‐1.03 | <0.001 |

| History of CABG | 2.63 | 1.74‐3.97 | <0.001 |

| History of non‐CABG revascularization | 2.28 | 1.52‐3.43 | <0.001 |

| Ischemic cardiomyopathy | 2.58 | 1.66‐4.00 | <0.001 |

| Prior MI | 2.12 | 1.41‐3.19 | <0.001 |

| LVEF (% ) | 0.92 | 0.87‐0.97 | 0.005 |

| LVEDV indexed by BSA (mL/m2) | 1.01 | 1.00‐1.01 | 0.052 |

| LVESV indexed by BSA (mL/m2) | 1.01 | 1.00‐1.02 | 0.017 |

| Female gender | 0.51 | 0.30‐0.86 | 0.011 |

| African‐American race | 1.25 | 0.58‐2.71 | 0.573 |

| Prior atrial arrhythmia | 2.35 | 1.38‐3.98 | 0.002 |

| Prior ventricular arrhythmia | 1.77 | 0.91‐3.42 | 0.090 |

| Weight (kg) | 1.00 | 0.99‐1.01 | 0.837 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 0.98 | 0.94‐1.02 | 0.256 |

| BMI ≥ 30 (kg/m2) | 0.75 | 0.48‐1.18 | 0.211 |

| Prior cerebrovascular accident | 1.26 | 0.55‐2.89 | 0.582 |

| Active smoking | 1.35 | 0.72‐2.54 | 0.352 |

| History of smoking | 1.22 | 0.80‐1.88 | 0.355 |

| Hypertension | 1.34 | 0.86‐2.07 | 0.197 |

| SBP (mmHg) | 1.00 | 0.99‐1.01 | 0.877 |

| SBP < 110 mmHg | 1.10 | 0.65‐1.87 | 0.712 |

| SBP ≥ 140 mmHg | 0.93 | 0.54‐1.57 | 0.779 |

| DBP (mmHg) | 1.00 | 0.98‐1.02 | 0.735 |

| DBP > 80 (mmHg) | 0.88 | 0.49‐1.58 | 0.660 |

| Heart rate | 0.98 | 0.96‐1.00 | 0.051 |

| Heart rate ≥ 80 (bpm) | 0.56 | 0.27‐1.16 | 0.118 |

| Diabetes | 1.32 | 0.86‐2.02 | 0.202 |

| NYHA class | 0.74 | 0.41‐1.34 | 0.323 |

| 6‐min walk (m) | 0.99 | 0.99‐0.99 | 0.008 |

| Prior CHF hospitalization | 1.25 | 0.83‐1.87 | 0.293 |

| Prior hospitalization (any cause) | 1.56 | 1.03‐2.35 | 0.034 |

| QRS duration (ms) | 1.00 | 0.99‐1.01 | 0.913 |

| QRS ≥ 150 (ms) | 0.90 | 0.57‐1.44 | 0.666 |

| Aspirin | 1.18 | 0.75‐1.83 | 0.478 |

| ACE inhibitor or ARB | 0.49 | 0.21‐1.14 | 0.100 |

| Beta‐blocker | 0.51 | 0.26‐0.98 | 0.043 |

| Aldosterone‐blocker | 1.12 | 0.74‐1.71 | 0.590 |

| Statin | 1.15 | 0.75‐1.77 | 0.520 |

| Diuretic | 1.74 | 1.04‐2.91 | 0.034 |

Abbreviations: ACE, Angiotensin‐converting enzyme; ARB, Angiotensin II receptor blocker; BMI, body mass index; BSA, Body surface area; BUN, blood urea nitrogen; CHF, Congestive heart failure; CI, confidence of interval; CABG, coronary artery bypass graft; GFR, glomerular filtration rate; HR, Heart rate; LVEDV, left ventricular end diastolic volume; LVEF, left ventricular ejection fraction; LVESV, left ventricular end systolic volume; MI, myocardial infarction; NYHA, New York Heart Association; SBP, systolic blood pressure.

In order to develop a practical risk score, we then categorized LVEF at the lowest quintile to have dichotomized versions of each variable in the model. Next, because the hazard ratios from the proportional hazards regression model were similar (1.6‐2.2), we assigned a score of 1 to each of the factors. Thus, the risk score was simply the number of factors for which a patient was positive and ranged in value from 0 to 4. Because only 13 patients achieved a score of “4” they were combined with the 56 patients with a score of “3” to create one high‐risk group; thus, leading to a total of four risk group categories (scores 0, 1, 2, and 3‐4).

2.5. Statistical analysis

Baseline clinical characteristics were compared between patients according to the risk score group in the CRT‐D treatment arm and in the entire cohort, using the χ 2‐test or Fisher's exact test for categorical variables, as appropriate. We used the Kruskal‐Wallis test for comparisons of continuous variables. Categorical data are presented as frequencies and percentages and continuous variables as means and standard deviations. The cumulative probability of long‐term mortality and HF/death were displayed according to the Kaplan‐Meier method in two different analyses: (1) by risk score within the CRT‐D treatment arm only and (2) by treatment arm (CRT‐D vs ICD) within each risk score group, with comparisons of cumulative event rates by the log‐rank test.

Multivariate Cox proportional hazards regression analysis was used to assess the association of risk score on the outcomes of long‐term mortality and HF/death in two different analyses. In the first analysis, the outcome was compared by the risk score within the CRT‐D group patients. In a second analysis, patients with CRT‐D were compared to patients with ICD within each score category to assess the associations with outcomes in each risk sub‐group, the model was further adjusted to baseline utilization on angiotensin covering enzyme inhibitor, angiotensin receptor blocker and diuretic since they were found to vary significantly among the four risk groups as well as have statistically significant association with the risk of mortality. All the multivariate models were stratified by the enrolling center. P values for interaction between the risk score groups for treatment were computed and reported.

Two methods were utilized to validate the stability of variable selection for development of risk score, which are described in more detail in the Supporting information Appendix S1. A bootstrap sample with replacement of size 20 was used to (1) show the frequency with which the components of the risk score were chosen and (2) assess the strength of concordance between the score algorithm used in the manuscript with those chosen in each of the samples.

All statistical tests were two‐sided, and a P value of <0.05 was considered statistically significant. Analyses were carried out with SAS software (version 9.4, SAS institute, Cary, North Carolina).

3. RESULTS

Candidates' prespecified risk variables and their association with mortality among the CRT‐D group are shown in Table 1. Risk factor selections are shown in Tables 2 and 3.

Table 2.

Multivariate proportional hazards regression model for the risk of mortality in the cardiac resynchronization therapy with defibrillator treatment arm for selected risk variables

| Risk factor (covariate)a | HR | 95% CI | P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age ≥ 65 years | 1.74 | 1.09‐2.76 | 0.019 |

| Creatinine ≥ 1.4 mg/dL | 2.21 | 1.44‐3.39 | <0.001 |

| History of CABG | 1.99 | 1.29‐3.07 | 0.002 |

| LVEF % | 0.92 | 0.86‐0.98 | 0.006 |

Abbreviations: CI, confidence of interval; CABG, coronary artery bypass graft; HR, Heart rate; LVEF, left ventricular ejection fraction.

The model was derived from a best subsets regression analysis and was further stratified by the enrolling center.

Six patients had missing data and were not included in the model.

Table 3.

Categorized variables used to build the risk score

| Risk factor (covariate) | Definition | Score | HRa | 95% CI | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age ≥ 65 years | Yes | 1 | 1.67 | 1.05‐2.64 | 0.031 |

| Creatinine≥1.4 mg/dL | Yes | 1 | 2.21 | 1.44‐3.41 | <0.001 |

| History of CABG | Yes | 1 | 2.06 | 1.34‐3.17 | 0.001 |

| LVEF % (first quintile) (<26%) | Yes | 1 | 1.56 | 0.98‐2.48 | 0.061 |

Abbreviations: CI, confidence of interval; CABG, coronary artery bypass graft; HR, Heart rate; LVEF, left ventricular ejection fraction.

The model is stratified by the enrolling center.

During mean ± SD follow‐up period of 4.62 ± 1.76 years a total of 183 patients died, of which 93 were from the CRT‐D treatment arm. The crude mortality rate by risk categories is shown in Table 4 (CRT‐D arm) and Table S1 (entire cohort).

Table 4.

Baseline demographic and clinical characteristics of patients from the cardiac resynchronization therapy with defibrillator treatment arm stratified by the number of risk factors

| Clinical characteristics | 0 risk factor (n = 212) | 1 risk factor (n = 303) | 2 risk factors (n = 172) | 3‐4 risk factors (n = 69) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age at enrollment (years) | 54.7 ± 7.5 | 65.3 ± 10.7 | 69.5 ± 7.8 | 74.0 ± 5.7* |

| Female | (40) | (37) | (21) | (4)* |

| Black race | (9) | (7) | (9) | (3) |

| SBP (mmHg) | 122.2 ± 16.1 | 123.9 ± 16.9 | 124.6 ± 16.5 | 124.5 ± 19.6 |

| Heart rate (bpm) | 68.7 ± 9.9 | 68.6 ± 11.1 | 65.7 ± 10.0 | 66.4 ± 11.7* |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 29.8 ± 5.3 | 28.2 ± 5.4 | 27.9 ± 5.0 | 27.7 ± 4.2* |

| Smoking history | (43) | (58) | (57) | (63)* |

| Diabetes | (19) | (29) | (40) | (39)* |

| Hypertension | (52) | (60) | (74) | (72)* |

| Cerebrovascular accident | (4) | (5) | (8) | (1) |

| Ischemic | 21 | (36) | (66) | (91)* |

| Prior CABG | (0) | (9) | (48) | (84)* |

| Prior PCI | (14) | (21) | (26) | (42)* |

| Time from revascularization, years | 2.5 ± 3.1 | 4.2 ± 3.9 | 5.1 ± 5.5 | 5.5 ± 4.9* |

| Prior atrial arrhythmias | (3) | (9) | (15) | (20)* |

| Prior VT/VF | (3) | (7) | (6) | (12) |

| BUN mg/dL | 17.5 ± 6.1 | 19.7 ± 6.4 | 24.8 ± 9.7 | 29.4 ± 11.7* |

| Creatinine mg/dL | 0.98 ± 0.19 | 1.05 ± 0.23 | 1.30 ± 0.35 | 1.56 ± 0.35* |

| BNP level | 66.1 ± 134.3 | 111.4 ± 121.7 | 146.0 ± 167.9 | 252.7 ± 219.0* |

| QRS | 160.3 ± 16.7 | 162.9 ± 18.8 | 162.9 ± 21.3 | 163.2 ± 19.8 |

| PR interval (ms) | 190 ± 27 | 196 ± 30 | 203 ± 36 | 210 ± 40* |

| 6‐min walk (m) | 393.2 ± 99.7 | 359.0 ± 109.2 | 349.7 ± 97.0 | 334.8 ± 102.4* |

| Aspirin | (57) | (57) | (74) | (65)* |

| ACE inhibitor or ARB | (99) | (95) | (97) | (90)* |

| Beta‐blocker | (99) | (94) | (90) | (90)* |

| Statin | (52) | (62) | (74) | (81)* |

| Diuretic | (62) | (64) | (73) | (81)* |

| Antiarrhythmic | (2) | (4) | (11) | (17)* |

| LVEF (% ) | 30.0 ± 2.5 | 28.6 ± 3.5 | 28.6 ± 3.7 | 26.7 ± 3.7* |

| LVEDV indexed by BSA | 119.7 ± 23.7 | 127.0 ± 30.0 | 125.1 ± 26.7 | 134.2 ± 36.4* |

| LVESV indexed by BSA | 83.9 ± 17.9 | 91.3 ± 24.4 | 89.8 ± 21.8 | 99.2 ± 31.2* |

| LAV indexed by BSA | 43.2 ± 8.0 | 47.4 ± 9.6 | 47.9 ± 9.7 | 53.9 ± 12.1* |

| Crude mortality rate | (5) | (9) | (18) | (35)* |

Abbreviations: BMI, body mass index; BUN, blood urea nitrogen; CI, confidence of interval; CABG, coronary artery bypass graft; GFR, glomerular filtration rate; LAV, left atrial volume, LVEDV, left ventricular end diastolic volume; LVEF, left ventricular ejection fraction; LVESV, left ventricular end systolic volume; MI, myocardial infarction.

Numbers are mean ± SD, values in parentheses are percentages.

Denotes P value < 0.05 for the comparison between the age risk factors groups.

Baseline clinical characteristics of the CRT‐D treatment arm (n = 756) and of the entire study population (n = 1263) by risk category are shown in Table 4 and Table S1, respectively. Among 756 study patients from the CRT‐D treatment arm, 212 (28%) had no risk factors, 303 (40%) had 1 risk factor, 172 (23%) had 2 risk factors, and 69 (9%) had 3 to 4 risk factors. Overall, patients with 3 to 4 risk factors were older and more likely to be males. This group also had significantly higher rates of diabetes, hypertension, and ischemic heart disease. They further displayed characteristics of more severe HF including higher BNP levels, shorter 6‐minute walk distance, higher echocardiographic volumes, and higher rates of diuretic therapy. However, they had lower rates of beta‐blockers and aldosterone antagonist therapy.

3.1. Relation of risk score to clinical outcomes within the CRT‐D treatment arm

The cumulative probability of mortality within the CRT‐D group was significantly correlated with risk category in a univariate Kaplan‐Meier estimate (Figure 1A). Accordingly, in multivariate Cox analysis the risk for mortality was significantly associated with the score (Table 5 left panel). The same association was observed for the combined outcome of HF/death (Figure S1 and Table S2 left panel).

Figure 1.

Cumulative probability of mortality according to number of risk factors in the cardiac resynchronization therapy with defibrillator treatment arm. The numbers in parentheses are Kaplan‐Meier event rates

Table 5.

Risk score and outcome in the main study population: multivariate analysis for the end point of death

| Risk group | Events/patients | Main effect in CRT‐D group | Events/patients | CRT‐D vs ICD | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HRa | CI | P | HRb | CI | P | |||

| Continuous score | 93/756 | 2.01 | 1.63‐2.49 | <0.001 | 183/1266 | 1.67 | 1.36‐2.06 | <0.001 |

| 0 risk factor | 11/212 | 0.13 | 0.07‐0.27 | <0.001 | 20/357 | 0.80 | 0.33‐1.93 | 0.615 |

| 1 risk factor | 27/303 | 0.23 | 0.13‐0.040 | <0.001 | 59/500 | 0.54 | 0.32‐0.90 | 0.019 |

| 2 risk factors | 31/172 | 0.51 | 0.29‐0.87 | 0.013 | 63/286 | 0.54 | 0.33‐0.89 | 0.016 |

| 1‐2 risk factors | 58/475 | 0.33 | 0.20‐0.53 | <0.001 | 122/786 | 0.56 | 0.39‐0.79 | 0.001 |

| 3‐4 risk factors | 24/69 | 1 | Reference | 41/123 | 1.08 | 0.58‐2.02 | 0.811 | |

Abbreviations: CI, confidence of interval; CRT‐D, cardiac resynchronization therapy with defibrillator; ICD, implantable cardioverter defibrillator.

High risk factors included: age ≥ 65 years, creatinine ≥ 1.4 mg/dL, CABG, LVEF % (first quintile) (<26%) the model is stratified by the enrolling center.

The model is stratified by the enrolling center and adjusted to treatment arm baseline utilization of ace inhibitor, angiotensin receptor blocker, diuretic and risk factor group, either four risk groups (0, 1, 2, and 3‐4) and risk score by risk factor group interaction, or three risk groups (0,1‐2, and 3‐4) and risk score by risk factor group interaction. P for interaction for 1 risk factor vs 3 + 4 risk factors = 0.094, P for interaction for 2 risk factors vs 3 + 4 risk factors = 0.092, P for interaction for 1 to 2 risk factors vs 3 + 4 risk factors = 0.069, P for interaction for the entire comparison.

3.2. Relation of risk score to reverse remodeling after 12 month with CRT‐D treatment

Echocardiographic volume changes after 12 months with CRT‐D treatment are shown in Figure S4. There was a significant correlation between the risk score and the magnitude of reverse remodeling, in that there were pronounced volume reductions (LVESV, LVEDV, and LAV) with low risk scores that attenuated with increasing risk scores. LVESV reduction was a significant predictor of outcomes but did it not add to the predictive value of our risk score (P value for interaction for LVESV change and risk score > 0.10).

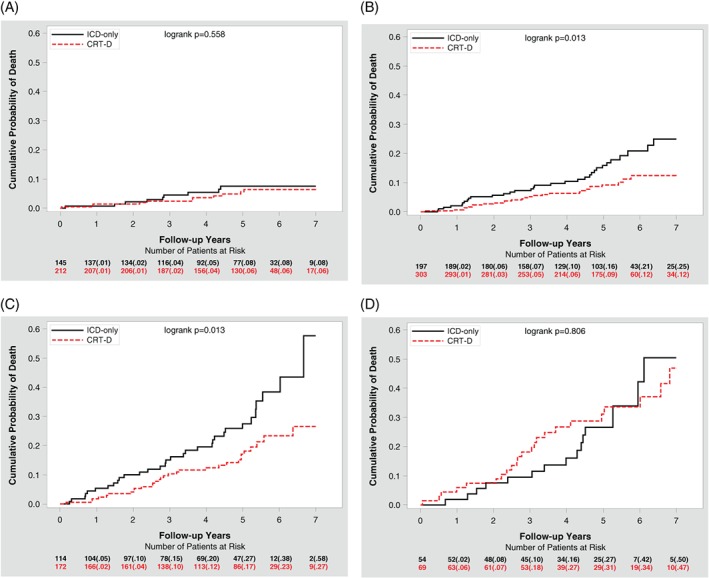

3.3. Clinical outcomes with CRT‐D as compared with ICD by the risk score category

The cumulative probability of mortality with CRT‐D vs ICD in each risk category is shown in Figure 2. Patients with 0 risk factor and patients with 3 to 4 risk factors experienced no significant difference in mortality between the two treatment arms. However, patients in the intermediate risk category (those with 1 or 2 risk factors) experienced a significant reduction in mortality with CRT‐D therapy. Thus, the association of mortality reduction is more pronounced in patients with intermediate risk scores and attenuated in those with higher or lower scores (Figure S3A and B). The risk score was also predictive of cardiac death in both treatment arms, and of both cardiac and noncardiac death in the CRT‐D arm (Figure S3C and D).

Figure 2.

Cardiac resynchronization therapy with defibrillator vs implantable cardioverter defibrillator mortality reduction by number of risk factors. A, No risk factors, B, 1 risk factor, C, 2 risk factors, and D, 3 to 4 risk factors. The numbers in parentheses are Kaplan‐Meier event rates

The above‐mentioned results were confirmed with Cox multivariate analysis, which showed that mortality risk within the CRT‐D arm increased with increasing risk scores, and that the association with mortality reduction with CRT‐D vs ICD was only evident in patients with either 1 or 2 risk factors (Table 5 right panel). There was no association with mortality reduction with either 0 risk factor or 3 to 4 risk factors; however, none of the treatment arm by risk score interactions were significant (all P for interaction > 0.05).

With regard to the secondary endpoint of combined HF or death in the main study population, both Kaplan‐Meier and multivariate analysis showed that in patients with 0 risk factor CRT‐D therapy was significantly associated with reduced risk, while in those with 3 to 4 risk factors, it was not (see Figure S2 and Table S2 right panel).

3.4. Sensitivity analysis

In a sensitivity analysis, we excluded patients with NYHA class I, QRS < 150 ms, and LVEF 31% to 35%, and the results were similar.

In looking at the risk score at a shorter period of follow‐up (less than 3 years), treatment effects were not different.

4. DISCUSSION

Our findings have several important clinical implications regarding risk stratification and selection for CRT‐D therapy in patients with mildly symptomatic systolic HF and LBBB. We have identified four clinical and echocardiographic variables (age, creatinine, history of CABG, and LVEF) that were associated with mortality in patients within the CRT‐D treatment arm. The risk score identified patients who were at increased risk for mortality while on CRT‐D therapy, as well as associations with mortality reduction with CRT‐D as compared to ICD treatment. Specifically, patients with 0 risk factor (low‐risk category) and patients with 3 to 4 risk factors (high‐risk category) showed no association with mortality reduction with CRT‐D therapy, while in patients with 1 or 2 risk factors (intermediate risk categories), CRT‐D was associated with a 45% reduction in mortality. When the combined outcome of mortality or HF admission was assessed, the association of reduced risk with CRT‐D was more pronounced in the intermediate risk group as compared with the low‐risk group, but the lack of this association in the high‐risk group persisted. It should be noted however that the treatment by risk score group interaction was not significant in any of those comparisons.

Three of the four variables used in our risk score (age, creatinine, and LVEF) have been found in previous studies to be significant predictors of mortality in HF patients treated with CRT.17, 18 These same three variables are also components of multiple well‐validated mortality risk stratification tools for HF patients in general, including the HF survival score,21 PACE risk score,19 and SHOCKED score.20 The remaining risk factor, history of CABG, is a more novel variable, but obviously correlates with a history of coronary ischemia, which has also been found to be a significant risk factor for mortality in HF patients both with and without CRT.17, 21 It is believed that patients with frank ischemia requiring surgical revascularization have a significant burden of nonviable myocardium; although CRT would aid in reducing electrical dyssynchrony in patients with ill‐performing hearts, its effect may be limited by the degree of concomitant mechanical dyssynchrony from permanently damaged myocardium.22 One major study found that approximately 70% of patients with systolic dysfunction undergoing CABG did not experience reduction in dyssynchrony at median follow‐up period of about 1 year.23 Additionally, in patients undergoing CABG, patients with myocardial scarring were more likely to have reduced LVEF, and the degree of scar burden was a predictor of long‐term mortality.24 Thus, residual post‐CABG dyssynchrony and scar burden could provide mechanistic explanations for the poor prognosis seen in patients with history of CABG.

Previous studies have suggested that concomitant CRT could be beneficial in patients undergoing CABG.25 Our study further clarifies previous reports by demonstrating that CRT is most beneficial in the subset of post‐CABG patients who carry some, but not numerous, additional risk factors.

Though our final model utilizes only four of the numerous variables that were found to be statistically significant risk factors for mortality in our study population, these four variables are in many cases closely interrelated with those that were left out of the model, and are therefore indirectly representative of many of these other risk factors. Examples include the correlation between creatinine, BUN, and GFR; LVEF with LVESV; and, as mentioned above, history of CABG with prior MI and ischemic cardiomyopathy.

Previous studies have shown a significant mortality benefit with ICD therapy in patients with systolic HF.26, 27, 28 The MADIT‐CRT,4 REVERSE,1 and RAFT29 trials demonstrated a mortality benefit when resynchronization therapy was added to ICD therapy in patients with mild systolic heart failure and prolonged QRS, with this positive effect restricted to those patients with LBBB.6, 9

Our study applies to patients receiving CRT‐D for primary prevention and with NYHA class I to II HF. These clinical criteria differ from other registries, such as the National Cardiovascular Data Registry ICD, which was amassed in the spirit of secondary prevention and 36% of patients had NYHA class III to IV heart failure.30

Our data show that patients with relatively low baseline mortality risk have nearly equal likelihood of cardiac vs noncardiac death regardless of the addition of resynchronization therapy. Given the considerably low overall risk of death in this group, it is not surprising that these patients do not experience a significant mortality reduction with CRT‐D therapy in the timeframe of our study. Similarly, patients with the highest baseline mortality risk show no significant mortality reduction with the addition of resynchronization therapy. CRT‐D therapy in these high‐risk patients is associated with the smallest magnitude of reverse remodeling, perhaps explaining why these patients do not show any significant association of mortality reduction with CRT‐D in terms of cardiac death. These patients likely have the most advanced degree of underlying cardiac and systemic disease; thus, limiting their ability for recovery with CRT‐D therapy. Patients with all four risk factors should be further studied to clarify risk stratification.

In total, the present study proposes a novel scoring system to identify patients who may best benefit from CRT‐D therapy. The consolidation of the aforementioned four major risk factors into a simple scoring schema may allow providers to easily identify appropriate patients for CRT‐D therapy and can further provide guidance in the device selection for patients with mild HF and LBBB morphology.

4.1. Limitations of the study

Our study has several important limitations. First, it is limited by the potential biases inherent in post hoc studies. Thus, there may have been important confounding variables between each of the groups of patients once they were separated into their four respective risk categories. Second, this analysis was based on a subgroup of patients with LBBB configuration, which was not a prespecified variable in the original trial. Third, the highest risk category (score 3‐4) was relatively small and therefore the results for this subgroup should be interpreted with caution. The risk score requires further validation in this high‐risk group. Fourth, our study is limited to the specific population of interest, notably those with NYHA class I to II HF. These findings should be explored in groups with more advanced HF symptoms.

5. CONCLUSIONS

Our results indicate that a simple scoring system comprised of four clinical and echocardiographic variables can be used for mortality risk stratification in patients with mildly symptomatic systolic HF LBBB and CRT‐D therapy. The association for reduced mortality with CRT‐D, compared with ICD therapy, is more pronounced in those who have intermediate mortality risk at baseline, as predicted by a risk score involving four clinical variables. Using the same risk model, CRT‐D was, as compared with ICD, associated with reduced risk with respect to the combined endpoint of HF or death in all patients except those at the highest mortality risk. Patients from the high‐risk group should have a more extensive follow‐up and an early evaluation for more invasive interventions.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

Dr Yitschak Biton is a Mirowski‐Moss Career Development Awardee. Drs Ilan Goldenberg, Valentina Kutyifa, and Scott Solomon are receiving grant support from Boston Scientific. No other potential conflict of interest relevant to this article is reported.

Supporting information

Appendix S1. Supporting information.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We would like to thank Dr. Arthur Moss for his immense support and mentorship. The MADIT‐CRT trial was sponsored by an unrestricted research grant from Boston Scientific Corporation to the University of Rochester, Rochester, NY.

Biton Y, Costa J, Zareba W, et al. Predictors of long‐term mortality with cardiac resynchronization therapy in mild heart failure patients with left bundle branch block. Clin Cardiol. 2018;41:1358–1366. 10.1002/clc.23058

Funding information Unrestricted grant to the University of Rochester; Boston Scientific Corporation

Yitschak Biton and Jason Costa contributed equally to the study.

REFERENCES

- 1. Linde C, Abraham WT, Gold MR, et al. REVERSE (REsynchronization reVErses Remodeling in Systolic left vEntricular dysfunction) Study Group. Randomized trial of cardiac resynchronization in mildly symptomatic heart failure patients and in asymptomatic patients with left ventricular dysfunction and previous heart failure symptoms. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2008;52:1834‐1843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Bristow MR, Saxon LA, Boehmer J, et al. Comparison of Medical Therapy, Pacing, and Defibrillation in Heart Failure (COMPANION) Investigators. Cardiac‐resynchronization therapy with or without an implantable defibrillator in advanced chronic heart failure. N Engl J Med. 2004;350:2140‐2150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Cleland JG, Daubert J‐C, Erdmann E, et al. Cardiac Resynchronization‐Heart Failure (CARE‐HF) Study Investigators. The effect of cardiac resynchronization on morbidity and mortality in heart failure. N Engl J Med. 2005;352:1539‐1549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Goldenberg I, Kutyifa V, Klein HU, et al. Survival with cardiac‐resynchronization therapy in mild heart failure. N Engl J Med. 2014;370:1694‐1701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Moss AJ, Hall WJ, Cannom DS, et al. MADIT‐CRT Trial Investigators. Cardiac‐resynchronization therapy for the prevention of heart‐failure events. N Engl J Med. 2009;361:1329‐1338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Birnie DH, Ha A, Higginson L, et al. Impact of QRS morphology and duration on outcomes after cardiac resynchronization therapy: results from the resynchronization‐defibrillation for ambulatory heart failure trial (RAFT). Circ Heart Fail. 2013;6:1190‐1198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Cleland JG, Abraham WT, Linde C, et al. An individual patient meta‐analysis of five randomized trials assessing the effects of cardiac resynchronization therapy on morbidity and mortality in patients with symptomatic heart failure. Eur Heart J. 2013;34:3547‐3556. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Dupont M, Rickard J, Baranowski B, et al. Differential response to cardiac resynchronization therapy and clinical outcomes according to QRS morphology and QRS duration. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2012;60:592‐598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Zareba W, Klein H, Cygankiewicz I, et al. on behalf of the MADITCRT Investigators. Effectiveness of cardiac resynchronization therapy by QRS morphology in the multicenter automatic defibrillator implantation trial‐cardiac resynchronization therapy (MADIT‐CRT). Circulation. 2011;123:1061‐1072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Zusterzeel R, Curtis JP, Caños DA, et al. Sex‐specific mortality risk by QRS morphology and duration in patients receiving CRT: results from the NCDR. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2014;64:887‐894. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. WRITING COMMITTEE MEMBERS , Yancy CW, Jessup M, Bozkurt B, et al. 2013 ACCF/AHA guideline for the management of heart failure: a report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association task force on practice guidelines. Circulation. 2013;128:e240‐e327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Brignole M, Auricchio A, Baron‐Esquivias G, et al. 2013 ESC guidelines on cardiac pacing and cardiac resynchronization therapy: the task force on cardiac pacing and resynchronization therapy of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC). Developed in collaboration with the European heart rhythm association (EHRA). Eur Heart J. 2013;34:2281‐2329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Moss AJ, Brown MW, Cannom DS, et al. Multicenter automatic defibrillator implantation trial‐cardiac resynchronization therapy (MADIT‐CRT): design and clinical protocol. Ann Noninvasive Electrocardiol. 2005;10:34‐43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Lang R, Bierig M, Devereux R, et al. Chamber Quantification Writing Group; American Society of Echocardiography's Guidelines and Standards Committee; European Association of Echocardiography. Recommendations for chamber quantification: a report from the American Society of Echocardiography's Guidelines and Standards Committee and the Chamber Quantification Writing Group, developed in conjunction with the European Association of Echocardiography, a branch of the European Society of Cardiology. J Am Soc Echocardiogr. 2005;18:1440‐1463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Hinkle LE, Thaler HT. Clinical classification of cardiac deaths. Circulation. 1982;65:457‐464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Beyersmann J. Applied survival analysis (2nd Edn.). D. Hosmer, S. Lemeshow, and S. May (2008). Hoboken: Wiley series in probability and statistics. ISBN: 978‐0‐471‐75499‐2. Biom J. 2009;51:739‐740. [Google Scholar]

- 17. Gasparini M, Klersy C, Leclercq C, et al. Validation of a simple risk stratification tool for patients implanted with cardiac resynchronization therapy: the VALID‐CRT risk score. Eur J Heart Fail. 2015;17:717‐724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Regoli F, Scopigni F, Leyva F, et al. for the collaborative study group Validation of Seattle heart failure model for mortality risk prediction in patients treated with cardiac resynchronization therapy. Eur J Heart Fail. 2013;15:211‐220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Kramer DB, Friedman PA, Kallinen LM, et al. Development and validation of a risk score to predict early mortality in recipients of implantable cardioverter‐defibrillators. Heart Rhythm. 2012;9:42‐46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Bilchick KC, Stukenborg GJ, Kamath S, Cheng A. Prediction of mortality in clinical practice for medicare patients undergoing defibrillator implantation for primary prevention of sudden cardiac death. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2012;60:1647‐1655. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Aaronson KD, Schwartz JS, Chen TM, Wong KL, Goin JE, Mancini DM. Development and prospective validation of a clinical index to predict survival in ambulatory patients referred for cardiac transplant evaluation. Circulation. 1997;95:2660‐2667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Pokushalov E, Romanov A, Prohorova D, et al. Coronary artery bypass grafting with concomitant cardiac resynchronisation therapy in patients with ischaemic heart failure and left ventricular dyssynchrony. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2010;38:773‐780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Penicka M, Bartunek J, Lang O, et al. Severe left ventricular dyssynchrony is associated with poor prognosis in patients with moderate systolic heart failure undergoing coronary artery bypass grafting. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2007;50:1315‐1323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Kancharla K, Weissman G, Elagha AA, et al. Scar quantification by cardiovascular magnetic resonance as an independent predictor of long‐term survival in patients with ischemic heart failure treated by coronary artery bypass graft surgery. J Cardiovasc Magn Reson. 2016;18:45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Romanov A, Goscinska‐Bis K, Bis J, et al. Cardiac resynchronization therapy combined with coronary artery bypass grafting in ischaemic heart failure patients: long‐term results of the RESCUE study. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2016;50:36‐41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Moss AJ, Hall WJ, Cannom DS, et al. Improved survival with an implanted defibrillator in patients with coronary disease at high risk for ventricular arrhythmia. Multicenter automatic defibrillator implantation trial investigators. N Engl J Med. 1996;335:1933‐1940. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Moss AJ, Zareba W, Hall WJ, et al. Multicenter Automatic Defibrillator Implantation. Trial II Investigators Prophylactic implantation of a defibrillator in patients with myocardial infarction and reduced ejection fraction. N Engl J Med. 2002;346:877‐883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Kadish A, Dyer A, Daubert JP, et al. Defibrillators in Non‐Ischemic Cardiomyopathy Treatment Evaluation (DEFINITE) Investigators Prophylactic defibrillator implantation in patients with nonischemic dilated cardiomyopathy. N Engl J Med. 2004;350:2151‐2158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Tang AS, Wells GA, Talajic M, et al. Resynchronizationdefibrillation for ambulatory heart failure trial investigators cardiac‐resynchronization therapy for mild‐to‐moderate heart failure. N Engl J Med. 2010;363:2385‐2395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Betz JK, Katz DF, Peterson PN, et al. Outcomes among older patients receiving implantable Cardioverter‐defibrillators for secondary prevention: from the NCDR ICD registry. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2017;69:265‐274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Appendix S1. Supporting information.