Summary

Recent evidence highlighted a pathogenetic link between redox dysregulation and the early stages of psychosis. Indeed, an increasing number of studies have pointed toward an association between oxidative stress, both at central and peripheral levels, and first psychotic episode. Moreover, basal low antioxidant capacity has been shown to directly correlate with cognitive impairment in the early onset of psychosis. In this context, the possibility to use antioxidant compounds in first psychotic episode, especially as supplementation to antipsychotic therapy, has become the focus of numerous investigations on rodents with the aim to translate data on the possible effects of antioxidant therapies to large populations of patients, with a diagnosis of the first psychotic episode. In this review, we will discuss studies, published from January 1st, 2007 to July 31st, 2017, investigating the effects of antioxidant compounds on neuropathological alterations observed in different rodent models characterized by a cluster of psychotic‐like symptoms reminiscent of what observed in human first psychotic episode. A final focus on the effective possibility to directly translate data obtained on rodents to humans will be also provided.

Keywords: animal model, antioxidant, apocynin, first psychotic episode, N‐acetylcisteine

1. INTRODUCTION

The progression period from a healthy mental status to a psychotic state is characterized by a high vulnerability of the central nervous system (CNS) to several neurodetrimental stimuli, such as redox dysregulation and oxidative stress,1 defined as a disequilibrium between production of reactive oxygen species (ROS) and antioxidant defense.2 The most redox‐sensitive cellular subpopulation in the CNS is represented by the fast‐spiking parvalbumin interneurons, which are known to be highly affected during the complex pathological events leading to first psychotic episode.3 Indeed, for the maintenance of their physiological state, they need large amount of energetic resources, together with well‐functioning ROS‐generating and ROS‐degrading systems.4, 5, 6 Importantly, fast‐spiking parvalbumin interneurons have been described as a highly oxidative stress‐sensitive neuronal subtype, especially during the postnatal period and this also affects all the molecular pathways leading to their maturation.7, 8, 9 Oligodendrocytes are also very vulnerable to redox dysregulation, in particular during the process of myelination which requires the activation of several metabolic pathways,10, 11 resulting in an abundant ROS production accompanied by a decreased basal activity of specific antioxidant systems, such as glutathione.12 An altered redox state has been also described as a major interference for oligodendrocyte maturation and development,7, 13 because of a pathogenetic link existing between glutathione deficits in oligodendrocyte progenitors and a decreased proliferation of these cells.14 Phospholipid and polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFA), which are known to be crucial structural elements of CNS cell membranes, have been also described as particularly vulnerable to the increased production of free radicals as well as to the decrease in antioxidant defense.15 Moreover, a significant association among negative symptoms occurring in first psychotic episode, oxidative stress, decreased PUFA content, and increased levels of lipid peroxidation has been reported.16, 17 In this context, pharmacological compounds specifically targeting an imbalanced redox state may represent promising therapeutic opportunities to prevent oxidative stress‐induced deleterious effects on cortical and hippocampal parvalbumin interneurons and oligodendrocytes. Intuitively, their benefits would be more evident if they could be administered in the very early phases of the disease, as first psychotic episodes could be clinically considered.1 In this review, studies published from January 1st, 2007 to July 31st, 2017, focused on the effects of antioxidant compounds on neuropathological alterations observed in different rodent models presenting psychotic‐like symptoms reminiscent of human first psychotic episode, will be discussed. A final comment on the real possibility to directly translate rodent data to patients will be also provided.

2. LITERATURE SEARCH METHODOLOGY

The literature source of this review consisted in PubMed publications from January 1st 2007 to July 31st 2017, found using the following combinations of keywords: first psychotic episode AND animal models; first psychotic episode AND rodent models; first psychotic episode AND mouse; first psychotic episode AND rat; first psychotic episode AND rodents; first psychotic episode AND pharmacology; first psychotic episode AND preclinical studies; oxidative stress AND first psychotic episode AND animal models; oxidative stress AND first psychotic episode AND rodent models; oxidative stress AND first psychotic episode AND mouse; oxidative stress AND first psychotic episode AND rat; oxidative stress AND first psychotic episode AND rodents; oxidative stress AND first psychotic episode AND pharmacology; oxidative stress AND first psychotic episode AND preclinical studies; antioxidant AND first psychotic episode AND rodent models; antioxidant AND first psychotic episode AND mouse; antioxidant AND first psychotic episode AND rat; antioxidant AND first psychotic episode AND rodents; antioxidant AND first psychotic episode AND pharmacology; antioxidant AND first psychotic episode AND preclinical studies.

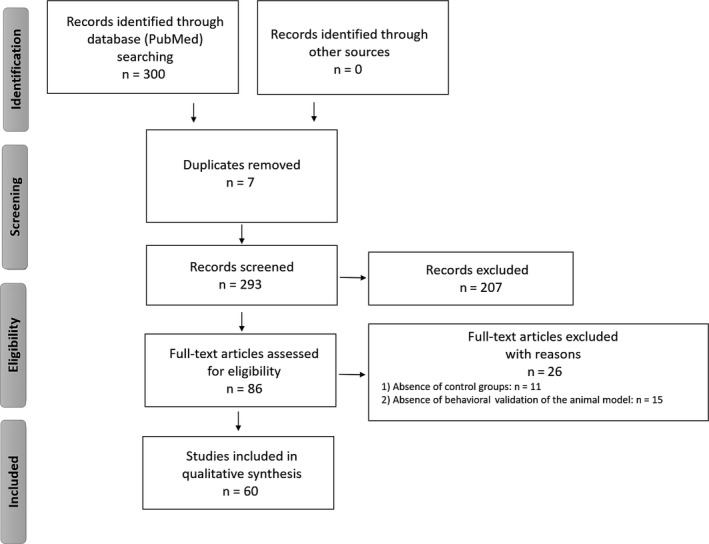

We obtained a total of 300 publications, including 7 duplicative records which were removed from further screening. For the evaluation of the 293 remaining articles, the following inclusion criteria were considered: (i) publication language (only English language publications were included); (ii) type of publication (we only considered original research articles and reviews); (iii) subjects of the study (only studies on rodents were included); (iv) description of the used antioxidant compounds (only studies, in which administration of antioxidants has been clearly described, in terms of type of compounds and dosage, were considered). Using these criteria, we excluded 207 records and assessed for eligibility 86 full‐text articles. We further screened them excluding works (26) which: (i) did not include control groups; (ii) did not clearly report the behavioral validation of the used animal model; resulting, finally, in a total of 60 studies considered for the qualitative synthesis. The PRISMA diagram related to our literature search methodology is reported in Figure 1. The final list of the references for the writing of this review also enclosed publications cited in the Introduction paragraph and in the opening statements of the other sections of this manuscript.

Figure 1.

PRISMA flow diagram

3. ANIMAL MODELS OF FIRST PSYCHOTIC EPISODE: AN EXISTING TOOL?

An “animal model” is labeled as an “approximation of a specific human condition or disease”.18 With respect to psychosis, animal models of this mental disorder have become increasingly important, attempting to develop specific pharmacological options for this psychiatric condition. Although several reliable animal models of psychosis are actually available and largely used in neuropsychiatric research, mainly based on pharmacologic,19, 20, 21, 22, 23, 24 genetic,25, 26, 27, 28 environmental,28, 29, 30, 31, 32 and neurochemical33, 34, 35, 36 manipulations, no rodent models which specifically mimic the peculiarities of first psychotic episode in humans have been developed yet. Indeed, so far, progress in the understanding of the molecular pathways underlying this specific phase of the psychotic disorder has been based on the use of animal models only partially reproducing the neuropathological events occurring during the prenatal, perinatal, and juvenile stages of CNS development.18 In this regard, prenatal exposure to methlazoxymethanol acetate (MAM), a cell division inhibitor, has been shown to determine cortical and hippocampal atrophy, as well as NMDA receptor functioning impairment during the perinatal and juvenile ages, similar to what observed in the early phases of human psychosis.37 Prenatal models, used to induce early psychotic symptoms (such as psychostimulant‐induced increased locomotor activity or reduced prepulse inhibition) in the perinatal or juvenile periods, have been also realized by exposing a pregnant female to different environmental stressors.38 Other developmental animal models have been obtained by executing different kinds of brain lesions during the neonatal period, resulting in many of the behavioral and neuropathological alterations observed at the onset of the psychotic disorder,39 that is the reduction in parvalbumin‐positive GABAergic interneurons and the increased response to glutamatergic agonist and antagonists. A short period of isolation rearing during crucial CNS developmental stages, such as infancy and adolescence, may represent a significant stressor that causes behavioral, neurochemical, and biomolecular alterations reminiscent of what observed in patients who experienced, for the first time, psychotic symptoms, such as hyperactivity in response to novelty, reduced prepulse inhibition, as well as dysfunctions of the dopaminergic, glutamatergic, and serotonergic neurotransmissions.40, 41 These neuropathological alterations have been related to an early impairment of the hypothalamic‐pituitary‐adrenal axis, most likely mediated by an increased expression of the ROS producer enzyme NOX2 in response to social isolation rearing in the juvenile period.42 Furthermore, a short period of social isolation rearing (1 week) during a crucial period of the rat brain development, which may correspond to human infancy, has been shown to induce the loss of blood‐brain barrier integrity and permeability, triggering neuroinflammatory processes as well as alterations of the redox state.29 In rodents, administration of NMDA receptor antagonists in the very early perinatal period is known to be a reliable experimental procedure to induce brain dysfunctions and neuronal injury leading to symptoms partially reminiscent of what encountered by young patients at their first psychotic experience. In this regard, administration of ketamine during the second postnatal week (postnatal days 7, 9 and 11) has been shown to induce specific behavioral dysfunctions such as decreased attentional performance, particularly in terms of loss of the ability to develop a novel strategy, deficit in latent inhibition, reduced capacity to discriminate a novel object with respect to a familiar one, and decreased performance in the social novelty test. Behavioral impairment in this animal model has been associated to specific neuropathological alterations, such as a significant reduction in the number of cortical parvalbumin‐positive GABAergic interneurons.43 Interestingly, perinatal phencyclidine administration in rodents (postnatal days 2, 6, 9, and 12) has been reported to determine an alteration of the redox state in terms of both mitochondrial dysfunctions and decreased antioxidant defense. Indeed, increased functioning of complex I and cytochrome c oxidase, together with structural alterations and enhanced expression of apoptotic markers in specific brain regions, as well as enhanced sensitivity to restraint stress, has been described following phencyclidine treatment during the developmental period.44 Furthermore, decreased SOD1 and SOD2 expression, associated to reduced GSH content and to impaired activities of glutathione reductase and glutathione peroxidase, has been detected in the cortex and hippocampus of rodents receiving phencyclidine at postnatal days 2, 6, 9, and 12.45 A deep biomolecular approach to explain the psychotic effects and the acute neurotoxicity of phencyclidine administration during the perinatal and developmental period has been proposed in an interesting recent article, showing the involvement of a signaling pathway mediated by the expression and activation of the leucine‐rich repeat and immunoglobulin domain‐containing protein (Lingo‐1) in hippocampus.46 Accordingly, neonatal exposure to MK‐801 in rodents has been described to determine, around puberty, neuropathological alterations typical of the early phases of the psychotic disorders in humans, such as reduced cortical mRNA expression of genes encoding for metabotropic glutamatergic receptors, in particular of mGlu3.47 Another common manipulation applied to rodents to mimic symptoms reminiscent of what observed in human first psychotic episode consists in the prenatal exposure to viral or bacterial infections (influenza, toxoplasmosis, citomegalovirus, exposure to the endotoxin LPS) which induces a significant production of specific proinflammatory (ie, IL‐6, IL‐1β, TNF alpha) and anti‐inflammatory (especially IL‐10) citokynes in both the mother and pups.48 Specific nutritional deficits during the prenatal life have been also largely used to induce in animals neuropathological alterations mimicking the symptoms of first psychotic episode. In particular, it has been demonstrated that protein deprivation during pregnancy might determine several dysfunctions of brain development, including dopaminergic, serotonergic, and glutamatergic impairment, prepulse inhibition deficits, and working memory alterations later in life, especially in the postpubertal period.49, 50, 51, 52 Maternal vitamin D deficiency has been also related to an increased risk to develop early psychotic symptoms and, therefore, has been used to model the onset of the first phases of the disease in rodents, with respect to behavioral dysfunctions (regarding especially learning processes and reactions to novelties), altered neurogenesis, decreased levels of neurotrophines, morphological and functional changes in specific brain regions such as prefrontal cortex, hippocampus, and nucleus accumbens and altered expression of specific genes and proteins included in oxidative stress‐related pathways, as well as synaptic plasticity.53, 54

4. EFFECTS OF ANTIOXIDANT TREATMENTS

Emerging lines of evidence have described the effects of different antioxidant treatments in rodent models mimicking first psychotic episode.

4.1. N‐acetylcysteine

A significant number of studies are focused on the possible use of the glutathione precursor N‐acetylcysteine to prevent or reverse neuropathological alterations observed in rodent models of this disorder. In a recent study by Swanepoel and colleagues, a beneficial impact of a treatment with N‐acetylcysteine on behavioral and biomolecular alterations observed in an animal model of psychosis, obtained by rat exposure to maternal immune activation, methamphetamine administration, or a combination of both stimuli during adolescence, has been reported.55 Accordingly, it has been shown that a juvenile and adolescent treatment with this antioxidant compound prevented the loss of cortical inhibitory parvalbumin‐positive interneurons and other electrophysiological and behavioral alterations in a developmental lesional animal model.56 A beneficial impact of N‐acetylcysteine on reduced and oxidized glutathione ratio alterations, decreased expression of cortical inhibitory interneurons and impaired mitochondrial functions, and ROS production in specific brain regions has been also described in another developmental rodent model, obtained by inducing an early NMDA receptor dysfunction in male mice by ketamine administration, therefore, mimicking the first phases of the psychotic disease.57 An antioxidant treatment with this glutathione precursor has showed significant positive effects in preventing or strongly ameliorating neuropathological and behavioral alterations observed in the ketamine perinatal model of psychosis, such as decreased cognitive abilities, reduced social interactions, dysfunctions in the ability to recognize a novel object with respect to a familiar one, and reduced prepulse inhibition.58 In an elegant study of das Nueve Duarte and co‐authors, performed using mice knock‐out for the GSH‐synthesizing enzyme glutamate‐cysteine ligase modulatory subunit (GCLM‐KO), which were characterized by chronic GSH deficit associated to specific cortical neurochemical changes especially at the prepubertal age, N‐acetylcysteine, administered from gestation, has been shown to induce a normalization of all neuropathological alterations observed in GCLM‐KO mice.59 Using the same knock‐out mice, Cabuncgal and co‐authors demonstrated that a treatment with N‐acetylcisteine prevented the detrimental effects of oxidative stress occurring in crucial moments of CNS postnatal development, such as the hampered maturation of parvalbumin‐positive interneurons.13 In the same line, another research group demonstrated, using G72/G30 transgenic mice which exhibit several early psychotic‐like behavioral alterations, that N‐acetylcysteine administration in the perinatal period was able to rescue neuropathological alterations observed in these rodents, such as the decreased activity of the mitochondrial complex I, associated to consequent increase in free radical production, impaired synaptic plasticity, deficits in learning processes, as well as spatial memory acquisition and consolidation.60 In another preclinical study, N‐acetylcysteine, administered to socially isolated rats during perinatal life and from the beginning of the isolation procedure, has been shown to reverse mitochondrial, immunological, neurochemical, and behavioral deficits induced by social isolation and this effect was more significant when N‐acetylcysteine was co‐administered with clozapine.61

4.2. Apocynin

Another ROS scavenger/antioxidant compound, whose effects have been investigated in different animal models reminiscent of first psychotic episode, is apocynin, also known as acetovanillone. This compound has been also demonstrated to have an inhibitory action against NADPH oxidase, significantly preventing superoxide generation in granulocytes and resulting, finally, in beneficial effects against inflammatory processes.62 One of the first evidence on the possible effects of this compound in animal models of psychosis came from the group of Behrens. Indeed, using the ketamine model of this mental disorder, this research group demonstrated that ketamine‐induced neuropathological alterations, in terms of loss of expression of parvalbumin and GAD67 in the subpopulation of the cortical fast‐spiking inhibitory interneurons, were associated to increased superoxide production by the NADPH oxidase NOX2 enzyme and that a treatment with apocynin, decreasing the production of this free radical, prevented ketamine‐induced dysfunctions.63 However, although extremely innovative in the field, this evidence was obtained on adult animals, providing no informations about possible effects of this compound during a developmental stage of an animal model of psychosis, during which first psychotic‐like symptoms may occur. Other lines of evidence highlight the effects of this ROS scavenger in the developmental life period. Indeed, it has been demonstrated that a chronic treatment with apocynin, started at 2 weeks of age, reduced the expression of specific markers of oxidative stress and partially solved behavioral psychotic‐like symptoms in a NMDA‐R hypofunction mouse model, also exposed to social isolation.64 In the same line, we previously demonstrated that the antioxidant/NOX inhibitor apocynin, administered during the early phases of the psychotic state development induced by the procedure of the social isolation rearing, was able to fully reverse the observed behavioral alterations. Interestingly, if applied once the psychotic‐like conditions have become chronic (at the adult age), this same compound could only partially reverse the neuropathological alterations induced by social isolation.65 Furthermore, apocynin treatment in rats isolated during the developmental period and, therefore, presenting first psychotic‐like neuropathological alterations, could also stop the progression of neuroendocrine alterations induced by social isolation.42 Supporting these findings, apocynin treatment from PND 6 to PND 8 in ketamine‐treated rat pups was able to attenuate the ketamine‐induced alterations in memory and learning abilities, the increased expression of markers of oxidative stress, as well as of NOX2 enzyme, and the decreased expression of parvalbumin and GAD67 in cortical inhibitory interneurons.66

4.3. Other antioxidant compounds

Based on our literature search strategy, preclinical studies describing the use and the effects of other antioxidant compounds than N‐acetylcisteine and apocynin in rodent models of psychosis which mimics specifically first psychotic symptoms are quite limited and mainly referred to the following compounds: vitamin C, omega‐3 fatty acids, and ebselen. Evidence about these three compounds is summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Effects of other antioxidant compounds (vitamin C, omega‐3 fatty acid, ebselen) in rodent models of first psychotic‐like symptoms

| Antioxidant compound | Animal models of psychosis/first psychotic‐like symptoms | Period of administration | Effects | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Vitamin C | PCP mouse model | Early adultness (8‐9 wk) | Inhibition of PCP‐induced increased locomotor activity | 72 |

| Ketamine rat model | Early adultness (8 wk) | Prevention of the ketamine‐induced hyperlocomotion and increased AChE activity | 73 | |

| Omega‐3 fatty acids | NMDA receptor hypofunction (NR1KD mice) | Prenatal and perinatal life | Improvement of mice deficits in executive function but not of social interaction and PPI deficits | 74 |

| Amphetamine‐induced rat model of schizophrenia | Adolescence |

|

75 | |

| Ketamine rat model | Youthness/Adolescence |

|

76, 77, 78 | |

| Maternal inflammation mouse model | Early life (postweaning period) |

|

79 | |

| Ebselen | G72/G30 transgenic mice | Juvenile stage and adolescence | Reversal of PPI deficits | 56 |

5. FUTURE DIRECTIONS AND CONCLUSIONS

If it should always be taken into account that each existing animal model for any kind of disease has its own strengths and weaknesses, this concept appears to be even more significant for rodent models of psychosis, in particular for those who have been developed to mimic the neuropathological events and alterations in behavior occurring in human first psychotic episode. However, psychiatric research, performed using these animal models, has largely contributed to the identification of novel pharmacological targets, finally resulting in the development of innovative therapeutic strategies. Molecules with antioxidant properties are increasingly appearing in the pharmacological scenario related to psychiatric disorders, especially to psychosis, most likely as coadiuvants to the classical antipsychotic therapies. For some of these compounds, such as N‐acetylcisteine, results obtained from preclinical studies have encouraged the scientific community to search for a possible clinical application of this molecule (alone or in combination with neuroleptics) for the treatment of subjects suffering from psychosis, with an increasing interest focused on the effects of this glutathione precursor on both the very early stages of the disease and the high‐risk state.67, 68 On the other hand, some antioxidant compounds, such as vitamin E, are commonly used as coadiuvants in the treatment of psychosis and first psychotic episode69, 70, 71 but, virtually, no data on their therapeutic efficacy in this mental disorder have been previously collected using animal models. Thus, future research directions should be addressed to the clarification of the biomolecular aspects characterizing the first psychotic episode, to maximally succeed in reproducing them in rodents and providing a “bridge” for the gap that still exists between preclinical and clinical research.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The writing of this review was supported by Intervento cofinanziato dal Fondo di Sviluppo e Coesione 2007‐2013 – APQ Ricerca Regione Puglia “Programma regionale a sostegno della specializzazione intelligente e della sostenibilità sociale ed ambientale – FutureInResearch,” Italy to SS.

Schiavone S, Trabace L. The use of antioxidant compounds in the treatment of first psychotic episode: Highlights from preclinical studies. CNS Neurosci Ther. 2018;24:465–472. 10.1111/cns.12847

REFERENCES

- 1. Do KQ, Cuenod M, Hensch TK. Targeting oxidative stress and aberrant critical period plasticity in the developmental trajectory to schizophrenia. Schizophr Bull. 2015;41:835‐846. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Schiavone S, Trabace L. Pharmacological targeting of redox regulation systems as new therapeutic approach for psychiatric disorders: a literature overview. Pharmacol Res. 2016;107:195‐204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Barron H, Hafizi S, Andreazza AC, Mizrahi R. Neuroinflammation and oxidative stress in psychosis and psychosis risk. Int J Mol Sci. 2017;18:E651. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Kann O, Huchzermeyer C, Kovacs R, Wirtz S, Schuelke M. Gamma oscillations in the hippocampus require high complex I gene expression and strong functional performance of mitochondria. Brain. 2011;134(Pt 2):345‐358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Harris JJ, Jolivet R, Attwell D. Synaptic energy use and supply. Neuron. 2012;75:762‐777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Kann O, Papageorgiou IE, Draguhn A. Highly energized inhibitory interneurons are a central element for information processing in cortical networks. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2014;34:1270‐1282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Cabungcal JH, Steullet P, Morishita H, et al. Perineuronal nets protect fast‐spiking interneurons against oxidative stress. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2013;110:9130‐9135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Beurdeley M, Spatazza J, Lee HH, et al. Otx2 binding to perineuronal nets persistently regulates plasticity in the mature visual cortex. J Neurosci. 2012;32:9429‐9437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Miyata S, Komatsu Y, Yoshimura Y, Taya C, Kitagawa H. Persistent cortical plasticity by upregulation of chondroitin 6‐sulfation. Nat Neurosci. 2012;15:S411‐S412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Bradl M, Lassmann H. Oligodendrocytes: biology and pathology. Acta Neuropathol. 2010;119:37‐53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Cammer W. Carbonic anhydrase in oligodendrocytes and myelin in the central nervous system. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1984;429:494‐497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Baud O, Greene AE, Li J, Wang H, Volpe JJ, Rosenberg PA. Glutathione peroxidase‐catalase cooperativity is required for resistance to hydrogen peroxide by mature rat oligodendrocytes. J Neurosci. 2004;24:1531‐1540. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Cabungcal JH, Steullet P, Kraftsik R, Cuenod M, Do KQ. Early‐life insults impair parvalbumin interneurons via oxidative stress: reversal by N‐acetylcysteine. Biol Psychiatry. 2013;73:574‐582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Monin A, Baumann PS, Griffa A, et al. Glutathione deficit impairs myelin maturation: relevance for white matter integrity in schizophrenia patients. Mol Psychiatry. 2015;20:827‐838. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Yao JK, Keshavan MS. Antioxidants, redox signaling, and pathophysiology in schizophrenia: an integrative view. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2011;15:2011‐2035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Yao J, Stanley JA, Reddy RD, Keshavan MS, Pettegrew JW. Correlations between peripheral polyunsaturated fatty acid content and in vivo membrane phospholipid metabolites. Biol Psychiatry. 2002;52:823‐830. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Arvindakshan M, Sitasawad S, Debsikdar V, et al. Essential polyunsaturated fatty acid and lipid peroxide levels in never‐medicated and medicated schizophrenia patients. Biol Psychiatry. 2003;53:56‐64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Forrest AD, Coto CA, Siegel SJ. Animal models of psychosis: current state and future directions. Curr Behav Neurosci Rep. 2014;1:100‐116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Bygrave AM, Masiulis S, Nicholson E, et al. Knockout of NMDA‐receptors from parvalbumin interneurons sensitizes to schizophrenia‐related deficits induced by MK‐801. Transl Psychiatry. 2016;6:e778. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Fachim HA, Srisawat U, Dalton CF, et al. Subchronic administration of phencyclidine produces hypermethylation in the parvalbumin gene promoter in rat brain. Epigenomics. 2016;8:1179‐1183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Gogos A, Kusljic S, Thwaites SJ, van den Buuse M. Sex differences in psychotomimetic‐induced behaviours in rats. Behav Brain Res. 2017;322(Pt A):157‐166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Ham S, Kim TK, Chung S, Im HI. Drug abuse and psychosis: new insights into drug‐induced psychosis. Exp Neurobiol. 2017;26:11‐24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Kokkinou M, Ashok AH, Howes OD. The effects of ketamine on dopaminergic function: meta‐analysis and review of the implications for neuropsychiatric disorders. Mol Psychiatry. 2018;23:59‐69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Manning EE, van den Buuse M. Altered social cognition in male BDNF heterozygous mice and following chronic methamphetamine exposure. Behav Brain Res. 2016;305:181‐185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Rasetti R, Weinberger DR. Intermediate phenotypes in psychiatric disorders. Curr Opin Genet Dev. 2011;21:340‐348. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Birnbaum R, Weinberger DR. Functional neuroimaging and schizophrenia: a view towards effective connectivity modeling and polygenic risk. Dialogues Clin Neurosci. 2013;15:279‐289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Sambataro F, Mattay VS, Thurin K, et al. Altered cerebral response during cognitive control: a potential indicator of genetic liability for schizophrenia. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2013;38:846‐853. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Paulus FM, Bedenbender J, Krach S, et al. Association of rs1006737 in CACNA1C with alterations in prefrontal activation and fronto‐hippocampal connectivity. Hum Brain Mapp. 2014;35:1190‐1200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Schiavone S, Mhillaj E, Neri M, et al. Early loss of blood‐brain barrier integrity precedes NOX2 elevation in the prefrontal cortex of an animal model of psychosis. Mol Neurobiol. 2017;54:2031‐2044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Inta D, Renz P, Lima‐Ojeda JM, Dormann C, Gass P. Postweaning social isolation exacerbates neurotoxic effects of the NMDA receptor antagonist MK‐801 in rats. J Neural Transm (Vienna). 2013;120:1605‐1609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Zamberletti E, Vigano D, Guidali C, Rubino T, Parolaro D. Long‐lasting recovery of psychotic‐like symptoms in isolation‐reared rats after chronic but not acute treatment with the cannabinoid antagonist AM251. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol. 2012;15:267‐280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Proitsi P, Lupton MK, Reeves SJ, et al. Association of serotonin and dopamine gene pathways with behavioral subphenotypes in dementia. Neurobiol Aging. 2012;33:791‐803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Dias AM. The integration of the glutamatergic and the white matter hypotheses of schizophrenia's etiology. Curr Neuropharmacol. 2012;10:2‐11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Javitt DC. Glutamatergic theories of schizophrenia. Isr J Psychiatry Relat Sci. 2010;47:4‐16. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Rogoz Z. Effect of co‐treatment with mirtazapine and risperidone in animal models of the positive symptoms of schizophrenia in mice. Pharmacol Rep. 2012;64:1567‐1572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Santini MA, Ratner C, Aznar S, Klein AB, Knudsen GM, Mikkelsen JD. Enhanced prefrontal serotonin 2A receptor signaling in the subchronic phencyclidine mouse model of schizophrenia. J Neurosci Res. 2013;91:634‐641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Gulchina Y, Xu SJ, Snyder MA, Elefant F, Gao WJ. Epigenetic mechanisms underlying NMDA receptor hypofunction in the prefrontal cortex of juvenile animals in the MAM model for schizophrenia. J Neurochem. 2017;143:320‐333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Holloway T, Moreno JL, Umali A, et al. Prenatal stress induces schizophrenia‐like alterations of serotonin 2A and metabotropic glutamate 2 receptors in the adult offspring: role of maternal immune system. J Neurosci. 2013;33:1088‐1098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Negrete‐Diaz JV, Baltazar‐Gaytan E, Bringas ME, et al. Neonatal ventral hippocampus lesion induces increase in nitric oxide [NO] levels which is attenuated by subchronic haloperidol treatment. Synapse. 2010;64:941‐947. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Niwa M, Jaaro‐Peled H, Tankou S, et al. Adolescent stress‐induced epigenetic control of dopaminergic neurons via glucocorticoids. Science. 2013;339:335‐339. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Sestito RS, Trindade LB, de Souza RG, Kerbauy LN, Iyomasa MM, Rosa ML. Effect of isolation rearing on the expression of AMPA glutamate receptors in the hippocampal formation. J Psychopharmacol. 2011;25:1720‐1729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Colaianna M, Schiavone S, Zotti M, et al. Neuroendocrine profile in a rat model of psychosocial stress: relation to oxidative stress. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2013;18:1385‐1399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Jeevakumar V, Driskill C, Paine A, et al. Ketamine administration during the second postnatal week induces enduring schizophrenia‐like behavioral symptoms and reduces parvalbumin expression in the medial prefrontal cortex of adult mice. Behav Brain Res. 2015;282:165‐175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Jevtic G, Nikolic T, Mircic A, et al. Mitochondrial impairment, apoptosis and autophagy in a rat brain as immediate and long‐term effects of perinatal phencyclidine treatment ‐ influence of restraint stress. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2016;66:87‐96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Radonjic NV, Knezevic ID, Vilimanovich U, et al. Decreased glutathione levels and altered antioxidant defense in an animal model of schizophrenia: long‐term effects of perinatal phencyclidine administration. Neuropharmacology. 2010;58:739‐745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Andrews JL, Newell KA, Matosin N, Huang XF, Fernandez‐Enright F. Alterations of p75 neurotrophin receptor and Myelin transcription factor 1 in the hippocampus of perinatal phencyclidine treated rats. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2015;63:91‐97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Uehara T, Sumiyoshi T, Rujescu D, et al. Neonatal exposure to MK‐801 reduces mRNA expression of mGlu3 receptors in the medial prefrontal cortex of adolescent rats. Synapse. 2014;68:202‐208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Powell SB. Models of neurodevelopmental abnormalities in schizophrenia. Curr Top Behav Neurosci. 2010;4:435‐481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Prado EL, Dewey KG. Nutrition and brain development in early life. Nutr Rev. 2014;72:267‐284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Adebayo OL, Adenuga GA, Sandhir R. Postnatal protein malnutrition induces neurochemical alterations leading to behavioral deficits in rats: prevention by selenium or zinc supplementation. Nutr Neurosci. 2014;17:268‐278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Xu J, He G, Zhu J, et al. Prenatal nutritional deficiency reprogrammed postnatal gene expression in mammal brains: implications for schizophrenia. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol. 2014;18:pyu054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Alamy M, Bengelloun WA. Malnutrition and brain development: an analysis of the effects of inadequate diet during different stages of life in rat. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2012;36:1463‐1480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Schoenrock SA, Tarantino LM. Developmental vitamin D deficiency and schizophrenia: the role of animal models. Genes Brain Behav. 2016;15:45‐61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. DeLuca GC, Kimball SM, Kolasinski J, Ramagopalan SV, Ebers GC. Review: the role of vitamin D in nervous system health and disease. Neuropathol Appl Neurobiol. 2013;39:458‐484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Swanepoel T, Moller M, Harvey BH. N‐acetyl cysteine reverses bio‐behavioural changes induced by prenatal inflammation, adolescent methamphetamine exposure and combined challenges. Psychopharmacology. 2018;235:351‐368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Cabungcal JH, Counotte DS, Lewis E, et al. Juvenile antioxidant treatment prevents adult deficits in a developmental model of schizophrenia. Neuron. 2014;83:1073‐1084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Phensy A, Driskill C, Lindquist K, et al. Antioxidant treatment in male mice prevents mitochondrial and synaptic changes in an NMDA receptor dysfunction model of schizophrenia. eNeuro. 2017;4:pii: ENEURO.0081‐17.2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Phensy A, Duzdabanian HE, Brewer S, et al. Antioxidant treatment with N‐acetyl cysteine prevents the development of cognitive and social behavioral deficits that result from perinatal ketamine treatment. Front Behav Neurosci. 2017;11:106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. das Neves Duarte JM, Kulak A, Gholam‐Razaee MM, Cuenod M, Gruetter R, Do KQ. N‐acetylcysteine normalizes neurochemical changes in the glutathione‐deficient schizophrenia mouse model during development. Biol Psychiatry. 2012;71:1006‐1014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Otte DM, Sommersberg B, Kudin A, et al. N‐acetyl cysteine treatment rescues cognitive deficits induced by mitochondrial dysfunction in G72/G30 transgenic mice. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2011;36:2233‐2243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Moller M, Du Preez JL, Viljoen FP, Berk M, Emsley R, Harvey BH. Social isolation rearing induces mitochondrial, immunological, neurochemical and behavioural deficits in rats, and is reversed by clozapine or N‐acetyl cysteine. Brain Behav Immun. 2013;30:156‐167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Rastogi R, Geng X, Li F, Ding Y. NOX activation by subunit interaction and underlying mechanisms in disease. Front Cell Neurosci. 2016;10:301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Behrens MM, Ali SS, Dao DN, et al. Ketamine‐induced loss of phenotype of fast‐spiking interneurons is mediated by NADPH‐oxidase. Science. 2007;318:1645‐1647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Jiang Z, Rompala GR, Zhang S, Cowell RM, Nakazawa K. Social isolation exacerbates schizophrenia‐like phenotypes via oxidative stress in cortical interneurons. Biol Psychiatry. 2013;73:1024‐1034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Schiavone S, Jaquet V, Sorce S, et al. NADPH oxidase elevations in pyramidal neurons drive psychosocial stress‐induced neuropathology. Transl Psychiatry. 2012;2:e111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Zhang H, Sun XR, Wang J, et al. Reactive oxygen species‐mediated loss of phenotype of parvalbumin interneurons contributes to long‐term cognitive impairments after repeated neonatal ketamine exposures. Neurotox Res. 2016;30:593‐605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Asevedo E, Cunha GR, Zugman A, Mansur RB, Brietzke E. N‐acetylcysteine as a potentially useful medication to prevent conversion to schizophrenia in at‐risk individuals. Rev Neurosci. 2012;23:353‐362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Minarini A, Ferrari S, Galletti M, et al. N‐acetylcysteine in the treatment of psychiatric disorders: current status and future prospects. Expert Opin Drug Metab Toxicol. 2017;13:279‐292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Smesny S, Milleit B, Schaefer MR, et al. Effects of omega‐3 PUFA on the vitamin E and glutathione antioxidant defense system in individuals at ultra‐high risk of psychosis. Prostaglandins Leukot Essent Fatty Acids. 2015;101:15‐21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Sarandol A, Sarandol E, Acikgoz HE, Eker SS, Akkaya C, Dirican M. First‐episode psychosis is associated with oxidative stress: effects of short‐term antipsychotic treatment. Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2015;69:699‐707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Bentsen H, Osnes K, Refsum H, Solberg DK, Bohmer T. A randomized placebo‐controlled trial of an omega‐3 fatty acid and vitamins E+C in schizophrenia. Transl Psychiatry. 2013;3:e335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Sershen H, Hashim A, Dunlop DS, Suckow RF, Cooper TB, Javitt DC. Modulating NMDA receptor function with D‐amino acid oxidase inhibitors: understanding functional activity in PCP‐treated mouse model. Neurochem Res. 2016;41:398‐408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Damazio LS, Silveira FR, Canever L, et al. The preventive effects of ascorbic acid supplementation on locomotor and acetylcholinesterase activity in an animal model of schizophrenia induced by ketamine. An Acad Bras Cienc. 2017;89:1133‐1141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Islam R, Trepanier MO, Milenkovic M, et al. Vulnerability to omega‐3 deprivation in a mouse model of NMDA receptor hypofunction. NPJ Schizophr. 2017;3:12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. El‐Sayed El‐Sisi A, Sokkar SS, El‐Sayed El‐Sayad M, Sayed Ramadan E, Osman EY. Celecoxib and omega‐3 fatty acids alone and in combination with risperidone affect the behavior and brain biochemistry in amphetamine‐induced model of schizophrenia. Biomed Pharmacother. 2016;82:425‐431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Zugno AI, Canever L, Mastella G, et al. Effects of omega‐3 supplementation on interleukin and neurotrophin levels in an animal model of schizophrenia. An Acad Bras Cienc. 2015;87(2 Suppl):1475‐1486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. Zugno AI, Chipindo HL, Volpato AM, et al. Omega‐3 prevents behavior response and brain oxidative damage in the ketamine model of schizophrenia. Neuroscience. 2014;259:223‐231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78. Gama CS, Canever L, Panizzutti B, et al. Effects of omega‐3 dietary supplement in prevention of positive, negative and cognitive symptoms: a study in adolescent rats with ketamine‐induced model of schizophrenia. Schizophr Res. 2012;141:162‐167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79. Li Q, Leung YO, Zhou I, et al. Dietary supplementation with n‐3 fatty acids from weaning limits brain biochemistry and behavioural changes elicited by prenatal exposure to maternal inflammation in the mouse model. Transl Psychiatry. 2015;5:e641. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]